- National Research Council, Research Institute on Sustainable Economic Growth (CNR-IRCRES), Turin, Italy

The complex value of school meals for children and families is well documented. In Italy, school cafeterias have been an instrument of social policy since the end of the Second World War. Thereafter, school cafeterias have acquired several functions in the areas of children's health and wellbeing, education, social inclusion, support to local and quality agriculture, and environmental sustainability. In particular, the goal of a nutritious and balanced diet has been emphasized in recent decades, since malnutrition and food insecurity have been increasing in Italian society. During the pandemic, Italy was the first European country to implement a nationwide lockdown and one of the high-income countries where schools closed for the longest period. In this work, we use in-depth interviews with representatives of the school catering service, both from the major catering companies and the biggest municipalities, to analyze what happened in the management of the Italian school catering service during the pandemic crisis. In addition, a review of public recommendations issued during the pandemic has made it possible to analyze their compliance with the state guidelines for school catering and food education. The results highlight how the system reacted extremely slowly to the crisis and how the measures taken led to a deterioration of the value that has always been attributed to state school cafeterias, especially in terms of children's food security and environmental sustainability.

Introduction

The value of school meals

Extensive literature has shown that school meals play an important role in addressing major food challenges—such as eradication of hunger [Tikkanen and Urho, 2009; Jomaa et al., 2011; Robert and Weaver-Hightower, 2011; World Food Program (WFP), 2013, 2015; De Schutter, 2014; Kleine and Brightwell, 2015; World Food Programme (WFP), 2020a], reduction of obesity and other food-related diseases [Gleason and Suitor, 2003; Pyle et al., 2006; Greenhalgh et al., 2007; Harper and Wells, 2007; Kristjansson et al., 2007; Jaime and Lock, 2009; Pike and Colquhoun, 2009; Raulio et al., 2010; Capacci et al., 2012; Ashe and Sonnino, 2013; Chriqui et al., 2014; Chang and Jung, 2017; United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition (UNSCN), 2017; Baltag et al., 2022], development of local economies, ecological sustainability and ethics of food systems [Morgan, 2008; Morgan and Sonnino, 2008; Sumberg and Sabates-Wheeler, 2011; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2015; Swensson, 2019; Swensson and Tartanac, 2020], and education of children on food-related issues (Winne, 2005; Morgan and Sonnino, 2006; Harper and Wells, 2007; Harper et al., 2008; Weaver-Hightower, 2011; Benn and Carlsson, 2014; Rice and Rud, 2018; Lombardi and Costantino, 2020)—and bring about a mix of social, economic, and environmental outcomes at the same time (McCrudden, 2004; Di Chiro, 2008; Fanzo et al., 2013; Van Lancker, 2013; Filippini et al., 2014; De Schutter, 2015; Fitch and Santo, 2016; Oncini and Guetto, 2017; Oostindjer et al., 2017; Gaddis and Coplen, 2018; Bundy, 2022).

School catering in Italy before the pandemic

In Italy, school catering has a rich history, as school cafeterias have been an instrument of social policy since the end of the Second World War, when they served to combat widespread malnutrition among the population, facilitating access for the poorest social classes to a healthy and complete diet (Helstosky, 2006). Since then, school cafeterias have acquired several values and functions in the areas of children's health and wellbeing, education, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability [Ruffolo, 2001; Morgan and Sonnino, 2006, 2008; Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR), 2011, 2015]. In particular, the goal of a nutritious and balanced diet has been emphasized in recent decades, since malnutrition and food insecurity have been increasing in Italian society. Indeed, according to the national school-based monitoring system called “Eye on Health” (OKkio alla SALUTE), 30% of Italian children are suffering from obesity and being overweight, with higher values for children from families in more disadvantaged socio-economic conditions (Nardone and Spinelli, 2020). Italy has one of the highest child poverty rates in Europe and it is 31 out of 44 among the OECD countries for this indicator [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2021]. The Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT, 2021) highlights that 10% of Italian families cannot afford an adequate meal every 2 days. Sixteen percent of Italian children are living in poverty, deprived of basic necessities, including three meals per day, fresh fruits and vegetables every day, and at least one meal a day with a rich protein source (UNICEF, 2012). According to ActionAid (2020), Italian children and women are those most exposed to food poverty, characterized by both an insufficient amount of food and an inadequate diet. COVID-19 lockdown significantly accentuated the problem, since most of the families interviewed in the ActionAid survey suffered from severe food insecurity during the two first months of the pandemic, i.e., repeatedly skipping meals due to lack of sufficient food. Farello et al. (2022) observed an increase in the consumption of high-calorie snack food and obesity during the pandemic among Italian children and adolescents, while De Lorenzo et al. (2022) highlighted that the link between obesity and the COVID-19 pandemic followed the link between the social inequalities and nutritional disparities already proven in Italian society.

School catering is a service provided in nursery, infant, as well as primary and lower secondary schools, with a nature of local public service on individual demand. The local authority is therefore not obliged to set up such a service, but can do so within the scope of its general competence, taking on and managing the production of goods and activities aimed at achieving social goals and promoting the economic and civil development of local communities (Article 112 of Italian Legislative Decree 267/2000). When it decides to establish such a system, the institution undertakes to provide the service to all those who request it, establishing the share of the cost to be paid by users, which may be means-tested, and the share to be paid by the municipality (Articles 42 and 43 of Italian Presidential Decree 616/1977, as amended). The school catering service is therefore managed by municipalities, which are responsible for organizing the service in case of full-time schooling. Families pay for school meals at varying rates according to their income. For the poorest families, monitored by social services in the municipality, school meals are free. The municipalities define the characteristics of the service, in compliance with the Italian national guidelines for school nutrition issued by the Ministry of Health (Ministero della Salute, 2010, 2018, 2021), which regulate hygienic, sanitary, and nutritional aspects, as well as aspects surrounding food behavior, culture, and food waste prevention. Municipalities can deliver the service directly or, more commonly, entrust it to catering companies, which prepare meals in kitchens within schools or outside (centralized). Meals are consumed in school cafeterias. In the 2020/2021 school year, 32.9% of state school buildings were equipped with cafeterias in Italy, with a very high variability, i.e., in Piedmont the percentage reaches 62.4, while in Sicily it drops to 10.2 (Con i Bambini, 2023). About 1.4 million students eat at school, equal to 17% of the total population enrolled, but the use of school cafeterias varies across regions, i.e., almost all students access food through the cafeterias in northern regions, while access is much lower in southern regions, such as Sicily, Calabria, and Campania [Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), 2020]. Meals take place as a class group, with the children eating together with their teachers and the meal time is to all intents and purposes school time and not a break from educational activities, for both the children and the teachers. The service includes a mid-morning snack and lunch, commonly a carbohydrate-based first course, a protein-based second course accompanied by a side dish of raw or cooked vegetables, fruit or dessert, and bread.

The service is monitored both by municipalities, through the local health authorities, and Cafeteria Committees (CMs). CMs are a representative body of parents and teachers that monitor the service and have a say in public food procurement decisions (i.e., recipes, suppliers, etc.) (Galli et al., 2014). In support of the educational function of the school meal, school food education (SFE) initiatives are encouraged by the Italian Ministry of Education through the Guidelines for Food Education [Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR), 2011]. In Italy, 81% of schools organize food education courses and 63% offer extra-curricular activities regarding food (Ministero della Salute, 2021).

Moreover, a 1999 law [Finance Law no. 488, Art. 59(4)] provides for the daily use in school and hospital cafeterias of organic, typical, and traditional products, protected by designations of origin. Further environmental sustainability requirements for school meals were introduced with the Minimum Environmental Criteria regulated by the Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea with Decree No. 65 of 2020. According to Morgan and Sonnino (2008, p. 65), the Italian system is “revolutionary” in its ability to support a sustainable, high-quality agri-food supply chain.

Therefore, the Italian school catering service has acquired numerous social values in the sphere of nutrition, health and wellbeing, education, and sustainability.

The impact of COVID-19 school closures on children's nutrition

By March 2020, 171 countries had closed their schools in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and 336 million children, more than 90% of the world's enrolled children, were left out of school (UNESCO, 2020). The closures occurred in different ways and durations around the world in 2020 and 2021 (UNICEF, 2021). Quite early concern arose that children were not only missing education, but that there were also consequences due to the loss of food services provided by schools [World Food Programme (WFP), 2020a; World Food Programme (WFP), FAO, and UNICEF, 2020; Borkowski et al., 2021]. Evidence from previous school closures shows that missed school meals can cause significant consequences in children's health and wellbeing in the short and medium term. Children tend to gain weight and be more at risk of malnutrition and undernutrition during summer breaks (Franckle et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; von Hippel and Workman, 2016), while eating school meals daily is associated with healthier dietary intakes (Au et al., 2018; Decataldo and Brunella, 2018; Marcotrigiano et al., 2021). According to several authors [Rundle et al., 2020; Stavridou et al., 2021; De Lorenzo et al., 2022; Farello et al., 2022; World Health Organization (WHO), 2022], the pandemic exacerbated the childhood “obesity epidemic” (Gard and Wright, 2005) and increased the social disparity in obesity risk.

Global responses

While school meals were not possible during COVID-19 school closures, many countries and international organizations adapted their traditional school catering programs, providing home delivered meals, cash transfers, or food vouchers (Borkowski et al., 2021). World Food Programme data [World Food Programme (WFP), 2020a,b,c] indicate that take-home food supplies were the most common response alongside unconditional cash transfers and multiple responses both at state and decentralized levels.

Among high-income countries, several responded with alternatives to school meals. In the United States (US), through the national program to combat food poverty for children and young people (the US Department of Agriculture National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program), various strategies were developed to bring meals to children's homes during the pandemic. As Kinsey et al. (2020) explain, the actions were based on flexibility and included the option to: collect meals in various parts of the city, as well as receiving them at home; collect multiple meals for the same day or for multiple days at once; have people other than the students pick up meals; collect food vouchers instead of meals; choose and book meals online; and temporarily simplify the bureaucratic aspects associated with the distribution of meals. In some areas of the country, it was also possible to extend the supply of meals to the whole week and not just to school days, and to all children and young people from 0 to 18 years of age (and up to 26 years of age for those with disabilities), even those not enrolled in school, as well as distributing free meals also to the adults of the family (ibidem). These strategies involved a huge financial, organizational, and logistical effort from school catering authorities, but school meals continued to reach the children, while the staff employed in the sector remained in service and, in some cases, saw their roles enhanced, either directly or through partnerships with the private and voluntary sectors (ibidem).

In the United Kingdom (UK), a national voucher scheme was implemented and families with children eligible for free school meals were able to claim weekly shopping vouchers worth £105 to spend at supermarkets while schools were closed (UK Department for Education, 2020a,b). Following on from this experience, the City of London has decided to provide emergency funding to distribute free meals during school holidays to combat hunger, starting with the Easter holidays in 2023 (London City Hall, 2023). During remote learning, lunches were provided to children through food packs in Estonia, prepared takeaway meals in Finland, and lunch boxes in Sweden (Ala-Karvia et al., 2022). In Latvia, several alternatives were provided, such as food packs, gift cards or vouchers, transfer of money into families' bank accounts, takeaway lunches, or lunches delivered at home (Beitane et al., 2021). Food packs were, however, the simplest and safest form of state support for families with school-aged children (Beitane and Iriste, 2022). Students in Ireland were sent home packages with fresh foods, including bread, eggs, fruit, and yogurt; in Hungary, the provision of meals to children continued through meals delivered by the same kitchens used for cooking school meals before the pandemic; in Spain, families with children were entitled to cash transfers or direct food distribution during school closures [World Food Programme (WFP), 2020b,c; Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), 2022].

As we have seen in this paragraph, there is a significant body of literature focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic, which has observed the feasibility of preserving the school catering service even during crises to safeguard its social function. This recognition of the social value of school meals carries important implications for the implementation of future post-pandemic social policies.

What happened in Italy?

As UNICEF reports (Mascheroni et al., 2021), Italy was the first country in Europe to implement a nationwide lockdown. Schools and universities began to close in late February 2020, starting with the north of Italy (Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Liguria, Piedmont, Veneto, and Friuli Venezia Giulia). By March 10, 2020, the Italian government extended lockdown measures to all regions in the country. Children and their families lived in almost complete isolation for almost 2 months until May 3, 2020, and schools remained closed until September. In 2020, Italian students missed 65 days of regular school due to COVID-19 lockdown measures, compared to an average of 27 missed days among high-income countries worldwide (ibidem). Further periods of school closure with online lessons occurred in the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 school years. The duration of the interruption varied according to the spread of the virus across the region and school order, causing a general large discontinuity of school attendance. School catering was suspended whenever schools were closed. Prevention measures were implemented to regulate the school catering system when schools reopened.

Objectives

The present work aims to analyze the measures taken to face the COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian school catering system and their impact on the social values of school cafeterias. As far as we know, several studies (e.g., De Lorenzo et al., 2022; Farello et al., 2022) explored the changes in the Italian children's dietary habits that occurred at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, but only Barocco et al. (2021) looked at changes in school meals. However, they limited their investigation to the changes in the nutritional quality of school meals and to the school cafeterias in the Province of Trieste. Therefore, there was a research gap on technical and organizational changes, and on their social consequences, in the school catering system, at national level. This study intends to fill this gap, by highlighting the unique perspective of school catering representatives who deeply know limits and possibilities of adaptations in the provision of school meals. The qualitative investigation of the perspectives of the managers of the service, together with the review of public guidelines issued during the pandemic, allow for reflection on what happened and what can be learned from the pandemic. In this contribution, we propose following and reconstructing the socio-material events of an action program, i.e., the implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures in the school catering system, and therefore participate as observers in the performative dynamics investigated. In theoretical terms, the reference is to the work of Callon, who highlighted the dynamics of translation (Callon, 1984) and performativity (Callon, 2008) that characterize each action program at the time of its implementation. The issue of performativity refers to the transformative dynamics that mutually involve the socio-material network in the implementation process. According to Callon, action programs are translated in practice through inevitable negotiations, reformulations, and transfers within the spatial and temporal contexts of the network of social and material entities that are involved and influenced. This perspective justifies a pragmatic analysis of the experience, by providing precise descriptions of the dynamics that characterize it and the elements and connections that perform it (Callon and Latour, 1981). In our analysis, we asked the school catering system managers to trace all the changes that have affected the service in all phases of the pandemic. The analysis aimed to identify the ways in which materiality (technologies and techniques), practices, and meanings translated the preventive program.

Materials and methods

The analysis was performed by combining public document examination and in-depth interviews to key informants. All the state documents relating to the management of the Italian school catering service during the pandemic were examined, i.e., the School Plan for the 2020/2021 school year adopted by Decree of the Ministry of Education No. 39 of June 26th, 2020, the School Plan for the 2021/2022 school year adopted by Decree of the Ministry of Education No. 32144 of July 27th, 2021, the Technical Document on containment measures in the school sector of the Scientific Technical Committee of the Civil Protection Department of May 28th, 2020. The guidelines of several regional authorities—those of the Emilia-Romagna region (Regione Emilia Romagna, 2020), those of the Municipality of Milan (Città Metropolitana di Milano, 2020), and those jointly defined between the Lazio region and the Municipality of Rome (Regione Lazio, 2020)—and those of other relevant public institutions—the Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health [Società Italiana di Igiene Medicina Preventiva e Sanità Pubblica (SItI), 2020]—were also considered in the review of public indications.

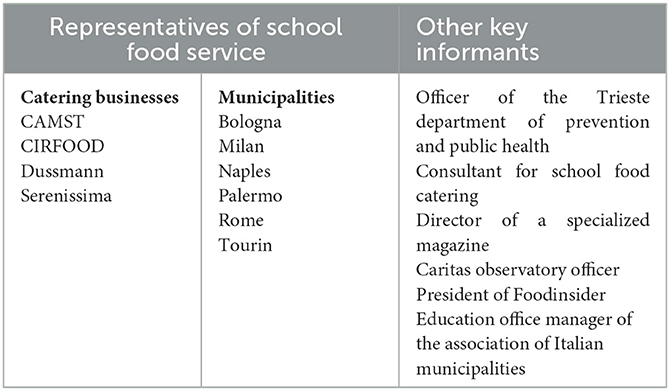

Sixteen interviews were conducted with representatives of the school catering service from the major catering companies operating in Italy (Edifis and Ristorando, 2023) and the biggest Italian municipalities (i.e., Rome, Milan, Turin, Bologna, Naples, and Palermo), and other sector experts (Table 1). Municipalities and catering companies are the key players involved in the management of the school catering system. The former oversee the governance of the service, setting forth the rules that govern it (tender specifications), and evaluating its adherence to these established requirements. The latter source raw materials, prepare, and distribute meals in alignment with the contract's specifications. Despite their distinct roles, they are the primary experts on the functioning of the service. They do not constitute two management systems but rather two different perspectives on the same management system.

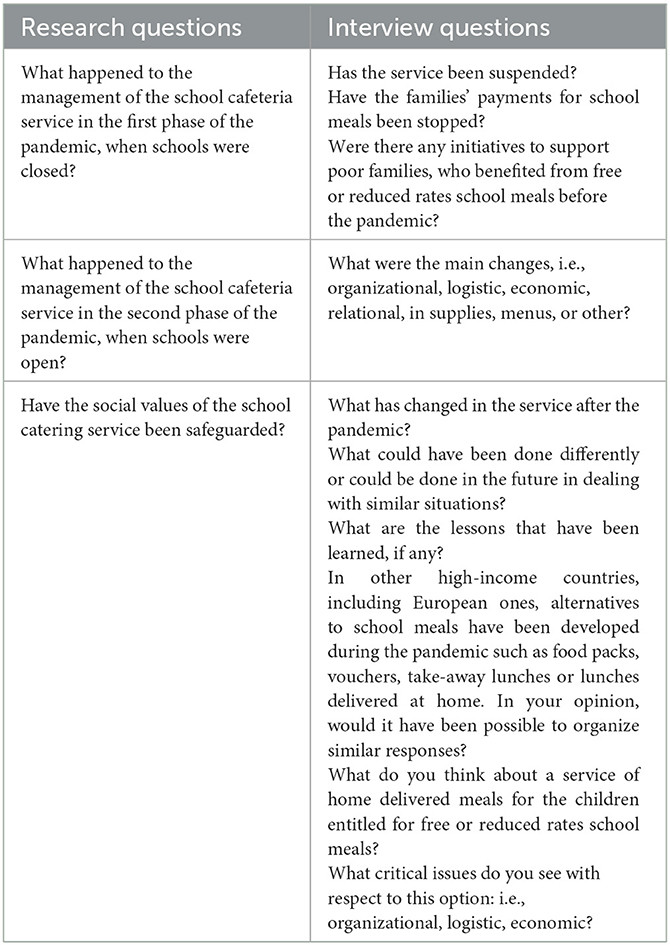

The catering companies were contacted via the email addresses available on the corporate websites, explaining the objectives of the research and asking to be put in contact with the managers of the school catering division. We proceeded in the same way with the municipalities. In a few cases it was necessary to solicit an answer by calling the telephone numbers available on the websites. For the experts, the first interviewees were tracked down by examining online sector magazines and events, then others names were obtained by interviewing the first experts. The interviews were conducted between November and April 2023 by phone. We adopted a discursive approach (Rapley, 2007) and facilitated the discussion by using an interview guide (Table 2), which consists of a sequence of topics to be covered and a list of open questions to be followed (Kvale, 2007). The interview guide is deliberately spare because it only intends to guide the interviewees' narrations, encouraging unexpected issues to emerge. Thus, the interviewing approach assumes that the research participants have substantial experience of the study specific topics and that the researcher does not know all the pertinent questions to ask in advance. At the same time, this approach allows the researcher to add questions aimed to explore issues that arose in the first interviews or to proceed more quickly on topics that previous interviews have already saturated (Charmaz, 2014, p. 56–59).

The conversations were recorded, with the interviewees' permission, and transcribed. A single researcher performed the analysis. Grounded theory in its latest evolution (e.g., Charmaz, 2014; Corbin and Strauss, 2015) was used to develop an understanding and interpretation of the data collected. Grounded theory is an interpretive method used to systematically analyze qualitative materials and to generate concepts (ibidem). In our analysis, we used different categories to identify significant changes in the organizational, logistic, economic, and regulatory aspects of the school catering service during the pandemic; the nature of roles and responsibilities of different actors and their relationships; significant processes and practices; and perceptions and views about social values of the school catering service. Therefore, in defining the relationships between categories and detailing their properties, we constructed an explanatory interpretation of the data collected that answered the research questions (i.e., what happened to the school catering service during the pandemic and what impact did the pandemic have on its social values). The whole process was managed by using a software for qualitative data analysis (MAXQDA Analytics Pro 24).

Results

During periods when schools were closed due to the pandemic, the school catering service was interrupted. The municipal authorities interviewed explain that the rates paid by families for school meals were suspended and those who had already paid the cost of the service in advance were reimbursed. Contracts between municipalities and catering companies were suspended as well. The interviewees acknowledge that, amidst the school closures, this is the only initiative that affected a service previously regarded as of great social significance.

When schools reopened, numerous changes affected the service. From the analysis of public documents, it emerges that the general guidelines to be followed to counter the pandemic were defined at central level (Italian Ministry of Education, based on the indications of the Technical-Scientific Committee of the Civil Protection Department) and included physical distancing of at least one meter, the obligation to wear masks for all school staff and for children aged 6 and over, the intensification of cleaning and sanitation operations of environments and equipment, the frequent ventilation of buildings, and the sanitation of hands with disinfectant products. In the 2021/22 school year, the obligation for COVID-19 green certification was added to these measures for all school staff. The use of school buildings was limited exclusively to conducting educational activities, including sports in the gym and the consumption of meals. Respecting the autonomy of the schools and the differences in the spaces available, it was left to the school administration, in agreement with the local government, to define solutions to implement physical distancing. For school meals, for example, measures were encouraged such as two or more shifts in the cafeteria, the use of alternative school buildings, or lunch boxes to be consumed in the classroom. A simplification of the menus was suggested in cases where the supply of foodstuffs was difficult. Finally, the use of single portions of food in individual trays and the use of disposable, compostable where possible, cutlery, glasses, and napkins were required. In the 2021/22 School Plan, the administration of meals was once again authorized in the usual forms without disposable tableware, but made of durable materials. All other precautionary measures remained in effect.

At the local level, with a collaborative project between municipalities, schools, and catering companies, the organizational and logistical procedures were developed which made it possible to implement the ministerial indications. One interviewee explains that “blanket” and “heroic” site inspections were carried out due to the commitment they required, in order to verify the specific conditions and develop ad hoc solutions. Another interviewee explains that a customized plan was made for each municipality, through a lot of discussions. The manager of a catering company explains that “To rewrite the service, the experience that the catering companies had gained in care homes and hospital catering was useful, since these services had continued to function even during the lockdown. For example, we had experimented with a teamwork approach, i.e., in multifunctional teams that included cooks and other cafeteria operators and who had to remain isolated from the rest of the staff.” In many schools the same approach was used for children, divided into learning groups isolated from other children (so-called “bubbles”).

At an operational level, to respect the distance required by the measures to combat the pandemic, the cafeterias were no longer sufficient to accommodate all the school children, so a very common solution was to have lunch in the classroom or in other areas of the school, such as the gym, or lunch in the cafeteria over several shifts. “Each municipality behaved differently. Spaces outside the schools were also used, such as the auditorium. Of course, the adequacy of the spaces was checked by the local health authority,” says the manager of a catering company. All staff working in the cafeteria used personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves. Cleaning and sanitizing actions were intensified.

The transport and distribution of meals in classrooms required a simplification of the menus, with the temporary removal of liquid meals such as soups, and the use of disposable, lighter tableware.

All those precautions that avoided contact between children and operators as much as possible were preferred: single-portion foods, where possible in heat-sealed packages, water in plastic bottles instead of tap water in jugs, multi-ration trays, lunch boxes or a platter, i.e., a single plate on which there were first, second, and side dishes, as well as disposable tableware. According to one expert interviewed, the lunch box solution made it possible for children to eat only what they liked most, with negative consequences in terms of correct nutrient intake.

An expert explains that with the lengthening of the times between the preparation and distribution of meals and the need to keep the food always at the same temperature (above 65°C) all the time, the organoleptic characteristics of the meals worsened (for example, overcooked and dry pasta), with a consequent reduction in enjoyment, consumption, and nutritional intake. The greater use of meals prepared in cooking centers and then conveyed in isothermal containers instead of meals prepared in internal kitchens also led to a worsening of the organoleptic characteristics. According to an association that monitors the quality of school meals in Italian schools, this type of precautionary measure found no scientific basis in the documents on COVID-19 and food safety from the WHO, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and the Italian National Health Institute (Istituto Superiore di Sanità). The risks of this option were the huge increase in waste (plastic and food), the loss of food fragrance, and the impoverishment of the nutritional value of the meal. “The flattening of the variety of menus—continues the interviewee—was another cause of the decline in the quality of school meals during the pandemic. In some situations, it came to just pasta, pizza, and cold cuts.”

On this point, the managers of catering companies disagree. Sometimes, there was difficulty in guaranteeing the expected foods, due to the lack of suppliers of foodstuffs and exceptions were requested from the municipalities to change the recipes set out in the contract, but the cases of deterioration in the quality of the food used were sporadic.

Monitoring by the municipal administration served to prevent changes in the organization of the service or in the recipes that were not necessary to guarantee health safety. Monitoring took place through internal staff (teachers and dieticians in the municipality). As explained by an interviewee, in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, a survey was conducted by the public administration to verify the adherence of the service to the pre-pandemic specifications. The concern of the administrators was that there may be excessive and unjustified simplification of the menus or the use of disposable materials. The investigation made it possible to ascertain that the menus had resumed almost as they were before, without substantial changes.

One interviewee explains that the consumption of meals in the classroom had a negative impact on the socialization and psychophysical wellbeing of the children. In particular, it prevented a broader exchange with the entire school population and helped to communicate a sense of closure and abnormality to the children. An interviewee recounts that his catering company conducted a survey on the perception of school meal times by teachers The results showed that for 47% of respondents it was a sad moment due to COVID-19 regulations (Osservatorio CIRFOOD District and Ipsos, 2022). At the same time, the classrooms were quieter than the cafeterias, allowing for higher quality communications. Noise in cafeterias is considered negative by 67% of teachers (ibidem).

All activities involving the presence of external personnel not strictly necessary, i.e., in addition to teachers and cafeteria operators, were suspended. All food education activities were interrupted, although some companies among those interviewed reported that they had prepared and recorded educational content that could be used online by teachers and children or delivered remotely by dietitians. Service quality control activities by CMs were also interrupted.

All participants agree in saying that the transport and distribution of meals in the classroom, the increase in shifts in the cafeteria, and the intensification of the cleaning and sanitization operations of spaces and equipment (e.g., tables and chairs) all required an increase in the working hours of the staff employed in cafeterias or the recruitment of new staff. New personnel were also necessary to deal with periods of illness and quarantine among personnel.

The volume of meals served changed continuously due to the quarantines to which all the children in the class were subjected in case of infection of individuals. A drop in attendance of about 30% is estimated by the interviewees. Meal booking systems via apps had already been used before the pandemic, but during the pandemic they became common practice.

The municipal authorities explain that the cost increases were supported by the municipal administrations, which paid the companies a supplement for the higher expenses due to the pandemic. Nonetheless, all catering companies said they had directly incurred extra costs due to the pandemic. They estimate that costs increased by 25% and that so-called “COVID rebates” covered about 90% of the higher costs incurred by companies.

One interviewee explains that Government Decree No. 4 of 2022, the “Sostegni-ter” (Supports-ter), introduced the obligation to include price revision clauses in the tender documents in the event of cost increases due to emergency situations. These clauses were introduced in public tenders with regard to award procedures called after the entry into force of the decree and until December 31st, 2023. All the tenders called before this rule did not expressly provide for the possibility of revising the price because the clause was not mandatory. A revision of the public procurement code is currently being developed and in the published drafts it seems that the possibility of revising the price in emergencies is expressly laid down.

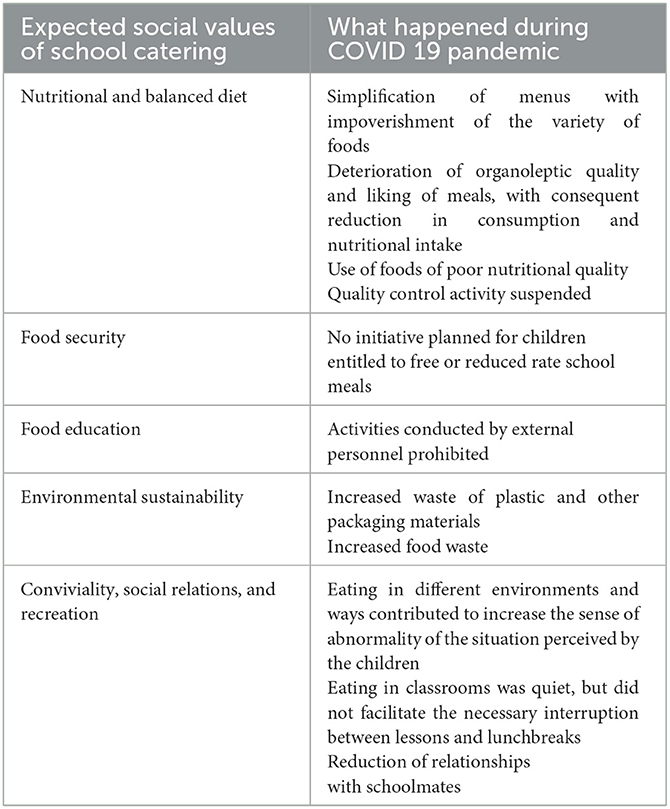

The Table 3 summarizes the changes that occurred during the pandemic with respect to the social values of the school catering service.

Table 3. Summary of what happened during the pandemic compared to the social values of school catering.

Why was an alternative to school meals not thought of during school closures?

The new organization of the service and the technical solutions introduced have led to a general deterioration of the social values recognized in school meals, as summarized in Table 3. In particular, the objective of the analysis was to understand the perception of the respondents regarding the role of the school meal in combating food insecurity, given that a significant number of articles and institutional reports, cited in the introduction, highlights the problem of food poverty in Italy, especially among children. With respect to this issue, municipal officials explain that in addition to the school catering service, the municipalities are also responsible for the service of providing home meals to people in particular situations of need, especially the elderly, the sick, those unable to leave the house, and those without aid or economic means. Generally, the service is managed under the same contract as school catering and therefore by the same catering companies. This service continued throughout the pandemic. The extension of home meals to school children, at least to those entitled to free or reduced rate meals, was not taken into consideration. There were sporadic initiatives for low-income families thanks to the sensitivity of certain local administrations, but mostly the tools used to support low-income families were food packages and vouchers for the purchase of food and other basic necessities. This aid was managed by the Civil Protection Department, charitable associations, and social services in the municipalities, but in a way that was disconnected from the school catering system. One interviewee explains that:

“During the first few months of the pandemic, there was a large amount of aid to families in need of food and other basic necessities. Food donations from food industries and catering companies were huge. Restaurants were closed and had full fridges. The food that arrived was of excellent quality and even in excessive quantities compared to the requests, and was distributed in droves. Families in a state of hardship were taken care of by charitable associations which coordinated with social services in the municipalities and with the food bank. With the persistence of the pandemic, there was a general impoverishment of families and a decrease in both quantity and quality of aid. The foodstuffs distributed returned to the pre-pandemic ones, above all canned goods, long-life, of modest quality. Adults alone and in difficulty were able to access charity cafeterias, but families with children did not go and therefore had to rely on food packages which were inadequate to support proper nutrition for children. There was, for example, no fresh food in food packages. Some charitable associations dealt with the distribution of unsold fresh food from supermarkets, but these initiatives were sporadic because they require more complex logistics and organization than charitable associations, based on the work of volunteers, are unable to ensure. Vouchers were rarely used because they did not allow control over what was purchased—there were cases of people buying alcohol with vouchers—but they would be very useful for families in situations of transient poverty. If linked to the possibility of purchasing only in neighborhood businesses, they would at the same time support small shops in difficulty due to the pandemic, and also prevent food desert situations in many urban areas, especially marginal ones. There was, however, no structural institutional coordination system that allowed for the connection of assistance services for poor families, school catering, and charitable associations…”

The need for an organic aid project for the poorest families, which also included the school catering system, also appeared possible to another interviewee, who suggested that, in order to support families living in poverty, instead of home meals, catering companies could provide the option to buy food products at their company outlets, at controlled prices, due to the fact that the catering company purchases food products in large quantities.

All respondents agreed that it would have been very difficult to organize a home meal preparation and distribution service. While technically possible, the cost of providing school meals at home is considered excessive. One interviewee specifies that “the costs of home delivery are higher than a traditional service, they can vary according to the distance and the number of deliveries to be made, indicatively an increase of 30%−40% must be considered.” Another interviewee points out that in an ordinary situation the cost of home meals could be even lower than school ones because it does not include the cost of distribution in the cafeteria, but that in times such as the current ones of increasing fuel costs, the cost of logistics would become “exorbitant” and significantly affect the cost of a meal brought home. An option of this type would also require an investment in means of transportation because the transportation used to supply to companies would not be sufficient.

This perception of the economic unsustainability of home delivered meals, widespread among service managers and many experts, is most likely influenced by the current situation of economic difficulty in the sector due to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, which has “brought the sector to its knees.” Since the beginning of the war, in fact, the continuity of supplies of foodstuffs has been compromised and their prices have increased, as have those of energy and transport. The agri-food industry, including distribution and catering, has experienced a sharp increase in production costs.

The distribution of home delivered meals to large numbers is not considered sustainable, including from a technical and organizational point of view. “Another problem with home delivered meals is that, if hot, they must be prepared and then kept at precise temperatures. This requires further organization and adequate means of transportation.” One company among those interviewed has set up a system for workers who work from home. They can book their lunch online and then pick it up at a vending machine, like the lockers used by Amazon for parcels, but refrigerated. The meal is then heated in a microwave oven. This system could also have been developed for school catering, by activating contracts with families. The important aspect to take into consideration for this method of supplying meals is that users must be correctly informed on how to store meals, if not consumed immediately after collection. Otherwise, meals may risk not being compliant from a hygienic and sanitary point of view. Safety procedures must also be defined in the home management of the meal.

A catering company sees opportunities for home delivery for the middle to high school segment of the school population. One manager explains that:

“Very often these kids eat lunch at home alone, while their parents are at work, because they are already old enough, but there is no information on the quality of their meal and we can imagine that it is not good. This population of children and young people is completely excluded from the provision of school meals and food education initiatives. Then, later, if they go to university, they will use the university cafeterias. There is a gap in the service for children between the ages of 11 and 19 and we could imagine a home delivery service by school catering companies, capable of providing meals that are certainly healthier and more balanced than those that can come from commercial catering and from the rapidly expanding food delivery system.”

According to some interviewees, parents themselves would not have appreciated the home delivered meal service, while they would have gladly accepted meal vouchers. “Already [parents] are complaining that school meals are not good, let alone if we deliver them to home!”. Another interviewee adds that the quality of school meals is not perceived by families, so food education would also be necessary for parents in order to inform them and encourage them to participate in the school catering system. Only then could they appreciate its quality. One interviewee explains that more communication with parents is needed because “they are not aware of many things and have a distorted idea of the service, based on children's feedback.” Another interviewee agrees:

“From a technical point of view, [the supply of meals at home] would be feasible, as is already done for meals for the elderly assisted at home, but I believe there is a cultural legacy in Italy in terms of collective catering at schools, in hospitals or in company cafeterias. In fact, while guaranteeing top quality materials and the supply of nutritionally correct meals, I believe that in Italy the meals prepared by families are seen as a social value and that the conviction is rooted that meals prepared at home are better than those guaranteed by a cafeteria, even if this is often not the case. We are working extensively on food education for students, CMs, and also for parents, to help people understand the quality of the service and the meals provided, but we still have to do a lot.”

According to one interviewee, family lunches have a fundamental value in Italian society and therefore school meals would not have been accepted if delivered at home. A catering company had set up a plan to provide home delivered meals for workers working from home during the pandemic. The interviewee says “it never left, because workers prefer to have food vouchers to buy food and then cook whatever they want. Similarly, it is likely that vouchers would have been more welcomed by families.” The idea that if parents stayed at home during the pandemic they would have no problem preparing meals for their children is well summarized by the words of another interviewee who jokes “parents were at home, they had nothing to do, they were preparing lunch!”. This perception seems to take into consideration only the organizational difficulties that parents had previously had in preparing their children's meals and not the costs they had to bear.

One respondent concluded that the suspension of the school catering service was taken for granted and nobody imagined that it could be otherwise. This perception contrasts with the awareness that all the interviewees expressed of the importance of school meals in tackling food insecurity. Many interviewees agree that for many children the school meal is the only complete meal of the day and that it would have been a duty to provide alternatives to low-income families. Many interviewees agree that in Italy there is a need for a step forward at a cultural level, a need to consider the school catering as an essential service, like the school itself, and to make it accessible and free for all. This is commonly referred to as “universal free meal.” To make this change possible, a political decision is needed which can only take place on the basis of a push from society. A change of cultural paradigm is, however, needed, and this currently seems distant in Italian society. The costs of the universal free meal could not be borne by municipalities, which often already have difficulties in supporting the current services with limited budgets, but at the state level.

Discussion

The article analyzes the implementation of measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic within the Italian school catering system. The results of the analysis highlight that the Italian school catering system reacted extremely slowly to the COVID-19 crisis. No alternatives to school meals were organized during the closure of the schools in the first lockdown of 2020 nor in the closure periods that occurred throughout Italy or in individual regions between autumn 2020 and spring 2021, nor during localized closures (for school classes) due to the quarantines that took place in the 2020/21 and 2021/22 school years. As admitted by the respondents, this slowness in reacting to the crisis is a symptom of the failure to recognize the school catering service as an essential service, on par with the school itself. The process which, since the post-war period, through norms and legitimation of technical solutions, had led to considering the school meal as an “institution” (Herpin, 1988; Laporte and Poulain, 2014) carrying social values, was interrupted by the pandemic. More precisely, the traditional social values of the school catering service have waned, sidelined by a new, higher social value, that of health prevention. In examining the interactions between social values, norms, and legitimation of technical solutions, Poulain and Laporte (2021) well-describe how technical solutions are able to convey a specific social value (“a proper meal”) with the consequence of achieving different outcomes in terms of combating obesity in French and British workplace catering set-ups and systems.

As highlighted by the literature cited in the introduction, in many other high-income countries, various alternative measures to school meals were implemented for school-age children, i.e., takeaway lunches, home delivered meals, cash transfers, or food vouchers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, universal school meals were provided in the US in response to the alarming rise in the prevalence of poverty and food insecurity among households with children (Cohen et al., 2022; Zuercher et al., 2022). Kinsey et al. (2020) highlighted the merit of states and school districts responding quickly to the crisis, developing innovative solutions for addressing rapidly changing demands. McLoughlin et al. (2020) stressed the importance of collaboration at community level, i.e., school districts working with the Red Cross, volunteers, and school food staff to address the emergency. Several alternatives were provided in European countries showing adaptation, innovation, and cooperation at community level in the response to the COVID-19 crisis [Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), 2020; World Food Programme (WFP), 2020a,b,c; Beitane et al., 2021; Ala-Karvia et al., 2022; Beitane and Iriste, 2022]. In Italy, on the contrary, the school catering system only moved with the reopening of schools, defining the measures that had to be taken to counter the spread of the virus. The practices developed along the catering chain were analyzed with reference to the works of Callon who emphasizes the translation (1984) and performative (2008) dynamics that characterize each action program (Latour, 1992) at the moment of its implementation. According to this analytical perspective, action programs are literally “translated” into practice through a collective process of negotiation among the actors involved and transferred in a precise spatial and temporal context. A pragmatic analysis of the whole procedure—from intention to implementation—has the potential to detect the ways in which the project is translated and performed (Callon and Latour, 1981). Following this approach, the dense description of the technical and organizational processes of school catering, through the punctual narration of the elements that performed the preventive project during the pandemic, demonstrates the predominantly performative nature of the actions implemented. Technical and organizational solutions have been developed and adapted to the local context for responding to government indications as effectively as possible. It also demonstrates that the objectives were negotiated and aligned by catering companies, municipalities, and school managers, leaving out the other social actors of the system (children, teachers, and parents). The translation in practice of the safety and prevention measures focuses on the issue of performativity and on the co-agency role of the materiality (Barad, 2003), neglecting the social component of socio-material practices and progressively compromising the initial social values of the service, in particular those of food security, education, and environmental sustainability.

The action program was implemented both in regulatory and procedural terms, in compliance with safety precautions, and in technical and organizational terms. The security procedures went beyond the ministerial technical-scientific protocols, constituting a non-explicit reassurance for all decision makers, which Lupton (1999) defines as “sociocultural stabilization” through specific judgment criteria, control and verification technologies, meanings, formulae, and symbols. The action program, on the other hand, proved to be weakly connected with the program's end users, i.e., children, teachers, and, ultimately, parents, revealing a misalignment between health objectives and social, educational, and environmental objectives. The changes that occurred with the pandemic focused on distancing children during meals, with the possibility of eating in the classroom or in the cafeteria, but over several shifts; the use of lunch boxes and disposable tableware to speed up the distribution and consumption of meals, since shifts were contracted; a certain simplification of the menus; and the suspension of food education and service quality control activities by the CMs to avoid unnecessary interpersonal contact. These changes had consequences on the organoleptic quality of meals and reduced consumption and consequently nutritional intake. Barocco et al. (2021) carried out a study to verify the impact of the pandemic on the food security of state school cafeterias in the Province of Trieste and determine any nutritional critical points and corrective actions to guarantee healthy meals for all students. They concluded that the pandemic affected the quality of meals served, in particular that of afternoon snacks and fresh desserts. They suggest the importance of taking action to continuously support school caterers with technical assistance to overcome the impact of COVID-19.

The educational value of meals was no longer supported by food education activities. Waste of food and material from disposable tableware and single-portion packaging also increased. Attention to the environmental impact of school meals thus ceased.

The suspension of school meals took place in a context of food poverty already entrenched in Italy (Maino et al., 2016) and exacerbated by the pandemic (Saraceno et al., 2022). In Italy, the action to combat food poverty is carried out by a plurality of public and private stakeholders and using different intervention models, but the lack of a strategic framework and institutional coordination, the marginality of the phenomenon of food poverty in social policy, and the fragmentation of law enforcement action make the long-term response to food insecurity ineffective (Galli et al., 2016, 2018; Arcuri, 2019; ActionAid, 2020). The measures adopted during the pandemic to counter the difficulties of low-income families were the distribution of food packages and the provision of shopping vouchers for the purchase of food and basic necessities. These measures have been judged insufficient and inadequate and at the same time the pandemic highlighted the need for a capillary and accessible system to combat food poverty (ActionAid, 2020). In this sense, the role of school catering service is considered crucial in tackling children's food poverty, since for some children, school meal represents the most complete and healthy meal of the day (Save the Children, 2018; Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, 2020; Autorità garante per l'infanzia e l'adolescenza, 2022). As explained by municipal officials, data on school meal rates and on the population that uses free or reduced rate school meals are held by individual municipalities, which can autonomously decide the rates of the service means-tested according to family income. There is no information aggregated at the national level which would instead be of interest as an indirect measure of Italian food poverty.

In this article, we wanted to explore the point of view of service managers on alternative responses to the suspension of school catering service in the event of school closures. The possibility of providing home delivered meals was excluded by all respondents, citing excessive organizational and logistical complexity and economic unsustainability. The interviewed school catering service managers often come back to the cost of the service and the alleged economic unsustainability of providing an alternative to school meals during pandemic school closures. Further investment is deemed unfeasible. This limit appears to be a measure of the actual social value attributed to the school catering service. Similarly, Poulain and Laporte (2021), analyzing the French and British workplace catering systems, explain that the average cash value of meal vouchers expresses how important catering at work is to decision-makers and corporate catering managers.

For the interviewees, parental acceptability of school meals delivered at home is considered low due to a widespread perception in Italian society that the family meal is always preferable. This perception appears to be in contrast with the increasingly widespread use of takeaway and delivered meal services (Manuelli, 2023). In any case, from our analysis, it emerges that the point of view of families was not taken into consideration in the application of anti-pandemic measures. The aid system based on food vouchers was instead considered easier to implement, even if it derived from a political choice of the central government because the municipalities were not considered able to bear the necessary cost. Instead, Parnham et al. (2020) concluded that the voucher scheme did not adequately serve children who could not attend school during the pandemic. Against a background of every possible alternative to the suspension of the service, there was a problem of costs and regulatory framework for the service, which is not considered an essential public service, but a public service on individual demand and therefore paid for in whole or in part by families.

There are two major limitations in this study. First, our research highlights the unique perspective of school catering service representatives. Indeed, we collected the points of view of those who manage the school catering service because they know more deeply than anyone else its limits and possibilities of adaptation. At the same time, they reported individual viewpoints, referred to specific corporate and municipal contexts, within the framework of a hopefully exceptional situation. Therefore, the research findings do not allow to generalize. The second limitation concerns the fact that only one researcher performed the analysis and interpreted the data. This might increase the risk of unintended biased opinions due to the researcher's cultural background or perspectives on phenomena investigated. Even though the research findings must be interpreted with caution, they contribute to a reflection, that certainly needs further research, on the importance of Italian school catering system in combatting food poverty and how it can be improved in the future, especially during school closure.

Conclusion

The pandemic created unexpected challenges for the administration of the Italian school catering service. The service was suspended for as long as schools were closed, with no alternatives for children. The complexity of social values with which the school catering service has been invested by public social and health policy in Italy in recent decades disappeared through the absolute carelessness with which this system was suspended for months, after the closure of schools due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, solutions were found in the rest of the world to continue reaching children and young people with school meals. Approximately 2 million lunches and mid-morning breakfasts are served daily in Italian schools (Società Italiana di Igiene Medicina Preventiva e Sanità Pubblica (SItI), 2020). Access to these meals was disrupted as a result of long-term school closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially decreasing both student nutrient intake and household food security.

When schools were open, the service changed by responding to preventive measures defined at central government level and implemented locally through coordination between municipalities, catering companies, and schools. Children, teachers, and families, i.e., the service's end users, were excluded from these discussions. The result was a mismatch between pandemic prevention goals and school catering social values.

The recent analysis carried out by the United Nations [World Food Programme (WFP), 2023] describes the state of school catering worldwide in 2022, 2 years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. School catering is once again one of the largest and most widespread social safety nets in the world and the number of children being reached by school catering programs now exceeds pre-pandemic levels. This rapid and unprecedented rebound has been driven by national political leadership at the highest levels, channeled through the School Meals Coalition co-created in less than a year by political leaders from 76 countries representing 58% of the world's population across all income levels. Italy is not among the member states who joined the coalition (School Meals Coalition, n.d.). The reflection on what happened in Italy during the pandemic developed in this article helps to highlight that there is little interest in the food security of children, confirmed by the absence of a debate on the school catering as an essential service and on the universal school meal in Italian society (Ferrando et al., 2018; Ferrando, 2019). The analysis of what happened during the pandemic can be useful for informing future school food policy for out-of-school time, such as over the summer. Children in low-income families must be protected from the unintended nutritional consequences of school closures. School catering should be considered as a measure of social protection for low-income families, but its role is weakened by the lack of a connection between social services and school catering (Galli et al., 2016, 2018; Save the Children, 2018; Arcuri, 2019; ActionAid, 2020; Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, 2020). From the pandemic we can learn that the Italian school catering system is ready to respond effectively to emergencies from an organizational and technical point of view, through coordination and teamwork among the main catering players (i.e., catering companies, municipalities, and school managers) aimed at identifying procedural innovations and adapting them to different local contexts. On the other hand, it is not prepared to take on the disruptive phenomenon of food poverty, even failing to imagine the possibility of offering meals to children outside the time and space of school.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was obtained to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

EP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by CNR project FOE-2021 DBA.AD005.225. The people interviewed in this work were informed about the research objectives and expressed their verbal consent.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ActionAid (2020). La pandemia che affama L'Italia. Covid-19, povertà alimentare e diritto al cibo. Available online at: https://actionaid-it.imgix.net/uploads/2020/10/AA_Report_Poverta_Alimentare_2020.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Ala-Karvia, U., Goralska-Walczak, R., Piirsalu, E., Filippova, E., Kazimierczak, R., Post, A. et al. (2022). COVID-19 driven adaptations in the provision of school meals in the Baltic Sea Region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:750598. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.750598

Arcuri, S. (2019). Food poverty, food waste and the consensus frame on charitable food redistribution in Italy. Agric. Human Values 36, 263–275. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-09918-1

Ashe, L. M., and Sonnino, R. (2013). At the crossroads: new paradigms of food security, public health nutrition and school food. Public Health Nutr. 16, 1020–1027. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004326

Au, L. E., Gurzo, K., Gosliner, W., Webb, K. L., Crawford, P. B., Ritchie, L. D. et al. (2018). Eating school meals daily is associated with healthier dietary intakes: the Healthy Communities Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 1474–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.01.010

Autorità garante per l'infanzia e l'adolescenza (2022). Relazione al parlamento 2021 Autorità garante per l'infanzia e l'adolescenza. Available online at: https://www.garanteinfanzia.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/agia-relazione-parlamento-2021.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Baltag, V., Sidaner, E., Bundy, D., Guthold, R., Nwachukwu, C., Engesveen, K. et al. (2022). Realising the potential of schools to improve adolescent nutrition. BMJ 379:e067678. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067678

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs 28, 801–831. doi: 10.1086/345321

Barocco, G., Maggiore, A., Calabretti, A., Bogoni, P., and Longo, T. (2021). Assessment of COVID-19 pandemic impact on guaranteeing food security in local school catering. Eur. J. Public Health 31, 443–444. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab165.278

Beitane, I., and Iriste, S. (2022). The assessment of school lunches in the form of food packs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latvia. Children 9:1459. doi: 10.3390/children9101459

Beitane, I., Iriste, S., Riekstina-Dolge, R., Krumina-Zemture, G., and Eglite, M. (2021). Parents' experience regarding school meals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 13:4211. doi: 10.3390/nu13124211

Benn, J., and Carlsson, M. (2014). Learning through school meals? Appetite 78, 23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.008

Borkowski, A., Ortiz-Correa, J. S., Bundy, D. A. P., Burbano, C., Hayashi, C., Lloyd-Evans, E. et al. (2021). “COVID-19: missing more than a classroom. the impact of school closures on children's nutrition,” in UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti Working Paper WP-2021-01. Available online at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1176-covid-19-missing-more-than-a-classroom-the-impact-of-school-closures-on-childrens-nutrition.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

Bundy, D. (2022). “School meals programmes: their multi-sectoral benefits and the role of the School Meals Coalition to restore and strengthen national programmes to ensure the holistic wellbeing of the learner,” in Keynote lecture, Online Symposium: Impacts of Covid-19 Pandemic on Catering in Schools, November 16, 2022. Available online at: https://hiddenhunger.uni-hohenheim.de/en/pre-symposium (accessed May 5, 2023).

Callon, M. (1984). Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of Saint Brieuc Bay. Sociol. Rev. 32, 196–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x

Callon, M. (2008). “What does it mean to say that economics is performative?” in Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, 1st ed., eds D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, and L. Siu (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 311–357. doi: 10.1515/9780691214665-013

Callon, M., and Latour, B. (1981). “Unscrewing the big Leviathan: how actors macrostructure reality and how sociologists help them to do so,” in Advances in Social Theory and Methodology Toward an Integration of Micro and Macro-Sociologies, 1st ed., eds K. Knorr Cetina, and A. Cicourel (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul),277–303.

Capacci, S., Mazzocchi, M., Shankar, B., Macias, J. B., Verbeke, W., Pérez-Cueto, F. J. A. et al. (2012). Policies to promote healthy eating in Europe: a structured review of policies and their effectiveness. Nutr. Rev. 70, 188–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00442.x

Chang, C., and Jung, H. (2017). The role of formal schooling on weight in young children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 82(C), 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.005

Chriqui, J. F., Pickel, M., and Story, M. (2014). Influence of school competitive food and beverage policies on obesity, consumption, and availability. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 279–286. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4457

Città Metropolitana di Milano (2020). Ristorazione scolastica in relazione al rischio COVID-19: riflessioni in occasione della riapertura dell'anno scolastico 2020-2021. Available online at: https://www.ats-milano.it/portale/Portals/0/emergenza%20coronavirus/ATS%20Milano_riflessioni%20sul%20pasto%20a%20scuola.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Cohen, J. F. W., Polacsek, M., Hecht, C. E., Hecht, K., Read, M., Olarte, D. A. et al. (2022). Implementation of universal school meals during COVID-19 and beyond: challenges and benefits for school meals programs in maine. Nutrients 14:4031. doi: 10.3390/nu14194031

Con i Bambini (2023). Servono mense scolastiche dove è più diffusa la povertà alimentare. Available online at: https://www.conibambini.org/osservatorio/servono-mense-scolastiche-dove-e-piu-diffusa-la-poverta-alimentare/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 4th ed. London: Sage.

De Lorenzo, A., Cenname, G., Marchetti, M., Gualtieri, P., Dri, M., Carrano, E. et al. (2022). Social inequalities and nutritional disparities: the link between obesity and COVID-19. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 320–339. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202201_27784

De Schutter, O. (2014). The Power of Procurement: Public Purchasing in the Service of Realizing the Right to Food. Briefing Note 08. Available online at: http://www.srfood.org/en/the-power-of-procurement-public-purchasing-in-the-service-of-realizing the-right-to-food (accessed May 5, 2023).

De Schutter, O. (2015). “Institutional food purchasing as a tool for food system reform,” in Global Alliance for the Future of Food, Advancing Health and Well-Being in Food Systems: Strategic Opportunities for Funder (Toronto, ON), 13–60.

Decataldo, A., and Brunella, F. (2018). Is eating in the school canteen better to fight overweight? A sociological observational study on nutrition in Italian children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 94(C), 246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.002

Di Chiro, G. (2008). Living environmentalisms: coalition politics, social reproduction, and environmental justice. Env. Polit. 17, 276–298. doi: 10.1080/09644010801936230

Fanzo, J., Hunter, D., Borelli, T., and Mattei, F. (2013). Diversifying Food and Diets: Using Agricultural Biodiversity to Improve Nutrition and Health. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203127261

Farello, G., D'Andrea, M., Quarta, A., Grossi, A., Pompili, D., Altobelli, E. et al. (2022). Children and adolescents dietary habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Nutrients 14:2135. doi: 10.3390/nu14102135

Ferrando, T. (2019). “Available online at: marginalization to integration: universal, free and sustainable meals in Italian school canteens as expressions of the right to education and the right to food,” in The Bristol Law Research Paper Series, 39. Available online at: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/law/documents/BLRP%20No.%203%202019%20-%20Ferrando.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Ferrando, T., De Gregorio, V., Lorenzini, S., and Mahillon, L. (2018). The right to food in Italy between present and future. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3229134 (accessed May 5, 2023). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3229134

Filippini, M., Masiero, G., and Medici, D. (2014). The demand for school meal services by Swiss households. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 85, 475–495. doi: 10.1111/apce.12040

Finance Law no. 488 Art. 59(4). “Measures to facilitate the development of organic and quality agriculture”. Gazzetta ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Legge 23 dicembre 1999, n. 488. Available online at: https://www.gazzettauffi-714ciale.it/eli/id/2000/01/29/00A00641/sg (accessed May 5, 2023)..

Fitch, C., and Santo, R. (2016). Instituting Change: An Overview of Institutional Food Procurement and Recommendations for Improvement. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future.

Franckle, R., Adler, R., and Davison, K. (2014). Accelerated weight gain among children during summer versus school year and related racial/ethnic disparities: a systematic review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 11:130355. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130355

Gaddis, J., and Coplen, A. K. (2018). Reorganizing school lunch for a more just and sustainable food system in the US. Fem. Econ. 24, 89–112. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2017.1383621

Galli, F., Arcuri, S., Bartolini, F., Vervoort, J., and Brunori, G. (2016). Exploring scenario guided pathways for food assistance in Tuscany. BAE Bio-based Appl. Econ. 5, 237–266. doi: 10.13128/BAE-18520

Galli, F., Brunori, G., Di Iacovo, F., and Innocenti, S. (2014). Co-producing sustainability: involving parents and civil society in the governance of school meal services. A case study from Pisa, Italy. Sustainability 6, 1643–1666. doi: 10.3390/su6041643

Galli, F., Hebinck, A., and Carroll, B. (2018). Addressing food poverty in systems: governance of food assistance in three European countries. Food Secur. 10, 1353–1370. doi: 10.1007/s12571-018-0850-z

Gard, M., and Wright, J. (2005). The Obesity Epidemic: Science, Morality, and Ideology. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203619308

Gleason, P. M., and Suitor, C. W. (2003). Eating at school: how the national school lunch program affects children's Am. J. Agric. Econ. 85, 1047–1061. doi: 10.1111/1467-8276.00507

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF) (2020). COVID-19 and School Meals around the World. What We're Seeing on the Ground. Available online at: https://gcnf.org/covid/ (accessed May 5, 2023).

Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF) (2022). Global Child Nutrition Foundation School Meal Programs Around the World: Results from the 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs. Available online at: survey.gcnf.org/2021-global-survey (accessed May 5, 2023).

Greenhalgh, T., Kristjansson, E., and Robinson, V. (2007). Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ 335, 858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39359.525174.AD

Harper, C., and Wells, L. (2007). School Meal Provision in England and Other Western Countries: A Review. Sheffield: School Food Trust.

Harper, C., Wood, L., and Mitchell, C. (2008). The Provision of School Food in 18 Countries. Sheffield: School Food Trust.

Herpin, T. (1988). Le repas comme institution. Compte rendu d'une enquête exploratoire. Rev. Fr. Sociol. 29, 503–521. doi: 10.2307/3321627

Huang, J., Barnidge, E., and Kim, Y. (2015). Children receiving free or reduced-price school lunch have higher food insufficiency rates in summer. J. Nutr. 145, 2161–2168. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214486

ISTAT (2021). Rapporto bes 2020: Il benessere equo e sostenibile in Italia. Available online at: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2021/03/BES_2020.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).

Jaime, P. C., and Lock, K. (2009). Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Prev. Med. 48, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.018

Jomaa, L. H., McDonnell, E., and Probart, C. (2011). School feeding programs in developing countries: impacts on children's health and educational outcomes. Nutr. Rev. 69, 83–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00369.x

Kinsey, E. W., Hecht, A. A., Dunn, C. G., Levi, R., Read, M. A., Smith, C. et al. (2020). School closures during COVID-19: opportunities for Innovation in Meal Service. Am. J. Public Health 110, 1635–1643. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305875

Kleine, D., and Brightwell, M. D. G. (2015). Repoliticising and scaling up ethical consumption: lessons from public procurement for school meals in Brazil. Geoforum 67, 135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.08.016

Kristjansson, B., Petticrew, M., MacDonald, B., Krasevec, J., Janzen, L., Greenhalgh, T. et al. (2007). School feeding for improving the physical and psychosocial health of disadvantaged students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1:CD004676. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004676.pub2

Laporte, C., and Poulain, J. P. (2014). Restauration d'entreprise en France et au Royaume-Uni. Synchronisation sociale alimentaire et obésité. Ethnol. Fr. 44, 93–103. doi: 10.3917/ethn.141.0093

Latour, B. (1992). “Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts,” in Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, eds W. E. Bijker, and J. Law (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 225–258.

Lombardi, M., and Costantino, M. (2020). A social innovation model for reducing food waste: the case study of an italian non-profit organization. Adm. Sci. 10:45. doi: 10.3390/admsci10030045

London City Hall (2023). Emergency free holiday meals. Available online at: https://www.london.gov.uk/who-we-are/what-mayor-does/priorities-london/emergency-free-holiday-meals (accessed May 5, 2023).

Maino, F., Lodi Rizzini, C., and Bandera, L. (2016). Povertà Alimentare in Italia: Le Risposte del Secondo Welfare. New York, NY: Il Mulino.

Manuelli, M. T. (2023). Food delivery, business da 1.8 miliardi ma c'è chi abbandona l'Italia. Il Sole 24 Ore. Available online at: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/food-delivery-business-18-miliardi-ma-c-e-chi-abbandona-l-italia-AFJwc6z (accessed April 8, 2024).

Marcotrigiano, V., Stingi, G. D., Fregnan, S., Magarelli, P., Pasquale, P., Russo, S. et al. (2021). An integrated control plan in primary schools: results of a field investigation on nutritional and hygienic features in the apulia region (Southern Italy). Nutrients 13:3006. doi: 10.3390/nu13093006

Mascheroni, G., Saeed, M., Valenza, M., Cino, D., Dreesen, T., Zaffaroni, L. G. et al. (2021). Learning at a Distance: Children's remote learning experiences in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. Available online at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1182-learning-at-a-distance-childrens-remote-learning-experiences-in-italy-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

McCrudden, C. (2004). Using public procurement to achieve social outcomes. Nat. Resour. Forum 28, 257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00099.x

McLoughlin, G. M., McCarthy, J. A., McGuirt, J. T., Singleton, C. R., Dunn, C. G., Gadhoke, P. et al. (2020). Addressing food insecurity through a health equity lens: a case study of large urban school districts during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Urban Health 97, 759–775. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00476-0

Ministero della Salute (2010). Linee di Indirizzo Nazionale per la Ristorazione Scolastica. Available online at: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1248_allegato.pdf (accessed May 5, 2023).