- 1New Use Agriculture and Natural Plant Products Program, Department of Plant Biology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

- 2Center for Agricultural Food Ecosystems, The New Jersey Institute for Food, Nutrition, and Health, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

- 3Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, Kakamega, Kenya

- 4Academic Model Providing Access to HealthCare, Eldoret, Kenya

- 5Department of Urban-Global Public Health, Rutgers School of Public Health, Newark, NJ, United States

- 6Department of Nutritional Sciences, Program in International Nutrition, New Jersey Institute for Food, Nutrition, and Health, Center for Childhood Nutrition Education and Research, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

Malnutrition and food security continue to be major concerns in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In Western Kenya, it is estimated that the double burden of malnutrition impacts 19% of adults and 13–17% of households. One potential solution to help address the concern is increased consumption of nutrient-dense African Indigenous Vegetables (AIVs). The objectives of this study were to: (i) document current methods used for preparation and consumption of AIVs; (ii) identify barriers and facilitators of AIVs consumption and preparation; and (iii) identify a package of interventions to increase the consumption of AIVs to promote healthy diets. This study used qualitative data collected from 145 individual farmers (78 female and 67 male) in 14 focus group discussions (FGDs) using a semi-structured survey instrument. Most farmers reported that they prepared AIVs using the traditional method of boiling and/or pan-cooking with oil, tomato, and onion. However, there were large discrepancies between reported cooking times, with some as little as 1–5 min and others as long as 2 h. This is of importance as longer cooking times may decrease the overall nutritional quality of the final dish. In addition, there were seasonal differences in the reported barriers and facilitators relative to the preparation and consumption of AIVs implying that the barriers are situational and could be modified through context-specific interventions delivered seasonally to help mitigate such barriers. Key barriers were lack of availability and limited affordability, due to an increase cost, of AIVs during the dry season, poor taste and monotonous diets, and perceived negative health outcomes (e.g., ulcers, skin rashes). Key facilitators included availability and affordability during peak-season and particularly when self-produced, ease of preparation, and beneficial health attributes (e.g., build blood, contains vitamins and minerals). To promote healthy diets within at risk-populations in Western Kenya, the findings suggest several interventions to promote the preparation and consumption of AIVs. These include improved household production to subsequently improve affordability and availability of AIVs, improved cooking methods and recipes that excite the family members to consume these dishes with AIVs, and the promotion of the beneficial heath attributes of AIVs while actively dispelling any perceived negative health consequences of their consumption.

Introduction

Malnutrition measured by stunting increased by 30% between 1990 and 2013 and thus remains relatively high in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (FAO, 2021). Moreover, food system shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated undernutrition (FAO, 2021). It is estimated that in 2020, one in five individuals faced hunger in Africa, an increase of 3 percentage points as compared to previous years (FAO, 2021). It is common that such communities experience more than one form of malnutrition and the co-existence of undernutrition and overweight/obesity is often referred to as the double burden of malnutrition (DB) (Popkin et al., 2012). In parts of SSA, the DB has been attributed to nutrition transitions (Kimani-Murage et al., 2015; Ajayi et al., 2016), where urbanization, economic growth, and dietary shifts and changes in physical activity patterns, increase the prevalence of malnutrition (Raschke-Cheema and Cheema, 2008; Popkin et al., 2012; Rousham et al., 2020). It is currently estimated that in Western Kenya, DB is found in 19% of adults and 13–17% of households (Fongar et al., 2019). Such findings provide a compelling reason to ensure that agricultural and nutrition behavior change interventions as well as policy work toward increasing micronutrient intake without increasing caloric intake within populations that are already consuming sufficient energy.

African Indigenous Vegetables (AIVs) are an underutilized source of micro and macro-nutrients that can contribute to a healthy diet. AIVs are defined as vegetables that either originated in Africa or have a long history of cultivation and domestication to the conditions and are acceptable through custom, habit, or tradition (Ambrose-Oji, 2009; Towns and Shackleton, 2018). AIVs such as African nightshade (Solanum scabrum), spider plant (Cleome gynandra), amaranth (Amaranthus spp.), and cowpea leaves (Vigna unguiculata), are culturally accepted (Weller et al., 2015; Hoffman et al., 2018; Hunter et al., 2019; Simon et al., 2020, 2021), nutrient dense (Abukutsa-Onyango et al., 2010; Kamga et al., 2013) vegetables that may offer a partial solution to addressing malnutrition in SSA by contributing to micro and macro-nutrient intakes without introducing excess calories. Furthermore, AIVs are adapted to the local environmental conditions (Abukutsa-Onyango, 2010; Muhanji et al., 2011; Hunter et al., 2019) and some are even considered “survivor plants” due to their tolerance to temperature and precipitation extremes posing them as a sustainably produced and a climate resilient food source of micro and macro-nutrients (Chivenge et al., 2015; Stöber et al., 2017). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture programs attempt to increase the availability, affordability, and accessibility of nutritious foods, such as AIVs, which can contribute to a healthy diet; however, these programs may not take into consideration the broader barriers and facilitators within the external and personal food environment that may contribute to the preparation and consumption of such foods (Gillespie and Bold, 2017; Maestre et al., 2017).

There are dimensions within the external and personal food environment that may create barriers and facilitators that influence the preparation and consumption of AIVs. The external food environment includes external dimensions such as food availability, prices, vendor and product properties, and marketing and regulation within a given context; while the personal food environment includes internal dimensions such as accessibility, affordability, convenience and desirability at the individual level (Turner et al., 2017). Research suggests that AIVs need to be available, affordable (Muhanji et al., 2011), desirable, and palatable/tasty (Hartmann et al., 2013) in order for increased household adoption and consumption.

Increased consumption of AIVs (Kamga et al., 2013; Neugart et al., 2017) and thoughtful preparation techniques that maximize taste and flavor while preserving nutrition (Yang and Tsou, 2006; Mepba et al., 2007) can lead to improved micronutrient intake and subsequently improved health status amongst vulnerable populations (Ochieng et al., 2018). However, current literature is limited on the barriers and facilitators for preparation and consumption of AIVs. This study fills this gap by analyzing context specific semi-structured focus group discussions aimed to identify these barriers and facilitators. Through a qualitative exploration, the study objectives were to document current methods used for preparation and consumption of AIVs; identify barriers and facilitators of AIV preparation and consumption; and identify a package of interventions to increase the consumption of AIVs.

Methods

Study Setting

This study was part of a larger research initiative to examine the production and consumption of AIVs in Kenya supported by the USAID Laboratory for Horticulture Innovation (Odendo et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2020, 2021). This study was conducted in four counties in Western Kenya: Bungoma, Busia, Kisumu, and Nandi. Agriculture is the main economic activity in the study counties (Recha, 2018; Welfle et al., 2020). The staple food crop is maize, often consumed as stiff porridge (ugali) alongside cooked leaves of AIVs (Maundu et al., 2009). These counties represent the four different regions in Western Kenya that were engaged in the larger study. However, individuals who participated in this study did not participate in the large Horticulture Innovation Lab project as the intention of this study was to gather qualitative data relative to barriers and facilitators of preparation and consumption of AIVs without influence from recruitment or participation in the larger study.

The study applied qualitative research methodology. Qualitative research is especially appropriate for answering research questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focusing on intervention improvement (Busetto et al., 2020). For this study, qualitative approach was suitable because it was an exploratory study that sought to explain “how” and “why” a particular phenomenon or behavior (preparation and consumption of AIVs), operates in a particular context. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were used to identify the barriers and facilitators of preparation and consumption of AIVs in Western Kenya (Cooper and Endacott, 2007). A semi-structured survey instrument was designed to help in data collection. The protocol for this sub-study received ethical approval from Rutgers University, the State University of New Jersey (New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and Academic Model for Providing Access to Healthcare (Eldoret, Kenya). All study participants provided informed oral consent to participate in the study.

Study Participants

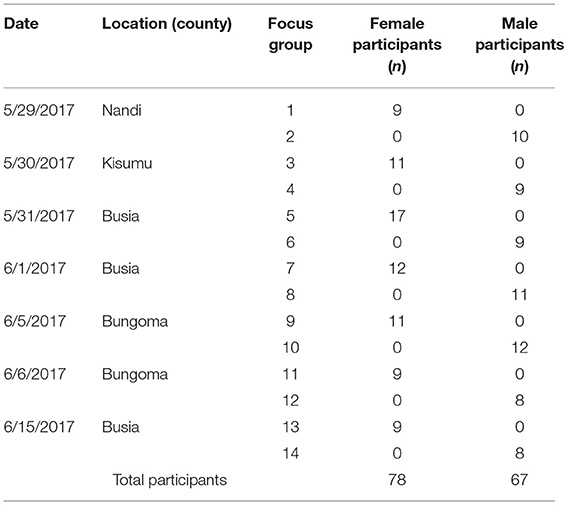

This study was conducted in May and June of 2017 and involved 145 individual farmers (n = 78 female and n = 67 male) in 14 FGDs from the four counties in Western Kenya. The study design allowed for two FGDs per sex in each of the four counties except for Busia county where a third FGD was conducted. The larger USAID study recruited a higher proportion of participants from Busia county; therefore, to represent this within the ethnographic study, a third FGD occurred in Busia. The FGDs were conducted by sex (n = 7 male and n = 7 female FGDs) to allow free communication, especially for females given the cultural gender dynamics in the communities. The FGDs ranged from 8 to 12 participants with an average of 10 participants to maximize data output and ensure that all participants had ample opportunity to participate while being conscientious of time (Tang and Davis, 1995). There was one instance of over recruitment due to word-of-mouth between neighbors (Focus Group 5); however, all participants who met the requirements were invited to stay. The total number of male and female participants in each FGD are shown in Table 1. Participants were randomly selected using farmer group contact lists we had gathered during our prior survey work in the region by the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, Kakamega Centre, Kenya (KALRO) and the Academic Model Providing Access to HealthCare (AMPATH), Eldoret, Kenya. The respondents were from communities that had prior exposure to AIVs through USAID-funded Horticulture Innovation training programs. The respondents were from households that had a man or woman [age 18–65 years) and owned a small farm or garden (defined as <1 hectare (ha)]. In addition, respondents were selected based on ease of access and proximity to other homes participating in the FGD. Horticultural farmers or commercial farmers cultivating and managing land more than 3 ha were excluded from the study. For each of the selected respondents, the spouses were also invited to participate in the FGDs.

Data Collection

A semi-structured survey instrument was developed by Rutgers University, the State University of New Jersey (USA) in collaboration with KALRO (Kakamega Centre, Kenya) in English and then translated into the local languages. A copy of the semi-structured survey instrument can be found in the Supplementary Material. The FGDs took an average of 90 minutes and were led by two project team members, one acting as the FGD facilitator and the other as a notetaker. Interviews were not audio recorded due to the limitation of ability to translate and transcribe multiple local languages post survey; however, notes were taken by study team members (MO, CN, NM, and NN).

The semi-structured survey instrument contained open-ended questions in five key areas: staple foods, familiarity of AIVs, importance (or lack of) of consuming AIVs, favorite recipes for cooking AIVs, and barriers and facilitators of consuming AIVs. In addition, FGDs were asked to list their top preferred AIVs and the reasons for their preferences relative to production and consumption.

Data Processing

Immediately following each FGD members of the research team transcribed the notes from the FGD into Microsoft Word, where they were subsequently uploaded into NVivo (Version 12) for analysis. FGD participants provided common AIVs recipes and a list of their most preferred AIVs and reasons for their preferences. The responses for these two questions were aggregated, and the full range of responses were recorded.

Data Analysis

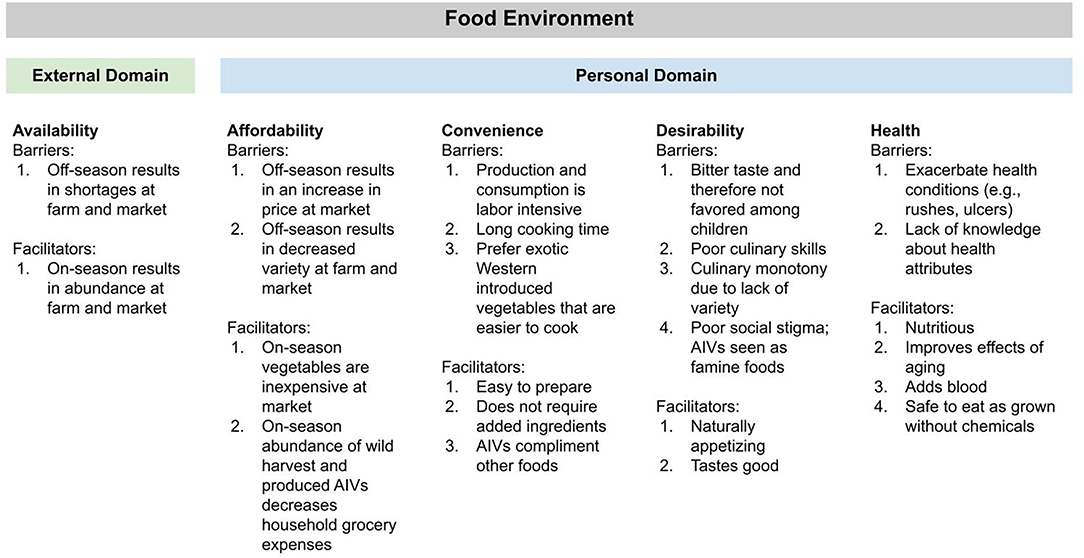

Data were open-coded and organized based on current culinary methods, and barriers and facilitators of preparation and consumption of AIVs within dimensions of the external (e.g., availability, food price) and personal (e.g., affordability, convenience, desirability) food environments (Turner et al., 2017) as well as perceived AIV health attributes. Within each of these dimensions (e.g., availability, affordability, convenience) themes and subthemes were coded. Each of the dimensions ranged in the number of themes and subthemes with the full range presented in Figure 1. If discrepancies were encountered between FGDs, both perspectives were captured and reported in the data. The dimensions for this thematic framework were selected based the external and personal food environment presented in Turner et al. (2017) (e.g., affordability, availability, convenience, desirability) as well as elements of interest to the larger study (e.g., perceived health). Thematic analysis of FGDs was conducted using NVivo (Version 12) by one member of the research team following qualitative thematic exploration (Williams and Moser, 2019).

Figure 1. Key barriers and facilitators to production and consumption of African Indigenous Vegetables in the external and personal food environment in Western Kenya.

Results

The results are organized into current culinary practices and perceived barriers and facilitators of the preparation and consumption of AIVs within the external and personal food environment (Figure 1).

Current Culinary Practices

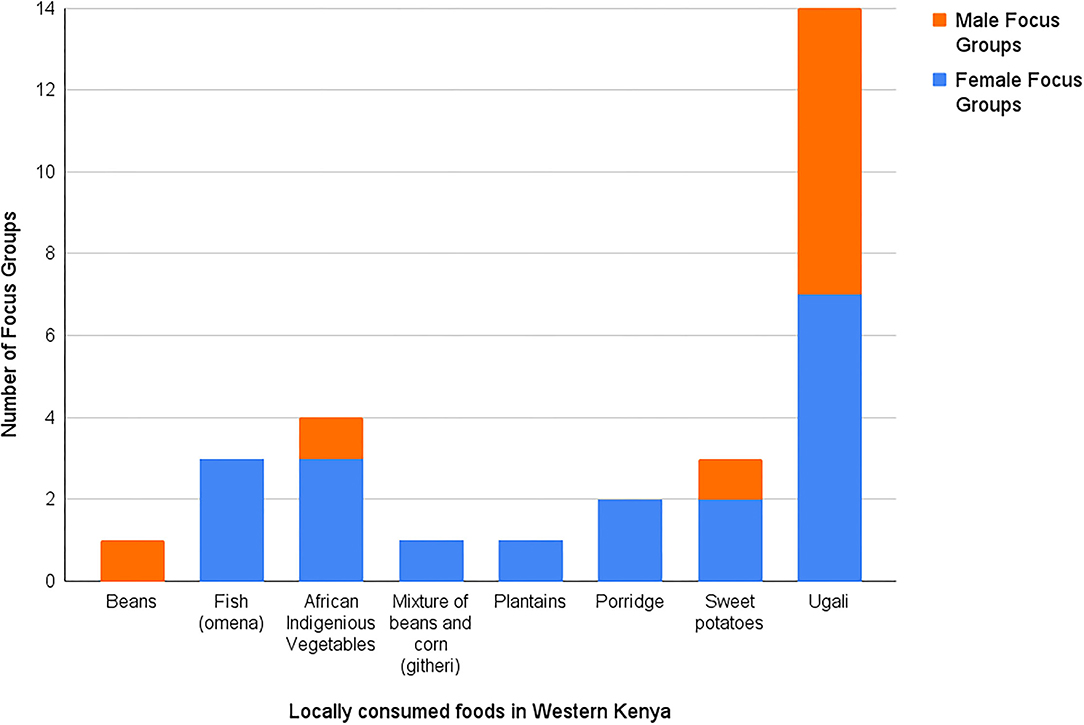

Common Foods Consumed by Households

The FGDs identified common foods consumed within their household. All 14 focus groups reported ugali, a mixture of cassava, sorghum, millet, and/or maize, as the most common food consumed. The full range of reported commonly consumed foods is presented in Figure 2. In addition to ugali, respondents noted AIVs (3 female and 1 male focus group) and sweet potatoes (2 female and 1 male focus group) as commonly consumed foods. One FGD noted the most common consumed AIVs were “spider plant, kales, slender leaf, nightshade, cowpea leaves, and African kale” (Focus Group 1, female).

Figure 2. Most commonly consumed foods as reported by male and female focus groups in Western Kenya.

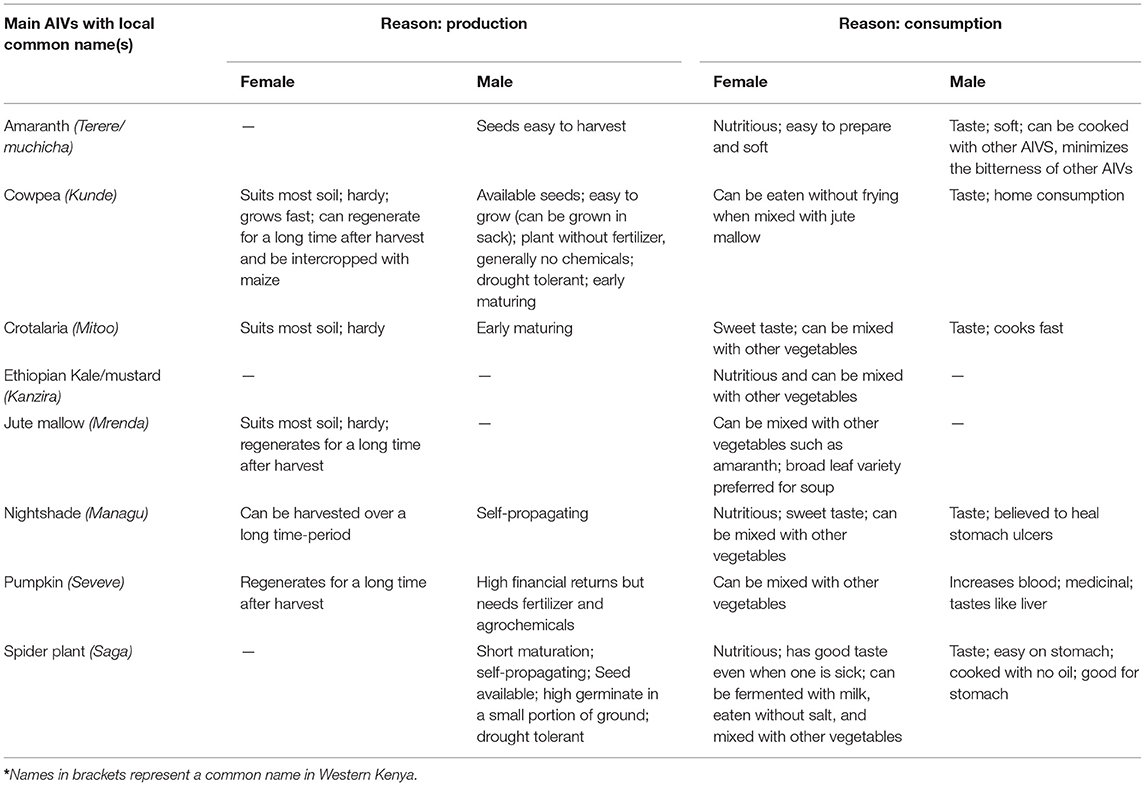

The top 8 preferred AIVs listed in alphabetical order and the full range of reasons participants prioritized these AIVs are listed in Table 2. When participants were asked why they preferred the various AIVs, female focus groups commonly elaborated on reasons relative to consumption noting nutrition, taste, ability to cook without additional ingredients (e.g., salt, oil), and ability to mix with other vegetables. Meanwhile, male focus groups more commonly elaborated on reasons relative to production noting sowing method (e.g., volunteer, self-propagating), inputs (e.g., fertilizer), and financial return.

Table 2. Top eight African Indigenous Vegetables reported by female and male focus groups and reasons for preferences relative to production and consumption.

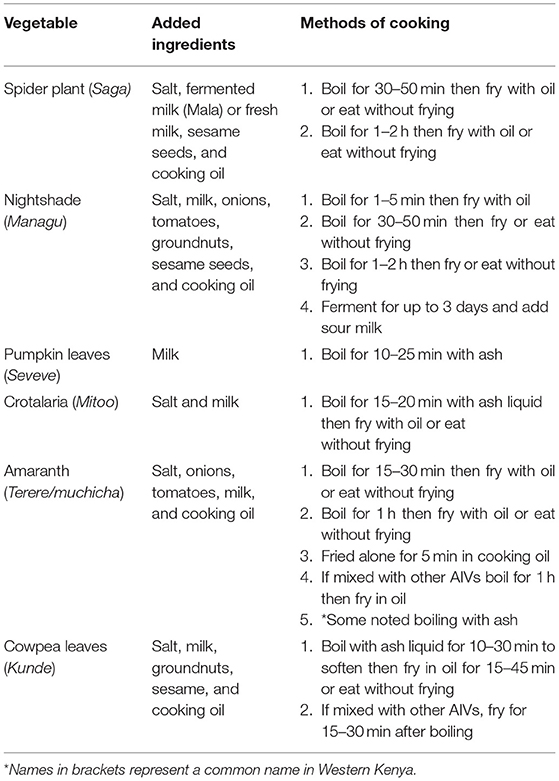

Common AIVs Recipes and Frequency of Consumption

The full range of reported cooking methods and added ingredients for AIVs are listed in Table 3. It was noted that all of the AIVs could be cooked alone. Yet, in common practice, the AIVs were usually mixed and ingredients such as salt, milk, and groundnuts (peanuts) were added to the dishes. In addition, it was noted that ash a natural form of lye, commonly known as munyu musherekha in the local dialect and derived from the burning of different plants such as dried bean pods, was often added to the cooking water to soften the vegetables. However, Focus Group 12 (male) noted that, “It becomes difficult to eat the AIVs if too much ash water is used during cooking.” Most farmers reported that AIVs were prepared using the traditional method of boiling and/or pan-cooking with oil, tomato, and onion. However, there were large discrepancies between reported cooking times, where some reported more “modern” cooking times of blanching and/or pan-cooking for 1–5 min while others reported more traditional times that range up 2 h. Some FGDs noted that the cooking time is extended when mixing different AIVs together to allow the flavors to blend.

Respondents reported that they did not set goals for consumption frequencies. It was noted that vegetables are consumed at random with no clear timetable as consumption is often dependent on seasonal availability and affordability at the market and farm. This was summarized Focus Group 8 (male), “No goals are set, we eat AIVs depending on their availability and affordability. AIVs are cheaper during the rainy season because plenty can be found in the marked or even within the community.” However, it was noted that mothers use “intuition to ensure that the family rotates and eats different types of vegetable through the week” (Focus Group 13, female).

External Food Environment

Availability

Availability of AIVs can present barriers and facilitators to preparation and consumption. Respondents noted that the two main barriers to availability were seasonality and allocation of land on their farm. Focus Group 6 (male) noted that there is a “shortage of AIVs during drought[s].” Furthermore, seasonality can inhibit the ability to acquire the necessary ingredients to prepare complete and desired meals for household consumption as summarized by Focus Group 11 (female), “Not all vegetables are available in each season this makes it difficult to get the required varieties for mixing.” In addition to limited availability during the dry seasons, respondents noted that a lack of availability may be attributed to low production of AIVs on the farm as summarized by Focus Group 1 (female), “Most of the land has maize and little land is left for AIVs.” On the contrary, FGDs reported that during the growing season market availability was a facilitator for consuming AIVs. Focus Group 11 (female) noted that, “They are found easily in the market compared to other foods.”

Food Price

Depending on seasonality, AIV food price presented barriers and facilitators for AIV preparation and consumption. In addition to availability, respondents noted that seasonality presented a barrier to the cost of AIVs during the dry seasons. Focus Group 8 (male) noted that “when not in season especially during the dry season, most AIVs are sold expensively.” Meanwhile, during peak production season the low cost of AIVs at the market facilitated purchasing and household consumption.

Personal Food Environment

Affordability

Relative to affordability, or the ability to acquire AIVs, barrier and facilitators were reported. Off-season, affordability influenced the variety of AIVs that are purchased for household consumption as summarized by Focus Group 13 (female), “Financial ability is sometimes a limitation to changing the type of vegetables to be eaten.” Meanwhile, AIVs were affordable to purchase and plant in-season, particularly when AIVs are self-produced or wild-harvested. FGDs noted that AIVs are “cheap to get and plant,” particularly if they are wild harvested (Focus Group 7, female). Due to their low production cost, this was also a “more economical option than buying them from the market” (Focus group 12, male). In addition, to providing readily available inexpensive nutritious leafy greens, self-production of AIVs also allowed for household finances as summarized: “vegetables from the wild, volunteers or vegetable gardens help reduce amount of money spent on food” (Focus Group 4, male).

Convenience

Relative to the convenience of preparing AIVs, FGDs reported both barriers and facilitators. During the FGDs, participants observed several barriers regarding the convenience of preparing AIVs. It was reported that preparing AIVs, from harvest to table is labor-intensive. Focus Group 14 (male) summarized this by saying, “Some females pick less vegetables from the farm to avoid the long preparation time required before cooking, such as plucking the leaves and washing several times to remove soil.” It was further noted that “the local vegetables take long to cook which discourages some people because they don't have much time to wait” (Focus Group 13, female). Furthermore, respondents noted that when they have the economic resources, they prefer to purchase exotic vegetables or “expensive” food. Focus Group 12 (male), summarized this by saying, “Many people prefer global vegetables because they are easy to prepare.”

There are several aspects with respect to convenience of preparation that facilitate the consumption of AIVs. Focus Group 7 (female) noted that AIVs “can be cooked very easily with simple ingredients,” suggesting that they are easy to prepare with little to no added ingredients such as oil or meat. Furthermore, AIVs can easily compliment other foods to create a complete meal. Focus Group 11 (female) summarized this by saying, “Vegetables is a ready food that can consumed with other food like meat to form a complete meal for the family.”

Desirability

There were differences in responses relative to the desirability of AIVs, where both barriers and facilitators were noted. FGDs provided a range of barriers related to the desirability of AIVs. Respondents indicated that some AIVs had a bitter taste, which reduced consumption particularly among children: “Some vegetables are bitter which makes some youths and children dislike them” (Focus Group 13, female). Furthermore, it was noted that a lack of variety results in boring and monotonous meals. This challenge was summarized by a participant from Focus Group 13 (female) who noted that, “Cooking one type of vegetable several times make the family member loose interest hence consumption reduces.” Poor culinary skills were noted as another major challenge: “Poor cooking skills make most of family members refuse to eat vegetables” (Focus Group 11, female). Furthermore, AIVs carry a negative perception, which affect household consumption given that some “believe that vegetable for the poor people” (Focus Group 10, male).

Some FGDs reported facilitators relative to the desirability of AIVs. Some respondents noted that AIVs are “naturally appetizing” (Focus Group 14, male) and “have a good taste” (Focus Group 6, male). Additionally, respondents noted that eating AIVs may increase appetite for eating ugali. Furthermore, “milk can be added to make the taste even better” (Focus Group 6, male).

Health

Several health aspects that present barriers and facilitators to the consumption of AIVs were reported. Many respondents noted that consumption of AIVs can cause or exacerbate health conditions, particularly in the gut and digestion system (e.g., stomach upset, ulcers, and diarrhea). Focus Group 9 (female) summarized this by reporting that, “Some people have ulcers hence preventing them from using some AIVs.” In addition, it was noted that some AIVs can cause allergic reactions for some people when they eat AIVs as “they get [rashes]” (Focus Group 13, female). Some respondents noted ‘oldwives tales' regarding a few of the AIVs, notably that “crotalaria destroys the liver” (Focus Group 10, male). Furthermore, it was noted that a “lack of knowledge on the importance of AIVs” may contribute to low consumption (Focus Group 10, male).

While some FGDs noted barriers, positive health aspects that facilitate the consumption of AIVs were also reported. FGDs noted a wide variety of health components of AIVs that facilitate their consumption. Contrary to the above where respondents noted that AIVs can contribute to rashes through allergic reactions, Focus Group 13 (female), noted that AIVs, “Cure diseases like skin [rashes].” Moreover, respondents noted that AIVs were a “source of health food” (Focus Group 7, female) and noted that they were nutritious, rich in vitamins, and considered to have medicinal properties. Furthermore, it was reported that consuming AIVs may “improve on health hence help in retarding aging effect” (Focus Group 9, female). Some respondents were able to identify ways that AIVs impact one's general wellness, such as “add blood and strength in the body,” (Focus Group 9, female) promoting a strong immune system, and preventing/reducing diseases such as cancer and infections. Respondents also noted other general wellness attributes such as AIVs are low in calories, increased thirst, and were safe to eat because they are planted without chemicals. Specifically, respondents were able to make note of ways that AIVs directly benefit the body such as reducing blood pressure, improving digestion, eyesight, intelligence, and memory, and settling the stomach. In addition, some respondents noted that the consumption of AIVs is important for pregnant and lactating mothers.

Discussion

This paper sought to identify the barriers and facilitators to the preparation and consumption of AIVs from a food environment perspective. These opportunities are particularly highlighted in instances when there were seasonal differences in the reported barriers and facilitators. Low availability and low affordability of AIVs are experienced during the dry season while the AIVs are readily available and affordable when self-grown or during the rainy season. The seasonal influence of production and consumption presented in this study has also been reported in previous research (Kimiywe et al., 2007; Ambrose-Oji, 2009). For instance, daily consumption of AIVs has been reported during peak seasons and the frequency of consumption has been reported to be as low as once a week during off-seasons (Weinberger and Msuya, 2004). These seasonal fluctuations imply that the barriers to preparation and consumption of AIVs are situational and could be modified through context-specific interventions that mitigate the seasonal effects of AIV production. A package of interventions designed to promote healthy diets through an increase in the preparation and consumption of AIVs should include improved access to affordable AIVs, improved cooking methods and recipes, and the promotion of the beneficial heath attributes of AIVs while actively dispelling the perceived negative health consequences of their consumption.

Improved Availability and Affordability of AIVs Through Household Production Training

The reported barriers and facilitators to availability and affordability are tightly linked to seasonality where off-season AIV shortages and high prices were reported while in-season it was reported that AIVs were abundant and inexpensive. This seasonal fluctuation impacts household food choices and causes a decrease in household consumption of AIVs prohibiting families from meeting the recommended consumption goal of 400 g of fresh fruits and vegetables per capita daily (World Health Organization. Nutrition Unit., 2003). To meet this goal, and promote healthy diets, fresh dark, leafy greens must be available and affordable year-round. One way to ensure year-round availability and affordability is through the promotion of year-round home production and the introduction of affordable water collection systems and water management during the dry season. An intervention of this nature is particularly suitable for subsistence farmers (Musotsi et al., 2009), such as those who participated in the study. Participants noted that the core AIVs that they grew were hardy and environmentally adapted, need little to no inputs, and are easily produced (e.g., self-propagate). However, it was reported that households are not growing enough to meet household consumption demands. Promoting the production of AIVs through provision of improved seeds and good agronomic practices could increase household production and subsequently the consumption of a variety of AIVs at the household level with potential sales from surplus (Korth et al., 2014). In addition, households could be trained to preserve AIVs when they are in plenty and subsequently how to prepare preserved AIVs for household consumption. This would allow for year-round access during seasons when AIVs are not readily available in the home garden plot.

Improved Cooking Methods and Recipe Development Through Culinary Training

In addition to access, individual and household demand can impact consumption. Research suggests that culinary interventions can have positive outcomes by altering food attitude and preferences, and increasing nutrition literacy (Lautenschlager and Smith, 2007; Flynn et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2014). The FGDs noted that common barriers households face when encouraging their families to eat dark leafy greens is monotony and poor taste. In most FGDs, participants reported that they prepare AIVs using the traditional methods of boiling and/or pan-cooking the vegetables with oil, tomato, and onion but often there was a discrepancy between reported cooking times with some as long as two hours. Apart from culinary monotony, the lengthy cooking time can result in a loss of overall nutritional quality of the finished dish (Kamga et al., 2013; Gogo et al., 2017).

To minimize monotony, improve taste, and promote more frequent consumption of AIVs with higher nutrition relative to traditional cooking methods interventions should focus on recipe development and variation in preparation styles (Managa et al., 2020; Odendo et al., 2020). For example, interventions could emphasize decreased cooking time to maintain the nutritional quality and palatability of the finished dish. A study by Habwe et al. (2009) reported that cooking AIVs significantly increased the iron content compared to the raw vegetables, particularly when the dish is served with complimentary vegetables that increases the overall nutrient profile of the finished dish. In addition, Habwe et al. (2009) found that boiling the vegetables with ash, a natural form of lye, a traditional method to soften the vegetables, significantly decreased the available iron content. Moreover, while AIVs are naturally adapted to the local environment, there are still subject to seasonality (Weinberger and Msuya, 2004; Kimiywe et al., 2007; Ambrose-Oji, 2009; Gido et al., 2017). Preserving and drying AIVs could provide year-round access to nutrient dense vegetables (Owade et al., 2020). However, it is essential that households are provided nutrition and culinary education that ensure proper handling of AIVs during the drying process to ensure maximum retention of taste and flavor first as well as nutrient content. Furthermore, proper methods for rehydrating the vegetables and recipes that take into consideration the sensory attributes of the finished dish can further promote the consumption of the preserved vegetables. Context specific culinary interventions and nutrition education could promote incorporating and rotating complimentary vegetables (e.g., tomatoes, onion, carrots) and flavors (e.g., garlic and ginger) while minimizing the use of lye for preparation to maximize iron delivery. Furthermore, culinary interventions could provide education on proper postharvest preservation methods for dehydration, rehydration, and appropriate recipes to promote year-round consumption of AIVs.

Promotion of the Beneficial Health Attributes of AIVs Through Nutrition Education

In addition to providing high concentrations of essential nutrients such as iron, protein, calcium, and magnesium (Abukutsa-Onyango et al., 2010; Byrnes et al., 2017), AIVs also contain secondary plant metabolites such as carotenoids, glucosinolates, and phenolic compounds that contribute to human health (Fadl Almoulah et al., 2017; Neugart et al., 2017). Each AIV contains a unique profile of vitamins, minerals, and plant metabolites; therefore, the consumption of a variety of these AIVs may contribute to different health benefits such as antioxidant activity and increased pro-vitamin A consumption (Fadl Almoulah et al., 2017; Neugart et al., 2017). Many of the health benefits attributed to AIVs are due to their bioactive compounds, some of which may impart a bitter, astringent, acrid flavor and impart a negative perception of AIVs (Drewnowski and Gomez-Carneros, 2000). Some FGDs responses indicated their belief that the consumption of AIVs may cause or exacerbate pre-existing health conditions. While more research is required to understand the link between consuming AIVs and anti-nutritive factors, some of these assumptions may be due to the AIVs' bitter flavor. While some of these AIVs are indeed known to contain anti-nutritive factors including glycoalkaloids, phytic acid, and oxalic acid, the concentration and type of anti-nutritive factors is complex. Genetics and the environment contribute to the levels and/or content of such compounds (Rouphael et al., 2012). In general, AIVs are healthy and highly nutritious, and it is important that nutritious intervention focus on the health benefits of AIVs and actively dispel misinformation. However, any concerns relating to the possible content of anti-nutritive compounds should be thoroughly examined as described using nightshade as an example (Yuan et al., 2017).

While a package of interventions may increase household production and consumption of nutritious AIVs, policy level change is needed for significant improvements to encourage production and availability. Improved production and subsequent consumption hinge on stability in the food environment (Jarosz, 2014; Downs et al., 2020; FAO, 2021). For example, climate variability, including shocks, or poor seed stock can cause crop failure or low yields further driving demand and price (Ochieng et al., 2019). Furthermore, political unrest or regional crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may limit an individual's ability to access the markets (FAO, 2021; O'Hara and Toussaint, 2021). Hence, policy-level change that fosters an enabling environment for the production and consumption of AIVs needs to be enacted to fully address this issue. Furthermore, such policies could capitalize on the natural beneficial qualities of producing and consuming AIVs that lend themselves to a sustainable diet and food system. For example, AIVs have adapted to the local environmental conditions such as limited water supply and high temperatures often experienced in SSA (Chivenge et al., 2015; Stöber et al., 2017; Hunter et al., 2019). These highly tolerant vegetables can contribute diverse micro- and macronutrients to diets year-round and particularly during times when other, more environmentally sensitive, exotic vegetables are a challenge to produce as the costs of production is high. Moreover, when these vegetables are produced at the household level, they provide an opportunity for increased household availability of AIVs that do not require the built food environment. This could provide resilience to household diets and protect households against shocks to the food system such as those due to restricted movements of people and trade during the COVID-19 pandemic. In order for indigenous foods to thrive, policies need to champion their production and consumption. For example, Brazil has several national initiatives such as but not limited to, National School Meals Programme and Food Acquisition Programme, which mandated that school meals are partially soured from family farmers and paid an incentive for organic or agroecological produce from smallholder farmers (Hunter et al., 2019). Policies such as this can contribute to the production and consumption of traditional vegetables and may help address malnutrition concerns such as undernutrition.

Limitations

Our study was limited by our inability to audio record and transcribe verbatim the focus group discussions. While this limitation may have resulted in a loss of nuances between participants, the overall data collected fills a research gap in the current literature relative to current cooking methods and noted barriers and facilitators to AIV consumption and preparation in Western Kenya. Additionally, this study solely used qualitative data to address our research questions. A mixed-methods approach could have provided additional insight into our findings. However, we believe this this exploratory study offers a contribution to the field that is significant and critical for the development of context-specific interventions for these communities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

An increase in the consumption of AIVs could improve micronutrient deficiencies within at-risk populations in Kenya. The AIVs are prepared using the traditional method of boiling and then pan cooking the vegetables with oil, tomato, and onion but there were large discrepancies between cooking times. There were also seasonal differences in the barriers and facilitators for the preparation and consumption of AIVs. Poor availability and low affordability of AIVs during the dry season, poor taste and monotonous diets, and perceived negative health outcomes were the key barriers. While ease of availability and affordability particularly when produced at home, ease of preparation, and beneficial health attributes were reported as facilitators. Interventions within the personal and external food environments should focus on increasing year-round availability in the home-garden through drought mitigation techniques such as water collection and storage as needed, irrigation; improved affordability through on-farm production and wild harvesting; and improved desirability, palatability, and knowledge of health benefits through culinary and nutrition education. Furthermore, this promotion may improve social outcomes by fostering a sense of biocultural pride and belonging in turn reshaping the negative social stigma associated with these “wild indigenous/traditional” nutritionally dense vegetables. There is need for policies that simultaneously promote increased farmers' access to key inputs (e.g., improved seed, fertilizers, water, and validated agronomic practices) for AIV production and support behavior change communications for increased consumption of AIVs. Future research can build on our findings by developing and implementing context-specific interventions and conducting a rigorous evaluation of its impact.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Rutgers University IRB; Academic Model for Providing Access to Healthcare (Eldoret, Kenya). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

EM designed the survey instrument in concert with DH and JS, analyzed the qualitative data, and wrote the manuscript draft. MO and CN piloted and modified the survey instrument and participated in all data collection. NM and NN participated in the field survey including data collection. SD provided technical guidance and oversight on the data analysis. DH and JS oversaw the development of the survey instrument and data collection. All authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Horticulture Innovation Lab with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID EPA-A-00-09-00004), as part of the U.S. Government's global hunger and food security initiative, Feed the Future, for project titled Improving nutrition with African indigenous vegetables in eastern Africa that was awarded to Rutgers University. Additional funding was provided by the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station HATCH project 12170 and the New Jersey IFNH Center for Agricultural Food Ecosystems at Rutgers University.

Author Disclaimer

The contents are the responsibility of the Horticulture Innovation Lab and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Xenia Morin for her contributions to the study and also like to thank Angela Yator and Eunice Onyango for their contributions to the data collection. Furthermore, we thank the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) and Academic Model Providing Access to HealthCare (AMPATH) for hosting the project in Kenya, and the farmers who sacrificed their time to discuss with us.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2022.801527/full#supplementary-material

References

Abukutsa-Onyango, M. (2010). African Indigenous Vegetables in Kenya: Strategic Repositioning in the Horticultural Sector. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

Abukutsa-Onyango, M., Kavagi, P., Amoke, P., and Habwe, F. (2010). Iron and protein content of priority African Indigenous Vegetables in the Lake Victoria basin. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 4, 67–69.

Ajayi, I. O., Adebamowo, C., Adami, H.-O., Dalal, S., Diamond, M. B., Bajunirwe, F., et al. (2016). Urban-rural and geographic differences in overweight and obesity in four sub-Saharan African adult populations: a multi-country cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 16, 1126. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3789-z

Ambrose-Oji, B. (2009). “Urban food systems and African Indigenous Vegetables: defining the spaces and places for African Indigenous Vegetables in urban and peri-urban agriculture,” in African Indigenous Vegetables in Urban Agriculture, eds C. Shackleton, C. A. Drescher, and M. Pasquini (London: Earthscan, Dunstan House), 1–34.

Busetto, L., Wick, W., and Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2, 14. doi: 10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Byrnes, D. R., Dinssa, F. F., Weller, S. C., and Simon, J. E. (2017). Elemental micronutrient content and horticultural performance of various vegetable amaranth genotypes. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 142, 265–271. doi: 10.21273/JASHS04064-17

Chivenge, P., Tafadzwanashe M Albert, M. T, and Paramu, M. (2015). The potential role of neglected and underutilised crop species as future crops under water scarce conditions in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 5685–5711. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120605685

Cooper, S., and Endacott, R. (2007). Generic qualitative research: a design for qualitative research in emergency care? Emerg. Med. J. 24, 816–819. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.050641

Downs, S. M., Ahmed, S., Fanzo, J., and Herforth, A. (2020). Food environment typology: advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods 9, 532. doi: 10.3390/foods9040532

Drewnowski, A., and Gomez-Carneros, C. (2000). Bitter taste, phytonutrients, and the consumer: a review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72, 1424–1435. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1424

Fadl Almoulah, N., Voynikov, Y., Gevrenova, R., Schohn, H., Tzanova, T., Yagi, S., et al. (2017). Antibacterial, antiproliferative and antioxidant activity of leaf extracts of selected Solanaceae species. South Afr. J. Bot. 112, 368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.06.016

Flynn, M. M., Reinert, S., and Schiff, A. R. (2013). A six-week cooking program of plant-based recipes improves food security, body weight, and food purchases for food pantry clients. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 8, 73–84. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2012.758066

Fongar, A., Gödecke, T., and Qaim, M. (2019). Various forms of double burden of malnutrition problems exist in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health 19, 1543. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7882-y

Gido, E. O., Ayuya, O. I., Owuor, G., and Bokelmann, W. (2017). Consumption intensity of leafy African Indigenous Vegetables: towards enhancing nutritional security in rural and urban dwellers in Kenya. Agric. Food Econ. 5, 14. doi: 10.1186/s40100-017-0082-0

Gillespie, S., and Bold, M. van den (2017). Agriculture, food systems, and nutrition: meeting the challenge. Glob. Challenges. 1, 1600002. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201600002

Gogo, E. O., Opiyo, A. M., Ulrichs, C., and Huyskens-Keil, S. (2017). Nutritional and economic postharvest loss analysis of African Indigenous Leafy Vegetables along the supply chain in Kenya. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 130, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.04.007

Habwe, F. O., Walingo, M. K., Abukutsa-Onyango, M. O., and Oluoch, M. O. (2009). Iron content of the formulated East African Indigenous Vegetable recipes. Afr. J. Food Sci. 3, 393–397.

Hartmann, C., Dohle, S., and Siegrist, M. (2013). Importance of cooking skills for balanced food choices. Appetite 65, 125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.016

Hoffman, D. J., Merchant, E., Byrnes, D. R., and Simon, J. E. (2018). Preventing micronutrient deficiencies using African Indigenous Vegetables in Kenya and Zambia. Sight Life 32, 177–181. doi: 10.52439/VRKK4359

Hunter, D., Borelli, T., Beltrame, D. M. O., Oliveira, C. N. S., Coradin, L., Wasike, V. W., et al. (2019). The potential of neglected and underutilized species for improving diets and nutrition. Planta 250, 709–729. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03169-4

Jarosz, L. (2014). Comparing food security and food sovereignty discourses. Dial. Hum. Geogr. 4, 168–181. doi: 10.1177/2043820614537161

Jones, S. A., Walter, J., Soliah, L., and Phifer, J. T. (2014). Perceived motivators to home food preparation: focus group findings. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietet. 114, 1552–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.05.003

Kamga, R. T., Kouamé, C., Atangana, A. R., Chagomoka, T., and Ndango, R. (2013). Nutritional evaluation of five African Indigenous Vegetables. J. Hortic. Res. 21, 99–106. doi: 10.2478/johr-2013-0014

Kimani-Murage, E. W., Muthuri, S. K., Oti, S. O., Mutua, M. K., van de Vijver, S., and Kyobutungi, C. (2015). Evidence of a double burden of malnutrition in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS ONE 10, e0129943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129943

Kimiywe, J., Waudo, J., Mbithe, D., and Maundu, P. (2007). Utilization and medicinal value of indigenous leafy vegetables consumed in urban and peri-urban Nairobi. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 7, 15. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.15.IPGRI2-4

Korth, M., Stewart, R., Langer, L., Madinga, N., Rebelo Da Silva, N., Zaranyika, H., et al. (2014). What are the impacts of urban agriculture programs on food security in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Environ. Evid. 3, 21. doi: 10.1186/2047-2382-3-21

Lautenschlager, L., and Smith, C. (2007). Beliefs, knowledge, and values held by inner-city youth about gardening, nutrition, and cooking. Agric. Hum. Values 24, 245–258. doi: 10.1007/s10460-006-9051-z

Maestre, M., Poole, N., and Henson, S. (2017). Assessing food value chain pathways, linkages and impacts for better nutrition of vulnerable groups. Food Policy 68, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.12.007

Managa, M. G., Shai, J, Thi Phan A. D Sultanbawa, Y., and Sivakumar, D. (2020). Impact of household cooking techniques on African Nightshade and Chinese Cabbage on phenolic compounds, antinutrients, in vitro antioxidant, and β-glucosidase activity. Front. Nutr. 7, 292. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.580550

Maundu, P., Achigan-Dako, E., and Morimoto, Y. (2009). “Biodiversity of African vegetables,” in African Indigenous Vegetables in Urban Agriculture, eds C. Shackleton, C, A. Drescher, and M. Pasquini (London: Earthscan, Dunstan House), 65–101.

Mepba, H. D., Eboh, L., and Banigo, D. E. B. (2007). Effects of processing treatments on the nutritive composition and consumer acceptance of some Nigerian edible leafy vegetables. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 7, 1–18.

Muhanji, G., Roothaert, R. L., Webo, C., and Stanley, M. (2011). African Indigenous Vegetable enterprises and market access for small-scale farmers in East Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 9, 194–202. doi: 10.3763/ijas.2010.0561

Musotsi, A., Sigot, A., and Onyango, M. (2009). The role of home gardening in household food security in Butere division of western Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 8, 375–390. doi: 10.4314/ajfand.v8i4.19199

Neugart, S., Baldermann, S., Ngwene, B., Wesonga, J., and Schreiner, M. (2017). Indigenous leafy vegetables of Eastern Africa - A source of extraordinary secondary plant metabolites. Food Res. Int. 100, 411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.02.014

Ochieng, J., Afari-Sefa, V., Karanja, D., Kessy, R., Rajendran, S., and Samali, S. (2018). How promoting consumption of traditional African vegetables affects household nutrition security in Tanzania. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 33, 105–115. doi: 10.1017/S1742170516000508

Ochieng, J., Govindasamy, R., Dinssa, F. F., Afari-Sefa, V., and Simon, J. E. (2019). Retailing traditional African vegetables in Zambia. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 32, 175–185. doi: 10.5958/0974-0279.2019.00030.2

Odendo, M., Ndinya-Omboko, C., Merchant, E. V., Nyabinda, N., Maiyo, N., Hoffman, D., et al. (2020). Do preferences for attributes of African Indigenous Vegetables recipes vary between male and female? A case from Western Kenya. J. Med. Act. Plants 9, 126–132. doi: 10.7275/RRRT-D011

O'Hara, S., and Toussaint, E. C. (2021). Food access in crisis: food security and COVID-19. Ecol. Econ. 180, 106859. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106859

Owade, J. O., Abong', G., Okoth, M., and Mwang'ombe, A. W. (2020). A review of the contribution of cowpea leaves to food and nutrition security in East Africa. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 36–47. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1337

Popkin, B. M., Adair, L. S., and Ng, S. W. (2012). Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 70, 3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x

Raschke-Cheema, V., and Cheema, B. (2008). Colonisation, the New World Order, and the eradication of traditional food habits in East Africa: historical perspective on the nutrition transition. Public Health Nutr. 11, 662–674. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001140

Recha, C. W. (2018). Local and Regional Variations in Conditions for Agriculture and Food Security in Kenya. Agriculture for Food Security 2030.

Rouphael, Y., Cardarelli, M., Bassal, A., Leonardi, C., Giuffrida, F., and Colla, G. (2012). Vegetable quality as affected by genetic, agronomic and environmental factors. J. Food Agric. Environ. 10, 680–688.

Rousham, E. K., Pradeilles, R., Akparibo, R., Aryeetey, R., Bash, K., Booth, A., et al. (2020). Dietary behaviours in the context of nutrition transition: a systematic review and meta-analyses in two African countries. Public Health Nutr. 23, 1948–1964. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019004014

Simon, J., Acquaye, D., Govindasamy, R., Asante-Dartey, J., Juliani, R., Diouf, B., et al. (2021). Building community resiliency through horticultural innovation. Scientia 134, 13–21. doi: 10.33548/SCIENTIA601

Simon, J. E., Weller, S., Hoffman, D., Govindasamy, R., Morin, X., Merchant, E. V., et al. (2020). Improving income and nutrition of smallholder farmers in Eastern Africa using a market-first science-driven approach to enhance value chain production of African Indigenous Vegetables. J. Med. Active Plants 9, 289–309. doi: 10.7275/SJ66-1P84

Stöber, S., Chepkoech, W., Neubert, S., Kurgat, B., Bett, H., and Lotze-Campen, H. (2017). “Adaptation pathways for African Indigenous Vegetables' value chains,” in Climate Change Adaptation in Africa: Fostering Resilience and Capacity to Adapt, eds W. Leal Filho, S. Belay, J. Kalangu, W. Menas, P. Munishi, and K. Musiyiwa (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 413–433. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-49520-0_25

Tang, K. C., and Davis, A. (1995). Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Family Pract. 12, 474–475. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.474

Towns, A. M., and Shackleton, C. (2018). Traditional, indigenous, or leafy? A definition, typology, and way forward for African vegetables. Econ. Bot. 72, 461–477. doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09448-1

Turner, C., Kadiyala, S., Aggarwal, A., Coates, J., Drewnowski, A., Hawkes, C., et al. (2017). Concepts and Methods for Food Environment Research in Low and Middle Income Countries. Agriculture, Nutrition and Health Academy Food Environments Working Group (ANH-FEWG). Innovative Methods and Metrics for Agriculture and Nutrition Actions (IMMANA) programme. London.

Weinberger, K., and Msuya, J. (2004). Indigenous Vegetables in Tanzania-Significance and Prospects. Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, Shanhua.

Welfle, D. A., Chingaira, S., and Kassenov, A. (2020). Decarbonising Kenya's domestic and industry sectors through bioenergy: an assessment of biomass resource potential and GHG performances. Biomass Bioenergy 142, 105757. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105757

Weller, S. C., Van Wyk, E., and Simon, J. E. (2015). Sustainable production for more resilient food production systems: case study of African indigenous vegetables in eastern Africa. Acta Hortic. 1102, 289–298. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1102.35

Williams, M., and Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. Int. Manage. Rev. 15, 45–55. doi: 10.1192/pb.38.2.86b

World Health Organization. Nutrition Unit. (2003). Fruit and Vegetable Promotion Initiative: A Meeting Report. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Yang, R. Y., and Tsou, S. C. (2006). Enhancing iron bioavailability of vegetables through proper preparation-principles and applications. J. Int. Cooperat. 1, 107–119.

Keywords: consumption, food choice, healthy diets, Indigenous Vegetables, nutrition education, malnutrition, recipes, sustainability

Citation: Merchant EV, Odendo M, Ndinya C, Nyabinda N, Maiyo N, Downs S, Hoffman DJ and Simon JE (2022) Barriers and Facilitators in Preparation and Consumption of African Indigenous Vegetables: A Qualitative Exploration From Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:801527. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.801527

Received: 25 October 2021; Accepted: 17 February 2022;

Published: 21 March 2022.

Edited by:

Veronica Ginani, University of Brasilia, BrazilReviewed by:

Therese Mwatitha Gondwe, Independent Researcher, Lilongwe, MalawiRebecca Kanter, University of Chile, Chile

Copyright © 2022 Merchant, Odendo, Ndinya, Nyabinda, Maiyo, Downs, Hoffman and Simon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James E. Simon, amltc2ltb25AcnV0Z2Vycy5lZHU=

Emily V. Merchant

Emily V. Merchant Martins Odendo

Martins Odendo Christine Ndinya3

Christine Ndinya3 Shauna Downs

Shauna Downs Daniel J. Hoffman

Daniel J. Hoffman James E. Simon

James E. Simon