- 1Weymouth Laboratory, Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS), Weymouth, United Kingdom

- 2Centre for Sustainable Aquaculture Futures, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

- 3Biosciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

- 4The Roslin Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 5Institute of Aquaculture, Pathfoot Building, University of Stirling, Stirling, United Kingdom

- 6Soulfish Research and Consultancy, York, United Kingdom

- 7Department of Botany, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 8Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Food Systems, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 9Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Pretoria, South Africa

Aquaculture now provides half of all aquatic protein consumed globally—with most current and future production occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Concerns over the availability and application of effective policies to deliver safe and sustainable future supply have the potential to hamper further development of the sector. Creating healthy systems must extend beyond the simple exclusion of disease agents to tackle the host, environmental, and human drivers of poor outcomes and build new policies that incorporate these broader drivers. Syndemic theory provides a potential framework for operationalizing this One Health approach.

What is a syndemic?

Syndemic theory extends our interpretation of disease beyond traditional medical definitions of morbidity, co-morbidity, and multi-morbidity to include societal, economic, and environmental drivers contributing to, and exacerbating, detrimental health outcomes (Singer et al., 2017). This “biosocial” concept of disease, first applied to SAVA (substance abuse, violence, and AIDS) in individuals and groups from low-income urban environments (Singer, 1996), has subsequently been deployed where infectious and non-infectious conditions interface with prevailing political, societal, and environmental factors (Moussavi et al., 2007; Zinsstag et al., 2011; Mendenhall, 2013). Syndemic theory was re-animated by the COVID-19 pandemic, with a diverse outcome disease state associated with infection by a novel viral pathogen and the differing political, environmental, and demographic landscapes operating across susceptible human host communities (Mendenhall, 2020; Fronteira et al., 2021). Syndemic theory has important consequences for human health policy, identifying the need to move beyond biomedical intervention to simultaneously focus on tackling socio-economic disparities underlying poor health (Singer et al., 2017; Horton, 2020).

Syndemic pathways in aquaculture

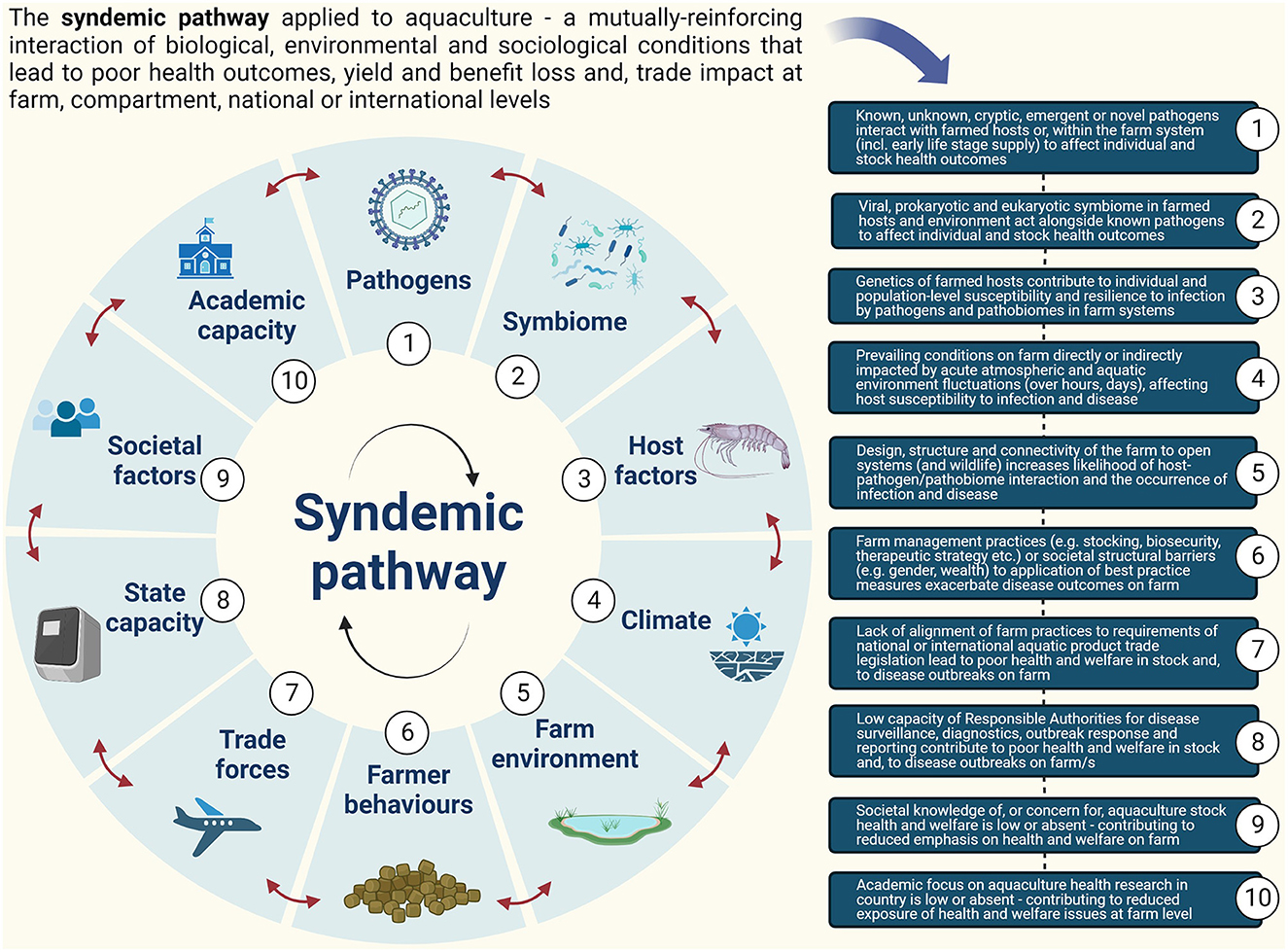

In this study, we consider how syndemic theory may be applied elsewhere—specifically, to animal health outcomes within food systems. Aquaculture, one of the fastest-growing food sectors, predominates in LMICs (Stentiford and Holt, 2022). Interacting biological, environmental, social, and political factors have contributed to diseases that have seriously limited yield, benefits, profit, and food security from the sector, both in LMICs and in higher-income nations, over recent decades (Faruk et al., 2004; Solomieu et al., 2015; Abolofia et al., 2017; Tang and Bondad-Reantaso, 2019; Stentiford et al., 2020, 2022; Patil et al., 2021; Ward et al., 2021). The role of animal disease as a poverty trap for LMIC farmers, in particular, has been discussed in this context—an improved biosocial evidence basis to understand causality, to design policy, and to drive public–private investment are cornerstones of the Global Burden of Animal Diseases (GBAD) approach to reducing risk (Huntington et al., 2021; Rushton et al., 2021). The discourse on the role of disease in aquaculture has shifted focus from the presence of the pathogen (Stentiford et al., 2017) to the traditional epidemiological triad model for disease (Snieszko, 1974) revised to acknowledge that hosts and pathogens are elements of, and not distinct from, the environment (Dohoo et al., 2009). However, now the need to extend beyond this paradigm seems critical for averting losses (Stentiford et al., 2020). Instead, we propose that a “syndemic pathway” is driving poor health outcomes in aquaculture (Figure 1), and we urge that wider-ranging factors from biological to systemic failings of the institutional environment be incorporated into national strategies aimed at underpinning sustainability in the sector.

Pathogens

Diverse pathogen taxa are implicated in aquaculture disease outbreaks, with international legislation aimed at limiting the spread and further establishment of specific (listed) diseases (i.e., transboundary diseases) via the trade in animals and products (WOAH, 2022). Single pathogens are important in syndemic pathways (Munkongwongsiri et al., 2022; Niu et al., 2022), but the need for wider consideration of the symbiome within which known pathogens exist is acknowledged (Bass et al., 2019). In aquaculture, disrupted endemic microbial consortia co-contribute to “crop production” (non-listed) diseases that are significant drivers of farm losses (Kooloth Valappil et al., 2021; Delisle et al., 2022). Diagnostic innovations used to profile these consortia in hosts, feeds, and water are influencing better microbial management practices on the farm, which leads to improved health, welfare, and yield (Bentzon-Tilia et al., 2016; Heyse et al., 2021; Holt et al., 2021). For averting syndemic pathways in aquaculture, profiling (and managing) microbial consortia conducive to healthy outcomes is likely to be as important as doing so during outbreaks (Elements 1 and 2, Figure 1).

Hosts

Sub-optimal water quality, nutrition, and the microbial ecosystem catalyse disease outbreaks in susceptible hosts (Murray and Peeler, 2005; Bateman et al., 2020). Susceptibility is also rooted in the genetics of farmed individuals and populations at local, national, and global levels. Selective breeding (Gjedrem and Rye, 2018; Houston et al., 2020), gene editing (Gratacap et al., 2019; Potts et al., 2021), and vaccinology (Ma et al., 2019) are critical tools for promoting health (Stentiford et al., 2017, 2020)—resilient populations being those in which effective genetic management reduces disease burden, reduces susceptibility to environmental change, and maintains diversity (You and Hedgecock, 2018). Resilience extends beyond single traits (Frank-Lawale et al., 2014), but it can be situation specific. For example, genetics for environmentally controlled biosecure farming may focus on enhanced growth traits, whilst for open systems, resilience to multiple stressors, and pathogens in combination may be required (Sae-Lim et al., 2016; Houston et al., 2020). Understanding functional bases for genetic resilience in major farmed aquatic species across the range of environments in which they are cultured is a critical component for sustainability in the sector (Element 3, Figure 1).

Environment

The immediate farm environment, farm management practices, and the impact of high-level forcing factors (e.g., climate change) play key roles in aquaculture syndemic pathways (Naylor et al., 2021; Panicz et al., 2022). On farms, sub-optimal water quality causes physiological stresses that can lead to immunological damage to stock, whilst also driving pathogen virulence (Kennedy et al., 2016). Farming intensity (Oddsson, 2020), mismanagement of waste (Granada et al., 2016), and poor biosecurity (Subasinghe et al., 2019; Reverter et al., 2020; Stentiford et al., 2020, 2022) combine to create conditions conducive to disease. Vulnerability to outbreaks is further compounded by the incursion of wildlife and vegetation, surrounding land use, pollution, erosion, and the presence of disease vectors (Soto et al., 2019; Bouwmeester et al., 2021; Stentiford et al., 2022). Preventing the development of syndemic pathways in aquaculture requires minimizing the impact of these complex environmental factors on the farmed stock. Spatial planning is critical to ensuring that aquaculture develops where environmental impacts on and from aquaculture are minimal. In some cases, physical separation of the farm from the environment or emerging precision technologies is needed to minimize environmental interactions (Føre et al., 2018) (Elements 4, 5, Figure 1).

People and society

The socio-cultural and economic context sets rules and enforcement mechanisms that shape a very specific institutional environment (Rushton and Leonard, 2009). This can create structural barriers (e.g., gender, language, knowledge, wealth, age, and access to facilities) that prevent farm operatives from obtaining adequate training and adopting practices to de-risk production. These barriers exacerbate pathogen, host, and environmental elements of the syndemic pathway—and vice versa, resulting in catastrophic disease losses in the sector (Kumar and Engle, 2016). Farmer behavior also directly influences the effectiveness of disease management and reporting decisions (Brugere et al., 2017; Hidano et al., 2018). The globalized nature of trade and diversity in forms of seafood consumption increase the risk of disease spread and exposure to human pathogens (Macpherson, 2005; Rodgers et al., 2011; FAO, 2012, 2020; Rinanda, 2015; Stentiford et al., 2022). National policy choices and priorities for disease surveillance, reporting, and control (including compensation for lost income), investments in animal health research, standard enforcement (notably regulation of trade), choice of farmed species, land use planning, and development (e.g., location of farms in the wider landscape), and public health policies and institutions' funding and outreach are often insufficient and disharmonized (van Herten et al., 2019; FAO, 2020). This not only has direct negative outcomes for animal and human health (Rushton et al., 2007) but also catalyses the formation of syndemic pathways that indirectly impact human prosperity (Elements 6–10, Figure 1).

Averting syndemic pathways

Whilst control of disease in aquaculture is a responsibility shared by the government and producers, the operationalization of One Health Aquaculture (Stentiford et al., 2020) can only be led by the government. By holistically conceptualizing human, environmental, and organism health, the syndemic pathway provides a framework for the government to operationalize One Health Aquaculture. Alongside national aspirations for expanded aquaculture output (Stentiford and Holt, 2022), it should catalyze the co-development of policies that extend well beyond attempts to exclude or manage the hazard (pathogen) to ones that drive investment in developing resilient hosts, protecting farms from the environment, and (particularly) exposing the core potential of humans operating within food systems to avert syndemic pathways from forming (Brugere et al., 2017).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. CT: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. RE: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. TB: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. SM: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. CB: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. CH: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. EP: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. KC: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. JR: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. DB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, UK Government under contracts FX001, FD002, and C8376 to GS, EP, and DB.

Conflict of interest

CB was employed by Soulfish Research and Consultancy.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abolofia, J., Asche, F., and Wilen, J. E. (2017). The cost of lice: quantifying the impacts of parasitic sea lice on farmed salmon. Mar. Res. Econ. 32, 329–349. doi: 10.1086/691981

Bass, D., Stentiford, G. D., Wang, H. C., Koskella, B., and Tyler, C. (2019). The Pathobiome in animal and plant diseases. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 34, 996–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2019.07.012

Bateman, K. S., Bignell, J. P., Feist, S. W., Bass, D., and Stentiford, G. D. (2020). “Marine pathogen diversity and disease outcomes,” in Marine Disease Ecology, eds. C. Donald, D. C. Behringer, B. R. Silliman, K. D. Lafferty (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198821632.003.0001

Bentzon-Tilia, M., Sonnenschein, E. C., and Gram, L. (2016). Monitoring and managing microbes in aquaculture - towards a sustainable industry. Microb. Biotechnol. 9, 576–584. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12392

Bouwmeester, M. M., Goedknegt, M. A., Poulin, R., and Thieltges, D. W. (2021). Collateral diseases: aquaculture impacts on wildlife infections. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 453–464. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13775

Brugere, C., Onuigbo, D. M., and Morgan, K. L. (2017). People matter in animal disease surveillance: Challenges and opportunities for the aquaculture sector. Aquaculture. 467, 158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.04.012

Delisle, L., Laroche, O., Hilton, Z., Burguin, J. F., Rolton, A., Berry, J., et al. (2022). Understanding the dynamic of POMS infection and the role of microbiota composition in the survival of Pacific Oysters, Crassostrea gigas. Microbiol. Spectr. 31, e0195922. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01959-22

Dohoo, I., Martin, W., and Stryhn, H. (2009). Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. VER Inc. ISBN 10:0919013600,0919013865.

FAO (2012). Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nation (FAO), 2012 The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Available online at: www.fao.org/docrep/016/i2727e.pdf (accessed June 2, 2022).

Faruk, M. A. R., Sarker, M. M. R., Alam, M. J., and Kabir, M. B. (2004). Economic loss from fish diseases on rural freshwater aquaculture of Bangladesh. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 2086–2091. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2004.2086.2091

Føre, M., Frank, K., Norton, T., Svendsen, E., Alfredsen, J. A., Dempster, T., et al. (2018). Precision fish farming: A new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Engineer. 173, 176–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.10.014

Frank-Lawale, A., Allen, S. K., and Dégremont, L. (2014). Breeding and domestication of eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) lines for culture in the mid-Atlantic, USA: line development and mass selection for disease resistance. J. Shellfish Res. 33, 153–165. doi: 10.2983/035.033.0115

Fronteira, I., Sidat, M., Magalhães, J. P., Cupertino de Barros, F. P., Delgado, A. P., Correia, T., et al. (2021). The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A syndemic perspective. One Health. 12, 100228. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100228

Gjedrem, T., and Rye, M. (2018). Selection response in fish and shellfish: a review. Rev. Aquacult. 10, 168–179. doi: 10.1111/raq.12154

Granada, L., Sousa, N., Lopes, S., and Lemos, M. F. (2016). Is integrated multitrophic aquaculture the solution to the sectors' major challenges? A review. Rev. Aquacult. 8, 283–300. doi: 10.1111/raq.12093

Gratacap, R. L., Wargelius, A., Edvardsen, R. B., and Houston, R. D. (2019). Potential of genome editing to improve aquaculture breeding and production. Trends Genet. 35, 672–684. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.06.006

Heyse, J., Props, R., Kongnuan, P., De Schryver, P., Rombaut, G., Defoirdt, T., et al. (2021). Rearing water microbiomes in white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) larviculture assemble stochastically and are influenced by the microbiomes of live feed products. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 281–298. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15310

Hidano, A., Enticott, G., Christley, R. M., and Gates, M. C. (2018). Modeling dynamic human behavioral changes in animal disease models: challenges and opportunities for addressing bias. Front. Vet. Sci. 5, 137. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00137

Holt, C. C., Bass, D., Stentiford, G. D., and van der Giezen, M. (2021). Understanding the role of the shrimp gut microbiome in health and disease. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 186, 107387. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107387

Horton, R. (2020). Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet 396, 10255–10874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6

Houston, R. D., Bean, T. P., Macqueen, D. J., Gundappa, M. K., Jin, Y., Jenkins, T. L., et al. (2020). Harnessing genomics to fast-track genetic improvement in aquaculture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 389–409. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-0227-y

Huntington, B., Bernardo, T. M., Bondad-Reantaso, M., Bruce, M., Devleesschauwer, B., Gilbert, W., et al. (2021). Global Burden of Animal Diseases: a novel approach to understanding and managing disease in livestock and aquaculture. Rev. Sci. Tech. 40, 567–584. doi: 10.20506/rst.40.2.3246

Kennedy, D. A., Kurath, G., Brito, I. L., Purcell, M. K., Read, A. F., Winton, J. R., et al. (2016). Potential drivers of virulence evolution in aquaculture. Evolut. Applic. 9, 344–354. doi: 10.1111/eva.12342

Kooloth Valappil, R., Stentiford, G. D., and Bass, D. (2021). The rise of the syndrome–sub-optimal growth disorders in farmed shrimp. Rev. Aquacult. 13, 1888–1906. doi: 10.1111/raq.12550

Kumar, G., and Engle, C. R. (2016). Technological advances that led to growth of shrimp, salmon, and tilapia farming. Rev. Fish Sci. Aquacult. 24, 136–152. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2015.1112357

Ma, J., Bruce, T. J., Jones, E. M., and Cain, K. D. (2019). A review of fish vaccine development strategies: Conventional methods and modern biotechnological approaches. Microorganisms. 7, 569. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7110569

Macpherson, C. N. L. (2005). Human behaviour and the epidemiology of parasitic zoonoses. Internat. J. Parasitol. 35, 1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.06.004

Mendenhall, E. (2013). Syndemic Suffering: Social Distress, Depression, and Diabetes Among Mexican Immigrant Women. Walnut Creak, CA: Left Coast, Press.

Mendenhall, E. (2020). The COVID-19 syndemic is not global: context matters. Lancet. 396, 1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32218-2

Moussavi, S., Chatterji, S., Verdes, E., Tandon, A., Patel, V., Ustun, B., et al. (2007). Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health surveys. Lancet. 370, 851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9

Munkongwongsiri, N., Prachumwat, A., Eamsaard, W., Lertsiri, K., Flegel, T. W., Stentiford, G. D., et al. (2022). Propionigenium and Vibrio species identified as possible component causes of shrimp white feces syndrome (WFS) associated with the microsporidian Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 192, 107784. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2022.107784

Murray, A. G., and Peeler, E. J. (2005). A framework for understanding the potential for emerging diseases in aquaculture. Prevent. Vet. Med. 67, 223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.10.012

Naylor, R. L., Hardy, R. W., Buschmann, A. H., Bush, S. R., Cao, L., Klinger, D. H., et al. (2021). A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature. 591, 551–563. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03308-6

Niu, G. J., Yan, M., Li, C., Lu, P. Y., Yu, Z., and Wang, J. X. (2022). Infection with white spot syndrome virus affects the microbiota in the stomachs and intestines of kuruma shrimp. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 156233. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156233

Oddsson, G. V. A. (2020). definition of aquaculture intensity based on production functions—The aquaculture production intensity scale (APIS). Water. 12, 765. doi: 10.3390/w12030765

Panicz, R., Całka, B., Cubillo, A., Ferreira, J. G., Guilder, J., Kay, S., et al. (2022). Impact of climate driven temperature increase on inland aquaculture: application to land-based production of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L). Trans. Emerg. Dis. 69, e2341–e2350. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14577

Patil, P. K., Geetha, R., Ravisankar, T., Avunje, S., Solanki, H. G., Abraham, T. J., et al. (2021). Economic loss due to diseases in Indian shrimp farming with special reference to Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) and white spot syndrome virus (WSSV). Aquaculture. 533, 736231. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736231

Potts, R. W. A., Gutierrez, A. P., Penaloza, C. S., Regan, T., Bean, T. P., Houston, R. D., et al. (2021). Potential of genomic technologies to improve disease resistance in molluscan aquaculture. Phil. Transact. Roy. Soc. B. 376, 20200168. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0168

Reverter, M., Sarter, S., Caruso, D., Avarre, J. C., Combe, M., Pepey, E., et al. (2020). Aquaculture at the crossroads of global warming and antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Comm. 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15735-6

Rinanda, T. (2015). Aquatic animals and their threats to public health at human-animal-ecosystem interface: a review. AACL Bioflux. 8, 784–789.

Rodgers, C. J., Mohan, C. V., and Peeler, E. J. (2011). The spread of pathogens through trade in aquatic animals and their products. OIE Scient. Techn. Rev. 30, 241–256. doi: 10.20506/rst.30.1.2034

Rushton, J., Huntington, B., Gilbert, W., Herrero, M., Torgerson, P. R., Shaw, A. P. M., et al. (2021). Roll-out of the global burden of animal diseases programme. Lancet 397, 1045–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00189-6

Rushton, J., and Leonard, D. (2009). “New institutional economics and the assessment of disease control,” in The Economics of Animal Health and Production, ed. J. Rushton (Wallingford, UK: CABI) 144–148. doi: 10.1079/9781845931940.0144

Rushton, J., Viscarra, R., Otte, J., McLeod, A., and Taylor, N. (2007). Animal health economics where have we come from and where do we go next? CABI Rev. 2, 10. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR20072031

Sae-Lim, P., Gjerde, B., Nielsen, H. M., Mulder, H., and Kause, A. (2016). A review of genotype-by-environment interaction and micro-environmental sensitivity in aquaculture species. Rev. Aquac. 8, 369–393. doi: 10.1111/raq.12098

Singer, M. (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq. Creat. Sociol. 24, 99–110.

Singer, M., Bulled, N., Ostrach, B., and Mendenhall, E. (2017). Syndemics and the biosocial concept of health. Lancet. 389, 941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X

Snieszko, S. F. (1974). The effects of environmental stress on outbreaks of infectious diseases of fishes. J. Fish Biol. 6, 197–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1974.tb04537.x

Solomieu, V. B., Renault, T., and Travers, M.-A.. (2015). Mass mortality in bivalves and the intricate case of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 131, 2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.011

Soto, D., León-Muñoz, J., Dresdner, J., Luengo, C., Tapia, F. J., and Garreaud, R. (2019). Salmon farming vulnerability to climate change in southern Chile: understanding the biophysical, socioeconomic and governance links. Rev. Aquacult. 11, 354–374. doi: 10.1111/raq.12336

Stentiford, G. D., Bateman, I. J., Hinchliffe, S. J., Bass, D., Hartnell, R., Santos, E. M., et al. (2020). Sustainable aquaculture through the One Health lens. Nat. Food. 1, 468–474. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0127-5

Stentiford, G. D., Flegel, T. W., Bass, D., Williams, B. A., Withyachumnarnkul, B., Itsathitphaisarn, O., et al. (2017). New paradigms to solve the global aquaculture disease crisis. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006160. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006160

Stentiford, G. D., and Holt, C. (2022). Global adoption of aquaculture to supply seafood. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 041003. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac5c9f

Stentiford, G. D., Peeler, E. J., Tyler, C. R., Bickley, L. K., Holt, C., Bass, D., et al. (2022). A seafood risk tool for assessing and mitigating chemical and pathogen hazards in the aquaculture supply chain. Nat. Food. 3, 169–178. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00465-3

Subasinghe, R. P., Delamare-Deboutteville, J., Mohan, C. V., and Phillips, M. J. (2019). Vulnerabilities in aquatic animal production. Rev. Scientif. Tech. 38, 423–436. doi: 10.20506/rst.38.2.2996

Tang, K. F. J., and Bondad-Reantaso, M. G. (2019). Impacts of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease on commercial shrimp aquaculture. Rev. Sci. Tech. 38, 477–490. doi: 10.20506/rst.38.2.2999

van Herten, J., Bovenkerk, B., and Verweij, M. (2019). One Health as a moral dilemma: Towards a socially responsible zoonotic disease control. Zoonoses Public Health. 66, 26–34. doi: 10.1111/zph.12536

Ward, G. M., Kambey, C. S. B., Faisan, J. P., Tan, P.-L., Matoju, I., Stentiford, G. D., et al. (2021). Ice-ice disease: an environmentally and microbiologically driven syndrome in tropical seaweed. Rev. Aquacult. 14, 414–439. doi: 10.1111/raq.12606

WOAH (2022). Aquatic Animal Health Code, World Organisation for Animal Health, online publication, Paris. Avaiolable online at: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/aquatic-code-online-access/ (accessed June 2, 2022).

You, W., and Hedgecock, D. (2018). Boom-and-bust production cycles in animal seafood aquaculture. Rev. Aquacult. 11, 1045–1060. doi: 10.1111/raq.12278

Keywords: aquaculture, food, disease, sustainable, health

Citation: Stentiford GD, Tyler CR, Ellis RP, Bean TP, MacKenzie S, Brugere C, Holt CC, Peeler EJ, Christison KW, Rushton J and Bass D (2023) Defining and averting syndemic pathways in aquaculture: a major global food sector. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1281447. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1281447

Received: 22 August 2023; Accepted: 08 September 2023;

Published: 28 September 2023.

Edited by:

Kwasi Adu Adu Obirikorang, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GhanaReviewed by:

Prasanna Patil, Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (ICAR), IndiaCopyright © 2023 Stentiford, Tyler, Ellis, Bean, MacKenzie, Brugere, Holt, Peeler, Christison, Rushton and Bass. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Grant D. Stentiford, grant.stentiford@cefas.gov.uk; @CefasChiefSci

Grant D. Stentiford

Grant D. Stentiford Charles R. Tyler

Charles R. Tyler Robert P. Ellis

Robert P. Ellis Tim P. Bean

Tim P. Bean Simon MacKenzie

Simon MacKenzie Cecile Brugere

Cecile Brugere Corey C. Holt7

Corey C. Holt7 Jonathan Rushton

Jonathan Rushton David Bass

David Bass