- 1School of Psychology, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

- 2UNE Center for Agribusiness, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

- 3International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Rabat, Morocco

Introduction: This study is a review of secondary literature that has been synthesized to extract information and demonstrate the implementation and impact of community conversations (CCs) on gender aspects of social norms in livestock-based systems in Ethiopia.

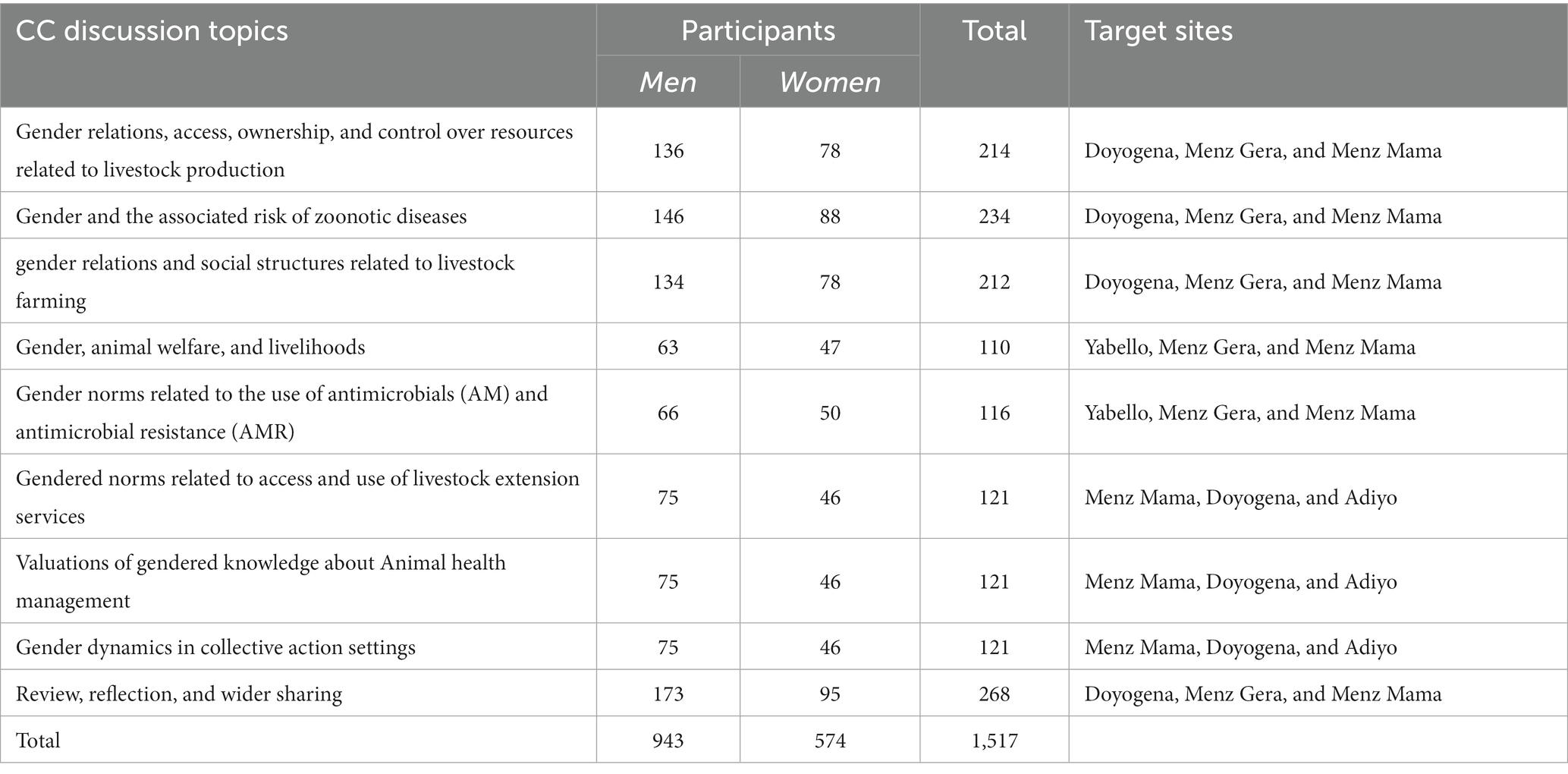

Methods: The study used the phenomenological method of qualitative literature review to sketch the gender transformative approach to the delivery of knowledge products in a program on transforming the small ruminant value chain. The CC aimed at addressing gender-related norms in the division of labor, resource ownership, and handling practices of animals and their products previously identified, and those that emerged during the CC events across the study sites. A total of 1,517 community members (out of which 574 are women) took part in various CC events.

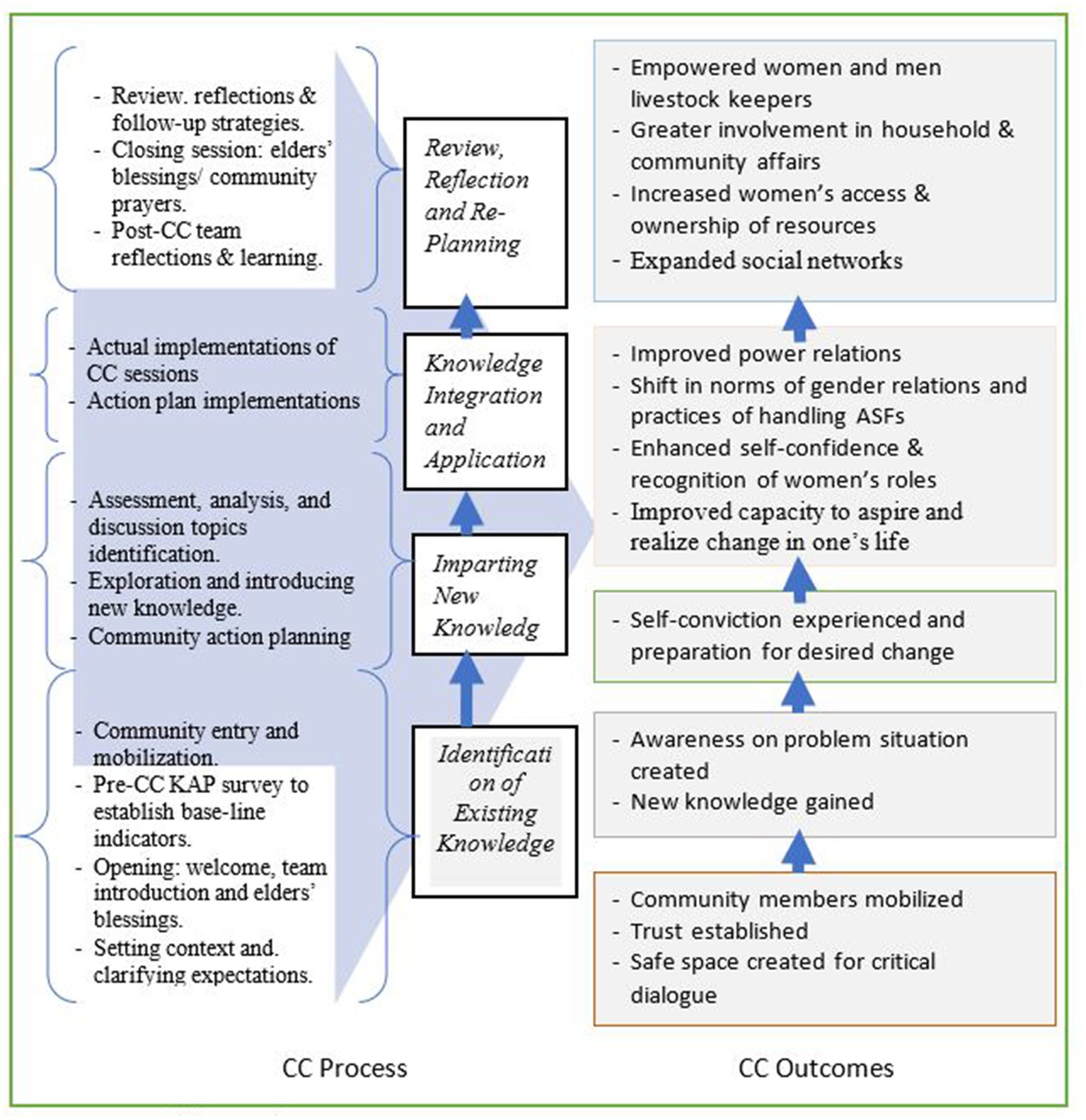

Results and discussion: The review shows that the gender-related norms addressed were in line with the identified constraining norms faced by women livestock keepers in the mixed and livestock-based systems. The CC approach adopted complied with the stages laid out in literature: identification of existing knowledge; imparting new knowledge; knowledge integration and application; and review, reflection, and re-planning. The process was inclusive and community-engaging, which possibly cultivated intrinsic motivation and ownership of the process. Changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices at household, community, and institutional levels were identified. The conclusions include institutionalizing the gender transformative approach in the public agricultural extension system. This could be facilitated by the generation of robust objective evidence of impacts and guidance for subsequent scaling at local, regional, and national levels.

Introduction

The major role played by gender norms as structural barriers to gender equality worldwide is increasingly being recognized among researchers, policy-makers, and development practitioners (Legovini, 2006; Aguilar et al., 2015; Bayeh, 2016; Didana, 2019). Gender norms are conceptualized as a social system that governs how resources, roles, power, and entitlements are distributed based on masculine or feminine identities (Ridgeway and Correll, 2004). So, it is the social rules and expectations that guide how the gender system operates (Pearse and Connell, 2016). In recent decades, research and development interventions were criticized for their failure to sufficiently recognize and address the underlying causes of gender inequality that affect the planning and implementation of projects and programs (Kumar and Quisumbing, 2015). In response to this, various transformative methodologies have been formulated and tested in different parts of the world, including Ethiopia (Drucza and Abebe, 2017). These methodologies include the Transformative Household Methodology (THM), Community Conversation (CC), Social Analysis and Action (SAA), the Family Life Model (FLM), the Gender Action Learning System (GALS), and Rapid Care Analysis (RCA).

The Livestock CRP1 in Ethiopia, implemented by ICARDA2 and ILRI,3 adopted a gender transformative approach known as community conversation (CC), in order to address perceived gender inequality in small ruminant value chain development. This has been a focus of the SRVCD4 program. Nevertheless, the processes of CC interventions and their likely impacts have not been well documented. This study seeks to close this gap by addressing two research questions: (1) how were CCs implemented in mixed and livestock-based systems in Ethiopia under the Livestock CRP? and (2) Which norms related to gender were addressed and which outcomes eventuated? While review question 1 identifies and describes the CC intervention processes, review question 2 examines the effectiveness of CC interventions on outcomes relevant to this study. Hence, a thematic synthesis of the process, as well as the outcome evaluation, was carried out.

CC as a gender transformative approach

The application of GTA is historically linked to the health sector (Singh et al., 2022). GTAs are participatory approaches that aim for empowerment outcomes at household (HH) and community levels. They follow specified participatory steps that facilitate the achievement of desired empowerment outcomes, often involving the creation of vision, analysis of scenarios, action formulation, implementation, joint monitoring and evaluation of progress, and sustainable exit mechanisms (Drucza and Abebe, 2017; Lemma et al., 2019a). One such methodology that has been widely used in recent years to tackle the underlying causes of gender inequality is the CC (Gueye et al., 2005; Drucza and Abebe, 2017; FAO et al., 2020).

Community conversation resides methodologically among community-level participatory approaches that involve a series of facilitated community-level dialogues. It is a transformative approach whose goal is to bring community members together to identify and discuss solutions to their own development problems (FAO et al., 2020). CC is a flexible methodology in which people from the same community have open discussions about obstacles to achieving their individual and collective development goals. Such issues include gender norms, behavior, and practices (Gueye et al., 2005).

Community members participating in CC feel free to debate pressing issues, including sensitive ones, in a safe space for radical change (Lemma et al., 2019b). When effectively planned and implemented, the process of CC helps community members to feel included in the processes of decision-making that affect their individual and collective lives. It enables community members to feel empowered to question their values and consider their cultural and traditional practices freely. CC is recognized as being capable of cultivating a fundamental shift in gender norms because it engages both women and men in a critical examination of values, beliefs, and practices (FAO et al., 2020). In both the short and long term, such shifts result in fewer gender-based constraints on women’s roles, decision-making, and mobility. Possible achievements include a shift toward a more balanced intra-household sharing of livestock husbandry practices, positive perceptions about women’s roles, and ultimately control over animals and other resources (Lemma et al., 2018a,d). Transformative approaches such as CCs trigger interest in change by raising the level of participants’ awareness of the causes of the undesirable behaviors, constraining gender norms and relations, on individual, household, and community goals (Cornwall, 2016; FAO et al., 2020).

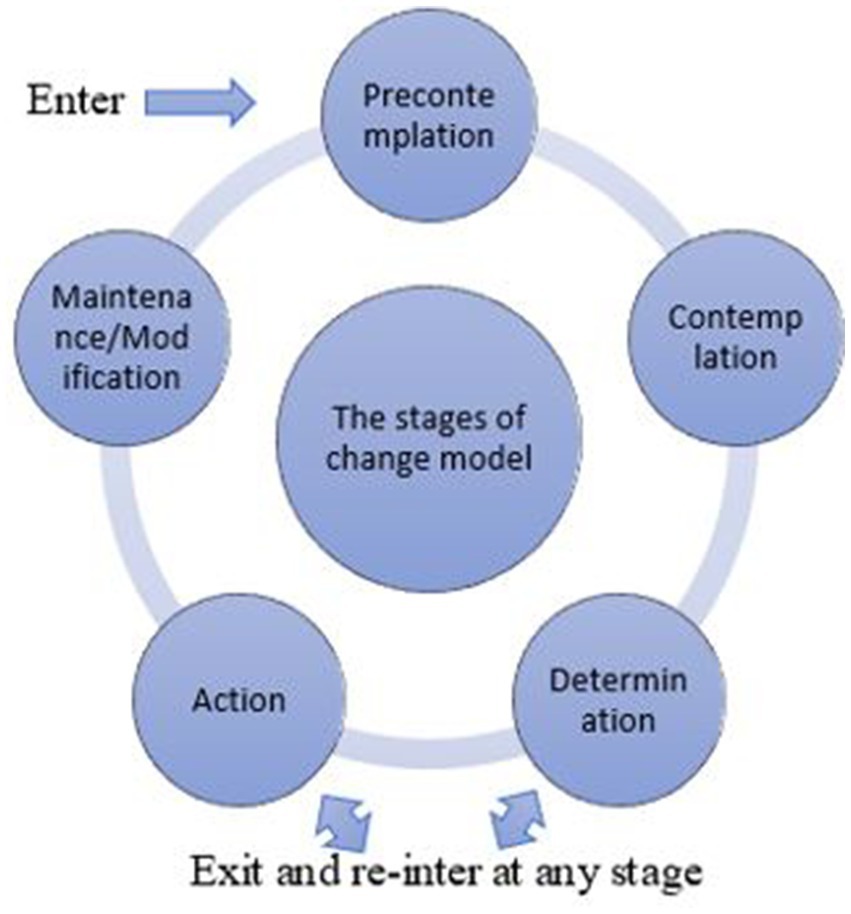

The participatory nature of CC cultivates ownership of the change process. There are parallels between CC and Self-Determination Theory (SDT), in particular, on motivation. SDT states that agents are motivated to take action if the behavior is perceived to be beneficial (Deci et al., 1991). In this study, we show how CCs motivated participants to go further and take action for change in desired behaviors. The theory suggests that if the personal utility of desired behaviors is understood, internalizations of the new behaviors trend toward forms of self-regulation. However, SDT argues that this happens most effectively when engagement is based on choices with minimum pressure, and when feelings and perspectives are acknowledged in the change process (Deci et al., 1991). The process of motivation to action, motivational readiness to change, occupies a five-part continuum of behavioral change according to the transtheoretical cognitive model (Webb et al., 2010; LaMorte, 2022). It begins with precontemplation―prior to awareness of the problem and intention to change future behavior―to the last stage in the continuum which is maintenance, prevention of relapse, and consolidation of gains. In between, the continuum spans awareness of the problem and consideration of changed future behaviors, preparation to act, belief in the ability to change, and modification of behaviors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The transtheoretical model (stages of change). Adopted from LaMorte (2022).

Community conversation capitalizes on local resources to develop context-specific knowledge products, and so development practitioners can use the knowledge for the development of inclusive and customized informational materials. With the recognition of the importance of CC as a powerful gender transformative approach, UNDP began to implement it in 2001 across several countries, including Ethiopia, and developed the Community Capacity Enhancement Handbook (CCEH) to guide program staff (Drucza and Abebe, 2017; FAO et al., 2020).

The standard implementation of CC entails activities twice a month over a period of 9 months to 1 year, in which up to 50 participants can take part at a time. Variations are noted in the literature (Drucza and Abebe, 2017; FAO et al., 2020). According to Gueye et al. (2005) and Drucza and Abebe (2017), the CC implementation process can be generalized into three steps―preparation, implementation, and reflection. However, a more detailed view portrays six stages―relationship building, identification, exploration, decision-making, implementation, and reflection.

Setting the scene: the need for GTAs in Ethiopia

A growing body of research shows that at the national level, significant gender differentials exist in the Ethiopian agricultural system, putting women in a disadvantaged position (Yisehak, 2008; Asrat and Getnet, 2012; Leulsegged et al., 2015; Elias et al., 2018). Despite rural women’s key role in the process of agricultural production, processing, and marketing, they are generally perceived as marginal actors (Asrat and Getnet, 2012; Leulsegged et al., 2015). In the case of livestock production in Ethiopia, numerous previous studies have highlighted the significant influence of gender norms affecting livestock production (Kinati et al., 2018; Kinati and Mulema, 2019; Mulema et al., 2019a, 2020, 2021), implying the importance of introducing gender transformative interventions that can ensure gender equitable benefits. Literature reveals that both men and women farmers are actively involved in livestock production (Belete and Charmaz, 2006; Hulela, 2010; Ragasa et al., 2012), although women’s contribution is culturally undervalued (Kinati et al., 2018). It is often argued that the reason women’s contribution is not welcomed or less valued is associated with norms that are embedded in the socio-culture of the society (Asrat and Getnet, 2012; Leulsegged et al., 2015). Non-recognition of women’s roles not only affect their economic status but also their family’s well-being and the country’s economy at large (Bayeh, 2016).

In the mixed and livestock-based systems, studies under the Livestock CRP concluded that gender relations are highly unequal (Kinati and Mulema, 2016; Kinati, 2017; Mulema, 2018). Women’s access to, ownership of, and control over productive resources are markedly limited due to gender norms (Zahra et al., 2014; Galiè et al., 2015). Existing gender norms not only discourage women from owning key assets but also limit their access to other opportunities. For example, in Bonga, Ethiopia, women are discouraged from owning livestock and as a result forgo opportunities to access livestock-based institutions such as the breeding cooperatives (Kinati, 2017; Mulema et al., 2019a). Yet, if such attitudes are transformed and women are allowed to own animals and then become members, they could not only generate additional income for themselves and their families but also help to strengthen the cooperative itself (Kabeer, 2017).

The gender aspect of social norms which form the basis for gender relations, comprising the “differential rules of conduct for women and men” (Pearse and Connell, 2016, p. 35), are shaped by individual behavior as well as social institutions (Laven, 2010). Norms set roles to be played by women and men in agriculture, and more importantly, such norms give rise to gender-differentiated capacities to access, own, and manage assets (Elias et al., 2018) and are largely responsible for the gender gap in use of opportunities between men and women in agriculture (KIT et al., 2012). They expose women and men to different levels of risks (Kristjanson et al., 2010), for example in livestock farming, exposure to zoonotic diseases bears relation to the distinct gender roles. They define relations within households and communities, and they impact the allocation of decision-making responsibilities, as well as access to information and other important resources (Flora and Flora, 2008). Systems of access, ownership, and control of resources vary greatly across contexts, influenced by the contextual norms that determine the meaning and dynamics of resource allocation (Galiè et al., 2015). If the gender differential in access to inputs, due to the underlying structural constraints, is addressed, for example in Ethiopia alone, a 35% increase in productivity could be achieved (Tiruneh et al., 2001). The gender productivity gap is largely attributed to the underlying structural constraints (World Bank, 2015).

To deal with the negative impact of social norms in the global south, social norms theory has been applied to address norms related to human health, such as intimate partner violence and female genital cutting (Mackie and Lejeune, 2009; Mackie et al., 2015; Gelfand and Jackson, 2016). The positive outcomes achieved in health through strategies derived from social norms theory (Mackie and Lejeune, 2009) led to the design and application of approaches in development, including agriculture, which are consistent with social norm theories. In the development sector, the focus is on the “[…] ‘social’ reasons why individuals do what they do” (Cislaghi and Heise, 2020, p. 408) to transform gender norms mainly to achieve women’s economic empowerment (Markel et al., 2016) and gender equality (Cislaghi and Heise, 2020).

In the remaining sections of this article, we present the methods of data collection and analysis in section two. In section 3, findings and a discussion are presented. The final section concludes with the implications of the study.

Methods for data collection and analysis

Background and conceptual framework

The SRVCD program, through its research and development partners, has implemented various interventions since 2013 to develop and deliver innovations for livestock value chain development across Ethiopia’s major sheep and goat-producing districts. These include breed improvement through community-based approaches, animal health management, animal feed and nutrition improvement, and market development through collective action.

In order to address the constraining norms related to gender, a series of CCs was designed and implemented in five target sites namely Doyogena, Menz Gera, Menz Mama, Adiyo, and Yabello districts (Mulema et al., 2020). These sites are also the target sites for the small ruminant value chain transformation program. Following the CC implementations at the community level with men and women program participants, knowledge products such as technical research reports, blog stories, syntheses of lessons learned, extension guidelines, technical briefs, and training tools were produced.

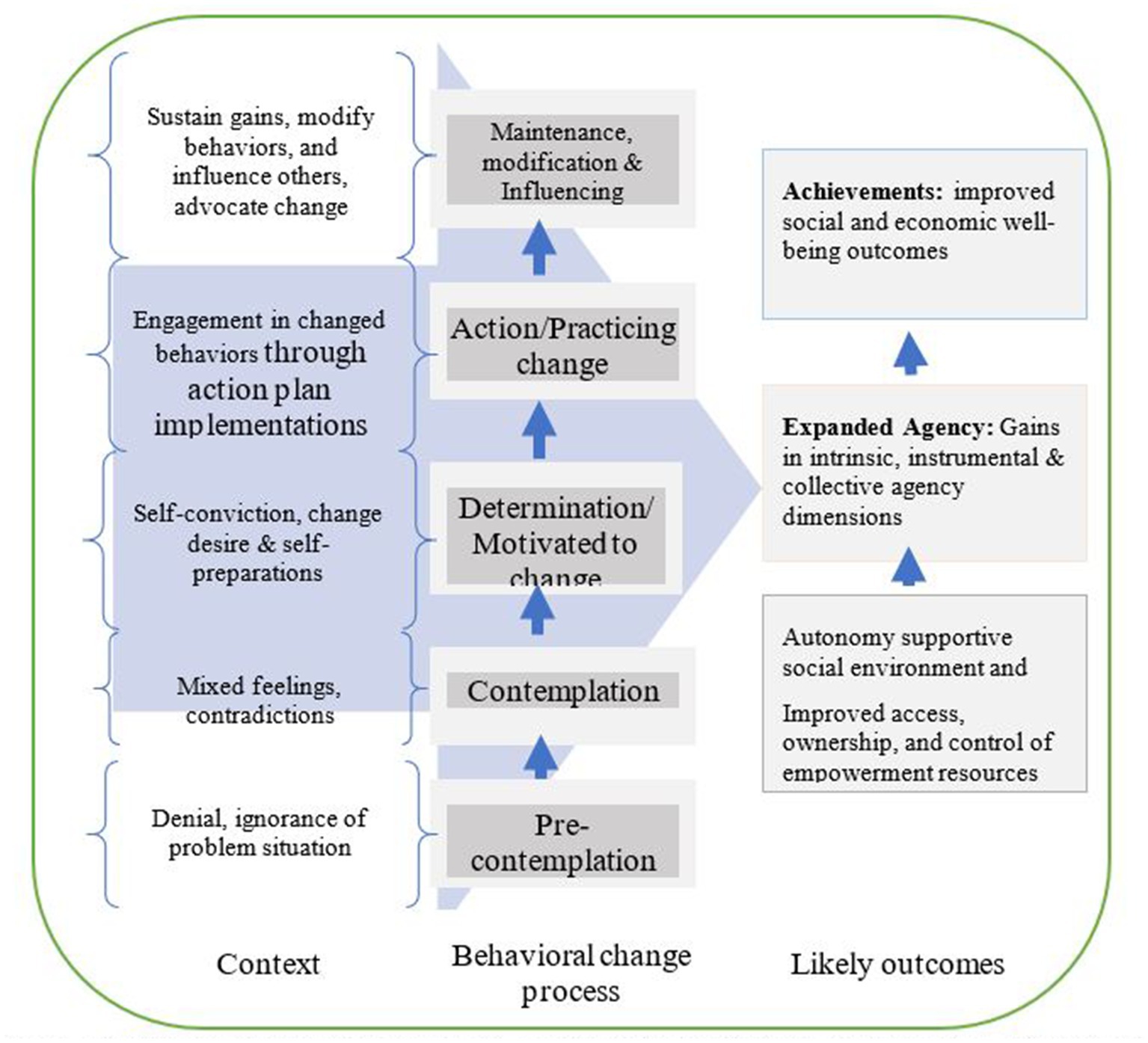

We hypothesize that CCs, if carefully implemented, will transform gender norms and eventually have an empowerment impact on the target communities. For example, FAO et al. (2020) reported that CCs brought about changes in attitudes, improved intra-household relations including decision-making, transformed gender roles toward equitable distribution of workloads, and improved women’s participation and leadership skills. The success of CCs in transforming the normative context highly depends on the facilitation process which in turn is determined by the level of facilitators’ skills in CC implementation. In most CC manuals, the role of facilitators in carrying out a successful CC process is highly emphasized (Drucza and Abebe, 2017). Moreover, the approach can lead to joint actions. The various interventions being implemented by the SRVCD program can also accelerate the empowerment effects of CCs on target communities. As a result of changes in gender norms, positive changes in gender equality outcome indicators are expected. These could include a shift in norms related to gender relations, enhanced access to group membership, decision-making and control over resources and income, increased market participation, expanded social networks, and improved capacity to aspire to and realize changes in their lives (Figure 2). When women operate through collectives, they have been shown to gain self-esteem, confidence, and self-reliance, leading to empowerment at both an individual and group level (Deshmukh-Ranadive, 2005).

Figure 2. Behavioral change process and hypothesized empowering effects of CC intervention. Constructed based on Webb et al. (2010), LaMorte (2022), Lemma et al. (2019e), and SRVD program information.

According to Lemma et al. (2019e), at the beginning, CC participants exhibit ignorance of a problem situation as they tend to adhere to the existing norms. Because gender norms are deeply embedded in social hierarchies and structures, both men and women conform to this system of ‘idealized’ gender relationships (Johnson, 2005). When interventions are considered contaminating and disruptive to the existing gender hegemony, community members often exhibit resistance (Connell, 2011), denying the existence of the problem, for example, by claiming that they jointly share resources and make decisions. In the behavioral change process, this situation is considered the pre-contemplation or unawareness stage and unpacked through deeper and critical dialogues which eventually leads to the contemplation or awareness stage where community members acknowledge/recognize the problem situation and become open to explore and analyze the benefits and barriers to change. At this stage, CC participants are assisted in recognizing the problem situation through analysis of key knowledge, attitudes, and practices while introducing new knowledge to challenge their perceptions. The introduction of new knowledge often causes conflicting emotions/feelings among CC participants which need to be assisted through building their confidence and readiness for change that would help them progress to the determination stage in the behavioral change processes. The determination stage involves readiness and preparation for change. At the next stage, CC participants actively engage in the learning process and identify action points to reinforce the new knowledge gained and progress to practicing change because they understand the benefits of the particular behavioral change. In the final stage through change retention mechanisms, CCs are intended to sustain the change experienced by participants and influence the wider community (Webb et al., 2010; Lemma et al., 2019e; LaMorte, 2022).

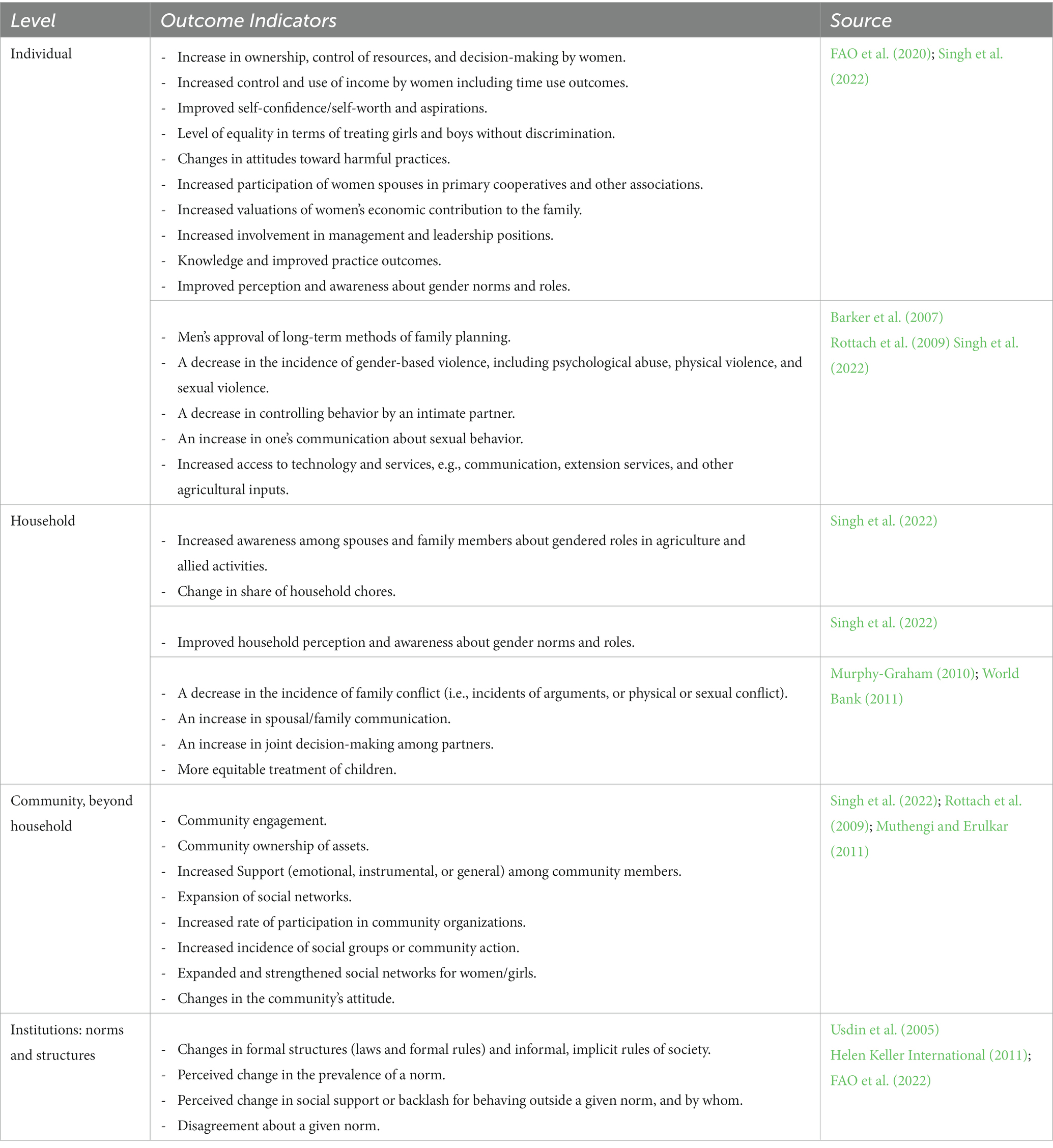

In many gender transformative programs, perception-based indicators were used in an attempt to quantify intervention impacts at various levels (Table 1). For example, change in attitudes toward oneself or gender norms and behaviors (Barker et al., 2007; Ricardo et al., 2011), change in household relationships (World Bank, 2011), and new or change in relationships beyond the household (Rottach et al., 2009; Muthengi and Erulkar, 2011; FAO et al., 2022) are the common indicators used for assessing the outcomes of gender transformative programs.

Data sources and study areas

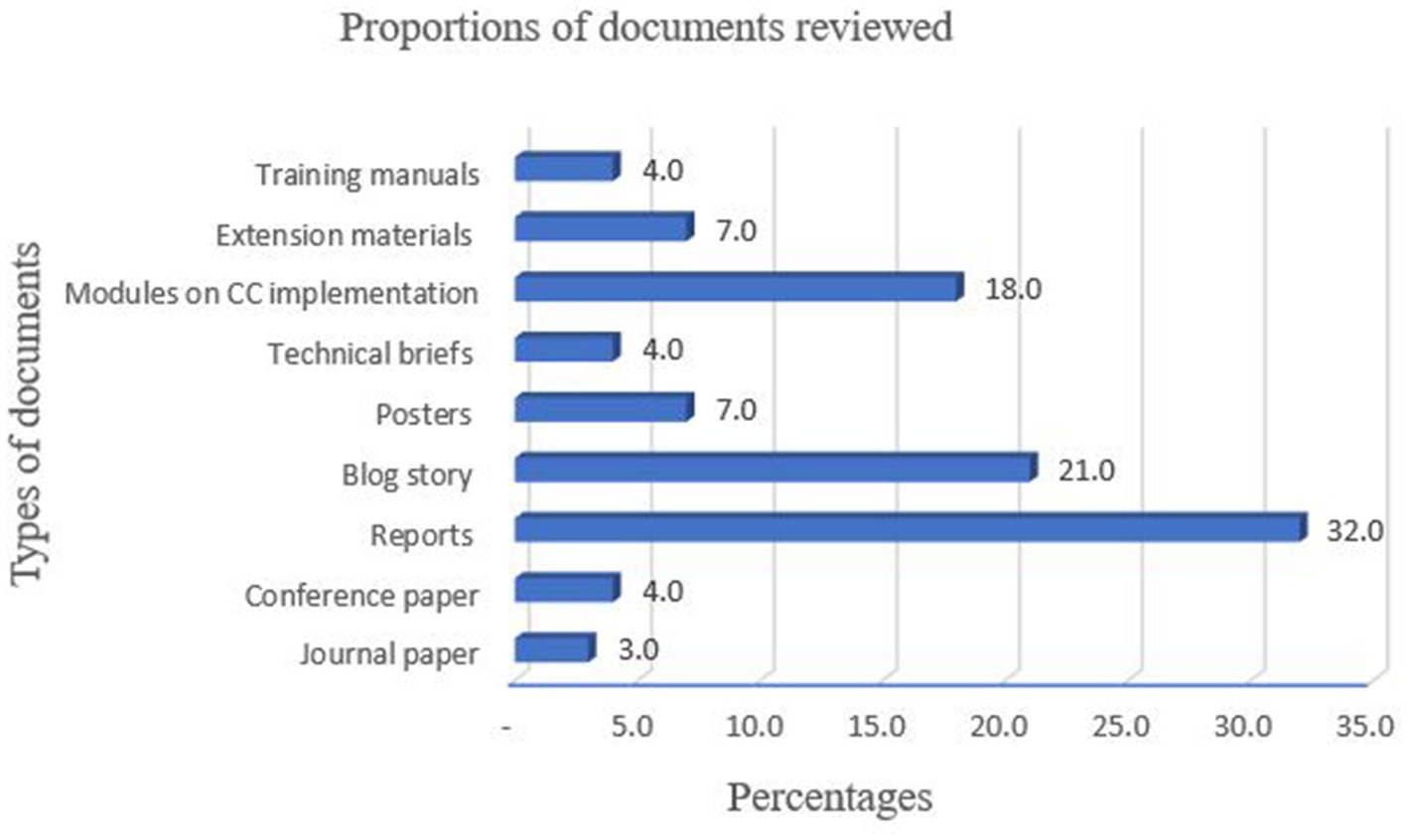

The population of interest for this study is men and women livestock keepers and development actors. Hence, data for this study were generated from a comprehensive review of the available knowledge products from CC interventions by the Livestock CRP in Ethiopia. Available knowledge products were systematically searched. CC knowledge products that were published on CGSpace5 and outputs in recognized journals were considered as inclusion criteria for final selection and analysis. In the first stage, the search resulted in 44 published and unpublished reports including technical reports, blog stories, posters, manuals, extension materials, and training materials. In the second stage, after reviewing the titles and abstracts, 27 published and unpublished reports were screened and finally reviewed to conduct this analysis (Figure 3). We recognize that the considerations of unpublished materials in this review analysis could pose implicit biases, possibly emphasizing success stories and glossing over challenges encountered. In order to minimize this and give an unbiased and objective examination of CCs as a tool for leading to social normative change, we adopted a more critical perspective and closer readings of these materials so as to draw the conclusions of this study. We questioned the assumptions behind the reports and examined their strengths and weaknesses. As much as possible, we provide detailed information on the reported strategies assumed to have provoked changes. Nevertheless, there is a need to objectively validate the findings reported regarding changes in behavior and practices by interviewing both spouses, particularly spouses of those claiming the change in order to draw lessons and identify gaps for future interventions.

The SRVCD program’s CCs were implemented in five districts with men and women community members. On average, four rounds of CCs were held (including closing sessions) over a period of 4 months in most of the target sites. This is relatively less frequent than outlined earlier (Drucza and Abebe, 2017). Table 2 presents CC discussion topics, participants by gender, and target sites. Various discussion topics along the different livestock value chain stages were covered in the CCs. Distribution among the target sites was somewhat uneven, and this is expected as the sites’ contexts differ (Hulela, 2010; Waithanji et al., 2013a). The community conversations engaged 1,517 (574 women, 38%) community members who took part either as couples or individuals in one or all four rounds of CC sessions.

Data collection and analysis

For the searched studies, data extraction was carried out using pre-developed data extraction tools. Data analysis followed the steps laid out by Randolph (2009). Bracketing, the first step, involves the identification of the phenomenon to be investigated and then “bracketing” own experience with the phenomenon identified. In the second step, collecting data, the researcher collects the data about the phenomenon by reading existing reports of research on the phenomenon. Based on the collected data, the reviewer identifies meaningful statements as a third step. The reviewer then records claims made about the phenomenon of interest. In the fourth step, the reviewer tries to give meaning to those statements collected through repeated categorizations, paraphrases, and interpretations. In the last step, thick/rich description, the reviewer creates a tick description of the essence of the primary researchers’ experiences with the phenomenon (Randolph, 2009).

The extracted data were organized and analyzed following the steps suggested by Randolph (2009) and Belete and Charmaz (2006). Using an Excel spreadsheet, open coding, based on the focus and type of literature (published/unpublished), and then focused coding, the gender norms reported on, was completed. The codes were further synthesized and categorized into themes (such as norms related to gender roles, decision-making, and use of animal source foods and handling practices, and norms of doing extension and research, and institutional rules) and then the themes were linked to the research questions of the study.

Results

In this section, we begin by presenting findings on the contents of CC discussion topics. Then, we lay out the implementation process as adopted by the program in comparison with CC steps as suggested in the literature before reporting on the outcomes, success factors, and associated challenges identified.

Focus of the CCs

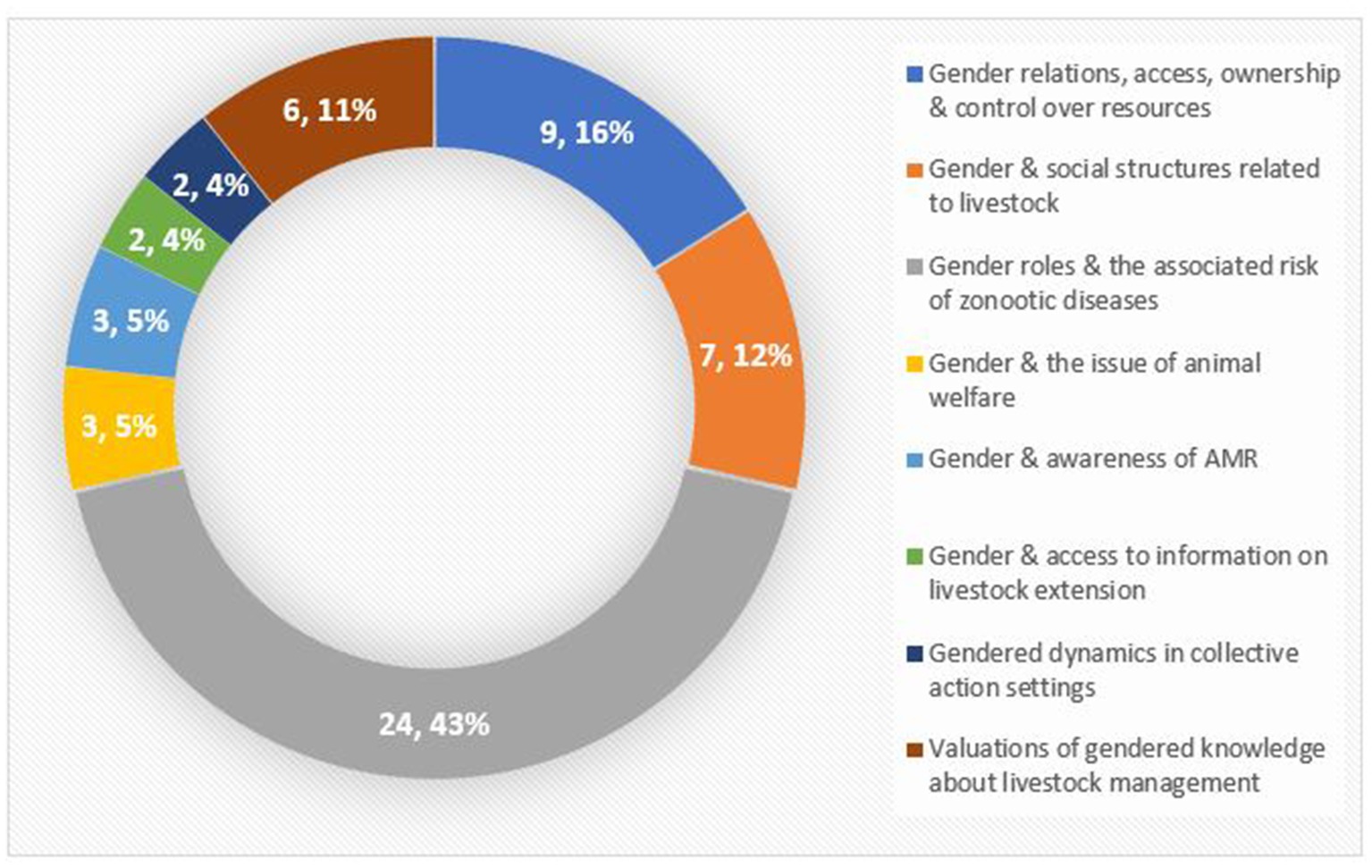

Norms related to gender roles and the associated risk of zoonotic diseases were mentioned in approximately 24% of the reports reviewed, making them the central discussion topics of the CCs (Figure 4). Building on this, gender relations in access, ownership, control, and decision-making with regard to livestock and related resources were part of the CC topics targeted (Lemma et al., 2018d). Associated with gender roles, the risk of zoonosis emanating from inappropriate handling of animal source foods (ASFs) as a result of men’s and women’s limited knowledge, wrong attitudes, and bad practices (Alemu et al., 2019; Mulema et al., 2019b) were included in the CC discussion topics. Linked to these, institutional and structural factors influencing the prevention and control of zoonotic diseases and animal welfare were the contents of the CCs particularly at the Doyogena, Yabello, and Menz study sites (Lemma et al., 2019c,d; Mulema et al., 2020).

Figure 4. Frequency of targeted gender related norms reported in the reviewed literature on which CCs implemented by the Livestock CRP in Ethiopia.

Moreover, gender-differentiated knowledge about antibiotics and their use (Alemu et al., 2019), and access to information were part of the CC topics that were addressed in the CC discussions (Lemma et al., 2020b). This featured an understanding of gendered attitudes and improving community awareness of clinical signs, causes, transmission pathways, prevention, and control of animal diseases (Lemma et al., 2021b). Gender norms in relation to group membership—related beliefs such as it is not appropriate for a woman to be in associations where the male spouse is a member—were also among the topics identified and included in the CCs (Mulema et al., 2019a). Structural constraints to women’s membership of associations and their lack of access to information and their limited mobility to participate in farming advisory meetings and formal groups constituted the focus of CC discussion topics (Lemma et al., 2019d).

CCs implementation processes

One of the key objectives of this review of literature on CCs implemented by the Livestock CRP was to understand the CC process. Singh et al. (2022) argue that although CC as a gender transformative approach can trigger the development of agency and transform gender relations in access and control over resources, the emphasis is on its process. The CCs implemented were conducted at the community level involving various actors. Participants of the CCs were both men and women community members and staff of kebele6 and district-level government institutions such as kebele-level leaders, managers, and development agents; cooperative promotion office; women, youth, and children affairs office; livestock development office; and agriculture and natural resource development office.

The intervention was aimed at raising awareness, changing attitudes, transforming constraining gender norms, and ultimately bringing about the empowerment of women livestock keepers. It envisages bringing behavioral changes among men, women, and community-level development actors regarding gender norms related to the key issues of the CC discussion topics identified (Figure 4). By questioning the gender roles and resource distributions, it aimed at elevating women’s status through challenging unequal power relations. This is one of the key objectives of gender transformative approaches such as CC (Rottach et al., 2009). By creating a safe space for critical dialogues, the current CCs helped women participants to challenge the existing male-dominated livelihood systems. The flexibility of CC in using a wide variety of learning tools helped to create a discussion environment for participants which is informal, inviting and non-threatening. Such tools include context-setting posters, thought-provoking informal storytelling, or the use of pictures and opinion leaders aimed at creating a warm learning environment, and building rapport, trust, and intimacy among participants and as well as with facilitators. Beyond creating awareness, such tools motivated participants by creating the need for engagement, learning, and action. The process helped participants not only understand but also acknowledge the existing unequal power relations and became motivated to cooperate in changing it for mutual benefit (see testimonies in Table 3). As a result, men began allowing their spouses to join community-based producer associations which used to be men’s only associations. This created windows of opportunities for them through which women strengthen their agency and challenge the old cultural patterns of male domination in productive farming. Their improved access to producer groups rates them among those farmers respected in the community.

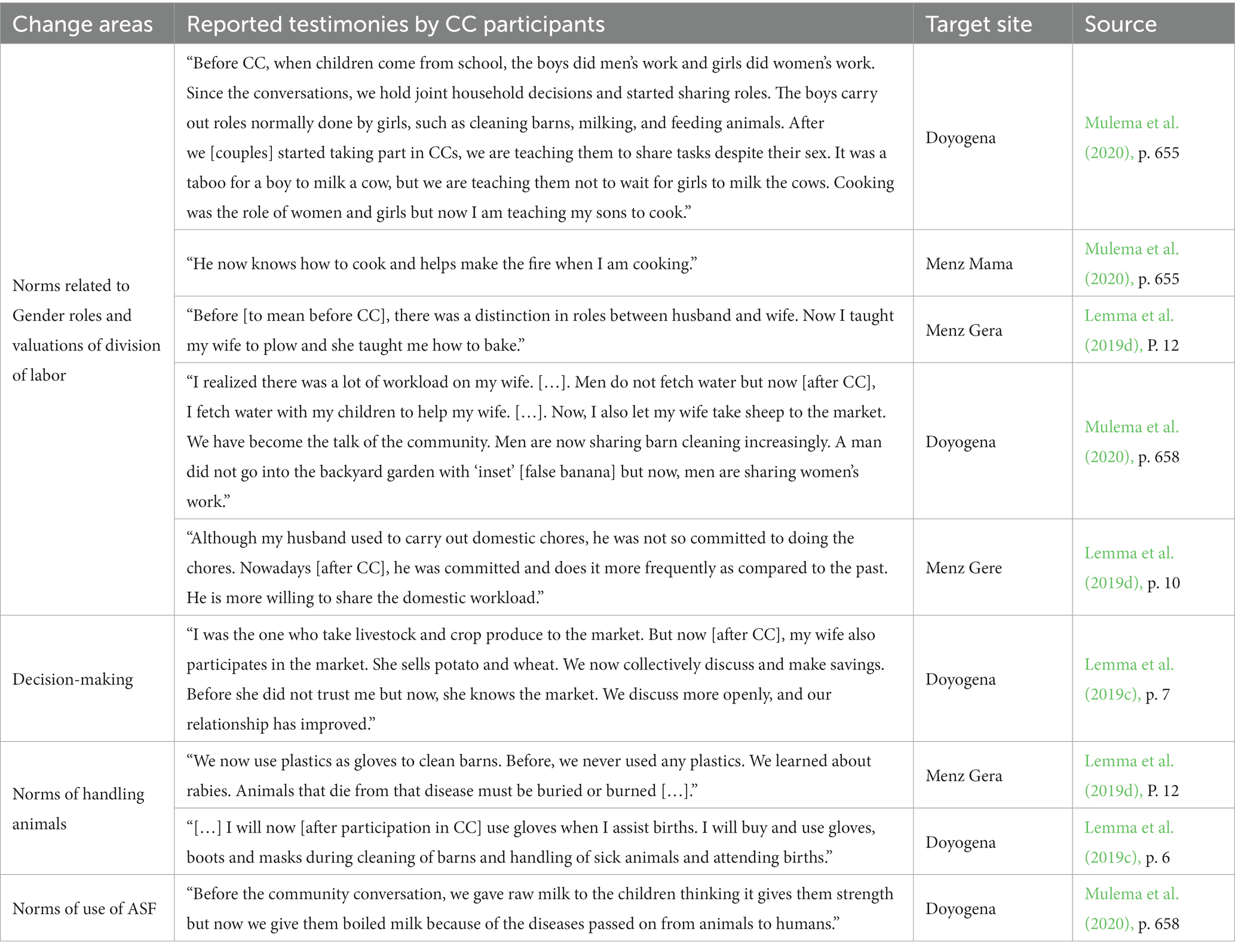

Table 3. Relaxation of norms around gender roles at the individual and household level reported as outcomes of the CC.

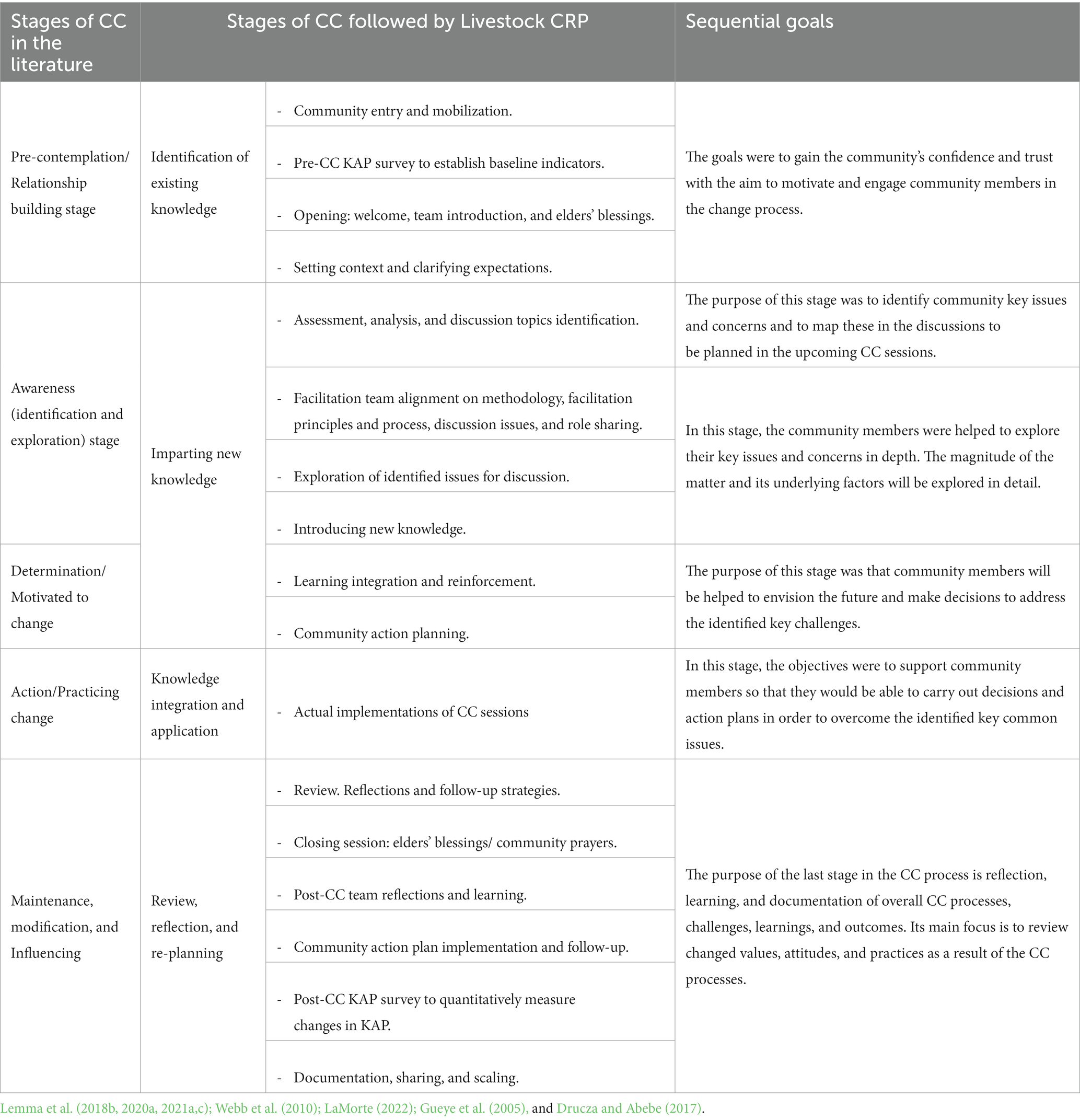

Community conversation interventions mainly went through the key stages of CC implementations as suggested in the literature (Gueye et al., 2005; Drucza and Abebe, 2017): relationship-building stage, identification stage, exploration stage, decision-making stage, implementation stage, and reflection stage. Process comparison shows that the CCs implemented by the program followed recommended stages with slight adaptation to the context (Mulema et al., 2019a,b; Lemma et al., 2019c,e,g).

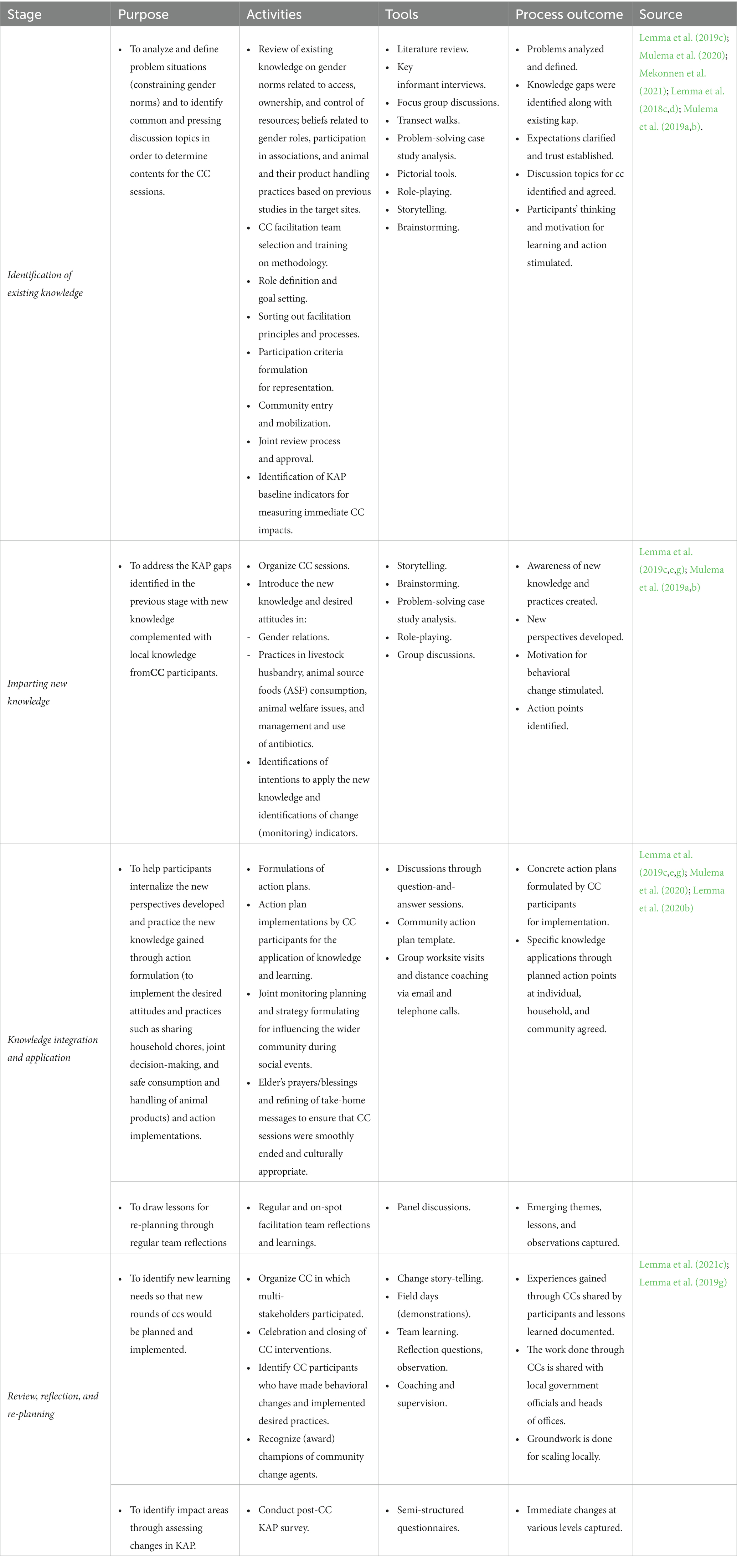

The detailed CC stages adopted by the program presented in Table 4 can be summarized into four key stages: identification of existing knowledge; imparting new knowledge; knowledge integration and application; and review, reflection, and re-planning. Each stage has specific purposes, activities, tools of facilitations, and processes (see Table 5 in the Annex). Across the study areas, each CC stage was covered in separate CC sessions. The first round of CCs focused on the identification of existing knowledge and norms about animal husbandry practices along with introducing and validating the associated constraining gender norms identified. The process helped to develop trust with participants and determine the content for the subsequent CC discussion sessions. The subsequent CC sessions were aimed at bringing changes in attitudes and practices at the individual and community levels and beyond. The last CC session was designed to ensure sustainable exit mechanisms and lay the groundwork for scaling up the experience by creating awareness among government institutions at higher levels.

Table 4. Comparing CC processes as suggested in the literature and implemented by Livestock CRP in Ethiopia.

At the end of every CC, the facilitation team conducted an on-the-spot reflection. The process of reflective and generative team analysis helped the team to learn from the CC process and share experiences among facilitators to capture emerging themes, new insights, and lessons for the following rounds of CC implementations.

CC intervention outcomes

The CCs implemented have brought about several changes in KAP at various levels. The reviewed literature on CC interventions by livestock CRP in Ethiopia reported various outcomes. The process of CC resulted in interrelated changes in attitudes and behaviors at the individual, household, community, and institutional levels across the target areas (Figure 5).

Observed change at individual and HH levels

The changes reported as a result of CC interventions at HH and individual levels include shifts in mindsets and practices regarding gender roles and access to and control over resources (Table 3). They cultivated shared decision-making at the household level and proper handling of livestock and consumption of animal-source foods. One of the CC participants reflected saying “[s]ince the conversations, we hold joint household decisions and started sharing roles […]”, male from Doyogena” (Mulema et al., 2020, p. 655). Desired gender attitudes began to be exhibited among men and women CC participants. Through the implementation of the actions formulated during the CC sessions, shifts in gender roles were observed among community members. At Doyogena, Menz Gera, and Menz Mama, men began to take part in domestic activities which reduced women’s domestic work burden. For example, at Menz Mama, a woman participant witnessed the changes that happened in her home saying “He [to mean her spouse] now knows how to cook and helps make the fire when I am cooking” (Mulema et al., 2020, p. 655). Similarly, women started taking part in productive farming roles that brought them more income and recognition (Mulema et al., 2020) as a result of changes in attitudes and practices around gender relations. For example, because of changes in attitudes and increased men’s involvement in household chores, women were able to find time to join community-based associations that used to be men-only associations (Kinati et al., 2019b). This was reported in more than 24% of the literature items reviewed.

Improved household discussions led to active participation by HH members who were often neglected. The ability to share information within the household had improved. Women began to participate actively in major HH decisions that affect their lives (Lemma et al., 2019c,d). Changed attitudes and perceptions (Lemma et al., 2021c) associated with masculinity, i.e., productive roles such as membership in livestock institutions and livestock marketing are appropriate for men, and femininity, i.e., reproductive roles such as caring for livestock are appropriate for women, is what led to a more equitable gender division of labor (Kinati et al., 2019a). Both men and women CC participants not only witnessed that such attitudes and perceptions no more hold them back but also engaged in practicing the desired behaviors. This was reported by CC participants in the three study areas. Consequently, these changes led to greater household cooperation by cultivating trust and harmony. From a review of 61 programs, Marcu (2014) identified strong evidence that communication programs such as CCs are an effective way to challenge gender-discriminatory attitudes and practices. Beyond changing attitudes, CC triggered changes in practices at individual and household levels. Literature suggests that changing individual attitudes alone is insufficient to change behaviors (Haider, 2017). CCs have made greater efforts to engage participants in the desired practices through joint action formulations and implementations that are designed to challenge and transform the identified constraining gender norms.

The other change areas observed among men and women were changes in attitudes and practices regarding community norms for the handling of animals and consumption of ASFs. Men and women began to cook and boil meat and milk before eating and drinking. They also started using locally available materials as gloves when assisting animals during delivery (Lemma et al., 2019c; Mulema et al., 2020). Changes in intra-household relations and decision-making around animal health were reported. The CCs raised awareness among men and women about zoonotic disease, its causes, transmission pathways, and prevention and control measures. Moreover, it also raised awareness among community members about the problem of antimicrobial resistance. Change in perceptions, practices, and sharing of related information among HH members and with neighbors was reported as an outcome of the CCs (Lemma et al., 2019d). Men and women reported better use and handling of animal treatments after CCs. Customized action plans that were designed and implemented by CC participants led to the desired changes in attitudes and practices. The ongoing open dialogues created mutual learning and co-creation of knowledge that promotes understanding of one another’s perspectives and reduces “social distance” among participants (Lemma et al., 2019c,d).

Change at the community level

The behavioral changes and practices that eventuated at the household level were also observed at the community level. There were changes in gender relations such as women taking up the roles of men and vice versa. The following sentiments expressed by a male CC participant at Menz Mama district asserted this fact:

During our village saving group’s meeting, I [male spouse] talked about domestic role sharing experience within my family. After the meeting, one of the women participants approached me and asked if I can teach her how to use an ox-plow. The woman came to my farm and I showed her how to use the ox-plow. […] she also asked me to show her how to assemble the plow which I did. In return, I asked her to teach me how to bake Injera (Mulema et al., 2020, p. 655).

Similarly, a woman participant from the Menz Gera district shared her experience in reaching out to her community members:

“When you go out of the village, people often ask you where you were and what you did. I [woman spouse] went to a baptismal place and people asked me about the event I have attended, and I shared the information about sharing roles between husband and wife and the people said…our community is changing. […] we meet informally to share information and monitor each other” (Lemma et al., 2019d, p. 11).

The other reported changes at the community level include an appreciation of women’s roles, increased knowledge with regard to animal diseases and their management, and women speaking up in public spaces (Lemma et al., 2018c). Men acknowledged that women are more knowledgeable than they had previously understood regarding animal diseases, due to their gender roles in livestock husbandry (Mulema et al., 2020). CCs gave women the opportunity to speak freely and share their experiences. A study conducted by Alemu et al. (2019) in the same areas found that men and women demonstrated comparable knowledge of animal diseases. Livestock extension programs had also begun to consult and include women in their programs (Lemma et al., 2018c). It can be attributed to CC that it led to changes in development workers’ perspectives about women and their technical role in livestock development. Nevertheless, the literature reviewed does not provide quantitative assessments of these outcomes.

The changed attitudes and behaviors at the community level regarding gender roles also resulted in a wider impact. Women became members of associations, for example in breeding cooperatives, that improved their access to and control over resources and active participants in decision-making processes (Lemma et al., 2019f). Participation in such community associations could provide women the opportunity to actively participate in other community affairs. Women started voicing their own and fellow women’s concerns in public spaces. Stronger voices of women in community-level discussions were reported (Mulema et al., 2020). For example, CC participants who were champions in advocating for changed gender relations, such as women’s participation in masculine activities, were recognized by local government authorities in Doyogena at a community-level development event (Lemma and Tigabe, 2021d).

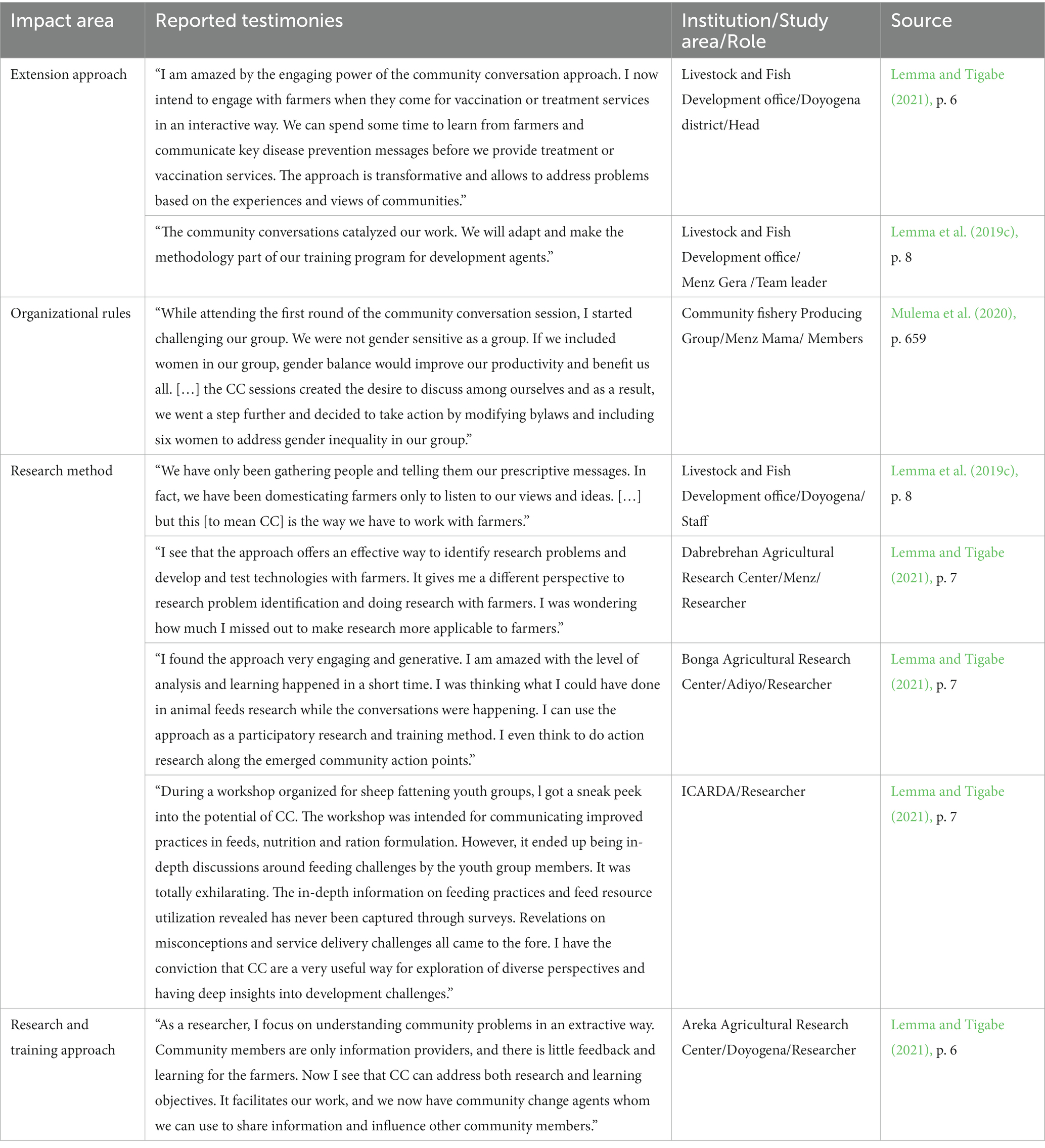

Change at the institutional level

The CC interventions, generally, strengthened the capacity of local actors who took part in the CC processes. The action points that emerged at the end of every CC session informed local-level planning processes and interventions particularly in livestock health management (Lemma et al., 2019c). Local leaders began institutionalizing the approach in their extension system in the target districts (Lemma et al., 2021c). Across the target sites, CCs served as collaborative learning and action platforms for community-level planning and actions particularly for animal health management (Lemma et al., 2021c). Apart from that, CC not only improved collaborations and enhanced functional linkages among community members but also strengthened institutional-level connectedness for joint and collaborative planning and actions among the various service providers across the target sites (Lemma et al., 2019e). Community-level institutions became more gender aware and responsive (Table 6). For example, a local producer group that used to have only men members at Menz was motivated by CCs to modify its bylaws and include women as members and experienced increased levels of innovation and resourcefulness or productivity (Kinati et al., 2019b).

Table 6. CC’s impact at the institutional level on norms of extension and research implementations and rules of engagement in collectives.

Key success factors and challenges

The CC was effective in bringing radical changes in attitudes and practices over a relatively short period of time. Several factors could contribute to the successful implementations of CCs and in achieving their goals. The facilitation team carefully designed, implemented, and monitored the process. The analysis made by cross-checking and comparing CC implementation guidelines and the reported CC processes and outcomes (Table 5) asserts the fact that CC was carefully designed and implemented. The change process could also be facilitated by the approach adopted, a transition from exploratory studies to applied research models7 (Badstue et al., 2020). The participation of couples, local-level development actors, development groups, and religious leaders could have created a favorable environment for CC participants to engage in the desired behaviors reported. Apart from that, the facilitation tools used are flexible and easily adaptable to the local context. The creative ways, such as pictorial tools used, fostered the process to engage easily with participants (Lemma et al., 2019d; Mulema et al., 2020).

The participatory nature of CC and its ability to engage participants to start with self-analysis of their own lives helped them to critically re-think and question dominant perceptions regarding existing gender relations. They realized that they are part of the problem and thus the solution. This encouraged them to commit and plan for change. Some of the benefits, such as sharing household roles, experienced by CC participants in a relatively short period of time motivated others to follow. Since couples participate together in the CCs, the approach likely empowers both and creates sustained transformation (Lemma et al., 2019b,c; Mulema et al., 2020).

The CCs created a safe space for both men and women to share experiences and thus address common pressing concerns—constraining gender norms. By working with both men and women couples, CC could trigger change and effectively bring long-lasting gender transformation. When couples have similar understandings and shared goals, they avoid conflict and cooperate toward achieving the goals (Lemma et al., 2019a,b,c; Mulema et al., 2020).

Some of the challenges noted in the reviewed literature with CC include reluctance to change, associated costs, and difficulties in measuring impact and attributing change. Some of the CC participants faced opposition to change from family members. For example, engagement of men in domestic chores is some households was met with nick-naming (Lemma et al., 2019a,b,c; Mulema et al., 2020). Apart from that, as CC requires greater readiness and continued engagement, it demands more time and resources which is always a challenge in developing countries like Ethiopia.

Discussion

This review of CCs implemented by the Livestock CRP in Ethiopia has shown that CC interventions went through stages as suggested in the literature (Gueye et al., 2005; Drucza and Abebe, 2017) with adaptations to the local context in order to ensure smooth entry and the community’s ownership of the process (Mulema et al., 2019a,b; Lemma et al., 2021c,e,g). The planning and implementation processes were in line with the standard implementation of CC (Gueye et al., 2005). When the implementation details were examined, the Livestock CRP implementation team had tried to develop achievement indicators during the first stage and quantitatively estimated the immediate impacts of CCs. In the literature, the impacts of CCs were often assessed qualitatively using in-depth qualitative methodologies once the intervention was completed. The use of baseline and end-line data, complemented with qualitative data, was one of the strengths of the gender transformative approach reviewed.

The major discussion topics related to gender norms addressed in the CCs include perceptions about women’s access, ownership, control, and decision-making associated with livestock and related resources (Mulema et al., 2019a,b; Lemma et al., 2019c,d). In addition, the documents reviewed indicated that unbalanced gender division of labor and the associated social structures, i.e., restrictive gender norms, were also incorporated in the CCs across the target sites. Apart from that, gendered perceptions about animal diseases, the risk of zoonosis emanating from inappropriate handling of ASFs enforced by cultural factors, and the issues of animal welfare were among the topics of the CCs, as were gender relations in collective action settings. The discussion topics covered by the CCs are relevant because these were reported as underlying causes of gender inequalities in livestock-based systems in several previous studies in the target sites (Zahra et al., 2014; Galiè et al., 2015; Kinati and Mulema, 2016; Kinati, 2017; Mulema, 2018).

Various changes at the individual, household, community, and institutional levels were reported as direct impacts of CCs although so far there is no robust analysis conducted considering the problem of selection bias. Nevertheless, the various techniques, such as roleplaying, demonstrations, and testimonies of individual CC participants who have realized benefits from CC interventions (Lemma et al., 2018d) could have played a role in creating a sense of ownership of the CC processes and resulted in changes at these levels. If agents perceived the desired behaviors to be valuable for effective functioning, people are motivated to adopt them according to self-determination theory. The theory suggests that in order to increase the likelihood of adopting changes, people not only need to be provided with choices about the new behaviors with minimum pressure but also their feelings and perspectives need to be acknowledged. If the personal utility of the desired behaviors is well understood by the agent, internalization of the new behaviors progresses most effectively toward autonomous forms of regulation (Deci et al., 1991). Drawing on this theory, one could think that the changes and anecdotal testimonies presented as a result of the CC interventions in this report imply that CC participants understood the personal utility of the desired behavioral changes they adopted based on their own choices. The shift made in gender roles by men and women CC participants, the appreciation of each other’s roles by spouses, and the practices of safe handling of ASFs as a result of gaining new knowledge with regard to zoonotic diseases and its associated benefits help assert this.

Nevertheless, households are often depicted not only as arenas of cooperation but also conflict. Spouses have been found to resort to destructive behaviors primarily to improve their relative position by hiding resources from each other (Mani, 2011; Castilla and Walker, 2013; Hoel, 2015) in contexts where common information, similar preferences, mutual affection, and shared norms of behavior are absent (Baland and Ziparo, 2017). Yet, CC can facilitate the development of these factors for a cooperative environment. Husband and wife get the same information by taking part in the same platform. Being exposed to the same information and benefits of desired behaviors, they can develop similar interests and mutual affections and progress toward shared but new norms of behavior. Moreover, more recent studies question the conventional wisdom that portrays the household as an arena of conflict. Repeated field experiments show that in the context of cash delivery programs, family welfare outcomes are not associated with the recipients’ gender (Benhassine et al., 2015; Akresh et al., 2016; Haushofer and Shapiro, 2017), and similarly there are no gender differences in cooperative behavior in lab experiments as well (Andreoni and Vesterlund, 2001; Croson and Gneezy, 2009). Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, households should be ideal arenas for cooperation, as both spouses benefit from the welfare outcomes (Del Boca and Flinn, 2012).

Community conversations provided participants with a platform where discussants had the opportunity to reflect on the common agenda from the perspectives of their own actions, beliefs, and values. The action plans formulated for implementation at the end of every CC session could be understood as evidence that the CCs not only engaged participants at both cognitive and emotional levels but also impacted agents at individual and collective levels to practice changed gender relations and engage in the new practices. For example, after having heated debates among themselves and receiving technical support from facilitators, CC participants understood that gender roles and power relations in livestock production are the results of social constructs and thus can be changed. They recognized that gender roles are generally biased against women and need to be balanced. Men participants acknowledged and appreciated women’s roles in livestock. These engagements at cognitive and emotional levels resulted in self-motivated action plans and their implementation at individual and household levels. The increased understanding of the benefits of change led participants to continually engage in self-motivated desired actions. For example, women started engaging in productive roles such as plowing and became registered members of producer associations while men started to be actively engaged in domestic activities such as cooking. These changes may have been achieved through an interrelated continuum of levels of motivational readiness to change (Webb et al., 2010). First, CC may encourage participants to challenge their cultural norms and values governing resource distributions, gender roles, and the consumption of animal source foods individually. Second, CC participants might be motivated to practice the desired behavior and begin to challenge their family members at the household level. Finally, the changed behaviors at the individual and household levels might diffuse to the wider community level through various social events, eventually bringing changes at scale in the mixed and livestock-based systems.

The processes of CC enable community members to reflect critically on the cultural norms that shape the gender relations and traditions of livestock management practices and handling of ASFs. They facilitated changes in attitudes that led to desired changes in norms and practices at household and community levels. In the longer run, critical dialogue among community members can shift gendered expectations and institutional rules embedded within social relations. Gender transformational approaches such as CCs can trigger interest in change by awakening people’s consciousness about the causal effects of social norms on women’s (men’s) lives and goals (Cornwall, 2016). Nevertheless, in order to sustain the dialogues and observed changes, continuous effort appears to be essential. In the implementation process of CCs across the target sites, the program actively engaged local research and development partners so as to ensure its continuity. Nevertheless, the integration of CCs into ongoing and planned development programs along with continued close follow-up would help to achieve and sustain the desired outcomes of CCs. Changing gender norms requires both women and men to be engaged continuously in the change processes (Wong et al., 2019) and has to be closely monitored to avoid unintended consequences. If such changes are to be qualified as empowering, the desired changes gained need to be sustainable, and the influences that have been achieved need to be retained in a lasting, durable way (Drydyk, 2008).

This study generated useful information on CC experience in Ethiopia in the context of research for a development program with valuable implications for the livestock sector. Nevertheless, limitations are evident in this study. The review procedure was based mainly on gray literature. The results reported were based on qualitative assessments, and were reported by program staff or affiliated partners and thus could be exposed to the problem of social-desirability bias on the part of staff and/or participants.

Conclusion

The Gender Transformative Approach by way of CCs in Livestock CRP was intended to address specific underlying constraining gender norms related to gender relations around gender roles, access, ownership, control, decision-making, and participation in collectives. These had been identified through preassessment and during CRP interventions. The CC discussion topics were appropriate as per the findings from this program of research and previous studies in the target areas. The subjects addressed are an interesting intersection between gender issues and everyday concerns about livestock production and livelihood generation. It is the CC that achieves this integration of interest and action. The key gender norms addressed so far were related to access, ownership, control over livestock resources, gender division of labor and their valuations, and the associated social structures. Similarly, undesired norms related to the use of ASFs and animal health management such as eating raw meat and drinking raw milk, and eating and treating diseased animals without gloves were part of the focus of the CCs.

This review has shown that CC interventions generated immediate impacts at individual, household, community, and institutional levels. The shift occurred in gender attitudes with respect to perceptions of access, ownership, control over livestock resources, and decision-making within households and communities. Increased women’s ownership of livestock allowed them to be eligible and registered members of breeding cooperatives. Relaxation of norms around the division of labor not only reduced women’s domestic burden but also helped them to engage in more valued activities such as taking part in local institutions that used to be men’s only associations. CC participants started adopting desired animal and product handling practices. Communities’ knowledge of animal welfare and desired practices increased. Tools of community engagement employed had spill-over effects beyond the household level, positively affecting community-level institutions. Bringing the desired KAP among community members along the important gender norms addressed would have tremendous implications for the improvement of the gender contexts in which the small ruminant value chain transformation program is taking place.

We recommend the following action points as a way forward. First, it is apparent that there is a need to identify related but unaddressed gender norms affecting women in livestock value chain development. The ongoing CC interventions in the target areas could be used as a means for the identification of unaddressed gender-related norms for future interventions. Second, we identified the need to continue to break down gender stereotypes through mechanisms that ensure the continuity of the effects of CC. Sustaining and scaling the desired behaviors reported within the household, community, and institution needs to continue, to break down gender stereotypes. In the short run, we recommend elevating women to positions of power, for example within the breeding cooperative leadership positions. Challenging the undermining of women’s autonomy is necessary, to break the chain of passing on these negative attitudes to future generations. Both the research and development partners in general and the public extension program run by district-level offices of agriculture, and the women, youth, and child affairs office in particular need to take up the initiatives as part of their routine development activities across the intervention areas.

Third, we recommend coordination with partners and the establishment of community-based gender advocacy groups across the intervention target sites. This could be started by organizing platforms for the recognition of champion men and women community members who successfully participated in the CC sessions, fully implemented action plans, and are able to demonstrate the desire to change gender attitudes and practices. The establishment of the advocacy group would maintain momentum and help to ensure the sustainability of the changes in KAP that were already observed among CC participants at individual, household, and community levels. Similarly, local-level government bodies and non-governmental organizations need to strengthen efforts by building innovation platforms and training provisions. More importantly, we suggest the importance of devising mechanisms for institutionalizing CC in the public extension systems. This could be facilitated more by generating robust objective evidence of the impacts that would pave the way for scaling locally, regionally, and nationally.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: CGSpace.org.

Author contributions

WK and ET conceptualized the idea. WK wrote the draft manuscript. ET, DB, and DN reviewed and contributed to the final analysis and writeup of the manuscript. WK, ET, DB, and DN agreed on the final appearance of the manuscript after careful review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of New England International Post Graduate Research Award Grant (UNE IPRA). We acknowledge financial support provided by the CGIAR Research Program (CRP) on Livestock, and all donors and organizations which globally support CGIAR research work through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. The work was further developed under the CGIAR SAPLING Initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of New England and ICARDA-Ethiopia office, particularly Barbara Ann Rischkowsky and Aynalem Haile for hosting the WK as a graduate fellow, and also acknowledge various individuals including farmers and program partners who were used as data sources for the knowledge products reviewed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^An integrated program of international agricultural research implemented by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

2. ^The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas.

3. ^International Livestock Research Institute.

4. ^Small Ruminant Value Chain Development.

6. ^The smallest administrative divisions in Ethiopia.

7. ^“an invigorated research agenda [… that] include: critical self-reflection and introspection among research [… team] on the norms they bring to the research process; partnerships with civil society and other organizations with long-term, trusted local presence; engagement with both women and men from different social groups on the structures and mindsets that hinder and enable equality and local people’s empowerment; sufficient time and resources to accompany a process of social change; and mechanisms to scale advances made using gender transformative approaches” (Badstue et al., 2020).

References

Aguilar, A., Carranza, E., Goldstein, M., Kilic, T., and Oseni, G. (2015). Decomposition of gender differentials in agricultural productivity in Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 46, 311–334. doi: 10.1111/agec.12167

Akresh, R., de Walque, D., and Kazianga, H. (2016). Evidence from a randomized evaluation of the household welfare impacts of conditional and unconditional cash transfers given to mothers or fathers. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7730.

Alemu, B., Desta, H., Kinati, W., Mulema, A. A., Gizaw, S., and Wieland, B. (2019). Application of mixed methods to identify small ruminant disease priorities in Ethiopia. Front. Vet. Sci. 6:417. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00417

Alemu, B., Lemma, M., Magnusson, U., Wieland, B., Mekonnen, M., and Mulema, A. (2019). Community conversations on antimicrobial use and resistance in livestock. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/106552

Andreoni, J., and Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. Q. J. Econ. 116, 293–312. doi: 10.1162/003355301556419

Asrat, A.G, and Getnet, T. (2012). Gender and farming in Ethiopia: an exploration of discourses and implications for policy and research. Future agricultures working paper 084.

Badstue, L., Elias, M., Kommerell, V., Petesch, P., Prain, G., Pyburn, R., et al. (2020). Making room for manoeuvre: addressing gender norms to strengthen the enabling environment for agricultural innovation. Dev. Pract. 30, 541–547. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2020.1757624

Baland, J.M., and Ziparo, R. (2017). Intra-household bargaining in poor countries. WIDER working paper 2017/108.

Barker, G., Ricardo, C., and Nascimento, M. (2007). Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: Evidence from programme interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/documents/Engaging_men_boys.pdf

Bayeh, E. (2016). The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pacific Sci. Rev. B. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psrb.2016.09.013

Belete, A.T., and Charmaz, K (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage

Benhassine, N., Florencia, D., Esther, D., Pascaline, D., and Victor, P. (2015). Turning a shove into a nudge? A "Labeled cash transfer" for education. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7, 86–125. doi: 10.1257/pol.20130225

Castilla, C., and Walker, T. (2013). Is ignorance bliss? The effect of asymmetric information between spouses on intra-household allocations. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 263–268. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.3.263

Cislaghi, B., and Heise, L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociol. Health Illn. 42, 407–422. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13008

Connell, R. (2011). “Masculinity research, hegemonic masculinity and global society” in Contribution to the Austrian Conference on Men, Graz, Austria.

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women's empowerment: what works? J. Int. Dev. 28, 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

Croson, R., and Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 47, 448–474. doi: 10.1257/jel.47.2.448

Deci, E. L., Robert, J. V., Pelletier, L. G., and Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: the self-determination perspective. Educ. Psychol. 26, 325–346. doi: 10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

Del Boca, D., and Flinn, C. (2012). Endogenous household interaction. J. Econ. 166, 49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2011.06.005

Deshmukh-Ranadive, J. (2005). “Gender, power, and empowerment: an analysis of household and family dynamics” in Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. ed. D. Narayan (Washington, DC: The World Bank)

Didana, A. C. (2019). Determinants of rural women economic empowerment in agricultural activities: the case of Damot Gale Woreda of Wolaita zone, SNNPRS of Ethiopia. J. Econom. Sustain. Dev. 10, 30–49. doi: 10.7176/jesd

Drucza, K., and Abebe, W. (2017). Gender transformative methodologies in Ethiopia’s agricultural sector: The annexes, CIMMYT-Ethiopia.

Elias, M., Elmirst, R., Ibraeva, G., Sijapati Basnett, B., Ablezova, M., and Siscawati, M. (2018). Understanding gendered innovation processes in Forestbased landscapes: Case studies from Indonesia and Kyrgyz Republic, GENNOVATE report to the CGIAR research program on forests, trees and agroforestry (FTA).

FAO, IFAD and WFP (2020). Gender transformative approaches for food security, improved nutrition and sustainable agriculture—a compendium of fifteen good practices, Rome.

FAO, IFAD and WFP (2022). Guide to formulating gendered social norms indicators in the context of food security and nutrition. Rome.

Flora, C., and Flora, J. (2008). Rural Communities: Legacy and Change (3rd Edn.). CO:Boulder: Westview Press

Galiè, A., Mulema, A. A., Mora Benard, M. A., Onzere, S. N., and Colverson, K. E. (2015). Exploring gender perceptions of resource ownership and their implications for food security among rural livestock owners in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua. Agric. Food Secur. 4:11. doi: 10.1186/s40066-015-0021-9

Gelfand, M. J., and Jackson, J. C. (2016). From one mind to many: the emerging science of cultural norms. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 8, 175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.11.002

Gueye, M., Diouf, D., Chaava, T., and Tiomkin, D. (2005). Community capacity enhancement handbook: The answer lies within. Leadership for results: UNDP’s response to HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS Group Bureau for Development Policy, United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Available at: http://www.undp.org/hiv/docs/prog_guides/cce_handbook.pdf.

Haider, H. (2017). Changing gender and social norms, attitudes and behaviors. K4D Helpdesk Research Report series. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK.

Haushofer, J., and Shapiro, J. (2017). The short-term impact of unconditional cash transfers to the poor: experimental evidence from Kenya. Q. J. Econ. 132, 2057–2060. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjx039

Helen Keller International (2011). Gender attitudes and practices survey: Nobo Jibon gender baseline. HKI, Dhaka.

Hoel, J. B. (2015). Heterogeneous households: a within-subject test of asymmetric information between spouses in Kenya. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 118, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2015.02.016

Hulela, K. (2010). The role of women in sheep and goats production in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Sci. Res. Educ. 3, 177–187.

Johnson, C. W. (2005). ‘The first step is the two-step’: hegemonic masculinity and dancing in a country-Western gay Bar. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 18, 445–464. doi: 10.1080/09518390500137626

Kabeer, N. (2017). Economic pathways to Women’s empowerment and active citizenship: what does the evidence from Bangladesh tell us? J. Dev. Stud. 53, 649–663. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2016.1205730

Kinati, W. (2017). Assessment of gendered participation in breeding cooperatives in CBBP target sites: gender relations, constraints and opportunities. CRP Livestock genetics flagship ICARDA report. ICARDA, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Kinati, W., Lemma, M, Demeke, Y, and Mulema, A. (2019b). Community conversations change gender perceptions in Amhara farmers’ groups. Available at: https://livestock.cgiar.org/news/community-conversations-change-gender-perceptions-amhara-farmers%E2%80%99-groups

Kinati, W., Lemma, M, Mulema, A, and Wieland, B (2019a). The role of community conversations in transforming gender relations and reducing zoonotic risks in the highlands of Ethiopia. Livestock Brief 6. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/102408

Kinati, W., and Mulema, A. A. (2016). “Community gender profiles across livestock production systems in Ethiopia: implications for intervention design” in Livestock and Fish Brief 11 (Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI)

Kinati, W., and Mulema, A. A. (2019). Gender issues in livestock production systems in Ethiopia: a literature review. Journal of. Livest. Sci. 10. doi: 10.33259/JLivestSci.2019.66-80

Kinati, W., Mulema, A., Desta, H., Alemu, B., and Wieland, B. (2018). Does participation of household members in small ruminant management activities vary by agro-ecologies and category of respondents? Evidence from rural Ethiopia. J. Gender Agric Food Security 3, 51–73. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.293599

KIT, Agri-Profocus, & IIRR (2012). Challenging Chains to Change: Gender Equity in Agricultural Value Chain Development. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam:KIT publishers

Kristjanson, P., Waters-Baye, A., Johnson, N., Tipilda, A., Njuki, J., Baltenweck, I., et al. (2010). Livestock and Women’s livelihoods: A review of the recent evidence. Discussion Paper No. 20, INTERNATIONAL LIVESTOCK RESEARCH INSTITUTE. Kovacevic (2021). Community conversations transform relationships between men and women to reduce livestock disease risk. Available at: https://livestock.cgiar.org/news/community-conversations-transform-relationships-between-men-and-women-reduce-livestock-disease

Kumar, N., and Quisumbing, A. R. (2015). Policy reform toward gender equality in Ethiopia: little by little the egg begins to walk. World Dev. 67, 406–423. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.029

LaMorte, W. W. (2022). The Transtheoretical model (stages of change). Boston University School of Public Health, Boston. Available at: https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/behavioralchangetheories6.html#headingtaglink_1

Laven, A. (2010). The Risks of Inclusion: Shifts in Governance Processes and Upgrading Opportunities for Cocoa Farmers in Ghana. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers

Legovini, A. (2006). “Measuring Women's empowerment and the impact of Ethiopias Women's development initiatives project” in Empowerment in Practice: From Analysis to Implementation. Eds. R. Alsop, M. Bertelsen, and J. Holland (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Lemma, M., Alemu, B, Gizaw, S, Desta, H, Alemayehu, G, Mekonnen, M, et al. (2021b). Community conversations on community-based gastrointestinal parasite control in small ruminants. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya.

Lemma, M., Alemu, B., Mekonnen, M., and Wieland, B. (2019b). Community conversations on antimicrobial use and resistance. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/106395

Lemma, M., Alemu, B, Mekonnen, M, and Wieland, B (2019f). Increasing antimicrobial resistance awareness through community conversations: Available at: https://amr.cgiar.org/blog/increasing-antimicrobial-resistace-awareness-through-community-converations

Lemma, M., Kinati, W, Bassa, Z, Mekonnen, M, and Demeke, Y (2018b). Report on community conversations about transmission and control of zoonotic diseases. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/99378

Lemma, M., Kinati, W, Mulema, A, Alemu, B, Mekonnen, M, and Wieland, B (2019e). Facilitating collaborative learning and action in animal health management through community conversations. Available at: https://livestock.cgiar.org/news/facilitating-collaborative-learning

Lemma, M., Kinati, W, Mulema, A, Bassa, Z, Tigabie, A, Desta, H, et al. (2018a). Report of community conversations about gender roles in livestock. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/99316

Lemma, M., Kinati, W, Mulema, A, Mekonnen, M, and Demeke, Y (2018c). Community conversations reduce the risk of exposure to zoonotic diseases in the Ethiopian highlands. Available at: https://livestock.cgiar.org/2019/01/18/community-conversations-zoonotic-diseases/

Lemma, M., Kinati, W., Mulema, A., Mekonnen, M., and Wieland, B. (2019c). Community conversations: A community-based approach to transform gender relations and reduce zoonotic disease risks. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/105818

Lemma, M., Mekonnen, M., Kumbe, A., Demeke, Y., Wieland, B., and Doyle, R. (2019a). Community conversations on animal welfare. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya.

Lemma, M., Mekonnen, M., and Tigabie, A. (2021c). Community conversations: An approach for collaborative learning and action in animal health management. Practice brief. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/113640

Lemma, M., Mekonnen, M, Wieland, B, Mulema, A, and Kinati, W (2019g). Community conversation facilitators training workshop: Training material and facilitation guide. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/107025

Lemma, M., Mulema, A, Demeke, Y, and Kinati, W (2019d). Community conversations increase women’s access to farming information in the Ethiopian highlands: Available at: https://livestock.cgiar.org/news/community-conversations-increase-women%E2%80%99s-access-farming-information-ethiopian-highlands

Lemma, M., Mulema, A., Kinati, W., Mekonnen, M., and Wieland, B. (2020a). Gender responsive community conversations to transform animal health management. Virtual Livestock CRP planning meeting, 8-17 2020. Poster. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://www.ilri.org/publications/gender-responsive-community-conversations-transform-animal-health-management

Lemma, M., Mulema, A., Kinati, W., Mekonnen, M., and Wieland, B. (2020b). A guide to integrate community conversation in extension for gender-responsive animal health management. ILRI,Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/110398

Lemma, M., Mulema, A, Kinati, W, and Wieland, B. (2018d). Transforming gender relations and reducing risk of zoonotic diseases among small ruminant farmers in the highlands of Ethiopia: A guide for community conversation facilitators. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/99264

Lemma, M, and Tigabe, A. (2021). A report of monitoring and coaching partners on community conversation implementation and uptake. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya.

Lemma, M., Tigabie, A, Wamatu, J, Mekonnen, M, Zeleke, M, and Wieland, B (2021a). Community conversations on animal feeds, animal health and collective livestock marketing. ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/113561

Leulsegged, K., Gashaw, T.A., Warner, J., and Kieran, C. (2015). “Patterns of agricultural production among male and female holders: evidence from agricultural sample surveys in Ethiopia” in Research for Ethiopia’s Agriculture Policy (REAP): Analytical Support for the Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). IFPRI, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Mackie, G., and Lejeune, J. (2009) Social dynamics of abandonment of harmful practices: a new look at the theory in Special series on social norms and harmful practices. (ed.) UNICEF, Florence: Innocenti Research Centre.

Mackie, G., Moneti, F., Shakya, H., and Denny, E. (2015) What are social norms? How are they measured? UNICEF and UCSD, New York.

Mani, M.A. (2011). Yours or ours? The efficiency of household investment decisions: An experimental approach, CAGE online working paper series, 64, competitive advantage in the global economy.

Marcu, P. (2014). Changing discriminatory norms affecting adolescent girls through communications activities: Insights for policy and practice from an evidence review, Overseas Development Institute, London, UK.

Markel, E., Gettliffe, E., Jones, L., Miller, E., and Kim, L. (2016) Policy brief: The social norms factor. The BEAM Exchange.

Mekonnen, M., Lemma, M, Tigabie, A, Nane, T, Arke, A, and Wieland, B (2021). Report of community conversations on animal health management. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

Mulema, A. A. (2018). Understanding women’s empowerment: A qualitative study for the UN joint programme on accelerating Progress toward the economic empowerment of rural women conducted in Adami Tulu and Yaya Gulele woredas, Ethiopia. ILRI project report. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/95857

Mulema, A. A., Kinati, W., Lemma, M., Mekonnen, M., Alemu, B. G., Elias, B., et al. (2020). Clapping with two hands: transforming gender relations and zoonotic disease risks through community conversations in rural Ethiopia. Hum. Ecol. 48, 651–663. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00184-y

Mulema, A.M., Kinati, W., Lemma, M., Mekonnen, M., Alemu, B.G., Elias, B., et al. (2021). Transforming gender relations and zoonotic disease risks through community conversations in rural Ethiopia. CGIAR international year of plant health webinar on integrated Pest and disease management, 2021. Available at: https://wwakjira/Dropbox/My%20PC%20(ITD-6QGW633)/Desktop/ConsultancyWork/Dr%20Aynalem’s%20Work/Papers/iyph_webinar3_mulema.pdf

Mulema, A., Lemma, M., Kinati, W., Mekonen, M., Demeke, Y., and Wieland, B. (2019a). Community conversations on social structures and institutions that shape women’s control of livestock, group membership and access to information in Menz and Doyogena: Field activity report. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/105615

Mulema, A., Lemma, M., Kinati, W., Mekonnen, M., Demeke, Y., and Wieland, B. (2019b). Going to scale with community conversations in the highlands of Ethiopia. Nairobi, Keny:ILRI. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/105817

Murphy-Graham, E. (2010). And when she comes home? Education and women’s empowerment in intimate relationships. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 30, 320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.09.004

Muthengi, E., and Erulkar, A. (2011). Delaying early marriage among disadvantaged rural girls in Amhara, Ethiopia, through social support, education, and community awareness. Promoting healthy, safe, and productive transitions to adulthood series. Brief No 20. The Population Council.

Pearse, R., and Connell, R. (2016). Gender norms and the economy: insights from social research. Fem. Econ. 22, 30–53. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1078485

Ragasa, C., Berhane, G., Tadesse, F, and Seyoum, A. (2012). Gender differences in access to extension services and agricultural productivity. ESSP Working Paper 49.

Randolph, J. (2009). A guide to writing the dissertation literature review. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 14:13. doi: 10.7275/b0az-8t74

Ricardo, C., Eads, M., and Barker, G. (2011). Engaging boys and young men in the prevention of sexual violence: A systematic and global review of evaluated interventions. Sexual violence research initiative and Promundo. Available at: http://www.svri.org/menandboys.pdf

Ridgeway, C. L., and Correll, S. J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspectives on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender & Society 18, 510–531. doi: 10.1177/0891243204265269