- College of Economics, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

Introduction: Although rural industrial integration is a crucial pathway for advancing the revitalization of rural economies, it continues to grapple with financial challenges. This paper delves into the theoretical underpinnings of how capital marketization influences rural industrial integration.

Methods: Using panel data from China’s provinces spanning the years 2010 to 2020, a comprehensive index of rural industrial integration is constructed from the vantage point of a new development paradigm. The paper employs the system GMM method to empirically investigate the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration and to dissect its transmission mechanisms. Additionally, a threshold regression model is applied to explore the specific patterns of the nonlinear relationship between the two variables.

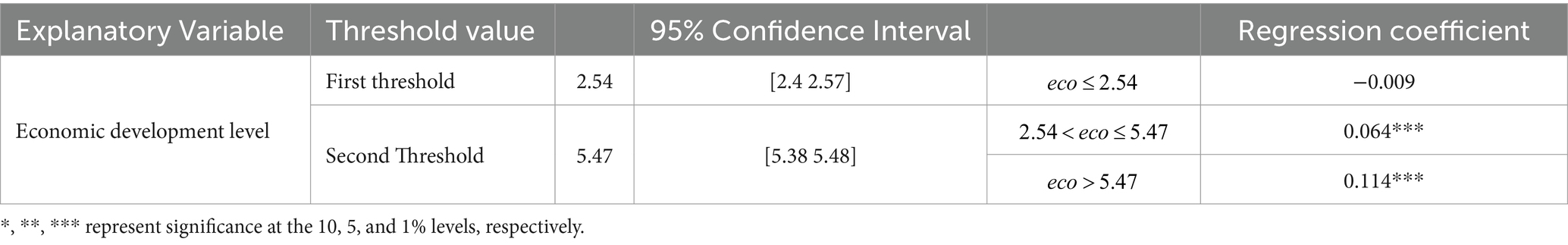

Results and discussion: The study’s findings reveal that the degree of rural industrial integration is significantly and positively influenced by its previous level, demonstrating an accumulative effect wherein the prior level of integration lays the groundwork for future advancements. The influence of capital marketization on the degree of rural industrial integration is characterized by a non-linear relationship, adhering to a “U-shaped” curve. Below the inflection point, the development of capital marketization is detrimental to rural industrial integration, whereas above this point, it exerts a positive influence. Currently, China’s overall level of capital marketization is positioned beyond the inflection point, indicating substantial potential for enhancing industry integration in rural China. In addition, the study indicates that at very low levels of economic development, capital marketization does not affect the development of rural industries. As the economic development level rises, so does the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration.

1 Introduction

The promotion of the integration of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries in rural areas (hereinafter referred to as “rural industry integration”) is a pivotal measure for the revitalization of rural regions. Capital marketization has risen as an effective approach to mitigate the financial challenges encountered in this integration process. Historically viewed, industry integration represents an inevitable trend in the development trajectory of rural industries. Since the initiation of China’s rural reform in 1978, marked by the introduction of the household contract responsibility system, the essence of rural reform has centered on the realignment of production relations. This has significantly bolstered the dynamism of rural agricultural development and disrupted the previously isolated status of various agricultural processes. In 1992, China outlined the goal of establishing a socialist market economy system, placing increased emphasis on the regulating role of the market in rural economic development. As the market economy evolved, the traditional fragmented farming practices became insufficient to satisfy evolving development demands. To reconcile the disparity between “small-scale farmers” and the “large-scale market,” an integrated agricultural industrial operation model emerged in China’s rural areas. This model, grounded in family contract farming, encompasses the entire spectrum from production to processing to sales. The exchange of factors between urban and rural areas intensified, propelling swift rural industrial development and fostering tighter integration among the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors. In 2015, China proposed the concept of advancing rural industry integration, underscoring its importance as a cornerstone in the construction of a modern agricultural industry system. In 2018, China reaffirmed its dedication to fostering the integration of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries in rural areas, vigorously advancing the development of agricultural modernization and the realization of the rural revitalization strategy.

At this stage, China’s agricultural industry chain is continuously expanding, and the entities involved in rural industry integration are growing more diverse and robust. The emergence of new agricultural industries and innovative formats is accelerating, with novel models for rural industry integration continually being developed and explored. The development of rural industry integration has become an essential pathway for the progress of social production in the contemporary era. It is also an imperative for the transformation and modernization of rural economies, a vital strategy for fostering integrated urban–rural development, a key driver for structural reform on the agricultural supply side, and a critical means to ensure sustained income growth for farmers (Chen et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). China’s rural industry integration is now at a pivotal juncture, transitioning from an initial exploratory phase to a period of rapid acceleration. However, this complex endeavor confronts a multitude of challenges. The most prominent of these is the presence of bottleneck constraints on various factors, particularly the significant shortfall in capital support. This financial shortfall has plunged rural industry integration into a profound predicament.

Challenges in the agricultural and rural sectors, including difficulties in securing financing, high costs of borrowing, and sluggish lending processes, underscore the importance of financial support as a vital catalyst for the advancement of rural industry integration. Strengthening this support is fundamentally linked to the enhancement of rural capital market development (Lopez and Winkler, 2018). However, within an environment characterized by imperfect competition, the marketization of capital elements could potentially skew the allocation of production factors towards industry integration models that are more responsive to market demands. Paradoxically, this dynamic may, in fact, impede the progress of rural industry integration. Existing research suggests that government support (Steiner and Teasdale, 2019), social capital (Lang and Fink, 2019), financial services (Khanal and Omobitan, 2020), digital technology (Cowie et al., 2020), among others, can significantly enhance agricultural performance and promote the development of rural industry integration. Nonetheless, there remains a dearth of research elucidating the precise mechanisms through which the marketization of capital influences the development of rural industry integration.

The primary objective of this paper is to examining the influence of capital marketization on the development of rural industry integration. It aims to assess whether capital marketization can effectively alleviate the financial constraints faced by rural industries during the integration process and to clarify the mechanisms by which it influences this process. The article makes three contributions. Firstly, it measures rural industry integration using the new development concept, which includes five dimensions: innovation, coordination, green development, openness, and sharing. Secondly, it uncovers the mechanisms through which the marketization of capital influences rural industry integration, investigating the theoretical basis for the dynamic process of current capital market reforms in alleviating the financial challenges of rural industry integration development. Thirdly, it employs the System GMM method to verify the effects of the marketization of capital elements in unleashing the potential of rural industry integration development, clarifying the role and impact pathways of the marketization of capital elements on rural industry integration.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review and Section 3 establishes research hypotheses. Section 4 presents the conceptual framework and the data used in the study. The empirical results are then reported in section 5. The final section presents concluding remarks and implications.

2 Literature review

Industrial integration typically originates from technological interconnections between various sectors, which in turn leads to the blurring or dissolution of traditional industry boundaries. In the late 1990s, Japanese agricultural expert Naraomi Imamura introduced the concept of the “Sixth Industry,” formally incorporating agriculture into the realm of industrial integration research. In China, rural industry integration is led by innovative business entities, interconnected through a mechanism that fosters shared interests. It is driven by the momentum of technological innovation, institutional innovation, and format innovation, guided by the new development concept of “innovation, coordination, green development, openness, and sharing.” The reform agenda is centered on facilitating the free flow of factors, optimizing the allocation of resources, and achieving an organic integration of industries. The overarching objectives are to enhance agricultural productivity, augment farmers’ incomes, and stimulate rural prosperity.

In recent years, research on rural industrial integration has mainly focused on three areas. Firstly, some studies concentrate on exploring the pathways of rural industry integration. These pathways are crucial for promoting the revitalization of rural industries and achieving a more sustainable village economy (Qin et al., 2020). Key pathways for integration include the integration of crop and livestock farming, the expansion of industrial chains in both upstream and downstream directions, the diversification of agricultural industry functions, the steering role of industrial and commercial capital and leading enterprises, and the establishment of horizontal industrial integration platforms along with the evolution of Internet + agricultural industry (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2023). Secondly, scholars have investigated the construction of evaluation index and relevant measurements for assessing the level of rural industrial integration. Existing literature primarily measures rural industry integration from three perspectives. Initially, it evaluates the interaction and socio-economic impacts of the integration between agriculture and related industries, such as the extension of agricultural industry chains, the multifunctionality of agriculture, the development of agricultural service industries, the enhancement of farmers’ income, job creation, and the integration of urban–rural development (Zhang and Wu, 2022). Subsequently, it examines rural industry integration through the lens of its types, such as industrial restructuring, extension, cross-linking, and penetration (Hao et al., 2023). Finally, in light of the new development concept, scholars have developed evaluative frameworks for rural industry development across five dimensions: innovation, coordination, green development, openness, and sharing (Liu et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2018). Thirdly, some studies concentrate on the challenges encountered by rural industry integration. Despite the positive momentum of recent developments, rural industry integration still face various difficulties. Many regions in China involve in this integration are grappling with issues such as low levels of integration and superficial integration depths. In the course of rapid urbanization, which is characterized by profound shifts in population, land, and industry dynamics, specific rural areas are universally dealing with a dearth of motivation for industrial development, an intensifying phenomenon of rural land hollowing, weakened grassroots governance structures, a fragile mainstream of rural development, and a scarcity of public infrastructure (Tu et al., 2018). Villages constitute interconnected organic entities with the circulation of resources such as labor, capital, material, and information (Lopez and Winkler, 2018; Li et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2020). Among these, capital has emerged as a pivotal factor restricting regional development in rural China (Guo et al., 2022), where factor mobility plays a significant role in determining the economic benefits of development (Banerjee et al., 2020).

Accordingly, some studies has focused on the financial challenges faced by rural industry integration, seeking to identify strategies to mitigate these financial difficulties and promote further industrial integration. A significant body of the research indicates that the financial challenges in the development of rural industry integration mainly arise from an insufficient capital support. Investing industrial and commercial capital into agriculture has been recognized as a potential solution to address the shortage of financial resources (Long et al., 2016). Such capital inflow can provide agriculture with essential inputs such as funding, technological advancements, and skilled personnel (Cofré-Bravo et al., 2019). However, it is noteworthy that increased agricultural productivity may paradoxically lead to capital outflows from rural regions. This occurs as productivity gains can lower interest rates, prompting capital to migrate optimally towards the urban manufacturing sector in search of higher returns (Bustos et al., 2020). Conversely, an alternative perspective from other research suggests that the financial challenges confronting rural industry integration are multifaceted and cannot be solely attributed to capital scarcity. The agricultural sector demands substantial investments that are fraught with high risks and characterized by long gestation periods for returns. Typically, individual operating entities struggle to shoulder these financial burdens on their own, highlighting the need for ongoing innovation in the financial markets to develop tailored rural financial products (Adegbite and Machethe, 2020). Additionally, it is imperative to harness the market’s role in resource allocation effectively. Evidence suggests that market forces have a pronounced impact on industrial integration, particularly in provinces with a more advanced degree of marketization (Tian et al., 2020). The degree of economic marketization is identified as a pivotal factor in enhancing the efficiency of capital allocation across different regions within China (Zhang et al., 2021).

Although there have been some empirical analyses on marketization, and a significant body of research has explored the construction of evaluation indicators for factor marketization, there is a scarcity of literature directly measuring capital marketization. Existing studies primarily focus on the measurement of factor marketization, land factor marketization, and production factor marketization. Fan et al. (2003) previously developed a marketization index for various provinces in China, including five dimensions: government and market, the ownership structure, goods market development, factors market development and the legal framework. Yan (2007) measured the degree of marketization in China by constructing an index that encompasses the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors. When considering a comprehensive assessment of factor marketization, Zhou and Hall (2019) calculated a relative index of marketization processes across different regions of China, considering five aspects: the relationship between government and market, the development of the non-state-owned economy, the maturity of product market development, the advancement of factor market development, and the establishment of market intermediary organizations and the legal system environment. The urban land marketization level is typically gauged by the proportion of land allocated through tender, auction, and listing relative to the total land supply (Cheng et al., 2022). Regarding rural land marketization, Yao and Wang (2022) used the year 2008 as an indicator of agricultural land marketization in China when the country decided to strengthen the development of the agricultural land transfer market and improve the transfer rate.

In summary, the findings from existing research offer substantial insights for the theoretical analysis within this paper, underscoring the innovative aspects and contributions of this study. On the one hand, market-oriented reforms have emerged a focal point of current economic development. Yet, the role of capital marketization in facilitating rural industry integration has received scant scholarly attention. Capital marketization, which is distinct from capital itself, encompasses a dynamic process that includes a range of economic, social, legal, and systemic reforms. The marketization of capital is essential for the free flow and rational distribution of capital, particularly in the structuring of rural financial institution networks. These elements are vital to the development process of rural industry integration.

This study employs a dynamic approach to investigate the financial challenges faced by rural industry integration and mechanisms for their mitigation, offering valuable perspectives on tackling financial issues in the development of rural industry integration in China. This research carries significant implications for formulating of future policies related to the advancement of rural industry integration in the country. On the other hand, the implementation of the new development philosophy is a vital pathway for China’s progress in the new era. As a leading agricultural nation, China’s agricultural development must align with and implement the new development philosophy. Currently, there is scarce research that measures the effectiveness of rural industry integration from the perspective of this philosophy. This study takes a starting point from the new development philosophy, formulates indicators to measure rural industry integration, and integrates rural industry integration deeply with the new development philosophy. This approach provides novel empirical evidence to inform the development of targeted financial policies aimed at propelling rural industry development.

3 Theoretical analysis and hypotheses

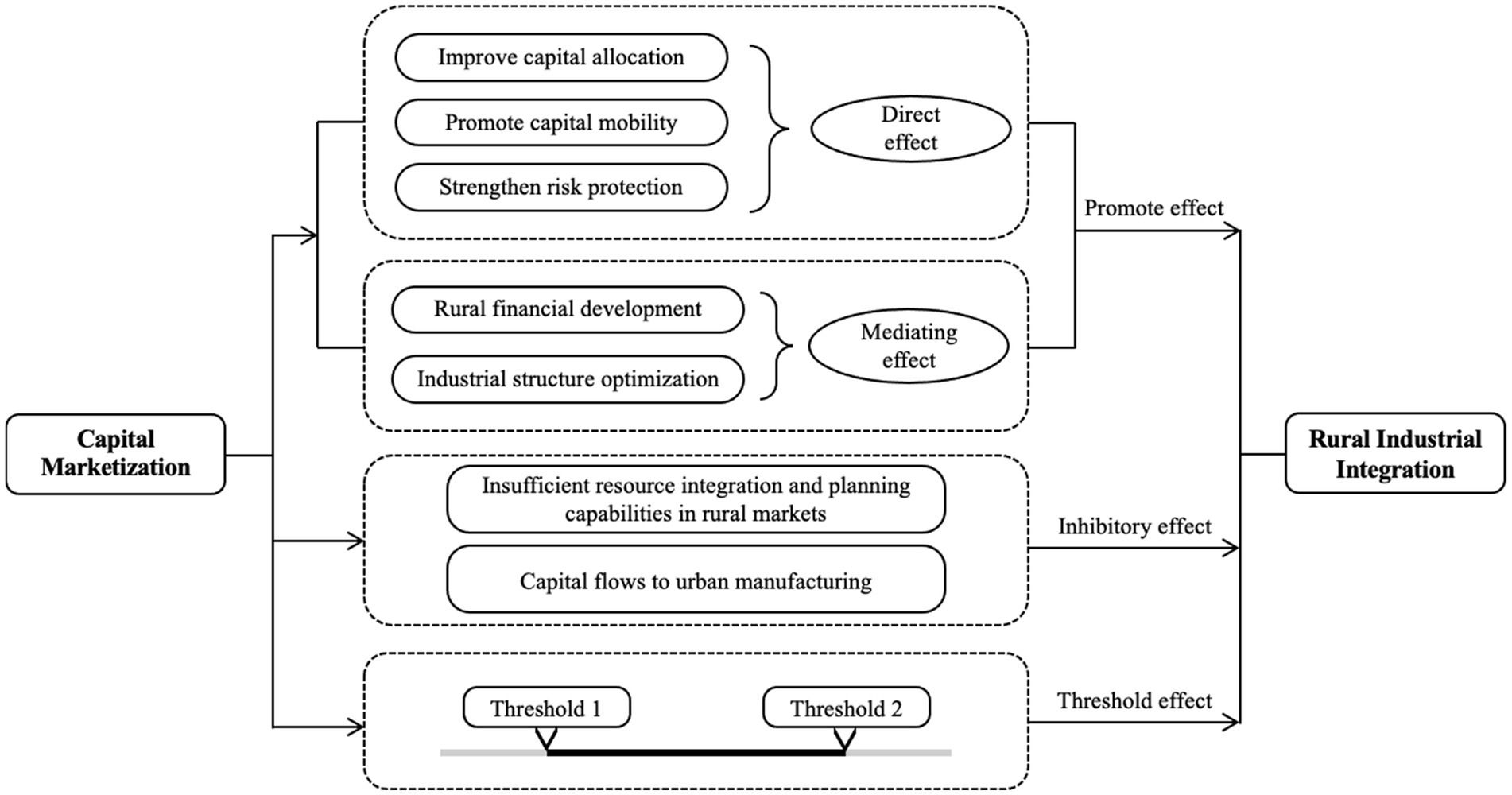

Summarizing the viewpoints from existing literature, this paper proposes that the impact of capital marketization on rural industry integration is nonlinear, exhibiting both positive and negative aspects. The positive impact comprises direct and mediating effects. The direct effect indicates that capital marketization fosters the development of rural industry integration by improving the efficiency of capital allocation, promoting the mobility of capital, and mitigating risks associated with agricultural production. The mediating effect refers to the indirect roles played by the development of rural finance and the optimization of industrial structure, which shape rural industry integration in the context of capital marketization. Conversely, the negative impact suggests that at low levels of capital marketization, the market’s capacity for integration planning is less than optimal. The marketization process might drive production factors towards configurations more aligned with market needs, thereby inhibiting the development of rural industry integration. Additionally, the facilitative role of capital marketization in rural industry integration is subject to constraints imposed by the threshold of regional economic development (see Figure 1).

3.1 Direct effects of capital marketization on rural industry integration

The concept of marketization finds its origins in the “Financial Deepening Theory,” initially proposed by Shaw (1973) and McKinnon (1973). This theoretical framework emerged as a counterpoint to the financial repression policies that were prevalent in some developing countries during that era. The theory championed the liberalization of financial markets, advocating for the easing or even the dissolution of governmental financial controls, and the adoption of market-determined interest rates. These rates were intended to genuinely mirror the market’s supply and demand dynamics for capital. Consequently, the allocation of capital would be steered by market mechanisms, thereby empowering financial markets to effectively contribute to the allocation of resources. This study posits that the Financial Deepening Theory implies a fundamental logic: the more advanced the development of the financial sector, the more effectively it can serve the production sector. Enhanced service leads to improved capital allocation efficiency, which in turn stimulates industrial development and fosters economic growth.

The development of rural industry integration requires a large amount of capital collaboration, indicative of a capital accumulation process. Capital marketization enables the fluid and expeditious movement of capital within the market, directing surplus funds towards sectors that demand capital for growth (Petry, 2020). This process is instrumental in enabling industries or enterprises in need of development to secure financing for innovative integration initiatives. Consequently, this transformation in the developmental approach of rural industries fosters the enhancement of industrial chains and facilitates the realization of rural industry integration. Furthermore, capital marketization significantly improves the efficiency of resource allocation. It does so by attracting additional capital, stimulating the expansion of savings, augmenting the availability of funds, offering investment and financing avenues, easing the financial strain on rural industry integration, and tackling the prevalent issues of “difficulty in securing financing” and “high cost of financing.” Moreover, capital can mitigate the risks associated with the adoption of new technologies, diminish the risk perceptions of investors in agriculture-related sectors, and disperse the concentration of risks inherent in the rural industry integration process, thereby fostering its progression (Clapp, 2019).

However, in scenarios where the level of marketization is insufficient, the interest linkage mechanism within rural industries remains underdeveloped. The process of marketization tends to channel more robust production factors towards integration models that align more closely with market demands. This dynamic may impede small-scale farmers from participating in the modern agricultural system, thereby obstructing the overall advancement of rural industry integration. Additionally, considering the diverse sectors involved in rural industry integration and their complex interconnections, an inadequate level of marketization impairs the market’s capacity to effectively integrate and strategically plan capital allocation (Liu et al., 2023). Based on the analysis above, this paper proposes Hypothesis 1:

H1: The influence of capital marketization on rural industry integration is nonlinear. At low levels of capital marketization, the marketization process inhibits rural industry integration. In contrast, at high levels of capital marketization, the marketization process is expected to foster rural industry integration.

3.2 Mediating effects of rural financial development on industrial structure optimization

In China’s rural financial sector, market failure and inefficient government intervention are prevalent issues. The market environment in rural finance is not yet fully mature, and a commitment to market-oriented reforms can enhance the rural financial market environment (Han, 2020). Such reforms have the potential to augment the provision of financial support for rural revitalization, tackle institutional and technological impediments in rural financial development, and bolster the efficiency of rural financial services (Yaseen et al., 2018). The marketization process represents an efficient mechanism for resource allocation, preventing significant distortions in the distribution of rural financial resource. It addresses the capital requirements for rural economic development at a fundamental level and promotes the advancement of rural finance. Advancements in marketization can stimulate innovation in rural financial products and services, broaden the reach of financial services, amplify the scope of agricultural insurance, and bolster the development of rural industry integration. Moreover, the enhancement of marketization can standardize transaction systems within factor and product markets, ensuring the rational allocation of resources. This drives the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure. A more rational industrial structure can encourage the reallocation of surplus rural labor from agriculture to secondary and tertiary sectors (Long et al., 2016). Consequently, this reallocation can raise both urban and rural income levels, thereby nurturing the development of rural industry integration. Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 2:

H2: Capital marketization is posited to influence rural industry integration by fostering the development of rural finance and by driving the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure.

3.3 Threshold effect of regional economic development

The progression of rural industry integration is influenced not only by the development of rural finance and the composition of industry but also significantly by the level of local economic development. In regions where the economic development is comparatively advanced, capital marketization can enhance the mobility of capital and effectuate rational resource allocation, thereby actively fostering the development of rural industry integration (Xu and Tan, 2020). On the contrary, in regions with lower levels of economic development, there may be a pervasive financial conundrum stemming from capital scarcity, and external capital might be disinclined to invest in areas with less robust economic development. In these contexts, the scope of resources that capital marketization can effectively allocate is constrained, which can substantially impede its capacity to promote rural industry integration. Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 3:

H3: There exists a threshold effect of the regional economic development on the promotion of rural industry integration by capital marketization.

4 Methodology

4.1 Econometric model specification

The econometric model in this study is composed of three components. Firstly, a dynamic panel model is used to analyze whether the current level of rural industry integration is influenced by capital marketization and the previous level of rural industry integration. Secondly, a mediation effects model is employed to further verify the mechanism through which capital marketization affects rural industry integration. Thirdly, a threshold effects model is introduced, integrating the level of economic development as a threshold variable. This model is designed to explore the conditional nature of the relationship between capital marketization and rural industry integration, taking into account the potential threshold effects that economic development may impose on this dynamic.

4.1.1 Dynamic panel data model

This study undertakes an examination of the impact of capital marketization on the level of rural industry integration by employing the level of rural industry integration as the dependent variable and the level of capital marketization as the core explanatory variable. The benchmark panel model is constructed as follows:

where, represents each province (or municipality), represents the year, and represent the level of rural industry integration and the level of capital marketization, respectively. is the intercept, is the regression coefficient of the capital marketization, represents fixed effects, and is the random disturbance term.

To encompass the influence of additional factors, such as rural education level ( ), economic openness ( ), rural ecological environment ( ), urbanization level ( ), and government financial support ( ), the model is adjusted to include these variables. The extended panel model is given by Equation 2:

where are the regression coefficients for these control variables. All other terms have the same meanings as described in the benchmark model (Equation 1).

To account for a potential non-linear relationship between rural industry integration and capital marketization, this study introduces the quadratic term of capital marketization in the model. The static panel model is constructed as Equation 3:

where represents the squared term of capital marketization, … are the regression coefficients for the core explanatory variables and control variables. In the model (3), if and are significantly non-zero, the relationship between capital marketization and rural industry integration can be determined based on the signs of and . In particular, when it indicates an inverted U-shaped relationship between capital marketization and rural industry integration. That is, when the level of capital marketization is below or equal to the inflection point, it has a positive promoting effect on industry integration. When the level is above the inflection point, it has a negative inhibitory effect. When , it suggests a U-shaped relationship between capital marketization and rural industry integration. In this case, when the level of capital marketization is below or equal to the inflection point, it has a negative inhibitory effect. When the level is above the inflection point, it has a positive promoting effect on rural industry integration.

Considering that the potential influence of past levels of rural industry integration on the current state within a region, this study further incorporates the first-order lag of rural industry integration variable into the econometric model. The dynamic panel model is constructed as Equation 4:

where is the first-order lag of the rural industry integration variable, is its regression coefficient, … are the regression coefficients for the core explanatory variables and control variables.

4.1.2 Threshold regression model

In order to examine the threshold effect of economic development level on the impact of capital marketization on rural industry integration, this study employs to the panel threshold effect model proposed by Hansen (1999). The economic development level is considered as the threshold variable, and the threshold regression model is constructed as Equation 5:

where is the threshold variable representing the economic development level. is an indicator function, taking the value of 1 if the expression inside the parentheses is true and 0 otherwise. are the threshold values to be estimated for different levels of economic development.

4.1.3 Mediation effects model

Building upon the prior analysis that capital marketization can enhance rural industry integration through the facilitation of rural financial development and the optimization of industrial structure, this study employs a mediation effects analysis framework. The panel mediation effects model is structured as follows:

where represents the set of mediation variables, which includes rural financial development level and industrial structure, represents the set of control variables. In particular, Equation 6 represents the total effect model, indicating the overall effect of capital marketization on rural industry integration. Equation 7 is designed to estimate the impact of capital marketization on the levels of rural financial development and industrial structure. Equation 8 is employed to estimate the direct effect of capital marketization on rural industry integration and the indirect effects through the levels of rural financial development and industrial structure.

4.1.4 Estimation methodology

The current level of rural industry integration may be influenced by historical levels due to inertia-like factors. To account for this, this study introduces the lagged term of industry integration as an explanatory variable into the regression model, endowing it with dynamic explanatory power. However, the inclusion of lagged dependent variables can introduce endogeneity issues. The System GMM method, proposed by Blundell and Bond (1998), addresses this by estimating both the level and the first-differenced models simultaneously, which helps to mitigate concerns related to unobserved heteroscedasticity, omitted variable bias, measurement errors, and potential endogeneity.

A critical assumption for the GMM model is the absence of autocorrelation in the error term. To test this assumption, the study conducts residual autocorrelation tests (AR tests) with the null hypothesis (H0) stating that there is no autocorrelation at lag 2 in the error term. Acceptance of the null hypothesis in the AR(2) test suggests that the model specification is appropriate. Additionally, to validate the exogeneity of the instrumental variables, the Hansen J test (Over-identification test) is employed. The null hypothesis (H0) posits that the instrumental variables are valid, and acceptance of this null hypothesis confirms the suitability of the chosen instruments. In terms of estimation techniques, the System GMM model offers one-step and two-step estimation procedures. Given that the two-step estimator is more robust to heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional correlation and generally outperforms the one-step estimation, this study opts for the two-step System GMM approach to estimate (Equation 4).

4.2 Variables

4.2.1 Dependent variable

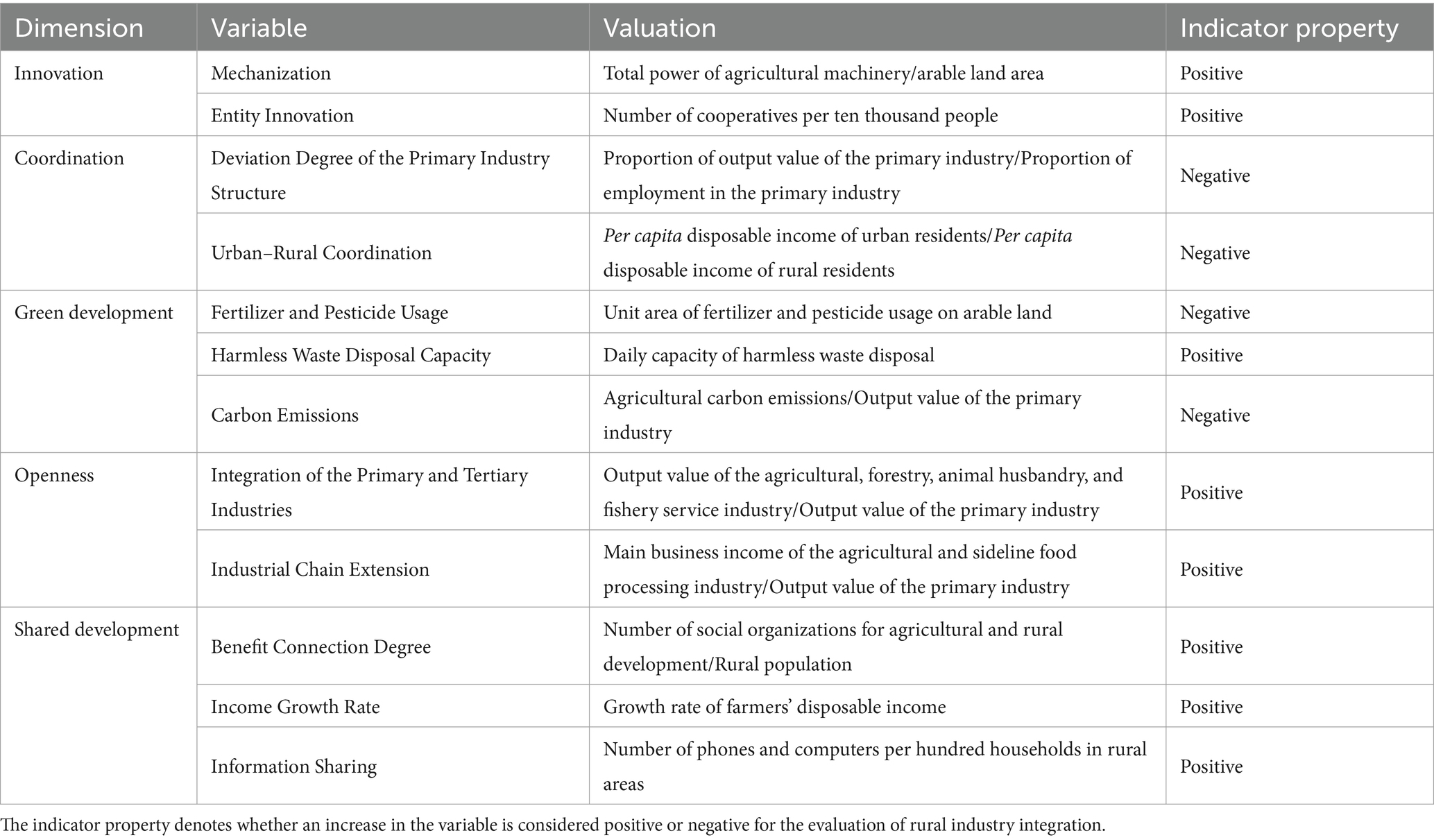

The dependent variable in this study is the development of rural industry integration ( ). The study constructs an index to measure the level of rural industry integration across five key dimensions: innovation, coordination, green development, openness, and shared development. In particular, innovation includes both innovation in cultivation methods and the innovation of integration entities. To quantify innovation in cultivation methods, the study uses the level of agricultural mechanization. The number of cooperatives per ten thousand people serves as a metric for assessing the development of integration entities. Coordination is examined through industry coordination and urban–rural coordination. The deviation degree of the primary industry structure is used to measure industry coordination, and the per capita income ratio of urban to rural residents measures the extent of urban–rural coordination. Green development is primarily concerned with the ecological performance of rural industry integration, which includes factors such as the use of fertilizers and pesticides, the capacity for harmless waste disposal, and carbon emissions. Openness is measured by looking at the development of the agricultural service industry and the extension of the industrial chain. The integration of the primary and tertiary industries is measured by the ratio of the output value of the agricultural, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery service industry to that of the primary industry. Additionally, the extension of the agricultural industry chain is measured by the ratio of the main business income of the agricultural and sideline food processing industry to the output value of the primary industry. Shared development is evaluated through the lens of benefit sharing and information sharing. The degree of benefit sharing is measured by the degree of benefit connection and income growth rate. Information sharing is quantified by the number of phones and computers per hundred households in rural households Subsequently, the study applies the entropy method to determine the weights of each secondary indicator. Using a linear weighting method, the study calculates the rural industry integration development level for each province in China from 2010 to 2020 (see Table 1).

4.2.2 Core explanatory variable

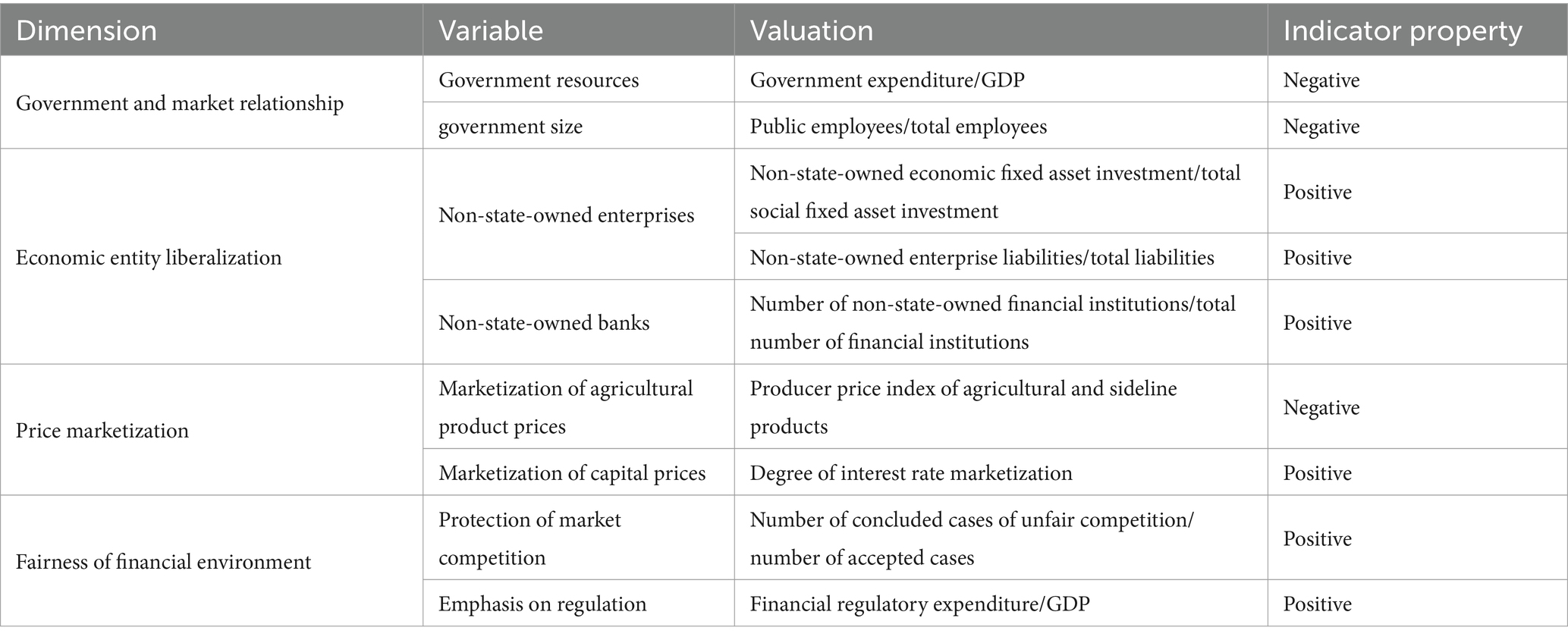

Capital marketization ( ) is the central explanatory variable in this study, referring to the establishment of market-oriented reforms within the capital market. This process involves enhancing the legal regulatory system and achieving autonomous and orderly flow of factors, as well as an efficient and fair allocation through reforms in economic and social systems. In this research, capital is specifically understood to mean financial capital. The assessment of capital marketization is constructed around four dimensions: the government-market relationship, the liberalization of economic entities, price marketization, and the fairness of the financial environment.

In particular, the government-market relationship includes government resources and government size. The proportion of government expenditure in GDP measures the extent of government resource control, with higher control potentially leading to greater market distortion and lower marketization. The proportion of public employees in the total employment reflects the size of the government, with a smaller size indicating a higher degree of marketization. Economic entity liberalization includes enterprise and bank liberalization. Enterprise liberalization is measured by the share of non-state-owned economic fixed asset investment in total societal fixed asset investment and the share of non-state-owned enterprises’ liabilities in total liabilities. These two indicators reflect the market position of non-state-owned entities, which generally align more closely with market economy principles than state-owned counterparts. Bank liberalization is measured by the proportion of non-state-owned banks in total bank assets, with a higher proportion indicating lower market concentration and greater market competition, signifying higher marketization. Price marketization covers the marketization of both agricultural products and capital prices. The marketization of agricultural product prices is measured by the producer price index of agricultural and sideline products, reflecting price stability. The marketization of capital prices is measured by the degree of interest rate marketization, with a higher degree indicating a more advanced capital marketization. The fairness of the financial environment involves the protection of market competition and the emphasis on regulation. Market competition protection is measured by the ratio of concluded to accepted cases for unfair competition violations, indicating the robustness of the market economy legal system. Greater protection equates to a more effective market economic system. The emphasis on regulation is measured by the proportion of financial regulatory expenditure in GDP. The entropy method is also used to calculate the weights of each secondary indicator (see Table 2).

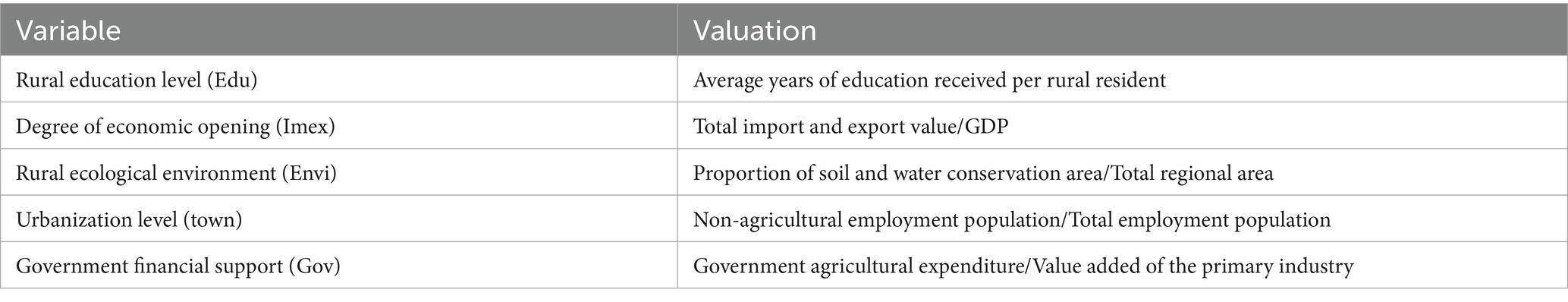

4.2.3 Other variables

In this study, the threshold variable is the level of economic development ( ), which is measured by per capita GDP. It is a comprehensive indicator that reflects the economic activities and living standards of a region.

In addition, this paper identifies rural financial development ( ) and industrial structure ( ) as mediating variables. The level of rural financial development is measured by the ratio of outstanding loans for agriculture from financial institutions in each province to the output value of the primary industry. The industrial structure, which refers to the composition of industries and the connections and proportions between them. Is measured by the ratio of non-agricultural output value to agricultural output value. An increase in this ration indicates an optimization of the industrial structure. The study also incorporates control variables that may affect the integrated development of rural industries. These include the level of rural education ( ), the degree of economic openness ( ), the rural ecological environment ( ), the level of urbanization ( ), and government financial support ( ). These variables are crucial for a thorough understanding of the factors that influence the integration and development of rural industries (see Table 3).

4.3 Data

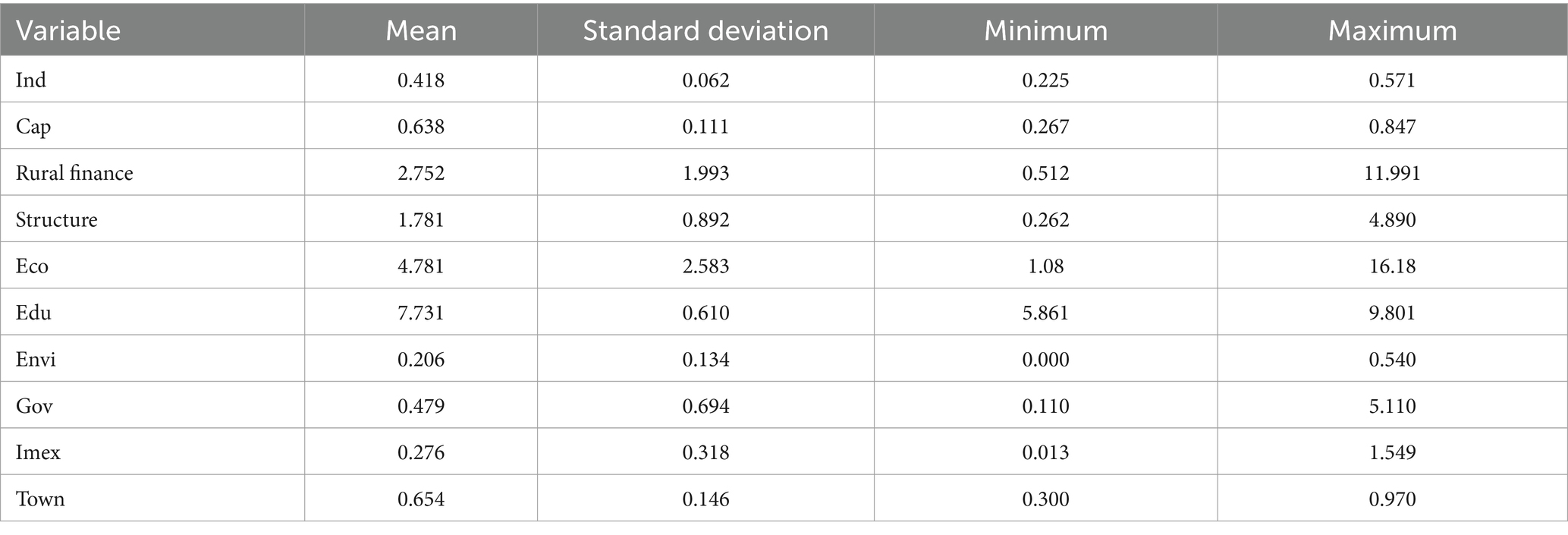

This paper utilizes a balanced panel dataset from 30 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China, covering the period from 2010 to 2020, resulting in a total of 330 observations. The data are sourced from a variety of authoritative publications, including the “China Statistical Yearbook,” “China Rural Statistical Yearbook,” “China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook,” “China Financial Statistical Yearbook,” “China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook,” “China Basic Unit Statistical Yearbook,” “China Fiscal Yearbook,” “China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook,” as well as provincial (municipal) statistical yearbooks and the Wind database. The data processing and regression analysis are primarily conducted using Stata 15 software. Descriptive statistics for each variable are presented in Table 4, offering an initial overview of the dataset’s characteristics.

As shown in Table 4, the mean value of the comprehensive index of rural industrial integration is 0.418, with a standard deviation of 0.062. The index ranges from a minimum value of 0.225 to a maximum of 0.571. These statistics indicate that the differences in the level of rural industrial integration across various regions are relatively minor, suggesting a comparatively balanced development of rural industrial integration in China.

The mean value of the capital marketization index is 0.638, with a standard deviation of 0.111, which points to substantial variability in the degree of marketization among various regions. Based on the comprehensive index of capital marketization calculated within this study, regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangsu exhibit a higher degree of marketization, whereas regions like Guizhou, Qinghai, and Guangxi are found to have a relatively lower degree of marketization.

Among the other control variables, government financial support shows a wide range, with a minimum value of 0.110 and a maximum value of 5.110, and a standard deviation of 0.694. This variation underscores the differing levels of emphasis that local governments place on supporting “agriculture, rural areas, and farmers,” highlighting the significant heterogeneity in financial commitment across regions.

5 Empirical results

5.1 Baseline regression results

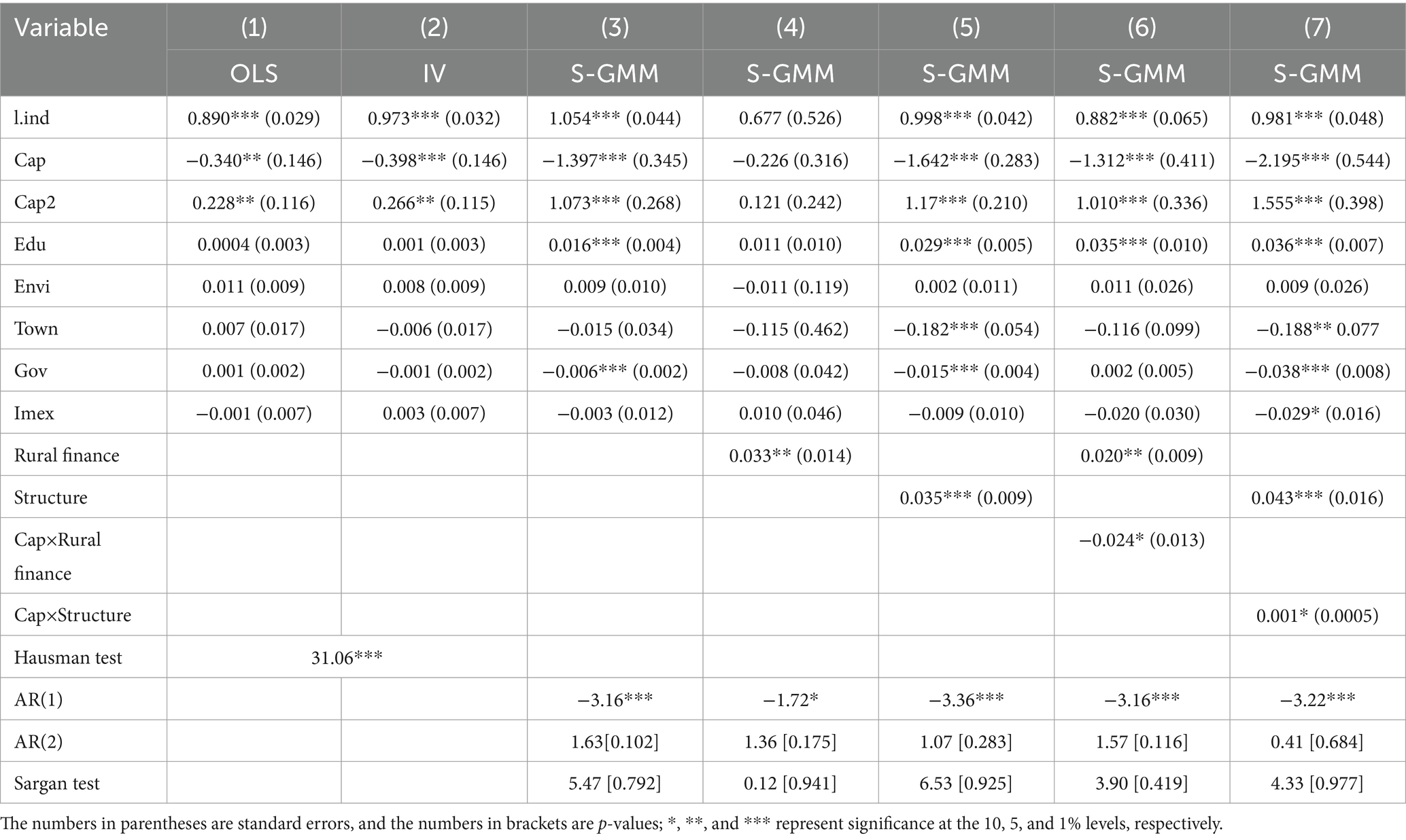

To ensure a robust comparison and to bolster the reliability of the estimation outcomes, this paper employs a variety of estimation techniques for Equation 4. Specifically, the analysis utilizes a mixed Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model, a Panel Instrumental Variable (IV) model, and a System Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) model. The comparative results of these estimations are systematically displayed in Table 5.

In Table 5, models (1) and (3) present the results of estimating Equation 4 using mixed OLS, IV, and system GMM methods, respectively. A comparative analysis is conducted, and the Hausman test in models (1) and (2) rejects the null hypothesis, indicating the presence of endogenous explanatory variables. This finding implies that an IV model is more appropriate than the OLS model for addressing endogeneity. Moreover, there is a slight increase in the significance level of the impact of capital marketization on industrial integration from model (1) to model (2). This suggests that the endogeneity issue has been partially resolved. Model (3) shows the estimation results from the system GMM. The paper also performs AR(1) and AR(2) tests on the disturbance term, setting up the null hypothesis H0: there is no autocorrelation in the model’s disturbance term. The test outcomes show that the first-order test rejects H0, while the second-order test fails to reject H0. This suggest that the model’s disturbance term exhibits first-order autocorrelation but does not indicate second-order or higher-order autocorrelation. This results supports the selection of the system GMM model as a suitable method for this study. Additionally, the Sargan test is conducted to assess the validity of the chosen instrumental variables. The test results, which accepts the null hypothesis, indicates that the instrumental variables used are essentially valid and appropriate for the analysis.

The estimation results from model (3) show that the lagged level of rural industrial integration has a significantly positive effect on its current level. This indicates that rural industrial integration exhibits characteristics of accumulation and is dependent on previous level of integration. The coefficient of capital marketization is significantly negative, but the coefficient for its square term is significantly positive, revealing a significant non-linear “U-shaped” relationship between capital marketization and rural industrial integration. This finding aligns with related research of Sun and Zhu (2022) and Liu et al. (2024), who also discovered a U-shaped relationship between financial development and rural economic growth in China. To be more specific, before the turning point of the curve, there is a significant negative relationship between the level of capital marketization and the level of rural industrial integration. Beyond the turning point, the relationship becomes significantly positive. Thus Hypothesis 1 is supported.

The turning point of the “U-shaped” curve is calculated using the formula , resulting in a value of 0.6509. This implies that when the level of capital marketization is below 0.6509, its development is likely to inhibit rural industrial integration. Conversely, when the level exceeds 0.6509, the development of capital marketization is expected to foster rural industrial integration. Notably, the average index of capital marketization in China for the year 2020 was 0.667, which is slightly above the calculated turning point of the “U” curve. This suggests that China has entered a phase where the capital marketization process is conducive to the integrated development of rural industries.

To explore the mechanisms through which capital marketization influences the integrated development of rural industries, this study incorporates the level of rural financial development and industrial structure into Equation 4. Upon introducing the level of rural financial development into the model, a notable reduction in the coefficients and significance levels of both capital marketization and its square term is observed when compared to model (3). The estimated result for the level of rural financial development is instrumental in fostering the integrated development of rural industries. This result suggests that capital marketization may exert its influence on rural industrial integration through the development of the rural financial sector. The rationale is that capital marketization facilitates the rational allocation of capital and enhances its liquidity, which in turn promotes rural financial development. A robust rural financial sector can attract additional factors and resources, effectively mitigating the constraints on rural industrial integration and alleviating financial bottlenecks. Consequently, this contributes to advancement of the integrated development of rural industries.

In model (5), the inclusion of the industrial structure variable has led to an increase in both the coefficient of capital marketization and its squared term, in comparison to model (3). The coefficient for the industrial structure is significantly positive, indicating that a more rational industrial structure benefits the integrated development of rural industries. This positive outcome may stem from the role of capital marketization in promoting the rational allocation of various resources, which in turn fosters the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure. Additionally, it aids in the reasonable distribution of rural surplus labor, thereby facilitating the integrated development of rural industries. Consequently, Hypothesis 2 is supported by these findings.

Models (6) and (7) extend the analysis by incorporating interaction terms: capital marketization multiplied by the level of rural financial development (Cap×Rural finance), and capital marketization multiplied by the industrial structure (Cap×Structure), respectively. The results indicate that the coefficients for the interaction terms in both models are significant. This signifies that capital marketization enhances the integrated development of rural industries through its impact on promoting rural financial development and optimizing the industrial structure. The significance of these interaction terms reaffirms Hypothesis 2.

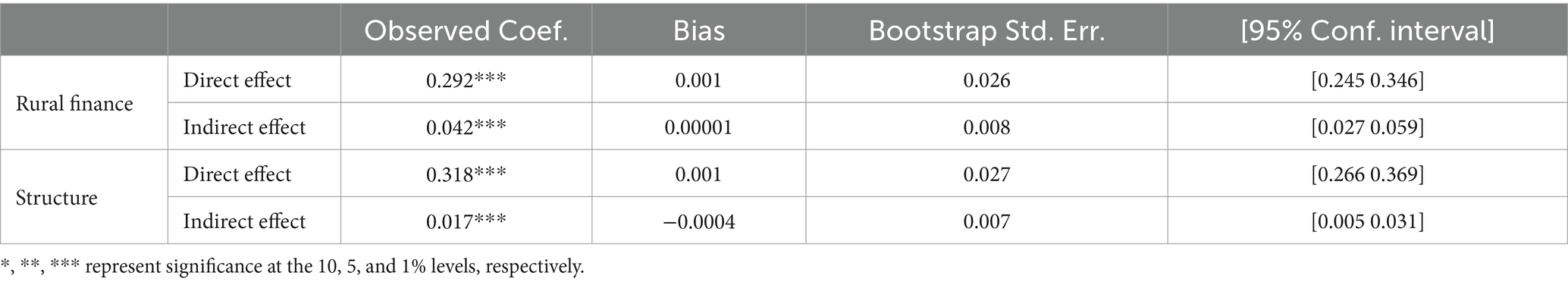

5.2 Mechanism analysis

To ensure the reliability of the aforementioned conclusions and further examine the impact mechanism of capital marketization on the integrated development of rural industries, this paper employs a mediation effect analysis. This methodical approach is utilized to scrutinize the mediating roles of two distinct pathways through which capital marketization is hypothesized to influence rural industrial integration. The test results are shown in Table 6. In Table 6, model (8) presents the regression outcomes reflecting the direct effect of capital marketization on the level of rural financial development. Model (9) illustrates the adjusted effect of capital marketization on the degree of rural industrial integration, with the inclusion of the rural financial development level as a variable. Models (10) and (11), on the other hand, display the regression results for the impact of capital marketization on the industrial structure and the combined effect of both capital marketization and the industrial structure on the degree of rural industrial integration.

The results in Table 6 indicate that capital marketization has a significantly positive impact on rural financial development. This positive impact aligns with the conclusions reached by Tian et al. (2020), who emphasized the substantial role of rural finance in fostering industrial integration. When both capital marketization and the level of rural financial development are incorporated into the model, they are found to significantly and positively influence the integration of rural industries. This finding indicates that rural financial development acts as a mediating factor in the relationship between capital marketization on the integrated development of rural industries. As capital marketization advances, it enhances rural financial development, mitigating the challenges of “difficulty and high cost of financing” those rural industries face, and thus effectively promoting their integrated development. Furthermore, the regression results in Table 6 indicate that capital marketization significantly and positively affects the industrial structure, which in turn significantly and positively impacts the integrated development of rural industries. This suggests that the industrial structure serves as another mediating channel through which capital marketization influences rural industrial integration. The results are consistent with the earlier regression findings, reinforcing the mediating role of the industrial structure in this context.

As shown in Table 7, the indirect effect of capital marketization on the integrated development of rural industries, as mediated by rural financial development, is 0.042, with a confidence interval CI = [0.027 0.059]. The exclusion of zero from this confidence interval substantiates the mediating role of rural financial development in the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration. Similarly, the indirect effect through the industrial structure is identified as 0.017, with a corresponding confidence interval CI = [0.005 0.031]. Once again, the absence of zero from this interval confirms the mediating influence of the industrial structure on the relationship between capital marketization and the integrated development of rural industries. Consequently, these findings corroborate Hypothesis 2, which posits that both rural financial development and the industrial structure serve as pivotal mediators in the influence of capital marketization on the advancement of rural industrial integration.

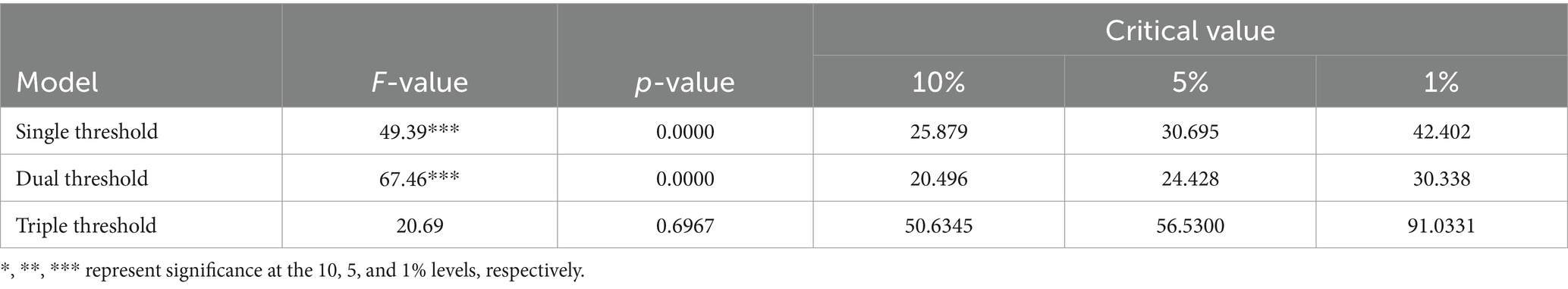

5.3 Threshold effect test

To ascertain whether the promotional effect of capital marketization on the integrated development of rural industries is moderated by the level of regional economic development, acting as a threshold, this section introduces a threshold regression model with economic development level as the threshold variable. The model examines the differences in the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration across different economic development intervals. The test results are shown in Table 8. Table 8 lists the p-values obtained from the threshold effect test, which are based on three scenarios: the presence of a single threshold, a dual threshold, and a triple threshold in the way economic development level impacts the integrated development of rural industries through the mediation of capital marketization.

The results in Table 8 indicate that when the null hypothesis assumes the absence of three threshold values, the P-statistic is 0.6967. This results does not lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis. Conversely, when the null hypothesis assumes the absence of a double threshold value, the corresponding statistical measure is 0.0000, which leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis. Based on the structure of the test and the observed outcomes, it can be preliminarily concluded that there are two thresholds in the impact of economic development level on the integrated development of rural industries, as mediated by capital marketization.

Table 9 presents the threshold estimation results. The results show that the first threshold value for economic development, within the context of capital marketization’s influence on rural industrial integration, is 2.54, with the second threshold value being 5.47. When the level of economic development is below the first threshold, the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration proves to be non-significant. This indicates that at low levels of economic development, regions encounter a financial conundrum characterized by a scarcity of capital. External capital demonstrates a reluctance to invest in areas with lower economic development, resulting in an insufficient pool of resources available for capital marketization to allocate rationally, which in turn significantly undermines its capacity to foster rural industrial integration. Upon surpassing the first threshold value, the influence of capital marketization on rural industry development transitions to a notably positive impact. Furthermore, once the economic development level surpasses the second threshold, the magnitude of the coefficient for capital marketization’s impact on rural industrial integration intensifies compared to when it is below this value. This heightened impact suggests that in regions with higher levels of economic development, there is a greater abundance of factors and resources. Consequently, capital marketization has a more substantial pool of resources to allocate rationally, thereby exerting a more pronounced role in advancing the integrated development of rural industries. In light of these findings, Hypothesis 3 is substantiated.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

6.1 Conclusion

This paper has elucidated the mechanisms by which capital marketization influences the integration of rural industries. It has developed an evaluation index for the development levels of both capital marketization and rural industrial integration, ensuring alignment with real-world scenarios and policy directions. Using dynamic panel data from China, the paper has conducted and analysis of the trends, transmission mechanisms, and threshold constraints influencing the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration. The study’s findings reveal that the degree of rural industrial integration is significantly and positively influenced by its previous level, demonstrating an accumulative effect wherein the prior level of integration lays the groundwork for future advancements. The influence of capital marketization on the degree of rural industrial integration is characterized by a non-linear relationship, adhering to a “U-shaped” curve. Below the inflection point, the development of capital marketization is detrimental to rural industrial integration, whereas above this point, it exerts a positive influence. Currently, China’s overall level of capital marketization is positioned beyond the inflection point, indicating substantial potential for enhancing industry integration in rural China. Capital marketization can stimulate rural financial development and refine the industrial structure, thereby mitigating the challenges of “difficulty and high cost of financing” and acting as a mediating pathway to foster rural industrial integration. In addition, the study indicates that at very low levels of economic development, capital marketization does not affect the development of rural industries. As the economic development level rises, so does the impact of capital marketization on rural industrial integration. Collectively, the evidence suggests that capital marketization is instrumental in advancing the integrated development of rural industries. With appropriate conditions in place, capital marketization can facilitate profound integration within rural industries and pave the way for high-quality development.

6.2 Policy implications

The research findings yield several key policy recommendations. Firstly, the accumulation of experience and factors in rural industrial integration merits attention. It is essential to continuously improve the level of rural industrial integration. In regions where rural industrial integration is advanced, ongoing efforts should focus on maintaining the utilization of existing facilities, fostering innovation among business entities, and sharing development outcomes to further enhance the dynamism of industrial integration. Conversely, in areas with lower levels of integration, strategies should aim to leverage underutilized resources, capitalize on advantageous industries, learn from the experiences of more integrated regions, and adapt development approaches to local conditions.

Secondly, with China’s overall level of capital marketization positioned to promote the integrated development of rural industries, there is an opportunity to bolster this integration. Establishing branches of rural financial institutions, ensuring adequate staffing, and advancing interest rate marketization could enhance the lending and deposit capabilities of these institutions. Such measures would elevate the level of capital marketization in China, encouraging the discovery of new agricultural roles and the emergence of innovative business models, thereby advancing the integration of rural industries.

Thirdly, given the current low overall educational level among rural residents in China, there is a pressing need to augment investment in rural education. This would elevate the educational standards of the rural populace, facilitate the transition of surplus rural labor to secondary and tertiary sectors, refine the industrial structure, and, by extension, foster deeper integration and development of rural industries.

While this study provides valuable insights, it acknowledges certain limitations and avenues for future research. The data’s temporal scope may not encompass the most recent trends and policy shifts that could influence the dynamics between capital marketization and rural industrial integration. Future studies should consider extending the timeframe of their data and broadening the research to encompass micro-level analyses for a nuanced understanding of local particularities. Additionally, a detailed examination of the specific components within the capital marketization process that lead to the observed non-linear effects could yield more precise policy directives. Despite these limitations, the research establishes a robust foundation for further exploration of the capital markets’ role in the integrated development of rural industries.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. XF: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (21CGL026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adegbite, O. O., and Machethe, C. L. (2020). Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: an untapped potential for sustainable development. World Dev. 127:104755. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104755

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., and Qian, N. (2020). On the road: access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. J. Dev. Econ. 145:102442. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102442

Blundell, R., and Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 87, 115–143. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

Bustos, P., Garber, G., and Ponticelli, J. (2020). Capital accumulation and structural transformation. Q. J. Econ. 135, 1037–1094. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjz044

Chen, K., Long, H., Liao, L., Tu, S., and Li, T. (2020). Land use transitions and urban-rural integrated development: theoretical framework and China’s evidence. Land Use Policy 92:104465. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104465

Cheng, J., Zhao, J., Zhu, D., Jiang, X., Zhang, H., and Zhang, Y. (2022). Land marketization and urban innovation capability: evidence from China. Habitat Int. 122:102540. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102540

Clapp, J. (2019). The rise of financial investment and common ownership in global agrifood firms. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 26, 604–629. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1597755

Cofré-Bravo, G., Klerkx, L., and Engler, A. (2019). Combinations of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital for farm innovation: how farmers configure different support networks. J. Rural. Stud. 69, 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.04.004

Cowie, P., Townsend, L., and Salemink, K. (2020). Smart rural futures: will rural areas be left behind in the 4th industrial revolution? J. Rural. Stud. 79, 169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.042

Fan, G., Wang, X., Zhang, L., and Zhu, H. (2003). Marketization Index for China’s Provinces. J. Econ. Res. 3, 9–18+89. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-6432.2001.06.024

Guo, Y., Zhou, Y., and Liu, Y. (2022). Targeted poverty alleviation and its practices in rural China: a case study of Fuping county, Hebei Province. J. Rural. Stud. 93, 430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.007

Han, J. (2020). How to promote rural revitalization via introducing skilled labor, deepening land reform and facilitating investment? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 12, 577–582. doi: 10.1108/CAER-02-2020-0020

Hansen, B. E. (1999). Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econ. 93, 345–368. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4076(99)00025-1

Hao, H., Liu, C., and Xin, L. (2023). Measurement and dynamic trend research on the development level of rural industry integration in China. Agriculture 13:2245. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13122245

Khanal, A. R., and Omobitan, O. (2020). Rural finance, capital constrained small farms, and financial performance: findings from a primary survey. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 52, 288–307. doi: 10.1017/aae.2019.45

Lang, R., and Fink, M. (2019). Rural social entrepreneurship: the role of social capital within and across institutional levels. J. Rural. Stud. 70, 155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.012

Li, Y., Westlund, H., and Liu, Y. (2019). Why some rural areas decline while some others not: an overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural. Stud. 68, 135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.003

Liu, Y., Cui, J., Feng, L., and Yan, H. (2024). Does county financial marketization promote high-quality development of agricultural economy? Analysis of the mechanism of county urbanization. PLoS One 19:e0298594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298594

Liu, Y., Cui, J., Jiang, H., and Yan, H. (2023). Do county financial marketization reforms promote food total factor productivity growth?: a mechanistic analysis of the factors quality of land, labor, and capital. Front. Sustain. Food Systems. 7:1263328. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1263328

Liu, Y., Li, J., and Yang, Y. (2018). Strategic adjustment of land use policy under the economic transformation. Land Use Policy 74, 5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.005

Long, H., Tu, S., Ge, D., Li, T., and Liu, Y. (2016). The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: problems and prospects. J. Rural. Stud. 47, 392–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.011

Lopez, T., and Winkler, A. (2018). The challenge of rural financial inclusion–evidence from microfinance. Appl. Econ. 50, 1555–1577. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2017.1368990

McKinnon, R. I. (1973). Money & Capital in Economic Develop nt, Washington,D.C., The Brookings Institution.

Petry, J. (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. Econ. Soc. 49, 213–238. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913

Qin, X., Li, Y., Lu, Z., and Pan, W. (2020). What makes better village economic development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from 338 villages. Habitat Int. 106:102286. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102286

Steiner, A., and Teasdale, S. (2019). Unlocking the potential of rural social enterprise. J. Rural. Stud. 70, 144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.021

Sun, L., and Zhu, C. (2022). Impact of digital inclusive finance on rural high-quality development: evidence from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022:7939103. doi: 10.1155/2022/7939103

Tian, X., Wu, M., Ma, L., and Wang, N. (2020). Rural finance, scale management and rural industrial integration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 12, 349–365. doi: 10.1108/CAER-07-2019-0110

Tu, S., Long, H., Zhang, Y., Ge, D., and Qu, Y. (2018). Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 77, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.12.001

Xu, L., and Tan, J. (2020). Financial development, industrial structure and natural resource utilization efficiency in China. Res. Policy 66:101642. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101642

Xue, L., Weng, L., and Yu, H. (2018). Addressing policy challenges in implementing sustainable development goals through an adaptive governance approach: a view from transitional China. Sustain. Dev. 26, 150–158. doi: 10.1002/sd.1726

Yan, J. (2007). The measurement of China’s marketization process. Statistics & Decision. 23, 69–71. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-6487.2007.23.027

Yao, W., and Wang, C. (2022). Agricultural land marketization and productivity: evidence from China. J. Appl. Econ. 25, 22–36. doi: 10.1080/15140326.2021.1997045

Yaseen, A., Bryceson, K., and Mungai, A. N. (2018). Commercialization behaviour in production agriculture: the overlooked role of market orientation. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 8, 579–602. doi: 10.1108/JADEE-07-2017-0072

Zhang, S., Chen, C., Xu, S., and Xu, B. (2021). Measurement of capital allocation efficiency in emerging economies: evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 171:120954. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120954

Zhang, Z., Sun, C., and Wang, J. (2023). How can the digital economy promote the integration of rural industries—taking China as an example. Agriculture 13:2023. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13102023

Zhang, H., and Wu, D. (2022). The impact of transport infrastructure on rural industrial integration: spatial spillover effects and spatio-temporal heterogeneity. Land 11:1116. doi: 10.3390/land11071116

Zhang, R., Yuan, Y., Li, H., and Hu, X. (2022). Improving the framework for analyzing community resilience to understand rural revitalization pathways in China. J. Rural. Stud. 94, 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.06.012

Zhou, J., Chen, H., Bai, Q., Liu, L., Li, G., and Shen, Q. (2023). Can the integration of rural industries help strengthen China’s agricultural economic resilience? Agriculture 13:1813. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13091813

Zhou, Y., and Hall, J. (2019). The impact of marketization on entrepreneurship in China: recent evidence. Am. J. Entrep. 12, 31–55.

Keywords: rural industrial integration, capital marketization, system GMM model, threshold regression, China

Citation: Ding Z and Fan X (2024) Does capital marketization promote better rural industrial integration: evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1412487. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1412487

Edited by:

Sanzidur Rahman, University of Reading, United KingdomReviewed by:

Feng Ye, Jiangxi Agricultural University, ChinaMajid Ali, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2024 Ding and Fan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhao Ding, emRpbmdAc2ljYXUuZWR1LmNu

Zhao Ding

Zhao Ding Xinyi Fan

Xinyi Fan