- 1Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 2GreenUPorto/Inov4Agro, DGAOT, Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, Vila do Conde, Portugal

- 3GreenUPorto/Inov4Agro, DCeT, Universidade Aberta, Porto, Portugal

Vulnerable livelihood groups, such as the Fulanis in Guinea-Bissau, are affected by the consequences of inequality, as they lack access to healthy food, a healthy environment and adequate primary health care. Coordination between sectors can be key to building resilient food and health systems by integrating and scaling up preventive and emergency nutrition services, especially in the context of malnutrition. In 2021, a cashew-based food product was launched in Portugal in partnership with an NGO and a Portuguese food retailer. This study aims to explore the development and marketing of the product with humanitarian objectives, assessing its impact on the different stakeholders of the project. A mixed methodology was applied, combining the evaluation of consumer behavior, assessed through self-reported electronic questionnaires and in-depth interviews with the actors involved in the project. According to the retailer group stakeholders, a great opportunity for the future lies in developing new products with a humanitarian character. The results show that consumers are indeed interested in buying a product associated with a humanitarian cause, and that the product “100% Cashew Nut Butter” has a favorable consumer acceptance in terms of sensory attributes. The long-term nature of the project and the financial return were cited as strengths by all NGO stakeholders involved, but all stakeholders agreed that innovation was needed to sustain donations. Thus, this may be a cyclical process: businesses can create demand through product development, while management and consumers, in turn, drive demand. These findings can be used to improve the design of future projects that might use this as an example.

1 Introduction

Food systems gather all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructure, institutions) and activities that are related to the production, aggregation, processing, distribution, consumption, and disposal of food products, derived from agriculture, forestry or fisheries - being part of the broader economic, societal, and natural environment in which they are embedded (High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security (HLPE), 2014). This is particularly relevant, as the food system must be considered in various contexts, namely: rapid population growth, urbanization, increasing wealth, more women entering the workforce, changing consumption patterns, globalization, climate change and natural resources depletion, as well as forces such as technological change and innovation, and policy changes (Kennedy et al., 2004).

As the contemporary food system becomes more globalized and industrialized, this allows for increased efficiency in the food supply system. In turn, this reduces the cost of food to consumers and increases the availability and diversity of food, particularly for processed and packaged goods, which are often high in sugar, fats and salt, and low in important micronutrients. Despite the transitions of global food systems having enabled affordable and tasty energy-dense foods (Drewnowski, 2003, 2004; Drewnowski and Specter, 2004), they had less favorable outcomes for nutrition and health, environmental sustainability, and inclusion and equity for all (Ambikapathi et al., 2022). In fact, the market availability of energy-dense foods at low prices increases energy availability for low-income consumers by replacing other important elements of a diverse diet, such as fruits and vegetables, with these products (Krebs-Smith and Kantor, 2001). This unhealthy eating pattern enhances the risk of micronutrient deficiencies (Miller and Welch, 2013) and increases overweight and obesity (Gómez and Ricketts, 2012). A healthy diet comprises various nutritious and safe foods from several different food groups that provide dietary energy and nutrients in the amounts needed for a healthy and active life. It is based on a wide range of unprocessed or minimally processed foods, while restricting the consumption of highly processed foods and drinks; it includes whole grains, legumes, nuts, an abundance and variety of fruits and vegetables, and can include moderate amounts of eggs, dairy, poultry and fish, and small amounts of red meat [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2019]. Diets based on added sugar, oil, margarine, and refined grains are more affordable than the recommended diets based on lean meat, fish, fresh vegetables, or fruit (Darmon et al., 2004; Drewnowski, 2003, 2004; Drewnowski and Specter, 2004). This is economically logical, since cereals, added sugars, and fats, which are dry and tend to have a stable shelf life, are easier to produce, process, transport, and store than perishable meats, dairy products, or fresh produce, with high water content.

Additionally, as the contemporary food system production is becoming ever more globalized and industrialized, it also impedes small farmers, small local agents, traditional food markets and merchants selling “street food,” due to their poor performance in the value chain, such as storage, transport, distribution, and sales [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2013]. Particularly in vulnerable regions, the agricultural sector remains largely underdeveloped with respect to production both for the domestic market and for export, even though the agricultural sector lies at the center of their economies. Nutritional inequity can be linked to underproduction in agriculture, poorly resourced smallholder farmers, difficulties in applying research and development results, lack of food safety and quality assurance, high levels of food waste from farm to consumer, poor supply chain management, land tenure issues, and lack of women’s empowerment in agriculture (Cordaro, 2013).

Faced with these global challenges, there is a need to shift from the current food system toward a more sustainable one that ensures food security and nutrition for all, without compromising the economic, social, and environmental foundations for food security and nutrition for future generations [High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security (HLPE), 2014]. This requires a more holistic and coordinated approach that integrates actions taken by all stakeholders at local, national, regional, and global levels, by both public and private actors, and across multiple sectors, namely agriculture, trade, policy, health, environment, gender norms, education, transport, and infrastructure [United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2019]. In this context, the United Nations (UN) and public health experts have encouraged governments, non-governmental organizations and civil society organizations to collaborate with the private sector to address global nutrition challenges (Kraak et al., 2012). By working together, private sector companies and NGOs can achieve common goals more effectively than they could alone, build consensus on what needs to be done, pool expertise, ideas, skills, and resources, reach a wider range of the population, and reduce regulatory costs (Hawkes and Buse, 2011).

An example of this approach is the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP), an inter-governmental organization involving nine countries across three continents (Africa, Asia, and Europe): Angola, Brazil, Cape Vert, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Portugal, Sao Tome and Principe, and Timor-Leste. Altogether, the Community represents a population of more than 280 million people. Given the high priority with which the member states of the CPLP offer to coordinate efforts and cooperation for eradicating hunger and poverty in their territories, the Community approved, in 2011, the Food Security and Nutrition Strategy, with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). This strategy seeks to strengthen the governance of public policies in the territories, encourage food production to improve availability from family farming, and promote social protection by improving access to food and the livelihoods of more vulnerable groups [Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP), 2015]. The Strategy contributes to improving the coordination, coherence, and alignment of policies at different levels (local, national, regional, and global), using a multi-stakeholder and multiregional approach (Pinto, 2013). It involves actors from civil society, the private sector, and development cooperation partners such as UN specialized agencies, international financing institutions, and regional-oriented organizations [Lapão, 2016].

The food security levels vary substantially in CPLP countries, where in Guinea-Bissau, the country involved in the analysis of this research, is the most problematic country considering food security indicators. In absolute terms, in 2022, there were nearly 28.5 million undernourished (chronic hunger) people in the CPLP regions (SDG Indicator 2.1.1). This means that individual habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide, on average, the amount of dietary energy required to maintain a normal, active, and healthy life. In Guinea-Bissau, 37.9% of the population was undernourished, corresponding to 0.8 million inhabitants. Moreover, about 124,8 million CPLP people were moderately or severely food insecure, whereas 77.8% (1.6 million inhabitants) in Guinea-Bissau faced moderate or severe food insecurity (SDG Indicator 2.1.2). Additionally, more than 110.4 million people in the CPLP could not afford a healthy diet in 2021. About 1.7 million people in Guinea-Bissau, or 84.6% of the population, could not afford a healthy diet in the same year [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), and World Health Organization (WHO), 2023], meaning that most of the population cannot access the least expensive locally available foods to meet nutritional requirements [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), and World Health Organization (WHO), 2023]. Moreover, in Guinea-Bissau, 28% of children under 5 years of age are irreversibly physically and cognitively stunted (have low height-for-age) caused by chronic malnutrition during the first 1,000 days of their life, and 5% are acutely malnourished or wasted (have low weight-for-height ratio) (SDG Target 2.2) (UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, 2023).

Guinea-Bissau is one of the 44 low-income food-deficit countries currently identified by FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), and World Health Organization (WHO), 2024]. Being both in a food deficit and having a low income at the same time indicates that Guinea-Bissau lacks the resources not only to import food but also to sustain enough domestic production, even though the agricultural sector lies at the center of its economy, accounting for 40–50% of Growth Domestic Product (GDP) (Paviot et al., 2019). It is the combination of these two factors that makes Guinea-Bissau both food insecure and susceptible to domestic and external shocks, which could affect the nutritional status of vulnerable populations.

In Guinea-Bissau, the policy framework for the population’s nutrition is still evolving, with the collaboration of several actors carrying out beneficial activities, such as the Portuguese NGO helping the Fula population, with its headquarters in Lisbon, Portugal. This is an association for sustainable development that has been working for over 20 years with the Fula, in the northern region of Guinea-Bissau, whose aim is to provide humanitarian aid in a variety of areas, including health, education, child nutrition, professional training, and providing drinking water. In the socio-political-cultural context, the Fula are considered a vulnerable livelihood group, one of the least reached and politically recognized ethnic groups on the African continent. In Guinea-Bissau, the Fula live throughout the territory, especially in the interior regions (Pinto, 2009). Agricultural systems where the Fula people live are focused on a few crops - this creates inequalities and, therefore, an imbalance in the availability of essential foods for healthy nutrition (Branca et al., 2019).

Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) is the most important crop in Guinea-Bissau in terms of the country’s GDP, which is directly affected by this cash crop and its international trade, export, and price. Cashew is, therefore, not only an important agricultural product that contributes significantly to both GDP and export trade at the national level, but also an indispensable resource for the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, who represent most of the households in the country. About 40% of the country’s food consumption depends on cashew sales (Carvalho and Mendes, 2016). However, there are notable problems in exporting cashew nuts from Guinea-Bissau to other countries, related to the low level of producer organization and the lack of quality control on departure from the country, which ultimately is incompatible with the requirements of some markets, such as the European continent (Catarino et al., 2015). Although Guinea-Bissau has a competitive position in terms of raw material production and processing potential, it faces a limiting situation in terms of processing, industrial activities, transport, and marketing (Kakietek et al., 2017; Monteiro et al., 2017).

The efforts of the aforementioned NGO, its experience with the beneficiary population, and its knowledge of their needs, combined with the commitment of the leading Portuguese food retailer, to get involved in humanitarian causes (sensitive to nutrition and sustainable development) led to the development of the “100% Cashew Nut Butter” product. This partnership aimed to create a food product to sell in Portugal that could be involved with a humanitarian cause, in this case through the NGO, within the framework of the sustainable development of the Fula ethnic group. It consisted of developing a nutritious product based on cashew nuts from the African continent and processed by a Portuguese manufacturing company contracted by the food retailer. Using the raw material from Guinea-Bissau was not possible due to the lack of quality control on departure. The product carried the retailer’s private label and was sold exclusively in their stores.

The product was launched on the Portuguese market in July 2021 and remained on the retailer’s shelves for 10 months, with 28,651 units being sold. A percentage of the product’s sales (22% including value-added tax) went to the NGO, which in turn used the funds raised to invest in the construction of Centers for the Prevention of Child Malnutrition in the different villages where it operates in the northern region of Guinea-Bissau, namely in the Sibidjam Fula, Tabanane and Gikoi villages. These Centers for the Prevention of Child Malnutrition are buildings with school canteens, kitchens, support rooms for medical consultations, and anthropometric measurements for nutrition data. The money raised through the food product went directly toward building the centers, buying food supplies for breakfast offered daily in the school canteen, transporting the supplies to the villages, and training volunteers. The low levels of schooling among the child population led the NGO to seek to resolve both issues through the Centers for the Prevention of Child Malnutrition: to combat malnutrition, through continuous anthropometric screening and the daily provision of a meal before school, and to promote education, since all the centers are linked to public schools and the beneficiaries are obligatorily enrolled in them (INE, 2020).

The “100% Cashew Nut Butter” is made from roasted cashew nuts, with no other ingredients or additives. The product content of 180 g in a plastic jar is light brown. The front of the packaging shows the name of the product, the claim “Source of Protein,” the logo of the NGO partner, and the claim “Because helping tastes good!.” The nutritional declaration on the back of the food packaging in readable tabular form (Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011), declared per 100 g: 2565 kJ, 618 kcal, 48.6 g lipids, 9.6 g saturated lipids, 20.8 g carbohydrates, of which 7.7 g sugars, 3.2 g fibers, 23 g protein and 0.03 g salt. The promotional message for the product, therefore, focused on the visual identity values: purpose, nutrition, health, balance, and helping others (solidarity). The price per 100 g of “100% Cashew Nut Butter” (4.99 €) was lower than other similar private brands available on the Portuguese market (n = 6), as the mean price (€) of these competing brands was 7.86 € ± 2.41 € (data collection carried out online between March and September 2022). Through a QR code on the food packaging, it is possible to access the NGO website, where consumers can find information about the projects where the donations will be used.

This study aims to explore the development and marketing of the product with humanitarian objectives -“100% Cashew Nut Butter” - assessing its impact on the different stakeholders of the project: the retail sector and the NGO, as well as the impact on the perception and attitudes of Portuguese consumers. Finally, this study intends to identify the main success factors, future trends and needs, and the potential for developing these partnerships.

2 Methods

A mixed methodology was applied, combining the evaluation of consumer behavior, assessed through self-reported measures questionnaires and in-depth interviews with the actors involved in the project. The combined use of these procedures in consumer research allows for an apprehension of the phenomena and the object of study from different perspectives, thus inter-relating the findings (Guerrero and Xicola, 2018). The aim is to increase the validity of the results obtained, considering different points of view, in which various data collection techniques are used (Mesías and Escribano, 2018). All participants followed an informed consent procedure before participation, previously approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Porto, with reference number CE2022/p22.

2.1 Interviews

Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were the method of choice to obtain in-depth descriptions of the opinions, perspectives and motivations associated with the interventions carried out by the actors of the retail group. The participants were those who were directly involved in this project, namely those who interacted with the NGO for the conceptualization of the interaction, and the management of the product development and launch in the Portuguese market. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was developed considering the following dimensions: (i) perceptions of the strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities of the project; and (ii) evaluation of the partnership between the NGO and the food retailer group. The retailer’s group actors were interviewed individually at the company’s offices in Lisbon, Portugal, in March 2022.

To assess the perception of the project by NGO actors already present in Guinea-Bissau, a web interview was conducted with them in April 2022. For this purpose, an interview guide was developed with the following dimensions: (i) motivations for involvement; and (ii) assessment of the project’s impact.

All the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and then validated by the participants. The interviews were analyzed using a process of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The themes were identified inductively, and content was analyzed in terms of both manifest and latent themes, an analytical process involving a progression from description to interpretation of data (Joffe and Yardley, 2004). Considering the transcripts of the interviews, an extensive process of data coding and identification of themes, consistencies, and discrepancies between themes, was undertaken and explored to provide an in-depth understanding of the texts. Once groups of themes were created, constant comparison was used to ensure the internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity of the categories (Patton, 1990). To illustrate the analysis, direct quotes from the participants were transcribed and translated into English, using a back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1970), to serve as a description of the theme under study.

2.2 Survey

Participants were selected from the national consumer database of the company’s retailer group, representing a sample of approximately 500 individuals. Before completing the questionnaire, participants were informed of the purpose of the study and the confidentiality and anonymity of the data collected. A structured self-reported electronic questionnaire was applied using the Google forms® platform, and disclosure was made by the retailer group. An exclusion question filtered out only those who had consumed the “100% Cashew Nut Butter.” In the first part of the questionnaire, the frequency and the time of day/meal the product is consumed were assessed using a one-choice and multiple-choice response list, respectively. In the second part, participants indicated how they were encouraged to buy “100% Cashew Nut Butter” for the first time with multiple-choice options: communication by retailer (site, newsletters, magazine), previous knowledge of the NGO project, social networks, friends/family, television, and other (open response). Participants were asked to choose the closest attitude they had after buying the product with a one-choice option: “I learned about the NGO work through the QR code in the product,” “I followed the NGO on social networks,” “I donated to the NGO,” “I supported other humanitarian causes,” “I did not support this or any other humanitarian cause other than by purchasing” and “I was not aware that this product was associated with a humanitarian cause.” To the participants who said they would buy the product again, they were asked to identify the reasons that might influence them to buy “100% Cashew Nut Butter,” again with multiple-choice options: “I like the taste,” “It is healthy,” “I like the texture,” “I feel identified with the NGO project,” and other (open response). The influence of specific factors on the purchase decision was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very negative influence to 5 = very positive influence) for the factors: healthy food, packaging, product communication, supporting humanitarian causes, trying new flavors, trying new textures, environmental sustainability, supporting farmers in developing countries. In the third part of the survey, consumers rated their acceptance of the following attributes of the product: appearance, texture, and flavor on a five-point hedonic scale (1 = very unpleasant to 5 = very pleasant). At the end of the questionnaire, the participants provided socio-demographic information, namely: age, gender, level of education, place of residence, and subjective involvement in a humanitarian cause (not at all involved vs. quite involved). Data was collected over 2 weeks, from the 18th of May to the 1st of June 2022.

Descriptive statistics were applied to characterize the participants and their reported behaviors, using frequency tables to systematize the results. Statistical tests were performed, using the IBM® SPSS Statistics software (version 28.0.1.0), to evaluate if there were significant differences between the two groups of gender and level of education (Binomial test), and between the different groups of age and place of residence (Chi-square test). The influence of the sociodemographic characteristics on the multiple-choice questions was tested with a Chi-square test. A Wilcoxon test was also used to compare the influence of different factors on purchase decisions. The criterion of significance of the tests was p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

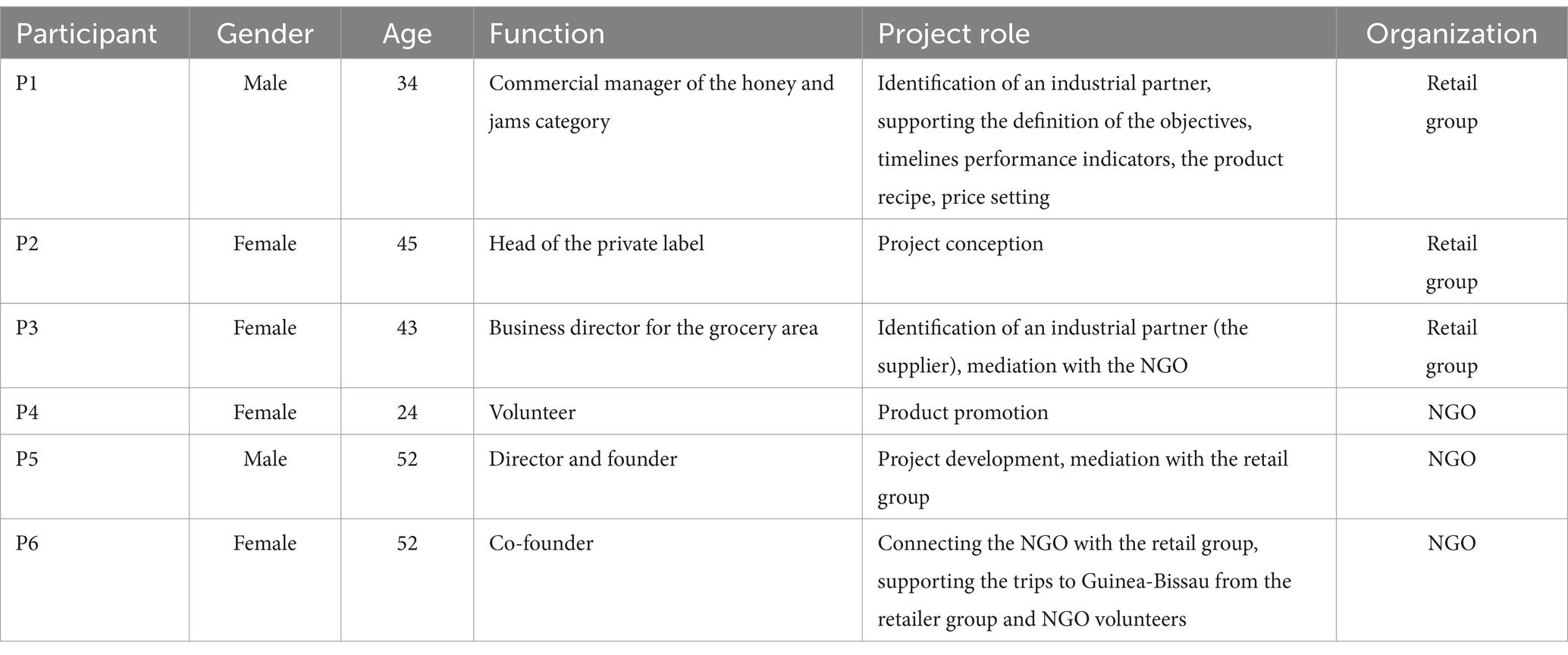

Three participants from the retail group were interviewed, hailing from different departments in the company and having distinct roles in the project (Table 1). In the same way, three participants with distinct roles in the NGO were interviewed (Table 1). Actors on both sides were chosen as they were the only individuals involved in all project stages, even though they had different roles.

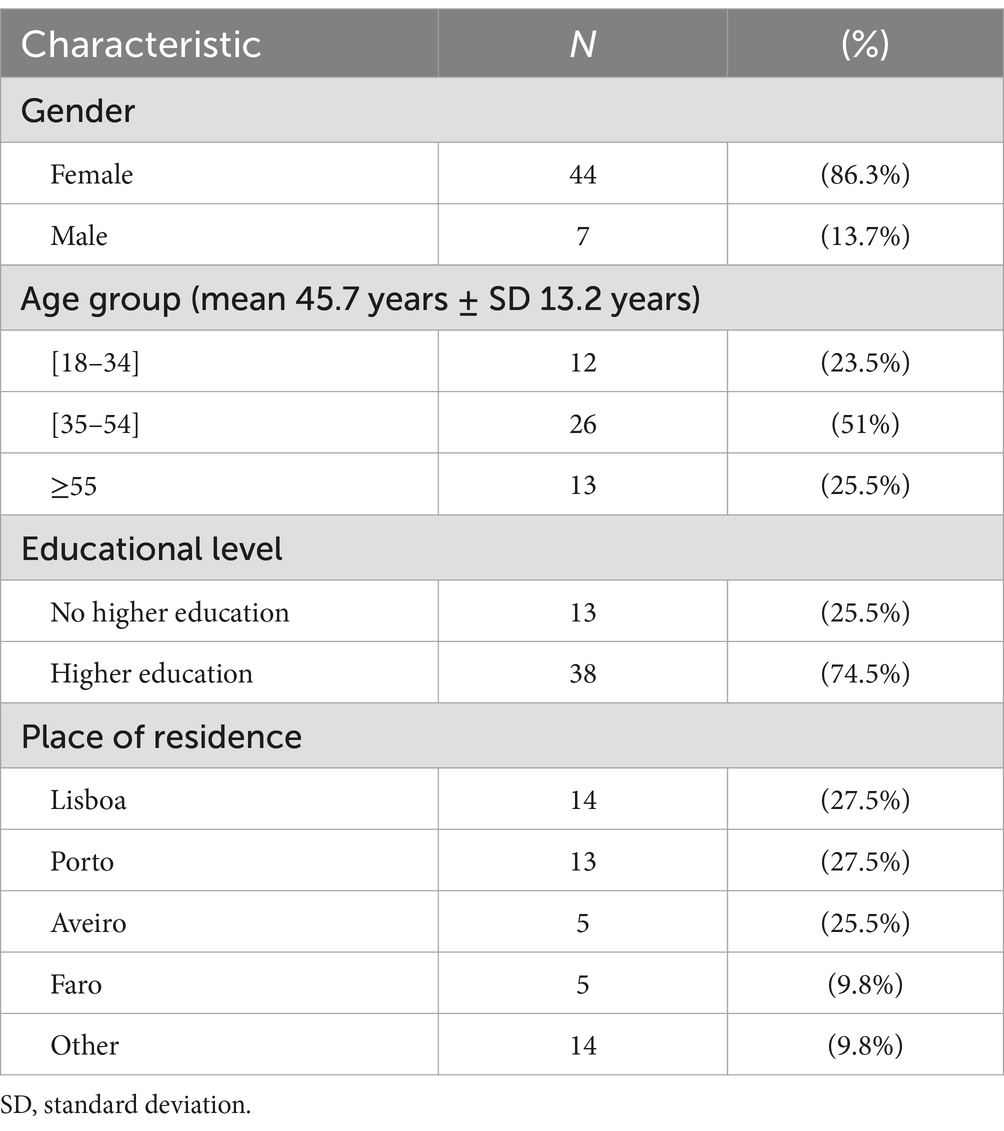

About 51 participants responded to the full questionnaire and said they had bought “100% Cashew Nut Butter.” Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characterization of these participants. The participants were majority female (86.3%), with a mean age of 45.7 ± 13.2 years old (ranging between 20 and 77 years old), spread across three age groups, with 74.5% having attained a higher educational level. The majority lived in urban and coastal areas in Portugal.

3.2 Interviews

According to the retail group actors who participated in the interviews, the purpose of the product “100% Cashew Nut Butter” was to offer a nutritious food product to Portuguese consumers that also benefited the Fula population in Guinea-Bissau, namely by helping to combat child malnutrition. Different linked factors contributed to achieving these goals, demanding careful collaboration and individual ongoing commitment (“I think the strong point was motivation because we knew that this product might never receive several big sales and large volumes, so it ends up giving a much bigger return in emotional terms,” P1), particularly when tangible and positive outcomes can be observed: “Obviously, this project goes far beyond just commercial motivation (…), especially after having been in Guinea (I had this opportunity in December last year) and seeing the real impact that this has on those children,” P3. Another important factor for achieving these goals is that the corporate values and goals of the company align with the NGO’s aims, as when there is a strong alignment (“From the beginning this project it was strategic for us because our concern about healthy eating is very strong,” P2), the company is more likely to remain committed to the project over the long term. Moreover, supporting humanitarian causes can improve a company’s image and reputation, and create a strong emotional connection with customers, leading to increased loyalty, repeat business, and access to new markets (commercial advantage): “…in the business world, it has been realized that without people and the planet there is no business, and so the companies that have value today are those that work around these sustainable development objectives,” P2. Consumers often appreciate and favor businesses that demonstrate social responsibility, particularly if the product is tasty (see section 3.3.), as reported by P2: “The product itself was very well received by consumers, by the company, by everybody.”

The retail actors also reported some project weaknesses related to: (i) the raw material (the cashew did not come from Guinea-Bissau, as was the original idea of the project, limiting the contribution of the community producers); (ii) the product development process (the supplier did not have the product recipe developed and did not have studies of the product’s shelf-life with this particular ingredient), leading to the short shelf-life (3 months) of the “100% Cashew Nut Butter,” and (iii) other commercial constraints, as “… the “100% Cashew Nut Butter” is a product with low turnover in the shops” (P1). These factors contributed to the emergence of another weakness, product waste: “We bought a lot of the product to fill the stores and to donate more money in an initial phase, but we had a very large volume of the purchase at the beginning and now we have extra stock (…) which is not good, after all, we are buying to help a cause, but we also must fight food waste,” P1. Shelf-life refers to the period during which a product remains safe to consume and retains its intended quality. Without proper shelf-life studies, businesses may struggle to determine the optimal conditions for the storage and transportation of their products. Quality attributes such as taste, texture, color, and nutritional content might be compromised over time, leading to customer dissatisfaction. This could threaten the launch of other food products, especially if suppliers are unfamiliar with certain ingredients or recipes. The retail group actors interviewed also reported another risk to the success of the “100% Cashew Nut Butter,” wherein it was regarded as a discrete or episodic occurrence, instead of a continuous one: “The big threat of this project is to be treated as a project and not a way of life because a project starts and ends, and this cannot end,” P2.

Nevertheless, participants perceived the experience gathered with the “100% Cashew Nut Butter” as an advantage to enhance the diversification of other food product launches for the same purpose: “There is a Business Case now that can be replicated, and this is a great opportunity,” P2. Thus, to develop successful products, it is necessary to run an effective product development process, combining both technical knowledge and market information: “From the beginning, we were willing to give this product a kind of “little brother,” a new spread that will have a lower price and will sell more after it manages to have a greater rotation and therefore, a greater donation donated to NGO.” Participants also considered further opportunities that directly involve the local community in the planning and implementation of the project: “To be able to gather conditions, provide training (to producers) so that one day the raw material that is used in these products is really from Guinea-Bissau, and that is from these villages (...) I think it is still an opportunity for improvement,” P3. Community engagement fosters a sense of ownership, ensures that the project addresses the actual needs of the community, and is on track for sustainability. In this context, they also reinforced that the company’s financial support is crucial for the sustainability of NGO aims. For this purpose, the company should not only provide initial funding but also consider long-term financial commitments and explore innovative funding models: “We consider having here a regular source of donation that can enable these investments that we are making in the villages, not only through the construction of the centers but also providing the breakfasts, because what can never happen is: we give lunch in one school year and then we cannot guarantee that in the second school year, we will continue to,” P3. According to the retail actors, companies can provide sustainability of the NGO projects, because building strong partnerships can bring in additional resources and expertise: “Today there is also a greater openness of the NGO for the companies, because if NGO did only this part, without understanding the need for financial sustainability of the project, they would kill the projects one day or another,” P2.

The NGO actors interviewed also recognized that this partnership was crucial to the successful implementation of healthy eating practices in the Fula community, and reenforced their aims for the continuity of this partnership: “100% Cashew Nut Butter,” and other future products could create a platform for launching new projects, new volunteers, of prolonging our work on the ground, of keeping professionals on the ground (…) at least on the NGO side, the desire is for the long term and to the extent that we can see concrete things and needs we will be trying to meet,” P5. According to them, establishing a long-term relationship with the retail group allows this NGO to deepen their impact on the communities they serve. Over time, they can develop a more profound understanding of the issues, implement comprehensive strategies, and adapt their approaches based on the evolving needs of the community: “...at least on the NGO side, the desire is for the long term,” P5; “… If you have a project only for the moment,...it ends. (...) it is something that must continue over time, and I think this project has this quality,” P6. Long-term partnerships foster strong relationships between NGOs and the private company. This not only enhances trust but also allows for open communication, collaboration, and shared decision-making: “The experience also creates trust, where other institutions support us by the fact that they know where we are,” P5; as well as providing stability and predictability in funding. Having a consistent source of financial support allows NGOs to plan and execute their programs and projects with greater confidence, knowing that they have the necessary resources over an extended period. At this point, they prospected the following plans: technically empower the producers to use the raw material from Guinea-Bissau as an ingredient in the “100% Cashew Nut Butter” and help the development and the launch of other food products with local ingredients.

Donations were used to provide children with breakfast at school and the construction of healthcare facilities: “In less than one year, the desire to see things work came about in the very first months, and we saw that the nutritional impact ends up also bringing fantastic consequences about the cognitive development of the children,” P5. Additionally, when supporting the NGO, consumers found a deep sense of satisfaction and fulfillment in contributing to positive social change, making a difference in the world, as was mentioned by P6: “It has an impact on Portuguese society, it makes people think about other peoples’ needs and feel able to make a gesture as small as buying a nut butter that will then make a difference in the lives of others (…) because they see things happening, the water hole, a Center for the Prevention of Child Malnutrition has started, the other center is already being built.” Moreover, the NGO actors believed that focusing on community development plays a crucial role in addressing the specific needs and challenges faced by local populations: “It meets the various needs, physiological and physical needs of the community itself, of insufficient food,” P4; “… the truth is that we do not sell the product, we sell the solution (…) I think this project is a solution to meet the objectives that we have on the ground,” P5. These actors find a deep sense of purpose in their roles, considering that their work directly contributes to improving the Fula people’s lives, as “The reasons have to be focused on the beneficiaries,” P5.

3.3 Questionnaire

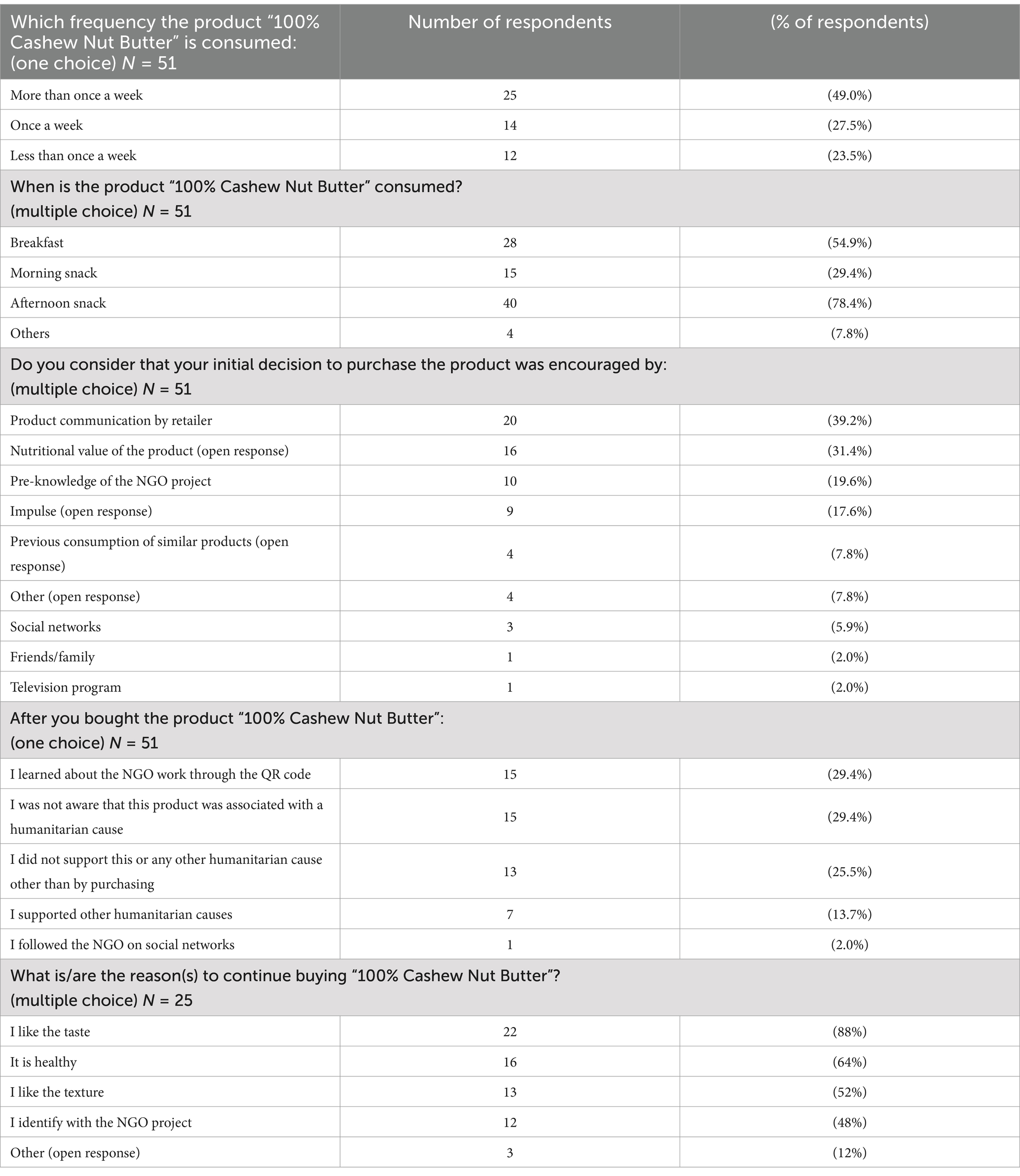

According to the participants in the consumer questionnaire, the frequency of consumption of “100% Cashew Nut Butter” was mainly distributed between more than once a week (49%) and once a week (27.5%) (Table 3). The product was most consumed during the afternoon snack (78.4% of respondents), followed by breakfast (54.9% of respondents) and morning snack (29.4% of respondents) (Table 3). None of the sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education level and place of residence) significantly influenced the time of day the product was consumed.

Table 3. Distribution of consumer questionnaire respondents (N and %) by “100% Cashew Nut Butter” frequency of consumption, time of day consumed, reasons for first and repeat purchases and post-purchase attitudes.

The most frequently cited reasons that encouraged the purchase of “100% Cashew Nut Butter” were product communication by the retailer (website, magazine, newsletters) (39.2% of respondents), the nutritional value of the product (open response) (31.4% of respondents). About 19.6% of respondents also confirmed that the first purchase was encouraged by prior knowledge of the NGO project (Table 3). When forced (one-choice) to identify the closest attitude felt after buying the product, some consumers said they wanted to know more about the NGO work (29.4%), others said they had not even realized that this product was associated with a humanitarian cause (29.4%), while others still did not support this or any other humanitarian cause other than by buying the product (25.5%) (Table 3).

Those who said they would continue to buy the product (n = 25) were motivated by the taste of the product (88% of respondents), the fact that it is a healthy product (64% of respondents), the texture of the product (52% of respondents) and the feeling of identification with the NGO project (48% of respondents) (Table 3).

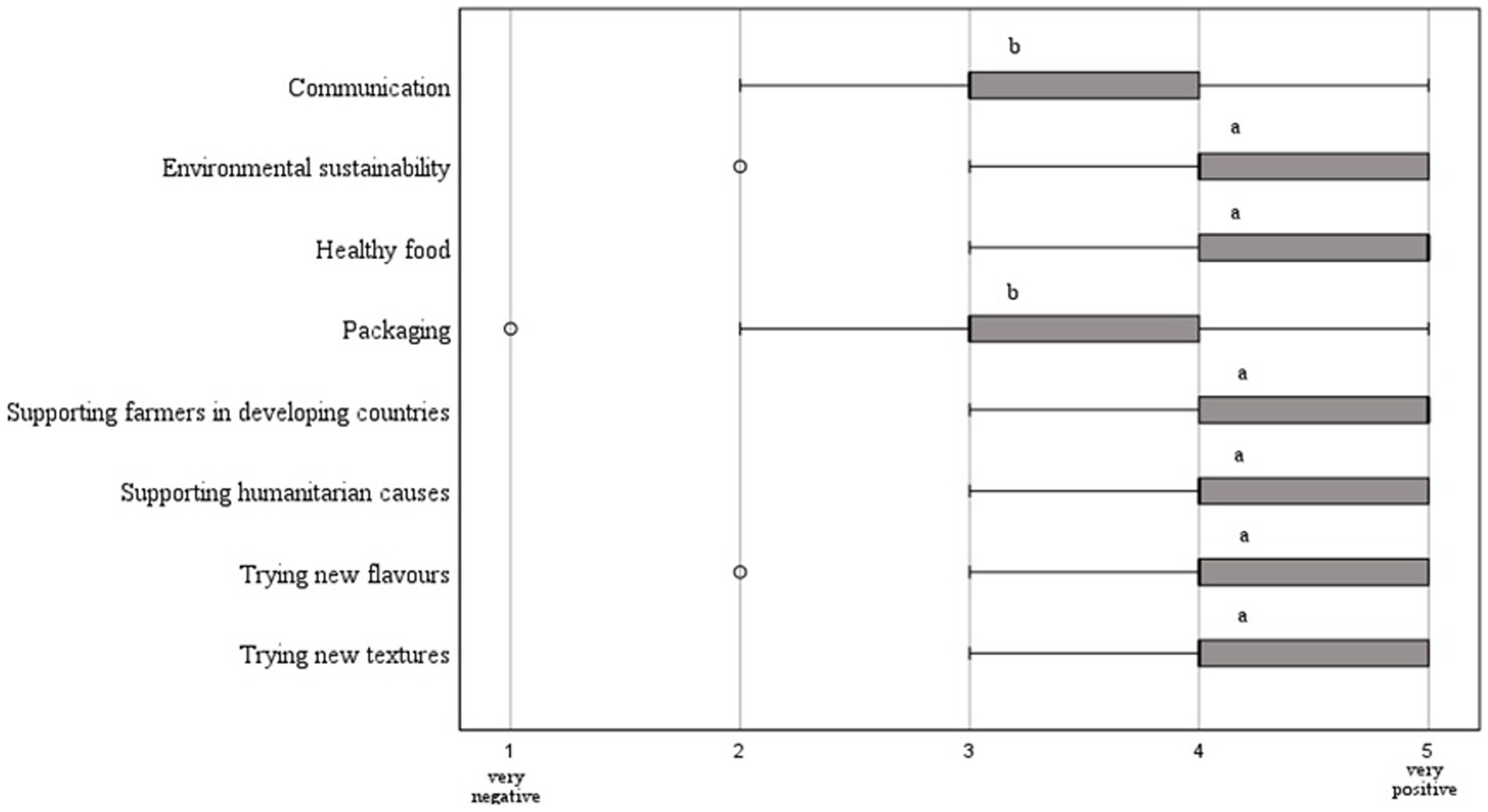

Respondents, when asked about the influence of different factors on the purchase decision of “100% Cashew Nut Butter,” highlighted environmental sustainability, healthy food, supporting a humanitarian cause and farmers in developing countries, and trying new textures and flavors (Figure 1). The different letters in Figure 1 represent the two significantly different groups identified by the Wilcoxon test: (a) aspects such as environmental sustainability, healthy food, supporting a humanitarian cause, and farmers in developing countries and trying new textures and flavors with higher influence on the purchase decision, and (b) aspects such as packaging and product communication with lower influence on consumer’s purchase decision. Thus, both packaging and communication were aspects that could be improved in new campaigns.

Figure 1. Influence of different aspects on the purchase of “100% Cashew Nut Butter” on a scale from 1 - very negative to 5 - very positive. The boxplots show the results from the minimum to maximum values and the box from Q1 to Q3. The different letters represent significantly different groups of aspects according to the Wilcoxon test.

In fact, “100% Cashew Nut Butter” was a very well-accepted product regarding its sensory attributes. On a scale of 1 = very unpleasant to 5 = very pleasant, the average rating was above 4.5 for all attributes (appearance, flavor, and texture) with an overall acceptance rating of 4.6 out of 5.

4 Discussion

The “100% Cashew Nut Butter” product brings together food retailers, NGOs, and consumers. This offered an approach to engage different stakeholders in a discussion to launch food products that are nutritious, tasty, and with humanitarian concerns simultaneously. Nevertheless, according to our results, depending on the role played by the actor, different goals to be achieved were highlighted.

The purpose of the food retail group in launching “100% Cashew Nut Butter” was to offer nutritious food to consumers (due to its high protein content) and to support the vulnerable Fula people by contributing to the fight against child malnutrition (a humanitarian cause) through an NGO. They play a key role in ensuring that safe and healthy food is accessible and affordable (SDGs 2 and 3), with the concern of responsible consumption (SDG 12). In addition, the linkage between the different actors is based on strengthening partnerships for the goals (SDG 17) (Djekic et al., 2021). To this end, 22% of the product’s sales go to the NGO, so the money is directly invested in the Centers for the Prevention of Child Malnutrition, where breakfast is offered to children in schools, to combat malnutrition. In addition, the NGO has established a local presence in the regions where they work with the Fula population in Guinea-Bissau. This local presence allows them to understand the local context and collaborate with the communities. A similar strategy was used with refugee children in Lebanon through a community-based school nutrition intervention and had a positive impact when assessing dietary diversity, hemoglobin levels, and children’s school attendance (Jamaluddine et al., 2020). Providing school breakfasts was associated with improved attention in children, and participation in school breakfast programs has been shown to improve school attendance, leading to better cognitive outcomes (Powell et al., 1998; Omwami et al., 2011).

This partnership also has commercial advantages for the food retailer company: launching a tasty and nutritious product with a humanitarian purpose enhances a company’s reputation and public image (Webb and Mohr, 1998; Luo and Bhattacharya, 2006; Lev et al., 2010). This is particularly salient as the product carries their private label and is sold exclusively in their stores. Companies that align profits with societal impact create positive social and environmental change, which drives long-term competitive advantage (Alberti and Varon Garrido, 2017). At the same time, the presence of the NGO in the development of the product was an important part of this, as it allowed those involved in the company to get to know the project and get involved with the cause. Likewise, the fact that the NGO’s name is linked to the product is a way of bringing the consumer closer to the beneficiaries, as well as clarifying the use of the donations (the product label contains a QR Code that leads to the NGO’s website, where further information is displayed).

Finally, the results of the questionnaire show that consumers buy this product for its nutritious and tasty attributes and for its humanitarian association. Consumers are increasingly demanding both tasty and convenient foods, due to changes in their habits and lifestyles, and they are more aware of health and well-being, which allows them to focus on nutritious and safe food products, especially products that contain natural ingredients and are free of additives (Cunha et al., 2018). The “100% Cashew Nut Butter” was a very well-accepted product in terms of sensory attributes (appearance, flavor, and texture) with an almost maximum overall rating. This is particularly relevant for those who repeat the purchase, whereas taste was identified as the main reason for buying the product again. Consumers show interest in a product that supports a humanitarian cause if it does not compromise the immediate aspects of the food consumption decision, such as taste, and the promise that the product brings healthy benefits to the individual or their family (Drewnowski and Almiron-Roig, 2010). Purchasing products linked to humanitarian projects provides a tangible and direct way for individuals to contribute to meaningful causes, making them feel that their choices matter (Kong et al., 2002). As recommended by Kong et al. (2002), the real motivation behind strategic and proactive partnerships between companies and NGOs is to find ways to offer consumers the opportunity to consume differently. Furthermore, this is a cyclical process: companies can create demand through product development and management and consumers can drive demand. Companies that engage in social responsibility initiatives often build trust and loyalty among consumers. When consumers perceive a brand as genuinely committed to making a positive impact, they are more likely to support it by purchasing its products (Ellen et al., 2000; Kolk et al., 2008; Dahan et al., 2010).

This study is faced with some limitations. The limited number of interviews was justified by the reduced number of actors in the retail group and in the NGO involved in this project. Another major limitation was the low response rate to the product’s consumer questionnaire, with only 51 respondents out of the 500 to whom the questionnaire was sent. This may be explained by the low compliance of volunteer respondents, as well as by the fact that the e-mail address registered on the retail chain’s loyalty card may not correspond to the person who bought the product, since the same card can be used by different members of the household, but there is only one person for correspondence via e-mail per card. Undoubtedly, there is a potential non-response bias in the study, which could be avoided if the respondents were recruited in a more personalized way or if a pilot test of the questionnaire was carried out precisely to identify the risk of low adherence beforehand and restructure the questionnaire design. However, for the scope of the questions proposed, the sample that recorded the answers seemed to represent the product’s consumers well.

5 Conclusion

Companies increasingly play a positive societal force, supporting humanitarian causes that follow their corporate values. This approach helps to enhance the company’s reputation, portraying it as compassionate and community-focused, and an increasingly consumer-preference branded company. Regarding the food sector, this study argues that at least three factors assist in achieving these goals: (i) the product that supports the humanitarian cause should provide relevant benefits to the consumer (e.g., tasty, convenient, and nutritious food); (ii) the humanitarian project should reflect the consumer values, in the sense that they fell that their purchase contributes to positive societal change; (iii) the selection of partners should facilitate mutual understanding and trust between parties, which are the key to long-lasting and productive partnerships. In the present study, the retail company leverages its unique resources, such that, combined with the specialist expertise of the NGO, it contributes to combatting malnutrition within the vulnerable Fula population in Guinea-Bissau as the consumers accepted the launched product well.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Porto, with reference number CE2022/p22. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SCF: Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. APM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by national funds from the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through projects UIDB/05748/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05748/2020) and UIDP/05748/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/05748/2020) (GreenUPorto). The funding Institutions had no role in defining the research protocol, fieldwork, or even manuscript elaboration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the retailer company group for its support in recruiting the participants for the questionnaire and the interviews. The authors also thank the NGO for cooperating in the interviews.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alberti, F. G., and Varon Garrido, M. A. (2017). Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. J. Bus. Strategy 38, 3–13. doi: 10.1108/JBS-12-2015-0124

Ambikapathi, R., Schneider, K. R., Davis, B., Herrero, M., Winters, P., and Fanzo, J. C. (2022). Global food systems transitions have enabled affordable diets but had less favourable outcomes for nutrition, environmental health, inclusion and equity. Nat. Food 3, 764–779. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00588-7

Branca, F., Lartey, A., Oenema, S., Aguayo, V., Stordalen, G. A., Richardson, R., et al. (2019). Transforming the food system to fight non-communicable diseases. BMJ 364:l296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l296

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Carvalho, B., and Mendes, H. (2016). Cashew chain value in Guiné-Bissau: challenges and contributions for food security: a case study for Guiné-Bissau. Int J Food Syst. Dyn. 7, 1–13. doi: 10.18461/ijfsd.v7i1.711

Catarino, L., Menezes, Y., and Sardinha, R. (2015). Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop. Sci. Agric. 72, 459–467. doi: 10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0369

Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP) (2015). CPLP food and nutrition security strategy: Framework and governance bodies. Lisbon: CPLP.

Cordaro, J.B. (2013). New business models to help eliminate food and nutrition insecurity: a roadmap for exploration. Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome.

Cunha, L. M., Cabral, D., Moura, A. P., and de Almeida, M. D. V. (2018). Application of the food choice questionnaire across cultures: systematic review of cross-cultural and single country studies. Food Qual. Prefer. 64, 21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.10.007

Dahan, N. M., Doh, J. P., Oetzel, J., and Yaziji, M. (2010). Corporate-NGO collaboration: co-creating new business models for developing markets. Long Range Plan. 43, 326–342. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.11.003

Darmon, N., Briend, A., and Drewnowski, A. (2004). Energy-dense diets are associated with lower diet costs: a community study of French adults. Public Health Nutr. 7, 21–27. doi: 10.1079/phn2003512

Djekic, I., Batlle-Bayer, L., Bala, A., Fullana-i-Palmer, P., and Jambrak, A. R. (2021). Role of the food supply chain stakeholders in achieving UN SDGs. Sustain. For. 13:9095. doi: 10.3390/su13169095

Drewnowski, A. (2003). Fat and sugar: an economic analysis. J. Nutr. 133, 838S–840S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.838S

Drewnowski, A. (2004). Obesity and the food environment: dietary energy density and diet costs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 27, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011

Drewnowski, A., and Almiron-Roig, E. (2010). “Human perceptions and preferences for fat-rich foods” in the Oxford handbook of food psychology. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Drewnowski, A., and Specter, S. E. (2004). Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6

Ellen, P. S., Mohr, L. A., and Webb, D. J. (2000). Charitable programs and the retailer: do they mix? J. Retail. 76, 393–406. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00032-4

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2013). The state of food and agriculture 2013: food systems for better nutrition. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i3300e/i3300e.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2024].

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2019). Sustainable healthy diets – Guiding principles. Available at: https://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/en/c/1329630/. Accessed November 13, 2024

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), and World Health Organization (WHO) (2023). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023: urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world-2023. Accessed November 13, 2024.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), and World Health Organization (WHO) (2024). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2024 – financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Available at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/06e0ef30-24e0-4c37-887a-8caf5a641616/content. Accessed November 13, 2024.

Gómez, M. I., and Ricketts, K. D. (2012). “Food value chains and policies influencing nutritional outcomes” in the state of food and agriculture 2013: Food systems for better nutrition. Rome: FAO.

Guerrero, L., and Xicola, J. (2018). “New approaches to focus groups” in Methods in consumer research. eds. G. Ares and P. Varela, vol. 1 (Sawston, CA, USA: Woodhead publishing), 49–77.

Hawkes, C., and Buse, K. (2011). Public health sector and food industry interaction: it’s time to clarify the term ‘partnership’ and be honest about underlying interests. Eur. J. Pub. Health 21, 400–401. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr077

High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security (HLPE) (2014). “Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems” in A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security (Rome: HLPE).

INE (2020). Multiple Indicator cluster survey (MICS6) 2018-2019, final report. Bissau, Guinea-Bissau: Ministry Of economy and finance and general Directorate of Planning/National Institute of statistics (INE). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/guineabissau/media/1106/file/Guinea%20Bissau%202018-19%20MICS6.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2024.

Jamaluddine, Z., Choufani, J., Masterson, A. R., Hoteit, R., Sahyoun, N. R., and Ghattas, H. (2020). A community-based school nutrition intervention improves diet diversity and school attendance in Palestinian refugee schoolchildren in Lebanon. Curr Dev Nutr. 4:nzaa164. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzaa164

Joffe, H., and Yardley, L. (2004). “Content and thematic analysis” in Research methods for clinical and Health Psychology. eds. D. F. Marks and L. Yardley (London, England: Sage), 56–68.

Kakietek, J., Castro Henriques, A., Schult, L., Mehta, M., Dayton, J. E., Akuoku, J. K., et al. (2017). Scaling up nutrition in Guinea-Bissau: What will it cost? Washington, DC: World Bank.

Kennedy, G., Nantel, G., and Shetty, P. (2004). Globalization of food systems in developing countries: impact on food security and nutrition. FAO Food Nutr. Pap. 83, 1–300

Kolk, A., van Tulder, R., and Kostwinder, E. (2008). Business and partnerships for development. Eur. Manag. J. 26, 262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2008.01.007

Kong, N., Salzmann, O., Steger, U., and Ionescu-Somers, A. (2002). Moving business/industry towards sustainable consumption: the role of NGOs. Eur. Manag. J. 20, 109–127. doi: 10.1016/S0263-2373(02)00022-1

Kraak, V. I., Harrigan, P. B., Lawrence, M., Harrison, P. J., Jackson, M. A., and Swinburn, B. (2012). Balancing the benefits and risks of public-private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 15, 503–517. doi: 10.1017/s1368980011002060

Krebs-Smith, S. M., and Kantor, L. S. (2001). Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables daily: understanding the complexities. J. Nutr. 131, 487S–501S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.487S

Lapão, M. (2016). The functional power of the CPLP in the framework of development cooperation in food security and nutrition (FSN). Biomed Biopharma Res. 13, 9–19. doi: 10.19277/bbr.13.1.125

Lev, B., Petrovits, C., and Radhakrishnan, S. (2010). Is doing good good for you? How corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strateg. Manage. J. 31, 182–200. doi: 10.1002/smj.810

Luo, X., and Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 70, 1–18. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.001

Matsungo, T. M., Kruger, H. S., Faber, M., Rothman, M., and Smuts, C. M. (2017). The prevalence and factors associated with stunting among infants aged 6 months in a peri-urban south African community. Public Health Nutr. 20, 3209–3218. doi: 10.1017/s1368980017002087

Mesías, F. J., and Escribano, M. (2018). “Projective techniques” in Methods in consumer research. eds. G. Ares and P. Varela, vol. 1 (Duxford (UK): Woodhead publishing), 79–102.

Miller, D. D., and Welch, R. M. (2013). Food system strategies for preventing micronutrient malnutrition. Food Policy 42, 115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.06.008

Monteiro, F., Catarino, L., Batista, D., Indjai, B., Duarte, M. C., and Romeiras, M. M. (2017). Cashew as a high agricultural commodity in West Africa: insights towards sustainable production in Guinea-Bissau. Sustain. For. 9:1666. doi: 10.3390/su9091666

Omwami, E., Neumann, C., and Bwibo, N. (2011). Effects of a school feeding intervention on school attendance rates among elementary schoolchildren in rural Kenya. Nutrition 27, 188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.01.009

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Paviot, M. C., Bresnyan, E. W., Grosclaude, M., Ba, A., Diaz, A., and Mishu, S. (2019). Guinea Bissau: Unlocking diversification to unleash agriculture growth. Washington, D.C., United States: World Bank Report.

Pinto, P. (2009). Tradição e Modernidade na Guiné-Bissau: Uma Perspeciva Interpretativa do Subdesenvolvimento. Porto, Portugal: Universidade do Porto.

Pinto, J. N. (2013). Manual segurança alimentar e nutricional. Programa de formação avançada para ANEs. UE-PAANE - Programa de Apoio Aos Actores Não Estatais “NôPintcha Pa Dizinvolvimentu”.

Powell, C. A., Walker, S. P., Chang, S. M., and Grantham-McGregor, S. M. (1998). Nutrition and education: a randomized trial of the effects of breakfast in rural primary school children. Am J Clinical Nutr. 68, 873–879. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.873

UNICEF, WHO, World Bank. (2023). UNICEF-WHO-World Bank: joint child malnutrition estimates - levels and trends (2023 edition). Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/jme-report-2023. Accessed November 13, 2024.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2019). Collaborative framework for food systems transformation: A multi-stakeholder pathway for sustainable food systems. Nairobi: UNEP.

Keywords: product development, 100% Cashew Nut Butter, malnutrition, food system, Guinea-Bissau

Citation: Lucca GL, Caldas Fonseca S and Moura AP (2024) A food product development project with humanitarian character: an exploratory study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1394717. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1394717

Edited by:

Masoud Yazdanpanah, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Margherita Masi, University of Bologna, ItalyEsi Komeley Colecraft, University of Ghana, Ghana

Copyright © 2024 Lucca, Caldas Fonseca and Moura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ana Pinto Moura, YXBtb3VyYUB1YWIucHQ=

Gabriela Loewe Lucca

Gabriela Loewe Lucca Susana Caldas Fonseca

Susana Caldas Fonseca Ana Pinto Moura

Ana Pinto Moura