- Department of Political Science, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

This study examines how members of Israel’s 24th Knesset perceive and define democracy, and how their political-ideological identities influence these understandings. Using qualitative analysis of public statements and social media posts from 72 Knesset members, the research reveals a strong correlation between MKs’ ideological-political identities and their framing of democracy. Liberals tended to emphasize substantive democratic values like pluralism and individual rights, while conservatives prioritized a populist notion of majority rule. Religious MKs often viewed democracy through a sectarian lens, subjugating it to Jewish religious principles. Non-Jewish MKs vacillated between liberal and populist stances. The study raises concerns about the depth of commitment to democratic principles among many elected officials and the potential implications for Israeli democracy. It highlights the tension between Israel’s Jewish and democratic identities and suggests that the political landscape is increasingly challenging the vision of Israel’s founders for a democratic state.

Introduction

In recent decades, the global decline of democratic institutions has prompted scholars to examine how political leaders understand and implement democratic principles. This phenomenon has become particularly salient in established democracies, where erosion often occurs through legal channels rather than overt regime change. Our research investigates this phenomenon within Israel by analyzing the democratic perspectives of representatives serving in the 24th Knesset (2021–2022), offering unique insights into how elected officials’ understanding of democracy shapes institutional stability. Specifically, we examine the following research question: How do members of Israel’s 24th Knesset perceive and define democracy, and how do their political-ideological identities influence these understandings?

The Israeli political landscape provides an exceptionally valuable context for such analysis for several reasons. As a nation defining itself through dual identities - both Jewish and democratic - Israel continually navigates complex tensions between religious heritage, national character, and democratic governance. Israel’s unique institutional framework, lacking a formal constitution while relying on Basic Laws as constitutional substitutes, creates distinctive challenges for democratic stability. The period of the 24th Knesset was particularly noteworthy, characterized by unprecedented political developments including the formation of Israel’s most diverse governing coalition and intensifying debates over democratic institutions.

This research makes several innovative contributions to the literature on democratic backsliding and political representation. It develops a novel framework for analyzing how legislators’ ideological backgrounds influence their interpretation of democratic principles, moving beyond traditional left–right distinctions to examine how religious, ethnic, and nationalist identities shape democratic understanding. It provides the first comprehensive analysis of how members of Israel’s parliament conceptualize democracy during a period of significant institutional stress, offering insights into the relationship between political ideology and democratic interpretation. The study contributes to theoretical understanding of democratic erosion by examining how elected officials’ varying interpretations of democracy can either reinforce or undermine democratic institutions.

The research aims to examine how members of Israel’s 24th Knesset perceive and define democracy, and how their political-ideological identities influence these understandings. It analyzes the relationship between MKs’ conceptual frameworks of democracy and their approach to specific democratic institutions and processes, while investigating how different interpretations of democracy affect legislative behavior and institutional stability. Furthermore, it explores the implications of varying democratic interpretations for Israel’s future as both a Jewish and democratic state.

Through extensive analysis of statements and social media content from 72 Knesset members, our research revealed that legislators’ ideological backgrounds significantly shaped their interpretations of democracy. While left-leaning members emphasized democratic institutions and individual rights, right-wing representatives prioritized majority governance. Religious parliamentarians often viewed democratic principles through a religious lens, while Arab members alternated between various democratic interpretations based on specific issues.

These findings highlight growing concerns about democratic stability in Israel and suggest that many elected officials may prioritize other values over democratic principles. The research carries significant implications for understanding democratic backsliding in contexts where religious, ethnic, or nationalist identities compete with democratic principles. As democratic institutions face mounting challenges worldwide, understanding how legislators conceptualize democracy becomes crucial for identifying and addressing threats to democratic governance.

The paper proceeds by first providing theoretical background on democratic backsliding and reviewing relevant literature. It then presents the Israeli case study in detail, followed by our research design and methodology. The findings are organized around key themes in democratic interpretation, and the paper concludes with a discussion of implications and recommendations for strengthening democratic resilience.

Theoretical background

Recent scholarship has identified a troubling global pattern in how democracies deteriorate. Rather than experiencing sudden regime changes, democratic institutions often erode gradually through actions taken by democratically elected officials themselves. Daly (2019) has conceptualized this as ‘democratic decay, ‘emphasizing how institutional erosion often occurs through legal and political processes that maintain a democratic facade. This process of democratic backsliding differs from historical patterns of democratic collapse in that it typically unfolds through legal channels, with elected leaders systematically dismantling democratic checks and balances while maintaining a facade of democratic legitimacy (Haggard and Kaufman, 2021; Scheppele, 2018).

This process often involves what Israel’s Attorney General Baharav-Miara described as a “quiet reform” - the neutralization of governmental checks through administrative rather than legislative means.1 Rather than outright abolition of democratic institutions, this involves the gradual dismantling of established norms and the politicization of previously independent professional systems. The effect is to hollow out democratic institutions while formally preserving them.

Modern democratic backsliding primarily affects the liberal aspects of democracy - civil rights, rule of law, and checks and balances - while maintaining the outer shell of democratic institutions. As documented by several scholars (Bermeo, 2016; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2019; Haggard and Kaufman, 2021; Oren, 2023), this erosion typically follows six main patterns: undermining judicial and regulatory independence, challenging minority rights, harassing civil society organizations, restricting academic and artistic freedom, compromising media independence, and manipulating electoral advantages. Each of these patterns represents a distinct threat to democratic governance while potentially maintaining democratic appearances.

The undermining of judicial independence often begins subtly, through changes in appointment procedures or jurisdictional limitations. Challenges to minority rights frequently occur through seemingly neutral legislative measures that disproportionately affect certain groups. The harassment of civil society organizations might take the form of increased regulatory burdens or funding restrictions. Academic and artistic freedom face pressure through budget cuts or administrative oversight. Media independence can be compromised through ownership changes or regulatory pressure. Electoral advantages are often secured through technical changes to voting procedures or district boundaries.

The Israeli context presents particular vulnerabilities to democratic backsliding due to its limited institutional safeguards. As Oren (2023) emphasizes, Israel lacks several traditional checks and balances: it has no written constitution, no second legislative chamber, and no federal system. Moreover, within Israel’s parliamentary system, the government wields significant control over the Knesset through its coalition management. This leaves the Supreme Court as the primary institutional check against constitutional rights violations by the Knesset and government. This institutional framework makes Israel especially susceptible to democratic erosion through legal and administrative means.

The process of democratic erosion often follows what Ágh (2016) terms “The Hungarian Disease” - a pattern where democratically elected leaders transform democratic systems into authoritarian regimes through subtle means. This transformation operates by weakening formal governmental institutions while strengthening informal power networks, effectively hollowing out democratic structures from within. The process typically unfolds through legal-political and socio-economic restructuring that maintains democratic appearances while systematically undermining democratic substance. The Hungarian example provides particularly relevant insights for understanding similar processes in other democracies facing institutional challenges.

Waldner and Lust (2018) provide a comprehensive framework for understanding democratic backsliding, identifying key institutional changes that often precede democratic decline. This analysis is particularly relevant to the Israeli context, where, as Oren (2023) demonstrates, institutional erosion has occurred through both formal and informal channels.

While Bermeo (2016) initially offered optimistic conclusions about democracy’s long-term resilience against authoritarian tendencies, recent global developments have challenged this view. Her research, conducted nearly a decade ago, suggested that autocracies would ultimately fail while democracies would strengthen. However, contemporary global trends indicate otherwise. Contemporary forms of democratic backsliding prove particularly challenging to resist because they often enjoy broad popular support and operate through incremental changes. These might include alterations to electoral laws, district boundaries, electoral commissions, and voter-registration procedures - technical changes that rarely inspire mass mobilization despite their significant impact on democratic functioning.

Capoccia’s (2005) comparative analysis of interwar European democracies provides crucial insights into democratic resistance against authoritarian challenges. His work emphasizes that democratic collapse often stems from leadership failures rather than inevitable structural factors. As Linz and stepan (1996) note, “critical figures behaved like actors in a Greek tragedy, knowing and expecting their fate but fulfilling their role to the bitter end.” This observation particularly resonates with our study, as it highlights how parliamentary members’ internalization of democratic principles can either strengthen or undermine democratic institutions. The interwar period provides valuable lessons about the importance of leadership decisions in moments of democratic crisis.

Modern democratic backsliding primarily affects the liberal aspects of democracy - civil rights, rule of law, and checks and balances - while maintaining the outer shell of democratic institutions. As documented by several scholars (Bermeo, 2016; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2019; Haggard and Kaufman, 2021; Daly, 2019), this erosion typically follows specific patterns that include undermining judicial independence, challenging minority rights, and weakening democratic institutions while maintaining democratic appearances.

The concept of defensive democracy becomes especially relevant in this context. This framework acknowledges that preserving democratic systems may sometimes require restricting certain democratic freedoms, particularly when facing internal threats from actors who use democratic means to undermine democracy itself. This paradox emerged starkly in the aftermath of situations where non-democratic elements successfully exploited democratic principles to subvert democracy, with the Nazi Party’s democratic rise to power in 1933 serving as the most dramatic historical example. As expressed in one of Joseph Goebbels’ famous speeches: “If democracy behaved toward us, when we were in opposition, according to democratic principles, then democracy would have to do so. But we have never said that we represent the democratic idea, but we have openly said that we use democratic means to come to power, but when we come to power, we will refuse to give our opponents, and without mercy, all the same rights and means that were given to us when we were in the opposition” (Ziv, 1987).

Recent research emphasizes the crucial role of political elites in either safeguarding or undermining democratic institutions. As Gidron et al. (2023) demonstrate, successful democratic backsliding typically requires elected leaders to construct diverse coalitions supporting anti-democratic measures. These coalitions often comprise multiple groups with varying motivations for undermining democratic checks and balances. The ability of political leaders to build such coalitions while maintaining democratic legitimacy represents a key challenge for democratic preservation.

The relationship between populism and political liberalism adds another layer of complexity to this analysis. Canihac (2022) explores this dynamic by examining the distinctions between anti-liberalism and post-liberalism, identifying fundamental tensions between populist movements and liberal democratic principles. His research combines these concepts to enable comprehensive empirical and comparative study of populism as a discursive, ideological, and practical phenomenon. This theoretical understanding helps explain how populist rhetoric can serve as a vehicle for democratic erosion while maintaining democratic appearances.

Understanding these theoretical frameworks becomes crucial for analyzing how elected officials conceptualize and implement democratic principles, particularly in contexts like Israel where religious, ethnic, and nationalist identities create additional complexities in democratic governance. The interaction between these various theoretical elements helps explain why studying parliamentarians’ understanding of democracy provides crucial insights into processes of democratic erosion and resilience. The theoretical framework established here provides the foundation for examining how members of Israel’s 24th Knesset understand and interpret democratic principles, and how these interpretations influence their approach to democratic governance.

The case study

Israel operates as a Parliamentary Democracy with three distinct branches of government, but with several unique characteristics that significantly affect its democratic functioning. The Executive Power, residing in the government-cabinet headed by the prime minister, wields extraordinary influence over the legislative process through its coalition management powers. This dominance is further enhanced by Israel’s electoral system, which uses pure proportional representation without geographical constituencies. The absence of direct constituent accountability means Members of Knesset (MKs) are primarily beholden to party leadership rather than specific voter communities, potentially weakening democratic representation.

The Legislative Power is vested in the Knesset (parliament), consisting of 120 members elected through nationwide party lists. This system, while ensuring broad representation of different political movements, can lead to fragmentation and instability. The Judicial Power, led by the Supreme Court, serves as both the High Court of Justice and the highest appellate court. However, its authority to check executive and legislative power remains a subject of ongoing political contestation.

Israel’s deeply multicultural nature fundamentally shapes its political discourse and democratic challenges. The society comprises several major groups - secular Jews, religious Jews (both Modern Orthodox and Ultra-Orthodox), Arab citizens (approximately 20% of the population), and various immigrant communities - each with distinct political interests and democratic conceptions. This diversity creates complex dynamics in parliamentary politics, where different groups’ understanding of democracy often reflects their particular cultural and ideological perspectives.

The context of the 24th Knesset (2021–2022) can only be understood through the unprecedented political crisis that preceded it. Beginning in April 2019, Israel entered a period of extraordinary political instability, holding four elections in less than 2 years. The April 2019 election resulted in a deadlock when Benjamin Netanyahu failed to form a coalition. A second election in September 2019 produced similar results. The third election in March 2020 led to an emergency unity government between Netanyahu and Benny Gantz, which collapsed after 7 months. This series of failed governments reflected deep ideological divisions and personal rivalries that would significantly impact the 24th Knesset’s functioning.

The analysis of MKs’ political-ideological identities builds upon established theoretical frameworks in political sociology and Israeli political studies. Previous research by Cohen-Zada et al. (2016) demonstrates how religious beliefs influence political compromise in Israeli politics. Freedman’s (2020) work on religious voting patterns and Filc’s (2020) analysis of populist politics in Israel provide crucial theoretical foundations for understanding how different ideological groups approach democratic governance.

Our framework for analyzing MKs’ political-ideological identities extends these theoretical approaches by examining four primary reference groups: liberals (typically center-left), conservatives (typically right-wing), religious Jews (varying political alignments), and non-Jewish representatives (predominantly Arab parties). This categorization builds upon but goes beyond traditional left–right distinctions, incorporating insights from Samoha’s (2000) work on ethnic democracy and Ravitsky’s (1993) analysis of religious political thought in Israel.

This analytical framework innovates in several ways. First, it integrates religious and ethnic identities as primary rather than secondary factors in democratic interpretation, moving beyond conventional ideological spectrum analysis. Second, it examines how these different identity groups understand and operationalize democratic principles during periods of institutional stress, contributing to literature on democratic resilience. Third, it provides a systematic analysis of how parliamentary representatives’ ideological backgrounds influence their approach to specific democratic institutions and processes.

These ideological divisions and their impact on democratic interpretation became particularly salient during the 24th Knesset, as the coalition attempted to navigate competing visions of democratic governance while maintaining political stability. The period serves as a crucial case study for understanding how different political actors conceptualize and operationalize democratic principles within the unique context of Israel’s political system.

The subsequent transition to the 25th Knesset, with its proposed judicial reforms, further highlighted the significance of the period under study. This transition demonstrated how different interpretations of democracy among political leaders can lead to fundamental challenges to democratic institutions, particularly in contexts where multiple cultural and ideological groups compete for influence over the nature of the democratic system itself.

Israeli political context and major parties (2019–2021)

The Israeli political landscape provides an exceptionally valuable context for such analysis. Chazan (2020) argues that Israel’s democracy has reached a critical turning point, with traditional democratic norms and institutions facing unprecedented challenges. As Kremnitzer and Shany (2020) demonstrate through their comparative analysis of Israel, Hungary, and Poland, the patterns of democratic backsliding in Israel share important similarities with other declining democracies while maintaining distinct characteristics rooted in Israel’s unique political culture.

To understand the political dynamics of the 24th Knesset, it’s crucial to examine the main political parties and their developments in the years immediately preceding the March 2021 elections.

Likud, led by Benjamin Netanyahu, has traditionally been Israel’s dominant right-wing party, promoting free-market economics and hawkish security policies. During 2019–2021, the party maintained its position as the largest parliamentary faction but faced increasing challenges due to Netanyahu’s ongoing corruption trial and internal party tensions. Several prominent Likud members, including Gideon Sa’ar, left to form new parties in protest of Netanyahu’s leadership.

Yesh Atid (There is a Future), led by Yair Lapid, positioned itself as a centrist secular party focusing on middle-class economic issues and advocating for separation of religion and state. The party gained prominence as a leading opposition force, particularly after the collapse of the Blue and White alliance.

The Blue and White alliance, originally formed to challenge Netanyahu’s leadership, underwent significant transformation during this period. Led by Benny Gantz, it initially included Yesh Atid but split in 2020 when Gantz decided to form an emergency government with Netanyahu, a move that shattered the alliance and led to Lapid’s departure.

Yamina (Rightward), led by Naftali Bennett, represented the religious-Zionist and modern Orthodox constituencies, advocating for settlement expansion and religious influence in state affairs. The party’s position shifted significantly during this period, eventually playing a pivotal role in forming the “government of change.”

Religious parties maintained their traditional roles: Shas representing Sephardic ultra-Orthodox Jews and United Torah Judaism representing Ashkenazi ultra-Orthodox communities. Both parties historically aligned with Netanyahu’s coalitions while prioritizing religious interests and welfare policies for their constituencies.

The Joint List, an alliance of predominantly Arab parties, achieved historic success in earlier elections but faced internal divisions over cooperation with Zionist parties. These tensions led to Ra′am (United Arab List) breaking away to pursue a more pragmatic approach to political participation, ultimately joining the Bennett-Lapid coalition.

New Hope, formed by former Likud member Gideon Sa’ar in late 2020, represented right-wing voters opposed to Netanyahu’s leadership. The party attracted several prominent Likud defectors and positioned itself as a right-wing alternative to Netanyahu’s leadership style.

Israel Beiteinu, led by Avigdor Lieberman, traditionally represented Russian-speaking immigrants but evolved to champion secular right-wing policies. The party became increasingly critical of ultra-Orthodox influence in government, making it a key player in coalition negotiations.

Labor and Meretz, the traditional left-wing Zionist parties, struggled with declining electoral support but maintained their focus on peace initiatives, social democratic policies, and environmental issues. Both parties underwent leadership changes and internal reforms during this period.

This complex political landscape reflected deeper societal divisions over religion, state, security, and democracy. The period saw the emergence of new political alignments that transcended traditional left–right divisions, particularly regarding Netanyahu’s leadership and the role of Arab parties in government. These developments set the stage for the unprecedented coalition formations and political dynamics that would characterize the 24th Knesset.

Research design

This study employs a qualitative, inductive approach using critical discourse analysis to examine how Knesset members conceptualize and articulate democratic principles. The research design integrates multiple data sources to ensure comprehensive coverage and triangulation of findings. Our primary research question explores how Knesset members’ political-ideological identities influence their understanding and interpretation of democracy. Additionally, we investigate how different ideological groups frame key democratic concepts, what patterns emerge in how MKs discuss democratic institutions, and how they reconcile tensions between democratic and other values.

Research hypotheses

1. Political and ideological identity fundamentally shapes how Knesset members understand and interpret democracy, with right-wing members typically reducing it to majority rule alone.

2. For many Knesset members, democracy is subordinate to other values - whether religious beliefs, personal loyalty to leaders, or sectoral interests. These members prioritize their specific community’s needs over the broader national interest.

3. The dual definition of Israel as both Jewish and democratic creates inherent tensions that challenge the state’s democratic foundations and sovereignty.

Methodology

This study employed an interpretive approach to examine how Knesset members conceptualize and define democracy, with particular focus on how their ideological and political identities influence these perceptions. The research methodology combined both inductive and deductive elements, utilizing descriptive and explanatory inference principles as outlined by King et al. (1999).

The analysis framework was guided by Fairclough’s (1992) four-stage model of critical discourse analysis. One, a focus on specific manifestations or instances of democratic discourse; Two, identify discourse factors that reveal power dynamics, particularly examining how language use reflects and shapes political reality; Three, analyze whether observed democratic deficits are inherent to the social order and how discourse patterns reinforce these issues; four, consider potential remedies and corrections for identified democratic shortcomings.

To systematically analyze elected officials’ attitudes toward democracy, we employed the consensus method, which involves comparing similarities and differences in public statements. This approach allowed us to examine how language use reflects political actors’ perceived realities. In relevant cases, we supplemented this with Foucault’s (1970) approach to power relation analysis, which examines how conventions, values, and rules shape political discourse. This combined methodology enabled us to map the positions and relationships of political actors by analyzing their use of language within the political context.

The research design deliberately integrated multiple analytical approaches to capture both explicit statements about democracy and the implicit frameworks that shape how different political actors’ approach democratic governance. This methodological framework proved particularly valuable for understanding the complex interplay between political ideology and democratic interpretation within Israel’s unique political landscape.

Sources

The data collection process was drawn from three primary sources. First, we conducted systematic media content analysis through daily monitoring of “Yifat Media Information” from November 2021 to May 2022, analyzing over 5,000 articles and news items using keyword-based collection methods. Second, we examined social media discourse, analyzing more than 500 posts, primarily from Facebook, focusing on both direct statements by MKs and public responses to their positions. This social media analysis provided valuable insight into informal political discourse and public engagement with democratic concepts. Third, we conducted supplementary independent press monitoring to capture additional relevant content, expert commentary, and legal and academic perspectives.

Sample

Our sampling strategy focused on 72 Knesset members, representing 60% of the total Knesset membership. This sample was strategically stratified by ideological grouping to ensure representative coverage across the political spectrum: 25 liberals (35%), 28 conservatives (39%), 11 religious Jews (15%), and 8 non-Jews (11%). This distribution closely mirrors the overall ideological composition of the 24th Knesset while providing sufficient representation from each group for meaningful analysis. The conclusions are based on sampling public statements of and about the subjects.

Analysis

The analytical framework employed a three-stage coding process. We began with initial open coding to identify key themes and concepts, followed by axial coding to organize these codes into thematic clusters and develop analytical categories. Finally, selective coding integrated these categories into a coherent theoretical framework. Our analysis examined seven key dimensions of democratic understanding: constitutional framework, Jewish-Democratic identity, separation of powers, majority rule concepts, religious-state relations, human rights understanding, and views on democratic institutions. To ensure research quality and reliability, we systematically triangulated data sources to strengthen the validity of our findings. For each of the topics discussed in the study, dozens of posts were examined, the criteria for selection were: relevance to the topic, wording in more or less standard language, without spelling errors. Avoiding repetitively, representation of topics under discussion to present different political parties’ positions.

Limitations

Several important limitations should be noted. Methodologically, our focus on public statements may not fully capture private beliefs or motivations, and the analysis is subject to potential social desirability bias. Additionally, the study’s time frame provides a snapshot of a specific period in Israeli political history. Sampling limitations include the inability to include all MKs and variation in public visibility among different members. Finally, the interpretive nature of discourse analysis presents inherent challenges, particularly in navigating cultural and linguistic contexts and the complexity of political positioning.

These limitations notwithstanding, the research design provides a robust framework for examining how Israeli legislators understand and articulate democratic principles. By combining multiple data sources and employing systematic analysis methods, we develop a comprehensive picture of how different ideological groups conceptualize democracy and its relationship to other key values in the Israeli political system.

The research methodology allows us to examine not only explicit statements about democracy but also implicit assumptions and frameworks that shape how different political actors approach democratic governance. This approach is particularly valuable in understanding the complex interplay between political ideology and democratic interpretation in the context of Israel’s unique political landscape.

Findings

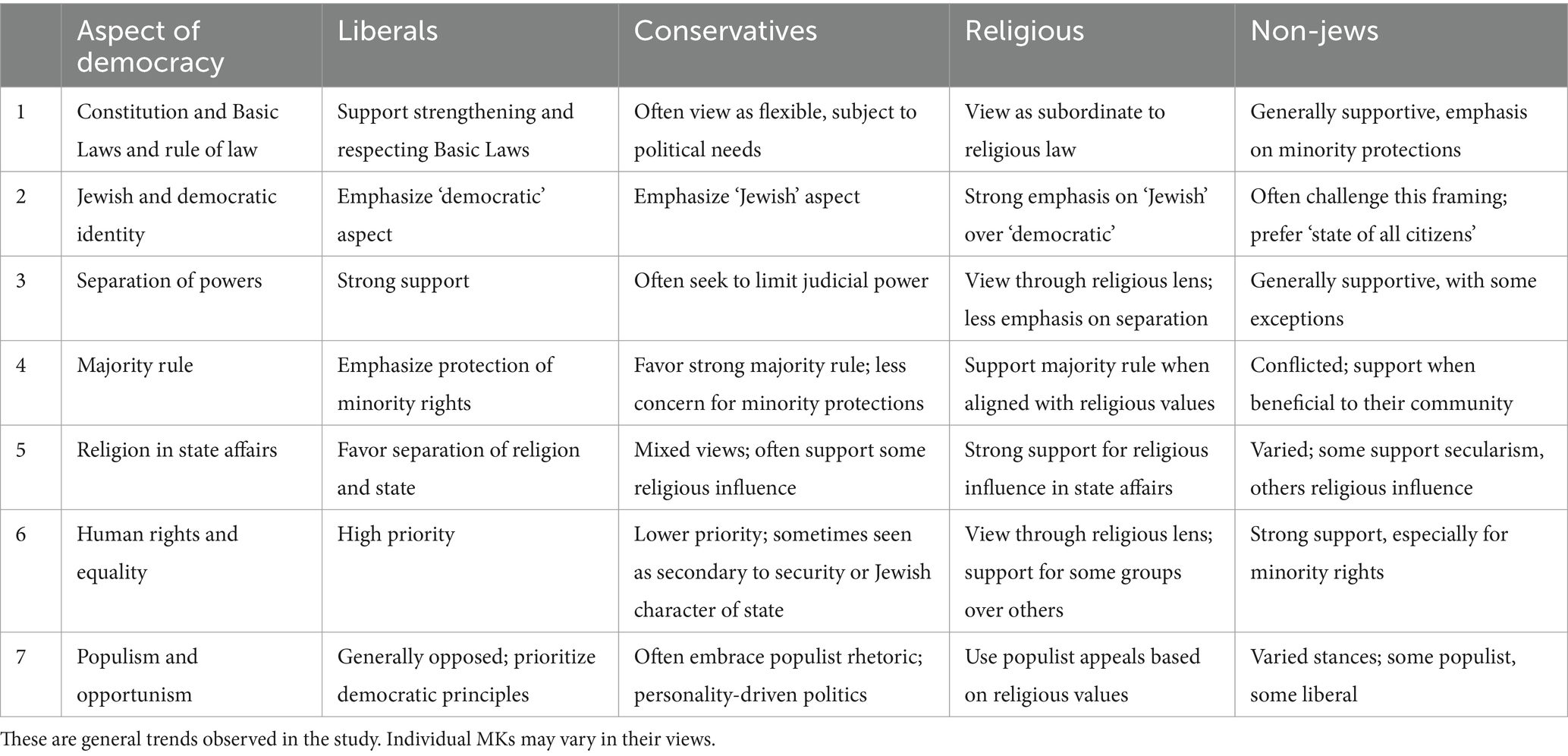

Our analysis reveals clear patterns in how members of the 24th Knesset understand and interpret democracy, with distinct variations across ideological groups. Through systematic analysis of public statements, media appearances, and social media posts, we identified significant correlations between MKs’ political-ideological identities and their democratic conceptualizations. The findings are organized around seven primary dimensions: constitutional framework, Jewish-democratic identity, separation of powers, majority rule, religion’s role, human rights and equality, and populist tendencies (see Table 1).

Constitutional framework and Basic Laws

The analysis reveals a fundamental divide in how different ideological groups approach Israel’s constitutional structure. Liberal MKs consistently emphasized the importance of Basic Laws as constitutional safeguards, viewing them as essential protections for democratic institutions and individual rights. For instance, several liberal MKs explicitly opposed attempts to modify Basic Laws for political expedience, arguing that such changes undermined democratic stability.

This perspective is well illustrated by Uriel Lin, Chairman of the Committee of “Constitution, Law and Justice” during the twelfth Knesset, who stated: “There are isolated issues, not central ones, that require more legislative work, and there is another question of ensuring the special status of a number of Basic Laws. However, both in content and concept, the necessary infrastructure for the creation of a written constitution in Israel has been completed.”2

In contrast, conservative MKs typically viewed Basic Laws more instrumentally, often supporting modifications to achieve political objectives. This was particularly evident during debates over government formation, where conservative MKs advocated for constitutional changes to accommodate political necessities. The case of Netanyahu’s eligibility to serve as prime minister while under indictment illustrated this dynamic, with conservative MKs supporting modifications to Basic Laws to ensure his continued leadership.

This tension was powerfully captured by former Knesset legal advisor Nurit Elstein, who wrote: “Benjamin Netanyahu, there is a real basis for your fear. The court can decide that you lack the normative capacity to be prime minister under indictment for serious offenses of integrity that are disgraceful in nature… No legal model has been born that will absolutely guarantee that a fundamentally crooked issue will gain legitimacy as long as Israel is a democracy” (Elstein, 2020)3.

Religious MKs demonstrated a distinct approach, generally viewing Basic Laws as subordinate to religious law. Several religious MKs explicitly stated that democratic constitutional arrangements should yield to religious principles when conflicts arise. This perspective was particularly evident in debates over religious freedom and state institutions.

Jewish-democratic identity

The tension between Israel’s Jewish and democratic characters emerged as a central theme in our analysis. This conflict manifests at two levels: within Jewish political discourse and between Jewish and non-Jewish perspectives on state identity. Liberal MKs typically emphasized the democratic component, arguing for equal citizenship and secular governance. Conservative MKs, particularly those aligned with religious parties, prioritized Jewish character over democratic principles, often citing historical and religious justifications.

MK Bezalel Smotrich articulated the nationalist perspective clearly: “The Jewish and Zionist values on which the State of Israel is based, on which the settlement is based, and which give it its right to exist -- are the values of the national camp of which we are a part. We cannot support a government that harms Zionism and Judaism so badly.” (Smotriz)4.

The participation of an Arab party (Ra′am) in the governing coalition for the first time in Israeli history brought these tensions into sharp relief. Our analysis of MK statements during this period revealed diverse reactions that closely aligned with ideological positions. Liberal MKs generally welcomed this development as strengthening Israeli democracy, while conservative MKs often framed it as threatening the state’s Jewish character.

The debate over the Nation-State Law further highlighted these divisions. Conservative and religious MKs strongly supported the law’s emphasis on Jewish national character, while liberal and non-Jewish MKs criticized its implications for democratic equality. This divide reflected deeper disagreements about the fundamental nature of Israeli democracy and citizenship.

Separation of powers and governance

Analysis of MK statements regarding institutional authority and governance revealed sharply divergent views of democratic structures. Liberal MKs consistently supported robust separation of powers and judicial independence, viewing these as essential democratic safeguards. They frequently opposed attempts to limit judicial review and emphasized the importance of institutional checks and balances.

Conservative MKs often expressed skepticism toward judicial authority, particularly regarding the Supreme Court’s power of review. Several prominent conservative MKs explicitly called for limiting judicial oversight, framing it as an undemocratic constraint on majority rule. This tension is clearly illustrated in MK Simcha Rothman’s response to controversy over judicial authority: “My dream is to turn the Supreme Court into a court that no one wants to blow up, because it will not engage in politics and will not try to impose the values and perceptions of the justices on the public. An override clause and a change in the method of appointing judges, together with judicial conservatism and judicial modesty, is the way to ease tensions in the struggle between the authorities in Israel.” (Rotman)5 MK David Amsalem starkly articulated a more extreme position on institutional authority: “When we return to power, we will run over the left to the end. We’ll trample on them. Let us start with the Supreme One, we’ll put it in order. Then we will kick them out of the plenum and the committees… We will cancel the laws they passed” (Shumplebi)6.

The research also uncovered significant differences in how MKs approached parliamentary procedure and opposition rights. During the 24th Knesset, opposition tactics often challenged traditional democratic norms, including boycotts of parliamentary committees and attempts to delegitimize the governing coalition. These actions revealed a conception of democracy that prioritized political power over institutional stability.

Majority rule and protection of minorities

A fundamental tension emerged in how different ideological groups approach the balance between majority rule and minority protection. Conservative MKs frequently advocated for an expansive interpretation of majority powers, often supporting measures that would strengthen executive and legislative authority at the expense of institutional checks. This was particularly evident in debates over the “French Law” and override clause proposals, which would have significantly altered the balance of power between branches of government.

Liberal MKs, in contrast, consistently emphasized the importance of protecting minority rights and maintaining institutional safeguards against majority overreach. The research revealed a striking pattern where MKs’ position on majority rights often shifted based on their coalition status, suggesting an instrumental rather than principled approach to democratic norms.

This dynamic was particularly visible in the controversy surrounding the formation of the “government of change.” Opposition members, primarily from Likud, challenged the legitimacy of the narrow majority government, despite having previously defended similar arrangements when they were in power. The rhetoric sometimes escalated to concerning levels, as evidenced by then-Foreign Minister Yair Lapid’s comparison of opposition tactics to those that preceded Rabin’s assassination.

Religion and state

The research revealed deep divisions in how different groups conceptualize the relationship between religion and democracy. The 2018 Democracy Index highlighted a concerning trend among religious and ultra-Orthodox groups to view democracy as potentially antagonistic to Jewish values. Religious MKs often prioritized religious considerations over democratic principles, while liberal MKs advocated for clearer separation between religion and state.

This tension manifests in practical governance issues, as religion plays a central role in Israeli civil life, affecting marriage, divorce, residency rights, and the calendar. The research showed that religious MKs consistently framed democratic principles through a religious lens, while liberal MKs emphasized secular democratic values.

Human rights and equality

Analysis of debates over equality legislation revealed significant ideological divides in approaches to human rights. Liberal MKs consistently supported strengthening legal protections for equality, as evidenced by their support for amendments to the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. Conservative and religious MKs often opposed such measures, frequently framing equality issues in terms of majority rights or religious principles rather than universal human rights.

For example, MK Eitan Ginzburg, Chairman of the Blue and White faction, argued for the fundamental importance of the Equality Law proposal: “The time has come to anchor the value of equality in the Basic Law of the State of Israel. Equality of individual rights is one of the most basic principles in every democracy and in Israel.” In stark contrast, Likud MK Shlomo Krei characterized the same proposal as “absolute madness,” arguing that it would “impose an ultra-activist High Court of Justice on us, and completely remove the checks and balances that are already almost never used.” This exchange exemplifies how basic democratic principles become contested terrain in Israeli political discourse. (Berger)7.

The research showed that while initial party affiliation might reflect genuine ideological commitments to equality and rights, political position often came to override these values in practice. This was particularly evident in how MKs approached minority rights and anti-discrimination measures.

Populism and opportunistic democracy

The relationship between populism and political liberalism adds another layer of complexity to this analysis. Miscoiu (2012) provides a theoretical framework for understanding how populist discourse shapes political legitimacy, while Canihac (2022) explores this dynamic by examining the distinctions between anti-liberalism and post-liberalism. Mudde and Kaltwasser (2018) further develop this understanding by examining how populist movements operate across different political contexts. This theoretical framework is particularly relevant for understanding the rise of authoritarian populism, a phenomenon that Norris and Inglehart (2019) analyze in detail through their examination of global political trends.

The study identified significant use of populist rhetoric across the political spectrum, though with varying frequency and character. Conservative MKs more frequently employed populist appeals, often framing complex institutional issues in simplistic terms of “people versus elites.” This was particularly evident in debates over judicial reform and government formation. This tendency reached concerning extremes in some cases, as exemplified by MK Miki Zohar’s statement: “The public in the State of Israel is a public that belongs to the Jewish race, the entire Jewish race is the highest, smartest and most understanding human capital.”(Zoharin, 2022 in Alper, 2022) (said in public and in Facebook and TV several times). Such rhetoric reveals how populist appeals can merge with ethnonationalist ideologies.

Opportunistic interpretation of democratic principles was widespread, with many MKs adopting flexible positions on democratic norms based on immediate political needs. This tendency was most visible in how MKs shifted their positions on majority rights, coalition legitimacy, and institutional powers depending on their position in government or opposition.

Discussion and conclusions

The research reveals a concerning pattern in how Israel’s elected officials understand and commit to democratic principles. Rather than treating democracy as a fundamental system of governance, many Members of Knesset view it primarily as a tool for achieving political objectives. This instrumental approach particularly manifests in attitudes toward Basic Laws and judicial review, where many MKs show willingness to modify constitutional arrangements for immediate political gain.

A clear ideological divide emerges in how MKs approach democratic institutions. Liberal MKs emphasize substantive democratic values, including minority rights, institutional checks and balances, and the rule of law. In contrast, conservative MKs tend to advance a majoritarian conception of democracy that minimizes these constraints. Religious MKs frequently subordinate democratic principles to religious law, while non-Jewish MKs alternate between supporting liberal democratic principles and group-specific interests depending on the context.

The coalition system has contributed to democratic erosion by transforming the Knesset into what some describe as a “rubber stamp” for executive decisions. This weakening of legislative independence, combined with growing challenges to judicial authority, threatens the separation of powers fundamental to democratic governance. Additionally, the rise of populist rhetoric, with leaders claiming to represent the “true will of the people,” has been used to justify circumventing democratic checks and balances.

Israel’s case of democratic backsliding is both unique and universal. Its distinctiveness stems from two key factors: the ongoing challenge of balancing its Jewish and democratic identities, and the significant influence of ultra-Orthodox communities on political decision-making. However, the mechanisms of democratic decline parallel those seen in countries like Hungary, Poland, and Turkey, including the rise of personality-driven politics, populist movements, and leaders who prioritize personal agendas over democratic principles.

The research suggests that preserving Israeli democracy will require addressing both institutional reforms and the underlying attitudes of political leaders toward democratic principles. This dual approach must consider both the universal patterns of democratic decay and Israel’s unique characteristics as a Jewish and democratic state with significant religious influence in its political system.

The findings contribute to broader understanding of democratic backsliding, particularly in contexts where religious, ethnic, or nationalist identities compete with democratic principles. Israel’s experience demonstrates how elected officials’ conceptualization of democracy can either reinforce or undermine democratic institutions, with important implications for other democracies facing similar challenges.

This perspective suggests that solutions to democratic backsliding need to address both universal patterns and local conditions simultaneously. While some remedies might work across different countries, they must be adapted to address the specific challenges posed by Israel’s unique situation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform's terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

YA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Claude AI was used to help with the translation of the article (from Hebrew to English) and in making the manuscript more concise.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1530752/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Published in Yediot Ahronot (Hebrew) by Morag (2024) on May 27, 2024. See https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/by0dmhzer

2. ^Lin (1993). The Law Journal (Yearbook), 1: 81–89, 1993.

3. ^Facebook, April 2020, copy of post in Appendix D # 1.

4. ^Facebook, 7 June 2022 copy of post in Appendix D #2.

5. ^Facebook, 9 May 2022 copy of post in Appendix D #3.

6. ^Facebook, 20 October 2021 copy of post in Appendix D # 4.

7. ^Facebook, 3 December 2021 copy of article Shaharith newspaper in Appendix D #5.

References

Alper, R. (2022). The right wants “Jewish governance laws”. That would be a bullet to the head of democracy. Haaretz Hebrew. Avaialbe at: https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/television/tv-review/2022-05-20/ty-article/.highlight/00000180-e9f3-dc12-a5b1-fdfbb12a0000

Ágh, A. (2016). The decline of democracy in east-Central Europe: Hungary as the worst-case scenario. Prob. Post-Commun. 63, 277–287. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1113383

Canihac, H. (2022). Illiberal, anti-liberal or post-liberal democracy? Conceptualizing the relationship between populism and political liberalism. Politic. Res. Exchange 4:2125327. doi: 10.1080/2474736X.2022.2125327

Capoccia, G. (2005). Defending democracy: Reactions to extremism in interwar Europe. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chazan, N. (2020). Israel’s democracy at a turning point. Continuity and change in political culture, Israel and beyond: Rowman & Littlefield Lanham, MD. 93–116.

Cohen-Zada, D., Margalit, Y., and Rigbi, O. (2016). Does religiosity affect support for political compromise? Int. Econ. Rev. 57, 1085–1106. doi: 10.1111/iere.12186

Daly, T. G. (2019). Democratic decay: Conceptualising an emerging research field. Hague J. Rule Law 11, 9–36. doi: 10.1007/s40803-019-00086-2

Elstein, N. (2020). The constitutional crisis and prime ministerial eligibility. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Democracy Institute Working Paper.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Intertextuality in critical discourse analysis. Linguist. Educ. 4, 269–293. doi: 10.1016/0898-5898(92)90004-G

Filc, D. (2020). Who's afraid of populism?. Available at: https://pigumim.org.il/whose-afraid-of-populism/ (Published August 4, 2020) (Hebrew).

Foucault, M. (1970). The Order of Things: an archaeology of the human sciences. (London: Tavistock Publications) 9, 1972–1977.

Freedman, M. (2020). Vote with your rabbi: the electoral effects of religious institutions in Israel. Elect. Stud. 68:102241. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102241

Gidron, N., Margalit, Y., Sheffer, L., and Yakir, I. (2023). Who supports democratic backsliding? Evidence from Israel : OSF Preprints. Available at: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/zxukm_v1

Haggard, S., and Kaufman, R. R. (2021). Backsliding: Democratic regress in the contemporary world. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., and Verba, S. (1999). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Kremnitzer, M., and Shany, Y. (2020). Illiberal measures in backsliding democracies: differences and similarities between recent developments in Israel, Hungary, and Poland. Law Ethics o Human Rights 14, 125–152. doi: 10.1515/lehr-2020-2010

Linz, J. J., and Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Miscoiu, S. (2012). Au pouvoir par le Peuple! Le populisme saisi par la théorie du discours. Paris: l'Harmattan.

Morag, G. (2024). Attorney general: the nation is strong, the democracy is fragile. Yediot Ahronot. Available at: https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/by0dmhzer

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comp. Pol. Stud. 51, 1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0010414018789490

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oren, N. (2023). Democratic backsliding in Netanyahu's Israel. E-Int. Rel. 19, 1–15. Available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2023/05/19/democratic-backsliding-in-netanyahus-israel/

Ravitsky, A. (1993). Messianism, Zionism, and Jewish religious radicalism. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Samoha, S. (2000). The state of Israel's regime: a civil democracy, a non-democracy, or an ethnic democracy? Israeli Sociol. 2, 565–630.

Scheppele, K. L. (2018). Autocratic legalism. Univ. Chicago Law Rev. 85, 545–583. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26455917

Waldner, D., and Lust, E. (2018). Unwelcome change: coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628

Keywords: democracy, Israel, parliament, democratic backsliding, ideology

Citation: Arad Y and Freedman M (2025) The crises of Israeli democracy: political-ideological framings by members of Israel’s 24th Knesset. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1530752. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1530752

Edited by:

Eitan Tzelgov, University of East Anglia, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sergiu Miscoiu, Babeș-Bolyai University, RomaniaOsnat Akirav, Western Galilee College, Israel

Copyright © 2025 Arad and Freedman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Freedman, mrfreed@poli.haifa.ac.il

Yoav Arad

Yoav Arad