94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 07 July 2022

Sec. Agroecology and Ecosystem Services

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.903114

This article is part of the Research TopicIntegrated Organic Farming Systems: Approach for Efficient Food Production and Environmental SustainabilityView all 14 articles

Harnessing endophytic microbes as bioinoculants promises to solve agricultural problems and improve crop yield. Out of fifty endophytic bacteria of sunflowers, 20 were selected based on plant growth-promoting. These plant growth-promoting bacteria were identified as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Stenotrophomonas. The qualitative screening showed bacterial ability to produce hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, siderophore, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), exopolysaccharide, and solubilize phosphate. The high quantity of siderophore produced by B. cereus T4S was 87.73%. No significant difference was observed in the Bacillus sp. CAL14 (33.83%), S. indicatrix BOVIS40 (32.81%), S. maltophilia JVB5 (32.20%), S. maltophilia PK60 (33.48%), B. subtilis VS52 (33.43%), and P. saponiphilia J4R (33.24%), exhibiting high phosphate-solubilizing potential. S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. thuringiensis SFL02, B. cereus SFR35, B. cereus BLBS20, and B. albus TSN29 showed high potential for the screened enzymes. Varied IAA production was recorded under optimized conditions. The medium amended with yeast extract yielded high IAA production of 46.43 μg/ml by S. indicatrix BOVIS40. Optimum IAA production of 23.36 and 20.72 μg/ml at 5% sucrose and 3% glucose by S. maltophilia JVB5 and B. cereus T4S were recorded. At pH 7, maximum IAA production of 25.36 μg/ml was obtained by S. indicatrix BOVIS40. All the isolates exhibited high IAA production at temperatures 25, 30, and 37°C. The in vitro seed inoculation enhanced sunflower seedlings compared to the control. Therefore, exploration of copious endophytic bacteria as bioinoculants can best be promising to boost sunflower cultivation.

The environmental problems posed by the use of agrochemicals on farmlands have necessitated the need to search for ecofriendly and sustainable approaches by harnessing endophytic bacteria as the best alternative bio-input (Basu et al., 2021; Bhutani et al., 2021). Devising suitable methodologies for the characterization of agriculturally important endophytic microbes from economic crops, however, promise to avert future food insecurity. The microbes found inhabiting the internal tissue of plants are called endophytic microbes and their mutual interdependence with the host plants contributes to plant growth and health (Mukherjee et al., 2021). Hence, the overview of the multifaceted functions of endophytic microbes can systematically bring new insights into agriculture biotechnology by maximum exploration and applications.

Endophytic microbes employed direct and indirect mechanisms to ensure sustainable plant nutrition (Zaman et al., 2021). Nitrogen fixation, IAA production, phosphate solubilization, and ACC deaminase activity contribute to soil nitrogen pool, root development, plant growth, and resilience to abiotic drought stress. The antibiosis, induced systemic resistance, hydrogen cyanide, siderophore, and enzyme production by endophytic microbes protect plants from pathogen attack, so indirectly enhance plant growth (Adeleke and Babalola, 2022). An increase in plant growth and crop yield upon inoculation with plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria in the genera Bacillus, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Pantoea, and Rhizobium has been documented (Nascimento et al., 2020; Mowafy et al., 2021; Preyanga et al., 2021). In addition, some endophytic bacteria isolated from oilseed crops have been reported to enhance plant growth due to their plant growth-promoting traits (Lally et al., 2017; Abdel-Latef et al., 2021). Nevertheless, scant information is available on endophytic bacteria isolated from sunflower cultivated in Southern Africa. Hence, research findings into the sunflower microbial world for maximum exploration as bioinoculants will help improve crop yield sustainably.

Aside from maize, cowpea, wheat, and sorghum, sunflowers are one of the most edible and economic crops cultivated in the North West Province of South Africa and other countries of the world (Adeleke and Babalola, 2020). Sunflower cultivation promise to ensure food security, and the supply of nutritional and healthy food for both livestock and human beings (Seiler et al., 2017). The economic value of sunflowers is enormous, such that, sunflower oil is widely distributed and available in South African markets. The seed inoculation and optimization of endophytic bacteria under different growth conditions remain fundamental to testing their effects on sunflower seed germination. Furthermore, harnessing copious endophytic microbes on a large scale can potentially boost sunflower oil production in South Africa. Hence, this research was designed to isolate, characterize and screen sunflower-associated endophytic bacteria with plant growth-promoting traits in vitro.

The roots and stems of H. annuus cultivar PAN 7160 CLP were sourced from commercial farmland in Lichtenburg, North West Province, South Africa in February 2020. The climatic conditions of this region were characterized by an annual rainfall of 360 mm and a temperature range of 3–21°C during winter and 22–34°C during summer. The healthy sunflower samples were carefully uprooted, labeled, placed inside sterile zip-lock bags, and transported to the Microbial Biotechnology Research Group laboratory, North-West University, South Africa at 4°C for further analysis. A total of 24 samples were randomly collected in triplicates from four points within the field for the isolation of endophytic bacteria.

The sunflower roots and stems were cut into small sizes with a sterile scalpel and then washed in sterile distilled water. The samples were surface sterilized by soaking in 70% ethanol for 3 min, followed by 3% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, 70% ethanol for 30 s, and lastly rinsed 5 times with sterile distilled water. The sterilization level of the samples was assessed by plating the last rinse on Luria Bertani (LB) media (Miller, Sigma Aldrich, USA). Five grams of plant material were weighed (Radwag weighing machine; Lasec; Poland), suspended in 1 M phosphate-buffered solution (FBS), and manually macerated in a mortar and pestle until smooth suspensions were obtained. One gram of the macerated samples was weighed and aseptically dispensed into sterile test tubes containing 9 ml sterile distilled water and mixed properly. Then, 1 ml from the mixture was aseptically pipetted and serially diluted up to 10−9 dilutions. From dilutions 10−5 and 10−6, 0.1 ml of the suspension were gently dispensed into Petri plates in triplicates. The plates were pour-plated with molten sterilized Luria Bertani (LB) media and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 24 h. Distinct bacterial colonies formed on the plates were counted and recorded. Colonies from each plate were observed and selected based on morphological characteristics. The pure bacterial cultures were obtained by repeated streaking on fresh LB agar plates. Pure bacterial colonies were preserved on LB medium amended with 30% (v/v) glycerol at −20°C.

Gram staining and various biochemical tests were performed to characterize the bacterial isolates. Oxidase, urease, starch hydrolysis, citrate, and sugar fermentation tests were performed following the modified methods of Majeed et al. (2018). Other biochemical tests performed include Voges-Proskauer, hydrogen sulfide production, citrate test, nitrate utilization, methyl red test, and indole production test. All the chemical reagents used for these tests were procured from Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria, South Africa.

The ability of bacterial isolates to produce ammonia was tested according to the methods described by Alkahtani et al. (2020). Briefly, ammonia production was performed as follows: 0.1 ml of 24-h old bacterial culture (106 CFU/ml) was aseptically inoculated into test tubes containing 10 ml sterile peptone broth (peptone 0.2 g, 10 ml sterile distilled water) and incubated on a rotary shaker (SI-600, LAB Companion, Korea) at 120 rpm, at ambient temperature for 96 h. After incubation, a 0.5 ml Nessler's reagent was gently dispensed into each test tube, then allowed to stand for 5 min for color development. A color change from yellow to dark brown indicated a positive reaction. A tube without bacterial inoculation served as a control.

The phosphate solubilization potential of the bacterial isolates was evaluated according to the methods described by Premono et al. (1996). The qualitative test was performed on modified Pikovskaya agar composed of (g/L; tricalcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2) 5, glucose (C6H12O6) 10, manganese sulfate (MnSO4·H2O) 0.002, sodium chloride (NaCl) 0.2, potassium chloride (KCl) 0.2, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) 0.1, ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) 0.5, yeast extract 0.5, agar 15, at pH 7. Twenty-four-hour-old bacterial cultures were spot inoculated directly at the center of each Pikovskya's agar (PA) plate. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 5 days for the visible zone of clearance (ZOC). The ZOC (mm) around the colony on the cultured plates indicated positive results for phosphate solubilization, while the un-inoculated plate served as control. The ZOC (mm) around the colony was measured, and colony diameter measurements (mm) were summarized as low (+), medium (++), and high (+++). The phosphate-solubilizing index (PSI) was enumerated as:

PSI was grouped as low (PSI < 2.00), intermediate (2.00 ≤ PSI <4.00), or high (PSI ≥ 4.00) based on Marra et al. (2011) methods.

For the quantitative assay, the phosphate solubilizing-producing ability of the bacterial isolates was performed by inoculating 10 ml sterile Pikovskaya broth in 50 ml Falcon tubes with 0.1 ml (106 CFU/ml) freshly grown bacterial culture, incubated at 30°C for 5 days at 180 rpm on a rotary shaker (SI-600, LAB Companion, Korea). The supernatant was obtained after cold centrifugation of 10 ml bacterial cultures at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Four milliliters of the color reagent (1:1:1:2 ratio of 3 M H2SO4, 10% (w/v) ascorbic acid, 2.5% (w/v) ammonium molybdate, and distilled water) were added to 10% (w/v) of 5 ml trichloroacetic acid inside test tubes. The inoculated tubes were allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. The quantity of phosphate content was measured according to phosphomolybdate, a blue method, at an absorbance of 820 nm. The phosphate solubilization potential of endophytic bacteria in the Pikovskaya broth was determined from the phosphate (KH2PO4) standard curve. Medium without bacterial inoculation served as control.

The siderophore production ability of the bacterial isolates was performed according to the methods of Khan et al. (2020) with few modifications. Each bacterial isolate was aseptically inoculated into a sterilized medium amended with CAS, i.e., chrome azurol S. Preparation of CAS solution was performed by weighing 60.5 mg CAS into 10 ml of 1 mM iron (III) solution (FeCl3.6H2O) (a). The iron (III) solution was diluted in 10 mM HCl. The solution (a) was gently mixed with 0.0729 g hexadecyltrimethylammonium (HDTMA, Merck, SA) bromide suspended in 40 ml sterile distilled water (b) on the magnetic stirrer. From the mixture of “a” and “b,” solution, 100 ml was measured and added to 900 ml sterilized LB medium at pH 6.8. The sterilized medium at 121°C for 15 min was allowed to cool and pour plated into sterile Petri dishes. Each bacterial culture was spot-inoculated at the mid-point of the solidified agar plates and incubated at 28°C for 5 days. The development of yellow ring coloration around the bacterial colonies on the plates indicated positive reactions for siderophore production. Un-inoculated plates served as control.

The quantity of siderophore production was determined by inoculating LB broth solution containing CAS with 0.1 ml of 24-h old bacterial culture and incubated at 180 rpm on a rotary shaker (SI-600, LAB Companion, Korea) for 7 days. The grown bacterial culture was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min. From the filtrate, 0.5 ml was added to 0.5 ml CAS reagent, mixed, and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. The quantity of siderophore produced was measured at 630 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Spectronic, Merck Chemicals, SA). The siderophore values were obtained from the regression equation of the standard curve. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

The test for HCN production by bacterial endophytes was determined according to the modified method of Igiehon et al. (2019). Nine milliliters of LB broth amended with 0.4% (w/v) glycine was aseptically dispensed into test tubes, sterilized, allowed to cool, and then inoculated with 0.1 ml (106 CFU/ml) fresh bacterial inoculum. Whatman filter paper No.1 was dipped in 0.5% (w/v) picric acid and subsequently in 2% (w/v) sodium carbonate. Then, the filter paper was plugged into each test tube (without touching the broth solution), then screw-cap and stop-up with parafilm and incubated at 28°C for 5 days. The test tubes were examined daily for color changes in the filter paper. A color change from yellow to brown indicated a positive result. The un-inoculated tube served as control. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Screening for enzyme production was performed using plate assay techniques. The enzymes screened include, mannanase, cellulase, amylase, xylanase, and protease.

Screening of bacterial isolates for mannanase production was performed as described by Blibech et al. (2020) with few modifications. Briefly, media composition of g/L; Locust bean gum (3), dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) 1, iron sulfate (FeSO4) 0.001, ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) 1, sodium chloride (NaCl) 0.5, calcium chloride (CaCl2) 0.1, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) 0.5, and agar 13 at pH 7.2 was sterilized at 121°C for 15 min, allowed to cool. The media were poured plated and allowed to solidify. A 24-h old bacterial culture was gently inoculated in the middle of the agar plates and then incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Each cultured plate was flooded with iodine solution and observed for 15 min. The staining solution was poured off and further treated by flooding with 1 M sodium chloride (NaCl) for 15 min for the visible ZOC around the colonies. The colonies with a ZOC (mm) indicated mannanase production. The un-inoculated plate served as control. The experiment was carried out in triplicate for each bacterial isolate.

The qualitative screening of endophytic bacteria for cellulase production was performed using plate assay techniques according to Alkahtani et al. (2020) with little modifications. Freshly grown pure bacterial cultures were inoculated by single streaking on carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) amended media composed of g/L; dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4) 1, sodium nitrate (NaNO3) 3, iron sulfate (FeSO4) 0.01, CMC 1, potassium chloride (KCl) 0.5, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) 0.5, and agar 20 at pH 7.0. The inoculated CMC plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h and then flooded with 1% (w/v) Congo red (CR) for 10 min. The CR on the plates was gently washed off and the plates were further washed with 1 M NaCl for 15 min. The ZOC (mm) encircling the colonies indicated a positive result for cellulase production. The un-inoculated plate served as control. Negative result plates were further flooded with 5% acetic acid solution for 2 min and then washed with sterile distilled water. A clear ZOC (mm) around the colony was determined and recorded. The experiment was carried out in triplicate for each bacterial isolate.

The amylase production was tested on starch agar according to the methods of Alkahtani et al. (2020) with little modifications. A 24-h bacterial culture was spot-inoculated on sterilized starch agar medium composed of peptone 5 g, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) 0.5 g, yeast extract 5 g, iron sulfate (FeSO4) 0.01 g, soluble starch 10 g, agar 15 g, and sodium chloride (NaCl) 0.01 g in 1,000 ml sterile water and then incubated at 37°C for 48 h. After that, Lugol's iodine solution (iodine 0.4%, potassium iodide 0.8%, distilled water−200 ml) was poured on the plates for 10 min. The formation of a ZOC (mm) around each bacterial isolate on the plate indicated amylase production. The un-inoculated plate served as control. The experiment was carried out in triplicate for each bacterial isolate.

Screening of bacterial isolates for xylanase production on mineral salt medium (MSM) supplemented with 0.5% xylan (beech-wood) was performed according to the methods described by Alkahtani et al. (2020) with minor modifications. The MSM composition include, agar 2%, peptone 0.5%, yeast extract 0.3%, and sodium chloride (NaCl) 0.5%. The media solution was adjusted to pH 9 before sterilization at 121°C for 15 min. The media were allowed to cool and pour plating. Plates were inoculated with fresh 24-h old bacterial culture by straight streak at the mid-point of the plates and then incubated at 28°C for 24 h. After that, plates were flooded with 0.4% Congo red and incubated for 10 min, then washed with 1 M NaCl to determine the ZOC. The ZOC around the bacterial isolates on each plate was considered positive for xylanase production. The un-inoculated plate served as control. The experiment was carried out in triplicate for each bacterial isolate.

The primary screening for each endophytic bacterium for protease production was performed on LB agar plates supplemented with skim milk powder according to the methods described by Alkahtani et al. (2020) with little modifications. The media composition (g/L) includes, skim milk powder 28, dextrose 1, casein 5, yeast extract 2.5, and agar 15 at pH 7. The media were prepared, sterilized, and then allowed to cool before pour-plating. Consequently, fresh bacterial culture was inoculated on each plate and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. The bacterial isolates exhibiting a circular ZOC (mm) indicated a positive result for protease production. An un-inoculated plate served as control. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

The IAA production was tested according to the modified method of Gutierrez et al. (2009). Ten milliliters of LB broth supplemented with tryptophan were aseptically inoculated with 0.1 ml freshly grown bacterial culture (106 CFU/ml) and incubated at 28°C for 7 days at 120 rpm in a rotary shaker (SI-600, LAB Companion, Korea). The bacterial cultures were cold centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 8,000 rpm. IAA from the crude extract was measured by transferring 1 ml of the supernatant into a clean tube and one drop of orthophosphoric acid (10 mM) and Salkowski reagent (2 ml) (1:30:50 ratio of 0.5 M FeCl3 solution: 95% w/w sulfuric acid: distilled water) was added. The mixture was allowed to stand (incubation) for 10 min at room temperature. The appearance of pink coloration in the tubes after incubation in the dark indicated a positive result. An un-inoculated plate served as control. Color development by the bacterial strains was grouped as low, average, and high. The IAA production of the reacting mixture after incubation was determined at 530 nm using UV-spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The IAA concentration of each bacterial isolate was evaluated from the IAA gradient standard curve (SC). The experiment was performed in triplicate for mean value calculation. Furthermore, three bacterial isolates were optimized under different growth conditions: nitrogen source, carbon source, pH, and temperature.

Varied concentrations of carbon and nitrogen sources were supplemented into an IAA production medium (IPM) composed of (g/L); yeast extract 6, L-tryptophan 1, peptone 10, and NaCl 5 at pH 7.6 (Chandra et al., 2018). Other optimized conditions include incubation time, temperature, and pH. For incubation time, a 200 ml IPM inside 500 ml conical flasks was sterilized at 121°C for 15 min, allowed to cool, and then inoculated with fresh 24-h grown S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. cereus T4S, and S. maltophilia JVB5 with 0.5 optical density at 630 nm. The culture medium was incubated at 37°C, and 180 rpm for 11 days. One ml of the cultured medium was constantly withdrawn at 24-h intervals and assayed for IAA production by Salkowski's reagent. Furthermore, similar incubation conditions were used to monitor the effects of other parameters under the same IAA assay conditions. The ability of bacterial isolates to utilize carbon as substrate and their effects on IAA production was tested using 5 sugars; namely, maltose, fructose, sucrose, glucose, and galactose, at different concentrations (1, 3, and 5%) as described by Khan et al. (2020). Additionally, the ability of bacterial isolates to utilize nitrogenous-base compounds, such as peptone, potassium nitrate, casein, yeast extract, and urea as substrates were tested at different concentrations of 1, 3, and 5% (Chandra et al., 2018). The pH of the medium ranging from 4 to 10 was examined. The pH of the IAA-producing medium was adjusted using 1 M of NaOH or HCl. IPM was optimized at varied temperatures; 25, 30, 37, 45, and 60°C. After sterilization, the IPM for each optimized parameter was allowed to cool, inoculated with 0.1 ml (106 CFU/ml) of each selected bacterium, and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 7 days on a rotary incubator machine at 180 rpm. After incubation, the supernatant was subjected to an IAA assay and IAA concentration was measured at 630 nm for pH and temperature, and 590 nm for carbon and nitrogen, respectively, using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Spectronic; Meck, South Africa). The common reagents used for the plant growth-promoting screening were procured from Merck Chemicals (Pty) Ltd, Gauteng, South Africa, and Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria, South Africa.

The genomic content of pure bacterial isolates was extracted using a commercial Quick-DNATM Miniprep Kit specific for fungi or bacteria (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA; Cat. No. D6005), following the manufacturer's guide. The quantity of the extracted DNA (ng/μl) was measured using a NanoDrop ND- 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and stored at −80°C.

The determination of 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences of the identified bacterial isolates was achieved using the amplified PCR products. The specific forward and reverse primers, 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5′-TACGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3') were purchased from Inqaba Biotechnological Industrial (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria, South Africa. A total of 25 μl reaction volume for each bacterial isolate composed of 12.5 μl OneTaq 2X MasterMix with the Standard Buffer, 1 μM for each primer, ~5 ng genomic DNA, and 9.5 μl nuclease-free water were used for PCR amplification on DNA Engine DYADTM Peltier Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD, USA, C1000 TouchTM). The PCR cycle parameters were programmed as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of amplification. Also, the denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 50°C, extension for 1 min at 68°C; and a final overall extension for 10 min at 68°C. After running PCR, the PCR product was determined on agarose gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, the gel was carefully removed, and confirmation of the expected size of the product was visualized on a UV trans-illuminator. The resulting outcome was captured in a ChemidocTM imaging system (BIO-RAD Laboratories, California, USA). Finally, 20 μl of the PCR product for each bacterial isolate was placed in an ice-box pack and sent for sequencing at Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd, Pretoria of South Africa. 16S rRNA sequences for each bacterium were submitted to GenBank on the NCBI online server and were assigned with accession numbers. The twenty identifiable endophytic bacteria deposited on GenBank of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) web server can be accessed from the links provided in the data availability section.

The Basic Local Alignment Search Tools (BLAST) program of the nucleotide sequences on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was employed to determine bacterial isolate sequence similarities and identities. The sequenced data were further analyzed by subjecting to multiple sequence alignment by ClustalW using a Bio-Edit program. MEGA-X online program was used to construct the phylogenetic tree from the resulting ClustalW sequences and the maximum likelihood method of the taxa with the Tamura-Nei model. The phylogeny test of the aligned sequences was achieved by the bootstrap method (Tamura et al., 2013).

The effectiveness of sunflower seed inoculation was performed based on the methods described by Ullah et al. (2017). The bacterial inoculum size in LB broth at 24-h incubation was standardized to 0.5 (106 CFUml−1) at OD600. The three bacterial isolates, namely, S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. cereus T4S, and S. maltophilia JVB5 were selected based on the most promising plant growth-promoting properties. A seed inoculation assay was used to facilitate bacterial adherence to the disinfected sunflower seeds. Cleaning of the seeds was performed by washing in sterile distilled water to remove floating-unhealthy seeds and dirt, and disinfected in 70% ethanol for 3 min, followed by 3% hypochlorite for 3 min, then immersed in 70% alcohol for 30 s, and lastly rinsed 5 times with sterile distilled water. Prepared LB broth inoculated with fresh bacterial culture was incubated at room temperature in a rotary incubator machine (SI-600, LAB Companion, Korea) at 180 rpm for 24 h. The bacterial cells in the broth culture were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min to obtain the pelletized cells and then washed in 0.85% normal saline solution. The centrifugation and washing of the pellets were performed under sterile conditions. The surface-sterilized seeds were suspended in a bacterial suspension containing 1% (v/w) carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) as an adhesive (binder) in a 250 ml flask for 60 min. The seeds suspended in sterile distilled water containing 1% (v/w) CMC without bacterial inoculum served as control.

Under sterile conditions, 10 coated seeds (of each bacterial strain) were placed inside Petri dishes lined with moistened sterile absorbent cotton and sealed with parafilm. The plates were kept at 28°C in the growth chamber and seedling growth was monitored daily for 5 days. Each treatment was performed in triplicates. The plates were carefully taken out for seedling growth assessment. The fresh weight and dry weight of seedlings after oven drying at 60°C were measured. The seedling's fresh and dry weight obtained was expressed in gram (g) per triplicate.

The analysis of data from this study was performed using SPSS - Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 6.0) and Microsoft Excel. A significant difference among the treatment groups was calculated using ANOVA - one-way analysis of variance. The mean difference was determined by Duncan's tests at a 5% level of significance. Data obtained were presented as mean ± standard deviation. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

The sequenced dataset associated with this study can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW261910, and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=MW265413:MW265431[accn].

A total of twenty-seven bacterial isolates from the roots and twenty-three bacterial isolates from the stems were isolated and characterized. However, ten (10) bacteria isolated from the stems and ten (10) bacteria isolated from the roots were further characterized and selected for plant growth-promoting screening based on the distinct morphological characterization, Gram staining, and biochemical tests (see Table 2 below). The cultural, biochemical characterization, and sugar utilization by endophytic bacteria from sunflowers were presented in Tables 1A,B.

Based on Gram reaction, 70% of the bacterial isolates were Gram-positive, whereas 30% were Gram-negative. The Gram-negative bacterial endophytes identified include Pseudomonas sp. FOBS21, S. maltophilia PK60/JVB5, S. indicatrix BOVIS40, P. saponiphilia J4R, and P. lini BS27, while Gram-positive bacterial isolates include the genus Bacillus. All the bacterial isolates were rod-like with positive results for oxidase, hydrogen sulfide production, Voges-Proskauer, and methyl red. B. thuringiensis BSA123 was positive for the citrate test, while nine isolates were positive for gelatin liquefaction. B. cereus SFR35 utilizes indole while B. thuringiensis BSA123 showed a positive reaction to casein hydrolysis. For nitrate utilization, eight bacterial isolates produced gas (N2), while sixteen reduced nitrates. All the isolates were urease negative. For sugar fermentation tests, all bacterial isolates fermented glucose, fructose, arabinose, mannitol, xylose, and maltose, respectively. Based on molecular identification, Bacillus species were the most common identifiable bacteria in the stem and root samples (Table 2). Each bacterial strain was designated as SFR35, FTL29, T4S, CAL14, BS27, BOVIS40, JVB5, TSN29, BLBS20, SFL02, PK60, VS52, BAAG44, SFS19, OLT2020, BSA123, LS11, J4R, VEJU7080 and FOBS21 (Table 2).

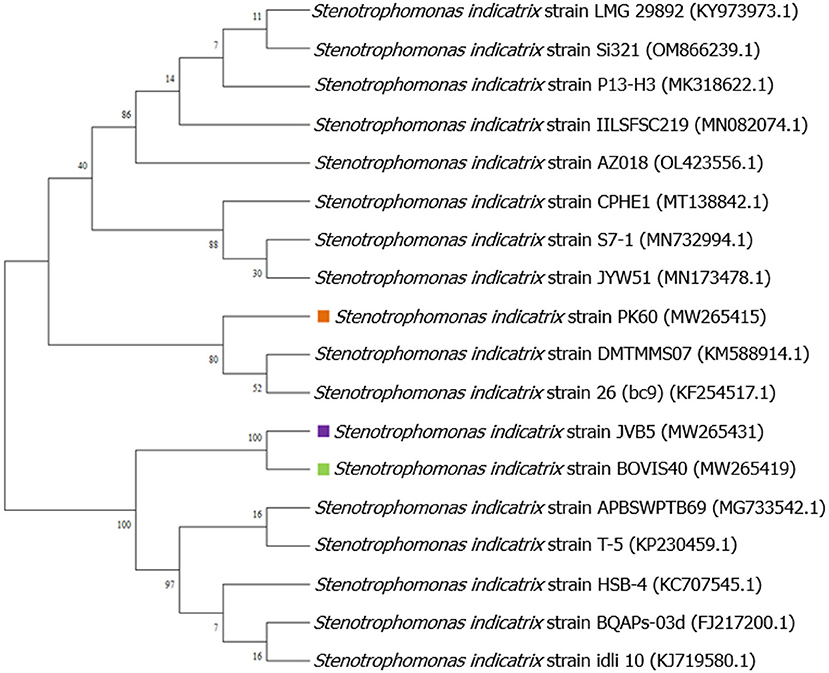

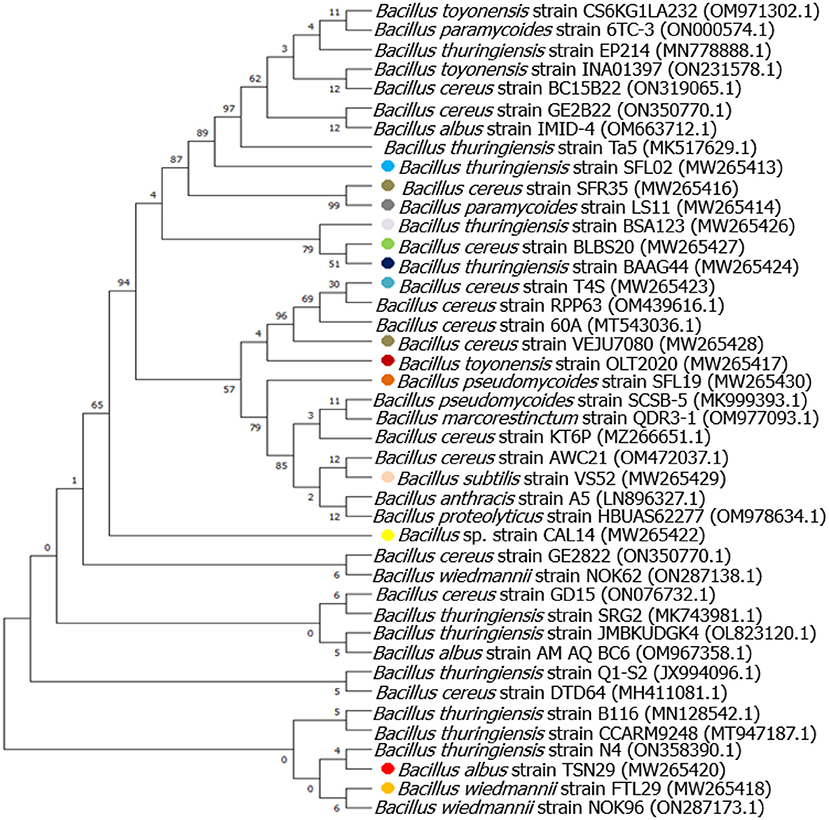

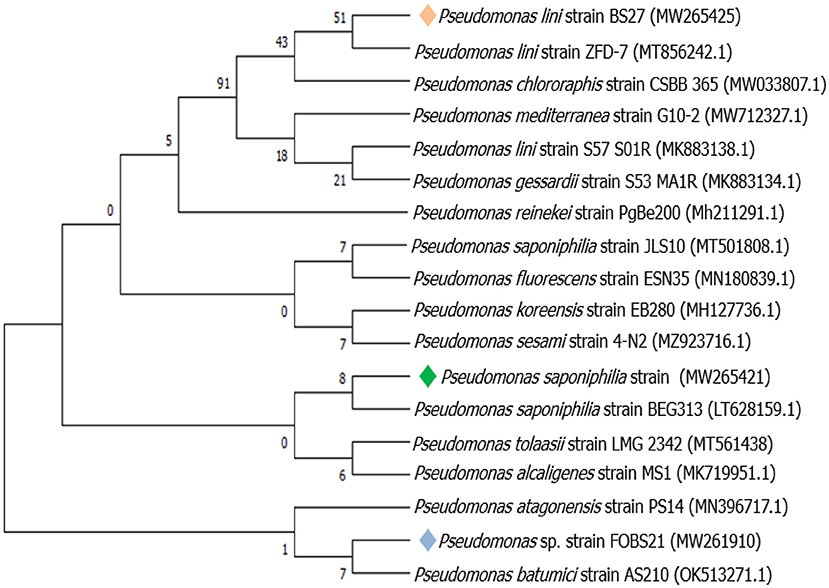

The identification of endophytic bacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences was presented in Table 2. The phylogeny information of the identifiable bacteria genera and bacterial sequences of related genera recovered from the GenBank database is shown in Figures 1–3.

Figure 1. Evolutionary relationships of taxa tree based on partial 16S rRNA sequences using maximum likelihood-based on the Tamura-Nei model showing relationships between the endophytic Stenotrophomonas species and its closely related strains from NCBI GenBank.

Figure 2. Evolutionary relationships of taxa tree based on partial 16S rRNA sequences using maximum likelihood-based on the Tamura-Nei model showing relationships between the endophytic Bacillus species and its closely related strains from NCBI GenBank.

Figure 3. Evolutionary relationships of taxa tree based on partial 16S rRNA sequences using maximum likelihood-based on the Tamura-Nei model showing relationships between the endophytic Pseudomonas species and its closely related strains from NCBI GenBank.

The plant growth-promoting traits of endophytic bacteria from sunflowers are presented in Table 3. The qualitative screening revealed the ability of the bacterial isolates to produce ammonia, siderophore, exopolysaccharide, hydrogen cyanide, IAA, and solubilize phosphate. Nine bacterial isolates exhibited high siderophore production, while five exhibited medium and six exhibited low activity for the siderophore production. The quantitative results revealed a high siderophore value of 87.73 % by B. cereus T4S.

The qualitative screening of endophytic bacteria for enzyme production; namely, amylase, cellulase, xylanase, mannanase, and protease was presented in Table 4. S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. weidmannii FTL29, B. subtilis VS52, and B. thuringiensis BSA123, exhibited a positive reaction to all enzymes assayed. Except for amylase, bacterial isolates B. cereus VEJU7080 and B. cereus T4S were positive for other screened enzymes. Summarily, bacterial isolated designated B. weidmannii FTL29, B. albus TSN29, B. thuringiensis BSA123, and B. thuringiensis BAAG44 displayed amylase, xylanase, mannanase, and protease production tendencies, respectively.

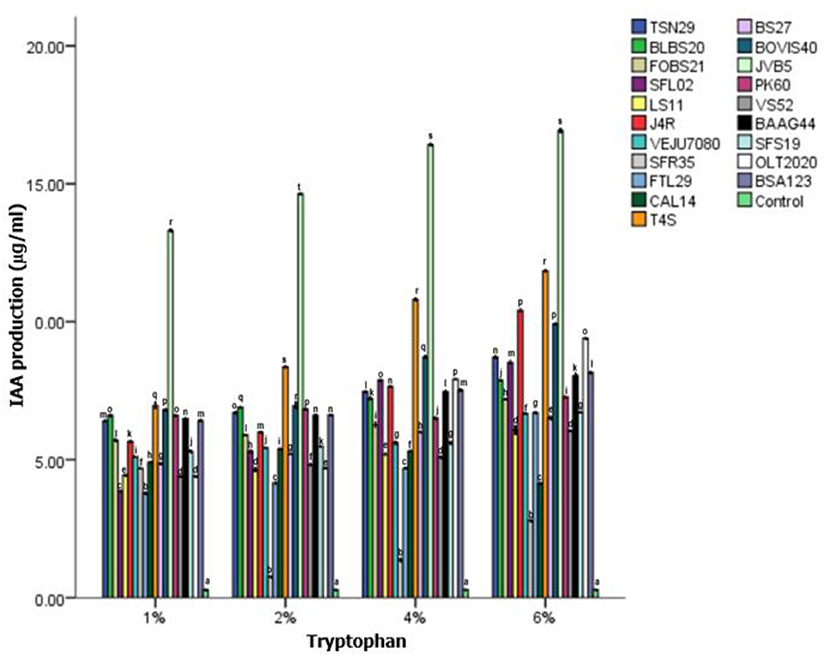

All the bacterial isolates displayed varied IAA activities at different L-tryptophan concentrations. The medium supplemented with L-tryptophan yielded higher IAA production compared to the control (Figure 4). Bacterial strains, S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. cereus T4S, and S. maltophilia JVB5 from the roots of sunflower exhibited high IAA production compared with other isolates. In contrast, the lowest IAA production was observed in B. cereus SFR35 compared with the control.

Figure 4. Qualitative screening of endophytic bacteria for indole acetic acid production. Bacterial isolate codes are represented in Table 2 and different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings. SFR35, B. cereus; FTL29, B. wiedmannii; CAL14, Bacillus sp.; T4S, B. cereus; BS27, P. lini; BOVIS40, S. indicatrix; JVB5, S. maltophilia; TSN29, B. albus; BLBS20, B. cereus; SFL02, B. thuringiensis; PK60, S. maltophilia, VS52, B. subtilis, BAAG44, B. thuringiensis, SFS19, B. pseudomycoides, OLT2020, B. toyonensis, BSA123, B. thuringiensis, LS11, B. paramycoides, J4R, Pseud. saponiphilia; VEJU7080, B. cereus; FOBS21, Pseudomonas sp.

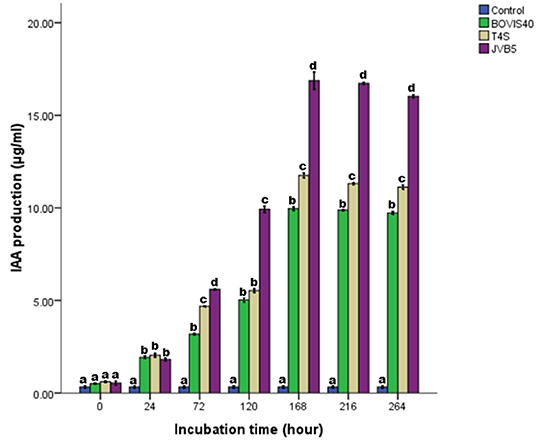

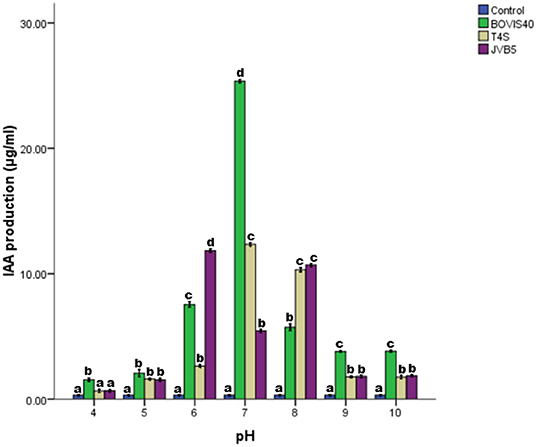

The time course for IAA production by the bacterial isolates was presented in Figure 5. An increase in IAA production with an increase in incubation time was recorded. Optimum IAA production was attained at 168 h and beyond this point, there was a decline. The optimum IAA production of 16.94, 11.76, and 9.92 μg/ml at 168 h of incubation were recorded by S. maltophilia JVB5, B. cereus T4S, and S. indicatrix BOVIS40, respectively. The results of IAA produced by the bacterial isolates monitored between pH 4–10 were presented in Figure 6. The IAA production increased from pH 4–7, and beyond this point, there was a decline from pH 8–10. S. indicatrix BOVIS40 showed maximum IAA production of 25.36 μg/ml, followed by B. cereus T4S of 12.34 μg/ml and S. maltophilia JVB5 of 5.46 μg/ml at pH 7. Similarly, maximum IAA production of 11.83 μg/ml by S. maltophilia JVB5 at pH 6, 10.74 μg/ml at pH 8, with the least IAA production of 2.83 μg/ml at pH 4 were obtained. At pH 9 and 10, no significant difference was observed in the IAA production of B. cereus T4S and S. maltophilia JVB5.

Figure 5. IAA production by endophytic bacteria in the growth medium after 11 days of incubation. The different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings.

Figure 6. Effect of pH on IAA production by endophytic bacteria. The different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings.

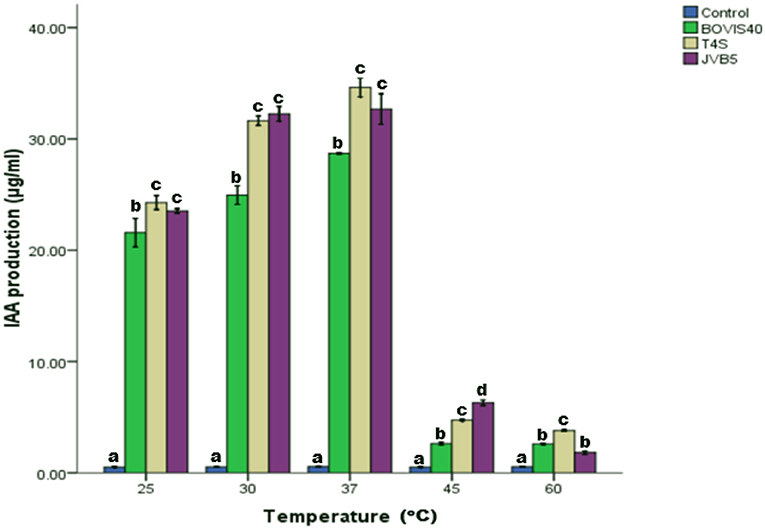

The effect of incubation temperature on IAA production by endophytic bacteria ranging from 25 to 60°C was presented in Figure 7. Maximum IAA production of 34.40 μg/ml by B. cereus T4S at 37°C was recorded. The amount of IAA produced at temperatures 45 and 60°C was lower compared with other temperatures. Bacterial strains showed an increase in IAA production from temperature 25−37°C before it declined. At 30 and 37°C, there was no significant difference in the IAA production by S. maltophilia JVB5.

Figure 7. Effect of temperature on IAA production by endophytic bacteria. The different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings.

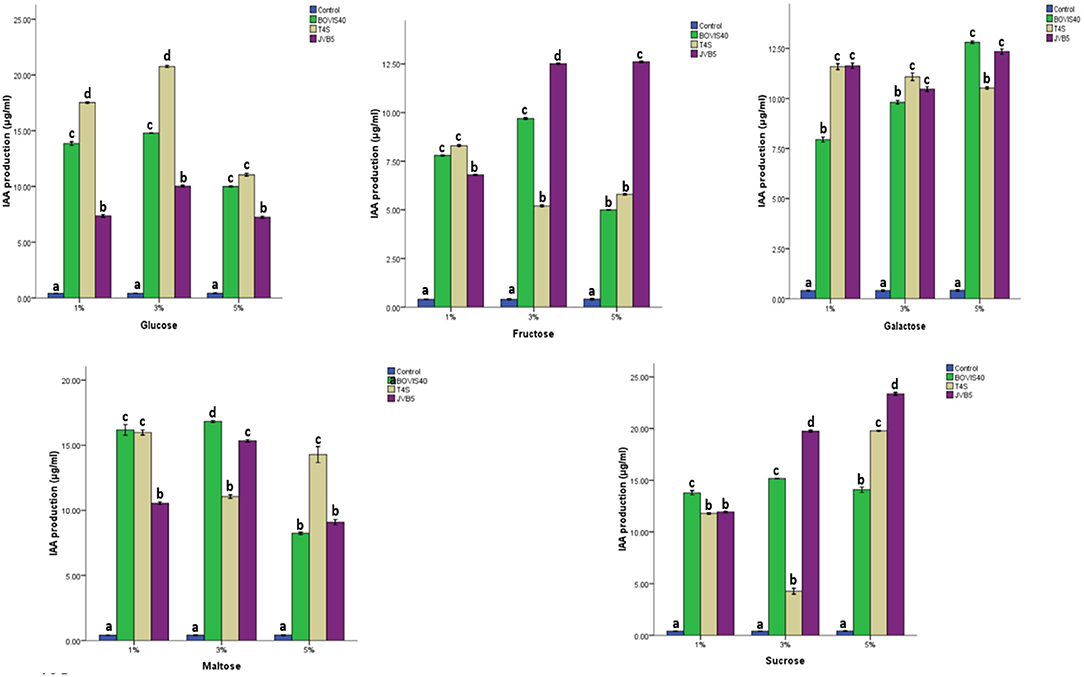

Figure 8 showed the effect of carbon source on IAA production by endophytic bacteria from sunflowers. The amount of IAA produced in the growth medium varied with the sugar concentration. A maximum IAA production of 23.36 and 20.72 μg/ml were recorded from S. maltophilia JVB5 and B. cereus T4S at 5% sucrose and 3% glucose, respectively.

Figure 8. Effect of different carbon source on IAA production by endophytic bacteria. The different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings.

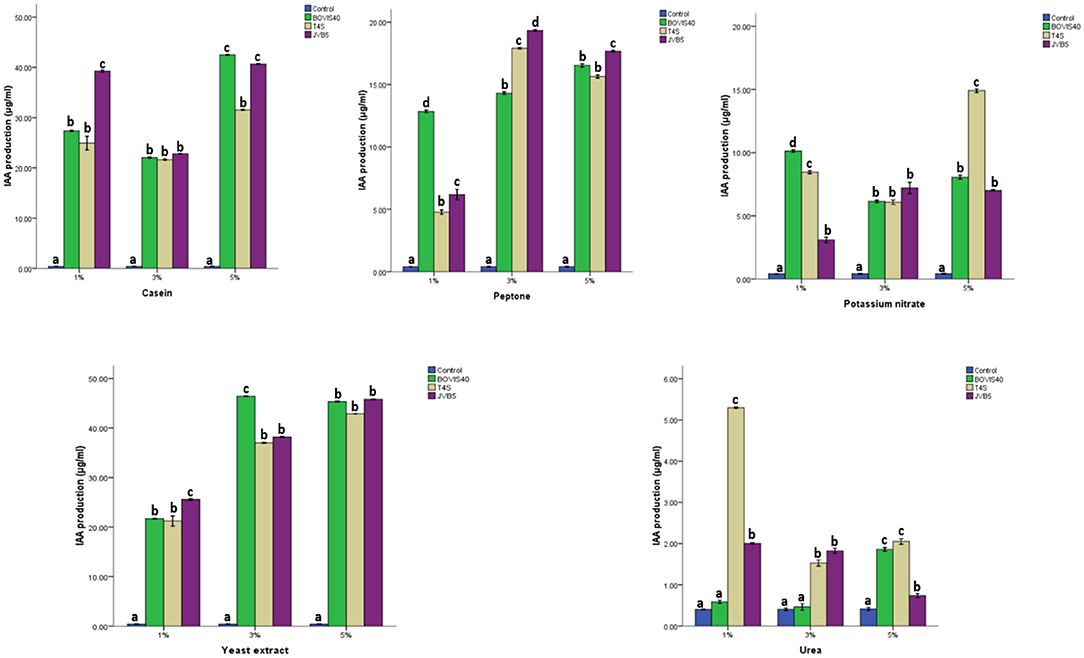

The effect of nitrogen source on IAA production by endophytic bacteria was presented in Figure 9. All the bacterial isolates exhibited IAA production >20 μg/ml in a medium amended with casein and yeast extracts. Maximum IAA production of 19.31 and 17.70 μg/ml were recorded from S. maltophilia JVB5 at 3 and 5% peptone. Similarly, B. cereus T4S exhibited a maximum IAA production of 17.94 μg/ml at 3% peptone. A high IAA production of 14.97 μg/ml was obtained from B. cereus T4S at 5% potassium nitrate. There was no significant difference in the IAA production by S. maltophilia JVB5 at 5% yeast extract. Similar results were obtained of S. indicatrix BOVIS40 and B. cereus T4S at 1% and B. cereus T4S and S. maltophilia JVB5 at 3% yeast extract, respectively. An increase in the amount of IAA production with an increase in yeast extract concentration was recorded. S. indicatrix BOVIS40 exhibited an IAA production increase from 21.71 to 45.34 μg/ml, while B. cereus T4S showed an increase in IAA production from 21.00 to 42.89 μg/ml and S. maltophilia JVB5 from 25.58 to 45.82 μg/ml, respectively. There was no significant difference in the amount of IAA produced by S. maltophilia JVB5 at 1 and 5% urea. B. cereus T4S displayed high IAA production of 5.30 μg/ml at 1% urea.

Figure 9. Effect of different nitrogen sources on IAA production by endophytic bacteria. The different alphabets indicate significant differences in triplicate readings.

The effect of IAA-producing bacteria S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. cereus T4S, and S. maltophilia JVB5 on sunflower seeds by inoculation were tested (Table 5). The percent increase of the number of lateral roots of 5.13, 6.97, and 1.58% were obtained from the inoculated sunflower seedling with bacterial strain S. indicatrix BOVIS40, B. cereus T4S, and S. maltophilia JVB5 compared to the un-inoculated sunflower seeds (control). A significant difference in the shoot and root length of sunflower seedlings compared with the control was recorded. The percentage increase of 9.09, 3.7, and 20.88% of root length and 6.23, 5.23, and 2.88% of shoot length were obtained from the inoculated sunflower seedlings compared with the un-inoculated sunflower seeds.

The need to ensure a safe environment for improved crop production has been a major concern, as insights into plant-microbe interactions remain crucial in developing eco-friendly agriculture. Due to the complex dynamics of biodiversity in the plant root environment, this can facilitate the recruitment of soil-root microbes to established microbial biomass in the endosphere (Liu et al., 2021). Plants harbor diverse agriculturally important endophytic microbes with notable plant growth-promoting traits and their exploration has been proven efficient in enhancing crop yield (Alkahtani et al., 2020). The ability of endophytic microbes to withstand drought stress or climate-induced abiotic stress for plant survival and nutrition can suggest their future exploration as a suitable candidate for formulating bioinoculants for sustainable agriculture (Khalil et al., 2021). The presence of endophytic bacteria in host plants and their ability to synthesize growth hormones can significantly enhance seedling growth, development, and elongation of lateral roots and cell differentiation (Shahzad et al., 2017).

In this study, the combination of culturing and molecular techniques in the characterization of sunflower roots and stem-associated endophytic bacteria has been reported (Tiwari and Thakur, 2014; Bahmani et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2022). The biochemical characterization reflected the most identifiable Gram-positive compared to the Gram-negative bacterial isolates. The screened twenty bacterial isolates showed multifunctional PGP traits. The bacteria identified in this study showed similarities to the previous studies by Ambrosini et al. (2016) and Schmidt et al. (2021), who reported similar bacteria from sunflowers. A study by Forchetti et al. (2007) reported the isolation of Bacillus from sunflower plants. Recent genomics has revealed plant growth promotion and stress tolerance attributes of Stenotrophomonas strain 169 (Ulrich et al., 2021). The bacteria identified agreed with the findings of Ambrosini et al. (2012), who isolated Stenotrophomonas spp. and Pseudomonas spp. from the root of sunflower.

The ability of endophytic bacteria to solubilize phosphate was evident from the work of researchers (Khamwan et al., 2018; Sánchez-Cruz et al., 2019; Alkahtani et al., 2020). Several endophytic bacterial genera, such as Stenotrophomonas, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas have been reported as phosphate solubilizers (Pandey et al., 2013). In this study, all the bacterial isolates displayed phosphate-solubilizing traits. Hence, these bacteria with greater potential can be harnessed as bio-input in both present and future agriculture. Diverse phosphate-solubilizing endophytic bacteria have been reported to increase phosphate levels in the soil (Alkahtani et al., 2020; Varga et al., 2020). Shahid et al. (2015) reported phosphate-solubilizing endophytic Bacillus sp. Ps-5 and Alcaligenes faecalis Ss-2, contribute to the sunflower yield. The results obtained from this study corroborate with Pandey et al. (2013) and Vandana et al. (2021), who reported phosphate-solubilizing endophytic Stenotrophomonas, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas from the root of sunflower, and soybean. The phosphate solubilization potential of bacterial isolates might depend on suitable growth conditions, genetic make-up, and limited nutrient supply (Youseif, 2018). Furthermore, the results here compared to previous studies confirmed the phosphate-solubilizing potential of sunflower-associated endophytic bacteria with promises in ensuring the bioavailability of soluble minerals in soils for plant nutrition.

Siderophore-producing microbes can protect plants by mitigating the effect of induced biotic and abiotic stresses (Ferreira et al., 2019). In this study, endophytic bacteria displayed varied siderophore production. The differences observed may be due to the bacterial viability and genetic make-up. Siderophore producing ability of endophytic bacteria associated with Vitis vinifera has been reported to increase mineral elements in the soil (Andreolli et al., 2016). Pourbabaee et al. (2018) reported the potential contribution of siderophore-producing bacteria to the growth and Fe ion concentration of sunflower under water stress.

The HCN production by bacteria can inhibit cell metabolism and electron transport chain, thus causing cell death. The HCN and siderophores production by endophytic bacteria can provide a competitive advantage by exploring them as biocontrol agents in plant disease suppressiveness (Igiehon et al., 2019). The results obtained in this study revealed HCN production by the endophytic bacteria. The ability of endophytic bacteria to produce ammonia with the underlining antibiosis activities has been reported (Khan et al., 2020). All the bacterial isolates produce ammonia and HCN, thus suggesting their possible use as a biocontrol agent. The HCN and ammonia production by the bacterial isolates conformed with the findings of Pandey et al. (2013) and Moin et al. (2020) who reported HCN, ammonia, and volatile antifungal metabolites biosynthesis by the endophytic bacterium Pseudomonas isolated from healthy sunflower plants. Additionally, the production of exopolysaccharides, signal molecules, multilayered cell wall structures, extracellular enzymes, and stress-resistant endospores by Bacillus spp., however, can contribute to their survival and ecological functions in diverse environments (Lyngwi et al., 2016).

Endophytic microbes can stand as a potential source of extracellular enzymes for industrial purposes due to catalytic activity, thermostability, low cost, organic substrates availability, etc. (Toghueo and Boyom, 2021). Screening of extracellular enzymes, such as cellulases, proteases, xylanases, chitinases, and xylanases from plant microbes has been documented (Alkahtani et al., 2020; Blibech et al., 2020). The substrate level and growth conditions may influence the enzyme production ability of the bacterial isolates in the growth medium (Yadav, 2017). With the biotechnological views, sunflower endophytic bacteria can be harnessed as a source of enzymes in the degradation of complex organic compounds and derivation of desirable bio-products.

IAA is considered the most important phytohormone that enhances plant root development and the rate of nutrient absorption for plant growth promotion (Ahmad et al., 2020). The ability of microbes to produce growth hormones can underline their multifunctional effects on improving agricultural productivity (Choudhury et al., 2021). Different bacterial species have been implicated in the synthesis of IAA depending on their ability to utilize the precursory substance L-tryptophan in the growth medium (Mustafa et al., 2018). The increase in the amount of IAA produced by the bacterial isolates in the IAA production medium (IPM) conformed with the findings of Chukwuneme et al. (2020), who reported the enhancement of IAA production by the addition of tryptophan to the IPM. IAA production by B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42 in a tryptophan-dependent medium and its effect on plant growth promotion have been reported (Idris et al., 2007). The IAA potential displayed by the bacterial isolates corroborates the findings of Bashir et al. (2020), who reported IAA production by Bacillus spp. isolated from sunflowers. Furthermore, endophytes, P. stutzeri, B. subtilis, S. maltophilia, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis native to the sunflower with IAA-producing potential have been reported to improve sunflower growth, seed germination, root elongation, and crop yield (Pandey et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2019).

Importantly, the time monitoring in a culture medium for metabolite biosynthesis is crucial in determining the biological activity of endophytic bacteria in the growth medium. Growing bacterial isolates in a medium amended with L-tryptophan as a precursor enhanced the IAA production based on their ability to utilize substrate in the medium through diverse IAA metabolic pathways (Hoseinzade et al., 2016). The geometric increase in IAA concentration with incubation time can be attributed to the ability of bacterial isolates to adjust and metabolize the substrate in the growing medium for maximum productivity. At low concentrations, a limited supply of substrate in the growth medium may affect the IAA-producing ability of the endophytic bacteria. In this study, a strong correlation between bacterial biomass and IAA production exists. A decrease in IAA concentration beyond the optimum level might be linked to the reduction in the amount of substrate or synthesis of lytic enzymes, such as IAA peroxidase and oxidase in the growing medium (Lebrazi et al., 2020). Nevertheless, bacterial growth under shaking conditions may influence IAA production due to agitation that allows the free flow of oxygen in the medium. Oxygen availability in the medium facilitates the conversion of tryptophan into auxins. Research findings on sunflower root endophytic bacteria and their optimization with incubation time have not been documented. The results obtained corroborate the conclusions of Myo et al. (2019) who reported IAA production of 82.36 μg/ml by Streptomyces fradiae NKZ-259 after 6 days of incubation. Interestingly, endophytic Rhizobium spp., Bacillus subtilis KA(1)5r and Pseudomonas mosselii with high IAA production at 216 and 96 h incubation have underlined their ability in promoting the growth of the medicinal herb Aconitum heterophyllum and wheat (Triticum spp.) (Emami et al., 2019; Lebrazi et al., 2020; Minakshi et al., 2020). Furthermore, IAA synthesis by actinomycetes in an IPM supplemented with suitable precursor L-tryptophan has been reported to occur via a tryptophan-dependent pathway or other similar pathways (Samaras et al., 2020).

The pH is an important factor that influences growth and microbial metabolism. At low or high pH, microbial activities may be affected (Alkahtani et al., 2020). Adjustment of pH in the growth medium to suitably favor bacterial growth can facilitate IAA biosynthesis. The differences observed in IAA production can be attributed to the pH of the medium and media composition (Widawati, 2020). A study by Myo et al. (2019) has reported maximum IAA production by Pantoea glomerans PVM, Klebsiella pneumoniae K8, and Streptomyces viridis CMU-H009 at pH ranging between pH 7 and 8. Here, the results obtained were similar to the findings of Widawati (2020), who reported optimum IAA production by B. siamensis at pH 7 and 8, respectively. Furthermore, changes in the temperature of the growth medium may influence IAA synthesis. A study by Emami et al. (2019) reported optimum IAA production of 23.62 μg/ml by Pseudomonas mosselii isolated from the root of wheat at 32°C.

Different carbon sources amended in the IAA-producing medium can serve as energy sources to enhance the overall efficiency of recycling co-factor in the cells for IAA biosynthesis (Myo et al., 2019). The differences observed in the IAA production by the bacterial isolates can be attributed to the carbon source, concentration, and utilization of the substrate (Khan et al., 2020). Usually, a growing medium amended with monosaccharide sugar compared to di-or-polysaccharides can contribute to high IAA production based on the ability of endophytic microbes to assimilate. In addition, the utilization of monosaccharide sugars by most bacteria has been linked to high IAA production (Emami et al., 2019). However, the results from this study revealed high IAA concentration in IPM amended with sucrose, thus suggesting sucrose as a sole carbon source. The differences observed in the IAA concentrations may depend on the sugar source and the ability of the bacteria to utilize them for growth (Oliveira et al., 2021). An increase in IAA production in the IPM amended with sucrose agrees with the findings of Huu et al. (2015) and Payel et al. (2017), who reported an increase in IAA production by B. subtilis and Pantoea agglomerans on sucrose amended media. Also, results from this study corroborate the findings of Bharucha et al. (2013) who reported maximum IAA production by P. putida UB1 in a medium amended with sucrose. Lactose and glucose have also been reported as preferred sugars for maximum IAA production by Enterobacter sp. and Rhizobium (Basu and Ghosh, 2001; Nutaratat et al., 2017). Similarly, reports on maximum IAA production by root endophytic bacteria, such as Rhizobium P2, Bacillus spp., Pantoea spp., and Pseudomonas mosselii in a medium amended with sucrose, glucose, and maltose have been documented to enhance IAA production (Apine and Jadhav, 2011; Kucuk and Cevheri, 2016; Emami et al., 2019).

The addition of various nitrogen sources increased IAA production compared to the control medium. The soluble nitrogen source in the growth medium remains the key factor for bacterial growth and metabolite biosynthesis (Khan et al., 2017). The addition of various nitrogen sources to the IPM influences the rate of IAA production (Shahzad et al., 2017). Casein and yeast extract yielded high IAA production (>20 μg/ml) compared to other nitrogen sources. Like other parameters tested, varying concentrations of nitrogen source added to the growing medium can influence the amount of IAA biosynthesis (Emami et al., 2019). IAA production by rhizobacteria inhabiting the root of leguminous plants in a growing medium amended with glutamic acid and L-asparagine as a nitrogen source has been reported (Zhao et al., 2020). The results from this study corroborate the findings of Balaji et al. (2012), who reported yeast extract as the best nitrogen source for Pseudomonas species with an IAA concentration of 210 μg/ml. Also, Emami et al. (2019) reported IAA production of 23.66 μg/ml by Pseudomonas in a yeast extract amended medium. Furthermore, the addition of tryptone, beef extract, and peptone with varied IAA production can contribute to the bacterial lifestyle in the synthesis of phytohormones (Widawati, 2020).

In this study, endophytic bacteria with promising phytostimulant activities, i.e., B. cereus T4S, S. maltophilia JVB5, and S. indicatrix BOVIS40 were selected and their in vitro effect was assessed on sunflower seedlings growth. Inoculation of Sesbania aculeate, Brassica campestris, Vigna radiate, and Pennisetum americanum with endophytic bacteria Azotobacter spp., Bacillus spp., Azospirillum brasilense, and Pseudomonas putida, which increase adventitious root development, shoot, root length, and chlorophyll pigmentation has experimented (Khan Latif et al., 2016). The observed variation in the weight, root, and shoot length of rice and maize inoculated with Bacillus and Pseudomonas has been presumed to be influenced by IAA production (Karnwal, 2017, 2018). Most Bacillus spp. isolated from the root endosphere has been implicated in nitrogen fixation in legumes with a positive influence on seedling's growth (Bertani et al., 2016). An increase in rice shoot, root, and leaf length due to phytohormone production by the bacterial isolates contributes to crop production. Furthermore, the rooting potential of Agrobacterium rhizogenes in jujube's root has been reported (Lebrazi et al., 2020).

This study provides information on the in vitro screening of endophytic bacteria associated with sunflower. The PGP traits, such as IAA, ammonia production, exopolysaccharide, hydrogen cyanide, siderophore, and enzyme production exhibited by the endophytic bacteria, can underline their potential in plant growth promotion and protection from the biotic and abiotic stresses. The IAA production by the identifiable endophytic bacteria can contribute to sunflower rooting for nutrient and water absorption from the soil. The significant differences observed in the inoculated sunflower seedling compared to un-inoculated showed the tendencies of these bacteria in plant growth promotion. Hence, based on the high siderophore potential of B. cereus T4S among the screened bacterial isolates with multifunctional attributes, this bacterium can be explored for sunflower cultivation.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI (accession: MW265413-MW265431 and MW261910).

BSA, ASA, and OOB designed the study. BSA managed the literature searches, carried out the laboratory work, interpreted the results, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and revised and formatted the manuscript. ASA assisted in the result analysis and review of various drafts. OOB provided academic input, thoroughly critiqued the manuscript, proofread the draft, and secured funds for the research. All authors approved the article for publication.

This study was funded by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (UID: 123634; 132595), awarded to OOB. BSA acknowledged the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the World Academy of Science (NRF-TWAS) African Renaissance for a Doctoral stipend (UID: 116100).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ASA is grateful to the North-West University, South Africa, for the postdoctoral fellowship award.

Abdel-Latef, A. A. H., Omer, A. M., Badawy, A. A., Osman, M. S., and Ragaey, M. M. (2021). Strategy of salt tolerance and interactive impact of Azotobacter chroococcum and/or Alcaligenes faecalis inoculation on canola (Brassica napus L.) plants grown in saline soil. Plants 10, 110. doi: 10.3390/plants10010110

Adeleke, B. S., and Babalola, O. O. (2020). Oilseed crop sunflower (Helianthus annuus) as a source of food: nutritional and health benefits. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 4666–4684. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1783

Adeleke, B. S., and Babalola, O. O. (2022). Meta-omics of endophytic microbes in agricultural biotechnology. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 42, 102332. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102332

Ahmad, E., Sharma, S. K., and Sharma, P. K. (2020). Deciphering operation of tryptophan-independent pathway in high indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) producing Micrococcus aloeverae DCB-20. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 367, fnaa190. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnaa190

Alkahtani, M. D., Fouda, A., Attia, K. A., Al-Otaibi, F., Eid, A. M., Ewais, E. E. D., et al. (2020). Isolation and characterization of plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria from desert plants and their application as bioinoculants for sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 10, 1325. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10091325

Ambrosini, A., Beneduzi, A., Stefanski, T., Pinheiro, F. G., Vargas, L. K., and Passaglia, L. M. (2012). Screening of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolated from sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Plant Soil. 356, 245–264. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-1079-1

Ambrosini, A., Stefanski, T., Lisboa, B., Beneduzi, A., Vargas, L., and Passaglia, L. (2016). Diazotrophic bacilli isolated from the sunflower rhizosphere and the potential of Bacillus mycoides B38V as biofertiliser. Ann. Appl. Biol. 168, 93–110. doi: 10.1111/aab.12245

Andreolli, M., Lampis, S., Zapparoli, G., Angelini, E., and Vallini, G. (2016). Diversity of bacterial endophytes in 3 and 15 year-old grapevines of Vitis vinifera cv. Corvina and their potential for plant growth promotion and phytopathogen control. Microbiol. Res. 183, 42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.009

Apine, O. A., and Jadhav, J. P. (2011). Optimization of medium for indole-3-acetic acid production using Pantoea agglomerans strain PVM. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 1235–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04976.x

Bahmani, K., Hasanzadeh, N., Harighi, B., and Marefat, A. (2021). Isolation and identification of endophytic bacteria from potato tissues and their effects as biological control agents against bacterial wilt. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 116, 101692. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101692

Balaji, N., Lavanya, S., Muthamizhselvi, S., and Tamilarasan, K. (2012). Optimization of fermentation condition for indole acetic acid production by Pseudomonas species. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res. 3, 797–803.

Bashir, S., Iqbal, A., and Hasnain, S. (2020). Comparative analysis of endophytic bacterial diversity between two varieties of sunflower Helianthus annuus with their PGP evaluation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.010

Basu, A., Prasad, P., Das, S. N., Kalam, S., Sayyed, R., Reddy, M., et al. (2021). Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) as green bioinoculants: recent developments, constraints, and prospects. Sustainability 13, 1140. doi: 10.3390/su13031140

Basu, P., and Ghosh, A. (2001). Production of indole acetic acid in culture by a Rhizobium species from the root nodules of a monocotyledonous tree, Roystonea regia. Acta Biotechnol. 21, 65–72. doi: 10.1002/1521-3846(200102)21:1<65::AID-ABIO65>3.0.CO;2-#

Bertani, I., Abbruscato, P., Piffanelli, P., Subramoni, S., and Venturi, V. (2016). Rice bacterial endophytes: isolation of a collection, identification of beneficial strains and microbiome analysis. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 8, 388–398. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12403

Bharucha, U., Patel, K., and Trivedi, U. B. (2013). Optimization of indole acetic acid production by Pseudomonas putida UB1 and its effect as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on mustard (Brassica nigra). Agric. Res. 2, 215–221. doi: 10.1007/s40003-013-0065-7

Bhutani, N., Maheshwari, R., Kumar, P., and Suneja, P. (2021). Bioprospecting of endophytic bacteria from nodules and roots of Vigna radiata, Vigna unguiculata and Cajanus cajan for their potential use as bioinoculants. Plant Gene 28, 100326. doi: 10.1016/j.plgene.2021.100326

Blibech, M., Farhat-Khemakhem, A., Kriaa, M., Aslouj, R., Boukhris, I., Alghamdi, O. A., et al. (2020). Optimization of β-mannanase production by Bacillus subtilis US191 using economical agricultural substrates. Biotechnol. Progr. 36, e2989. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2989

Chandra, S., Askari, K., and Kumari, M. (2018). Optimization of indole acetic acid production by isolated bacteria from Stevia rebaudiana rhizosphere and its effects on plant growth. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 16, 581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2018.09.001

Choudhury, A. R., Choi, J., Walitang, D. I., Trivedi, P., Lee, Y., and Sa, T. (2021). ACC deaminase and indole acetic acid producing endophytic bacterial co-inoculation improves physiological traits of red pepper (Capsicum annum L.) under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 267, 153544. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153544

Chukwuneme, C. F., Babalola, O. O., Kutu, F. R., and Ojuederie, O. B. (2020). Characterization of actinomycetes isolates for plant growth promoting traits and their effects on drought tolerance in maize. J. Plant Interac. 15, 93–105. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2020.1752833

de Oliveira, D. A., Ferreira, S. D. C., Carrera, D. L. R., Serrao, C. P., Callegari, D. M., et al. (2021). Characterization of Pseudomonas bacteria of Piper tuberculatum regarding the production of potentially bio-stimulating compounds for plant growth. Acta Amaz. 51, 10–19. doi: 10.1590/1809-4392202002311

Emami, S., Alikhani, H. A., Pourbabaei, A. A., Etesami, H., Sarmadian, F., and Motessharezadeh, B. (2019). Assessment of the potential of indole-3-acetic acid producing bacteria to manage chemical fertilizers application. Int. J. Environ. Res. 13, 603–611. doi: 10.1007/s41742-019-00197-6

Ferreira, M. J., Silva, H., and Cunha, A. (2019). Siderophore-producing rhizobacteria as a promising tool for empowering plants to cope with iron limitation in saline soils: a review. Pedosphere 29, 409–420. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(19)60810-6

Forchetti, G., Masciarelli, O., Alemano, S., Alvarez, D., and Abdala, G. (2007). Endophytic bacteria in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.): isolation, characterization, and production of jasmonates and abscisic acid in culture medium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76, 1145–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1077-7

Gutierrez, C. K., Matsui, G. Y., Lincoln, D. E., and Lovell, C. R. (2009). Production of the phytohormone indole-3-acetic acid by estuarine species of the genus Vibrio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2253–2258. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02072-08

Hoseinzade, H., Ardakani, M. R., Shahdi, A., Rahmani, H. A., Noormohammadi, G., and Miransari, M. (2016). Rice (Oryza sativa L.) nutrient management using mycorrhizal fungi and endophytic Herbaspirillum seropedicae. J. Integr. Agric. 15, 1385–1394. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61241-2

Huu, D. T. T., Kim Cuc, N. T., and Cuong, P. V. (2015). Optimization of indole-3-acetic acid production by Bacillus subtilisTIB6 using responses surface methodology. Int. J. Dev. Res. 5, 4036–4042.

Idris, E. E., Iglesias, D. J., Talon, M., and Borriss, R. (2007). Tryptophan-dependent production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) affects level of plant growth promotion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 619–626. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-6-0619

Igiehon, N. O., Babalola, O. O., and Aremu, B. R. (2019). Genomic insights into plant growth promoting rhizobia capable of enhancing soybean germination under drought stress. BMC Microbiol. 19, 159. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1536-1

Karnwal, A.. (2017). Isolation and identification of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from maize (Zea mays L.) rhizosphere and their plant growth promoting effect on rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Protect. Res. 57, 144–151. doi: 10.1515/jppr-2017-0020

Karnwal, A.. (2018). Use of bio-chemical surfactant producing endophytic bacteria isolated from rice root for heavy metal bioremediation. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. Sci. 41, 699–714.

Khalil, A. M. A., Hassan, S. E.-D., Alsharif, S. M., Eid, A. M., Ewais, E. E.-D., Azab, E., et al. (2021). Isolation and characterization of fungal endophytes isolated from medicinal plant Ephedra pachyclada as plant growth-promoting. Biomolecules 11, 140. doi: 10.3390/biom11020140

Khamwan, S., Boonlue, S., Riddech, N., Jogloy, S., and Mongkolthanaruk, W. (2018). Characterization of endophytic bacteria and their response to plant growth promotion in Helianthus tuberosus L. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 13, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2017.12.007

Khan Latif, A., Ahmed Halo, B., Elyassi, A., Ali, S., Al-Hosni, K., Hussain, J., et al. (2016). Indole acetic acid and ACC deaminase from endophytic bacteria improves the growth of Solarium lycopersicum. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 21, 58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2016.02.001

Khan, A. L., Gilani, S. A., Waqas, M., Al-Hosni, K., Al-Khiziri, S., Kim, Y.-H., et al. (2017). Endophytes from medicinal plants and their potential for producing indole acetic acid, improving seed germination and mitigating oxidative stress. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 18, 125–137. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500271

Khan, M. S., Gao, J., Zhang, M., Chen, X., Du, Y., Yang, F., et al. (2020). Isolation and characterization of plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria Bacillus stratosphericus LW-03 from Lilium wardii. Biotechnology 10, 305. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02294-2

Kucuk, C., and Cevheri, C. (2016). Indole acetic acid production by Rhizobium sp. isolated from pea (Pisum sativum L. ssp. arvense). Turk. J. Life Sci. 1, 43–45.

Lally, R. D., Galbally, P., Moreira, A. S., Spink, J., Ryan, D., Germaine, K. J., et al. (2017). Application of endophytic Pseudomonas fluorescens and a bacterial consortium to Brassica napus can increase plant height and biomass under greenhouse and field conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2193. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02193

Lebrazi, S., Niehaus, K., Bednarz, H., Fadil, M., Chraibi, M., and Fikri-Benbrahim, K. (2020). Screening and optimization of indole-3-acetic acid production and phosphate solubilization by rhizobacterial strains isolated from Acacia cyanophylla root nodules and their effects on its plant growth. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 18, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s43141-020-00090-2

Liu, Y., Gao, J., Bai, Z., Wu, S., Li, X., Wang, N., et al. (2021). Unraveling mechanisms and impact of microbial recruitment on oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) and the rhizosphere mediated by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Microorganisms. 9, 161. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010161

Lyngwi, N. A., Nongkhlaw, M., Kalita, D., and Joshi, S. R. (2016). Bioprospecting of plant growth promoting Bacilli and related genera prevalent in soils of pristine sacred groves: biochemical and molecular approach. PLoS ONE 11, e0152951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152951

Majeed, A., Abbasi, M. K., Hameed, S., Imran, A., Naqqash, T., and Hanif, M.K. (2018). Isolation and characterization of sunflower associated bacterial strain with broad spectrum plant growth promoting traits. Int. J. Biosci. 13, 110–123. doi: 10.12692/ijb/13.2.110-123

Marra, L. M., Oliveira, S. M. D., Soares, C. R. F. S., and Moreira, F. M. D. S. (2011). Solubilisation of inorganic phosphates by inoculant strains from tropical legumes. Sci. Agric. 68, 603–609. doi: 10.1590/S0103-90162011000500015

Minakshi, S. S., Sood, G., and Chauhan, A. (2020). Optimization of IAA production and P-solubilization potential in Bacillus subtilis KA (1) 5r isolated from the medicinal herb Aconitum heterophyllum-growing in Western Himalaya, India. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 9, 2008–2015.

Moin, S., Ali, S. A., Hasan, K. A., Tariq, A., Sultana, V., Ara, J., et al. (2020). Managing the root rot disease of sunflower with endophytic fluorescent Pseudomonas associated with healthy plants. Crop Protec. 130, 105066. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.105066

Mowafy, A. M., Fawzy, M. M., Gebreil, A., and Elsayed, A. (2021). Endophytic Bacillus, Enterobacter, and Klebsiella enhance the growth and yield of maize. Acta Agric. Scandinavica. 71, 237–246. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2021.1880621

Mukherjee, A., Gaurav, A. K., Patel, A. K., Singh, S., Chouhan, G. K., Lepcha, A., et al. (2021). Unlocking the potential plant growth-promoting properties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seed endophytes bio-inoculants for improving soil health and crop production. Land Degr. Dev. 32, 4362–4374. doi: 10.1002/ldr.4042

Mustafa, A., Imran, M., Ashraf, M., and Mahmood, K. (2018). Perspectives of using l-tryptophan for improving productivity of agricultural crops: a review. Pedosphere 28, 16–34. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(18)60002-5

Myo, E. M., Ge, B., Ma, J., Cui, H., Liu, B., Shi, L., et al. (2019). Indole-3-acetic acid production by Streptomyces fradiae NKZ-259 and its formulation to enhance plant growth. BMC Microbiol. 19, 155. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1528-1

Nascimento, F. X., Hernandez, A. G., Glick, B. R., and Rossi, M. J. (2020). The extreme plant-growth-promoting properties of Pantoea phytobeneficialis MSR2 revealed by functional and genomic analysis. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 1341–1355. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14946

Nutaratat, P., Monprasit, A., and Srisuk, N. (2017). High-yield production of indole-3-acetic acid by Enterobacter sp. DMKU-RP206, a rice phyllosphere bacterium that possesses plant growth-promoting traits. Biotechnology 7,305. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0937-9

Pandey, R., Chavan, P., Walokar, N., Sharma, N., Tripathi, V., and Khetmalas, M. (2013). Pseudomonas stutzeri RP1: a versatile plant growth promoting endorhizospheric bacteria inhabiting sunflower (Helianthus annus). Res. J. Biotechnol. 8, 48–55.

Payel, C., Arshad, J., and Pradipta, S. (2017). Optimization of phytostimulatory potential in Bacillus toyonensis isolated from tea plant rhizosphere soil of Nilgiri Hills, India. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Invention. 6, 13–18.

Pourbabaee, A. A., Shoaibi, F., Emami, S., and Alikhani, H. A. (2018). The potential contribution of siderophore producing bacteria on growth and Fe ion concentration of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) under water stress. J. Plant Nutr. 41, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2017.1406112

Premono, M. E., Moawad, A., and Vlek, P. (1996). Effect of phosphate-solubilizing Pseudomonas putida on the growth of maize and its survival in the rhizosphere. Indones. J. Crop Sci. 11, 13–23.

Preyanga, R., Anandham, R., Krishnamoorthy, R., Senthilkumar, M., Gopal, N., Vellaikumar, A., et al. (2021). Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) nodule Rhizobium and passenger endophytic bacterial cultivable diversity and their impact on plant growth promotion. Rhizosphere 17, 100309. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100309

Samaras, A., Nikolaidis, M., Antequera-Gómez, M. L., Cámara-Almirón, J., Romero, D., Moschakis, T., et al. (2020). Whole genome sequencing and root colonization studies reveal novel insights in the biocontrol potential and growth promotion by Bacillus subtilis MBI 600 on cucumber. Front. Microbiol. 11, 600393. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.600393

Sánchez-Cruz, R., Tpia Vázquez, I., Batista-García, R. A., Méndez-Santiago, E. W., Sánchez-Carbente, M. D. R., Leija, A., et al. (2019). Isolation and characterization of endophytes from nodules of Mimosa pudica with biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Res. 218, 76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.09.008

Schmidt, C., Mrnka, L., Loveck,á, P., Frantík, T., Fenclov,á, M., Demnerov,á, K., et al. (2021). Bacterial and fungal endophyte communities in healthy and diseased oilseed rape and their potential for biocontrol of Sclerotinia and Phoma disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 3810. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81937-7

Seiler, G. J., Qi, L. L., and Marek, L. F. (2017). Utilization of sunflower crop wild relatives for cultivated sunflower improvement. Crop Sci. 57, 1083–1101. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2016.10.0856

Shah, D., Khan, M. S., Aziz, S., Ali, H., and Pecoraro, L. (2022). Molecular and biochemical characterization, antimicrobial activity, stress tolerance, and plant growth-promoting effect of endophytic bacteria isolated from wheat varieties. Microorganisms 10, 21. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10010021

Shahid, M., Hameed, S., Tariq, M., Zafar, M., Ali, A., and Ahmad, N. (2015). Characterization of mineral phosphate-solubilizing bacteria for enhanced sunflower growth and yield-attributing traits. Ann. Microbiol. 65, 1525–1536. doi: 10.1007/s13213-014-0991-z

Shahzad, R., Waqas, M., Khan, A. L., Al-Hosni, K., Kang, S.-M., Seo, C.-W., et al. (2017). Indole acetic acid production and plant growth promoting potential of bacterial endophytes isolated from rice (Oryza sativa L.) seeds. Acta Biol. Hung. 68, 175–186. doi: 10.1556/018.68.2017.2.5

Singh, S., Gowtham, H., Murali, M., Hariprasad, P., Lakshmeesha, T., Murthy, K. N., et al. (2019). Plant growth promoting ability of ACC deaminase producing rhizobacteria native to sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 18, 101089. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101089

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., and Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197

Tiwari, K., and Thakur, H. K. (2014). Diversity and molecular characterization of dominant Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (JNU-001) endophytic bacterial strains isolated from native Neem varieties of Sanganer region of Rajasthan. J. Biodivers. Bioprospect. Dev. 1, 1000115. doi: 10.4172/2376-0214.1000115

Toghueo, R. M. K., and Boyom, F. F. (2021). “Endophyte enzymes and their applications in industries.” In: Bioprospecting of Plant Biodiversity for Industrial Molecules, eds S. K. Upadhyay, and S. P. Singh (John Wiley & Sons Ltd), 99–129. doi: 10.1002/9781119718017.ch6

Ullah, S., Qureshi, M. A., Ali, M. A., Mujeeb, F., and Yasin, S. (2017). Comparative potential of Rhizobium species for the growth promotion of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Euras. J. Soil Sci. 6, 189–189. doi: 10.18393/ejss.286694

Ulrich, K., Kube, M., Becker, R., Schneck, V., and Ulrich, A. (2021). Genomic analysis of the endophytic Stenotrophomonas strain 169 reveals features related to plant-growth promotion and stress tolerance. Front. Microbiol. 12, 687463. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.687463

Vandana, U., Rajkumari, J., Singha, L., Satish, L., Alavilli, H., Sudheer, P., et al. (2021). The endophytic microbiome as a hotspot of synergistic interactions, with prospects of plant growth promotion. Biology 10, 101. doi: 10.3390/biology10020101

Varga, T., Hixson, K. K., Ahkami, A. H., Sher, A. W., Barnes, M. E., Chu, R. K., et al. (2020). Endophyte-promoted phosphorus solubilization in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 567918. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.567918

Widawati, S.. (2020). Isolation of indole acetic acid (IAA) producing Bacillus siamensis from peat and optimization of the culture conditions for maximum IAA production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 572, 012025. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/572/1/012025

Yadav, A. N.. (2017). Agriculturally important microbiomes: biodiversity and multifarious PGP attributes for amelioration of diverse abiotic stresses in crops for sustainable agriculture. Biomed. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 1, 861–864. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000321

Youseif, S. H.. (2018). Genetic diversity of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their effects on the growth of maize plants under greenhouse conditions. Ann. Agric. Sci. 63, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aoas.2018.04.002

Zaman, N. R., Chowdhury, U. F., Reza, R. N., Chowdhury, F. T., Sarker, M., Hossain, M. M., et al. (2021). Plant growth promoting endophyte Burkholderia contaminans NZ antagonizes phytopathogen Macrophomina phaseolina through melanin synthesis and pyrrolnitrin inhibition. PLoS ONE 16, e0257863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257863

Keywords: bioinoculants, Helianthus annuus, plant growth promotion, seed inoculation, South Africa, sustainable agriculture

Citation: Adeleke BS, Ayangbenro AS and Babalola OO (2022) In vitro Screening of Sunflower Associated Endophytic Bacteria With Plant Growth-Promoting Traits. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:903114. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.903114

Received: 23 March 2022; Accepted: 08 June 2022;

Published: 07 July 2022.

Edited by:

Subhash Babu, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaReviewed by:

Sushil K. Sharma, National Institute of Biotic Stress Management, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Adeleke, Ayangbenro and Babalola. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olubukola Oluranti Babalola, b2x1YnVrb2xhLmJhYmFsb2xhQG53dS5hYy56YQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.