- 1Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

- 2Montpellier Business School 2300 Av. des Moulins, Montpellier, France

The last two decades have witnessed a growing academic debate on labour exploitation, caporalato, organised crime, and migration issues in agriculture, which, as wicked problems, are deeply interconnected and resist generalisable solutions. To contribute to this thriving debate from a social innovation lens, we investigate the organising practices meant to disrupt the organised status-quo of exploitation. Drawing upon a case study from Foggia in Puglia (southern Italy), we investigate how an Italian non-profit organisation developed and implemented a multi-stakeholder pilot project of economic integration in rural areas to confront the phenomenon of labour exploitation in agriculture. Through collaboration among authorities, civil societies, and private sectors, this pilot project managed to unlock underused resources to meet the needs of the most vulnerable individuals embedded in the local ecosystem. By developing a grounded theory on practices of disembedding and embedding, this study contributes to theories on social innovation as political actions and interactions that purposely trigger disruption in established systems of labour exploitation, organised crime, and migration.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, the presence of migrants in rural areas has increased, stimulated by a growing demand for low-cost agricultural labour (Nori and Farinella, 2020). In a country like Italy, the erosion of farmers’ bargaining power often translates into an increasing dependency on cheap labour mostly provided by seasonal migrant workers (Oxfam, 2018). While particularly strong and evident in Southern Italy, these dynamics are also widespread in the rest of the Italian peninsula, Spain, Greece, and several other European countries (Terra!Onlus, 2021). Although the agricultural sector is the most affected, similar dynamics characterise other economic sectors too, such as the construction, logistics, and transport industries (OECDiLibrary, 2019).

In Italy, irregular work and labour exploitation are not unique to foreigners and migrants; Italian citizens are affected too, although to a lesser extent (Corrado, 2018a). In Italy, roughly 430 thousand agricultural workers are exposed to the risk of irregular employment, 80% of whom are foreigners (Osservatorio Placido Rizzotto, 2018). Approximately 132,000 of these labourers work and live in extremely vulnerable conditions, at further risk when illegally employed by criminal organisations, mostly from Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, and—increasing in recent years—Africa. Their average wage usually varies between 20 and 30 euros per day, mostly paid on a piecework basis. The salary is often 50% lower than the one outlined by national contracts in the farming sector, and women receive even a 20% lower salary than men. Sexual harassment often endorses labour exploitation of female farm workers. Many workers report between 8 and 14 working hours per day, even 7 days a week, often paid less than their actual work time. It is estimated that approximately 30 thousand firms currently rely on the illicit intermediation of farm workers.

In addition to resulting in social and economic vulnerability, this dramatic phenomenon is the reason for undeclared work and unregistered business, often in the hands of organised crime, moving an underground economy of about 5 billion euros, with an overall tax evasion equal to 1.8 billion euros, just in Italy (ibidem).

Given the magnitude and complexity of this problem, it is perhaps not surprising that the last two decades have witnessed growing academic research on the debate around irregular work, labour exploitation, caporalato1, organised crime, and migration (Crane, 2013; Caruana et al., 2020; Van Buren et al., 2021), also in the agri-food value chains (Fanizza, 2020; Perone, 2020). As a wicked problem (Dentoni et al., 2012, 2018), these multiple linkages among labour exploitation, caporalato, organised crime, and migration issues resist any generalisable solution. The literature agrees that this problem needs to be addressed through institutional and market changes across multiple economic sectors and collaborative processes to engage diverse stakeholders with heterogeneous values and perspectives (Haubold, 2012; Defries and Harini, 2017; Omizzolo, 2020). Yet, in practice, emergency humanitarian organisations have been the first, and often the only ones, to take on the responsibility for alleviating the problem symptoms in terms of marginalisation, exploitation, slavery, poverty, and injustice. This emergency approach does not offer long-term solutions but mainly represents an effort to reduce the suffering of the most vulnerable, at least in the short term.

To address this wicked problem, we argue the need for an agenda drawing on what Polanyi calls “the societal approach,” conceiving economic life as a totality of relations and institutions that goes beyond transactions of goods and services (Machado, 2010). Polanyi critically reproaches capitalist development and its illusion of “liberal creed” of the self-regulating capacity of free markets, as a market fully unfettered by social control creates instability, insecurity, and rebellion and destroys the social and environmental relations, which are at the basis of a responsible use of human and natural resources (Polanyi, 1944). In this regard, approaches such as ‘one price law’ (Prado et al., 2021) cannot consider the complexity of current labour markets facing migration. Albeit recognising the great strides reached so far, experts and scholars call for a change of direction genuinely inspired by a human rights agenda, which stops looking at the exploitation of workers as normal and that entails interventions and innovation for the social inclusion of workers (Giarè et al., 2020; Omizzolo, 2020; Scaturro, 2021).

Drawing on a case study from Cerignola, in the rural area surrounding Foggia in Puglia (southern Italy), this research investigates the phenomenon of labour exploitation in agriculture and offers insights into adopting innovative processes in rural contexts. This case study investigates the practices undertaken in a pilot project,2 aiming at boosting social inclusion and fighting against the phenomenon of illegal work. The project had the vision to go beyond socio-welfarist approaches that often risk dealing with only emergency aspects of migration issues instead of structural underpinnings. This initiative simultaneously sought to disrupt and add value to the overall system. First, it collaboratively fought the ghettoisation of migrants, thus disembedding them from the existing and already organised—yet illegal—system they were part of. Second, while supporting migrants for their inclusion within the licit economic system, the initiative matches the socio-economic re-embedding process undertaken by local farms, thus embedding them in an alternative, legal yet still emergent, and therefore fragile system.

With the support of this pilot local project, by cooperating and networking, some local farmers and institutions tried to partly reverse their stagnant environment, offering a legal alternative to the traditional modus operandi and contributing to decent economic growth locally. The strategy used locally is creating a short food supply chain involving all the actors, from producers to retailers. By producing organic and high-quality products, processing on-site, and selling directly at fair prices, they aimed to counteract the phenomenon of caporalato and illegal local practices, proving how labour exploitation in agriculture can be fought with agriculture itself. The main idea of a short food supply chain (SFSC) is not just about the number of intermediaries in between but to reach the final consumer embedded with information and connections with the place and the agents of production.

Generalising from the practices investigated in this case study, we reflect on how structural processes of embedding and disembedding contribute to advance a new perspective of social innovation to address wicked problems of migration, labour exploitation, and organised crime.

2 Theoretical underpinnings

Our study seeks to contribute to the debate on how social innovation can disrupt exploitative practices through structural interventions, such as fostering awareness among actors and mutually integrating stakeholders towards fair and just sustainability transitions. By social innovation, we mean the process of following and addressing the complexity of wicked problems (Westley et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2018). Why and to what extent innovation, including social innovation, can be new and different is not easy to determine (Edwards-Schachter and Wallace, 2017). Mostly associated with technological innovation in the design and development of new goods and services, recently increasing attention is being given to its social dimension, gaining new ground in research and policy (Chiffoleau and Loconto, 2018; Carl, 2020).

Richez-Battesti et al. (2012) propose classifying the dimensions of social innovation into three groups. In the first group, they bring together the various approaches that consider social innovation as a tool for modernising public policies; the second group includes an entrepreneurial dimension, then highlights the social innovation produced by social enterprises or social entrepreneurs, actors of change; in the third group, they report about approaches supported by many researchers or actors of the social economy, who consider that social innovation centred on the active participation of multiple stakeholders and democracy in the territories involved.

With regard to wicked problems, it is recognised that creating a widespread and participatory network can be a strategic action to face wicked problems and complex dynamics. This is also expected to be the significance of social innovation as a collective process and a community engagement, rather than the achievement of a single organisation, thus positive distributed outcomes rather than individual gain (Ferraro et al., 2015).

We believe that wherever peasants struggle for autonomy, practices of embedding and disembedding contribute to fostering farmers’ empowerment, bargaining power, autonomy, and local identity. It is fundamental to look at embeddedness as a practice, thus as a verb. Acting embeddedness means local actors are committed to the socio-economic environment within which they live and work; hence, they make daily efforts to keep embedding (Smith, 2011; Wigren-Kristoferson et al., 2022).

Looking at practices and processes instead of agents allows for a neutral vision of society as a system. When we say “neutral,” we want to stress the idea of practice as a tradition reproduced over time through active engagement and participation sustained by a specific community. This means that new practices can always be introduced, although these are initially considered new and counter-current. As an example, before becoming and establishing itself as a regime, even a regime itself has been practiced by a community within a system, and maybe this has been practiced by a small number of members, and it progressively involved a growing group.

Social innovations stimulate change by bringing marginal practices or concerns to the centre of people’s attention and then by reconfiguring the practice of concern; this is essentially about the embeddedness of creative processes, according to which change only becomes possible if the person is familiar with the space they want to alter (Steyaert, 2007). As such, social innovations are seen as risk-taker actors embedded within the system in which they work and move to enhance or create values by enacting local resources (Kahan, 2012). Their practices of embedding and disembedding require and entail profound local engagement within a system (Pato and Texeira, 2016).

3 Empirical background and data collection

We developed a case study in the area of Cerignola, located 40 km southeast of Foggia (Puglia), the third largest municipality in Italy. Similar to a significant portion of southern Italy, the area is affected by caporalato—the illegal hiring of rural labourers.3 In this area operates Terra! Onlus, an environmentalist association of Rome, whose promoters launched a campaign called FilieraSporca (‘dirty food supply chain,’ in English). The campaign advocates for legal initiatives that guarantee fair and transparent labels in the rural area and informal settlement of Cerignola (ghetto4 in Italian) by involving farmers, migrants, and local institutions. The seasonal concentration of immigrant workers who come to Italy to pick vegetables, especially in summer, generates informal agglomerations in which thousands of people live. Since 2015, within Filiera Sporca, Terra! has been conducting analysis and advocacy activities on the functioning of agri-food chains, identifying the critical points of important production systems and their impact on agricultural workers in terms of labour exploitation and illegal hiring. Hence, the campaign Filiera Sporca helps contextualise the pilot project carried out in Cerignola as a commitment to provide a constructive, well-informed, and proactive response to the phenomenon of irregular employment (Table 1).

A food system perspective was used to analyse the local food system as a whole and to take into account all its elements, relationships, and related effects. The rationale of the food system approach applied in Cerignola is based on the conceptualisation provided by Ericksen (2008), whose model offers a comprehensive and systemic analysis of how food systems work and impact the wider socio-material context. It demonstrates, besides the linkages between the food system and food and nutrition security, the embeddedness and feedback loops between the food system and the social and environmental resources, including ecosystem services and disservices. This overall comprehension requires broadening the concept of the food system and linking it to the wider concept of social and ecological systems (Berkes et al., 2003). Specifically, in Cerignola, a systemic view is necessary to understand the socio-economic dimensions and controversies characterising its food system. It was fundamental to analyse and understand the existing relationships among the different parts involved, actors, and any potential feedback loops and trade-offs.

To analyse the local food system, first, an in-depth analysis of the existing literature, which relies on different graphics, statistics, policies, and official documents, was finalised. Second, exploratory interviews have been conducted with local key informants (social cooperatives, agronomists, and local institutions engaged with migration) and non-local key informants, such as Terra!’s members and journalists with expertise on caporalato and migration issues. Desk-based analysis and exploratory interviews did not follow chronological order; they were carried out iteratively to inform each other as a form of triangulation. This exploratory phase lasted 1 year. Afterwards, a field survey was carried out in November 2018 and lasted 2 weeks, coinciding with the final realisation of Terra!’s project in Cerignola. This allowed us to benefit from the direct support of Terra!’s experts, logistics, and networks. During the field visits, semi-structured interviews were carried out to gather information and perceptions from local farmers and foreign labourers directly involved as beneficiaries and targets of the project, as well as other relevant local and non-local stakeholders. During the fieldwork in Foggia, we got in touch with a variety of actors and visited different locations, developing field notes and observations5.

For the semi-structured interviews with farmers and migrants, two different questionnaire guides were developed. Farmers’ interviews were conducted individually. We instead opted for a group interview with the foreign workers, as we found that the team setting eased their participation and made participants feel more confident and backed up while sharing their personal experiences and life backgrounds. Semi-structured interviews encouraged effective conversational, two-way communication to ensure confidentiality and pursue new topics as needed, in accordance with farmers’ willingness. Face-to-face interviews provided information about their motivation and expectations for the project. The questionnaire for farmers was designed to gather information about (1) aspects related to their farm and farming activities (description and management of the farm; background of the owner; labour, on-farm, and off-farm activities; and household structure and dynamics); (2) their links with the food system (market relations; processing) and with the surrounding environment (governance and institutions); and (3) perceptions and perspectives (perceptions of risks and vulnerabilities and future objectives). As for this last point, it was of the utmost importance to understand farmers’ perceptions and feelings about the phenomenon of organised crime, caporalato, irregularities, and distortions in their local food chains.

Finally, after the fieldwork, we kept following remotely the final stages of the project, liaising with local relevant actors and Terra!’s members. We monitored the continuation of project activities and the sustenance of project outcomes after the funded implementation expired until the closing phase of the assistance intervention to facilitate a sustainable, smooth handover.

Of course, engaging with and interviewing stakeholders in such a sensitive context brings about some methodological limitations. Given its limited resources, the project engaged only a few firms and migrants, which cannot be considered representative of the whole stakeholder group vis-à-vis the complexity of the problem of labour exploitation in Cerignola. For this reason, the project designers from Terra! acted carefully in engaging deeply with a restricted number of farmers and migrants in very specific activities. The COVID-19 pandemic also has prevented the possibility of replicating the project for the following 2 years. Hence, our understanding of the risks and impacts of the project, together with what the implications could be, are limited in terms of scale.

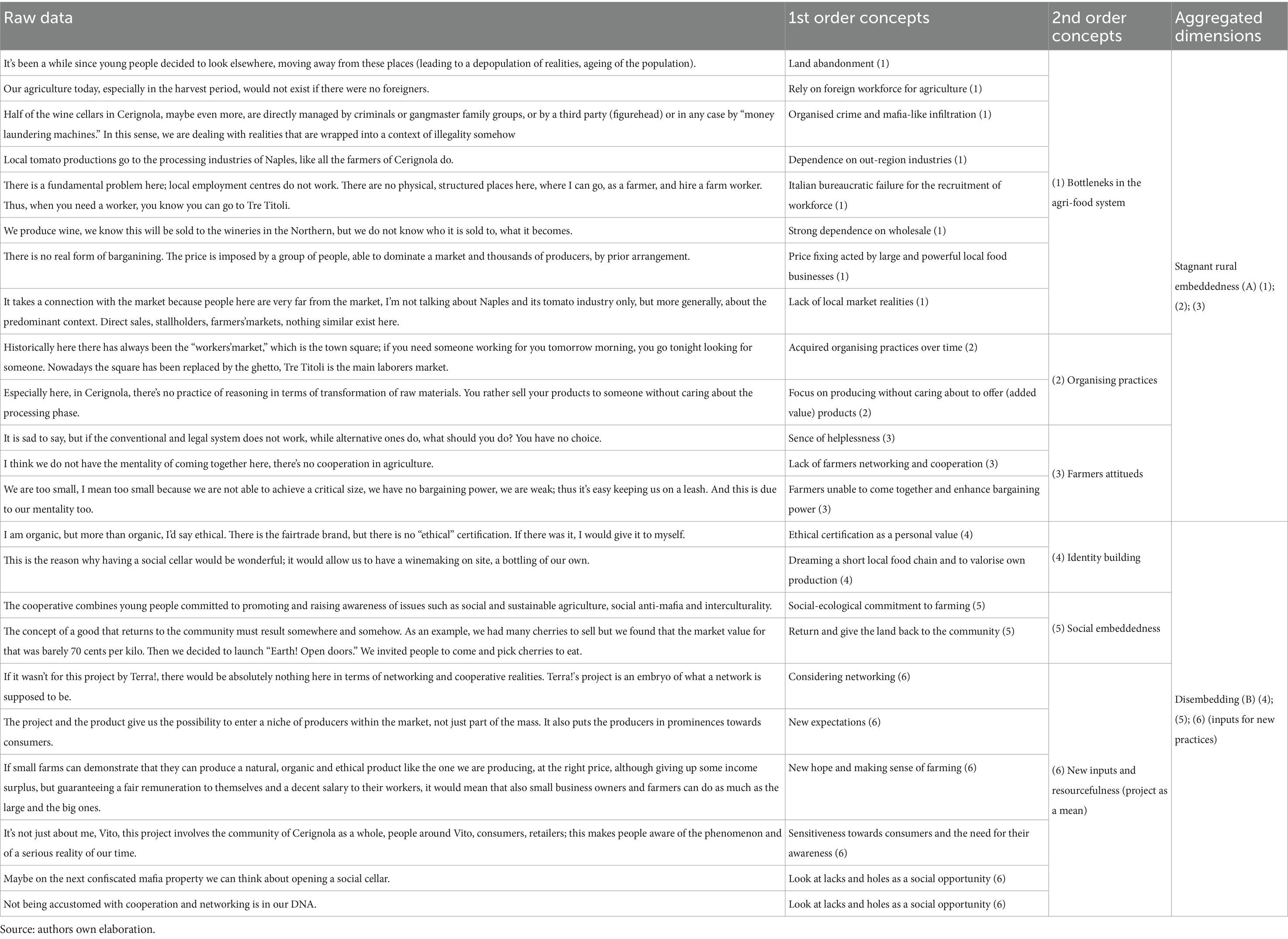

Moving from data to grounded concepts, we first used systematic manual coding to structure and analyse qualitative data by producing an Excel worksheet of interview data. Our coding intended to find emerging concepts and relationships among them, driving us towards a deeper and more theoretical understanding while remaining carefully connected to empirical evidence.

We hereby illustrate our inductive reasoning (from raw data to emerging themes and conceptual categories) based on the practice illustrated by Gioia et al. (2013). Emerging themes allowed the identification of the key dimensions around which the analysis was developed, that is, stagnant rural embeddedness and disembedding.6 These categories were then contextualised and further explored within the food system and its overall surrounding environment.

4 A socio-economic description of the food system of Cerignola

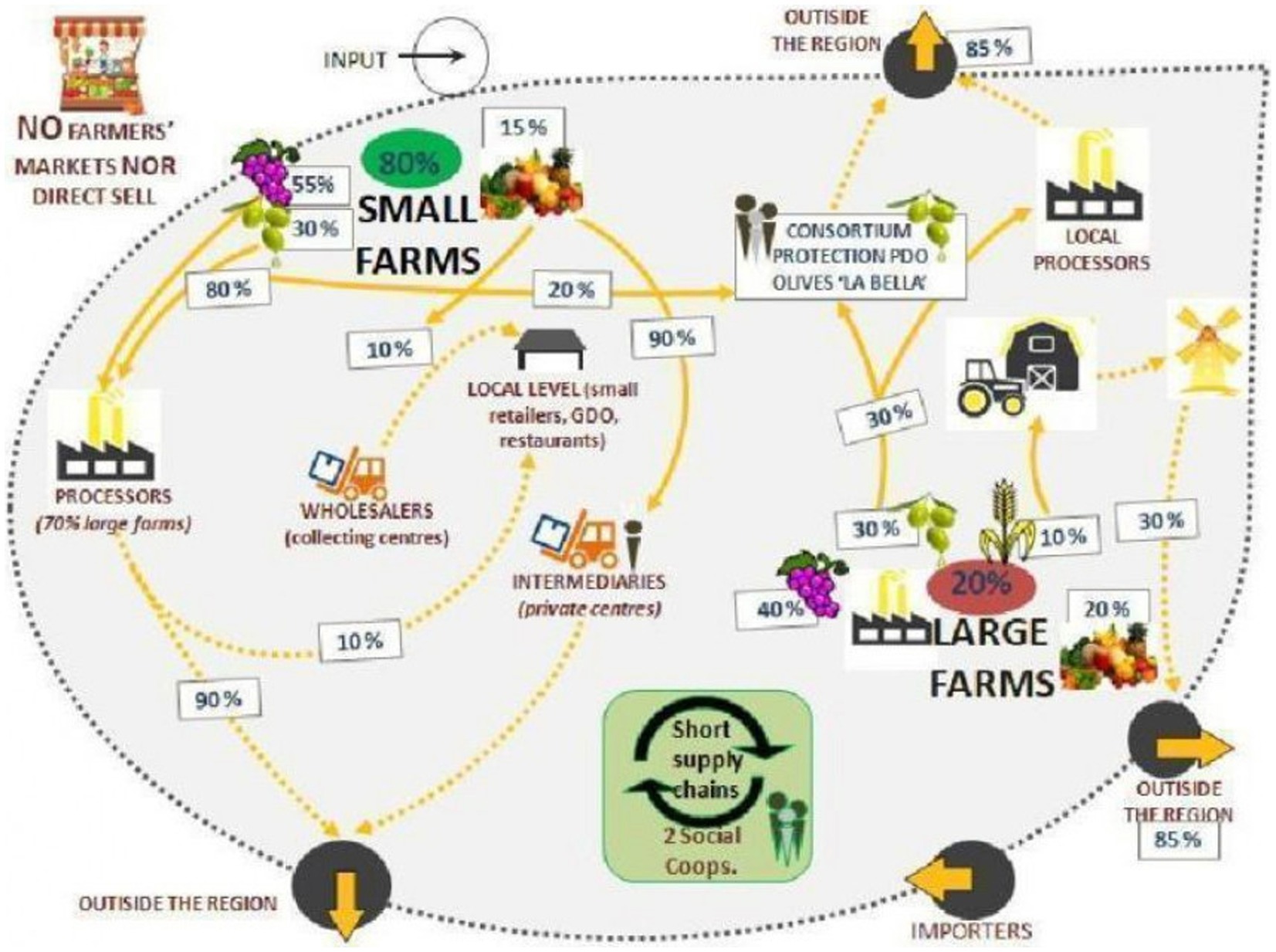

Farm production in Cerignola strongly depends on outside-region processing industries (mainly tomato chain and wine chain) and intermediaries, making the supply chains longer and more fragmented, squeezing farmers, and threatening food prices (Figure 1).

The food system of Cerignola is mostly characterised by the presence of small farms, corresponding to 80%, with an average of 5/6 ha, and a few large farms, ranging from 30 to 100 ha, for the remaining 20%. Compared to the surrounding context, even those farms reaching 10 ha shall be considered small-medium farms. The processing industries are mostly of medium size, the majority of which are for wine and olive oil production; there are approximately 30 large wineries and a huge number of oil mills.

Farmers and experts (agronomists and cooperatives) informed us about tacit marketing mechanisms and practices used by both oil mills’ and wine cellars’ owners. Right before the harvesting phase, wineries and oil mills reunite to fix the price. There is no free competition or rivalry in Cerignola in this sense. Oil mills and wine cellars are mostly managed by or belong to criminal families. Admittedly, in such a context, where irregularity is found in a variety of domains, it may be difficult to work within the boundaries of regularity. «We have an urban legend here; it’s about the ‘notorious breakfast’ among all the owners of local wine cellars, who together decide upon a price to be set locally. Local farmers actually cannot refer to a market price, or better to say, you have a market price, but it is a private one; it is not a price set by a hypothetical stock exchange. It is the price that local wineries of Cerignola make» (local key informant).

There are no social wine cellars or social mills in Cerignola, nor farmers markets. This non-practice of direct sales, which would allow farmers to get closer to consumers, is locally perceived as something that could not even be thought of differently. «Direct sales, Coldiretti’s initiatives, farmers markets … There’s nothing similar here. It would be nice for local consumers to know that every Saturday morning they can go and purchase local and fresh products. It would be nice to arrange something similar. I’ve never heard of it, I do not know how it works» (Farmer).

As our key informants told us, the absence of farmers cooperatives and farmers markets, on one side, is due to a passive local mentality and not being accustomed to networking and aggregation, and on the other, to a lack of adequate measures able to bureaucratically support grassroots initiatives and safeguard non-mainstream realities (partly not compatible with the prevailing practices) while providing them with proper facilities, funds, and bureaucratic helpers. As another farmer acknowledges: «The problem, however, is that although there was an interest in creating local cooperatives focused on producing, processing and enhancing local farmers’ wine productions, I’m afraid they would not last long because of their poor, for profit and private interests management».

The stagnant environment of Cerignola is particularly suffered by its farmers. A farmer growing organic wine and table grapes, peaches, nectarines, apricots, and olives on his 14-hectare farm has the ambition of engaging in direct sales without going through any wholesalers, particularly for wine. However, « you are not allowed, at least not now, not yet, because of the local wine cellars that overrule any sort of competition», he laments. Another farmer sells his tomato production to the industries of Naples, «likewise 99% of producers here do». Roberto would like to produce wine and olives of his own. «But processing is expensive. To process, I would need something that here, in Cerignola at least, does not exist, that is cooperation among farmers; a cooperative or a consortium, so that farmers can use that social mill together». His workforce is mostly familiar with the support, when necessary, of qualified personnel regularly hired.

Given this context, one of the farmers also explains how the practice of caporalato comes from a farmers’ perspective: «Suppose you have 65 ha of tomatoes, you are in pre-harvesting, and a stinging rain comes abruptly. You have to harvest fast enough, and you have to do it by hand as the field is wet and you cannot access it with your engines. Then you need to find 40 workers in two days. How do you deal with that? The employment centre is unfit to find the number, or it would take 2 weeks in the best of cases. You go to Tre Titoli, and talk to Mr. X. You ask him for 50 people, and he brings 50 workers the following day. It works, illegally, but it works».

Located on the outskirts of Cerignola, there is Ghetto Tre Titoli, an informal settlement also known as Ghana House, since it is mainly inhabited by Ghanaians. A ghetto is the result of social, legal, and economic pressure. In Italy, in particular, the natural consequence of the mismanagement of migration flows and the marginalisation process can affect migrants as vulnerable people (Palmisano and Sagnet, 2015). In this ghetto, migrants over time have developed different communities among their countrymen. Tre Titoli was developed right in the middle of agricultural fields where broccolis, wheat, asparagus, olives, and grapes are cultivated. The settlement is composed of scattered, abandoned brick houses with no electricity, running water, or fire. In addition, the dwellings are overcrowded, and the number of people living in each house can get bigger during the summer. Tre Titoli is one of the eight settlements in Puglia alone (D’Agostino, 2020, Sep 8).

In Cerignola, there is a severe lack of functional employment centres. It must be said that this is not a concern of this territory only, noting that the consolidation and reinforcement of the employment services able to broker labour demand and supply is a necessity throughout the territory. The failing capacity to promptly meet the request of farmers to recruit workers results in a mismatching between supply and demand for labour. As a local key informant reported, its inhabitants were able to compensate for this failure by resorting to alternative means, that is, “the market of workers.” «There’s no physical, structured place where I can go to regularly find, select, and recruit labourers. Historically here, there has always been the ‘workers’ market’, which is the town square: if you need someone working for you tomorrow morning, you go tonight looking for someone. And nowadays the square has been replaced by the ghetto, Tre Titoli is the main square» (local key informant).

As one of the farmers stated, «There is a fundamental problem, local employment centres do not work here. Thus, when you need a worker, you know you can go to Tre Titoli. It is sad to say, but if the conventional and legal system does not work, while alternative ones do, what should you do? You have no choice». Tre Titoli replaced the missing employment office in Cerignola: labour demand and supply can match here. Illegal recruitment of migrants living in the ghetto has become a local, yet illegal, practice over time.

However, within this food system, it is important to note the role of the two local social-agricultural cooperatives working for the integration of unemployed people through agriculture: Pietra di Scarto and Altereco. Their land was confiscated properties from local organised crime families.7 They have three aims: the conversion of the land from conventional to organic agriculture, the integration of disadvantaged people into the workforce in collaboration with local social entities, and the realisation of activities for education to legality, called social antimafia.

Both cooperatives strive to change the local food system. «The dominant reality in Cerignola is focused on farming only as a production activity. Thus, local farmers used to produce huge amounts of tomatoes, olives, grapes, without caring about the processing phase anyway. We, as a cooperative, have decided to reason differently, in contrast to the mainstream practice. We decided to produce just enough to sell a finished product. We try to launch a message locally, to give an idea of what farming can be» (Coop. Altereco).

The cooperatives are two local realities able to discreetly enact the surrounding environment to create their own identity and make sense of their farming activity. Theirs is the kind of influence that Cerignola is unaccustomed to, the counter-trend from which the food system of Cerignola should benefit. Their social farming reality is strongly imbued with a political vision. As the members of Pietra di Scarto remarked: «from our point of view, the management of a confiscated Mafia property is a political act».

4.1 Background information: labour exploitation in Cerignola and Italy

Cerignola is, similar to its region, Puglia, seriously affected by the phenomenon of irregular work in agriculture, more broadly, by the presence of organised crime, which undermines its local development (Pinotti, 2015; Ceccato, 2016). The mafia participates in activities encompassing the production, processing, and transport of food goods as long as they can generate illicit profits or allow for money laundering. However, mafia and caporalato are not always linked to each other (United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2016).

As one of the respondent farmers stated, «We rely on the countryside gatekeepers, it is a private service. We basically pay protection money (he laughs). We pay a certain amount per hectare for the service provided by these guardians. If you do not use this service, if you do not pay for it, rest assured that something will happen, like theft, some damages at your farm. In any case, I never leave anything at the farm. Whenever I go to the farm, I bring my stuff with me, and I take them back home. Too risky otherwise».

Its socio-economic reality, like a significant portion of southern Italy, shows high levels of corruption and irregularity, a certain level of cultural justification against the informal economy and a deep mistrust, lack of confidence towards local public institutions, and where the practice of a code of silence, called omertà in Italian, contributes to keeping silence on illegalities and crimes. These characteristics, together with an acute lack of adequate public measures and unable to support potential grassroots initiatives, often hampered by organised crime-related actors, make the context particularly weak (Vincenzo, 2006). Nevertheless, it is important to stress that the phenomenon of caporalato and irregular work is not a prerogative to the south of Italy, being a reality rampant throughout the Italian territory (Corrado, 2018b; Osservatorio Placido Rizzotto, 2020).

Quoting the words of a farmer replying to our question on what the perception of the mafia was in Cerignola in their view: «Here you perceive the mafia every day. To perceive it means just entering a shoe store, being most of the shops the result of laundered money. We have plenty of mobsters. But what’s important is that you mind your own business, and it’s done».

Similar distortions also affect the local agricultural sector, whose business and dynamics are critically undermined by organised crimes and illegal practices, which come in addition to industrial and global dynamics that characterise the commercial and distribution levels of production of markets today. This implies consumers who are increasingly disconnected from the source of our food, on the one hand, and large companies, which increase their power along the price chain of agricultural products, on the other hand.

In the collective imagination, the caporale is the great culprit, the slaveholder. While it is true that the corporal is the one who has the power to exert coercion on workers, it is not always the main character nor the exploiter, often being the arm of the rural entrepreneur-master.

Much evidence reports about workers in the fruit and vegetable sectors across Italy as victims of several forms of abuse at the hands of corporals, ranging from wages far below the minimum wage prescribed by collective labour agreements to sexual abuse, physical or verbal, and violence against women (Leogrande, 2008; Chiara, 2022). Nonetheless, physical violence and enslavement are not the most employed means by corporals to organise their teams of labourers (Perrotta, 2014).

«It is also the case to dispel the myth of the caporale as a scary ogre – a local key informant we interviewed says – since the corporal is usually an immigrant himself, simply able to speak Italian, better than his colleagues and that has been living in Italy for a while, thus knows the place and many Italian bureaucratic mechanisms. For this reason, these individuals can be easily identified with a social role that is slightly different within the group, a privileged role» (local key informant).

The corporal represents the indispensable knot between the interests of the employer and the workers, acting in his exclusive interest and of the employer’s needs to the detriment of labourers. As explained by Perrotta and Sacchetto (2014), the caporale ‘acts as a social mediator’ able to connect migrants with local farmers; they find the workers needed in the plantations, they organise the workforce, they negotiate wages with landowners, and they provide transports to the workers and supervision of the work to the producers. We can hence look at corporals as higher social actors and illicit structural holes of dysfunctional local management.

Significantly, it is good not to focus on the corporal as if it were the root cause of the problem itself. In this way, the responsibilities of companies are obscured, and only comforting solutions are found. Corporals are a link in the food chain, not even the most important. Caporalato is not the problem itself, as it is part of the broader labour exploitation-related problem. Indeed, even where there is no illegal hiring (some areas in the south and north of Italy have no corporals acting), there are phenomena of extreme and extensive exploitation as well (Mangano, 2016).

Similarly, while considerable attention is given to scenarios in which organised crime networks are involved in illegal hiring and labour exploitation, the same cannot be observed for schemes that do not appear to have a nexus with organised crime but operate under comparably exploitative conditions (Osservatorio Placido Rizzotto, 2020; Scaturro, 2021).

Farmers and caporali have their share of responsibility. However, there are other more relevant factors and systemic drivers contributing to undeclared work in the agricultural sector and exploitation of foreign farm workers, such as cost pressures from food processing industries and food retailers to whom agricultural producers supply most of their output, the high concentration in agriculture’s distribution and commercialisation levels of production, economic under-developments, a lack of modernisation of governance, lower level of state intervention in the economy and lower levels of deprivation, and mistrust in public authorities (Williams and Horodnic, 2018).

More broadly, the phenomena need to be analysed through the lens of neoliberalism, globalisation, and irregularity, basically geared towards surplus accumulation, which is not unique to southern Italy only. Overall, the causes of distortions and their humanitarian and economic consequences must be sought within a supply chain dominated by intermediaries and oligopolies able to impose top-down prices. In this context, farmers are pressured to cut costs and the worker’s wage is the only aspect of the production process that can be cut\controlled by farmers (Filhol, 2013). Consequently, this directly affects downstream actors of the production chain, who are workers, and especially migrants’ working conditions, with farmers preferring to hire people with low bargaining power and ready to accept low salaries and long working hours (Corrado, 2018a).

This is even more serious for southern Italian agriculture, where the pressure by retailers adds up to the lack of investments and a strong presence of the mafia, contributing to its precarisation and directly affecting labour conditions.

The urgency of addressing this challenge has been even recently confirmed by the new CAP with its social conditionality, establishing that benefits from subsidies through eco-schemes are bound with respect to European social and labour law (ec.europa.eu, 2021).

Despite efforts on the legislative side, results remain limited, and the phenomenon appears to still be under-prosecuted (Scaturro, 2021). Overall, besides a robust legislative framework, a cultural change within the market society is necessary.

5 Empirical findings—case study

5.1 Enacting the local context and dynamics

The Terra! project aimed to reduce farmers’ dependence on buyers and corporals (caporale in Italian) by shortening the food chain by creating a network, favouring local producers’ direct sales at a fair price. It targeted six local farms to drive them out of a passive and squeezing context while at the same time offering the opportunity to legally earn a living to a few migrants. The design process within the project aimed to reduce the physical and power gap between the various actors of the food chain—small retailers, informal market channels, processors, and farmers—while farmers were guaranteed their products would be placed on the market at a fair price. The fair price was a premium for making the products identifiable with a narrative label. Hence, the project triggered a new entrepreneurial model, first by usually bringing marginal concerns (labour exploitation) to the centre of consumers’ attention and then by embedding migrant workers and farmers within a new local food chain.

At the same time, the project also worked with a small group of migrants to offer a training opportunity while providing adequate working and living conditions. Hence, importantly, the initiative ensured travel and accommodation safety as well. In fact, the figure of the caporale is no longer limited to facilitating the match between demand and supply of human resources, but it is also an accommodation manager. They provided workers with housing solutions. In this sense, the project acted as a response addressing the structural conditions that keep migrants vulnerable to exploitation: the lack of concrete alternatives to find a job and reach their workplace.

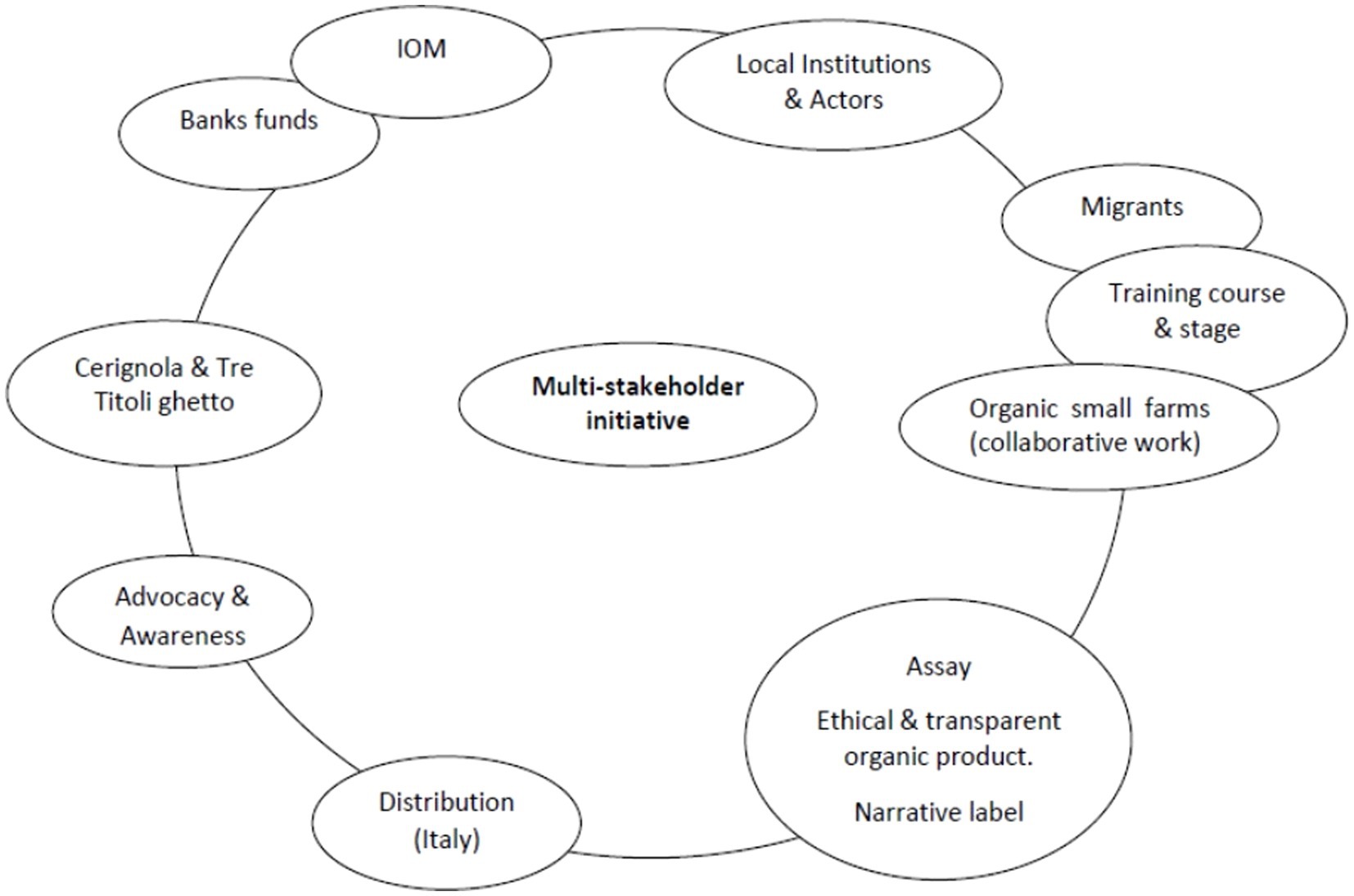

By introducing and enhancing an entrepreneurial approach among local farmers, the project supported ethical certification paths for farmers’ products (Figure 2). In the middle of Figure 2, Terra!, the association and project leader, carried on the engagement between the multiple stakeholders in Cerignola, together with its illegal housing and left-out inhabitants, as part of the project. The two local social-agricultural cooperatives, Pietra di Scarto and Altereco, are local pillars in this multi-stakeholder initiative. Over time, Terra! also engaged with national bank funds and the support of the International Organisation for Migrants to invest in a network of sustainable farming companies within the Cerignola food system.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the project carried out in Cerignola. Nodes represent actors in a simplified system; arrows represent the development and steps of the project (together with the gradual involvement of local stakeholders) of the project. Source: authors own elaboration.

After an analysis of the territory and the ghetto, the main local institutions have been involved in the project: the municipality authorities, the immigration centre, and employment centres. The project ensured paid work grants to 10 foreign workers living in the ghetto that have been detected with the legal support of the IOM. After being selected, migrants were inserted in the farms as part of a farming internship to work side by side with the respective owners. They attended 10 months-long agriculture and agro-ecology courses while supported by educators, agronomists, and farmers and their practical knowledge.

The overall outcome reached through the project was the basis for a new business culture. Overall, the project IN CAMPO!Senza caporale is the tool through which new practices have been introduced and enabled for the first time within the food system of Cerignola. As part of the effort of the project to contribute to increasing awareness and advocacy about labour rights among citizens and institutions, the project was officially launched with a public event. In the early beginning of November 2018, indeed, a concert was held in Cerignola; a band formed of professional musicians, farmers, and workers involved in the IN CAMPO! project, all drawn together by agriculture and performed by using music as a tool to speak out against labour exploitation and call to action.

The network had been designed to make farmers and migrants work together and finally produce a common finished product called Assay. Assay is a natural vegetable mix of turnip greens and broccoli. Assay is ethical throughout its chain production and organic in all its ingredients; it is a transparent product, showing a narrative label that has been distributed throughout the territory thanks to online platforms and other informal channels. Assay has been distributed in various shops, emporiums, and cafes of the national territory that deliberately decided to offer themselves as a showcase for the product. The choice to include certain actors in the network rather than others can be traced back to the virtuosity of the chosen companies within the food system. Indeed, these farming actors had already shown a certain degree. The production of Assay was confirmed and increased in 2020, involving the same actors of the previous year. The distribution and selling of this product on the national territory is an attempt at a bottom-up advocacy and awareness process, which is a new, innovative, and turning-starting point.

As an outcome, on one side, the project provided migrants with professional emancipation, specific training in agriculture, and legal support; on the other one, small farmers had the possibility to benefit from legal free labour and get a new experience. On the workers’ side, the project represents much more than a wage. One migrant involved in Terra!’s project mentioned: ««People live very badly in the ghetto. The income I draw with Terra!’s is almost the same amount as before, when I used to live and work at Ghetto Tre Titoli. But there is nothing at Tre Titoli. I have my house now, I have a roof, a bed, I can warm up when I need to. I was always cold at Tre Titoli. Tre Titoli is a living hell, there are always so many problems. Someone earns more, someone less at Tre Titoli. I can maybe earn €50, a friend of mine €100. That’s not the point. The point is that you can forget your health there. While I work legally here; my rights are respected, I am treated like a person. At Tre Titoli I can also earn € 2000/3000, but no one ensures you’ll get the amount». As another migrant reported: “befriending at Tre Titoli also means getting many problems. When I go home, here in Cerignola, I feel I can be an African, when I walk around Cerignola not that much. In any case, I prefer to walk around Cerignola rather than hanging around Tre Titoli.” And another similarly: “I’ve had so many problems at Tre Titoli. I feel much safer here.”

To foster a cooperation-minded and collaborative approach among local farmers, the project was designed to involve in-pair cultivation of broccoli and turnip greens among farmers, thus requiring farmers to agree upon the sowing and harvesting time. While mainstreaming local responses to global competition is more likely to be about competing even harder, farmers in this project were stimulated to cooperate rather than compete. «Working in-pairs has been demanding and meaningful, a new experience for which you are asked to face obstacles that I ignored before, and that I realised I had to address during the empirical stage. Roberto is a friend; in this sense our relationship has facilitated an in-pair collaboration, but we have had reasons for discussion – in terms of management, synchronicity, organisation, transport – which punctually dissolves into a mutual exchange of ideas» (Coop. Pietra di Scarto).

5.2 Reconsidering practices

The first challenge that the project undertook in the local food system dynamics of Cerignola was to reconsider and switch from “quantity before quality” practices of agricultural production and marketing. Farmers in Cerignola are almost exclusively focused on producing while they care about marketing as an afterthought. An opposite approach is hard to find locally, apart from the two aforementioned cooperatives. Because of these local food system dynamics, Cerignola’s farmers are profoundly disheartened by the production and marketing practices they are accustomed to. The interviews reveal that as-usual entrepreneurship driven by economic interests alone (a business-as-usual approach) may destroy the potential and ambitions of new networking attempts.

The creation of an ex-novo local food supply chain, as well as the establishment of a new venture, can be a hard task generally. In Cerignola, it can be even more awkward as it could be hindered by inherent and constraining social mechanisms like the ones we have mentioned (e.g., organised crime, traditional management, lack of enabling political conditions, lack of facilities, and price fixing). As one of the farmers acknowledges: «The problem, however, is that although there was an interest in creating local cooperatives focused on producing, processing and enhancing local farmers’ wine productions, I’m afraid they would not last long because of their poor, for profit and private interests management».

In this sense, according to the farmers, the birth of a new bottom-up initiative and enterprise—never experimented before in this context—contributes to making farmers more hopeful and confident towards the possibility of growing and increasing their business locally. «A wine social cellar would be amazing in Cerignola! – said another farmer – But you know about the barriers we have here. I’m trying to move along the two axes contemporarily, to maintain the Naples market channel as long as I need it, while joining virtuous initiatives like Terra!’s. I wish I could get my own high-quality and territorial based production, then short and more ethical supply chains».

Since the beginning of the project, farmers have been involved in the birth of their own new food supply chain. They followed and monitored the creation of a newborn network, from the growing phase to the processing and distribution phases. Within this network and innovative socio-economic process, farmers have been the leading actors. Farmers were pushed to struggle for their own autonomy to foster their own empowerment, bargaining power and their territorial embedding. As a cooperative member signalled: «Obviously, you cannot offer too much in three hectares only, but thanks to this project we are coming together, we are grouping. Thus, as an example, if 15 producers, although they own only two hectares each, we reach 30 hectares total. In this way you can grow and develop something for sure, you can carry out something in the long run hopefully» (Coop. Pietra Di Scarto).

By selling an ethical, organic, and transparent common product through alternative channel markets, farmers had the chance to benefit from a new marketing experience and realise how networking can effectively confer small farming a great, richer, and autonomous entrepreneurial capacity and bargaining power. As a farmer stated: «If small farms are able to demonstrate that they can produce a natural, organic and ethical product like the one we are producing, at the right price, although giving up some income surplus, but guaranteeing a fair remuneration to themselves and a decent salary to his/her workers, it would mean that also small business owners and farmers can do as much as the large and the big ones».

During the interviews, it emerged how farmers and actors (social farming cooperatives) involved in the project used to speak about themselves in relation to the overall context (including the passive attitude and mafia fabric) as an emerging collective entity, as a grassroots social movement. Switching from “I” to “We,” another cooperative member stated: «Actually, right now I am creating what I needed; we are creating what we needed» (Coop. Pietra di Scarto). Hence, the project contributed to shaping a collective action for creating something together and for the community, which both farmers and the community would benefit from. The project is the embryo of a new socio-economic network that seeks to go beyond individualism to create something as a community. By addressing the problem of individualism, they act as social innovators.

The project allowed farmers to empirically understand the benefits and rewards of producing high-quality products, although with a reduction in the quantities produced compared to the ones they are accustomed to. Like a sort of “less but better.” As an example, to explain the rationality behind it, we can mention Altereco’s owner working in social farming: «I produce tomatoes, broccoli. This is what I do, thus, what can I do to capture as much value as possible from what I effectively own and do? The answer I came to is processing. To be autonomous in this stagnant environment and to reduce dependence on the production of primary subsidised agricultural commodities, means organising the farm in a way that ensures that the strategy can be effectively implemented».

In this case, tomatoes are the basic product that could produce something with an added value. It could be sold as a fresh vegetable or value-added product (dried tomato and tomato sauce ‘passata’). Tomatoes sold as fresh products usually obtain a lower price than a value-added product, and, in this case, they were sold at a very low price to the industry of Naples and Salerno. Obviously, production costs of processed and value-added products are higher than products sold as raw materials; the key point in deciding to add value to a product is whether the added cost of production is matched by at least the same value in added income. Another farmer mentioned: «The project and the product confer us the possibility to enter a niche of producers within the market, not just part of the mass. It also puts the producer in prominence towards consumers».

Of course, navigating the project challenges between their social mission (ending labour exploitation) and commercial mission (selling an identifiable product at competitive prices) required skillful attention. As our key informant and agronomist involved in the project explained, Assay is an ethical and still a niche product; its price is the result of a series of good practices and fair remuneration; therefore, it is a high-end product, being part of an Italian economy that cannibalises its agriculture.

Obviously, it is also a matter of slowly increasing consumers’ awareness that can be read as sympathy for the project. «This jam jar is € 3.50, and I admit I felt embarrassed, awkward, initially, for this price. But over time I realised that this is not my fault. I mean, jams are usually at € 1.50 maybe at the supermarkets, but they are not my products too expensive, rather the others cost too little. Thus now I just say: if you want it, if you want something really good, healthy in all its ingredients, made ethically, take it, otherwise not» (Coop. Altereco).

Eating can be interpreted as a culture-wealth differentiating factor among consumers. «If we sell more, we’ll be able to lower the price and increase the number of our promotions. And if we sell more, it means more people stop and mind the narrative label. And if they do it, it means we reach the consumer out. I’m conscious not everybody can afford to buy certain high-end products, but I also know that as consumers, we can choose, balance, and make a deal» (Coop. Altereco).

Along with reconsidering the agricultural business practices, the project had the challenge of promulgating social farming for restorative justice. Confiscated properties from the mafia are turned to the community: whoever obtains the management of confiscated property becomes its manager, not its owner. Italian law acknowledges that the state remains the unique legitimate owner of that property expected to be used for a collective social purpose. «In my view, the concept of a good that returns to the community must result somewhere and somehow. This occurs anytime I decide to open my farm and give the community the opportunity to benefit from this place while picking fruit for free as an example» (Coop. Altereco).

It is not about looking at the mafia as a bad thing that can also have some advantages after all; it is rather about attempting to turn a lack into an opportunity. In this case, some individuals and farmers have tried to act as social entrepreneurs who look at lacks and objective structural difficulties as resources. Altereco and Pietra di Scarto can be recognised as a form of peaceful and legal disobedience, a social effort of meddling in action with the local mafia fabric. A farmer confessed: «I unfortunately think that half of the wine cellars in Cerignola, maybe even more, are directly managed by criminals or gangster family groups, or by a third party (figurehead) or in any case by “money laundering machines.” In this sense, we are dealing with realities that are wrapped into a context of illegality somehow».

In the light of this context, IN CAMPO!Senza Caporale succeeded in putting social justice and farming together. The involvement and engagement of farmers and exploited workers to realise a new food chain and a final product is the outcome and the synthesis of a social-ecological embedding and entrepreneurial synchronicity practice that should characterise farming.

If Cerignola is a system where stagnant agriculture, caporalato, labour exploitation, mafia, and omerta meet and overlap, the finished product of broccoli and turnip greens pâté represented—symbolically and ideally—the effort of a new practice where farming, social-ecological embedding, fight against caporalato, exploitation, and disobedience successfully meet and overlap as well. «The mafia fabric has become a cultural aspect. The mafia is a subculture. And if we figure out the mafia as a mountain of excrement, we can choose between two approaches; get used to it, thus by embellishing excrement with flowers as far as you can; otherwise, you can opt for shovelling that mountain of excrement. It is a matter of vision and determination. Unfortunately, we do not have the mentality of coming together to shovel those excrements» (Coop. Pietra di Scarto).

The narrative label is a carrier of a social justice message. The final product has a story to tell, and it can reach the market where a possibility is given. «I think by this project it’s easier to place such a product on the market; I mean a product drenched in justice, social inclusion, emancipation, and empowerment. I think it’s easier since there is a lot to tell about, behind the product; this product tells about social justice» (farmer). Through their involvement in the project, farmers started thinking wider in terms of beneficiaries and actors of the food system, as well as about the great impact that the project could achieve at the community level. To a certain extent, farmers realised their roles could be socially and ecologically enacted and played as networking and social-making actors. «It’s not just about me, Vito, this project involves the community of Cerignola as a whole, people around Vito, consumers, retailers; this makes people aware of the phenomenon and of a serious reality of our time» (farmer).

The project aimed at reaching consumers locally, regionally, and nationally. The involvement in such a social justice project made farmers feel they should act as social actors, besides being producers and practitioners, potentially able to contribute to increasing consumers’ awareness. «People are more sensitive to ethical and environmental issues behind the products. There’s already a growing portion of consumers that pay attention to what the product means and what the product wants to tell about itself and its producer. If consumers want to understand, we must make them able to understand». (farmer).

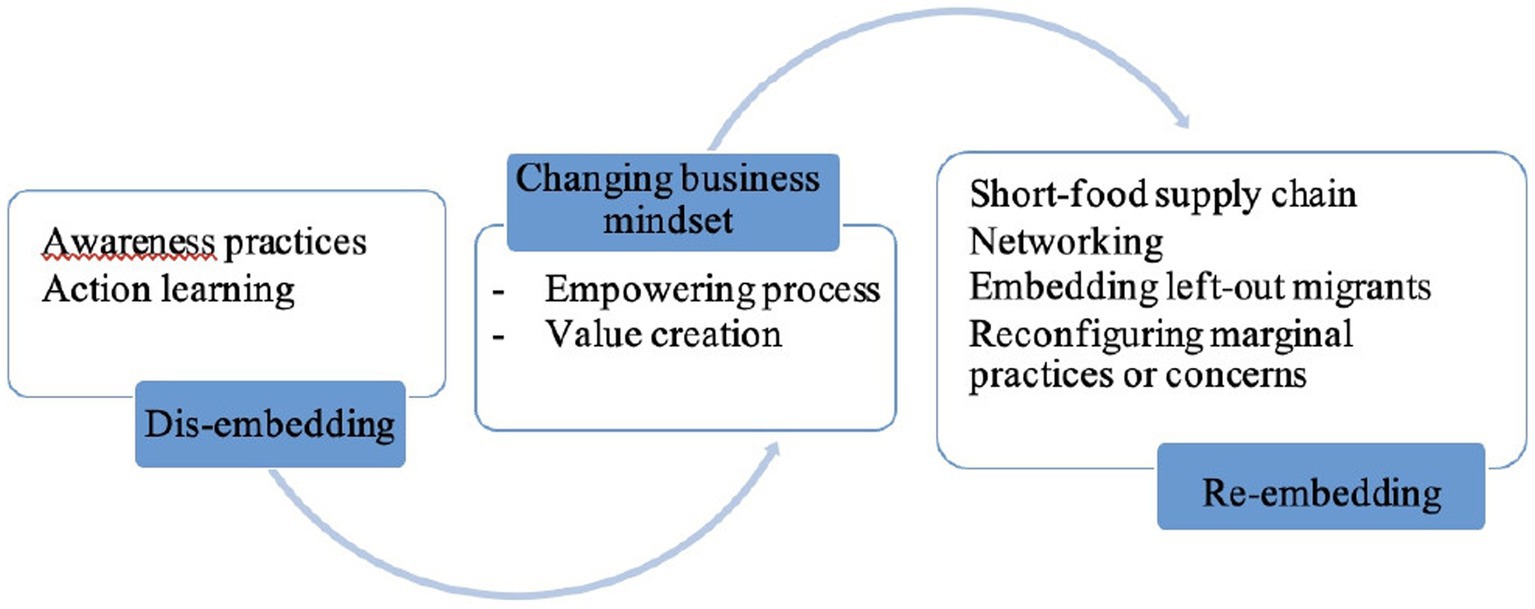

5.3 From disembedding to re-embedding farmers and migrants in local food systems

The analysis of data and interviews through Gioia methodology shows that a “stagnant rural embeddedness” and “disembedding” dynamics were two dimensions characterising the food system of Cerignola that have emerged throughout the transformation process that the project aimed to initiate8 The multi-stakeholder initiative simultaneously disrupted and added value to the overall system, triggering and enacting a re-embedding process to reverse a stagnant environment. First, the project collaboratively fought the ghettoisation of migrants, thus disembedding them from the existing and already organised—yet illegal—system they were part of. Second, while supporting migrants for their inclusion within the licit economic system, the initiative matches the social-economic re-embedding process undertaken by local farms, thus embedding them in an alternative, legal, yet still emergent system.

Whereas we had farmers and other local actors embedded in a stagnant environment, the project triggered a disembedding process. The initiative indeed aimed at raising awareness among local actors about the environment within which they are embedded while empowering and making them more participative. In this sense, farmers have been guided through a disembedding growth to the extent to which they have been dis-embedded from a high dependence on outside processing industries and intermediaries to sell their productions, as well as dis-embedded from an overall passive attitude and production-focused mentality.

The increased awareness and empowerment among the involved farmers have, in turn, somehow enabled the start of a transformative re-embedding process within the food system of Cerignola. We can interpret farmers’ desire and effort to move into a changing process as an attempt to re-embed themselves and their farming activity into something new, self-determined, and locally grounded. In these terms, we can recognise a rural and socio-economic innovation process that seeks to guide actors towards something else. In an overall stagnant environment, the project worked as a trigger for the establishment of a new local mindset and as an extension support for developing a new business culture: training and extension support, access to finance and markets, and supporting collaboration among farmers.

The key point is that disembedding and embedding practices are in tandem processes with social innovation; the more farmers get dis-embedded from the stagnant environment within which they used to act and work, the more they can progressively get confident and able to harness unexploited local resources while self-determining themselves. In this sense, they gradually become able to undertake the social innovation process in their own hands as a form of empowerment and value creation (Figure 3). Thinking together about a future small farmers’ consortium and/or a wider socio-economic network is therefore a novel practice that these local farmers have started engaging through the Terra! project, an embedding effort to make a local system more than a space but rather a place.

Figure 3. From disembedding to re-embedding: new local practices for an interplay between embedding, disembedding, and changing business mindset. Source: authors own elaboration.

Farmers in Cerignola need to get confident and empowered by practising their capacity daily to feel embedded within the community and a network, regardless of the output that may result from an enhanced embedding process. By re-embedding, farmers can build confidence over time and practice (Williams-Middleton, 2014).

It is important, at this point, to acknowledge the role that the project and the organisation (as project leader) played as a new light on local farmers. It seems like the initiative worked as a new social catalyst in the farmers’ eyes in terms of a change of virtuous local social referents (mostly nonexistent so far), thus providing new social and human capital for “nascent entrepreneurs” (Davidsson and Honig, 2003).

Farmers, in turn, started moving autonomously till reaching new ownership: an enforced belonging, empowerment, liability, participation, and involvement. The fact that some firms have succeeded in working ethically, sustainably, and uprightly within the food system of Cerignola might offer a record to its environment and actors, incentivising other firms to come out and do the same.

The project IN CAMPO! Senza caporale facilitated a learning process in the system whereby companies are motivated to comply, weaving regular working relationships. In addition, the interaction between firms and cooperatives might be advantageous for farmers: providing essential services for the benefit of members and advocating for social justice carried out by the cooperatives might be inspiring for a for-profit social approach among farmers. Farms, basically business organisations aimed at earning a profit, could learn from the activism of the two cooperatives, the social use of confiscated mafia properties that they run, and their services and initiatives, such as education to legality. Furthermore, local farmers could benefit from cooperative networks, for instance, by more easily joining one of the chains they are part of, such as fair-trade supply chains.

One of the farmers involved reported: «Many friends and colleagues of mine have asked me for information about how to get into the project. They would like to be involved with next initiatives. Besides collecting a new experience almost for free, they are conscious of the showcase that the project offers and of the great opportunity that producing a good that is a carrier of social justice and fight against exploitation and mafia can represent».

6 Discussion and conclusion

This study has tried to look at labour markets characterised by informality and even by criminality with a lens that helps to understand the particular type of segmentation that characterises labour markets in Southern Italy. In fact, the presence of uncertain citizenship status of workers, the weakness of farmers in a context characterised by strong imbalances of power in the supply chain, and the weakness of the governmental bodies in enforcing compliance with labour regulation concur in nurturing an informal labour market in which the role of illegal labour intermediaries is pivotal (Gordon, 1995; Leontaridi, 1998).

This case study from Cerignola illustrates the value of an embedding and disembedding approach in tackling the complexity of wicked problems and highlights the importance of understanding a local food system to understand new models of social innovation. By developing a grounded theory on practices of disembedding and embedding, this study contributes to theories on social innovation as political actions and interactions that purposely trigger systems disruption and change towards sustainable transitions. Indeed, farmers and farmworkers involved in the initiative are led to disembedding themselves from a stuck environment and re-embedding into a pro-active and informed status, which entails new local practices for a continuous and fruitful interplay between embedding, disembedding, and changing business mindset. Furthermore, this case study helps build an intellectual bridge among theories of social innovation and labour exploitation, organised crime, and migration in rural areas.

The risk of relapse for those migrants involved in the project is not out of the question, although not easy to assess. Nonetheless, what can be observed for this initiative is that all nine migrants engaged in the project are out of the ghetto, except for one whose legal status does not allow him to be regularised. Some are employed in local farms today, and others were hired as trainers in projects akin to Terra’s initiative.

Along the same line of IN CAMPO!senza caporale, new emerging projects with a social justice-farming and sustainable agriculture purpose exist. Pomovero,9 Sfrutta zero,10 and Funky tomato,11 for example, are other virtuous projects in Italy born to offer and show valuable legal alternatives to socio-economic actors. Among others, Iamme deserves a particular mention as the most recent attempt to revolutionise the entire food chain against the phenomenon of caporalato by offering a series of ethical and organic products with the involvement of a large retailer.12

The results of our qualitative analysis allow us to highlight the positive effects of a social learning process within a food system and the role that a guided network, oriented for socio-economic development and knowledge sharing, can play in providing a distinctive and innovative contribution in the field of food security as well as socio-economic growth. As previously explained, the network targeted six local farms to drive them out of a passive and squeezing context while at the same time offering the opportunity to legally earn a living to migrants. The network had been designed to make farmers and migrants work together, leading farm owners to realise how networking can confer small farming a great, richer, and autonomous entrepreneurial capacity and bargaining power. Overall, the interplay enacted by farmers practicing embedding and disembedding, thanks to the project that worked as a trigger, resulted in a virtuous circuit able to contribute to the empowerment of farmers’ autonomy and bargaining power while providing products and services to the community, with effects on the overall food system.

Putting stakeholders together, fostering engagement, ensuring a participatory architecture, and coordination among stakeholders are key features of robust action strategies; a network structure with the ability to connect tissue to adapt to changing circumstances is what gives the system flexibility and robustness, without which the system would fail whenever one of its components failed (Ferraro et al., 2015).

The creation and dissemination of knowledge of innovation phenomena and virtuous processes can represent a useful tool for the realisation of new models of conscious development, production, and consumption, which pay attention to sustainability and social dynamics. In particular, the project contributed to overturning the embedded mentality of a way of farming mainly focused on production and quantities. The idea of producing and selling a finished product, in this case a paté of broccoli and turnip greens, wants to communicate a markting shift: from a mere production to a product valorisation. What can I do to capture as much value as possible from what I effectively own and do? In other words (van der Ploeg’s words): how might farmers practice a broadening, that is, the introduction of new on-farm activities, resulting in an increase of farm income through diversification, and a deepening, that is, the transformation of agricultural activities to deliver products that have a higher added value per unit (Der Ploeg and Douwe, 2008)?

We believe this study also includes the development of a positive theory of change with new potential replicable context-adapted applications. As previously outlined, we refer to some key references on social innovation, which means innovation-seeking to follow and address the complexity of problems. More than simply focusing on quantifying innovation, our case study emphasises the relevance of a network-learning process and practice. It also emphasises the need for transformations and transformability as an important aspect of resilient development and explicitly recommends a close involvement of stakeholders throughout the process, from farmers to consumers, including institutions, experts, and practitioners.

We believe Cerignola contributes to uncovering that behind all the apparently durable features of our world, there is always the work and effort of someone, and that social structures are temporal effects that can always break down, be taken down, or collapse if and when the plug is pulled (Nicolini, 2013).

In the case of Cerignola, the clearest element of local embeddedness (cultural and institutional) is the stagnant environment given by the reality of deep-routed illegal organisations, the phenomenon of caporalato, and the passive attitude of farmers, as well as the absence of functional employment centres and the existence of an agricultural sector in a chronic state of crisis. Nonetheless, Cerignola also contributes to highlighting that the relation between practices and their material conditions—between ‘structure and process’—is conceived recursively as two-way traffic and that systems can be shaped by the actors in the system. In addition, Cerignola confirms that a guided network structure is arguably the most strategic action that should be undertaken to address local wicked problems while protecting local farming and reversing illegal and short-sighted dynamics. Specifically, in Cerignola, a process of disembedding was a prerequisite and first step towards entrepreneuring to the extent that it allows farmers to become conscious and proactive and later to run an entrepreneurial farming process as a group. In Cerignola, more than in other contexts, it is evident that the triggered emancipation of stagnant local farmers occurred throughout the socio-economic project, an emancipation that most likely would never have happened if an external actor (Terra! Onlus) had not intervened. The organisation is seen as a change in social-referent in farmers’ eyes, and this is what farmers needed to emerge and get dis-embedded from their stagnant and constraining environment.

Terra! offers the possibility to “harness the local reality” to tackle the problem of caporalato and exploitation while enabling farmers’ re-embeddedness into the food system and empowering their network. In this sense, the more farmers get dis-embedded from the stagnant environment within which they used to act and work, the more they can progressively get confident and able to harness (unexploited) local sources while self-determining themselves. In conclusion, in Cerignola, we need to deal with a “longer” process of disembedding and re-embedding farmers from something odd into something new and different from the mainstream context. As re-embedded farmers, empowered with a new network and tools, they started looking at farming with an entrepreneurial approach instead of a passive attitude.

The exploitation of the workforce, and in particular of the immigrant one, is a phenomenon that has its roots in the characteristics of the agro-food systems and the conditions of the local context—lack of ‘good’ social capital, limitation of public institutions, and presence of ‘bad’ social capital (organised crime). As we have seen, one of the consequences of the structural fragility of these contexts is weak entrepreneurship. To address the problem, it is necessary to act on its structural causes, transforming food systems according to principles of sustainability. IN CAMPO!Senza, caporale is an example of lessons learned where new entrepreneurship can work as a lever of transformation and construction of ‘good’ social capital. Public policies should focus on the ability of local actors, particularly local entrepreneurs, to build social capital through collective actions of a transformative nature.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1324465/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^“Caporalato” is a form of illegal hiring and labour exploitation through an intermediary. It could be roughly translated into English as “gangmaster system” (Poppi and Travaglino, 2018); nevertheless, this would not be a proper translation since the Italian term has no corresponding in the English language.

2. ^“IN CAMPO! Senza caporale”—Terra! Onlus. See sub-chapter 4.1 for details.

3. ^For the interested reader, we provide a detailed background on the problem of labour exploitation in Cerignola and Italy in Annex I.

4. ^A section of a city, especially a thickly populated slum area, inhabited predominantly by members of an ethnic or other minority group, often as a result of social pressures or economic hardships (Dictionary.com).

5. ^For the interested reader, a table where we better delinate the data collection is available as supplementary material

6. ^The inductive reasoning through Goia methodology is illustrated.

7. ^Confiscated properties mean that corresponding lands are state properties that can be assigned to private through municipal calls, as long as their managers will improve and take care of it. In this sense, these two realities work as providers of local products to the community while embodying the sense of social justice. Indeed, confiscation is a legal form of seizure by government or other public authority, which aims to reattribute the criminal’s ill-gotten spoils to the community.

8. ^The inductive reasoning through Goia methodology is illustrated.

9. ^https://altreconomia.it/pomovero/

10. ^http://www.fuorimercato.com/rimaflow/categorie-di-prodotti/sfruttazero.html

References

Berkes, J., Folke, C., and Colding, J. (2003). Navigating social-ecological systems building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carl, J. (2020). From technological to social innovation – the changing role of principal investigators within entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Manag. Dev. 39, 739–752. doi: 10.1108/JMD-09-2019-0406

Caruana, R., Crane, A., Gold, S., and LeBaron, G. (2020). Modern slavery in business: the sad and sorry state of a non-field. Bus. Soc. 60, 251–287. doi: 10.1177/0007650320930417

Chiara, Spagnolo (2022). laRepubblica. Available at: https://bari.repubblica.it/cronaca/2022/04/29/news/tre_braccianti_su_3_hanno_subito_abusi_sessuali-347309519/

Chiffoleau, Y., and Loconto, A. M. (2018). Social innovation in agriculture and food: old wine in new bottles? Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food. 24, 306–317. doi: 10.48416/ijsaf.v24i3.13

Corrado, A. (2018a). Is Italian Agriculture a ‘Pull Factor’ for Irregular Migration - and, If So, Why? Open Society Foundations.

Corrado, A. (2018b). Migrazioni e lavoro agricolo in Italia: Le ragioni di una relazione problematica. Open Society Foundations. Available at: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/italian-agriculture-pull-factor-irregular-migration-and-if-so-why/it

Crane, A. (2013). Modern slavery as a management practice: exploring the conditions and capabilities for human exploitation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 38, 49–69. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.0145

D’Agostino, L. (2020). Aid or autonomy? A showdown in Italy’s agriculture heartland : The New Humanitarian.

Davidsson, P., and Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 18, 301–331. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

Defries, R., and Harini, N. (2017). Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 356, 265–270. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1950

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V., and Schouten, G. (2018). Harnessing wicked problems in multi-stakeholder partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 150, 333–356. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3858-6

Dentoni, D., Hospes, O., and Brent Ross, R. (2012). Managing wicked problems in Agribusiness. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 1–149.

Der Ploeg, V., and Douwe, J. (2008). “The new peasantries: struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of empire and globalization” in The new peasantries: struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of empire and globalization. 1st Edn. Routledge. 1–364.

Edwards-Schachter, M., and Wallace, M. (2017). ‘Shaken, but not stirred’: sixty years of defining social innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 119, 64–79. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.012

Ericksen, P. (2008). Conceptualizing food systems for globalenvironmental change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 18, 234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.09.002

Fanizza, F. (2020). Grande Distribuzione Organizzata e agromafie: lo sfruttamento degli immigrati regolari e la funzione dei criminal hubs. SocietàMutamentoPolitica 11, 91–100. doi: 10.13128/smp-11946

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., and Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: robust action revisited. Organ. Stud. 36, 363–390. doi: 10.1177/0170840614563742

Filhol, R. (2013). Les travailleurs agricoles migrants en Italie du Sud. Hommes Migrations 1301, 139–147. doi: 10.4000/hommesmigrations.1932

Giarè, F., Ricciardi, G., and Borsotto, P. (2020). Migrants workers and processes of social inclusion in Italy: the possibilities offered by social farming. Sustain. For. 12:3991. doi: 10.3390/su12103991

Gioia, D., Corley, K., and Hamilton, A. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organ. Res. Methods 16, 15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

Gordon, I. (1995). “Migration in a segmented labour market” in Transactions of the institute of British 861 geographers, The Royal Geographical Society. 139–155.

Haubold, E. M. (2012). Using adaptive leadership principles in collaborative conservation with stakeholders to tackle a wicked problem: imperiled species Management in Florida. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 17, 344–356. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2012.709308