- School of Economics and Management, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

Introduction: Poverty eradication is the primary goal of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs). Despite China’s significant achievements in poverty alleviation, many rural households still struggle to maintain a sustainable livelihood may even slip back into poverty due to ineffective risk responses when facing risks and challenges.

Methods: This study employs data from the 2017–2019 China Household Finance Survey to theoretically and empirically examine the impact and mechanisms of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households.

Results: The study’s results indicate that digital payments significantly reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households, a finding that remains robust even after accounting for endogeneity, employing alternative variable measurement approaches, and conducting propensity score matching tests. Mechanism analysis suggest that encouraging rural households to hold commercial insurance, engage in non-farm employment and expand their family social networks are key pathways by which digital payments impact the financial vulnerability of rural households. Further heterogeneity analyses reveal that digital payment plays a more substantial role in mitigating the financial vulnerability of rural households in the western region, which have low financial assets and high health risks, compared to those in the central and eastern regions, which have high financial assets and low health risks.

Discussion: Therefore, this paper suggests that the government should continue to promote the in-depth integration of digital technology and financial services, strengthen the construction of rural digital infrastructure in areas lagging behind in traditional finance, enhance the comprehensive service function of digital payments, and enrich the coping strategies of farmers to mitigate financial vulnerability, while remaining vigilant about the potential consequences of digital payment.

1 Introduction

Preventing and mitigating household financial risks is crucial not only for enhancing the welfare of households, but also for maintaining financial stability and sustainable development across all countries (Li et al., 2022). In 2020, China achieved a comprehensive victory in poverty eradication, offing valuable experience for developing countries worldwide in their efforts to eradicate poverty (Chen and Ravallion, 2021). However, in the context of risk normalization, households may still have to face uncertainties such as economic changes, employment adjustments, natural disasters, major illnesses, weddings and funerals, exposing them to many trials (Closset et al., 2015; Mabhuye, 2024). Numerous studies have demonstrated that rural households have lower affordability compared to those in urban areas. China’s dual economic structure has particularly exacerbated the significant imbalance of financial resources between urban and rural areas, a situation that is typical in a global context. Although this problem has been improving annually, it still presents substantial challenges (Yu, 2023). Traditional finance in rural areas has high transaction costs and information asymmetry (Duca and Rosenthal, 1993), which leaves rural households facing serious financial exclusion, lacking effective risk management and coping tools (Savari et al., 2024). Consequently, they find it difficult to rely on limited precautionary savings to withstand risks from internal and external shocks. This vulnerability makes them highly susceptible to falling into a state of vulnerability, potentially leading to a return to poverty (Stampini et al., 2016; Li et al., 2022). Household financial vulnerability (HFV), which refers to the likelihood that a household will experience financial distress due to its inability to meet incurred debts in a timely or complete manner (Leika and Marchettini, 2017), is an important indicator of financial risk within the household sector and has garnered extensive attention from academics. According to the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) data, rural financially vulnerable households account for a much higher proportion than urban households, still showing an upward trend (Hu and Wang, 2024). Therefore, how to improve the ability of rural households to cope with risks and alleviate the financial vulnerability of rural households has become an urgent research topic.

In recent years, the increasing improvement of digital infrastructure has led to the rapid spread of digital payment in China, profoundly impacting people’s daily lives. The rising trend in digital payment usage has been further accelerated by the COVID-19 (Liu and Dewitte, 2021). By June 2022, there were over 904 million digital payment users in China, and 77.5% of mobile phone users utilized digital payment every day. By the end of 2022, the number of bank digital payment transactions reached 1024.181 billion, with a cumulative transaction amount of 337.87 trillion. Digital payment adoption in rural households began later, but it is also developing rapidly. According to data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), the digital payment usage rate in rural areas was 29.36% in 2019, up 161.21% from 2017. Numerous studies have found that digital technology has spurred the development of financial inclusion and created new opportunities to reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households (Marshall et al., 2020). In addition to providing users with real-time money transfer capabilities, digital payment platforms also enable financial services such as savings, loans, asset management and investments anytime, anywhere. This lowers the thresholds and costs for individuals or households to participate in the financial market, thereby increasing financial accessibility (Afawubo et al., 2020). For example, it can help households to access credit support and overcome financing constraints (Deng and Qian, 2024), remove liquidity constraints and smooth the negative impact of risk shocks. Secondly, digital payment provides diversified ways of social interaction, such as WeChat and Alipay, among others. This new form of social interaction extends beyond the traditional family unit, offering a cost-effective method of maintaining the social network among family members (Yin et al., 2019). It has been demonstrated that this enhances the self-insurance mechanism of the family and reduces the risk shock. Finally, digital payment affords a channel that enables timely access to various financial information. Residents can obtain early warning information about various risks on digital payment platforms without leaving their homes, allowing them to make timely and appropriate risk response measures and reduce the losses caused by these risks. It can be observed that digital payment has a significant universal impact and is closely related to the financial vulnerability of rural households. Therefore, can digital payment effectively mitigate the financial vulnerability of rural households?

This paper examines the impact of digital payments on the household financial vulnerability of rural households from the perspective of micro-farmers. This exploration is based on existing studies and the fact that digital payments are rapidly evolving. The paper also utilizes tracked micro-research data from 2017 to 2019 to analyze the financial vulnerability of rural households. The marginal contribution of this paper consists of three main aspects. Firstly, it examines the mitigating effect on rural household financial vulnerability from the perspective of digital payments, providing new research ideas for mitigating rural household financial vulnerability. Secondly, from the perspective of farmers’ ability to cope with various risks, the mechanism by which digital payments affect farmers’ financial vulnerability was explored, providing theoretical reference for financial technology to assist in alleviating farmers’ financial vulnerability. Thirdly, the study goes on to explore the heterogeneity of digital payments affecting rural household financial vulnerability across different regions, household assets and health risks. This provides empirical support for the differentiated promotion of digital payments and mitigation of rural household financial vulnerability.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review. Section 3 presents theoretical analysis. Section 4 presents empirical research design, including the model, variables and data sources. Section 5 presents the findings and tests. Section 6 presents the heterogeneity analysis. Section 7 presents the test of the mechanism of action. Finally, Section 8 presents the conclusions and policy recommendations.

2 Literature review

The existing research on household financial vulnerability primarily concentrates on the following four aspects. Firstly, from the perspective of family population and economic characteristics, an increase in the proportion of young or elderly household members increases both the time spent on household care, crowds out household labor supply and reducing household income. It also increases the uncertainty of healthcare expenditures, which affects household risk exposure (Lusardi et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2024). An increase in household debt leverage can also exacerbate household financial vulnerability (Martín-Legendre and Sánchez-Santos, 2024). Secondly, from the contextual risk level, since health cannot be allocated through savings and intertemporal allocation, health risk can directly worsen household financial status, generate larger unanticipated expenditures, and increase household financial vulnerability (Zhou and Yang, 2024). In addition, climate risk can lead to increased uncertainty in agricultural production, reducing the stability of farm household incomes and raising rural household financial vulnerability (Carleton and Hsiang, 2016). Thirdly, from the risk response level. Early scholars have mostly focused on the impact of financial literacy on household financial vulnerability. Financial literacy enhancement can improve the efficiency of household risk identification, prevention and response, help households make correct financial decisions, and alleviate household financial vulnerability (Lusardi and Tufano, 2015; Abdullah, 2019; Chen et al., 2024). In recent years, scholars’ research perspectives have become more diverse. For example, from the individual’s intergenerational educational mobility (Ma and Ma, 2024), employment industry and status (Ali et al., 2020), cognitive and non-cognitive abilities (Kleimeier et al., 2023), and so on.

Scholars generally believe that the development of digital finance has the potential to alleviate household financial fragility (Li et al., 2022). For instance, Liu et al. (2024) discovered that digital financial development significantly reduces household financial vulnerability by enhancing financial literacy, diversifying income sources, and facilitating the acquisition of commercial insurance, particularly in rural areas and among low-income households. The impact is more pronounced in these contexts. Furthermore, Wang and Fu (2021) found that digital financial development reduces the poverty vulnerability of rural households. Furthermore, Hu et al. (2024) found that digital payments significantly increase the level of resilience to poverty eradication and development. Conversely, some scholars posit that digital finance can exacerbate household financial vulnerability. For instance, Zhang and Zhao (2024) demonstrate that digital payments can precipitate overconsumption by households, culminating in an escalation in household debt and eventual default on credit card debt. Furthermore, the impact of digital payments on vulnerability is found to be heterogeneous. For instance, Afawubo et al. (2020) demonstrate that digital payments enhance households’ capacity to cope during emergencies, ultimately leading to poverty alleviation. However, the study also found that digital payments increased the vulnerability of certain groups, such as rural dwellers, women, and those with limited education and income.

In summary, most existing literature focuses on the impact of household financial vulnerability from the perspectives of household population and economic characteristics, background risks, and risk response. Some literature also studies the impact of digital finance development on household financial vulnerability. However, there is still room for improvement. Firstly, much of the existing literature has examined the impact of fintech development on household financial vulnerability at the macro level, but the conclusions remain controversial. Few studies have been conducted in the literature from a micro-fintech perspective. Secondly, while existing studies have focused only on the impact of fintech on a single dimension, such as household indebtedness or liquidity constraints, there is little literature that explores the impact and mechanisms of fintech on the overall financial situation of rural households. Finally, digital payment has been identified as the most prevalent digital financial instrument among rural households (Huang et al., 2025), and research focusing on its impact can provide a more precise reflection of the influence of fintech. Therefore, this paper examines the impact and mechanism of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households with the help of micro research data.

3 Theoretical analysis

Theoretically, household financial vulnerability is determined by two primary components: the intensity of the risk to which the household is exposed, and the capacity to manage that risk. Risk serves as the causative factor, while inadequate capacity to cope with risk constitutes the essence of vulnerability (ISDR, 2004). If individuals have well-developed risk coping mechanisms, they will not fall into financial vulnerability in the face of greater risks. Numerous studies and experiences have confirmed that the financial system serves to smooth risks and enhance risk management capabilities (Urrea and Maldonado, 2011). However, China’s rural financial market is imperfect, there is serious financial exclusion, making it difficult for farmers to use financial instruments to protect themselves against risky shocks. As an important manifestation of digital finance, digital payment provides rural residents with better-matched financial services and risk management tools such as deposits, payments, credit, wealth management, by virtue of its simple of operation, convenient of transactions, and low cost. In addition, digital payments have empowered the inclusive effects of traditional finance, alleviated financial exclusion and promoted the development of financial intermediation, and have become an important means of reducing the threshold of rural financial services and enhancing the ability of rural households to manage uncertain risks.

3.1 The direct impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households

Digital payments can expand the service boundaries of inclusive finance, enhance the financial accessibility of rural households, further promote the inclusive development of rural finance due to their low transaction thresholds, high efficiency and rapid access to information, and impact the financial vulnerability of rural households. Primarily, digital payments have the potential to lower the financial access barrier for rural households. The utilization of big data, cloud computing, and other information technologies facilitates the creation of a comprehensive profile of farmers’ creditworthiness, based on their daily income and expenditure records. This enhances the efficiency of credit assessment, reduces the access threshold to credit for farmers, and mitigates the liquidity constraints they face when confronted with risks (Dong, 2024). Secondly, digital payment reduces the transaction cost for farmers when obtaining financial products and services. Digital payments can transcend the limitations of time and space, providing farmers with a lower threshold, more comprehensive, and better-matched capital financing, investment and financial management, as well as commercial insurance and other risk-avoidance tools, thereby alleviating the financial vulnerability of farmers’ households. Finally, digital payment facilitates more convenient exchange of information, thereby reducing information asymmetry. Digital payment broadens the channels through which farmers can obtain information. It also enhances their ability to understand financial concepts and products, perceive risks, and manage financial risks, thereby improving their level of financial literacy. This, in turn, alleviates household financial vulnerability (Liu et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024). The research hypothesis H1 of this paper is thus proposed:

H1: The use of digital payments can help alleviate the financial vulnerability of rural households.

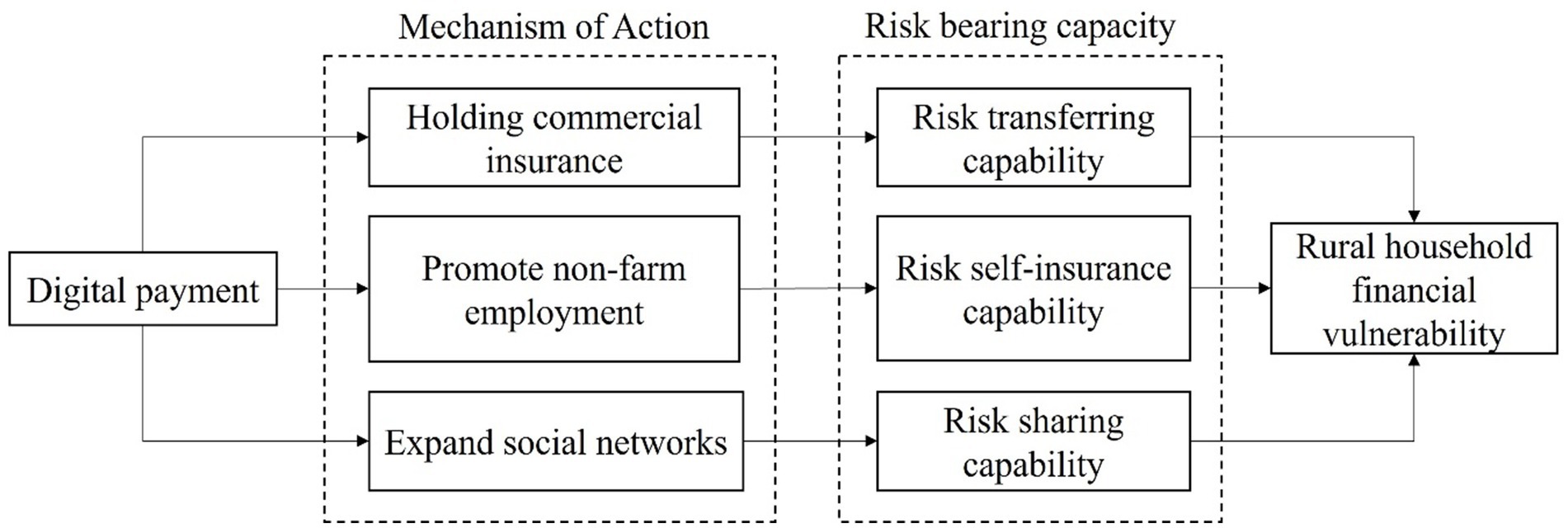

3.2 The indirect impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households

The capacity to take risks is closely related to the financial vulnerability of rural households. Risk-taking capacity is defined as an individual’s ability to address their own risks by enacting various measures, such as self-insurance and risk transfer, aimed at mitigating losses and ensuring the stability of their production and livelihood (Wan et al., 2023; Rodríguez-Barillas et al., 2024). The sustainable livelihoods theory suggests that individual strategies for coping with risk play a crucial role in counteracting and mitigating the negative impacts of risk shocks on livelihood vulnerability (Su et al., 2016; Sargani et al., 2023). Farm households utilize trade-offs, combinations, feedback mechanisms and adjustments through risk transfer, risk self-insurance and risk sharing to create a household risk management portfolio, thereby enabling them to withstand the impact of risk event shocks. The present study will explore the roles of risk-taking capacity in the impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households, respectively, in accordance with the coping risk behaviors of farmers. The risk-taking capacity of farmers can be classified into three categories: risk transfer capacity, risk self-insurance capacity, and risk sharing capacity.

Firstly, digital payments enhance the capacity for risk transfer and reduce household financial vulnerability by enabling the participation of rural households in commercial insurance. Transferring and dispersing risk is the primary reason why people hold insurance (Knight, 1921). With the acceleration of the digitalization process, digital payment systems integrates Internet technology with the insurance industry, providing low-threshold and low-cost commercial insurance services for financially excluded rural residents. Digital payment alters the traditional commercial insurance sales model, overcomes the time and space constraints of holding insurance through online platforms, significantly reduces transaction costs, and enhances the accessibility of family commercial insurance. Moreover, with the aid of big data, cloud computing and other technologies, digital payment uses the daily income and expenditure records of farmers as the credit basis to offer multi-level commercial insurance products. This approach aligns with the risk protection needs of rural families. It not only reduces the information search costs associated with commercial insurance for rural households but also addresses the issues of adverse selection and moral hazard for insurance institutions. This is beneficial for the development of insurance products that better cater to the needs of rural households (Huang et al., 2020).

Secondly, digital payments can reduce household financial vulnerability by promoting off-farm employment and enhancing self-insurance against risk. It has been found that diversifying income sources and achieving sustained income growth through non-farm employment is one of the most important means of reducing the vulnerability of farm households (Zhao et al., 2024), and it can improve their ability to protect themselves against risk. Digital payments provide more opportunities for farmers and increase livelihood options. Digital payments promote entrepreneurship by reducing start-up costs and credit constraints (Yin et al., 2019), and while boosting economic development, they also give rise to new forms and modes of employment, such as takeaway workers, couriers, and Taobao shops, which create new non-farming employment opportunities for rural laborers (Beck et al., 2018). Moreover, the credit information display function of digital payment can reduce the information asymmetry between the supply and demand sides of the labor market, improve the match between jobs and income, and alleviate the structural unemployment problem.

Thirdly, digital payments can enhance the risk-sharing capacity and mitigate household financial vulnerability by expanding the social network of rural households. China’s rural society is a typical ‘acquaintance society’, and ‘acquaintance lending’ has become an important way of risk sharing for rural households through social networks linked by blood, kinship and geography (Fei et al., 1992), and the risk sharing capacity of social networks has always been the key to the resilience of rural households to risks and the reduction of financial vulnerability (Fafchamps and Gubert, 2007; Alger and Weibull, 2010). Digital payments provide rural households with a wider range of social interaction channels, expanding the scope of social interactions, and also providing conditions for mutual support among family members and enhancing household risk-sharing capacity. Digital payment expands the scope of social networks and credit resources through the information interaction function of payment platforms such as WeChat and Alipay, thereby enhancing the acquisition of risk information and the function of risk sharing from external social networks. Moreover, the convenience of digital payment tools significantly reduces the time and cost of borrowing and lending, which helps to quickly utilize the risk-sharing network to mitigate the impact of external shocks on the household economy (Hong et al., 2020). In summary, this paper proposes research hypothesis H2:

H2: Digital payments reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households by encouraging farmers to hold commercial insurance.

H3: Digital payments reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households by promoting non-farm employment for farmers.

H4: Digital payments reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households by expanding their social networks.

Based on the above theoretical analysis, this article will verify the feasibility of the above hypotheses through empirical research (Figure 1).

4 Research design

4.1 Model construction

Firstly, to examine the impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households, We constructed the following model for Equation 1:

where is the financial vulnerability of rural households in year for household , is whether or not the household uses digital payments, is a set of control variables at the head of household, household, and district levels, and are time and province fixed effects, respectively, and is a random disturbance term.

Secondly, to further test the mechanism by which digital payments affect the financial vulnerability of rural households, the following model is constructed, based on Baron and Kenny (1986):

Where is the mechanism variable of digital payment affecting the financial vulnerability of rural households, and are defined as in Equation 1. The coefficient is significant indicating that digital payment significantly affects the mechanism variable, and the coefficient is significant indicating that the mechanism variable has a significant effect on the financial vulnerability of rural households.

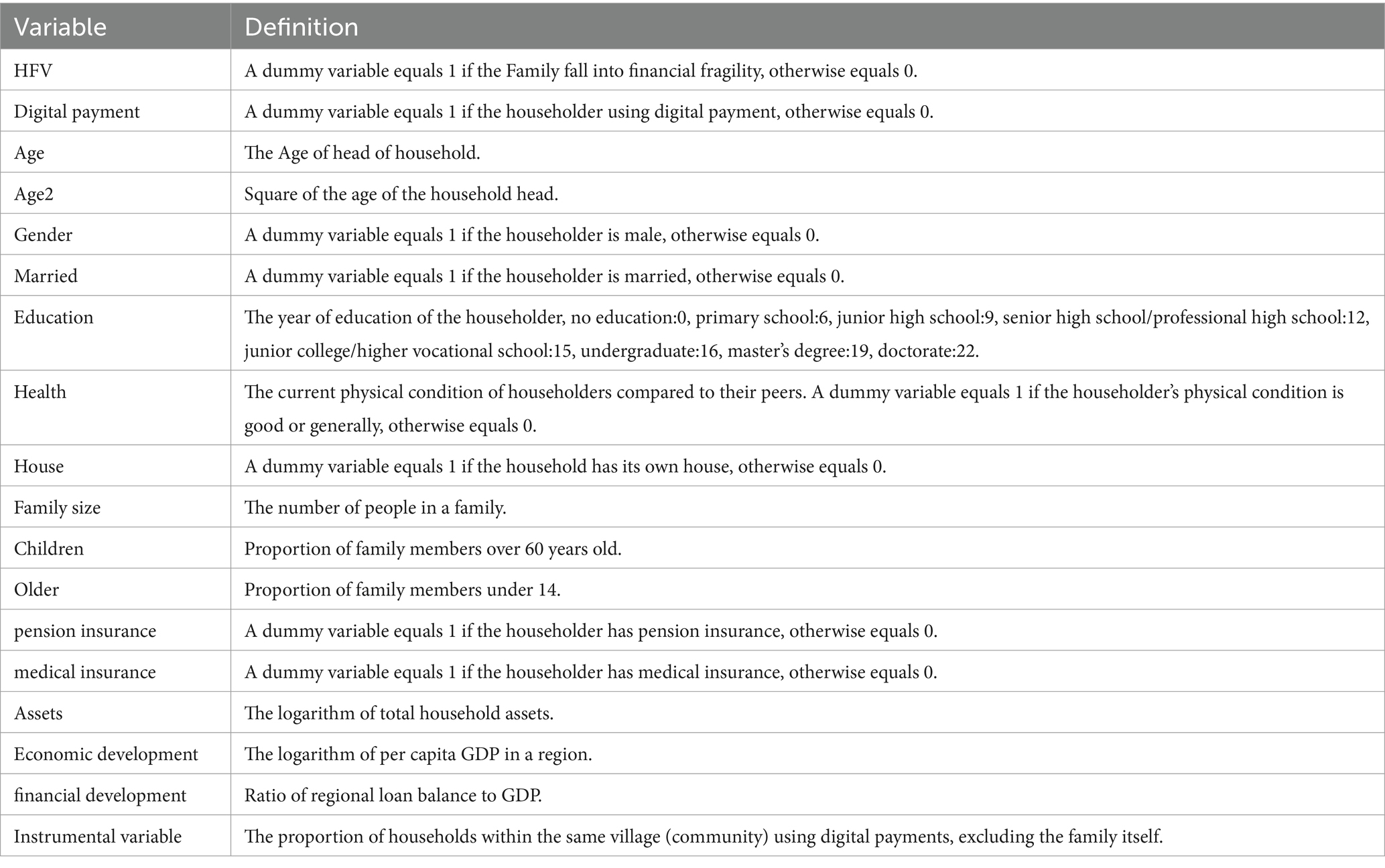

4.2 Variable description

4.2.1 Explained variable

Financial vulnerability of rural households. The existing literature has constructed measures from multiple perspectives, but mainly in the dimensions of ‘unable to make ends meet’ and ‘insolvency’ (Lusardi et al., 2011; Ampudia et al., 2016; Leika and Marchettini, 2017). Adopting the ‘financial margin’ approach as suggested by Brunetti et al. (2016). The financial vulnerability of households is measured from the perspective of household solvency, considering both household liquidity and solvency. The financial vulnerability of the specific rural household can be expressed as Equation 4:

Where denotes total household income, which is the sum of all incomes; denotes liquid assets, including cash, deposits, and the value of financial products such as funds and bonds; denotes household daily life expenditures, including daily necessities, food and drink, transport and communication, and clothing expenditures, etc.; denotes total household debt; and denotes unplanned household expenditures, which include uncertain expenditures such as medical care (He and Zhou, 2022). Households face financial vulnerability when , i.e., when total household income and liquid assets are unable to repay debts and expenditures.

4.2.2 Core explanatory variables

Digital payment. This is mainly based on the use of digital payment software by household heads in the CHFS questionnaire. Specifically, rural households that used digital terminal payments, such as Alipay APP, WeChat Pay, mobile banking, etc. via devices like mobile phones and iPad in the 2017 CHFS questionnaire are assigned a value of 1; otherwise 0. Since the relevant questions in the 2019 CHFS questionnaire have been changed, households with third-party payment accounts such as Alipay, WeChat Pay, and Jingdong Wallet are defined as households that use digital payments with a value of 1, and 0 otherwise, with reference to Yin et al. (2019).

4.2.3 Control variable

Referring to existing literature practices (Noerhidajati et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024), this study selected control variables in terms of household head characteristics, household characteristics and regional characteristics, respectively. The household head level includes the age of the household head, age squared, gender, marital status, education level, and health level; the household level includes whether the household owns a house, the size of the household, the percentage of young children, the percentage of elderly people, the existence of pension insurance, the existence of medical insurance, and the logarithm of the total household assets; and the regional level includes the level of economic development and the level of financial development.

4.2.4 Instrumental variable

Despite using a double fixed effects model in the regressions, there is still a possibility of residual endogeneity issues. Firstly, the issue of omitted variables must be addressed. It is conceivable that both the use of digital payment platforms by rural households and the financial vulnerability of households are influenced by unobservable factors. These include household payment preferences, respondents’ digital literacy and the prevailing payment environment. Farm households’ propensity for utilizing a specific payment method and their comprehension of smart devices may also exert an influence, giving rise to omitted variable bias. Secondly, the measurement error problem must be considered. It is important to note that there are some differences between the questionnaire questions on digital payment use in the 2017 questionnaire and 2019 questionnaire. These differences may lead to measurement errors in digital payment variables and affect the estimation precision. Finally, there is the issue of reverse causation. While digital payments have been shown to impact the financial vulnerability of rural households, the converse may also be true, i.e., that the financial vulnerability of rural households may, in turn, have an impact on whether farmers use digital payments.

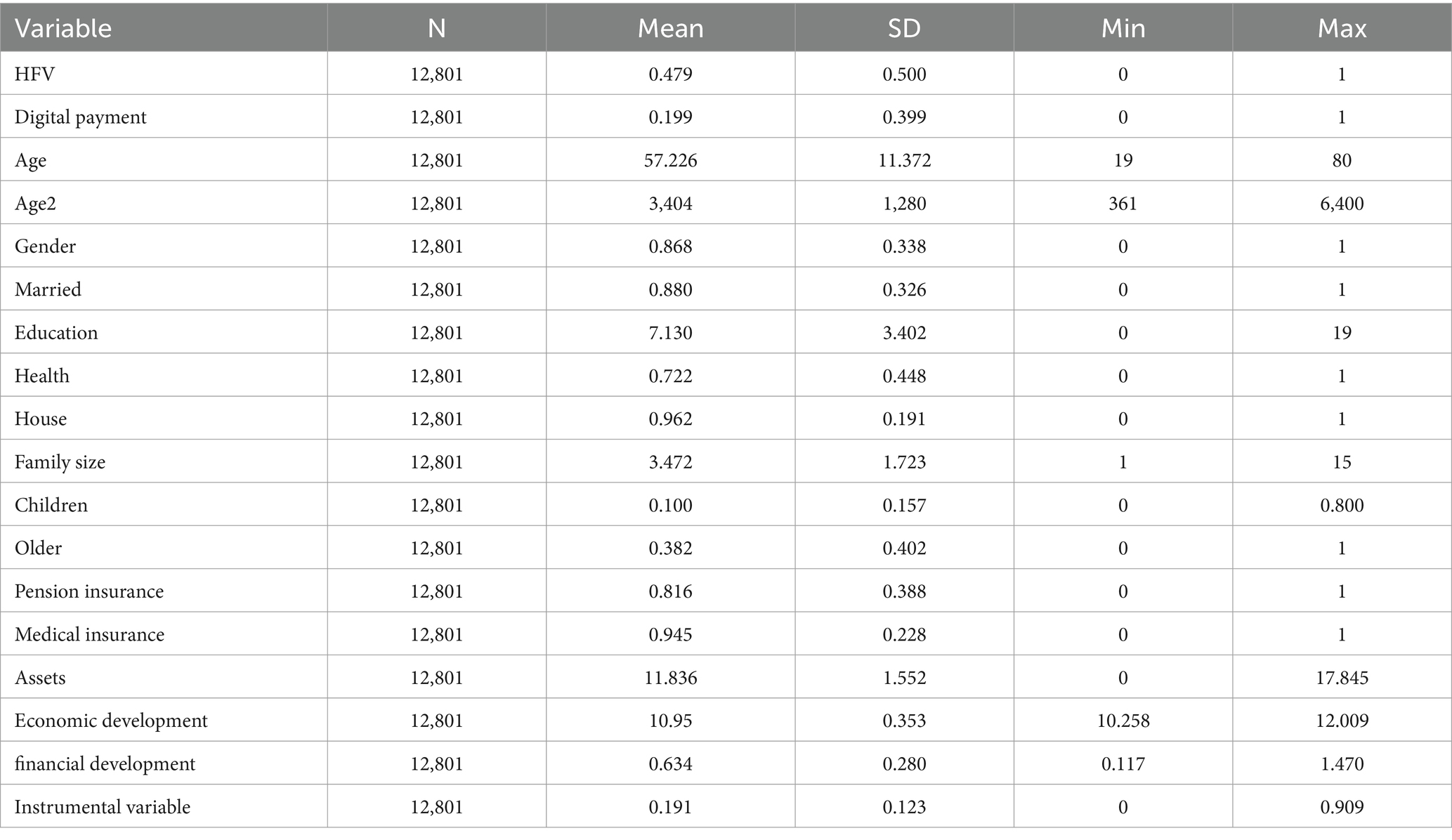

This paper uses an instrumental variable approach to mitigate possible endogeneity problems. Drawing on Feng and Du (2023), using the proportion of households using digital payments in the same village (community) in addition to the household as an instrumental variable can satisfy both endogeneity and exogeneity principles. The use of digital payments has a certain imitation effect, and the use of digital payments by surrounding groups or households will have a greater relevance to the household’s judgment of whether to use them or not, so there is a correlation between the explanatory variable and the instrumental variable. In addition, the average level of the use of digital payments within the same village (community) hardly affects the household’s financial vulnerability, and the instrumental variable has an exogenous nature. Therefore, the selection of this instrumental variable is appropriate. Tables 1, 2 respectively provide variable definitions and descriptive statistical results.

4.3 Data sources

The data for this study is sourced from the 2017 and 2019 China Household Finance Survey Data (CHFS) released by the China Household Finance Survey and Research Center. This data is collected through a nationwide household finance survey conducted every 2 years, using a stratified, three-stage proportional to scale (PPS) sampling design method that is consistent with the National Bureau of Statistics in terms of population age, gender structure, and other aspects. The survey questionnaire contains information on respondents’ use of digital payments, household head characteristics, household income, assets, liabilities, and other aspects, providing good data support for studying the vulnerability of digital payments and rural household finance. This article only retains tracking individual samples from 2017 and 2019, and after removing missing values, ultimately obtains 12,801 observation data.

5 Results

5.1 Baseline results

This study uses Equation 1 to analyze the results of a baseline regression of the impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households (Table 3). Columns (1)–(2) display the results of the regressions outcomes without control variables, indicating that the coefficient of the impact of digital payment on the financial vulnerability of rural households is significantly negative, regardless of whether time-fixed effects and province-fixed effects are included. Columns (3)–(4) show similarly significant negative coefficients for digital payment after controlling for head of household, household and district level variables. Given that the model may still be affected by endogeneity issues, the CMP model is used for instrumental variable estimation. The results are shown in column (5), with significant coefficients on the endogeneity test parameter atanhrho_12, indicating that the core explanatory variables are endogenous, and that the estimation results of the CMP model are more plausible. The estimation results of the SLS model are shown in column (6). Among the two-stage estimation results, the first stage F-value is 148.86, which is greater than the empirical value of 10, indicating that the correlation requirement is met. Meanwhile, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM rejects the hypothesis that the instrumental variables are not identifiable, and the value of the Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic is 691.158, which is greater than the critical value of 16.38 at the 10% level of the Stock-Yogo weak instrumental variables test, indicating that there is no weak instrumental variables. It indicates that there is no weak instrumental variable situation. The results in columns (5)–(6) all indicate that the coefficient of the impact of digital payment on the financial vulnerability of rural households remains significantly negative even after accounting for endogeneity. These findings suggest that digital payment can significantly reduce the financial vulnerability of rural households, thereby supporting hypothesis H1.

5.2 Robustness tests

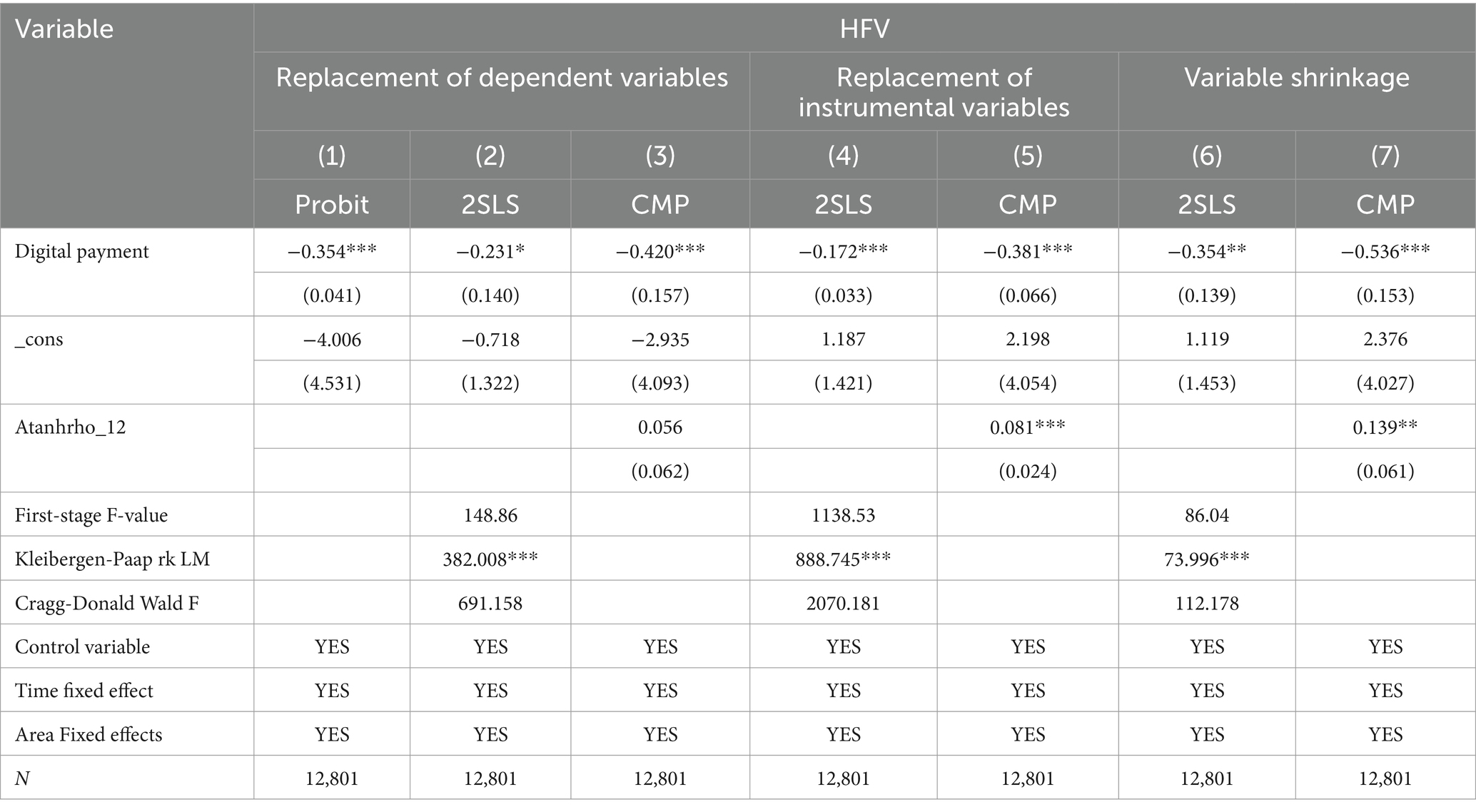

To further validate the reliability of the results, this study conducts robustness tests by replacing the explanatory variables, instrumental variables, propensity score matching, and sample shrinkage.

5.2.1 Replace the dependent variable test

Drawing on Loke (2017), the financial vulnerability of rural households is measured in terms of emergency savings and over-indebtedness, defining a household with insufficient household savings to support 3 months of daily expenses as having an emergency savings deficit and a household with a debt-to-income ratio exceeding 30% as over-indebted. Rural households that meet both the criteria for emergency savings deficit and over-indebtedness are designated as 1, otherwise 0, indicating financial vulnerability. The results are presented in columns (1) through (3) of Table 4. The findings of the CMP model estimation, with insignificant coefficients of the endogeneity test parameter, atanhrho_12, suggest that the outcomes of the Probit model are more plausible. The results indicate that the probit model has a coefficient of −0.354 which is significant at the 1% level, and the 2SLS model has a coefficient of −0.231 which is significant at the 10% level. The negatively significant of the coefficients in both the probit and 2sls models suggests that the coefficients remain negative after substituting the dependent variable, indicating that results are robust.

5.2.2 Replace instrumental variable test

To ensure the robustness of the endogeneity estimation results, considering that the estimation outcomes will be influenced by the choice of instrumental variables, we refer to Yin et al. (2019) and select the decision to make online purchases as the second instrumental variable for examination, as it fulfills both the correlation and exogeneity criteria. Digital payment is the main payment method for online shopping, and there is a correlation between household online shopping and digital payment use. In addition, the presence or absence of online shopping has no direct effect on household financial vulnerability and satisfies the exogeneity principle. The estimation results are shown in columns (4)–(5) in Table 4. The results showed that after replacing the instrumental variables, the digital payment coefficients in the 2SLS and CMP models were − 0.172 and − 0.381, respectively, both significantly negative at the 1% level, once again proving the robustness of the results.

5.2.3 Variable shrinkage test

The estimation model may also be influenced by extreme values of the variables. To mitigate the impact of these values, the total assets and total income variables for the farm household are adjusted by applying upper and lower 1% shrinkage. Columns (6) and (7) of Table 4 show that the coefficient of the endogeneity test parameter atanhrho_12 is significant in the CMP model results, indicating that the CMP model results are more credible. The digital payment coefficients of the 2SLS and CMP models are −0.254 and − 0.536, respectively, which are significant at the 5 and 1% levels, indicating that the baseline regression estimation results are robust.

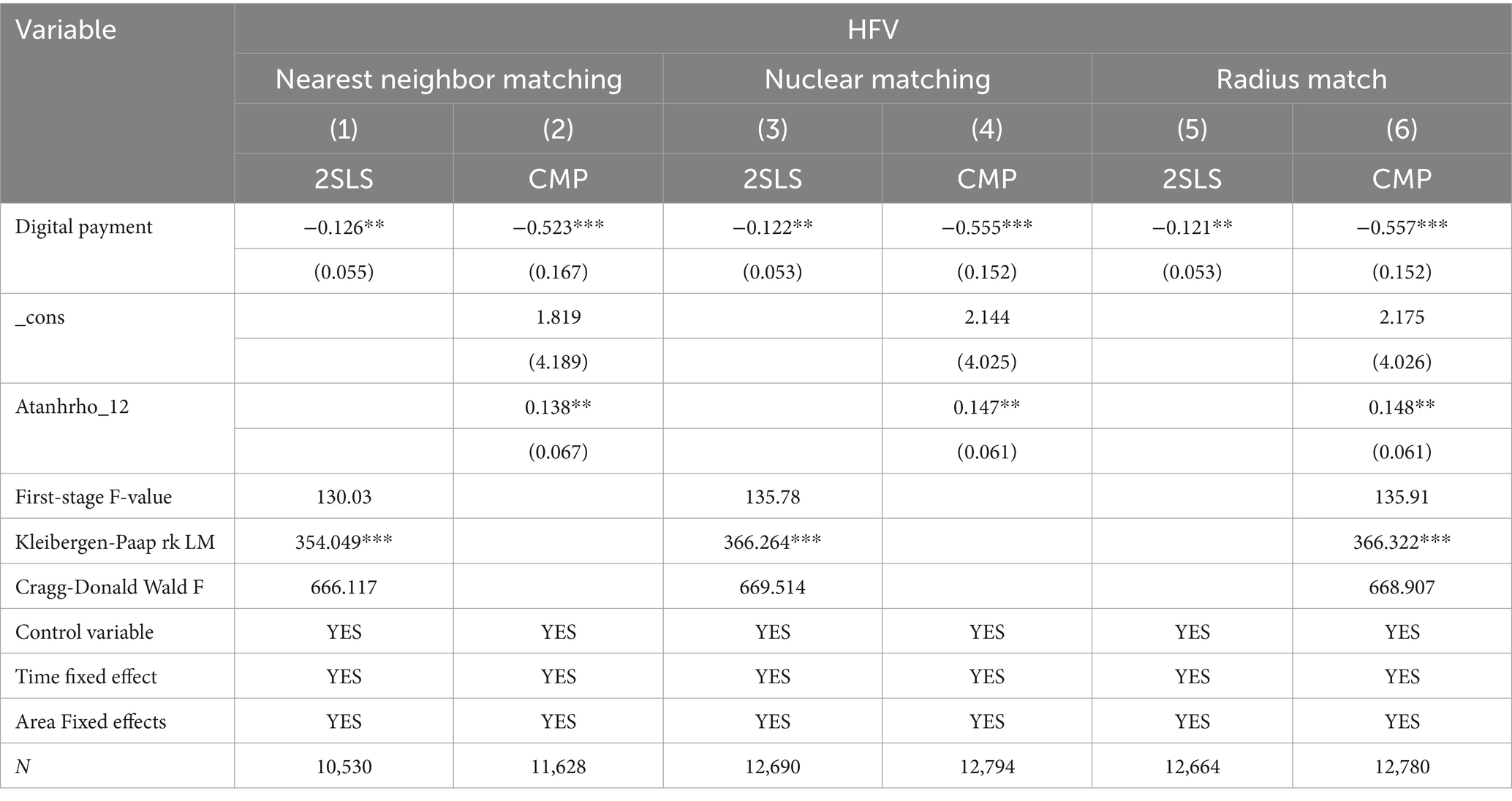

5.2.4 Propensity score matching test

The impact of digital payments on financial vulnerability of rural households may be subject to bias due to self-selection. Digital payment utilization patterns are not random and may be influenced by unobservable factors such as individual capabilities, cognitive abilities, and mental state. Rural households with higher individual capabilities or cognitive levels are more likely to adopt digital payments and exhibit lower household financial vulnerability. To address this potential bias, the propensity score method (PSM) is employed. Given the applicability of PSM to cross-sectional data, this study employs an annual matching method. Specifically, propensity score values are calculated separately for each year using the covariates to test for differences between the experimental and control groups, subsequently, the data for each year are combined and re-estimated. The estimation results following the implementation of 4th order nearest neighbor, kernel matching, and radius matching are reported in Table 5. The results indicate that the estimated coefficient of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households remains significantly negative, thereby validating the robustness of the baseline regression results.

6 Heterogeneity analysis

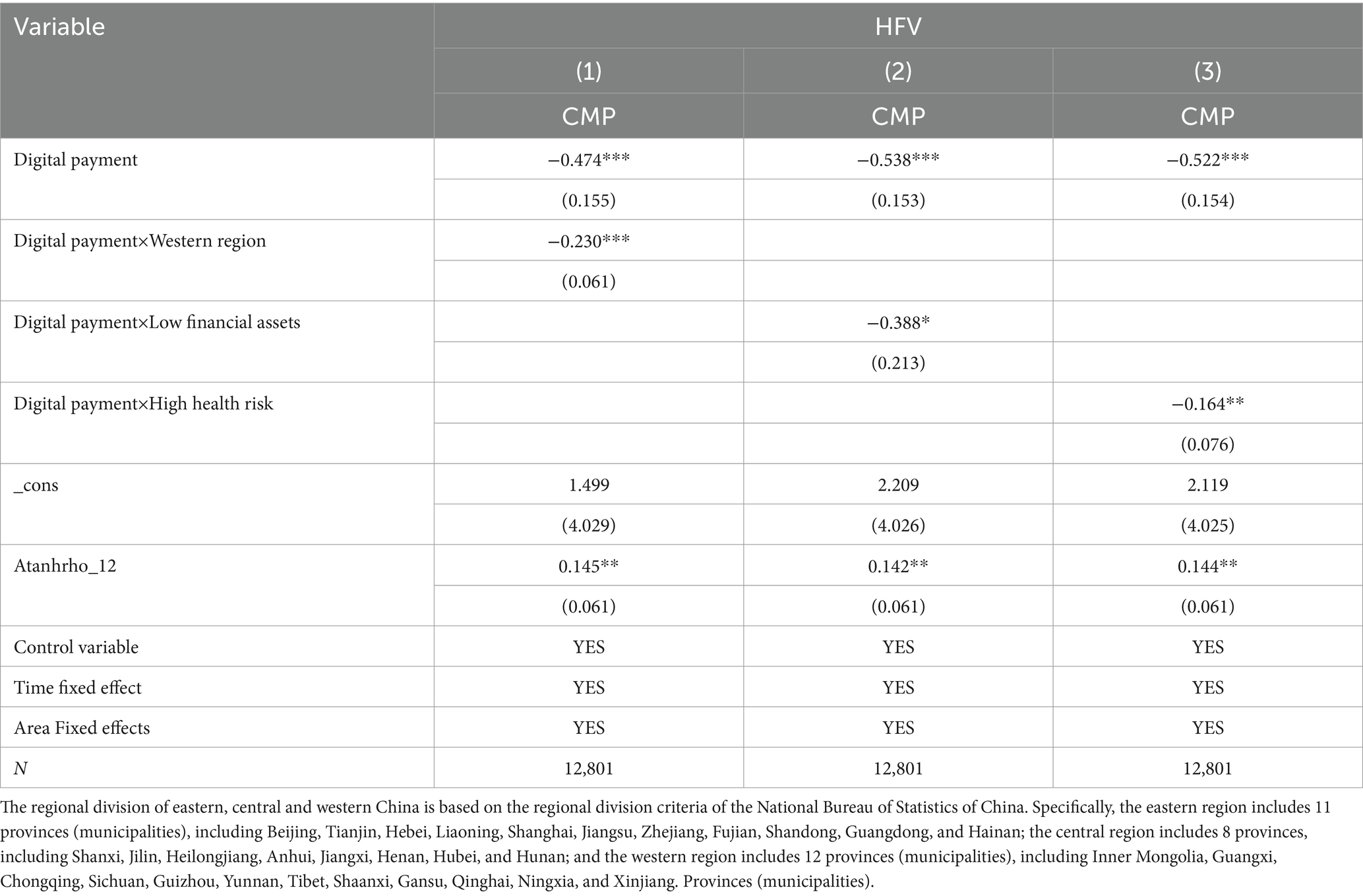

The previous results found that digital payments significantly mitigate rural household financial vulnerability, but there are differences in digital payment use and rural household financial vulnerability among different groups. Therefore, the heterogeneous impact of this mitigating effect across regions and household characteristics needs to be further explored.

6.1 Regional heterogeneity

China’s regional financial development exhibits imbalances. Compared to the central and eastern regions, the rural financial system in the western region is less developed, and the effective supply of financial services is insufficient. This hinders rural residents’ access to a broader range of financial information and services, and exacerbates the limited ability of households to manage risk. Access to financial services is costly, which raises the cost threshold for participation in the financial market and hinders the promotion of financial inclusion. Digital payments have demonstrated their ability to overcome the spatial and temporal constraints of financial services, thereby enhancing the financial accessibility of rural households in the western region. This has led to a decrease in the cost and ease of rural residents’ access to financial services, thereby effectively reducing financial vulnerability. The results in column (1) of Table 6 demonstrate that the coefficient of the interaction term between digital payments and the western region is significantly negative. This finding indicates that digital payments have a more significant impact on reducing the financial vulnerability of rural households in the western region compared to the central and eastern regions. The reason for this is that the use of digital payments by rural households in the western region reduces their financial vulnerability by more effectively lowering the transaction costs of accessing financial services and providing them with more economic opportunities and risk management tools (Wu and Zhang, 2024). In contrast, in the central and eastern regions, where digital infrastructure is more developed, the use of mobile payments has a smaller impact on improving the efficiency of household financial services.

6.2 Heterogeneity of household financial assets

In the context of traditional financial institutions, wealth and income are the criteria used to assess creditworthiness, thereby excluding the vast majority of rural households from access to financial markets. In this paper, the sample is divided into low and medium-high financial asset households based on the 10th percentile of the household financial asset variable in the sample. The results in column (2) of Table 6 indicate that the interaction term between digital payments and low-financial-asset households has a significantly negative coefficient. This can be attributed to the fact that digital payments have lowered the barrier to accessing financial services for rural residents, enabling the effective financial needs of low-asset households to be adequately met by offering a diverse range of financial products, thus reducing the financial vulnerability of these households (Tao et al., 2023).

6.3 Heterogeneity of health risks

Health risks are an important source of risk that can impact the financial situation of households. When experienced, health risks not only lead to a sharp increase in unanticipated necessary household expenditures but also exacerbate the household’s financial status by affecting labor force participation and increasing household income volatility (Vo and Van, 2019). In this paper, based on the CHFS questionnaire, ‘What is the respondent’s current health status compared to their peers?’ Health risk groupings were set up, with the head of household answering ‘very good, good, fair’ as a low to moderate health risk and ‘bad, very bad’ as a high health risk. The results in column (3) of Table 6 suggest that digital payments have a more significant mitigating effect on the financial vulnerability of households with high health risks. This is because digital payments not only increase the availability of commercial insurance for rural households, enhancing their chances of obtaining a claim after experiencing a health risk and significantly mitigating the negative impacts of health risks on rural households’ finances, but also mitigate the financial vulnerability of rural households by providing them with access to formal credit and preventing them from falling into liquidity constraints (Liao and Du, 2024).

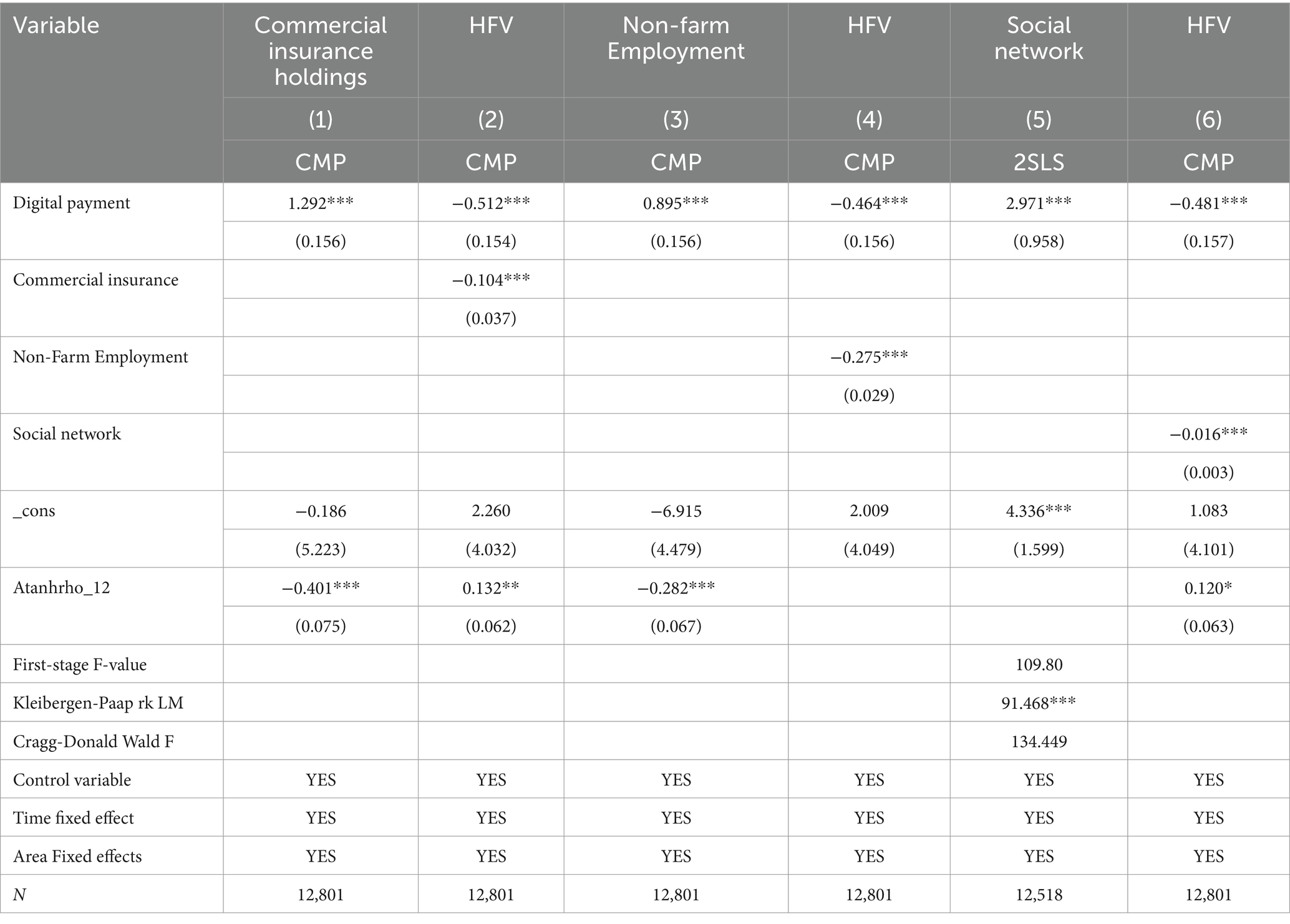

7 Mechanism of action analysis

This study uses Equations 2,3 to examine the mechanisms by which digital payments affect the financial vulnerability of rural households from the perspectives of commercial insurance holdings, non-farm employment, and the social networks of farm households, respectively.

7.1 Commercial insurance holding mechanisms

In this paper, we define a household as holding commercial insurance if at least one member of the household holds any of the commercial insurance policies, thereby setting the commercial insurance holding dummy variable. Column (1) in Table 7 reports the regression results of the effect of digital payments on commercial insurance holdings of farm households. It is found that the coefficient of digital payment is significantly positive, indicating that digital payment significantly contributes to commercial insurance holding of farm households. Further test the regression of digital payments, commercial insurance holdings simultaneously on household financial vulnerability as shown in column (2). The coefficients for both digital payment and commercial insurance holding variables remain significantly negative, suggesting that holding commercial insurance significantly mitigates effect on rural household financial vulnerability. This suggests that digital payments can enhance household risk transfer capacity by promoting commercial insurance holdings of rural households, thus mitigating household financial vulnerability.

7.2 Non-farm employment promotion mechanism

Based on the design of the CHFS questionnaire, a dummy variable for non-farm employment was established and the ‘non-farm employment’ dummy variable was assigned a value of 1 if the farm household had engaged in non-farm work in the past year, and 0 otherwise. The results in column (3) of Table 7 show that digital payments significantly contributed to the non-farm employment of farm households. The results in column (3) of Table 7 show that digital payments significantly contribute to the non-farm employment of farm households. The results in column (4) indicate that the coefficients of both digital payments and non-farm employment variables are significantly negative, suggesting that the promotion of non-farm employment is an important channel through which digital payments alleviate household financial vulnerability.

7.3 Social network broadening mechanisms

Referring to Chai et al. (2019), the logarithm of the sum of household income and expenditure on holidays, as well as red and white celebrations, is used as a variable to measure the level of household social network. The results in column (5) of Table 7 indicate that digital payments raise the level of social network engagement among farm households. Column (6) reveals that the coefficients of digital payments and social network are significantly negative. The increase in the level of household social network, and thus credit or risk sharing, is an important mechanism of digital payments to mitigate the financial vulnerability of farm households. In summary, digital payments mitigate the financial vulnerability of rural households by promoting the holding in commercial insurance, non-farm employment, and enhancing social networks. Consequently, research hypotheses H2-H4 are tested.

8 Conclusion and policy recommendations

8.1 Conclusion

This paper empirically analyzes the impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households and examines mechanisms using data from the 2017–2019 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS). The findings indicate that the use of digital payment reduces the financial vulnerability of rural households. The mechanism analysis finds that digital payments mitigate household financial vulnerability by enabling the hold of commercial insurance, facilitating non-farm employment, and expanding of social networks. In addition, this mitigating effect possesses heterogeneity. Digital payments have a greater mitigating effect on the financial vulnerability of rural households with low financial assets and high health risks in the western region than in the central and eastern regions, with high financial assets and low health risks.

8.2 Policy recommendations

Based on the above conclusions, this paper obtains the following policy insights:

Firstly, promote the deep integration of digital technology with financial services, and full leverage the mitigating impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households. Strengthen the construction of rural digital infrastructure in areas that lag behind in traditional finance. Use digital payment as a bridge connecting financial institutions with rural information network platforms. Increase the degree of digitalization in rural inclusive finance, optimize the financial service supply mechanism, and reduce the threshold and cost of access to financial services for rural households.

Secondly, expand the comprehensive service functions of digital payment to enhance the risk-bearing capacity of rural households. Encourage insurance companies to integrate traditional insurance business with digital payment platforms, utilize big data, artificial intelligence and other technologies to reduce management costs, enhance insurance inclusive services, increase the risk transfer capacity of rural households. In addition, it will continue to enhance the information and social interaction functions of digital payments, promote the sharing of employment information and the expansion of social networks, and help rural households obtain non-farm employment information and employment opportunities, thereby enhancing the ability of families to self-insure and share risks.

Thirdly, following the principle of tailoring services to local conditions, we promote innovation in digital payment services and provide financial products and services that match different groups. Based on the location, financial asset level and health risk level of different rural households, the use of big data, cloud computing and other information technology means to collect residents’ daily information, and the development of differentiated financial products and services with different risks and returns for different households.

Fourthly, while digital payments can mitigate household financial vulnerability, vigilance is necessary regarding their potential consequences. Digital payments can increase the scale of household debt, including formal borrowing, private borrowing and platform borrowing, thus raising household debt leverage and creating a more significant financial risk issue. Moreover, older individuals are less receptive to digital financial products, including digital payments, which can easily lead to a rejection of digital payment among this demographic. Therefore, there is a need to enhance the popularity and education on the safe use of digital payments and to strengthen the level of digital financial regulation, aiming to maximize the role of digital payments in mitigating the financial vulnerability of rural households.

8.3 Limitations and future directions

Furthermore, there is room for improvement in this study. For one thing, the available microdata only support the examination of the impact of rural household use on household financial vulnerability in China, while the effect of digital payments on other developing countries remains unclear. For another, the use behavior of digital payments can significantly differentially impact household financial vulnerability. Specifically, some farmers restrict their use of the digital payment platform to its electronic payment and money transfer functions, failing to fully understand its broader capabilities. Conversely, a proportion of farmers leverage the e-payment functionality for more comprehensive benefits, including the acquisition of financial intelligence and knowledge. However, due to the lack of relevant data in existing public survey databases, the specific impact of these two segments of farmers using digital payment platforms remains unknown. Consequently, future research should compare the impact of digital payment usage on household financial vulnerability in rural households across different developing countries worldwide, and explore in depth the differentiated effects of digital payment behavior.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://chfs.swufe.edu.cn/.

Author contributions

FX: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. LZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Project of the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund, Ministry of Education, Research on the Impact of Population Aging on the Financial Vulnerability of Rural Households and the Response Path on the Financial Demand Side (no. 23YJA790101); Basic Project of Guangdong Financial Society: Stage research results on innovative financial support policies for new agricultural management entities (no. CKT202412).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdullah, Y. S. (2019). Ethnic disparity in financial fragility in Malaysia. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 46, 31–46. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-12-2017-0585

Afawubo, K., Couchoro, M. K., Agbaglah, M., and Gbandi, T. (2020). Mobile money adoption and households’ vulnerability to shocks: evidence from Togo. Appl. Econ. 52, 1141–1162. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2019.1659496

Alger, I., and Weibull, J. W. (2010). Kinship, incentives, and evolution. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 1725–1758. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.4.1725

Ali, L., Khan, M. K. N., and Ahmad, H. (2020). Financial fragility of Pakistani household. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 41, 572–590. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09683-y

Ampudia, M., Vlokhoven, H. V., and Zochowski, D. (2016). Financial fragility of euro area households. J. Financ. Stab. 27, 250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jfs.2016.02.003

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Beck, T., Pamuk, H., Ramrattan, R., and Uras, B. R. (2018). Payment instruments, finance and development. J. Dev. Econ. 133, 162–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.01.005

Brunetti, M., Giaeda, E., and Torricelli, C. (2016). Is financial fragility a matter of illiquidity?An appraisal for Italian households. Rev. Income Wealth 62, 628–649. doi: 10.1111/roiw.12189

Carleton, T. A., and Hsiang, S. M. (2016). Social and economic impacts of climate. Science 353:aad9837. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9837

Chai, S., Chen, Y., Huang, B., and Ye, D. (2019). Social networks and informal financial inclusion in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 36, 529–563. doi: 10.1007/s10490-017-9557-5

Chen, S., and Ravallion, M. (2021). Reconciling the conflicting narratives on poverty in China. J. Dev. Econ. 153:102711. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102711

Chen, C., Tan, Z., and Liu, S. (2024). How does financial literacy affect households’ financial fragility? The role of insurance awareness. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 95:103518. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2024.103518

Chen, B., Zeng, N., and Tam, K. P. (2024). Do social networks affect household financial vulnerability? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 59:104710. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2023.104710

Closset, M., Dhehibi, B., and Aw-Hassan, A. (2015). Measuring the economic impact of climate change on agriculture: a ricardian analysis of farmlands in Tajikistan. Clim. Dev. 7, 454–468. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2014.989189

Deng, L., and Qian, P. (2024). Mitigating effect of digital payments on the micro-enterprises’ financing constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 62:105209. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.105209

Dong, J. (2024). Digital finance’s impact on household portfolio diversity: evidence from Chinese households. Financ. Res. Lett. 70:106347. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106347

Duca, J. V., and Rosenthal, S. S. (1993). Borrowing constraints, household debt, and racial discrimination in loan markets. J. Financ. Intermed. 3, 77–103. doi: 10.1006/jfin.1993.1003

Fafchamps, M., and Gubert, F. (2007). The formation of risk sharing networks. J. Dev. Econ. 83, 326–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.05.005

Fei, X., Hamilton, G. G., and Zheng, W. (1992). From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Feng, X., and Du, G. (2023). Does financial knowledge contribute to the upgrading of the resident's consumption? Financ. Res. Lett. 58:104535. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2023.104535

He, L., and Zhou, S. (2022). Household financial vulnerability to income and medical expenditure shocks: measurement and determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:4480. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084480

Hong, C. Y., Lu, X., and Pan, J. (2020). FinTech adoption and household risk-taking: from digital payments to platform investments (no. w28063). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hu, L., Ji, L., Zhu, T., Yang, C., and Wang, D. (2024). Does Mobile payment raise the poverty-alleviation resilience of Chinese households? Rev. Dev. Econ. 1:166. doi: 10.1111/rode.13166

Hu, Z. L., and Wang, S. H. (2024). Can labor mobility alleviate the financial vulnerability of rural households? An empirical analysis based on the perspective of social networks. Financ. Forum 29, 59–69. doi: 10.16529/j.cnki.11-4613/f.2024.02.007

Huang, Y., Wang, X., and Wang, X. (2020). Mobile payment in China: practice and its effects. Asian Econ. Papers 19, 1–18. doi: 10.1162/asep_a_00779

Huang, Z., Wang, L., and Yu, W. (2025). Financial development, electronic payments, and residents' consumption: evidence from rural China. Financ. Res. Lett. 71:106455. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106455

ISDR (2004). Living with risk: A global review of disaster reduction initiatives. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Publications.

Kleimeier, S., Hoffmann, A. O., Broihanne, M. H., Plotkina, D., and Göritz, A. S. (2023). Determinants of individuals’ objective and subjective financial fragility during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bank. Financ. 153:106881. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2023.106881

Leika, M., and Marchettini, D. (2017). A generalized framework for the assessment of household financial vulnerability. IMF Working Papers 228, 1–56. doi: 10.5089/9781484322352.001

Li, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, R., Zhang, X., and Zhang, Z. (2022). How did the risk of poverty-stricken population return to poverty in the karst ecologically fragile areas come into being?—evidence from China. Land 11:1656. doi: 10.3390/land11101656

Liao, L., and Du, M. (2024). How digital finance shapes residents' health: evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 87:102246. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2024.102246

Liu, J., Chen, Y., Chen, X., and Chen, B. (2024). Digital financial inclusion and household financial vulnerability: an empirical analysis of rural and urban disparities in China. Heliyon 10:e35540. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35540

Liu, Y., and Dewitte, S. (2021). A replication study of the credit card effect on spending behavior and an extension to mobile payments. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 60:102472. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102472

Liu, T., Fan, M., Li, Y., and Yue, P. (2024). Financial literacy and household financial resilience. Financ. Res. Lett. 63:105378. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.105378

Loke, Y. J. (2017). Financial vulnerability of working adults in Malaysia. Contemp. Econ. 11, 205–218. doi: 10.5709/ce.1897-9254.237

Lusardi, A., Schneider, D. J., and Tufano, P. (2011). Financially fragile households: evidence and implications. NBER Working Papers 1:72. doi: 10.3386/W17072

Lusardi, A., and Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. J. Pension Econ. Finance 14, 332–368. doi: 10.1017/S1474747215000232

Ma, X., and Ma, T. (2024). Intergenerational educational mobility and family economic vulnerability: evidence based on the CHFS study. Financ. Res. Lett. 69:106054. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106054

Mabhuye, E. B. (2024). Vulnerability of communities' livelihoods to the impacts of climate change in north-western highlands of Tanzania. Environ. Dev. 49:100939. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2023.100939

Marshall, A., Dezuanni, M., Burgess, J., Thomas, J., and Wilson, C. K. (2020). Australian farmers left behind in the digital economy–insights from the Australian digital inclusion index. J. Rural. Stud. 80, 195–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.09.001

Martín-Legendre, J. I., and Sánchez-Santos, J. M. (2024). Household debt and financial vulnerability: empirical evidence for Spain, 2002–2020. Empirica 51, 703–730. doi: 10.1007/s10663-024-09617-z

Noerhidajati, S., Purwoko, A. B., Werdaningtyas, H., Kamil, A. I., and Dartanto, T. (2021). Household financial vulnerability in Indonesia: measurement and determinants. Econ. Model. 96, 433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2020.03.028

Rodríguez-Barillas, M., Poortvliet, P. M., and Klerkx, L. (2024). Unraveling farmers' interrelated adaptation and mitigation adoption decisions under perceived climate change risks. J. Rural. Stud. 109:103329. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103329

Sargani, G. R., Jiang, Y., Chandio, A. A., Shen, Y., Ding, Z., and Ali, A. (2023). Impacts of livelihood assets on adaptation strategies in response to climate change: evidence from Pakistan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 6117–6140. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02296-5

Savari, M., Khaleghi, B., and Sheheytavi, A. (2024). Iranian farmers' response to the drought crisis: how can the consequences of drought be reduced? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 114:104910. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104910

Stampini, M., Robles, M., Sáenz, M., Ibarrarán, P., and Medellín, N. (2016). Poverty, vulnerability, and the middle class in Latin America. Latin. Am. Econ. Rev. 25, 1–44. doi: 10.1007/s40503-016-0034-1

Su, M. M., Wall, G., and Jin, M. (2016). Island livelihoods: tourism and fishing at long Islands, Shandong province, China. Ocean Coastal Manag. 122, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.11.014

Tao, Z., Wang, X., Li, J., and Wei, X. (2023). How can digital financial inclusion reduces relative poverty? An empirical analysis based on China household finance survey[J]. Financ. Res. Lett. 58:104570. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2023.104570

Urrea, M. A., and Maldonado, J. H. (2011). Vulnerability and risk management: the importance of financial inclusion for beneficiaries of conditional transfers in Colombia. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 32, 381–398. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2011.647442

Vo, T. T., and Van, P. H. (2019). Can health insurance reduce household vulnerability? Evidence from Viet Nam. World Dev. 124:104645. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104645

Wan, J., Wang, B., Hu, Y., and Jia, C. (2023). The impact of risk perception and preference on farmland transfer-out: evidence from a survey of farm households in China. Heliyon 9:e19837. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19837

Wang, X., and Fu, Y. (2021). Digital financial inclusion and vulnerability to poverty: evidence from Chinese rural households. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 14, 64–83. doi: 10.1108/CAER-08-2020-0189

Wu, Y., and Zhang, J. (2024). Digital inclusive finance and rural households’ economic resilience. Financ. Res. Lett. 74:106706. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2024.106706

Yin, Z., Gong, X., Guo, P., and Wu, T. (2019). What drives entrepreneurship in digital economy? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 82, 66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.026

Yu, L. (2023). Making space through finance: spatial conceptions of the rural in China’s rural financial reforms. Geoforum 138:103662. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.11.004

Zhang, L., and Zhao, H. (2024). From excessive spending to debt delinquency: should we blame mobile payments? Comput. Hum. Behav. 165:108533. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2024.108533

Zhao, X., Lan, F., Guo, M., and Zhang, L. (2024). Differences in the impact of land transfer on poverty vulnerability among households with different livelihood structures. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1425762. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1425762

Zhou, L., Pan, L., Zhang, H., and Cai, J. (2024). Aging and household economic vulnerability: perspective from asset allocation. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 1, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10834-024-10011-x

Keywords: digital payment, household financial vulnerability, commercial insurance, non-farm employment, social networks

Citation: Xu F and Zhang L (2025) The impact of digital payments on the financial vulnerability of rural households: empirical evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1553237. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1553237

Edited by:

Siphe Zantsi, Agricultural Research Council of South Africa, South AfricaReviewed by:

Zheng Cai, Northeast Agricultural University, ChinaWalter Shiba, Agricultural Research Council of South Africa, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Xu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lezhu Zhang, eGYwMzEyQHN0dS5zY2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

Fan Xu

Fan Xu Lezhu Zhang*

Lezhu Zhang*