94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 18 July 2023

Sec. Climate-Smart Food Systems

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1214490

This article is part of the Research TopicClimate Science, Solutions and Services for Net Zero, Climate-Resilient Food SystemsView all 10 articles

Net-zero emission targets are crucial, given the environmental impact of the food and beverage industries. Our study proposes an environmentally focused Sustainable Business Model (SBM) using data from 252 food, beverage, and tobacco companies that reported to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). We investigated the risks, opportunities, business strategies, emission reduction initiatives, and supply chain interactions associated with climate change by analyzing their qualitative answers using the NVivo software. Following the grounded theory approach, we identified the Environmental Sustainability Factors (ESFs) that support businesses in meeting pollution reduction targets. The ESFs were integrated with Osterwalder's business model canvas to create an archetype focused on delivering “net-zero” or “carbon neutral” value to customers. The model's efficacy is enhanced by the advantages and motivations of environmental collaborations. The paper provides critical support for sustainability theories and assists Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to develop strategic business models for net-zero emission targets.

Climate change disasters (floods, earthquakes, bushfires, hurricanes etc.) are not limited to highly polluting countries and the regulatory bodies and governments have now realized the global nature of this problem, and that the only solution is to reduce and eliminate Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions at a global scale. The latest developments in the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have also clarified the importance of limiting global heating to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (Pörtner et al., 2022). To avoid major climate catastrophes, human-caused emissions must fall to half of the 2010 levels by 2030 and to net zero by 2050 (Salas et al., 2020). The Paris Agreement acts as a landmark in this regard, as 196 nations established an objective of net-zero emissions by the year 2050.

Businesses play a crucial role in achieving these global targets. Not only governments and shareholders, but customers also push the companies to develop net-zero targets in line with the Paris Agreement and IPCC reports. To achieve carbon neutrality goals, businesses need to reduce emissions from all sources to as close to zero as possible—material sourcing, transportation, operations, energy consumption, and buildings and infrastructure. Any remaining emissions must also be balanced by capturing CO2 emissions from the atmosphere through reforestation, peat and moss plantations, and the installation of Carbon Capture Technologies (CCTs) (Salas et al., 2020). A thorough understanding and analysis of three scopes of business emissions is critical in this regard: scope 1 refers to the direct emissions from on-site operations; scope 2 refers to the emissions from on-site energy usage; scope 3 includes all other indirect emissions from upstream and downstream supply chains (Luo and Tang, 2014). Among other sectors, food supply chains are considered highly emission-intensive, accounting for 35% of global GHG emissions mostly associated with cattle farming and land usage (Costa et al., 2022).

Environmental management of food supply chains is distinguished from other industrial supply chains because of the unique characteristics of food items including perishability, hygiene level, food contamination, and nutrition management. Many researchers and engineers have optimized the food supply chains in the context of sustainability, but a major challenge for researchers and industrialists is to achieve an ideal supply chain solution (Hammami and Frein, 2014). By ideal supply chain, we mean the one that leads to net-zero emissions of a product or company. Considering the challenges food supply chains pose to climate targets, researchers have started developing frameworks and models for food companies to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. However, there is a clear research gap when it comes to the development of an environmentally sustainable business model that delivers a net-zero value proposition. In this regard, a generic sustainable business model derived from benchmark food companies is critical to motivating both large and small enterprises to play their role in meeting global net zero emission targets.

Traditional business model canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) must be exploited across all its 9 constructs (customer value proposition, customer segments, customer relationships, channels, key activities, key resources, key partnerships, cost structure, and revenue streams) to optimize their interdependences in delivering net zero value proposition to the customer. Sustainable business models have emerged drastically, driving businesses to influence social and environmental sustainability standards. In this context, a Sustainable Business Model (SBM) is defined as an extension of the traditional business model with additional sustainability components, promoting the creation, capture, and delivery of ecological, social, and economic value (Bocken et al., 2014). An ecological or environmental value proposition is critical considering the latest developments (international environmental law, convention on biological diversity, Kyoto Protocol, Paris Agreement, UN SDGs) and businesses are looking for net-zero/carbon-neutral business models to meet their environmental regulations.

Our study intends to develop a sustainable business model with a net-zero value proposition by using the enterprise climate change data reported to Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) in 2020. The CDP is a non-profit organization that runs the global disclosure system for companies, cities, states, and regions to administer their environmental impacts (Chen et al., 2021). Also, it employs an essential role in regulatory systems, driving companies to conform to global environmental standards (Depoers et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021). Companies report to CDP to reflect their vision and efforts toward achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and carbon neutrality targets. CDP has also become a vital platform for food manufacturers to showcase their efforts in reducing emissions across their supply chains. Moreover, a company can gain a competitive edge by disclosing to CDP and positioning itself as a leading environmentally conscious company (Depoers et al., 2016).

CDP categorizes the survey to obtain information across all scopes of emissions, i.e., scope 1, scope 2, and scope 3 emissions. The GHG Protocol requires reporting of Scope 1 and 2, while scope 3 is highly recommended but not compulsory (Ismail et al., 2021). However, our paper focuses on analyzing and interpreting the scope 3 related disclosure as it accounts for 90% of overall supply chain emissions. Managing scope 3 emissions is extremely critical to systematically achieving environmental goals. Therefore, we analyze enterprise disclosures of climate change-related risks and opportunities, emission reduction initiatives, business strategy, and value chain engagements to identify important practices required under different constructs of Osterwalder's business model canvas to deliver a net zero value proposition. This analysis will enable the development of a benchmarked SBM.

To reach the outcomes of the study, the paper is structured as; Theoretical background on climate change reporting, sustainable business models, and food supply chain management is presented in Section 2, followed by data analysis and methodology (Section 3) to identify promising environmental sustainability factors in food supply chains. This leads to results and discussion (Section 4) which systematically reviews the key constructs of a sustainable business model, provides industrial and theoretical implications of the study, and presents an archetype sustainability model for food, beverage, and tobacco firms to set and achieve net-zero emission targets. Thereafter, limitations and future directions are presented in Section 5, followed by the conclusion in Section 6.

The first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol (2008-2012) aimed to reduce human-caused Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions to an average of 5.2% below 1990 levels (Howarth and Foxall, 2010). However, an exception was made regarding the adjustment of the 1990 baseline, which helped many developed nations to meet these targets (Maraseni and Reardon-Smith, 2019). In the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol (2012-2020), developed nations committed to reducing GHG emissions by 18% below the 1990 baseline within eight years. However, this commitment proposed the use of indirect market-based mechanisms such as International Emissions Trading, Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementations to meet the reduction targets (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). Moreover, it also allowed the parties to carry forward their carbon credits from the first commitment, providing an advantage to many countries (Maraseni and Reardon-Smith, 2019). However, these exceptions and exclusions have faced criticism as they allowed developed countries to engage in greenwashing practices. These practices involve relocating their emission-intensive plants to non-regulated countries while benefiting from emission trading schemes and purchasing carbon credits. Nevertheless, the latest agreements at the 26th COP (Conference of Parties) and the sixth assessment report of IPCC (The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) have mandated that governments and companies focus on the reduction, elimination, and capture of GHG emissions from a cross-border perspective (Pörtner et al., 2022).

With the background of emerging climate change regulations for businesses, we reviewed the literature on the importance of CDP climate change reporting, sustainable business models and empowering strategies, and strategic environmental management in food supply chains. This allowed us to grasp sufficient theoretical knowledge to rebuild a sustainable business model with a net-zero value proposition for food, beverage, and tobacco firms.

Ismail et al. (2021) pointed out three types of international disclosure initiatives widely recognized in the sustainability field, which reflect the environmental strategy of firms. They are the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines, the Global Compact (GC) principles, and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). These initiatives are guiding companies to take responsible behaviors. Among others, the CDP is a vital project that could trace the amount of carbon emission during production and operations. Normally, information disclosure mechanisms allow the stakeholders including investors, customers, auditors, regulators, and others to understand the company's sustainability state. Moreover, these disclosures play an essential role in regulatory developments, exerting pressure on companies to conform to social and environmental standards (Cormier et al., 2005; Depoers et al., 2016). This also impacts companies' market reputation and the legitimacy of their commitment to preventing pollution. Furthermore, by engaging in CDP information disclosures, companies can enhance their brand image and maintain a persistent position among leading environmentally sustainable firms (Depoers et al., 2016).

CDP collects information on climate change-related risks and opportunities identified and actioned by leading companies. They further classify the environmental risks and opportunities in accordance with the drivers which allows firms to trace emission-intensive sources of their business (CDP, 2019b). CDP also inquires how these risks and opportunities affect the business strategy, helping the firms to integrate environmental management into their organizational strategy (Herold and Lee, 2019). CDP disclosure highly emphasizes supply chain engagements and systems perspective as the key determinants for reducing scope 3 emissions of a firm (CDP, 2019a). Through the CDP information, businesses can identify their supply chain hotspots and develop management strategies for sustainable supply chains that encourage the reduction of these emissions (Herold and Lee, 2019).

Consequently, the CDP possesses the ability to influence emerging regulations and raise the importance of carbon capture within companies. The CDP claims that its findings benefit organizations and those that use this information because it provides a medium for companies to assess their GHG emissions against external or internal environmental policies (Jain et al., 2015). With this context in mind, CDP is a significant source of vital information that could be used by a wide span of professionals from academics and tutors to policymakers and investors (Blanco et al., 2016). Fagotto and Graham (2007) support this phenomenon and argue that with a transparent system in place, the CDP could be a key component in raising the power of public opinion in the industrial sectors. Therefore, using CDP data to develop comprehensive sector-specific sustainability models is a potential doorway to meeting global net-zero emission targets.

In the context of management theory, business models emerged for companies to attain competitive advantage by strategic integration of various business model components (McGrath, 2010). However, researchers and practitioners have begun to look beyond the conventional paradigm of value generation solely for customers and companies. Instead, they have embraced a broader perspective that includes the generation of value for the environment and society as well (Comin et al., 2019). With these changing trends, stakeholder involvement rapidly increased and businesses started appraising stakeholder theory to deliver value for their Investors, shareholders, suppliers, employees, and partners alongside the customers (Hörisch et al., 2014; Tolkamp et al., 2018). Most recent sustainable business models have fortified the concept of the circular economy (Lahti et al., 2018), technology and stakeholder-driven innovations (Baldassarre et al., 2017), environmental stewardship (Csutora et al., 2022), and supply chain collaborations and industrial symbiosis (Roome and Louche, 2016; Tolkamp et al., 2018).

Research on the incorporation of sustainability factors into business models is still in its infancy, and sector-based research, more specifically, exhibits a significant gap (Ritala et al., 2018). There is a lack of managerial understanding when it comes to the feasible application of sustainability practices in existing business models (Bocken et al., 2014). The fashion and apparel sector dominates the research on the business model innovation (Todeschini et al., 2017; Kozlowski et al., 2018), where innovations and stakeholder collaborations are found to be the critical drivers of a functional and sustainable business model. The study conducted by Yip and Bocken (2018) highlights digitalization and resource recovery as crucial elements for developing a sustainable business model in the banking Industry. Another services-oriented study (Høgevold et al., 2015) linked stakeholder engagement in reducing the environmental burden to the success of SBM in the hotel industry. A distinctive research article on sustainable business models for the most criticized sector, energy, implies the development of a stakeholder network to generate, capture, and deliver value for the customers, business, environment, and society (Rossignoli and Lionzo, 2018). Creating an effective network of stakeholders is critical in promoting awareness, education and practice, and a sense of responsibility in involved parties, and ultimately the society (Tolkamp et al., 2018).

Therefore, research in sector-specific SBMs is still novel with only limited studies leading to the development of sector-specific sustainable business models (Høgevold et al., 2015; Barth et al., 2017; Franceschelli et al., 2018; Kozlowski et al., 2018; Rossignoli and Lionzo, 2018; Yip and Bocken, 2018). However, none of these studies discussed the implications of net-zero value propositions on other components of the business model. Moreover, these studies have not used a broad set of real companies' data to demonstrate the applicability and operationalization of SBM. In today's business landscape, delivering an environmental value proposition is not only imperative from an ecological standpoint but also holds the potential to strengthen businesses' core competencies, dynamic capabilities, and competitive advantage.

The food, beverage, and tobacco sector play a vital role in regional and global economies, contributing to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth because of the perpetual consumer demand it generates. The simultaneous growth in population and wealth demands more quantities and varieties of food, thereby intensifying market volatility while posing a threat to the limited natural resources of Earth (Zhu et al., 2018). Today, the major environmental sustainability issues in food supply chains include but are not limited to energy conservation, ecological deterioration, GHG emissions, and natural resource conservation leading to unprecedented effects of climate change and global warming.

Moreover, the stakeholder demand for transparency, food security, and food waste reduction has reached unprecedented levels and resultantly, food firms are pressurized to adopt environmentally sustainable business models. Therefore, government bodies, customers, and other stakeholders motivate the firms to develop sustainable business models centered around green practices such as eco-designing, green purchasing, green manufacturing, and green transportation. Such green practices facilitate the transition to a circular economy and contribute to global greenhouse gas emission reductions (Asif et al., 2020). Closed-loop Supply Chain (CLSC) models are also extremely popular in this regard (Guide and Van Wassenhove, 2009; Miemczyk et al., 2016) and extended CLSC models have included waste management and resource recovery activities as part of the loop to enable circular economy (Sgarbossa and Russo, 2017). Furthermore, the study conducted by Mondragon et al. (2011) has provided robust evidence to support the positive influence of supply chain integration level on both the reverse and forward components of a Closed-Loop Supply Chain (CLSC). Some recent researchers have worked on the potential integration of Blockchain Technology (BCT) in the supply chains as it can resolve many CLSC-related uncertainties including information discrepancies, transparency in environmental reporting, and emissions' data management (Saberi et al., 2019; Schmidt and Wagner, 2019; Asif and Gill, 2022; Asif et al., 2022).

However, the efficacy of strategic environmental initiatives and green practices depends on effective inter and intra-organizational collaborations (Asif et al., 2020). The existing literature challenges the conventional approach of simply pressuring suppliers to enhance their performance and places more emphasis on direct involvement in suppliers' operations to achieve environmental objectives (Nyaga et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013). The buying firm must effectively maintain its supplier's performance and capabilities. Numerous researchers have employed systems theory to analyze the importance of collaborations among diverse actors within the food industry. Since its development by Bertalanffy (1968), systems theory has found extensive application in different research sectors including the food industry which is characterized by complex stakeholder interdependencies (Caswell et al., 1998; Menrad, 2004; Asif et al., 2020). Systems theory rejects the notion of isolation and asserts that a system can only be competitive if all its components and sub-systems are well aligned, integrated, and maintain robust relationships (Whitchurch and Constantine, 2009). Therefore, the systems concept serves as one of the theoretical bases for our research, as we seek to integrate green practices across various components of SBM and explore their complex relationships.

To find the Environmental Sustainability Factors (ESFs) relevant to each component of Osterwalder's business model canvas, we used thematic data analysis of 252 firms from the food, beverage, and tobacco sector who reported their data to CDP in 2020. This will help in reinventing the business model for food, beverage, and tobacco firms with the integration of ESFs into relevant components of their business model and aligning critical environmental aspects with their organizational strategy.

These ESFs hold value not only for large enterprises but also for SMEs as they account for more than 50% of global business-sector emissions (OECD, 2022). SMEs face the pressing concern of potential competitive disadvantages and missed low-carbon opportunities if their business models do not adapt to the latest shifts in climate change trends. In this context, CDP defines SMEs as non-subsidiary organizations with fewer than 500 employees, which aligns with the definition proposed by SME Climate Hub and Science-based Targets Initiative (Project, 2021). CDP encourages SMEs to engage in CDP climate change reporting under the modules of energy, value chain emissions, management and resilience, and climate solutions.

Therefore, it is crucial for SMEs to determine the ESFs relevant to their business, integrate them into their business models, report the progress to CDP, and contribute toward global net-zero emission targets. The ESF-integrated business models will be useful for all members of food supply chains willing to rejuvenate their business strategy in current climate change uncertainties. In this regard, continuous situation analysis is critical to businesses' competitiveness and survival as argued in the literature—businesses need to be proactive in reinventing or changing their business model on sensing any change in the external environment (Jolink and Niesten, 2015).

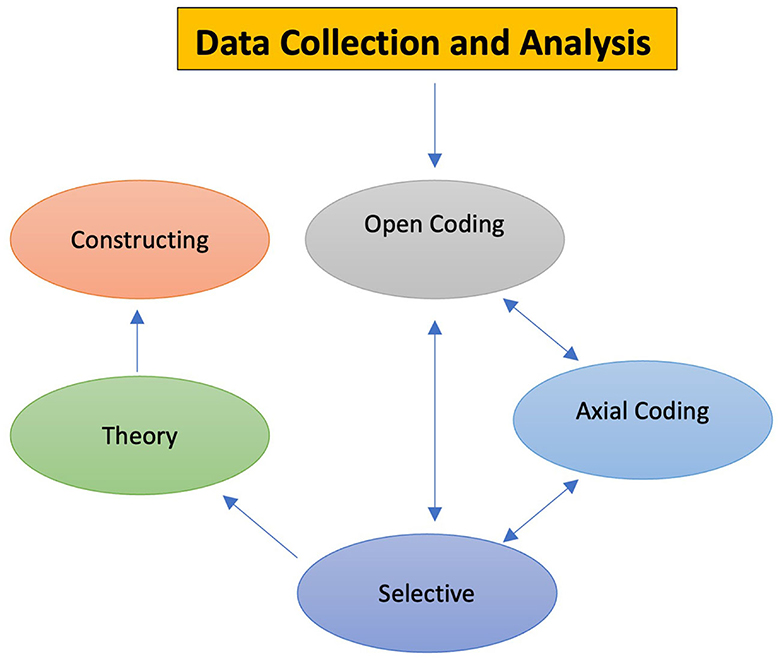

For analysis purposes, we adopted the well-famous six-step thematic analysis method proposed by Braun and Clarke (2012). Their method provides flexibility to authors dealing with complex qualitative data to move across the steps and make changes as deemed appropriate. To keep the analysis compact, we merged step 4 (reviewing themes) and step 5 (naming themes) and skipped the description of step 6 which is about writing the report. In steps 3 and 4 of the data analysis, we also implemented the qualitative analysis process proposed by Williams and Moser (2019). They suggested a three-step coding method including open coding, axial coding, and selective coding to develop a meaningful case from the analytical findings. As we tend to develop an environmentally sustainable business model case, this approach was very relevant and useful in finalizing the ESFs that ensure the success of an SBM from an environmental perspective. The three-step coding process is shown in Figure 1 where cyclic/continuous comparison among three stages of coding leads to a new theory or case.

Figure 1. Coding methods in qualitative analysis (Source: Williams and Moser, 2019).

Authors of this paper have extensively worked on CDP data in their previous research where they benchmarked the best companies to develop a generic framework for scope 3 emission evaluations in the food supply chains (Asif et al., 2022). Now, the authors extend their research using insightful CDP data to develop a sustainable business model applicable to the global food sector. Authors have gone through the relevant literature and existing sustainable business models to identify the research gaps that can be filled using CDP data i.e., a proof-based business model that achieves the environmental sustainability goals of food-related firms. For this paper, we focus on the CDP data reported under categories of risks and opportunities, business strategy, emissions reduction initiatives, and supply chain engagements. These categories were selected based on their relevance to the development of a new business model. For instance, cross-sectional analysis of risks and opportunities and business strategy helps in the identification of strategic environmental priorities, and data on emission reduction initiatives and supply chain engagements help in understanding key practices and approaches for the development of a collaboration-oriented business model.

Moreover, we probed into the initiatives taken by successful companies to mitigate carbon footprints and not only survived in the market but still are top-rated food, beverage, and tobacco brands. We selected different questions mentioned in Appendix 1 and aligned them in a sequence that supports our research. We also shortlisted the top-performing companies to analyze their methodology for reaching net-zero emission targets. These accountability measures enabled us to concise the required data and become familiar with ongoing approaches companies are using to propose, create, deliver, and capture environmental value through their SBMs.

This stage is critical as we need to organize the data in a meaningful and systematic way. We used a bottom-up also called an inductive approach for data coding as we intend to identify ESFs for a new business model related to food firms. This approach allows the researcher to code and interpret the existing data to develop new theories and models also known as the approach of grounded theory (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

For generating specific codes, we used NVIVO software as it helps to accomplish the qualitative analysis more systematically. At first, we set up the data in accordance with climate change-related risk and opportunity drivers as mentioned in the CDP report. Companies endorsing the risk and opportunity drivers were shortlisted and high-frequency drivers were analyzed for the corresponding descriptive responses from the companies. Analysis of descriptive responses helped us identify the codes relevant to achieving net-zero targets. For instance, shift in consumer preference is a reputational risk driver and its descriptive analysis helped in generating codes relevant to changing patterns in food consumption and demand.

Similarly, we analyzed the responses of 252 companies related to their supply chain engagements. Engagements with suppliers, customers, and beyond the value chain were critical in this regard. Table 1 demonstrates engagement types identified from the CDP report:

Around 100 companies did not mention any engagement with their suppliers, neither in terms of the type of engagement nor the plans for engagement. This is alarming as supplier engagement is one of the critical elements in addressing climate change-related risks and opportunities (Colicchia et al., 2018). Out of 152 companies that responded “yes” to engagement with suppliers, 122 companies disclosed their information on supplier engagement and their type of engagement was analyzed from qualitative responses to generate the codes.

A total of 625 codes were generated from CDP data through the analysis of open-ended questions. Repetitive and same meaning codes were scrutinized and finally, 150 codes were shortlisted. All the selected codes were either practices, initiatives, tactics, or other strategies that the food, beverage, and tobacco firms have used to improve their environmental performance. Highly repeated codes were considered critical and explicitly discussed under the “Results and Discussion” section. A list of 150 selected codes and their frequency is presented in Appendix 2.

At this stage, we clumped the identical and correlated codes under specific themes. We followed the open coding approach during this step as it aims at forming “concepts” from analyzed data or phenomena, also named as a concept-indicator model. Using a continual comparison of recorded codes, a concept-indicator model allows emergence of themes as an indicator of a concept (Saldaña, 2021). Essentially, open coding allows the researcher to examine through company responses and organize similar textual data i.e., concept indicators, in high-level initial thematic domains (Williams and Moser, 2019) as shown in Table 2.

Following Williams and Moser (2019) qualitative analysis framework, we applied axial and selective coding approach at this stage. While open coding helps to identify emergent themes, axial coding allows for further refinement, alignment, and categorization of thematic domains. Final themes (axial codes or core codes) emerged as aggregates of closely inter-related themes with strong supporting evidence. A constant comparison method was adopted to organize and refine the activities. The focus was to compare companies' responses, emerging themes, and relevant codes continually to develop new thematic categories also called as ESFs for further analysis during “selective coding.”

As mentioned by Flick (2022), selective coding or third-level coding follows axial coding at a higher level of abstraction that leads to story development. For a story or case (environmentally sustainable business model) to emerge from data categories, further refinement of data, selection of final thematic categories, and systematically aligning selective themes with constructs of business model canvas were critical. Therefore, selective coding can fuel expression and facilitate the construction of meaningful outcomes or a theory from qualitative data (Williams and Moser, 2019).

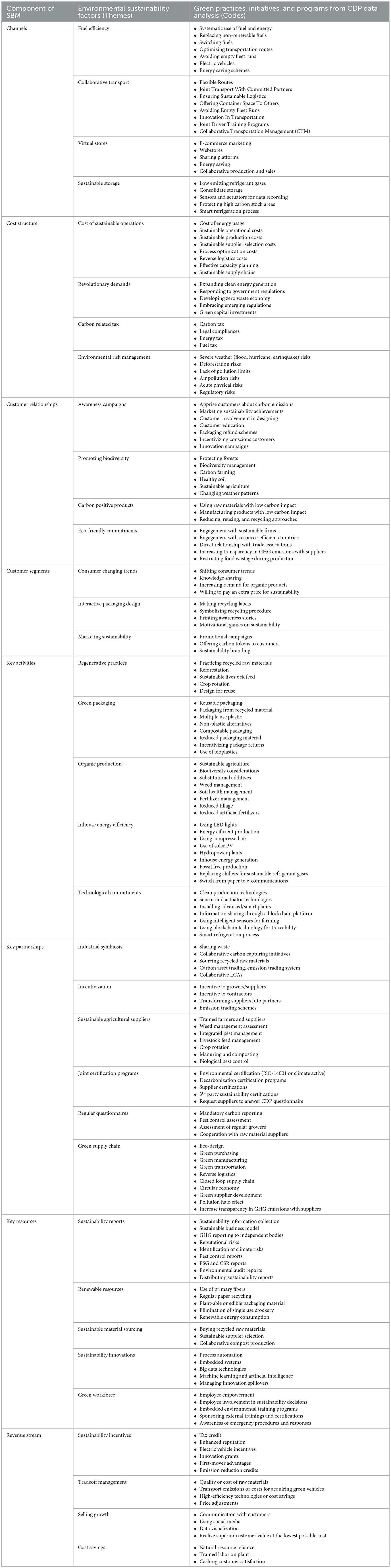

Following the three-step coding process (open, axial, and selective coding), we reached the best green practices, environmental initiatives, and sustainable methods that align with eight constructs of the business model canvas, while the ninth construct of “value proposition” is centralized at “net-zero” or “carbon neutral” value proposition for a product or service. The alignment of selective themes with the eight components of business model canvas is demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 3. Business model components, related Environmental Sustainability Factors (ESFs) and included best practices.

All the themes or ESFs mentioned above depict the solution to the modern problem of environmental depletion and degradation. In the business models, companies can adopt a set of ESFs that best suit their organizational structure, supply chain, and profitability. For selected ESFs, businesses can determine relevant green practices, initiatives, or programs adopted by best-performing food companies from Table 3. It is important to note that every food firm has a similar but distinct business strategy and some of the SMEs are not ready to fully immerse themselves in SBM. Therefore, our provided framework gives the flexibility to select low-cost ESFs to begin with and take a gradual approach toward the development of a fully sustainable business model.

As we discuss and align the generated themes (Environmental Sustainability Factors) with the components of a sustainable business model, we highly emphasize the interoperability of these components and the positive influences leading to the success of SBM. Following the suggestions of Guetterman and Fetters (2018), we also discuss case examples from CDP data, demonstrating the positive outcomes businesses have achieved through the integration of these ESFs in their organizational strategy and business models.

We will discuss the results of this study along with some best-case examples from CDP data through the lens of sustainable “value” creation, delivery, and capture. Details on most of the identified industrial practices and relevant ESFs are also explained in the context of the business model components.

Sustainable value creation refers to the key activities, key resources, and key partnerships that generate economic, ecological, and social value for the stakeholders (Evans et al., 2017). The conventional focus of value creation for customers has greatly shifted in recent years toward a larger system of stakeholders and diverse value concepts related to environmental, social, economic, and psychological perspectives of value building (Laukkanen et al., 2021). Figure 2 shows the graph for ESFs related to each component of value creation and frequency of relevant codes as found during CDP analysis.

Key partnerships play a cornerstone role in any sustainable business model. There could be several reasons for any firm to forge a partnership. For instance, optimization of business models, integrating climate risks into business strategy, implementing green supply chains, and acquiring renewable resources are potential key benefits of a partnership.

Companies seeking to introduce eco-friendly strategies must engage stakeholders along their value chains. CDP surveys provided us with some ground facts on collaboration strategies for building a sustainable business model. In their CDP reports, top-performing companies have demonstrated verifiable plans for surveying their suppliers and acquiring information on the treatment of raw materials. Regular on-site visits to monitor the production of key raw materials help in mapping structural sustainability in the supply chain. Companies also send regular questionnaires to measure key performance indicators and suppliers' impact on climate change. A surveying tool by The Sustainability Consortium known as “The Sustainability Insight System (THESIS)” is getting popular as it helps in determining the strategic direction of suppliers in meeting net-zero emission targets (Asif et al., 2022). Firms can learn from Walmart's efforts in developing collaborative environmental practices with their suppliers. Walmart's implementation of THESIS, Project Gigaton, and Blockchain Technology has allowed their suppliers (mainly farmers) to reduce 213.6 million metric tons of emissions from their operations in 2019 alone (Global, 2020).

Demonstration of waste handling technologies in industrial conferences and technology parks allows for industrial agglomeration leading to economic and centralized waste management (Cui et al., 2022). However, SBMs not only succeed through technology implementation or business innovations but innovations in the SBM itself are also major drivers (Yang et al., 2017). In this regard, SBM innovation demands reconceptualization concerning its relations with stakeholders. Many companies are transforming their relationships, enabling them to move from a transactional mindset to trust-oriented and sustained relationships with primary and secondary stakeholders (Evans et al., 2017; Serna et al., 2022). Secondary stakeholders including universities, communities, NGOs, media, and governments are the entities that do not directly engage in business transactions with a company but their collaboration is still crucial for SBM success (Bolton and Landells, 2015). The ecological system also acts as a primary stakeholder as it impacts the economic situation of a firm and “affects or gets affected” by the business. Therefore, SBM value should flow among all stakeholders, considering the natural environment and society as primary stakeholders, to enhance more opportunities for SBM innovations (Den Ouden, 2012).

Adopting GSCM enables firms to take a systematic approach toward reducing scope 3 emissions by engaging with key players in the value chain. Following the GSCM practices of eco-designing and green logistics, companies provide an accumulated set of instructions to their suppliers on reducing emissions (Eltayeb et al., 2011; Asif et al., 2020). Normalizing the practice of industrial symbiosis will potentially help to achieve net-zero carbon emission targets by the mid-century. Industrial symbiosis also enables a circular economy by allowing firms to transfer their waste or by-products to another firm as their production inputs (Yazan et al., 2020). Firms also collaborate with concerned communities and NGOs to widen the outcomes of sustainable supply chain practices (Sharma et al., 2021).

Orientation and management of important human, physical, intellectual, emotional, and financial resources are key to sustainable business model development. Let's consider some of these resource types, through which companies can successfully lower their scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions and enhance sustainability performance.

Raw materials are considered the primary resources for food, beverage, and tobacco manufacturing companies and are mostly sourced from crop-yielding facilities. Acute and chronic physical climatic conditions such as cyclones, floods, earthquakes, wildfires, rising sea levels, and rising global mean temperature should be continuously monitored as they greatly affect the production of agricultural raw materials (Global, 2020). Innovative technologies that deliver sustainability are considered paramount resources allowing for sustainable value creation and delivery for the customers and other stakeholders (Cui et al., 2022). Sustainability-oriented innovations (SOIs) have also become a major driver for environmental and social developments (Nakandala et al., 2023). However, the success of SOI firms depends on their strong exploration and exploitation capabilities, including raw material sourcing, and management of internal and external resources with a clear orientation (Behnam and Cagliano, 2019).

Energy is another major resource central to all operations of food, beverage, and tobacco firms. The usage of non-biodegradable fuels is a major cause of GHG emissions. Enterprises now strive to shift from non-renewable energy sources to meet their electricity and utility needs sustainably. The case example of a renowned Japanese company, Ajinomoto, is commendable as they shifted their fuel usage from petroleum oil to renewable power resources and demonstrated their positive impact on global warming through CDP reporting (Global, 2020). Such approaches to acquiring renewable and reusable physical resources are critical for food businesses to become carbon neutral by mid-century.

Farmers serve as the most vital human resource for food companies, as they play the pivotal role of supplying agricultural raw materials. A firm can reduce carbon emissions by yielding organic production through collaboration with farmers. Farmer awareness programs can educate them on the importance of organic production and mitigating GHG emissions. Companies can achieve a cleaner and greener environment by allocating their key resources to emission-intensive processes, promoting organic yielding of crops (Jolink and Niesten, 2015).

Not only sustainable raw material suppliers but the presence of a team of experienced and knowledgeable supply chain managers nurture the path to achieving net-zero targets (Blanco et al., 2016). Lack of motivation, management will, training, and sustainability awareness among employees are some impediments to low-carbon transitions (Sharma et al., 2021). Effective communication, training, incentives, and workshops on environmental issues can eliminate some of these barriers and promote sustainability knowledge within the firm. Environmental documentation including environmental policy, pollution prevention plans, emergency responses, environmental compliance reports, and environmental certifications also need to be communicated among employees. Following these human resource practices cannot only lead to the successful implementation of SBM but can also promote the state of GSCM and circular economy for the company (Pinto, 2020).

Financial resources predominantly affect the firm's efforts toward a low-carbon transition. Surveys, such as CDP, have proven that private sector firms can effectively achieve carbon reductions by leveraging operational economies, provided they possess a keen awareness and skillset in this domain (Blanco et al., 2016). With growing carbon pricing and induced carbon taxes, firms are compelled to play their role in achieving a low carbon economy while also benefiting their sales. Intellectual and emotional resources also play a credible role in sustainability promotion. Grasping the emotions of customers through motivational campaigns and rebuilding marketing policies according to their expectations will certainly lead toward reaching net-zero targets. Moreover, the urge for healthy, delicious, and organic food is fueling new trends of this era, allowing firms to promote biodiversity and natural food processing to appeal to new consumers (Jolink and Niesten, 2015). For instance, Danone Foods from France acquired White Wave in April 2017 and drastically shifted toward the production of plant-based organic foods and drinks. This strategy brought a wider choice to “flexitarians” (seldom vegetarian, often meat eaters) and promoted biodiversity as well (Global, 2020). Similarly, companies can use agronomic research to utilize present and new resources for building sustainable and resilient supply chains.

As our focus is the food, beverage, and tobacco sector, where the primary product consists of agricultural ingredients and raw materials that originate from crops and farming. So far, companies have made several strategic moves to implement sustainable cultivational practices, enabling carbon emission-free production. Biodiversity considerations, substitutional additives, weed management, soil health management, fertilizer and livestock feed management, crop rotation, and biological pest control are proof-based key practices helping CDP reporting agricultural firms to reduce their emissions and long-term costs simultaneously. Companies can also eliminate the GHG emissions in the livestock industry by using feed rich in amino acids as they are fully digestive to livestock and 100% absorbed by their bodies. Hence, zero concentration of carbon dioxide and nitrogenous compounds in their wastes leads to lower global warming (Global, 2020). General Mills associated with South Dakota University announced the opening of a state-of-the-art oats laboratory to conduct research in sustainable farming and support oat growers to develop resilient and profitable supply chains (Global, 2020; Caffe-Treml and Breeder, 2021).

Transformation of key activities is also critical to address the changing consumer trends. Barry Callebaut, a chocolate manufacturing company, estimated that customers are willing to pay 5-15% more for sustainable chocolates. The company embraced this new shifting trend and accordingly generated another stream of profit for the company. They committed to the “Forever chocolate program” to manufacture carbon-neutral chocolate products, taking revenue advantage while benefiting the environment (Global, 2020). Sustainable businesses also tend to integrate pollution control, pollution prevention, and product stewardship into key activities of their business to gain competitive advantage and dynamic capabilities (Klassen and Whybark, 1999). Pollution control refers to keeping pollution and emissions under specified limits as per industrial regulations or environmental certification requirements. This requires a transformation of key activities in their waste treatment plants and emission-capturing technologies. Pollution prevention refers to reducing or eliminating pollution by improving manufacturing and processing activities e.g., through efficient use of raw materials, energy, and water. Product stewardship calls for the integration of environmental sustainability across the design, production, and distribution activities and owning the responsibility of reducing emissions across the lifecycle of a product (Albertini, 2013).

Furthermore, sustainable material sourcing in line with eco-friendly product design is a crucial element of SBM, allowing the manufacturing and processing of carbon-positive products. Raw material processing plants driven by renewable and biodegradable fuels ensure green manufacturing (Asif et al., 2020). Eliminating manufacturing and packaging waste as part of key activities also enhances the positive outcomes of SBM. While adopting regenerative practices, companies should also strive to use non-plastic packaging i.e., paper bags and compostable packaging. In 2019, Coca-Cola company initiated a plan to replace hard-to-recycle material shrink wraps with 100% recyclable cardboard packaging, removing 4000 tons of single-use plastic per year across their territories (Bates, 2019). Besides this, they tend to change the color of Sprite bottles from green to transparent to avoid color waste and make them reusable (Global, 2020).

Value delivery refers to the physical distribution and accompanying communication that allows firms to deliver tangible and intangible components of value proposition to their customers (Norris et al., 2021). Figure 3 demonstrates critical ESFs relevant to channels, customer relationships, and customer segments that enable sustainable value delivery in a strategic business environment.

In terms of customer engagement on environmental issues, motivating customers to buy certified sustainable products is one of the key challenges concerning the premium prices (Ali et al., 2019). This is also evident from companies' CDP data but following a green marketing strategy, some firms have introduced incentives to shift customer interests toward environmentally friendly products. These firms also manufacture returnable products and maintain on-site recycling plants to develop a reciprocal relationship with their customers while reducing the environmental impact of their core activities (Global, 2020). The case of Del Monte Foods is worthwhile as they motivated customers to participate in the initiative of the “Sustainable Packaging Coalition” by labeling “how to recycle” on their packaging. This helped consumers to learn how to recycle accurately and where to find information specific to their municipality (Foods, 2021). Therefore, one of the key opportunities in the environmental context is to educate consumers on returnable and recyclable packaging through effective labeling and marketing schemes (De Boer, 2003). Another innovative technique is to customize labels and stickers of products with characters and multi-games for all ages to portray recycling.

Including sustainability stories of clients in annual reports and inviting them to the company's sustainability seminars not only strengthen customer relationships but also builds their confidence in the positive outcomes of customer-led sustainability programs (Eltayeb et al., 2011). Recording the climate change risk management process and achievements toward net-zero targets in annual sustainability reports and distributing it among the customers also draw positive outcomes in terms of customer collaborations and business growth. For instance, Arca continental SAB De organization publishes an integrated annual report which addresses sustainability making this document accessible to everyone. They disclose major information about environmentally friendly products such as Sprite blue bottles which is a 100% circular product and re-manufacturable to an infinite number of times (Global, 2020). Published reports will provoke customers to support the companies in their selling growth and to persistently strive toward achieving global net-zero targets.

Customer relationships not only stand on the environmental performance of a firm but also the perceived quality, lead time, and customer service. Just like specialty foods, sustainably manufactured foods also require distinctive approaches in retailing and after-sale customer experience (Calvo-Porral and Levy-Mangin, 2016). This fortifies the need of integrating customer expectations into key activities, channels, and cost structures of SBM. Consideration of customer engagements in SBM cannot only expand the customer segment of a firm but can also enhance cooperation in reducing the carbon footprint related to the flow of products in the supply chain (Williams et al., 2008).

Companies can achieve the target of low carbon emissions by integrating some pragmatic approaches in the channeling of products from upstream to downstream. Virtual stores and retail markets are two major channels for any company to deliver valuable products and services to their customers. Virtual stores or online retailing tend to centralize the resources, customers, and key partners while gaining benefits of the universal nature of the world wide web, geolocation tools, availability of personal technology and high-speed data networks (Amblee and Bui, 2011). All the partners share the same values, resources, and customers on e-commerce websites, reducing the intensity of resource consumption and promoting sustainability. However, a company sharing its resources on online platforms may face Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) related barriers such as interoperability issues, scalability and performance challenges, and customization challenges (Asif, 2018). Therefore, it is critical for businesses to monitor and address compatibility issues as they make any changes in their channeling operations.

Companies implement various logistics plans to address potential environmental risks. Collaborative transport is one of them, allowing businesses to reduce empty mileage across borders and switch to low-emission transportation modes i.e., electric and hybrid vehicles. Among several organizations that reduced their scope 3 emissions by optimizing transportation and fuel consumption, Clean Cargo Working Group is noteworthy. It is preferred by many companies as third-party logistics providers to transfer their goods with less fuel burning and lower carbon emissions. Another example is the MARS group which offers carbon-neutral parcel deliveries for retailers via delivery partner DPD. Parcel packaging provided by the DPD is also fully recyclable. Lightweight material and low water content of packaging minimized scope 3 emissions and had a wide effect on diminishing carbon footprints (Global, 2020).

Collaborative transport is not enough to reduce scope 3 emissions, but other measures should also be taken. In retail markets, companies should replace high energy-consuming coolers (refrigerators) with energy-efficient and HFC-free coolers. This can be done by replacing R12a and R134a with CO2-based refrigerant gases (Asif et al., 2022). A famous beverage brand Coca-Cola took a step ahead as they elevated the use of energy-efficient super coolers at consumer outlets (Global, 2020).

Recognizing that environmental degradation is a major risk posed to nature, companies should actively educate their supply chain partners on low-carbon casting packaging and transportation, thereby ensuring resilience in supply chains. The package's ability to support the efficient transport solutions (Williams et al., 2008) and management of costs and incentives related to the packaging waste logistics (Pazienza and De Lucia, 2020) add to the effectiveness of SBM. Furthermore, increasing the ratio of bio-based ingredients and Polyethylene terephthalates (PETs) in packaging can lead to net zero emission targets as recycled PETs have a depleted ratio of carbon as compared to other plastics (Benavides et al., 2018). In their prospect of becoming a net zero company, Coca-Cola also used recycled plant-based plastic and PETs and reached a 12% reduction in carbon footprint in 2019. Their transition aim is to use bio-based PET in all their packaging by the end of 2025 as renewable packaging has far less impact on climate change (Global, 2020).

The customer segment component of SBM refers to the individuals (B2C) or companies (B2B) that a business intends to target and serve. In the case of sustainable business models, the customer segment comprises individuals/companies who value the environmental performance of a product/service. Companies also tend to target specific sectors of customers from whom they can capture value in terms of revenue. In the food, beverage, and tobacco sector, customer segments can be highly diverse based on the type of products and age groups of consumers ranging from baby boomers to Generation Z consumers. However, food business proposing carbon neutrality and net-zero values to their customers should meet their expectations by generating substantial product/service value through their partnerships, resources, channels, and key activities while capturing sustainable value for their own business through cost structures and revenue streams.

The segment of sustainability-conscious customers is boosting and as per the outcomes of the 2020 Mckinsey US consumer sentiment survey of more than 100,000 US households, 60% of respondents agreed to pay more for sustainably packaged products (Frey et al., 2023). A NielsenIQ report also revealed that more than 66% of consumers tend to spend more on products from a sustainable brand and that consumer expectations around sustainable branding had a positive correlation with the increase in millennials and Gen Z consumers (North, 2022). Moreover, a 2022 report by First Insights claimed that around 90% of Gen X consumers are willing to spend an additional 10% or more for sustainable products compared to around 34% two years ago (Petro, 2022). Therefore, sustainability goals not only drive innovation and build resilience, but also open new markets, channels, and customer segments.

However, the current sustainability trend also demands further research to incorporate sustainability aspects for low-income customers. There is an opportunity to expand the consumer base by making claims in marketing endeavors and product labeling. Most successful claims as reported by Frey et al. (2023) include animal welfare (cage-free, free range, sustainable grazing), environmental sustainability (compostable, eco-friendly), organic positioning, plant-based (vegan), social responsibility (fair wage, ethical), and sustainable packaging (plastic free, biodegradable) and products with these ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) claims averaged 28% growth over the past five year period. Moreover, to sustainably capture the food market and extend their customer base, businesses need to continuously monitor and improve their sustainability aspects including information technology, circular economy, dynamic capabilities, value chain, and stakeholder engagement (Goni et al., 2021). Unilever was able to capture new customers in water-scarce markets by promoting “sunlight dishwashing” liquid that used much less water than other counterparts and achieved category growth of more than 20% in those markets (Sustainability, 2020).

Value capture includes the processes for securing profits from value generation and delivery and distributing the profits among relevant stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, and other partners (Chesbrough et al., 2018). It also includes integrated processes for controlling the costs of realizing and creating value. Figure 4 shows important ESFs to capture substantial value for the business and relevant stakeholders.

The cost structure essentially represents the aggregated expenses required to operate the business model. Every company which owns a sustainable model would make significant investments in low-carbon manufacturing and operations. Although pursuing carbon-positive production and manufacturing entails higher costs, it enables diversified long-term benefits not just in terms of emission reductions but also increased productivity and profitability (Trumpp and Guenther, 2017).

In general, sustainability initiatives accumulate high costs for the business but avoiding these initiatives can not only threaten the survival of the business but dramatically increase the costs in the form of fines and carbon taxes (Albertini, 2013). Corresponding to the amount of carbon dioxide emissions, a carbon tax can impose a high risk to the survival of a company. For instance, increasing fuel taxes on transport to facilitate decarbonization is another risk as it increases the logistics costs for the business (Sterner, 2007). Moreover, the usage of non-renewable resources in processing and manufacturing leads to considerable carbon emissions, resulting in the loss of business and customers. On the other hand, investment in energy-efficient technologies and renewable energies can increase companies' capital investment. Companies that rely on innovative technologies to meet their sustainability needs often face low Returns on Investments (ROI) (Isik, 2004). Furthermore, in organic production, the manufacturing of amino acids, processed seasoning, and sustainable fertilizers increases the direct costs for the business but improves their agricultural sustainability (Global, 2020). Shifting from petroleum oil to renewable fuel usage will lessen the scope 2 emissions but at a tradeoff of increased costs. Similarly, carbon disclosures and environmental certifications require human and financial resources but provide the company with new marketing avenues and credibility (Hahn et al., 2015). However, the costs of non-compliance and avoiding sustainability initiatives are far more than the costs of undertaking these initiatives. Therefore, businesses need to rejuvenate their investment strategies and cost management with a broader strategic vision. Pessimists may argue about the high costs of sustainability, but the benefits certainly outweigh the costs in terms of new revenue streams, customer retention, market shares, and reputation (Eltayeb et al., 2011).

Businesses new to sustainability initiatives can begin with win-win strategies i.e., initiatives that cut costs and improve environmental performance simultaneously. For instance, the study of Nakandala and Lau (2018) emphasizes local sourcing of fresh food and vegetables as it reduces logistics costs and emissions. Similarly, companies can improve their economic and environmental sustainability position simultaneously through cost-saving initiatives such as cogeneration of energy, waste sharing, transportation sharing, and water re-usage (García-Muiña et al., 2020). Companies can also stimulate long-term sustainability programs and reduce their carbon tax by adopting innovative and efficient technologies, reducing on-site energy consumption, using regenerative plants, and manufacturing carbon-neutral products. For instance, Altria's group of companies invested in the latest technology to convert their coal-fired boilers to natural gas-based boilers in three of their major manufacturing units. They completed the project in 2014 with a total cost of $2,950,000 and were able to generate annual savings of ~$3,200,000 as reported in 2020 (Global, 2020). The case of 3M is also commendable as the company saved $2.2 billion since the launch of its “pollution prevention pays” (3Ps) program involving eco-designing, green manufacturing, and reusing waste from the production (Sustainability, 2020).

Manufacturing and marketing low-carbon emission products are anticipated to augment market demand, thus increasing revenue for a company. To survive in the perpetually evolving market landscape, businesses should build up dynamic capabilities and change management skills to cope with the shifting trends. Adaptability and the ability to sense and seize opportunities are likely to enhance the revenue streams of a company.

Although historical research has argued on the negative impact of reactive environmental initiatives on the financial performance of a firm (Cordeiro and Sarkis, 1997; Klassen and Whybark, 1999; Lankoski, 2008; McPeak et al., 2010), in-depth studies comprising metadata have demonstrated positive financial outcomes for proactive environmental actions i.e., market-based returns (price-earnings ratio, price per share) and accounting based returns (return on equity, return on assets, return on investment) (Clarkson et al., 2011; Albertini, 2013; Beckmann et al., 2014). This has reinforced the famous Porter's depiction of pollution as an economic waste of a firm and achieving a “win-win” situation through corporate environmental management (Porter and Van Der Linde, 1995). Therefore, companies should look at the brighter side, considering environmental management an opportunity to enhance the financial returns for their company.

There is an economic term called tradeoffs, i.e., compromising on one thing to achieve another. To attain a sustainable business strategy firms should make some hard decisions on compromising the revenue for at least a short-term (Beckmann et al., 2014). For instance, using recyclable materials may cost more to firms but reduces their scope 3 emissions. To mitigate the tradeoff, companies can pursue smart packaging techniques to outweigh the cost disadvantage and reach a win-win situation (Williams et al., 2008). A Belgium company named Anheuser Bush identified a packaging preference by transitioning from one-way to returnable packaging. They first implemented the initiative in collaboration with waste collectors in Colombia to facilitate the retrieval and refilling of one-way bottles. Using this approach, they reduced the carbon footprint by more than 50% and saved $50 million in energy costs with negligible alterations to revenue streams (Global, 2020). Therefore, sustainability initiatives provide diversification in revenue streams for a business. Businesses not only generate revenue through B2B or B2C sales, but also through government-paid carbon credits, green tax incentives, income generated through waste sharing and transport sharing, and selling self-generated renewable electricity to the grid etc.

As discussed earlier, changing trends in consumer behavior present opportunities for companies to increase their revenues—adaptability is the key. Adaptability should be an integrated factor of “business strategy” allowing companies to take strategic actions and achieve competitive advantage in response to the changes in the external environment (Cui et al., 2022). Cases of high revenue-generating firms reveal that their environmental business strategies—clean technology, sustainability vision, product stewardship, and pollution prevention—not only add economic value to SBM but also social value in terms of poverty alleviation and fair distribution (Evans et al., 2017). The historical case of Watties marked a significant breakthrough as they initiated the “Grow Organic with Watties” campaign in partnership with their produce suppliers who couldn't meet the ever-increasing demand for organic vegetables. In terms of economic value, the initiative resulted in higher contract prices for farmers, charging as high as 310% of conventionally produced vegetables. Watties also capitalized on the shift in consumer trends, charging a premium of over 100% to their buyers in Japan while developing their market position as an environmentally progressive food producer (Global, 2020).

Various authors have suggested different methods including experimentation, the use of trial-and-error techniques, simulations, and pilot programs to discover sustainable business models for a range of industrial sectors despite the high resource needs and associated risks (Evans et al., 2017). However, we followed the method of analyzing real companies and proposed a generic business model that any company from the food, beverage, and tobacco sector can adopt to target the customer segment that appreciates net-zero enabled products or services. Being business-oriented research, this paper provides manifold implications for the food, beverage, and tobacco industry. Major contribution includes the development of the environmental tier of a sustainable business model (Figure 5) with integrated ESFs that can potentially help the firms to identify, implement, and monitor best green practices, business strategies, environmental initiatives, and compliances that lead to the achievement of net-zero emission targets.

Companies proposing net-zero value to their customers are often subsidized by value chain partners, NGOs, and governments. This enhances the intrinsic motivation for developing a circular economy where the product's end-of-life is managed through collaborative life cycle assessments and adoption of the 3R (reducing, reusing, and recycling) principle. Based on the importance of collaborations highlighted in literature and CDP disclosures, we also incorporated “collaboration motivations” and “collaboration benefits” as additional components of win-win SBM.

The presented environmental tier of SBM can act as a generic model for any food, beverage, or tobacco firm to systematically manage and control their operations toward meeting net-zero emission targets. Interested companies can select the ESFs in relevance to their business and for each of the selected ESF, they can identify relevant practices and initiatives from Table 3. Moreover, the study findings are critical for companies in the initial stages of setting environmental goals and want to determine low-cost environmental initiatives, to begin with. Following the recommendations provided in the “Discussion' section under cost structure and revenue stream, companies can learn to manage the trade-offs and adopt win-win strategies to initiate sustainable business modeling.

The findings of the study also provide valuable insights into the strategies and practices that businesses can incorporate into their processes to achieve sustainability goals. With a better understanding and implementation of ESFs, businesses can improve their business process management maturity by aligning their operational strategies with sustainability objectives. Therefore, this research can be used as a guide to integrate environmental consciousness into business models and improve their overall maturity in managing sustainable processes. Finally, in response to the rapid shift in food production and consumption trends, it has become indispensable for firms to develop sustainable business models that create, deliver, and capture value not only for the customers and business but also for the environment and society.

Our study reinforces the argument of Boons and Lüdeke-Freund (2013) that a major challenge to the success of SBM is the engagement efforts of a firm in their interactions with internal/external stakeholders and the business environment. Analysis of real company data depicts the veracity of “instrumental stakeholder theory” as it explains how a firm's actions toward building stakeholder relationships impact the performance of the firm. Our analysis and recommendations around “key partnerships,” “key resources,” and “customer relationship” suggest a strong connection between the success of environmental initiatives and stakeholder engagement. Moreover, by proactively integrating stakeholder expectations in environmental strategies and initiatives, firms can gain a competitive advantage in novel sustainability markets, and ultimately enhance their profitability too. “Theory of collaborative advantage” is another practice-based theory about the management of inter-organizational partnerships to achieve mutual benefits. The theory postulates two major reasons for collaborations i.e., self-interest or moral reasons. Self-interest motivates the firms to collaborate and gain certain financial and non-financial advantages for their firm while “moral” reasons motivate the firms to collaborate for the betterment of the community and environment (Huxham, 1996). Furthermore, the founders of the theory call for further development and testing in the moral reasoning domain (Vangen and Huxham, 2013), and therefore, our research contributes significantly as it hypothesizes that the primary reason for businesses to undergo collaborations concerns the environment and community, while secondary reasons include market or financial advantages.

Our research highly aligns with “systems theory” as we found a high degree of overlapping, cross-sectioning, and interdependence of ESFs across all constructs of the business model. SBMs are complex structures consisting of almost everything a firm does to offer a product/service to its customer including sourcing, production, packaging, retailing, and handling returns. For instance, a firm's decision to change the packaging material in their physical resources will certainly impact their packaging process (key activities), which in turn affects the cost structure and channels (how these new packages are handled), leading to a change in partnership and revenue stream. Therefore, a systems approach will allow firms to become strategic in their decision-making and timely check the impact of new practices and initiatives across the business model and supply chain. This is obvious to most of the companies' higher managements and they have started moving from incremental improvements to systematic approaches that create a net positive impact (Winston, 2022).

Provided the scope of the study, this paper has addressed scholarly concerns of ready-to-implement SBM for food, beverage, and tobacco firms considering the high consumption of this sector and escalating consumer demands for products with net-zero emissions. However, various limitations were identified during the course of the research that are mentioned below along with the future avenues for their resolution.

Exclusivity of analyzed firms. One of the highly argued limitations of CDP-based research is the exceptionality of firms voluntarily disclosing their environmental information to CDP. Since the beginning of CDP in 2000, it has persuaded the world's largest listed firms to disclose their carbon data on ethical grounds (Depoers et al., 2016), and therefore, its portfolio is dominated by leading corporates in terms of market share and CSR. Researchers should analyze the carbon disclosure of firms included in the CDP database along with other SME-oriented databases such as OECD, GRI, and IFAC to develop sustainability models with a wider outreach.

Furthermore, considering the credibility issues around the voluntary and self-reporting nature of CDP data, our paper incorporated scholarly articles in the discussion section that used primary industrial data to identify the most critical environmental sustainability factors.

Nature of data. Our study has approached the research questions through a cross-sectional analysis of firms that reported to CDP in 2020. Therefore, our study is unable to show trends and changes in carbon reporting over a longer period. Future researchers can adopt a time-series model to determine the positive impacts of firms' environmental initiatives over a time range of a few years. In such research, the data complexity can be managed by applying product range-based filters to develop generic net-zero SBMs for different product categories. Moreover, our research outcomes are only applicable to the food, beverage, and tobacco sector, but provides an opportunity and framework template for future scientists to develop SBMs specific to other industrial sectors.

Research is dominated by the environmental aspect of sustainability. Our paper is not highly focused on the economic and social tiers of SBMs as the motivation was to develop a comprehensive model for reaching net-zero emission targets. Further research is required to develop integrable tiers of social and economic SBMs that also fortify the firm's efforts around net-zero plans. Researchers can also demonstrate valuable insights by analyzing the impact of such net-zero based SBMs on social, economic, and policy dimensions of corporate business.

In conclusion, our paper presents a novel approach toward developing a sustainable business model in the food, beverage, and tobacco sector. The model is driven through a comprehensive analysis of 252 food, beverage, and tobacco firms that disclosed their environmental data to CDP in 2020. By analyzing their qualitative responses using NVivo software, we identified a range of environmental sustainability factors (ESFs) helping the firms to meet their emission reduction targets. The ESFs were prioritized and mapped with various components of the business model canvas, to effectively propose a “net-zero” or “carbon-neutral” value proposition to customers. Considering the theoretical and practical implications, our research has addressed a significant gap in terms of real data-driven SBM exclusive to food, beverage, and tobacco firms and provided a practical guide for firms to initiate strategic business modeling and achieve their net-zero emission targets. The research also implied the importance of supply chain collaborations and effective engagements with stakeholders as a critical success factor of SBM. Moreover, it provides a set of 150 green practices aligned under relevant ESFs so that start-up firms and SMEs can select best-fit green practices and operationalize their SBMs. Finally, the research opens a doorway for the development of more sector specific SBMs that can lead businesses to not only add value to their business and customers but also to society and the environment.

The author team of this paper have been conducting research on environmental management of food sector for past 4 years and this paper is 3rd in series of their high-quality journal articles. The first one related to green supply chain management adoption in food sector (published in Journal of Cleaner Production) and the second one was about Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) based case analysis of high selling, ready to eat, food products (Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management Journal). While developing this third paper, we were captivated by high quality literature from Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems (FSFS) in this field. After analyzing the findings of this paper against the aims and scope of FSFS, we found a high degree of relevance and decided to publish it in this esteemed journal. Scope of the paper extends from strategic organization management to environmental sustainability management and therefore, practical contribution of authors from diverse disciplines was important for successful completion of this paper.

Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) database access is subscription based. Western Sydney University (WSU) provided access to the dataset analyzed in this research. Requests to access the data should be directed to www.cdp.net.

MA: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualizations, formal analysis, and writing-original draft. HL: supervision, project administration, and formal analysis. DN: validation of the results, data curation, and editing. HH: writing-review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The Candidature Support Funding (CSF) from RTP and SDG Grant from Western Sydney University funded APC and professional proofreading services for this paper. SDG Grant No.: 20551.72050.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1214490/full#supplementary-material

Albertini, E. (2013). Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Org. Environ. 26, 431–457. doi: 10.1177/1086026613510301

Ali, A., Xiaoling, G., Ali, A., Sherwani, M., and Muneeb, F. M. (2019). Customer motivations for sustainable consumption: investigating the drivers of purchase behavior for a green-luxury car. Bus. Strategy Environ. 28, 833–846. doi: 10.1002/bse.2284

Amblee, N., and Bui, T. (2011). Harnessing the influence of social proof in online shopping: the effect of electronic word of mouth on sales of digital microproducts. Int. J. Electron. Commerce 16, 91–114. doi: 10.2753/JEC1086-4415160205

Asif, M. S. (2018). An appraisal of issues faced by manufacturing companies, when selecting an enterprise resource planning (Erp) system. Int. J. Bus. Gen. Manage. 7, 1–8.

Asif, M. S., and Gill, H. (2022). “Blockchain technology and green supply chain management (GSCM)–improving environmental and energy performance in multi-echelon supply chains,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (IOP Publishing). doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/952/1/012006

Asif, M. S., Lau, H., Nakandala, D., Fan, Y., and Hurriyet, H. (2020). Adoption of green supply chain management practices through collaboration approach in developing countries–From literature review to conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 276, 124191. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124191

Asif, M. S., Lau, H., Nakandala, D., Fan, Y., and Hurriyet, H. (2022). Case study research of green life cycle model for the evaluation and reduction of scope 3 emissions in food supply chains. Corporate Soc. Respons. Environ. Manage. 29, 1050–1066. doi: 10.1002/csr.2253

Baldassarre, B., Calabretta, G., Bocken, N., and Jaskiewicz, T. (2017). Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: a process for sustainable value proposition design. J. Clean. Prod. 147, 175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.081

Barth, H., Ulvenblad, P.-O., and Ulvenblad, P. (2017). Towards a conceptual framework of sustainable business model innovation in the agri-food sector: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 9, 1620. doi: 10.3390/su9091620

Beckmann, M., Hielscher, S., and Pies, I. (2014). Commitment strategies for sustainability: how business firms can transform trade-offs into win–win outcomes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 23, 18–37. doi: 10.1002/bse.1758

Behnam, S., and Cagliano, R. (2019). Are innovation resources and capabilities enough to make businesses sustainable? An empirical study of leading sustainable innovative firms. Int. J. Technol. Manage. 79, 1–20. doi: 10.1504/IJTM.2019.096510

Benavides, P. T., Dunn, J. B., Han, J., Biddy, M., and Markham, J. (2018). Exploring comparative energy and environmental benefits of virgin, recycled, and bio-derived PET bottles. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 9725–9733. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00750

Bertalanffy, L. V. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. G. Braziller.

Blanco, C., Caro, F., and Corbett, C. J. (2016). The state of supply chain carbon footprinting: analysis of CDP disclosures by US firms. J. Clean. Prod. 135, 1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.132