- 1School of Business, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

- 2School of Agriculture, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

Introduction: In the context of the growing global trend toward the deep integration of free trade agreements (FTAs), enhanced regional agricultural collaboration has significantly impacted the agricultural global value chains (AGVCs). Clarifying how FTA depth affects a country’s AGVC participation is crucial for promoting high-quality agricultural development and deepening international agricultural cooperation.

Methods and goals: This paper constructs and calculates indicators for FTA depth and the AGVC index, employing fixed effects models, PPML models, and other methods, aiming to empirically analyze how the depth of FTAs influences a country’s participation in AGVC and the mechanisms involved.

Results: The findings indicate that an increase in FTA depth enhances a country’s degree of participation and position within the AGVC. Both the ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provision depth indices exert a significant positive influence on increasing participation and position within the AGVC, with the ‘WTO-X’ provision depth index demonstrating a more pronounced effect than the ‘WTO+’ provision. Furthermore, the positive effects of increased FTA depth on the integration of developed countries into the AGVC are greater than those on developing countries. Additional analysis reveals that FTA depth promotes trade liberalization and investment facilitation, thereby enhancing countries’ participation and position in the AGVC.

Discussion: The findings of this paper provide reliable empirical evidence for understanding the influence of FTA depth on AGVC and offer valuable policy insights for countries actively pursuing deeper FTAs.

Policy recommendations: To further advance the evolution of AGVC, it is recommended that countries actively promote the signing of deeper FTAs to accelerate trade liberalization and investment facilitation. At the same time, developed countries should strengthen agricultural technology research and development, assisting developing countries through technology transfer to jointly build a sustainable GVC; developing countries should enhance agricultural cooperation and improve their negotiating power in FTA discussions.

1 Introduction

Amid prolonged stagnation in multilateral trade talks under the World Trade Organization (WTO), coupled with the rise of anti-globalization sentiments, the prevalence of trade protectionism, frequent geopolitical conflicts, and various uncertainties such as public health crises, the global trade landscape has become increasingly complex and volatile. To promote international economic and trade cooperation, countries worldwide are actively pursuing FTAs that offer greater flexibility in rules and more convenient coordination. From 2003 to 2018, the number of FTAs increased from 113 to 296, with an average annual growth rate of 6.63%. According to the latest statistics from the WTO’s RTA (Regional Trade Agreements) database, as of 2024, there are 371 FTAs in force. While the quantity continues to grow, the quality is also improving consistently. Traditional FTAs primarily focused on lowering tariffs and non-tariff barriers. However, the scope of contemporary agreements has expanded to include various areas, such as environmental protection, anti-corruption, competition policy, consumer protection, and cultural cooperation, with the depth of provisions continually increasing. The deep integration of FTAs has emerged as a new trend in global trade, profoundly impacting regional trade enhancement and reshaping global value chains (GVCs). According to the calculated data on the depth of provisions, from 2003 to 2018, the annual growth rates of the coverage index and the bindingness index for “WTO+” were 8.81 and 9.10%, respectively, while the annual growth rates for the coverage index and the bindingness index for “WTO-X” were 11.14 and 11.99%. This indicates that during this period, the depth of provisions in free trade agreements not only increased in quantity but also enhanced the legal binding force and enforceability of the provisions. In comparison, the annual growth rates of the coverage index and the bindingness index for “WTO-X” were greater. This may be attributed to rising external economic uncertainties, which have led countries to prefer signing FTAs that include deeper content to establish a stable and predictable business environment and promote economic and trade cooperation.

Amidst deep integration within GVCs, the global division of labor has shifted significantly, transitioning from inter-industry and intra-industry divisions to intra-product specialization. The ‘global production, global sales’ model within value chains has rapidly emerged. Agriculture, as a vital component of the GVC, includes not only traditional stages such as production, processing, transportation, and sales but also high value-added sectors like agricultural input supply, seed research and development, and brand building. Developed countries generally dominate the high-end segments of agricultural inputs, seeds, agro-product processing, and branding, while developing countries primarily focus on the production and export of primary agricultural products. Given that agricultural products are perishable, prone to damage, and difficult to store, along with increasingly stringent inspection and quarantine protocols and green barriers, trade in the AGVC faces numerous challenges. In this context, a pressing issue is how to enhance countries’ participation and position in the AGVC by deepening FTAs. To this end, this paper focuses on the relationship between FTA depth and GVCs, with a particular emphasis on the agricultural sector. It examines whether an increase in the depth of provisions is beneficial for enhancing a country’s participation in and division of labor within the AGVC. Additionally, it explores the underlying mechanisms from the perspectives of international trade liberalization and investment facilitation.

Research findings indicate the following: First, FTA depth significantly enhances a country’s participation and position in the AGVC, with deeper agreements yielding more pronounced effects. Second, compared to “WTO+” provisions, “WTO-X” provisions have a more substantial impact on a country’s involvement in the AGVC. Third, the effect of FTA depth on enhancing participation and position is more pronounced for developed countries than for developing countries. Fourth, FTA depth primarily improves a country’s participation degree and position in the AGVC through two channels: trade liberalization and investment facilitation. This paper aims to reveal the relationship between the depth of FTAs and the AGVC, which has significant theoretical and practical implications for countries formulating strategies, fully leveraging the opportunities presented by FTAs, and improving their positions within the AGVC.

The innovation of this paper lies in two main aspects. First, we break through the traditional assumption of homogeneity in agreements by focusing on the heterogeneity of agreement provisions, distinguishing between shallow and deep provisions, and analyzing the differential impacts of various types of provisions on a country’s participation in the division of labor within the AGVC. Second, unlike previous literature that predominantly studies the GVCs of manufacturing and services, we concentrate on the AGVC. We employ methods such as fixed effects models and PPML models to examine the impact of FTA depth on the AGVC and elaborate on the underlying mechanisms of these effects.

2 Literature review

The literature related to this paper can be categorized into three main areas: First, research on the measurement of the depth of FTAs. Scholars such as Vincentvicard (2009), Horn et al. (2010), Dür et al. (2014), and Hofmann et al. (2017) have assessed the depth of FTAs from perspectives such as the degree of integration, content and depth of provisions, and have classified the provisions accordingly. The ‘HMS method’ introduced by Horn et al. (2010) has been extensively utilized. Second, research on the effects of FTA depth. Researchers have examined how FTA depth affects value-added trade connections, OFDI (outward foreign direct investment) by Chinese enterprises, value chain trade, and a country’s involvement in GVCs (Fusacchia et al., 2022; Hanifa et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022). They have found that FTAs promote bilateral value chain activities, and this effect intensifies with deeper FTA provisions. Third, research on GVCs. Existing studies have focused primarily on two aspects: the measurement of indicators and influencing factors. Regarding measurement, scholars have assessed the degree of participation in and the position within GVCs from various perspectives, including traditional trade statistics, vertical specialization rates, the KPWW method, the VAX index, upstreamness, and backward decomposition (Hummels et al., 2001; Koopman et al., 2010; Johnson and Noguera, 2012; Fally, 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Concerning influencing factors, researchers have explored the effects of human capital, resource endowments, technological innovation, research and development investment, and institutional quality on the GVC division of labor (Li and Choi, 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Wang and Thangavelu, 2021; Ji et al., 2022; Liang and Liang, 2021; Chen and Zhang, 2023; Xu et al., 2024; Hong et al., 2020). Some scholars have also explored the impact of FTA depth on GVCs, finding that FTAs enhance bilateral value chain activities, with this effect becoming more pronounced as the depth of FTA provisions increases, particularly benefiting developing countries (Orefice and Rocha, 2014; Laget et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2022; Lee and Kim, 2022).

While these studies offer substantial theoretical and empirical evidence regarding the relationship between FTA depth and GVCs, several limitations still exist: (1) Most literature concentrates on the impact of FTA depth on the participation of the manufacturing and service sectors in GVCs, with limited research on AGVC; (2) The mechanisms through which FTA depth influences AGVC have not been thoroughly examined, particularly from the perspectives of trade liberalization and investment facilitation. In response, this paper calculates the depth of FTAs and an AGVC index, utilizing fixed effects models, PPML models, and mediation effect models to empirically analyze how FTA depth affects a country’s participation in AGVC and its underlying mechanisms. This research contributes to filling the gap in the study of FTA depth’s impact on AGVC and provides valuable theoretical and practical insights for countries formulating agricultural development strategies and enhancing international agricultural cooperation.

3 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

As technology has rapidly advanced, transportation and communication costs have significantly decreased, leading to a more refined division of labor in agriculture, which has gradually evolved into a GVC characterized by intra-product specialization (Baldwin and Yan, 2021). The segments of AGVC possess their uniqueness, with the two ends being agricultural input supply and seed research and development, as well as agricultural brand building and product marketing promotion. The middle of the value chain consists of agricultural product production and processing, among other segments. However, due to concerns over food security, countries are exhibiting a trend toward diversification in trade barriers for agricultural products. In addition to tariffs, these products also face non-tariff barriers such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical standards. The frequent trade of intermediate products has led to an accumulation of both tariff and non-tariff barriers, resulting in higher trade costs for agricultural products. Against this backdrop, the deepening of FTAs has significantly influenced a country’s participation in AGVC’s labor division.

3.1 The impact of FTA depth on the AGVC

The deepening of FTAs can significantly enhance a country’s participation and position within the AGVC. On one hand, drawing from the Comparative Advantage Theory and the Heckscher-Ohlin model, reducing trade barriers allows countries to better leverage their resource endowments in trade. Agricultural products are highly dependent on seasonal and regional production. The reduction of tariff concessions and non-tariff barriers has facilitated the cross-border flow of agricultural products, lowered the difficulty and costs for agricultural enterprises to enter international markets, and enhanced their participation in the AGVC (Melitz, 2003; Wickrama et al., 2024). The relaxation of sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS), in particular, has reduced the trade costs of agricultural products, enhanced the predictability of international markets, and promoted deeper levels of division of labor and cooperation. Trade facilitation measures, such as simplifying customs procedures and enhancing logistics infrastructure, significantly reduce the cost and time of international agricultural product transportation (Wilson and Abiola, 2003). Together, these factors make it easier for countries’ agricultural sectors to integrate into global markets, thereby increasing their participation in the AGVC.

On the other hand, deeper FTAs can strengthen a country’s position in the AGVC labor division. According to New Economic Geography and Knowledge Spillover Theory, FDI (foreign direct investment) combined with technology transfer can promote technological progress and regional economic growth. The investment protection provisions in deep FTAs can attract foreign investment into the agricultural production and processing sectors, bringing advanced agricultural technologies and management experience, thereby improving production efficiency and product quality. This enhances the position of member countries in the division of labor within AGVC. Agricultural production has a high demand for quality inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. The reduction of tariffs and the elimination of non-tariff barriers lower the import costs of these inputs, improve production efficiency and quality, and, in turn, enhance their added value position within the GVC. Moreover, FTAs encourage stronger cooperation and coordination among countries, concentrating different stages of agricultural production in areas of comparative advantage. By leveraging economies of scale and scope (Helpman and Krugman, 1987), countries can enhance their potential for technological upgrading and productivity improvements in the agricultural sectors, enabling them to ascend the GVC toward higher value-added activities while improving their positions in the AGVC. From this analysis, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Hypothesis 1. The deepening of FTAs can significantly enhance a country’s participation and position within the AGVC.

3.2 Differences in the impact of shallow and deep provisions on the AGVC

The provisions of FTAs can be categorized into shallow ‘WTO+’ provisions and deeper ‘WTO-X’ provisions, each having significant differences in their impact on the AGVC. ‘WTO+’ provisions primarily focus on additional tariff reductions, the lowering of non-tariff barriers, and enhancing transparency and consistency in trade rules. These provisions build upon and strengthen the existing WTO rules, representing traditional trade liberalization measures essential for reducing trade barriers in agricultural products. According to New Trade Theory, by streamlining export and import procedures, ‘WTO+’ provisions facilitate the integration of member countries into GVCs. However, since these provisions concentrate mainly on tariffs and non-tariff measures, their impact is relatively limited, with the primary effect being improved market access rather than deeper AGVC integration. Based on the Melitz model, the influence of these provisions on enhancing productivity, technological advancement, and value-added in the agricultural sector is relatively small, thus having a limited impact on enhancing a country’s position in AGVC (Jordan, 2017; Eum, 2023).

In comparison, ‘WTO-X’ provisions tackle more complex issues that extend beyond the scope of WTO agreements, such as intellectual property rights, labor standards, competition policy, and agricultural investment protection. These provisions not only influence market access for agricultural products but also have profound effects on the structure of the agricultural industry, technological innovation, and the institutional environment. According to New Economic Geography and the Theory of Knowledge Spillovers, ‘WTO-X’ provisions can significantly enhance productivity and international competitiveness in the agricultural sector by attracting FDI, promoting technology transfer, and improving institutional quality. The protection of intellectual property rights for seeds, varieties, and technologies in the agricultural sector is strengthened through FTAs, which encourage agricultural innovation and the establishment of high-quality brands, enabling agricultural enterprises to occupy a position of higher added value in the GVC (Grossman and Helpman, 1991). Moreover, based on Transaction Cost Theory, these deeper provisions help create a more stable and predictable business environment, reducing agricultural transaction costs and further boosting the agricultural sector’s participation in the AGVC. From this, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Hypothesis 2. Increasing the depth of ‘WTO-X’ provisions has a more significant positive effect on participation and position within the AGVC compared to increasing the depth of ‘WTO+’ provisions.

3.3 Mechanisms through which the depth of FTAs affects the AGVC

The depth of FTAs influences a country’s participation and position within the AGVC by promoting trade liberalization and facilitating investment.

First, the deepening of FTAs encourages agricultural investment and trade between member countries by fostering trade liberalization and investment facilitation. FTAs have significantly promoted the liberalization of agricultural trade by reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers, thereby lowering the costs and obstacles associated with agricultural trade. The deepening of FTAs signifies that international trade rules will become more detailed and unified, helping to reduce the implicit costs incurred by both parties in coordinating agricultural trade and promoting the trade of agricultural products among member countries. In terms of investment facilitation, the depth of FTAs has a significant impact. FTAs typically include specific provisions related to investment, such as simplifying investment application and approval procedures, ensuring transparency in investment information and policy regulations, providing clear channels for complaints, and establishing comprehensive dispute resolution mechanisms. These measures have enhanced the transparency and predictability of cross-border investments, directly facilitating the development of agricultural investment (Chi, 2002). Furthermore, Osnago et al. (2019) also pointed out that deeper trade agreements positively affect the growth of FDI.

Second, trade liberalization can effectively enhance a country’s participation and position within the AGVC. Agricultural products must comply with strict SPS standards. The liberalization of trade has led to greater coordination and unification of these standards, which helps reduce trade friction caused by discrepancies and encourages countries to engage in the AGVC. According to the Theory of Technology Diffusion, trade liberalization creates favorable conditions for the cross-border dissemination of advanced agricultural technologies and management practices. For instance, advanced agricultural machinery and biotechnology from developed countries can more readily enter the markets of developing countries through free trade. The introduction and application of technology not only enhance production efficiency and quality but also drive the upgrading and structural adjustment of the agricultural value chain, thereby strengthening countries’ positions within the GVC. Finally, investment facilitation can also effectively enhance a country’s participation and position within the AGVC. According to the Eclectic Theory (Dunning, 1977), investment facilitation promotes outbound agricultural investments, which is a crucial pathway for countries to be involved more deeply in the AGVC. By making outbound agricultural investments, countries can relocate non-competitive production stages abroad, optimize resource allocation, and concentrate on competitive agricultural production activities, thereby increasing the international competitiveness of agricultural products. Furthermore, based on Endogenous Growth Theory, investment facilitation attracts more foreign capital into the country, bringing valuable resources such as funds, technology, and knowledge. The influx of these resources significantly enhances agricultural production efficiency and product quality, thereby promoting the country’s position within the AGVC. Building on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3. Trade liberalization and investment facilitation serve as the primary channels through which FTA depth significantly influences the participation and position of a country in the AGVC.

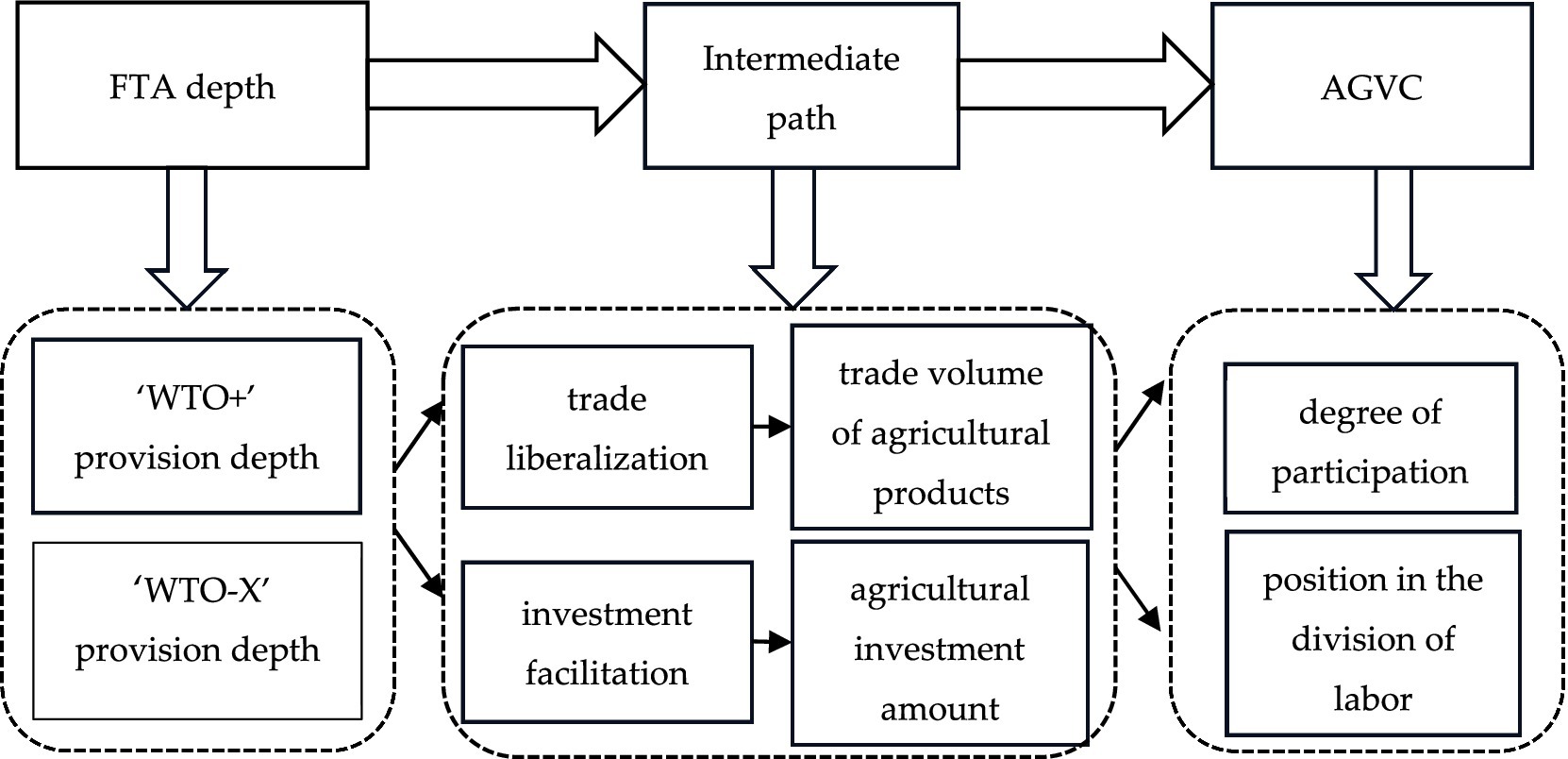

In summary, compared to the manufacturing and service sectors, AGVC demonstrates greater regional specificity, perishability of products, and an emphasis on primary products in relation to the depth of FTAs. Consequently, FTAs with greater depth can more effectively promote the international circulation of agricultural products, enhance the competitiveness of processing and value-added segments, and facilitate the transition from primary production to higher value-added stages, securing a more advantageous position within GVC. Furthermore, deep FTAs strengthen the participation of agricultural enterprises in the AGVC. Trade liberalization and investment facilitation serve as significant channels for these impacts, with their mechanisms illustrated in Figure 1.

4 Methodology and data

4.1 Econometric model specification

4.1.1 Fixed effects model

To thoroughly explore the effect of FTA depth on member countries’ participation degree and division of labor position within the AGVC, this paper constructs the following model:

Equation 1 employs the AGVC Participation Index as the dependent variable, concentrating on how provision depth affects AGVC participation. Equation 2 utilizes the AGVC Position Index as the dependent variable, investigating the impact of provision depth on the position within the AGVC. Here, i signifies the country, and t indicates the year. Four indices—coverp (WTO+ coverage), bindingp (WTO+ bindingness), coverx (WTO-X coverage), and bindingx (WTO-X bindingness)—constitute the explanatory variable, Depth. To more accurately assess the effect of FTA depth on both participation degree and position within the AGVC, this paper integrates several key control variables into the econometric model. These include the level of economic development ( ), human capital ( ), physical capital ( ), institutional quality ( ), labor compensation rate ( ), and technological development level ( ). Adding these control variables ensures greater robustness in the empirical results. Additionally, represents country fixed effects and year fixed effects, while denotes the random error term.

4.1.2 Examination of the influence mechanism

This paper posits in the theoretical analysis section that FTA depth influences the division of labor in the AGVC through two pathways: trade liberalization and investment facilitation. The impacts of trade liberalization and investment facilitation on participation levels and the division of labor in the AGVC have been widely validated (Wang and Thangavelu, 2021; Morrissey and Filatotchev, 2000; Javorcik, 2004). However, the effect of FTA depth on promoting trade liberalization and investment facilitation warrants further examination. This paper draws on the approaches of Cheng and Dong (2024), Wang et al. (2024), and Ren et al. (2023) to construct the following model for empirical testing of the influence mechanism:

Equations 3–6 are employed to examine the mechanisms through which the depth of FTAs influences the degree of participation and position within the AGVC. Specifically, Equation 3 assesses the impact of FTA depth on participation degree in the AGVC, while Equation 4 explores the effect of FTA depth on position within the AGVC. Equations 5 and 6 are then utilized to evaluate the influence of FTA depth on trade liberalization and investment facilitation. Finally, from a theoretical standpoint, we analyze the mediating effects of trade liberalization and investment facilitation on participation degree and position within the AGVC.

4.2 Variable measurement and selection

4.2.1 Explanatory variable

In this paper, the explanatory variable is FTA depth, which is referred to as ‘Depth’. Hofmann et al. (2017) quantified the content of FTAs to measure the heterogeneity of their depth and constructed both a total depth index and a core depth index. Subsequently, the World Bank released the Content of Deep Trade Agreements database, which employed a similar method to calculate the horizontal depth of FTA provisions, categorizing them into four categories: WTO + AC, WTO + LE, WTO-X AC, and WTO-X LE. Among these, WTO + AC and WTO-X AC assess the coverage of FTAs, while WTO + LE and WTO-X LE consider the legal binding nature of the provisions within the agreements.

Drawing on the methodology developed by Hofmann et al. (2017), this paper quantifies FTA provisions and constructs two types of indicators to measure the depth of the agreements. The first type is the ‘coverage index’, which measures the number of provisions in a specific trade agreement, while the second type is the ‘bindingness index’, which evaluates the strength of these provisions concerning dispute resolution mechanisms and legal enforceability. According to Horn et al. (2010), existing FTA provisions are categorized into “WTO+” provisions (14 items) and “WTO-X” provisions (38 items). Among these, ‘WTO+’ provisions fall within the existing WTO framework, such as tariff reduction, while ‘WTO-X’ provisions extend beyond the framework of WTO, addressing areas like intellectual property protection. Calculate the coverage index and the bindingness index separately for the two types of provisions using the following methods:

The first step is to calculate the coverage index. FTA provisions are coded 1 if present and 0 if absent. The scores for all provisions are then summed and subsequently divided by the total number of provisions to obtain the coverage index for a given FTA. This paper calculates the ‘WTO+ coverage index’ (coverp) and the ‘WTO-X coverage index’ (coverx) by distinguishing between ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provisions. The formulas for these calculations are as follows: , . Next is the calculation of the bindingness index. If a provision is neither explicitly mentioned in the FTA nor legally binding, it receives a value of 0. If the provision is explicitly stated and legally binding, yet not included in the dispute settlement mechanism, it is given a value of 1. If explicitly mentioned, legally binding, and included in the dispute settlement mechanism, it receives a value of 2. Similarly, the WTO+ bindingness index (bindingp) and the WTO-X bindingness index (bindingx) are calculated by summing all provisions’ scores and dividing by the total number of provisions. The formulas for these calculations are as follows: , .

4.2.2 Dependent variables

The dependent variables of this paper are the AGVC Participation Index (GVC_Pat) and the AGVC Position Index (GVC_Pos). Drawing on the KPWW method, this paper uses data from the TiVA database for calculating the AGVC Participation and Position indices for 64 economies from 2003 to 2018. The TiVA database was jointly released in 2013 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), utilizing the World Input–Output Database (WIOD). This database conducts statistical analyses of trade activities from the perspective of value added, thus avoiding issues like double counting that are present in traditional trade statistics. The current TiVA database covers data from 76 economies, 17 countries and regional groups, as well as 45 industries including agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishing, mining, and manufacturing. This paper selects data from six industries within the agricultural sector, including agriculture, hunting, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture, based on industry codes. It excludes certain economies with significant amounts of missing values and generates a new variable based on country IDs and industry codes. The indices of participation and position in the AGVC presented in this paper more accurately reflect the value-added gains of various countries engaged in agricultural trade, allowing for an assessment of their degree of participation and position within the AGVC.

The formula for calculating the AGVC Participation Index is as follows:

In Equation 7, represents a specific industry, denotes a particular country, refers to the indirect value-added exports of industry in country to other countries, i.e., the value of exports from intermediate product trade. indicates the foreign value-added content in the exports of industry in country , i.e., the value of imports from intermediate product trade. stands for the total exports of industry in country , measured in the terms of value-added. represents the forward participation index ( ), which measures the proportion of indirect value-added exports to total exports for industry in country . This ratio directly reflects the degree of forward participation in the AGVC. A higher value indicates greater participation in the AGVC through intermediate product or service exports, and a stronger position in the value chain. denotes the backward participation index ( ), representing the proportion of foreign value-added content to total exports for industry in country . A higher value suggests that the country relies more on intermediate products from other countries, indicating a relatively lower position in the GVC. The AGVC Participation Index is calculated by summing the forward and backward participation indices.

The formula for calculating the AGVC Position Index is as follows:

Equation 8 illustrates that when the share of indirect value-added exports in total exports surpasses that of foreign value-added content, the AGVC Position Index will be positive. This signifies that a country primarily engages in the AGVC by exporting intermediate products to other nations, indicating a relatively higher standing in the value chain. Conversely, if the proportion of IV is less than that of FV, the AGVC Position Index will be negative. This implies that the country, lacking advantages in areas such as technology and innovation, participates in the AGVC mainly by importing intermediate products or services from other nations, placing it lower in the value chain and further downstream in labor division, without significant competitive advantages.

4.2.3 Control variables

Leveraging current research (Baier and Bergstrand, 2007; Zhang et al., 2021), this paper integrates variables that influence AGVC as control variables into the model. The specific control variables are as follows: Economic development level (GDP): Measured using each country’s GDP (in constant 2015 US dollars). Generally, developed countries tend to occupy upstream positions in GVCs (Mudambi, 2008; Shin et al., 2012). Human capital (human): Represented by the education index from the Human Development Index, which combines both male and female education indices. Human capital is essential for driving economic growth in a country, and increasing investment in it contributes to enhancing the technological complexity of exports (Sun et al., 2024), which in turn affects the country’s AGVC participation and position. Physical capital (material): Measured by the ratio of gross fixed capital formation in relation to GDP. Countries with abundant physical capital have greater advantages in global competition, which may influence their participation and position in the AGVC (Ji et al., 2022). Institutional quality (system): Measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators. High-quality institutions can lower the costs of international trade, minimize resource misallocation, and provide clear social signals (Hou et al., 2020). Labor compensation rate (labsh): Represented by the share of labor compensation in GDP. An increase in labor compensation in a specific industry can attract more talent to that industry, fostering further development and potentially influencing its position in the GVC. Technological development level (technology): Measured by the count of scientific journal articles published in a country. Improvements in technological research and development significantly promote industrial development and upgrading, increasing the added value of products and ultimately helping the country move upstream in the GVC (Xu et al., 2024).

4.3 Data sources and descriptive statistical analysis

Data for measuring the AGVC participation index and position index come from the TiVA database. Data for the FTA depth index is sourced from the World Bank’s ‘Content of Deep Trade Agreements’ database. Control variable data are sourced as follows: economic development level (GDP), physical capital (material), and institutional quality (system) are taken from the World Bank database. Human capital (human) data is derived from the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) ‘Human Development Report’. Labor compensation rate (labsh) data comes from the Penn World Table database, while technological development level (technology) is derived from the World Bank’s WDI database. Taking into account the time span of the various data variables, this paper sets the research period from 2003 to 2018.

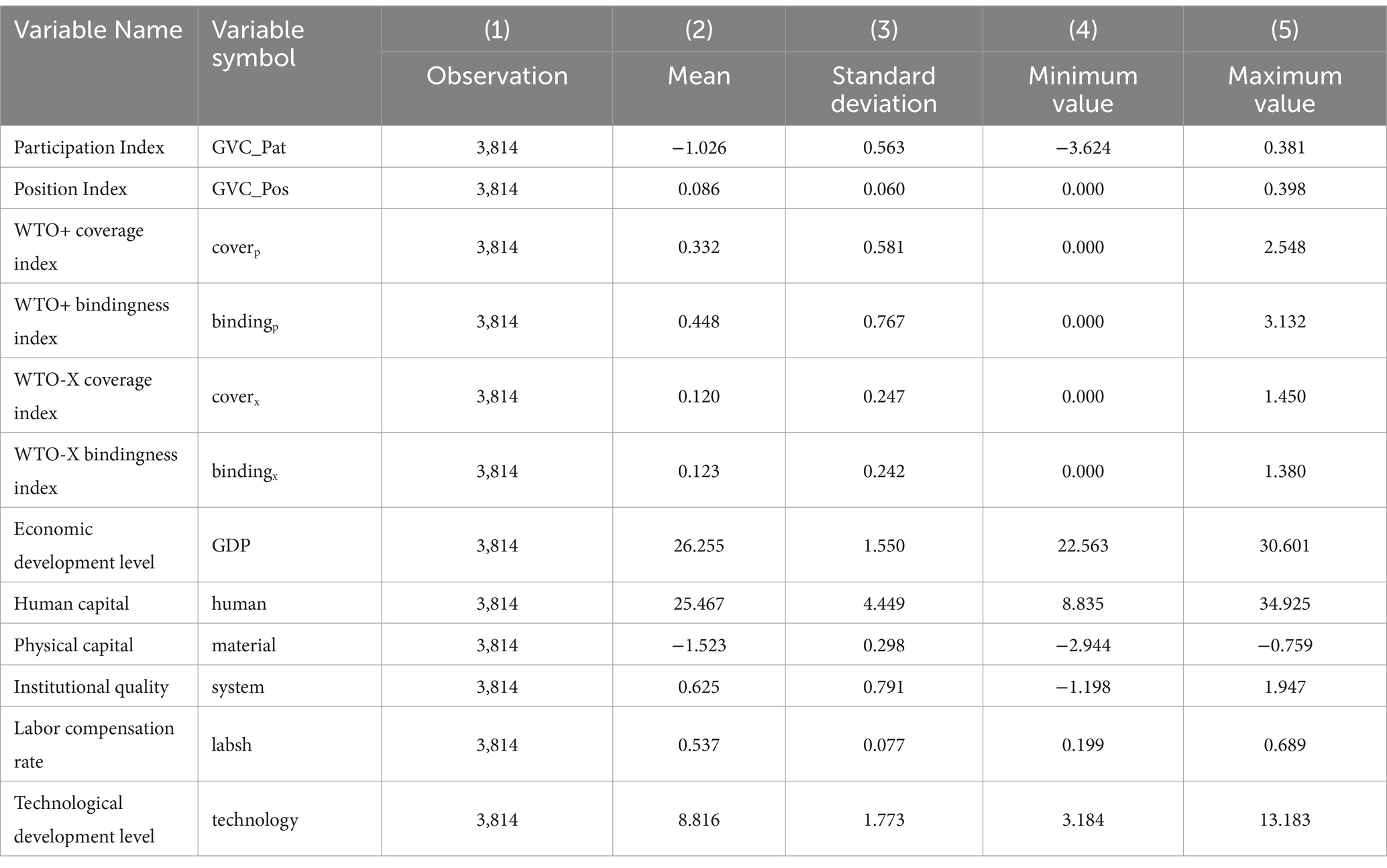

Considering the significant differences in data among the variables, logarithmic transformations were applied to the two dependent variables, four explanatory variables, and the control variables: economic development level (GDP), physical capital (material), and technological development level (technology). This approach was adopted to reduce data discrepancies, mitigate volatility, and eliminate potential extreme value effects. Table 1 shows that the sample size for this paper is 3,814 observations. Human capital has the largest standard deviation, at 4.449, indicating a relatively dispersed distribution. The standard deviations of GDP, institutional quality, and technological development level are also relatively large, primarily due to significant disparities among countries in these areas.

5 Results

5.1 Basic regression results analysis

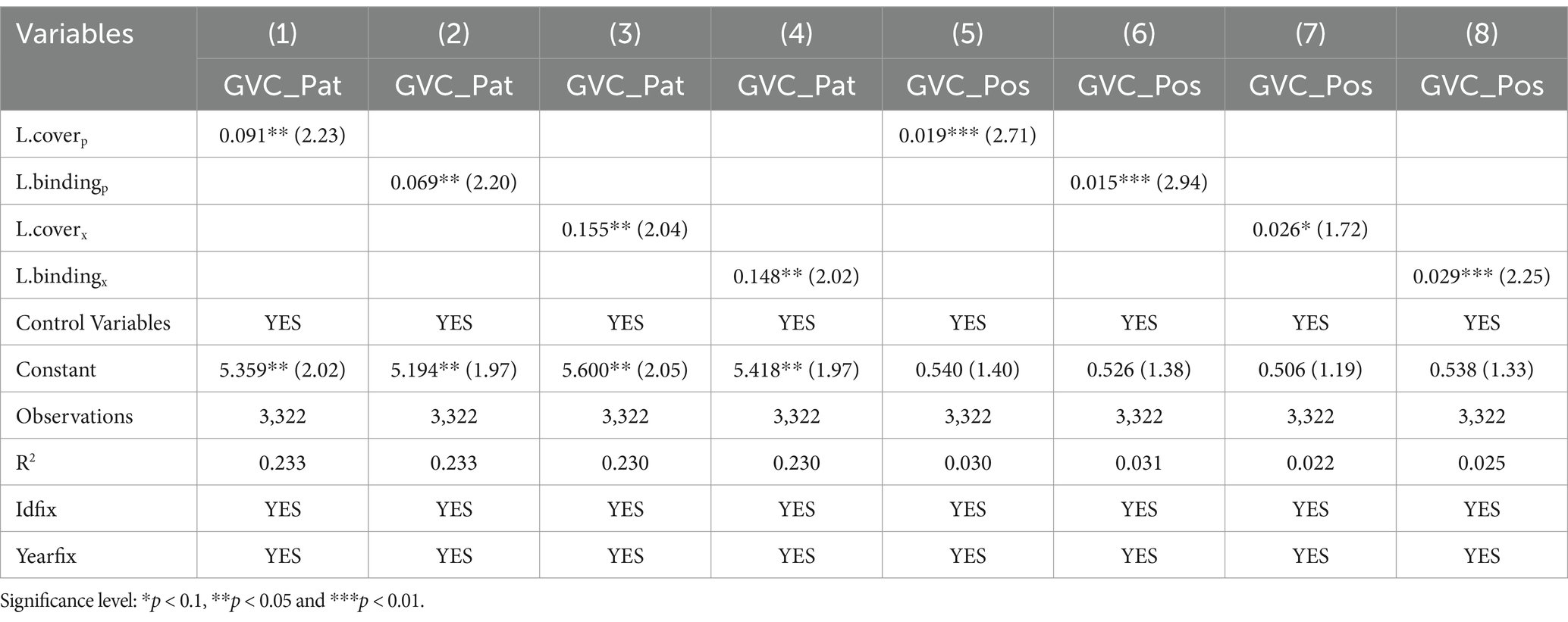

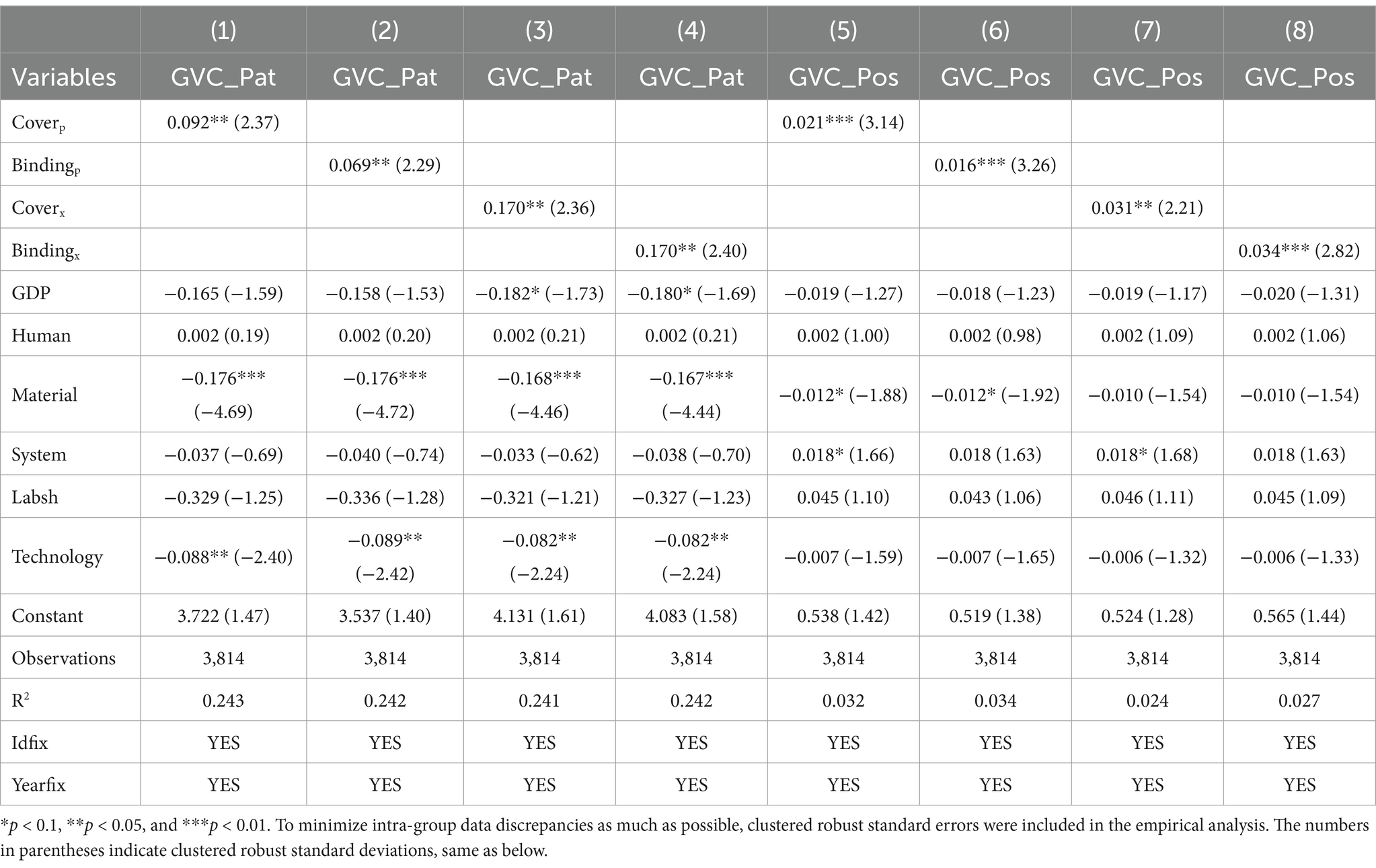

Using a two-way fixed effects model, this paper estimates Equations 1 and 2 to examine how the depth of ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provisions in FTAs affects the participation and position in the AGVC. Table 2 presents the results. Columns (1), (2), (3), and (4) show the effects of the coverage index and bindingness index of ‘WTO+’ provisions, as well as the coverage index and bindingness index of ‘WTO-X’ provisions, on the AGVC participation index, respectively. Columns (5) through (8) correspondingly display the effects of these indicators on the AGVC position index. The results indicate that, across all columns, the coefficients for the respective provision depth indices are positive and at the 5% significance level or higher, suggesting that the increasing depth of FTA provisions significantly enhances a country’s participation and position within the AGVC. This finding supports Hypothesis 1.

Table 2. The impact of different levels of FTA depth on a country’s AGVC participation and position.

Further comparison of the impacts of different provision depth indices reveals that, in Columns (1) and (3), as well as Columns (5) and (7), the coefficients of the ‘WTO+’ provision coverage index are smaller than those of the ‘WTO-X’ provision coverage index. This suggests that, compared to ‘WTO+’ provisions, the coverage of ‘WTO-X’ provisions has a more significant impact on promoting participation and position in the AGVC. Similarly, in Columns (2) and (4), as well as Columns (6) and (8), the coefficients of the ‘WTO+’ provision bindingness index are also smaller than those of the ‘WTO-X’ provision bindingness index. This further demonstrates that the depth and bindingness of ‘WTO-X’ provisions have a more pronounced effect on enhancing a country’s position in the AGVC. These results confirm Hypothesis 2, which states that the depth of ‘WTO-X’ provisions strongly influences the enhancement in a country’s participation and position in the AGVC compared to ‘WTO+’ provisions. This may be because ‘WTO-X’ provisions encompass broader areas, such as environmental protection, intellectual property, and competition policy, which can more effectively promote institutional improvements and international cooperation in the agricultural sector, thereby further advancing the development of the AGVC.

Regarding the control variables, both physical capital and technological development levels negatively impact participation in the AGVC significantly at the 5% significance level. This could be because countries with higher economic development levels and greater physical capital possess stronger capabilities in autonomous production and technological innovation, leading to less reliance on foreign markets and external resources, thus reducing their participation in the GVC. Furthermore, according to the ‘smile curve’ theory, countries engaged in research and design tend to occupy higher positions in the GVC and obtain greater added value. These countries may strengthen intellectual property protection and restrict the spillover of core technologies, thereby reducing their participation in the GVC (Ming et al., 2015). At the 5% significance level, no significant effect on the division position within the AGVC is demonstrated by any of the control variables. This may be due to the heterogeneous effects of these control variables on different countries: for developed countries, these variables may enhance their division position in the AGVC, while for developing countries, they may exert a suppressing effect. This hypothesis will be further tested in the subsequent heterogeneity analysis.

5.2 Addressing endogeneity with the instrumental variable approach1

FTAs may present endogeneity issues (Baier and Bergstrand, 2007), which must be addressed. On one hand, the in-depth development of FTA provisions may facilitate a country’s improved participation in the division of labor within the AGVC. On the other hand, to promote the circulation of elements such as products and services and to establish a more stable and predictable business environment, economies may be more inclined to sign comprehensive FTAs to better integrate into the AGVC. Therefore, there may be a reverse causal relationship between the depth of FTAs and a country’s participation in the division of labor within the AGVC, leading to endogeneity issues. To address the aforementioned endogeneity issue, this paper draws on relevant literature and employs the average depth of FTAs signed by all other countries in the sample in year t, lagged by two periods, excluding one specific country as an instrumental variable. A two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression analysis is conducted (Cheng et al., 2016). Taking the coverage index of ‘WTO+’ provisions as an example of the instrumental variable, the calculation formula is as follows:

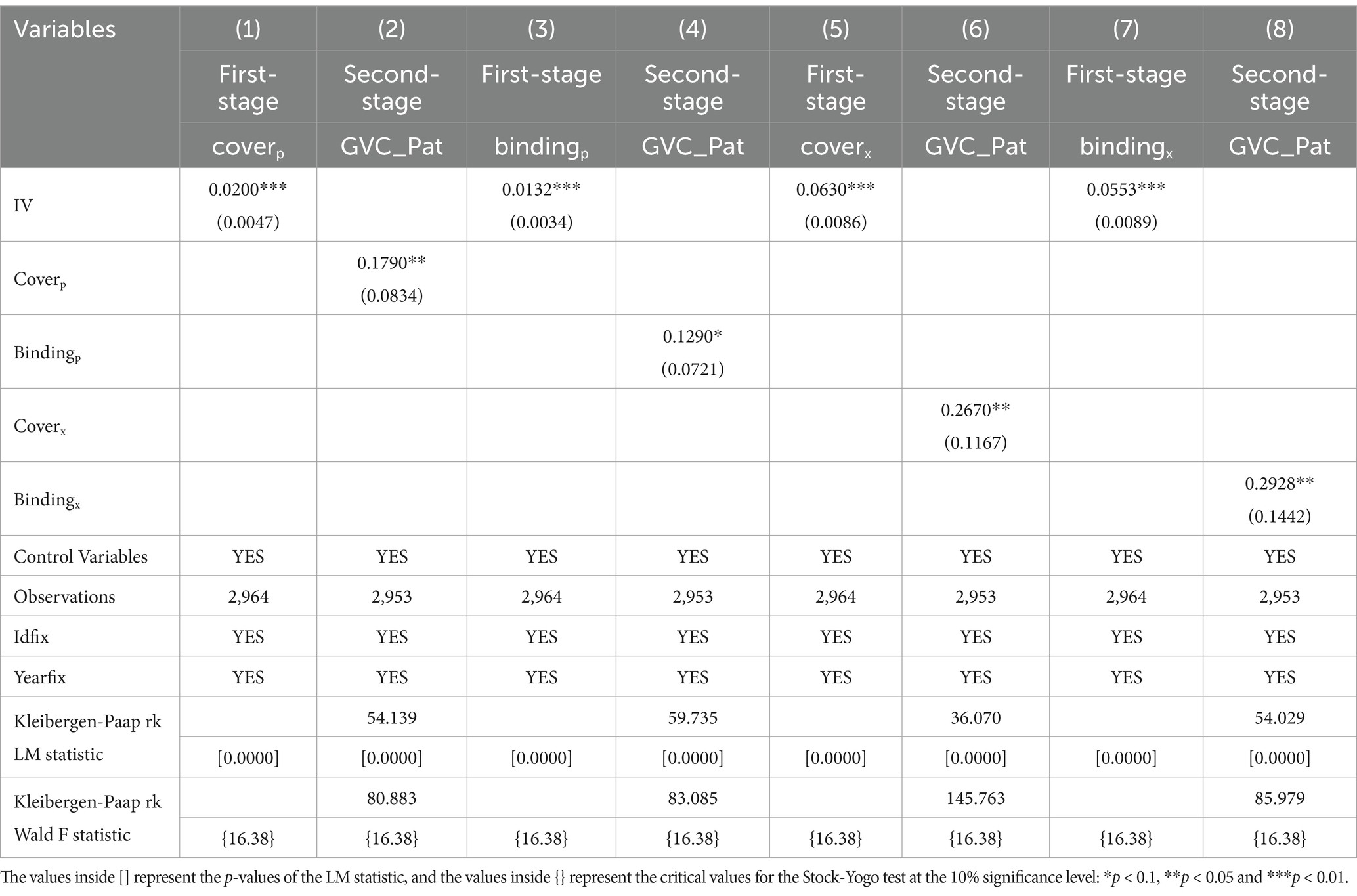

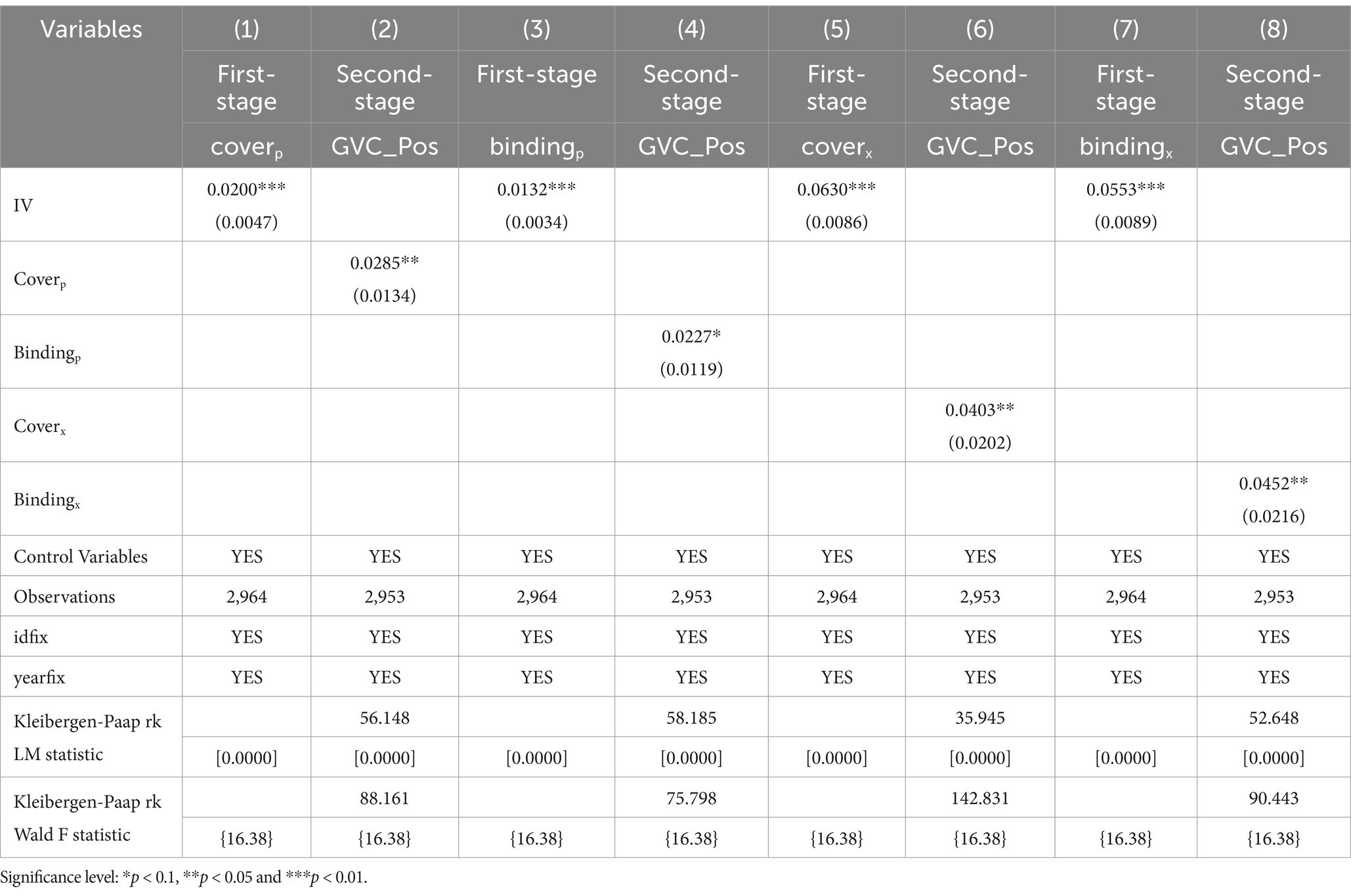

Where represents the sum of the coverage index of ‘WTO+’ provisions in the FTAs signed by all other countries in the sample, excluding country i, for year t-2, while denotes the number of all other countries in the sample, excluding country i, for year t-2. This paper posits that the instrumental variable may influence the depth of FTAs in the current period. If the signing of deep FTAs in the past 2 years has yielded positive outcomes and fostered economic and trade cooperation between countries, there may be a greater inclination to sign additional deep FTAs or strengthen existing agreements in the future. This effect is particularly pronounced when the other countries in the sample are partner countries of country i, leading to a more significant enhancement of FTA depth. On the other hand, the instrumental variable is not related to the degree of participation and division of labor among various countries in the AGVC during the current period. In addition, this paper examines the issues of insufficient identification and weak instruments related to instrumental variables. The identification test (e.g., the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic) rejects the null hypothesis regarding the lack of relevance of the instrumental variables, while the weak instrument test (e.g., the Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic) indicates that there are no issues with weak instruments. The results of these tests confirm the validity of the selected instrumental variables, which are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. After introducing the instrumental variables, the regression coefficients of the four core explanatory variables on participation degree in the AGVC and the division of labor remain positive and statistically significant. This indicates that, after accounting for endogeneity, FTA depth continues to have a significant promoting effect on both the degree of participation in and the enhancement of position within the AGVC. These findings are consistent with the baseline regression results and demonstrate strong robustness.

5.3 Robustness test

5.3.1 Lagging the Core explanatory variables by one period

In this paper, the one-period lag of FTA depth is utilized as an instrumental variable in the regression analysis, which incorporates country-year two-way fixed effects. Table 5 displays the results. As shown, Columns (1), (2), (5), and (6) report the regression results of the one-period lag of the ‘WTO+’ coverage index and bindingness index on participation and position in the AGVC, respectively. The coefficients are statistically significant and positive at the 5% level or higher. Columns (3), (4), (7), and (8) report the regression results for the one-period lag of the ‘WTO-X’ coverage index and bindingness index, with similarly positive and significant coefficients. These findings confirm the robustness of the baseline regression results.

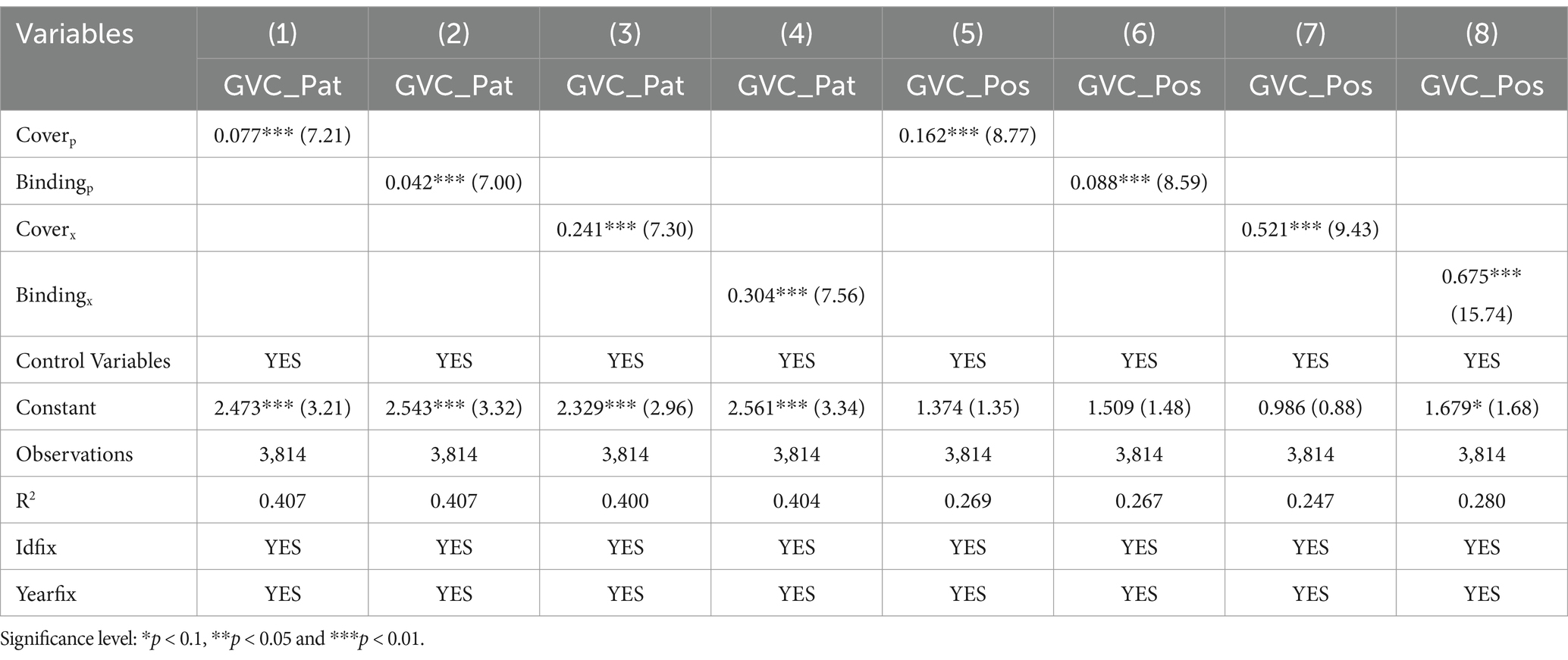

5.3.2 Changing the regression method

This paper re-estimates Models (1) and (2) using the Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood (PPML) method to further assess the robustness of the baseline regression results. The PPML method is well-suited for handling zero values in dependent variables and correcting heteroskedasticity, making it particularly appropriate for trade data analysis. Table 6 displays the regression outcomes, indicating that Columns (1), (2), (5), and (6) reflect the impact of the ‘WTO+’ coverage index and bindingness index on the degree of AGVC participation and division position, respectively, with coefficients that are both positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. Likewise, Columns (3), (4), (7), and (8) present the regression results for the ‘WTO-X’ coverage index and bindingness index, which display coefficients that are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. These findings imply that employing the PPML method does not change the conclusions of the baseline regression. The depth of FTAs continues to significantly enhance participation and position in the AGVC, further confirming the robustness of the results.

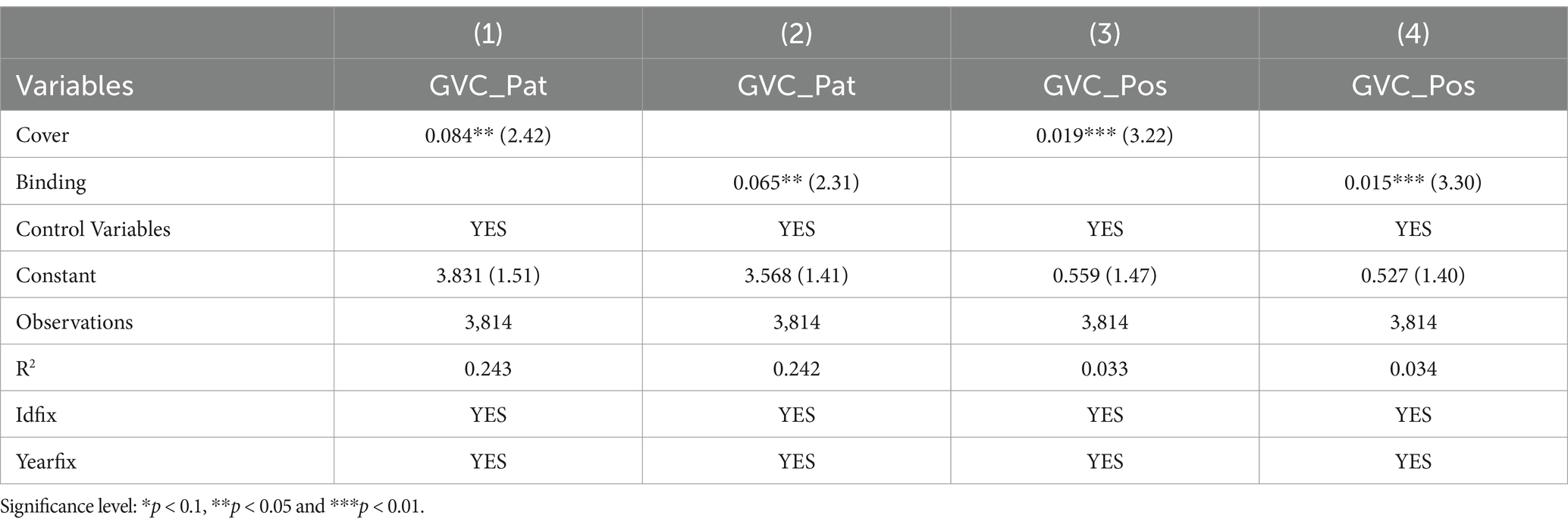

5.3.3 Modifying the measurement method for Core explanatory variables

To assess whether the conclusions are affected by altering the measurement method for the core explanatory variables, this paper recalculates the overall coverage and bindingness indices of FTAs without distinguishing ‘WTO+’ from ‘WTO-X’ provisions and re-estimates the Models (1) and (2). Table 7 presents the results. Columns (1) and (2) report the regression results for the overall coverage and bindingness indices on the participation degree in the AGVC, showing coefficients that are positive and significant at the 5% level. Columns (3) and (4) report the regression results for these indices on the division position in the AGVC, with similarly positive and significant coefficients. These findings suggest that even after modifying the measurement method for the core explanatory variables, FTA depth continues to positively affect both participation and position in the AGVC significantly, further confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

5.4 Heterogeneity test

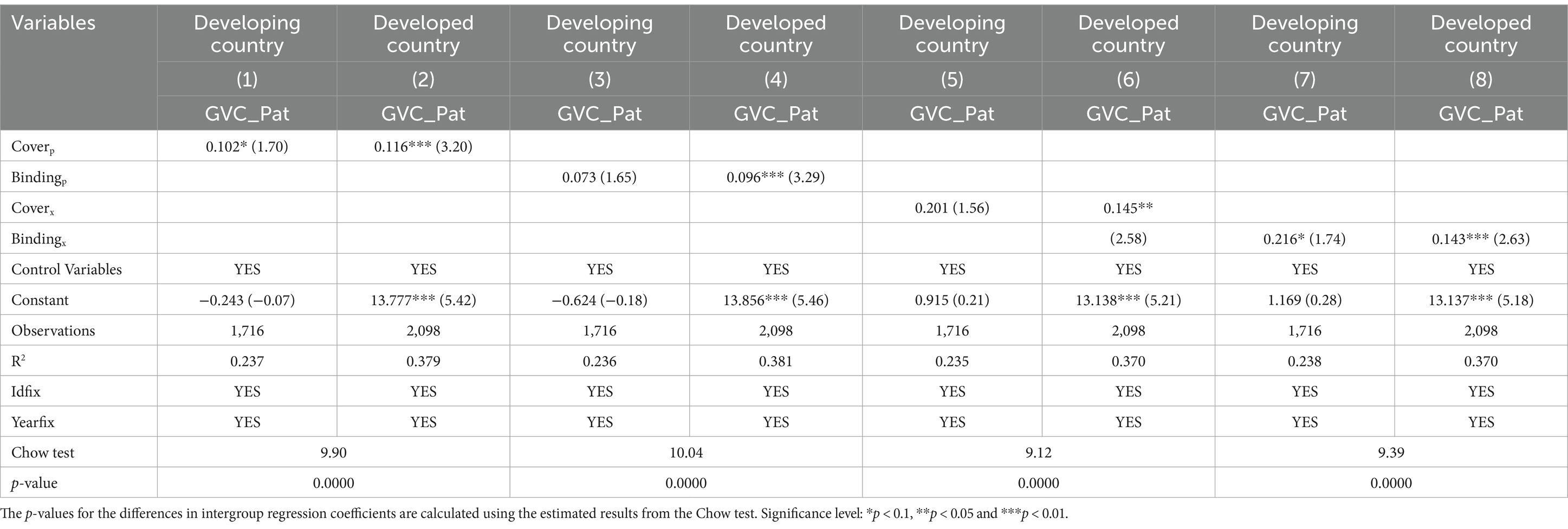

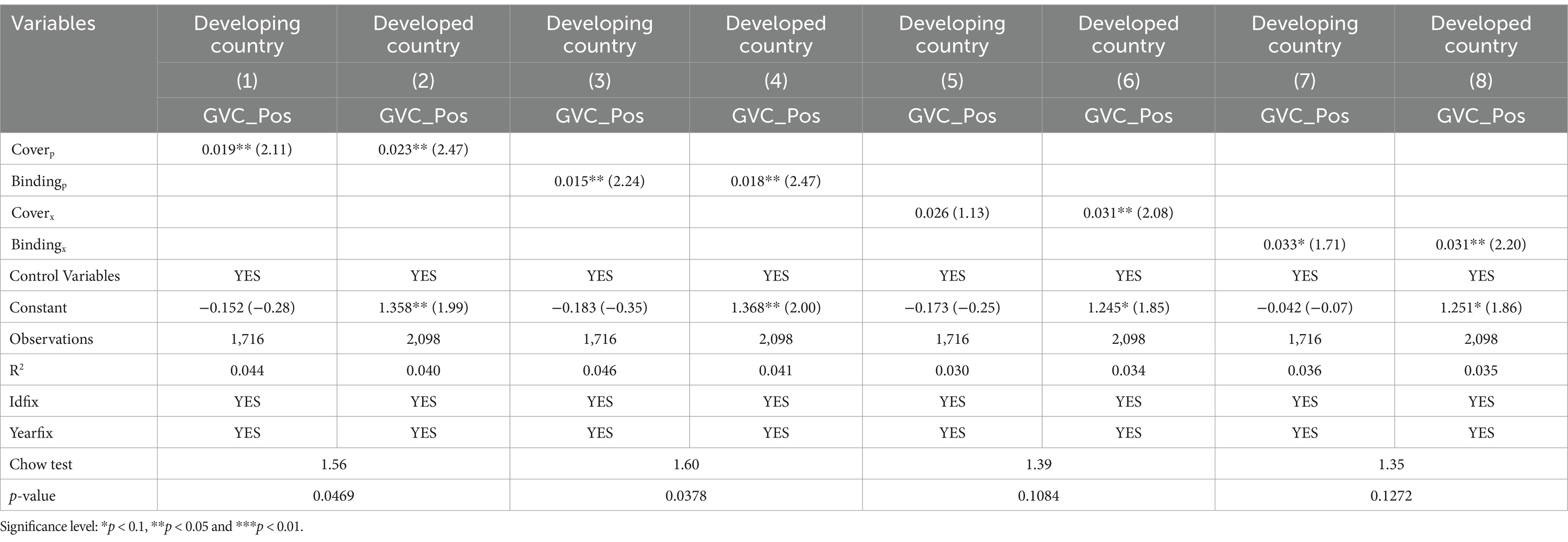

To further investigate the variation in the impact of FTA provision depth on the participation of different economies in the AGVC, a subgroup regression analysis was performed. The findings are reported in Tables 8, 9. For AGVC participation, Table 8 shows that the regression coefficients of the ‘WTO+’ coverage and bindingness indices, as well as the ‘WTO-X’ coverage and bindingness indices, in Columns (1), (3), (5), and (7) are generally not significant, with only a small number of coefficients reaching the 10% significance level. This implies that the FTA provision depth only affects developing countries’ AGVC participation to a limited extent. In contrast, regression coefficients of all core explanatory variables in Columns (2), (4), (6), and (8) are positive and significant at the 5% level or higher. This suggests FTA provision depth greatly enhances developed countries’ participation in the AGVC, with ‘WTO-X’ provisions having a relatively stronger impact. To verify the robustness of these results, a Chow test was conducted to examine the differences in regression coefficients between groups. The results reveal that the p-values for all four regressions are significant, indicating that the differences in coefficients between developing and developed countries are statistically significant. These findings suggest that, compared to developing countries, FTA provision depth has a more pronounced effect on boosting developed countries’ participation in the AGVC.

Regarding the AGVC position, the results in Table 9 indicate that Columns (1) and (3) present regression results for the ‘WTO+’ coverage index and bindingness index on the position of developing countries in the AGVC, with positive coefficients that are at the 5% significance level. Columns (5) and (7) display the influence of the ‘WTO-X’ coverage and bindingness indices, where the coefficients show weaker significance, with a few reaching the 10% level of significance. Overall, the regression coefficients for the core explanatory variables show limited statistical significance, indicating that FTA provision depth has only a limited influence on enhancing developing countries’ position in the AGVC. Conversely, in Columns (2), (4), (6), and (8), the core explanatory variables’ regression coefficients are all statistically significant and positive at the 5% level. This suggests that FTA provision depth significantly enhances the position of developed countries in the AGVC. Comparing Columns (1) and (2), (3) and (4), (5) and (6), (7) and (8), it is evident that the overall regression coefficients for developed countries are larger. The Chow test results show that the p-values for the two groups concerning ‘WTO+’ provision depth are significant, while the p-values for the two groups regarding ‘WTO-X’ provision depth are not significant. This could be because ‘WTO-X’ provisions involve rules that extend beyond the current WTO framework, which are not yet widely reflected in FTAs, and the degree of development is limited. Therefore, the coefficient differences between developing and developed countries are not significant.

In summary, increasing the FTA provision depth has a greater impact on enhancing developed countries’ participation and position in the AGVC compared to developing countries. This is due to the fact that developed countries are often the advocates of FTAs and the creators of new trade rules, enabling them to embed their interests more effectively in the agreements. Developed countries, with their advanced agricultural technologies and well-established industrial chains, are better positioned to seize the opportunities presented by FTAs to deepen their participation in the GVC.

5.5 Mechanism test

To further investigate Hypothesis 3 proposed earlier, this paper conducts a mechanism analysis from the perspectives of trade liberalization and investment facilitation.

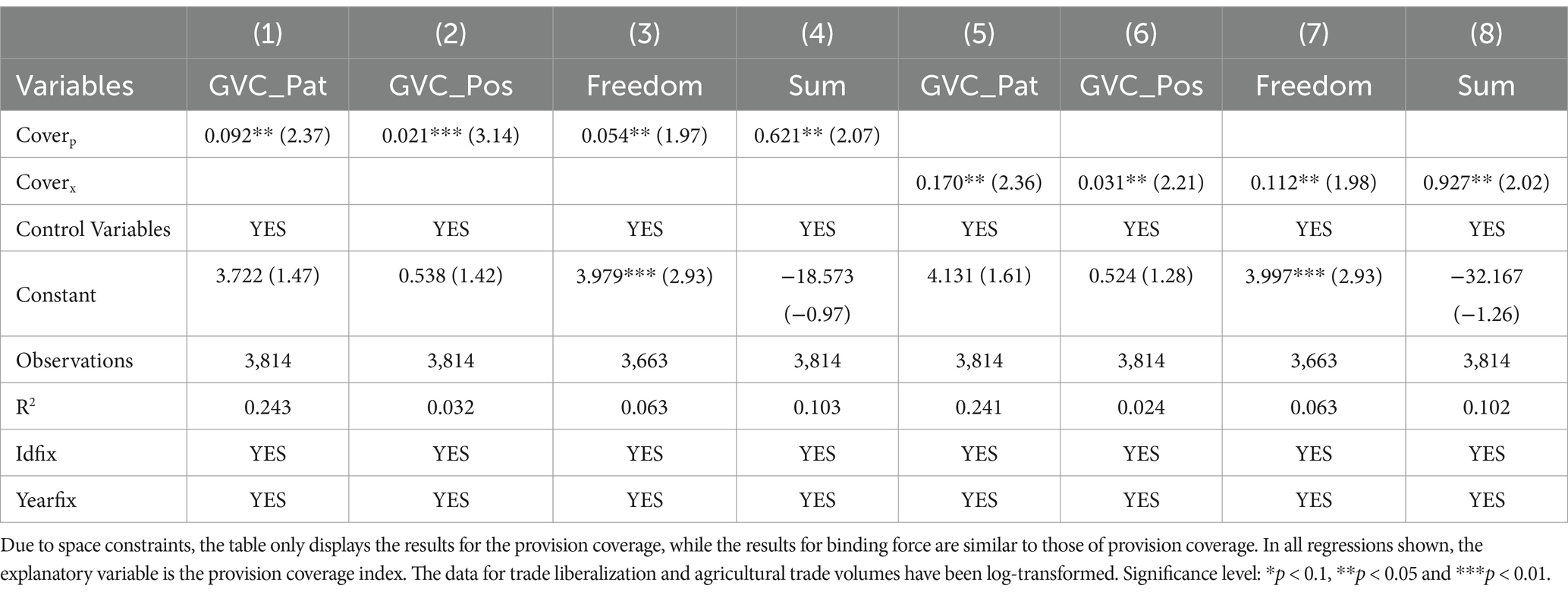

5.5.1 Examination of the trade liberalization mechanism

First, we analyze the mechanism through which the depth of FTAs affects a country’s participation and position in the AGVC via trade liberalization. The regression results are shown in Table 10. Columns (1) to (4) display the effects of the ‘WTO+’ provision coverage index (coverp) on AGVC participation degree, division position, trade liberalization level, and agricultural trade volume, with all showing positive and statistically significant coefficients. Similarly, Columns (5) through (8) present the regression results for the ‘WTO-X’ provision coverage index (coverx), which also exhibit positive and significant coefficients. These results indicate that increasing the coverage indices of ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provisions in FTAs promotes international trade liberalization, facilitates trade exchanges among countries, and boosts a country’s agricultural trade volume. Previous research has confirmed that enhanced trade liberalization benefits the expansion of agricultural trade (Fan et al., 2022; Xin et al., 2024). An increase in agricultural imports enhances a country’s backward participation in the GVC. An increase in agricultural exports indicates that the country exports more raw materials or intermediate products, thereby boosting its forward participation. Higher agricultural trade volume signifies more frequent trade activities and stronger connections with the GVC. In particular, the expansion of intermediate product trade can enable a country to integrate more deeply into the division of labor within the GVC (Feyaerts et al., 2019). Additionally, trade liberalization creates favorable conditions for the cross-border transfer of advanced agricultural technologies and management practices, which are crucial for enhancing a country’s position within the GVC division (Wang and Thangavelu, 2021). In summary, Hypothesis 3 is validated.

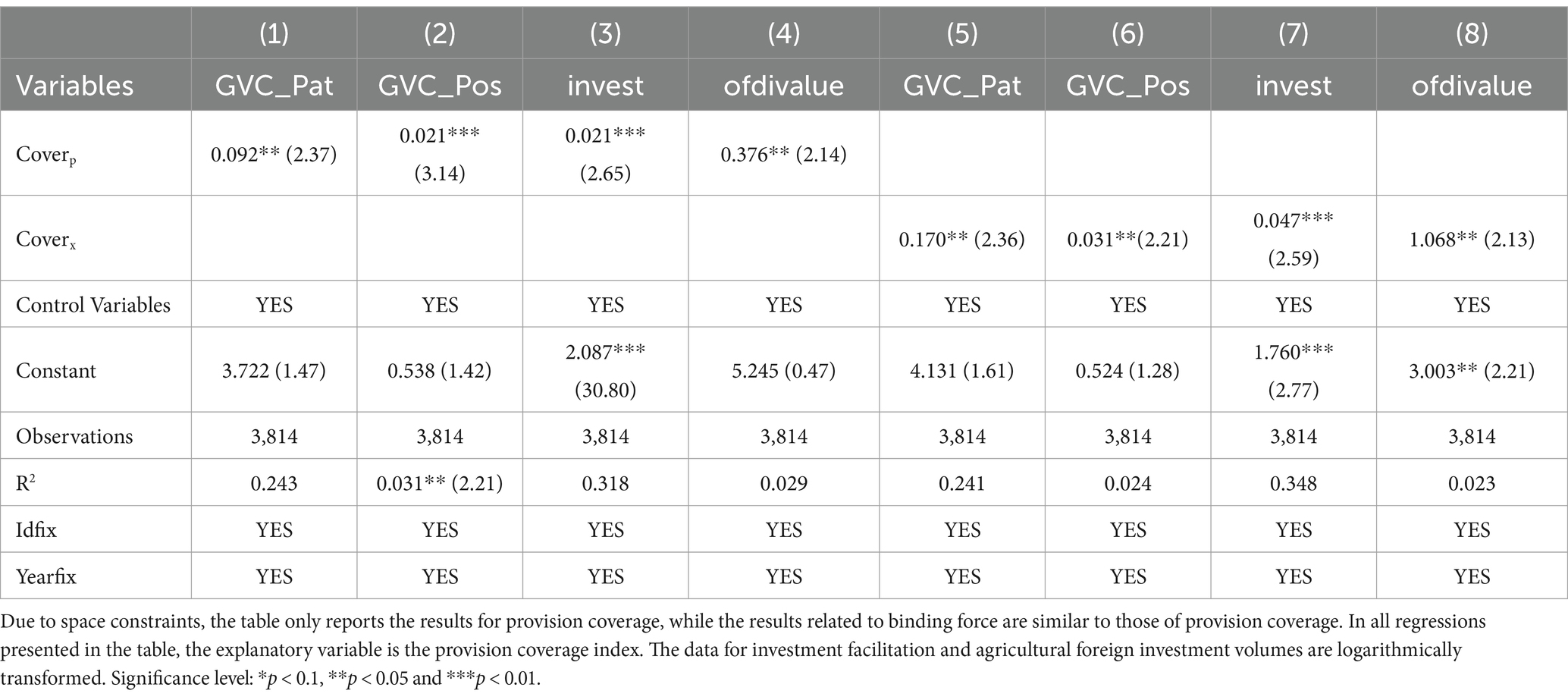

5.5.2 Examination of the investment facilitation mechanism

Next, we analyze the mechanism through which FTA depth influences a country’s AGVC participation degree and division position via investment facilitation. Table 11 presents the regression results. Columns (1) to (4) illustrate how the ‘WTO+’ provision coverage index affects AGVC participation degree, division position, investment facilitation, and agricultural foreign investment, with all coefficients positive and statistically significant. While columns (5) through (8) report the regression results for the ‘WTO-X’ provision coverage index, they also show positive and significant coefficients, all at the 5% significance level or higher. These results indicate that increases in the ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provision coverage indices within FTAs contributes to enhancing investment facilitation and boosting a country’s agricultural foreign investment. Investment facilitation involves the simplification of cross-border investment processes, making investment activities more convenient, stable, and transparent, thereby reducing investment risks and costs, which in turn fosters the growth of agricultural foreign investments (Chen et al., 2020; Gui et al., 2023; Agyeiwaa-Afrane et al., 2024). Specifically, the increase in foreign investments by agricultural multinational enterprises suggests that a country can transfer segments of the value chain characterized by a lack of comparative advantage, overcapacity, or high pollution through foreign investments (Kastratovic, 2019). This transfer minimizes unnecessary resource waste, optimizes resource allocation, and emphasizes the enhancement of research and development in advanced agricultural technologies, ultimately achieving industrial optimization and upgrading, thereby improving its degree of participation and position within the GVC.

Furthermore, by establishing cooperative research and development institutions with developed countries through foreign investments, a country can closely engage with advanced technologies in collaboration with local enterprises. For agriculture, learning from and adapting advanced technologies for local application can significantly increase national agricultural productivity, facilitate structural adjustment and upgrading of the industry, and enhance the quality of agricultural products, thereby gaining competitive advantages in the international arena and improving participation and position within the GVC. In summary, Hypothesis 3 is validated.

6 Discussion

This paper explores how FTA depth affects member countries’ participation and position in the AGVC, as well as the mechanisms through which trade liberalization and investment facilitation play a role in this context. Through theoretical analysis and empirical testing, the paper draws significant conclusions that warrant further discussion.

Firstly, the research findings indicate that an increase in FTA depth significantly enhances member countries’ participation and position within the AGVC. This finding aligns with the conclusions of Orefice and Rocha (2014) and Laget et al. (2020), which state that deep trade agreements help intensify GVC divisions. The enhancement of FTA depth not only reduces tariff and non-tariff barriers, promoting trade liberalization, but also improves the institutional environment and lowers institutional transaction costs by encompassing a broader range of ‘WTO-X’ provisions, such as environmental standards, intellectual property protection, and competition policy (Horn et al., 2010). This creates more favorable conditions for agricultural enterprises to participate in GVCs, thereby enhancing their international competitiveness.

Secondly, the mechanism examination reveals that FTA depth influences a country’s participation and position in the AGVC by promoting trade liberalization and investment facilitation. By reducing trade barriers, FTA depth facilitates the cross-border flow of agricultural products and technology, thereby promoting the internationalization of the agricultural sector (Freund and Ornelas, 2010). Investment facilitation improves the investment environment, attracting more foreign direct investment into the agricultural sector. This influx brings advanced technologies, capital, and management expertise, which enhances agricultural productivity and product quality (Blomström and Kokko, 1997). This dual mechanism further explains how FTA depth contributes to the upgrading of the AGVC.

However, this paper has certain limitations. First, the research is primarily based on macro-level data and does not fully account for the variations among different countries and regions within the AGVC. Future studies should incorporate micro-level data, such as firm-level survey information, to explore the effects of FTA depth on agricultural enterprises of various scales and types. It is also possible to focus on the heterogeneity at the product level and explore how FTA depth affects the participation of different categories of agricultural products in the division of labor within the AGVC. Additionally, this paper primarily focuses on the mechanisms of trade liberalization and investment facilitation, without considering other potential mechanisms, such as human capital, technological innovation, and financial development. Future research should verify the influence of these mechanisms. Furthermore, changes in the global economic environment, such as geopolitical risks, the rise of trade protectionism, and global pandemics, may affect the effective implementation of FTAs and the development of the AGVC. Future studies should consider these external environmental factors and assess their potential impacts.

In summary, deepening FTA content, particularly focusing on the negotiation and implementation of ‘WTO-X’ provisions, is highly significant for improving a country’s participation and position in the AGVC. Policymakers should actively promote the integration of FTAs, advance trade liberalization and investment facilitation, and improve the relevant institutional environment to help the agricultural sector integrate more deeply into the GVC and enhance its international competitiveness.

7 Conclusion

Using panel data from 64 countries between 2003 and 2018, this paper employs a combination of theoretical analysis and empirical testing to explore how FTA depth affects a country’s AGVC participation and position. The findings reveal the following: (1) An increase in FTA depth significantly enhances a country’s AGVC participation and division position. This conclusion remains valid after various robustness checks. (2) Both the ‘WTO+’ and ‘WTO-X’ provision depths positively contribute to improving the participation and position of a country in the AGVC. However, the influence of ‘WTO-X’ provisions is more pronounced than that of ‘WTO+’ provisions. (3) Heterogeneity analysis shows that an increase in FTA depth positively impacts both developed and developing countries, though the influence is more significant for developed countries. This difference is attributed to variations in economic development levels and resource endowments among countries. (4) Mechanism analysis indicates that FTA depth enhances a country’s AGVC participation degree and division position through two main pathways: promoting trade liberalization and facilitating investment.

Drawing from the findings presented above, the following policy recommendations are suggested: (1) Actively promote the signing of deeper FTAs and intensify international cooperation in agriculture. Countries should focus on the deep integration and development of FTAs, covering not only traditional ‘WTO+’ provisions but also emphasizing the negotiation and conclusion of ‘WTO-X’ provisions that encompass broader areas. By enhancing the transparency and clarity of provisions, countries can reduce uncertainties in cross-border production and investment activities, enabling businesses to better predict and mitigate risks. Additionally, an efficient dispute resolution mechanism should be established and improved to ensure swift and fair handling of conflicts between trade partners, thereby ensuring the effective implementation of FTAs and enhancing their role in advancing the AGVC. (2) Accelerate the promotion of trade liberalization and investment facilitation to improve positions within the AGVC. Countries should further reduce trade barriers, simplify customs procedures, improve logistics infrastructure, and eliminate tariff and non-tariff obstacles to foster the development of trade liberalization. Simultaneously, simplifying cross-border investment procedures, enhancing market transparency and stability, and advancing the process of investment facilitation will create a more open and fairer competitive environment for enterprises, increasing their competitiveness in international markets. In the agricultural sector, promoting trade liberalization and investment facilitation will enable countries to integrate more deeply into the AGVC, improving their position and participation. Through strengthened international cooperation and improved resource allocation efficiency, countries and enterprises can more effectively access global markets, capture more value chain profits, and seize growth opportunities, contributing to the overall development and prosperity of the AGVC. (3) Developed and developing countries need to leverage their respective advantages to jointly advance the evolution of the AGVC. During FTA negotiations, it is important to select negotiation topics and terms judiciously. When negotiating with developing countries, greater attention should be paid to the existing terms under the WTO framework, while negotiations with developed countries can focus on deeper ‘WTO-X’ terms. Developed countries can continue to utilize their advantages in funding and resources to strengthen agricultural technology research and development, further consolidating their position in the AGVC. Additionally, through technology transfer and cooperation, they can assist developing countries in enhancing agricultural production capacity, thereby promoting the formation of a mutually beneficial and sustainable AGVC division of labor system. Developing countries can establish cooperative research and development institutions with developed countries to learn from their advanced agricultural technologies, knowledge, and management practices, gradually integrating into the upstream segment of the GVC. Furthermore, developing countries should improve their negotiation skills and techniques, collaborating to create synergistic effects that enhance their bargaining power in FTA negotiations and maximize their interests.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

HZe: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. HZh: Validation, Writing – review & editing. JX: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study received financial support from the Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences Research under the Ministry of Education (grant number 22YJC790006) and the General Fund of the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2022M722691).

Acknowledgments

All the authors are grateful to the reviewers and editors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The paper also employs the lagged value of the core explanatory variable as an instrumental variable to address the issue of endogeneity, and the results are robust.

References

Agyeiwaa-Afrane, A., Agyei-Henaku, K. A. A. O., Badu-Prah, C., Srofenyoh, F. Y., Gidiglo, F. K., and Djokoto, J. G. (2024). The theory of the investment development path and agriculture in Eastern Europe. Heliyon 10:e31870. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31870

Baier, S. L., and Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? J. Int. Econ. 71, 72–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.02.005

Baldwin, J., and Yan, B. L. (2021). Globalization, productivity performance, and the transformation of the production process*. Scand. J. Econ. 123, 1088–1115. doi: 10.1111/sjoe.12454

Blomström, M., and Kokko, A. (1997). Regional integration and foreign direct investment. NBER Working Paper No. 6019.

Chen, J. Y., Liu, Y. S., and Liu, W. (2020). Investment facilitation and China's outward foreign direct investment along the belt and road. China Econ. Rev. 61:101458. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101458

Chen, Y., and Zhang, Y. B. (2023). Services development, technological innovation, and the embedded location of the agricultural global value chain. Sustain. For. 15:2673. doi: 10.3390/su15032673

Cheng, B. W., and Dong, B. M. (2024). Long-term orientation and outward foreign direct investment: evidence from Chinese listed firms. World Econ. 1–23. doi: 10.1111/twec.13647

Cheng, D. Z., Wang, J., and Xiao, Z. G. (2022). Free trade agreements partnership and value chain linkages: evidence from China. World Econ. 45, 2532–2559. doi: 10.1111/twec.13243

Cheng, D.Z., Wang, X.K., Xiao, Z.G., and Yao, W.Q. (2016). How does the selection of FTA partner (s) Matter in the context of GVCs? The experience of China. Working Paper.

Chi, M. J. (2002). Investment facilitation and sustainable development: insufficiencies and improvements of ASEAN investment treaties. J. Int. Econ. Law 25, 611–626. doi: 10.1093/jiel/jgac036

Dunning, J. H. (1977). “Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: a search for an eclectic approach” in The international allocation of economic activity (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 395–418. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-03196-2_38

Dür, A., Baccini, L., and Elsig, M. (2014). The Design of International Trade Agreements: introducing a new dataset. Rev. Int. Organ. 9, 353–375. doi: 10.1007/s11558-013-9179-8

Eum, J. (2023). Non-tariff measures along global value chains: evidence from ASEAN countries. Asian-Pacific Econ. Lit. 37, 27–53. doi: 10.1111/apel.12389

Fally, T. (2012). Production staging: Measurement and facts. Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado-Boulder.

Fan, H. L., Trinh Thi, V. H., Zhang, W., and Li, S. (2022). The influence of trade facilitation on agricultural product exports of China: empirical evidence from ASEAN countries. Econ. Res. Ekonomska Istraz. 36:3845. doi: 10.1080/1331677x.2022.2143845

Feyaerts, H., Van den Broeck, G., and Maertens, M. (2019). Global and local food value chains in Africa: a review. Agric. Econ. 51, 143–157. doi: 10.1111/agec.12546

Freund, C., and Ornelas, E. (2010). Regional Trade Agreements. Ann. Rev. Econ. 2, 139–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.economics.102308.124455

Fusacchia, I., Balie, J., and Salvatici, L. (2022). The AfCFTA impact on agricultural and food trade: a value-added perspective. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 49, 237–284. doi: 10.1093/erae/jbab046

Grossman, G. M., and Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 35, 517–526. doi: 10.1016/0014-2921(91)90153-a

Gui, Y. J., Kang, J. G., and Jeong, Y. S. (2023). Analysis of the effects of investment facilitation levels on China's OFDI focusing on RCEP member states. J. Korea Trade 27, 161–178. doi: 10.35611/jkt.2023.27.3.179

Hanifa, M. H., Chan, S. G., and Abd Sukow, M. E. (2022). Does bilateral trade between China and ASEAN countries improve its Firm's efficiency? J. Asian Finan. Econ. Bus. 9, 313–324. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2022.vol9.no2.0313

Helpman, E., and Krugman, P. (1987). Market structure and foreign trade. London, England: The MIT Press.

Hofmann, C., Osnago, A., and Ruta, M. (2017). horizontal depth: a new database on the content of preferential trade agreements. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7981.

Hong, J., Zhou, C. Y., and Wang, R. C. (2020). Influence of local institutional profile on global value chain participation: an emerging market perspective. Chin. Manag. Stud. 14, 715–735. doi: 10.1108/CMS-09-2019-0319

Horn, H., Mavroidis, P. C., and Sapir, A. (2010). Beyond the WTO? An anatomy of EU and US preferential trade agreements. World Econ. 33, 1565–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01273.x

Hou, Y. L., Wang, Y., and Xue, W. J. (2020). What explains trade costs? Institutional quality and other determinants. Rev. Dev. Econ. 25, 478–499. doi: 10.1111/rode.12722

Hummels, D., Ishiib, J., and Yi, K. (2001). The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade. J. Int. Econ. 54, 75–96. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00093-3

Javorcik, B. S. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. Am. Econ. Rev. 94, 605–627. doi: 10.1257/0002828041464605

Ji, X., Liu, Y. F., Wu, G. W., Su, P., Ye, Z., and Feng, K. S. (2022). Global value chain participation and trade-induced energy inequality. Energy Econ. 112:106175. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106175

Johnson, R. C., and Noguera, G. (2012). Accounting for intermediates: production sharing and trade in value added. J. Int. Econ. 86, 224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.003

Jordan, A. C. (2017). Impact of non-tariff measures on trade in Mauritius. Foreign Trade Rev. 52, 185–199. doi: 10.1177/0015732516681873

Kastratovic, R. (2019). Impact of foreign direct investment on greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture of developing countries. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 63, 620–642. doi: 10.1111/1467-8489.12309

Koopman, R., Powers, W., Wang, Z., and Wei, S.J. (2010). Give credit where credit is due: tracing value added in global production chains. NBER Working Paper No. 16426.

Laget, E., Osnago, A., Rocha, N., and Ruta, M. (2020). Deep trade agreements and global value chains. Rev. Ind. Organ. 57, 379–410. doi: 10.1007/s11151-020-09780-0

Lee, S., and Kim, C. S. (2022). The impact of deep preferential trade agreements on (global value chain) trade: who signs them matters. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 58, 1629–1638. doi: 10.1080/1540496X.2021.1917359

Li, J. E., and Choi, Y. J. (2021). Global value chain formation and human capital: case of Korea and ASEAN. J. Korea Trade 25, 126–142. doi: 10.35611/jkt.2021.25.6.126

Liang, L., and Liang, Y. W. (2021). An empirical study on the National Heterogeneity of high-end manufacturing technology innovation and GVC's division of labor status. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2021/7464384

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71, 1695–1725. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00467

Ming, B., Ye, M., and Wei, S. J. (2015). Measuring smile curves in global value chains*. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 82, 988–1016. doi: 10.1111/obes.12364

Morrissey, O., and Filatotchev, I. (2000). Globalisation and trade: the implications for exports from marginalised economies. J. Dev. Stud. 37, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/713600066

Mudambi, R. (2008). Location, control and innovation in knowledge-intensive industries. J. Econ. Geogr. 8, 699–725. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbn024

Orefice, G., and Rocha, N. (2014). Deep integration and production networks: an empirical analysis. World Econ. 37, 106–136. doi: 10.1111/twec.12076

Osnago, A., Rocha, N., and Ruta, M. (2019). Deep trade agreements and vertical FDI: the devil is in the details. Can. J. Econ. 52, 1558–1599. doi: 10.1111/caje.12413

Ren, X. H., Zhong, Y., Cheng, X., Yan, C., and Gozgor, G. (2023). Does carbon price uncertainty affect stock price crash risk? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 122:106689. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106689

Shin, N., Kraemer, K. L., and Dedrick, J. (2012). Value capture in the global electronics industry: empirical evidence for the "smiling curve" concept. Ind. Innov. 19, 89–107. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2012.650883

Sun, H. Y., Luo, Y. P., Liang, Z. Y., Liu, J., and Bhuiyan, M. A. (2024). Digital economy development and export upgrading: theoretical analysis based on Chinese experience. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 66, 339–354. doi: 10.1002/tie.22383

Sun, L., Zhou, K., and Yu, L. (2020). Does the reduction of regional trade policy uncertainty increase Chinese enterprises' outward foreign direct investment? Evidence from the China-ASEAN free trade area. Pac. Econ. Rev. 25, 127–144. doi: 10.1111/1468-0106.12331

Vincentvicard, (2009). On trade creation and regional trade agreements: does depth matter? Rev. World Econ. 145, 167–187. doi: 10.1007/s10290-009-0010-9

Wang, X. F., Liu, H. Y., and Wang, L. X. (2024). Foreign competition and export diversification: evidence from domestic firms in China. World Econ. United States: The World Economy. 1–24. doi: 10.1111/twec.13654

Wang, W. X., and Thangavelu, S. (2021). Trade and human Capital in Global Value Chain in developed and developing countries*. Asian Econ. Papers 20, 1–15. doi: 10.1162/asep_a_00834

Wang, Z., Wei, S.J., and Zhu, K.F. (2013). Quantifying international production sharing at the bilateral and sector levels. NBER Working Papers No. 19677.

Wickrama, S. P., Kandangama, N. B., Wickramaarachchi, T., and Weerahewa, J. (2024). Assessing the impact of non-tariff measures on Sri Lankan mango exports: insights, challenges, and recommendations. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1293263. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1293263

Wilson, J. S., and Abiola, V. O. (2003). Standards and global trade: A voice for Africa. Washington DC, United States of America: World Bank Publications.

Wu, L. M., Chen, G. F., and Peng, S. J. (2021). Human capital expansion and global value chain upgrading: firm-level evidence from China. Chin. World. Econ. 29, 28–56. doi: 10.1111/cwe.12386

Xin, G., Khan, H., and Ling, X. (2024). The impact of BRICS trade facilitation on China’s import and export trade in agricultural products. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1397350. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1397350

Xu, L., Jing, J., and Wu, C. Y. (2024). Impact of financial development on the position in global value chain: an analysis from the perspective of R & D intensity. J. Asian Econ. 92:101742. doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2024.101742

Keywords: free trade agreements, agricultural global value chain, trade liberalization, investment facilitation, international trade

Citation: Zeng H, Chen S, Zhang H and Xu J (2025) The effects and mechanisms of deep free trade agreements on agricultural global value chains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1523091. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1523091

Edited by:

Wenjin Long, China Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Wei Zhang, China Agricultural University, ChinaXuejun Wang, Nanjing Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2025 Zeng, Chen, Zhang and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huasheng Zeng, aHVhc2hlbmd6QHl6dS5lZHUuY24=; Jinhai Xu, eHVqaEB5enUuZWR1LmNu

Huasheng Zeng

Huasheng Zeng Shuyu Chen

Shuyu Chen Haoruo Zhang2

Haoruo Zhang2