- 1African Community Center for Social Sustainability (ACCESS), Nakaseke, Uganda

- 2Department of Physiology, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda

- 3Nuvance Health/University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine Global Health, Burlington, VT, United States

- 4Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 5Administration, Nakaseke District Hospital, Nakaseke, Uganda

- 6Makerere University Business School, Kampala, Uganda

- 7Partners for African Community Center for Social Sustainability (ACCESS), Boston, MA, United States

The approaches to global health (GH) partnerships are as varied as the programs available across the globe. Few models have shared their philosophy and structure in sufficient detail to inform a full spectrum of how these collaborations are formed. Although contributions from low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) have markedly grown over the last decade, they are still few in comparison to those from high-income countries (HICs). In this article, we share the African Community Center for Social Sustainability (ACCESS) model of GH education through the lenses of grassroots implementers and their international collaborators. This model involves the identification and prioritization of the needs of the community, including but not limited to healthcare. We invite international partners to align with and participate in learning from and, when appropriate, becoming part of the solution. We share successes, challenges, and takeaways while offering recommendations for consideration when establishing community-driven GH programs.

Introduction

From its inception, the field of global health (GH) has been and continues to be defined and redefined, from its colonial roots to its neo-colonial present. GH can be understood as an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide (Koplan et al., 2009). Here, we focus our discussion on GH education, specifically the hosting of medical students, residents, faculty, and physicians from high-income countries (HICs) in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) during short-term clinical GH electives.

It is generally well understood that, despite touting mutuality and bidirectionality, most such partnerships are largely unidirectional and molded to their colonial beginnings. The task of “decolonization” is not only colossal but perhaps even impossible in a global framework in which all systems, from economic to social, are essentially colonial. The question of how to co-create and sustain GH partnerships in light of history, our experiences with past and current partnerships, and the social injustices that have been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic continues to resound. We hope to identify means of surpassing verbal calls for change and engage in actions that will allow us to move toward a shared vision. We need broad participation in this effort, from GH educators to the countless other overlapping sectors (Lu et al., 2021).

What we are up against is a well-entrenched narrative perpetuated by the media that overlooks Africa's richness, instead depicting the continent as resource-poor, a claim often over-exaggerated by participants in short-term GH electives (Bishop and Litch, 2000). When faculty and students from HICs visit LMICs, they find widespread poverty, poorly run institutions, corruption, fragile health systems, under-resourced health facilities, lack of basic health services, and professionals who seem inadequately trained and at times apathetic for the tasks they perform. In a tragic demonstration of confirmation bias, their eyes are trained to mainly observe what they think they already know. They often enter with the notion that they are “helping” by casting a set of fresh, knowledgeable eyes on a complex problem.

On the other hand, when faculty and students from LMICs visit HICs, they find people living in the lap of luxury with well-run institutions, robust and sophisticated health systems, well-resourced health facilities, quality healthcare, and highly trained professionals, with their knowledge and contributions too often underestimated. This imbalance reinforces the superiority/inferiority complex: the belief that leadership, institutions, values, culture, and other resources should be imported from HICs to develop LMICs (Kruk et al., 2018).

At first glance, visitors may find our system disorganized. They may even question our level of investment in our community. They identify multiple gaps across different sections of the health delivery system and independently offer spontaneous solutions, often transplanting ideas based on their experiences in HICs. What they fail to see is how our systems were developed to optimize the resources we know and trust.

We share our local resources with GH participants to help them appreciate that we do have resources that best align with the community's needs, though they may be different from those found in HICs. We have found means to put our resources to the best use, and they often do the job well. We try to dispel the myths of Africa as resource-poor by providing participants with direct experiences of its richness. We make it clear that the role of visitors who work with us in LMICs is to collaboratively identify available resources and use them appropriately and judiciously.

We prepare the visitors using extensive pre-departure orientation and education in GH's colonial history, bias, racism, inequality, poverty, and power structures, as well as simulations of difficult conversations around these topics based on on-the-ground experiences. To help nurture more open mindsets, we have compiled a case-based module based on our experiences with previous visitors' dilemmas for use as a teaching opportunity to help visitors understand the roots and realities of some of their observations. This article is centered on what ACCESS has done to work toward setting up a model GH program that is beneficial to visitors from HICs and hosts in LMICs alike.

The ACCESS model: roots

Unlike most GH programs that are run by major universities, ACCESS is a grassroots organization started by a group of community members who sought a holistic approach to addressing challenges faced in their community. Located in Nakaseke, a rural district approximately 65 km from Uganda's capital city of Kampala, our community consists largely of subsistence farmers.

ACCESS' origins as a health clinic serving patients living with HIV/AIDS were slow to start, as stigma kept patients at home, never seeking help. However, the program, through education by community health workers (CHWs), drama groups, and other outreach programs, transformed the community's attitude in Nakaseke so that the clinic became a site for the provision of general healthcare. Health awareness increased substantially, with patients now visiting the ACCESS clinic daily and an annual health day drawing thousands of residents for free consultations and treatment.

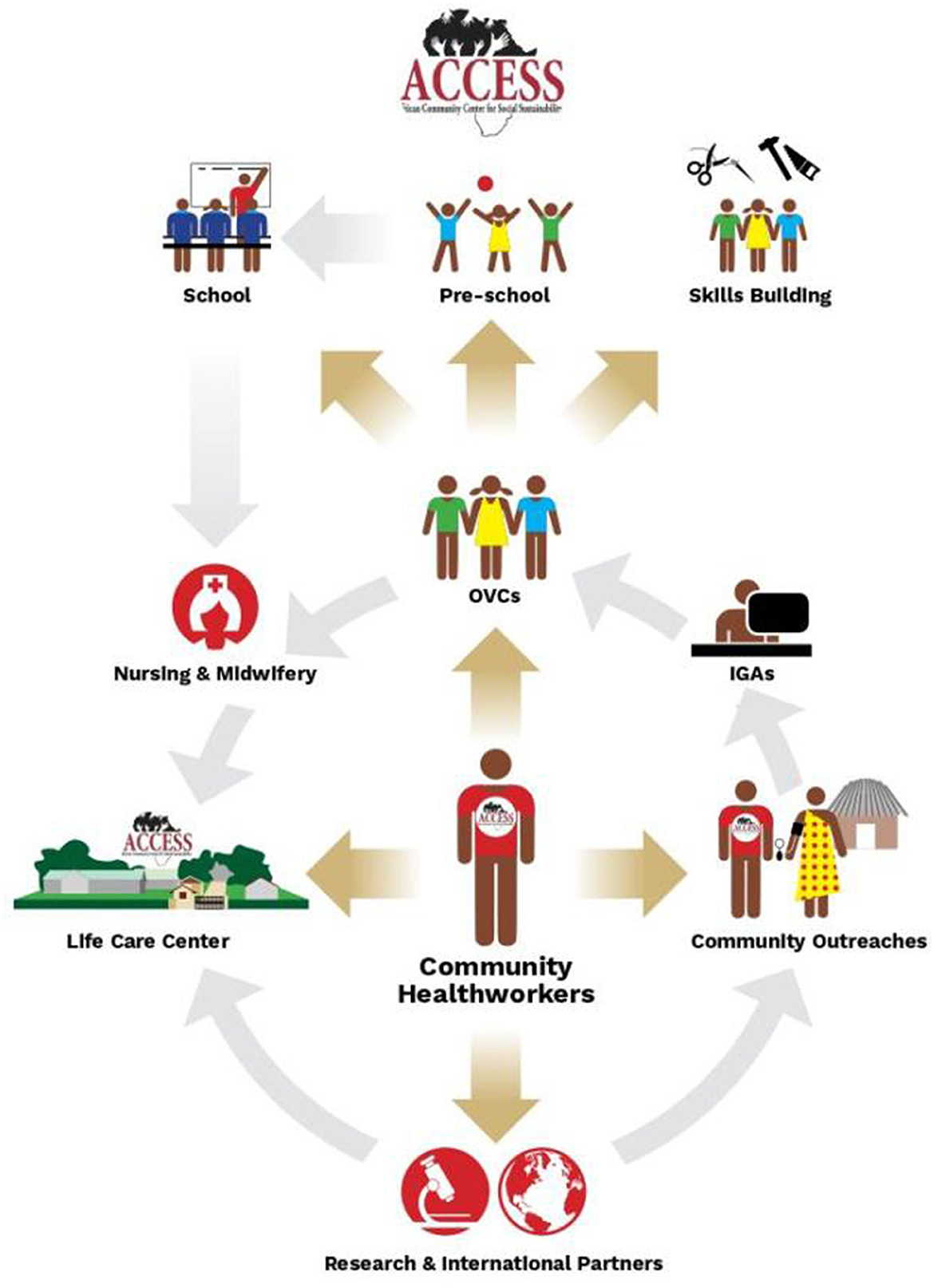

Since its inception, ACCESS has added three additional components: the CHWs training program, the ACCESS Nurses and Midwifery School, and Grace's Promise Preschool. To date, we have trained over 300 CHWs. These individuals are volunteers from local communities who assess, identify, and refer individuals for clinical and other services, including transportation to and from the hospital or clinic and offering in-home first-aid services. They also identify children from families affected by HIV/AIDS and provide them with support in the form of medication, nutritional supplements, and school tuition and materials. We also provide income-generating services such as cattle or gardens for their families. In this way, ACCESS supports healthy living from a multi-faceted perspective.

In Uganda, approximately 80% of the healthcare workforce lives in big towns, which constitute only 20% of the population. ACCESS sought to address this imbalance by setting up a training program based in Nakaseke. Originally a nursing assistant school, the nationally accredited ACCESS Nurses and Midwifery School in collaboration with Nakaseke District Hospital aims to improve access to medical services in underserved areas of Uganda. The majority of its graduates are incentivized to remain in rural areas to work and give back to their community (Sadigh et al., 2017). Additionally, ACCESS is located on 17 acres of land where all the activities are interlinked. This provides an opportunity for students to experience the serene environment surrounded by gardens, including gardens to grow food that enriches the diet of both the local community and international visitors.

Healthcare delivery

ACCESS provides health services throughout a person's lifespan. ACCESS offers both outpatient and inpatient medical services as well as community outreach through the medical mobile team and community-based health workers. As with previous years, in 2022, we served 446 pregnant women, immunized 1,575 children, and tested 3,185 children for malaria, of whom we treated 1,659 individuals. We offered health education to 46,064 individuals and provided outpatient services to 7,691 patients, with 287 patients admitted for an average of 5.6 days of hospital stay. The top four causes of admission in children were malaria, respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and malnutrition. Adults were treated for both infections and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). We offered 3,853 laboratory tests including kidney function tests, liver function tests, urinalysis, HIV, malaria, and other infectious screening tests, at the health facility, helping clinicians with the diagnosis. In addition, we performed 336 ultrasound scans (235–70% women) to aid in diagnosis using a visiting radiographer.

Working with 125 CHWs and the mobile clinic, we offer primary healthcare services, including disease prevention and health promotion. In 2022, we offered 44 community visits, reaching out to 146,064 individuals and providing family planning services to 38,086 women and men. The most common challenges for the youth were sexually transmitted infections as well as malaria and respiratory tract infections. Through our research collaboration, we screened 3,500 individuals for hypertension, high blood sugar, kidney disease, and chronic obstructive airway disease. Using the same CHW model, we were able to screen 786 women over 35 years of age for cervical cancer using an innovative self-administered cervical brush. These services are offered in line with guidelines from the Uganda Ministry of Health.

Programmatic elements

At ACCESS Uganda, we have empowered our people through three key areas: education, healthcare, and economic promotion. Our model involves the identification and prioritization of the needs of our community. We identify and support vulnerable children, providing them with a general education and employable skills. We have established a healthcare facility called the Lifecare Center, which works with 18 Ugandan government-supported facilities to deliver both outpatient and inpatient services as well as preventive services as outlined above.

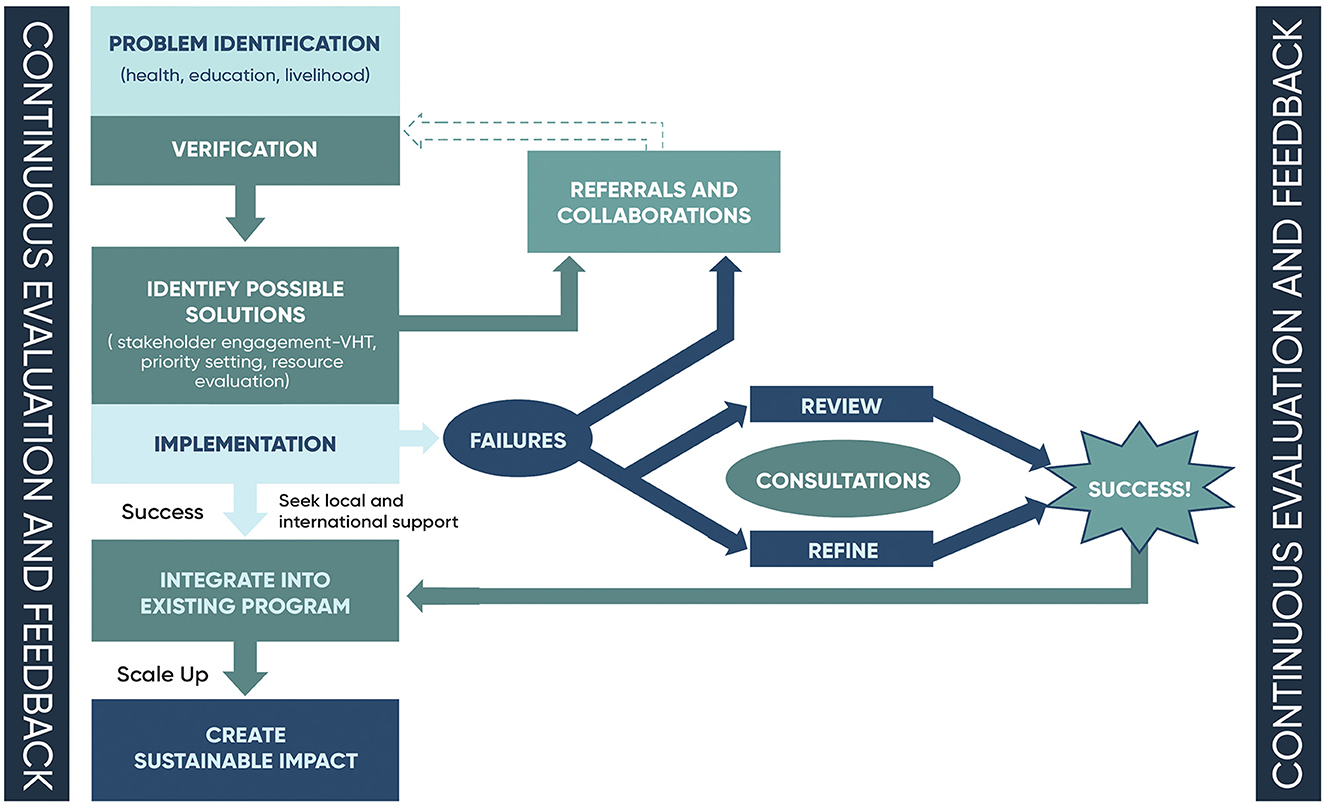

We economically empower families by teaching them subsistence skills and financial literacy while providing them with interest-free loans and projects that enable them to eradicate poverty and provide their families with basic needs. We invite international partners to align with community-based projects and become part of the solution. This promotes indigenous solutions through cross-pollination with international partners' contributions. Our model involves the identification of the community's needs, which are verified by community gatekeepers before solutions are implemented and scaled up for impact with the help of local and international partners (see Figure 1).

Over the past 12 years, we have partnered with several individuals and institutions in HICs through a variety of exchange programs. We have hosted faculty, residents, fellows, and medical students, and we have also sent a few of our faculty to HIC partners' institutions in order to provide a reciprocal learning experience. The needs of our community are always at the forefront when enacting reciprocal exchange. We believe that with direct exposure to our culture and language, visitors gain a deeper understanding of who we are and are therefore less likely to misuse their perceived knowledge and skills in harmful ways. We teach them how to conduct clinical exams and make home visits in villages where patients and other vulnerable individuals live, so they can experience the entire spectrum of health and its determinants. By offering simple local language lessons, our hope is to bring out the human touch through authentic and culturally sensitive interactions with our beneficiaries. To date, we have hosted 25 faculty and 56 international residents and students who have visited ACCESS for 2–6 weeks. Our goal is to offer a learning environment in which there is a respectful exchange between local staff and our visitors.

We have also had six of our faculty visit our partner institutions in the USA and Germany for 2 weeks—a length of time that is of course suboptimal, and we are presently in discussions with our collaborators to fund longer periods to allow more effective human capacity building of our team members. Given the structural and legal constraints of hosting LMIC faculty in HICs for clinical rotations, such as the fact that international healthcare workers cannot practice medicine in the United States, it may in some ways be a better use of time and resources for HIC faculty to come to LMIC sites for capacity building of human resources directly on-site at ACCESS. As such, our partners have sent faculty to teach nursing students and collaborate on curriculum building at ACCESS, as well as teach palliative care courses, implement programs for women's and children's health, and improve patient awareness of NCDs and HIV.

While reciprocal hosting of our faculty in HICs is absolutely an important metric of equity in our partnerships, it is not the only one. Our partners in HICs have invested ample financial resources in addressing the needs of our community. From the provision of laptops and learning materials to the ACCESS Nursing School to the establishment and maintenance of Grace's Promise preschool which serves the entire district, and from the construction of modern living quarters at ACCESS to covering the entire cost of travel and lodging for our faculty in HICs, our partners help us achieve goals that are set by our community, for our community.

Furthermore, part of the reciprocity in our partnerships is seen in our HIC partners connecting us to podiums on which to work collaboratively and amplify our voices, our skills, and our creativity, as well as the needs of our communities. Members of ACCESS have been hosted in the United States to speak to a greater community of donors and attract funding for initiatives, and to speak on panels at various conferences; last year, we were given the podium by our partners to speak collaboratively on a panel at the United Nations General Assembly.

The role of students

Students can be pivotal stakeholders in ensuring the sustainability and success of GH programs through a thought-provoking paradigm. On the one hand, LMIC organizations such as ACCESS are put in the position of dedicating extra time and resources to hosting and teaching visiting students and faculty, an action that inevitably involves a certain level of disruption to the local community. It is impossible to predict visitors' mindsets and behaviors, even with the most extensive participant selection, pre-departure orientation, and on-the-ground support. Bringing individuals from HICs into communities that are harmed by a continued history of the colonial mindset is an inherently vulnerable task. On the other hand, when performed with transparency, continued conversation, and intentionality, the act of inviting visitors into community life can help dispel the colonial mindset and ultimately help empower communities in LMICs, as visitors may help amplify LMIC voices on return to their home countries and thereby restructure the narrative.

That being said, it is difficult to predict what participants' takeaways from the experience will be. Our approach is two-fold: first, trying to prevent harm, and second, striving to encourage a narrative shift. Components of harm prevention have been mentioned in our summary of pre-departure training, which also includes important discussions around depictions of our community through photographs and social media use. During their stay, participants are also asked to write weekly reflections about their experiences, which are shared with the team and help us assess the ways in which any participant may be struggling and need support, while also identifying areas where a participant may need extra discussion or direction in processing their experiences through a clearer lens.

The evolution toward a narrative shift is an equally, if not more, challenging endeavor, and one that is still in progress. While our collective observations have shown us that overall, participants experience an overturning of their pre-held beliefs and return home with a meaningful appreciation for our culture, community, resources, skills, and resourcefulness—an evolution that is often apparent through participants' written reflections—we have yet to quantifiably measure this impact. Conducting a study of participants' biases and beliefs prior to and following this GH experience may be valuable, as well as more deeply and intentionally incorporating the concepts of narrative and storytelling in reflection so that participants can begin to think meaningfully about how to best represent their experience with us on their return home.

In summary, hosting students involves a careful and constantly evolving balancing act among not putting too much strain on the host community's time and resources, preventing possible harm from participants to the community, and finding creative ways of capitalizing on the notion that intentional and carefully curated experiences for HIC members in our community may help dispel long-standing myths and misconceptions. At ACCESS, we are continually in the process of seeking creative means of evolving these concepts.

A reasonable question that we believe all participants in GH exchanges should ponder is whether the hosting of international participants is ultimately of benefit to host communities—or rather, of greater benefit than putting those same resources directly into the community itself. The reality for us is that while we pride ourselves on the resources we do have and our skills in utilizing them, we are constrained in ways that are difficult to manage without the engagement of international participants. In the following section, we describe collaborative projects that helped improve the quality of life and health in our community.

Successful projects

By aligning the needs of our community with visitor's interests, we have been able to work with our partners to impact lasting change. For example, until 2016, Nakaseke lacked schooling for children under the age of five. We worked with Grace Herrick, a visiting high school student from the United States, who identified this as a key need and worked with local community members and international donors to establish Grace's Promise. This early childhood development program has graduated 230 pupils to date and has garnered support from international NGOs like ELMA Philanthropies, Segal Family Foundation, and IZUMI Foundation. It has now become a model center for early childhood development programs in Nakaseke, ensuring that children between 2 and 6 years old have a place to learn and play. Visiting students also have the opportunity to interact with children and participate in their care if it aligns with their interests. This school has played a pivotal role in the wellbeing of our community. UNICEF has noted that early childhood development programs are most beneficial for children from disadvantaged families and offer significant benefits in lowering inequalities between peers (UNICEF, 2021).

We unfortunately lacked clinics that were well-equipped to manage NCDs, which are a major threat to our community, with one in four adults having high blood pressure. To help address this epidemic, we collaborated with Charite and Heidelberg University in Germany, Nuvance Health/University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine (UVMLCOM), Johns Hopkins GH Program, Yale University, and Partners for ACCESS, all in the USA, as well as Makerere University in Uganda, to establish a center of excellence in the management of NCDs in Nakaseke. Through this collaboration, we have trained CHWs to screen for hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung diseases, and kidney diseases. Patients identified by CHWs are referred for further management to health facilities. This project has so far screened 16,000 individuals and established three NCD clinics, two of which are currently supported by the Uganda Ministry of Health. We currently provide care for 960 patients with NCDs and have several research projects focused on the prevention and management of NCDs in rural communities (Chang et al., 2019; Siddharthan et al., 2021; Tusubira et al., 2021; Moor et al., 2022). International students, residents, and faculty participate in the development of protocols, treatment guidelines, training materials, student education, research, and publication as well as patient management during their stay at ACCESS.

Among the noteworthy contributions from visiting GH students is that of a UVMLCOM team that facilitated the now highly utilized PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) project introduced to Nakaseke Hospital personnel. Another is the provision of 54 solar flashlights to rural children by an American faculty to extend their reading hours beyond the limits of daylight. CHWs and social workers who monitored the academic progress of solar torchlight recipients observed substantial improvement in the children's school performances. Working with faculty from Germany and the United States, we set up the PocketDoctor® booklet, which has been translated into the local Luganda language and used to improve patient awareness of NCDs and HIV (Siddharthan et al., 2016; Batte et al., 2021). Having been adopted by several partners, this booklet is currently being utilized in several districts in Uganda. We have collaboratively developed a patient-centered model of NCD care that involves the delivery of care to families by CHWs supported by static clinics and a mobile team of clinicians based on our community's needs.

The Women's GH team from UVMLCOM collaborated with Nakaseke community members to study the role of incentives in increasing family planning access among women of childbearing age in Nakaseke, as many women previously lacked access to prenatal care (Dougherty et al., 2018). Additionally, a group of public health students and faculty from Touro University have worked with the ACCESS team in Uganda to study youths' perceptions of the reception of family planning services by CHWs (Kalyesubula et al., 2021).

We have developed a comprehensive core curriculum delivered by ACCESS and Nakaseke Hospital staff to cater to the needs of GH students while maintaining a focus on the interests of our patients. The curriculum consists of orientation modules and modules on health systems and policy, tropical medicine, NCDs, cultural competence, clinical teaching (bedside teaching), and home visits. We believe that this curriculum with its practical sessions offers a 360-degree view of health and healthcare in rural settings.

Students are often housed on the ACCESS campus, where they interact with ACCESS staff and regularly interface with our beneficiaries. Those who intend to participate in research activities need to identify a topic of choice in collaboration with their home faculty and an in-house faculty. This ensures that all the necessary ethical approvals are obtained before research is conducted for primary data collection. We have also, on occasion, worked with students to use secondary data to address issues that have been identified by the ACCESS community members as important. We hold regular meetings with students to ensure that we address any matters arising on a day-to-day basis and also encourage students to write reflections that are often shared with the faculty. Each student receives a participatory mid-evaluation and a final evaluation as required by their primary institution. Students are further supported by their home institutions through a post-return debriefing and are encouraged to become long-term GH scholars.

Discussion: practical implications and lessons learned for future applications

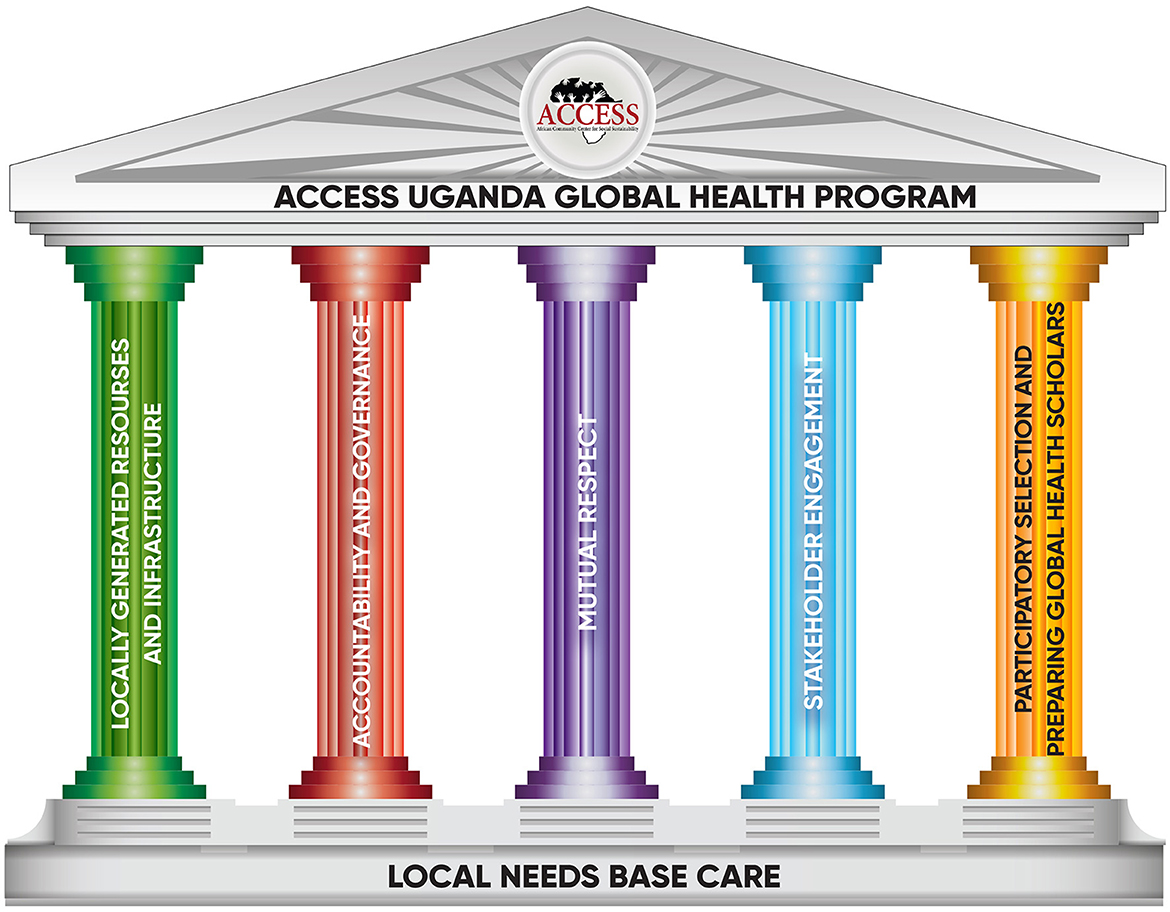

There are certain core lessons we have learned over time and rely on to run an effective GH program (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of key lessons learned through the ACCESS model of focusing on local needs for global health.

Leveraging locally generated resources and infrastructure for local needs-based care.

At ACCESS, we are clear on what our local needs are and what we bring to the table. We have used our locally generated resources to create strong physical and leadership structures. We have buildings, computers, and staff that are well-trained in our focused areas. Given that many donors do not fund infrastructure developments, we have relied heavily on our local resources until outside sources were identified. We have a unique set of patients who are often very willing to welcome learners into their communities and even their personal spaces for home visits. Our network of CHWs and other community structures is maintained by equipping them with the necessary skills to manage health, educational, and social issues in the community. We have developed a comprehensive GH curriculum that has been enriched by our partners to address the needs of both local and international institutions.

Infrastructure development presents an Achilles heel for GH programs because it is both labor- and finance-intensive. The holistic model at ACCESS embraces the areas of health, education, and economic empowerment supported by international partners (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. ACCESS holistic approach to health, education, and community empowerment. The approach is based on the community health workers who are the center bolt for all the activities that are carried out by the organization, linking international partners to the community.

We have employed various tactics to garner resources from our partners for infrastructure. The key has been stating to funders what we need upfront. For instance, the guest house for local and international students was built with support from an international partner who wanted international students to have “special accommodation.” We entered into an agreement to host their students for 5 years if they built a modern guest house, which they did (see Appendix 1).

The second approach we have utilized is encouraging international partner organizations to mobilize teams and resources to participate in setting up memorial infrastructure in our community. The first classroom block for the ACCESS Nursing School was built by a team of volunteers led by Partners for ACCESS from the United States. It now houses 40 nursing students in a boarding section (see Appendix 2).

Our third approach has been directly contacting organizations that work in building infrastructure for resource-limited settings. Our women's hospital was built with support from Construction for Change (C4C), which financed 80% of the work and sent two experts to stay with ACCESS for a year (see Appendix 3). The remaining 20% for the construction of the women's hospital was met by another partner called The Erik E. and Edith H. Bergstrom Foundation, which also funded an operational theater for family planning.

The fourth method we have utilized in building our infrastructure involves encouraging families and groups of visiting local and international students to make a difference and start chapters that support the work we do at ACCESS. In this respect, Grace's Promise was born and has spearheaded the construction of the best preschool in Nakaseke district (see Appendix 4). Last but not least, we have had the privilege of working with funders who offer unrestricted grants, which have served as a key input, to which we have added our own generated resources toward ensuring the expansion of much-needed infrastructure at ACCESS.

Accountability and governance

Our nine-member management committee, identified by district leadership, ACCESS management, and international partners, consists of experts in education, governance, finance, leadership, spirituality, and law. The committee ensures quality control, best practices, and oversight for the managing director, who leads the team on the ground. It meets on a quarterly basis and reviews and approves work plans and budgets as well as conducts onsite visits to support and supervise the teams. They also sanction and review internal and external audits, support fundraising efforts, and interact with international partners on an as-needed basis.

Mutual respect

A meaningful and sustainable collaboration should be built on mutual respect from all concerned parties. At ACCESS, we partner with faculty with whom we share values and who respect our position as much as we respect theirs. We clearly outline our roles in a mutually agreed-upon Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that guides our interactions. Each project has a local and international team leader/principal investigator. The MoU outlines the purpose of the collaboration, including mutual exchange and training of students, research, capacity-building endeavors, and building long-lasting relationships. The responsibilities of each party are outlined in terms of scientific, legal, and financial obligations. Clear guidance is detailed pertaining to managing and resolving conflicts as well as ensuring the smooth running of the collaboration. We additionally hold regular meetings with all our collaborators to evaluate the progress and attainment of goals. Meanwhile, we regularly receive feedback from visiting and local partners to ensure that we continuously maintain our commitment to each other.

Stakeholder engagement

We have established a community advisory board (CAB) consisting of various stakeholders from Nakaseke who understand the community's needs. By requiring that new collaborations and projects be reviewed and approved by the CAB and staff members, community involvement is ensured at all times. The CAB secures accountability and fulfills our commitment to the communities we serve by actively monitoring, evaluating, and giving regular feedback. We also use this opportunity to align with the requirements of the international GH curriculum of collaborating institutions.

Participatory selection and preparation of GH scholars

A key element of our education program is pre-departure engagement, which helps orient international participants and facilitates shared interests and aligned expectations. Before students are given the opportunity to complete a rotation at ACCESS, they comprehensively review our work by reviewing our website, discussing their questions with their respective institutions, and then submitting a formal application clearly outlining their interest in working with us. We then hold several virtual meetings involving the host and local faculty in which we align our expectations with those of the prospective students or faculty. Finally, we review and participate in the selection of candidates to come to ACCESS.

In order to operate effectively and ethically, it is crucial that our collaborators from HICs actively shift the paradigm from “helping” and “giving/giving back” to one of “learning” and “sharing” (Garba et al., 2021). We have co-developed several materials that are offered to prospective candidates with many previous shared experiences and ethical dilemmas and have dedicated continuous online resources that are available to all students.

We in LMICs must emphasize that our main responsibility is finding ways to change the current circumstances. Though we should not expect solutions to come from HICs, HICs can meaningfully participate in finding solutions with us. The key is to work together as a global community in addressing global issues, with LMICs claiming our power, drawing strong boundaries, being vocal about the many meaningful contributions we have to offer, and advocating for our place at the table.

Students should be oriented to issues of power, privilege, and colonial thinking prior to arriving at ACCESS so as to be primed for important concepts that will be reinforced through our own teachings and the individual experiences of the students. We make it clear to students that they are coming to our communities not to help us but to participate in our efforts to address the needs of our communities and learn from and with us. We have expertise in our own resources, challenges, and limitations and are happy to guide discussions on how to build culturally sensitive best practices.

The thinking that powers the ACCESS model is a cultural shift that needs time to be understood and processed. Here, we offer a robust first step. Through the give-and-take of reciprocal learning, we have gained important insights into what a true GH paradigm should look like. We take pride in how we have incorporated multicultural, multifaceted ideals into our thinking, our teachings, and our shared materials. Ours is a model of healthcare delivery that prioritizes the use of indigenous resources and community know-how, together with input from outside partners, to create a culturally sensitive best-practice model. At ACCESS, our holistic approach to healthcare truly addresses the varied needs of an individual in a way that fits and reflects their environment. We believe that this represents a true GH model and is one that can be emulated by HICs and LMICs alike.

Conceptual and methodological constraints

Most organizations in LMICs are likely to face certain general challenges. First, the reality is that hosting and properly engaging visitors, including providing meaningful orientation, can exhaust a talented health workforce beyond its limits. Second, promoting human values, respect, and dignity while participating in bedside teaching for trainees can be difficult to navigate. Extra resources, such as translators, are required to support GH elective students in their interactions with patients and communities. Third, it can be challenging to identify and train a core group of faculty that is familiar with the GH curriculum to optimally supervise medical students from HICs. These faculty members should ideally support students in gaining a sociocultural, political, and historical understanding of their host institution and country. Finally, acquiring infrastructure and resources for GH elective students is also challenging. We have clinical material, but capacity building of faculty in GH research and education as well as the creation and institutionalization of a mentorship model for faculty and students are needed.

Specific challenges we have faced at ACCESS include disagreements with donors on the management of the program, for instance, when a donor wanted to replace a key manager in our program with occasional visitors who were poorly prepared to live in a rural setting. We have learned from these experiences to strengthen our program.

We have also encountered visitors who arrive with incorrect, unclear, or ambiguous expectations that are not aligned with our program. A few have come with a sense of entitlement and/or arrogance, which can manifest as non-adherence to local authorities, regulations, and customs. Many students arrive with expectations of practicing evidence-based medicine rooted in evidence created in another country without considering the local context. This often happens in the first weeks of the rotation but is ameliorated as students and faculty become more aware of the realities of LMICs and adjust their expectations and thought processes accordingly.

We have also faced several ethical dilemmas, particularly related to end-of-life issues. For such occurrences, we have trained our faculty to play a supportive role as students navigate these challenging times, which are quite different from what they see in their home countries.

The cost of medical services and the allocation of resources are another issue that is often challenging. Whereas, most healthcare services in government hospitals in Uganda are purportedly free, limited availability creates hidden costs for patients. This often creates inequality between the haves and have-nots, even when attending the same hospital. When investigations and drugs are prescribed for patients by the healthcare team, those who can afford them (often from outside the hospital) improve, while those who cannot afford them remain in the wards for longer periods and, at times, die. Thus, in managing patients, the clinician must always be on the lookout to ensure that whatever s/he prescribes to the patient is available or within reach of the patient's financial means. This skill, which is acquired over a period of many years, often proves to be of great distress to international students and faculty. We have tried to address this issue by ensuring that a local faculty member supports the visiting team in such instances, including the exploration of alternatives to care.

Other challenges relate to LMIC colleagues visiting HIC centers and are not the major discussion of this manuscript.

Conclusion

ACCESS Uganda has established a grassroots GH model that has successfully leveraged HIC partners to collaboratively address key challenges that have been prioritized by the people of Nakaseke. Through principles of mutual respect, community engagement, and proper governance, ACCESS has been able to work with international and local partners to ensure an enriching GH experience that addresses the needs of rural communities within Uganda. ACCESS has empowered its community as well as the growth of individuals around the world.

We believe that a pivotal component of our success is rooted in long-term friendship and trust-building among a group of people who believe in the main core values of GH. Gradually, these individuals grew into leadership roles in which they had decision-making power and came together toward this important vision of bringing justice to marginalized communities as part of restructuring GH education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RK and MiS made the first draft. BO, RM, IW, EK, JS, JL, and MaS extensively reviewed and made substantial contributions to the manuscript. All authors approved the publication of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the ACCESS Board of Directors and the community advisory board for their continuous support and input. We appreciate the local and international partners that have made ACCESS a great example of global health. We thank Professor Asghar Rastegar for his great input and reflections on this work as well as his mentorship in the development of the ACCESS model. We appreciate Amanda Wallace for working on the illustrations. Helmut Kraus is credited for Figure 3 in the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1214743/full#supplementary-material

References

Batte, C., Mukisa, J., Rykiel, N., Mukunya, D., Checkley, W., Knauf, F., et al. (2021). Acceptability of patient-centered hypertension education delivered by community health workers among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. BMC Pub. Health 21, 1343. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11411-6

Bishop, R., and Litch, J. A. (2000). Medical tourism can do harm. BMJ 320, 1017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.1017

Chang, H., Hawley, N. L., Kalyesubula, R., Siddharthan, T., Checkley, W., Knauf, F., et al. (2019). Challenges to hypertension and diabetes management in rural Uganda: a qualitative study with patients, village health team members, and health care professionals. Int. J. Equity Health 18, 38. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0934-1

Dougherty, A., Kayongo, A., Deans, S., Mundaka, J., Nassali, F., Sewanyana, J., et al. (2018). Knowledge and use of family planning among men in rural Uganda. BMC Pub. Health 18, 1294. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6173-3

Garba, D. L., Stankey, M. C., Jayaram, A., and Hedt-Gauthier, B. L. (2021). How do we decolonize global health in medical education? Ann. Glob. Health 87, 29. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3220

Kalyesubula, R., Pardo, J. M., Yeh, S., Munana, R., Weswa, I., Adducci, J., et al. (2021). Youths' perceptions of community health workers' delivery of family planning services: a cross-sectional, mixed-methods study in Nakaseke District, Uganda. BMC Pub. Health 21, 666. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10695-y

Koplan, J. P., Bond, T. C., Merson, M. H., Reddy, K. S., Rodriguez, M. H., Sewankambo, N. K., et al. (2009). Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 373, 1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

Kruk, M. E., Gage, A. D., Arsenault, C., Jordan, K., and Leslie, H. H. (2018). High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e1196–e252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

Lu, P. M., Mansour, R., Qiu, M. K., Biraro, I. A., and Rabin, T. L. (2021). Low- and middle-income country host perceptions of short-term experiences in global health: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 96, 460–469.

Moor, S. E., Tusubira, A. K., Wood, D., Akiteng, A. R., Galusha, D., Tessier-Sherman, B., et al. (2022). Patient preferences for facility-based management of hypertension and diabetes in rural Uganda: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open 12, e059949. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059949

Sadigh, M., Sarfeh, J., and Kalyesubula, R. (2017). The retention of ACCESS nursing assistant graduates in rural Uganda. J. Nurs. Educ. Prac. 8, 94. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v8n1p94

Siddharthan, T., Kalyesubula, R., Morgan, B., Ermer, T., Rabin, T. L., Kayongo, A., et al. (2021). The rural Uganda non-communicable disease (RUNCD) study: prevalence and risk factors of self-reported NCDs from a cross sectional survey. BMC Pub. Health 21, 2036. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12123-7

Siddharthan, T., Rabin, T., Canavan, M. E., Nassali, F., Kirchhoff, P., Kalyesubula, R., et al. (2016). Implementation of patient-centered education for chronic-disease management in Uganda: an effectiveness study. PLoS ONE 11, e0166411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166411

Tusubira, A. K., Nalwadda, C. K., Akiteng, A. R., Hsieh, E., Ngaruiya, C., Rabin, T. L., et al. (2021). Social support for self-care: patient strategies for managing diabetes and hypertension in rural Uganda. Ann. Glob. Health 87, 86. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3308

UNICEF (2021). Early Childhood Development UNICEF and Health. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/serbia/en/early-childhood-development-and-health (accessed April 28, 2023).

Keywords: global health education, ACCESS-Uganda model, decolonization, infrastructure, learning

Citation: Kalyesubula R, Sadigh M, Okong B, Munana R, Weswa I, Katali EA, Sewanyana J, Levine J and Sadigh M (2023) ACCESS model: a step toward an empowerment model in global health education. Front. Educ. 8:1214743. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1214743

Received: 30 April 2023; Accepted: 25 August 2023;

Published: 20 September 2023.

Edited by:

Ashti A. Doobay-Persaud, Northwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

María Teresa De La Garza Carranza, Tecnológico Nacional de México, MexicoAnna Kalbarczyk, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Kalyesubula, Sadigh, Okong, Munana, Weswa, Katali, Sewanyana, Levine and Sadigh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert Kalyesubula, cmthbHllc3VidWxhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Robert Kalyesubula

Robert Kalyesubula Mitra Sadigh

Mitra Sadigh Bernard Okong5

Bernard Okong5