- Social Sciences Vocational School, Tourism Management, Atatürk University, Erzurum, Türkiye

Erzurum Rosette holds significant cultural value as a traditional dessert widely produced and consumed in Erzurum. Limited knowledge exists regarding the difficulties encountered by producers and the influence of Geographical Indication (GI) registration on production and marketing. This study aims to enhance the recognition of Erzurum Rosette, assess its production process to comply with the standards of the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TPTO), and explore its potential as a sustainable tourist product. A qualitative analysis was conducted on six producers of Erzurum Rosette. The information was gathered through semi-structured interviews that focused on demographic data, understanding GI, production challenges, and the influence of GI registration on sales. Responses were examined using thematic coding and statistical analysis. The study revealed that this traditional dessert production involves both male and female producers and that the producers have significant professional experience. General materials for production can be easily obtained, but obtaining the necessary special iron molds poses a significant challenge. Producers with a comprehensive understanding of GI have reported increased sales and market access after registration, but those with limited understanding have seen minimal impact. Common challenges include material supply and equipment availability, particularly regarding the procurement of iron molds. Sales and marketing strategies are generally effective, but continuous innovation is necessary for market expansion. Addressing supply chain issues and increasing awareness of GI benefits for producers are crucial for the sustainability and promotion of Erzurum Rosette. Improving support for local production and targeted training initiatives can help preserve traditional production methods and enhance the potential of Erzurum Rosette as a cultural and tourism value.

1 Introduction

Culture, traditions, and heritage, as well as the sustainability of these key elements, constitute the essential elements in forming various types of tourism and determining tourism strategies (Haberle, 2021). The relationship between culture and food and the tourism movement and travel directed to the regions where these foods are produced to toward the regions where these foods are produced (Mulyantari et al., 2023). The traditional cuisines and food products associated with these local cuisines, which are among the cultural elements of destinations, have recently attracted the attention of tourists (Du Rand et al., 2013). This cultural heritage has sparked a desire for food among travelers through gastronomic experiences (Torres Bernier, 2003). Therefore, local gastronomy has become a fundamental tool for the development of tourism in a destination today (Nicoletti et al., 2019).

Gastronomy tourism can be defined as special interest tourism that appeals to the five senses of sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste while allowing tourists to experience local flavors and get to know the residents. Furthermore, this type of tourism, which provides tourism to be distributed throughout the year, also attracts experience-oriented tourists by appealing to individuals who are curious and in pursuit of culinary discoveries, encouraging them to focus on flavors and the regions where they are produced (Kivela and Crotts, 2006; Şeyhanlıoğlu, 2023). Additionally, it showcases the local culture and traditional cooking methods in conjunction with environmental factors while providing information about gastronomy tourism, history, and the origin of traditional products (Damayanti and Bagiastra, 2022). With this support, gastronomy tourism adds value to the destination with its unique products compared to its competitors, and enhances the region’s tourism image by adding attraction to these authentic products (Haven-Tang and Jones, 2005). In fact, there are also examples of past studies showing that the main factor determining tourist preferences and primary motivation is local cuisine and specific products (Kivela and Crotts, 2006; Dancausa Millán et al., 2021).

Local or traditional foods and beverages are tangible examples that provide information about a locality or region’s cultural identity, historical background, and heritage. These unique flavors can contribute to the destination’s economy and support preserving its distinct culture. As Antón et al. (2019) also pointed out, it can be seen as an important element of the tourist experience that can simultaneously enhance the attractiveness and brand image of the destination. According to Richards (2012), gastronomy tourism, which includes culinary experiences, economically supports rural areas by increasing their attractiveness and creating new employment opportunities. It also contributes to sustainability by strengthening the local environment and cultural heritage, fostering a sense of community among the local people, and diversifying tourism to extend the season. The importance of gastronomic products is evident here, and the four characteristics that these particular products should have can be listed as uniqueness, authenticity, originality, and differentiation from similar ones (Mulyantari et al., 2023). Discovering and revealing these local products with the aforementioned characteristics and bringing them into gastronomy tourism is vital for culinary destinations and is an increasingly considered factor in touristic destination selection (López-Guzmán et al., 2017). Because local flavors affect tourists’ choice of destination, as well as contribute to the tourism experience and trigger economic development (Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2014).

2 Existing literature

Geographical indication is a quality mark that indicates and guarantees to consumers the origin of the product, its characteristics and the link between these characteristics of the product and the geographical area. According to the legislation in Turkey, food, agriculture, mining, handicrafts and industrial products can be subject to geographical indication registration. There are two basic classifications: Designation of Origin and Geographical Indication. Appellation of origin is registered when the production, processing and other operations of a product take place entirely within the boundaries of the designated geographical area. For the registration of geographical indication, at least one of the production, processing or other operations identified with a particular geographical area must take place within the designated geographical area. The only authorized institution regarding geographical indications is the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (Tekelioğlu, 2019).

Past studies have focused on the culinary culture of a region, area or destination in general (Bukharov and Berezka, 2018; Cherro Osorio et al., 2022; Santa Cruz et al., 2019; Mora et al., 2021), drawing attention to festivals on food or food products (Folgado-Fernández et al., 2017; López-Guzmán et al., 2017) and compares regional culinary cultures (Akdag et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2022; Oğan et al., 2024). In addition, there are studies that aim to identify the key factors of visitors’ gastronomy experiences (Moral-Cuadra et al., 2023; Kovalenko et al., 2023), as well as studies that focus specifically on a product and suggest evaluating it within the scope of gastronomy tourism (Čaušević and Hrelja, 2020; Murgado, 2013; Fusté-Forné, 2020). Some studies focused on the production methods of traditional products and geographical indication registered products and pointed out the various difficulties encountered in the production of these products (Balderas-Cejudo et al., 2020; Cei et al., 2018; Oğan and Çelik, 2023). However, there is a significant gap in the literature regarding a specific product for the robust cuisine of Erzurum in Turkey.

Although Erzurum is a well-known destination for winter tourism in Turkey (Daştan et al., 2016; Sezen and Külekçi, 2020), it has also started to participate in gastronomy tourism with its traditional flavors (Şengül, 2017; Daşdemir et al., 2021) and arouse curiosity in tourists. The development of studies emphasizing the culinary authenticity of dishes is of great importance. Therefore, Erzurum’s significant gastronomy tourism potential (Denk, 2023) must be supported and made more attractive through specific products. This view constitutes the purpose and basis of the present study.

Erzurum, the study area located in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey (Figure 1), is known for its winter tourism in Turkey, but it has also come to the forefront in recent studies with its local cuisine and gastronomic products (Denk, 2023; Şengül, 2017; Üzümcü et al., 2017).

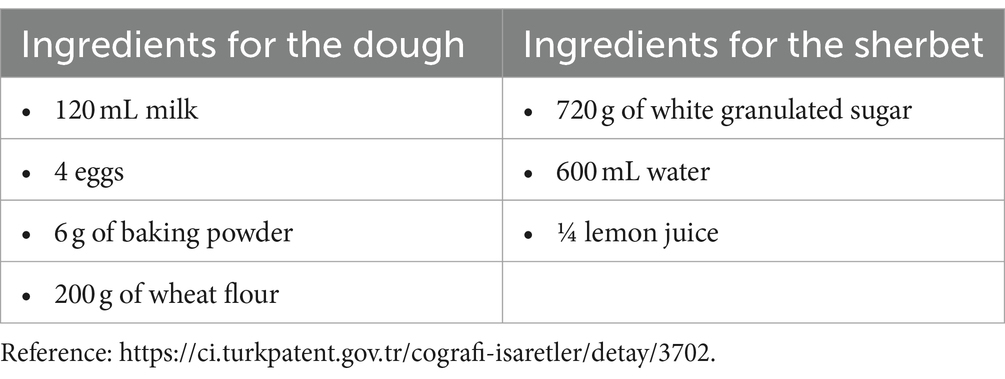

Erzurum cuisine is primarily known for its cağ kebab among meat products, but also stands out for its civil cheese and moldy civil cheese in dairy products, as well as İspir, Narman, and Hınıs dried beans from three different districts in agricultural products. Recently, alternative flavors have been introduced in desserts, such as kadayıf dolması and Erzurum Rosette, to complement the richness of flavors. These products are protected by geographical indication registration applications; however, iron sweet is not well known among these products and is not considered within the scope of gastronomy tourism. However, no studies have been conducted on this topic in the literature. This study focused on the authenticity of the Erzurum Rosette and aimed to examine its production process according to the information in the geographical indication registration certificate. It also aims to promote its introduction, observe sales and marketing strategies, and encourage its evaluation within the scope of gastronomy tourism to support its sustainability. First, the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office (TPTO) records, which have the highest authority in geographical indication (GI) applications in Turkey, were examined. Erzurum Rosette received official registration as a geographical indication on December 27, 2021. The registration document indicates the necessary materials for production and the production method1 (Table 1).

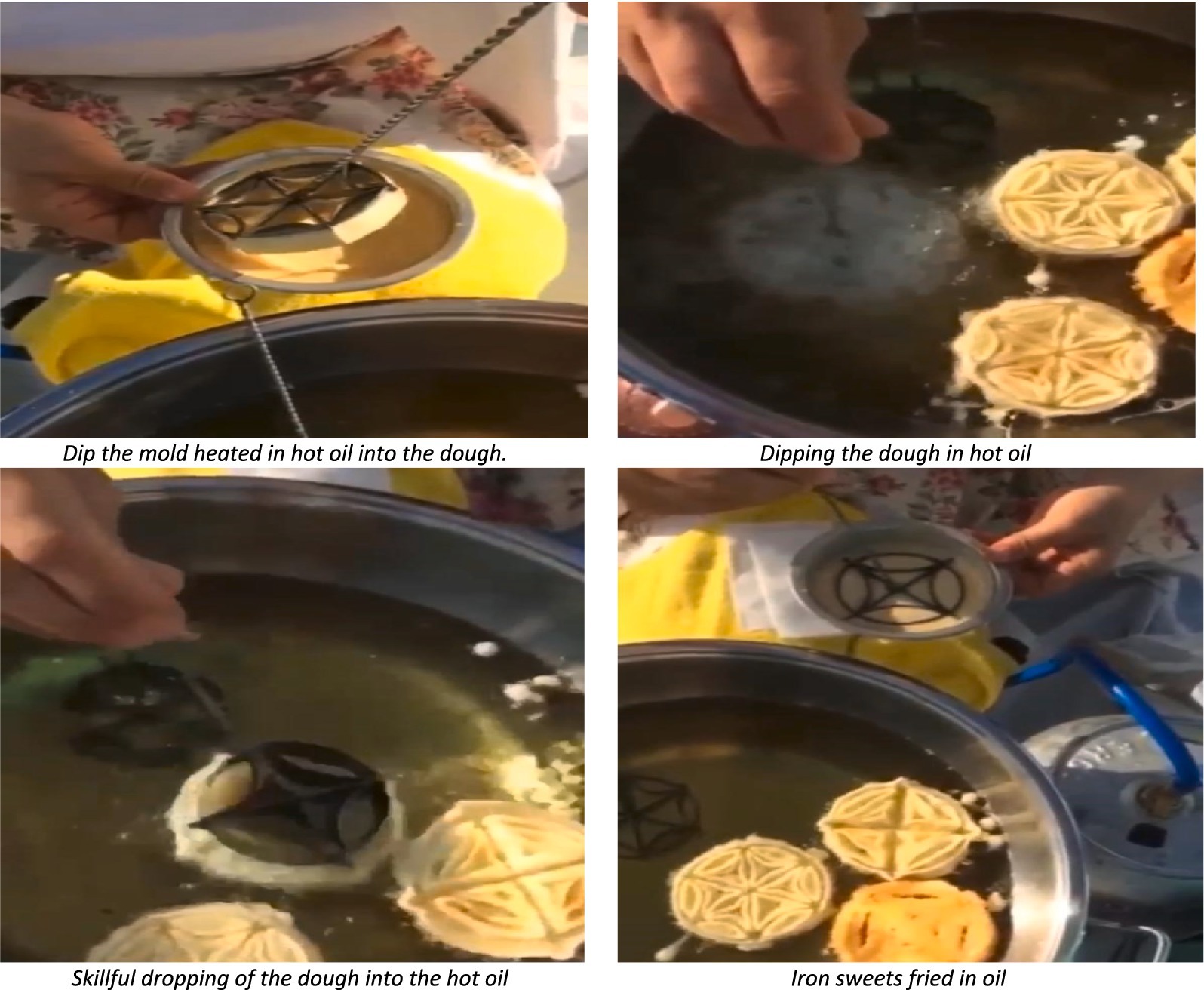

Milk, eggs, baking powder, and wheat flour were used for dough preparation. For sherbet, water, sugar, and lemon juice. Vegetable oil was used for frying. The dough was obtained by mixing all the ingredients until it reached pancake batter consistency. A large amount of oil was placed in a deep pan and heated, and a special mold was left in the oil for heating. When the oil was hot, the mold was removed and dipped into the dough, leaving little space from the top so it did not go over the mold. The hot mold was surrounded, and the dough was dipped into oil. The mold was separated from the dough by skillfully shaking it. When the dough was fried on both sides, it was removed from the oil and placed on a plate. Then pour warm syrup over it. It was served with crushed walnuts.

3 Materials and methods

The primary purpose of this study is to uncover the production process of Erzurum Rosette, which is registered with geographical indications and has recently gained increasing recognition in Erzurum’s culinary culture. The aim is to contribute to sustainability by creating a record and promoting its use as a tourist product. In this context, the opinions of the producers of Erzurum Rosette, which is included in the records of TPTO, which is the authority in registering geographical indications in Turkey, were consulted. In this study, a qualitative research method (Ishtiaq, 2019) was preferred in order to elucidate the views of the participants in depth and to determine their behaviors exploratively; the data were obtained through an interview form developed based on the literature and using employing a widely used interview technique. In the interview, the producers were asked about the duration of their production of Erzurum Rosette, from whom they learned the production process, the ingredients used in production, any special techniques employed, serving methods, the concept of geographical indication, changes in sales after the registration of the geographical indication, and any production-related challenges they may have encountered. The sample group in the research consists of seven producers and these 7 producers are included in the registration document records. However, one producer refused to participate in the study and the rate of access to the population was 85.7%. The sample group in the study consists of 6 producers included in the TPMK registration certificate records. The small sample size is related to the limited number of Erzurum Rosette producers and the willingness of all producers with registration certificates to participate in the study. Qualitative research with small sample groups is often preferred in studies that aim to obtain in-depth information in a specific field (Spina et al., 2023). Small sample sizes can be used to obtain in-depth information and quality data, especially in cases where there is a limited number of experts or producers representing a niche area (Di Vita et al., 2023). As the study aims at documenting the production process of a GI registered product such as Erzurum Rosette, the importance of data obtained from respondents specialized in a specific field is even more important. In this context, the selection of a small sample group should be considered in accordance with the aim of the study to collect in-depth and detailed data. The study codes the producers as P1 to P6. Face-to-face interviews conducted within the scope of the study were recorded with the permission of the producers and transcribed with the notes taken. In addition, the Erzurum Rosette production stages were photographed and explained in the findings section.

Permission from the ethics committee to conduct interviews with the study participants was obtained from the Atatürk University Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Committee, with decision number 91 in the 7th session held on 18.03.2024.

Interviews with Erzurum Rosette producers were conducted face-to-face in their enterprises between 25.03.2024 and 10.04.2024, and lasted an average of 35 min. The production stages were recorded through videos and photos during visits to businesses, with the producers’ permission. Data were collected through interviews and other records.

3.1 Data analysis

The data analysis of this study was conducted using a meticulous combination of thematic analysis and qualitative data interrogation techniques to gain an in-depth understanding of the Erzurum Rosette production process and its cultural significance. The data analysis methods employed in the study were meticulously selected to both illuminate the nuances of the data set and to gain deeper insights into the challenges and opportunities encountered by the producers.

First, the data from the semi-structured interviews were transcribed and the narratives of each producer were organized into a format suitable for thematic analysis. In the process of thematic analysis using NVivo software, the data were initially coded and categorized into categories such as the detailed steps of the production process, materials used, historical narratives, and challenges faced by the producers. The coding process was designed to identify critical themes in the Erzurum Rosette production process, which was one of the primary objectives of the research.

During the process of thematic analysis, the themes derived from the perspectives of the producers were hierarchically structured and grouped under similar codes. This structure revealed common themes and differences in the producers’ narratives, taking into account the sequence of production steps and thematic coherence. To ascertain which stages and concepts the producers attach the greatest importance to during the production process, word frequency queries were employed to identify the terms and expressions most frequently mentioned. This method facilitated a more nuanced comprehension of the producers’ perspectives on specific elements of the Erzurum Rosette production process and cultural heritage.

A sensory analysis was employed to evaluate the perceptual and commercial consequences of GI registration on Erzurum Rosette. In this analysis, the emotional responses of producers to changes in their sales after registration were identified through the use of thematic coding. The intensity of these responses was also assessed. For instance, the producers’ statements regarding the impact of registration on their sales were classified according to whether they expressed positive, neutral, or negative emotions. This analysis facilitated an understanding of the impact of GI registration on producers.

In addition, the relationships between the themes obtained through matrix coding inquiries and the demographic characteristics and production experience of the producers were analyzed. In this context, using NVivo’s matrix coding feature, correlations and relationships between demographic variables (e.g., age, production experience) and the identified themes were analyzed in depth. This method was used to reveal the impact of the demographic characteristics of the producers on the challenges they face and their production processes.

4 Results

Erzurum qualitative data from interviews with Erzurum Rosette producers provide a comprehensive analysis. The main objective of this study was to explore the cultural significance, production processes, and sustainability of this traditional dessert.

The analysis presents producers’ demographics, production experiences, learning sources, historical and cultural narratives, production processes, presentation practices, notions of Geographical Indication (GI), impact on sales after GI registration, and production challenges. This structured approach facilitates a detailed understanding of each element and presents the implications of the findings for both qualitative variation and broader impacts.

4.1 Demographic profile of Erzurum Rosette producers

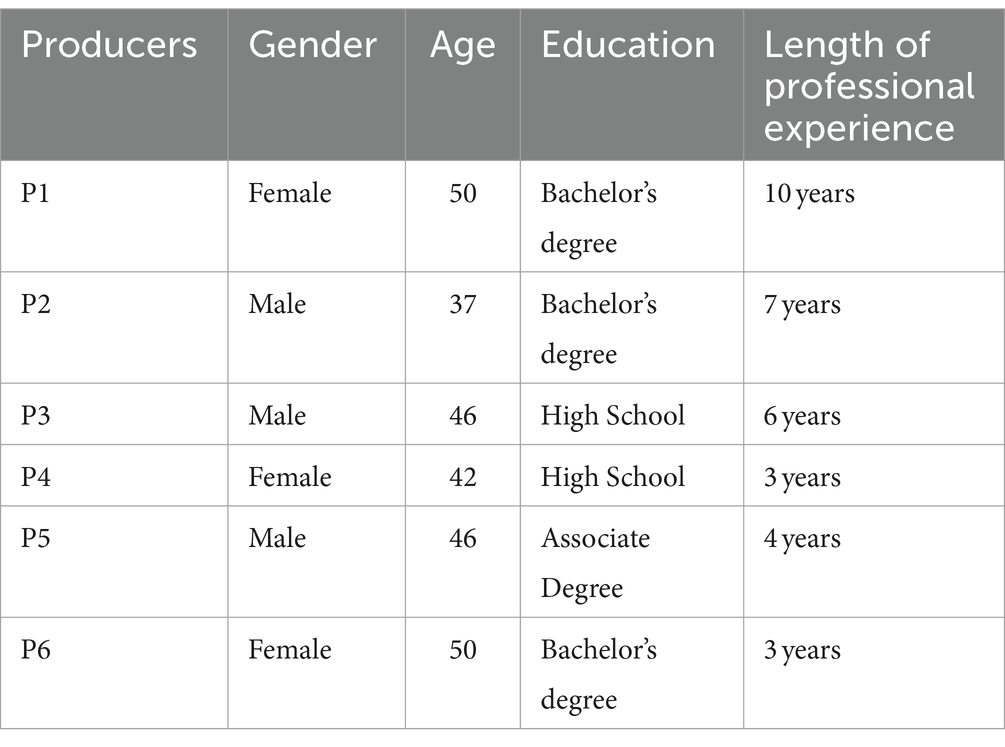

The demographic characteristics of Erzurum Rosette producers provide a context for interpreting qualitative data. Six of the seven producers registered with TPTO agreed to participate in the interviews. The producers’ demographic details are presented in Table 2.

Demographic analysis of the six producers participating in the study showed a balanced representation in terms of gender. There is an equal distribution of male and female producers, indicating that Erzurum Rosette production is not dominated by one gender and is an accessible craft for both men and women. The age of the producers varied between 37 and 50 years, with an average age of 45. This relatively mature age group suggests that producers have considerable life and work experience, which may be necessary for maintaining the quality and tradition of Erzurum Rosette production. The standard deviation of age was approximately 5.4 years, indicating moderate age variability within the group.

Regarding educational attainment, half of the farmers (50%) had a bachelor’s degree, 33.3% had a high school diploma, and 16.7% had an associate’s degree. The diversity of these educational backgrounds underscores that post-secondary formal education is relatively common among these producers, which may influence their approaches to production practices and farm management. The high percentage of producers with a bachelor’s degree suggests that a significant proportion of producers can use advanced knowledge and skills in their craft. Producers’ work experience ranged from 3 to 10 years, averaging 5.5 years. This range reflects the mix of experienced and relatively new producers. The standard deviation of work experience is about 2.7 years, indicating moderate variability in the experience of producers. The presence of experienced and new producers can contribute to the dynamic exchange of traditional knowledge and innovative practices within the community.

4.2 The relationship between production experience and the source of learning

The production of Erzurum Rosette, a traditional and culturally significant dessert, relies heavily on transmitting knowledge and skills across generations. Understanding the duration of the production experience and the sources from which producers learn these skills provides critical conclusions about the sustainability and conservation of this culinary heritage. This chapter examines the relationship between the length of time Erzurum Rosette producers have been making this dessert and their sources of learning and highlights the role of intra-family transmission in maintaining traditional production practices. By analyzing the average production duration based on different sources of learning, such as grandmothers, elders, and mothers, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of how traditional knowledge is transmitted and preserved within families. This analysis not only highlights the importance of family relationships in maintaining cultural practices but also reveals differences like knowledge transfer within the family context.

Figure 2 shows the average production time of Erzurum Rosette producers according to their learning source (grandmothers, elders, and mothers). This analysis reveals clear patterns in production time based on learning sources and provides valuable insights into how traditional culinary knowledge is transmitted and preserved within families. The data showed that producers who learned from their grandmothers, such as P1 and P4, had an average production time of 6.5 years. This finding suggests that grandmothers are essential in transmitting sustainable production techniques and knowledge. The skills transfer from grandmothers appears strong enough to maintain traditional practices for a significant period. The knowledge passed on by grandmothers is likely to include not only the technical aspects of production but also the cultural and historical significance of Rosette, contributing to a broader and more enduring transmission of practices.

Figure 2. Matrix coding query: cross tabulation between the mean duration of Erzurum Rosette production time by learning source.

Similarly, producer P2, who learned from his grandparents, had a significant average production time of 6.5 years. This finding emphasizes that family elders contribute significantly to the continuity of production practices, possibly involving a more comprehensive range of relatives than parents or grandparents. The learning environment provided by multiple elders can strengthen and stabilize the transmission of traditional skills by drawing in a broader pool of experiences and knowledge. The role of elders in teaching the production of Erzurum Rosette can include joint family activities, shared stories, and common cooking stages, and these collective activities can help to embed the practices deeply into the family tradition.

On the other hand, P3, P5, and P6 had an average production time of 4 years with skills learned from their mothers. Although still significant, this period is slightly shorter than those learned from grandmothers or elders. This may indicate that the transmission of knowledge from mothers, while important, may be influenced by contemporary practices or constrained by limited family context. The slightly shorter duration associated with learning from mothers may reflect a more practical approach to knowledge transfer, focusing on everyday cooking needs and less on ceremonial elements that grandmothers or elders may emphasize. Additionally, as mothers balance multiple responsibilities, the depth and frequency of teaching interactions may be affected.

The consistent average duration of 6.5 years for grandmothers and grand families indicates a strong cultural and traditional base within these sources of learning. Grandmothers and elders, as custodians of culinary heritage, provide a more comprehensive and perhaps more ritualized learning experience. Their teachings ensure that the practices are not only followed but also appreciated for their historical and cultural significance. In contrast, the slightly shorter duration of learning from mothers suggests a different dynamic emphasizing the practical aspects of cooking.

Overall, this qualitative analysis highlights the critical role of family resources in preserving and maintaining the Erzurum Rosette production. The data suggest that traditional knowledge, especially that grandmothers and family elders passed on, is preserved over extended periods. This finding emphasizes the importance of family relationships in maintaining cultural practices. The differences between learning sources highlight how different family dynamics contribute to the rich tapestry of culinary heritage, ensuring that traditional methods are preserved and adapted across generations. This deep familial transmission is essential for maintaining cultural integrity and continuity of traditional foods such as Erzurum Rosette.

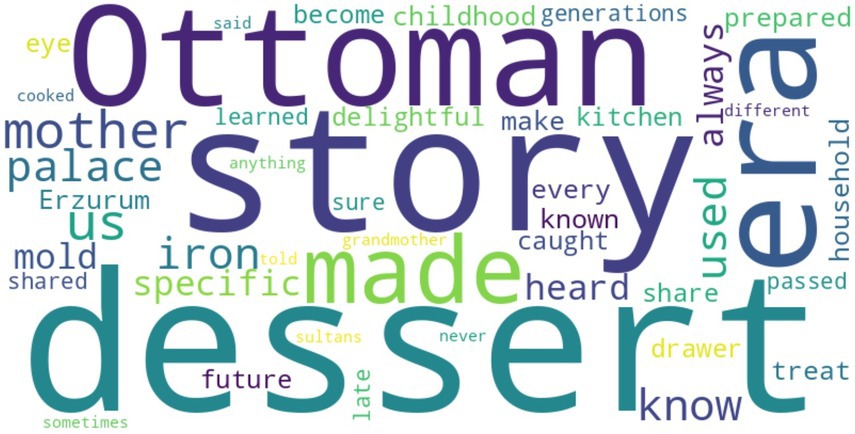

4.3 Analysis of the historical and cultural significance of the rosette

Erzurum Rosette is not only a feast of taste but also a symbol of cultural heritage deeply rooted in the traditions of Erzurum. Understanding this dessert’s historical and cultural significance provides valuable insights into its role in society and contribution to the region’s identity. This chapter aims to capture and present the cultural importance of Erzurum Rosette through rich historical stories told by its producers. By delving deeper into the narratives shared by these custodians of tradition, it may be possible to uncover the layers of meaning that the authentic dessert carries from its origins to its evolution and place in contemporary society. Using advanced qualitative analysis techniques, such as text search queries to identify key narratives, word frequency queries to highlight dominant themes, and word clouds to transform these narratives into coherent themes (Fu et al., 2023), which illuminates the cultural fabric woven around Erzurum Rosette (Figure 3). This exploration aims to understand how local traditional desserts reinforce cultural expression, continuity, and community ties.

Figure 3. NVivo software-based word cloud mapping for historical and cultural narratives of the Erzurum Rosette.

The word cloud map created from the historical and cultural narratives of Erzurum Rosette provides a rich visual representation of the most frequently mentioned terms and themes. Prominent words in the word cloud, such as “Ottoman,” “history,” “dessert,” “one,” “at the time,” and “made,” highlight key elements of the historical and cultural significance of the dessert. The word “Ottoman” is particularly prominent and suggests that Erzurum Rosette is strongly associated with the Ottoman period. This frequently mentioned word emphasizes the importance that producers attach to the historical roots of the dessert and the prestige it once enjoyed as part of Ottoman palace cuisine (Samancı, 2008; Öğretmenoğlu et al., 2023). The repetition of the words “palace” and “sultan” further reinforces this connection, suggesting that the cultural narrative of the Erzurum Rosette is deeply intertwined with Ottoman palace cuisine and its historical legacy.

The prominence of words such as “story” and its derivatives “history” and “know” reflects the importance of storytelling in preserving and transmitting the history of Erzurum Rosette. These words indicate that producers frequently refer to stories associated with desserts and emphasize the role of oral history in maintaining cultural traditions. The presence of words such as “to us,” “my mother,” and “from her mother” emphasizes the family transmission of these stories and practices and shows how the knowledge of making Erzurum Rosette has been passed down through generations.

Words such as “dessert,” “made,” and “at that time” indicate the practical aspects and historical context of the production of the dessert. The frequent use of these terms suggests that narratives often include details of how desserts are traditionally made and evolved (Tebben, 2015). This provides a comprehensive overview of the production techniques and the historical timeline of Erzurum Rosette.

The word cloud also reveals the importance of home and family in the cultural narrative through terms such as “at home,” “from the kitchen,” and “in our childhood.” These words emphasize that Erzurum Rosette is not only a dessert of cultural heritage and importance in Ottoman palace cuisine but also a cherished family tradition. Frequent references to home environments and childhood memories emphasize producers’ personal and intimate connection with the dessert, which further enriches its cultural significance.

In conclusion, the word cloud map provides a detailed qualitative account of the historical and cultural narratives of the Erzurum Rosette. The prominence of words related to the Ottoman period, storytelling, familial transmission, and domestic settings emphasizes the multifaceted cultural significance of the dessert. Erzurum Rosette symbolizes the cultural heritage and a cherished family tradition maintained through oral history and personal ties across generations. This dual significance increases the artistic value of Erzurum Rosette and makes it a permanent and meaningful part of local gastronomic heritage.

4.4 Analysis of Rosette’s traditional production process and materials

Understanding the traditional production process of Erzurum Rosette and its ingredients is crucial for documenting and preserving this cultural heritage. This chapter aims to meticulously record the producers’ traditional methods and ingredients and provide a comprehensive overview of how this precious dessert is made. By using thematic coding to categorize detailed steps and ingredients and hierarchical coding to organize these codes in a sequential structure, it is possible to accurately convey the traditional production process (Buckley, 2022). In addition, model building using NVivo (Alyahmadi and Abri, 2013) can visualize the production process to provide a clearer understanding of the comparison between traditional practices and the official GI registration process. This detailed documentation will not only help preserve the authenticity of Erzurum Rosette but also highlight any deviations or adaptations that may have occurred over time, thus contributing to preserving the cultural and historical integrity of the dessert.

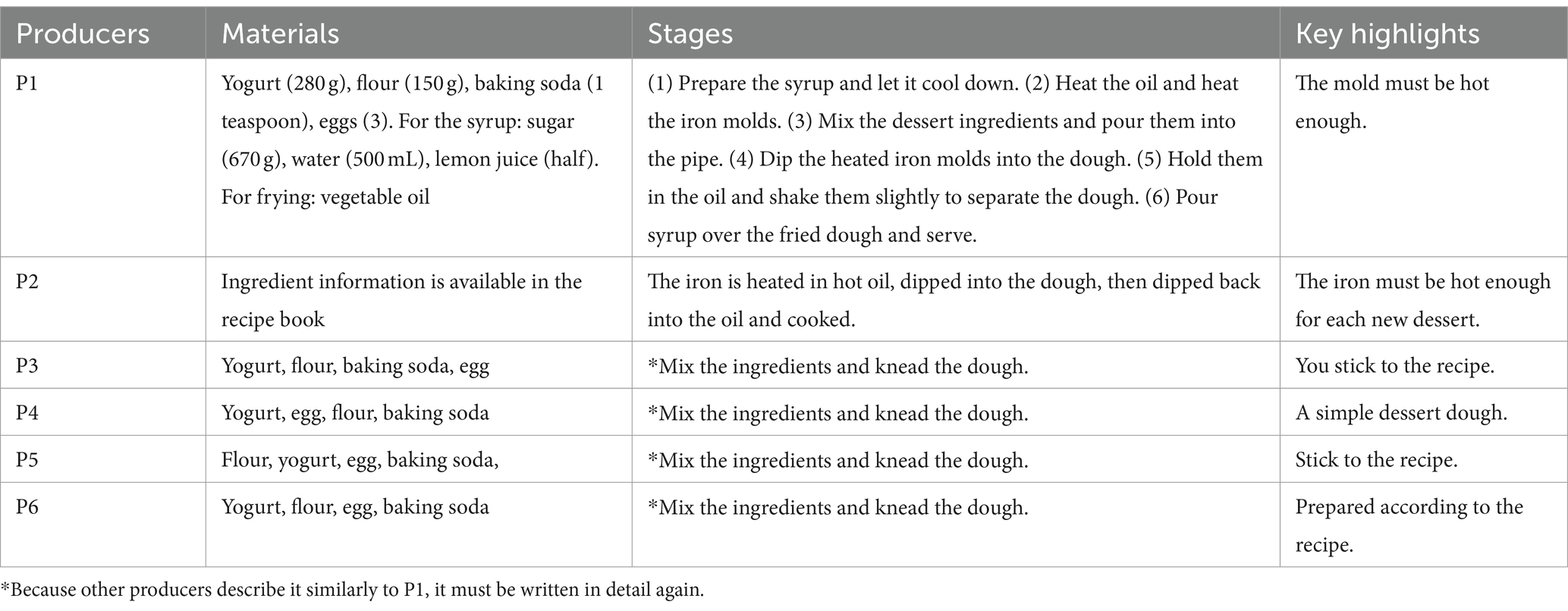

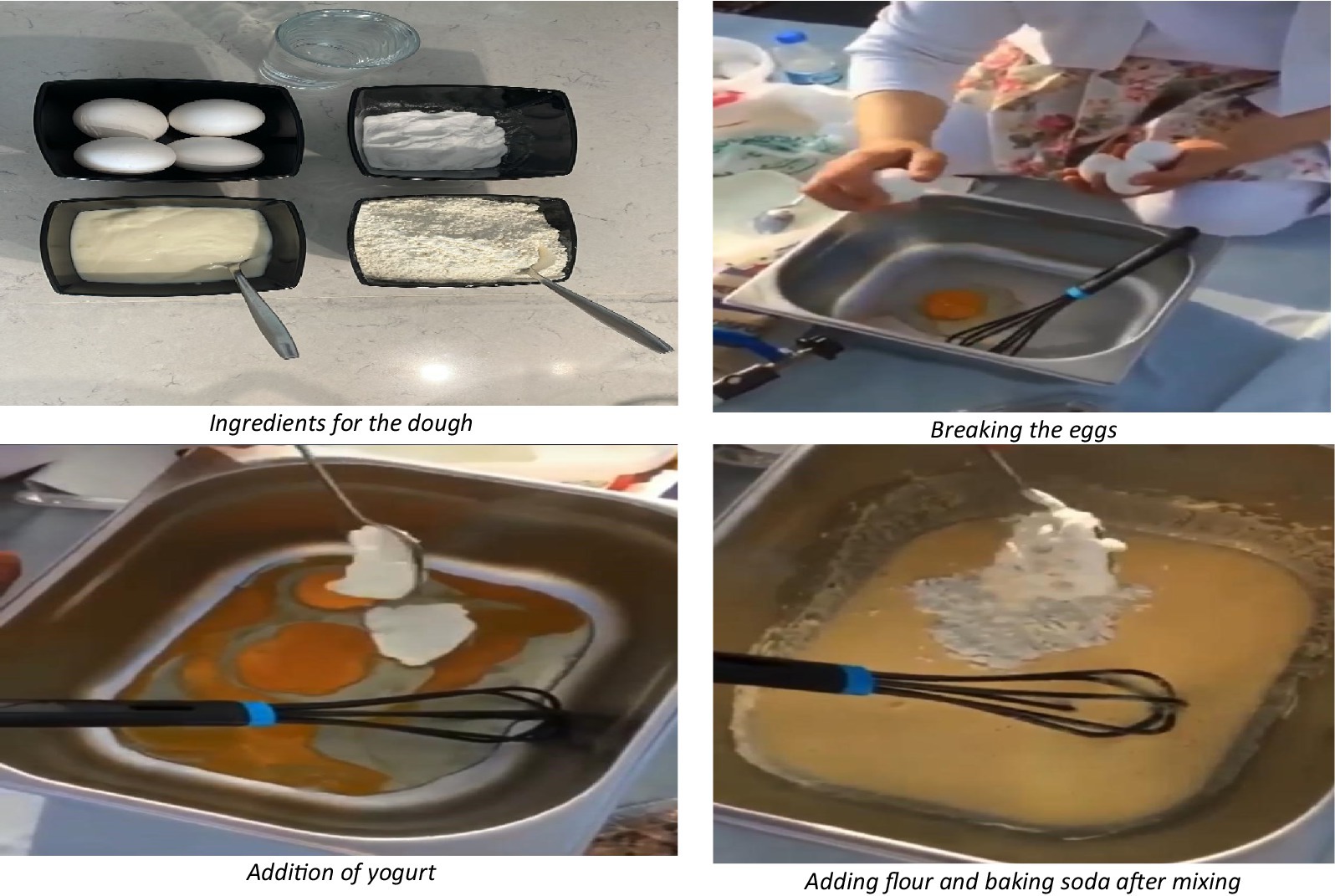

The traditional production process and ingredients of Erzurum Rosette are meticulously detailed by producers, and great importance is attached to following the traditional recipe and its critical steps. Because the other producers, such as P1, repeated the steps, they need to be rewritten in detail in Table 3. Thematic coding reveals common ingredients, such as yogurt, flour, salt, baking soda, and eggs, that all producers consistently mention. Hierarchical coding organizes these components and steps in a structured order, highlighting the importance of each step in the production process. Figure 4 also shows visualizations of the stages of traditional production.

The most crucial finding in this section is identifying two significant material differences between the recipe in the TPTO records and producers’ transmissions. While the recipe in the TPTO records included milk and baking powder in the list of ingredients, the producers should have mentioned these two products. The ingredients used by the producers were yogurt and baking powder. The institution (Erzurum Commodity Exchange) that owns the GI registration should review this situation immediately. This error should be corrected as soon as possible.

Among the important results obtained from the responses, the critical role of the temperature of the iron mold in reaching a sufficient temperature to form the dough correctly was mentioned. More than one producer emphasized this detail and demonstrated the technical skills and mastery required in Erzurum Rosette production. Figure 5 illustrates this practice.

Figure 5 also shows a consistent mention of specific ingredients and the process of making sherbet (sorbet) before preparing the dough, indicating a standardized approach to preserving the traditional taste and texture of the dessert. While the comparison between the traditional practices and the official GI registration document shows that the cooking steps are followed consistently, the discrepancy between the ingredients used in production, specifically milk and yogurt and baking powder and baking soda, should be addressed. This may be due to typographical errors in the application or individual mistakes in the registration process.

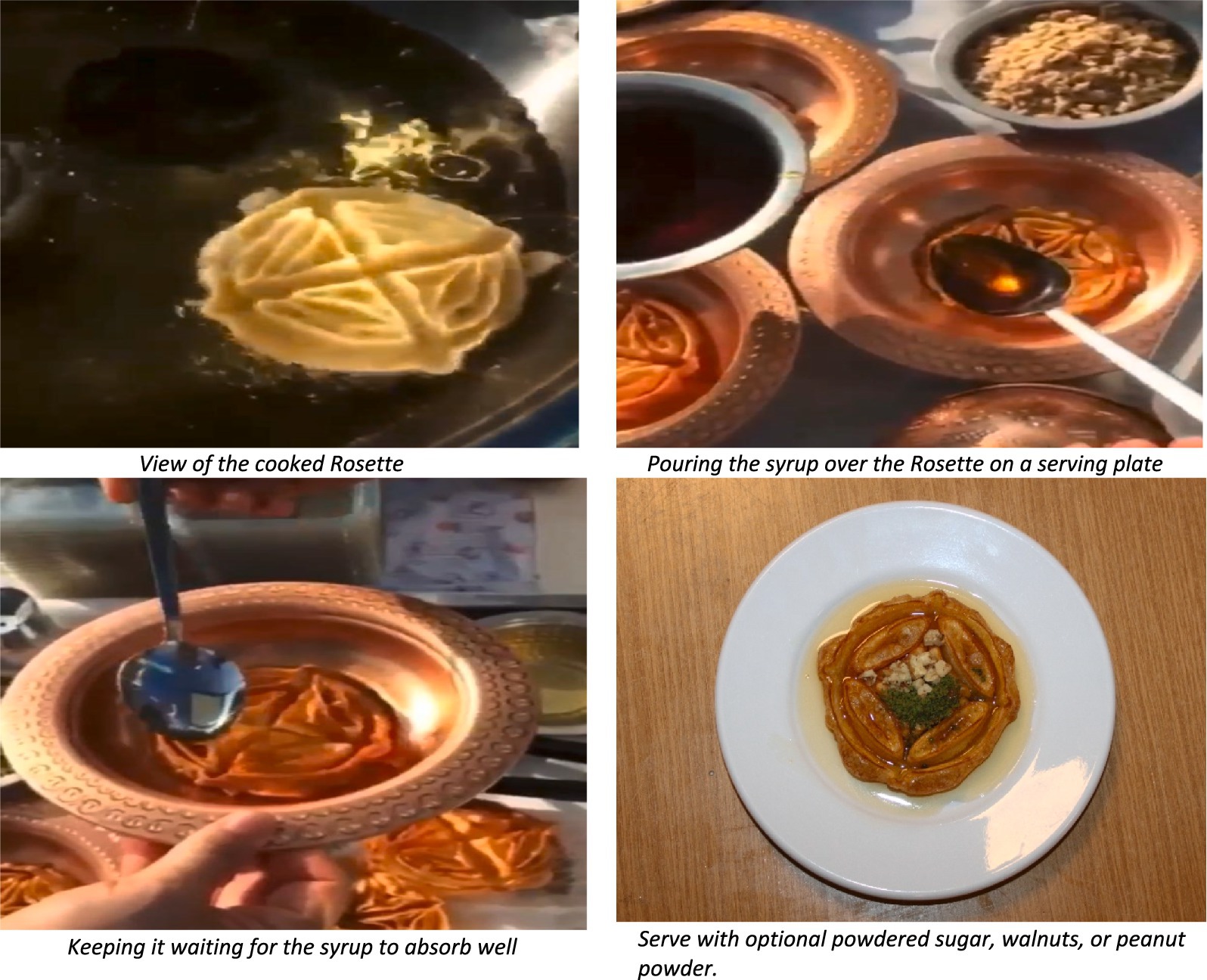

After the cooking stage, serving Erzurum Rosette is essential and should be considered as a whole with cultural heritage. Figure 6 shows different presentation and serving methods.

Figure 6 shows not only the syrup obtained by mixing granulated sugar and lemon juice with water and boiling it but also the syrup served on the warm iron desserts. Desserts were sprinkled with powdered sugar, walnuts, or pistachios. This analysis highlights the balance between adhering to tradition and allowing individual craftsmanship in Erzurum Rosette production. By visualizing these steps, the photographs provide a clear and detailed representation of the production process and serving, essential for preserving the authenticity and cultural heritage of the desert.

4.5 Producers’ understanding of the GI and its impact on sales

Understanding the concept and implications of Geographical Indication (GI) is essential for producers of traditional products such as Erzurum Rosette. This chapter aims to assess producers’ knowledge and understanding of GI and examine GI registration’s impact on production and sales. By combining these two perspectives, this study aimed to obtain a comprehensive perspective on the impact of recognizing the concept of GI on producers’ awareness and working life activities (Doğan, 2024). First, it aims to measure producers’ awareness of and attitudes toward this certification by taking an in-depth look at their understanding of the concept of GI (Lee and Zhao, 2023). Through text search queries and sentiment analysis, GI responses were extracted, analyzed, and categorized based on knowledge levels and attitudes (Chen, 2021). This approach helps to understand knowledge levels of manufacturers’ perceptions and possible misconceptions about GI.

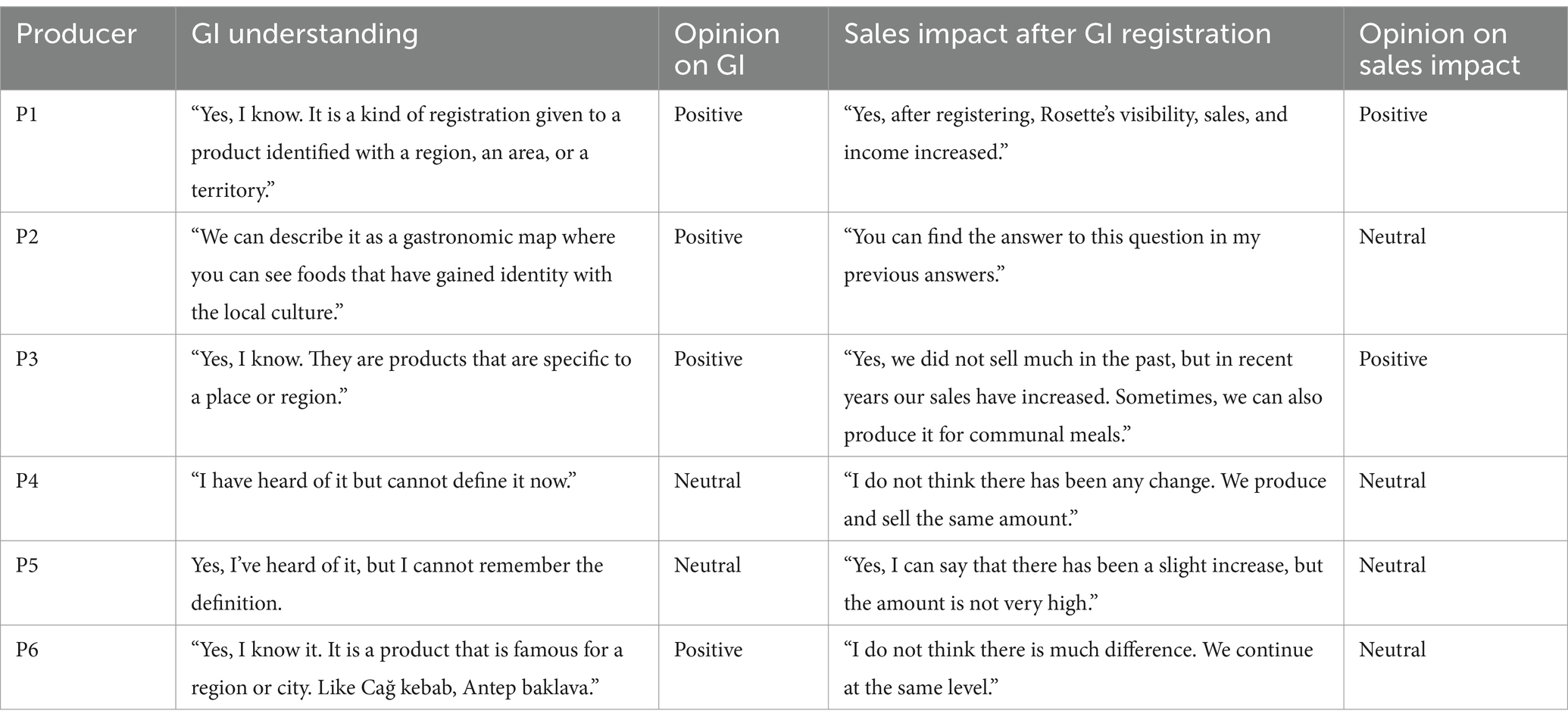

Next, the impact on sales and marketing strategies following the registration of a GI was assessed by comparing sales data before and after the registration of the GI and coding producers’ responses to changes in sales; a before and after analysis was conducted to identify significant trends. In addition, matrix coding queries were used to explore the relationship between GI registration and changes in sales and marketing approaches, providing an adequate understanding of the practical benefits to producers in recognizing the GI concept. The combination of these analyses aims to provide a holistic view of the role of GI practices in increasing producers’ knowledge and improving their market performance. It also highlights the importance of such certification in preserving cultural heritage and enhancing economic sustainability (Table 4).

Table 4. A joint analysis of producers’ understanding of GI and the impact of GI registration on sales.

Producers’ understanding of the GI concept and the impact of GI registration on sales offer important conclusions about their level of knowledge and the practical implications for their work.

Most producers have a clear and positive understanding of the GI concept. P1, P3, and P6 provide precise definitions and associate the GI with specific products that are identified with a region or locality, such as Oltu Cağ Kebab (Üzümcü and Denk, 2019) or Antep Baklava (Erdoğan and Özkanlı, 2021). P2, on the other hand, defines the concept of GI from a broader cultural perspective as part of a gastronomic map that highlights regionally important foods. This detailed understanding is reflected in their positive attitude toward GIs and shows an appreciation for the recognition and protection they provide to their traditional products.

In contrast, P4 and P5 partially or vaguely understand the GI concept. While P4 admits that he has heard of the concept of GI but cannot define it, P5 states that he knows it but cannot recall its definition. Their neutral attitudes toward the concept of GI indicate that they do not have strong emotions and do not have a positive or negative orientation due to their incomplete understanding.

The assessment of the impact on sales after the registration of a GI varies among the producers. P1 and P3 report a positive effect, indicating increased awareness and sales after GI registration. P1 emphasizes that awareness and sales of the Erzurum Rosette have increased, resulting in higher income. P3 states that there has been a significant increase in sales, and orders for collective events have also increased, indicating a broader market reach since the registration of the GI.

In contrast, P4, P5, and P6 state that they have seen little or no impact on their sales. P4 states that production and sales volumes have remained the same since the registration of the GI and that they have continued at previous levels. P5 states that there has been a slight increase in sales, but this increase is not significant. P6 states that there is no significant difference in sales and that they continue at the same level.

The feelings about the impact on sales are also consistent with these experiences. While P1 and P3 show positive sentiments, reflecting that they have observed the benefits of GI registration, the neutral sentiments of P2, P4, P5, and P6 show uncertainty or indifference due to minimal changes in sales.

Statistically, three-quarters of the six producers (66.7%) indicate a good understanding of GI and exhibit positive emotions, while the remaining two producers (33.3%) have a neutral knowledge and attitude. Regarding sales impact, only two producers (33.3%) report a positive change in their sales, while the majority (66.7%) report a neutral or minimal effect.

This analysis highlights the critical role of thorough understanding and effective use in realizing the potential benefits of GI certification. Producers with a better understanding and positive attitude toward GI practices are likelier to experience and accept its positive impact on sales and recognition. In contrast, those with less understanding observe minimal changes as they need help to realize the benefits fully. Therefore, increasing producers’ knowledge and strategic use of GI could increase its positive impact on traditional products.

4.6 Rosette production challenges and sustainability issues

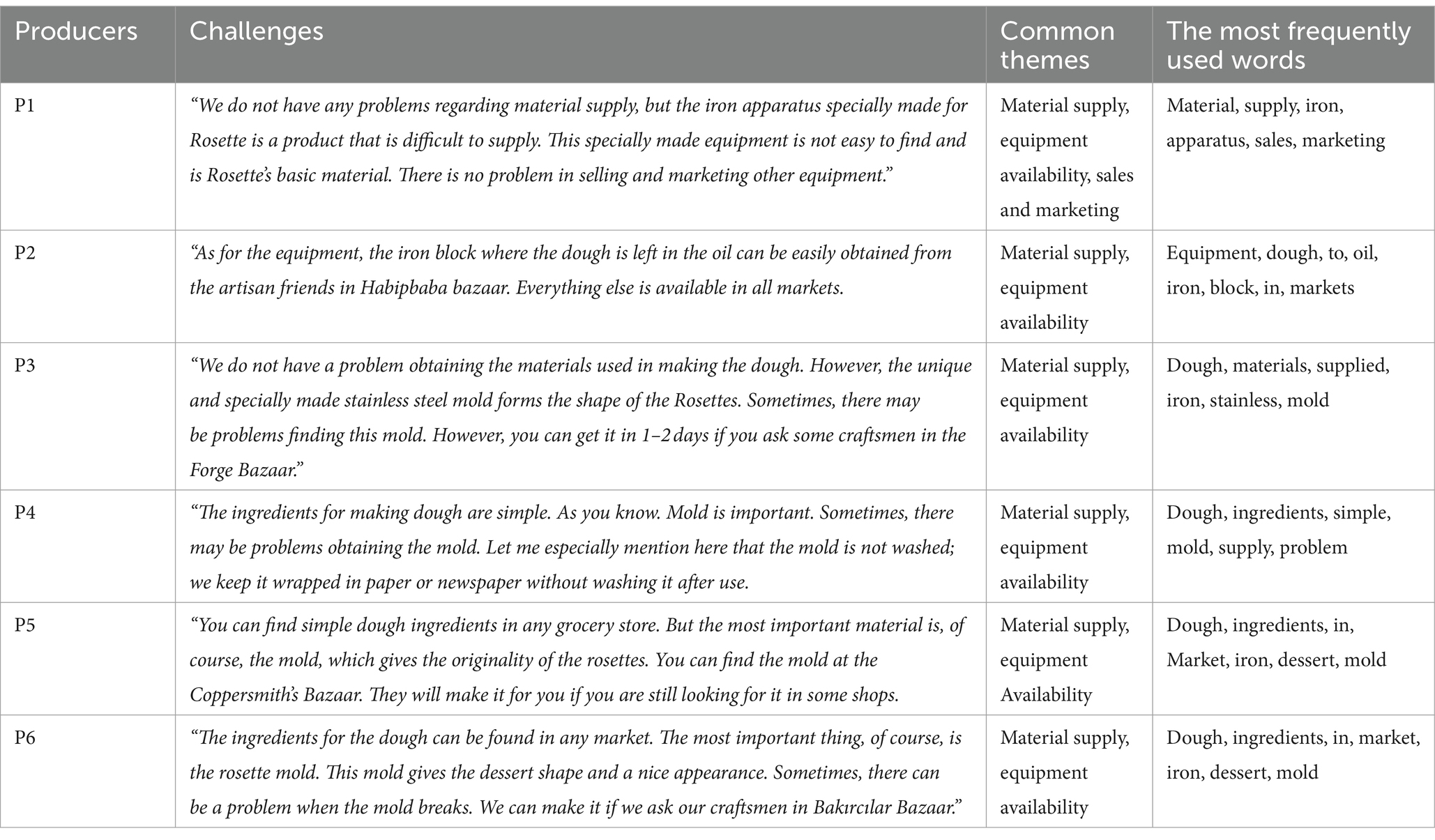

Although the Erzurum Rosette production is deeply rooted in tradition, it faces several challenges that may affect its sustainability. Identifying and addressing these challenges is essential to preserve the local cultural heritage and sustain its success. This section aims to uncover the production challenges and sustainability issues experienced by producers (de Castro Moura Duarte and Picanço Rodrigues, 2024). A comprehensive understanding of the barriers can be obtained by using thematic analysis to code and categorize these challenges and applying word frequency queries to highlight the most frequently mentioned issues (Naeem et al., 2023). Furthermore, by cross-tabulating these challenges with producer demographics and production experience using matrix coding queries, these challenges can provide more in-depth insights into how different factors influence the challenges faced. Through this detailed examination, common challenges are discussed, and potential solutions are proposed to increase the sustainability of Erzurum Rosette production so that this beloved dessert will live on for generations to come (Table 5).

The most common challenge identified by all producers relates to the procurement of materials and the availability of necessary equipment, especially the procurement of special iron molds required to produce Erzurum Rosettes. Producers P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, and P6 stated that while the general ingredients for the dough (such as flour, yogurt, and eggs) are readily available in local markets, special iron molds are a significant barrier. These molds are critical to giving Erzurum Rosette its distinctive shape and texture, and their rarity or difficulty in obtaining them can disrupt production.

P1 emphasizes that iron molds are custom-made, not widely available, and an essential component in the production of Erzurum Rosette. The producer notes that although other materials are readily available, molds often have to be specially ordered, which can delay production. Similarly, P3 and P6 state that these molds are unique and sometimes hard to find, but local artisans can make them on demand.

P2 and P4 state that these molds can be obtained from specific local markets or shops such as Habipbaba and Bakırcılar bazaars. However, P4 adds that there can be occasional problems in obtaining these molds, especially when molds need to be custom-made or when existing molds are broken and must be replaced.

While the primary challenges revolve around material supply and equipment, P1 mentions sales and marketing. This manufacturer states that these areas are delicate and that there is stability and effectiveness in the current sales and marketing strategies. The lack of significant obstacles in marketing and selling Erzurum Rosette may be related to the producer’s well-established customer base or effective promotional strategy. Thematic analysis and word frequency queries highlight the producers’ recurring themes and terminologies. Terms such as “material,” “mold,” and “iron” are frequently repeated, highlighting the central role of these components in the production process. Supply-related words such as “procure” and “supply” also appear often, reflecting the ongoing concern about obtaining necessary materials and equipment.

5 Discussion

Demographic analysis indicates that Erzurum Rosette production is not gender-specific and is accessible to both men and women. This inclusivity suggests that the craft is equally attractive and practical for both genders, which may increase its sustainability and wider acceptance (Yang et al., 2018).

The advanced age and considerable professional experience of the producers indicate that experience is a crucial factor in maintaining the quality and tradition of the Rosette (Petrescu et al., 2020). The average age of 45 years indicates that the producers likely possess a wealth of life and professional experiences, which contribute to their expertise in Rosette production. This level of maturity is often associated with a deeper understanding and appreciation of traditional methods and the capacity to innovate within these traditions (Lees et al., 2020). The standard deviation of age, 5.4 years, indicates a moderate level of variability within the group, suggesting a healthy mix of perspectives and approaches within the producer community.

The diversity of educational backgrounds among producers can result in disparate approaches to production and business management. This can facilitate the introduction of innovative practices while maintaining traditional methods (Uçuk, 2023). Those with higher levels of education, such as a bachelor’s degree, are able to incorporate advanced knowledge and skills into their craft, which may include modern business practices, marketing strategies, and quality control techniques (Autio, 2015). This diversity of educational background can be advantageous in that it allows for the blending of traditional expertise and modern innovations, thereby ensuring the relevance of the craft in contemporary markets. Furthermore, the diverse range of training levels demonstrates a comprehensive spectrum of intellectual engagement with the craft, encompassing both practical, hands-on techniques and theoretical and analytical approaches (Crawford et al., 2018).

The transmission of knowledge from grandmothers and elders is associated with longer production times than that from mothers, indicating that the transfer of knowledge from these sources is more enduring (Mera-Shiguango et al., 2022). This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that grandmothers and elders play a pivotal role in the preservation of cultural heritage (Choe and Park, 2009; Jongenelis et al., 2019; MacDonald et al., 2020; Oğan and Çelik, 2023). Grandmothers and elders frequently serve as custodians of family traditions and are more deeply immersed in the historical and cultural contexts of these practices (Zort et al., 2023). Their teachings encompass both technical skills and cultural narratives and values related to the production of rosette, resulting in a more comprehensive and enduring transmission of knowledge.

The meticulous elaboration of the traditional production process and the deliberate emphasis on specific ingredients and techniques underscore the technical expertise and precision required to preserve the authentic essence of the dessert (Balderas-Cejudo et al., 2020). The meticulous adherence to traditional recipes and the exact execution of the production steps guarantee that the final product remains faithful to its historical origins. This technical rigor is vital to preserve the Rosette’s distinctive characteristics, including its flavor, texture and appearance, which are essential for the cultural and gastronomic identity of the dessert. Furthermore, it is a crucial factor in maintaining the standards set forth by the GI registration (Belletti et al., 2015).

Comparing these findings with other studies, it is clear that the strong cultural and traditional base within learning resources contributes significantly to the longevity of production practices (Britwum and Demont, 2022). For example, one study found that traditional culinary practices have longer sustainability when elders pass on knowledge (Suleiman et al., 2023). This finding is because older family members often have a wealth of experience, a strong interest in preserving cultural heritage, and a memory (Dalla Porta et al., 2018), which ensures accurate and comprehensive transmission of practices. The study findings support this and emphasize the critical role of familial resources in the preservation and sustainability of Erzurum Rosette production. The involvement of grandmothers and elders in teaching younger generations ensures the effective transmission of cultural and technical knowledge required for Erzurum Rosette production, securing the future of the dessert.

Overall, this study’s demographic and experiential factors highlight the importance of inclusiveness, maturity, educational diversity, and intergenerational knowledge transfer in Erzurum Rosette production. Together, these elements contribute to the sustainability and cultural preservation of traditional and authentic desserts.

5.1 Producers’ understanding of GI and the impact of GI registration on sales

This study addresses a significant gap in the existing literature on the impact of Geographical Indication (GI) registration on the recognition and sales of traditional products. It focuses specifically on the case of Erzurum Rosette. Geographical indications (GI) are regarded as a valuable instrument for regional development, as they enhance the visibility of regional products in national and international markets, thereby stimulating economic growth in rural areas (Belletti et al., 2015; Cei et al., 2018; Aparecida Cardoso et al., 2022). However, discrepancies in the interpretation of CI among producers may impede the realization of this potential.

The findings indicate a discernible discrepancy in the comprehension of CI among the producers. The majority of producers exhibited a comprehensive and positive understanding of CI, associating it with recognized regional products and recognizing its role in protecting and promoting their traditional products. These producers indicated an increase in sales and expansion of market access following the registration of CI. This finding is consistent with the existing literature, which has identified the positive impacts of CI registration on economic and cultural sustainability (Aparecida Cardoso et al., 2022).

In contrast, some manufacturers show only a partial or vague understanding of GI, associated with neutral sentiments and a minimal impact on sales (Thangaraja, 2018). In contrast, some manufacturers show only a partial or vague understanding of GI, associated with neutral sentiments and a minimal impact on sales (Thangaraja, 2018). This group accepts the GI system but needs a precise definition or a complete understanding of its benefits. This uncertainty leads to the potential of GI practices needing to be fully realized, resulting in minimal positive impact. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that limited knowledge and awareness can hinder the effective use of the GI system, thereby reducing its positive impacts (Basole, 2015).

In terms of the management and implementation of GI, it is evident that producers would benefit from further training and awareness programs. Effective management of CI encompasses not only the registration process but also the positioning of the product in the market and the management of competition (Kalekahyası and Göktaş, 2022). In the context of regional development, it is imperative that local governments and producers collaborate more closely to ensure that GI makes the greatest possible contribution to regional economies (González et al., 2020).

Comparing these findings with other studies, it is clear that a strong cultural and traditional base, coupled with extensive knowledge of GI, contributes significantly to positive impacts on sales and recognition. For example, many studies have found that traditional culinary practices last longer and achieve greater market success when they are deeply understood and well-grasped by producers (Horng and Tsai, 2012; Guiné et al., 2021). The study results support this by highlighting that the effective use of GI practices depends on producers’ knowledge and strategic approach.

5.2 Key challenges and sustainability issues identified by manufacturers

The most significant challenge identified across all manufacturers was the difficulty in obtaining the specialized iron molds required to impart Rosetta’s distinctive shape and texture. This underscores the necessity of safeguarding the specialized instruments utilized in conventional production methodologies (Tehrani and Riede, 2008; Jones and Yarrow, 2013). While the general ingredients required for dough, such as flour, yogurt, and eggs, are widely available, the scarcity of these specialized molds represents a significant challenge. This finding is consistent with the existing literature that identifies supply chain constraints as a significant challenge to the sustainability of traditional crafts (Ghadge et al., 2021).

Producers identified local markets, such as Habipbaba and Bakırcılar bazaars, as potential sources for these patterns, but emphasized that availability cannot be guaranteed. This highlights the necessity to safeguard the equipment employed in the manufacture of traditional products and to guarantee the sustainability of supply chains (Ghadge et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023). The pivotal function of iron molds in the production process is of paramount importance in maintaining the authenticity and regional identity of this craft (Jones and Yarrow, 2013).

Although material supply and equipment availability are the main challenges, the study reveals that sales and marketing are minor issues for some manufacturers. This is in contrast to other studies where marketing is often highlighted as a significant challenge for traditional food producers (Meissner, 1976; Aggestam et al., 2017). The stability in sales and marketing observed for some producers may be due to their well-established customer base and effective promotional strategies. However, it is important for producers to continually innovate their marketing approach to expand their market reach and increase product visibility.

The results of this study highlight the need for improved local production support and distribution networks to address supply chain issues related to custom iron molds. Increasing the production and availability of these molds by local artisans can significantly alleviate the challenges Erzurum Rosette producers face. In addition, continued efforts to promote this traditional dessert through effective marketing strategies can further enhance its market presence and sustainability.

Compared to other studies, these findings suggest that practical challenges, such as sourcing materials and equipment, are common across various traditional crafts (Gokee and Logan, 2014; Lin and Lin, 2022). However, the focus on iron molds specific to the Erzurum Rosette highlights a unique aspect of this particular craft. Furthermore, the study contributes to a broader understanding of the practical challenges of traditional food production and suggests targeted support strategies for producers.

The aforementioned challenges confronting producers can be effectively addressed through the implementation of efficacious management strategies pertaining to CI, coupled with the enactment of conducive policies. It is imperative that local governments and organizations within the sector provide enhanced support to address the aforementioned supply chain issues (Lin and Lin, 2022). This will enhance the sustainability of Rosetta’s production and also facilitate regional development.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

This study aims to increase the awareness of Erzurum Rosette, which is widely produced and consumed at home in Erzurum, to determine whether the production process is by the registration certificate in the records of the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office, to contribute to its sustainability, and to identify the barriers, if any, to its production. The results show that male and female producers carry out Erzurum Rosette production and benefit from significant life and work experience. However, challenges remain in obtaining the special iron molds needed to preserve this special dessert’s distinctive quality and traditional methods. There are also differences in producers’ understanding of the GI, with producers with extensive knowledge of the GI reporting more significant benefits in sales and market access. To promote the sustainability of the Erzurum Rosette and realize its potential as a tourism product, these supply chain issues need to be addressed, and it is important to increase producers’ knowledge of the benefits of the GI. By improving local production support and providing targeted educational initiatives, the traditional production of this special dessert can be better preserved, promoted, and developed as a cultural heritage and important gastronomic asset of Erzurum.

In addition, when the production materials provided by the producers were compared with the TPTO records, it was found that there was a difference between them. This situation contrasts with GI practices. Mistakes may have been made in the human factor application or registration stages. The registrant institution (Erzurum Commodity Exchange) should quickly resolve this issue and update TPTO records. The study’s findings should be considered as a reference at this stage.

Despite the valuable results provided by this study, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the study was conducted with six of the seven registered producers in the TPTO records. The sample size of these six producers is relatively small and may limit the generalizability of the findings. The small sample size limits the ability to fully reflect the diversity of experiences and practices of all Erzurum Rosette producers in Erzurum. As a result, the findings may not fully represent the wider producer population, and additional research with larger sample sizes is required to confirm these findings and increase their applicability.

Another limitation is the potential bias in the data provided by the producers themselves, which can affect the accuracy of the results. The producers’ understanding of GIs and their responses regarding the impact of GI registration on sales are subjective and can be influenced by individual perceptions and experiences. This subjectivity introduces uncertainty into the data and can make it challenging to understand the actual effects of GI registration and the specific difficulties producers face. Future studies could benefit from including objective measures, such as sales data and market analyses, to verify self-reported information.

The study also highlights significant challenges related to the availability of materials and equipment, such as the special iron molds required for Erzurum Rosette production. However, it must explore potential solutions, like local production support or improved distribution networks. This omission limits the practical applications of the findings, as addressing these challenges is crucial for the sustainability of Erzurum Rosette production. Future research should investigate the feasibility and impact of proposed solutions to offer actionable recommendations for producers and policymakers.

Additionally, while the study emphasizes the positive and negative effects of GI registration, it does not account for external factors like market trends, consumer preferences, and economic conditions that could influence sales and market access independently of GI registration. By not considering these variables, the study’s conclusions about the effectiveness of GI registration might be overstated or understated. Future research should aim to control for these external factors to gain a more detailed understanding of the impact of GI registration.

Lastly, the study primarily focuses on producers’ perspectives, excluding the views of other stakeholders such as consumers, local government officials, and industry experts. Including these perspectives could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with Erzurum Rosette production and GI registration. Engaging a broader range of stakeholders would enrich the analysis and help develop more holistic and effective strategies for promoting and sustaining this traditional delicacy.

In conclusion, this study provides significant insights into the production of Erzurum Rosette and the challenges faced. However, limitations related to sample size, data subjectivity, unexamined external factors, and the exclusion of broader stakeholder perspectives highlight areas for future research. Addressing these limitations will enhance the robustness of the findings and contribute to a deeper understanding of how to support and sustain the traditional production of Erzurum Rosette effectively.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The ethics committee permission required for collecting and using the data obtained in this study was obtained from the Atatürk University Social Sciences and Humanities Ethics Committee, with decision number 91 in the 7th session held on 18.03.2024.

Author contributions

ED: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Aggestam, V., Fleiß, E., and Posch, A. (2017). Scaling up short food supply chains? A survey study on the drivers behind the intention of food producers. J. Rural. Stud. 51, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.02.003

Akdag, G., Guler, O., Dalgic, A., Benli, S., and Cakici, A. C. (2018). Do tourists’ gastronomic experiences differ within the same geographical region? A comparative study of two Mediterranean destinations: Turkey and Spain. Br. Food J. 120, 158–171. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-01-2017-0017

Alyahmadi, H., and Abri, S. (2013). Using Nvivo for data analysis in qualitative research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Educ. 2, 181–186. doi: 10.12816/0002914

Antón, C., Camarero, C., Laguna, M., and Buhalis, D. (2019). Impacts of authenticity, degree of adaptation and cultural contrast on travellers’ memorable gastronomy experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 28, 743–764. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2019.1564106

Aparecida Cardoso, V., Lourenzani, A., Caldas, M., Bernardo, C., and Bernardo, R. (2022). The benefits and barriers of geographical indications to producers: a review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 37, 707–719. doi: 10.1017/S174217052200031X

Autio, O. (2015). Traditional craft or technology education: development of students’ technical abilities in Finnish comprehensive school. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2, 75–84. doi: 10.21890/ijres.05918

Balderas-Cejudo, A., Patterson, I., and Leeson, G. W. (2020). “Chapter 10 – gastronomic tourism and the senior foodies market” in Gastronomy and food science. ed. C. M. Galanakis (Academic Press is an imprint as of Elsevier), 193–204. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-820057-5.00010-8

Basole, A. (2015). Authenticity, innovation, and the geographical indication in an artisanal industry: the case of the Banarasi sari. J. World Intellect. Prop. 18, 127–149. doi: 10.1111/jwip.12035

Belletti, G., Marescotti, A., Sanz-Cañada, J., and Vakoufaris, H. (2015). Linking protection of geographical indications to the environment: evidence from the European Union olive-oil sector. Land Use Policy 48, 94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.05.003

Björk, P., and Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. (2014). Culinary-gastronomic tourism – a search for local food experiences. Nutr. Food Sci. 44, 294–309. doi: 10.1108/NFS-12-2013-0142

Britwum, K., and Demont, M. (2022). Food security and the cultural heritage missing link. Glob. Food Sec. 35:100660. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100660

Buckley, R. (2022). Ten steps for specifying saturation in qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Med. 309:115217. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115217

Bukharov, I., and Berezka, S. (2018). The role of tourist gastronomy experiences in regional tourism in Russia. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 10, 449–457. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-03-2018-0019

Čaušević, A., and Hrelja, E. (2020). “Importance of cheese production in Livno and Vlašić for gastronomy and tourism development in Bosnia and Herzegovina” in Gastronomy for tourism development. eds. A. Peštek, M. Kukanja, and S. Renko (Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited), 27–42.

Cei, L., Defrancesco, E., and Stefani, G. (2018). From geographical indications to rural development: a review of the economic effects of European Union policy. Sustain. For. 10:3745. doi: 10.3390/su10103745

Chen, N. H. (2021). Geographical indication labelling of food and behavioural intentions. Br. Food J. 123, 4097–4115. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2020-0552

Cherro Osorio, S., Frew, E., Lade, C., and Williams, K. M. (2022). Blending tradition and modernity: gastronomic experiences in high Peruvian cuisine. Tour. Recreat. Res. 47, 332–346. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2021.1940462

Choe, J. S., and Park, H. S. (2009). A case study on storytelling application of native local foods. J. Korean Soc. Food Culture 24, 137–145. doi: 10.7318/KJFC.2009.24.2.137

Crawford, B., Byun, R., Mitchell, E., Thompson, S., Jalaludin, B., and Torvaldsen, S. (2018). Seeking fresh food and supporting local producers: perceptions and motivations of farmers’ market customers. Australian Plan. 55, 28–35. doi: 10.1080/07293682.2018.1499668

Dalla Porta, E. P., Mahmud, I. C., and Terra, N. L. (2018). A Gerontologia e a Gastronomia: Uma experiência com imigrantes árabes. Rev. Kairós Gerontologia 21, 407–418. doi: 10.23925/2176-901X.2018v21i2p407-418

Damayanti, S. L. P., and Bagiastra, I. (2022). Keterlibatan Masyarakat Dalam Pengelolaan Potensi Wisata Budaya Desa Karang Bajo Kecamatan Bayan Kabupaten Lombok Utara. Media Bina Ilmiah. Scientific Dev. Media 17, 491–502. doi: 10.33578/mbi.v17i3.157

Dancausa Millán, M. G., Vázquez, M., de la Torre, M. G., and Hernández Rojas, R. (2021). Analysis of the demand for gastronomic tourism in Andalusia (Spain). PLoS One 16:e0246377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246377

Daşdemir, A., Madenci, A. B., and Pekerşen, Y. (2021). “Erzurum İlinin Gastronomi Turizmi Açısından Potansiyelinin Değerlendirilmesi” in (İçinde) Gastronomide Alternatif Yaklaşımlar. eds. A. Kaya, M. Yılmaz, and S. ve Yetimoğlu (Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Yayınları), 207–219.

Daştan, H., Dudu, N., and Çalmaşur, G. (2016). Kış Turizmi Talebi: Erzurum İli Üzerine Bir Uygulama. Atatürk Üniv. İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi 30, 403–421. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/atauniiibd/issue/29907/322101

de Castro Moura Duarte, A. L., and Picanço Rodrigues, V. (2024). The sustainability challenges of fresh food supply chains: an integrative framework. Environ. Dev. Sustain., 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10668-024-04850-9

Denk, E. (2023). Erzurum Mutfak Kültürünün Sahip Olduğu Zenginliğin Mutfak Turizmi Açısından Farkında Olmak. Uluslararası Turizm Ekonomi ve İşletme Bilimleri Dergisi (IJTEBS). 7, 59–79. Available at: https://www.ijtebs.org/index.php/ijtebs/article/view/571

Di Vita, G., Spina, D., De Cianni, R., Carbone, R., D’Amico, M., and Zanchini, R. (2023). Enhancing the extended value chain of the aromatic plant sector in Italy: a multiple correspondence analysis based on stakeholders’ opinions. Agric. Food Econ. 11:15. doi: 10.1186/s40100-023-00257-8

Doğan, N. (2024). Economic impact of local geographical indication products on farmers: a case of Kelkit sugar (dry) beans. Cogent Food Agric. 10:2325083. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2024.2325083

Du Rand, G. E., Heath, E., and Alberts, N. (2013). “The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: a South African situation analysis” in Wine, food, and tourism marketing (Routledge), 97–112. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315043395-6/role-local-regional-food-destination-marketing-south-african-situation-analysis-gerrie-du-rand-ernie-heath-nic-alberts.

Erdoğan, D., and Özkanlı, O. (2021). Yöresel Yiyecek ve İçeceklerin Çevrimiçi Medya Kanallarındaki Yansımaları ile Oluşan İmaj Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Gaziantep Restoranları Örneği (A Research on the Online Image of Local Products: An Example of Gaziantep Restaurants). J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 9, 1165–1186. doi: 10.21325/jotags.2021.834

Erzurum Rosette Tescil Belgesi. (2021). Available at: https://ci.turkpatent.gov.tr/cografi-isaretler/detay/3702 (Erişim: March 07, 2024)

Folgado-Fernández, J. A., Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., and Duarte, P. (2017). Destination image and loyalty development: the impact of tourists’ food experiences at gastronomic events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 17, 92–110. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2016.1221181

Fu, H., Ma, M., and Zhu, X. (2023). Understanding Thailand’s tourism industry from the perspective of tweets: a qualitative content analysis using NVivo 12.0. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 21, 430–442. doi: 10.21511/ppm.21(4).2023.33

Fusté-Forné, F. (2020). Say gouda, say cheese: travel narratives of a food identity. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 22:100252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100252

Ghadge, A., Er Kara, M., Mogale, D. G., Choudhary, S., and Dani, S. (2021). Sustainability implementation challenges in food supply chains: a case of UK artisan cheese producers. Prod. Plan. Control 32, 1191–1206. doi: 10.1080/09537287.2020.1796140

Gokee, C., and Logan, A. L. (2014). Comparing craft and culinary practice in Africa: themes and perspectives. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 31, 87–104. doi: 10.1007/s10437-014-9162-7

González, N., Marquès, M., Nadal, M., and Domingo, J. L. (2020). Meat consumption: which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences. Food Res. Int. 137:109341. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109341

Guiné, R. P., Florença, S. G., Barroca, M. J., and Anjos, O. (2021). The duality of innovation and food development versus purely traditional foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 109, 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.010

Haberle, D. C. (2021). Food tourism as a strategy for regional economic development-a case study comparison of cheese producing regions (Doctoral dissertation). University of Groningen Faculty of spatial sciences in economic geography.

Haven-Tang, C., and Jones, E. (2005). Using local food and drink to differentiate tourism destinations through a sense of place: a story from Wales-dining at Monmouthshire's great table. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 4, 69–86. doi: 10.1300/J385v04n04_07

Horng, J. S., and Tsai, C. T. (2012). Culinary tourism strategic development: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 14, 40–55. doi: 10.1002/jtr.834

Ishtiaq, M. (2019). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage.

Jones, S., and Yarrow, T. (2013). Crafting authenticity: an ethnography of conservation practice. J. Mater. Cult. 18, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/1359183512474383

Jongenelis, M. I., Talati, Z., Morley, B., and Pratt, I. S. (2019). The role of grandparents as providers of food to their grandchildren. Appetite 134, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.022

Kalekahyası, S., and Göktaş, B. (2022). Coğrafi işaret almış yöresel ürünlerin bilinirlik düzeyi ve tüketici tutumlarına etkisi: Bayburt ili örneği. Stratejik Ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 6, 673–702. doi: 10.30692/sisad.1142517

Kivela, J., and Crotts, J. C. (2006). Tourism and gastronomy: Gastronomy’s influence on how tourists experience a destination. J. Hospit. Tour. 30, 354–377. doi: 10.1177/1096348006286797

Kovalenko, A., Dias, Á., Pereira, L., and Simões, A. (2023). Gastronomic experience and consumer behavior: analyzing the influence on destination image. Food Secur. 12:315. doi: 10.3390/foods12020315

Lee, E., and Zhao, L. (2023). Understanding purchase intention of fair trade handicrafts through the Lens of geographical indication and fair trade knowledge in a brand equity model. Sustain. For. 16:49. doi: 10.3390/su16010049

Lees, N., Nuthall, P., and Wilson, M. M. (2020). Relationship quality and supplier performance in food supply chains. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 23, 425–445. doi: 10.22434/IFAMR2019.0178

Lin, Y. S., and Lin, M. H. (2022). Exploring indigenous craft materials and sustainable design—a case study based on Taiwan Kavalan Banana fibre. Sustain. For. 14:7872. doi: 10.3390/su14137872

Lin, M. P., Marine-Roig, E., and Llonch-Molina, N. (2022). Gastronomic experience (co)creation: evidence from Taiwan and Catalonia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 47, 277–292. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2021.1948718

Liu, M., Tang, H., Wang, Y., Li, R., Liu, Y., Liu, X., et al. (2023). Enhancing food supply chain in green logistics with multi-level processing strategy under disruptions. Sustain. For. 15:917. doi: 10.3390/su15020917

López-Guzmán, T., Uribe Lotero, C. P., Pérez Gálvez, J. C., and Ríos Rivera, I. (2017). Gastronomic festivals: attitude, motivation and satisfaction of the tourist. Br. Food J. 119, 267–283. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2016-0246

MacDonald, C. A., Aubel, J., Aidam, B. A., and Girard, A. W. (2020). Grandmothers as change agents: developing a culturally appropriate program to improve maternal and child nutrition in Sierra Leone. Cur. Dev. Nutrit. 4:nzz141. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz141

Meissner, F. (1976). Book review: improving food Marketing Systems in Developing Countries: the experience from Latin America. J. Mark. 41, 128–150. doi: 10.1177/002224297704100133

Mera-Shiguango, A. P., Castro-Delgado, C. J., and ve Vega-Játiva, M. (2022). The role of ancestral knowledge in the development of agriculture in the south-central microregion of Manabí, Ecuador. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Human. 6, 220–232. doi: 10.53730/ijssh.v6n3.13706

Mora, D., Solano-Sanchez, M. A., Lopez-Guzman, T., and Moral-Cuadra, S. (2021). Gastronomic experiences as a key element in the development of a tourist destination. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 25:100405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2021.100405

Moral-Cuadra, S., Martín, J. C., Román, C., and López-Guzmán, T. (2023). Influence of gastronomic motivations, satisfaction and experiences on loyalty towards a destination. Br. Food J. 125, 3766–3783. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-02-2023-0121

Mulyantari, E., Hasnah, V. A., and Nugroho, S. P. (2023). Culture, history, and Bakpia Pathok processing method as a gastronomic tourist attraction in Yogyakarta. Techn. Soc. Sci. J. 40, 305–316. doi: 10.47577/tssj.v40i1.8465

Murgado, E. M. (2013). Turning food into a gastronomic experience: olive oil tourism. Options Mediter. 106, 97–109. Available at: http://om.ciheam.org/om/pdf/a106/00006809.pdf

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., and Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 22:16094069231205789. doi: 10.1177/16094069231205789

Nicoletti, S., Medina-Viruel, M. J., Di-Clemente, E., and Fruet-Cardozo, J. V. (2019). Motivations of the culinary tourist in the city of Trapani, Italy. Sustain. For. 11:2686. doi: 10.3390/su11092686

Oğan, Y., and Çelik, M. (2023). A gastronomic product in Turkish culinary culture: a research on Yozgat Çanak cheese. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 31:100650. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100650

Oğan, Y., Keskin, M. A., and Bulut, Z. (2024). A gastronomic product specific to the Caucasus region culinary: Khinkali (ხინკალი) and Hinkal. J. Multidiscip. Acad. Tour. 9, 179–189. doi: 10.31822/jomat.2024-9-2-179

Öğretmenoğlu, M., Çıkı, K. D., Kesici, B., and Akova, O. (2023). Components of tourists' palace cuisine dining experiences: the case of ottoman-concept restaurants. J. Hospit. Tour. Insights 6, 2610–2627. doi: 10.1108/JHTI-06-2022-0228

Petrescu, D. C., Vermeir, I., and Petrescu-Mag, R. M. (2020). Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: a cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:169. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010169

Richards, G. (2012). “An overview of food and tourism trends and policies” in Food and the tourism experience: the OECD-Korea workshop. ed. OECD (Paris: OECD Publishing), 13–46.

Samancı, Ö. (2008). The culinary culture of the Ottoman palace and Istanbul during the last period of the Empire. T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınları, 199–219. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283491497_The_Culinary_Culture_of_the_Ottoman_Palace_Istanbul_during_the_last_period_of_the_Empire (Accessed March 10, 2024).

Santa Cruz, F. G., Tito, J. C., Pérez-Gálvez, J. C., and Medina-Viruel, M. J. (2019). Gastronomic experiences of foreign tourists in developing countries. The case in the city of Oruro (Bolivia). Heliyon 5, e02011–e02018. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02011

Şengül, S. (2017). Türkiye’nin Gastronomi Turizmi Destinasyonlarının Belirlenmesi: Yerli Turistler Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Balıkesir Üniv. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 20, 375–396. doi: 10.31795/baunsobed.645178

Şeyhanlıoğlu, H. Ö. (2023). Gastronomi Turizmine Karşı Yerel Halkın Bilgi ve Tutum Düzeyinin Belirlenmesine Yönelik Araştırma: Ağrı İli Örneği. Avrasya Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi, 4. Özel Sayı: Türk Turizminin Geçmiş ve Gelecek Yüzyılı, 34–45.

Sezen, İ., and Külekçi, E. A. (2020). Kentsel Kimlik Bileşenleri ve Kış Turizmi İlişkisi: Erzurum Kenti Örneği. Atatürk Üniv. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 24, 1799–1810. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ataunisosbil/issue/59389/653719

Spina, D., Barbieri, C., Carbone, R., Hamam, M., D’Amico, M., and ve Di Vita, G. (2023). Market trends of medicinal and aromatic plants in Italy: future scenarios based on the Delphi method. Agronomy 13:1703. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13071703

Suleiman, M. S. M., Sharif, M. S. M., Fuza, Z. I. M., and Azwar, H. (2023). Determinants of traditional food sustainability: Nasi Ambeng practices in Malaysia. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 8, 143–155. doi: 10.21834/e-bpj.v8i25.4856

Tebben, M. (2015). Seeing and tasting: the evolution of dessert in French gastronomy. Gastronomica 15, 10–25. doi: 10.1525/gfc.2015.15.2.10

Tehrani, J. J., and Riede, F. (2008). Towards an archaeology of pedagogy: learning, teaching and the generation of material culture traditions. World Archaeol. 40, 316–331. doi: 10.1080/00438240802261267

Tekelioğlu, Y. (2019). Coğrafi işaretler ve Türkiye uygulamaları. Ufuk Üniv. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 8, 47–75. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ufuksbedergi/issue/57470/815063

Thangaraja, A. (2018). The consumer experience on geographical indicators and its impact on purchase decision: an empirical study. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 118, 2625–2630.

Torres Bernier, E. (2003). “Del turista que se alimenta al que busca comida” in Reflexiones sobre las relaciones entre gastronomía y turismo. eds. G. Lacanau and J. Norrild (Cultura al Plato: Gastronomia y Turismo), 306–316.

Uçuk, C. (2023). A comparative study of gastronomy education in two culinary capitals: Lyon and Gaziantep. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 11, 512–522. doi: 10.21325/jotags.2023.1204

Üzümcü, T. P., Alyakut, Ö., and Fereli, S. (2017). Gastronomik ürünlerin coğrafi işaretleme açısından değerlendirilmesi: Erzurum-Olur örneği. Tarım Bilimleri Araştırma Dergisi 10, 44–53. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tabad/issue/35729/398512

Üzümcü, T. P., and Denk, E. (2019). Erzurum ile Özdeşleşmiş Bir Lezzet: Oltu Cağ Kebabı (a taste which is identical with Erzurum; Cağ kebab of Oltu). J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 7, 463–483. doi: 10.21325/jotags.2019.373