- College of Public Administration and Law, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

The policy of rural collective construction land marketization (RCCLM) signifies that such land can currently be traded commercially. This not only breaks the government’s previous monopoly over the primary land market but also creates opportunities for revitalizing rural industries. This study uses county-level panel data from China between 2010 and 2022, treating the policy as a quasi-natural experiment. A multi-period difference-in-differences model is employed to examine its effects on rural industrial integration and the underlying mechanisms. The results indicate that, compared to non-pilot areas, the level of rural industrial integration in pilot areas has increased significantly by 1.47%. This finding remains robust after addressing potential model estimation biases caused by factors such as sample selection bias and reverse causality. Mechanism analysis indicates that RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration development by fostering county-level technological innovation and entrepreneurial activities. Further analysis shows that the policy exhibits significant effects in the eastern, western, and northeastern regions, as well as in counties with larger populations, while showing no significant effects in the central region and counties with smaller populations. Additionally, the RCCLM generates positive spatial spillovers on rural industrial integration of neighboring areas through resource sharing. This study provides valuable insights for research on RCCLM policy and rural industrial integration.

1 Introduction

Since the release of the “No. 1 Document” of Central Government in 2015, promoting the integration of rural industries has become a key policy focus in China’s efforts to address the ‘three rural issues’ (agriculture, rural areas, and farmers; Li and Ran, 2019). Rural industrial integration emphasizes reliance on agricultural development, with farmers and production organizations as the main actors, linked by a close interest mechanism. It breaks down rural industrial boundaries through agricultural value chain extension, multifunctional expansion of agriculture, and integration with services, achieving cross-interaction, organic integration, and coordinated development of rural primary, secondary, and tertiary industries (Zhang and Wen, 2022). It is crucial for deepening agricultural supply-side structural reform and realizing comprehensive rural revitalization (Chen, 2020). Then, how to effectively promote rural industrial integration development? Generally speaking, land elements are the material basis of industrial integration (Jiang, 2021). However, given that rural land must first be converted to urban state-owned construction land before entering the market, dual monopoly of local governments over land acquisition and primary markets has impeded direct rural land transactions. This not only diminishes rural land use efficiency but also creates urban–rural value disparities through the practice of low-price acquisition and high-price disposal (Chen and Long, 2019), which restricts rural industrial integration. Based on this, to establish a unified urban–rural construction land market and unleash the vitality of rural land resources, in March 2015, the Ministry of Land and Resources selected 15 counties nationwide for RCCLM reform. This initiative permits the direct trading of rural collective construction land—eliminating the requirement for conversion into state-owned construction land—through mechanisms, such as direct transfer, leasing, or equity participation, thus ensuring equal market entry, rights, and pricing comparable to state-owned land. In 2016, it extended to 33 pilot counties. As an important practice of China’s rural land system reform, RCCLM plays a vital role in improving rural land use efficiency, attracting industrial and commercial investment (Qu and Ren, 2018), and promoting rural industrial integration development. Despite this, existing research has not explored the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration. Consequently, this study seeks to determine whether RCCLM enhances the level of rural industrial integration and to identify the key mechanisms that underpin this relationship.

The potential innovations of this paper are as follows: (1) While existing research has focused on the policy effects of RCCLM and the factors driving rural industrial integration, it has overlooked direct impact of RCCLM on this integration. Understanding this relationship is crucial for effectively utilizing rural land resources and the sustainable development of rural industries. Therefore, this study utilizes panel data from 255 counties in pilot areas from 2010 to 2022 to examine influence of RCCLM on rural industrial integration and its variation across locations and population sizes. (2) Furthermore, previous studies lack a systematic analysis and empirical testing of the mechanisms through which RCCLM affects rural industrial integration. To fill this gap, this paper adopts a mediation effect model to empirically assess role of RCCLM in promoting rural industrial integration through county-level technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity. (3) Prior research has not examined the spatial effects of RCCLM on rural industrial integration. Thus, this study utilizes a spatial econometric model to provide empirical evidence regarding the spatial spillover effects of RCCLM on rural industrial integration, thereby addressing the existing gaps in the literature on the spatial effects of RCCLM. This research not only supports the comprehensive implementation of RCCLM but also offers valuable insights for enhancing rural industrial integration.

2 Literature review

Currently, academics have engaged in extensive discussions on rural industrial integration development. On the one hand, scholars have explored the connotations, practical challenges, and pathways for rural industrial integration from a theoretical perspective (Shen et al., 2023; Li B. et al., 2023). On the other hand, after measuring the level of rural industrial integration, research empirically examines various influencing factors, such as the digital economy (Meng et al., 2023; Qiu and Teng, 2024; Yuan and Sun, 2024), digital inclusive finance (Huang et al., 2023; Zhang and Zhou, 2021), transport infrastructure (Zhang and Dong, 2022), digital village construction (Chen et al., 2024), financial services (Zhang and Wen, 2019), and modern industrial parks (Sun et al., 2024). Unlike these factors, land is a crucial element and spatial carrier for economic development in urban and rural areas (Long and Tu, 2018) and has been a focal point of research regarding its impact on rural industrial integration. For example, some scholars argue that the transfer of rural land fosters interest linkages between farmers and rural industries, helping overcome land fragmentation and promote the integrated development of rural industries (Yu and Ge, 2023). However, some studies suggest that incomplete intermediary organizations and insufficient construction land indicators limit rural land transfer, resulting in its significant positive impact being confined to the integration of agricultural function expansion (Cheng and Kong, 2020). Additionally, large-scale land management, an inevitable trend of land transfer, promotes rural industrial integration by increasing farmers’ income levels, with income levels and the scale of rural labor transfer positively moderating this effect (Zeng et al., 2022). Other scholars contend that rural land certification promotes rural industrial integration by providing stable property rights and improving farmers’ access to credit (Yan and Cao, 2024). Comprehensive land remediation is also a crucial pathway for activating rural industrial elements, significantly impacting the transformation of agricultural production methods, organization, management practices, and scope of operations, thereby promoting rural industrial development (He et al., 2022). Moreover, based on the practice of land ticket system of Chongqing, scholars suggest that transferring rural construction land significantly promotes regional industrial structure optimization (Mi and Dai, 2020).

As an important rural land resource, RCCLM has been extensively studied regarding its effects. Existing literature positions the RCCLM as a typical Chinese-style land system reform. Foreign scholars have mainly focused on aspects such as land property rights (Moffette et al., 2024), land markets (Kvartiuk et al., 2024), and land development rights (Linkous, 2016), laying the groundwork for this study. Domestic scholars, on the one hand, focus on the studies related to the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial development. For instance, some emphasize its positive effects, arguing that it accelerates rural development by reshaping land use structures, transforming farmers’ livelihoods, and improving rural governance (Shen et al., 2024). It has also increased farmers’ property and wage incomes, narrowing the urban–rural income gap (Li and Cai, 2023; Yang et al., 2017), and boosted the growth of market entities (Lu and Wang, 2024). Conversely, some scholars contend that RCCLM may have negative consequences. Free market competition inevitably results in the majority of agricultural operators, who have lower profit margins and limited financial resources, being unable to acquire existing construction land. This situation constrains the availability of construction land for agricultural development and creates barriers to rural industrial integration (Qu and Ren, 2018). Additionally, research indicates that changes in land prices, labor, capital, and technology due to RCCLM can negatively affect agricultural labor productivity (Li and Song, 2018). On the other hand, some literature focuses on the impact of RCCLM on urban economic development. For instance, scholars using panel data from 333 county-level cities found that RCCLM has fostered collaborative and competitive relationships between rural and urban construction land, thereby improving urban land use efficiency (Wang and Chen, 2023). In addition, existing studies generally suggest that the competition between urban and rural construction land leads to a decline in urban construction land transfer areas and fees (Yan et al., 2023). However, others argue that RCCLM has no significant negative impact on land transfer revenue (Huang et al., 2024). Finally, in the process of urban–rural integration, RCCLM makes a positive contribution by enhancing resource mobility between urban and rural areas and improving the delivery of public services (Wang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

In summary, existing research has extensively covered rural industrial integration development and the policy effects of RCCLM, providing a solid foundation for further study. However, there are areas for improvement. First, while literature examines the impact of rural land elements on industrial integration and evaluates the effects of RCCLM from various perspectives, no study has yet combined these two factors within a single analytical framework to explore their relationship in depth. Second, current research has not addressed the heterogeneous characteristics, intrinsic mechanisms, and spatial spillover effects of the RCCLM on rural industrial integration. Consequently, this paper aims to investigate whether the RCCLM can promote rural industrial integration and identify its mechanisms of action. It also seeks to determine whether this impact exhibits heterogeneous characteristics based on spatial location and population size, as well as whether it generates spatial spillover effects in neighboring areas. By addressing these questions, the study aims to provide feasible policy recommendations for the orderly promotion of RCCLM and the establishment of a modern agricultural industry system.

3 Policy background and theoretical framework

The transfer of usage rights for rural collective construction land has evolved significantly over time. As a distinctive institutional innovation in China, the RCCLM has facilitated the efficient allocation of rural construction land, thereby improving land utilization and fostering opportunities for interaction and integration among rural industries. Based on a brief overview of the policy background, this section seeks to analyze the impact of the RCCLM on rural industrial integration, elucidate its underlying logic, and propose research hypotheses.

3.1 Policy background

The reform of the rural land system has profoundly influenced socio-economic development in China. Throughout the periods of socialist revolution, construction, reform, opening-up, and modernization, it has served as a powerful catalyst for advancing productive forces and adjusting production relations. However, as socialism with Chinese characteristics enters a new era, the differentiated urban–rural land system has limited rural development and widened the urban–rural gap. The limitation arises from restrictions on the direct market trading of rural collective construction land, which hampers the ability to meet current needs of high-quality economic development. Therefore, allowing RCCLM is an effective strategy to create a unified urban–rural construction land market and reduce imbalances in urban–rural development, making it a key focus of China’s rural land system reform (Wang et al., 2023). Based on this, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee in 2013 adopted the Decision on Several Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform. This decision proposed that, under the premise of meeting planning and use controls, rural construction land be allowed to transfer, lease, or turned into shareholdings, placing it on the same market with equal rights and pricing as state-owned construction land. In 2015, the 13th session of the 12th National People’s Congress Standing Committee approved the Decision on Authorizing the State Council to Temporarily Adjust the Implementation of Relevant Legal Provisions in the Administrative Regions of Beijing Daxing District and 32 Other Pilot Counties (Cities and Districts). It selected 15 regions to undertake pilot reforms for RCCLM. In September 2016, this reform was extended to all 33 pilot areas. The 2019 amendment to the Land Management Law officially granted market participation rights to rural collective construction land. However, nationwide implementation has been limited. Both the 27th meeting of the Central Comprehensive Deepening Reform Commission in September 2022 and the subsequent Opinions on Deepening the Pilot Program for the Market Entry of Rural Collective Operational Construction Land issued by the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council emphasized a cautious approach to market reform. Consequently, the Ministry of Natural Resources initiated a new round of pilot programs in selected counties nationwide to further explore this reform. The delay in implementation indicates persistent practical challenges and unmet expectations. To fully unlock the potential of institutional reforms, it is imperative to broaden our understanding of the effects of RCCLM. While focusing on how the policy can effectively alleviate the shortage of urban construction land, it is equally important to investigate whether it has an impact on rural industrial integration development.

3.2 Theoretical framework

Rural industrial integration is a complex process that encompasses multiple sectors and dimensions, including agricultural chain extension, multifunctional agriculture, and agri-service integration. RCCLM has revitalized rural land factors, significantly impacting various aspects of this integration. This section examines the relationship between RCCLM and rural industrial integration through direct impacts and transmission mechanisms, proposing relevant research hypotheses.

3.2.1 The direct impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development

The extension of agricultural industry chains, the diversification of agricultural functions, and the integration of agriculture with service industries are important areas for the development of rural industrial integration. Therefore, this paper takes these three areas as entry points, respectively, to explore the direct impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development. First, regarding agricultural industry chain extension, village collectives can directly attract external industrial and commercial enterprises specializing in weak links of the agricultural chain through equity participation or leasing of rural collectively operated construction land. This will facilitate the clustering of agricultural-related enterprises in rural areas, encompassing production, processing, warehousing, logistics, and sales, thereby reducing costs in the intermediate stages from production to sales and expanding profit margins. Thus, RCCLM promotes both the extension of the agricultural industry chain and the enhancement of its value chain. Second, regarding agricultural multifunctionality, RCCLM not only enhances economic function of agriculture but also promotes its social and ecological roles. Specifically, RCCLM enhances social functions of agriculture by attracting investment and promoting rural industrial development, thereby increasing local employment opportunities (Zhao et al., 2023). It also addresses ecological concerns by reducing farmers’ tendency to overuse agrochemicals due to risk aversion (Khan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). The land appreciation income from RCCLM helps mitigate economic risks from crop yield declines, decreasing farmers’ motivation to over-apply fertilizers and pesticides, thus reducing agricultural pollution and promoting ecological functions. Finally, in the integrated development of agriculture and the service industry, RCCLM effectively increases farmers’ income levels by capitalizing on the economic value of land (Yang et al., 2017), thereby providing financial support for purchasing agricultural machinery and actively participating in the agricultural machinery service market. Moreover, as policy deepens, rural industries diversify, offering rural laborers employment beyond traditional farming. This not only expands income sources but also shifts some labor to non-agricultural sectors, thereby boosting demand for agricultural services like machinery and fostering integration of agriculture with service industries (Pang and Wu, 2023). In summary, this paper proposes:

Hypothesis 1: RCCLM can promote rural industrial integration development.

3.2.2 The indirect impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development

Considering that the promotion of RCCLM means the improvement of the marketization level of land elements and the optimization of land resource allocation, which is conducive to the improvement of regional technological innovation level (Gong et al., 2020) and the development of entrepreneurial activities (An and Zhao, 2021), providing impetus for the rural industrial integration development. Based on this, this paper discusses the mechanism of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development from the perspective of technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity.

RCCLM fosters rural industrial integration by enhancing technological innovation. First, RCCLM is conducive to the improvement of regional technological innovation level. It does this by boosting investment in innovation. Given that collective construction land, compared to urban land, offers parcels at lower costs and faster acquisition. This advantage allows enterprises to reduce land acquisition expenses for industrial growth, thereby lowering initial operational costs (Li and Cai, 2023) and freeing up capital for technological advancements. Additionally, RCCLM diminishes the incentive for companies to forge political connections to acquire urban land, consequently lessening the drain on R&D funds from non-productive expenses. This helps boost corporate investment in innovation and fosters technological advancement. Moreover, RCCLM boosts technological innovation by enhancing the willingness to innovate. By improving the efficiency of rural land use and alleviating construction land resource constraints, RCCLM facilitates easier market entry for businesses, thereby intensifying competition. As a result, enterprises and individuals are more inclined to engage in technological innovation to secure a competitive edge and avoid being outcompeted.

Second, technological innovation can promote rural industrial integration. On the one hand, the use of innovative technology has a demonstration effect to a certain extent (Radmehr et al., 2023). For example, by leveraging innovative technologies to enhance the level of agricultural mechanization and fostering new types of agricultural business entities, enterprises can achieve large-scale agricultural operations and improve economic benefits. At the same time, this also helps reduce the use of fertilizers, pesticides, and other inputs, thereby enhancing ecological benefits. Furthermore, it sets an example for upstream and downstream enterprises as well as different industries, encouraging related enterprises to imitate, thus generating a technology spillover effect (Qiu and Zhao, 2015). This fosters technological interconnections among industries, blurring industrial boundaries. It supports the application of industrial and service sector management techniques in agriculture, enhancing multifunctionality of agriculture and propelling rural industrial integration. On the other hand, the technological innovation represented by digital technology facilitates the restructuring and cross-border integration of the industrial chain (Guo, 2023; Tzounis et al., 2017), which supports the growth of new business models such as smart agriculture and rural e-commerce. This advancement also significantly improves the standardization, digitalization, and the level of benefit linkage from the production to the sale of agricultural products and further promotes rural industrial integration. In summary, this paper proposes:

Hypothesis 2: RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration through technological innovation.

RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration by boosting entrepreneurial activity. First, RCCLM can increase entrepreneurial activity. RCCLM can increase entrepreneurial activity by alleviating financial constraints. On the one hand, it alleviates financial constraints by addressing the shortage of urban construction land and offering lower-cost collective construction land (Li and Cai, 2023). This reduces the initial economic risk for enterprises, thereby enhancing entrepreneurial enthusiasm. On the other hand, by promoting the upgrading of rural industries, RCCLM creates numerous non-agricultural jobs and increases farmers’ wage income. It also facilitates the redistribution of land appreciation gains, directing more land income to rural areas, which boosts farmers’ property income (Li and Cai, 2023). This supports the accumulation of entrepreneurial capital among farmers and encourages entrepreneurial activities. In addition, RCCLM boosts entrepreneurial activity by enhancing entrepreneurial abilities. By meeting enterprise land demands and promoting industrial agglomeration in rural areas, RCCLM facilitates non-agricultural employment. This dual embedding in social and industrial networks helps individuals acquire essential knowledge and operational resources, significantly improving their ability to perceive entrepreneurial opportunities and manage operations effectively (Zhuang et al., 2014).

Second, increased entrepreneurial activity can drive rural industrial integration. By fostering entrepreneurship across different stages of the agricultural industry chain, stronger interactions and connections are established between the production, processing, and sales of agricultural products. This integration of production and marketing contributes to the extension of the agricultural industry chain (Meng et al., 2023). Moreover, entrepreneurs, relying on the local agricultural development characteristics, embed the development models of different industries such as tourism and information technology into the agricultural production process. This leads to the development of new business forms such as smart agriculture and leisure agriculture. It also supports the growth of new agricultural entities, such as farmer cooperatives, specialized large households, and family farms, thereby promoting rural industrial integration. On the other hand, entrepreneurs’ advanced management experience and knowledge introduce green development concepts and new business models such as wellness agriculture, ecological agriculture, and facility agriculture. This fosters the development of a green agricultural industry chain and enhances the ecological functions of agriculture. Furthermore, entrepreneurs’ strong brand awareness, leveraging the cultural significance of local agriculture, creates distinctive brand images, increasing the value-added of agricultural products. This taps into the cultural aspects of agriculture, upgrades the agricultural value chain, and thereby promotes the development of rural industrial integration. In summary, this paper proposes:

Hypothesis 3: RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration development through increasing entrepreneurial activity.

4 Methods and data

Based on the proposed research hypotheses, to empirically test the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development and its underlying mechanisms, the following outlines the model construction, variable selection, and data sources.

4.1 Model building

First, the study treats the RCCLM pilot policy as a quasi-natural experiment, employing a difference-in-differences model to evaluate its impact on rural industrial integration. Pilot counties serve as the treatment group, while non-pilot areas form the control group. Given the policy’s two-phase implementation in 2015 and 2016, a multi-period difference-in-differences model is utilized. The specific model is constructed as follows:

In Equation 1: is the explained variable, indicating the level of rural industrial integration development of i county in the t year; is the core explanatory variable, indicating i county in the t year whether belongs to RCCLM pilot area; is the control variable; , , and are county fixed effect, time fixed effect, and random error items, respectively.

Second, in order to investigate whether RCCLM enhances rural industrial integration by impacting technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity, this study employs a mediation effect model. The specific model is constructed as follows:

In the above equations, denotes the mediating variables, including the level of technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity, and the meanings of other variables are consistent with the benchmark model.

4.2 Variable descriptions

Based on the research content of this paper and the above measurement model, the selected variables and the specific measurement methods are described as follows.

4.2.1 Explanatory variables

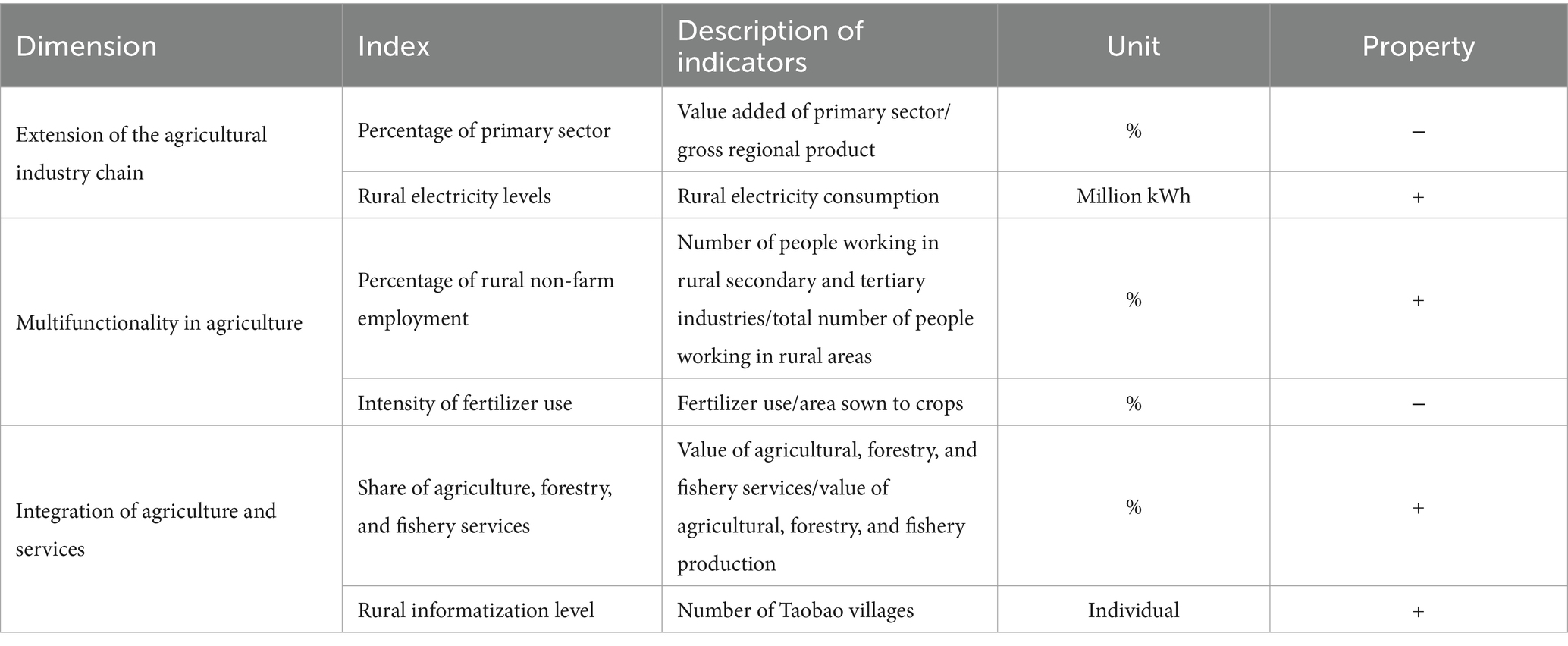

Rural industrial integration (INTE). Following Zhang and Wen (2022) and Jiao (2023), an index system is constructed based on three dimensions: agricultural industry chain extension, multifunctional agriculture, and agriculture–service integration. The comprehensive level of rural industry integration is calculated using the entropy method. Specific indicators are presented in Table 1.

4.2.2 Core explanatory variables

Dummy variables for the policy of RCCLM. Assigned 1 for counties in the pilot program for a given year, 0 otherwise.

4.2.3 Control variables

To control for other factors influencing rural industrial integration, the following control variables are included based on existing research: the level of human capital (lnEDU), measured by the number of students enrolled in general secondary schools in logarithmic terms. The level of fiscal expenditure (lnFISC), measured by the logarithm of total general public budget expenditure. The level of social consumption (lnCON), measured by the logarithm of total retail sales of consumer goods. Farmers’ income level (lnINC), measured by the logarithm of per capita disposable income of rural residents. Industrial structure upgrading (INDUS), measured by output share of secondary and tertiary industries in GDP.

4.2.4 Mediating variables

Technological innovation (INNOV) is measured by the total number of patent applications (invention, utility model, and design) per 100 county residents, accounting for the time lag between application and authorization (Li Z. et al., 2023). Furthermore, the number of registered start-ups reflects the process of enterprise creation. Given the high proportion of rural areas within counties and the strong radiating effect of county-level entrepreneurial activities on rural regions, this study follows Lin et al. (2023) and Ding et al. (2024) in measuring entrepreneurial vitality. The logarithm of newly registered enterprises in the county is used, denoted as lnENTREP.

4.2.5 Data sources

This study focuses on 255 counties in prefecture-level cities with pilot areas from 2010 to 2022. After excluding samples with significant missing data and using linear interpolation for minor gaps, a balanced panel dataset was constructed. The sample includes 32 pilot areas (excluding Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, due to severe data limitations) as the experimental group and 223 non-pilot areas as the control group, following Huang et al. (2023). Pilot area information and timing were sourced from central government documents. Patent application data came from the State Intellectual Property Office. County start-up registration data were obtained from Tianeye Search and Qixinbao databases. Other data were collected from the EPS database, China County Statistical Yearbook, prefecture-level city statistical yearbooks, and county-level economic and social development bulletins. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for all variables.

5 Empirical results and analysis

Using the constructed measurement model, this section empirically examines the effects of RCCLM on rural industrial integration and its various dimensions, conducting a series of robustness tests to verify the stability of the baseline regression. Additionally, it investigates whether technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity serve as mediating variables in the relationship between RCCLM and rural industrial integration.

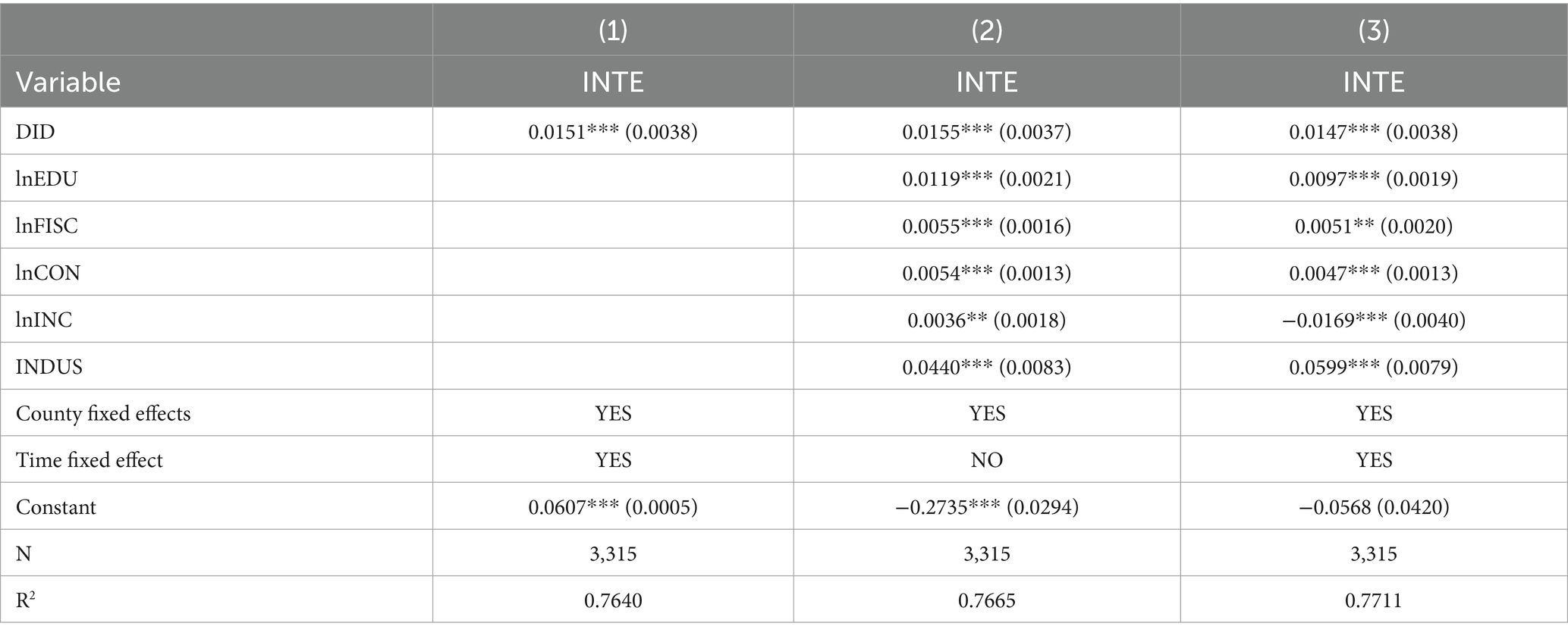

5.1 Benchmark regression

Table 3 presents the benchmark regression results of impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration. Columns (1) through (3) progressively incorporate control variables and account for county and time fixed effects. The core explanatory variable, RCCLM, shows significantly positive coefficients at the 1% level, confirming Hypothesis 1: RCCLM promotes rural industry integration. These results suggest that RCCLM has enhanced rural land value and attracted industrial and commercial capital to rural areas. This development facilitates the extension of agricultural industry chains, leverages multifunctional potential of agriculture, and provides a crucial impetus for strengthening connections between agriculture and secondary/tertiary industries, ultimately fostering their deep integration.

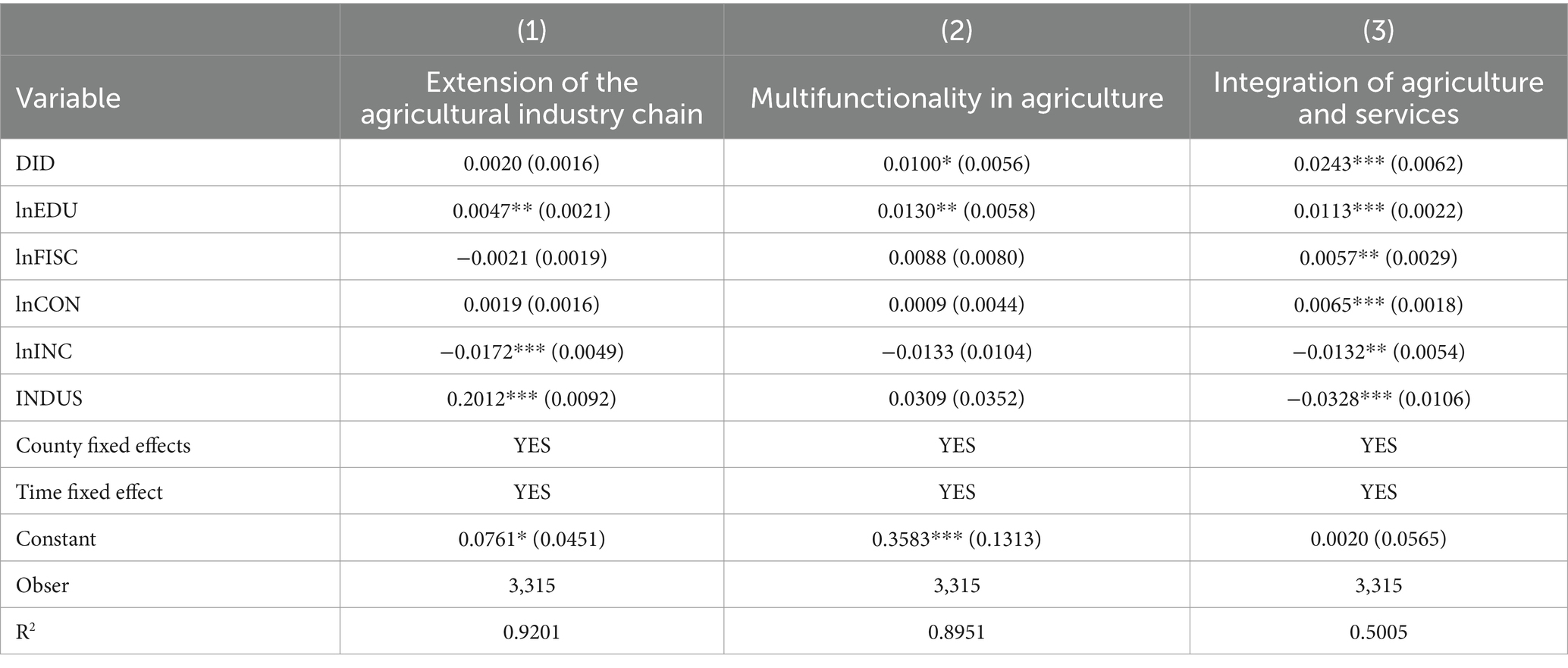

5.2 Dimensional regression

To further investigate impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration, this study performs separate regressions on three dimensions: agricultural industry chain extension, multifunctional agriculture, and agriculture–service integration. Table 4 shows that RCCLM significantly and positively affects multifunctional agriculture and agriculture–service integration, but not agricultural industry chain extension. This likely stems from the fact that while rural construction land strengthens linkages in agricultural production, processing, and marketing, persistent challenges in rural areas, such as weak industrial foundations and underdeveloped financial services, hinder the influx and clustering of external industrial and commercial enterprises. Consequently, at this stage, RCCLM has not significantly influenced the extension of the agricultural industry chain.

5.3 Parallel trend test

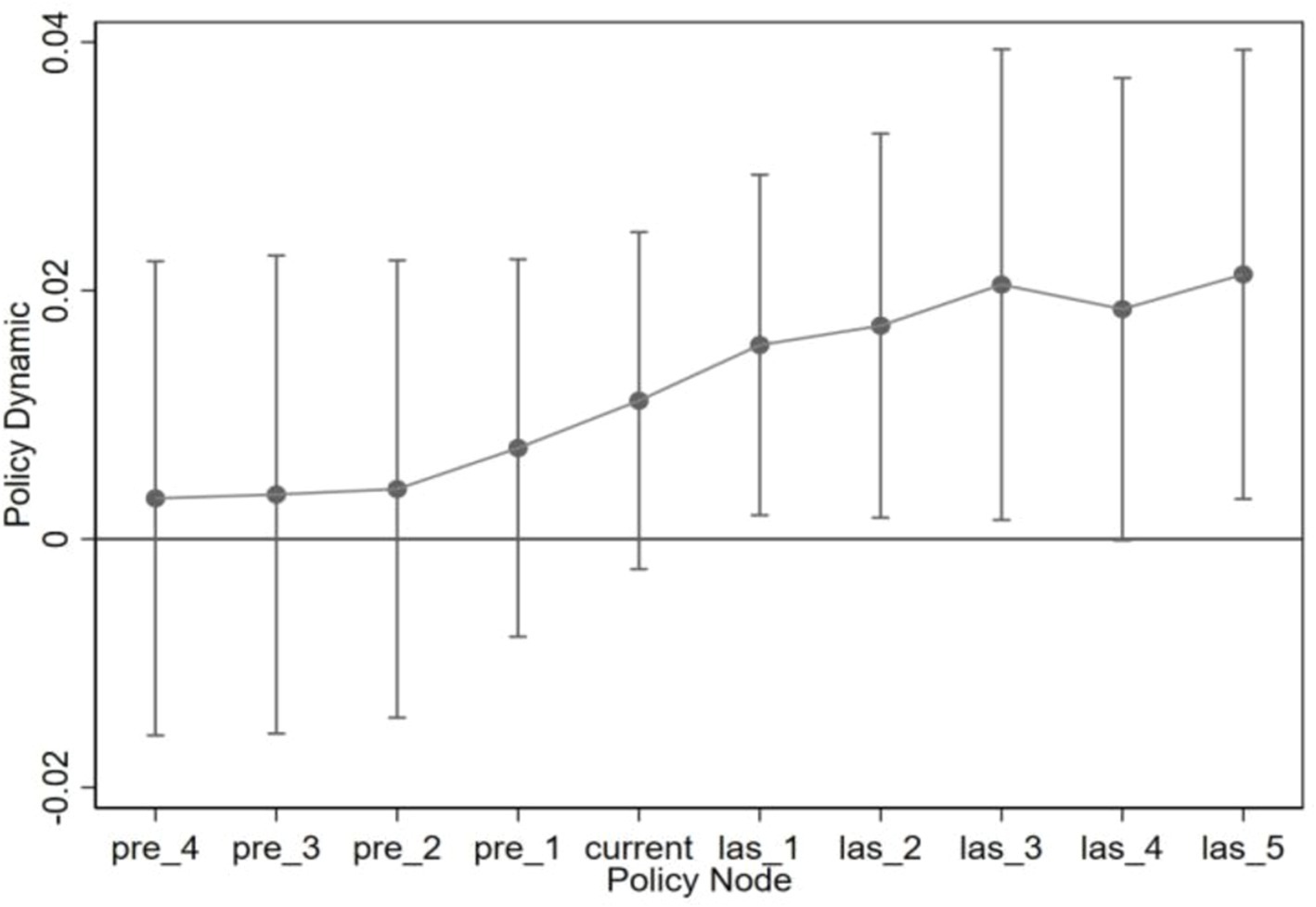

For the estimation results of the multiple-period difference-in-differences model to be valid, the treatment and control groups must satisfy the parallel trend assumption, meaning there should be no significant difference in the level of rural industry integration between the two groups before implementing RCCLM. To test this, the following model is established for the parallel trend test:

In Equation 5, is the coefficient to be estimated, representing the gap between the level of rural industrial integration development in the treatment and control groups before and after the implementation of the policy, s is the number of periods compared to the time of implementation of the policy of RCCLM, and is a constant term, and the meanings of other variables are consistent with Equation 1.

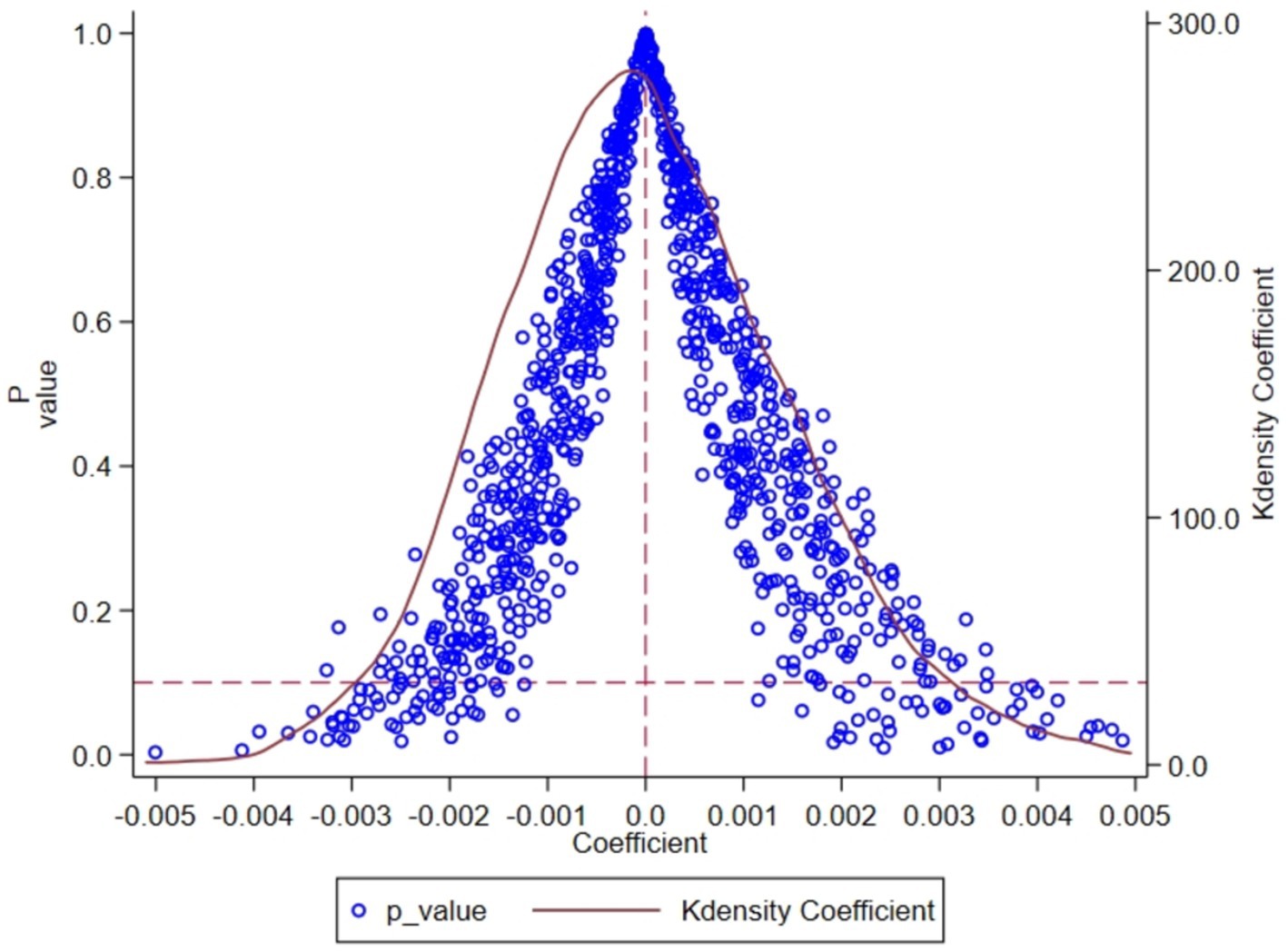

The test results are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that for s < 0, all are not significant. The results show no significant difference in the level of rural industrial integration development between pilot and non-pilot counties before the implementation of RCCLM, indicating that the parallel trend hypothesis is satisfied.

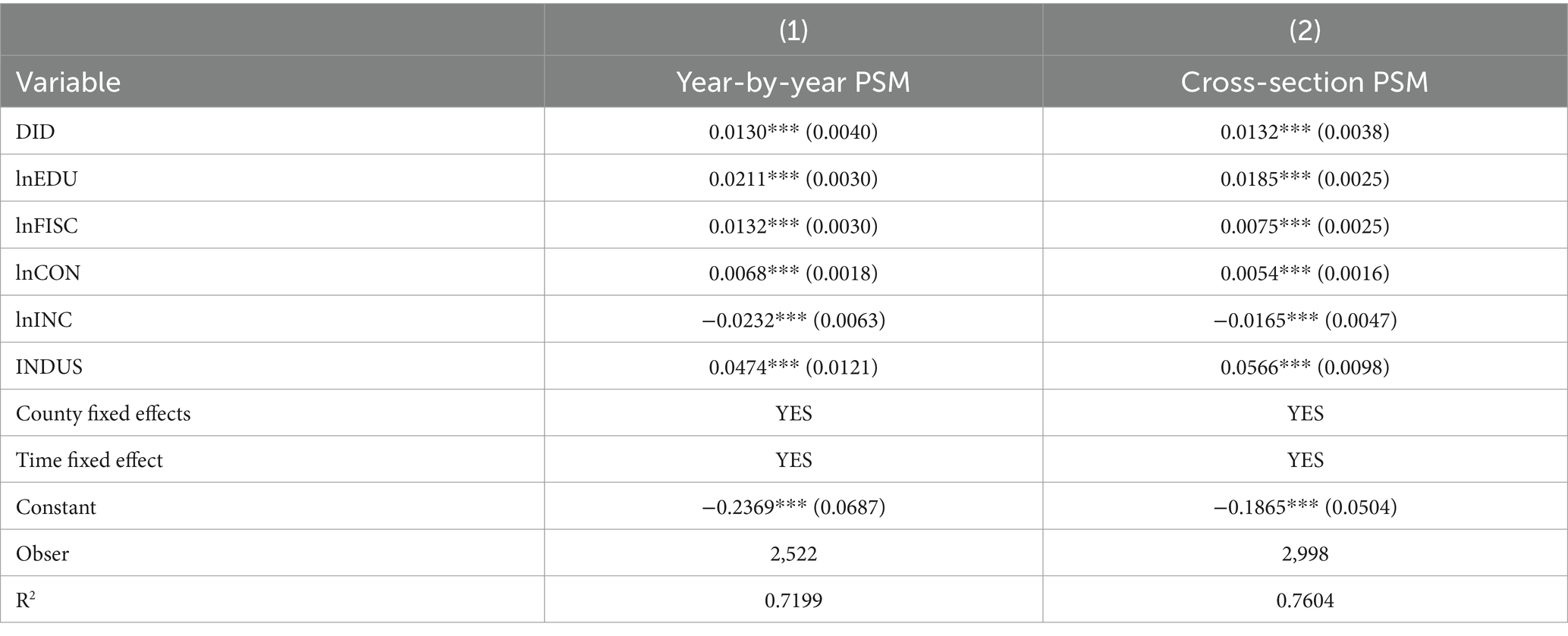

5.4 Placebo test

To further eliminate bias from unobservable factors, a placebo test was conducted based on existing literature. An equal number of counties as the pilot group were randomly selected to form a new treatment group, and the double-difference estimation was re-run to obtain erroneous coefficient estimates of the interaction terms. This process was repeated 1,000 times, and the distribution of the 1,000 estimated coefficients and their corresponding p-values were plotted. Figure 2 shows the results of the placebo test, where the distribution of estimated coefficients from random sampling centers around 0, approximating a normal distribution. The estimated coefficient in the benchmark regression is 0.0147, significantly different from the placebo test results, demonstrating the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

5.5 Robustness tests

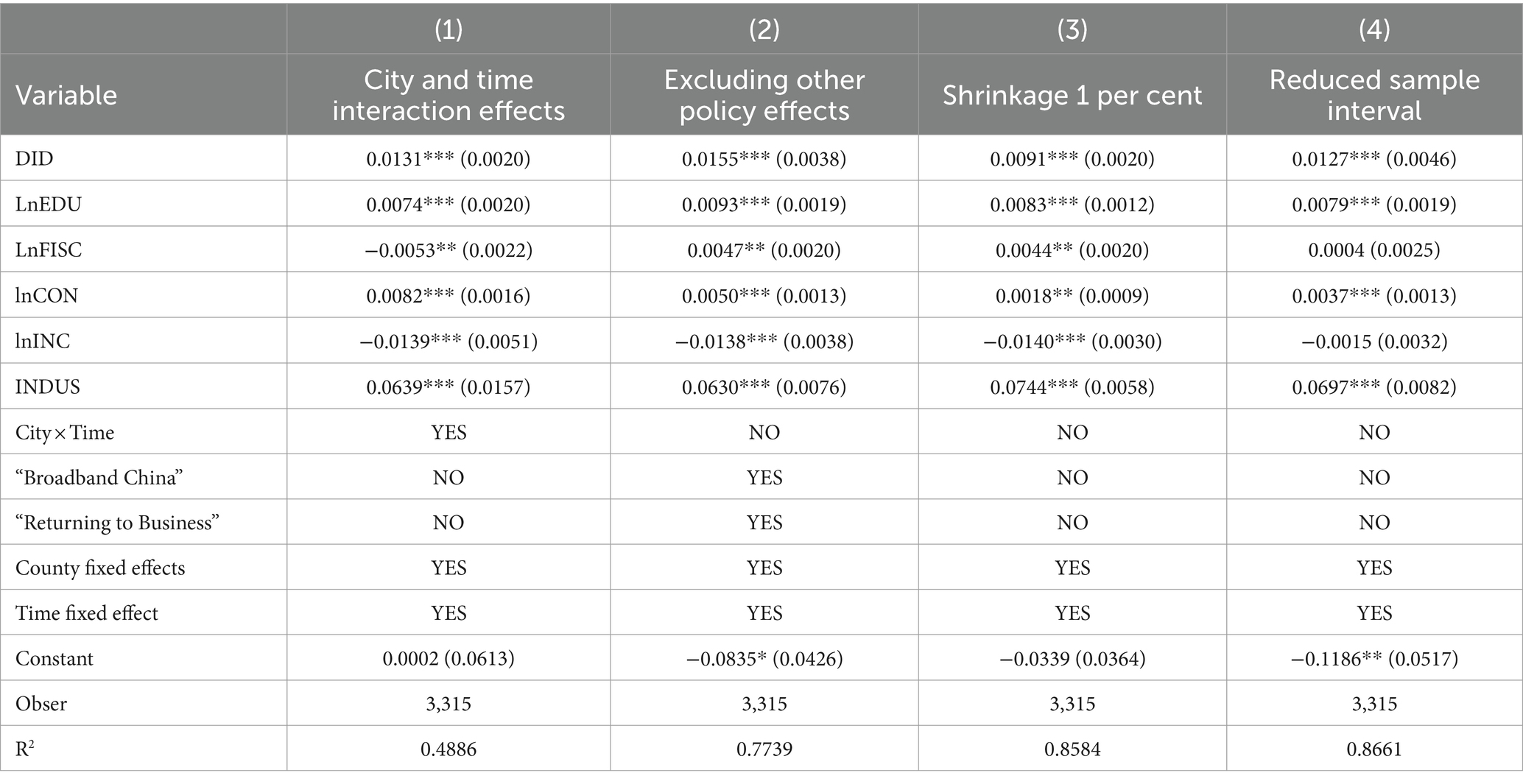

PSM-DID. The selection of pilot areas for RCCLM is not completely random. To better utilize the pilot policy, the government may prefer areas with a larger stock of collectively operated construction land or higher economic development, leading to sample selectivity bias. To address this, we use cross-sectional matching and period-by-period matching methods to match propensity scores and test the robustness of the regression results. The specific steps are as follows: (1) set the control variables in this paper as covariates. (2) Perform kernel matching based on cross-sectional and year-by-year matching and exclude non-co-supporting samples from the total sample to obtain two datasets. (3) Rerun the regression using the multi-period DID model. The results, shown in Table 5, indicate that the regression coefficients of RCCLM on the integrated development of rural industries are significantly positive at the 1% level under both matching methods. This further verifies the robustness of the benchmark regression results.

5.6 Other robustness tests

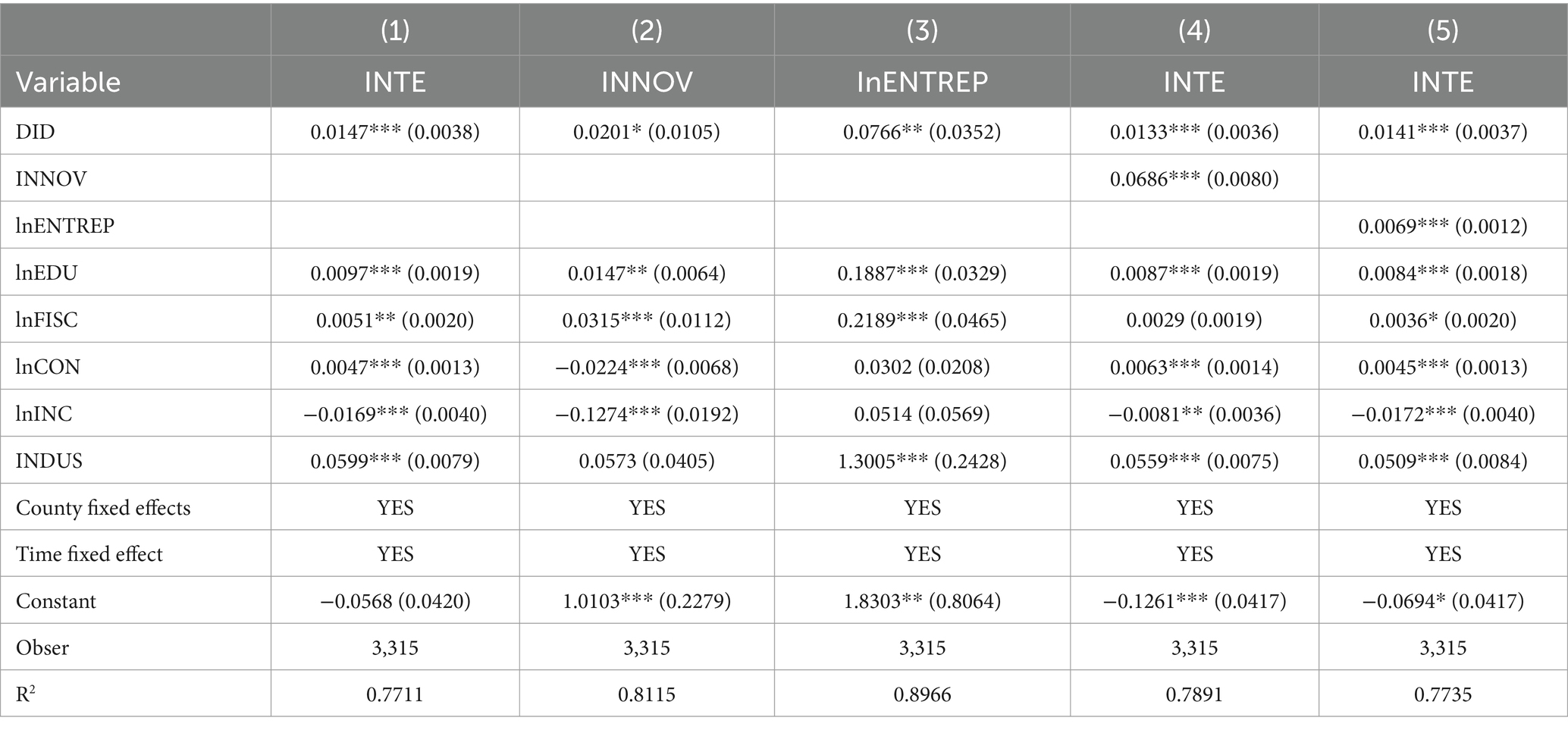

First, accounting for the dynamic factors at the prefecture level, the study incorporates an interaction term between prefecture-level city and year into the baseline model, following Yuan and Xia (2022). The results in column (1) of Table 6 demonstrate that the coefficient of RCCLM remains significantly positive at the 1% level, affirming the robustness of the initial findings against prefecture-level environmental changes.

Second, excluding the impact of other competition policies. From 2010 to 2022, various national policies like the “Broadband China” initiative and rural entrepreneurship programs have been launched, impacting rural industrial integration. The “Broadband China” policy has facilitated digital technology in rural regions, removing technical obstacles for e-commerce, thereby expanding agricultural product sales online, and fostering growth in logistics, packaging, and warehousing. This extends the agricultural industry chain, enhances its value, and thus influences the overall integrated development of rural industries. Furthermore, the policy encouraging rural workers to return home for entrepreneurship offers technology, capital, and tax benefits, boosting local innovation and business start-ups. This initiative supports the emergence of new agricultural formats and entities, impacting rural industrial integration. Upon including these policy effects in the regression model, as shown in column (2) of Table 6, the positive impact of RCCLM on rural development persists, confirming the robustness of baseline findings against other policy influences.

Third, 1% tailing. To mitigate the influence of extreme values on the benchmark regression results, all continuous variables were subjected to a 1% tailing. The re-run of the regression, presented in column (3) of Table 6, shows that the RCCLM regression coefficients remain significant at the 1 percent level, consistent with the benchmark estimates. This indicates that the benchmark results are robust against extreme values.

Fourth, shorten the sample duration. The article initially covers the sample study interval from 2010 to 2022, but since the RCCLM policy identified pilot lists in 2015 and 2016, the authors narrow the sample period to 2012–2020 to minimize the potential impact of errors from years further from the policy shock. As shown in column (4) of Table 6, the regression coefficient of RCCLM on the integrated development of rural industries is 0.0127 and is significant at the 1% level. This indicates that the effect of RCCLM on the integrated development of rural industries is not influenced by the length of the sample period, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

5.7 Mechanism analysis

Building on the theoretical analysis from the previous paper, this study introduces technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity as mediating variables to construct a mediating effect model. Following the standard practice of sequential testing for mediating effects, it regresses Equations 2–4 to explore how RCCLM influences the development of rural industrial integration. First, the results in column (1) of Table 7 indicate that RCCLM has a significant promotion effect on the integrated development of rural industries. Second, the impact of RCCLM on technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity is analyzed. As shown in columns (2) and (3) of Table 7, the estimated coefficients for RCCLM are 0.0201 for technological innovation and 0.0766 for entrepreneurial activity, both of which are significant. This indicates that RCCLM promotes both technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity. Finally, the impact of the mediating variables on rural industrial integration is examined. Columns (4) and (5) of Table 7 present regressions that include technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity, respectively, in addition to the variables in column (1). The results reveal that the regression coefficients for both technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity on the integrated development of rural industries are significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicates that RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration development through both technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity. In summary, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are confirmed.

6 Further analysis

Considering that the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration may differ across various geographical locations and population sizes, and recognizing the strong correlations in spatial geography and economic development among neighboring regions, the benefits of policy implementation may also positively influence surrounding areas. Thus, this paper further explores the heterogeneity and spatial spillover effects of RCCLM on rural industrial integration.

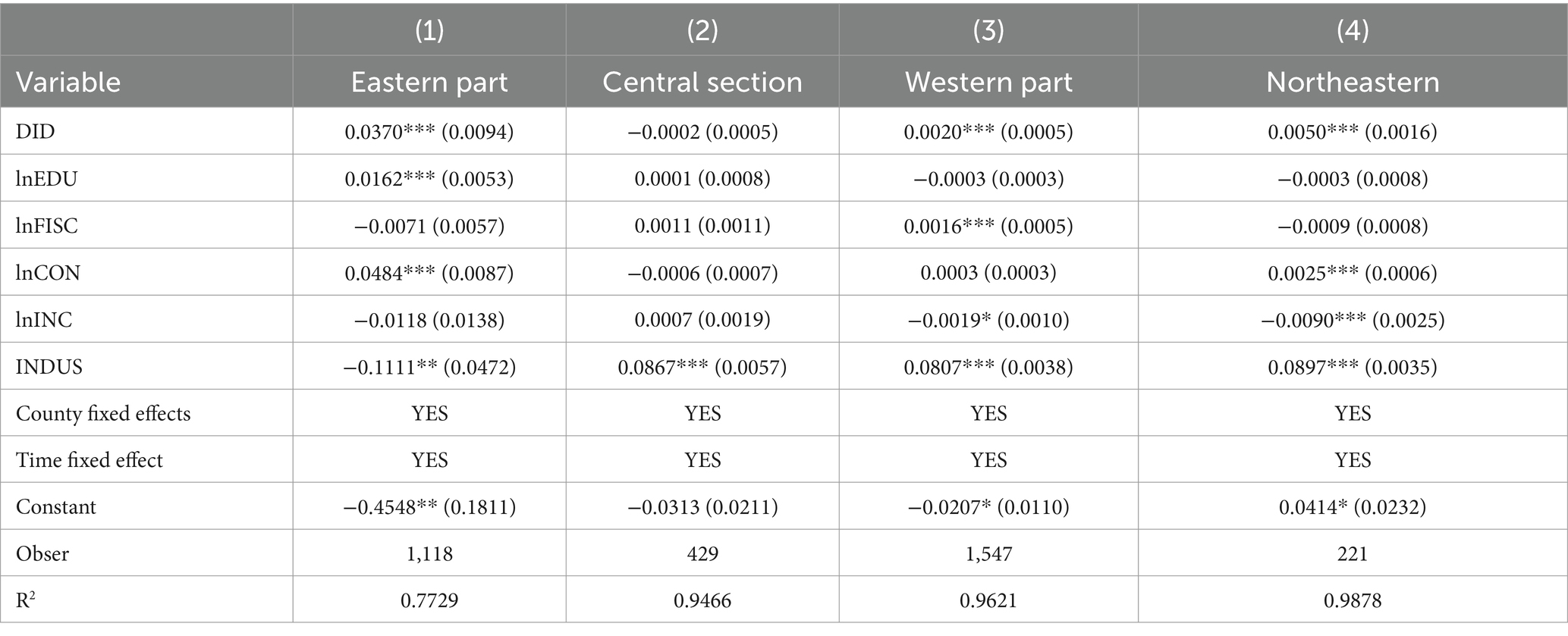

6.1 Heterogeneity analysis

First, considering the unbalanced development across regions in China and the varying resource endowments and economic development models, the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration may differ by geographic location. Therefore, the total sample is divided into four regions—East, central, west, and northeast—for separate regression analyses, with the specific estimation results presented in Table 8. RCCLM demonstrates a significant positive impact on rural industrial integration in the eastern, western, and northeastern regions, but not in the central region. The reason for this disparity may be that collective land transfer first emerged in the eastern coastal region, where a relatively mature trading model has developed through long-term exploration and reform. Additionally, the demand for construction land for industrial development is higher in this area. Therefore, within the RCCLM policy framework, rural areas in the east are more likely to achieve industrial agglomeration, driving rural industrial integration. In contrast, the central region faces challenges due to the concentration of collectively operated construction land primarily in the eastern coastal areas. Moreover, to strengthen farmland protection, the government has prohibited the conversion of agricultural land into new construction land. This has made it difficult for most central regions to acquire newly added rural construction land. As a result, the limited scope of RCCLM in the central region has not significantly promoted rural industrial integration. In contrast, local governments in the economically underdeveloped western and northeastern regions may prioritize leveraging RCCLM to overcome existing resource constraints and achieve improvements in livelihoods and economic performance. Additionally, national policies aimed at promoting Western Development and the comprehensive revitalization of the northeast provide favorable conditions for policy implementation in these areas. As a result, RCCLM facilitates the integrated development of rural industries.

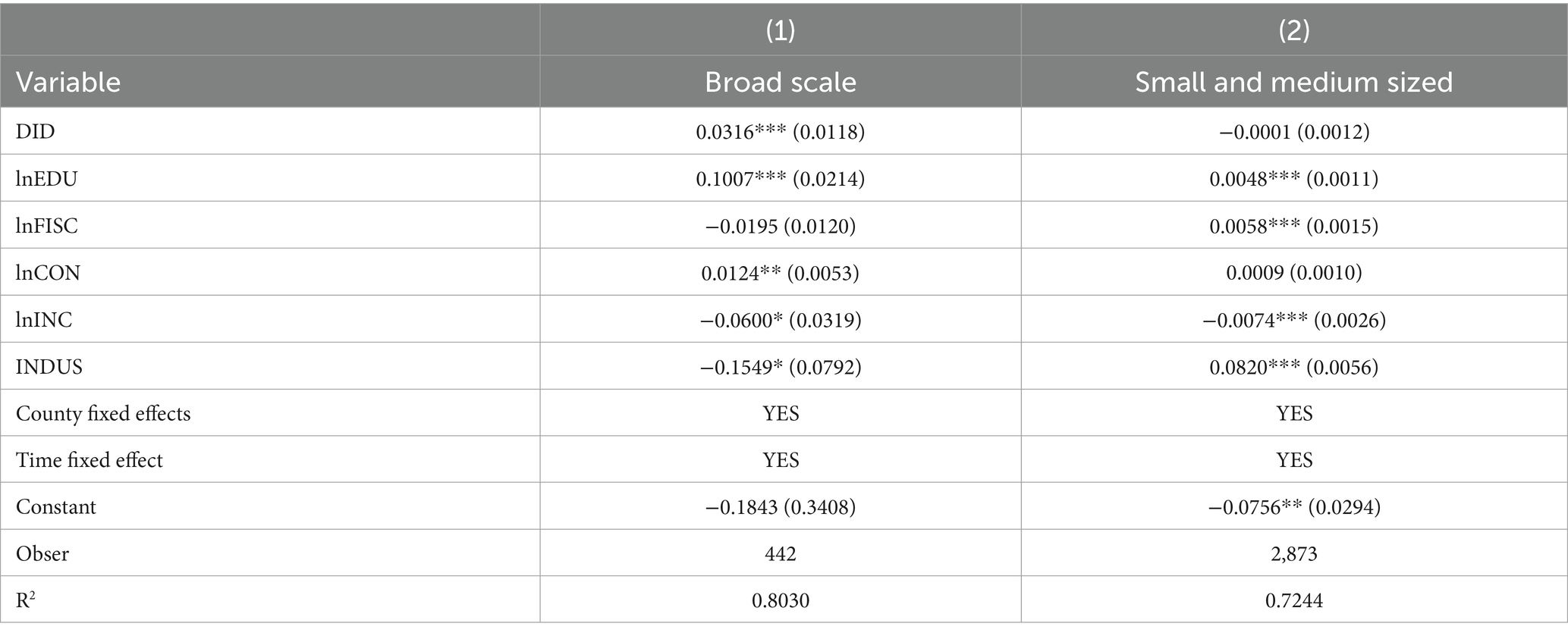

Second, this analysis considers the heterogeneity of impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration based on population size. Counties with a resident population exceeding 1 million are classified as large-scale, while those with a population below 1 million are categorized as medium–small scale. The specific regression results, presented in Table 9, indicate that RCCLM significantly promotes rural industrial integration in large-scale counties, while the effect is not significant in medium–small-scale counties. This disparity may arise because local governments in large-scale areas have a greater demand for industrial development to address employment issues and improve livelihoods. Consequently, when urban construction land supply is insufficient, these governments are more motivated to actively promote RCCLM, allowing more economically efficient enterprises to enter rural areas and facilitating rural industrial integration.

6.2 Spatial spillover effects

The implementation of RCCLM has accelerated the convergence of industrial and commercial capital, human capital, and technical resources in the pilot areas. While this provides essential support for the integrated development of rural industries, the deepening of RCCLM reform may also generate spillover effects on neighboring areas due to the close geographic and resource connections among villages. Therefore, this paper employs a spatial difference-in-differences model to test this hypothesis. The specific model is constructed as follows:

In Equation 6, ρ represents the spatial autoregressive coefficient, and W is the spatial weight matrix, and in this paper, the neighborhood matrix is used for regression. and are the elastic coefficients of the spatial interaction term of the core explanatory variable and the control variable, respectively.

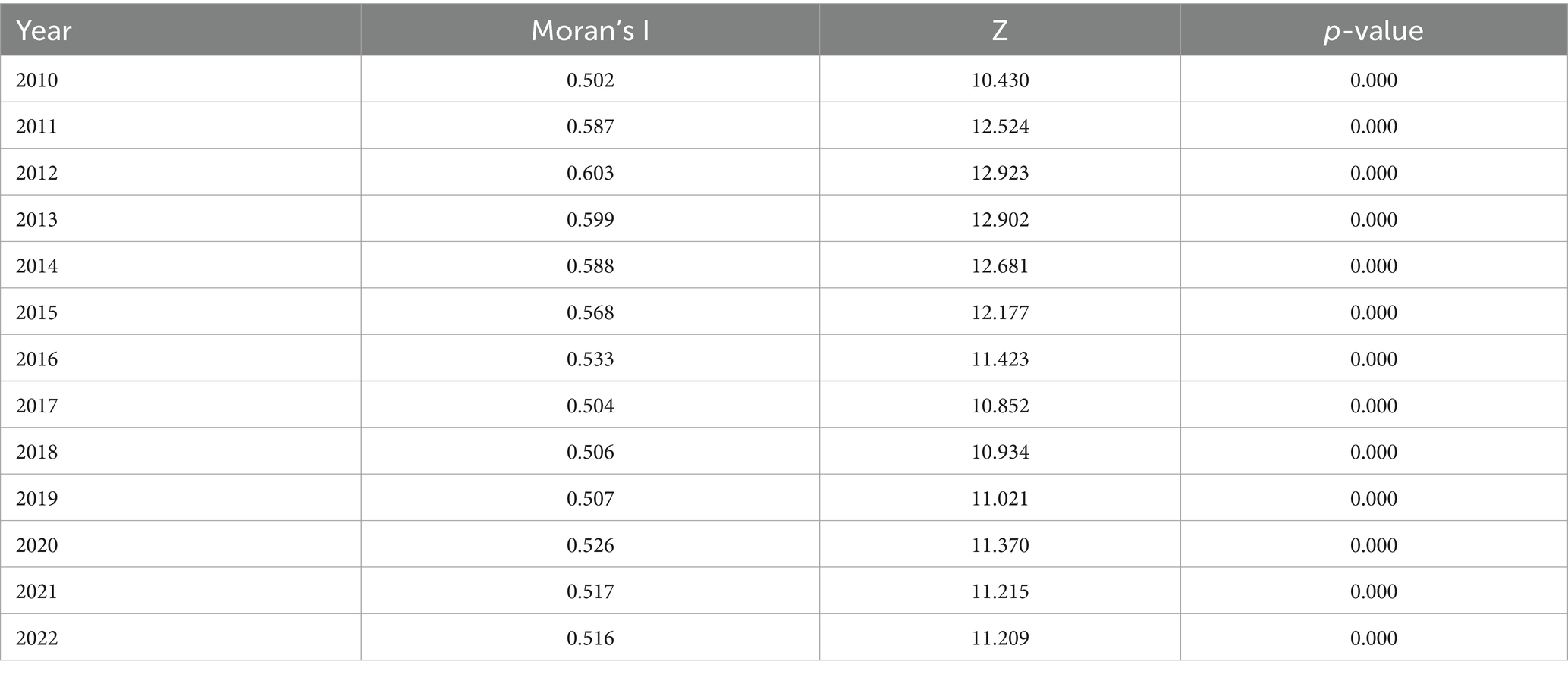

First, the spatial correlation test needs to be carried out by Moran’s I index method. The results are shown in Table 10, under the neighborhood matrix, the Moran’s I indexes of the integrated development of rural industries in the sample counties from 2010 to 2022 are all significantly positive, indicating that the spatial correlation test has been passed.

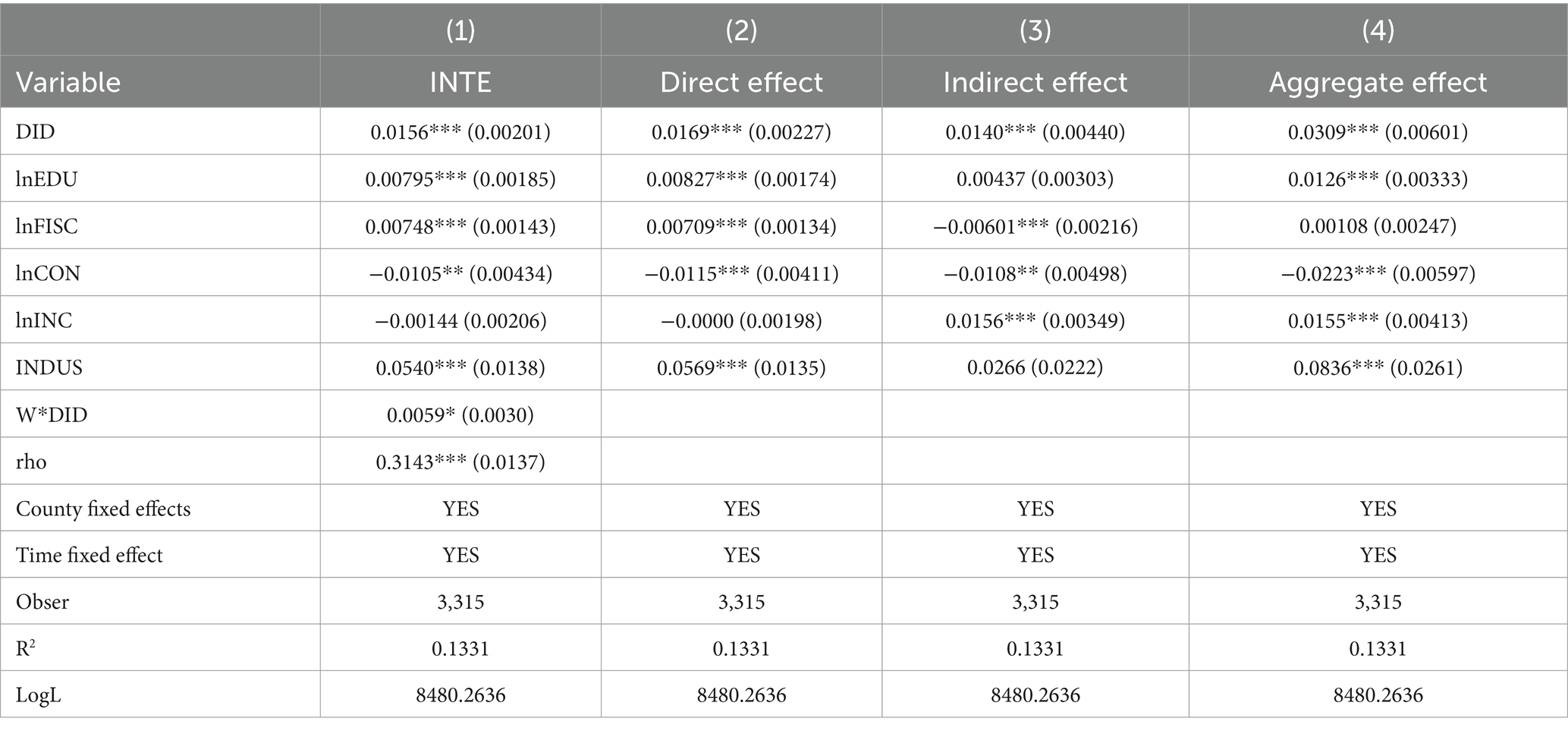

Second, to select the appropriate measurement model, the article sequentially conducts the LM test, LR test, Hausman test, and Wald test. Based on the test results, the study employs a two-way fixed-effects model with a spatial Durbin specification and difference-in-differences model for estimation, as detailed in Equation 6. Regression analysis is then performed, and the results are presented in Table 11. Under the neighborhood matrix, the spatial autocorrelation regression coefficients, ρ and W × DID, for the integrated development of rural industries are significantly positive. This indicates a notable positive spatial correlation in the integrated development of rural industries across regions and confirms that RCCLM has a significant positive spatial spillover effect on rural industrial integration in neighboring areas.

However, analyzing the spatial spillover effect between regions solely through simple point regression may introduce estimation bias. Therefore, to examine the spatial effect of RCCLM on the integrated development of rural industries more precisely, the coefficients of RCCLM in the SDM model are further decomposed into direct, indirect, and total effects through partial differentiation. The results in Table 11 indicate that the indirect effect of RCCLM on the integrated development of rural industries is significantly positive, suggesting that RCCLM generates strong positive externalities and enhances the level of rural industrial integration in neighboring areas through spatial spillover effects.

7 Conclusion and implications

This paper leverages the RCCLM as an opportunity to construct a quasi-natural experiment. Utilizing panel data from 255 counties in pilot areas across China from 2010 to 2022, it employs a multi-period difference-in-differences model to systematically evaluate the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration. The following research conclusions have been drawn, and based on these findings, relevant policy recommendations are proposed.

7.1 Conclusion

Rural industrial integration is a crucial exploration for enhancing the level of rural industrialization and achieving rural revitalization. This paper examines the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration and presents the following conclusions: first, pilot areas experienced a significant 1.47% increase in rural industrial integration compared to non-pilot areas. The conclusion remains robust after a series of tests. It highlights the positive economic effects of RCCLM and identifies the key driving factors behind rural industrial integration. Second, county-level technological innovation and entrepreneurial activity serve as mediators in the process through which RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration. This finding clarifies the pathways by which RCCLM drives rural industrial integration. Third, the heterogeneity analysis shows that there is heterogeneity in the impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development under different conditions of spatial geographic location and population size. Specifically, it shows significant reform effects in the eastern, western, and northeastern regions as well as in counties with larger population sizes, while it is not significant in the central region and in counties with smaller population sizes. Therefore, when implementing RCCLM, the government should adopt a context-specific approach. Fourth, through the sharing of resource elements, the policy exhibits a positive spatial spillover effect on the development of rural industrial integration in neighboring areas. This further expands the research results of the spatial effect of RCCLM policy.

However, this study has certain limitations. First, collecting data on rural industrial integration at the county level in China are challenging. Professional databases, the China County Statistical Yearbook, and various local statistical yearbooks sometimes do not have completely identical statistic caliber, leading to slight differences in some data. Additionally, to address missing statistical data for certain years in the yearbooks, this paper uses interpolation or averaging methods to fill in the gaps. While these methods reasonably supplement the missing data, they may still result in a decrease in the accuracy of some estimation results. For future research, more in-depth exploration and analysis based on regional heterogeneity may be possible. Specifically, while this paper clarifies the mechanism through which the RCCLM promotes rural industrial integration development, it must be noted that the development situations in different regions and the specific practices of local governments in implementing policies are not completely identical, which means that the underlying mechanisms may also differ. Therefore, future research can explore differentiated paths within different regional contexts. To fully leverage the positive impact of RCCLM on rural industrial integration development, a more comprehensive study and empirical analysis of its basic mechanisms are needed.

7.2 Policy implications

First, a sound policy system for RCCLM should be established. On the one hand, a reasonable mechanism for the distribution of land value-added gains should be actively explored, so that, while taking into account the need to increase the motivation of local governments to promote RCCLM, more land value-added gains can be used for agricultural and rural development, increasing the sustainability of rural residents’ earnings and providing financial support for the integrated development of rural industries. On the other hand, local governments should focus on the linkage between policies. In the context of rural homestead system reform, policies should be designed to incentivize farmers to voluntarily withdraw from their compliant homesteads and convert them into rural construction land that can participate in the market. This would further expand the pool of land available for marketization, allowing the policy dividends of RCCLM to be fully leveraged to promote rural industrial integration development.

Second, efforts should be made to promote the development of technological innovation and entrepreneurial activities, and fully leverage their intermediary role in the impact of RCCLM on the integration of rural industries. In terms of technological innovation, local governments should focus on the goal of establishing a unified urban–rural construction land market to enhance the competitiveness of the land market. This would compel enterprises to strengthen their innovation efforts to improve economic performance. Concurrently, local governments should increase investment in the infrastructure surrounding rural collective construction land, and maintain the price advantage of rural construction land in transactions, thereby reducing enterprises’ initial operating costs and incentivizing greater innovation investment. Furthermore, on the basis of identifying the leading industries and existing resource conditions at the county level, innovative technologies should be closely matched with the local rural industrial development plan to provide technical support for the integrated development of rural industries. In terms of enhancing entrepreneurial activities, farmers should be prioritized in the distribution of land value-added income from RCCLM, in order to alleviate the problem of insufficient start-up capital. Additionally, local governments should actively encourage the labor force to return to their hometowns for entrepreneurship. When trading rural construction land, they can set certain conditions to moderately favor high-quality returnees who start businesses, effectively combining the personal capital advantages of these entrepreneurs with the local agricultural development characteristics and resource advantages. This will enhance the success rate of entrepreneurs and inject endogenous impetus into the rural industrial integration development at the county level.

Third, the reform of RCCLM should be promoted according to local conditions. RCCLM has not yet played a significant role in promoting rural industrial integration development in the central region or in small- and medium-sized areas. Therefore, in the central region, in the process of promoting RCCLM, we should avoid “one-size-fits-all,” give local governments a certain degree of discretionary space through moderate decentralization by the central government, allow the adoption of differentiated reforms, moderately expand the source of new construction land, alleviate the predicament of insufficient stock of construction land, and insist on land transactions oriented to the development needs of the regional rural industry, thus promoting rural industrial integration development. For small- and medium-sized areas, local governments should further improve the relevant supporting policies for RCCLM and strengthen the improvement of the land parcels entering the market as well as the construction of the surrounding infrastructure, so as to increase the value of the land parcels entering the market and make them more attractive to enterprises and investor, and thus provide capital and industrial infrastructure support for the integrated development of rural industries.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. JY: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (fund number: 72303062), the project of Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education (fund number: 22YJC790007), and the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Program (fund number: 2021JJ40263).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1499577/full#supplementary-material

References

An, Y., and Zhao, L. (2021). Land resource mismatch, spatial strategy interaction and urban innovation capacity. China Land Sci. 35, 17–25. doi: 10.11821/dlxb202004003

Chen, X. (2020). The core of China's rural revitalization: exerting the functions of rural area. China Agr. Econ. Rev. 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1108/CAER-02-2019-0025

Chen, K., and Long, H. (2019). Impact of China's land market on urban-rural integration development. J. Nat. Resour. 34, 221–235. doi: 10.31497/zrzyxb.20190201

Chen, L., Xie, B., Zhou, Z., and Wu, H. (2024). Whether digital village construction promotes rural industrial integration - causal inference based on dual machine learning. Financ. Econ. 5, 60–70. doi: 10.19622/j.cnki.cn36-1005/f.2024.05.006

Cheng, L., and Kong, F. (2020). Measurement and influencing factors of rural industrial integration development level in the upper Yangtze River. J. Stat. Inform. 35, 101–111. doi: 10.16398/j.cnki.1004-0075.2020.01.015

Ding, K., Ma, Z., and Tao, W. (2024). Research on the impact of rural digital economy on farmers' income and spatial heterogeneity. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 38, 90–99. doi: 10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2024.101

Gong, G., Wu, Q., and Gao, S. (2020). The impact and role mechanism of land marketization on regional technological innovation. Urban Probl. 3, 68–78. doi: 10.13239/j.bjsshkxy.cswt.200308

Guo, C. (2023). Evolution of industrial organization in the era of digital economy: trends, characteristics and effects. China Rural Econ. 10, 2–25. doi: 10.19690/j.cnki.cnrjy.2023.10.002

He, S., Fang, X., and Yang, G. (2022). Can comprehensive land consolidation promote the transformation of rural industries?—— evidence from some rural areas of Hubei Province. China Land Sci. 36, 107–117.

Huang, H., Li, J., and Sun, C. (2024). Shock" or "supplement":the impact of collective construction land market entry on local government land finance: An empirical analysis based on double difference model. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 7, 1–18. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.jae.20231206.001

Huang, Y., Zhao, J., and Yin, S. (2023). Does digital inclusive finance promote the integration of rural industries? Based on the mediating role of financial availability and agricultural. PLoS One 18:e0291296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291296

Jiang, Z. (2021). Re-exploration of the integrated development of rural one, two and three industries. Iss. Agr. Econ. 6, 8–18. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.iae.2021.06.003

Jiao, Q. (2023). Analysis of the impact effect of rural industrial integration on rural common wealth. Stat. Decis. 39, 30–34. doi: 10.13546/j.cnki.tjyjc.2023.15.005

Khan, I., Lei, H., Shah, A., Ali, I., Khan, I., Muhammad, I., et al. (2020). Farm households’ risk perception, attitude and adaptation strategies in dealing with climate change: promise and perils from rural Pakistan. Land Use Policy 91:104395. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104395

Kvartiuk, V., Bukin, E., and Herzfeld, T. (2024). “For whoever has will be given more”? Land rental decisions and technical efficiency in Ukraine. Land Use Policy 146:107336. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2024.107336

Li, M., and Cai, J. (2023). The impact of rural collective operating construction land into the market on the income gap between urban and rural residents. Acad. Mon. 55, 49–60. doi: 10.19862/j.cnki.xsyk.000722

Li, X., and Ran, G. (2019). How the integrated development of rural industries affects the urban-rural income gap-based on the dual perspective of rural economic growth and urbanization. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 8, 17–28. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2019.08.002

Li, J., and Song, X. (2018). Analysis of the factors of collective construction land affecting the improvement of agricultural labor productivity. Mod. Manag. 38, 15–18. doi: 10.19634/j.cnki.11-1403/c.2018.01.005

Li, Z., Yan, H., and Liu, X. (2023). Evaluation of China's rural industrial integration development level, regional differences, and development direction. Development direction. Sustainability 15:2479. doi: 10.3390/su15032479

Li, B., Zhao, J., and Jin, T. (2023). How returning to home town entrepreneurship promotes the upgrading of county industrial structure-a quasi-natural experiment based on policy pilot. J. Huazhong Agr. Univ. 3, 34–43. doi: 10.13300/j.cnki.hnwkxb.2023.03.004

Lin, S., Gu, C., Si, X., and Yan, Y. (2023). County entrepreneurial activity, Farmers' income increase and common wealth - an empirical study based on county-level data in China. Econ. Res. J. 58, 40–58. doi: 10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2023.03.003

Linkous, E. (2016). Transfer of development rights in theory and practice: the restructuring of TDR to incentivize development. Land Use Policy 51, 162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.10.031

Long, H., and Tu, S. (2018). Land use transformation and rural revitalization. China Land Sci. 32, 1–6. doi: 10.11994/zgtdkx.20180702.095544

Lu, S., and Wang, H. (2024). Evaluation of the market reform effect of collective operational construction land —— the perspective of market subject growth. Economics 24, 1358–1372. doi: 10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2024.04.20

Meng, W., Zheng, S., and Liu, J. (2023). Influence mechanism and empirical test of digital economy to promote rural industrial integration. Theor. Pract. Financ. Econ. 44, 84–91. doi: 10.16339/j.cnki.hdxbcjb.2023.05.011

Mi, X., and Dai, D. (2020). Rural collective construction land transfer and industrial structural adjustment-a natural experimental study based on land ticket system. Econ. Perspect. 3, 86–102. doi: 10.19523/j.jjxdt.2020.03.007

Moffette, F., Phaneuf, D., Rausch, L., and Gibbs, K. (2024). The value of property rights and environmental policy in Brazil: evidence from a new database on land prices. Glob. Environ. Chang. 87:102854. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2024.102854

Pang, J., and Wu, N. (2023). Research on the influence effect and mechanism of digital inclusive finance on rural industry integration development. J. Hubei Minzu Univ. 41, 94–103. doi: 10.13501/j.cnki.42-1328/c.2023.02.010

Qiu, S., and Teng, J. (2024). An empirical test of the impact of digital economy on the integrated development of rural three industries. Stat. Decis. 40, 67–72. doi: 10.13546/j.cnki.tjyjc.2024.05.012

Qiu, Y., and Zhao, T. (2015). Analyzing the mechanism and influencing factors of FDI technology spillovers-demonstration effect. Mod. Econ. Inform. 20, 124–125. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-828X.2015.20.075

Qu, C., and Ren, D. (2018). On the impact of collective operational construction land entering the market on rural development. China Land Sci. 32, 36–41. doi: 10.11994/zgtdkx.20180707.095549

Radmehr, R., Shayanmehr, S., Baba, A., Samour, A., and Adebayo, S. (2023). Spatial spillover effects of green technology innovation and renewable energy on ecological sustainability: new evidence and analysis. Sustain. Dev. 32, 1743–1761. doi: 10.1002/SD.2738

Shen, X., He, N., and Li, Z. (2023). Problems and path selection of rural industry integration development. Fisc. Sci. 9, 87–94. doi: 10.19477/j.cnki.10-1368/f.2023.09.003

Shen, D., Zhou, X., Xie, S., Lv, X., Peng, W., Wang, Y., et al. (2024). Paths and mechanisms of rural transformation promoted by rural collectively owned commercial construction land marketization in China. Land 13:416. doi: 10.3390/land13040416

Sun, D., Mei, Y., and Yang, X. (2024). Can the construction of modern agricultural parks promote rural industrial integration-empirical evidence based on 8,325 agricultural parks in China. China Rural Surv. 3, 39–61. doi: 10.20074/j.cnki.11-3586/f.2024.03.003

Tzounis, A., Katsoulas, N., Bartzanas, T., and Kittas, C. (2017). Internet of things in agriculture, recent advances and future challenges. Biosyst. Eng. 164, 31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.09.007

Wang, S., and Chen, X. (2023). Impact of rural collective operating construction land entering the market on urban land use efficiency. China Land Sci. 37, 113–122. doi: 10.11994/zgtdkx.20230112.095925

Wang, X., Ma, Y., Li, H., and Xue, C. (2022). How does risk management improve farmers’ green production level? Organic fertilizer as an example. Front. Env. Sci. 10:946855. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.946855

Wang, K., Yang, Y., Liu, H., and Liu, Z. (2023). Study on the impact of collective operational construction land entering the market on urban-rural integration development. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 2, 45–63. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2023.02.001

Yan, M., and Cao, X. (2024). Digital economy development, rural land certification, and rural industrial integration. Sustain. For. 16:4640. doi: 10.3390/su16114640

Yan, H., Wang, J., and Sun, J. (2023). How does the market entry of collective construction land affect the state-owned construction land market? --new evidence based on machine learning. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 40, 195–216. doi: 10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.20230413.002

Yang, Q., Yang, R., Zeng, L., and Chen, Y. (2017). Research on the market entry of rural collective operational construction land to promote the growth of farmers' land property income--taking Pidu District of Chengdu City as an example. Econ. Geogr. 37, 155–161. doi: 10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2017.08.020

Yu, J., and Ge, Y. (2023). Agricultural land transfer, rural industry integration and Farmers' income growth. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 45, 78–93. doi: 10.13781/j.cnki.1007-9556.2023.09.006

Yuan, X., and Sun, W. (2024). Research on the mechanism of digital economy affecting rural industrial integration--an empirical study based on Chinese provincial panel data. J. Manag. 37, 143–158. doi: 10.19808/j.cnki.41-1408/F.2024.0029

Yuan, H., and Xia, J. (2022). Research on the impact of digital infrastructure construction on the structural upgrading of China's service industry. Econ. Rev. J. 6, 85–95. doi: 10.16528/j.cnki.22-1054/f.202206085

Zeng, L., Chen, S., and Fu, Z. (2022). Influence and mechanism of land scale operation on rural industrial integration development. Resour. Sci. 44, 1560–1576. doi: 10.18402/resci.2022.08.03

Zhang, H., and Dong, L. (2022). The impact of transport infrastructure on rural industrial integration: spatial spillover effects and Spatio-temporal heterogeneity. Land 11:1116. doi: 10.3390/land11071116

Zhang, L., and Wen, T. (2019). Financial and financial services synergy and rural industrial integration development. Financ. Econ. Res. 34, 53–67. doi: 10.13762/j.cnki.jfe.2019.05.005

Zhang, L., and Wen, T. (2022). How digital inclusive finance affects the development of rural industrial integration. Chin. Rural Econ. 7, 59–80. doi: 10.19616/j.cnki.1006-0434.2022.07.04

Zhang, Y., and Zhou, Y. (2021). Digital inclusive finance, traditional financial competition and rural industrial integration. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 9, 68–82. doi: 10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2021.09.005

Zhao, W., Zhu, P., and Yu, J. (2023). Study on the impact of collective operational construction land market entry on rural-urban integration and development: empirical evidence based on the reform pilot in Deqing County, Zhejiang Province. China Land Sci. 37, 42–52. doi: 10.11994/zgtdkx.20230112.181426

Zhuang, J., Rui, Z., and Zeng, J. (2014). The effects of dual network embeddedness and access to entrepreneurial resources on the entrepreneurial ability of migrant workers-an empirical analysis based on 183 migrant worker entrepreneurship samples from Gan, Anhui and Suzhou. China Rural Surv. 3, 29–41.

Keywords: rural collective construction land marketization, rural industrial integration, technological innovation, entrepreneurial activity, China

Citation: Zeng L, Zhang Y and Yao J (2024) Has rural collective construction land marketization promoted rural industrial integration development? An empirical study based on county-level data in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1499577. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1499577

Edited by:

Sérgio António Neves Lousada, University of Madeira, PortugalReviewed by:

Aditya Singh, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham University, IndiaMajid Ali, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2024 Zeng, Zhang and Yao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yilu Zhang, MTUwMjMzNjg5NkBzdHUuaHVuYXUuZWR1LmNu

Long Zeng

Long Zeng Yilu Zhang

Yilu Zhang