- 1Bieler School of Environment, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 3Leadership and Learning for Sustainability Lab, Department of Integrated Studies in Education, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Introduction: Student-run Campus Food Systems Alternatives (CFSA) have been proposed as spaces which have the potential to advance Critical Food Systems Education (CFSE) – the objective of which is to motivate students to act toward radical food systems transformation on community and systemic levels. Evidence on how learning dynamics in CFSA drive student participants to develop critical perspectives on food systems is limited, however. This paper seeks to address this gap by exploring how critical and transformative learning happens in these informal and student-run spaces, by detailing a multi-case study of students’ learning experiences in four student-run CFSA on the McGill University campus.

Methods: Data on students’ learning experiences was collected through observational field notes of CFSA activities and semi-structured Interviews with student facilitators. Thematic and cross-case analysis was performed with interview data.

Results: Analysis of students’ described learning experiences in CFSA revealed three broad categories of learning dynamics which drive students’ learning about food systems and their willingness to act for food systems change: hands-on work in informal spaces, social connection and engagement between student participants, and engagement with the beyond-campus community.

Discussion: Engagement with the beyond-campus community via CFSA, particularly that which involved exposure to food-related injustice in marginalized communities, was found to be particularly important in driving student participants’ critical reflection on food systems and willingness to act toward food justice. A lack of intentional critical reflective practice was however observed in CFSA, calling into question how this practice can be driven in campus food initiatives without compromising their student-run and informal structures.

1. Introduction

In the context of the climate crisis and growing global food insecurity, a widespread and holistic transformation of the industrial global food system is being called for Ruben et al. (2021); IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute) (2022). Education has long been identified as a key tool for enacting social change by enabling students with critical knowledge to transgress and radically transform oppressive power structures in their societies (Freire, 1970; Hooks, 1994). Given the complex issues of race, colonialism, and class that permeate food systems, food systems education which equips students to enact social change is a necessary leverage point for food systems transformation (Niewolny and D’Adamo-Damery, 2016). However, scholars have warned that conventional post-secondary food systems education, with its focus on technical rather than socio-political dimensions of food production and distribution, is ill-equipped to tackle the systemic drivers of food systems issues (Meek and Tarlau, 2016; Niewolny and D’Adamo-Damery, 2016). Criticism of conventional food systems education points to its tendency to “engage learners as individuals, focusing on proximate (rather than deep system) analysis of political problems” and its emphasis on developing students’ skills as consumers (Anderson et al., 2019, p. 3). As such, conventional food systems education reflects a narrative centered on a presumption of consumer lifestyle choice as the key to addressing food systems issues (Guthman, 2011; Meek and Tarlau, 2016). This reformist and depoliticized approach to understanding food systems issues disregards, and often reinforces, structural racism and other oppressive power structures that fundamentally underlie the way that food is produced, distributed, and consumed (Guthman, 2011). Education that advocates for and mobilizes meaningful food systems transformation must therefore be predicated upon a critical engagement with interconnected power structures.

1.1. Transformative education as a leverage point for food systems change

Transformative education seeks to uncover and disrupt students’ perspectives and mindsets, by providing them with the knowledge and agency to challenge power structures and ultimately act toward societal transformation (Mezirow, 2011; Simsek, 2012; Aboytes and Barth, 2020). In the context of food systems education, transformative learning supports students’ critical engagement with the power relations, values and social norms that underpin our food system (Anderson et al., 2018; Ojala, 2022). Ojala (2022) posits that learning for food systems transformation must also involve students in their own community, to ground learning in observable actions, practices, and power relations. Critical service-learning is one approach to this: theorized as a powerful tool for mobilizing students to act toward food justice, critical service-learning engages students in a dynamic process of critical reflection and intentional community action such that they can become aware of, and act toward transforming, systemic inequalities in their society (Mitchell, 2008; House, 2014). Fundamental to this transformative food systems learning is challenging students to engage in critical thinking about the systemic drivers of the community issues they are engaging in – before, throughout, and after participating in community food projects (House, 2014).

1.2. Critical food systems education

Critical Food Systems Education (CFSE), a pedagogical framework developed by Meek and Tarlau (2016), formalizes theories of transformative and critical learning to propose a radical alternative to conventional food systems education. CFSE roots itself in Freire’s theories of popular education and critical pedagogy: education which encourages students to develop “critical consciousness” by examining and challenging social norms and power structures in their society (Freire, 1970). More specifically, CFSE seeks to provide students with the knowledge and tools to recognize, critique, and ultimately transform institutional structures driving complex social, economic, and ecological issues within food systems (Tarlau, 2014; Meek and Tarlau, 2016). Meek and Tarlau’s (2016) CFSE framework integrates three expected learning outcomes for CFSE learners:

• Agroecology: Awareness of ecological design as an alternative to industrial agriculture, and the socioeconomic and political implications of an agroecological transition (Meek and Tarlau, 2016; Dale, 2021).

• Food Justice: Awareness of race- and class-based issues within food systems and the systems of power and oppression driving these issues (Meek and Tarlau, 2016).

• Food Sovereignty: Awareness of and integration with global movements for food sovereignty, communities’ right to access, grow, and define healthy and culturally appropriate foods (Meek and Tarlau, 2016; Sampson et al., 2021).

Though Meek and Tarlau (2016) emphasize that CFSE can be advanced “at diverse educational levels and across international contexts” (p. 241), the framework centers on learning in broad social movements and in higher education. Given the neoliberal forces which profoundly shape post-secondary institutions, Classens et al. (2021a), observe that CFSE in higher education may struggle to radically oppose the dominant neoliberal paradigm that has shaped food systems. One approach to advancing such counter-narratives in the face of these constraints, argue Classens et al. (2021b), is through Campus Food System Alternatives (CFSA). CFSA are informal student-run campus food projects that offer important pedagogical spaces where counter-narratives and education for food systems transformation can emerge simultaneously, by involving students in their local food system (Valley et al., 2018). These student-run food initiatives have been posited as spaces which can prefigure alternatives to conventional food systems by exposing students to grassroots action for food systems change in-practice (Classens et al., 2021b). Engagement in such prefigured alternatives can advance students’ hope and willingness to act for transformation for a more just and sustainable food system (Anderson et al., 2018; Dale, 2021; Ojala, 2022).

CFSA are however not inherently radical nor critical. These student-run initiatives have drawn criticism on their potential for advancing depoliticized and shallow education about food systems, which can reproduce oppressive systems of white supremacy, colonialism, and classism if not actively resisted (Gray et al., 2012; Aftandilian and Dart, 2013; Green, 2021; Classens et al., 2021b). Scholars have also suggested that student-run food initiatives must seek to have a broad impact in the food system to advance learning among student participants that is truly complex, critical, and transformative (Barlett, 2011; Aftandilian and Dart, 2013).

CFSA encompass a large diversity of student-run approaches to engagement in their campus food system, including campus gardens, student-run cafés, initiatives which distribute food to food insecure students, and more (Classens et al., 2021b). While literature on CFSA recognizes their potential for transformative and critical learning, research has yet to analyze the diversity of different approaches to CFSA and how learning experiences about food systems can vary in these spaces as a result. Simultaneously, literature focused on CFSE, while clearly outlining expected learning outcomes related to agroecology, food justice, and food sovereignty, has lacked in-depth examination into the complexity of how food systems learning happens to advance these outcomes. Understanding how learning unfolds across a range of campus food system initiatives may offer important insights into their transformative potential, and the factors that enable or constrain this potential.

This study seeks to bridge these gaps in our understandings of the contributions of CFSA to CFSE by exploring how diverse approaches to student-run CFSA advance different learning dynamics for student participants and, therefore, varying degrees of critical understanding of and willingness to act for food systems transformation. We aim to offer insights on how CFSA activities and objectives can be approached such that they advance meaningful, holistic, and critical learning about food systems among student participants – who will then be equipped to become change-makers in food systems broadly.

Building on the theory and identified gaps in the literature on food systems education that we have presented, our research was guided by the following research questions:

• How does learning about food systems unfold for students participating in Campus Food Systems Alternatives on university campuses?

• What factors and activities in Campus Food Systems Alternatives allow participating students to gain an understanding of food systems that is transformative and reflective of Critical Food Systems Education?

2. Materials and methods

To understand and compare learning experiences about food systems in Campus Food Systems Alternatives (CFSA), we performed a multiple-case study analysis of four student-run CFSA at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. McGill University is a large public university based on two campuses: the main campus located in Montreal’s downtown, and the agricultural Macdonald campus, a smaller, suburban campus (approximately 35 km from the downtown campus) which houses the Faculty of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences.

Multiple-case studies allow researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular phenomenon relevant and observable in each case (here, university students’ learning experiences about food systems), while offering a more comprehensive and extensive picture of the phenomenon than single case studies and allowing for cross-case analysis (Stake, 2006; Hunziker and Blankenagel, 2021). In this study, cross-case analysis was used to understand how different learning opportunities within CFSA advance different degrees and manifestations of food systems learning which is critical and transformative.

2.1. Data collection methods

2.1.1. Mapping and recruiting CFSA

Prior to recruitment of CFSA for inclusion in this study, we created a database of the 16 identified student-run CFSA operating at one or both McGill University campuses. CFSA were categorized based on publicly available descriptions of their missions and objectives, obtained via initiatives’ websites and social media pages. Three categories of CFSA missions were identified when comparing activities across CFSA at McGill University: food production initiatives (e.g., campus gardens, campus farms); food distribution initiatives (e.g., campus food markets, student-run cafés); food waste diversion initiatives (e.g., composting). Some CFSA fell into more than one category, and CFSA activities extended beyond the campus to engage with members of the wider community.

To capture the diversity in CFSA’s missions and activities at McGill University, and thus the diversity in learning experiences that different CFSA afford to student participants, we approached two CFSA from each category to participate in the study. We selected which CFSA to approach based on our assessment of their activity status (at the time of research, many CFSA remained inactive after COVID-19 restrictions were lifted) and with a view to including CFSA across both campuses. Four of six contacted CFSA agreed to take part in the study (Table 1). Two initiatives we contacted declined to take part due to capacity constraints following the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions.

2.1.2. Documenting learning and CFSA practice

Multiple qualitative data collection methods were used to investigate how learning happens in CFSA to advance critical perspectives on food systems. We undertook document analysis of each CFSA’s website and social media profile, publicly available promotional materials, and student participant recruitment documents; site visits to CFSA activities during which we took observational field notes; and hour-long semi-structured interviews with participants from each CFSA (n = 8). Document analysis and observational field notes from site visits provided contextual qualitative data on each CFSA’s general activities. Semi-structured interviews with facilitators were used to deepen insights on each CFSA’s general missions and activities and on student participants’ personal learning experiences in their respective CFSA.1,2

2.2. Data analysis

Qualitative data from CFSA documents and observational field notes from site visits were collected, compiled, and analyzed to gain a holistic understanding of the educational activities and opportunities available for students participating in each CFSA. Thematic analysis using methods described by Braun and Clarke (2006) was performed for semi-structured interviews using deductive and inductive coding cycles, first to identify evidence of learning in line with CFSE learning outcomes (Meek and Tarlau, 2016), and related learning theories, and then to identify emergent themes related to students’ learning experiences about food and food systems.

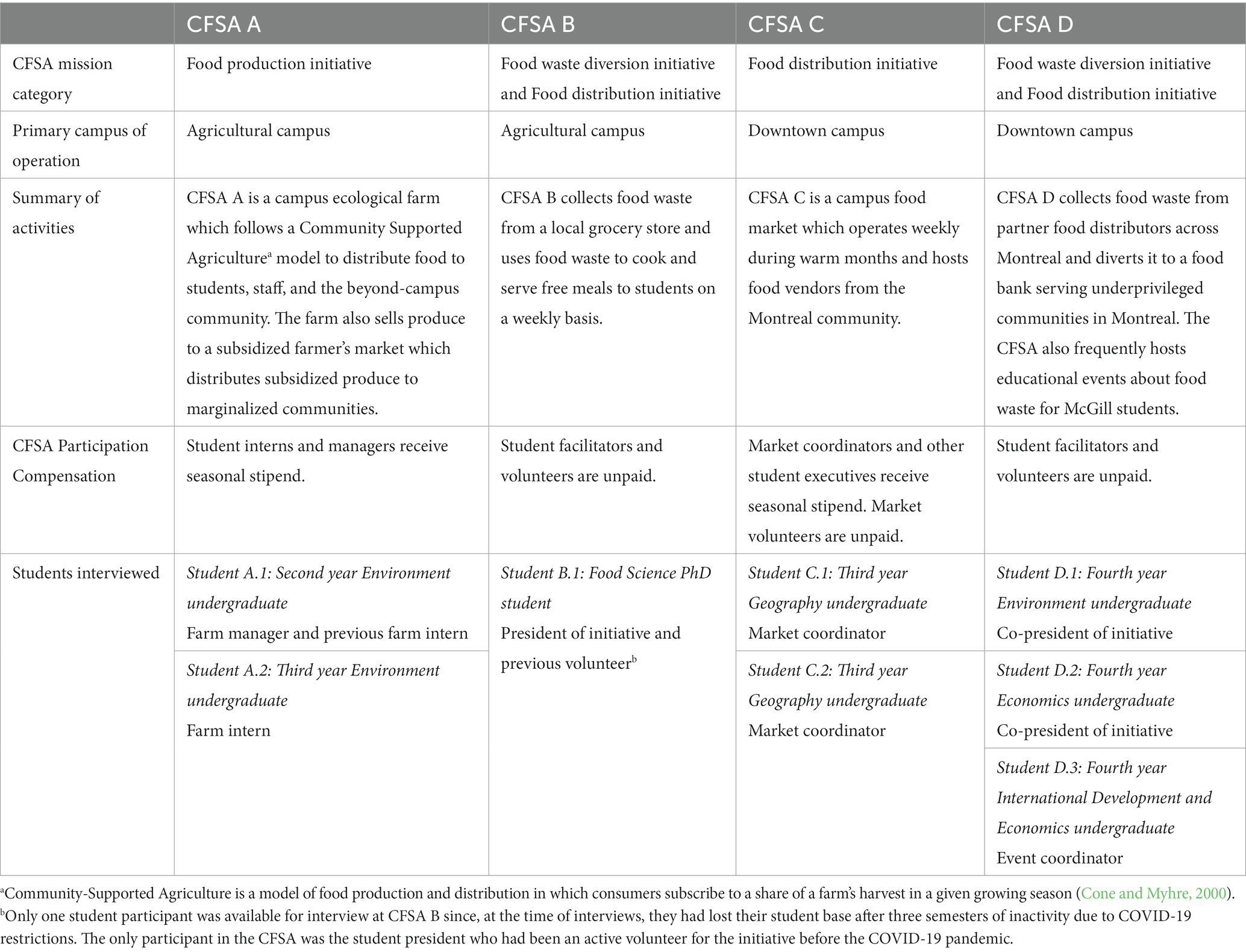

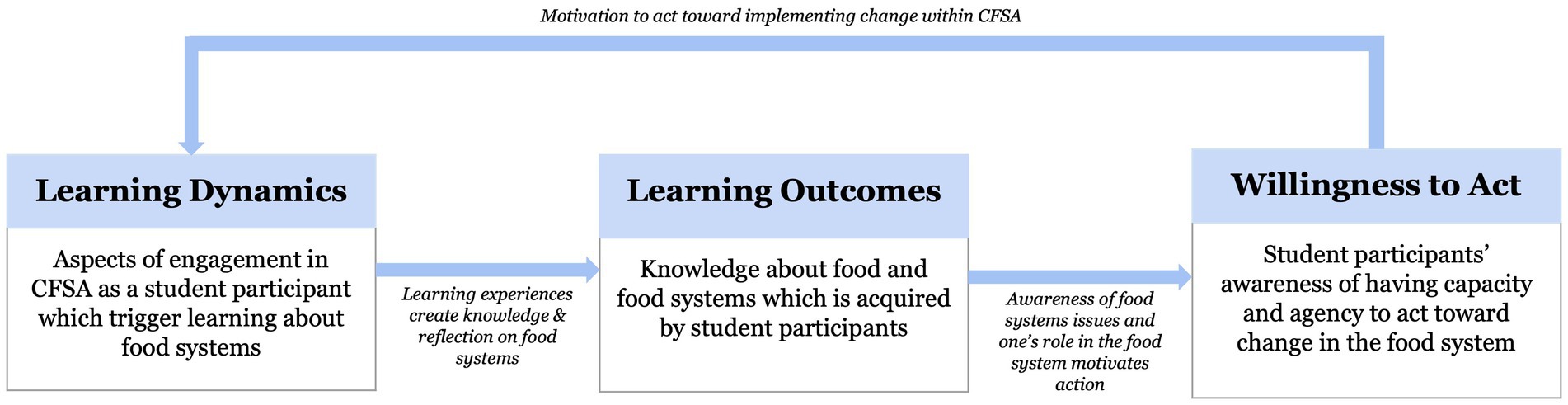

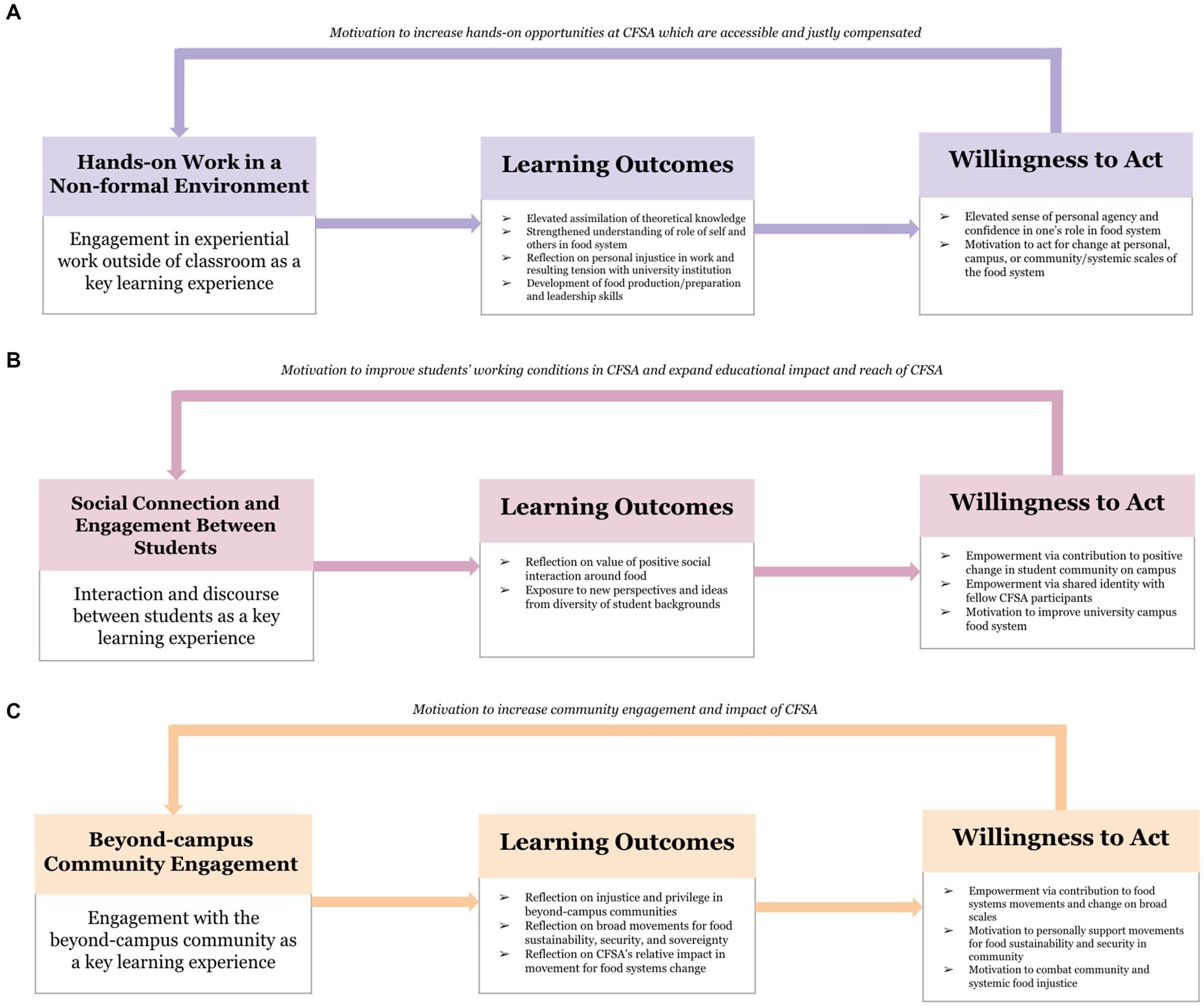

Themes from across each of the four cases were compiled and compared to perform cross-case synthesis as described by Stake (2006). We searched for differences and similarities in themes across cases to identify trends in learning experiences about food systems across CFSA. General trends in learning experiences informed our model on the dimensions of learning experiences about food systems within CFSA (Figure 1), which then informed our categorization and interpretation of themes identified in our initial thematic analysis of interviews at the individual-case level. Comparison of theme categories across cases informed our subsequent learning experience models on three identified categories of learning dynamics within CFSA (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Models (A-C) of learning experiences about food systems for three identified learning dynamics in CFSA.

3. Results

3.1. Conceptualizing learning experiences about food systems via participation in a CFSA

Our first research question asked how learning about food systems takes place for students who are participating in CFSA. To better understand the learning processes that unfolded, we structured student participants’ learning about food systems in their respective CFSA into three interconnected dimensions of a holistic learning process: learning dynamics, learning outcomes, and willingness to act toward food systems change on multiple levels (Figure 1).

While students entered CFSA with varying levels of prior theoretical knowledge about food systems (see Table 1 for students’ educational backgrounds), students’ learning experiences within CFSA began with learning dynamics, which we define as engagement in CFSA activities which provide opportunities for knowledge acquisition and/or reflection on food systems. We term the resulting knowledge or awareness gained about food, food systems, and one’s role in the food system as learning outcomes. Learning outcomes were observed to often (though not always) motivate a willingness to act for change in the food system. We define this dimension as students’ awareness of their capacity and agency to act toward change within the food system, manifested as feelings of empowerment or personal motivation to enact change (at levels of personal change to campus-based change to beyond-campus community and systemic change). Willingness to act was occasionally observed to manifest as a desire to change the actions, activities, and/or missions of the CFSA one participates in, which can, in turn, lead to changes within the learning dynamics experienced by other student participants in the CFSA, as represented in Figure 1. These dimensions of learning experiences about food systems in CFSA informed our categorization and interpretation of themes that emerged both within and across cases, as we will explore below.

3.2. Learning experiences within individual cases

Since document analysis, field visits, and interviews revealed a wide range in the learning activities that CFSA allow students to participate in, learning dynamics (defined above) unsurprisingly also varied across cases. Drawing on student interviews, the following results outline the CFSA’s missions and student participants’ learning experiences, divided according to their associated learning dynamic. We have identified and described the learning outcomes and manifestations of willingness to act associated with each learning dynamic, to capture the holistic learning experiences of CFSA participants in each case.

3.2.1. Case a: student-run ecological farm

CFSA A’s mission is to produce food with regenerative practices while simultaneously teaching students the skills required to manage a small-scale ecological farm. A primary goal of the CFSA is to become economically self-sufficient; the farm currently operates as a business, with revenue generated from CSA basket sales to members of the student and beyond-campus community. Participants described CFSA A as an experimental farm centered on learning, where hired students can translate theoretical agricultural knowledge gained in the classroom to hands-on ecological farm work and management experience.

3.2.1.1. Experience and observation of injustice within the CFSA

A key dimension of the learning that emerged from interviews were student participants’ own experience of financial injustice within the CFSA, in which students felt unjustly compensated for their work as small-scale farmers. This led to critical reflection on the CFSA’s financial and social sustainability (and the connection between the two) and a resulting sense of responsibility to improve the farm’s compensation model such that it is more accessible and just for underprivileged students. Both students also reflected on how financial injustice within the CFSA appeared to be a result of tensions between the farm’s focus on regenerative practice versus the university’s profit-driven interests:

I would say that we [CFSA A] care a little bit more about sustainability and regenerative ways to grow food than McGill does. […] We’re not really a priority for them [McGill] at all. I know a lot of student farms at other universities have agreements with the cafeterias, so they can kind of get more permanent funding because they're strictly integrated into the school's food systems. Opportunities like that are something that McGill has really lacked. (Student A.2).

This reflection on financial injustice was also extended to the wider beyond-campus food system and the similar injustices faced by small-scale agricultural workers:

We're still trying to find a ways to make [CFSA A] more financially sustainable, which will really help in terms of social sustainability, because at the moment it's mostly causing exhausted team members who don’t necessarily feel compensated for their hard work and not being able to seek any other form of employment because farm work will suck out all your time and energy [...] This seems to be something that keeps being repeated from farm to farm, especially the small-scale farmers that I know… it's always the same issue. (Student A.1).3

3.2.1.2. Engagement with the beyond-campus community

Student participants engaged with beyond-campus communities through weekly interaction with farm share basket members and produce distribution to a local food security initiative which subsidizes produce for marginalized individuals in the community. Engaging with these communities led to critical reflection on food inaccessibility and injustice in marginalized communities. Students described feeling empowered by the awareness of contributing tangibly to community food justice, and a resulting motivation to increase the financial accessibility of the CFSA’s food and support movements for beyond-campus food justice, beyond the context of the CFSA. Student participants also felt that their engagement with the beyond-campus community shattered conventional producer-consumer barriers, allowing for a more holistic understanding of the food system.

3.2.1.3. Hands-on engagement in the food system

Student participants gained hands-on experience in food production through the CFSA, including field work, produce distribution, and administrative tasks. Students felt that this enriched the theoretical knowledge they gained prior to their CFSA work. One student also reflected critically on how hands-on engagement in farm work radically contrasted the formal food systems education they had received:

A lot of what I thought I knew about sustainable food systems was flipped on its side when I started working on the farm. [...]. I feel like there is this weird, estranged capitalist idea of what sustainability looks like, in order to sell things to people by making them look sustainable. I have learned the reason that exists is a symptom of the fact that no one is engaged with their own food systems, and so the idea of what sustainability really looks like is off. (Student A.2).

Participants described gaining a sense of confidence and empowerment from developing tangible food production and leadership skills. Their appreciation for hands-on work also motivated thinking about how to increase field work opportunities to more students on campus.

3.2.1.4. Transition to leadership roles

Hired students commit to two growing seasons of work, starting in the first season as farm intern, an apprentice-like role in which students are taught farming and leadership skills by managers, and progressing to a manager role in the second season. This transitional structure allowed students to develop practical leadership skills and assimilate and apply the knowledge gained as interns. This transition created feelings of independence, responsibility, and agency in student participants, resulting in a simultaneous sense of empowerment and confidence, and a motivation to take a leadership role in advancing food security beyond campus:

After [CFSA A], I do see myself working more towards working for food security organizations, or working at the center of a community [...] Yeah, to just empower people with knowledge. I find that something that I am really looking forward to explore more after [CFSA A]. (Student A.1).

3.2.1.5. Discussion and engagement with fellow students

Interactions between farm interns and managers were described as joyful, empowering, and crucial to the CFSA learning experience. One farm manager described deriving a strong sense of empowerment and pride from witnessing the personal growth of farm interns and from feeling like part of a long-lasting legacy of students in the CFSA:

I feel like I’m getting ready to see them [the farm interns] taking their first flight and it’s so exciting. I get so emotional just thinking about it, because I’m so proud of the work that they have put in. They’ve soaked up so much information and they did it with so much joy. […]. It fills me with pride of what we have done and what they will keep on doing and kind of like, keep moving in the future with that legacy that I was a brief part of in the grand scheme of things. (Student A.1).

3.2.2. Case B: food waste diversion initiative

CFSA B’s primary mission is to bring students joy and community through tasty, free food. By preparing free meals for the student community on a weekly basis, CFSA B also seeks to raise awareness about food waste by showing students that expired or near-expiry foods can be used to prepare appealing dishes. The CFSA also seeks to teach its student volunteers cooking and creativity skills.

3.2.2.1. Discussion and engagement with fellow students

CFSA participants interacted with fellow participants, and with the wider student community via serving free prepared meals on a weekly basis. These social connections were described as particularly joyful on meal service days when participants witnessed fellow students’ enjoyment of free food. This encouraged reflection on food as a conduit of joy and community-building, which resulted in a sense of empowerment and inspiration:

I would say the most empowering and happiest moments are seeing people enjoy the food we cook. That's the motivation behind me continuing being a president of [CFSA B] [...] I always find that it’s inspiring, and our goal is achieved when we see people running for our food, because they know that we are serving food not only because it's free. It's for a purpose: to reduce food waste and to raise awareness of food waste. (Student B.1).

3.2.2.2. Exposure to volume of food waste in beyond-campus community

Student participants witnessed firsthand the volume of food waste delivered by the partner grocery store, which was described to be surprising and upsetting, and encouraged reflection on the unsustainability of conventional food quality standards that drive food waste:

In moments where I see the amount of food that is sent to us, I think about how it could basically just go into the trash instead of being eaten. That triggers me. It's so much. And this is only from one grocery store – could you imagine the amount of grocery stores around just Montreal itself? (Student B.1).

The student participant also reflected on the injustice and privilege involved in food waste in contrast to local food insecurity, which motivated the student to make personal changes to reduce their food waste as a consumer.

3.2.2.3. Hands-on engagement in food system

Hands-on cooking experience in CFSA B encouraged the participant to develop personal cooking and creativity skills and reflect on the value of experiential learning opportunities which contrast with formal classroom education. With these skills, the participant described feeling more comfortable to cook more to reduce their individual food waste. In coordinating the CFSA, the student participant also witnessed tensions between their student-run initiative and the conventional modes of food production and distribution on campus that the university supports financially. Particularly, the student described challenges with coordinating food preparation and service times with the university cafeteria that they shared space with.

3.2.3. CFSA C: student-run food market

CFSA C provides university students access to local and healthy food on campus, at affordable prices. The CFSA aims to empower sustainable local vendors and small businesses by connecting them to a market of buyers on-campus. In turn, the CFSA also seeks to connect students directly with food producers, to allow students to develop a closer relationship with and understanding of their local food system.

3.2.3.1. Engagement with the beyond-campus community

Student participants interacted closely and regularly with food vendors and urban agriculture initiatives from the beyond-campus community, leading to exposure to diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts. This occasionally resulted in reflection on food-related injustice experienced by vendors on local and global levels:

[Interacting with one of our vendors from a marginalized background] made me think of how modern-day coffee picking is a relic of traditional, slave-based economic systems and colonialism. And how Quebec and Montreal can be a place that can start to pay reparations [by supporting marginalized food vendors]. (Student C.1).

Students felt inspired and empowered by contributing to tangible food systems change and supporting local sustainable food vendors, resulting in a desire to continue supporting local food systems with their buying power.

3.2.3.2. Discourse and engagement with fellow students

CFSA participants engage and connect socially with other student executives, volunteers, and visitors to the market, prompting reflection on the value of local food in community building and social connection. This leads to a sense of inspiration and empowerment from sharing similar ideas, passions, and priorities with fellow students. Social connection with fellow participants also created a sense of responsibility to ensure that all participants are compensated fairly for their work and dedication to the market.

3.2.3.3. Hands-on engagement in the local food system

Hands-on engagement in coordinating the market and distributing food on campus developed students’ leadership skills and allowed students to feel that they were creating a fulfilling, tangible relationship with the local food system:

It is such a different relationship with fresh food [versus processed food]. For the same price, you can get something that's so much more valuable in terms of sustaining local economic systems and not having industrial farming be a part of how you're feeding yourself [...] Like you’re so much more connected to the food you're eating and what you're putting in your body. (Student B.1).

Students’ engagement with the local food system was described as developing their motivation to further support local food systems in their consumer choices outside of the CFSA.

3.2.4. CFSA D: food waste diversion initiative

CFSA D’s mission is to collect food waste from food distributors in the local food system and simultaneously combat local food insecurity by diverting waste to underprivileged communities. The CFSA also seeks to raise awareness about food waste in the student community through a diversity of educational events about food sustainability.

3.2.4.1. Engagement with food insecurity in the beyond-campus community

Through deliveries of food waste to a local community food bank, student participants engaged with marginalized food-insecure communities beyond campus, prompting participants to confront their relative position of economic privilege as university students. Food bank experiences also encouraged students to consider the origins of food insecurity:

I would see exactly who I was delivering the baskets to and people were always so thankful. And for a moment, it was like,’ Oh, wow, I'm really doing something’. Then the second thought was like, ‘Wow, why? How is it that one basket of food is making this person's day?’ Like, this is such an easy thing to implement that this should be guaranteed. (Student D.1).

Students also expressed deriving a sense of accomplishment, empowerment, and motivation from contributing tangibly to increasing marginalized communities’ food security:

Seeing the expressions of the [food bank] workers and the people who are waiting be served – it just feels good that we're making a difference in those people's lives. Seeing the actual people that we're going to be supporting through our food is very personally rewarding and motivating because it makes us want to work even harder. (Student D.2).

One participant noted that the educational impact of the CFSA is limited for participants not involved in food deliveries who do not witness community realities beyond campus. This led to the participant’s motivation to involve more students in food deliveries.

3.2.4.2. Exposure to volume of food waste in beyond-campus community

By collecting food waste from partner organizations, participants witnessed the volume of food discarded by food distributors. A sense of empowerment and accomplishment was derived from witnessing the amount of food waste collected and diverted by the CFSA, and students described a resulting motivation to increase the CFSA’s food diversion and reduce their personal food waste. Exposure to food waste also prompted reflection on the need for systemic change to address food waste, given the limitations of consumer choice-driven efforts to reduce food waste and of the CFSA’s impact on a broad scale.

3.2.4.3. Discourse and engagement with fellow students

CFSA participants engaged and connected socially with other student volunteers, executives, and participants in the CFSA, leading to new perspectives and critical reflection on food systems issues. One participant recalled meaningful discussions with fellow participants on how to maximize the CFSA’s beyond-campus community impact, which encouraged reflection on how to support meaningful food systems change broadly. Social connection with like-minded students was also reflected on as a joyful, inspirational, and hopeful experience which made addressing food waste feel less overwhelming:

I think it's easy to get caught up in thinking ‘Oh, well, I can't make a difference. What's the point of even trying?’ [...] What I have realized is that you shouldn't try to give up; just try to connect with other people who are feeling the same way and [...] get yourself involved in something bigger so you don't feel like you're fighting alone. (Student D.1).

3.3. Cross-case analysis of learning experiences in CFSA

Returning to our guiding research questions on how learning happens in CFSA and the factors that enable transformative and critical learning, we analyzed and synthesized students’ described learning experiences across cases. Comparison of student participants’ learning experiences, and their associated learning dynamics, learning outcomes, and manifestations of willingness to act revealed similarities and differences in respective CFSA’s advancement of critical and transformative food systems learning. More specifically, students’ reported learning in Cases A and D aligned more significantly with the expected learning outcomes of CFSE than those of participants in Cases B and C. In both CFSA A and D, students reflected on social and economic issues within the food system as complex issues of injustice, a key dimension of the CFSE framework (Meek and Tarlau, 2016). These reflections appeared to be enabled by experiencing injustice in the food system – either personally (e.g., unjust compensation) or indirectly (e.g., engaging with marginalized and food insecure communities). In experiencing or witnessing injustice, participants in these CFSA also reflected on their personal role and the role of the CFSA in enacting change for food security and justice on community and systemic levels. Intentional critical reflective practice was however not observed to follow experiences of injustice in either CFSA.

Students’ learning experiences in CFSA B and C were less reflective of the critical learning outcomes and willingness to enact transformative change expected in CFSE. In CFSA C, participants’ reflections on food systems were largely focused on local food vendors and their mission of providing students the opportunity to purchase local, healthy food from the market. This resulted in a willingness to act for change centered largely on consumer responsibility to support local food systems. Interactions with vendors from marginalized backgrounds did however create opportunities for students to reflect on systemic food injustice in CFSA C. In CFSA B, the participant, through witnessing the partner grocery store’s food waste and students’ enjoyment of their food, gained an understanding of food systems centered on personal consumer change to reduce food waste. Both of these CFSA’s missions centered on shifting students’ consumption patterns through food service; participants simultaneously emerged with a perception of consumer behavior as a key to addressing food issues.

Cross-case analysis and synthesis of within-case themes capturing learning dynamics also revealed that learning dynamics identified across CFSA could be grouped into three broad categories:

• Beyond-campus community engagement

• Hands-on learning in an informal environment

• Social connection and engagement between students

Similarly, cross-case comparison of themes related to student participants’ learning outcomes and willingness to act revealed that these three categories of learning dynamics generated similar associated learning outcomes and willingness to act, which can be compiled and modeled as flowcharts (Figure 2) following the model from Figure 1. Depending on the respective missions and learning activities offered by CFSA, the extent to which the three categories of learning dynamics were observed in cases varied. It should be noted that while students across CFSA expressed willingness to act toward food systems change at various levels (including a motivation to change CFSA’s compensation models in cases A and C), we did not see evidence of students translating these motivations into concrete action taken to change the systemic conditions they were working under. We suggest a need for a longitudinal study of students’ learning experiences to assess if and how a willingness to act for change is translated into change within and beyond the CFSA (see Limitations).

4. Discussion and recommendations

Given the diversity in learning dynamics afforded by CFSA across cases, we attribute the varying extent to which CFSE was reflected in learning experiences to differences in learning dynamics enabled within CFSA. The three identified learning dynamic categories appeared to be particularly relevant and important here. We will therefore explore dimensions of these three categories of learning dynamics and how they advance different manifestations of critical and non-critical food systems learning, in the context of our findings and literature on environmental and food systems education and related pedagogical theories.

4.1. Hands-on learning in an informal environment

Hands-on engagement in food-systems-related work, outside of the formal classroom environment, was a key learning dynamic identified in all four CFSA. First, these experiences allowed for elevated assimilation and reinforcement of theoretical knowledge that students had previously gained about food systems, in the classroom or elsewhere. As reflected by study participants, the application of theoretical knowledge to hands-on work has been found to be a rewarding and motivating factor in experiential food systems learning in higher education (Ahmed et al., 2018). Our findings also support that hands-on work beyond classroom confines provides many students their first opportunity to engage closely with their local environment, community, and food system. These beyond-classroom opportunities can challenge or expand students’ previous conceptions of food systems gained in classrooms or mainstream media (Gramatakos and Lavau, 2019).

Close hands-on engagement with the campus (and beyond-campus) food system also allowed participants to gain a multi-dimensional understanding of the role that people (including oneself) play within the food system:

Learning like that [hands-on] is so much more multisided [than classroom learning]. Like, you learn about yourself, through learning about the world and interacting with the world. I feel like in my school life, I'm like, “I'm going to go to class and learn about the world”. Then, “I'm going to go home and learn about myself.” And I feel like the farm was a really great place to do both. (Student A.2).

Interacting closely with their environment and community via hands-on field work allowed participants to make sense of themselves and their surroundings in the context of working within a food system; this outcome of hands-on and informal learning has been identified as a key step in youth’s development of critical consciousness of environmental and food systems issues, by giving them the opportunity to understand themselves as agents of transformative change within the food system (Delia and Krasny, 2018; Gramatakos and Lavau, 2019; McKim et al., 2019).

Hands-on work outside of the classroom also led students to personally experience the realities of injustice that result from working within the larger conventional food system, particularly in the context of working as a producer of alternative, ecological food (Case A). These personal experiences of injustice were especially important in driving students’ critical reflection on the social, economic, and ecological dimensions of food injustice more broadly. By engaging hands-on simultaneously within the university’s confines and in informal campus spaces, hands-on work was also observed to allow for students to witness, experience, and reflect on tensions between the CFSA’s interests and actions and those of the university as a neoliberal institution which tends to oppose structural and radical change (Levkoe et al., 2019; Michel et al., 2020). Witnessing such tensions encouraged students to reflect on challenging institutional barriers to transformative change in the university and in society broadly. This observation reflects Barlett’s (2011) assertion that campus food projects, when driving forward institutional change at the university, can be important “test sites” for students to become aware of and enact wider social change.

Finally, informal hands-on engagement in the campus food system allowed students to gain practical skills, from cooking skills to general leadership and group-work skills, a commonly observed outcome of experiential and place-based learning in environmental and food systems education (Aftandilian and Dart, 2013; Ahmed et al., 2018; Valley et al., 2018; McKim et al., 2019). Although practical skills development was not observed to be directly tied to critical reflection on food systems in itself, our findings and related literature support skills development as a key aspect of CFSA which can build students’ sense of personal achievement and self-confidence (Aftandilian and Dart, 2013; Delia and Krasny, 2018). These qualities are important in developing students’ agency to take an active role in enacting transformative change on personal, campus, community, and/or systemic levels (Aboytes and Barth, 2020). This was particularly relevant in Case A in which student participants were provided opportunities to take on leadership roles within the CFSA.

4.2. Social connection and engagement between students

As student-led environments, the CFSA in this study were consistently described as spaces which facilitate social connection between students, which was a key driver of learning experiences in CFSA. Student-led learning in informal spaces like CFSA has been found to advance social learning between peers, in which students can create a sense of shared meaning and collective identity, an important feature of transformative learning (Gramatakos and Lavau, 2019). This was mirrored in our findings, in which students reflected on the positive social connections that they had formed via participation in the CFSA. Multiple students described how inclusion in a social environment of shared identity around engagement in the campus food system created a willingness to act manifested as a strong sense of empowerment, hope, and inspiration to contribute to food systems change:

I guess it's just great to see that other [participants in the market] not only think [the market] is important, but value it enough that they would spend time that they could use, like, chilling and doing school, being paid better in another job, to make [the market] possible. Yeah, it gives me a lot of hope. (Student C.1).

This shared identity and empowerment built around pursuing common goals has been identified as crucial to driving meaningful collective action, and simultaneous collective transformative learning among student-led campus groups like CFSA (Clark, 2016; Mejiuni, 2017).

Moreover, particularly for CFSA participants in leadership roles, social connections with fellow student participants were expressed to motivate a sense of responsibility toward peers to ensure that their CFSA work was being appreciated and compensated justly; in Cases A and C, where student work was compensated with seasonal stipends, this manifested as students’ motivation to improve the financial accessibility and compensation models of their CFSA.

Discourse between students in CFSA was also identified to reveal new perspectives and ideas. Gramatakos and Lavau (2019) discuss how learning in informal student spaces brings together individuals from faculties which share little overlap, advancing opportunities for knowledge exchange between students with diverse academic perspectives. Knowledge sharing is considered an important step in building the social capital necessary to drive meaningful social change in groups, like CFSA (Blay-Palmer et al., 2016).

4.3. Engagement with the beyond-campus community

Engagement with communities beyond campus was key in developing CFSA participants’ understanding of food systems in a context broader than the university food system. This was achieved, first, when beyond-campus community engagement exposed students to complexities in Montreal’s urban food system and local movements for food sustainability, security, and justice. Awareness of these movements was observed to develop hope and inspiration within participants, and a resulting motivation to support these movements beyond the CFSA context. In giving students the opportunity to witness movements for alternative food systems and reflect on how their CFSA’s mission connects to these, beyond-campus community engagement serves as a driver of CFSE’s food sovereignty pillar (Meek and Tarlau, 2016).

Furthermore, when involving exposure to and involvement with community food injustice and insecurity (i.e., Cases A and D), engagement with the beyond-campus community encouraged complex, holistic, and critical reflection on food justice. In their reflection on beyond-campus community injustice, as well as injustice within the CFSA, students made explicit connections between intersecting social, economic, and ecological systems. Recognition of complex interactions between social, economic, political, cultural, and ecological systems has been identified as a signifier of transformative learning and critical pedagogy for environmental and food systems education (Delia and Krasny, 2018; Aboytes and Barth, 2020). As such, when community engaged, CFSA can advance transformative opportunities for students to witness the complex interplays between these systems on local, tangible scales (McKim et al., 2019; Classens et al., 2021b). This was observed to contribute to CFSA participants’ sense of responsibility and agency to act toward community food justice. Theories of place-based learning identify that witnessing these systemic interactions on concrete, local scales, in which they are no longer perceived as abstract and decontextualized, allows systemic issues to be more tangible and less overwhelming for students (McKim et al., 2019). Michel et al. (2020) also compare students’ engagement with injustice in marginalized communities as triggering disorienting dilemmas – important moments in Mezirow’s (2000) theory of transformative learning in which new information activates students’ critical questioning of past beliefs, perceptions, and expectations – which leads students to reflect on the systems driving community food injustice and creates motivation to act for change (Aftandilian and Dart, 2013; Michel et al., 2020).

Finally, beyond-campus community engagement was observed to encourage students’ reflections on their positionality and privilege in the broader food system beyond campus. Participants in CFSA reflected on McGill University as a largely privileged environment where students are often alienated from community realities:

I think it’s important, especially at McGill, which is a pretty wealthy university that is really well-resourced, you can get really isolated from Montreal and Quebec as a place that you’re living in. And it just becomes kind of like the place you’re going to school. I think food is a big part of changing our generation’s understanding of and relationship with local food systems. (Student C.1).

CFSA can thus allow students from privileged backgrounds to “witness power, authority, privilege and oppression in the food system play out in the daily lives of others,” a key point in critical food systems learning (Valley et al., 2018, p. 12) Engagement with community realities via service learning has indeed been observed to allow students to realize their relative privilege in contrast to marginalized communities (Kiely, 2005; Gray et al., 2012; Aftandilian and Dart, 2013), an important driver of transformative learning (Kiely, 2005; Green, 2021).

4.4. Recommendations

The findings above describe the importance of hands-on engagement and social connection between students in learning experiences across all CFSA. However, these dynamics appeared to be less significantly tied to critical reflection on food systems issues than beyond-campus community engagement. This may be because neither hands-on engagement nor social connection between students necessarily involves exposure to, and thus, reflection on, food injustice and the systems that underpin it. CFSA work that is not rooted in challenging structural inequalities in the food system thus appears limited to advancing the shallow learning outcomes of conventional food systems education that scholars like Guthman (2011) warn against. Especially in the context of a largely privileged student body at a university conforming to an increasingly neoliberal model of higher education, beyond-campus community engagement appears necessary for students to witness and learn critically about complex issues of race, class, and colonialism within food systems.

In comparing learning dynamics afforded by CFSA, it is interesting to consider how CFSA engage the “politics of the possible” – one’s vision for political, economic, and social change – discussed in the context of CFSE and food systems transformation by Meek and Tarlau (2016). Different levels of engagement in the food system create different manifestations of politics of the possible within students (Blay-Palmer et al., 2016; Meek and Tarlau, 2016). When students are given opportunities by CFSA to contribute to addressing systemic issues on a community-wide level, their perception of what type of food systems change is possible expands beyond levels of personal change or campus-based change. Rather, students come to perceive broader change as possible, enabling the development of students’ motivation to enact the radical food systems transformation that CFSE advocates for. We therefore recommend that CFSA work is embedded in community justice work and a locally grounded social change objective.

It is important to recognize that a community-engaged CFSA will not necessarily advance CFSE; in line with critical service-learning theory, engagement with communities beyond campus, especially marginalized ones, must be approached carefully and intentionally to avoid extractive relationships which solidify oppressive power dynamics between marginalized and privileged communities (Mitchell, 2008; Gray et al., 2012; Andrée et al., 2016; McKim et al., 2019). Intentional background work is necessary for incoming participants to experiential community-based learning; students must be “provided with orientations to sensitize them to the issues of power, privilege, and respectful engagement before they enter into community settings” (Gray et al., 2012). Moreover, community partnerships must be collaborative by involving reciprocal and mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources (Andrée et al., 2016). Andrée et al. (2016) call for a “horizontal” approach to community-university partnerships for transformative food systems change, centered on building “just, healthy, and vibrant communities” (p. 144) by breaking down hierarchical power relationships.

CFSA must also integrate opportunities for student participants to engage in intentional critical reflection on their observations and experiences within the beyond-campus community. This intentional reflective practice was not directly described by students in any of the four cases. When asked to discuss if they have had meaningful learning experiences about food systems by engaging with their peers, one CFSA participant said:

I think we're just excited about being surrounded by fresh veg every week. At least I know, it's kind of nice to just be in the atmosphere [of the market]. But I don't know if we ever talked that much about our personal experiences with like, food and accessibility (Student C.2).

Critical and intentional reflection has been established as a necessary aspect of critical pedagogy and transformative learning. Freire’s theory of action-reflection posits that “if action is emphasized exclusively, to the detriment of reflection, [...] [it] negates the true praxis and makes dialog impossible” (Freire, 1970, p. 88). Other scholars have also highlighted the importance of dialog and critical reflection for ensuring that students’ observations of environmental and food-related injustice are contextualized in wider socioeconomic circumstances (Mezirow, 2011; Gray et al., 2012; Galt et al., 2013; House, 2014; Meek and Tarlau, 2016; Anderson et al., 2018). Given that we found CFSA to facilitate strong social connections and opportunities for dialog, we suggest that there is significant potential for integration of critical reflective practice between peers in CFSA.

Considering how these recommendations can be integrated into CFSA on university campuses brings to light numerous questions. First, do CFSA have a responsibility to contribute to community movements for food justice, and what is the educational value of CFSA that lack community engagement? Students expressed positive feelings derived from bringing joy to other students through CFSA action on campus, even when these actions were depoliticized and transactional. Barlett (2011) describes how campus food projects that are not explicitly radical or critical can still provide valuable opportunities for students to witness alternatives to the conventional food paradigm: “[A]lthough often phrased in positive, nonpolitical terms with examples of progress toward campus goals, [campus food projects] legitimize a degree of distrust for governmental, corporate, and academic reassurances about the conventional system” (p. 111). While not explicitly creating radical change-makers, these initiatives do still encourage students to build a closer relationship to food and food systems, which can lead to further questioning of and engagement in the food system. Moreover, engagement with joyful and hopeful environmental and food systems activities has been described as an important counterpoint to conventional “doom-and-gloom” environmental education that can debilitate students’ motivation to act for change. Conversely, positive social experiences in environmental and food systems education can motivate students to sustain, or activate, engagement in food systems movements (Ojala, 2022).

Second, who within CFSA is responsible for advancing intentional, collaborative, and critically reflective opportunities for engagement with beyond-campus movements for food justice and food sovereignty? Gray et al. (2012) identify formal educators as the typical actors who facilitate and guide students’ students’ reflective practice on issues of race- and class-based power, privilege, and oppression in food systems, through practices such as guided discussion and journaling. Classens et al. (2021b), however, warn against formalizing learning in CFSA given that much of their pedagogical value is in their advancement of student-led and hands-on informal learning. Food sovereignty activists have similarly warned against academic involvement in their movements given the tendency to prioritize knowledge produced by the university over knowledge built collaboratively with communities (Andrée et al., 2016). Moreover, in being student-led, we observed CFSA to be important spaces where students can experience tensions with the university’s neoliberal interests, which can advance their reflection on and motivation to act toward institutional change. Formalizing CFSA thus risks undermining the radical potential of these initiatives. We recommend that researchers of food systems pedagogy explore how student leaders can become aware of critical pedagogical practice and integrate it into the structure and activities of their CFSA, without being compromised by the university institution.

5. Limitations

While this comparative case study points to opportunities for transformative learning in CFSA, our research design has limitations. This research is limited primarily by its small sample size of only four CFSA on one university campus, with 1–3 student facilitators interviewed per CFSA. Our small sample size was a result of the small size of these campus initiatives themselves. This is partly due to recruitment challenges faced by initiatives in having faced major restrictions on their activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic; at time of research, many initiatives were in their first months of activity post-pandemic. The small size of CFSA was also partly due to the temporary nature of student involvement in these initiatives given students’ academic timelines. This study implies opportunities for larger cohort and longitudinal studies to deepen our analysis of learning within CFSA.

6. Conclusion

These four case studies of university students’ learning experiences within Campus Food System Alternatives have revealed complexities in how engagement in student-run food initiatives on university campuses drives students’ learning about food systems. Analysis of students’ described experiences in CFSA revealed that learning experiences about food systems followed an interconnected model of learning dynamics, learning outcomes, and willingness to act for change in the food system (Figure 1). This model was used to generate three categories of learning dynamics, each with associated outcomes and manifestations of willingness to act (Figure 2), based on students’ learning experiences across the four CFSA. These categories of learning dynamics illuminate why and how engagement in different types of CFSA led to differences in the reflection of transformative Critical Food Systems Education in students’ CFSA experiences.

CFSA were found to be spaces which consistently provide valuable opportunities for students to engage hands-on with their local food system and simultaneously connect with peers with whom they can create a shared identity around food. The observed connection between these learning dynamics and students’ sense of confidence and agency to enact change suggest that hands-on learning and social connection in CFSA are key for laying the groundwork for creating change-makers among university students, an important objective of CFSE (Meek and Tarlau, 2016). However, for CFSA participation to be a motivator for students to enact transformative, radical, and systemic change, opportunities for witnessing and engaging with food-based injustice is necessary. The study’s findings suggest that beyond-campus community engagement, especially with marginalized communities facing food injustice, is key to driving CFSA learning experiences which are critical and transformative.

As such, we suggest that student-run food initiatives, to advance CFSE for participants, must seek to expand their activities to include support and action toward food justice in the beyond-campus community in such a way that is intentional, reciprocal, and actively subversive to oppressive power dynamics. As discussed, CFSA must also integrate opportunities for intentional critical reflective practice among students, a practice which appears to be uncommon within CFSA. Our recommendations for beyond-campus community engagement in CFSA, with the goal of advancing CFSE among university student participants, align closely with Mitchell’s (2008) framework of critical service learning, which describes learning for social transformation through collaborative and anti-oppressive community partnership.

Given limitations in our study’s small sample size of four CFSA on one university campus, future research on student-run food initiatives could investigate if similar trends in learning dynamics are observable in larger and more diverse samples of CFSA. Longitudinal research is also needed to explore how students’ willingness to act for food systems change is transformed into concrete institutional action. Moreover, our findings indicate questions on how CFSA can advance CFSE by integrating careful and critical community engagement and intentional critical reflective practice, without risking formalizing these spaces and reducing their radical potential. Further research is necessary on the complexities of how these spaces are led and coordinated by students, to find opportunities for student-driven leadership of Critical Food Systems Education.

Data availability statement

The raw de-identified data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Board Office of McGill University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZD and BH contributed to the conception and design of the study. ZD gathered data and performed qualitative analysis and synthesis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript with subsequent editing, additions, and revisions from BH. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emily Sprowls and the McGill Leadership and Learning for Sustainability Lab group at McGill University for their support throughout this project. We thank the students in the participating campus food initiatives who contributed their insights to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1230787/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Data collection was undertaken with McGill Research Ethics Board approval (certificate number: REB#22–04-114).

2. ^Our interview guide can be found in the article’s Supplementary matrial.

3. ^Quote excerpts from students’ interviews were edited minimally to remove words like “um” or “like.”

References

Aboytes, J. G., and Barth, M. (2020). Transformative learning in the field of sustainability: a systematic literature review (1999-2019). Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 21, 993–1013. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-05-2019-0168

Aftandilian, D., and Dart, L. (2013). Using garden-based service-learning to work toward food justice, better educate students, and strengthen campus-community ties. J. Commun. Engage. Scholarsh. 6, 55–69. doi: 10.54656/YTIG9065

Ahmed, S., Byker Shanks, C., Lewis, M., Leitch, A., Spencer, C., Smith, E. M., et al. (2018). Meeting the food waste challenge in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 19, 1075–1094. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-08-2017-0127

Anderson, C. R., Binimelis, R., Pimbert, M. P., and Rivera-Ferre, M. G. (2019). Introduction to the symposium on critical adult education in food movements: learning for transformation in and beyond food movements—the why, where, how and the what next? Agric. Hum. Values 36, 521–529. doi: 10.1007/s10460-019-09941-2

Anderson, C. R., Maughan, C., and Pimbert, M. P. (2018). Transformative agroecology learning in Europe: building consciousness, skills and collective capacity for food sovereignty. Agric. Hum. Values 36, 531–547. doi: 10.1007/s10460-018-9894-0

Andrée, P., Kepkiewicz, L., Levkoe, C., Brynne, A., and Kneen, C. (2016). “Learning, food, and sustainability in community-campus engagement: teaching and research partnerships that strengthen the food sovereignty movement” in Learning, food, and sustainability. ed. J. Sumner (New York: Palgrave Macmillan) doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-53904-5_8

Barlett, P. F. (2011). Campus sustainable food projects: critique and engagement. Am. Anthropol. 113, 101–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2010.01309.x

Blay-Palmer, A., Sonnino, R., and Custot, J. (2016). A food politics of the possible? Growing sustainable food systems through networks of knowledge. Agric. Hum. Values 33, 27–43. doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9592-0

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Clark, C. R. (2016). Collective action competence: an asset to campus sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 17, 559–578. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-04-2015-0073

Classens, M., Adam, K., Crouthers, S. D., Sheward, N., and Lee, R. (2021b). Campus food provision as radical pedagogy? Following students on the path to equitable food systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.750522

Classens, M., Hardman, E., Henderson, N., Sytsma, E., and Vsetula-Sheffield, A. (2021a). Critical food systems education, neoliberalism, and the alternative campus tour. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 45, 450–471. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2020.1829776

Cone, C., and Myhre, A. (2000). Community-supported agriculture: a sustainable alternative to industrial agriculture. Hum. Organ. 59, 187–197. doi: 10.17730/humo.59.2.715203t206g2j153

Dale, B. (2021). Food sovereignty and agroecology praxis in a capitalist setting: the need for a radical pedagogy. J. Peasant Stud. 50, 851–878. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2021.1971653

Delia, J., and Krasny, M. E. (2018). Cultivating positive youth development, critical consciousness, and authentic care in urban environmental education. Front. Psychol. 8:e02340. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02340

Galt, R. E., Parr, D., Van Soelen Kim, J., Beckett, J., Lickter, M., and Ballard, H. (2013). Transformative food systems education in a land-grant college of agriculture: the importance of learner-centered inquiries. Agric. Hum. Values J. Agric. Food Hum. Values Soc. 30, 129–142. doi: 10.1007/s10460-012-9384-8

Gramatakos, A. L., and Lavau, S. (2019). Informal learning for sustainability in higher education institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 20, 378–392. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-10-2018-0177

Gray, L., Johnson, J., Latham, N., Tang, M., and Thomas, A. (2012). Critical reflections on experiential learning for food justice. J. Agric. Food Syst. Commun. Dev. 2, 137–147. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2012.023.014

Green, A. (2021). “A new understanding and appreciation for the marvel of growing things”: exploring the college farm’s contribution to transformative learning. Food Cult. Soc. 24, 481–498. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2021.1883920

Guthman, J. (2011). “If they only knew: the unbearable whiteness of alternative food” in Cultivating food justice. Eds. Alkon, A. H. and Julian Agyeman, J. (Cambridge: The MIT Press).

House, V. (2014). Re-framing the argument: critical service- learning and community-centered food literacy. Commun. Literacy J. 8, 1–16. doi: 10.25148/CLJ.8.2.009307

Hunziker, S., and Blankenagel, M. (2021). “Multiple case research design” in Research Design in Business and Management. Ed. Reibold, C. : (Wiesbaden Springer Gabler).

IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute). (2022). Global food policy report: Climate change and food systems Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Kiely, R. (2005). A transformative learning model for service-learning: a longitudinal case study. Michig. J. Commun. Serv. Learn. 12, 5–22.

Levkoe, C. Z., Erlich, S., and Archibald, S. (2019). Campus food movements and community service-learning: mobilizing partnerships through the good food challenge in Canada. Eng. Sch. J. Commun. Eng. Res. Teach. Learn. 5, 57–76. doi: 10.15402/esj.v5i1.67849

McKim, A. J., Raven, M. R., Palmer, A., and McFarland, A. (2019). Community as context and content: a land-based learning primer for agriculture, food, and natural resources education. J. Agric. Educ. 60, 172–185. doi: 10.5032/jae.2019.01172

Meek, D., and Tarlau, R. (2016). Critical food systems education (CFSE): educating for food sovereignty. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 40, 237–260. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2015.1130764

Mejiuni, O. (2017). “Sustaining collective transformative learning” in Transformative learning meets Bildung. Eds. Laros, A., Fuhr, T., and Taylor, E. W. (Aylesbury: Brill).

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress 1st, Ser. The jossey-bass higher and adult education series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2011). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Michel, J. O., Holland, L. A. M., Brunnquell, C., and Sterling, S. (2020). The ideal outcome of education for sustainability: transformative sustainability learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2020, 177–188. doi: 10.1002/tl.20380

Mitchell, T. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michig. J. Commun. Serv. Learn., 14, 50–65.

Niewolny, K. L., and D’Adamo-Damery, P. (2016). “Learning through story as political praxis: the role of narratives in community food work” in Learning, food, and sustainability. ed. J. Sumner (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

Ojala, M. (2022). Prefiguring sustainable futures? Young people’s strategies to deal with conflicts about climate-friendly food choices and implications for transformative learning. Environ. Educ. Res. 28, 1157–1174. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2022.2036326

Ruben, R., Cavatassi, R., Lipper, L., Smaling, E., and Winters, P. (2021). Towards food systems transformation—five paradigm shifts for healthy, inclusive and sustainable food systems. Food Secur. Sci. Sociol. Econ. Food Product. Access Food 13, 1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01221-4

Sampson, D., Cely-Santos, M., Gemmill-Herren, B., Babin, N., Bernhart, A., Bezner, K. R., et al. (2021). Food sovereignty and rights-based approaches strengthen food security and nutrition across the globe: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.686492

Simsek, A. (2012). “Transformational learning” in Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. ed. N. M. Seel (Boston, MA: Springer)

Tarlau, R. (2014). From a language to a theory of resistance: critical pedagogy, the limits of “framing,” and social change. Educ. Theory 64, 369–392. doi: 10.1111/edth.12067

Keywords: critical food systems education, campus food systems alternatives, transformative learning, critical pedagogy, higher education, food systems, food justice

Citation: Deskin ZY and Harvey B (2023) Critical food systems education in university student-run food initiatives: learning opportunities for food systems transformation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1230787. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1230787

Edited by:

Lukas Egli, Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (HZ), GermanyReviewed by:

Erin Betley, American Museum of Natural History, United StatesAdam J. Calo, Radboud University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2023 Deskin and Harvey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zoë Y. Deskin, em9lLmRlc2tpbkBtYWlsLm1jZ2lsbC5jYQ==

Zoë Y. Deskin

Zoë Y. Deskin Blane Harvey

Blane Harvey