- Science news

- Environment

- Trees could be spying on illegal gold mining operations in the Amazon rainforest

Trees could be spying on illegal gold mining operations in the Amazon rainforest

In the Amazon, gold mining is a thriving business, pushing deep into the rainforest and indigenous lands. Small-scale operations set up primarily illicitly and operated in the shadows use mercury, a substance with neurotoxic properties, for gold extraction. Now, a team of researchers examined if trees native to the Peruvian Amazon could be used as biomonitors for gold mining activities. By examining mercury concentrations in tree rings, they concluded that some species could bear witness to illegal mining activities.

For hundreds of years, the Amazon has been exploited for its gold. Today, the precious metal is just as sought after, but the remaining tiny gold particles are much harder to find. Mining often happens in artisanal and small-scale mining operations that release mercury (Hg) into the air, polluting the environment and harming human health.

An international team of researchers has now examined tree rings of species native to the Peruvian Amazon to determine if trees could be used to show approximately where and when atmospheric mercury was released.

“We show that Ficus insipda tree cores can be used as a biomonitor for characterizing the spatial and potentially the temporal footprint of mercury emissions from artisanal gold mining in the neotropics,” said Dr Jacqueline Gerson, an assistant professor in biological and environmental engineering at Cornell University and first author of the study published in Frontiers in Environmental Science. “Trees can provide a widespread and fairly cheap network of biomonitoring, by archiving a record of mercury concentration within tree bolewood.”

Mercury is in the air

For gold extraction, miners add mercury to the soil that contains tiny gold particles. Mercury binds to the gold particles which creates amalgams. Amalgams have a much lower melting point than gold so to extract it, the amalgams are burned. This process releases gaseous mercury into the atmosphere.

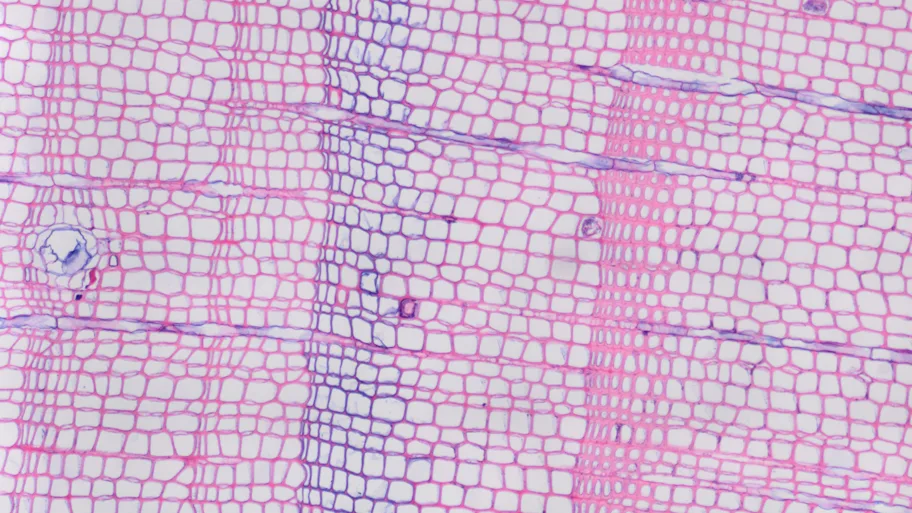

Three neotropical tree species with previously documented annual tree rings were examined to test their potential as biomonitors: Wild figs (Ficus insipida), a common tree in the neotropics, Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa), and tornillos (Cedrelinga catenaformis). Due to the equitable year-round climate in the neotropics, not all trees form rings, and of the examined species, only F. insipida exhibited them. Tree cores samples were collected at two sites far from mining activity and three sites within five kilometers to mining towns where amalgams are frequently burned. One of the mining sites was next to protected forest.

“There are many variables that drive individual tree Hg concentrations, and it is difficult to determine the specific drivers,” Gerson explained. “The trees in the study were all the same species and from the same sites, exposed to the same atmospheric Hg concentration. That is why we sample multiple trees and then use average values.”

Mercury concentrations in bolewood were highest at the two sampling sites close to mining activity and lower at the mining-impacted site adjacent to protected forest and the sites far from mining towns. “Higher atmospheric Hg concentrations are generally associated with nearby mining locations,” Gerson explained. “In the Peruvian Amazon, where mining is the main source of Hg, the association between higher Hg concentrations and proximity to a mining site can readily be drawn.”

Especially after 2000, Hg concentrations near towns rose where mercury-gold amalgams were burned. “This is likely due to the expansion of gold mining activities around this time,” Gerson said.

Download and read original article

A network of spies

While the study proved that trees can be used as a biomonitoring network for gaseous mercury emissions, the study has some limitations. Most notably, the exact distance to mining towns was unknown due to the illegal nature of these operations. This likely influenced the concentrations of Hg found in the trunk wood.

“Ficus insipida can be used as a cheap and powerful tool to examine large spatial trends in Hg emissions in the neotropics,” Gerson concluded. “Using bolewood could allow for regional monitoring efforts.” This is particularly important in relation to the UN Minamata Convention on Mercury, an international treaty which aims to reduce mercury and mercury compound emissions and mitigate health and environmental risks.

REPUBLISHING GUIDELINES: Open access and sharing research is part of Frontiers’ mission. Unless otherwise noted, you can republish articles posted in the Frontiers news site — as long as you include a link back to the original research. Selling the articles is not allowed.