- School of Economics and Management, East University of Heilongjiang, Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

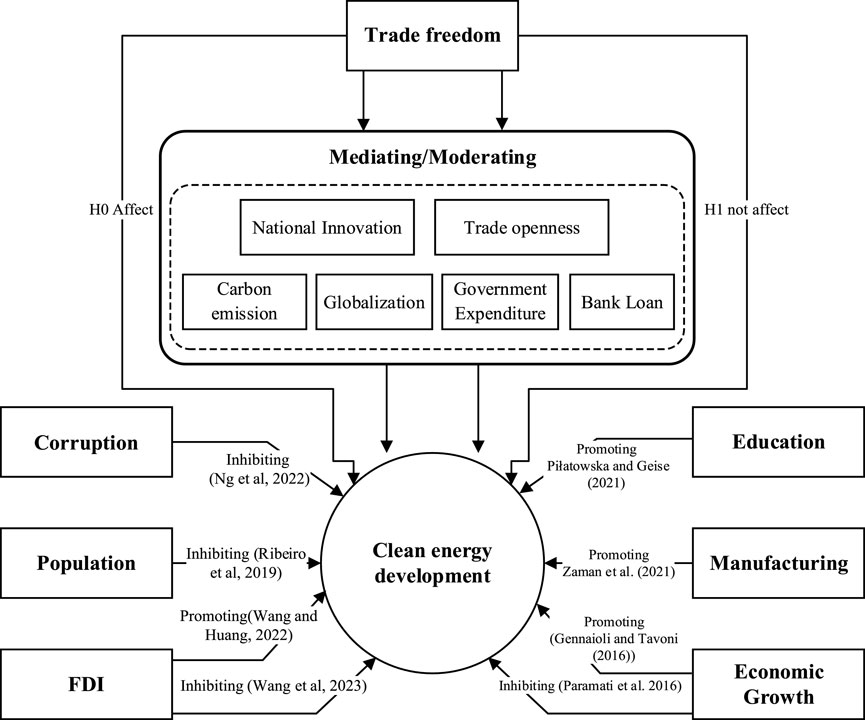

Changes in trade freedom affect national economic development and energy demand, which in turn affects clean energy development. This study assesses the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development in 114 countries from 2006 to 2020. Empirical testing shows that trade freedom significantly inhibits clean energy development in a linear manner. The results also indicate that higher GDP per capita and increased governmental capacity to control corruption are both important factors contributing to clean energy development. In addition, by incorporating mediating mechanisms, this study finds that trade freedom inhibits clean energy development by increasing a country’s innovation and trade openness. Finally, by exploring possible moderating effects, the results show that carbon emissions and bank lending weaken the negative effect of trade freedom on clean energy development, while globalization and government expenditure strengthen this effect. This study offers vital insights to policymakers in balancing the advancement of national trade liberalization policies with clean energy development.

1 Introduction

As climate change continues to be a growing worldwide problem, the production of clean energy has become crucial. Clean energy refers to forms of energy that produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions during production and use, such as solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass energy (Paraschiv and Paraschiv, 2023). Clean energy significantly alleviates air pollution, enhances energy diversity and security, and reduces dependence on fossil fuels (Chen et al., 2023). In addition, the development and application of clean energy technologies can facilitate the green transformation of the economy, promote technological innovation, and create new employment opportunities and economic growth points, thus bringing comprehensive benefits in economic, social, and environmental aspects (Ali et al., 2024). Promoting clean energy development is therefore of great significance for attaining the United Nations’ global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and addressing the challenges of climate change.

Trade freedom refers to the free movement of products and services internationally without interference from tariffs, quotas, and other restrictive policies (Cong et al., 2024a). With the acceleration of globalization, trade freedom is considered an important force for economic growth and technological progress (De Macedo et al., 2021). By lowering trade barriers and increasing market access, trade freedom can effectively enhance the efficiency of resource allocation and make it easier for countries to access, disseminate, and apply the latest clean energy technologies. It also facilitates international technology exchanges and cooperation, thus accelerating clean energy technology innovation and development.

However, trade freedom may also hurt clean energy. First, it may increase dependence on cheap fossil fuels, inhibiting market demand for and investment in clean energy. Cheap fossil fuels make businesses and consumers prefer traditional energy sources, thus slowing down the development of clean energy (Si et al., 2023). At the same time, trade freedom may lead to environmental deregulation in some countries to attract more foreign investment and trade, which may adversely affect the diffusion and application of clean energy technologies. In addition, trade freedom may trigger “carbon leakage”, which is when high-carbon-producing industries shift to nations with more lenient environmental policies, thus weakening emission reduction on a global scale.

Therefore, it is important to study the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development. On the one hand, it elucidates the link connecting global economic policies to environmental policies, thus providing a basis for more coordinated and effective policymaking. On the other hand, revealing the facilitating or inhibiting effects of trade freedom on clean energy development can provide practical guidance for countries to promote economic advancement hand in hand with environmental sustainability. Thus, explicitly examining the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development does not only address climate change and environmental protection but also provides strong support for the green transformation of the global economy.

National innovation capacity is an important indicator of a country’s scientific and technological level as well as its ability to apply technology (Furman et al., 2002). By promoting international technology exchange and cooperation, trade freedom enhances a country’s innovation capacity, thereby promoting the development and application of clean energy technologies. However, if trade freedom leads to an outflow of technology or a reduction in domestic R&D investment, this may inhibit the country’s innovative capacity and slow down the progress of clean energy technologies. Similarly, increased trade openness facilitates the cross-border transfer and diffusion of clean energy technologies and accelerates the clean energy development process of, but at the same time, it may lead to dependence on imported technologies and impede the country’s innovation. Thus, national innovation and trade openness may play a mediating role in the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy growth.

In addition, this relationship may be moderated by the level of national carbon emissions, the level of globalization, government expenditure, and bank credit. First, high-carbon emitting countries, facing greater environmental pressures and international regulatory constraints (Tao et al., 2023), may rely more on clean energy technologies, thus magnifying the favorable implications of trade freedom on clean energy development. However, if carbon emissions are less financially consequential, these countries may continue to rely on fossil fuels, inhibiting the development of clean energy. Second, globalization may intensify trade freedom’s promotion of clean energy development by facilitating international cooperation and technology transfer; however, it may also lead to a flow of technology and resources to more developed countries, undermining the likelihood of clean energy introduction in developing regions. Third, government expenditure on clean energy R&D and infrastructure development can support the diffusion of clean energy projects and enhance the positive effects of trade freedom. If government spending is insufficient, trade freedom may not be adequate to promote clean energy development. Finally, bank credit plays a key role in supporting clean energy projects by providing the necessary financial support and amplifying the promotional effect of trade freedom on clean energy development. At the same time, if bank credit is insufficient, the positive effect of trade freedom may be suppressed. By considering these moderating factors together, the complex impact of trade freedom on clean energy development can be more fully understood.

In the literature on clean energy, studies have focused on the conventional factors impacting clean energy, such as foreign direct investment (FDI) (Shahbaz et al., 2018), industrial development (Kahia and Ben Jebli, 2021), average temperature (Chen et al., 2021), green finance and renewable energy (Zhou and Li, 2022), living environment (Kilinc-Ata and Alshami, 2023), and carbon emissions (Zhang et al., 2023). However, the effect of trade freedom on clean energy development has not been widely studied to date, especially with regard to possible mediating and moderating factors. Therefore, to determine the influence of trade freedom on clean energy development via two key mediators (national innovation and trade openness) and four key moderators (national carbon emission levels, globalization levels, government expenditures, and bank credit), this study analyzes balanced panel data spanning from 2006 to 2020 for 114 nations. Through the aforementioned analyses, this paper hopes to provide new theoretical and empirical support for the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development, thereby contributing to the attainment of the global SDGs.

This study adds value to the existing body of knowledge in several areas. To begin with, we pioneer the systematic examination of the influence of trade freedom on clean energy development, addressing a crucial gap in current research. Second, based on the relevant literature, we propose and empirically verify the mediating factors (national innovation and trade openness) and moderating factors (national carbon emission levels, globalization levels, government expenditure, and bank credit) affecting trade freedom and clean energy development. These contributions provide new directions and rationales for future policymaking and academic research.

2 Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Literature review

This section first reviews research on the determinants of clean energy development, notably trade freedom. Subsequently, it discusses the development of the study’s hypotheses.

2.1.1 Theoretical background

The relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development is complex and multifaceted, and it can be understood through several theoretical frameworks. This study primarily adopts Technology Diffusion Theory, initially proposed by Nelson and Phelps (1966), to explain how international trade and investments foster technological progress and economic growth through the cross-border transfer of technology and knowledge. According to this theory, multinational corporations play a crucial role in transferring advanced technologies and managerial expertise from developed to developing countries, thereby promoting technological localization, innovation, and upgrades, particularly in the energy and environmental sectors. Stoneman and Diederen (1994) argue that public policies significantly influence the rate of technology diffusion through mechanisms such as education, research and development (R&D) investments, and market openness. Eaton and Kortum (1999) further examined the theory of international technology diffusion, emphasizing its role in global economic growth, and proposed empirical methods for measuring such diffusion. These contributions have enriched the Technology Diffusion Theory by underscoring the importance of policy environments and measurement methodologies in the technology diffusion process.

When applied to clean energy, Technology Diffusion Theory offers a compelling explanation for how trade freedom can enhance the development of clean energy technologies. International trade acts as a conduit for the flow of advanced clean energy technologies and knowledge from developed countries to developing ones, facilitating the adoption and implementation of these innovations. The liberalization of trade, through reduced tariffs and non-tariff barriers, further promotes the international flow and application of clean energy technologies, accelerating their diffusion globally. However, it is important to acknowledge that trade freedom can also have negative effects, such as encouraging the importation of cheap fossil fuels or weakening environmental regulations, both of which could impede clean energy development. Therefore, the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development is complex and requires a balanced examination of both positive and negative effects.

This study uses Technology Diffusion Theory as the primary framework to explore how trade freedom influences clean energy development, while also considering the mediating roles of national innovation systems and policy frameworks. These factors significantly shape the extent to which trade freedom can positively or negatively affect clean energy diffusion. This theoretical exploration addresses gaps in the current literature and enhances understanding of the dynamic relationship between trade openness and clean energy development.

2.1.2 Empirical literature review

A significant body of empirical research has explored the factors influencing clean energy development, including foreign direct investment (FDI), financial market development, and environmental policies. For example, Paramati et al. (2016) demonstrated that FDI inflows and stock market development positively affect clean energy adoption in emerging markets. Similarly, Shahbaz et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of capital flows and financial market development in facilitating clean energy adoption. Chen et al. (2021) found that environmental pressures, such as climate change, directly influence clean energy production, driving both market expansion and technological innovation. Additionally, Usman et al. (2021) analyzed EU-28 data and concluded that globalization and poor institutional quality act as barriers to clean energy development.

Despite the significant amount of literature exploring the role of trade in clean energy, there remains a gap in directly analyzing the impact of trade freedom as an independent factor. Most studies focus on individual variables like FDI, financial market development, or environmental policy, rather than considering the broader role of trade openness as a structural factor influencing clean energy development. Studies like Feng et al. (2024) and Uzar (2023) have begun to investigate this gap, suggesting that trade freedom has important implications for renewable energy strategies and consumption. For instance, Feng et al. (2024) explored how countries’ positions in energy trade networks influence their renewable energy strategies, finding that trade relations significantly shape renewable energy adoption. Uzar (2023) examined the role of press freedom and trade openness in renewable energy consumption in OECD countries, showing that trade openness, while important, may not always have a statistically significant impact on renewable energy consumption. Alola et al. (2023) examined the relationship between economic freedom and environmental sustainability, suggesting that while some aspects of economic freedom, such as trade freedom, can hinder environmental sustainability, renewable energy efficiency plays a crucial role in mitigating these effects. This gap in the literature emphasizes the need for further research into the direct role of trade freedom in clean energy development, particularly in terms of how it interacts with technological diffusion, national innovation systems, and policy frameworks. Studies like Chen et al. (2021) and Amoah et al. (2020) have begun to address this by examining how trade freedom, combined with business and property rights, positively influences renewable energy consumption.

2.1.3 Trade freedom and clean energy development

Recent studies have started to explore the interaction between trade freedom and clean energy development, though much of the existing literature focuses on indirect factors such as governance, energy trade patterns, and renewable energy policies. For example, Feng et al. (2024) examined the relationship between traditional energy trade and renewable energy development, finding that a country’s position in global energy trade networks significantly influences its renewable energy strategies. Similarly, Hussain et al. (2021) analyzed renewable energy investments in Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries, highlighting the role of trade openness, political stability, and regulatory quality in driving renewable energy investments in developing countries. However, these studies have not directly assessed the impact of trade freedom itself on clean energy development.

Several studies have attempted to explore the direct influence of trade freedom on clean energy outcomes. For example, Zhang et al. (2021) studied the nonlinear relationship between trade openness and renewable energy consumption in OECD countries, finding that trade openness (measured by imports, exports, and total trade) positively impacted renewable energy consumption, although with varying effects across countries and regions. Huang, 2023 found that trade openness and fiscal decentralization both promote renewable energy development and green growth in China, suggesting that trade liberalization can play a crucial role in fostering clean energy transitions. Moreover, Murshed (2020) investigated the role of ICT trade in renewable energy transitions in South Asia, finding that ICT trade directly promotes renewable energy consumption, improves energy use efficiency, and reduces carbon emissions. Similarly, Yang et al. (2024) observed that service exports positively impact sustainability in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA) region, while service imports have a negative effect on sustainability.

In summary, while some studies have acknowledged the importance of trade freedom in clean energy development, there is a lack of comprehensive analysis on how trade freedom interacts with national innovation systems, technological diffusion, and policy frameworks. The need for further research in these areas is clear, as moderating factors such as carbon emissions, globalization, and government expenditure have not been fully explored.

2.1.4 Contribution of the study

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature by providing a comprehensive analysis of how trade freedom influences clean energy development, focusing on both direct and indirect mechanisms. While existing research has explored the role of FDI, financial markets, and environmental policies in clean energy adoption, few studies have directly examined the impact of trade freedom itself on the diffusion and implementation of clean energy technologies across different countries. Additionally, this study expands on previous work by incorporating mediating factors such as national innovation systems, technological diffusion, and policy frameworks into the analysis. These factors play a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of trade freedom in promoting clean energy adoption. Furthermore, this study will examine moderating factors such as carbon emissions, globalization, and government expenditure, providing insights into how these variables interact with trade freedom to shape clean energy outcomes.

By addressing these gaps, this study provides a more nuanced understanding of the complex relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development. The findings of this study have important implications for policymakers seeking to optimize trade policies to promote the global spread of clean energy technologies, thereby contributing to sustainable development goals.

2.2 Hypothesis development

Freedom of trade facilitates the cross-border flow of clean energy technologies and equipment by reducing trade barriers and increasing market access (Trebilcock and Fishbein, 2007). Advanced clean energy technologies from developed countries can be rapidly disseminated to developing countries through international trade, fueling the production and application of clean energy technologies in these countries (Pfeiffer and Mulder, 2013). In addition, trade freedom has enabled multinational corporations to bring their advanced technologies and management experience accumulated in developed countries to developing countries through direct investment and cooperation, thus upgrading the energy structure and environmental quality of these countries (Staff, 2001). Trade freedom also promotes competition in the global market and motivates enterprises to innovate and develop more efficient and environmentally friendly clean energy technologies.

However, freedom of trade may also have a dampening effect on clean energy development. Higher trade liberalization makes market access between countries easier, which may lead to increased dependence on cheaper fossil fuels in some countries as these fuels have a short-term cost advantage. In addition, trade freedom may lead to environmental deregulation in some countries to attract more international investment and trade. Such deregulation may hurt the diffusion and application of clean energy applications, undermining the competitiveness of clean energy in the marketplace. In some countries, trade freedom may further lead to changes in industrial structure, whereby traditional high-energy-consuming and high-polluting industries may expand as a result of increased demand in the international market, thus posing a challenge to clean energy advancement. Therefore, we hypothesized the following at the 10% significance level (α = 0.1):

Hypothesis 1. H0: Trade freedom affects clean energy development.

H1: Trade freedom does not affect clean energy development.

Based on the discussions in the preceding sections, Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive analytical framework of this study.

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Dependent variable

Clean energy development (Clean): Clean energy development refers to the development, promotion, and utilization of forms of energy that have a low or no impact on the environment, with the aim to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and promote sustainable development (Tee et al., 2021). Clean energy includes various forms of energy such as wind, solar, hydro, geothermal, and biomass. Therefore, this study followed Alola and Saint Akadiri, (2021) method of measuring the total use of alternative and nuclear energy as a percentage of total energy use using the World Bank’s database.

3.2 Independent variables

Trade Freedom (Freedom): Trade freedom refers to the free flow of goods and services between countries without interference from tariffs, quotas, and other restrictive policies. Freedom of trade aims to reduce or remove barriers to trade between countries to facilitate the development of international trade. Therefore, referring to the study of Cong et al. (2024a), this paper used the national trade freedom index constructed by the Heritage Foundation as a measure of trade freedom. The index is a comprehensive indicator of the degree of national trade freedom development, as it specifically includes quantitative restrictions, regulatory restrictions, customs restrictions, direct government intervention, non-tariff measures, and other aspects.

3.3 Mediating variables

National Innovation (Innovation): National innovation refers to the progress of science and technology and the development of innovative activities in a country through the concerted efforts of institutions, policies, technologies, talents, and other factors to enhance the country’s competitiveness, economic growth, and social progress (Watkins et al., 2015). Following Raghupathi and Raghupathi (2017), we use the number of patents applied by residents as a measure of national innovation, assuming that a higher number of patents indicates a higher level of innovation. However, using patent data as a proxy for innovation has both advantages and limitations. On the positive side, patents provide a quantifiable measure of technological output, reflecting a country’s inventive activity. They are widely available and comparable across countries, making them useful for cross-country analysis. On the downside, patents may not capture all forms of innovation, especially in industries where patents are not commonly used or for incremental innovations. Additionally, the quality and impact of patents can vary, and factors like changes in patent laws or firms’ strategic behavior may influence patenting activity, which might not fully reflect a country’s true innovation capacity. Despite these limitations, patent data remains a practical and widely accepted measure of innovation, especially in cross-country studies, due to its availability and ability to quantify technological progress.

Trade openness (Openness): Trade openness refers to a country’s efforts to promote the free flow of goods, services, capital, and technology by reducing or eliminating various restrictions and barriers to international trade, such as tariffs, quotas, and other trade limits (Fenira, 2015). Trade openness aims to enhance competitiveness in the international market, optimize resource allocation, increase productivity, and promote economic growth and employment opportunities (Kalu and Joy, 2015). To measure national trade openness, we referred to Sakyi et al. (2015) and employed the total value of international trade exports plus imports as a percentage of the country’s GDP, with a higher percentage indicating a higher level of national trade openness.

3.4 Moderating variables

Carbon emission (Carbon): Carbon emission is the process by which carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere as a result of human activities such as fossil fuel burning, industrial production, transport, agricultural activities, and deforestation (Huisingh et al., 2015). The emission of carbon dioxide is among the foremost drivers of climate change, spiking the greenhouse effect and the Earth’s average temperature (Liu et al., 2019). To measure national carbon emissions, we referred to Chaabouni and Saidi (2017) and employed per capita carbon dioxide emission, whereby the higher it is, the higher the level of national carbon emissions.

Globalization (Global): Globalization is the process of deepening interconnections and interdependence between countries around the world in the fields of economy, culture, politics, science, and technology (Song et al., 2018). Following Savićević et al. (2022), we utilized the globalization index provided by The Swiss Institute of Technology in Zurich to measure globalization, where a higher index value indicates a higher level of national globalization.

Government Expenditure (Gov): Government expenditure is the money spent by the government on the provision of public services and implementation of policies (Nganyi et al., 2019). These expenditures include costs of infrastructure development, education, healthcare, social security, defense, public safety, and environmental protection. Government expenditures are managed through the fiscal budget to promote economic growth, improve social welfare, and maintain national security (Jaelani, 2017). To measure national government expenditure, this study followed Cong et al. (2024b) and evaluated government expenditure as a percentage of GDP, where the higher the percentage, the higher the extent of government expenditure in the country.

Bank Loan (Loan): A bank loan is a loan provided by a bank to an individual, business, or other institution to meet its short-term or long-term financial needs (Eichengreen and Mody, 2000). Loans usually require collateral or guarantees from the borrower and are repaid in installments based on an agreed interest rate and term (Krasniqi, 2022). To measure the level of bank lending, this study, in reference to Yudaruddin (2020), chose to measure bank credit to government and public enterprises as a percentage of GDP, with a higher percentage indicating a larger bank loan.

3.5 Control variables

In determining the effect of trade freedom on clean energy development, control variables must be added to improve the accuracy and reliability of the findings. Referring to Gennaioli and Tavoni (2016), Paramati et al. (2016), Zaman et al. (2021), Piłatowska and Geise (2021), Ng et al. (2022), and Doblinger et al. (2022), this study incorporated the following control variables at the national level: (i) economic development (GDP), measured as national GDP per capita; (ii) population size (Population), measured as the total population of the country; (iii) FDI (FDI), measured as FDI as a percentage of GDP; (iv) perceived level of corruption (Corruption), measured using the Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International; (v) public expenditure on education (Education), measured as the share of public education expenditure in GDP); and (vi) manufacturing development (Manufacturing), measured as the value added of the manufacturing industry. It is expected that economic development, FDI, and corruption perception have a catalytic impact on clean energy development. In contrast, the impact of population size, public education expenditure, and manufacturing development on clean energy development may be either catalytic or inhibitory, to be determined through empirical analyses.

3.6 Data description

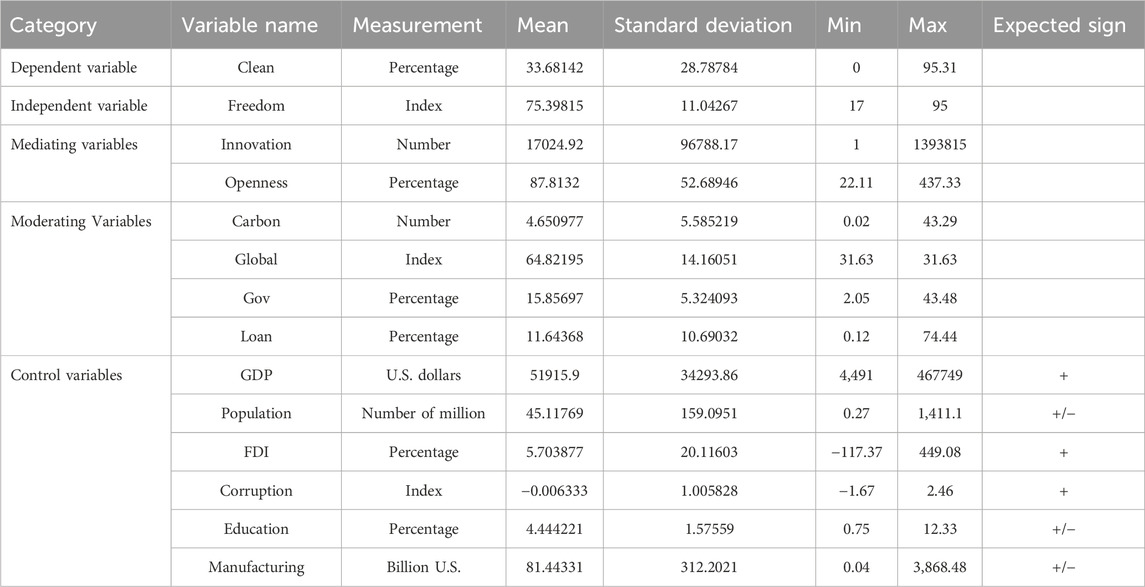

Due to data availability, the panel data for this study covered 114 countries for the period 2006–20201. Data were obtained from the World Bank Development Database, The Heritage Foundation, The Swiss Institute of Technology in Zurich, and other reliable sources. Table 1 presents the results of descriptive analysis for the full sample. In addition, multiple covariance tests were conducted. The results show that all variables have variance inflation factor (VIF) values less than five, ruling out multicollinearity2.

3.7 Empirical methodology

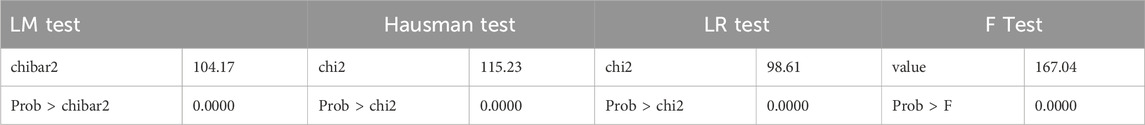

Referring to Cong et al. (2023), the connection between trade freedom and clean energy was analyzed using a two-way fixed effects model. This model is particularly suitable for the study as it allows for the simultaneous control of both country-specific and time-specific factors. Specifically, the two-way fixed effects approach accounts for unobservable heterogeneity across countries (such as differences in national policies, institutional quality, and economic structures) and over time (such as changes in global economic conditions and technological advancements). By controlling for these fixed effects, potential biases arising from these unobserved factors are eliminated, thereby enhancing the accuracy of model estimation and the reliability of the results.

The choice of a two-way fixed effects model is further motivated by the nature of the data, which spans multiple countries over several years. This methodology is well-suited for panel data settings, where both cross-sectional and temporal variations need to be captured. Moreover, it addresses issues such as omitted variable bias, where key confounders may vary across countries and over time but are not directly observable.

All variables were transformed into logarithmic form to minimize heteroskedasticity, ensuring that all minimum values were greater than or equal to one. Robust standard errors were used in the regressions to account for heteroskedasticity, and the t-statistics reported in parentheses are based on these robust standard errors. All variables were incorporated into the fixed effects model, estimated in Equations 1, 2. To assess the potential nonlinear effect of trade freedom on clean energy development, panel data Equations 3, 4 were constructed by including the squared term of Trade in the model. If a nonlinear relationship exists, α1 and α2 would exhibit opposite signs and be statistically significant. To further ensure the robustness of the non-linear relationship, a U-test was conducted. If the U-test fails to indicate the presence of a non-linear relationship, the squared term of Trade was removed from the model, and subsequent estimations proceeded with Equations 1, 2.

In Equation 2, W refers to the control variables.

Multiple robustness tests were performed in this study to examine the reliability of the baseline regression results. Given potential shortcomings in the research design, the effect of trade freedom on clean energy revealed by the baseline model could be a placebo. To verify this, a placebo test was conducted in reference to the methodology of Cong et al. (2023). We first deleted each sample’s data before re-assigning the data randomly to other samples, and re-estimated Equation 2 based on the revised data. If the Trade-Clean relationship in the baseline estimation is not a placebo, then the placebo assessment would not show causality.

Despite the use of a panel fixed-effects regression model to reduce the impact of systemic issues, endogeneity problems may still exist and affect the validity of the results. To address this issue, we used an instrumental variable approach, employing the first-order lag term of Trade as an instrumental variable. Changes in this lagged variable would not directly affect clean energy, corresponding to the exclusionary instrumental variable hypothesis, thus satisfying the correlation requirement. We tested this via two-stage least squares to ensure that the endogeneity issue was effectively dealt with. Finally, based on the suggestion of Lin et al. (2021), we adopted the system GMM approach as a robustness test. The explanatory constructs’ lagged values were introduced as instrumental variables in the panel data model, as shown in Equation 5. The system GMM approach is particularly suitable for addressing endogeneity issues, which may arise due to the potential correlation between the explanatory variables and the error terms. By using lagged values as instruments, this method helps mitigate the biases that might arise from reverse causality or omitted variable bias. Additionally, system GMM allows for more efficient estimation in the presence of potential heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation, which are common in panel data settings. Therefore, the system GMM approach provides more reliable and consistent estimates, further validating that the benchmark model estimation is robust and dependable.

Next, we developed a regression equation to test the mediating effects of national innovation and trade openness. First, based on the significance of the coefficients α1 and α2 in the main Equation 2, we constructed a linear regression equation (Equation 6) for the independent variable trade freedom (Ln (Trade)) and Ln (Innovation). Then, we built another linear regression equation (Equation 7) for Ln (Trade), Ln (Innovation), and the dependent variable clean energy (Ln (Clean)). We then tested the significance of the regression coefficients β and γ to determine whether a mediating effect exists.

Similarly, we constructed Equation 8 and Equation 9 for the mediating variable trade openness (Ln (Openness)) to test the significance of the regression coefficients β and γ and determine whether the mediating effect exists.

To investigate whether carbon emissions, globalization, government expenditure, and bank loans play a moderating role in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy, Equations 10–17 were constructed. Equations 10–13 represent the effects of each respective moderating variable on clean energy, whereas Equations 14–17 represent their moderating effect on clean energy via their interaction with trade freedom.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Baseline estimation model results

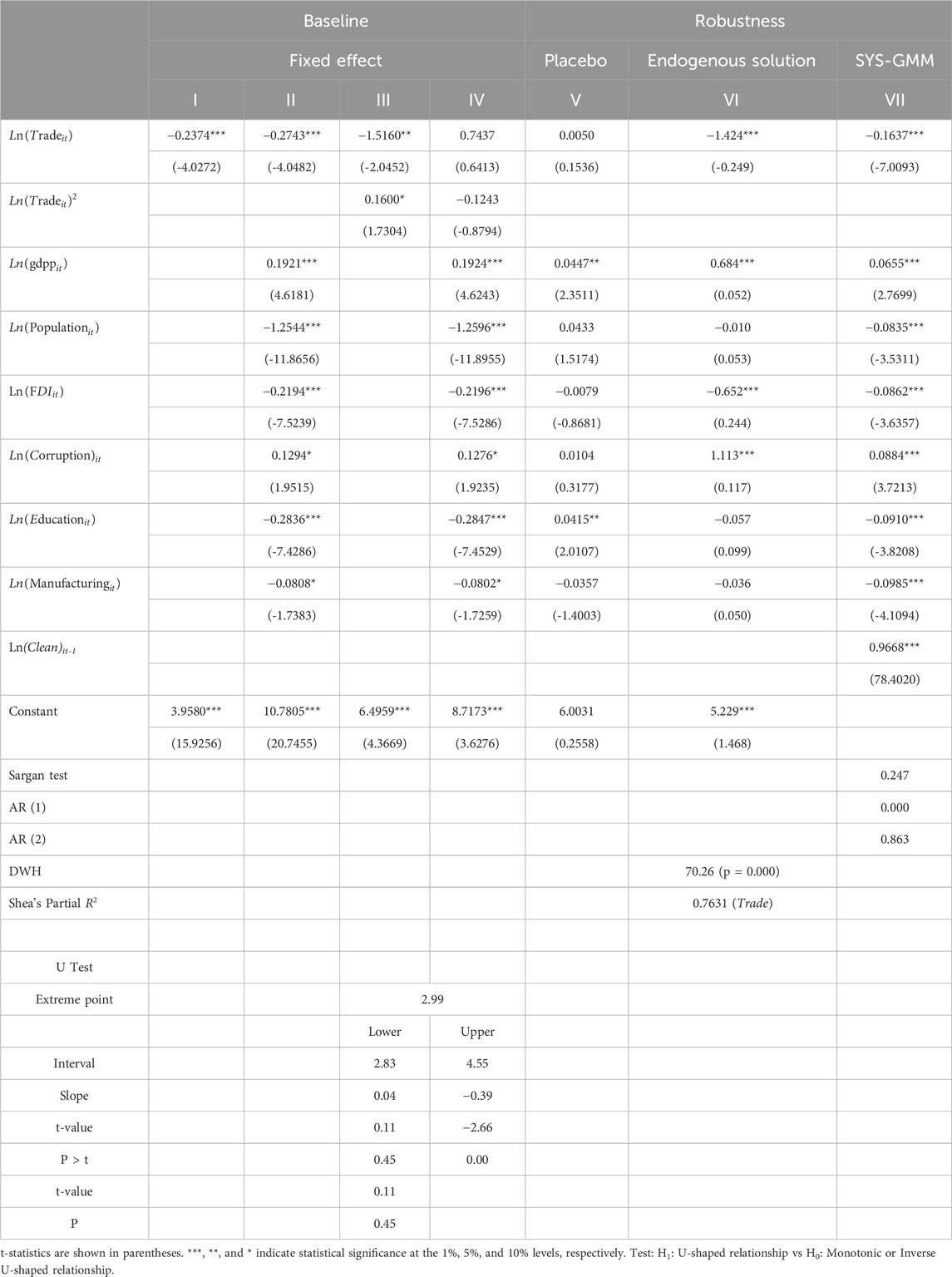

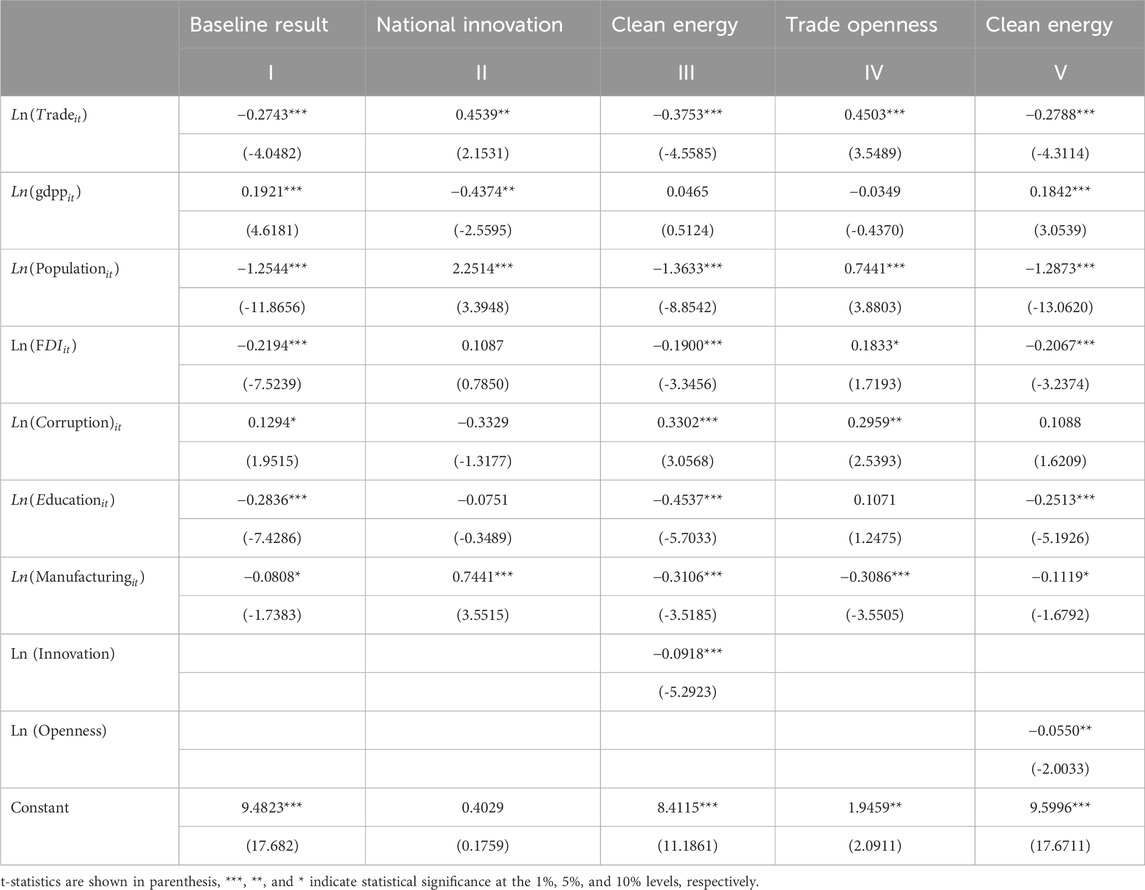

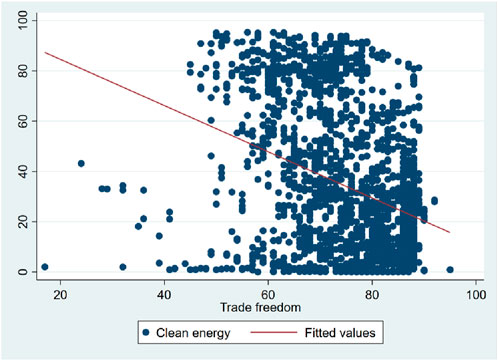

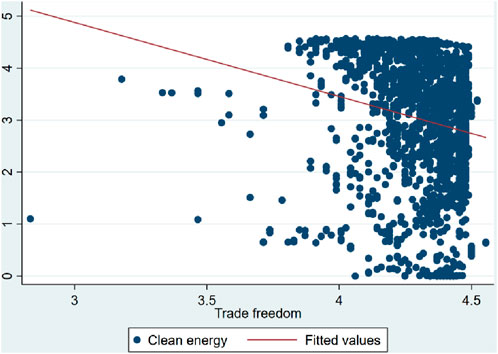

Columns I to IV of Table 3 show the baseline test results. Columns I and III do not contain control variables, while Columns II and IV include control variables. The empirical results in Columns I and II show that trade freedom significantly and negatively influences clean energy development, proving that Hypothesis H0 holds. This finding is consistent with the studies by Usman et al. (2021), which found that trade openness, particularly in developing countries, often promotes economic activities that are carbon-intensive, leading to negative impacts on clean energy development. This is also in line with the work of Zhang et al. (2021), who observed a similar negative relationship between trade openness and renewable energy consumption in OECD countries, especially when trade liberalization led to increased reliance on traditional energy sources in certain regions. Next, Columns III and IV indicate that the squared terms of Trade are not significant, and the U-test results have a p-value greater than 0.1, confirming that there is no non-linear relationship between trade freedom and clean energy. Therefore, trade freedom linearly inhibits clean energy development, likely because trade liberalization is accompanied by increased economic activity, especially in developing countries and emerging markets, which may lead to the expansion of highly polluting or carbon-emitting industries and exert competitive pressure on clean energy development. These findings resonate with Hussain et al. (2021), who analyzed renewable energy investments in BRI countries, emphasizing how trade openness often leads to the prioritization of industries with higher carbon footprints, thereby hindering the development of clean energy. In addition, the opening up of international markets due to trade freedom may lead to local clean energy enterprises being squeezed out by mature technologies and cheap products from abroad, weakening the development space and competitiveness of the local clean energy industry. This result mirrors the findings of Chen et al. (2021), who argued that trade liberalization and foreign competition could crowd out local clean energy industries in developing countries, particularly when foreign technologies are not adapted to the local context or are too cost-effective to encourage the growth of domestic alternatives. Two scatter plots were created to further support this analysis and illustrate the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development. Figure 2 shows the relationship without log-transformation, while Figure 3 is log-transformed for both variables. Both plots include fitted regression lines to highlight the empirical relationship, with the log-transformed plot providing a clearer depiction of the trend and making the results more consistent with the model used in the empirical analysis.

Figure 2. Scatter-plot of the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development (not logarithmic).

Figure 3. Scatter-plot of the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development (logarithmic).

Among the control variables, national economic development and corruption perception were found to significantly promote clean energy development. This suggests that economic prosperity and a good governance environment have a positive impact on clean energy. Sohag et al. (2019) highlighted similar findings, asserting that more economically developed nations can allocate greater financial resources toward clean energy R&D and technological infrastructure, which in turn boosts clean energy adoption. Moreover, lower corruption levels imply that the government is more transparent and efficient in policy formulation and implementation, which is conducive to clean energy policy enforcement and the market environment. This further promotes the development of clean energy, supporting the findings of Hamann et al., 2023, who found that governance quality was positively associated with clean energy adoption.

On the other hand, national population size, FDI, public expenditure on education, and manufacturing development were all found to exert a significant inhibitory effect on clean energy development. This may be due to a combination of complex factors. First, large populations are usually accompanied by rapidly growing energy consumption and energy demand for residential electricity, transport, and industrial production. This leads to greater reliance on traditional energy sources, thus weakening the share of clean energy in the energy mix. This finding is consistent with Mottaleb and Rahut, (2021) analysis, which focused on India, where traditional energy consumption remains dominant due to rapidly growing energy demands in the residential and industrial sectors.

Second, if the capital and technology brought in by FDI flows mainly to high-carbon-emitting traditional energy sectors or more polluting manufacturing sectors, it can skew resource allocation towards these areas, reducing investment efforts in clean energy. Lee’s (2013) panel data study of 19 G20 countries found that FDI did not significantly impact clean energy development, supporting the hypothesis that FDI inflows may be directed toward traditional industries rather than emerging clean energy sectors. This inconsistency might be due to differences in the time period and country samples used in the current study, as we examine data from 114 countries over a more recent period (2006–2020), reflecting contemporary clean energy trends.

Increased public spending on education, while raising the overall quality and education level of a nation, may divert household and societal attention away from investment in clean energy in the short term. High expenditure on education means that the government’s limited resources are prioritized towards improving the education level, weakening financial support for clean energy projects and investment in technological R&D. Nowotny et al. (2018) similarly argued that, although education plays a vital role in long-term economic development, it can divert short-term resources from sectors like clean energy.

Lastly, the development of the manufacturing industry is usually dependent on a stable supply of traditional energy sources. Manufacturing industries, especially heavy ones, require large amounts of energy to maintain production operations. This has led to a preference for traditional fossil fuels, which are less expensive and have a stable supply, over cleaner energy sources, which are more expensive and have an unstable supply. This phenomenon is highlighted in Zhang et al. (2021), who found that industrial development often leads to greater reliance on fossil fuels, especially in developing economies where energy costs and stability are major concerns.

This study makes a substantial contribution to the literature by addressing the complex relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development. Previous studies have generally focused on the impacts of FDI, manufacturing, or governance on clean energy, but the specific role of trade freedom has not been explored as comprehensively. By incorporating both the direct and indirect effects of trade freedom, this study expands the understanding of how trade policies influence clean energy transitions in both developed and developing countries.

The negative relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development observed in this study is consistent with Feng et al. (2024) and Alola et al. (2023), who highlighted the negative side effects of trade liberalization on environmental sustainability. However, this study goes further by examining the underlying mechanisms, such as competition from foreign industries and resource misallocation due to FDI, which were not fully addressed in the existing literature.

4.2 Robustness checks results

Robustness testing is an important step in research to ensure that results are reliable and valid. In this paper, the robustness of the baseline regression was verified through a variety of methods, namely, a placebo test, endogeneity test, and the system GMM model. First, the placebo test findings in Table 3 confirmed the non-significance of trade freedom’s coefficient as well as its significant difference from the baseline result. This verifies that the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development is real and not a placebo. Second, the endogeneity test pointed to the presence of endogeneity among the explanatory constructs based on the significance level of the DWH test statistic (p = 0.000 < 0.01). This result prompted us to use two-stage least squares to correct for possible endogeneity bias, where we found that trade freedom has a significant inhibitory effect on clean energy development. This is consistent with the baseline regression results, reiterating the accuracy and consistency of the model estimation. We further verified the validity of the instrumental constructs and ruled out the issue of weak instrumental constructs through Shea’s partial R2. Finally, the estimation results of the system GMM model were generally consistent with the baseline regression. The lagged variable of clean energy showed a positive coefficient, suggesting that in the future, cities with better clean energy will have higher development potential. These results not only strengthen confidence in the baseline model but also provide theoretical and empirical support for further research on policy recommendations for clean energy development.

4.3 Mediating effect analysis

To investigate the mediating effect of national innovation between trade freedom and clean energy development, we first use Equation 6 to estimate the impact of trade freedom on national innovation. As shown in the second column of Table 4, trade freedom significantly promotes national innovation, which is consistent with the findings of Martins et al. (2023). This indicates that trade freedom not only enhances national innovation capabilities but also promotes technological progress that may affect clean energy development. Rodrik (2018) and Yang et al. (2020) also found similar positive effects of trade liberalization on national innovation, particularly in developing countries where trade openness facilitates the flow of new technologies and ideas. These innovations can then spill over to various sectors, including energy, which may foster advancements in both traditional and clean energy technologies.

Interestingly, the results show that national innovation hurts clean energy development. Although trade liberalization can promote national innovation, such innovation seems to be more conducive to traditional energy and high-carbon industries than to clean energy. This result echoes the work of Brunnschweiler (2010), who observed that innovations often focus on enhancing the efficiency of conventional energy technologies rather than advancing clean energy solutions. Similarly, Blanchard and Brancaccio, (2019) argued that while trade liberalization stimulates technological development, it may inadvertently divert innovation resources toward high-carbon industries, especially when the market incentives and infrastructure for clean energy are underdeveloped.

When national innovation is included as a mediating factor, the inhibiting effect of trade liberalization on clean energy increases. This may be because research and development activities and technological progress driven by national innovation tend to be biased towards traditional energy sectors, thereby exacerbating the adverse impact of trade liberalization on clean energy. This phenomenon has been highlighted in Alola et al. (2023), who found that national innovation driven by trade openness often prioritizes short-term technological gains in fossil energy sectors rather than long-term sustainable solutions. Thus, the link between trade freedom and clean energy development becomes more complex, as innovation driven by trade freedom may fail to address the urgent need for clean energy advancements.

In Columns IV and V of Table 4, we explore whether trade openness mediates the process through which trade freedom influences clean energy development. First, Equation 8 was used to examine the effect of trade freedom on trade openness. Column IV shows that the coefficient of Ln (Trade) is positive and significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that trade freedom is conducive to increasing trade openness. This result is consistent with the findings of Usman et al. (2021), who argued that trade openness facilitates the exchange of technologies and expertise, which can have a positive impact on energy transitions. Moreover, Eberhardt et al. (2023) emphasized that trade openness leads to the diffusion of cleaner technologies and practices, particularly in countries that already have the infrastructure and capacity to adopt these innovations.

Equation 9 was then used to explore whether trade openness serves as a mediator in the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development. As shown in Column V, after adding trade openness as a mediating variable, the coefficient of the impact of trade freedom on clean energy becomes larger in absolute value compared to Column I, suggesting that trade freedom facilitates the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development through trade openness. This is consistent with Ibrahiem and Hanafy, (2021), who found that trade openness enhances access to clean energy technologies and encourages countries to adopt more sustainable energy practices. However, this effect may not be uniform, as Miyamoto et al. (2020) noted that trade liberalization might lead to an increased dependence on fossil energy if trade policies favor the importation of cheaper, high-carbon products or technologies.

These results further suggest that while trade openness enhances the impact of trade freedom on clean energy, the relationship is more complex. The fostering of economic growth through trade openness can inadvertently lead to greater investments in high-carbon industries, especially in countries with limited renewable energy infrastructure. Brock et al. (2022) warned that trade liberalization could inadvertently support the growth of energy-intensive industries, which may undermine efforts to transition to clean energy. Kojima, (1964) argued that in the short term, trade openness may stimulate the expansion of traditional energy sectors, especially in developing countries where infrastructure and technological readiness for clean energy adoption are limited.

The results suggest that trade freedom can have a paradoxical effect on clean energy development, as it fosters both positive and negative pathways. On one hand, trade openness can stimulate economic growth and increase access to clean energy technologies, as noted by Mora et al. (2023). On the other hand, trade liberalization can inadvertently strengthen traditional energy industries by promoting the flow of capital and technology into high-carbon sectors, which can counteract the progress made in clean energy development. As Stern (2022) points out, trade policies that prioritize economic growth without considering environmental impacts may lead to the continued dominance of fossil energy, especially in emerging economies.

The results also highlight the critical role of innovation in shaping the trajectory of clean energy development. While innovation driven by trade liberalization can be a powerful force for technological progress, the focus of this innovation on traditional energy sectors can slow down the transition to cleaner energy alternatives. This underscores the need for targeted policies that encourage innovation in the clean energy sector, especially in developing countries where trade openness and technological diffusion might otherwise promote high-carbon industries.

4.4 Moderating analysis

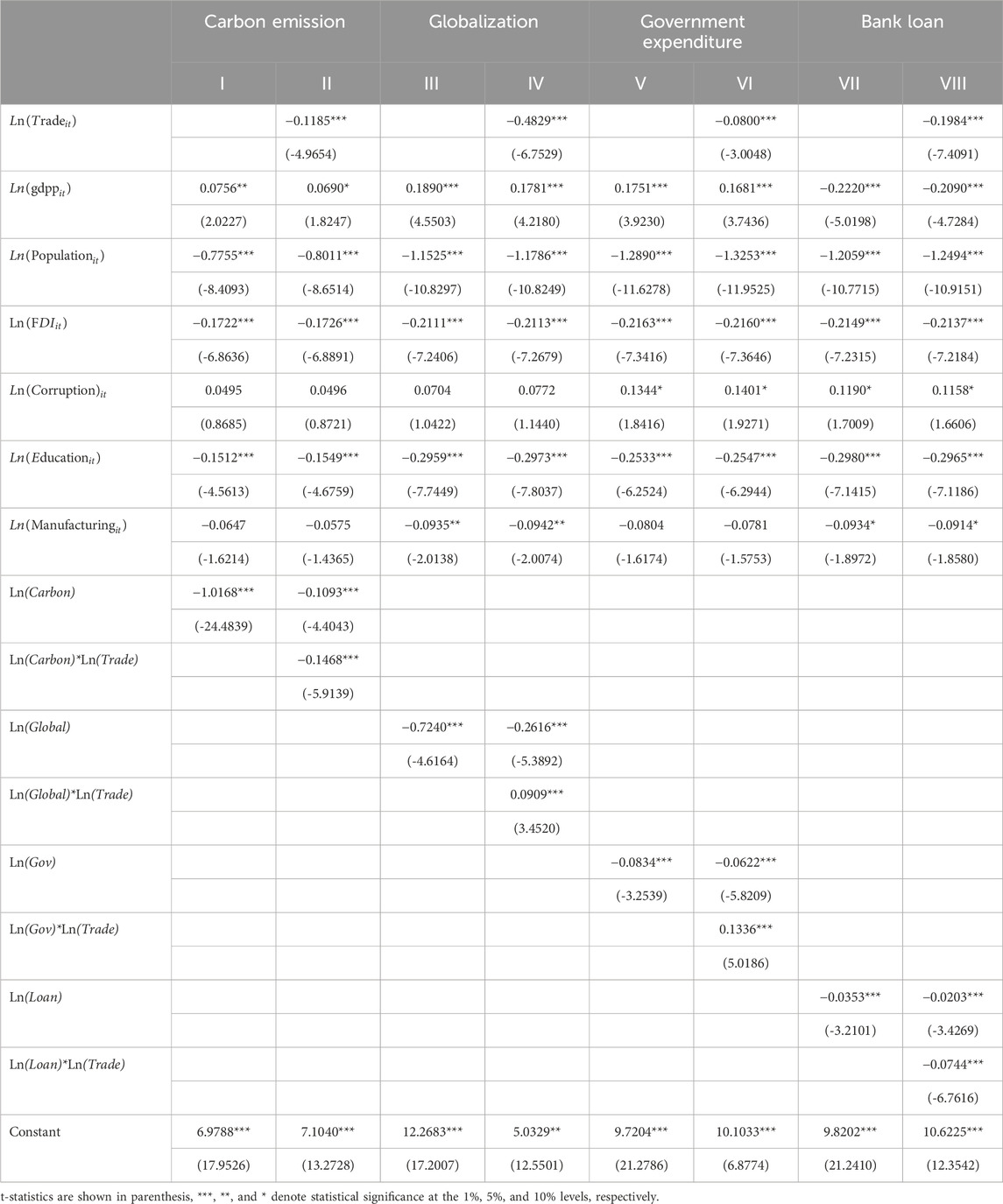

Columns I and II of Table 5 test the moderating effect of carbon emissions. Equation 10 was first used to explore the effect of carbon emissions on clean energy, and the results in Column I indicate that carbon emissions significantly inhibit clean energy development, which aligns with findings from Martins et al. (2023) and Feng et al. (2024). This is consistent with the view that carbon-intensive sectors, which dominate in many countries with high carbon emissions, crowd out investments in clean energy technologies. This phenomenon has been documented in Kojima, (1964), who found that carbon-intensive industries are often the primary recipients of capital in high-emission countries, thereby limiting the financial resources available for cleaner technologies. Then, Equation 14 was used to assess the moderating effect of carbon emissions in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy. The results in Column II indicate that the estimated coefficient of the interaction term, Ln(Trade)*Ln(Carbon), is negative, which suggests that carbon emissions negatively moderate the influence of trade freedom on the development of clean energy, such that the inhibitory effect of trade freedom on clean energy strengthens when the country’s carbon emissions increase. This suggests that high carbon emission levels exacerbate the negative environmental effects of trade freedom, causing resources and investments to flow more to traditional energy and polluting manufacturing industries with high carbon emissions rather than to the clean energy sector. This finding supports the conclusions of Usman et al. (2021), who argued that carbon-intensive sectors often absorb the benefits of trade openness, hindering clean energy investment. Jiang et al. (2020) also noted that countries with high levels of carbon emissions face challenges in transitioning to cleaner energy due to the entrenched interests of fossil fuel sectors.

Columns III and IV of Table 5 test the moderating effect of globalization in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy. Equation 11 was first used to determine the relationship between globalization and clean energy, for which the results in Column III indicate that globalization significantly inhibits clean energy development. This result aligns with Pereira, 2021, who found that, in some cases, globalization can lead to the prioritization of traditional energy sectors, especially in developing economies, where the global market demand for fossil fuels is high. The inflow of capital and technology from globalization may thus reinforce reliance on high-carbon industries, reducing the incentives for clean energy investments. Then, Equation 15 was used to assess the moderating effect of globalization between trade freedom and clean energy. As can be seen in Column IV, the estimated coefficient of the interaction term, Ln(Trade)*Ln(Global), is positive, which suggests that globalization positively moderates trade freedom’s effect on the development of clean energy, such that the inhibitory effect of trade freedom on clean energy diminishes when a country’s level of globalization increases. This suggests that as countries become more integrated into the global economy, the effects of technology exchange, capital flows, and knowledge sharing brought about by open markets and cross-border cooperation facilitate the introduction and innovation of clean energy technologies, thus mitigating the negative implications of trade freedom on the local clean energy industry. Globalization also enhances the efficiency of resource allocation and the awareness of environmental protection, creating more favorable conditions for clean energy development. This view is supported by Hussain et al. (2021), who noted that globalization facilitates the transfer of clean energy technologies and knowledge across borders, thus mitigating the negative effects of trade freedom on clean energy sectors. Similarly, Brock et al. (2022) emphasized that global integration can drive environmental innovation by promoting the diffusion of cleaner technologies and sustainable practices.

Columns V and VI of Table 5 explore the moderating effect of government spending. Equation 12 examines the impact of government expenditure on clean energy, where Column V shows that government expenditure significantly inhibits clean energy development. TThis finding is consistent with the work of Hussain et al. (2021), who observed that insufficient government spending on clean energy technologies can impede their advancement. Chen et al. (2022) further argued that government expenditure on infrastructure and renewable energy technologies is crucial to overcoming market failures in the clean energy sector. Then, Equation 16 was used to assess government expenditure’s moderating role in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy. The results in Column VI indicate that the estimated coefficients of the interaction term, Ln(Trade)*Ln(Gov), are positive, which suggests that government expenditure positively moderates trade freedom’s influence on the development of clean energy, such that the inhibitory effect of trade freedom on clean energy is weakened when national government expenditure increases. This means that by increasing investment and support in the clean energy sector, the government can promote the development and application of clean energy technologies and mitigate the adverse effects of competitive pressure and market volatility brought about by trade freedom on the local clean energy industry. This finding is in line with Chen (2022), who highlighted the importance of government policies in fostering clean energy transitions through targeted financial support. Xie and Zhang, (2023) similarly found that robust government spending on green energy initiatives can counterbalance the negative effects of trade liberalization by creating a more favorable environment for clean energy investments.

Columns VII and VIII of Table 5 test the moderating effect of bank loans in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy. Equation 13 was first used to explore the effect of bank loans on clean energy, for which the results in Column VII show that bank loans significantly inhibit the development of clean energy. This is consistent with Günay et al., 2014, who found that limited access to bank financing for clean energy projects is a significant barrier, especially in developing economies where financial markets are less developed. Then, Equation 17 was used to assess the moderating effect of bank loans between trade freedom and clean energy. The results in Column VIII show that the estimated coefficient of the interaction term, Ln(Trade)*Ln(Loan), is negative, which indicates that bank lending negatively moderates the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy development, such that the inhibiting effect of trade freedom on clean energy increases when bank lending is higher. This suggests that although increased bank lending can provide more capital to firms, this capital may flow more to the traditional energy sector (where short-term returns are higher) than to clean energy projects (where long-term returns are more significant but risks are higher). This finding aligns with Chen and Dagestani, (2023), who found that financial constraints and limited access to bank loans are significant barriers to the expansion of clean energy projects. Gandhi et al. (2021) also found that financial institutions tend to prioritize short-term profits from fossil fuel investments, further hindering the transition to a sustainable energy economy.

5 Conclusion and policy implications

The present research evaluates the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development in 114 countries from 2006 to 2020 using a two-way fixed effects model and a two-stage least squares approach. The results show that trade freedom significantly inhibits clean energy development, and that this relationship is linear. The study also took into account control factors that may affect clean energy, namely, GDP per capita, total population of the country, level of FDI, ability of the country to control corruption, public expenditure on education, and level of development of the manufacturing industry. It was found that an increase in both GDP per capita and the state’s ability to control corruption are important factors that contribute to clean energy development. In addition, by incorporating the mediating mechanisms of national innovation and trade openness, it was revealed that trade freedom inhibits clean energy development by increasing national innovation and national trade openness. Finally, the possible moderating effects of carbon emissions, globalization, government spending, and bank lending in the process of trade freedom affecting clean energy development were explored in detail. The results show that carbon emissions and bank loans negatively moderate the relationship of trade freedom with clean energy development, while globalization and government spending positively moderate this relationship.

This study adds value to the existing body of knowledge in several areas. First, it pioneers the systematic examination of the influence of trade freedom on clean energy development, addressing a crucial gap in current research. By exploring how trade freedom interacts with national innovation, trade openness, and moderating factors such as carbon emissions, globalization, government expenditure, and bank credit, the study offers new theoretical and empirical insights into this underexplored topic. Second, the study provides practical implications for policymakers, industry professionals, and financial institutions. It emphasizes the importance of coordinated policies that foster both trade freedom and clean energy development, highlighting the need for targeted financial support, international cooperation, and regulatory frameworks to promote the transition to a clean energy economy.

These findings provide valuable insights into how governments can promote trade freedom while ensuring the stability of clean energy development. First, governments should increase investments in clean energy technology research and infrastructure construction, using fiscal budget allocations, tax incentives, subsidies, and other means to enhance support for the clean energy sector. Specific measures include setting up special funds to support clean energy technology innovation, providing low-interest loans and venture capital for clean energy projects, and guiding policies to promote the development of clean energy enterprises. This financial support can directly drive the development of clean energy projects and stimulate market vitality and corporate innovation, thereby promoting the rapid growth of the clean energy industry.

Second, countries should actively participate in international clean energy technology cooperation, introduce advanced clean energy technologies and management experience, and fully leverage the resources and advantages of the global market. By participating in international clean energy technology cooperation projects, joining global clean energy alliances, and conducting transnational technology exchanges and cooperation, the introduction and localization of clean energy technologies can be accelerated, optimizing the clean energy industry structure. This international cooperation can mitigate the inhibitory effect of trade liberalization on clean energy development and enhance national competitiveness in the global clean energy market, driving rapid advancements in clean energy technologies.

Third, financial institutions should adjust their loan policies to increase the proportion of loans for clean energy projects and reduce funding for traditional high-pollution industries. Specific measures include establishing green credit policies, providing special loans for clean energy projects, and using financial instruments such as green bonds to offer more financing channels for the clean energy sector. Additionally, financial regulatory agencies should formulate corresponding policies and regulations to encourage financial institutions to allocate more funds to green industries, promoting the shift of financial resources towards clean energy and sustainable development. By optimizing the loan structure, the issue of uneven fund distribution caused by trade liberalization can be alleviated, fostering the healthy development of the clean energy industry.

Through these measures, governments, international bodies, and financial institutions can jointly address the adverse effects of trade liberalization on clean energy development, promoting the sustainable growth of the global clean energy sector. This will not only help achieve energy structure optimization and environmental protection goals but also drive the green transformation of the economy, contributing positively to the achievement of the global SDGs.

6 Limitations and future research directions

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, there are some limitations related to the methodology and data used. First, this study relies on a panel dataset from 2006 to 2020 for 114 countries, which may not fully capture the complexities of the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy development across all countries and regions. While the dataset is comprehensive, it may not account for all the contextual and regional factors that could influence clean energy development. For instance, the dataset does not differentiate between the varying economic structures, political climates, and energy profiles across countries, which could all affect the relationship between trade freedom and clean energy.

Moreover, while this study focuses on macroeconomic and policy-related factors, there are other micro-level factors, such as local innovation ecosystems, sectoral dynamics, and the role of specific industries, that could play a significant role in this relationship but were not incorporated in the current analysis. Local innovation activities, business strategies, and the influence of non-governmental actors in the energy sector might significantly affect how trade freedom impacts clean energy development, yet they remain unexplored in this study.

Future research could address these limitations by examining the impact of trade freedom on clean energy development in more specific regions or countries with different economic structures and energy profiles. Regional studies could provide more tailored insights into the varying effects of trade freedom on clean energy development, accounting for regional disparities in infrastructure, resources, and policy frameworks. Additionally, future studies could explore micro-level factors, such as the role of local innovation, business strategies, and the influence of non-governmental actors in the energy sector. Research focusing on these factors could offer a deeper understanding of the mechanisms by which trade freedom affects clean energy development at both the macro and micro levels, allowing for more context-specific policy recommendations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Heilongjiang Provincial Office of Philosophy and Social Science under Grant number 23XZT044 and the Heilongjiang Provincial Department of Education under Grant number YQJH2023062.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1List of countries are available on request.

2Multicollinearity test results are available on request.

References

Ali, S., Khan, K. A., Gyamfi, B. A., Ofori, E. K., Tetteh, D., and Shamansurova, Z. (2024). Can clean energy and technology address environmental sustainability in G7 under the pre-set of human development? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31 (9), 13800–13814. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-32011-y

Alola, A. A., Doganalp, N., and Obekpa, H. O. (2023). The influence of renewable energy and economic freedom aspects on ecological sustainability in the G7 countries. Sustain. Dev. 31 (2), 716–727. doi:10.1002/sd.2414

Alola, A. A., and Saint Akadiri, S. (2021). Clean energy development in the United States amidst augmented socioeconomic aspects and country-specific policies. Renew. Energy 169, 221–230. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.01.022

Amoah, A., Kwablah, E., Korle, K., and Offei, D. (2020). Renewable energy consumption in Africa: the role of economic well-being and economic freedom. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 10, 32–17. doi:10.1186/s13705-020-00264-3

Blanchard, O., and Brancaccio, E. (2019). Crisis and revolution in economic theory and policy: a debate. Rev. Political Econ. 31 (2), 271–287. (Blanchard et al. (2019) revised to Blanchard and Brancaccio (2019. doi:10.1080/09538259.2019.1644730

Brock, A. L., Ewen, M., Haasis, L., Hunt, M. R., and Raapke, A. (2022). Forum introduction: gender, intimate networks, and global commerce in the early modern period. Itinerario 46 (3), 316–324. doi:10.1017/s0165115322000304

Brunnschweiler, C. N. (2010). Finance for renewable energy: an empirical analysis of developing and transition economies. Environ. Dev. Econ. 15 (3), 241–274. doi:10.1017/s1355770x1000001x

Chaabouni, S., and Saidi, K. (2017). The dynamic links between carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, health spending and GDP growth: a case study for 51 countries. Environ. Res. 158, 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.041

Chen, P. (2022). Is the digital economy driving clean energy development? New evidence from 276 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 372. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133783

Chen, P., and Dagestani, A. A. (2023). Urban planning policy and clean energy development Harmony-evidence from smart city pilot policy in China. Renew. Energy 210, 251–257. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.04.063

Chen, X., Fu, Q., and Chang, C. P. (2021). What are the shocks of climate change on clean energy investment: a diversified exploration. Energy Econ. 95, 105136. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105136

Chen, X. H., Tee, K., Elnahass, M., and Ahmed, R. (2023). Assessing the environmental impacts of renewable energy sources: a case study on air pollution and carbon emissions in China. J. Environ. Manag. 345, 118525. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118525

Chen, Y., Shao, S., Fan, M., Tian, Z., and Yang, L. (2022). One man's loss is another's gain: does clean energy development reduce CO2 emissions in China? Evidence based on the spatial Durbin model. Energy Econ. 107, 105852. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105852

Cong, S., Chin, L., and Abdul Samad, A. R. (2023). Does urban tourism development impact urban housing prices? Int. J. Hous. Mark. Analysis 18, 5–24. doi:10.1108/IJHMA-04-2023-0054

Cong, S., Chin, L., and Kumarusamy, R. (2024a). Does trade freedom affect exchange rate movement? A perspective of high-technology trade. J. Int. Trade and Econ. Dev., 1–21. doi:10.1080/09638199.2024.2320164

Cong, S., Chin, L., Senan, M. K. A. M., and Song, Y. (2024b). The impact of the digital economy on urban house prices: comprehensive explorations. Int. J. Strategic Prop. Manag. 28 (3), 163–176. doi:10.3846/ijspm.2024.21474

De Macedo, J. B., Martins, J. O., and Jalles, J. T. (2021). Globalization, Freedoms and Economic convergence: an empirical exploration of a trivariate relationship using a large panel. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 18 (3), 605–629. doi:10.1007/s10368-021-00512-7

Doblinger, C., Surana, K., Li, D., Hultman, N., and Anadón, L. D. (2022). How do global manufacturing shifts affect long-term clean energy innovation? A study of wind energy suppliers. Res. Policy 51 (7), 104558. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2022.104558

Eaton, J., and Kortum, S. (1999). International technology diffusion: theory and measurement. Int. Econ. Rev. 40 (3), 537–570. doi:10.1111/1468-2354.00028

Eberhardt, M., Facchini, G., and Rueda, V. (2023). Gender differences in reference letters: evidence from the economics job market. Econ. J. 133 (655), 2676–2708. doi:10.1093/ej/uead045

Eichengreen, B., and Mody, A. (2000). Lending booms, reserves and the sustainability of short-term debt: inferences from the pricing of syndicated bank loans. J. Dev. Econ. 63 (1), 5–44. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00098-5

Feng, C., Liu, Y. Q., and Yang, J. (2024). Do energy trade patterns affect renewable energy development? The threshold role of digital economy and economic freedom. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 203, 123371. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123371

Fenira, M. (2015). Trade openness and growth in developing countries: an analysis of the relationship after comparing trade indicators. Asian Econ. Financial Rev. 5 (3), 468–482. doi:10.18488/journal.aefr/2015.5.3/102.3.468.482

Furman, J. L., Porter, M. E., and Stern, S. (2002). The determinants of national innovative capacity. Res. policy 31 (6), 899–933. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00152-4

Gandhi, A., Yu, H., and Grabowski, D. C. (2021). High nursing staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information: study examines high turnover of nursing staff at US nursing homes. Health Aff. 40 (3), 384–391. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00957

Gennaioli, C., and Tavoni, M. (2016). Clean or dirty energy: evidence of corruption in the renewable energy sector. Public Choice 166, 261–290. doi:10.1007/s11127-016-0322-y

Günay, G., Boylu, A. A., and Bener, Ö. (2014). An examination of factors affecting economic status and finances satisfaction of families: a comparison of metropolitan and rural areas. Soc. Indic. Res. 119, 211–245. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0499-0

Hamann, R., Rennkamp, B., Kruger, W., and Musango, J. K. (2023). Corruption undermines justice in clean energy transitions. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 65 (4), 5–9. doi:10.1080/00139157.2023.2205345

Huang, F. (2023). How does trade and fiscal decentralization leads to green growth; role of renewable energy development. Renew. Energy 214, 334–341. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.05.116

Huisingh, D., Zhang, Z., Moore, J. C., Qiao, Q., and Li, Q. (2015). Recent advances in carbon emissions reduction: policies, technologies, monitoring, assessment and modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 103, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.098

Hussain, J., Zhou, K., Muhammad, F., Khan, D., Khan, A., Ali, N., et al. (2021). Renewable energy investment and governance in countries along the belt and Road Initiative: does trade openness matter? Renew. Energy 180, 1278–1289. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.09.020

Ibrahiem, D. M., and Hanafy, S. A. (2021). Do energy security and environmental quality contribute to renewable energy? The role of trade openness and energy use in North African countries. Renew. Energy 179, 667–678. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.07.019

Jaelani, A. (2017). Fiscal policy in Indonesia: analysis of state budget 2017 in Islamic economic perspective. Int. J. Econ. Financial Issues 7 (5), 14–24.

Jiang, Z., Lin, J., Liu, Y., Mo, C., and Yang, J. (2020). Double paddy rice conversion to maize–paddy rice reduces carbon footprint and enhances net carbon sink. J. Clean. Prod. 258, 120643. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120643

Kahia, M., and Ben Jebli, M. (2021). Industrial growth, clean energy generation, and pollution: evidence from top ten industrial countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 68407–68416. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15311-5

Kalu, U. D., and Joy, A. E. (2015). Does trade openness make sense? Investigation of Nigeria trade policy. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci. 4 (1), 6–21. doi:10.6007/IJAREMS/v4-i1/1469

Kilinc-Ata, N., and Alshami, M. (2023). Analysis of how environmental degradation affects clean energy transition: evidence from the UAE. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (28), 72756–72768. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-27540-x

Kojima, K. (1964). The pattern of international trade among advanced countries. Hitotsubashi J. Econ. 5, 16–36.

Krasniqi, D. (2022). The loan agreement and interest rates in kosovo. J. Intellect. Prop. Hum. Rights 1 (6), 21–29.

Lee, J. W. (2013). The contribution of foreign direct investment to clean energy use, carbon emissions and economic growth. Energy policy 55, 483–489. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.12.039

Lin, W. L., Lee, C., and Law, S. H. (2021). Asymmetric effects of corporate sustainability strategy on value creation among global automotive firms: a dynamic panel quantile regression approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 30 (2), 931–954. doi:10.1002/bse.2662

Liu, D., Guo, X., and Xiao, B. (2019). What causes growth of global greenhouse gas emissions? Evidence from 40 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 661, 750–766. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.197

Martins, J. M., Gul, A., Mata, M. N., Haider, S. A., and Ahmad, S. (2023). Do economic freedom, innovation, and technology enhance Chinese FDI? A cross-country panel data analysis. Heliyon 9 (6), e16668. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16668

Miyamoto, Y., Sato, Y., Nishizawa, S., Yashiro, H., Seiki, T., and Noda, A. T. (2020). An energy balance model for low--level clouds based on a simulation resolving mesoscale motions. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 98 (5), 987–1004.

Mora, L., Gerli, P., Ardito, L., and Petruzzelli, A. M. (2023). Smart city governance from an innovation management perspective: theoretical framing, review of current practices, and future research agenda. Technovation 123, 102717. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102717

Mottaleb, K. A., and Rahut, D. B. (2021). Clean energy choice and use by the urban households in India: implications for sustainable energy for all. Environ. Challenges 5, 100254. doi:10.1016/j.envc.2021.100254

Murshed, M. (2020). An empirical analysis of the non-linear impacts of ICT-trade openness on renewable energy transition, energy efficiency, clean cooking fuel access and environmental sustainability in South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (29), 36254–36281. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-09497-3

Nelson, R. R., and Phelps, E. S. (1966). Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 56 (1/2), 69–75.

Ng, C. F., Yii, K. J., Lau, L. S., and Go, Y. H. (2022). Unemployment rate, clean energy, and ecological footprint in OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 42863–42872. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17966-6

Nganyi, S., Jagongo, A., and Atheru, G. K. (2019). Determinants of government expenditure on public flagship projects in Kenya. Int. J. Econ. Finance 11 (6), 133. doi:10.5539/ijef.v11n6p133

Nowotny, J., Dodson, J., Fiechter, S., Gür, T. M., Kennedy, B., Macyk, W., et al. (2018). Towards global sustainability: education on environmentally clean energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 2541–2551. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.060

Paramati, S. R., Ummalla, M., and Apergis, N. (2016). The effect of foreign direct investment and stock market growth on clean energy use across a panel of emerging market economies. Energy Econ. 56, 29–41. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2016.02.008

Paraschiv, L. S., and Paraschiv, S. (2023). Contribution of renewable energy (hydro, wind, solar and biomass) to decarbonization and transformation of the electricity generation sector for sustainable development. Energy Rep. 9, 535–544. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.07.024

Pereira, M. D. M. (2021). Researching gender inequalities in academic labor during the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding common problems and asking different questions. Gend. Work and Organ. 28, 498–509. doi:10.1111/gwao.12618