- 1Research Center for Economy of Upper Reaches of the Yangtse River, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, China

- 2Qinghai University Library, Qinghai University, Xining, China

- 3Institute of Nationalities, Guizhou Academy of Social Sciences, Guiyang, China

- 4School of Economics and Management, Taiyuan Normal University, Taiyuan, China

Introduction: Extant literature has extensively explored farmland transfer ‘s impacts, confirming its essential role in poverty alleviation. How-ever, most studies focus on poverty measures that exclusively emphasize current poverty status without adequately addressing the potential of falling into or remaining in poverty. Furthermore, the role of farmland transfer in helping the smallholder house-holds in rural areas appears to be underexamined in the literature.

Methods: To address this knowledge gap, this study investigates whether farmland transfer can reduce household vulnerability to poverty. A theoretical framework is developed to capture the mechanism by which farmland transfer has a vital role in smallholder households and impacts the probability of being poor in the future. The China Family Panel Studies Survey data set from 2010 to 2018 is used to explore this issue.

Results and Discussion: The results show that land transfer-out households are seemingly the most effective at reducing vulnerability, whereas the reduction effect is not obvious among transfer-in households. Specifically, the vulnerability of transfer-out households is reduced by about 39.52%. Furthermore, we analyze the reasons for heterogeneity in the poverty reduction effects and find that the key mechanism is on the labor resource allocation decision the heterogeneity of the effects of different types of income. Actually, for transfer-out households, farmland transfer can increase the probability of migrant work and business opportunities, as well as the labor input for non-agricultural production, which helps to reduce vulnerability to poverty. On the other hand, for transfer-in households, they will invest more labor in agricultural production and increase agricultural inputs, whereas increased inputs to agricultural production do not actually reduce vulnerability to poverty. Transferring out land can significantly increase farmers’ wage income and thus compensate for the loss of farm income; however, the increase in farm income generated by transferring in land roughly offsets the loss of wage income for farmers. This study provides a new research perspective on the long-term effects of farmland transfer on rural poverty.

1. Introduction

Poverty eradication is a common goal of humanity. In recent years, as the reform of China’s rural land system continues to progress, land transfer decisions are playing an increasingly important role in poverty alleviation. According to property rights theory, farmland transfer can contribute significantly to income growth as well as being an essential means for farmers to overcome poverty (Deininger and Jin, 2005). This is due to the fact that an unrestricted market for the transfer of land property rights allows for the transfer of comparative advantage, allowing both transfer-in and transfer-out farmers to specialize in the occupation to which they belong, increasing farmer productivity and their ability to combat poverty risks (Besley, 1995; Cheynier et al., 2013). Nonetheless, there are still many differences in the conclusions of existing researches on the impact of farmland transfer on rural poverty. Clarifying the impact of land transfer on farm poverty has important implications for poverty alleviation in underdeveloped areas.

Although most studies believe that farmland transfer can increase farmers’ incomes (Tan et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021), improve the productivity of farmers (Lu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020), and reduce the risk of poverty for farmers (Wang et al., 2022), some scholars point out that farmland transfer is a double-edged sword that may also aggravate the risk of poverty for farming households (Li et al., 2021; He et al., 2022). The reason is that land is an important safeguard for farmers’ livelihoods, having to carry out a variety of functions such as production, livelihoods and social security (Devereux, 2001; Davies et al., 2009). Farmers may lose their most fundamental source of revenue of land alienation, increasing their risk of poverty (Kanbur and Squire, 2001). Farmland plays a more prominent role in resisting poverty risks for Chinese farmers. Because small farmers are typical characteristics of rural areas in China. China’s per capita cultivated land area is about 0.097 hectares, far below the world average level, which leads to the agricultural land playing a more important role in the basic living security of farmers (Adger and Kelly, 1999; Dercon and Christiaensen, 2011).

Further analysis reveals that there are currently two main reasons why scholars believe that the poverty-reducing effects of farmland transfer are wildly different. First, self-selection in farmland transfer is ignored. As agriculture is disadvantaged in terms of marginal output compared to non-agriculture (Christiaensen et al., 2011; Dev, 2017), farmers who are willing to transfer to land may themselves have significant advantages in terms of economic power, education and farming operations (Lagakos and Waugh, 2013), i.e., there is “self-selection.” Most of the previous literature uses OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) estimation methods to measure the impact of farmland transfer on poverty, without taking into account the “self-selection” of the farmers in the sample, which may lead to biased estimation results. Second, the differences in the impact of farmland transfer on transfer-in and transfer-out households are ignored. Most studies usually study transfer-in and transfer-out households as a whole and do not take into account the different poverty risk pathways of transfer-in and transfer-out households after participating in farmland transfer, which inevitably leads to a misestimation of the poverty reduction effects of farmland transfer. As a result, despite the fact that a great number of studies on the poverty-reducing impacts of farmland transfer have been done, discrepancies in study methodologies and views have not resulted in total agreement on the current findings.

In addition, existing studies have overlooked one important issue, namely that only the short-term effects of farmland transfers have been analyzed, without considering the long-term effects. This is because poverty-measurement indicators are an ex-post measure that can only be used to statically measure the welfare status of an individual or household at a point in time, and do not reflect future welfare status and the associated risks (Garmezy, 1991; Moser, 1998; Dercon and Krishnan, 2000). The impact of farmland transfer on the current welfare of rural households is a short-term effect, but rural households may fall into poverty in the future as a result of various negative shocks, so policies based on the short-term effects of farmland transfer do not apply to those households that will fall into poverty in the future (Bouzarovski, 2014; Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015). It is well known that the “prevention” of poverty is far more important than the “cure” of poverty (Eriksen and O’Brien, 2007), and that the “prevention” of poverty requires an assessment of poverty vulnerability. Poverty vulnerability was introduced by the World Bank in the 2002 World Development Report to measure the likelihood of an individual or household falling into poverty in the future (Gillard et al., 2017; Koomson et al., 2020). Vulnerability to poverty is an ex-ante measure of poverty for farming households that can be used to measure the long-term effects of the transfer of farming land in a forward-looking manner, so that households that are likely to fall into poverty in the future can be accurately identified and policies can be developed to effectively prevent them from falling into poverty in the future (Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015; Koomson et al., 2020). On the basis of previous researches, we consider the farmland transfer of Chinese farmers as a quasi-natural experiment and re-examine the poverty reduction effects of farmland transfer from the perspective of poverty vulnerability.

In recent years, the Chinese government has paid great attention to improving the rural land system and made farmland transfer policies an important initiative to promote an effective link between smallholder farmers and modern agriculture (Lu et al., 2020; Fei et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). For a long time in the past, China’s rural land has been a collective land property that cannot be bought and sold freely in the market like other commodities (Xu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). The old land policy has, to a certain extent, constrained agricultural productivity and deterred rural labor from moving to higher-income sectors and regions (Ye, 2015; Huang et al., 2020). To address this issue, the Chinese government has introduced a series of policies to continuously improve the land property rights system (Li et al., 2015; Kong et al., 2018). In 2017, China’s Rural Work Conference plainly explained that farmland transfer should be accelerated, modest magnitude operations should be developed, the management structure should be optimized, and the promotion of scale operations should be combined with driving farmers to increase their income (Deng et al., 2019). In 2020, China’s “Document No. 1” also states that farmland transfer profits should be progressively provided in the growth of rural operations (Liu et al., 2017). By the end of 2020, 37.3 million hectares of farmland had been transferred from farming households in China, accounting for 35% of the country’s arable land area (Zhou et al., 2020). In the process, a large amount of surplus labor is generated and transferred to cities, supporting urbanization and industrialization (Andreas and Zhan, 2016; Wang and Zhang, 2017), and also breaking the disadvantages of rural land fragmentation by means of farmland transfer (Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2018), providing conditions for agriculture to achieve scale and modernization (Wilmsen, 2016; Wang and Zhang, 2017), and becoming an effective path to poverty eradication practices in rural areas of China (Feng et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018). In this context, does farmland transfer serve the function of “poverty reduction” for the current poor, but also “poverty prevention” for the quasi-poor who may fall into or return to poverty in the future? The answer to this question has important theoretical and practical implications.

Utilizing tracking data from five rounds of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2010–2018, we regard the farmland transfer practices in rural China as a quasi-natural experiment and investigate its impact on poverty vulnerability based on a progressive DID model. This paper mainly answers the following questions: (1) Does farmland transfer reduce poverty vulnerability of farmers in China? (2) How does the impact of farmland transfer on poverty vulnerability differ between transfer-out farmers and transfer-in farmers? (3) What is the underlying mechanism involved?

There are three contributions of this study. First, in terms of research subjects, we explored the relationship between farmland transfer and farmers’ future poverty from the perspective of poverty vulnerability. It is well known that the “prevention” of poverty is far more important than the “cure” of poverty. Existing researches ignore the impact of farmland transfer on future poverty prevention. Poverty vulnerability, as a dynamic, forward-looking ex ante poverty indicator, sheds fresh light on the topic of future poverty risk and the long-term impacts of farmland transfer on poverty alleviation. Second, in terms of the identification strategy, this paper mainly uses the DID method, which helps eliminate the interference of self-selective behaviors in the farmland transfer process, obtain the net effect of the farmland transfer on farmers’ future poverty. Most of the previous literature has not considered the issue of sample selection bias in models when analyzing the impact of farmland transfer on poverty, but whether or not farmers engage in farmland transfer is likely to be the result of self-selection. This is because farmers’ farmland transfer decisions can be influenced by household resource endowments, thus leading to the fact that whether farmers choose to transfer land or not is not completely random, and if traditional econometric methods are still used for estimation, the accuracy and validity of the model estimates will inevitably be reduced. Third, in terms of the research conclusions, this paper finds that farmland transfer can reduce the poverty vulnerability of transfer-out farmers, but has no significant effect on the poverty vulnerability of transfer-in farmers, which provides an important reference for the design and implementation of China’s land policies in the future.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 is the literature review and research hypotheses. Section 3 introduces the identification strategy, variables, and data for this study. Section 4 tests the three hypotheses and presents the regression results. Section 5 covers the analysis of the impact mechanisms. Section 6 provides the discussions and related policy implications. Section 7 summarizes the main conclusions of this paper.

2. Theoretical analysis and hypothesis

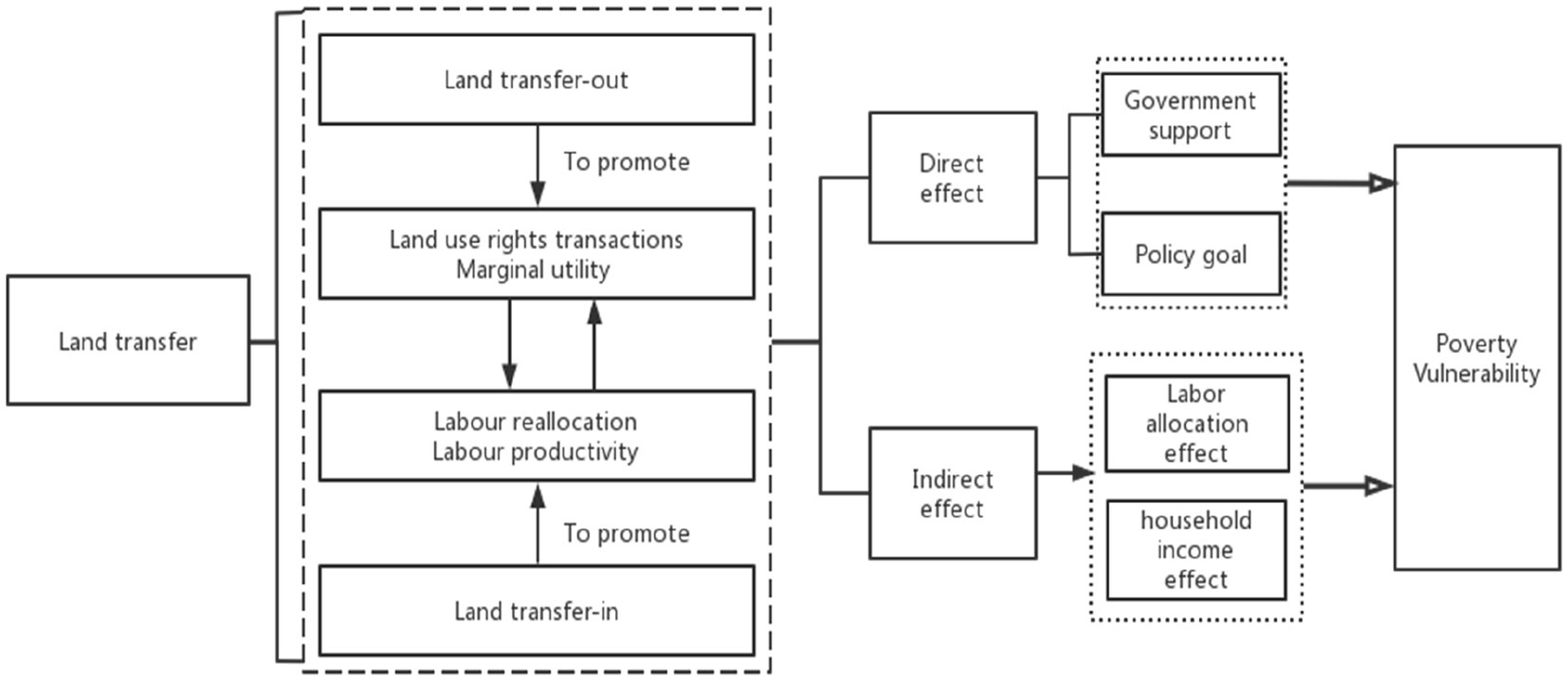

2.1. Direct effect analysis

2.1.1. Theoretical analysis of the transfer-out land affecting poverty reduction

Land is the main asset for most rural households (Ravallion and VanDeWalle, 2008). However, uncertainty and legal barriers prevent land from being bought and sold freely in the market like other commodities (O’Laughlin et al., 2013; Wang and Zhang, 2017). According to modern property rights theory, property rights are the socially enforced right to choose between multiple uses of a good, including the right to own, possess, dominate, use, benefit and dispose of the good (Mayhew, 1985; Furubotn, 1988). China’s land property rights system has been in a constant process of change and improvement, and the introduction of the “three rights” to contracted land in 2014 means that farmers are given the right to dispose of and earn income from their land management rights, which can be freely transferred in the market, activating the performance of land property (Wang and Zhang, 2017; Zhou et al., 2020). The transfer of land out of the household can reduce the occurrence of idle and wasteful land use, reduce agricultural production and operational inputs, and enable farming households to obtain a relatively sustainable and stable income from land rent (Berge et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2020).

2.1.2. Theoretical analysis of the transfer-in land affecting poverty reduction

Duality economy theory suggests that because the amount of land is fixed, agricultural output tends to show diminishing marginal returns as the population base increases (Donato et al., 2008; Ren, 2015). Therefore, it is important to restructure land to improve the utilization of land resources, develop large-scale operations and transfer land to farmers with a higher level of agricultural production to achieve the marginal output levelling effect (Ruan and Xia, 2011; Shi et al., 2022). For farmland transfer households, the transfer of land has expanded the scale of land operations, promoted the development of agricultural mechanization, saved time and labor costs, and combined with the continuous input of agricultural technology and new varieties, has led to a significant increase in the land output rate, which in turn has led to a rapid increase in the production and operational income of farming households (Dong, 2018; Yang et al., 2020; Xiong and Wang, 2022).

On the basis of the above analysis, we propose hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 1. Transferring-in farmland can significantly reduce the vulnerability of farming households to poverty.

Hypothesis 2. Transferring-out farmland can significantly reduce the vulnerability of farming households to poverty.

2.2. Indirect effect analysis: labor allocation effects-household income effects

Farmland transfer can have labor allocation effects (Zhang, 2012). The essence of rural farmland transfer is that in the context of a multifactorial agricultural economy, the land rental market helps farmers with different land labor endowments to readjust their marginal products by transferring land use rights from those with lower land valuation to those who are more eager to increase their production value through a price equalization mechanism (Yu et al., 2014). In addition, farmland transfer helps facilitate the transfer of surplus rural labor from agriculture to other sectors (Zhang, 2012; Gao et al., 2020). This is an inherent mechanism for achieving higher farmers’ household income through farmland transfer.

Household income is the most direct and important factor in the poverty vulnerability of farmers (Banks et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2019). For the transfer-in farmer, owning more land can help him gain a certain degree of economies of scale and improve household operational income, but wage income decreases because of the decline in off-farm input time (Renwick et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018). After leasing in land, farmers need to invest more money in agricultural production, and has less money available for investment and financial management, which reduces his property income (Li et al., 2018). After transferring in the land, the transfer-in households may need to purchase more good seeds and agricultural machinery, and receive more subsidies for good seeds and agricultural machinery, which increases their transfer income (Fei et al., 2021). Farmers who transfer out of the land have increased resources invested in the non-farm sector, and their wage income rises while their farm operational income decreases (Ma et al., 2020). On the other hand, farmers who transfer out of the land can get a stable rental income, and at the same time, the capital needed for agricultural production is reduced after transferring out of the land, and this capital can be used for financial investment, which increases property income (Guo and Liu, 2021; Yu et al., 2022). Under the current agricultural subsidy policy, despite the transfer out of the original contracted land, most regions still pay direct food subsidies and comprehensive agricultural subsidies directly to the original contracted households, thus, the transfer out of land may not lead to a decrease in transferring income (Li et al., 2014). Based on this, we propose hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2. farmland transfer promotes labor reallocation, resulting in household income effects to reduce farmers’ poverty vulnerability.

Figure 1 shows the research framework of this paper.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Poverty vulnerability measurement

Poverty vulnerability, which connects risk shocks to the degree of household welfare, is often seen as unobservable, dynamic, and forward-looking, with a focus on poverty generation expectations (Eriksen and O’Brien, 2007; Bouzarovski, 2014). Poverty vulnerability is the probability that a household or individual will fall into poverty or fail to escape from poverty as a result of exposure to uncertainty risk shocks (Hardoy and Pandiella, 2009; Gillard et al., 2017). Poverty vulnerability is calculated as follows.

Where is an estimate of the probability of future poverty for farmer i, is the value of per capita household consumption, z is the delineated poverty line, is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution, and denote the expected value and variance of future household consumption estimated by the FLGS method, respectively. is an observable variable, referring to Wang et al. in their examination of poverty vulnerability by introducing household characteristics variables (including household income, household size, land assets, liabilities, agricultural machinery, etc.) and household head characteristics variables (including age, gender, education, etc.; Wang et al., 2022).

3.1.2. Did model

To examine the impact of farmland transfer on farmers’ poverty vulnerability, the basic model is set up as in Eq. (2):

where, is a dummy variable, with =1 indicating that household i transferred out or transferred in land or participated in the transfer at time t and =0 indicating not involved in farmland transfer. denotes the poverty vulnerability of farm household i in period t. X denotes a series of control variables affecting farmers’ income, such as gender, age, and education level in the individual characteristics of the household head, and household size, land assets, and agricultural machinery assets in the household characteristics. denotes individual fixed effects, denotes time fixed effects, and is a random error term. In the empirical analysis, the regression analysis was conducted separately for transferred-in and non-transferred households, transferred-out and non-transferred households, and participated in the transfer and non-transferred households.

3.1.3. Multi chain mediation effect model

Considering the interaction between labor allocation and income effects, i.e., the time-series characteristics of labor allocation for household income effects. With reference to existing studies (Wei et al., 2019; Han and Gao, 2020), the chain mediated effects model is designed to address this issue:

where, represents innovation and labor allocation effects, refers household income effects. And Eqs. 3–5 constitute multiple equation systems.

3.2. Variables and data

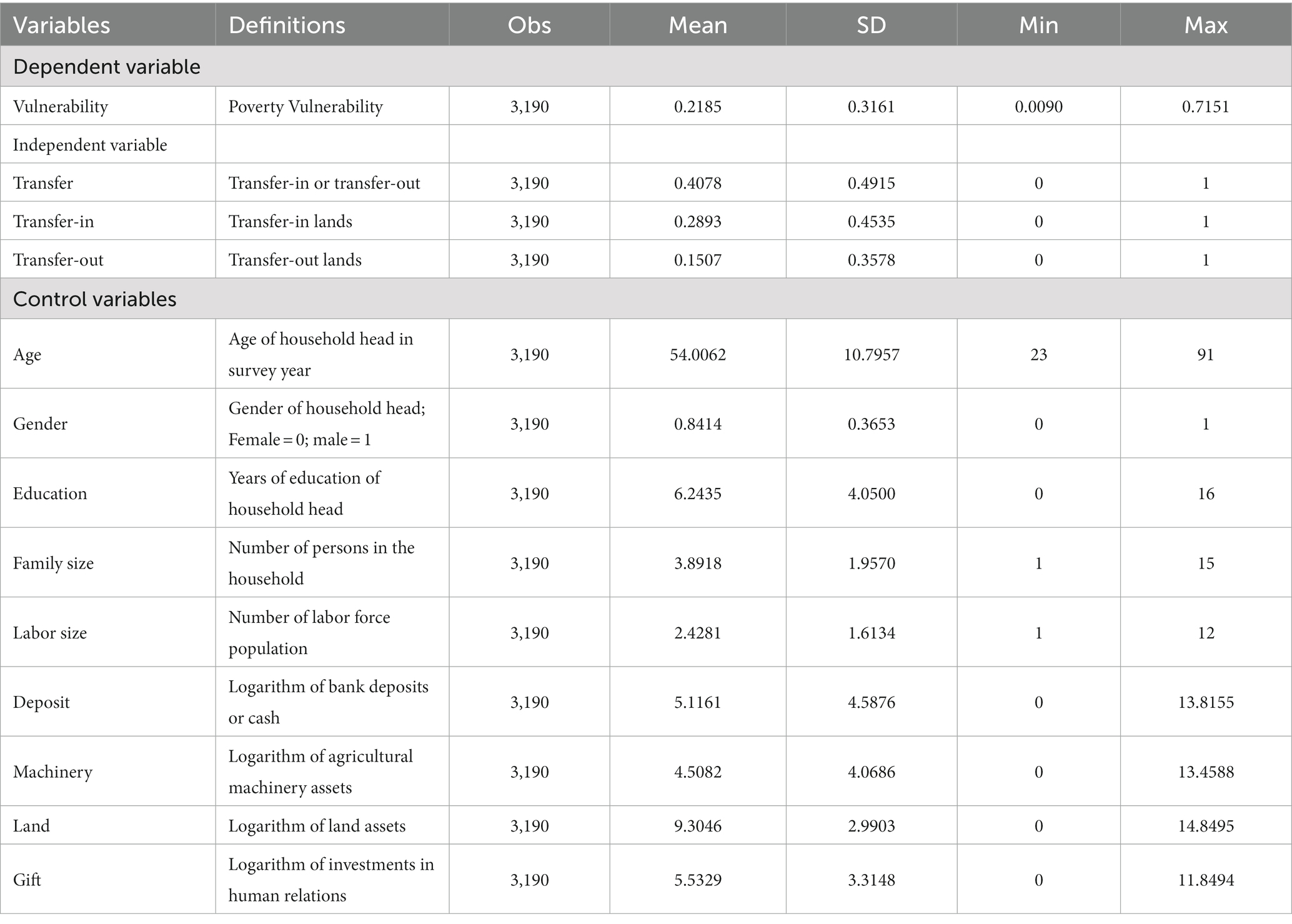

3.2.1. Dependent variable

To forecast household poverty vulnerability, this article uses household per capita consumption. One reason for using consumption to define poverty is that income is easily underestimated in micro-surveys, whereas consumption can better reflect the level of family welfare, and the other is that using income as an explanatory variable can easily lead to strong endogenous problems in the measurement model. Regarding the choice of the poverty line, there are primarily two standards of per capita daily consumption of US$1.9 and US$3.1 proposed by the World Bank in 2015 (Ceriani, 2018; Chen et al., 2021), which we convert into ¥2,800 and ¥4,570 per capita annual consumption based on China’s average purchasing power and CPI index. In the subsequent analysis, we focus on ¥4,570 as the poverty standard line.

3.2.2. Core explanatory variable

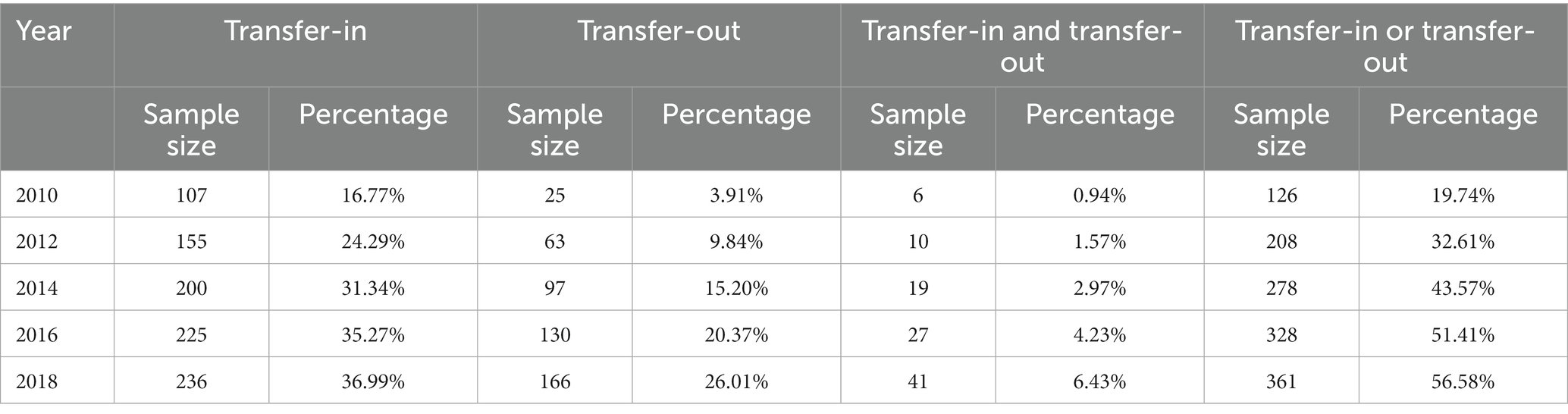

The core explanatory variables are whether to transfer out, whether to transfer in, and whether to transfer land. According to Table 1, 126 households participated in farmland transfer in 2010, accounting for 19. 74% of the total sample, with 25 households transferring out, accounting for 3. 91%, 107 households transferring in, accounting for 16. 77%, and 6 households both transferring in and out, accounting for 0. 94%. In the years that followed, the proportion of farmers who transferred land in rural China increased more than the proportion of transferred-in households, and as of 2018, the number of transferred-out households increased by 141, accounting for 26.01%, while the number of transferred-in households was 236, accounting for 36.99%, and the number of farmers who transferred land was 361, accounting for 56.68%. At the same time, the number of farmers who both transferred in and transferred out increased year by year, indicating that more and more farmers are replacing their land in order to realize centralized production and management, and farmers’ awareness of production management has increased.

3.2.3. Control variables

Based on reference to other literature (Yu et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2020; Fei et al., 2021), we selected household head characteristics variables (gender of household head, age of household head, education level of household head) and household characteristics variables (household size, value of agricultural machinery, cash savings, etc.) that may have an impact on the poverty vulnerability of farm households as control variables.

The data in this paper are from the 2010–2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 24-province household survey data. Firstly, the data of non-rural households were excluded from the overall data; secondly, only the data of farm households that were all tracked in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018 were retained; finally, the data of farm households with serious deficiencies were excluded, and finally the data of 638 farm households remained, with a total of 3,190 observations. Descriptive results for the relevance variables are shown in Table 2.

4. Empirical results

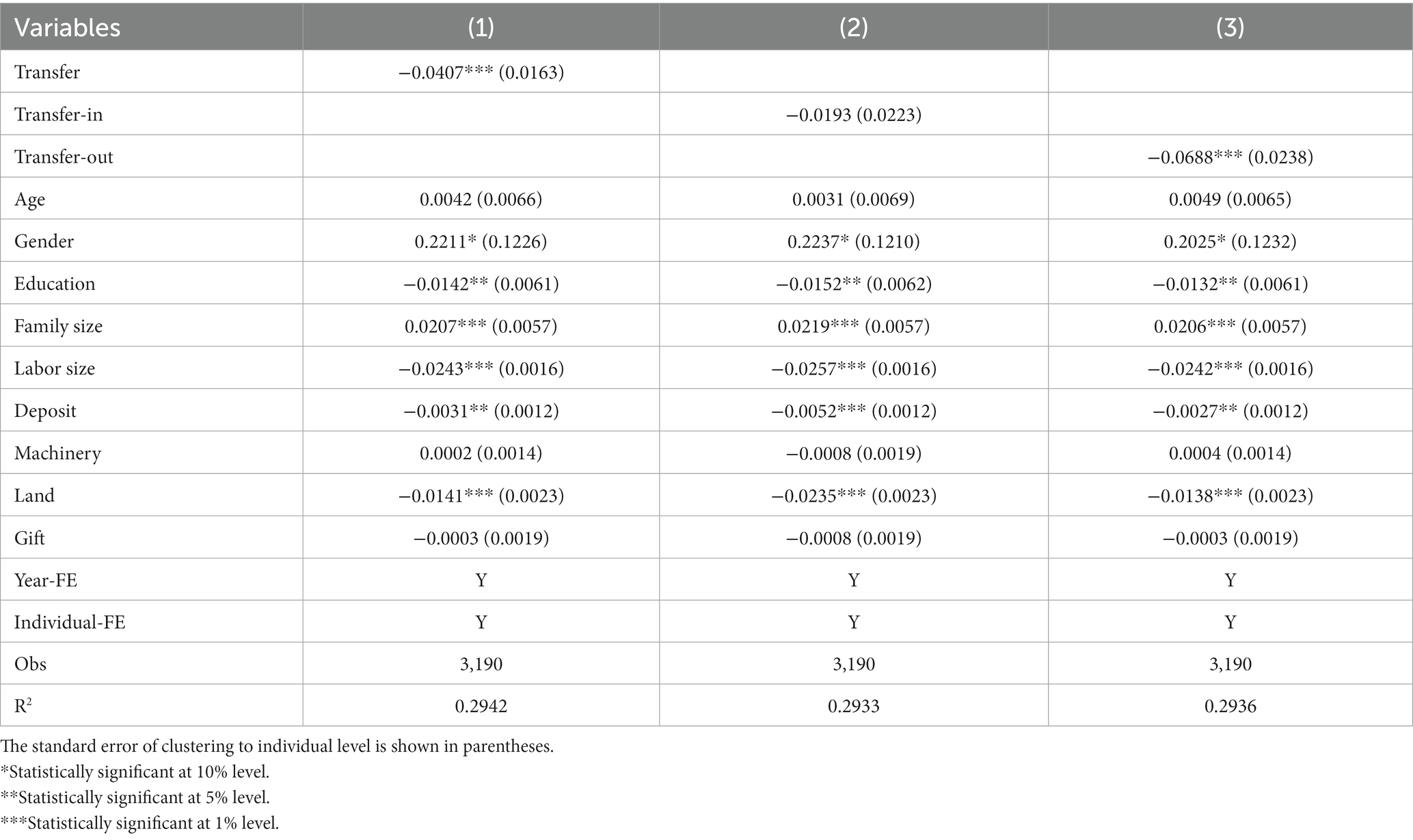

4.1. Baseline regression results

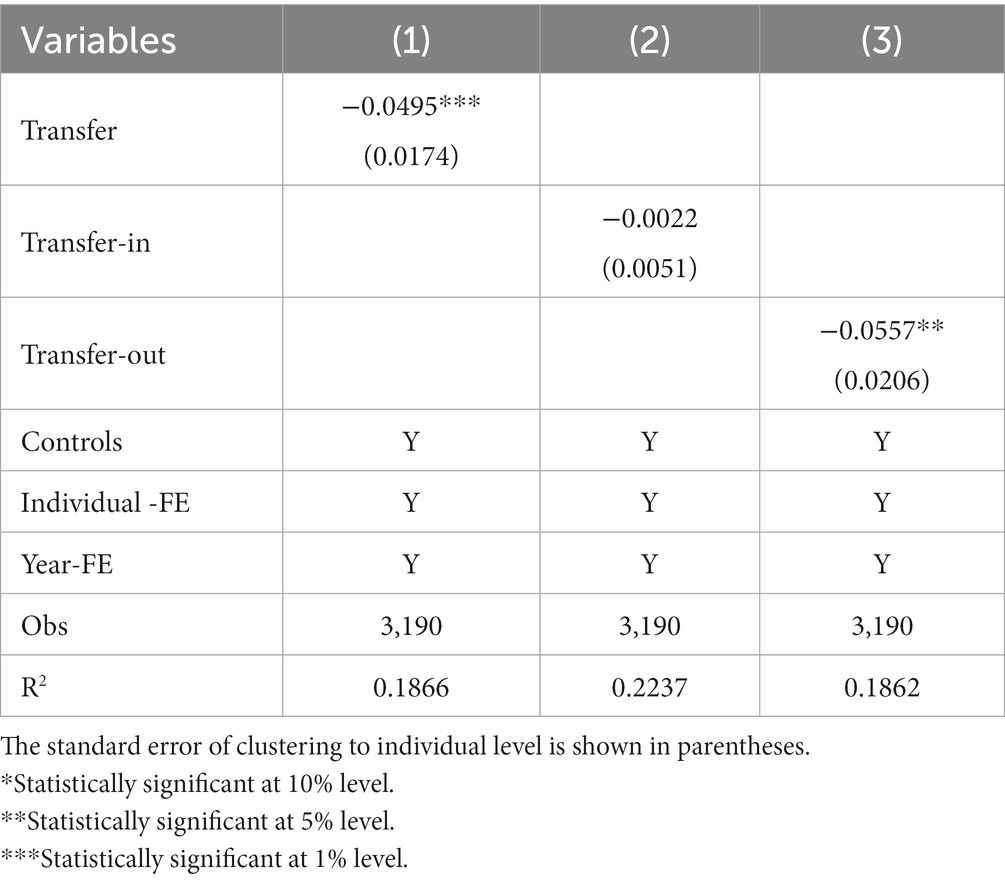

As shown in Table 3, column (1) reports the effect of participation in farmland transfer on farm household poverty vulnerability. Furthermore, to validate the effects of different types of farmland transfer on farm household poverty vulnerability, columns (2) and (3) report the effect of farmland transfer in and farmland transfer out on farm household poverty vulnerability, respectively.

The results show that the coefficient of transfer is −0.0407 and significant at the 1% statistical level, which indicates that farmland transfer can reduce farmers’ poverty vulnerability. This conclusion is consistent with existing research findings. However, further analysis reveals that the coefficient of transfer-out is −0.0688 and significant at the 1% statistical level; but the coefficient of transfer-in is −0.0193 and insignificant. Thus, farmland transfer does reduce the vulnerability of farm households to poverty, but mainly in terms of its poverty-reducing effect on the transfer-in farm households and not in terms of its poverty-reducing effect on the transfer-out farm households.

In addition, we calculated the reducing effect size. During 2010–2018, the average poverty vulnerability of farmers involved in transfers-out farmland are 0.1741. Through land transfers out, the poverty vulnerability of this group of farming households was significantly reduced by 0.0688. As a result, the transfer-out farmland reduces poverty vulnerability by about 39.52%.

4.2. Parallel trend analysis and policy dynamic effects

In this section, we use event analysis to examine parallel trends and to adjust the dynamic effects of farmland transfer (including transfer-in and transfer-out). The event analysis model is shown in Eq. (6):

Based on Eq. (1), we construct a new variable , which represents the event impact of farmland transfer (including transfer-in and transfer-out). In the model, the year of farmland transfer is taken as the base year. A graphical technique is used to investigate parallel trends and dynamic impacts.

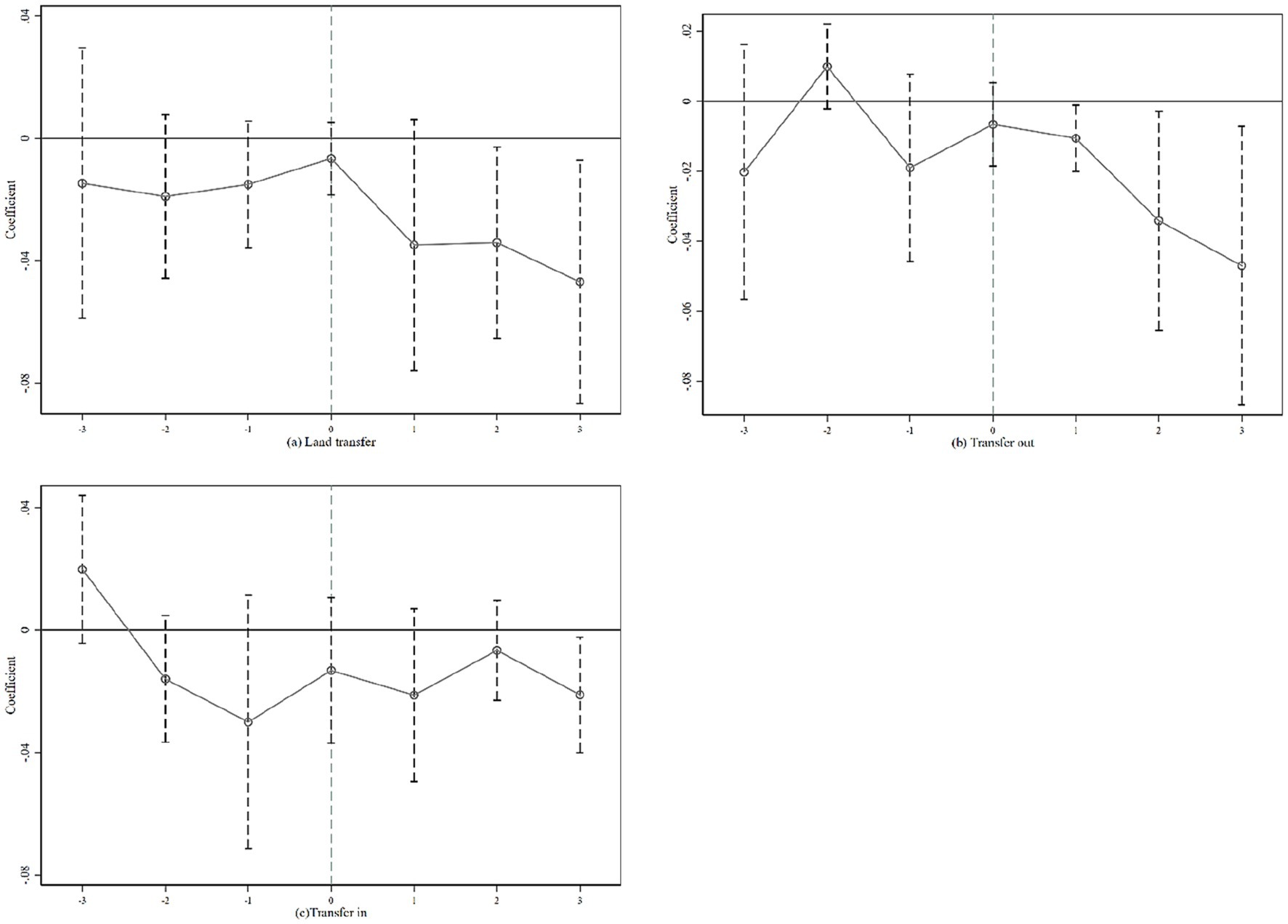

Figure 2 reports the variation of the coefficient of variable in Eq. (6) over time (confidence interval 95%). Before the point of farmland transfer, the change of poverty vulnerability can cannot be significantly different from 0. Therefore, this study satisfies the parallel trend hypothesis.

Figure 2. Time dynamic effect analysis of farmland transfer (including transfer-in and transfer-out).

Also, analysis of the dynamic effects of the policy shows that the vulnerability of farm households to poverty has been significantly reduced for three consecutive years after the transferring out land, and, the reduction effect is increasing every year. However, the transferring in land did not result in a significant reduction in the vulnerability of farm households to poverty. Therefore, we need to use the DID model for a more in-depth analysis.

4.3. Robustness tests

4.3.1. Changes to the poverty threshold

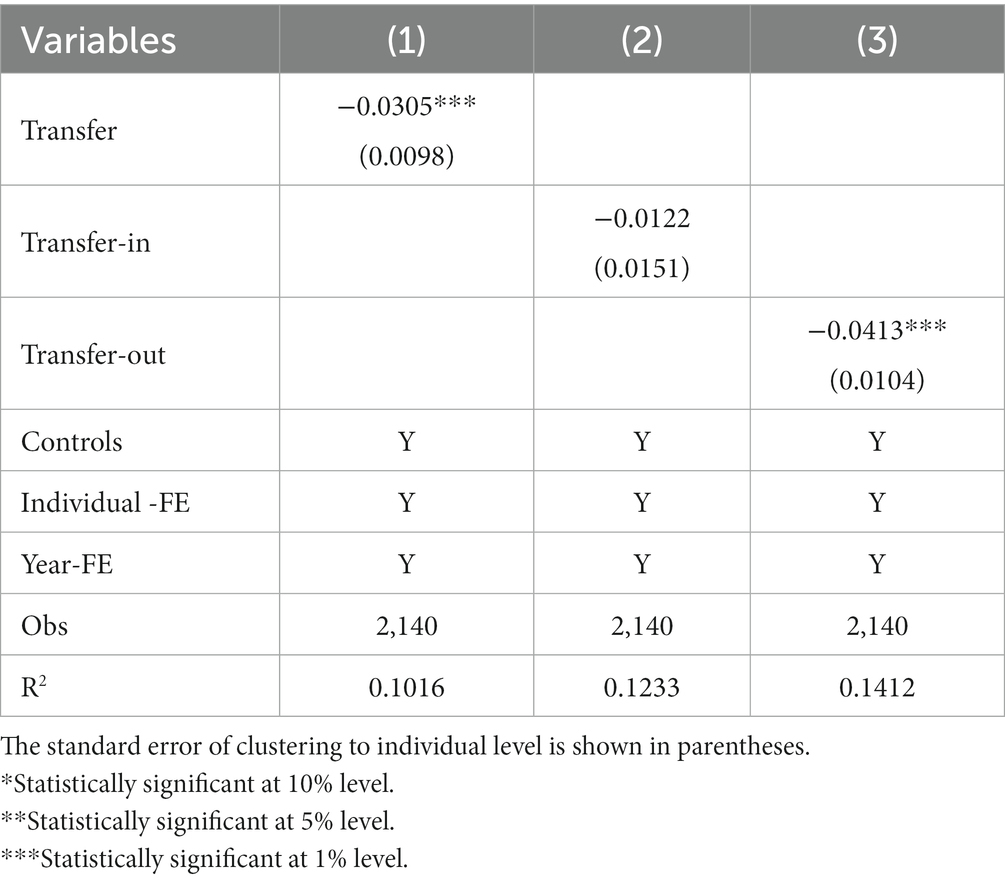

In the above analysis, we have mainly used an average daily consumption level of US$3.1 as the poverty threshold. In this section, we further conduct robustness tests using an average daily consumption level of US$1.9 as the poverty criterion line, and the results are shown in Table 4. There are no significant changes in the sign and significance of the coefficients on all policy variables compared to the baseline model, thus arguing the robustness of the result.

4.3.2. Use the PSM-DID method

In an ideal quasi-natural experiment, the treatment and control groups’ samples are drawn at random (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2016). However, when farmers decide whether to participate in farmland transfer, each individual’s strengths in various areas must be considered, including the economy and the environment. This could result in sample selection bias and significant differences between the treatment and control groups prior to policy implementation (Rassen et al., 2012). A propensity score matching (PSM) technique is employed in this research to eliminate sample selection bias by matching treatment and control group samples one-to-one. The PSM estimation method is used to test the robustness of the Logit regression results. The logit model is used to calculate the conditional probability fitting value of the sample farmers’ farmland transfer, which is the propensity score (PS).

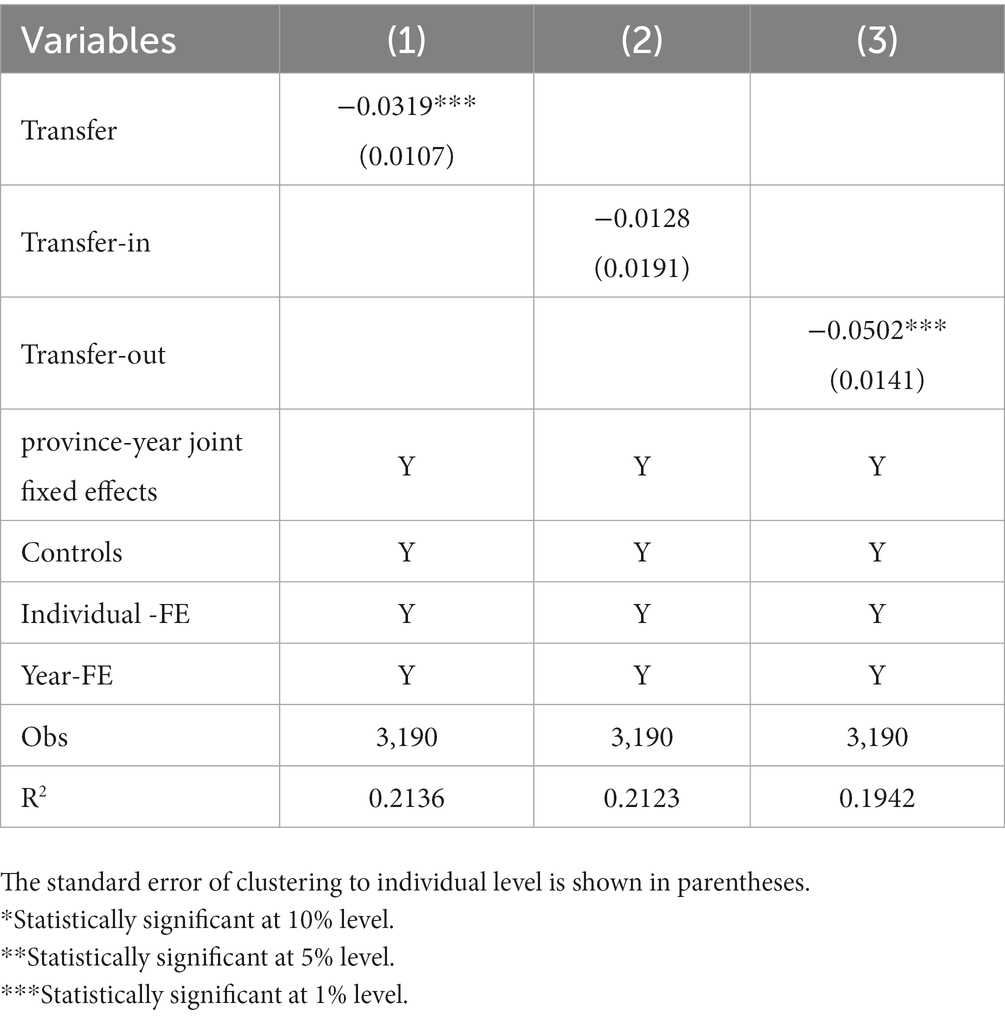

Among them, is the number of samples of farmland transfer households, is the sample set of the disposal group (participating in farmland transfer), is the sample set of the control group (not involved in farmland transfer), is the observed value of the sample of the disposal group, and is the sample of the control group The observations of j, is the common support domain set, is the matching weight, and ATT is the average disposition effect. The main method is to match the samples of the control group and the disposal group according to the propensity value to ensure that there is no significant difference in their main characteristics; then use the control group to estimate the counterfactual state of the treatment group (that is, not participating in the transfer), and calculate the poverty caused by farmland transfer. Net treatment effect of vulnerability ATT. Table 5 displays the PSM-DID regression results after excluding samples that were not successfully matched. Specifically, there is no change in the sign or significance of the all land-transfer explanatory variables, which suggests that the findings of this paper are robust.

4.3.3. Add the province-year joint fixed effects

We controlled for time fixed effects and individual fixed effects in the preceding analysis. However, because policies in China are generally implemented at the provincial level, and some provinces may also implement some farmland transfer policies, the effect of different provinces over time is difficult to capture by the aforementioned time-fixed and individual-fixed effects (Zhou et al., 2020), this paper further introduces joint province-time fixed effects as a way to control for the land-transfer effects at the provincial level. Robustness tests are conducted on the previous findings. The regression results after introducing the joint province-time fixed effects are shown in Table 6. The primary explanatory variable transfer (including transfer-in and transfer-out) not change considerably after correcting for the province-time impact, supporting the earlier conclusion.

5. Further analysis

5.1. Mechanism analysis: labor allocation effects

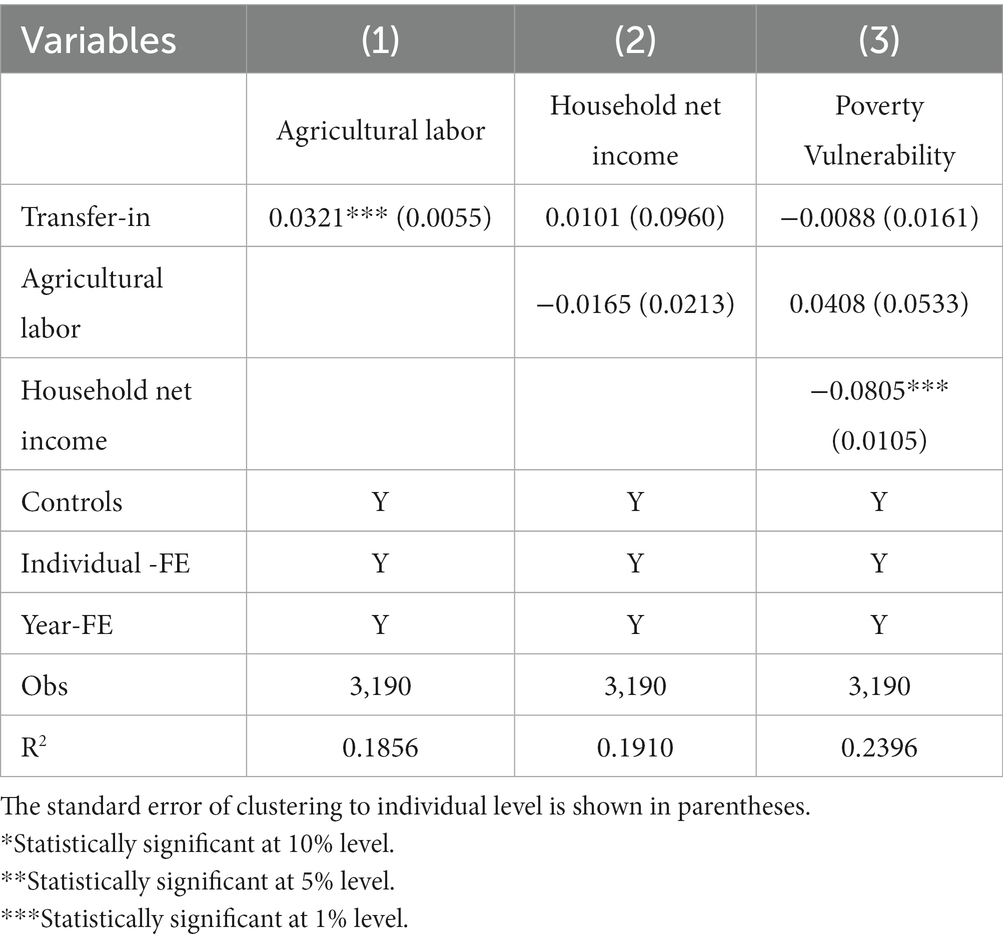

In this section, we try to find the potential mechanisms by which farmland transfer (including transfer-in and transfer-out) work. For farmland transfer in, we introduce two new variables, the number of laborers participating in agricultural production and the net household income per capita. As shown in Table 7, the column (1) shows that the coefficient of transfer-in is 0.0321 and significant, which indicates that farmland transfer in requires increased inputs of labor for agricultural production. However, the increase in labor inputs for agricultural production has not significantly raise net household income per capita, as reported in column (2). In column 3, this conclusion is further verified. The coefficient of transfer-in is 0.0088 and insignificant, which indicates that transfer in of land does not significantly reduce the poverty vulnerability of farm households.

For farmland transfer out, we also introduce two new variables, the number of outworking labor force and the net household income per capita. As shown in Table 8, the column (1) shows that the coefficient of transfer-in is 0.0515 and significant, which indicates that the transfer out of land will lead to more rural labor going out to work. It is worth noting that an increase in the number of migrant workers can significantly raise the income levels of farming households, as reported in column (2). In column 3, this conclusion is further verified. The coefficient of transfer-out is 0.0579 and significant, which indicates that transfer out of land can significantly reduce the poverty vulnerability of farm households. Therefore, the chain mediation effect is expressed as “transfer out of land→ increasing the outworking workforce→ increasing net household income → reducing poverty vulnerability.”

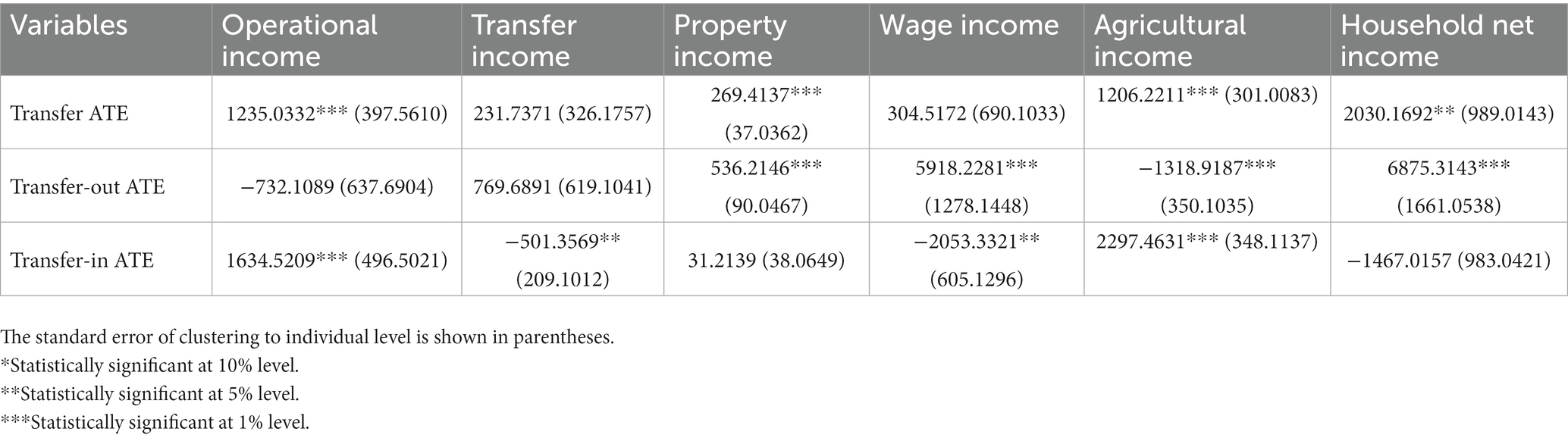

5.2. Mechanism analysis: analysis of the contribution of farmland transfer to household income

Based on the above analysis, it is clear that transfers out of land can significantly increase the net household income of farmers and thus reduce poverty vulnerability, but transfers in of land cannot do so. In this section, we classify farm-household income into five categories: operational income, transfer income, property income, wage income and agricultural income. Among them, operational income includes income from agricultural production and income from non-agricultural production. Transfer income mainly includes government subsidies to farmers, etc. Property income refers to income earned from financial investments. Wage income is mainly the income of farmers working outside the home. Agricultural income represents the income from agricultural production. With reference to existing studies, we use the treatment group average treatment effect (ATT) obtained from the propensity score matching method to demonstrate the extent to which farmland transfer affects different types of income, with a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching, set up in line with the PSM-DID model above.

As shown in Table 9, the net household income of farmers who transferred their land increased by RMB 2030 compared to those who did not, of which operational income increased by RMB1235, an increase of 60.83%, while wage income did not increase significantly. The net household income of farmers who have transferred out their land increased by RMB6875, about 86% of which came from an increase in wage income, with other income contributing less to the change in net household income. For farmers who transfer out of their land, the probability of the household labor force engaging in non-farm operational increases after the farmland transfer, so the decline in household operational income is less than the decline in income from agricultural production. However, for farmers who transferred in their land, the decrease in wage income by RMB2053 was much higher than the increase in operational income, so the net household income of farmers who transferred their land fell instead compared to farmers who did not transfer their land. In conclusion, the results show that farmland transfer does have a significant income growth effect, but the increase in income is mainly due to the significant increase in the income of the farmers who transferred out of the land; as the agricultural production and operational income of the farmers who transferred into the land did not increase significantly, the poverty reduction effect of farmland transfer on the farmers who transferred into the land was not significant.

6. Discussion

Existing research is divided on whether farmland transfers may alleviate farmer poverty, particularly future poor. We contend that these disparities are the result of neglecting the diverse impact of farmland transfers on transfer-out and transfer-in farmers, as well as varied sources of income such as wage income and agricultural production income. The paper contends that these disparities in empirical data are attributable to a failure to account for the varied impact of farmland transfer. Misleading results may be obtained when disparities in the impact of farmland transfers on transfer-out and transfer-in farmers, as well as on different sources of income, such as wage income and agricultural income, are ignored.

From a poverty vulnerability perspective, this paper analyses the impact of farmland transfer on the future poverty of transferred-in and transferred-out farmers, based on inter-period data from 638 farming households in China. It is found that farmland transfer does reduce poverty vulnerability in general, but the poverty reduction effect is mainly due to the fact that farmland transfer significantly reduces the poverty vulnerability of the transferred-out farmers.

Further analysis shows that the difference in the impact of farmland transfer on poverty vulnerability is mainly due to the significant labor allocation effect of farmland transfer. In other words, farmers who transfer out of the land put more labor into non-farm production (e.g., increased probability of going out to work and starting a business), while farmers who transfer into the land put more labor into agricultural production. However, an analysis of the contribution of farmland transfer reveals that for farmers who transferred their land out, the increase in wage income was much higher than the decrease in business income, and the level of net household income rose significantly, with nearly 86% of this increase coming from wage income. In contrast, for the farmers whose land was transferred in, the income improvement effect of agricultural operations and production was weaker, resulting instead in no significant improvement in the household income of the nongame households whose land was transferred in.

Generally speaking, farmland transfer has an impact on the allocation of labor resources for both transfer-in and transfer-out farmers, and promotes the division of labor, but the improvement of labor productivity depends not only on the division of labor, but also on the improvement of specialized production (Wang and Zhang, 2017; Li et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2022). However, China’s current farmland transfer policy focuses more on encouraging farmers with advantages in agricultural production to transfer into the land for large-scale operation, and seldom involves technical training to improve specialized production (Long et al., 2007, 2012; Chen et al., 2014). The labor force of farmers transferred out of land is mainly engaged in unskilled work, and the level of specialization can easily be improved, while large-scale agricultural operations require relevant professional management knowledge to improve the efficiency of production and operation (Ho and Lin, 2003; Mullan et al., 2011; Long, 2014). According to data from the China Household Finance Survey 2015, for example, less than 15% of land-transferred farmers have ever received agricultural technology instruction, indicating that the current large-scale agricultural operation of transfer-in farmers in China is more reflected in the expansion of production scale, but lacks corresponding management and technology, and does not improve the level of specialized production (Yang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). Our findings offer a fresh look at future poverty and the long-term viability of poverty-reduction initiatives.

However, it is important to note that the research methodology and thinking of this paper still needs to be refined. Firstly, this study focuses on rural China and does not consider samples from other countries. Therefore, how farmland transfer affects the poverty vulnerability of farm households needs to be more fully verified in the future. Secondly, in terms of cause analysis, this study is mainly based on the heterogeneity of farmland transfer types and income sources, and may have overlooked other potential mechanisms, and more empirical studies are needed to further complement and improve the relevant impact mechanisms. Thirdly, in the robustness test, we used a range of methods such as PSM-DID to mitigate endogeneity issues, but a better approach would be to test using instrumental variables, which is a difficult but meaningful exercise for future research.

7. Conclusion

Based on data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2010 to 2018, this research explores the influence of farmland transfer on future poverty. The paper first estimates poverty vulnerability using the vulnerability theory of expected poverty, and then constructs a poverty vulnerability model using the DID method to quantify the likelihood of farm households falling into poverty in the future and reassess the poverty reduction effect of farmland transfer with a forward-looking perspective. The following basic conclusions are presented.

(1) Farmland transfer does reduce the poverty vulnerability of farming households in general, but the poverty reduction effect is mainly due to the fact that farmland transfer significantly reduces the poverty vulnerability of farmers who transfer out of the land and has no significant effect on the poverty vulnerability of farmers who transfer into the land. Specifically, the poverty vulnerability of farmers who transfer out of the land is reduced by an average of 39.52%.

(2) The difference in the poverty reduction effect of farmland transfer is due to the fact that farmland transfer produces a significant improvement in the allocation of labor, that is, farmers who transfer out of the land put more labor into non-agricultural production (e.g., increased probability of working outside the home and starting a business), which increases net household income and reduces poverty vulnerability, while farmers who transfer in of the land put more labor into agricultural production, which does not increase net household income and does not reduce poverty vulnerability.

(3) The contribution of farmland transfer to the household income of different types of farmers differs. For farmers who transfer out of the land, the increase in wage income was much higher than the decrease in operational income, and the level of net household income of farmers rose significantly, of which 86% of the increase came from wage income. However, for the farmers who transfer in of the land, agricultural production income and operational income grew less, which resulted in no significant improvement in the net household income of the farmers who transfer in of the land.

The research reveals that the poverty-reducing impacts of farmland transfer need to be enhanced further, and that farmland transfer in particular does not considerably raise farm households’ net household income. The following policy recommendations are offered based on the preceding study. First, China should improve agricultural technology training, raise farmers’ management awareness, take advantage of large-scale and intense production, boost agricultural production efficiency, and increase the household income of farmers who has been transferred into land (Tian et al., 2022; Zhao, 2022). At the same time, for farmers who have not participated in farmland transfer, the government should guide them according to their household resource endowments so that they can participate in the farmland transfer process, and increase their net household income. Second, China’s agricultural support and protection policies should be improved. Using the current subsidy policy for purchasing agricultural machinery as an example, only farmers who purchase large-scale agricultural machinery can obtain this portion of the transfer payment income, but most small and medium-sized transfer-in farmers are unable to purchase large-scale agricultural machinery and thus cannot benefit from it which may result in the phenomenon of the poor getting poorer and the rich getting richer, leading to the further expansion of the inequity (Deng et al., 2022; Wei, 2022). As a result, agricultural subsidy policy standards must be adjusted. Farmers who have transferred into the small to medium sized land may benefit as well. Finally, the above analysis finds that farmland transfer mainly contributes to the growth of net household income through wage income and property income, but the contribution of farmland transfer to property income is still extremely low, so the government needs to further improve the farmland transfer market to reveal the asset value of land resources, increase farmers’ property income, and enhance farmers’ resilience to future poverty. In order to achieve this goal, China should develop a clear and appropriate national framework for transferring land management rights and strengthen the process for transferring rural land management rights.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: conceptualization. JC and MY: methodology, formal analysis, resources, writing—original draft preparation, and visualization. MY: software, validation, and writing—review and editing. JC and ZW: investigation. MY, ZZ, and JZ: data curation and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant/Award Number: 17XTQ011) and the MOE Project of Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences in Universities of China (Grant/Award Number: 16JJD790063).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adger, W. N., and Kelly, P. M. (1999). Change, social vulnerability to climate change and the architecture of entitlements. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 4, 253–266. doi: 10.1023/A:1009601904210

Andreas, J., and Zhan, S. H. (2016). Hukou and land: market reform and rural displacement in China. J. Peasant Stud. 43, 798–827. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1078317

Banks, L. M., Kuper, H., and Polack, S. (2017). Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 12:e0189996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189996

Berge, E., Kambewa, D., Munthali, A., and Wiig, H. (2014). Lineage and land reforms in Malawi: do matrilineal and patrilineal landholding systems represent a problem for land reforms in Malawi? Land Use Policy 41, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.05.003

Besley, T. (1995). Property-rights and investment incentives - theory and evidence from Ghana. J. Polit. Econ. 103, 903–937. doi: 10.1086/262008

Bouzarovski, S. (2014). Energy poverty in the European Union: landscapes of vulnerability. Wiley Interdis. Rev. Energy Environ. 3, 276–289. doi: 10.1002/wene.89

Cai, X. Q., Lu, Y., Wu, M., and Yu, L. (2016). Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. J. Dev. Econ. 123, 73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.08.003

Ceriani, L. (2018). “Vulnerability to poverty: empirical findings” in Handbook of research on economic and social well-being. ed. C. Dambrosio (Handbook of Research on Economic and social), 284–299.

Chen, J. D., Rong, S. S., and Song, M. L. (2021). Poverty vulnerability and poverty causes in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 153, 65–91. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02481-x

Chen, R. S., Ye, C., Cai, Y., Xing, X., and Chen, Q. (2014). The impact of rural out-migration on land use transition in China: past, present and trend. Land Use Policy 40, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.10.003

Cheynier, V., Comte, G., Davies, K. M., Lattanzio, V., and Martens, S. (2013). Plant phenolics: recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 72, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.009

Christiaensen, L., Demery, L., and Kuhl, J. J. (2011). The (evolving) role of agriculture in poverty reduction—an empirical perspective. J. Dev. Econ. 96, 239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.10.006

Davies, M., Guenther, B., Leavy, J., Mitchell, T., and Tanner, T. (2009). Climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction and social protection: complementary roles in agriculture and rural growth? IDS Work. Papers 2009, 01–37. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-0209.2009.00320_2.x

Deininger, K., and Jin, S. Q. (2005). The potential of land rental markets in the process of economic development: evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 78, 241–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.08.002

Deng, X., Xu, D., Zeng, M., and Qi, Y. (2019). Does early-life famine experience impact rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 81, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.042

Deng, X., Zhang, M., and Wan, C. L. (2022). The impact of rural land right on Farmers’ income in underdeveloped areas: evidence from Micro-survey data in Yunnan Province, China. Land 11:1780. doi: 10.3390/land11101780

Dercon, S., and Christiaensen, L. (2011). Consumption risk, technology adoption and poverty traps: evidence from Ethiopia. J. Dev. Econ. 96, 159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.08.003

Dercon, S., and Krishnan, P. (2000). Vulnerability, seasonality and poverty in Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 36, 25–53. doi: 10.1080/00220380008422653

Dev, S. (2017). Poverty and employment: roles of agriculture and non-agriculture. Indian J. Labour Econ. 60, 57–80. doi: 10.1007/s41027-017-0091-2

Devereux, S. J. (2001). Livelihood insecurity and social protection: a re-emerging issue in rural development. Dev. Policy Rev. 19, 507–519. doi: 10.1111/1467-7679.00148

Donato, M. B., Maugeri, A., Milasi, M., and Vitanza, C. (2008). Duality theory for a dynamic Walrasian pure exchange economy. Pac. J. Optimiz. 4, 537–547.

Dong, X. (2018). Reform of China’s housing and land systems: the development process and outlook of the real estate industry in China. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 5, 79–93.

Eriksen, S. H., and O’Brien, K. (2007). Vulnerability, poverty and the need for sustainable adaptation measures. Clim. Pol. 7, 337–352. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2007.9685660

Fei, R. L., Lin, Z. Y., and Chunga, J. (2021). How land transfer affects agricultural land use efficiency: evidence from China’s agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 103:105300. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105300

Feng, L., Bao, H. X. H., and Jiang, Y. (2014). Land reallocation reform in rural China: a behavioral economics perspective. Land Use Policy 41, 246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.05.006

Furubotn, E. G. (1988). Codetermination and the modern theory of the firm - a property-rights analysis. J. Bus. 61, 165–181. doi: 10.1086/296426

Gao, J. L., Liu, Y. S., and Chen, J. L. (2020). China’s initiatives towards rural land system reform. Land Use Policy 94:104567. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104567

Garmezy, N. (1991). Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. Am. Behav. Sci. 34, 416–430. doi: 10.1177/0002764291034004003

Gillard, R., Snell, C., and Bevan, M. (2017). Advancing an energy justice perspective of fuel poverty: household vulnerability and domestic retrofit policy in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 29, 53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.012

Guo, Y. Z., and Liu, Y. S. (2021). Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 105:105418. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105418

Han, C., and Gao, S. (2020). A chain multiple mediation model linking strategic, management, and technological innovations to firm competitiveness. Rev. Brasil. Gestao Negocios 21, 879–905. doi: 10.7819/rbgn.v21i5.4030

Hardoy, J., and Pandiella, G. (2009). Urban poverty and vulnerability to climate change in Latin America. Environ. Urban. 21, 203–224. doi: 10.1177/0956247809103019

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., O’Cleirigh, C., Grasso, C., Mayer, K., Safren, S., and Bradford, J. (2012). Effect of same-sex marriage Laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: a quasi-natural experiment. Am. J. Public Health 102, 285–291. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300382

He, Q., Deng, X., Li, C., Kong, F., and Qi, Y. (2022). Does land transfer improve Farmers’ quality of life? Evidence from rural China. Land 11:15. doi: 10.3390/land11010015

Ho, S. P. S., and Lin, G. C. S. (2003). Emerging land markets in rural and urban China: policies and practices. China Q. 175, 681–707. doi: 10.1017/S0305741003000407

Huang, K., Deng, X., Liu, Y., Yong, Z., and Xu, D. (2020). Does off-farm migration of female laborers inhibit land transfer? Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Land 9:14. doi: 10.3390/land9010014

Kong, X. S., Liu, Y., Jiang, P., Tian, Y., and Zou, Y. (2018). A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 78, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.046

Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., and Hadley, D. (2020). Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Soc. Indic. Res. 149, 613–639. doi: 10.1007/s11205-019-02263-0

Lagakos, D., and Waugh, M. E. (2013). Selection, agriculture, and cross-country productivity differences. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 948–980. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.2.948

Li, H., Chen, K., Yan, L., Yu, L., and Zhu, Y. (2023). Citizenization of rural migrants in China’s new urbanization: the roles of hukou system reform and rural land marketization. Cities 132:103968. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2022.103968

Li, C. Y., Jiao, Y., Sun, T., and Liu, A. (2021). Alleviating multi-dimensional poverty through land transfer: evidence from poverty-stricken villages in China. China Econ. Rev. 69:101670. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101670

Li, Y. R., Liu, Y., Long, H., and Cui, W. (2014). Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 39, 188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.02.016

Li, Y. H., Wu, W. H., and Liu, Y. S. (2018). Land consolidation for rural sustainability in China: practical reflections and policy implications. Land Use Policy 74, 137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.003

Li, A., Wu, J., Zhang, X., Xue, J., Liu, Z., Han, X., et al. (2018). China’s new rural “separating three property rights” land reform results in grassland degradation: evidence from Inner Mongolia. Land Use Policy 71, 170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.052

Li, L. C., Zhang, L., Xia, J., Gippel, C. J., Wang, R., and Zeng, S. (2015). Implications of modelled climate and land cover changes on runoff in the middle route of the south to north water transfer project in China. Water Resour. Manag. 29, 2563–2579. doi: 10.1007/s11269-015-0957-3

Liu, Y. S., Li, J. T., and Yang, Y. Y. (2018). Strategic adjustment of land use policy under the economic transformation. Land Use Policy 74, 5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.005

Liu, Z. M., Rommel, J., Feng, S., and Hanisch, M. (2017). Can land transfer through land cooperatives foster off-farm employment in China? China Econ. Rev. 45, 35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2017.06.002

Long, H. L. (2014). Land consolidation: an indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 24, 211–225. doi: 10.1007/s11442-014-1083-5

Long, H. L., Heilig, G. K., Li, X., and Zhang, M. (2007). Socio-economic development and land-use change: analysis of rural housing land transition in the transect of the Yangtse River, China. Land Use Policy 24, 141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2005.11.003

Long, H. L., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Woods, M., and Zou, J. (2012). Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 29, 11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.04.003

Lu, X. H., Jiang, X., and Gong, M. Q. (2020). How land transfer marketization influence on green total factor productivity from the approach of industrial structure? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 95:104610. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104610

Ma, B., Cai, Z., Zheng, J., and Wen, Y. (2019). Conservation, ecotourism, poverty, and income inequality - a case study of nature reserves in Qinling, China. World Dev. 115, 236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.11.017

Ma, L., Long, H., Tu, S., Zhang, Y., and Zheng, Y. (2020). Farmland transition in China and its policy implications. Land Use Policy 92:104470. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104470

Mayhew, A. (1985). Dangers in using the idea of property-rights - modern property-rights theory and the neoclassical trap. J. Econ. Issues 19, 959–966. doi: 10.1080/00213624.1985.11504447

Middlemiss, L., and Gillard, R. (2015). Fuel poverty from the bottom-up: Characterising household energy vulnerability through the lived experience of the fuel poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 6, 146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.02.001

Moser, C. O. N. (1998). The asset vulnerability framework: reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Dev. 26, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10015-8

Mullan, K., Grosjean, P., and Kontoleon, A. (2011). Land tenure arrangements and rural-urban migration in China. World Dev. 39, 123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.08.009

O’Laughlin, B., Bernstein, H., Cousins, B., and Peters, P. E. (2013). Introduction: agrarian change, rural poverty and land reform in South Africa since 1994. J. Agrar. Chang. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/joac.12010

Rassen, J. A., Shelat, A. A., Myers, J., Glynn, R. J., Rothman, K. J., and Schneeweiss, S. (2012). One-to-many propensity score matching in cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 21, 69–80. doi: 10.1002/pds.3263

Ravallion, M., and VanDeWalle, D. (2008). Land in transition: reform and poverty in rural Vietnam. Land in transition: reform and poverty in rural. Vietnam, 1–205. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-7274-6

Ren, J. (2015). “The comparative research on agricultural Sector’s characteristics of duality economy transition between China and Japan.” in International Conference on Social Science, Education Management and Sports Education (SSEMSE). Beijing, Peoples R China.

Renwick, A., Jansson, T., Verburg, P. H., Revoredo-Giha, C., Britz, W., Gocht, A., et al. (2013). Policy reform and agricultural land abandonment in the EU. Land Use Policy 30, 446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.04.005

Ruan, W. B., and Xia, H. (2011). “On China’s rural land system reform on the viewpoint of urbanization.” in International Conference on Applied Social Science. 2011. Changsha, Peoples R China.

Shi, X. J., Gao, X. W., and Fang, S. L. (2022). Land system reform in rural China: path and mechanism. Land 11:1241. doi: 10.3390/land11081241

Tan, S., Zhong, Y., Yang, F., and Gong, X. (2021). The impact of Nanshan National Park concession policy on farmers’ income in China. Glob. Eco. Cons. 31:e01804. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01804

Tian, Y. Y., Tsendbazar, N. E., van Leeuwen, E., and Herold, M. (2022). Mapping urban-rural differences in the worldwide achievement of sustainable development goals: land-energy-air nexus. Environ. Res. Lett. 17:114012. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac991b

Wang, H., Wang, L., Su, F., and Tao, R. (2012). Rural residential properties in China: land use patterns, efficiency and prospects for reform. Habitat Int. 36, 201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.06.004

Wang, Q. X., and Zhang, X. L. (2017). Three rights separation: China’s proposed rural land rights reform and four types of local trials. Land Use Policy 63, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.027

Wang, Z., Yang, M., Zhang, Z., Li, Y., and Wen, C. (2022). The impact of land transfer on vulnerability as expected poverty in the perspective of farm household heterogeneity: an empirical study based on 4608 farm households in China. Land 11:1995. doi: 10.3390/land11111995

Wei, N. (2022). Decreasing land use and increasing information infrastructure: big data analytics driven integrated online learning framework in rural education. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1025646. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1025646

Wei, X., Liu, X., and Sha, J. (2019). How does the entrepreneurship education influence the students’ innovation? Testing on the multiple mediation model. Front. Psychol. 10:1557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01557

Wilmsen, B. (2016). Expanding capitalism in rural China through land acquisition and land reforms. J. Contemp. Chin. 25, 701–717. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2016.1160504

Xiong, S. X., and Wang, H. (2022). The logic of urban land system reform in China-a policy analysis framework based on punctuated-equilibrium theory. Land 11:1130. doi: 10.3390/land11081130

Xu, Y. T., Huang, X., Bao, H. X. H., Ju, X., Zhong, T., Chen, Z., et al. (2018). Rural land rights reform and agro-environmental sustainability: empirical evidence from China. Land Use Policy 74, 73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.038

Xu, D. D., Yong, Z., Deng, X., Zhuang, L., and Qing, C. (2020). Rural-urban migration and its effect on land transfer in rural China. Land 9, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/land9030081

Yang, H. X., Huang, K., Deng, X., and Xu, D. (2021). Livelihood capital and land transfer of different types of farmers: evidence from panel data in Sichuan Province, China. Land 10. doi: 10.3390/land10050532

Yang, Z. H., Li, C. X., and Fang, Y. H. (2020). Driving factors of the industrial land transfer price based on a geographically weighted regression model: evidence from a rural land system reform pilot in China. Land 9:7. doi: 10.3390/land9010007

Yang, F., Liu, W., and Wen, T. (2022). The rural household’s entrepreneurship under the land certification in China. Cogent Eco. Finan. 10:2091088. doi: 10.1080/23322039.2022.2091088

Ye, J. Z. (2015). Land transfer and the pursuit of agricultural modernization in China. J. Agrar. Chang. 15, 314–337. doi: 10.1111/joac.12117

Yu, P. H., Fennell, S., Chen, Y., Liu, H., Xu, L., Pan, J., et al. (2022). Positive impacts of farmland fragmentation on agricultural production efficiency in Qilu Lake watershed: implications for appropriate scale management. Land Use Policy 117:106108. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106108

Yu, X. L., Guo, X. L., and Wu, Z. C. (2014). Land surface temperature retrieval from Landsat 8 TIRS-comparison between radiative transfer equation-based method, split window algorithm and Single Channel method. Remote Sens. 6, 9829–9852. doi: 10.3390/rs6109829

Zhang, Y. L. (2012). Institutional sources of reform: the diffusion of land banking systems in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 8, 507–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00256.x

Zhao, Y. (2022). The factors influencing the supply of rural elderly services in China based on CHARLS data: evidence from rural land use and management. Science 10:10. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1021522

Zhou, Y. R., Chen, T., Feng, Z., and Wu, K. (2022). Identifying the contradiction between the cultivated land fragmentation and the construction land expansion from the perspective of urban-rural differences. Eco. Inform. 71:101826. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101826

Zhou, Y., Li, X. H., and Liu, Y. S. (2020). Rural land system reforms in China: history, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 91:104330. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104330

Zhou, C., Liang, Y. J., and Fuller, A. (2021). Tracing agricultural land transfer in China: some legal and policy issues. Land 10:58. doi: 10.3390/land10010058

Keywords: farmland transfer, poverty vulnerability, future poverty, difference-in-difference, smallholder households

Citation: Chen J, Yang M, Zhang Z, Wang Z and Zhang J (2023) Can farmland transfer reduce vulnerability as expected poverty? Evidence from smallholder households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1187359. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1187359

Edited by:

Dingde Xu, Sichuan Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Anlu Zhang, Huazhong Agricultural University, ChinaPeng Jiquan, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China

Copyright © 2023 Chen, Yang, Zhang, Wang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mingwei Yang, MjAyMDY1MTkwNkBlbWFpbC5jdGJ1LmVkdS5jbg==

Jie Chen1

Jie Chen1 Mingwei Yang

Mingwei Yang Zheng Wang

Zheng Wang Jianyu Zhang

Jianyu Zhang