- Science News

- Frontiers news

- Eliza Stott – Wrangling wombats and connecting women in wildlife

Eliza Stott – Wrangling wombats and connecting women in wildlife

Authors: Emma Phipps and Kate Brown

In honor of World Wildlife Day, we spoke to Eliza Stott, a PhD student at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Eliza gave us an insight into how she juggles studying for a PhD and working as a wildlife ranger with her role as founder and director of Women in Wildlife, an organization which connects women and non-binary persons within the wildlife industry around the world. She also shared her thoughts on this year’s World Wildlife Day theme of ‘Wildlife Conservation Finance’ from the perspective of an Australian conservation scientist.

Eliza Stott is currently a PhD student with the One Health Research Group at the University of Melbourne where, as a self-described ‘wombat wrangler,’ she is investigating the treatment of sarcoptic mange in this native Australian mammal. Wombats are medium-sized marsupials that are disproportionately affected by sarcoptic mange, a highly contagious skin disease which Eliza notes is “both an animal welfare and conservation issue,” and ultimately leads to death if left untreated.

“The treatment isn’t well-structured at the moment and there’s not a lot of scientific data to support current treatment regimens for one of the two treatment drugs. The wombats are mostly treated by amazing volunteers who are passionate about the cause,” she says.

Eliza’s PhD looks at moxidectin, the active ingredient of the drug Cydectin, which is currently used to treat sarcoptic mange, but is understudied in the treatment of the disease in wombats. Her initial focus was on the pharmacokinetics of the drug, which she describes as “how the drug is absorbed, metabolized, and excreted from the body.” Eliza is now collecting data on field treatment success in infected wombats at different stages of the disease.

“I’m taking data looking at spatial dynamics, how it affects their behavior and home ranges, as well as diagnostic data including skin biopsies, blood, and skin scrapes,” she explains. Her work is hugely important in better understanding a disease which is one of the biggest threats to wombats.

A community for women in wildlife

Eliza is the founder and director of Women in Wildlife – a support network dedicated to amplifying and connecting women and non-binary persons in the wildlife industry worldwide. Eliza recalls how during her time at university, gender inequality within the industry was first made apparent to her. It’s during this time that she read American biologist Dr Wendy Anderson’s paper The changing face of the wildlife profession: tools for creating women leaders.

“The paper discussed three barriers that women working in the wildlife industry are facing. One barrier is the lack of flexible working hours, the second is a lack of opportunities for career development, and the third barrier is a lack of female support networks.”

Inspired by Anderson's paper, Eliza was compelled to create her own community of women to team up and support each other. She explains that when she began her journey in the wildlife industry, she didn’t understand what the different career paths were and couldn’t find a resource where this information was communicated effectively. “I remember sending Instagram messages asking people – ‘how did you get this job?!’ I had no idea how to get there.”

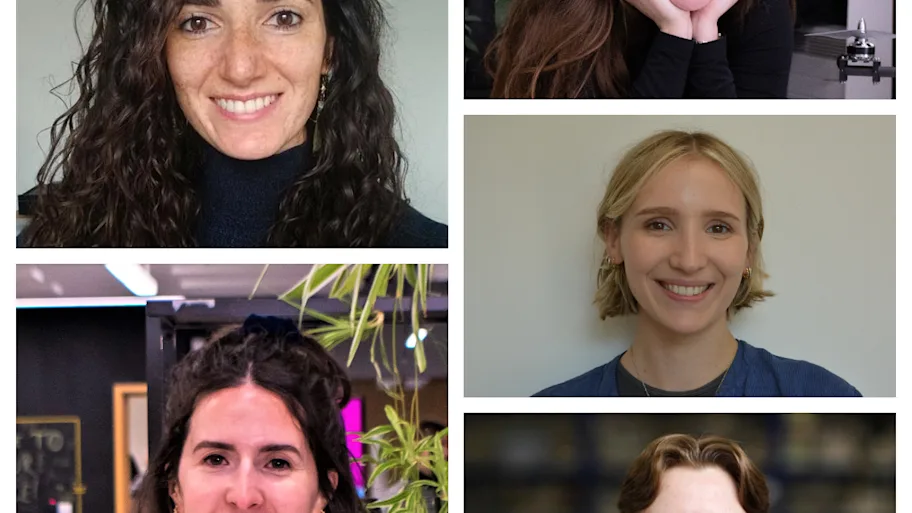

Since its establishment in 2021, Women in Wildlife has “snowballed” according to Eliza, with a team of nearly 20 women from across the globe and a plethora of resources and activities. The initiative started as an Instagram account highlighting and interviewing women in the field, and it was incredibly well received. Those interested are still able to submit a request to feature on the Instagram page, and there is a bimonthly newsletter which delves deeper into the profiles of women in the field.

Today, the group operates a membership program where members have access to their mentorship scheme. They organize webinars and workshops, which vary in setup and content, with resumé writing and photography among the skills covered. The team even organize eco-trips and volunteer trips. “It has blossomed into something quite special,” Eliza comments. Furthermore, the team runs an education program where they present the different career paths available and cover important topics in the industry, such as eco-anxiety.

With regards to Eliza’s own career, alongside her PhD research and director role for Women in Wildlife, she is also a wildlife ranger for Phillip Island Nature Parks near her home on Phillip Island (Millowl). The parks constitute a not-for-profit conservation organization which works “both in the marine and terrestrial space of reintroductions for threatened species.” We discussed what a week in Eliza’s life tends to look like balancing her different commitments, which can often include night-time fieldwork, long days in the lab, and weekends working in conservation.

“Fieldwork for my PhD is quite crazy and is often at night. I try and juggle Women in Wildlife work between that and my actual job, so during fieldwork season there’s unfortunately not much work-life balance. When I’m not in the field, I can generally work from home three days a week and this is when I can really invest time in Women in Wildlife and my PhD, whether it’s project management or writing up papers.

“Longer term, I would like to create scholarships for women to experience fieldwork, or to attend university and study wildlife in more remote places, as well as support more women-led conservation organizations too,” Eliza continues. The success of Eliza’s group highlights the need for such spaces within the community.

Funding restoration and managing destruction

March 3rd is the designated UN World Wildlife Day and this year’s theme is “'Wildlife Conservation Finance: Investing in People and Planet.” The UN is encouraging scientists and the public alike to join them in exploring how we can work together to “finance wildlife conservation more effectively,” while sustainably building a resilient future for people and the planet.

The first thing that came to Eliza’s mind when she saw this year’s subject matter was a study led by Griffith University, published earlier this year. “The study estimated that it was going to take 15 billion dollars per year for 30 years to repair the threat to Australia’s 99 priority species,” Eliza summarizes. “This is a huge figure, and that’s just how much it would cost if we stopped the destruction right now. In the last few decades, more than 7 million hectares of habitat has been destroyed, mostly for mining and agriculture, so conservation organizations here are always chasing their tails for funding opportunities.”

Eliza pointed out that in addition to the need for conservation to be funded thoroughly, it needs to be coupled with legislative changes and a huge reduction in the destruction of natural habitat. “It’s difficult, in Australia we see restoration being funded right next door to the destruction. For example, the country invested in the conservation of koalas after the bush fires in 2019/2020, which has allowed funding into fantastic projects and koala causes, however the destruction still continues and causes significant damage to their habitat.”

In Australia, teams often see discrepancies in conservation funding depending on species. “I feel lucky with my work on wombats and mange, as mange is a horrific disease that people can visually see,” Eliza comments.

Many threatened species aren’t ‘iconic’ or ‘charismatic,’ and some you wouldn’t be able to see most of the time, so their plights are not widely understood by the general population. We learned that even though mammals such as wombats tend to receive higher levels of conservation funding in general when compared to other classes, Australia is the world leader in mammal extinctions.

Our conversation moved onto the influence of the public in helping wildlife in need. No matter where you live, understanding the needs of your local wildlife can mean the difference between life and death for many animals. In Australia, for example, there are many marsupials, including wombats, kangaroos, and koalas, all of whom carry their young in pouches. Unfortunately, wildlife-vehicle collisions are prevalent not just in Australia, but all around the world, with an estimated 10 million animals hit on Australian roads every year. For marsupials specifically, Eliza highlighted the need to check the pouches of injured or dead adults for young who are often still alive, and to “carry a basic kit in your car with towels, scissors, and materials to make a pouch. If you find injured wildlife, it is important to call your local wildlife rescue.”

For wombats, Eliza notes that each Australian state has a slightly different approach to sarcoptic mange management. In her home state of Victoria, locals can report diseased animals or volunteer to administer medicine to wombats through Mange Management, a group that distributes free mange treatment kits. “Having a number saved in your phone beforehand helps so you know who to call immediately,” Eliza advises, a tip which can be useful wherever one lives.

Ultimately, reducing habitat destruction is the priority for wildlife in Australia, and the public can influence this, too. “Habitat destruction is so ingrained in our governmental policies, so who we vote for in upcoming elections matters. Ensuring that we vote for people who have kinder, less destructive policies when considering mining and agriculture will help,” Eliza summarizes.

Frontiers is a signatory of the United Nations Publishers Compact. This interview has been published in support of United Nations Sustainability Development Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls and United Nations Sustainability Development Goal 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.