95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 13 June 2023

Sec. Land, Livelihoods and Food Security

Volume 7 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1123802

This article is part of the Research Topic Leveraging Gender, Youth and Social Networks for Inclusive and Transformative Livestock Production in the Tropics and Subtropics View all 14 articles

Mulukanoor Women’s Dairy Cooperative (Mulukanoor Dairy) in India has been run by women for women since 2002. From the beginning it created strategies to empower women members, including mixing milk provided by the marginalized caste with milk from other castes; paying women exclusively for milk; providing technical training to women; and seating women together in training and governance events. Caste norms are not observed in these interactions. This article examines the effectiveness of Mulukanoor Dairy’s strategies for overcoming gender and caste disadvantage through empirical research. We hypothesized that if women members of Mulukanoor Dairy had become empowered over the past 20 years we should be able to see evidence for this in the form of women’s empowerment in relation to dairy decision-making at intra-household level. And if caste divisions had been largely overcome we should observe collegial relationships among women of different castes, and similar levels of women’s empowerment at intra-household level regardless of caste. Research was carried out in four villages provisioning Mulukanoor Dairy through focus group discussions with women members of Mulukanoor Dairy, and men spouses of different women members. In total 21 women and 23 men participated. FGDs were sex-and caste disaggregated. The introduction of a new sorghum forage, CoFS-29, provided the entry point to start talking about gender and caste norms. The findings show a remarkable transition of the dairy industry from elite non-marginalized caste men to marginalized and non-marginalized women. Caste norms have changed within the safe space of Mulukanoor Dairy and to a limited extent in the community. A new norm has been instituted that marginalized caste women are dairy farmers. Women across caste experience considerable decision-making power over milk and dairy income. However, men remain primary decision-makers over whether forage is grown. Men engage with key dairy chain actors. Knowledge on new technologies is passed only within castes, and mostly between persons of the same gender. Over the process of knowledge transmission, knowledge networks become increasingly masculinized. Knowledge networks are stronger among non-marginalized men who are best able to make use of new technologies.

Feminist activists in the Global South were prominent in attempts to define and enact women’s empowerment from the 1970s to mid-1990s and beyond. Batliwala (2007) describes how Global South activists fought for radical societal transformations through mass mobilization and seeking policy change. Activists worked, from the start, with intersectionality. “The spread of “women’s empowerment” [was] a […] political and transformatory idea for struggles that challenged not only patriarchy, but the mediating structures of class, race, ethnicity—and, in India, caste and religion—which determined the nature of women’s position and condition in developing societies” (Batliwala (2007), p. 558). Conceptual links between women’s self-understanding, their capacity for self-expression, and women’s access to resources were developed and various manifestations of power were developed and described (Kabeer, 1999; Cornwall and Rivas, 2015; Cornwall, 2016).

Yet moving into the 2000s progress was uneven. In some cases, the terms “empowerment” and “gender equality” were depoliticized through top-down gender mainstreaming processes, thereby becoming “eviscerated of conceptual and political bite” (Cornwall and Rivas, 2015, p. 396). Although there have been enormous achievements, including Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 on gender equality, and other high level policy commitments, a substantial body of development work on gender equality and women’s empowerment has become instrumentalist, focusing more on what empowered women can do for achieving desirable development goals rather than on building an understanding and supporting of women’s empowerment as an end in itself (Cornwall, 2016). Today, the achievement of women’s empowerment and gender equality can seem as far away as ever (Whitelaw, 2022).

In the Global South, though, some organizations took on the mantle of women’s empowerment and have been articulating it ever since in their praxis. Mulukanoor Women’s Dairy Cooperative in Warangal, Telangana, India (henceforth Mulukanoor Dairy) is an example. Founded in 2002 it has been run by women for women with an explicit rural women’s empowerment agenda ever since.1 Mulukanoor Dairy was established when women’s self-help groups (SHG) approached the Mulukanoor Cooperative Rural Banking and Marketing Society Ltd. to seek advice on how to invest the substantial funds that had been accumulating in SHGs over the years. The bank advised investing in the dairy industry as this was considered to hold significant potential (Swamy et al., 2014). The National Dairy Development Board agreed to provide technical support to set up the new cooperative’s dairy processing plant. Villages wishing to join Mulukanoor Dairy had to commit to selling solely to Mulukanoor Dairy through dedicated Mulukanoor village dairy societies (the incentive being that Mulukanoor Dairy pays above the market rate) and villages had to agree to exclusive women membership. By 31st March 2020, Mulukanoor Dairy was operating in 192 member villages with 22,605 women members.

Studies of Indian dairy cooperatives (Dohmwirth and Hanisch, 2017; Christie and Chebrolu, 2020; Dohmwirth and Liu, 2020), provide a mixed picture regarding their ability to strengthen women’s empowerment. Some evidence suggests that well-intentioned, top-down interventions aimed at empowering women by instituting women-only dairy cooperatives nevertheless have limited potential to empower women if they do not actively challenge gender and caste norms. For instance, cooperative bylaws, intended to guarantee caste and gender equality, are not necessarily transformative in themselves (Stuart, 2007; Basu and Chakraborty, 2008; Ravichandran et al., 2021). Women leaders may be appointed yet men may rule behind the scenes through directing the decision-making of women leaders (Ravichandran et al., 2021). Sometimes, women’s dairy cooperatives are imposed on villages resulting in increased work yet weak benefits to women due to insufficient effort paid to getting the whole community enthused about the goals of the cooperative (Dohmwirth and Hanisch, 2017). Nevertheless, this experience is not uniform. Some women-only dairy cooperatives strengthen women’s social networks and capacity development, and provide a route to genuine women’s leadership (Dohmwirth and Liu, 2020).

Prior to the establishment of Mulukanoor Dairy, women and men tended buffalo and cows, but men sold morning milk to private sector milk vendors and kept the income. Women used evening milk to make curd and ghee. As shown in Figure 1 non-marginalized caste farming men dominated the industry and owned almost all dairy livestock. Caste norms meant there was no commercial market for milk from the marginalized caste as their milk was considered untouchable.

Mulukanoor Dairy entered this fraught terrain by developing several strategies for women’s empowerment (Ravichandran, 2018; Ravichandran et al., 2021). They are grouped below in relation to their primary objective.

Women farmers across caste are offered technical training on livestock care and milk handling at headquarters and village level.

At the governance level, board members at headquarters, and in village dairy societies are women—unless there is a male secretary (which is relatively common) at the latter. Women from any caste can stand for election.

Payments are made fortnightly in cash in women’s names. Husbands are permitted to collect these payments and must provide them to their wives. Women receive two annual bonuses, a dairy and a society bonus. The size of bonus received depends on how much milk the members of a dairy society have provided.

Milk from all castes is mixed—“poured”—together, thus removing untouchability from milk produced by the marginalized caste. This allows marginalized women—who previously could not join the milk value chain—to become dairy chain actors.

Women across caste are seated and eat together at Mulukanoor events.

The membership of Indian SHGs is typically caste-based. However, since the founding members of Mulukanoor Dairy came from different SHGs—along with their funds—membership was opened to all. Marginalized caste women could thus insist that their milk be poured together with that of non-marginalized women, and they could expect to join meetings, and participate in governance, as equals.

In this study we explored whether women members of Mulukanoor were able to improve gender-based power dynamics in the household, and caste-based power dynamics in their community, and how. To help explore changes in gender and caste dynamics at Mulukanoor Dairy, we used the introduction of a new forage, CoFS-29—an improved multi-cut perennial sorghum, as an entry point to start talking about locally prevalent gender and caste norms and whether they had changed over the past 20 years. CoFS-29 was introduced, in partnership with the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) by Mulukanoor Dairy in 2017 to increase milk productivity. A lack of green forage represents one of the most critical constraints to improving dairy production in India (Singh et al., 2022). CoFS-29 has high levels of crude protein thereby contributing to higher levels of milk production and consequent income and other benefits. CoFS-29 is sweet, does not need a chaff cutter and there is little wastage (Blümmel, 2017; Ravichandran et al., 2019).

Our conceptual framework engages with the concepts of intersectionality (in the form of caste and gender), power, and gender-transformative change. When conceptualizing this study, we were interested in understanding how gender and caste identities influence each other, and how they combine to influence women’s ability to empower themselves. To understand these issues, we took the stance that it was important to test these concepts in a real-life situation. For this, qualitative empirical work was considered necessary. We further decided it was important to ensure that research participants were able to contribute their thoughts on these large topics effectively. We therefore designed research instruments – primarily focus group discussion (FGD) schedules, and key informant interview (KII) questionnaires – around the everyday lives of our women and men participants.

The “real-life” situation we chose was whether the efforts made by Mulukanoor Dairy to change caste and gender dynamics through various initiatives is indeed contributing to changes in these dynamics. We hypothesized that if women members of Mulukanoor Dairy had become empowered over the past 20 years, we should be able to see evidence for this in the form of women’s empowerment (or more equitable gender relations) in various aspects of dairy decision-making at household level. And secondly, if caste divisions had been largely overcome, we should be able to see forms of collegial relationships among women of different castes in the community, for instance through knowledge sharing.

A clear starting point against which our hypotheses could be tested was necessary. We therefore selected the introduction of CoFS-29 4 years prior to our research (conducted in 2021). Our rationale was that technological innovations such as new types of forage are not neutral in their effects. They interact with locally prevalent gender, caste and other norms to influence who accesses, utilizes and benefits from them (Theis et al., 2018). Our starting point enabled us to frame questions to Mulukanoor Dairy women members, and their male spouses, around their experience of adoption and how—and if—this affected gender and caste dynamics in their everyday lives. Our research questions were:

1) Changes in gender relations at intra-household level.

• RQ1a. Are gender dynamics in intra-household dairy management changing?

• RQ1b. Are there differences in intra-HH gender dynamics by caste?

• Topics of enquiry. (i) changes in the gender division of labor in dairy, (ii) Milk allocation decisions, and (iii) Milk expenditure decisions.

2) Changes in caste relations at village level.

• RQ2. Are caste dynamics among women and men belonging to different castes changing?

• Topic of enquiry. (i) CoFS-29 information exchange between castes.

On the basis of the research questions, questions on each of the topics were developed, and discussed in focus group discussions (FGDs) with women and men in sex-and caste disaggregated groups, as detailed in the methods section. We now discuss the three core elements of our conceptual framework in a little more detail.

Gender is a social characteristic that shapes systems of power across all cultures based on perceptions around male and female identities. Gender is a primary means of making sense of who we are in relation to the others, before considering ethnic, age, class, or other social markers, and is therefore a key organizing principle in most societies (Ridgeway and Correll, 2004). Gender norms are comprised of informal rules and social expectations which determine, assign and regulate—through the application of social sanctions—acceptable roles, behaviors, and responsibilities to male and female identities in particular communities and geographies (FAO, IFAD, and WFP, 2022). Gender norms directly, and differentially, affect the choices, freedoms and capabilities of women and men in the arenas in which they live their lives: at home, in the field, in organizations and community settings, the marketplace, and others.

Gender-transformative change aims to encourage critical awareness among men and women of gender norms (McDougall et al., 2021). Transformative approaches challenge the distribution of resources and allocation of duties between men and women, address unequal power relationships between women and men, and embrace intersectional understandings (Kleiber et al., 2019; MacArthur et al., 2022). They identify and tackle the structural root causes of entrenched gender inequalities at multiple scales, including gender norms and roles, rather than merely responding to the symptoms of gender inequality (CGIAR, 2017; Farhall and Rickards, 2021; Farnworth et al., 2021). While the concept of gender-transformative change has been central in gender discourses for a decade, less is understood about how gender-transformative approaches contribute to the achievement of gender-transformative change.

Feminist scholars and social justice advocates have long sought to integrate intersectionality: the recognition that there are multiple intersecting and overlapping forms of social difference, tied to structures of privilege and inequality—into research and action (Keddie et al., 2022). “Human lives cannot be explained by taking into account single categories, such as gender, race, and socio-economic status. People’s lives are multi-dimensional and complex. Lived realities are shaped by different factors and social dynamics operating together” (Hankivsky, 2014, p. 3). Intersectional research focuses less on the individual characteristics of people (their race, class, caste, gender, age, etc.) but rather on how structural processes (racism, classism, casteism, patriarchy, ageism, etc.) combine to create and perpetuate intersectional inequalities (MacArthur et al., 2022, p. 8). The power dynamics behind processes which privilege or denigrate specific intersectional identities need to be understood and interrogated (Tavenner et al., 2022). Different forms of intersectionality can layer disadvantage upon disadvantage resulting in multi-faceted discrimination (Kabeer, 2016).

Our intersectional focus is caste together with gender. Caste is a Hindu system of ordered inequality in status built around concepts of superiority and purity (Bidner and Eswaran, 2015; Mudliar and Koontz, 2018). “Caste membership has been ingrained into Indian society and has remained one of the most salient identities in the country” (Surendran-Padmaja et al., 2023, p. 2). Caste identity tends to have negative implications for the well-being of marginalized castes (Surendran-Padmaja et al., 2023) Officially these castes are termed Scheduled Castes (SCs, also Dalits). Indigenous (Adivasi) people are categorized as Scheduled Tribes (STs) and are similarly marginalized. There are two non-marginalized castes. The General Caste (GC) are understood to be the highest caste. They are followed by the mid-level Other Backward Castes (OBCs). The OBCs vary in the degree of their advantage and disadvantage. Overall, the non-marginalized castes feel belongness and self-esteem (Surendran-Padmaja et al., 2023, p. 2). Sankaran et al. (2017) suggest that “high caste norms are associated with moral values while the lower caste norms are associated with immorality.”

Thousands of sub-castes exist within each caste, and each caste/sub-caste has, to some extent, its own social norms and traditions. These shape, among other things, men’s and women’s roles, responsibilities, benefits, and agency (Lamb, 2013). Caste norms frequently prohibit mixing between castes, particularly with the SC to whom norms of untouchability frequently (despite government prohibition) apply in everyday life, including eating or drinking with non-marginalized castes (Mudliar and Koontz, 2018). People who breach caste norms can be severely penalized (Sankaran et al., 2017). In this article, we mostly use the term non-marginalized to refer to GC/OBC castes, and marginalized to refer to SC/ST. The abbreviations are only used if specific data is disaggregated further by caste.

We need to understand how power operates if we are to examine how processes of change associated with Mulukanoor Dairy’s empowerment strategies have unfolded. Here, we describe six forms of power.

First, Power within (Rowlands, 1997) is considered the starting point of empowerment processes. It describes a transformation in individual consciousness which leads to a sense of dignity, self-esteem, and self-confidence. A woman becomes aware of her situation and wants to change it (VeneKlasen and Miller, 2002).

Second, power to act expresses the ability to exercise agency. It is the power to do something to bring about a desired outcome (Allen, 1999).

However, women’s power within and power to act can be denied. The third concept of power—power over—is widely used to describe a negative state with actors on one side holding much more power than actors on the other side (Pansardi, 2012). Readily discernible negative forms of power over include situations whereby men determine which household resources a woman is permitted to use, such as land or machinery, or in decision-making, for example how (and if) women are to spend money they have earned (Sen, 1990). Power over can also describe a situation whereby a dominant group (defined by their ethnicity, class, caste or other intersectional identities) exercise more power over resources and decision-making, for example in organizations or in community decision-making bodies—than a less powerful group. Our starting point is that men are more likely to have power over women, and that non-marginalized castes are more likely to have power over marginalized castes.

The concept of power over is not always negative, though. Chambers (2006) concept of the power to empower, our fourth form of power, suggests that powerful actors can use their power over less powerful actors to positively to create situations and provide spaces which people can exploit to empower themselves (ibid.). Our case study is premised on the idea that Mulukanoor Dairy, as a dairy cooperative, has the power to empower women dairy farmers across caste. They can do this through creating “opportunity spaces,” such as training events and elections, within which women can come together to learn and to share (Sumberg and Sumberg and Okali, 2013). We posit that women members of Mulukanoor, regardless of their intersectional identity, can use these opportunities to strengthen their power as individuals and as groups.

Fifth, power with describe forms of power which emerge through processes of collective action for empowerment such as in women’s movements (Gammage et al., 2016). In the case of Mulukanoor, we speculate whether women member have developed a sense of power with that transcends caste boundaries.

Sixth, power through suggests that an individual’s power can be lost, or won, through a change in the empowerment status of others closely associated with that individual (Galiè and Farnworth, 2019). An individual may become empowered through their association with powerful people, for example through being born into a wealthy family in the community. In this, they may benefit from power over others in the community, even though they themselves have never deliberately or even consciously enacted this power. They may benefit through having more choices in their lives—as a consequence of experiencing a good education in childhood for instance—through no effort of their own. Conversely, a woman (or man) could be disempowered simply as a consequence of being born into a less powerful group in society. In both cases, the empowerment or disempowerment involved is involuntary. The concept of power through has particular relevance in the context of caste since caste is an inherited structure with associated privileges.

This study is qualitative. In 2021 a woman gender expert from India (and co-author) conducted 12 FGDs with a total of 21 women and 23 men. She was acquainted with Mulukanoor as she had previously conducted research with its members. A qualitative small-N study was considered the most appropriate approach to explore in great depth the views and lived experiences of women and men associated with Mulukanoor vis-à-vis changes in gender and caste dynamics (Crouch and McKenzie, 2006; Mahoney and Goertz, 2006). The data produced during the FGDs was translated into English and coded utilizing both a deductive and inductive approach: some codes were pre-determined based on the issues that the authors wanted to explore. New codes were added as they emerged from the data. The authors identified patterns of changes in gender and caste dynamics in the data, and, also, changes that were not experienced by other respondents. All are reported in the Findings. The study received ethical approval in October 2021: ILRI-IREC2021-46.

The section below provides an overview of the study sites and the introduction of CoFS-29. This is followed by details of respondent selection and the research tools. We then share the findings under the two main research questions on changes in gender relations in the household, and changes in caste relations in the villages.

Mulukanoor Dairy and its member villages are situated around 100 km from Hyderabad. Key crops include rice, cotton, maize, and sorghum. Landholdings tend to be small (less than two hectares), and irrigation is available only to a few, mostly among the non-marginalized caste. In general, marginalized castes do not grow fodder due to the poor quality of their land which is either non-irrigated or marshy making it unsuitable for fodder. They thus buy fodder or graze their livestock along paths and in common grazing areas. Marginalized castes typically do not have sufficient crop surplus for sale: paddy is cultivated during the rainy season with most retained for home consumption. Marginalized men work as day laborer’s on the farms of non-marginalized households, and they also work on government schemes—as do marginalized women—which guarantee employment, such as road and pond construction. In contrast, non-marginalized castes rely less on farming as a primary livelihood. Non-marginalized men work in service occupations such as teaching. Although non-marginalized women are usually educated, men are much more likely to obtain off-farm work in service occupations in this region.

Mulukanoor Dairy has been experimenting with various forages, including CoFS-29, for several years to boost dairy cow productivity and improve milk quality. The process of obtaining forage seed is as follows. Secretaries in Mulukanoor Dairy village diary societies are charged with providing information about CoFS-29 (as with other technologies) to members. They send requests for seed to Mulukanoor Dairy headquarters which then passes seed back to the village secretary for distribution. Table 1 shows that non-marginalized caste members received more seed than marginalized caste members. The rather low overall figures are reflective of the fact that most village secretaries refer interested farmers to other farmers growing CoFS-29 to obtain their seeds informally. These transactions are not recorded by Mulukanoor Dairy.

Mulukanoor Dairy holds details of its members by village, caste, and by technology adoption. These rosters were used to select respondents. First, four villages were selected from the roster. The selection criteria were (i) villages have been offered CoFS-29 through the village dairy society, (ii) villages include enclaves/ hamlets with marginalized and non-marginalized caste members, and (iii) villages have not been subjected to any other surveys over the past 5 years to avoid respondent fatigue. The four villages are shown in Table 2.

Once the villages had been selected, FGD participants were selected. The criteria were: (i) respondents have adopted CoFS-29, and (ii) 50% of participants should be members of marginalized castes and 50% of participants should be members of non-marginalized castes. In a further step, gender balance was sought within each caste, with (iii) 50% women members, and (iv) 50% men married to women members. Regarding the latter, male spouses had to come from different households to those of selected Mulukanoor Dairy women members. In total 21 women and 23 men participated. Some respondents participated across all three FGDs. Their participation depended on their availability and personal interest.

Three FGD discussion guides were developed to cover the research questions. As a reminder, they are.

1. Changes in gender relations at intra-household level. RQ1a. Are there new gender dynamics in intra-household dairy management? RQ1b. Are there differences in intra-HH gender dynamics by caste? The topics of enquiry are: (i) changes in the gender division of labor, (ii) Milk allocation decisions, and (iii) Milk expenditure decisions.

2. Changes in caste relations at village level. RQ2. Are there changes in caste dynamics among women and men belonging to different castes? The topic of enquiry is (i) CoFS-29 information exchange between castes.

The topic guides focused on (i) changes in caste dynamics at village level, (ii) changes in gender dynamics in intra-household dairy management, and (iii) changes in intra-household decision-making. Each FGD discussion guide covered the relevant domains of enquiry, and they allowed for triangulation by asking some of the same questions. The guides allowed for additional probing by the facilitator should new relevant information emerge. In each discussion guide, questions were asked about the situation in relation to the discussion topic prior to the establishment of Mulukanoor Dairy, and changes over the past few years. With respect to research question 2, respondents were asked to draw simple diagrams showing who they shared knowledge about CoFS-29 with by caste and gender. They were then asked to explain their diagrams. Each FGD took around 60–90 min. A total of 12 FGDs were conducted with 22 women and 23 men. Some participants joined more than one FGD (Table 3).

We start the Findings by providing descriptive statistics. We abbreviate the sources of direct citations to improve readability. Non-marginalized men are abbreviated to NMM, non-marginalized women to NMW, marginalized men to MM, marginalized women to MW, and village is abbreviated to V.

Marginalized and non-marginalized castes occupy separate enclaves within each study village with marginalized castes living further from the center. Non-marginalized castes in the four villages dominate Mulukanoor Dairy membership (76%) with marginalized castes representing about one quarter (24%) of members. Across all four villages, two fifths of households are members (39%). Table 4 provides an overview of membership by overall caste (marginalized and non-marginalized) and then by caste affiliation within these categories.

Table 5 provides some descriptive statistics about the respondents. Broadly, the data show that non-marginalized respondents have experienced more formal schooling, and for longer, than marginalized respondents. Around two thirds of marginalized respondents have not been to school compared to one third of non-marginalized respondents. Men have received more formal education than women across marginalized and non-marginalized respondents.

Table 6 provides details of respondent livestock and land-holdings.

Table 6 shows that households are quite large. Among the respondents the number of people living in a household ranged from 2 to 9 people (non-marginalized caste) and 2 to 6 people (marginalized caste). Nearly half of non-marginalized respondent households own both dairy cows and buffaloes whereas only one marginalized community household owns both. Marginalized households are more likely to own buffalo than non-marginalized households because they typically rely on bunds or communal land for grazing. Buffalos are better suited to the climate, particularly in summer, can walk longer distances, and can tolerate poorer quality fodder than dairy cows. These are generally cross-bred and suffer heat stress.

Households with larger holdings are better able to host more livestock. The data show that non-marginalized households hold an average of 5.8 acres (range between households 0–22) whereas marginalized farmers hold on average 2.8 acres (median 1 acre). Marginalized households (all in our sample grew forage as this was part of the sampling frame) grow forage on a relatively larger proportion of their land, but the amount of land they can allocate is smaller in size than for the non-marginalized households since food production for the household must take precedence.

Table 7 provides of adoption by overall caste (marginalized and non-marginalized) and then by caste affiliation within these categories. Across the four village study sites, 51 GC women, 61 OBC women, 31 SC women and 8 ST women had adopted the CoFS-29 forage variety by October 2021. Only a few ST households were members of Mulukanoor Dairy. Of these 8 out of 20 members adopted CoFS 29 forage.

Respondents reported strong increases in milk yield as a consequence of adopting CoFS-29, estimating yield improvements of between 10 and 20% for cows and 5–15% for buffaloes.

We now discuss evidence for empowerment according to the two research questions set out at the beginning of this article.

The first question was as follows: Changes in gender relations at intra-household level. RQ1a. Are gender dynamics in intra-household dairy management changing? RQ1b. Are there differences in intra-HH gender dynamics by caste? The topics of enquiry are (i) changes in the gender division of labor in dairy, (ii) Milk allocation decisions, and (iii) Milk expenditure decisions.

Marginalized and non-marginalized women are normatively responsible for most tasks associated with livestock care. Although the gender division of labor allocates a substantial burden to women, non-marginalized women argue that, overall, they work less than non-marginalized women because many of them employ laborer’s to take care of livestock. Moreover, across caste, men’s workloads regarding the care of dairy animals (feeding, grazing, watering, milking and health care) appears to be increasing. This is because livestock are now housed, due to government health regulations aiming to minimize the risk of zoonotic disease, on fields at some distance from the homestead. Mobility norms which restrict women’s movements, and their widely recognized responsibility for household tasks, mean that men are under pressure to take on livestock care.

Furthermore, men rather than women interact with market actors and knowledge agents. “Decisions regarding purchase of feed from the market, animal purchase and calling the veterinarian or inseminator are done by men. Cleaning the cow shed, feeding the animals, taking care of the sick animals, and forage cutting is carried out by women” (NMM FGD, V3). This role is not contested. One woman explained, “We do not have conflicts about this because he has more knowledge and travels outside” (NMW FGD, V1).

Across caste gender norms previously stipulated that milk should be provided to men for men’s personal consumption or sale. This norm has been transformed. Men no longer participate in decision-making around the allocation of milk between household members, or between how much milk is allocated for consumption and sale. These decisions are now perceived as for women to make.

Today, women provide milk to children and elderly household members before providing milk to adults. Milk is widely understood to promote children’s health, and “all girls get equal preference with boys in the families” (NMM FGD, V3). This contrasts with the past when boys were favored. One man reported, “Twenty years ago my mother gave milk to working men and then to other adults, but now the scenario has changed. Women give milk to children first” (NMM FGD, V3). Marginalized women used almost the same words and explained that men were previously given milk to drink because milk is thought to build strength, important since marginalized men had to earn money through physical labor. Today, due to reductions in extreme poverty everyone drinks some milk with adults consuming small quantities in tea.

Dairy income has allowed some marginalized women to improve household nutrition through enabling them to buy other animal source foods with their own money. Women explained they cannot ask men for money to purchase meat or eggs. One woman reported, “Many households used to eat meat once or twice a year during festivals 25 years ago. Now, some eat meat every weekend because women can decide on household food due to dairy income” (MW FGD, V3).

The findings show significant changes beyond the household. Whereas men normatively take expenditure decisions associated with transactions in public spaces, and women take expenditure decisions associated with the home, the influence of Mulukanoor Dairy is changing—and enlarging—these boundaries for women to grant them more influence over decisions outside the home. Marginalized men explained that “After the women dairy cooperatives came up, women started taking decisions on the purchase of dairy animals to increase dairy income. (To do this) she gets money from her women SHG. Men go to the market and purchase animals.” This man added that “Women’s contribution within the household is to decide on number of animals to be added, how much milk to keep for household consumption, etc. Decisions related to outside work like feed purchase, animal purchase, getting veterinary help, or breeding are made by men” (MM FGD, V2).

Even though marginalized women are now taking key decisions around spending on dairy livestock, some marginalized men try to defend their continued dominance of key expenditure decisions associated with dairy. This dominance is justified by referring to the low levels of education among marginalized women. One marginalized man said, “My wife does not have any knowledge on breeding or animal health. She does not know anyone who provide these services, so I take all decisions” (MM FGD, V2). A marginalized women explained, “Men are head of household, they often go outside and gain more knowledge so they take all decisions” (MW FGD, V3). These claims are surprising because Mulukanoor Dairy has spent the past two decades offering technical training to women.

Indeed, marginalized women and men shared a perception that non-marginalized caste women are more likely to participate in training and to be listened to at home because the latter have been formally educated. This is believed to have knock-on effects on their ability to absorb the lessons from technical training events. Marginalized women explained that, “Non-marginalized women learn quicker and faster than marginalized women. And their men share more than our men” whilst another marginalized woman added nuance by suggesting that marginalized men “think women are less knowledgeable, so women have to learn for themselves which is not the same in the higher caste. Their women are rich and they get a good education as well” (MW FGD, V3). Marginalized men agreed with this analysis arguing that because non-marginalized women are educated “they have some contribution to make within the home to suggest allocating land for forage.” These men added that the very limited size of their lands resulted in a limited range of decisions that needed to be made, unlike with the non-marginalized caste (MM FGD V2).

Some marginalized women, though, contested the claim that men (or non-marginalized women) take important decisions because the latter are better educated. They asserted that marginalized women themselves do not in fact lack the freedom to improve their knowledge. Rather, they are allowing normative assumptions around their level of education to limit their opportunities to learn. These women argued that women themselves must take a lead in becoming more mobile in public spaces and informing themselves. “Women must be self-motivated to learn and get empowered in the community. She should be willing to go for meetings and trainings. If we can get more knowledge, we can also take decisions. If women are willing to grow in community she should go outside in meetings and workshops for learning” (MW FGD, V3).

The findings relating to the ability of non-marginalized women to take important expenditure decisions are markedly different. Although non-marginalized women are expected to inform their husbands about their spending priorities and to provide them with the remaining dairy income this is not necessarily a tense negotiation. One woman explained, “A woman receives money from the dairy center. She takes the money she needs for her expenses and she gives her husband the rest of the money. This was not possible earlier. We had to beg money from our husbands for all expenses” (NMW FGD, V1). Other respondents added, “Earlier women asked money from men for their needs, but now men ask women for some dairy money for their needs” and, “men say ‘milk is women’s kingdom, we have to ask money from them’” (NMW FGD, V1).

Non-marginalized women added that dairy income has helped to bulk up overall household income thus reducing tensions over “who decides” how money is spent. The fact that women now know precisely how much dairy income has been paid improves their bargaining position. Women also remarked that, compared to crop income, dairy provides a relatively small part of overall household income. Men are not particularly interested in it. However, men retain the right to take more of the dairy income at key points in the agricultural calendar when they need money.

Non-marginalized men attributed women’s stronger voice directly to their membership of Mulukanoor Dairy. “Women’s capacity to influence decision making has increased over the past 20 years. Money is coming in women’s name, so they have more power to spend money. However, it is up to women to give and share money with men for household smooth relations” (NMM FGD, V1). The concept of smooth household relations was widely shared and is the primary reason why women agree to share their milk income with men.

Finally, we turn to credit as a potential game-changer for marginalized women with respect to their caste and also with respect to their relative decision-making power vis-à-vis men. Credit is of particular importance to the marginalized caste, who rarely access loans from banks as they do not have sufficient land to offer as collateral (and women do not own any land). Marginalized women’s dairy income, obtained through their membership of Mulukanoor Dairy, assists them to obtain informal credit through relatives and friends. They then typically save this money in SHGs thus creating more funds for themselves. This money is used for repaying SHG loans, school fees, health care expenses and procuring nutritious household food. This in turn provides women with a stronger voice in intra-household negotiations. A man explained the feedback loop as follows: “My wife got 50,000 rupees from her SHG group loan and we bought one more animal. She can influence me on the spending of the dairy income easily” (MM FGD, V2).

Furthermore, marginalized women are able to offer their membership of Mulukanoor Dairy as a form of collateral in their negotiations with their SHGs. This allows them to obtain significant loans from SHGs (up to 100,000 rupees/1 lakh/ approximately 1,220 USD) whereas marginalized men can generally expect to obtain a loan of no more than Rs 20,000 (approximately 245 USD) from the bank. Marginalized men explained, “This is giving some power to the woman within the household. So, we must listen to her suggestions. As she is unable to handle the things outside the household like purchase feed and livestock, she depends on us” (MM FGD, V2). Whilst men appeared anxious to stress that they remain pivotal decision-makers, some SC women seemed to contest this. “Our husbands respect us nowadays. If they say anything against us we do not share dairy income with them. We help them to get agricultural loans from self-help groups. We share the expenses nowadays” (MM FGD, V3).

The second research question was as follows. Changes in caste relations at village level. The research question was: Are caste dynamics among women and men belonging to different castes changing? We decided to elicit this through examining CoFS-29 information exchange between castes.

Over the past 20 years Mulukanoor Dairy has trained women across caste together on the technical aspects of the dairy chain. More recently it has opened up its training programs to men across caste. We hypothesized that co-training across caste would lead to shifts in how people share knowledge – in particular, that they would share knowledge with people of other castes as well as their own castes. We also hypothesized that men and women would share knowledge with each other freely.

To find out, we first asked the respondents (in single sex FGDs) to draw simple knowledge sharing maps. They depicted themselves in the middle of the paper, and then drew lines from themselves to the individuals who had shared knowledge with them—and with whom they had shared their knowledge—with respect to CoFS-29. They were then asked to explain their maps in terms of the gender and caste of the people they depicted. We then aggregated the flows of information to create one knowledge map for men, and one for women. These are depicted below, and discussed.

On the basis of this exercise, we asked respondents to reflect more generally on their relationships with people in other castes. In this section, we first present the knowledge mapping exercise and then turn to the broader reflections.

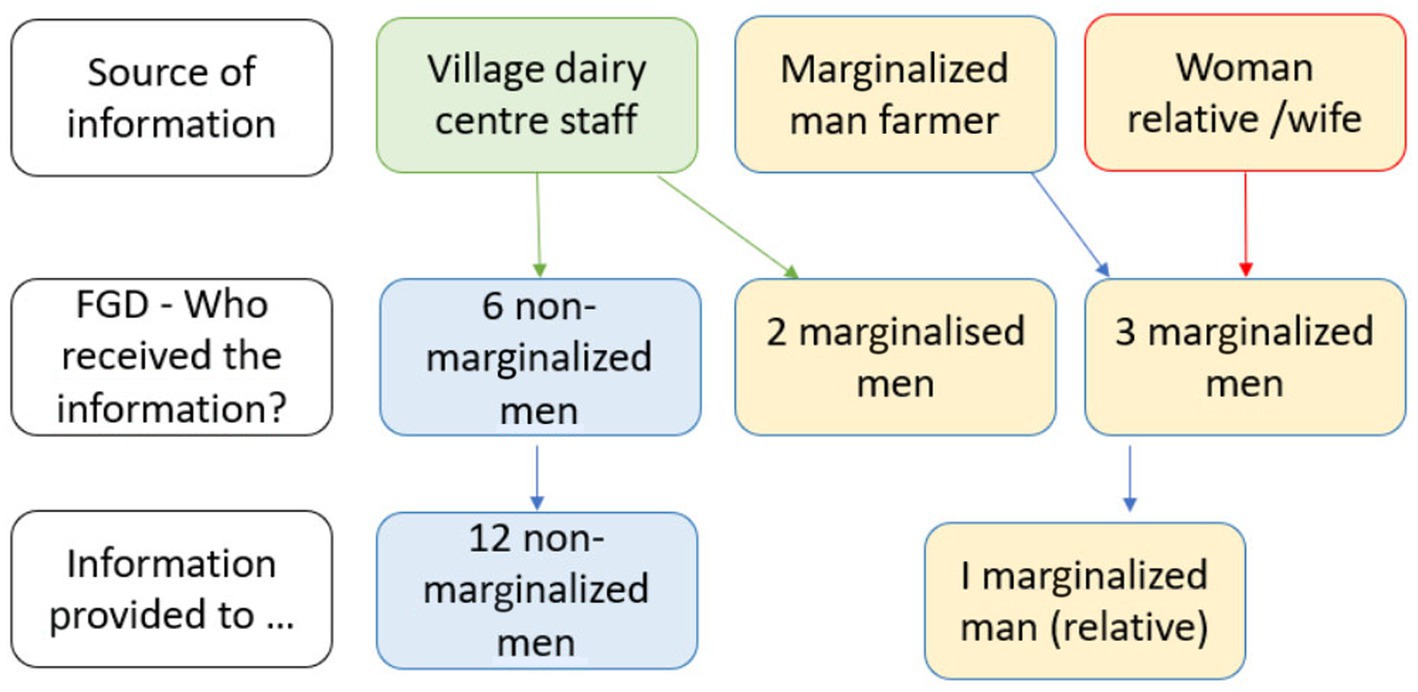

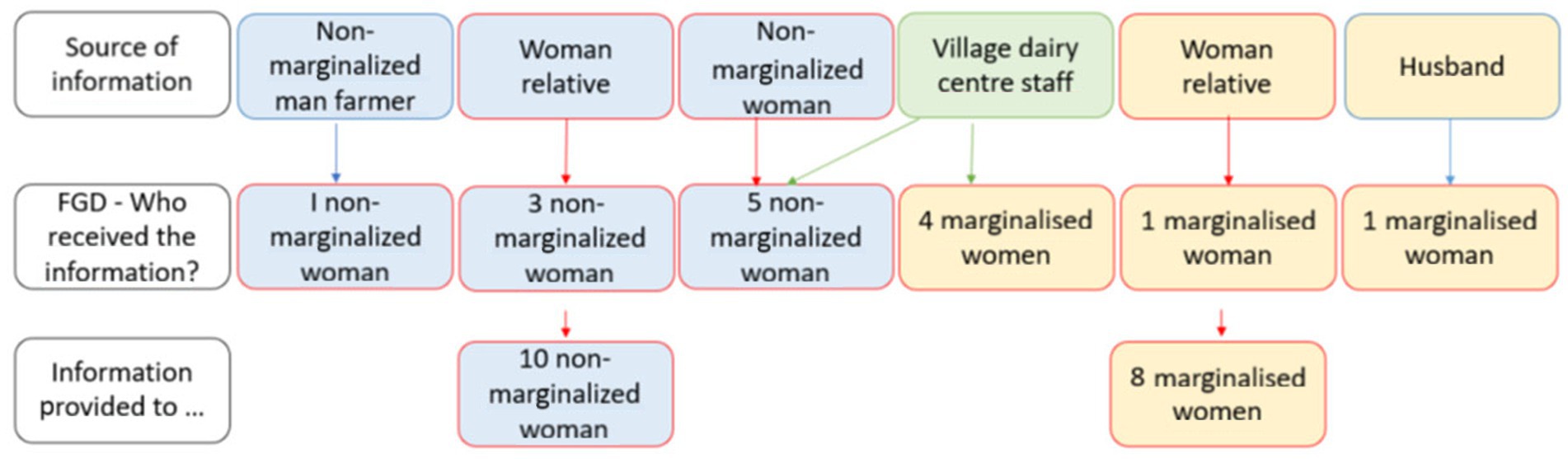

The colors used on the Figures presented below indicate caste and gender, with blue referring to the non-marginalized caste, yellow to the marginalized caste, with green being caste-free. White is a topic heading. Gender is indicated by the box outline, blue for men and red for women, with a green outline indicating a gender-free domain. The same colors are used to indicate flows of information.

Figure 2 combines the findings from two men’s FGDs. The top row indicates the original source of information. FGD respondents occupy row two, and the people they disseminated to are shown on row three. Along the middle row, the numbers refer to the FGD respondents. All six non-marginalized men FGD respondents received information direct from dairy center staff. However, two marginalized men FGD respondents obtained information from their wife or a female relative, two from the village dairy society, and one man learned about the innovation from another male farmer of his caste. The six non-marginalized men shared their information exclusively with men of their own caste.

Figure 2. Men’s knowledge sharing networks. FGDs with men: non-marginalized men (no. 6), and marginalized men (no. 5).

Figure 2 indicates important differentials in men’s knowledge sharing networks. Non-marginalized men indicated that their wives and women relatives were informed, but when they wanted information, they preferred to go direct to the dairy center secretary. They explained that the secretary—often a man—tells men about the new technology when they come to sell milk, and “then information is passed man to man” (NMM FGD, V3).

The picture for marginalized men is mixed with some relying on the village dairy, some on male relatives and some on women relatives or spouses for their information. One marginalized man indicated that he actively sought out information on CoFS-29, but rather than ask farmers from another caste, he approached the dairy society directly. He explained, “I saw the forage being planted in our village by the non-marginalized caste and I found the stems to be slender and heard it is a good variety. I asked the dairy staff to let us know the seed details, then I planted it in my farm” (MM FGD, V4).

The women’s knowledge sharing map is constructed in the same way as the men’s map. The top row indicates the original source of information. FGD respondents occupy row two, and the people they disseminated information to are shown on row three. Figure 3 combines information from two women’s FGDs.

Figure 3. Women’s knowledge sharing networks. FGDs with women: non-marginalized women (no. 9), and marginalized women (no. 6).

The sources of information are more complex than for the men’s map. Three non-marginalized women FGD respondents received information from the village dairy society. Non-marginalized women also received information from a local man farmer, a relative of the same caste, and from other Mulukanoor women members of the same caste.

Four of the marginalized women FGD respondents obtained information from the dairy center due to direct training in the new forage variety. One obtained information from her husband and another from a woman relative.

Non-marginalized women passed on information to two other women in four cases (in one case, to a sister), to one person in four cases (in two cases sisters). In two cases non-marginalized women did not share their information at all. Among the six marginalized women, two shared with two other women and four shared with one other woman each (in two cases with a relative). Non-marginalized and marginalized women shared only within their caste.

The overall findings are summarized in Figure 4. The same colors as with the figures above are used to indicate gender: red for women, blue for men, and green for a neutral actor. The lines between actors are colored according to whether the recipient is a woman or a man. Five observations can be drawn from Figure 4. First that knowledge sharing networks begin to masculinize from the source of the information to the end user. Second, this occurs despite women to women sharing within a caste. Third, despite the efforts of Mulukanoor Dairy to train people of different castes together, these efforts have not resulted in inter-caste knowledge sharing networks in the community. Fourth, non-marginalized women and men—and marginalized women—are more likely than marginalized caste men to learn about new forage varieties from the village dairy center. Finally, marginalized men are less likely than anyone else to share information on new forage varieties.

Men-dominated decision-making on field crops lie behind the masculinization of the forage knowledge sharing network. As testified by women and men respondents from all castes, men’s decision-making on the utilization of land lies unequivocally within their purview. “Women are trained first, but they inform their husbands. When men understand adoption is faster because men take decisions on which land to allocate and how much to plant” (NMW FGD, Village 2). Marginalized men claimed that women plant forage seeds but otherwise took no decision-making role regarding whether or not to grow forage. These attitudes demotivate many—though not all—marginalized women. They explained that “Anyone can access information but only a few women take the learning further,” that “Society thinks men know more than women,” and that “Women can learn just like men, but they need to speak up and be bold and confident” (MW FGD, V3). Even so, marginalized women do share information with each other.

Furthermore, the knowledge dissemination system expresses and reinforces caste biases in the dairy business. Non-marginalized castes own better quality—and more—land than marginalized castes. This sets a positive feedback loop in motion, whereby cattle and buffalo owned by non-marginalized castes provide more milk through consuming improved forages. This contributes to higher incomes from milk sales which in turn leads to the purchase of more dairy livestock and thus more income. Furthermore, larger livestock holdings promote livelihood resilience in drought years. “Income from dairy increased after the provision of improved forage. This helped us cope with the agricultural crisis. The forage requires little water which was particularly important in that drought year” (NMM FGD, V3).

Conversely, in marginalized households negative feedback loops operate. The respondents explained that the majority of marginalized men do not plant improved forages because their land is low quality and too small to support forages as well as food crops for their household consumption. This results in a general unwillingness among most marginalized women and men to attend technical training, though it is freely offered to all. Men commented, “Even though there is equal access to information, only a few in our community try to learn about forages” (MM FGD, V4).

Marginalized women expressed their appreciation of being able to mix with non-marginalized women at Mulukanoor Dairy’s meeting and training events. Women across caste mix, sit and eat together. This freedom to mix has been extended to some degree to public spaces in the community which are now more open to women of all castes.

Twenty years ago, non-marginalized women were largely restricted to their homes and a priori could not mix with other castes. Today, however, non-marginalized women can move freely within the village and visit the local town in company with other women of the same caste. They do not mix, though, with women of marginalized caste.

Changes in a few caste norms appear to be accelerating. Non-marginalized men noted a “very drastic change in education and economic empowerment” over the 5 years prior to the research in 2021. Furthermore, previously “when non-marginalized caste men came to pour milk [at the village dairy society], marginalized castes gave way and showed respect. Nowadays everyone gets the same respect standing in a queue” (NMM FGD, V3). Non-marginalized respondents were clear, though, that this freedom only occurs at the village dairy society (a Mulukanoor space). They do not attend non-marginalized caste festivals, and caste hierarchies and associated behaviors are observed at temples. Taboos preventing eating together are strictly enforced. Non-marginalized women and men do not eat in the homes of marginalized communities. Marginalized communities are provided with a separate tent for their meals when attending functions which non-marginalized members of the community organize, or attend.

This article opened through observing that feminists in the Global South were prominent in defining women’s empowerment during the 1980s and 1990s, and that their definitions emerged from a background of activism. Some organizations that drew inspiration from this thinking, including Mulukanoor Dairy, exist today. Our research questions were based on the hypothesis that if women members of Mulukanoor Dairy had become empowered over the past 20 years due to the gender and caste empowerment strategies of Mulukanoor Dairy we should be able to see evidence for this today.

Strategies to strengthen women’s empowerment in Mulukanoor involved—across caste (i) offering technical training to women, (ii) ensuring board members are (almost) exclusively women with positions open to all, and (iii) paying women directly for milk. Strategies to improve inter-caste relations included (i) mixing and selling milk from all castes, and (ii) seating and eating together at Mulukanoor events. Figures 5, 6 summarize the changes that have resulted, according to our respondents, as a consequence of these strategies.

Strategies to empower women

Our findings show that women across caste benefit directly from technical training courses offered by Mulukanoor Dairy. This strategy has the potential to create a new norm that women (rather than, or as well as men) are knowledgeable and able to act on their knowledge. Broadly speaking, women are indeed now recognized to be knowledgeable. The data show that they are experiencing stronger power within now, which is contributing to a new norm privileging women’s power to act in relation to the allocation of milk and spending of dairy income. This is primarily due to Mulukanoor Dairy’ strategy to pay women directly for milk. Paying women rather than men for milk has led directly to the establishment of new norms. First, women are free to allocate milk for household consumption and sale. Whereas men previously drank milk, now children and elderly people are prioritized, and women also drink milk. Second, women’s direct access to dairy income enables them to purchase livestock, pay school fees, and other household needs. Their investments in livestock and SHGs has the effect of multiplying women’s income from dairy. The virtuous circle thus instigated is recognized, by women and men across caste, to strengthen women’s say in intra-household decision-making.

In relation to decision-making around dairy, there is an evident and significant shift in normative power relations away from the power over norm that had previously characterized knowledge relations between women and men. However, caste identity nuances these gains, with marginalized women less recognized to be knowledgeable. Surendran-Padmaja et al. (2023) highlight literature focused on caste-gender interactions which suggest that marginalized castes can be subject to sanctions—including violence—when women attempt to challenge gender and caste-based discrimination (see Bidner and Eswaran, 2015; Datta and Satija, 2020; Farnworth et al., 2022). Fear of sanctions may similarly lie behind the efforts of marginalized men in this study to play down their wife’s decision-making power, though this is speculation. In their own study in Madhya Pradesh, Surendran-Padmaja et al. (2023) intriguingly find that in some marginalized communities men feared gaining “a bad reputation when women gained financial independence,” yet in other marginalized communities marginalized men felt their wives would benefit from becoming more empowered (Surendran-Padmaja et al., 2023, p. 7).

However, women’s improved decision-making power appears to be almost hermetically restricted to a specific set of decisions around dairy, including whether to buy new animals—a large decision which women finance through their own funds. Yet, generally their decision-making power does not extend to decisions around whether to plant forage because land-related decisions continue to lie within men’s normative remit—though the data suggests that a few non-marginalized women have some influence. Farnworth et al. (2022), in a study conducted in a farming community in Madhya Pradesh, find that women across caste conduct fieldwork on their own farms, and as paid day laborers for other farmers, yet very few of these women consider themselves “farmers.” Men also refuse to acknowledge them as such. As a consequence, men rarely permit women a say in field decisions, and women never interact with external partners (Farnworth et al., 2022). This finding echoes those of the current study, whereby women members of Mulukanoor Dairy do not interact with extension agents, AI technicians, market agents and other knowledge brokers. Although women are acknowledged to be livestock owners, they are not considered farmers. Much literature has discussed the issue of women’s recognition as farmers and its implications (Galiè et al., 2013). As a consequence of the continuing expression of gendered—and caste norms in public spaces, women’s abilities to generate and exercise their knowledge are largely limited to the narrow channels provided by Mulukanoor Dairy.

The inability of women to break through into new knowledge networks is reflected in the way Mulukanoor Dairy abandoned its strategy to provide technical training only to women. A decision to throw open its doors to men’s participation in training was taken several years ago. This may have appeared to be a necessity given the normative desire of men to retain decision-making power over key capitals required for successful dairying, including natural capital (land and forage) and social capital. However, the outcome is that men once again are primary knowledge holders alongside women. Our tentative findings suggest that information asymmetry is beginning to reassert itself in favor of men. It is too early to say whether this will continue. In Uttar Pradesh, an examination of women’s and men’s information networks similarly found very little overlap between them, and further found that women’s information networks have little influence upon intra-household decision-making around technology adoption (Magnan et al., 2015).

The question thus arises as to whether—had Mulukanoor Dairy continued to support exclusive women’s training—this would have, over time, transformed gender norms around ‘who is knowledgeable’ and whether this might slowly have strengthened women’s claim to the productive assets upon which dairying depends—and potentially helped some women to move up the value chain away from production and into new roles in marketing and knowledge broking. It would be valuable to research a situation similar to Mulukanoor Dairy in which women have been exclusively trained in a technology over time to help understand if this has undermined programmatic biases towards strengthening women’s knowledge, or rather empowered women to move into new entrepreneurial domains. It is likely, though, that such efforts would need to be embedded within a broader gender-transformative change methodology focused on working with women and men, and partners at a range of levels, to identify and address harmful gender norms across the community (McDougall et al., 2021).

The fact that wider gender norms around the control over productive resources have not changed does not seem to be considered by a respondent to be unjust. It appears to be commonsense to ensure men are well-trained as they own resources, care for livestock, and manage key transactions with resource brokers. There is no evidence for critical scrutiny by the FGD respondents of these deeper power over norms, even though they foster gender inequalities and continued expression of gender-inequitable masculinities. This leads the authors to consider whether the concept of doxa applies. Doxa conveys the idea that some norms lie so deep and are so fully naturalized they lie below the level of conscious awareness (Bourdieu, 1977). Farnworth et al. (2021) utilized the concept of doxa as an analytic lens to examine decision-making data from farming communities in four Indian states. Their study found no evidence of doxa: women were fully aware of men’s dominant role in decision-making. However, some women—particularly among the non-marginalized caste in some communities, acquiesced in their own silencing. Risseeuw (2005) argues that even acquiescence is a form of resistance, because women are taking a decision even though it is one born out of low power. Perhaps the more disempowered women in the current study engage in a strategy which moves slightly beyond acquiescence. They seem to engage in a non-articulated exchange which acknowledges that women now have important power over dairying therefore it seems judicious to allow men power over other resources. In any case, it is clear that a unitary model of household decision-making does not apply (Sen, 1990). Further research into how the relative jointness of household making changes over time in cooperatives and other institutional settings would be valuable (Ambler et al., 2017; Seymour and Peterman, 2018; Acosta et al., 2019).

Disaggregation by caste nuances these findings. Non-marginalized caste women express stronger power within and power to act than do most marginalized women. Non-marginalized women express their views with confidence and claim strong say in intra-household decision-making processes. By way of contrast many, though not all, marginalized caste women are more hesitant in claiming strong decision-making power. Marginalized men generally express a strong version of power over women whereas non-marginalized men tend towards a more collegial view. The data suggest this is due to non-marginalized women experiencing a strong form of power through (a non-agentic form of power) by virtue of their caste identity. The processes constructing the identities of non-marginalized women result in them obtaining more years of formal education than marginalized women. Higher levels of education command more respect within the community and they contribute to strengthened ability—as individuals and collectively—to practice agency effectively. Interestingly, this contradicts findings by Surendran-Padmaja et al., (2023) who find that non-marginalized men, and men with more land, are more likely to consider that the wider community would frown upon households demonstrating changing gender roles. Sankaran et al. (2017) similarly find that non-marginalized caste violation of social (and gender) norms is likely to result in strong sanctions being applied to the norm violator. In our case, it is plausible to argue that the action of Mulukanoor Dairy to empower women has indeed been extremely successful, to the extent that women speaking out—particularly among the non-marginalized caste, are no longer considered to be violating norms.

Mulukanoor Dairy has used its power to empower to implement strategies which encourage women across caste to meet, share ideas and to participate in governance. A major indicator of the success of this approach is that a new norm has emerged, namely that marginalized women are now active in the dairy industry, and they are also elected to board positions—though the board remains dominated by non-marginalized castes (Ravichandran, 2018). Nevertheless, little of this collegiality translates outside this protected space in the form of more equitable inter-caste community relations. Our findings show that technical knowledge tends to be shared within, rather than between, castes. Village events, though open to everyone, are characterized by caste separation according to caste norms. This said, there is improved acknowledgement of members from different castes in the field, and it is particularly interesting that non-marginalized castes, including men, can no longer queue-jump at the village dairy. This finding suggests that the caste equality practiced by women in Mulukanoor Dairy’s spaces has begun to translate into changing men’s behaviors within the village albeit in a limited way.

Our findings are echoed by Mudliar and Koontz (2018). They discuss the outcomes of their study into a community organization in Karnataka, India. Here, they argue, the expression of caste is generally—though not entirely—muted. By this they mean that caste norms are not observed in community organization meetings. The community organization has proven successful in instituting collective action across caste for better natural resource management. Yet—just as with Mulukanoor Dairy—caste observance continues in all aspects of village life thereby reproducing caste inequalities. Mudliar and Koontz (2018) further argue that the switching off and switching on of caste identity within and beyond the organizational setting means that marginalized caste group members tend to fall back on caste norms of deference within the organization, not least because they expect to encounter non-marginalized members in everyday village life. It seems likely that similar concerns operate in Mulukanoor Dairy communities. The age-old structures of caste, which have endured for millennia—particularly in rural India (Deshpande, 2010)—and the sanctions associated with contravening caste norms still largely structure and challenge people’s ability to form collegial relations.

Mulukanoor Dairy has been largely successful at empowering women across caste, who have seen an improvement in gender relations in their household. Such improved decision-making, however, is mostly limited to decision making specifically around dairy. When it comes to caste relations, Mulukanoor has instituted a new norm that marginalized caste women are dairy farmers. This constitutes a transformative change in local caste arrangements which is nevertheless limited in scope. Mulukanoor Dairy has not developed strategies to change caste norms beyond its doors. This means that the structural disadvantages of women in marginalized castes—which compromise their ability to benefit fully from their membership—remain unaddressed. Mulukanoor Dairy empowers women across caste, but the benefits are not equally distributed because the playing field is already uneven.

In this article we grappled with the complexity of transformative change at the interface of caste and gender and their shaping systems of inequality. Our evidence raises a number of questions on the depth of transformative change. We hope that further research—which is much needed—will continue to shed light on intersectional transformative change and the strategies that may be effective to progress towards both gender and caste equality.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because “The datasets for this article are not publicly available due to concerns regarding participant anonymity. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.” Requests to access the datasets should be directed to: YS5nYWxpZUBjZ2lhci5vcmc=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by ILRI ethics committee (Ref: ILRI-IREC2021-46). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. However, oral consent was obtained from each respondent prior to any and every discussion.

AG, CF, and TR contributed to conception and design of the study. TR conducted the empirical field and wrote up the findings. CF analyzed the findings and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AG provided critical feedback to the article. TR contributed descriptive statistics of the respondents. AG and CF prepared figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We acknowledge financial support provided by the CGIAR Research Program (CRP) on Livestock, and all donors and organizations which globally support CGIAR research work through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. The work was further developed under the CGIAR SAPLING Initiative.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acosta, M., van Wessel, M., van Bommel, S., Ampaire, E. L., Twyman, J., Jassogne, L., et al. (2019). What does it mean to make a ‘joint’ decision? Unpacking intra-household decision making in agriculture: implications for policy and practice. J. Dev. Stud. 56, 1210–1229. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2019.1650169

Allen, A. (1999). The Power of Feminist Theory: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity. Westview Press, Boulder, CO.

Ambler, K., Doss, C., Kieran, C., and Passarelli, S. (2017). He says, she says: exploring patterns of spousal agreement in Bangladesh. IFPRI discussion paper 01616. IFPRI: Washington DC. Available at: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/131097/filename/131308.pdf

Basu, P., and Chakraborty, J. (2008). Land, labor, and rural development: analyzing participation in India’s village dairy cooperatives. Prof. Geogr. 60, 299–313. doi: 10.1080/00330120801985729

Batliwala, S. (2007). Taking the power out of empowerment: an experiential account. Dev. Pract. 17, 557–565. doi: 10.1080/09614520701469559

Bidner, C., and Eswaran, M. (2015). A gender-based theory of the origin of the caste system of India. J. Dev. Econ. 114, 142–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.12.006

Blümmel, M. (2017). Improved Sorghum and Pearl Millet Forage Cultivars for Intensifying Dairy Systems. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CGIAR (2017). CGIAR research program on Fish Agri-food systems, 2017. CGIAR research program on FISH Agri-food systems (FISH): Gender strategy. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems.

Chambers, R. (2006). Transforming power: from zero-sum to win-win? IDS Bull. 37, 99–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00327.x

Christie, N., and Chebrolu, P. S. (2020). “Creating space for women leadership and participation through innovative strategies: a case of tribal women’s dairy cooperatives in Gujarat” in Cooperatives and Social Innovation. eds. D. Rajasekhar, R. Manjula, and T. Paranjothi (Singapore: Springer)

Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: what works? J. Int. Dev. 28, 342–359. doi: 10.1002/jid.3210

Cornwall, A., and Rivas, A. M. (2015). From ‘gender equality and ‘women’s empowerment’ to global justice: reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Q. 36, 396–415. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341

Crouch, M., and McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 45, 483–499. doi: 10.1177/0539018406069584

Datta, A., and Satija, S. (2020). Women, development, caste, and violence in rural Bihar, India. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 26, 223–244. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2020.1779488

Deshpande, M. S. (2010). History of the Indian Caste System and its Impact on India Today. New York, NY: California University Press.

Dohmwirth, C., and Hanisch, M. (2017). Women and collective action: lessons from the Indian dairy cooperative sector. Commun. Dev. J. 53, 1–19. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsx014

Dohmwirth, C., and Liu, Z. (2020). Does cooperative membership matter for women’s empowerment? Evidence from south Indian dairy producers. J. Dev. Eff. 12, 133–150. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2020.1758749

FAO, IFAD, and WFP. (2022). Guide to Formulating Gendered Social Norms Indicators in the Context of Food Security and Nutrition. FAO: Rome.

Farhall, K., and Rickards, L. (2021). The “gender agenda” in agriculture for development and its (lack of) alignment with feminist scholarship. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:573424. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.573424

Farnworth, C. R., Bharati, P., Krishna, V. V., Roeven, L., and Badstue, L. B. (2022). Caste-gender intersectionalities in wheat-growing communities in Madhya Pradesh, India. Gend. Technol. Dev. 26, 28–57. doi: 10.1080/09718524.2022.2034096

Farnworth, C. R., Jafry, T., Bharati, P., Badstue, L., and Yadav, A. (2021). From working in the fields to taking control. Towards a typology of Women’s decision-making in wheat in India. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 33, 526–552. doi: 10.1057/s41287-020-00281-0

Galiè, A., and Farnworth, C. R. (2019, 2019). Power through: a new concept in the empowerment discourse. Glob. Food Sec. 21, 13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.07.001

Galiè, A., Jiggins, J., and Struik, P. C. (2013). Women’s identity as farmers: a case study from ten households in Syria. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci. 64-65, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.njas.2012.10.001

Gammage, S., Kabeer, N., and van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2016). Voice and agency: where are we now? Fem. Econ. 22, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2015.1101308

Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU. Available at: https://www.sfu.ca/iirp/documents/resources/101_Final.pdf

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 30, 435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Kabeer, N. (2016). “‘Leaving no one behind’: the challenge of intersecting inequalities” in World Social Science Report 2016 (Paris: UNESCO and the ISSC)

Keddie, A., Flood, M., and Hewson-Munro, S. (2022). Intersectionality and social justice in programs for boys and men. NORMA Int. J. Masculinity Stud. 17, 148–164. doi: 10.1080/18902138.2022.2026684

Kleiber, D., Cohen, P., Gomese, C., and McDougall, C. (2019). Gender-integrated research for development in Pacific coastal fisheries. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems. Program Brief: FISH-2019-02.

Lamb, R. (2013). “Madhya Pradesh” in The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. ed. F. H. Peter Berger (London, New York, NY: Routledge), 157–173.

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Davila, F., Grant, M., Megaw, T., Willetts, J., et al. (2022). Gender-transformative approaches in international development: a brief history and five uniting principles. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 95:102635. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102635

Magnan, N., Spielman, D. J., Gulati, K., and Lybbert, T. J. Information Networks Among Women and Men and the Demand For An Agricultural Technology in India. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC, (2015).

Mahoney, J., and Goertz, G. (2006). A tale of two cultures: contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Polit. Anal. 14, 227–249. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpj017

McDougall, C., Badstue, L., Mulema, A., Fischer, G., Najjar, D., Pyburn, R., et al. (2021). “Toward structural change: gender transformative approaches” in Advancing Gender Equality Through Agricultural and Environmental Research: Past, Present, and Future. eds. R. Pyburn and A. Eerdewijk (Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)), 365–402.

Mudliar, P., and Koontz, T. (2018). The muting and unmuting of caste across inter-linked action arenas: inequality and collective action in a community-based watershed group. Commons J. 12, 225–248. doi: 10.18352/ijc.807

Pansardi, P. (2012). Power to and power over: two distinct concepts of power? J. Polit. Power 5, 73–89. doi: 10.1080/2158379X.2012.658278

Ravichandran, T. (2018). Comparison of institutional arrangements for inclusive dairy market development in India. Available at: http://opus.uni-hohenheim.de/volltexte/2020/1753/pdf/Thesis_Thanammal_Ravichandran_final.pdf

Ravichandran, T., Farnworth, C. R., and Galiè, A. (2021). Empowering women in dairy cooperatives in Bihar and Telangana, India: a gender and caste analysis. AgriGender J. Gender Agric. Food Security 6, 27–42. doi: 10.19268/JGAFS.612021.3

Ravichandran, T., Hall, A., and Blümmel, M.. (2019). Opportunities for small scale green forage enterprise in Mulukanoor women dairy cooperative (MWDC), Kareem Nagar, Telangana. Presented at the forage as cash crop and opportunities for green forage Enterprise development workshop, Kareem Nagar district, India,2019. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI.

Risseeuw, C. (2005). “Bourdieu, power and resistance: gender transformation in Sri Lanka” in Sage Masters of Modern Social Thought: Pierre Bourdieu. ed. D. Robbins (London/New Delhi: Sage Publications), 93–112.

Sankaran, S., Sekerdej, M., and von Hecker, U. (2017). The role of Indian caste identity and caste inconsistent norms on status representation. Front. Psychol. 8:487. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00487

Sen, A. K. (1990). “Gender and cooperative conflicts” in Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development. ed. I. Tinker (New York: Oxford University Press)

Seymour, G., and Peterman, A. (2018). Context and measurement: an analysis of the relationship between intrahousehold decision making and autonomy. World Dev. 111, 97–112. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.027

Singh, D. N., Bohra, J. S., Bohra, J. S., Vishal Tyagi, V., Tyagi, T. S., Singh, T., et al. (2022). A review of India’s fodder production status and opportunities. Grass Forage Sci. 77, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/gfs.12561

Stuart, G. (2007). Institutional change and Embeddedness: caste and gender in financial cooperatives in rural India. Int. Public Manag. J. 10, 415–438. doi: 10.1080/10967490701683727

Sumberg, J., and Okali, C. (2013). Young people, agriculture, and transformation in rural Africa: an “opportunity space” approach. Innovations 8, 259–269. doi: 10.1162/INOV_a_00178

Surendran-Padmaja, S., Khed, D. V., and Krishna, V. V. (2023). What would others say? Exploring gendered and caste-based social norms in Central India through vignettes. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 97:102692. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102692