- Department of English, Faculty of Languages and Translation, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

The present study explores the relationship between the concepts of foreign language (L2) learners’ resilience and their behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic engagement. It also aims to understand the role of L2 resilience in students’ overall engagement. The study employs a quantitative approach and utilizes online questionnaires by which it collected data from 123 English as a foreign language (EFL) university students. Data analysis procedures involved descriptive statistics, correlation analysis to identify the levels of L2 resilience and engagement among the EFL participants as well as the associations between these constructs; and a multiple regression analysis to unveil the explanatory power of learner resilience in language engagement. The findings revealed moderate levels of L2 resilience and overall engagement as well as significant correlations between learners’ resilience and their overall engagement and its four dimensions. The linear multiple regression analysis showed that EFL learners’ resilience has explained around a third (30%) of the total variance in their overall engagement. These findings provide insights into the importance of EFL learners’ resilience in accounting for their engagement. Such findings highlight the significance of promoting learners’ resilience for the purpose of enhancing their L2 engagement and thereby leading a successful language learning journey.

1 Introduction

The concepts of L2 resilience and student engagement hold critical roles in coping with the challenges in learning foreign languages (Kim and Kim, 2016; Dörnyei, 2019). In this regard, L2 resilience and student engagement have become of greatly growing interest in many fields such as psychology and education (Liu et al., 2022) and attracted the interest of many scholars in the domain of language learning (Mercer and Dörnyei, 2020; Ryan and Deci 2017; Hiver et al., 2021a,b). L2 resilience plays a significant role in providing learners with the ability of coping with educational difficulties, challenges, and failure (Martin and Marsh, 2006), and as a result, attain desirable outcomes such as improved educational achievement (Wang et al., 2021). Language engagement, on the other hand, is considered a fundamental factor not only in maintain positive L2 learning experiences (Hiver et al., 2021a,b) but also in demonstrating better language achievement by learners (Mercer, 2019; Wang et al., 2021).

Given their vital role in language learning, investigating the relationship between learner resilience and engagement in the course of language learning is undeniably of significant importance. While there has been limited research that examined this relationship in the field of general education (e.g., Skinner and Pitzer, 2012; Skinner et al., 2016; Ahmed et al., 2018), such research in the EFL setting is even more limited and scarce. Even with the appearance of some recent investigations that explored the relationship between L2 learners’ resilience and their engagement (Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024a,b), a closer look to such investigations has revealed a number of gaps and shortcomings since these studies have approached the relationship between these two concepts marginally in relation to other variables such as mindfulness (Liu et al., 2022) and burnout (Wang et al., 2024a,b) but did not examine the relationship between the two variables directly and independently. In addition, the predictive power of learner resilience in language engagement and its four dimensions (i.e., behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic) has, to the best of our knowledge, not been investigated so far in the L2 domain. An investigation of this kind would promote our knowledge of the relationship between L2 learners’ resilience and their engagement in the EFL context and how resilience could account for the different types of learner engagement in the language class. With this endeavor in target, the present study is informed by the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent do EFL learners demonstrate resilience and engagement in learning EFL?

RQ2: How EFL learners resilience is related to their language engagement?

RQ3: To what extent does learner resilience predict their language engagement?

2 Literature review

2.1 Resilience

Academic resilience is a concept that has garnered significant attention in psychological and educational research. It refers to the ability of individuals to persist, adapt, and thrive despite encountering adversity and challenges in their academic pursuits, and achieve positive educational outcomes (Martin and Marsh, 2006). Research suggests that resilient individuals demonstrate adaptive behaviors, psychological strengths, and effective coping mechanisms in the face of adversity, enabling them to persist and succeed academically (Radhamani and Kalaivani, 2021) and higher levels of academic achievement (Martin and Marsh, 2006).

L2 resilience, or language learning resilience, is a specific form of academic resilience that focuses on the challenges and setbacks encountered in language learning (Chu et al., 2024). It refers to the ability of second language learners to persist, adapt, and achieve positive language learning outcomes despite facing difficulties and setbacks in the language learning process (Kim et al., 2019). L2 resilience is considered a key concept within positive psychology, as it plays a crucial role in individuals’ ability to bounce back from adversity and thrive, flourish, in the face of challenges. Correspondingly, several researchers, such as Fletcher and Sarkar’s (2013), have examined language learners’ resilience as a major construct of positive psychology. In this regard, Oxford (2018) presented the EMPATHICS model, which incorporates resilience into a comprehensive framework of language learner well-being. Moreover, studies have shown that resilient individuals exhibit positive psychological characteristics such as optimism, self-efficacy, self-regulated learning, and a growth mindset (Pidgeon and Keye, 2014; Cassidy, 2015; Wang, 2021). Furthermore, resilience-oriented interventions and programs drawing from positive psychology principles have been shown to enhance learners’ well-being, motivation, and academic performance (Mercer et al., 2018).

Compared to academic resilience in the general sense, the concept of L2 resilience is a relatively new area of research within the field of second language learning. Scholars have started to recognize the importance of resilience in language learning and its impact on different aspects of learners such as their motivational behavior and L2 proficiency (Kim et al., 2019). Recent studies such as those by Chu et al. (2024), Liu and Han (2022), and Guo and Li (2022) further provide insights into the emerging field of L2 resilience and its highly important relevance in language learning contexts. The findings of such studies have established that L2 resilience enable students to maintain positive language learning outcomes in the face of challenges, setbacks, or difficulties encountered during the language learning process (Chu et al., 2024). Particularly, studies have revealed that resilient learners tend to have higher levels of self-efficacy, a belief in their ability to succeed, and greater motivation to learn and improve their language skills (Guo and Li, 2022; Zhang, 2022). Notably, research has indicated that resilience positively influences learners’ motivated behavior, language learning engagement, and L2 proficiency (Kim and Kim, 2021). In addition, resilient learners are more likely to set meaningful goals, employ effective learning strategies, and persevere through obstacles, leading to improved language skills and achievement (Liu and Han, 2022). A recent study concluded that learners with higher levels of L2 resilience are more likely to persist in the face of difficulties, seek help when needed, and adopt effective learning strategies (Zarrinabadi et al., 2022).

2.2 Student engagement

Student engagement is a crucial construct in educational settings, encompassing students’ active involvement and investment in their learning process. It has been widely studied within the field of language education, with researchers exploring its various dimensions and implications for language learning outcomes (Hiver et al., 2021a,b; Mercer, 2019). For instance, Skinner et al. (2009) emphasize that engagement is a dynamic and multifaceted concept that goes beyond mere participation in classroom activities. Moreover, Skinner and Pitzer (2012) and Svalberg (2009) defined learners’ engagement as the dynamic and complex nature of immersion in the learning process. Furthermore, Hiver et al. (2021a,b) defined engagement as the level of learners’ active involvement and commitment in the learning experience and that they must have clear learning goals and purposes.

The intersection between engagement and positive psychology has received considerable attention in recent years. Positive psychology emphasizes the promotion of well-being and optimal functioning, and engagement is seen as a key component of positive psychological experiences (Hiver et al., 2021a,b). Research has shown that engagement can serve as a motivational resource, influencing academic coping, persistence, and learning (Skinner et al., 2016). Additionally, Wang et al. (2024a,b) found that teacher autonomy support positively influenced students’ academic English-speaking performance through the mediation of basic psychological needs and classroom engagement. Drawing from positive psychology, Seligman (2018) introduces the PERMA model, which encompasses five building blocks of well-being that are, namely, positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishments, in various domains, including language learning (Oxford, 2018). Additionally, Alrabai and Dewaele (2023) proposed the transformation of the EMPATHICS model into the E4MC model of language learner well-being, incorporating the construct of engagement to promote holistic well-being.

The concept of student engagement encompasses four dimensions, including behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic (Skinner et al., 2009; Reeve, 2013; Senko and Miles, 2008; Elliot et al., 1999). The behavioral dimension refers to students’ active participation and involvement in learning activities that contribute to engagement and academic success (Skinner et al., 2009). The emotional dimension relates to students’ affective responses, such as interest, enjoyment, and enthusiasm toward learning that influence their academic outcomes (Elliot et al., 1999). The cognitive dimension involves students’ use of higher order thinking skills and deep processing of information to actively and cognitively construct knowledge (Senko and Miles, 2008). Finally, the agentic dimension highlights students’ autonomy, initiative, and self-regulation in the learning process, as well as their ability to create supportive learning environments for themselves by taking self-determined approach to their learning (Reeve, 2013).

These four dimensions of engagement lead us to the application of the complex dynamic systems theory (CDST; Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008; Larsen-Freeman, 2017) to the current study. To illustrate, the incorporation of complex dynamic systems theory (CDST) into the concept of engagement has just gained traction in language learning research (Hiver et al., 2023). CDST provides a framework for understanding the dynamic and nonlinear nature of engagement, recognizing that it emerges from the interactions of various aspects within a complex system. Specifically, considering that the present study investigated the engagement in the L2 classroom, which is a place known for its complex social system, it was rationally justifiable to include this theory in this study. This perspective acknowledges that engagement is influenced by multiple interconnected variables, including these four dimensions of engagement (i.e., behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic), which together shape the learning process.

Engagement plays an essential role in language learning outcomes and experiences as evidenced by past research. It has been linked to increased motivation, enhanced language proficiency, and greater learner well-being (Hiver et al., 2021a; Zhou et al., 2023a,b). Svalberg (2009) highlights how engagement involves learners’ active and meaningful engagement with language, fostering their language awareness and development. Furthermore, Al-Hoorie et al. (2022) highlighted the significance of engagement in promoting learner autonomy, competence, and relatedness (basic psychological needs).

Engaged learners exhibit certain attributes that contribute to their active involvement in the learning process. These attributes include intrinsic motivation, curiosity, self-regulation, resilience, and a sense of purpose (Mercer and Dörnyei, 2020; Skinner et al., 2009). In the same manner as resilient learners, engaged learners are more likely to persist in challenging tasks, seek out opportunities for learning, and take ownership of their educational experiences. Moreover, Mercer (2019) and Dincer et al. (2019) revealed positive relationships between EFL learners’ engagement and their classroom motivation, enjoyment, and successful learning outcomes. In addition, language engagement, according to Hiver et al. (2021a,b), influences language proficiency and learner well-being. Finally, Mercer and Dörnyei (2020) discussed the importance of creating meaningful and motivating learning experiences in promoting EFL learners’ engagement. All in all, these studies highlight the essential role of engagement in language learning, emphasizing its positive influence on motivation, autonomy, competence, and overall language learning success.

2.3 The relationship between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement

The relationship between academic resilience and student engagement is an important area of research. However, very few studies have specifically discussed this relationship in the educational field in general, and even fewer investigated such an association in the field of language learning. As with regard to the EFL context of this study, and to the best of my knowledge, no prior studies have investigated the relationship between EFL learner’s resilience and their engagement in the L2 classroom. In this literature review, we will explore the limited existing research on this topic, drawing upon relevant studies.

Skinner and Pitzer (2012) investigated the developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. While their study did not specifically focus on EFL learners, it provides insights into the factors that influence engagement and resilience across different educational contexts.

Similarly, in another study by Skinner et al. (2016), the authors explored whether student engagement can serve as a motivational resource for academic resilience, coping, persistence, and learning. Nevertheless, and just as their previous study, this study is also not specific to EFL learners. Moreover, Ahmed et al. (2018) examined the links between teachers’ support, academic efficacy, academic resilience, and student engagement in Bahrain. Their study highlighted the positive association between academic resilience and student engagement, suggesting that resilient language learners are more likely to actively participate and be engaged in the language learning process. Although not focused on EFL learners, their findings suggest that teacher support can contribute to students’ academic resilience, efficacy, and engagement.

One study that examined this relationship in language learning contexts is conducted by Liu et al. (2022) who investigated the role of academic resilience and mindfulness in the engagement of Chinese language learners. Their findings indicated that higher levels of academic resilience were associated with greater engagement, emphasizing the importance of resilience in fostering language learner engagement.

In addition, a recent study by Wang et al. (2024a,b) investigated resilience, engagement, and burnout among Chinese high school EFL learners. This study provides insights into the relationship between resilience, engagement, and burnout, which has implications for EFL learners’ well-being and learning outcomes. Understanding the emotional aspect of EFL learners can help identify strategies to foster resilience and engagement of EFL learners in the target language.

To the best of my knowledge, these two studies are the only studies to, scarcely, discuss the relationship between language resilience and engagement. Therefore, the present study aimed to be the first to examine the direct relationship between EFL learners’ resilience and engagement in the field of language learning in general, and, more specifically, in the EFL context of this study. Moreover, this study fully acknowledged the importance of language resilience and engagement in overcoming educational challenges, maintaining motivation, and actively participating in the language learning process, which ultimately enhances their overall learning experience. As a result, the current paper aimed to promote our knowledge of these concepts and provide implications for EFL teachers on how to advance and reinforce their student’s language resilience and L2 classroom engagement.

Therefore, the present study bridges the gap by investigating the considerable relationship between learners’ resilience and their classroom engagement in the context of language learning.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants and procedures

A total of 123 undergraduate Saudi female university English-majoring students took part in this study. The participants were selected following a convenience sampling method since it was the only method available for recruiting participants in this study. The participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 25 years (mean = 21.56, SD = 3.02). Their EFL learning experience was between 9 and 11 years, and because they were recruited from different schooling levels, their EFL proficiency level ranged from beginner to advanced. Those learners were studying a variety of courses across the different levels at the department of English and these courses were taught almost completely in English.

Prior to the actual recruitment of participants, one of the researchers paid an advance-notice visit to potential participants in which they were thoroughly informed of the objective of the study, its methodology, anticipated outcomes, and their anticipated role in the study. Proper care was taken to observe ethical issues related to obtaining the participants’ informed consent and treating the collected data as anonymous and confidential.

On the day of recruitment, respondents were provided with ample instructions on how to fill in the questionnaire before they were provided with the link to the online survey. The students started the survey by responding to some demographic items asking about their gender, age range, schooling level, as well as their proficiency level. In the absence of the class teacher, one of the researchers was available on the day of data collection to help with any inquiries that students might had on how to fill in the survey. Participants responded to the online questionnaire using their mobile phones, laptops, and other electronic devices. They were provided with enough time to respond to the survey and it took them around 10–15 min to fill in the whole survey.

It is noteworthy that the participants were allowed to willingly withdraw from the study at any stage. The exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue the study, refusal to provide informed consent, and incomplete questionnaires. A total of 126 questionnaires were administered, 123 of which were returned (response rate = 97.62%).

3.2 Measures

This study utilized a 34-item questionnaire survey to gather the data (see online material). In this study, a scale of 15 items that was originally adapted from Shin et al. (2009) and then validated by Kim and Kim (2016) was specifically chosen to measure language learner resilience.

To assess learners’ engagement in L2 class, a 19 items-scale that constitute the four dimensions of engagement was used. Two scales were adopted from Skinner et al. (2009) to measure behavioral engagement (5 items) and emotional engagement (5 items). Another 5 items scale, from the Agentic Engagement Scale (Reeve, 2013), was used to measure agentic engagement and 4 items were adapted from Senko and Miles (2008) to measure the fourth dimension of engagement, the cognitive engagement.

Responses of participants to items in the scales of both resilience and engagement were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To enhance the readability of the questionnaire items to the participants, they were translated into their first language, Arabic, by the researcher and these translated items, along with the entire online survey, were checked for accuracy and clarity by a bilingual subject-matter expert. The full version of the survey is available in Appendix I in the online material.

3.3 Statistical analysis

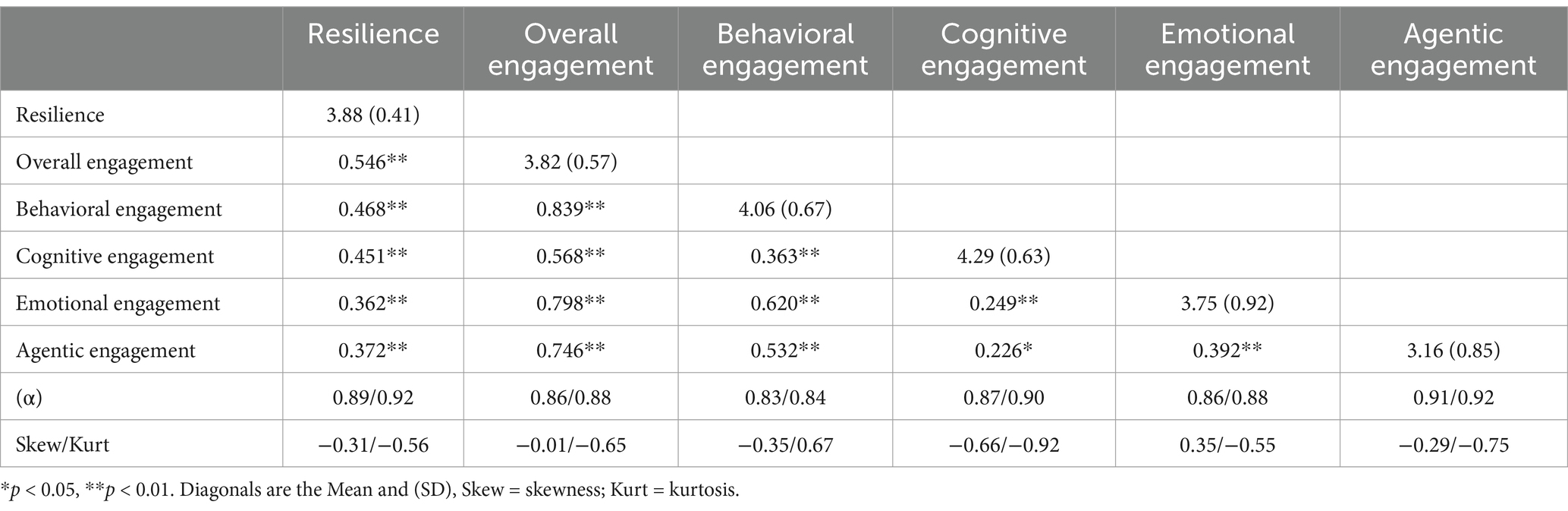

A series of data preparation, preliminary analyses, and main analyses were conducted using Jamovi 2.5.4 software. Data was first screened for missing data and outliers revealing no such cases in the data. Survey items were then coded, with negative items reverse coded, and some computations were then performed to prepare the data for preliminary and main analyses. Preliminary analyses represented in reliability Cronbach Alpha analysis and Skewness and Kurtosis normality tests were then run. The reliability test revealed reliable scales (α = 0.78 for resilience), and (α = 0.88 for engagement) as well as its subscales (α = 0.80 for behavioral engagement, α = 0.71 for cognitive engagement, α = 0.85 for emotional engagement, and α = 0.80 for agentic engagement). Skewness and kurtosis values following the +1/−1 cut-off values (Hair et al., 2022) were used to assess normality. All of the values were within the range of −1 to +1, indicating a normal distribution of the data among all scales and subscales in the present study (see Table 1 and the Q-Q plots in Appendix II).

Finally, descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations), a Pearson correlation analysis and a linear multiple regression analysis were carried out on the collected data to reveal the findings of the study.

The α and CR coefficients of these scale are reported in Table 1, and they show that the internal reliability values of all the constructs appear to be (>0.70) and thus deemed satisfactorily reliable (Dörnyei, 2007).

4 Results

The first part of RQ1 seeks to identify the levels of L2 resilience among participants EFL learners, in this regard, the results of the present study revealed that EFL learners demonstrated moderate levels of L2 resilience (M = 3.88). Item # 8 in the survey ‘I would look forward to showing that I can improve my grades’ stands out with the highest mean (M = 4.54) indicating high levels of resilience among learners with respect to improving their grades. Participants demonstrated high levels of resilience in terms of controlling the negative feelings and the ability to deal with difficulties. This was represented by items like ‘I would do my best to stop thinking negative thoughts,’ ‘I am sure that everything will be fine even in difficult situations,’ ‘When I have a problem, I try to solve it after reflecting on the cause of the problem,’ ‘I first contemplate diverse possible solutions to a problem in order to solve it.’ Finally, learners demonstrated moderate levels on most of the items in the survey and they did not report low levels on any of resilience indicators represented by these items.

As for the second part of RQ1 regarding the levels of L2 engagement of participant learners, the overall mean score of the four dimensions of engagement together was (M = 3.82), suggesting moderate levels of overall L2 engagement among the participants. While students demonstrated high levels of cognitive (M = 4.29) as well as behavioral engagement (M = 4.06), they exhibited moderate levels of emotional (M = 3.75) and agentic engagement (M = 3.16), suggesting lower levels of these later two types of engagement among students compared to the two earlier types.

The correlation analysis conducted to answer RQ2 regarding the presence, direction, and strength of the associations between foreign language learners’ resilience and their overall engagement, as well as its four dimensions in the L2 classroom revealed significant positive links between these constructs. The results of the correlational analysis revealed significant, positive, and strong correlations between resilience and the overall engagement (r = 0.546, p < 0.001) illustrating that the higher resilient students tend to be, the more engaged they become in the L2 classroom. Interestingly, similar strong correlations between resilience and all four dimensions of engagement were also detected, with learners behavioral engagement showing the highest degree of significantly positive correlation with their resilience (r = 0.468, p < 0.001), followed by students’ cognitive engagement (r = 0.451, p < 0.001), and to a lower degree their agentic (r = 0.372, p < 0.001) and emotional engagement (r = 0.362, p < 0.001), respectively.

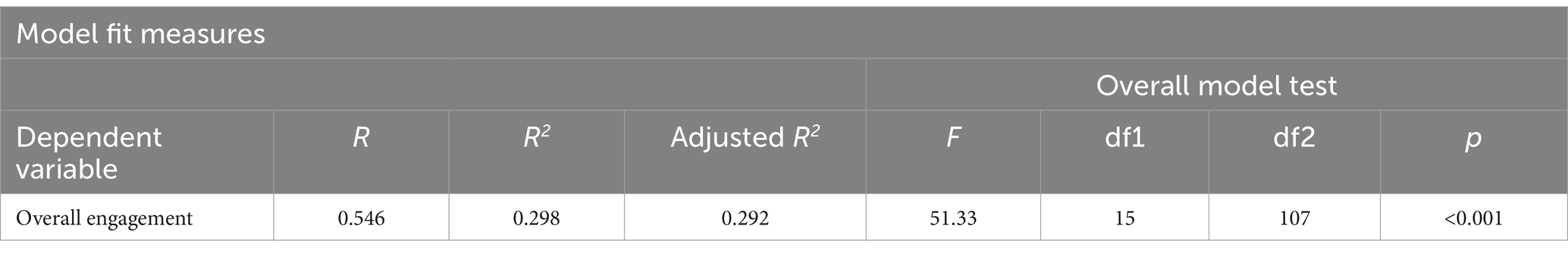

The linear multiple regression analysis that was carried out to identify the predictive role of learner resilience in language engagement revealed that much of the variance in the dependent variable (i.e., the overall engagement) and to answer RQ3 is explained by the precision model in the present study. The R value (0.546) in Table 2 indicates a significant correlation (p < 0.001) between the predictor and the outcome variable. In addition, the model has shown that EFL learners’ resilience has explained around 30% (R2 = 0.298) of the total variance in the outcome variable (their overall engagement). This could be interpreted as a moderate explanatory predictive power following the interpretations of Hair and Alamer (2022) of interpretation of the R2 value in prediction models in L2 research: R2 values between 0 to 0.10 (weak), 0.11 to 0.30 (modest), 0.30 to 50 (moderate), and > 0.50 (strong) explanatory power.

5 Discussion

This study set out with the aim of investigating the relationship between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement in the L2 classroom as well as providing an empirical account of the levels of L2 resilience and the levels of students’ engagement (i.e., behavioral engagement, emotional engagement, cognitive engagement, agentic engagement, and the overall learner’s engagement) among EFL learners who took part in this study.

The results of the current study indicated that participating EFL learners generally demonstrated moderate levels of L2 resilience, significantly supporting the findings of past research (e.g., Cassidy, 2015; Öz and Şahinkarakaş, 2023), which indicated that their students (British and Turkish) also demonstrated moderate levels of L2 resilience. However, Liu and Han (2022) found that Chinese high school students exhibited slightly higher levels of English academic resilience than those of the present study’s participants. The reasons for such difference may be attributed to factors such as cultural background, learning environment, and individual characteristics. Similarly, participating EFL learners demonstrated higher levels of L2 resilience in relation to their motivation, persistence, and self-regulation. To illustrate, EFL learners demonstrated very high levels of L2 resilience (M = 4.54) regarding their motivation and persistence to improve their language learning, which is consistent with past studies which have revealed that resilient learners tend to have a greater motivation to learn and improve their language skills, and a belief in their ability to succeed (Guo and Li, 2022; Zhang, 2022). In addition to the conclusions reached by Cassidy (2015) and Kim and Kim (2016) who stated that resilient EFL learners exhibit higher degrees of motivation and persistence in language learning context. Moreover, the present study showed that EFL learners demonstrated high levels of L2 resilience concerning their ability to self-regulate their negative emotions in the language learning context. This goes in line with Alrabai and Alamer’s (2022) study which suggested that regulating learners’ emotions has a significant role in their L2 resilience. In light of the theoretical assumptions grounded in the lens of positive psychology (PP), all of these findings are consistent with the theoretical conclusions stated by MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012), that regulating negative emotions, in EFL learning contexts (Oxford, 2016), helps transforming them into positive emotions (e.g., happiness, which is a pillar component of the resilience scale in the current study) and, as a result, improving L2 resilience (Dewaele, 2017).

EFL learners in the present study have demonstrated moderate levels of engagement in the L2 classroom which is consistent with results obtained by Skinner et al. (2016) who found that EFL learners in their study demonstrated moderate levels of engagement. This examination of the overall engagement brings only half the picture into focus; to complete the other half, the current study provided a surge of interest in the integration of four dimensions of engagement (i.e., behavioral, emotional, agentic, and cognitive). This perspective of looking at students’ engagement is backed up by complex dynamic systems theory (CDST; Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008; Larsen-Freeman, 2017) which is, according to Hiver et al. (2021a,b), a framework (for investigating student engagement) that may be neglected and overlooked when exploring the concept of student engagement. CDST is central for explaining the dynamically different results of the levels of the four dimensions of engagement (i.e., behavioral, emotional, agentic, and cognitive) observed in the current study. Learners in this study demonstrated relatively high levels of behavioral engagement in the L2 classroom, which goes in line with the findings of Zhou et al. (2023a,b), which showed that the students in their study demonstrated high levels of behavioral engagement across three different waves. In the same manner, the results of the levels of cognitive engagement among EFL learners in this study are consistent with those obtained in previous research (Zhou et al., 2023a,b) as both studies revealed high levels of cognitive engagement among the participants. Specifically, the current paper found that EFL learners demonstrated high levels of cognitive engagement in regard to their ability to infer ideas to understand them better, which further corroborates Svalberg’s (2009) analysis that such inferences require higher degree of cognitive engagement.

Interestingly, this study indicated that EFL learners demonstrated moderate levels of emotional and agentic engagement in EFL learning contexts. These findings run counter to those observed by Zhou et al. (2023a,b), stating that participants in their study demonstrated very high levels of emotional and agentic engagement across three different waves in a 17-week semester. A plausible explanation for such findings might be that the data of current paper was collected at the very beginning of the semester, where participants had not yet gained a sense of familiarity with the classroom settings and their teacher, which is, according to Oga-Baldwin and Fryer (2021) and Zhou et al. (2023a,b) an essential part of students’ engagement.

Notably, EFL learners, in the present study, demonstrated low levels of agentic engagement in regard to communicating their preferences or asking questions, which had, in fact, the lowest mean score among all variables in current study. Nevertheless, Reeve and Tseng (2011) revealed that such aspects of the agentic engagement construct (i.e., expressing preferences and asking questions) do not necessarily affect learners’ advancement or their learning improvement. Therefore, it seems that this finding does not indicate a serious engagement-related problem among EFL learners who took part in the present investigation.

Overall, it can be argued that these moderate to high levels of engagement among EFL learners who participated in this investigation, according to Wang and Mercer (2020), indicate students who are not only engaged in the L2 classroom, but also more resourceful beyond classrooms.

The key objective of the present study was to identify the relationship between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement, including its four dimensions, in the L2 classroom and to reveal the predictive power of resilience as a predictor variable in L2 learner engagement as a learning outcome. The results of the current study lend support to previous findings that proved the existence of a meaningful association between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement in language learning contexts (Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024a,b). Specifically, the current study found a significant association between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement in the L2 classroom. This finding is largely in accordance with findings reported by Liu et al. (2022) which indicated that higher levels of academic resilience were associated with greater student engagement. Another result that this finding further supports was provided by Wang et al. (2024a,b) which highlighted the positive relationship between academic resilience and student engagement.

The results of the linear multiple regression analysis in the present study indicated that EFL learners’ resilience has a strong explanatory power for their overall engagement, that is, EFL learners’ resilience positively predicts their overall engagement in the L2 classroom. This supports the findings of Liu et al. (2022) who established that resilient learners are more presumably to actively engage in the language learning experience, emphasizing the predictive role of L2 resilience in and its importance for language learners’ engagement.

Having verified this positive and significant association between L2 resilience and the overall engagement, it is noteworthy mentioning the associations between L2 resilience and other dimensions of students’ engagement. In light of positive psychology (PP) perspectives, the present study revealed that EFL learners in the current study demonstrated high levels of emotional engagement in regard to their enjoyment in the L2 classroom (as one component of the emotional dimension of engagement). This result further supports past research (Byrd and Abrams, 2022) that revealed, based on positive psychology model proposed by Oxford (2016), learners who demonstrated enjoyment in L2 classrooms, have also developed, maintained, and built their L2 resilience.

Moreover, the significant correlations found in the current study between behavioral engagement and L2 resilience can be closely linked to theoretical conclusions made by past research emphasizing that behavioral engagement was associated with the improvement in resilience as well (Skinner et al., 2016).

Additionally, the highly significant correlation found between L2 resilience and cognitive engagement, in the current study, further supported the conclusion made by Radhamani and Kalaivani (2021), in their literature review of academic resilience, that student’s cognitive beliefs can increasingly predict their resilience.

Finally, as for the association between agentic engagement and L2 resilience, Reeve (2013) found that a genetically engaged students tend to create greater motivational support for themselves and attain greater learning achievement. This is centrally important to the present study because it further supports the findings that EFL learners did demonstrate higher levels of L2 resilience in relation to their motivation and persistence to improve their language learning outcomes.

Past research has well-acknowledged that both L2 resilience and student engagement can be promoted, enhanced, and reinforced by the supporting role of the teacher (Oga-Baldwin and Hirosawa, 2022; Ryan and Deci, 2017; Reivich and Shatte, 2002). To this end, acknowledging this positive, significant, and meaningful relationship between EFL learners’ resilience and their engagement in language learning contexts is an added value for both educators and students, as it may be argued that they will be able to improve and reinforce the overall engagement through improving its positive predictor, that is, L2 resilience.

6 Conclusion

The key goal of this research was to explore the role of foreign language learners’ resilience in their engagement in the L2 classroom. The findings indicated that learners who exhibited higher levels of resilience were more actively engaged in the L2 classroom, encompassing behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic dimensions of engagement. Moreover, the linear multiple regression analysis revealed that EFL learners’ resilience can positively predict their overall engagement in the L2 classroom, providing further evidence of the pivotal relationship between L2 resilience and student engagement.

This study holds important implications for the field of study. Theoretically, the study contributes to existing knowledge of the two constructs as well as the relationship between L2 learners’ resilience and their engagement in L2 classrooms by supporting past research findings that L2 learners’ resilience is a positive predictor of their engagement in L2 classrooms. Pedagogically, and considering that several researchers believe that resilience and engagement can be developed and reinforced among L2 learners (Ryan and Deci, 2017; Reivich and Shatte, 2002), the study attempts to be of assistance to encourage L2 teachers to reinforce these constructs among their students. In this regard, focusing on reinforcing resilience among L2 learners could, consequently, enhance their L2 classroom engagement and eventually their overall language learning outcomes. Along similar lines, it emphasizes the need for educators and practitioners to consider resilience-building strategies and promote student engagement in language classrooms. A practical way to build students’ resources for resilience is to provide students with a variety of teacher support in the classroom such as emotional support, academic support and instrumental support since teacher support as been found to facilitate higher levels of learner engagement and consequently a stronger sense of academic resilience (Alrabai and Algazzaz, 2024; Liu and Li, 2023). Another way in this respect is to promote students’ psychological need of relatedness and connectedness with the other parties in the classroom like their peers and teachers. According to Hiver and Sánchez Solarte (2021), fostering warm and respectful connections between language students and their teachers and peers in the classroom is an efficient way in building their resilience in the language classroom. Finally, this study stands out from previous research as it is the first to investigate the direct relationship between L2 learners’ resilience and their engagement in the L2 classroom independently, that is, without the influence of other variables in the EFL context of this study.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the study was limited in that it captured the association between L2 learner resilience and engagement cross-sectionally at a single point in time using a self-reported questionnaire. Future research investigations should examine this relationship longitudinally at different time points using a triangulation of measurements like interviews besides questionnaire surveys. In addition, the present study, due to practical challenges, did not utilize an experimental approach, which we believe is the gold standard for investigating such a relationship between the two concepts of resilience and engagement. Therefore, the findings were interpreted with caution in terms of establishing a causal relationship between L2 learners’ resilience and their engagement in the L2 classroom, as the employed correlational approach can only demonstrate the relationship and not the causality. An additional limitation is that the participants, in this study, were limited to students at the university level, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other contexts or learners’ populations (e.g., male high school students). Future studies should therefore explore this area of research in larger and more diverse populations employing more empirical research designs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the King Khalid University Abha Saudi Arabia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1502420/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmed, U., Umrani, W. A., Qureshi, M. A., and Samad, A. (2018). Examining the links between teachers support, academic efficacy, academic resilience, and student engagement in Bahrain. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 5, 39–46. doi: 10.21833/ijaas.2018.09.008

Al-Hoorie, A. H., Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., Hiver, P., and Vitta, J. P. (2022). Self-determination mini-theories in second language learning: a systematic review of three decades of research. Lang. Teach. Res. doi: 10.1177/13621688221102686

Alrabai, F., and Alamer, A. (2022). The role of learner character strengths and classroom emotions in L2 resilience. Front. Psychol. 13:956216. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.956216

Alrabai, F., and Algazzaz, W. (2024). The influence of teacher emotional support on language learners’ basic psychological needs, emotions, and emotional engagement: treatment-based evidence. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 14, 453–482. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.39329

Alrabai, F., and Dewaele, J.-M. (2023). Transforming the EMPATHICS model into a workable E4MC model of language learner well-being. J. Psychol. Lang. Learn. 5, 1–14. doi: 10.52598/jpll/5/1/5

Byrd, D. R., and Abrams, Z. I. (2022). Applying positive psychology to the L2 classroom: acknowledging and fostering emotions in L2 writing. Front. Psychol. 13:925130. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925130

Cassidy, S. (2015). Resilience building in students: the role of academic self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 6:1781. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781

Chu, W., Yan, Y., Wang, H., and Liu, H. (2024). Visiting the studies of resilience in language learning: from concepts to themes. Acta Psychol. 244:104208. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104208

Dewaele, J. M. (2017). Psychological dimensions and foreign language anxiety. In: The Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition. eds. S. Loewen and M. Sato Routledge Handbooks in Applied Linguistics. New York, U.S.: Routledge, pp. 433–450.

Dincer, A., Yeşilyurt, S., Noels, K. A., and Vargas Lascano, D. I. (2019). Self-determination and classroom engagement of EFL learners: a mixed-methods study of the self-system model of motivational development. SAGE Open 9:2158244019853913. doi: 10.1177/2158244019853913

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2019). Towards a better understanding of the L2 learning experience, the Cinderella of the L2 motivational self-system. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 19–30. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.2

Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A., and Gable, S. (1999). Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: a mediational analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 549–563. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.549

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 18, 12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Guo, N., and Li, R. (2022). Measuring Chinese English-as-a-foreign-language learners’ resilience: development and validation of the foreign language learning resilience scale. Front. Psychol. 13:1046340. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046340

Hair, J., and Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 1:e100027:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.rmal.2022.100027

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., and Chechile, R. A. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A., and Mercer, S. (2021a). Student engagement in the language classroom. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., and Wu, J. (2021b). Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research. Lang. Teach. Res. 28, 201–230. doi: 10.1177/13621688211001289

Hiver, P., Larsen-Freeman, D., Al-Hoorie, A. H., and Lowie, W. (2023). Complex dynamic systems and language education: a sampling of current research–editorial. Int. J. Complexity Educ. 4:1–8.

Hiver, P., and Sánchez Solarte, A. (2021). “Resilience” in The routledge handbook of the psychology of language learning and teaching. eds. T. Gregersen and S. Mercer (New York: Routledge).

Kim, T., and Kim, Y. (2016). The impact of resilience on L2 learners’ motivated behaviour and proficiency in L2 learning. Educ. Stud. 43, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2016.1237866

Kim, T. Y., and Kim, Y. (2021). Structural relationship between L2 learning motivation and resilience and their impact on motivated behavior and L2 proficiency. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 50, 417–436. doi: 10.1007/s10936-020-09721-8

Kim, T. Y., Kim, Y., and Kim, J. Y. (2019). Role of resilience in (de) motivation and second language proficiency: cases of Korean elementary school students. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 48, 371–389. doi: 10.1007/s10936-018-9609-0

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2017). “Complexity theory: the lessons continue” in Complexity theory and language development: In celebration of Diane Larsen Freeman. eds. L. Ortega and Z. Han (Michigan, USA: John Benjamins), 12–50.

Larsen-Freeman, D., and Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Liu, W., Gao, Y., Gan, L., and Wu, J. (2022). The role of Chinese language learners’ academic resilience and mindfulness in their engagement. Front. Psychol. 13:916306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.916306

Liu, H., and Han, X. (2022). Exploring senior high school students’ English academic resilience in the Chinese context. Chinese J. Appl. Linguist. 45, 49–68. doi: 10.1515/cjal-2022-0105

Liu, H., and Li, X. (2023). Unravelling students’ perceived EFL teacher support. System 115:103048. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2023.103048

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stu. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2, 193–213. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

Martin, A. J., and Marsh, H. W. (2006). Academic resilience and its psychological and educational correlates: a construct validity approach. Psychol. Sch. 43, 267–281. doi: 10.1002/pits.20149

Mercer, S. (2019). “Language learner engagement: setting the scene” in Second handbook of English language teaching. ed. X. Gao (Cham: Springer), 643–660.

Mercer, S., and Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mercer, S., MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Talbot, K. (2018). Positive language education: Combining positive education and language education. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals). Available at: https://doaj.org/article/89479d39830141fa8d50452f7deddaff

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., and Fryer, L. K. (2021). “12 Engagement Growth in Language Learning Classrooms: A Latent Growth Analysis of Engagement in Japanese Elementary Schools,” in Student Engagement in the Language Classroom. eds. H. Cooper and L. V. Hedges. (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 224–240.

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., and Hirosawa, E. (2022). “Self-determined motivation and engagement in language: a dialogic process” in Researching language learning motivation: a concise guide. eds. A. H. Al-Hoorie and F. Szabó (London, UK: Bloomsbury), 71–80.

Oxford, R. L. (2016). “Toward a psychology of well-being for language learners: the ‘EMPATHICS’ vision” in Positive psychology in SLA. eds. P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, and S. Mercer (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters), 10–87.

Oxford, R. L. (2018). “EMPATHICS: a complex dynamic systems (CDS) vision of language learner well-being” in The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching. eds. J. I. Liontas and M. DelliCarpini.

Öz, G., and Şahinkarakaş, Ş. (2023). The relationship between Turkish EFL learners’ academic resilience and English language achievement. Reading Matrix Int Online J. 23, 80–91.

Pidgeon, A. M., and Keye, M. (2014). Relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and psychological well-being in university students. Int. J. Liberal Arts Soc. Sci 2, 27–32.

Radhamani, K., and Kalaivani, D. (2021). Academic resilience among students: a review of literature. Int. J. Res. Rev. 8, 360–369. doi: 10.52403/ijrr.20210646

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: the concept of agentic engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 579–595. doi: 10.1037/a0032690

Reeve, J., and Tseng, M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of student engagement during learning activities. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 13, 333–335. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

Senko, C., and Miles, K. M. (2008). Pursuing their own learning agenda: how mastery-oriented students jeopardize their class performance. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 33, 561–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2007.12.001

Shin, W. Y., Kim, M. G., and Kim, J. H. (2009). Developing measures of resilience for Korean adolescents and testing cross, convergent, and discriminant validity. Stud. Korean Youth 20, 105–131.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., and Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 69, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

Skinner, E. A., and Pitzer, J. R. (2012). “Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience” in Handbook of research on student engagement. eds. S. Christenson, A. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston, MA: Springer US), 21–44.

Skinner, E. A., Pitzer, J. R., and Steele, J. S. (2016). Can student engagement serve as a motivational resource for academic coping, persistence, and learning during late elementary and early middle school? Dev. Psychol. 52, 2099–2117. doi: 10.1037/dev0000232

Svalberg, A. M. L. (2009). Engagement with language: interrogating a construct. Lang. Aware. 18, 242–258. doi: 10.1080/09658410903197264

Wang, L. (2021). The role of students’ self-regulated learning, grit, and resilience in second language learning. Front. Psychol. 12:800488. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800488

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12:731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wang, Y., Luo, W., Liao, X., and Zhao, P. (2024a). Exploring the effect of teacher autonomy support on Chinese EFL undergraduates’ academic English speaking performance through the mediation of basic psychological needs and classroom engagement. Front. Psychol. 15:1323713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1323713

Wang, I. K. H., and Mercer, S. (2020). 14 conceptualizing willingness to engage in L2 learning beyond the classroom. Stud. Engag. Lang. Classroom 11:260–279. doi: 10.21832/9781788923613-017

Wang, Y., Xin, Y., and Chen, L. (2024b). Navigating the emotional landscape: insights into resilience, engagement, and burnout among Chinese high school English as a foreign language learners. Learn. Motiv. 86:101978. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2024.101978

Zarrinabadi, N., Lou, N. M., and Ahmadi, A. (2022). Resilience in language classrooms: exploring individual antecedents and consequences. System 109:102892. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102892

Zhang, B. (2022). The relationship between Chinese EFL learners’ resilience and academic motivation. Front. Psychol. 13:871554. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.871554

Zhou, S. A., Hiver, P., and Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2023a). Dynamic engagement: a longitudinal dual-process, reciprocal-effects model of teacher motivational practice and L2 student engagement. Lang. Teach. Res. 13621688231158789. doi: 10.1177/13621688231158789

Keywords: EFL, resilience, engagement, positive psychology, language learning

Citation: Alahmari A and Alrabai F (2024) The predictive role of L2 learners’ resilience in language classroom engagement. Front. Educ. 9:1502420. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1502420

Edited by:

Darren Moore, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sílvio Manuel da Rocha Brito, Polytechnic Institute of Tomar (IPT), PortugalMaria M. da Silva Nascimento, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Alahmari and Alrabai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fakieh Alrabai, ZmFscmFiZWlAa2t1LmVkdS5zYQ==

Arwa Alahmari

Arwa Alahmari Fakieh Alrabai

Fakieh Alrabai