- Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF), Müncheberg, Germany

Introduction: This study sheds light on the challenges faced by women in alternative food networks (AFNs) applying organic farming in Berlin Brandenburg. They engage in AFNs as producers, consumers, and prosumers (producer-consumers). Literature indicates that individuals in farming face obstacles such as limited ownership, traditional gender roles, undervalued contributions, disparities in recognition and compensation, and barriers to leadership. The objective of this research is to understand the realities, self-perceptions, and conditions experienced by individuals in AFNs and organic farming. This study examines contextual factors, participation levels, decision-making processes, leadership dynamics, and impacts related to these participants.

Method: Using qualitative content analysis, interviews were conducted with active female respondents in three types of AFN: community-supported agriculture (CSA), food cooperatives (FCs), and self-harvest gardens (SHG).

Results: The interviewees expressed optimism about their involvement but emphasized the need for increased governmental support and community engagement. Participants in CSAs and FCs reported stronger producer-consumer connections and community building, while self-harvest gardeners sought personal growth and access to garden spaces.

Conclusion: Interview data highlighted demands for gender equality improvements and support mechanisms. Addressing these challenges and promoting equal status for them can enhance their contributions to community building and localized food production. Recognizing their efforts fosters societal inclusiveness and progress. Understanding and supporting individuals in organic farming AFNs, we can move towards a future where their contributions are properly acknowledged.

Introduction

Women are playing an increasingly important role in food production, accounting for 43% of the worldwide agricultural workforce (Alston et al., 2018). Agricultural industries in the developed world operate in a policy, media and industry environment that is predominantly masculine, and rarely acknowledges the significance of their input to successful farm production (Dahm, 2022a).

The current share of female farm managers in Germany is approximately 11%. On top of that, only one in five of the people set to inherit or otherwise take over farms are female (Davier et al., 2023). However, they face more difficult conditions than men, due to male-dominated systems of access to land, knowledge, networks, roles, recognition and market (Davier et al., 2023). Participants frequently copy male roles and do not often develop their own unique leadership. They often adopt male behaviors due to societal and systemic pressures within male-dominated agricultural environments. These pressures include the need to conform to established norms to gain acceptance and recognition. Such systemic constraints hinder them from fully developing their potential as they navigate structural barriers and gender biases. This perspective aligns with the findings of Annes et al. (2021), who discuss how French female farmers challenge hegemonic femininity in agriculture (Annes et al., 2021). Nevertheless, more than 50% of the graduates of agricultural and nutritional sciences courses have been women for more than a decade in Germany (Zoll et al., 2018). About 36% of workers in Germany’s agriculture sector are female, yet, this figure may not directly correspond to the proportion receiving financial support (Dahm, 2022b).

Our understanding of the distinction between consumption and production in recent times, and especially in alternative food networks (AFNs), has undergone an intriguing shift. What was once a clear-cut division has now become more fluid and nuanced (Stephens and Barbier, 2021). Several factors have contributed to this change, including advancements in technology, evolving roles of consumers, and the power of individual choices to influence public life and cultural values through consumption. As a result, a new term has emerged: the “prosumer,” describing those who exist in the middle ground between consumers and producers in today’s AFNs (European Union, 2018; Alberio and Moralli, 2021). This hybridization of food production and consumption is unfolding especially within the organic farming area, where growing, distributing and consuming intersect. When using the term “prosumers,” the division of responsibilities, roles and practices is not a strict one, as AFNs are cooperative networks with the participation of professional farmers/gardeners, on the one hand, and consumers, on the other, sharing (or not sharing) labor practices in the fields of cultivation, care, harvesting and distribution to varying degrees and extents.

This term, “hybridization,” describes the mixing of roles that were formerly distinguished between producers and consumers, resulting in “prosumers” who take part in both the production and consumption of food. This integration showcases the interconnectedness of production and consumption and its influence on food behaviors, access, and policy, emphasizing the importance of household-level activities and unpaid care work in food systems (Brückner and Sardadvar, 2023).

Within the food industry, new forms of collective action have emerged as a result of the rise of alternative food networks, such as short food supply chains and collaborative farmer stores (Kessari et al., 2020). As consumer behavior and corporate sustainability change, these networks become even more important for tackling sustainability concerns in the global food chain (Navrátilová et al., 2020). Though there are differences based on the kind of organization and degree of responsibility, these networks have a hierarchy of decision-making and accountability (Kessari et al., 2020)The selection of sustainability indicators is a critical factor in ensuring that decisions about production and consumption are taken into account in an integrated and global context (Rohmer et al., 2019). The roles of each participant and socioeconomic factors influence the perceptions of organizers, producers, and consumers in these networks, which also vary (Escobar-López et al., 2021).

The practices, narratives and decisions of both producers and consumers involved in food production are considered, playing a pioneering role in reshaping the entire landscape (Alberio and Moralli, 2021). Participants in AFNs exemplify this evolution as they engage as consumers, producers and processors (Nigh and González Cabañas, 2015). Conversely, urban consumers are increasingly drawn to AFNs for various reasons (Zoll et al., 2018). It is crucial to acknowledge that consumers are not passive bystanders but active contributors, who help shape the range of options available to them (Randelli and Rocchi, 2017).

Research has shed light on a range of motivations behind participants’ engagement, including the search for ecologically sustainable modes of production, certified food quality, food safety consciousness in general or food hazards, health and nutrition concerns, as well as sympathy with social and political causes (Zoll et al., 2018). Furthermore, AFNs bear the potential of gradually redirecting the food system toward a more sustainable orientation (Zoll et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, gender inequalities persist in food provisioning in AFNs, with women often bearing the primary responsibility for this role (Som Castellano, 2015), which underscores the need for further investigation and up-front dedication to redistributing gender inequities within AFNs. This research, thus, seeks to shed light on female farm managers and active participants in AFNs, focusing on the Berlin-Brandenburg region of Germany. The research was conducted with the support of a broader research team, aligning with the journal’s interdisciplinary perspective and that this is why sometimes the term ‘we’ is used.

We do not know enough currently about women producers/prosumers in AFNs working with organic farming practices in this geographical area. We address this gap in order to better understand the obstacles and opportunities that are specific to experiences in this domain. Our understanding of the roles to be played by these producers/prosumers within sustainable agriculture and alternative food systems in Berlin-Brandenburg will be beneficial to them, farmers, and the members of AFNs. Understanding the roles of female producers/prosumers in sustainable agriculture and alternative food systems in Berlin-Brandenburg will empower them to take on leadership roles, drive the adoption of sustainable practices, and strengthen community ties through initiatives like CSA and food cooperatives. A more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable food system that benefits all stakeholders can result from using this knowledge to guide supporting policies, generate employment opportunities, and prioritize health and nutrition.

Alternative food networks

The aim of AFNs is to establish connections between food producers and consumers (Barnett et al., 2016; Zoll et al., 2021). The primary objective of these alternative approaches is to promote both environmental and social sustainability. Various examples of AFNs in Germany include community-supported agriculture (Medici et al., 2023), food coops, farmers’ markets, self-harvest gardening, animal sponsorship, urban gardening, pick-your-own farms and food assemblies.1

AFNs aim to use resources sustainably. They represent a movement focused on transforming economic power structures to tackle diverse food system challenges, such as consumer health and environmental impacts (Brinkley, 2018).

Women producers/prosumers who prioritize local food systems in AFNs tend to be responsible predominantly for and spend more time in food provisioning, and engage in more food production and gardening (Meena et al., 2019).

These initiatives foster collaboration between consumers and agricultural producers allowing them to work together, form mutual agreements, and exchange knowledge (Brinkley, 2018). In Baltimore County, Maryland, such initiatives are evident where 110 farms and 224 markets participate in a closely-knit alternative food network aimed at addressing food system challenges through direct consumer engagement producers (Brinkley, 2018).

Similarly, in various regions of Germany, including urban and peri-urban areas, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), food cooperatives, and self-harvest gardens have emerged as significant models of AFNs. These initiatives create meaningful bonds between producers and consumers through a shared commitment to environmental and societal goals, facilitating direct engagement and cooperative use of resources and land (Zoll et al., 2021).

In the United States, alternative food networks create a unique bond between producers and consumers, not just through the exchange of crops but also through the sharing of information and resources. Their study focuses on the regional context of various AFNs across the US, emphasizing the importance of local engagement and mutual support (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017).

Incorporating these regional contexts, it becomes evident that the success and impact of AFNs are deeply influenced by their specific geographical and socio-economic settings, enhancing the overall understanding of how these networks function and thrive in different areas. Within European AFNs, individuals make up a large portion of producers and distributors and are thus key to the networks’ formations and transformations. Participants engage in many traditional roles, but they also undertake substantial work that is usually not counted as part of their family’s or household’s production, taking on activities that occur most often in nondomestic spaces. These activities have both challenged and reinforced gender roles within AFN spaces (Blumberg, 2022).

Participating in community-supported agriculture (CSA) allows them to shatter commonplace gender norms. Not only that, but obtaining these enfranchised roles in CSA farming seems to have a positive impact on the social, economic, and environmental conditions of the communities themselves. They are the pathfinders for community resilience and sustainability (Jarosz, 2011).

Moreover, in Germany those in rural areas are systemically important, but, at the same time, are often not very visible when it comes to finances. In 2022, 83% of the individuals in agriculture work on the family farm, while almost three-quarters are involved in strategic business decisions (Davier et al., 2023). Measures to increase access to assets and services for them and empowerment of female farm successors by education and extension providers, as well as mentoring programs to pave the way for more to become farm managers and decision-makers are urgently necessary (Davier et al., 2023).

Gender relationships are fundamental worldwide to the way in which farm work is organized, assets, such as land, labor, seeds and machinery, are managed, and farm decisions are made.

In order to offer a new perspective, we apply a social analytical framework to examine the involvement of participants as producers and/or prosumers in AFNs applying organic farming. Our research seeks to specifically address the following inquiries:

• What factors influence women to be producers and/or prosumers in AFNs?

• To what extent and in what ways are participants involved in decision-making and leadership in AFNs?

• What is the impact of their participation in AFNs?

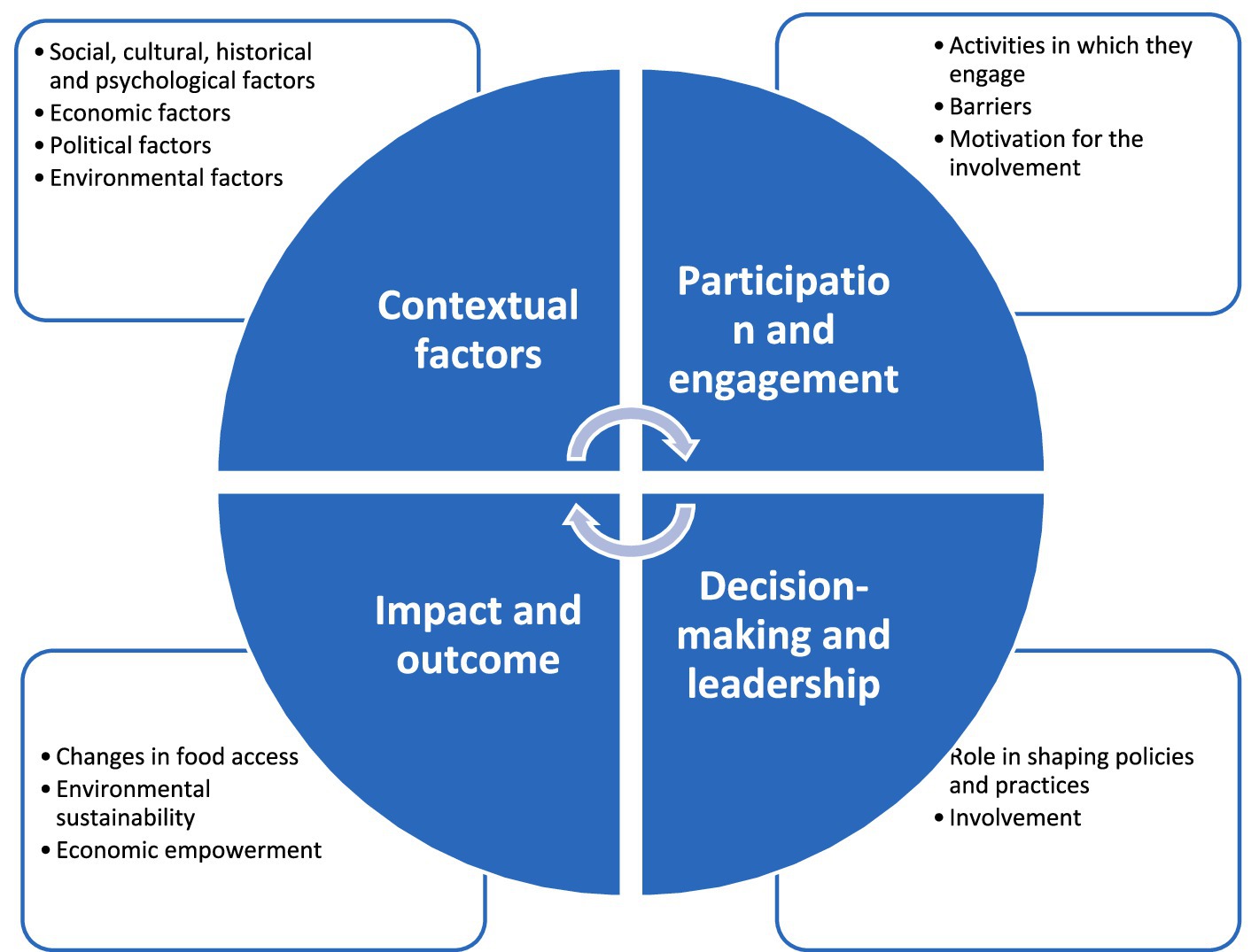

We created an analytical framework to examine the participation of these individuals in AFNs.

Analytical framework

The analytical framework we use for taking an inventory of our understanding has been thoroughly described, bearing in mind the empirical studies about the female prosumers’ role on organic farming and AFNs. This comprehensive structure holds together four main sections, and their respective subsections, as it is shown below in Figure 1.

Contextual factors

The role of participants in AFNs is influenced by contextual factors, which include social, economic (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017), environmental (Darnhofer et al., 2005) and political considerations (Karipidis and Karypidou, 2021). The sets and subsets of factors that impact farmers’ decisions related to the conversion of conventional farming activities to organic activities incorporated in the farm business decision framework are categorized as those located in the external farm business environment and those located in the internal environment (Karipidis and Karypidou, 2021). We gain profound insights into the way these elements mold and influence the position held by individuals within the realm of alternative food network through a comprehensive exploration of social factors, such as cultural mores, financial aspects, for example, market entry points, and governmental influences pertinent to motivations and certifications.

Participation and engagement

The participation and engagement of individuals are central to the analytical framework aiming to comprehend the part that they play within AFNs. This framework not only acknowledges the different types of activities in which the interviewee engages but also considers the obstacles they encounter and the motivations propelling their participation.

Those involved as producers/prosumers in these networks carry out diverse tasks, ranging from cultivation and production to distribution, alongside active networking (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017). Female producers also display versatile capacities in rural settings, taking on farm management roles, among other responsibilities (Davier et al., 2023). We stand better positioned toward gauging these activities’ actual influence upon food systems, both at micro and macro levels, by examining them more closely.

In spite of these obstacles, individuals exhibit an eagerness to participate in alternative food systems due to various incentives. Some are driven intrinsically by noble intentions revolving around environmental and social fairness; others by the desire to connect with local communities and positively influence local economics (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017). Having knowledge about what calls participants to action in these alternative food spaces will equip us with useful tactics to support them further.

In summary, the participation and engagement of them in AFNs is a critical aspect of the analytical framework for understanding the role of female producers/prosumers in these networks. This framework considers the activities in which they engage, the barriers they face and the motivations that drive their involvement. We can better understand the contributions individuals make to AFNs and develop plans for fostering female leadership and participation by looking at these elements.

Decision-making and leadership

The exploration of women’s decision-making and leadership skills plays an important role in the analytical framework seeking to comprehend their contributions as producers/prosumers within AFNs. This framework investigates how their involvement influences practices and procedures within the food system. The insights and experiences of individuals in AFNs can inform policy recommendations and support advocacy efforts, particularly when they engage with political networks and community organizations (Dhal et al., 2020; Malapit et al., 2020).

Engaging female participants in these deliberative sessions gain access to various perspectives and priorities which eventually foster impartial and sustainable measures (Metcalf et al., 2012; Nigh and González Cabañas, 2015). We can enhance our understanding of their impact on culinary provisions by examining particular processes where they lead or make choices. Those active within decision-making engagements contribute toward crafting more ecologically sound policies that aid both society and natural surroundings (Aguilar et al., 2015).

Studying the involvement of participants in administrative roles or decision-making within AFNs enhances our understanding of policy interventions in contemporary food systems. This knowledge helps us to identify strategies supporting and empowering individuals, while progressing towards impartial and environmentally sustainable food governance.

Impact and outcome

Participants’ involvement in entrepreneurial activities revolving around organic food networks holds considerable significance for examining how their influence shapes the system. Regarding such alternatives, emphasis is placed on analyzing both the fallout and result of the increased active role of them in AFNs. This study encompasses diverse shifts attributable to their participation, such as improvements in access to food, environmental sustainability and economic empowerment.

The participation of female in AFNs in United States has a significant positive effect on environmental sustainability (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017). Those in East London, specifically the Tower Hamlets area in these networks frequently place a higher priority on environmentally friendly methods of producing food and farming, such as organic farming, regenerative agriculture and waste-free initiatives (Metcalf et al., 2012).

One of the key impacts of their participation in AFNs is an increase in food access for communities that have been traditionally marginalized (Fourat et al., 2020). Individuals in AFNs often prioritize the production and distribution of locally grown and culturally appropriate foods, which can contextualize with food awareness, healthy nutrition, food waste avoidance, access to organic food to marginalized groups, and education (Canal Vieira et al., 2021).

The involvement of female in AFNs can also contribute to their financial freedom (Canal Vieira et al., 2021). Those in these networks frequently launch small businesses and engage in entrepreneurship, for example, by starting farmer’s markets or CSA programs (Aguilar et al., 2015). This can open up employment opportunities and help local economies become more sustainable and egalitarian.

In conclusion, one important part of the framework for understanding the role of women in these networks is the impact and results of their participation in AFNs. This approach takes into account the benefits of food access, environmental sustainability and economic empowerment that producers/prosumers bring to the food system through their engagement and participation in the AFNs.

Materials and methods

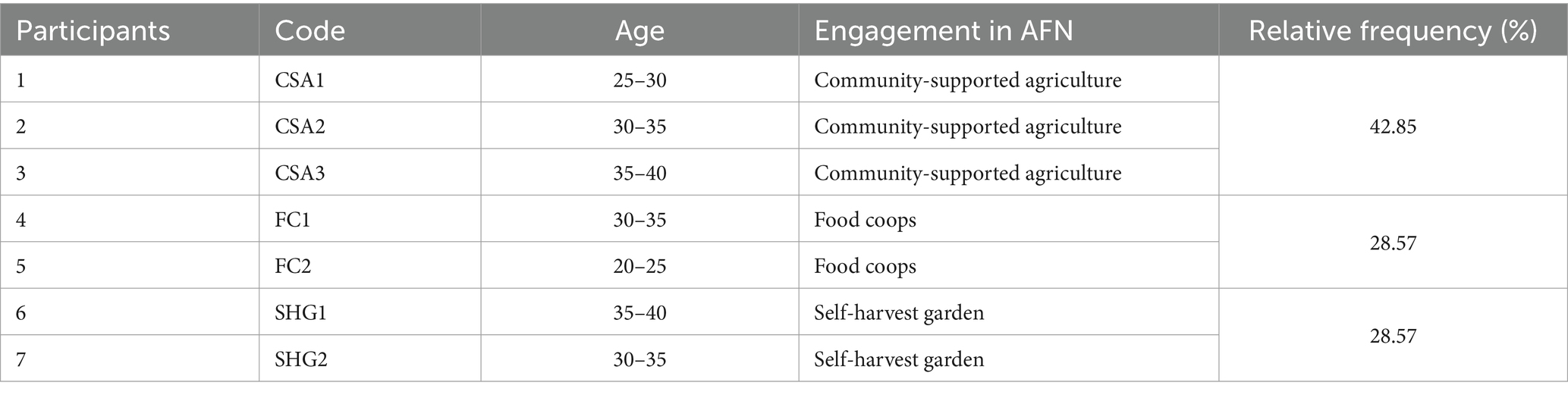

In order to answer our research questions, we conducted extensive research, which centered on interviewing female producers and consumers, specifically hybrid actors that we call “prosumers” (individuals) actively involved in organic farms within AFNs. We utilized a snowball sampling technique to ensure a deliberate selection of participants with diverse involvement in both organic farming and the AFNs. We managed to engage a total of seven interviewees for this study, all of whom had active affiliations with various agricultural communities, such as CSA, food cooperatives (FCs), and self-harvest gardens (SHGs). Each segment was represented by two participants, apart from CSA which contributed three interviewees. Explicit informed consent was sought from participants for the purposes of recording, transcription and potential publication in order to gain ethical clearance for this study. This demonstrates an ethical commitment to transparency, confidentiality and good practice throughout the research.

The existing literature describes roles among women concerning engagement in AFNs as producers (female farmers or farm workers), consumers, and those who link both domains – commonly termed as prosumers (consumers engaged in agricultural practices and/or distribution). Our focus in this study centered on individuals actively engaged in both production and consumption processes (prosumers) and those who have a clear focus in their professional role on production (producers). Hence, we deliberately selected our interviewees from this specific demographic identified as producers/prosumers, a term we will consistently employ throughout this article to refer to this dynamic group. To initiate the interview recruitment process, we reached out to potential participants by contacting them directly and inquiring about their willingness to contribute to our study. With this sample size, the participants expressed genuine interest in the topic. In this study the insights gained from participants contribute valuable qualitative data to the existing body of knowledge.

The study was carried out in the Berlin-Brandenburg region, which is known for its varied agricultural environment that includes both large-scale commercial farms and smaller organic and community-supported agricultural projects. This area is notable for the high degree of contact between the urban and rural areas and the growing interest in locally sourced and sustainable food systems. With its vast agricultural lands, Brandenburg serves as the production basis for organic produce, while Berlin, the capital city, offers a sizable market for it. Rich urban customers and rural farmers make up the socioeconomic landscape, which fosters a dynamic environment for AFNs. Agricultural collectivism in the area before reunification and the shift to market-based farming add levels of complexity to contemporary farming methods and community projects. It is important to comprehend this background since it affects women’s roles and participation in AFNs, affecting the opportunities and difficulties they encounter in this field.

The qualitative research methodology followed here involved conducting semi-structured interviews with 17 open-ended questions using a Zoom platform, except for three interviews which were conducted face-to-face. The manuscripts contain 39,509 words and each interview lasted between 50 min and an hour. Although this approach made it easier to reach individuals in diverse places, there were drawbacks as well, like the possibility of technological difficulties and a lack of face-to-face interaction. But Zoom’s utilization made it easier for participants to participate and reached a wider audience, which enhanced the quality of the data gathered.

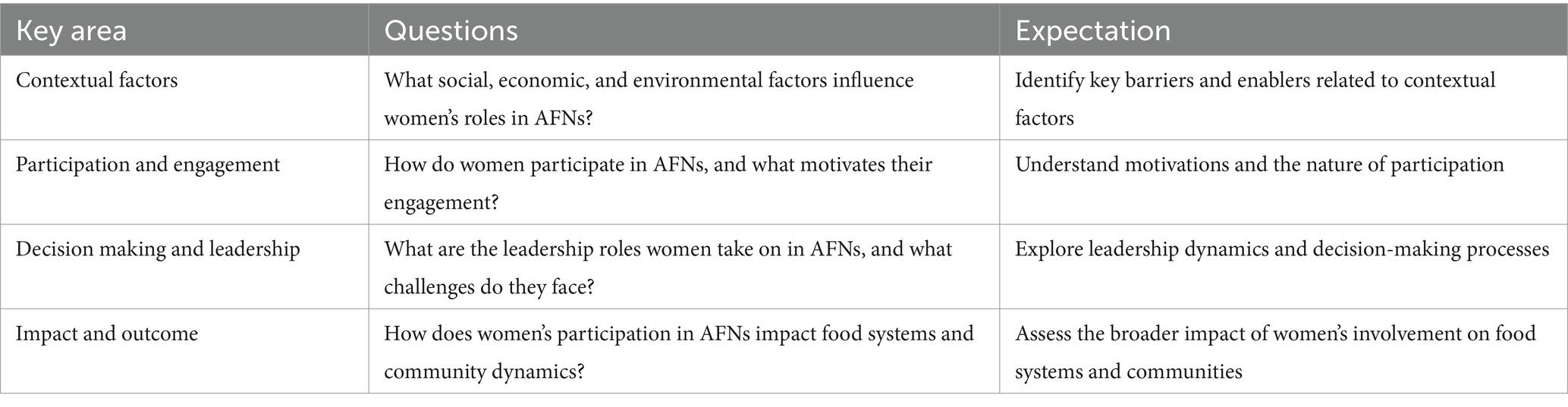

Prior consent was obtained from the participants before recording their conversations to ensure consistency in the language used during the analysis. The primary focus in the interviews was on posing questions to the participants regarding their involvement in (AFNs) and their experiences with organic farming. The key areas explored included the challenges they encountered in these pursuits and the limited engagement of female participants observed in both production and consumption aspects. Another major area of inquiry focused on assessing the decision-making capabilities within the framework of farming practices. The demographic section captured critical information, such as age, gender and involvement in organic farming activities. Analysis of the transcripts revealed three main ideas: participation, community, and leadership. Women’s participation in AFNs and their motivations, the impact of their involvement on community building, and the leadership roles they take on and the challenges they face were the primary focus areas explored in the research. We expected to uncover the specific challenges related to gender roles, recognition, and compensation within AFNs. The following table provides details regarding the research focus and correspondent expectations (see Table 1).

What we aimed to do in these interviews was twofold: firstly, to carefully understand the roles in terms of the woman themselves. Subsequently, actually exploring with the other participants the way they also saw these issues and what processes they are going through in their own work. Secondly, the participants gave us valuable insights by sharing their stories during the interview research, and what we have been able to uncover were perspectives that are derived from not only the path of their lives but also from their observations of people who are benefiting from the things that they are doing. Therefore, the first level of analysis, having collected the interview data, was to go through the interviews we recorded and transcribe them word-for-word. That became our basic data in conjunction with the analytical framework we developed. We then systematically identified the key parts of the transcript, identifying themes and elements and matched them up against the different sections of the analytics template.

The process of analysis was descriptive in nature and conducted manually. This was done to gain a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ viewpoints and narratives. It is important to mention that this study went through a very thorough content analysis process to make sure that it was able to provide as accurate data as possible by capturing emerging themes, patterns and subtle nuances within participants’ responses (Lindgren et al., 2020). We have carefully selected specific quotes from the interviews as references to provide clarity and support in order to articulate our findings. It is critical to consider that these quotes were used as references from each interview without changing the interviewee’s words or context. Using these precise quotations, this study has maintained a very strong sense of integrity and authenticity for the readers to fully understand the participants’ true perspectives.

Certain actions were undertaken to ascertain the trustworthiness and soundness of the qualitative analysis. During our careful and detailed analysis of the interview data, we coded the responses by systematically reviewing and sorting them into categories. We employed a series of coding procedures to ensure the reliability and quality of our analysis, implemented specific coding procedures and put rigorous quality assurance measures in place. This included cross-checking among coders to verify consistency and addressing any discrepancies through discussion and resolution.

To sum up, the participants in this research were carefully chosen. We undertook qualitative interviews with an extremely precise transcription technique, and analysis was done manually to the highest standard. We adopted this systematic methodology to thoroughly capture multifaceted views from female farmers who are particularly part of the organic farming in AFNs. We benefitted from this methodology, as the paper is filled with rich findings relating to the research questions.

Results

The findings underscore the significance of every factor that influences the participation of these producers/prosumers in the AFNs across these three initiatives. However, distinctions and commonalities come to light among these instances upon delving deeper into the analysis. This section explores the key elements of these deviations in greater detail. The following table provides sociodemographic details regarding those who were interviewed (see Table 2).

Contextual factor

The participation of individuals in AFNs and organic farming is shaped by various contextual factors, such as income, education, employment and health, family structure, farm structure and duration of organic farming practice. These factors significantly impact the role of female participants within AFNs. Those who have higher levels of income and better education are more inclined to engage in these activities to the fullest. Moreover, the existence of stable agricultural institutions and supporting family structures can help them participate. Additionally, individuals who have been involved in organic farming for a long time are more likely to make significant contributions to the development of a sustainable food system. They are empowered and given opportunities to advance sustainable agriculture methods when these social influences are taken into account.

“So, I think, if women really want, they have all the access they need but I believe that they will always have to work a little bit harder than men, to get, like, when even, when they have the knowledge to get access to markets and everything. I think it requires just more effort than it is for men because everything is, so male-dominated.” (FCI)

This highlights the additional effort women need to exert face in male-dominated sectors, requiring them to exert more effort than their male counterparts.

“I think it’s also kind of, how women are socialized, or how they’re taught to be as well as it’s men and how they’re taught to be, for example, like I try to make sure that I don’t just employ men, but if only men apply, obviously, I, I only have male applicants that it’s only going to be men doing the job. But I think that’s not necessarily because we scare off women, but because women sometimes feel they’re being told by the world that they’re not good enough for physical jobs or they’re not good enough for, I mean, one of the things that we write in our application is that job posting is that you have to drive a tractor, a small tractor, but it doesn’t matter if you don’t have any knowledge of this. We’re going to teach you, and I didn’t know how to drive. But I think it’s this thing where a lot of women think, oh, I, I can’t do that because they’ve been taught by the world that they don’t fit jobs like that or they can’t do jobs like that. So I think that’s one part, but it’s also, obviously things like, it’s also bigger societal problems. I’d say, I think its physical jobs are often taught to men and so like it’s this whole circle”. CSA2

The perceptions of these producers/prosumers regarding sustainable organic farming encompass various attributes, including educational attainment, active engagement in social activities, economic incentives, yearly income level, availability of information sources, involvement with extension personnel, willingness to embrace innovation and readiness to embrace risk (FC 2.1). The influence of social factors on engaged individuals’ roles within the AFNs and organic farming is evident.

“I think the main thing is that women have to form these spaces themselves. They have to fight for these spaces and like this, like a women’s gardening collective, they have to found this, shape this and work for this to be a safe feminist space that’s very aware and very like. And I think that there could be in all agricultural areas, it could be more work done from the men themselves as well. So, I feel like men could work more to form safe spaces for women or could maybe start the communication more or work with things. I mean, do workshops or whatever. There’s a lot to come from male-dominated companies as well, I’d say.” CSA3

Economic factors are another aspect shaping the role of women in AFNs and organic farming. The participants showed the economic shift of farming and nuanced understanding of this dynamic. Acknowledging the lessening of agriculture in economic effectiveness compared to the past, one participant outlines that making a living out of agriculture nowadays is a hard task, especially for them. The phrase “at the border somewhere” shows this sense of marginalization from the current economic system. Asking for governmental incentives and more assistance show this need for policy changes and the economic financing that the agricultural population deems necessary.

“Because farming is no longer such a big part of the economic world. It was different 50 years ago. So we just don’t do it. And other than that, there could also be government incentives. I mean, there can also always be funding projects maybe or like, yeah, I think there, there could always be more support from the government or more money from the government.” SGH2

Moreover, the interviewee highlights the unequal treatment of small-scale farmers who do not have access to government support rather than the government not having enough money to fund both. This participant notices how the extensive paperwork is the same whether the farm is large or small-scale. Twenty-six pages of standardized paperwork emphasizes how there needs to be a procedure in place regarding to the size of the operation. It relates to systemic equality and supporting the needs of farmers of various scales.

“It would be great to have support from the government. I think the normal government’s wish is not to have these small-scale farms. They want to have the big farms. And yeah, I think this is more the way. It would be great to have more support also for like in big farms, like all, all our neighbors have 2000 hectares. We have all the women in in the office doing all the paperwork and the smaller farms, we have to do the same amount of paperwork or where we have only one third of the land of them. But we have the same work because the papers have the same. It’s 26 pages. And, yeah, it would be good to have, a good access for, having paperwork, helping with bookkeeping stuff, taxes.” SHG2

The female participation in AFNs is important and should be supported by local politics and the government.

“I think it starts with the state, like the local politics, especially the agriculture departments. They can offer services for women, like information and workshops and but it, it is also down to the consumers. They can support women-owned businesses and farms. And not always looking at the, at the price of the food but, buying, for example, community-supported agriculture and supporting the whole farm and not just the product, so, that it’s like the best vegetables, the one that’s cheapest, that’s not always the best. And but also for other farmers and like to support the women around them and make it easier for them [the women] to establish a business.” (SHG1)

Participation and engagement

The AFN greatly values participation and engagement, recognizing the important role played by female participants in its various activities. In fact, there are instances where they show even higher levels of engagement compared to men (FC2). They contribute actively across multiple domains, including both administration and fieldwork. Especially when it comes to the latter, the interviewees display remarkable enthusiasm for participating in CSA, FCs and SHG activities. Their strong commitment to sustainability motivates them to participate eagerly in work in the field and show their willingness to operate machines.

“So, at our farm it’s very obvious that we have more women working in the administration and doing like office work. I mean, obviously the farm work is really hard work. I did it a few seasons and its super exhausting and like even the tools that we use, they are made for strong people, like some of the tools I couldn’t use because some often I was too weak to move things around and that makes everything extra hard. When the infrastructure around you is just not designed for you. And so, we had other women working at the farm. And they couldn’t do it for more than one season. And like many of them, they changed to a different farm. I still feel that, most men are more interested in machines and technical things. I mean, it’s also because, these are the stereotypes that we grew up with and, they became true for us that men are more the cars themselves and women are doing the office work. And, I mean, now we start, rethinking these patterns and these stereotypes but they are still the reality that we live with. And, it just takes time for, for this to change, to have women being more comfortable to work with machines and everything. But then also the machines need to be designed that anybody can work with them.” (CSA2)

Engaging with an AFN can greatly influence these producers/prosumers’ understanding of the social and environmental aspects of local food systems. This is because a considerable number of those involved choose to prioritize organic, nourishing foods for themselves and their children. Consequently, those who actively participate in AFNs are more inclined to support the sustainability of the food system.

“From my point of view, I noticed women being more interested in, local sustainable food systems. I think that there’s a very high potential in, in women to support these local networks and to support like transformation for more sustainable food systems, but also in other areas of society that that’s really great. I feel women are more concerned about the environment and also social aspects because we are community-supported agriculture.” (SCA3)

The engagement of female producers/prosumers in AFNs is closely linked to their individual values. Those who are involved in the production and consumption of food in Berlin Brandenburg tend to place a high priority on health and organic aspects. They also recognize the significance of sustainability and the impact of food on the environment and climate. Consequently, these producers/prosumers in the region value purchasing from farmers or producers who prioritize sustainable practices. This reflects a strong appreciation for sustainable approaches and environmental responsibility among them in Berlin Brandenburg, as pointed out by SHG 2 and SHG1.

In addition to their preference for organic food, engaged producers/prosumers are also involved in various activities within the AFN. They participate in CSA, farmers’ markets and community gardens, and they often play a key role in organizing these activities. They are also involved in food cooperatives, where they work together to purchase organic food in bulk, which helps to reduce the cost of organic food for everyone involved.

“I feel a lot of women I know personally are more interested in climate activism and sustainability and are more invested in, where does their food come from? And I think maybe it’s also this thing where a lot of women are also often societally pressured to be like very healthy. And I think maybe those two things connect with each other, and then there’s this thing that women are interested in sustainability. But then they’re also like very knowledgeable about regional produce and unhealthy vegetables and then these kind of intersect and then they get into organic produce.” SHG2

Furthermore, these producers/prosumers are also involved in the education and advocacy of organic farming and AFNs. They often organize workshops and training programs to teach others about organic farming, sustainable agriculture and the importance of supporting local food systems. Involved female producers/prosumers are also involved in policy advocacy, lobbying for policies that support organic farming and AFNs (FC2).

Participants play a pivotal role in various activities within the AFN. They actively contribute to administration, field work, sales and other areas. However, certain obstacles still hinder their full participation, such as household chores and childcare responsibilities. In addition, the design of certain machinery and equipment used in the field often cater solely to male users, making it challenging for them to engage in fieldwork. Despite these challenges, they continue to excel in diverse roles within the AFN.

“I think there is sometimes prejudice that women’s bodies are weaker than men. I have sometimes noticed that there’s like some work where my coworkers prefer to do with men because they are stronger. That’s one of these fake reasons to not employ women or to not really do work with women where it’s like, I consider myself pretty strong. And when I’ve worked with this women’s gardening collective in Berlin, I felt like they were all incredibly, like, physically able and had a very good stamina. And they do more physical work than we do. So, they were fitter than the men that I work with, I would say. So, I think that there’s this biological prejudice that’s kind of a problem in, in jobs that are physical.” (FC2)

In spite of the potential benefits AFNs offer, producers/prosumers encounter substantial barriers when it comes to participating and holding leadership roles within such networks. The persistence of gender stereotypes and discrimination poses one primary obstacle for their involvement in AFNs. These producers/prosumers, often perceived as caregivers and homemakers rather than leaders or entrepreneurs within the food system, may struggle to be taken seriously or obtain access to crucial resources and networks that are necessary for success in AFNs.

“Well, politics are also very male-dominated. So, they may not think of things that women need. I don’t think they do it on purpose that there are not really any differences, but maybe there should be more differences in how they support men and women because, as I mentioned, like the whole infrastructure is, is just not designed for women to work in agriculture.” (SHG2)

One more aspect to consider is that these individuals frequently encounter considerable time limitations and caregiving obligations. These factors can pose challenges when attempting to engage in the demanding, erratic timeframes often associated with various AFNs (CSA1). Moreover, they are more prone to experiencing harassment within their professional environment, especially in male-dominated fields such as agriculture and the food production sector (CSA2).

Each female producer/prosumer has a distinctive motivation to join AFNs and preference for organic crops. Overall, consumers seem to be drawn towards sustenance yielded by sustainable practices. They very often cite family health, particularly that of their children, as a crucial factor influencing their participation in AFNs. Their presence in different aspects of these networks is pronounced, with data suggesting more females on our food cooperative team compared to males.

It is important to note that while there is no clear data on whether they are more involved in the AFN than men, it is clear that women have made significant contributions to the growth and development of this movement. Many of the key players in the AFN, including farmers, organizers and advocates, are participants. Additionally, they have been instrumental in making the AFN more accessible and inclusive, particularly for marginalized communities (CSA2).

Recognizing the substantial contributions of these individuals within the AFN is crucial. Those in administrative positions bring important skill sets and views. These roles are essential for maintaining the organization and operation of many different projects. Particularly attending to the details, being able to communicate effectively and having the ability to multitask makes a great deal of difference in the success of administrative functions. Coordinating events, managing budgets and making collaborative meetings effective are examples of the types of tasks they are able to engage in successfully.

Furthermore, female producers/prosumers actively participate in field activities within the AFN. They play an essential role in cultivating, harvesting and processing food, as well as engaging in activities related to sustainable agriculture and organic farming. Their expertise in areas such as permaculture, crop rotation and agroforestry help to foster environmentally friendly practices within the network. Additionally, they contribute to CSA programs, farmers’ markets and food cooperatives, fostering local food systems and promoting access to nutritious and sustainable food (SHG2, FC1.2).

Impact and outcome

Female participants have a great potential in AFNs and organic farming. Their community engagement, organic preference, education and leadership are the skills that they bring with them to add value to the AFN.

In terms of environmentally friendly farming practices, young female farmers exhibit a greater level of concern than their male counterparts.

“I believe that women work more and think more about future generations and children and environment protection because we are more conscious about this fragile environment.” CSA3

The change towards climate action, sustainability, and food justice necessitates the active participation of women in agricultural growth and empowerment. Their involvement can make a big difference in promoting sustainable practices, guaranteeing a just and equitable food system, and reducing the effects of climate change.

“Women involvement in agriculture development and liberation is I think really important for achieving transformation towards the climate action, sustainability and food justice. Yeah, which can help to mitigate the effects of climate change.” CSA1

These producers/prosumers display a stronger inclination towards environmental activities. A case in point is the significantly higher degree of adoption of organic horticulture technologies among female farmers than male farmers. Furthermore, female farmers are more dominant in sustainable and organic farm operations than in industrial farming, and also demonstrate greater involvement in alternative agriculture initiatives. Additionally, organic farmers tend to be younger and more often women than conventional farmers (CSA1). Due to their multitasking responsibilities, these farmers need to balance family, childcare and farm work activities (Unay-Gailhard and Bojnec, 2021).

Decision-making and leadership

It is essential to acknowledge the significant role that participants play in influencing practices and informing policies. Despite the progress made, they continue to strive for visibility and actively contribute to shaping a better future for themselves.

“I feel a lot of women are very sustainable, like, very socially aware and very aware of many different political aspects because they themselves are political. Yeah, we still have many feminist fights. So, I think, there’s a large involvement definitely and I think we need generally more help from all sides but there’s already a large involvement.” CSA2

Individuals play an important role in AFNs and organic farming. Their contribution is essential to the success of the transformation of the food system. These producers/prosumers are involved in various aspects of AFNs and organic farming. They may, for instance, participate in seed-saving, food processing and preservation, market gardening or CSA. Participants have a deep understanding of local food systems and are responsible for preserving traditional food practices and knowledge.

“It’s my claim that we are more conscious about this fragile environment and that we have to and keep it balanced and we can’t take more out than we put in. I think this is normal that we just notice when we raise children and it’s the same when I raise calves and when I raise I, or when I let it grow, I don’t raise it, then I have to pull on it. And I think this is very transformative. Women are talking to each other more and we, and the knowledge exchange is faster.” (SHG1)

Innovation is another area where women in AFNs and organic farming excel. Women are often at the forefront of innovation (CSA2), experimenting with new techniques for soil conservation, developing new marketing strategies for their products and trying new approaches to growing food. Women-led cooperatives and collectives are becoming more common, providing a platform for women to collaborate and share resources (SHG1, CSA2).

The share of these members in the workforce of AFNs and organic farming is significant. They often take on the role of primary producers and prosumers, working long hours in the fields or food processing facilities. They are also involved in other aspects of the industry, such as research or policy development. However, women’s contributions are often undervalued and underpaid, and they may face discrimination and exclusion from decision-making processes.

“I feel like there’s just not a lot happening on a government level because I feel like the government’s priority is different subjects. I think it’s kind of like this whole, there’s of talk about land, about funding, about rules and lawmaking and policies in organic farming. And it’s also a lot about fair wages. And then like this whole like gender equality thing always feels kind of like an afterthought to me. It’s always like listed when we, when we do the demonstration with all the other tractors and people who do agriculture here. Then that’s always one of the parts on the agenda, but it’s always like a very small part if you know. So I think that the government has other priorities definitely.

And certainly, I think there’s having more women in leadership does bring new leadership styles. What I see in our cooperation is there’s quite or importance placed on communication, for example, having a clear feedback routine to make sure we’re actively learning with and from each other. I see a lot of potential just in terms of leadership styles and where emphasis is placed. Again, this is, you know, it’s my bias, my experience, but around inclusivity and equity simply.” (CSA1)

Discussion

This study aimed to address three research questions mentioned above. The findings presented here contribute to gaining a more comprehensive understanding of women’s roles in these types of initiatives.

Factors influencing the roles of female producers/prosumers in AFNs

Research indicates various factors influencing their participation in agriculture in Germany, particularly in pursuing farm manager or higher positions. Two key reasons are identified regarding this aspect: They anticipate fewer personal rewards from these roles and feel less confident in meeting job requirements due to cultural expectations, lack of role models, and challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities. Additionally, gender bias, limited access to resources and training, and differences in educational and professional experiences contribute to this lack of confidence. These factors collectively discourage them from seeking higher positions in agriculture, necessitating targeted interventions to promote gender equality and support their career advancement in this sector (Lehberger and Hirschauer, 2016).

The literature suggests that policymakers should prioritize enhancing women’s access to resources, education, training and credit facilities. This highlights the existing low demand and supply for participants involvement in the agricultural sector (Chebet, 2023). However, engagement in AFNs is fueled by diverse motivations, encompassing a quest for quality food, health considerations, and political or environmental awareness (Som Castellano, 2015). In contrast to traditional agricultural contexts, they have greater access to leadership roles in Alternative Food Networks (AFNs) due to cultural differences. AFNs promote inclusive and encouraging environments by putting a strong emphasis on teamwork, community involvement, and social justice. Community-supported agriculture (CSA) and food cooperatives, for instance, frequently feature democratic decision-making procedures and offer networking and mentorship opportunities, enabling women to assume leadership positions. On the other hand, they find it more difficult to progress in traditional agricultural environments because of the prevalence of hierarchical structures and gender biases. Consequently, AFN cultural norms and values give them greater chances to take on leadership roles and receive acknowledgement for their accomplishments.

Moreover, a notable increase in female participation in AFNs has been observed. This shift can be attributed to various factors, including the importance placed on family health, childcare, sustainability and environmental friendliness. Despite challenges in traditional agriculture, these initiatives showcase a positive trend in fostering a greater female engagement.

Research indicated a higher frequency of females participating in self-harvest gardening in Germany (Gauder et al., 2019). However, we observed that although there are a considerable number of women involved in this initiative, it was only acknowledged by the participants, and mentioned that it seems that recognizing the role of female in AFNs may not have been emphasized as an important topic.

The research explores various interrelated factors in Germany’s Alternative Food Networks (AFNs) that contribute to gender dynamics, such as the division of labor, access to resources, social recognition, and economic opportunities. It emphasizes that female producer/prosumers often handle the majority of the workload but struggle to gain the same level of recognition and support as men (Čajić et al., 2022). Our research supports these conclusions by presenting particular instances of individuals engaging in various AFN activities, such community service, and by emphasizing the additional difficulties and prejudices they encounter. The fact that they frequently have to put in more effort to receive the same recognition as men despite their great achievements highlights the need for institutional adjustments to encourage gender equality in AFNs.

Furthermore, economic factors significantly influence the role of women in shaping alternative food networks in Germany (Marks-Bielska, 2019). Our research produces similar results and it would be worth government exploring and implementing supportive policies, including streamlined paperwork processes and financial incentives for smaller-scale farms. Their participation, including the dissemination of information, workshops and financial aid programs, should be supported. Consumers also play a pivotal role by consciously choosing to support female-owned businesses and farms, fostering an environment where they can establish and sustain successful ventures in AFNs and organic farming.

As the consumer helps to blur the boundaries between traditional consumer and producer roles, the consumer plays a critical part in Alternative Food Networks (AFNs), helping to create the concept of “prosumers.” Through labor, decision-making, and distribution activities, consumers in AFNs actively participate in production processes including food cooperatives and community-supported agriculture (CSA). Individuals are empowered to directly impact the food system by their active engagement, which also supports sustainable practices.

Initiatives should challenge embedded gender stereotypes, providing opportunities for women to thrive in traditionally male-dominated sectors. Proactive measures are essential to create safe spaces for them, both through their own initiatives and with support from men in agricultural settings. Addressing dominant male norms and behaviors in agriculture is crucial for fighting gender inequalities. Our findings, highlighted the interviewees, emphasized the importance of recognizing and challenging these norms to promote gender equality. Focusing on gender relations and the impact of societal norms, this approach offers a broader understanding of the dynamics at play. It shifts the focus from solely female experiences to the interactions between genders, providing a more comprehensive strategy to combat gender inequalities in the agri-food sector.

Women’s roles in decision-making and leadership within AFNs and organic farming

Our study identifies specific criteria facilitating their participation as prosumers in AFNs. falling within a particular income bracket, coupled with significant maternal responsibilities and a commitment to organic and nutritious dietary habits, represent a notable segment. However, challenges emerge, particularly for low-income working mothers facing overwhelming physical, mental and emotional demands (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017). Participation in AFNs demands resources, time and dedication, underscoring the importance of accommodating diverse circumstances (Fourat et al., 2020).

Addressing infrastructural barriers and promoting environmental awareness, the literature shows that women are leaders in AFNs in Germany (Antal and Krebsbach-Gnath, 1993), and our study observed active involvement of them in AFNs. Still, they are facing some limitations that makes them unable to take more of a leadership part and decision-making as often.

The difficulties they encounter in achieving top leadership roles is partly based on the way tasks related to providing food are divided between genders, especially in AFNs (Som Castellano, 2016). There is a major barrier that prevents the full participation of women in AFNs, which lies in the limitations of infrastructures, with machinery and tools often constructed without any considerations of diverse physical abilities. Improvements to individual capacities and intra-household relationships are critical to supporting their participation and leadership in producer organizations (Kaaria et al., 2016). In order to overcome this, actions should involve the redesign of agricultural tools to be more inclusive, since targeted training is inadequate to encourage female participants’ confidence in interacting with machinery.

In addition, the AFNs can support informal caregivers by adopting flexible work practices by providing shorter, more intensive bursts of work as and when required and creating arrangements allowing workers to coordinate tasks with broader family responsibilities. These practices help in reducing the impact of time poverty, reflecting an understanding of the labor burden shouldered by them. As such, the prescriptive measures proffered here present a composite strategy designed to ensure their full and robust participation in AFNs. These measures respond to key findings which have consistently shown that women consumers want to do more rather than less in the AFN context. However, they are extremely aware of the very precise bounds within which they are required to operate. Achieving this participation requires a reassertion of the social contract between public and private provisioning. In the absence of this, we are left with seeking more localized and community-supported agricultural solutions.

differ from conventional gardening techniques or cultural symbolic activities historically linked to men (Metcalf et al., 2012). The particularities of the Berlin-Brandenburg area, especially the prevalence of large-scale farming, display barriers to female participants who endeavor to enter farming and establish their own farms. Issues such as poor soil and intense competition in the land market intensify these challenges. In comparison, in regions where family businesses dominate farming toil, women might bridge into these families and this way of farming more smoothly.

In order to gain a deeper understanding, it would be advisable to carry out a more expansive study which specifies factors such as gender within network structures, local food systems and CSA in AFNs as separate entrepreneurial expressions. This approach will contribute significantly to adopting a systematic perspective. Alternatively, exploring the dynamics in a different geographical location may yield valuable insights.

Impact of women’s participation in AFNs

The results of this research demonstrate some of the multiple effects that female engagement in AFNs have that go beyond only economic outcomes. Participants can improve local connections, community expansion and social cohesion. Some of the obstacles that they encounter include the possibility of over idealizing alternative strategies and restrictions in reaching alternative food products (Bruce and Som Castellano, 2017). Instead, their dedication to sustainable approaches helps to preserve health ecosystems and more sustainable food systems (Fourat et al., 2020).

It is essential to help participants to build strong community engagement and leadership capacities to make sure that they play a maximum role in community-engaged and leadership roles in AFNs and organic farming. Supporting individuals in their participation in the decision-making processes and leadership roles of AFNs is to strengthen not only resilience but also diversify perspectives that are crucial for sustainability. Making it easy for them to preference organic farming by creating educational initiatives and targeting resources will also make them become more capable of promoting the environmentally friendly practices, future-building and inclusiveness of AFNs.

Understanding the challenges of participants, such as balancing family responsibilities with farm work, is critical. To help them succeed, AFNs and organic farming need to introduce measures that proactively address these issues. That includes everything from flexible time schedules, daycare, and compensation that reflects farmers’ contributions. When we empower them in these sectors, their ability to lead profound change is increased. They will drive new environmentally resilient, community-focused agricultural practices.

To sum up, what this research found was the complicated nature of influences on participants’ roles in AFNs and organic farming. But the potential for change when they come together to shape more sustainable and more equal food systems also came through. Their contributions should never be taken for granted; they should be actively supported.

Conclusion

We employed a comprehensive analytical framework in our study to explore the integration of these prosumers into AFNs. What sets this study apart is its unique analytical framework, which thoroughly considers the varied positions of women in Berlin and Brandenburg. It becomes apparent that female prosumers confront distinct obstacles and gender-related issues, particularly when it comes to AFNs. Their participation in AFNs gains numerous advantages for the sustainability and well-being of agriculture. Their contributions extend beyond ecological aspects and encompass social elements, including fostering community connections and facilitating knowledge exchange.

Furthermore, their preference for organic produce and roles as mothers who advocate for healthier food choices underscore the importance of their involvement. In order to establish a more equitable and sustainable food system, it is crucial to address the hurdles faced by female prosumers in obtaining land, forming networks and accessing resources in organic farming. Governmental assistance must be tailored to accommodate small-scale farmers, especially women, by building upon their communities’ stabilizing capabilities. A collaborative approach with supportive networks can significantly mitigate these challenges while amplifying the voices of prosumers. Additionally, financial aid while instilling trust should be facilitated alongside customized regulations aligned to their particular needs.

Efforts in different initiatives demonstrate the potential for positive change and empowerment of female prosumers in AFNs. Promoting visibility, networking and providing resources, these initiatives contribute to a more inclusive and supportive environment for women prosumers in AFNs and organic farming. The interview subjects stressed the value of having more women in executive roles in the AFN value chains. They think that varied leadership may foster inclusivity and bring forward fresh viewpoints.

It is also crucial to put government policies and incentives to work in the AFN to advance gender equality. They think that by enacting these policies, more women will be inspired to succeed. Creating networks of support and promoting cooperation among them in agriculture and the AFN are essential. The growth and success of female participants in various fields can be facilitated by these networks, which can offer a forum for exchanging experiences, information and resources. It is essential to increase their access to resources such as land and finance. The respondents highlighted that in order to provide equitable possibilities, access barriers, such as a lack of knowledge, financial limitations and discriminatory practices, must be addressed.

It was also made clear that there is a need to confront and eliminate the prejudice and discrimination that individuals experience in agriculture and AFNs. This can be accomplished through educational initiatives and inclusive practices that support the equality of opportunity and treatment. Women in organic farming and the AFN can improve their knowledge, self-confidence and ability to thrive by developing mentorship programs and offering skill-building opportunities. The significance of encouraging to start their own businesses and develop new ideas in organic farming and the alternative food industry is crucial. They can create their own businesses and contribute to the growth and development if they are given access to capital, business training and mentorship.

It was stressed how important it is to develop markets for these prosumers in organic farming and AFNs. This can be accomplished by supporting female-owned businesses, local and sustainable produce, and collaborations with businesses and customers who value inclusion and gender equality. The interviewees proposed the development of specialized financial goods and services, such as cheap loans, grants and investment opportunities, suited to the requirements of women working in these sectors.

The interviewees talked about how vital it is to spread knowledge of the contributions and difficulties faced by women prosumers in the alternative food industry. They think that altering attitudes and beliefs about the functions and skills of these individuals will foster a more welcoming and inclusive environment for them in these fields. Taking these steps, the cooperative’s operations will be improved, issues experienced by women will be addressed, and inclusion, sustainability and resource access will be promoted. These activities also aim to address the underrepresentation of female prosumers in leadership roles.

This study is important because it explores new and unexamined aspects. It sheds light on the unique needs and challenges faced by women in the AFN, an area that has been overlooked in previous research. This study stands out as one of the few that has delved into the initiatives within the AFN. It underscores a crucial point – the gender perspective, particularly that of women, has been inadequately acknowledged both in academic studies and real-life scenarios.

The findings reveal a prevailing oversight in AFN initiatives, where the involvement and engagement of these individuals have not been recognized as significant issues. Historically, the focus has been on the tasks to be accomplished rather than considering who could contribute more effectively. A limitation of this study is the scarcity of literature on gender in AFNs in Germany. Expanding research in this area is essential to gain specific insights into the situations, needs and challenges faced by women in AFNs. Such an expansion could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the gender dynamics within the AFN and inform future policies and research endeavors.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. https://doi.org/10.4228/zalf-6qrj-sw78.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because All the interviewees provided oral consent, understanding that this research would present their responses anonymously.

Author contributions

FD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received from Philipp Schwartz Initiative of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation “Bridge Fellowship for Scholars from Afghanistan”, grant number: ZO1202224 for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to specifically express my gratitude towards the Humboldt Foundation for the generous fellowship as well as research support that allowed me to complete this research project. I am particularly thankful for the extensive guidance and persistent commitment provided by Annette Piorr at the Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research, throughout the entire research and writing process that enabled this work to be published. I would also like to thank Beatrice Walthall from the Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research for her contribution throughout the interviews while gathering the data. I would like to acknowledge the Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research for the opportunity to be employed by them. Finally, I would like to thank all interviewees for the knowledge they shared with us.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Food assemblies” typically refer to a model or platform that connects local farmers, producers and consumers in a community. These assemblies provide an online marketplace where consumers can purchase fresh, locally produced food items directly from farmers and producers in their area. This concept aims to strengthen local food systems, promote sustainable agriculture, reduce the environmental impact of food transportation, and foster a sense of community by encouraging direct relationships between producers and consumers. The term is often associated with the movement toward more transparent and localized food supply chains.

References

Aguilar, L., Molly, G., Cate, O., Prebble, M., and Westerman, K., (2015). Women in environmental decision making: Case studies in Ecuador, Liberia, and the Philippines. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Alberio, M., and Moralli, M. (2021). Social innovation in alternative food networks. The role of co-producers in Campi Aperti. J. Rural. Stud. 82, 447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.007

Alston, M., Clarke, J., and Whittenbury, K. (2018). Contemporary feminist analysis of Australian farm women in the context of climate changes. Soc. Sci. 7:16. doi: 10.3390/socsci7020016

Annes, A., Wright, W., and Larkins, M. (2021). ‘A woman in charge of a farm’: French women farmers challenge hegemonic femininity. Sociol. Rural. 61, 26–51. doi: 10.1111/soru.12308

Antal, A. B., and Krebsbach-Gnath, C. (1993). Women in Management in Germany: east, west, and reunited. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 23, 49–69. doi: 10.1080/00208825.1993.11656606

Barnett, M. J., Dripps, W. R., and Blomquist, K. K. (2016). Organivore or organorexic? Examining the relationship between alternative food network engagement, disordered eating, and special diets. Appetite 105, 713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.008

Blumberg, R. (2022). Engendering European alternative food networks through countertopographies: perspectives from Latvia. J. Anthropol. Food. 16. doi: 10.4000/aof.12865

Brinkley, C. (2018). The small world of the alternative food network. Sustain. For. 10:2921. doi: 10.3390/su10082921

Bruce, A. B., and Som Castellano, R. L. (2017). Labor and alternative food networks: challenges for farmers and consumers. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 32, 403–416. doi: 10.1017/S174217051600034X

Brückner, M., and Sardadvar, K. (2023). The hidden end of the value chain: potentials of integrating gender, households, and consumption into agrifood chain analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1114568. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1114568

Čajić, S., Brückner, M., and Brettin, S. (2022). A recipe for localization? Digital and analogue elements in food provisioning in Berlin a critical examination of potentials and challenges from a gender perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 29, 820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.025

Canal Vieira, L., Serrao-Neumann, S., and Howes, M. (2021). Daring to build fair and sustainable urban food systems: a case study of alternative food networks in Australia. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 45, 344–365. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2020.1812788

Chebet, N. (2023). The role of women on agricultural sector growth. IJA 8, 41–50. doi: 10.47604/ija.1980

Dahm, J., (2022a). Germany lags far behind on gender equality in agriculture, study finds – EURACTIV.com [WWW document]. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/germany-lags-far-behind-on-gender-equality-in-agriculture-study-finds/

Dahm, J., (2022b). Gemeinsame Agrarpolitik: Für Frauen “bleiben größere Hürden” [WWW Document]. Available at: https://www.euractiv.de/section/gap-reform/interview/gemeinsame-agrarpolitik-fuer-frauen-bleiben-groessere-huerden/ (Accessed July 18, 2024).

Darnhofer, I., Schneeberger, W., and Freyer, B. (2005). Converting or not converting to organic farming in Austria:farmer types and their rationale. Agric. Hum. Values 22, 39–52. doi: 10.1007/s10460-004-7229-9

Davier, Z., Padel, S., Edebohls, I., Devries, U., and Nieberg, H. (2023). Frauen auf landwirtschaftlichen Betrieben in Deutschland - Leben und Arbeit, Herausforderungen und Wünsche: Befragungsergebnisse von über 7.000 Frauen. Braunschweig: Thünen-Institut.

Dhal, S., Lane, L., and Srivastava, N. (2020). Women’s collectives and collective action for food and energy security: reflections from a Community of Practice (CoP) perspective. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 27, 55–76. doi: 10.1177/0971521519891479

Escobar-López, S. Y., Amaya-Corchuelo, S., and Espinoza-Ortega, A. (2021). Alternative food networks: perceptions in short food supply chains in Spain. Sustain. For. 13:2578. doi: 10.3390/su13052578

European Union (2018). Urban and peri-urban agriculture in the EU: Research for AGRI committee. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fourat, E., Closson, C., Holzemer, L., and Hudon, M. (2020). Social inclusion in an alternative food network: values, practices and tensions. J. Rural. Stud. 76, 49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.03.009

Gauder, M., Hagel, H., Gollmann, N., Stängle, J., Doluschitz, R., and Claupein, W. (2019). Motivation and background of participants and providers of self-harvest gardens in Germany. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 34, 534–542. doi: 10.1017/S174217051800008X

Jarosz, L. (2011). Nourishing women: toward a feminist political ecology of community supported agriculture in the United States. Gender Place Culture 18, 307–326. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2011.565871

Kaaria, S., Osorio, M., Wagner, S., Gallina, A., Kaaria, S., Osorio, M., et al., (2016). Rural women’s participation in producer organizations: an analysis of the barriers that women face and strategies to foster equitable and effective participation. J. Gend., Agric. Food Secur. (Agri-Gender).

Karipidis, P., and Karypidou, S. (2021). Factors that impact farmers’ organic conversion decisions. Sustain. For. 13:4715. doi: 10.3390/su13094715

Kessari, M., Joly, C., Jaouen, A., and Jaeck, M. (2020). Alternative food networks: good practices for sustainable performance. J. Mark. Manag. 36, 1417–1446. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1783348

Lehberger, M., and Hirschauer, N. (2016). Recruitment problems and the shortage of junior corporate farm managers in Germany: the role of gender-specific assessments and life aspirations. Agric. Hum. Values 33, 611–624. doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9637-4

Lindgren, B.-M., Lundman, B., and Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 108:103632. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

Malapit, H., Meinzen-Dick, R. S., Quisumbing, A. R., and Zseleczky, L., (2020). Women: transforming food Systems for Empowerment and Equity, in: In 2020 global food policy report, International food policy research institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC, Pp. 36–45.

Marks-Bielska, R. (2019). Factors underlying the economic migration of German women to Poland. OEJ 14, 145–155. doi: 10.31648/oej.3967

Medici, M., Canavari, M., and Castellini, A. (2023). An analytical framework to measure the social return of community-supported agriculture. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 47, 1319–1340. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2023.2236989

Meena, L., Panwar, A. S., Dutta, D., Ravisankar, N., Amit, K., and Meena, A., (2019). Modern concepts and practices of organic farming for safe secured and sustainable food production. India: ICAR Indian Institute of Farming Systems Research.

Metcalf, K., Minnear, J., Kleinert, T., and Tedder, V. (2012). Community food growing and the role of women in the alternative economy in tower hamlets. Local Econ. 27, 877–882. doi: 10.1177/0269094212455290