- Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Forensic and Fish Health Laboratory, Laramie, WY, United States

This study compares the decision-making processes and workflows of complex and simple wildlife forensic cases at the Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Forensic Laboratory. To highlight the varied processes involved in analyzing cases at the laboratory, a complex case, consisting of eighteen different animals and a simpler case consisting of only two animals will be discussed. Both cases highlight several decision making points throughout to determine the number of samples to collect, if the samples contain biological material, the extraction methods to be used, and how to proceed with downstream analyses. These decision points are notably more numerous in the complex case. Both cases cover the process of subsampling, extraction methods, test methods, and results. At the time of the complex case, sanger sequencing, used for species identification of the deer species did not allow for the differentiation between the closely related white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and a protein analysis was used to differentiate them. A new procedure, population assignment in conjunction with sequencing, validated after the complex case and prior to the simple case made the differentiation easier and more efficient. This change in species identification emphasizes the need for continual validation of new procedures. Results of wildlife forensic cases are not only dependent on the analyses performed, but also on the decisions made by the analyst throughout the process.

1 Introduction

The Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Forensic and Fish Health Laboratory, consisting of three sections: fish health, tooth aging, and wildlife forensics, is a state funded laboratory in the United States and is accredited by ANSI National Accreditation Board (ANAB) to ISO/IEC 17025:2017 standards. The forensic portion of the laboratory was established in 1988 and was primarily focused on species identification, sex identification, and matching using RFLPs. The laboratory has had a long standing relationship with Colorado Parks and Wildlife Law Enforcement Officers and they have been primary partners in creating the forensic laboratory. Since then, the laboratory has expanded its clientele, offering wildlife forensic services to approximately thirteen states. The laboratory still mainly focuses on the same analyses, but with vast improvements in technology. The forensic section of the laboratory is solely focused on enforcement questions and, other than validations, does not conduct or participate in research, making the laboratory one of the few wildlife forensic laboratories in the United States dedicated to wildlife law enforcement.

Enforcement questions that the laboratory answers include: what is the species of origin of the evidentiary item, what is the sex, how many individuals are represented by the items and do any of the items originate from each other or a known individual? The laboratory works with many trophy game and big game species including: mule deer (O. hemionus), white-tailed deer (O. virginianus), moose (Alces alces), elk (Cervus canadensis), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), mountain lion (Puma concolor), bobcat (Lynx rufus), black bear (Ursus americanus), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis), mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), turkey (Meleagris), sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), and barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia).

The laboratory receives approximately 80-90 cases per year, consisting of simple and complex cases. The simple cases generally consist of one to ten good quality items (i.e. items that comprise abundant high-quality DNA or sufficient protein) for species identification, sex identification, matching, or all three. The complex cases generally consist of a large quantity of samples with varying degrees of quality. In general, the more complex cases consisting of numerous samples and numerous sample types require more testing, which leads to more decision points compared to the simple cases. Due to the number of species analyzed and the number of states the laboratory performs testing for, the laboratory hosts a large number of reference samples separated by species and states and broken further into herd or unit areas within each state. Currently the laboratory has a reference database consisting of 36,720 samples with the number growing yearly.

This original paper outlines details for a complex case and a simple case received for analyses by the Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Forensic laboratory. The information presented in this paper was extracted from the laboratory’s case files. Specific details such as evidence descriptions, laboratory items, officer names and locations have been altered to maintain confidentiality. The complex case was received by the laboratory first, therefore, it will be presented before the simple case.

2 Methods

The two cases covered in this manuscript use a variety of methods and protocol for species identification, sex identification, STR amplification and STR analysis. Specific technical parameters for these methods are listed in the Supplementary Data Sheet 1 (complex case) and Supplementary Data Sheet 2 (simple case).

2.1 DNA extractions

DNA extractions were performed using three different methods: the tissue and blood samples were extracted using a phenol chloroform organic extraction protocol (Sambrook et al., 1989). Additionally, many of the blood samples were washed with a silica cleanup protocol to remove excess heme and any other environmental contaminants. Hair samples were extracted using the same phenol chloroform organic extraction protocol as the tissue and blood samples (Sambrook et al., 1989) with the addition of 20µl of 1M DTT (DL-Dithiothreitol) per DNA extraction.

Every test method performed for wildlife forensic case work at the Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Forensics Laboratory runs a positive and negative control. The negative control moves with the case throughout the entire testing process starting with DNA extractions. The positive controls are test specific and must produce a validated result for use. In the event a control fails the results are recorded in the bench notes and the testing starts over. The lab does not report test results with failed positive or negative controls.

2.2 Species identification

Three methods were used for species identification. Sanger sequencing (Sanger et al., 1977) was performed on all unknown samples as well as positive and negative controls using the mtDNA gene region CytB with universal primers ‘mcb 398’ and ‘mcb 869’ (Verma and Singh, 2002; primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Data Sheet 1). The samples were ran on a 3500 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and the resulting sequences were analyzed in Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis (MEGA) v. 11.0.13 (Tamura et al., 2021) and then compared with sequences from NCBI using BLAST (Clark et al., 2016; Sayers et al., 2022) to determine the species of origin. DNA sequencing alone cannot differentiate between Odocoileus spp. Therefore, samples that sequenced out to be from the Odocoileus spp. had to be further tested using protein serology or STRs for species assignment.

Protein serology was used by the laboratory for taxonomic identification of blood samples (Mardini, 1984; ANSI/ASB Standard 106, 2020). Serum albumin is an excellent protein to identify species from tissue and blood samples. This protein is the most abundant plasma protein and is found throughout the extravascular spaces of the body, maintaining the interstitial fluid colloid osmotic pressure. Serum albumin is a strongly anionic monomeric protein that can be readily separated from other tissue proteins by electrophoresis (Murch and Budowle, 1986; Melsert et al., 1989; Signore et al., 2017). A key application of the Albumin Western blot analysis is the differentiation of the four closely related members of the Cervidae family (mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, and moose). Electrophoresis was ran on a Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology PhastSystem with positive and negative controls.

The validation of OdoPlex (Hamlin et al., 2021) enabled the use of DNA STRs to differentiate species of Odocoileus spp. Multiplex PCR amplification was performed on the unknown samples that were identified as Odocoileus spp. based on sequence analysis, using the OdoPlex multiplex STR panel (Hamlin et al., 2021). STR amplification and analysis was performed using the parameters listed in Supplementary Data Sheet 2. In order to determine the species of origin, the alleles associated with each item were compared with an in-house database of known mule deer and white-tailed deer alleles and analyzed with GenAlEx6.51b2 (Peakall and Smouse, 2006; Peakall and Smouse, 2012).

2.3 Sex identification

Sex identification of the Odocoileus spp, C. canadensis and U. americanas samples was amplified using multilocus STR panels. The sex identification primers are listed in Supplementary Data Sheet 1. Samples originating from O. hemionus and O. virginianus were amplified with the OdoPlex STR panel (Hamlin et al., 2021). The sex-linked mammal-specific ZFX markers (Aasen and Medrano, 1990), which amplifies females at an amplicon size of ~443bp and an Artiodactyla-specific Y-chromosome linked SRY marker (Wilson and White, 1998) to amplify males at an amplicon size of ~190 bp were used.

Sex identification loci of C. canadensis samples was amplified, in a similar manner, with a multilocus STR panel referred to as WapitiPlex (Jones et al., 2002; Meredith et al., 2005; Meredith et al., 2007). In addition to the sex-linked mammal-specific ZFX and the Artiodactyla-specific Y-chromosome linked SRY marker the panel also includes a mammal-specific ZFY marker (Fain and LeMay, 1995) at an amplicon size of ~221bp.

Amplification of the sex identification markers for U. americanus was performed using the multilocus STR panel, UrsaPlex (Meredith et al., 2020) markers. An X chromosome linked bear-specific ZFX marker with an amplicon size of ~163bp and two Y chromosomes linked bear-specific markers (SMCY and 318.2) (Bidon et al., 2013) with amplicon sizes of ~106 bp and ~129 bp respectively were used.

Sex identification of Antilocapra americana, Alces alces and Meleagris spp. were amplified with specific sex markers and ran on a 5% agarose gel. Band separation imaging was visualized using a UV light and camera system (IGenius 3). PCR amplification of the polymorphic region of the ZFX/ZFY and SRY (P1-3EZ/P1-5EZ and Y53-3C/Y53-3D) locus was used to determine the sex of A. alces. Sex identification of A. americana was performed under the same conditions with the exception of the Y primer SRY (Y53-3E/Y53-3F) (Fain and LeMay, 1995). In Meleagris spp. the female is the heterogametic sex (ZW). The sex identification of Meleagris sp. was performed using primers Pst1 with amplification at ~177-bp and ATP amplification at ~250-bp (D’Costa and Petitte, 1998).

2.4 STR amplification

Multiplexed PCR amplifications were performed on the Odocoileus spp. (OdoPlex) (Hamlin et al., 2021), C. canadensis (WapitiPlex) (Jones et al., 2002; Meredith et al., 2005; Meredith et al., 2007) and U. americanas (UrsaPlex) (Meredith et al., 2020) samples with the QiagenⓇ Multiplex PCR kit using ten to sixteen STRs. Primers for the individual species are listed in the Supplementary Tables S1–S3. Forward primers of all STR and sex identification loci were labeled with fluorescent dyes (6FAM, VIC, NED and PET; ThermoFisher Scientific) following the parameter set forth in the species specific validation studies (Hamlin et al., 2021 and Meredith et al., 2020). Multiplex PCR reactions was ran using a BioradⓇ Thermal Cycler. Fragment separation was performed on Applied Biosystems 3500 Genetic Analyzer using the Fragment Analysis50_POP7_G5 module.

Singleplex PCR amplifications were performed on Alces alces (Wilson et al., 1997; Talbot et al., 1996; Smith et al., 2002; Bishop et al., 1994; Vaiman et al., 1994), Antilocapra americana (Bishop et al., 1994; Lou, 1998; Carling et al., 2003; Stephen et al., 2010) and Meleagris (Huang et al., 1999; Reed et al., 2000). Primers for the individual species are listed in the Supplementary Tables S4–S6. An IRDye 700 or 800 M13 tail was added to each reaction depending on the validated procedure.

The PCR reactions were ran using a BioradⓇ Thermal Cycler and fragment separation was performed on a LiCor Sequencer.

2.5 STR analysis

All multiplex STR analysis was performed with GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems™). While the singleplex reactions were analyzed with Saga™ software (LiCor). The individual genotypes were visually inspected and scored by qualified analysts. The unique genetic profiles were recorded for each sample to determine individualization, minimum number of animals and sex identification.

3 Case 1- complex wildlife forensic case

3.1 Case overview

In 2024 the laboratory received a wildlife forensic case submission from a District Wildlife Officer from Colorado Parks and Wildlife. A total of 59 items were submitted for examination. The submission form, which the submitting officer filled in, stated that items #1 and 2 originated from mule deer (O. hemionus) of unknown sex. At the time of submission, the officer did not know if other species were present in the evidentiary items and the known mule deer samples were the only species in question. The investigation aimed to address the following objectives:

● Species identification of items #3-59.

● Sex identification of all items.

● Number of individual animals in the submitted items.

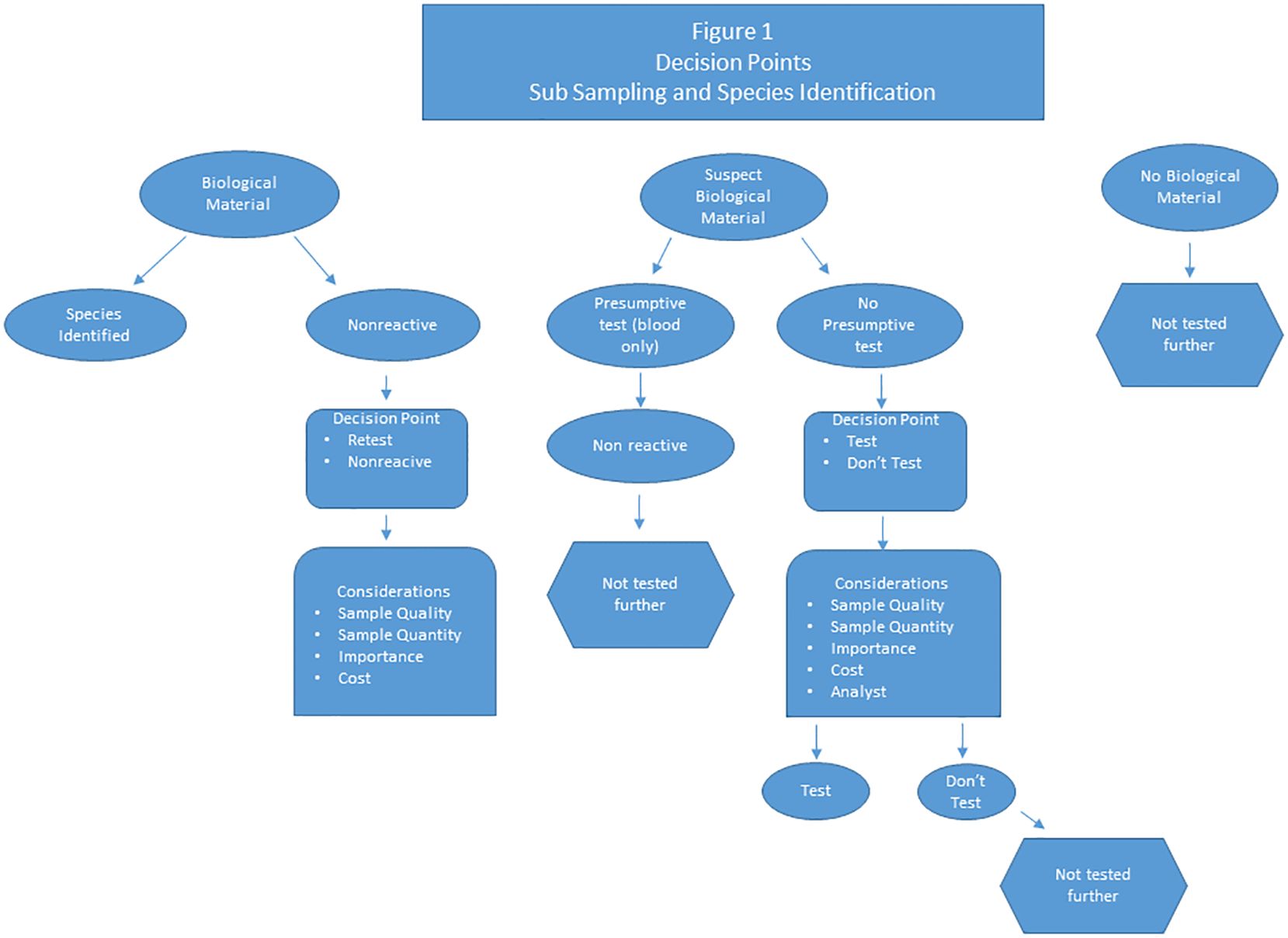

A few critical decision points can streamline complex cases and save time and costs. The majority of these decision points are made during the subsampling process, but are also littered throughout the entire process. The flowchart in Figure 1 highlights the different decision points in analyzing cases, especially the more complex ones. One of the most important decision points is to determine when to stop analyses on a specific sample and report the sample as either nonreactive or inconclusive. Several factors should be considered at this step. Does the sample quality appear to be so poor that retesting may not work? How important is the sample to the case, is it one of several blood samples from the same item or is it a highly important sample? Is there enough sample to retest? How many times to retest before it becomes cost prohibitive? These factors can be considered multiple times throughout the retesting of one sample and there is always the possibility that the sample will have to be called nonreactive regardless of the importance to the case. If the item appears to have biological material and the laboratory has a presumptive test (blood) then the sample should be tested and the presumptive test should be performed prior to further testing. However, if there isn’t a presumptive test available, should the sample be tested anyway? Also, determining if there is any reason to start analyses of a specific item in the first place is a crucial decision point. For example, if the analyst does not visually identify any biological material, should the sample be tested?

In the highlighted complex case, fifty-nine samples were submitted for testing. One of the first, and sometimes the most difficult, decisions made at this juncture is determining whether or not a submitted item is suitable for downstream analyses. If a large number of samples are submitted for forensic testing, the laboratory analysts carefully examine each item to evaluate if the item contains forensically useful biological material. In this complex case, the evidentiary items (Table 1) included two tissue samples from mule deer of unknown sex, eleven blood and hair samples from various clothing items, six blue shop rags with possible blood and hair, thirty-three hunting items with blood and/or hair, two coolers with blood and five miscellaneous blood and hair items. The suspect blood and the hair samples from the various clothing, shop rags, hunting items, coolers, and miscellaneous samples consist of the most difficult of the samples. Is the suspect blood actually a true blood sample? Do the hairs have any root ends? Even though the hunting items were submitted as having forensically useful material, is that material actually present?

During the sampling of this case, it was determined that four of the clothing items and five of the blue shop rags, when visually inspected for hair, blood, or tissue did not have any biological material. At this point, these items were not sampled for downstream testing and this was noted in the case notes.

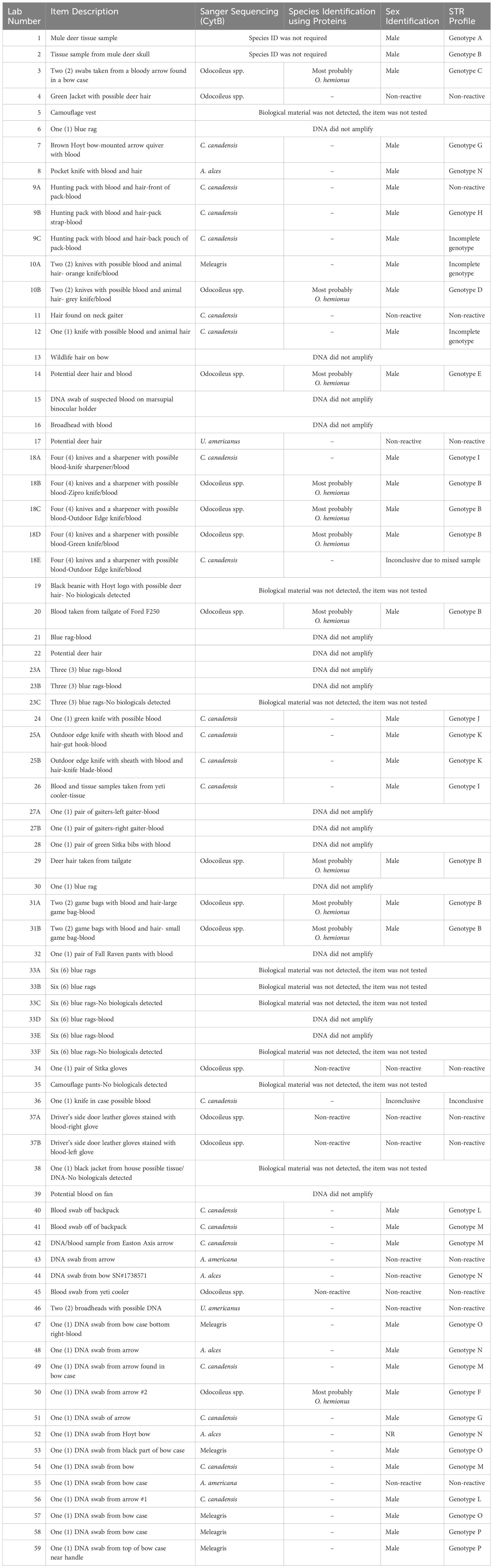

Although only fifty-nine evidentiary items were submitted to the laboratory for the complex case and several of the submitted items did not have biological material, the number of items totaled sixty-eight (Table 1). This is because multiple subsamples can be collected from the same item, these additional items are identified with a capital letter after the item number (Table 1). For instance, if a shirt is submitted as one piece of evidence with multiple blood stains, several blood stains can be collected and treated as individual items. These subsampled items consisted of tissue, blood, and hair with the possibility of various environmental contaminants that may have the potential to inhibit downstream analyses. Sample types and inhibitors can dictate which of the several validated extraction protocols to use.

3.2 Results and conclusions

The genetic methods used to address the objectives in this case are described in the Methods section, with detailed methods listed in Supplementary Materials S1.

Species identification was performed on the samples that contain biological material, as well as a positive and negative control. The Sanger sequencing method was implemented using the mitochondrial gene CytB on the unknown items. Sequencing alone cannot differentiate between Odocoileus spp. Therefore, any of these samples that sequenced out to be from the Odocoileus spp. had to be further tested using protein analysis. All other samples were identified to species and ready for downstream analyses. Species identification results for individual items are listed in Table 1.

The fifteen blood samples that sequenced to the Odocoileus spp. had further testing using protein serology performed to determine their species of origin, either O. hemionus or O. virginianus.

At the time of this case, the Albumin Western blot test was the only test method the laboratory had validated to differentiate between mule deer and white-tailed deer. As with all analyses, positive controls were ran with the unknowns.

Species identification using DNA sequencing indicated twenty items originated from elk (Cervus canadensis), sixteen items originated from the Odocoileus spp. (O. hemionus or O virginianus), four items originated from moose (A. alces), six items originated from turkey (Meleagris), two items originated from black bear (U. americanus) and one item originated from pronghorn (A. americana). Additional species identification of the sixteen Odocoileus spp., using albumin IEF, resulted in eleven items most probably originating from mule deer (O. hemionus). Protein analysis is a reliable method for differentiating between mule deer and white-tailed deer, the method relies heavily on the analyst’s ability to score IEF gels and clean protein samples. Due to these factors the laboratory protocol states that when reporting of Odocoileus spp. using a protein test method a qualifying factor will be used, hence the most probably mule deer.

Sex identification and STR genotyping were performed on all items that produced a result for species identification. These results are listed in Table 1.

Several items were non-reactive for species identification making this a critical decision point in the laboratory. How many times should the sample be retested prior to determining it is non-reactive? The answer to this depends on the quality of the sample, the importance of the sample, and is also based on analyst experience. If a sample is determined non-reactive at this point, further testing is not performed.

3.3 Summary

This complex case highlights several key points when making decisions to move a wildlife forensic case through the laboratory.

● Items that do not contain biological material may not need testing.

● When DNA is degraded, it can be difficult to obtain a complete species identification profile or STR genotype profile, the laboratory needs parameters in place to address difficult samples such as these.

● It is important to know the laboratory’s limitation, this will direct downstream workflow (i.e. additional species identification, to determine use of multiplex STR panel’s vs singleplex STRs and sex identification markers). Limitations are identified through method validations.

● Have a set of critical decision points set up for processing complex cases, as this will provide guidance on when to stop testing or when to change test methods.

● Laboratory analysis cost is a critical factor in the decision process (i.e. whether to test/re-test a sample)?

The results in this case demonstrated that there were five additional species outside the known mule deer items #1 and 2. It was critical that the laboratory had protocols in place to handle the sub sampling, processing, testing and reporting of the items to successfully answer the objectives in this case. The results were provided to the submitting officer to either support or refute their investigation and to provide a report in the event this case makes it to the judicial system. At this time the laboratory does not know the outcome of this case.

4 Case 2- simple wildlife forensic case

4.1 Case overview

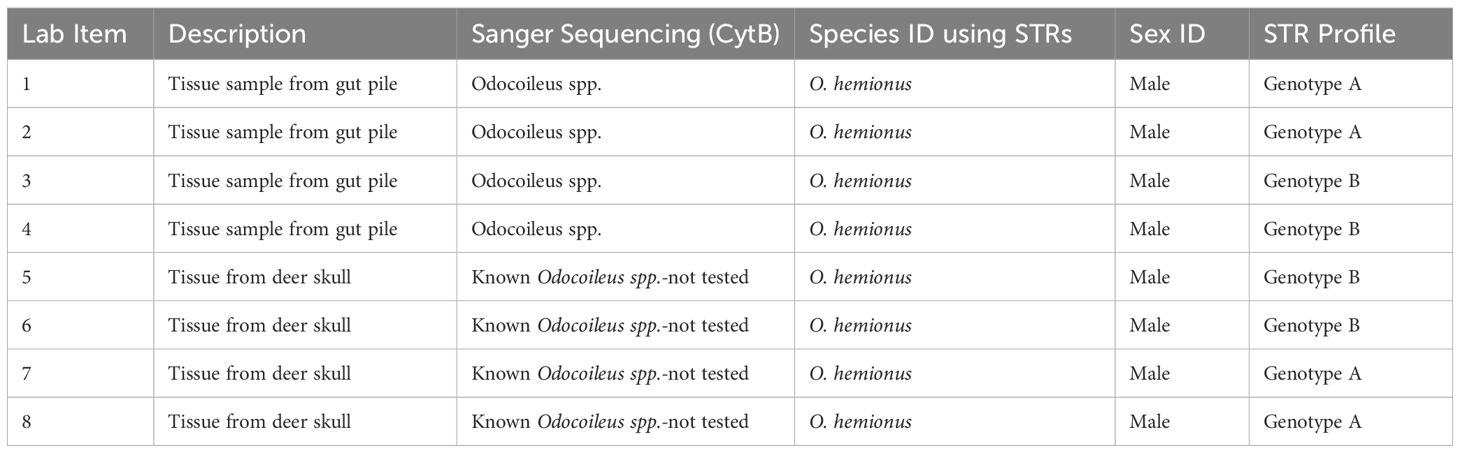

Early 2024 the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish submitted eight samples for forensic examination. Items #1-4 consisted of tissue samples from a gut pile and items #5-8 were tissue samples from known mule deer (O. hemionus). Using the submission request form, the Investigator requested the following (Table 2):

● Species identification of items #1-4.

● Sex identification of all eight items.

● STR genotyping on all eight items.

Eight tissue samples approximately 5 mm x 5 mm in size stored in desiccant tubes were submitted for testing. Since the items submitted were tissue samples, sub sampling was straight forward and technical decision points were not required to determine if the sample type is biological material and eliminated the need for any presumptive testing. Also, four of these samples were submitted as originating from a known species, eliminating the need for species identification. In this case, approximately 100 mg of tissue from each item submitted was collected for downstream analysis. The eight tissue samples went through the laboratory’s phenol chloroform organic extraction protocol (Sambrook et al., 1989) and did not require additional DNA clean-up.

This simple case was chosen to highlight the importance of validating new test methods. Before discussing the results and conclusions of the simple wildlife forensic case, a brief overview of the validation of OdoPlex for species assignment is in order. This validation was implemented after the complex case and before the simple case was tested in the laboratory.

4.2 Validation of OdoPlex for species assignment

All new test methods routinely used at the Wyoming Game and Fish Forensics Laboratory are validated via a full validation process following the laboratory’s Quality Manual section on developmental and/or internal validation. The validations also follow the validation guidelines for DNA analysis methods recommended by the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM, 2016).

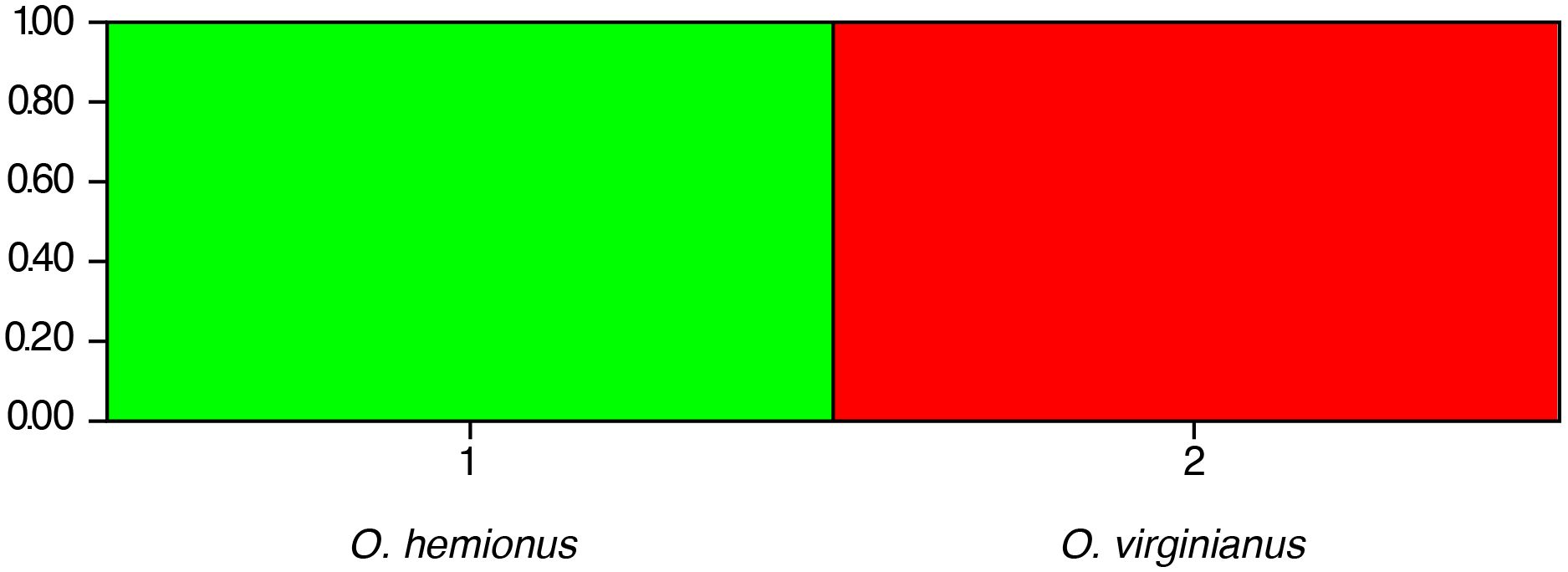

Shortly after the complex case was completed the laboratory performed an internal validation using OdoPlex (Hamlin et al., 2021) to differentiate between O. hemionus and O. virginianus species. This STR multiplex panel was previously validated for use for individualization, leading the way for the internal validation for species identification. Hamlin et al., 2021. demonstrated that the OdoPlex STR multiplex panel can be used as a diagnostic tool to determine species identity of the two closely related deer species and several subspecies. The laboratory’s internal validation focused on the identification of O. hemionus and O. virginianus.

Tissue samples from 313 deer, including 143 known mule deer (O. hemionus), 150 known white-tailed deer (O. virginianus) and 20 deer of unknown species (selected by a third party for species assignment) from Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado were selected. These samples were collected by law enforcement officers and agency biologists, primarily from hunter harvested deer and are stored in the laboratory’s in-house database. DNA was extracted using a phenol chloroform organic extraction protocol (Sambrook et al., 1989). PCR optimization, amplification, and capillary electrophoresis were performed following the process listed in the Methods section for OdoPlex.

Sixty-one individuals were analyzed using STRUCTURE (v2.3.4) (Pritchard et al., 2000; Evanno et al., 2005). The data set was analyzed with two populations assumed, with a 100,000 Burn-in period, and 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo repetitions for 10 iterations (K = 1-18). Results were analyzed using Evanno’s Best K (Evanno et al., 2005) and plotted with a bar graph to determine if species separation was possible. Results from STRUCTURE clearly demonstrated that the OdoPlex STR panel (Hamlin et al., 2021) can differentiate between the two Odocoileus spp. It is important to note that all sixty-one individuals produce a complete profile. The bar plot (Figure 2) demonstrates that both species clearly separate when a full genetic profile is produced using the Odoplex STR panel.

Figure 2. STRUCTURE plot showing subdivision of O. hemionus (Population 1: green) and O. virginianus (Population 2: red) when evaluated with the OdoPlex STR panel. Each sample evaluated produced an entire STR profile.

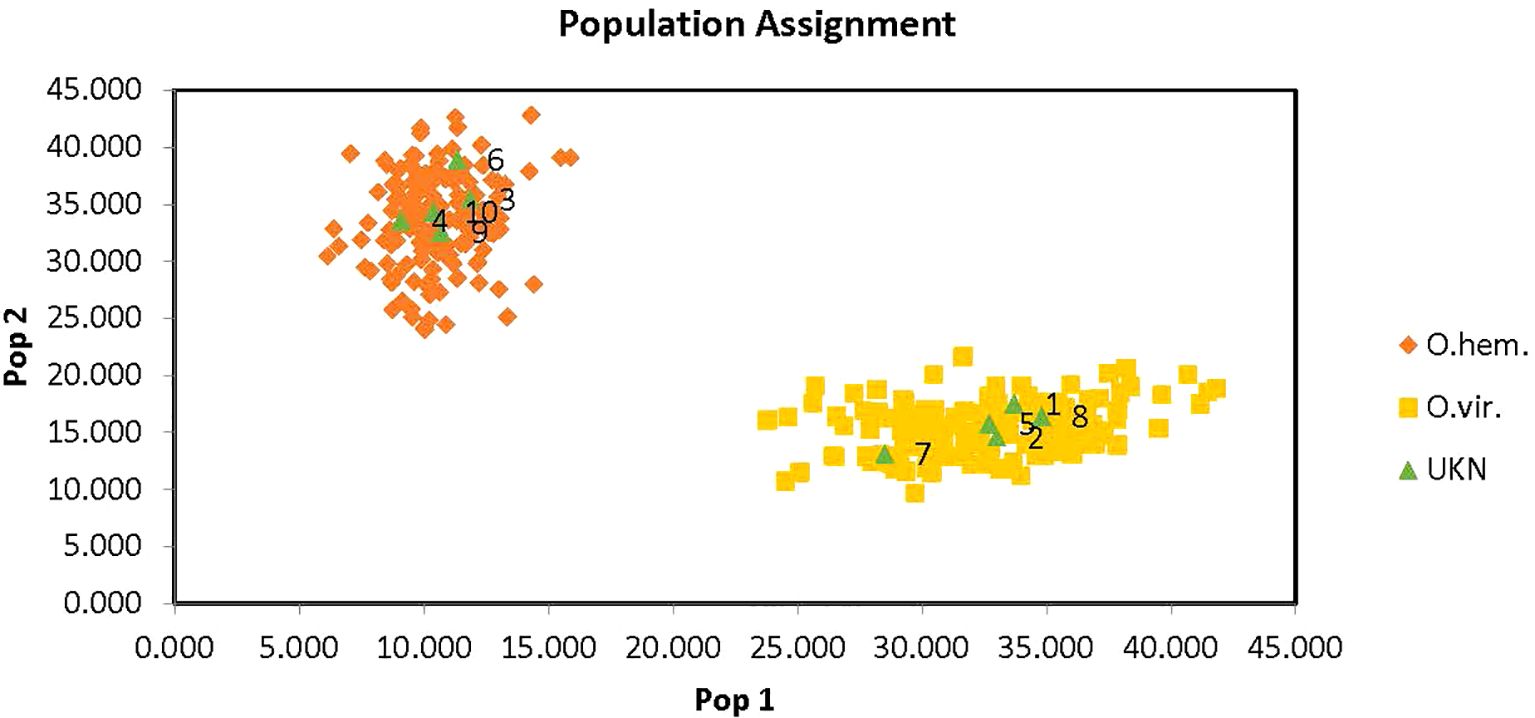

The same sixty-one individuals were analyzed using GenAlEx (Peakall and Smouse, 2006; Peakall and Smouse, 2012). Although both programs correctly identified two species, GenAlEx was determined to be the best fit for the laboratory’s data formatting. Therefore, only GenExAl was used to analyze the larger data set of 313 deer to assign the unknown deer samples. GenAlEx demonstrated that the OdoPlex STR multiplex (Hamlin et al., 2021) plan can be used to determine species assignment using microsatellites to differentiate between mule deer and white-tailed deer with 100% accuracy of species assignment of unknowns. OdoPlex (Hamlin et al., 2021) has a number of species-specific alleles that can be used in conjunction with population assignment software to determine the species of unknown evidentiary items. Figure 3 demonstrates species assignment of ten unknown deer samples using GenAlEx. The green unknown triangles plotted in the figure show the correct assignment of all ten unknown deer samples.

Figure 3. GeneAlEx assignment graph with ten unknowns samples properly assigned. The orange diamonds represent O. hemionus species and the yellow squares represent O. virginianus species. They green triangles are the unknown samples that were run with the known database for species identification using OdoPlex STRs. All unknowns were correctly assigned.

Additionally, as demonstrated in the original developmental validation for species determination using OdoPlex (Hamlin et al., 2021), OarFCB193 has a fixed allele at “10” when ran with O. hemionus. The observation of a fixed allele at “10” was seen at 100% during the internal validation with OarFCB 193 in all Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado mule deer that have been tested on OdoPlex. A small number of O. virginianus samples that were heterozygous at the “10” locus at OarFCB193 were detected. This was seen 1% of the time. With this observation and the fact that the Wyoming Game and Fish work with both deer species on a regular basis, it was determined that the entire OdoPlex panel (Hamlin et al., 2021) would be used for species assignment.

Key points to consider when using OdoPlex for species assignment:

● The observation of a fixed allele at “10” is a strong indicator of the O. hemionus, however in a laboratory that works with both O. hemionus and O. virginianus, using the entire Odoplex STR panel for species assignment should be considered.

● If using Odoplex for species assignment of Odocoileus spp. protein testing is no longer needed.

● If a complete STR profile is not generated, species assignment may not be possible and the laboratory will have to report the DNA sequencing results of Odocoileus spp. either O. hemionus or O. virginianus.

4.3 Results and conclusions of a simple wildlife forensic case

Species identification was performed on the first four items using Sanger sequencing of the CytB gene. DNA sequencing indicated all four items originated from the Odocoileus spp. meaning additional testing was required to determine species of origin. Previously, the laboratory used proteins to determine O. hemionus and O. virginianus. However, with the new validation of OdoPlex (Hamlin et al., 2021) to differentiate species of Odocoileus DNA STRs were used to determine species of origin. Species identification using OdoPlex for population assignment indicated the four items originated from mule deer (O. hemionus).

Sex identification and STR genotyping was performed on all eight samples using the parameters listed in the Methods section. The results, using Odoplex for genotyping, sex identification, and species identification are in Table 2.

4.4 Summary

This simple case highlights a couple of key points when making decisions to move a simple wildlife forensic case through the laboratory.

● Tissue samples simplify the subsampling process and can eliminate several critical decision point needed to move a case forward.

● Validating new test methods such as OdoPlex for species assignment can improve the laboratory’s test methods and turnaround times.

● Internal validations are needed and are important for subsequent casework (i.e. finding a heterozygote for a locus that was thought to be fixed at a major allele).

The results in this case demonstrated that there were two male mule deer. The implementation of OdoPlex for species assignment played a key role in species identification of this case. The results were provided to the submitting officer and they supported their investigation. The results in this case led to the defendant pleading guilty to taking of big game animals without the required license. Their plea resulted in several thousand dollars in fines and restitution and the loss of their hunting privileges for one year.

5 Discussions and conclusions

The number and quality (i.e. no viable DNA or contamination) of items submitted in cases play a significant role in determining if the case is going to be considered easy or complex. A case with a large number of evidence items or poor sample quality often leads to more decision points, making it complex. For example, a tissue sample is easier to extract viable genetic material from than a small blood sample or other trace evidence. Environmental conditions prior to sample submission also affect the viability of a sample. A sample that has been exposed to UV rays from the sun, or a sample that has been collected from soil run a higher risk of degradation and may not produce viable genetic material for further testing.

An analyst’s experience and knowledge along with the laboratory’s protocols are all vital components of these critical decisions. Several factors can determine how the analyst proceeds with testing, including the number of samples collected from the evidence, the number of times to retest the sample, and perhaps even cost restrictions. In this instance, the cost savings is in knowing when not to test a sample or, if testing the sample, how many times to test prior to accepting a non-reactive result.

It is important in a wildlife forensic laboratory to continue to develop and validate new procedures. For example, the validation of population assignment to differentiate between mule deer and white-tailed deer effectively increased efficiency and reduced costs. In this instance, the cost savings is captured in analyst time and in that one multiplex is answering two questions; matching and species.

Since the completion of the complex case, the laboratory has also validated pronghorn with a multiplex panel and is in the process of validating moose following Development and Implementation of a STR Based Forensic Typing System for Moose (Alces alces) (Sim et al., 2021). The validation of these new panels enable the laboratory to combine sex identification and STRs for matching in the same panel further increasing efficiency and cost savings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because Samples were collected as standards/evidence.

Author contributions

KF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2025.1518608/full#supplementary-material

References

Aasen E., Medrano J. F. (1990). Amplification of the zfy and zfx genes for sex identification in humans, cattle, sheep and goats. BioTechnology. 8, 1279–1281. doi: 10.1520/jfs16172j

ANSI/ASB Standard 106 (2020). Wildlife Forensics-Protein Serology Method for Taxonomic Identification. Available online at: https://www.aafs.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/106_Std_e1.pdf (Accessed January 2020).

Bidon T., Frosch C., Eiken H. G., Kutschera V. E., Hagen S. B., Aarnes S. G., et al. (2013). A sensitive and specific multiplex PCR approach for sex identification of ursine and tremarctinae bears suitable for non-invasive samples. Mo. Ecol. Resour. 13, 62–368. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12072

Bishop M., Kappes S., Keele J., Stone R., Sunden S., Hawkins G., et al. (1994). A genetic linkage map for cattle. Genetics 136, 619–639. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.2.619

Carling M. D., Passavant C. W., Byers J. A. (2003). DNA microsatelliltes of pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) Molecular Ecology. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00334.x

Clark K., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J., Sayers E. W. (2016). GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D67–D72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1276

D’Costa S., Petitte J. N. (1998). Physiology and reproduction: sex identification of Turkey embryos using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Poultry Science. 77, 718–721. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.5.718

Evanno G., Regnaut S., Goudet J. (2005). Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study, Mol. Ecol 14 (8), 2611–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x

Fain S. R., LeMay J. P. (1995). Gender identification of humans and mammalian wildlife species from PCR amplified sex linked genes. Proc. Am. Acad. Forensic Sci. 1, 29.

Hamlin B. C., Meredith E. P., Rodzen J., Strand J. A. (2021). OdoPlex: An STR multiplex panel optimized and validated for forensic identification and sex determination of North American mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Forensic Sci. Int. 1. doi: 10.1016/j.fsiae.2021.100026

Huang H.-B., Song Y.-Q., Hsei M., Zahorchak R., Chiu J., Teuscher C., et al. (1999). Development and characterization of genetic mapping resources for the Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). J. Heredity 90 (1), 240–242. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.1.240

Jones K. C., Levine K. F., Banks J. D. (2002). Characterization of 11 polymorphic tetranucleotide microsatellites for forensic applications in California elk (Cervus elaphus canadensis). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2, 425–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2002.00264.x

Lou Y. (1998). Genetic variation of pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) populations in North America. Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University, College Station. Ph.D. dissertation.

Mardini A. (1984). Species identification of tissues of selected mammals by agarose gel electrophoresis. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 12, 249–251.

Melsert R., Hoogerbrugge J. W., Rommerts. F. (1989). Albumin, A biologically active protein acting on Leydig cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 64 (1), 35–44. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(89)90062-2

Meredith E. P., Adkins J. K., Rodzen J. A. (2020). UrsaPlex: an STR multiplex for forensic identification of North American black bear (Ursus americanus). Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 44, 102161. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2019.102161

Meredith E. P., Rodzen J. A., Banks J. D., Schaefer R., Ernest H. B., Famula T. R., et al. (2007). Microsatellite analysis of three subspecies of elk (Cervus Elaphus) in California. J. Mammology 88, 801–808. doi: 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-014R.1

Meredith E. P., Rodzen J. A., Levine K. F., Banks J. D. (2005). Characterization of an additional 14 microsatellite loci in California Elk (Cervus elaphus) for use in forensic and population applications. Conserv. Genet. 6, 151–153. doi: 10.1007/s10592-008-9525-1

Murch R. S., Budowle B. (1986). Applications of isoelectric focusing in forensic serology. J. Forensic Sci. 31, 869–880. doi: 10.1520/JFS11096J

Peakall R., Smouse P. E. (2006). GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mo. Ecol. 28 (19), 2537–2539. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.01155.x

Peakall R., Smouse P. E. (2012). GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinformatics 28 (19), 2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460

Pritchard J. K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. (2000). Inference of population structure using mutilocus genotype data. Genetics 155 (2), 945–959. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/aticles/pmc1461096/.

Reed K. M., Robert M. C., Murtaugh J., Beattie C. W., Alexander L. J. (2000). Eight new dinucleotide microsatellite loci in Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Anim. Genet. 31, 140–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2000.00571.x

Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed (New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor).

Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. (1977). DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U.S.A. 74 (12), 5463–5767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463

Sayers E. W., Bolton E. E., Brister J. R., Canese K., Chan J., Comeau D. C., et al. (2022). Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (D1), D20–D26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1112

Signore M., Manganelli V., Hodge A. (2017). Antibody validation by western blotting. Methods Mol. Biol. 1606. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6990-6_4

Sim Z., Monderman L., Hildebrand D., Packer T., Jobin R. (2021). Development and implementation of a STR based forensic typing system for moose (Alces alces). Forensic Sci Int Genet. 53, 102536. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2021.102536

Smith P., DenDanto D., Smith K., Palman D., Kornfield I. (2002). Allele frequencies for three STR loci RT24, RT0, and BM 1225 in northern New England white-tailed deer. J. Forensic Sci. 47 (3), 673–675. doi: 10.1520/JFS15312J

Stephen C. L., Whittaker D. G., Gillis D., Cox L. L., Rhodes O. E. (2010). Genetic consequences of reintroductions: an example from Oregon pronghorn antelope. J. Wildlife Manage 69 (4), 1463–1474. doi: 10.2193/0022-541X(2005)69[1463:GCORAE]2.0.CO;2

SWGDAM (2016). Scientific working group on DNA analysis methods, validation guidelines for DNA analysis methods. Available online at: https://1ecb9588-ea6f-4feb-971a-73265dbf079c.filesusr.com/ugd/4344b0_813b241e8944497e99b9c45b163b76bd.pdf.

Talbot J., Haigh J., Plante Y. (1996). A parentage evaluation test in North American Elk (Wapiti) using microsatellites of ovine and bovine origin. Anim. Genet. 27 (2), 117–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1996.tb00480.x

Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. (2021). MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

Vaiman D., Mercier D., Moazami-Goudarzi K., Eggen A., Ciampolini R., Lépingle A., et al. (1994). A set of 99 cattle microsatellites: characterization, synteny mapping and polymorphism. Mamm. Genome 5, 288–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00389543

Verma S. K., Singh L. (2002). Novel universal primers establish identity of an enormous number of animal species for forensic application. Mol. Ecol. Notes 3 (1), 28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-8286.2003.00340.x

Wilson G., Strobeck C., Wu L., Coffin J. (1997). Characterization of microsatellite loci in caribou Rangifer tarandus, and their use in other artiodactyls. Mol. Ecol. 6, 697–699. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1997.00237.x

Keywords: wildlife forensics, critical decisions, DNA sequencing, albumin, species assignment, STR genotyping

Citation: Frazier KM and Bauman TL (2025) Decision-making in wildlife forensics: comparing complex and simple cases at the Wyoming Game and Fish Laboratory. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1518608. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1518608

Received: 28 October 2024; Accepted: 24 January 2025;

Published: 14 March 2025.

Edited by:

Kyle Ewart, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Fraser John Combe, Theiagen Genomics, United StatesKelly A. Meiklejohn, North Carolina State University, United States

Alexandra Summerell, New South Wales Health Pathology, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Frazier and Bauman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kimberly M. Frazier, kim.frazier@wyo.gov

Kimberly M. Frazier

Kimberly M. Frazier