95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 04 April 2024

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 8 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1346129

This article is part of the Research Topic Alternative Food Networks for Sustainable, Just, Resilient and Productive Food Systems View all 15 articles

Jasmine E. Black1,2*

Jasmine E. Black1,2*Introduction: Alternative Food Networks (AFNs) are important sources of community-driven sustainable food production and consumption. It is apparent that despite the existing environmentally friendly ways of producing food, such networks are not yet multiplying at a rate which could help tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. This study is set in Sado island, Japan, which has become well known for its farming practices protecting the crested ibis, as well as its GIAHS status, but which also has an AFN beyond these accreditations. It investigates the challenges and opportunities of Sado’s AFN to find ways to help it thrive, and give potential pointers for developing new AFN’s.

Methods: In this research I use a mix of experiential sensory ethnography, socially-engaged art and interviews to understand the challenges and opportunities of an AFN in Sado island, Japan. A range of Sado’s AFN actors were engaged to provide a more holistic picture.

Results: Young and new entrant farmers, food processors and retailers in Sado expressed the need for their work to be fun as well as in coexistence with nature, using innovative practices and models to make this a reality. AFN actors also revealed a great capacity to undertake numerous food and culture related events, for the purpose of community, throughout the year. Despite this, there are gaps in capacity, and a lingering negative image of farming and rural areas as difficult places to live. These factors are stemming the ability for new AFNs to begin and existing ones to thrive.

Discussion: Giving farming a fun, empowering and positive image whilst creating greater networking capacity could strengthen this AFN and help create new ones in other ruralities. Further, better acknowledging the importance of the culture and arts through which people connect to nature could form a greater source of pride and motivation to stay in rural areas.

Alternative food networks (AFNs) are often diverse by nature, in their actors’ motivations, practices and the contexts in which they are situated (Holloway et al., 2016). Generally speaking, alternative food networks are alternative in that they seek to produce, process and sell food in a way that is different to what has come to be known as “conventional” agriculture and food systems, which are highly mechanized, grow crops as monocultures, use chemical fertilizers and pesticides and often long supply chains (Beus and Dunlap, 1990; Ericksen, 2008). AFN actors are often motivated to increase local food, biodiversity, wellbeing and strengthen local communities, with an overarching aim of achieving greater sustainability (Michel-Villarreal et al., 2019). They are therefore vital in combating both climate change and biodiversity loss, while strengthening human-nature connections. In this paper, I use the definition of AFNs as including these aspects, with the understanding that they are heterogenous and that not all characteristics may exist within an AFN. For example, the physical location of an AFN may mean that even if the food is grown in a sustainable manner, it may have to be sold outside of the locality to be economically viable (Watts et al., 2005). AFNs often come with the presumption of being sustainable, however as with the “local trap”, this is not always true and it is important to be aware of areas where sustainability can be improved (Born and Purcell, 2006; Michel-Villarreal et al., 2019).

AFN’s In Japan constitute several different alternative food movements. These consist of food system structures as well as those focused on production methods. “Teikei” (the Japanese predecessor of Community Supported Agriculture, “CSA”), is a structure defined by the close partnership between producers and consumers and has evolved its structure over time (Hatano, 2008; Kondoh, 2015; Kondo, 2021). Those which focus on production methods are numerous: organic (“yūki saibai” 有機栽培 or オーガニック) which allows some pesticides to be used as certified as safe by Japan Agricultural Standards (JAS) and must have this certified labeling; (“mu nōyaku” 無農薬) which does not use any pesticides; reduced chemical farming, including reduced pesticides and/or fertilizers (“gen kagaku hiryō/kagaku nōyaku” 減化学肥料・化学農薬); specially cultivated agricultural products, using pesticide and fertilizer reductions of 50% or less (“tokubetsu saibai nōsan butsu” 特別栽培農産物) and natural agriculture “NA”, (“shizen nōhō” 自然農法) which does not use any inputs (MAFF, 2008). NA was pioneered by Mokichi Okada, Masanobu Fukuoka and later Akinori Kimura, their practices stemming from ethnic and philosophical human-nature connection (Fukuoka, 1978; Miyake and Kohsaka, 2020; Kimura, 2023). This diversity of practices can make for a complicated alternative food system, with farmers unsure of which methods to use and consumers unaware of the differences or labels. However, it also allows officially recognized pathways for farmers to reduce reliance on chemical use, such as reduced chemical farming (RCF).

Within Japan’s agricultural system, Japan Agriculture Cooperatives (農業協同組合 “nōgyō kyōdō kumiai”, also known as JA or “nōkyō” 農協) has a long history and holds a lot of power. It was set up as a government-controlled farmer association and plays a prevalent role in selling farm produce, farm chemicals and machinery, giving advice and training, and in certification. JA is not always favorable in the eyes of farmers, however, as it often sells farm-use products at high prices and does not always support their interests (Freiner, 2019).

In multiplying AFNs and increasing sustainable farming, there are therefore a myriad of choices but also difficulties. Farmers need not only navigate the growing process but selling and marketing too. Declining rural populations and lack of farming successors also create a severe problem for the future of farming (Reyes et al., 2020; Usman et al., 2021). Within the food network, other actors such as food processors and retailers are also trying to find alternative means within the capitalist globalized system. These actors play an important role in using sustainably grown agricultural products, interacting with customers and creating community within an AFN (Trivette, 2019).

Sado island is Japan’s sixth largest island located in the northwest Sea of Japan, with a range of ecosystems and produce of rice, buckwheat and a range of cultivated and wild fruits and vegetables. Its population has declined from 62,727 in 2010 to 51,492 in 2021 (Sado City Council, 2021). It has become renowned for environmentally friendly farming. In 2008, a certified brand of rice called “tokimai” (トキ米) was created by farmers, JA Sado and Sado city council in order to promote environmentally friendly ways of farming rice (e.g., reducing chemical inputs) to protect and increase numbers of the Japanese crested ibis (“toki” in Japanese) (Maharjan et al., 2022). As a result of this, it was given Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) status in 2011 (Maharjan et al., 2021). GIAHS has similarities with satoyama and socio-ecological production landscape (SEPLS) concepts, which aim to promote human-nature relationships through managing land for both food, biodiversity and environmental health (Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment, 2010; Indrawan et al., 2014). Sado also has a network of organic and NA farmers, as well as a lively cultural arts and food calendar throughout the year.

In order to ensure the continuity of Sado island’s AFN, it is important to understand what support different actors need. This paper investigates Sado’s AFN, through a range of actors (farmers, food processors, retailers, politicians, and others), the importance of connections between these different actors and their needs in terms of support to strengthen and continue the AFN. Such an investigation, in an island setting in Japan, gives the paper originality.

This paper includes the results from 1 year living in and undertaking experiential engagement in an AFN with its communities and actors, on the island of Sado, Japan. It draws on socially-engaged arts (SEA) and EcoArts methods, in which the researcher situates oneself in a community in order to engage with people, discover issues and find pathways to solutions together (Helguera, 2011; Weintraub, 2012; Scholette et al., 2018). It is process-led, rather than outcome-led, and uses an organic approach to undertaking the process – allowing the situation, connections and events that arise to influence the direction of the research and therefore the results (Scholette et al., 2018). The “arts” element does not necessarily mean that there will be an end-product in the form of a more traditional art piece, but that the process itself is the form of art.

The methods also draw upon Pink’s theory of sensory ethnography, which adheres to a similar process and concept of reflexivity and experiential research. In understanding that experience is multi-sensorial, it allows us to access and understand social norms, relationships, cultures, ecologies in both body and mind through our senses. It is therefore perhaps not just a process of research, but also a process of living and growing oneself through such a research process. Through realizing this experience and the growth that comes with it, it can be a starting point for creating positive change and undertaking solutions to issues with the community around oneself (Pink, 2015, 2021).

These research methods all allow the building of relationships and trust within the community, and the experiential element of living in the study area allows opportunity for happen-chance encounters and experiences that would not otherwise occur. A deeper level of understanding and learning therefore takes place through these research methods, than more standard forms of social research such as interviews and surveys.

Further, the theory of relational studies and social network analysis demonstrates that people are relationally, intrinsically and instrumentally connected to each other and nature, therefore careful consideration of these connections has been undertaken in the research methods (Klain et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2018).

In order to support the experiential research, semi-structured interviews were also used to delve deeply into issues around support needs for AFNs. Questions included what support, challenges and opportunities farmers, food processors and retailers need and face in starting and then successfully continuing their sustainable practices (see Supplementary material for details). Interviews were conducted in Japanese. They were audio recorded as well as notes being taken at the time of the interview. A sample of the interviews were conducted with another bilingual Japanese-English speaker, to cross-check the interpretation of the responses. A network map was also drawn with each interviewee, in order to understand how they relate to different AFN actors in and outside of Sado. Alongside the interview questions and experiential ethnography, these helped to create Figures 1–3, a representation of Sado’s AFN. Each interview lasted between 1.5–2 h and were held with a diverse range of AFN actors within the study site in order to get a representative dataset of the area. A total of 32 interviews were undertaken. The interviews stopped once a saturation point of information was achieved (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022). Tables 1–3 show a breakdown of the interviewees, the characteristics which define their practices and demographics related to the study, such as I or U-turn1 status. The tables are grouped into farmers (18), food processors and retailers (7) and other food network actors (7). The farmers, processors and retailers provided an insight into their specific practices, support needs, challenges and opportunities. The other food network actors provided an overview of the local, regional and national food system in Japan and some of the systems supporting the alternative food network in Sado.

Figure 1. Schematic of Sado’s AFN farmer types based on practice and what sales channels they use. Note, interviewees considered selling to online sales platforms, which show their farmer profiles, as direct sales. The schematic shows a varied landscape of farming practices and selling methods within the AFN.

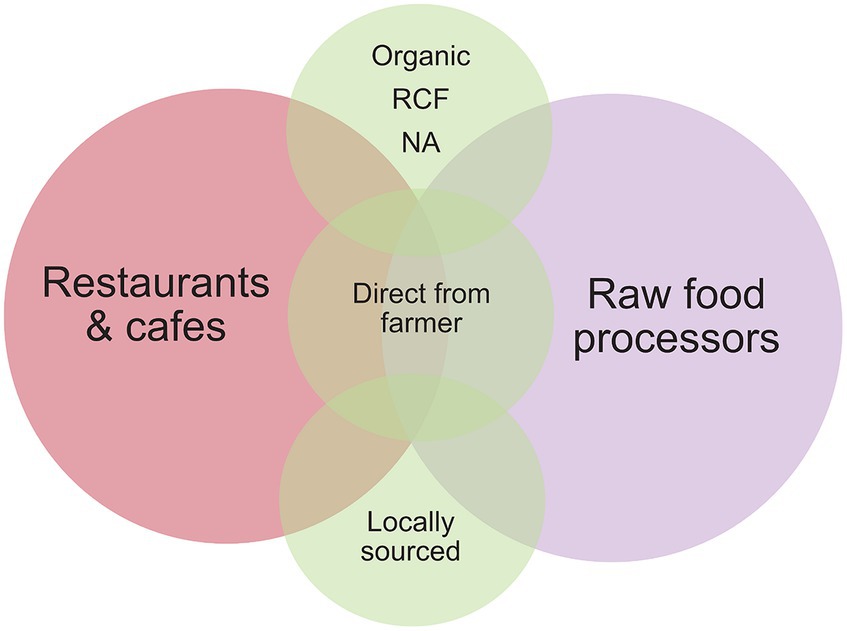

Figure 2. Schematic of Sado’s AFN food processors & retailers. The overlap between restaurants, cafes and raw food processors who work on a cottage-industry scale is shown through their alternative practices of sourcing raw ingredients (organic/RCF/NA; direct from the farmer; locally sourced).

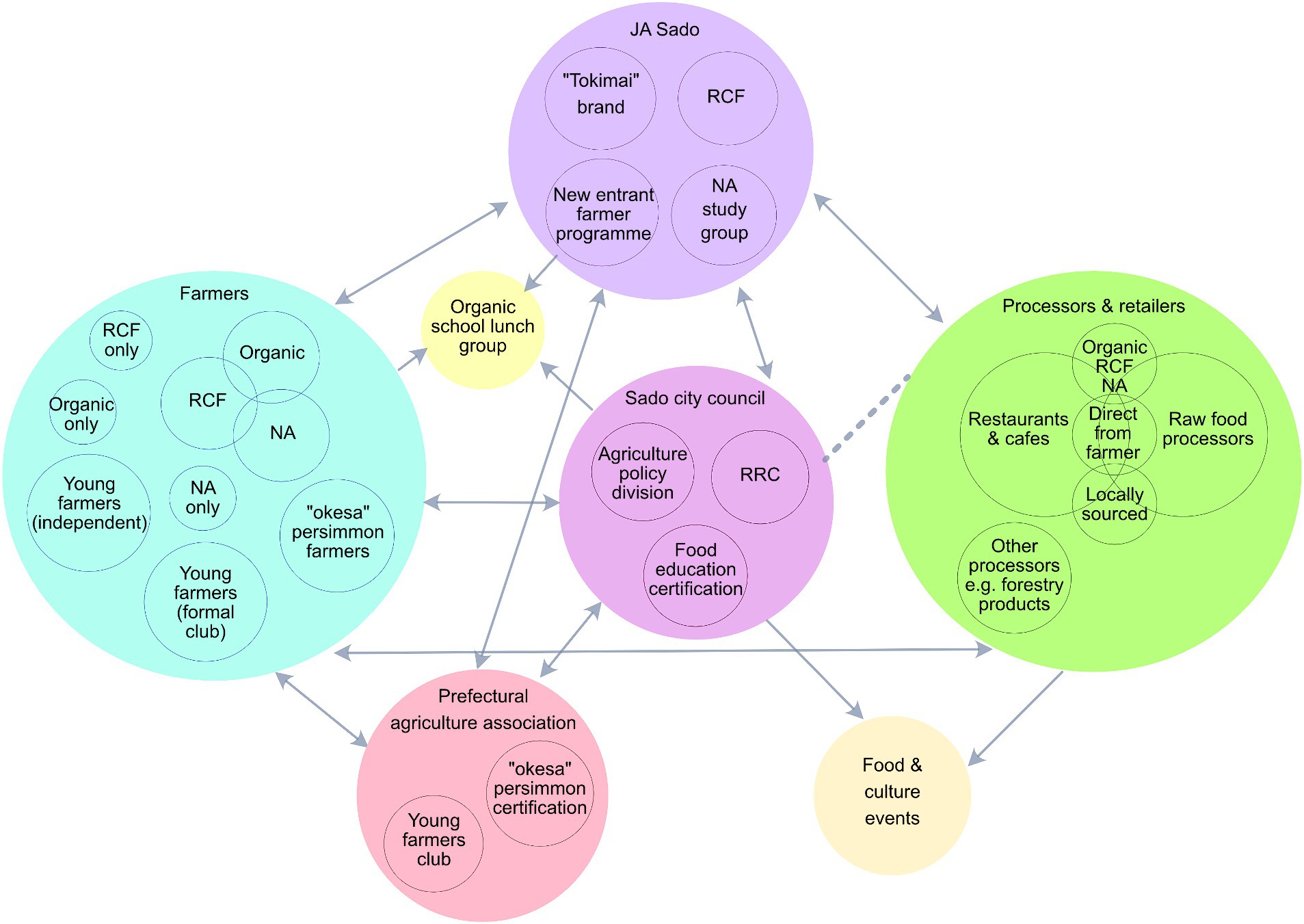

Figure 3. Schematic of Sado’s AFN as of experiential and interview analysis. The bubble sizes show that the farmer, processor & retailer groups are the most important to each other, whilst they place less importance on JA Sado, Sado city council and the prefectural agriculture association. Most connections are strong and reciprocal, shown by the grey lines, however the dotted line denotes a weaker relationship. Organic school lunches and food & culture events are included to illustrate important activities for the farmers and processors & retailer groups.

After evaluating the interviews and experiential research, a workshop was held to present results and engage in discussion around three key themes arising from them (what local consumers in Sado want from farmers and processors, how to strengthen Sado’s food network, and how to create a new image of farming for Sado). The workshop was held in Japanese by the author with two bilingual Japanese-English speakers present to help facilitate and verify the results following the workshop. Discussion ideas were written by participants and comprehensive notes taken by facilitators in real-time at each table during the workshop. The workshop served as both a validation of the results and as a step toward enhancing Sado’s AFN. Participants totaled 22 (Table 4), 11 of which were previous interviewees (five farmers, two food processors, two Regional Revitalization Corps Officers (RRCOs),2 one representative of JA Sado and one local university associate professor). The remaining 11 participants included Sado city council representatives, Sado “furusato nōzei”3 (ふるさと納税) promotion manager, and several other food processors and farmers.

Inspired by Kallio and LaFleur (2023), I start with a personal vignette from my time immersed in Sado’s AFN. This experience included undertaking farming, participating in food events, helping to sell produce and find buyers, help to set up community spaces and be a performer at local traditional arts events. In tangent with the interview data, the vignette acts to create a more rounded, sensual, and rich account of Sado’s AFN. This aids in better understanding its personality and atmosphere. The following section gives an overview of Sado’s AFN to set the scene for the subsequent two sections which describe the response of three sets of interviewees: farmers, food processors and retailers and other actors of importance to the food network. These sections are split into the main themes that arose from the interviews. The discussion then considers the responses of the interviewees in light of what can be learnt from Sado’s AFN for other areas, as well as how it can find ways to progress and strengthen into the future.

From my 1 year of immersion in Sado’s AFN, seeing the efforts of different actors come together to create numerous community food and culture focused events left a deep impression. These events blend tradition with small but radical acts of sustainability, in a society that has a lower awareness of sustainable agriculture than might be expected (organic only accounts for 0.2–0.5% in Japan compared to 1.4% globally), Willer and Lernoud (2019) and Miyake and Kohsaka (2020). As I experienced these active communities as a participant within them, they became more nuanced, and as a result I felt the need to support them became more pressing.

“As autumn leaves began to fall to the ground, I picked rosy ripened persimmons in orchards covering the mountain slopes. We took them to the small cottage-industry sized factory to peel and chop them for drying, packaging and selling. With a group of young U and I-turners, I helped move truckloads of rubbish from a vacant property they were transforming into a guesthouse for new young migrants interested in farming. As the spring buds began to emerge on branches, I squeezed freshly fermented soy sauce through a traditional wooden press with a group of neighborhood friends. I listened to careful observations of how it was saltier, a deeper umami flavor than last year, the beans still retaining their shape despite the fermentation process. As summer began to bloom, I walked with a local expert and groups of families around paddy field verges and forests to pick wild herbs to make teas and balms together. With a group from one of the local shrines, I was privileged to spend one full moon-cycle of evenings learning a ritual dance to clear out bad energy and pray for a rich harvest come autumn. As summer began to cool, I called out to customers “いらっしゃいませー!(irasshaimase-!)” in the local produce section of the supermarket selling organic mushrooms a farmer friend had grown. As the leaves began to turn color again, I harvested bundles of rice tied with string and slung them over bamboo frames to dry, the traditional way. Outside of Sado’s AFN, I also observed how farmers sprayed fields with farm chemicals, cut grass verges unfailingly and burnt farm waste in open cold air, smoke hanging low across the valley in acrid swathes.

I was finding that through my interest in the people, their work and the culture here I was being invited to be a real acting part of the system. Treated not as an observer-outsider looking in, but an opportunity to give time, skills, knowledge. To be a part of the community. Participating in mixed food and culture events, I could see the networks of processors and retailers making time in their already busy schedules to come together, plan and carry out these events, countless times throughout the year. The community, resilience and flexibility needed to do this so continuously became very apparent. It is a real source of inspiration and hope that such energy could be put toward increasing the environmental sustainability of Sado’s AFN.”

– field diary reflections of a year’s experiences participating in Sado’s AFN.

Figure 1 shows Sado’s AFN farmer types divided into organic, RCF and NA, highlighting the different sales channels which these farmers use. Some farmers mix both their practices and sales channels, while others only use one type of practice and may only use one sales channel. Interviewees considered selling to online sales platforms which show their farmer profiles as a form of direct sales. Figure 2 shows a schematic of Sado’s AFN food processors and retailers who overlap in their use of organic, RCF and NA raw ingredients, which they try to source directly from local farmers. Figure 3 illustrates Sado’s AFN, comprising of farmers, food processors and retailers, as well as other key actors connected to these two main groups including JA Sado, Sado city council and educational institutions. The left-hand side illustrates the overlap of organic, NA and RCF (specifically for rice production), for which most farmers use a mix of these three methods. Fewer farmers undertake only one of these practices. It also highlights that there are different groups of young farmers – both individuals who have informal knowledge sharing groups, and others who belong to formalized groups. A further subgroup of farmers undertake a regionally certified production method of persimmon growing named “okesa persimmon” (“okesagaki” おけさ柿). Although there is less chemical reduction involved than the RCF rice, (due to farmer feedback of pest and disease damage to fruit) farmers are encouraged to try and reduce chemical use, make, and use organic compost. The right-hand size illustrates the food processors and retailers (restaurants and cafes) in Sado’s AFN. Many of these interviewees do both retailing and food processing, such as running a restaurant while serving home-made fermented pickled vegetables and jams, shown by the overlap. Farmers and food processors and retailers have strong connections as they sell, buy, and give produce. Some processors also encourage farmers to grow more produce for their processing needs. JA Sado includes several subgroups, including the tokimai brand, RCF, a NA study group for all interested or practicing farmers who are members of JA Sado and a new entrant farming program. Many farmers are members of JA Sado, some to sell their rice to them as well as take advantage of information and events, and others just for the knowledge. Some food processors have connection to JA Sado through the events it organizes for organic and NA farmers, so that they can learn about production and make new farmer connections who may be able to produce more raw ingredients. Sado city council has a dedicated agricultural policy division which consults on policy from and to regional and national government from the local level and collaborates with JA Sado on programs such as the tokimai brand. It also has sectors which oversee food education certification as well as a regional revitalization corps (RRC) section, which often overlaps with aiding farming issues in each locality. The agriculture policy division and RRC have direct connection to farmers as well as through JA Sado. Food processors and retailers have links to Sado city council through the RRC and food education, but also through subsidies to start-up new or revitalize existing businesses. The prefectural agriculture association hosts a young farmers club and leads certification on the okesa persimmon certification. It directly connects to farmers through these channels, as well as to JA Sado and Sado city council. Interviewees covered all the groups shown in Figure 3, however it is not necessarily a complete picture of Sado’s AFN, as other elements such as forestry and fisheries were not included as part of the research. The right-hand column of Tables 1, 2 (detailing the farmer and food processer and retailer interviewees), gives a brief description of the extra activities which feed into the AFN as undertaken by the interviewees. These activities are referenced in the text below, providing insight into the overview of Sado’s AFN.

While 20% of rice paddies in Sado produce under the tokimai brand (Toyoda, 2021), which is a noticeable extent of farmland, it is apparent that the majority of farmland is under conventional production methods. A smaller area is under organic and NA, (for example those farmers interviewed in this study). It became apparent from the interviews (see results below) that farmers (whether rice, vegetables, or fruit) struggle to produce using organic and NA methods in part due to the surrounding conventional farmers complaints which are said to stem from their perception that such methods increase pests and disease, and make the landscape appear “untidy.” It is therefore apparent that sustainable production methods including the tokimai brand, organic and NA are in the minority and acting as the “alternative” food network to the majority conventional production in Sado. RCF production can be seen as a bridge between the mainstream and alternative food network in Sado – being a part of both systems. This bridging position can be seen in the production methods (reducing chemicals is a route toward organic or NA) and in relation to the production area and distribution (while the majority of rice production is done by conventional agriculture, rice distribution by JA Sado includes a large proportion of RCF rice, and so this can be seen as part of the mainstream food system).

In other regions of Japan, such as in Hirakata, Osaka prefecture and Iga, Mie prefecture AFN’s use a vegetable box scheme and “teikei” approach (a co-partnership between consumers and producers with direct distribution) using organic principles (Kondo, 2021). Similar systems in the West can be found, for example in the UK the Community Supported Agriculture network acts to assist consumer-producer co-partnership systems, and a variety of box schemes can be found across Europe (Kummer and Milestad, 2020; Bonfert, 2022). In contrast, Sado’s AFN does not include teikei/CSA or box schemes but instead consists of a number of individual RCF, organic and NA farmers, selling either through JA Sado or via direct sales channels, mainly to those in mainland cities.

It is evident in speaking with many of the interviewees, alongside participating in events in Sado, that there are several reasons that they chose to live there and work in the island’s food network. For many I-turner interviewees, this is a combination of several elements: the receptivity of the existing community on the island of both new-comers and those having lived their whole lives in Sado (the receptivity of the latter can depend upon the community); the natural environment that it offers (a return to nature often from an urban area); the ability to source local, fresh ingredients; the culture, which is rich in traditional arts events supported by local food retailers; and the opportunities available as somewhere which has relatively low population compared to urban areas of Japan. In particular, regarding processor and retailer interviewees, these elements, combined with support for business development in the form of subsidies, create an ideal place to relocate and start-up a business. For many I-turners, previous to deciding to move to Sado their connection to it had been almost non-existent. Food processor interviewee 7 explained that they had traveled throughout Japan to find an ideal place for relocation, and the feeling of community had been strongest in Sado. This was a major (but not the only) factor for them in choosing the island. Conversations with other migrants on the island revealed similar journeys. Barriers that may occur with being an island (especially for exporting and importing to the mainland) are therefore of less importance. Similarly, for U-turners, the opportunities to develop their own farms and food processing businesses alongside existing familial connections creates an ideal situation from which to begin. Despite this, it is not without its issues, such as lingering conservative attitudes to farming (e.g., “neatness” of fields and beliefs around pest invasion from organic and NA farms) and the need for more capacity in networking and knowledge exchange.

With more people relocating to Sado in recent years, many new entrant farmers and eateries have begun to regenerate several areas. While not all of these are undertaking sustainable practices, there is a focus on producing and serving local food from what is perceived as a rich natural environment. There is therefore scope to increase the sustainability of these new businesses through Sado’s existing AFN.

From conversations and experiences with different communities in Sado, it is apparent that there is much complexity within the AFN. Communities and identities form (new ideas), brink on the edge of extinction (loss of successors), clash or meld together (conflicts or alignments in different farming practices and beliefs). This depends upon the culture, social norms and philosophy of the people. There is a mix of farming and sales practices. Some new migrant farmers may use pre-industrial sustainable agriculture techniques such as NA, while selling their produce mainly outside of the island to large cities such as Tokyo via online channels, as these customers have a greater awareness of sustainable production methods and can afford to pay a higher price (which is profitable compared to local sales despite transportation costs). Other farmers reject pre-industrial techniques due to the perceived need to grow “high quality” produce (no blemishes, regular shapes etc.) and greater quantities, while selling mainly to local markets in Sado. Some try to reduce farm chemical use and sell through a variety of channels. Some food retailers, such as restaurants and cafes try to use local produce, although it may not have been produced in an environmentally friendly way. Others seek to source ingredients that are sustainably produced but have to be shipped to the island, while trying to collaborate with local farmers to produce more organic and NA raw ingredients.

There is a strong bond of friendship and comradery within a group known locally as the “seven samurai” farmers, including farmer interviewees 1, 13 and 18, who practice a mix of organic, NA and RCF. They regularly contact each other to consult on their progress of farming, weather, pest, disease and other issues throughout the year. This was apparent in interviews as well as through attending both formal farming meetings and informal gatherings. Organic farmers surrounding this inner group also like to connect and share information with other organic farmers both on and outside the island. They are self-motivated to learn individually and together. In contrast, those that farm solely with NA methods – such as interviewees 5, 11 and 15 – explained in the interviews that they preferred to find their own individual methods, through taking inspiration and learning from reputed NA masters and then observing the results of their own actions on the farm. They often spoke of a strong philosophy behind their practices, and indeed their lifestyles, in trying to make a minimum negative impact upon the environment.

Interviews with food processors, restaurants and cafes highlighted that they are relatively well connected to local farmers. Food processor interviewee 3 who produces fermented soybeans tries to source all their soybeans locally and organically, however the demand is greater than the supply. In this case they have created connections with organic and NA farmers on the island who they do not already buy from and are negotiating quantities and prices for their use in processing. This requires close local connection and a bond of trust, through knowing the farmers already or being introduced by a trusted intermediary. Such connections are vital in order to make local food processing an economically viable and environmentally sustainable business. Food retailer interviewee 7 is attempting to grow vegetables for use at their restaurant with the help of local friends and acquaintances, while also creating close neighborhood connections and informally receiving fruit, vegetables, meat and wild mountain forage for restaurant use. The interviewee related that such connections and the local food served give the restaurant more value to its customers.

Food processor interviewees 1 and 7 specifically related the importance of community in their work – creating a place for connections between local and visiting people to happen organically and events to be held, rather than being focused on creating profit as a business. Food processor interviewee 1 runs a sake company, from which the profits, as well as waste products, enable them to run a café which aims to create human connections as well as people to food connections, through using local ingredients. Food processor interviewees 1, 7 and 8 also related the importance of using their café spaces as places to hold workshops for the community to pass on important knowledge about plants that grow locally and their uses. Food processor interviewee 4 and farmer interviewee 1 stressed the importance of employing disadvantaged local people, providing them with environments that are not stressful but are instead flexible. These aspects of community care strengthen both local relationships and connection to nature on the island. They are a way to create new connections, strengthen existing ones, foster trust and understanding toward other humans and other living beings.

A remarkable point about food networks in Sado is the number of events that are run throughout the year, mostly from spring through until winter. At the busiest times of year such as summer, events can be run on every weekend. These events vary in their contents; however, a common purpose is to bring together the community. Many of these events are restaurants, cafes and processors coming together to collaborate under a theme, while others are in combination with local traditional and/or modern arts and culture. While there is an appeal toward tourists, many of the events cater toward the local community, maintaining and strengthening the connection between the food retailers and processors. Some themes of the food events that I have experienced while living on the island have been around conscious food choices (two vegan events), otherwise they are mostly to promote local produce and new food processors (local fermented foods, locally made baked goods, special collaborations between different food processors or retailers etc.) The promotion of local food often occurs in combination with cultural events, which through personal observation and conversations with local people is evidently an important aspect of the island’s identity. It is also a source of enjoyment for the food processors and retailers who are part of these events.

Farmer, food processor and actor interviewees expressed the importance of fun and enjoyment that they held and needed to undertake their work. This sense of fun has similarities and differences across the interviewees and is likely to be connected to their individual contexts and goals, which may also change over time. They can be categorized as: a sense of accomplishment/realizing a goal of working how they want to; aligning with their values (e.g., living in harmony with nature, creating positive opportunities for others); having fun in compensation for low wages; being in and creating community; being motivated toward a personal goal and that which has wider resonance for nature and community.

If the image of farming is only of hard work and low returns Japan and Sado’s farming network is likely to keep declining. For farmer interviewee 4, fun in farming is partly being able to share doing it with friends, while expanding their friendship and the farm’s capacity by running farm experience and traditional culture dance and music events which bring city-dwellers to Sado. They are also in the process of setting up a guesthouse for both transient and more permanent farm helpers. Through this, some of the city dwellers have moved to Sado to help on a more regular basis while simultaneously having other jobs. For interviewee 4, this shared farming model lessens the labor of farming, creating capacity and therefore enabling them to do more natural farming methods to feel a sense of being in harmony with/working alongside nature. Further, the sense of achievement they feel in providing an opportunity for people to experience being in nature and producing healthy food for customers is source of fun. These young entrants to sustainable food production want to be able to live in co-existence with nature without the traditional hardship image of previous generations.

Farmer interviewee 2 and 18 had a sense that although life is hard as a farmer as they work long hours and do not receive a wage that corresponds to this, there is a sense of fun gained from working through the challenges of farming and the achievement of producing food that customers enjoy. Fun for these farmers is also created in sharing practices and challenges with their close farmer friends, as being able to do this as a group creates a sense of community and motivation.

For farmer interviewees 11 and 12 who mainly work independently, their sense of fun comes from the accomplishment of creating healthy produce through their own sustainable means. For interviewee 11, this is through having a permaculture mindset and creating a system within the landscape, even if small, where everything is connected and resource cycles flow. While they are working on achieving this, the potential of realizing it is motivational which also brings a sense of enjoyment; however, they would like to be better connected to other actors which would provide a sense of community and therefore more enjoyment.

For processor interviewees 3, 4, and 8 the sense of fun comes from having realized a life goal of setting up independent businesses where they can source sustainable ingredients such as organically produced soybeans and wild herbs, sell healthy produce and therefore contribute to a more sustainable society. Processor interviewee 4 further employs disadvantaged people, which gives them a sense supporting local community and enjoyment through this.

Actor interviewee 6 and 7 related that their sense of fun comes from working on projects that lead to positive opportunities for others in the food network, while undertaking work that they enjoy (actor interviewee 7 has been able to employ their illustration skills in creating advertisements about the local direct food sales shop).

Table 1 describing the farmer interviewees shows a mix of age ranges, between 35 to 75. Most interviewees were between 40 and 45 and had either made an “I-turn” or “U-turn” (for U-turners, the minimum amount of time out of Sado was 2 years). This shows a trend in younger people making a move to a rural location (I-turners had moved from urban areas). Initially for farmer interviewees 1, 5 and 7, this move was not specifically to undertake farming but to be closer to nature. Through finding work once in Sado, farming became a viable option and then a passion. Table 1 shows that there is a mix of sustainable farming practices in Sado, including RCF, organic and NA. There are also two main sales channels, one through Japan’s biggest agricultural cooperative JA (JA Sado branch) and the other through direct sales. Most farmers use a mix of farming methods as well as sales channels, although there are some that only adhere to one farming practice and or sales channel. This highlights the “messiness” of farming in Sado’s AFN; there are farmers who mix their practices and farmers who focus only on one production method, e.g., NA.

Throughout the interviews with farmers, food processors and representatives of JA Sado and Sado city council agricultural policy division, there were some consistent common challenges that arose. These included an aging and decreasing rural population, especially regarding successor and new entrant farmers, an ensuing abandonment of farmland and houses, several barriers to farmers converting to organic or NA methods and a decrease in consumption of the main crop (rice) in favor of newer foods such as bread. These challenges are not particularly unique to Sado but can be found across Japan (McGreevy et al., 2021).

Despite aging and decreasing numbers of farmers, both JA Sado and Sado city council offer opportunities for successor farmers and new entrants to access farming on the island. JA Sado offers a “New Entrant Farming Programme” (就農研修制度 – “shūnō kenshū seido”) which gives farmers training with expert farmers on the island over three years, provides them with employment in JA Sado, community housing and potential financial aid with rental payments, as well as support for those migrating to the island. JA Sado then gives three years of follow-up advice support for those who have undertaken the program. Farmer interviewees were also appreciative of the capacity that JA Sado and Sado city council provide in terms of organizing farming events where farmers can come together to learn and exchange information. Further, Sado’s population of young farmers are also able to connect through the “4H Club”, a nationwide initiative organized by each prefecture to sharing learning, knowledge and issues. More broadly, for migrants to the island, Sado city council offers reduced price accommodation for up to six months in which more permanent accommodation and work can be found. However, despite these efforts, new entrant farmers are still regarded as too few by the interviewees. Many of the interviewees thought that this was due to a lingering negative image of farming as being hard work, receiving low wages and living in the countryside as having obligations to the local neighborhood (集落 – “shūraku”) as well as a general lack of entertainment compared to city life.

New and successor farmers are either given land for free, for a low price or inherit their parents’ land. Often this land is very small, and some young farmer interviewees related that it can be an issue for making enough money to live from. In previous generations in Japan, there was a culture of farming for the family and selling whatever is extra, creating a culture in which other work (sometimes several jobs) are also needed. Many of the young farmers interviewed were being asked to take over more land from those retiring or giving up farming. While this means that they can grow their businesses, often this land is in small parcels far from their existing land and so can make it difficult to manage. Social relations can also be a key issue in acquiring new or more land, as farmers want to know who they are passing land on to so that there is a bond of trust and assurance that the new farmer will not cause offense to those in the local neighborhood. This can mean having to stick to rigid social norms around farming that the previous generation has pertained to, such as cutting grass verges around paddy fields at regular intervals, as well as applying farm chemicals. Even on grass verges organic and NA farmers face pressure to apply chemicals and cut the grass very short (as close to the soil surface as possible, usually less than 5 cm above the surface). These practices are seen as keeping the neighborhood clean and tidy and part of the responsibility of being a local inhabitant. For many new farmers who want to practice organic and NA this can create a problem. Organic and NA farmer interviewees said that to escape this problem, they often acquired land away from others, in the mountainside. They pointed out that this is inherently more difficult to farm in terms of access than land below the mountains, as found in other studies of Japan’s rural areas (McGreevy et al., 2021).

Organic farmers, especially the “7 samurai”, are championing organic farming in more open, flat lands within the main farming basin of Sado, however. They have formed a NA research group organized by JA Sado as well as an initiative to supply local nursery schools with organic lunches. These farmers had a history of championing the tokimai brand to reduce farm chemicals and increase biodiversity, and so they are well known on the island as farming pioneers. Despite this, many farmers are still finding it difficult to convert to organic and NA practices. Farmer interviewees, JA Sado and informal conversations with non-organic farmers at local farming events say that this is due to the great variety of pests in Japan and the coping with a reduced harvest during the first few years of conversion. Interviewee 2 expressed that conversion compensation for yield losses was not enough. This is compounded by social pressure of surrounding conventional farmers. Interviewee 2, one of the “7 samurai” farmers, acknowledges the importance of this like-minded friendship group in providing support to each other and swapping farming experiences to continue with organic and NA practices, especially under the pressure of opposing social norms.

Farmer interviewee 2 related that they had a good relationship to the current mayor of Sado, based on the mayor’s interest in furthering organic and NA and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Sado. They expressed that they thought it was important for the mayor to have this outlook, in contrast to JA Sado, (who they think has a greater focus on farming production and profit) as the latter are more biased by the need to make a profit. Other farmers, such as interviewee 1 stated that despite the mayor’s focus on the environment, the city council needs to think more about the long-term future of farming in Sado and provide more financial aid, especially for young families.

JA Sado provides support to farmers who are members, including organizing knowledge exchange events and seasonal information on the farming schedule. Only two of the interviewees are not members of JA Sado (interviewees 5 and 11 who are NA farmers), citing that the costs of being a member are too expensive and they prefer to source their information independently. Interviewee 2 related that they find knowledge exchange events very important for having time to learn and talk with other farmers, and they recognize the importance of the capacity needed to organize such events. Having a body with the capacity to continue supporting the organization of such events was seen as necessary and important for the continuation of sustainable and alternative farming practices in Sado. JA Sado’s main focus is on conventional agriculture, and so being a member with a focus on organic and NA, farmer interviewee 4 also found that a lot of the information they pay for as a member is not necessarily applicable. As a new entrant, they further expressed a need for a basic information handbook on how to begin NA farming, as most of the information in the NA study group was too advanced and exchanges with other farmers proved confusing due to the variety of individual methods employed. Other farmer interviewees, such as interviewee 10 and 18, expressed a need for more events developing knowledge for growing vegetables, which they felt unfamiliar with but want to grow more of, especially where organic school lunches are concerned.

Another key issue expressed by many farmer interviewees (1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 15 and 18) was the ability to get labor. Interviewees 1 and 6 stated that they thought it was particularly difficult to get skilled labor. The seasonal nature of a lot of the farming work is also problematic, and interviewee 1 suggested that working through non-farming season in tourism, with help from the city council for training and work opportunities would help with this issue. Farmer interviewee 6 and 11 have been able to connect to labor resources through interviewee 15, as well as other local resources such as hiring companies (farmer interviewee 1 noted that these come at a price which can be difficult to pay) and international voluntary services such as “World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms” (WOOF). However, skilled labor is not guaranteed. Interviewee 6 also makes the most of local connections through a hostel in which they can host labor from the WOOF program, and to which they sell their rice. Further, farmer interviewee 16 is making connections through agricultural universities to advertise working holidays in farming for students.

One group of young farmers (led by interviewee 4) uses an innovative approach to decrease the pressure of farm labor and increase the fun in farming. Interviewee 4 is a farmer descendent, and working alongside acquaintances and friends from the island they have expanded their workforce through a model in which the workers help in the areas of farming that they want to and do other work that they want to the rest of the time. Through selling directly in city markets and using SNS they have been able to recruit interested individuals. Most of these workers also run their own small businesses / cottage industries or work for other local businesses, which was expressed as “plus alpha.” The young lead farmer here advocates that this model allows everyone to enjoy farming, while not having to rely on it as a sole income. They are also able to share their own farm workload while not needing to pay all the workers full-time wages, which they would not be able to afford.

In terms of funding for organic and NA, farmer interviewee 2 expressed that although they were able to receive funding to compensate for reduced yields during the three-year conversion period from conventional farming, it was not enough when compared to what farmers in the EU can receive. Despite this, with the new green farming plan, they have hope that the government will change its policy to provide more financial support for conversion to more environmentally friendly farming. In addition to this, farmer interviewees 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 17 related that they think the current financial aid given to farmers in the form of basic subsidies is not enough – for example it does not help to cover the costs of machinery repairs, which can be very costly. Farmer interviewee 2 estimated that farmers only receive 60–70% of what they actually need, and after receiving subsidies once it is normal for them to be refused a second time. Farmer interviewee 4 also mentioned that more focus should be put on creating a local circular economy, where more money from locals is spent on local produce. Farmer interviewee 1 noted that although JA Sado can provide assistance with subsidies, as a business their need to make a profit means that equipment and organic fertilizer is often actually more expensive than that sold at home centers and other outlets. Actor interviewee 1 agrees that funding is inadequate and often farmers have to have another job.

Many of the farmers interviewed sell at least some, if not all, of their produce on the mainland through direct sales (see Table 1). They related that this is due to there being little awareness or knowledge around organic and NA in Sado, and that local people would not be able to buy at the prices that they sell. They would like more support from local consumers. In particular, interviewees 2 and 4 spend a lot of time advertising the benefits of their production methods through social media, television and attending consumer-facing events. Some farmers, such as interviewees 4, 5, 11, 15 and 18 do not certify their produce as organic due to the high costs and instead prefer to interact with customers more personally so that a level of trust is built on which certification is not needed. Despite a low awareness of organic and NA farming, anecdotal evidence from living in Sado has provided evidence that there is an appetite for local produce. The JA Sado cooperative stores, direct-sales shops and other chain store retailers sell local produce including rice, vegetables, fruits, and locally processed foods, albeit not labeled or certified as organic or NA, but with the farmer’s name. This produce can sell out fast, especially when stock is low, and so there is an evident desire for people to buy locally and likely from farmers they know personally.

Farmer interviewee 1 expressed the desire for JA Sado to do more marketing, promotion and sales of the produce, so that farmers have more capacity to focus on the quality of their farming. Farmer interviewee 12, actor interviewee 1 and 5 expressed that it is expensive to sell through JA Sado as they have less negotiating experience against retailers and so would prefer to be able to sell more of their produce directly or through another channel. Similarly, interviewee 11 has found sales difficult and would benefit from someone who is able to create connections to retailers and consumers so that they can focus on farming. Interviewees 3 and 14 talked about the need to gain more training and opportunities to understand customer demand. Some interviewees (2, 4, 6, 8, 18) use their skills – whether experienced or limited – to advertise their produce through social media, having found that this is both a good opportunity and that other avenues of support, such as JA Sado, are limited.

Table 2 describing food processor and retailer interviewees shows that the interviews are relatively young (mostly in their 30s and 40s) and have moved to Sado as I-turners. All processor and retailer interviewees sourced at least some of their ingredients locally, directly from the producer and from farmers using organic, natural agriculture or reduced chemical farming methods. All processor and retailer interviewees also used natural methods in their processing methods, (at least to some extent, if not for all their products, e.g., one restaurant owner serves some pre-processed food with chemical additives).

For processor and retailer interviewees, farmers, other local businesses and food system actors have been vital in obtaining resources such as raw produce, sharing knowledge and in having a community. Processor interviewee 7 expressed the importance of personal relationships and compatibility in deciding where to set up a life and business, as well as in making good community for alternative food networks. They have found a deepening of relationship with repeat customers and have made connections to farmers for meat and vegetables both nationally and locally from such connections. Processor interviewee 1 expressed the need for more capacity from local government to create stronger networks across the island and beyond. This interviewee recently opened a café as part of their drink processing business, for it to be a space in which local and visiting people can meet, exchange ideas and network. They also organize annual events such as seminars, workshops and tasting experiences to bring together knowledge from outside and within the island to expand people’s thinking, ideas and perspectives. They are also looking to expand into other ventures and need to be able to connect with people and businesses who have specialist knowledge. Despite their efforts in creating local, national, and international networks, processor interviewee 1 still feels a need for greater networking from an institution which has more capacity. Anecdotally, this is a position which the local council is considering developing, and which would benefit local businesses if done well through acknowledgement and understanding of current networks which can be built upon.

Processor interviewees 2 and 3 share a concern in trying to find more NA farmers to supply environmentally friendly grown crops to expand production. Currently, the former uses 15% NA raw materials, with the rest locally produced but not through organic or NA. The latter is proactive in connecting to and negotiating with local farmers directly, as well as with JA Sado to attend farmers meetings a present about their produce needs and business aims.

Most interviewees who had set up new retail businesses said they were satisfied with the level of support received from Sado city council, which included grants to help refurbish buildings for use as restaurants, cafes and for small cottage industry processing of food. Without the grant funding on offer, many said it would have been difficult to establish new businesses. Interviewee 4 commented that it was important to be able to receive funding for different aspects of the business, which they had been able to do, and for the funding to be flexible. Others, such as interviewee 3 and 8, thought that it may be difficult to get the subsidies again or presently, as the amounts available have reduced. This may cause a serious bottle neck for other local businesses starting-up.

In terms of business development, sales and advertisement, interviewees were happy to find connections themselves, e.g., through the use of the internet or friends and acquaintances, for example in learning how to process food, finding a designer for creating branding and doing marketing themselves through social media. Therefore, there was little perceived need for institutional aid regarding this side of business development, which contrasts to farmers who expressed a need for help with sales and marketing. However, processor interviewee 4 expressed the need, similarly to farmer interviewee 16, to be able to understand customer preferences better, improve customer relationships and develop their markets. Interviewees often use events as an opportunity to do this, but some would like to have a more rigorous approach such as undertaking surveys, however they need more skills and capacity to do this.

Table 3 describes the other food network actors interviewed in Sado. These actors come from a mix of institutions including Sado city council, JA Sado and education. These institutions have inherent links to the food network as well as having important personal relationships to farmers and food processors and retailers in Sado. From observation, much of the work they do is in direct partnership with farmers and others working in landscape management, and they can give capacity for knowledge exchange events, future visioning and practical work in the field. Half of these actors have always lived on the island, and the other half are I-turners, all of them are relatively young (between 25 and 45).

Actor interviewee 1 of Sado city council agricultural policy division, actor interviewees 2 and 3 of JA Sado and the JA Sado NA study group related that they work together to help farmers with subsidy applications and payments, co-creating and distributing information, branding and media broadcasts. They also translate policy and feed innovative environmental farming practices from Sado to national policy makers (in recent years there has been particular interest in the tokimai brand to support the government’s new Green Food System Strategy – みどりの食料システム戦略 “midori no shokuryō shisutemu senryaku”). It is therefore evident that Sado city council plays an important role in Sado’s food network in working with farmers and JA Sado.

To make use of abandoned fields, JA Sado has come up with an initiative to grow flowers in these areas. Actor interviewee 1, along with other farmer interviewees, find it difficult to adapt to this as they do not have the experience. This highlights a mismatch in understanding and friction between JA Sado and farmers, who have expressed frustration at being requested to undertake this work.

Actor interviewees 6 and 7 work for the city council as RRCO’s and have a focus on landscape management and added-value local food processing, respectively. They have been particularly involved with helping farmers manage areas of abandoned rice fields for increasing biodiversity and the crested ibis and revitalizing traditional food processing methods. They are both I-turners and want to encourage other people to relocate to Sado, although they think there is still an all-pervasive message for young people to go to cities for more convenience, a better lifestyle and more job opportunities. Their role as an RRCO has allowed them to explore Sado’s rural challenges and opportunities as well as making a large network from people of different sectors. From this, they have tried proposing various solutions, but have felt that there is a generation gap in mindset and societal norms, such as less experienced staff not being perceived as wise enough to make suggestions that could be realized in the workplace and real world. Actor interviewee 7 also found that communication between local actors was unclear leading to mismatched expectations, friction and project failure. Actor interviewee 6 would like to create more job opportunities and a circular economy in Sado and are thinking of ways to create an online, ongoing database of resources currently available in Sado (e.g., vacant houses) and historical assets (e.g., what vacant shops used to be, who they were connected to, why they stopped being viable etc). They think that this could help people in the initial stages of relocating to Sado to be more equipped to start a way of life in this rural area. Through their networks to the local university and their research connected with a national big data venture, they are scoping ways to realize this project.

Actor interviewee 4 expressed that they think the general consumer awareness of environmentally friendly farming and wider sustainability issues are low in Japan in comparison to other areas of the world such as America and Europe. This creates a lack of support and a smaller market for such farming practices. They also thought that part of the reason for this was that the Japanese government still focuses on productivity in farming, rather than environmental sustainability.

In terms of food processing, actor interviewee 5 related that Sado has very few processing facilities, which may be due to people’s preferences to eat fresh. They think that this would help to decrease food waste, and that the council is looking for investors to help create such facilities. However, there are several informal neighborhood and friendship groups also continue to produce traditional pickled vegetables together or individually at home. For such groups, this practice creates a strong sense of community and identity through collective sustainable action. More facilities could help create increased opportunities for such sustainable activities and grow the AFN.

Actor interviewee 5 works with various communities in Sado related to both education and primary industries. They have learnt through this work that farming still has an undesirable image as a career path, which can stem from capitalist values. This interviewee expressed that they think there is a need to change values and increase awareness about the importance of environmentally friendly farming. They noted that it is important for farmers to be willing to change and that many of the older generations do not have the motivation to change their practices. Actor interviewee 1 related that at a farming meeting in Tokyo during 2022, due to the efforts for reducing farm chemicals in Sado and the specific tokimai brand, it was suggested that farmers who have a “unique” or environmentally focused attitude to farming should go to Sado to learn or farm there. This suggests that Sado is renowned nation-wide as pioneering in more environmentally friendly farming and can be a positive place for farmers wanting to learn such practices. These two opposing but co-occurring situations show the complexity of the farming community, but also that there is hope through the pioneering farmers in Sado in guiding the way for younger entrants.

Regarding generational knowledge, actor interviewee 1 thought that JA Sado’s new entrant farming program was good for passing older generations intuitional knowledge to younger generations, but that there needed to be more farming mentors. JA Sado teaches farming in schools, while actor interviewee 4 related that schools teach children to grow vegetables, sell these to a local café and create recipes with them.

Part of the marketing for the tokimai brand is a JA Sado project to involve the public in rice farming by annually planting and harvesting a field of rice designed into a picture created through a competition by school children. The interviewee related that JA Sado also teach about farming and food in local schools to motivate younger generations to farm. They felt from experience that older generation farmers do not have as much motivation as younger generations, which is an issue in switching to more environmentally friendly practices.

The workshop held with 22 participants verified the contents of the interviews, while giving ideas for the next steps to progress and develop Sado’s AFN.

In the workshop, participants were invited to think from the perspective of local consumers to brainstorm how they might be attracted to buy more sustainably produced food. There was a strong opinion that local consumers want to buy food that is consumed daily at a low price, competing with that imported from other areas. Further, they felt that local consumers awareness of sustainable food is low, as previously related by farmer and food processor interviewees. Several ways of increasing awareness were suggested – making more sustainable food workshops available in Sado, focusing on advertising the health benefits of sustainable food so that it is directly related to the individual, better understanding what consumers want, and displaying easy to understand information about how the produce has been grown at the place of sale. Other ideas included creating a brand for Sado that expresses sustainably grown food for enhancing the environment (including produce other than rice, for which the tokimai brand already exists). Some farmer participants highlighted the difficulties of working as individuals and suggested coming together as a collective to help each other appeal to consumers, with the help of someone who has skills in marketing and finding buyers. Another idea was to create a community supported agriculture model, where local consumers commit to pay for a year of produce despite the amount harvested or creating a local economy system.

This theme developed from interviewees’ requests for further capacity in the network, to connect people and create more sales channels. A main request from participants was to have a network coordinator, preferably someone with a bird’s eye view of the AFN to create useful connections. Additionally, an online site where network information can be stored was voiced as important. From this participant’s experience, relying on one person as a coordinator creates vulnerability in the case that they leave the position, and the network knowledge is lost. There was a need expressed for more I and U-turners in Sado, who participants think are more open-minded and therefore can create more progression in the AFN. Through connections in the network, the ability to easily move between different seasonal jobs throughout the year was voiced as important for attracting labor and creating stable incomes. There was also a request for Sado city council to better understand the issues of the AFN in Sado and help in creating solutions.

This theme developed from the interviewees’ identifying that farming successors are very few and further declining, as young people leave the island to go to university and or find jobs on the mainland, often not returning. In the workshop, as in the interviews, the need for an image of farming as fun arose. Participants related that the meaning of fun for them, either as farmers or in doing farming experiences, was in the feel of moving your body daily in nature and having a good body condition from this work, being able to feel the soil, eating food that you produced together with friends, being able to realize your dream and do your own trial-and-error experiments, doing a job that allows you to really feel and having enjoyable work fully integrated into your lifestyle. Participants felt that a positive farming image could be advertised through these points. They further related a will to create a model example in Sado’s of a sustainable food system for other areas to imitate.

The collective results of experiencing Sado’s AFN over one year and the interviews with different actors within the network have highlighted several areas that the AFN could be better supported. They also illustrate how actors in other areas of Japan as well as internationally could provide support to AFNs. These will be discussed below in relation to other literature.

With the continuing decline of farming successors, as well as new farming entrants wanting to have a fun and meaningful career, it is apparent that farming needs to refresh its image. Interviewees, workshop participants and informal conversations highlighted that there is a persistent negative image of farming: too much hard work for too little reward, regarding both finances and fun. An image-makeover for Japan’s fishing industry is currently underway, supported by online businesses such as Yahoo,4 which could be a pathway for agriculture. While the government provides career pathways to encourage movement to rural areas, such as the RRC, there could be potential in running a more focused sustainable farming initiative, which promotes an enjoyable lifestyle alongside farming. This should include support such as readily available channels to sell produce through, independent of the JA Sado.

Better highlighting examples of rural work where those who are living out and creating fun experiences and lifestyles, such as farmer 4 and the two RRCOs, could help to encourage others to undertake sustainable farming and food processing as a career. Networks across Japan such as the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) project 農業女子 “nōgyō jyoshi” (farming girl) attempt to advertise new entrants and young farmers as having enjoyable and “cool” lifestyles, as well as encourage women into agriculture. Creating stronger links to such networks as well as emphasizing the importance of sustainable practices could help strengthen Sado’s AFN. Relating such stories in schools as potential career paths could further help build the future of the AFN, as advocated for by actor interviewee 5. It is notable and interesting that the notion of having “fun” is a key motivator for young farmers and rural migrants, as was expressed by farmer interviewees 2, 4, 11, 12 and food processors 3, 4 and 8. In other countries such as the UK, other parts of Europe and America, obtaining land and food sovereignty is a main driver and political mechanism to gain support for young new entrant farmers, with the personal joy of farming secondary to this (La Via Campesina, 2022; Styles et al., 2022; Landworkers’ Alliance, 2023a,b). Celebrating food sovereignty over trade deals and technology-focused policies would cast the net wider to attract those looking for meaningful work across a range of issues, such as actor interviewees 6 and 7 (La Via Campesina, 2023; Landworkers’ Alliance, 2023a,b). However, the Japanese government is currently focusing more on technology and trade policies, despite its new Green Farming Policy (Hisano et al., 2018).

Alongside image aimed at new entrants, building an awareness of sustainably produced food to consumers in Japan is also of vital importance. Many farmer interviewees expressed the lack of awareness or care of the Japanese public concerning the environmental and health benefits of organic, NA and RCF farming. A survey on Japanese consumer awareness in 2021 revealed that more than 38 percent of respondents did not know the meaning of the government’s “JAS” organic food label (Statista, 2023). This leads to a lack of market for such products. McGreevy et al. (2021) found that agroecological farmers closer to large urban areas tended to have more success selling their produce, therefore being situated on a largely rural island may cause extra difficulties. Alongside developing awareness, having the capacity to find retailers for products was often cited by interviewees as necessary. Food processor interviewees related the need for a greater amount of sustainably, locally produced raw materials. Their work in proactively creating direct farmer contacts who can grow the produce they need in Sado is resulting in strengthening and progressing the AFN for both farmers and processors.

In both the interviews and the workshop, greater capacity was cited as being needed to find buyers for farming produce, skilled labor, and a “connector” role across the AFN. Further, more basic information on beginning NA and organic practices for new entrants was called for. Highlighting innovative young farmers’ models, such as farmer interviewee 4’s “plus alpha” model, while providing connections between new entrants could enable farmers to have more capacity and a greater sense of enjoyment and lifestyle flexibility. Farmer interviewees 2, 4, 6, and 11 all commented that they would like extra capacity and financial resources for undertaking more specific soil tests, with which they could better understand the status of their soil – for example the communities of soil microorganisms. Farmer interviewee 11 also expressed the need for building the soil through compost and that a local community compost initiative would be beneficial, although they do not have the time to start this kind of project. Actor interviewee 6 expressed that they thought knowledge about the ability to live comfortably in rural areas could be made more available, for example, average rural wages depending on work, availability of housing etc. There was a further need for increased capacity in creating more local, regional, national and international networks to share information and knowledge. The need for greater capacity has been well cited in other countries regarding socio-ecological production landscapes and their management (Phuong et al., 2017; Urquhart et al., 2019; Black et al., 2021). Lack of capacity and resources has often been found to be a lock-in factor constraining the viability of sustainable farming (Plumecocq et al., 2018; Black et al., 2022).

Maharjan et al. (2021), McGreevy et al. (2021), and Zollet et al. (2021) showed that in Japan, existing “agroecological farmer lighthouses” and “communities (of practice) within the community” create capacity and support for new entrants, through sharing knowledge and developing practices together. In the case of farmer interviewees 1, 5 and 7, farming was a natural progression after relocating and subsequently searching for work. Alongside an image make-over of sustainable farming, urban to rural migration could be more proactively advanced through better advertising existing sustainable communities and new entrant farming programs. Workshop participants’ aspiration to create a model example of a sustainable food system in Sado could be part of progressing rural migration and an increase in new entrant farmers.

Food processor 1 has already set a good example of how others could create networks through organizing events and processing experiences, however they felt that more support was needed. As noted above it is apparent that Sado city council is aware of this need and is looking at developing a role. Indeed, institutional actors have been found to be key in aiding AFNs to progress (Barbera and Dagnes, 2016). Similarly, the RRCO’s can provide capacity to local communities through their flexible roles, although as actor interviewee 6 related, it can be difficult to realize positive change within the role itself. They communicated that other RRCO’s in Sado have started developing local enterprises such as eateries, which shows that the position does lead to longer-term living and work as active parts of the community. It could be that RRCO’s are encouraged to help develop markets and awareness around sustainable farming produce as well. Other countries could benefit from introducing similar RRCO roles, with the flexibility to learn about a range of issues within a rural community and therefore create future rural work possibilities.

Food processor and retailer interviewees commented that support from Sado city council subsidies had been vital in helping set up their businesses, therefore this will be an important aspect to retain to encourage more new entrants into the food system.

It was evident that food processors and eateries made space for community, both in their restaurants and cafes, and as employers. They place the wellbeing and needs of their employees first, choosing to be actively inclusive to those who need more flexibility and sensitivity, for example. Choosing local produce also helps strengthen local community.

From personal immersion over the course of a year, it is evident that the traditional culture that remains in Sado has a relatively lively population of people committed to retaining it. This culture (in the form of various ceremonial dances and live music) is often paired with local food stalls at events, and as a key part of community cohesion offers a strong appeal for migrants. Such cultural traditions also have strong ties to the surrounding natural environment and shrines where the year’s harvest is prayed for. Both the I and U-turner interviewees expressed that community culture events were a reason that they wanted to relocate to Sado. In other areas of Japan, modern international arts festivals have gained recognition as revitalizing rural areas and bringing in migrants from urban areas (Klien, 2010; Qu and Cheer, 2020). However, effects on local residents are not always positive, and locally produced art within and for the community often has a deeper and greater positive impact (Leung and Thorsen, 2022; Qu and Zollet, 2023). Sado’s home-grown food and culture festivals are a good example of this. Evident from both interviews and lived experience, new food businesses and farming produce actively input to cultural festivals, building the food, community, and cultural capital in Sado.

Farmer interviewee 15 spoke of their passion to create capacity and resources for the upkeep and renovation of local cultural assets, such as the many underfunded shrines in Sado island. The hometown tax initiative “furusato nōzei” (ふるさと納税) is one channel to gaining funding for realizing such projects, and while donations are purportedly gaining popularity (Hashimoto and Suzuki, 2016), it remains to be seen whether projects can gain sufficient funding.

Indeed, ensuring that existing events are well resourced, and that new cultural projects such as protecting links between people and nature, such as shrines, is likely to be important for the sustainability of rural communities. Strengthening human connection to nature/other living beings is known to be key for wellbeing while also creating empathy for nature (Faith et al., 2010; Díaz et al., 2015; Riechers et al., 2019). Culture and art are well recognized as a bridge for connecting people to nature (Muhr and García-Llorente, 2020; Black et al., 2023).