- Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Lüneburg, Germany

Grassroots initiatives, such as local food groups have been identified as a crucial element for a transformation toward more sustainable societies. However, relevant questions to better understand the dynamics of local food initiatives remain unanswered, in particular regarding the people involved. Who are the members in local food initiatives, what motivates individuals to get active in such groups and what keeps people engaged over the long term. This theoretical study presents a conceptual framework drawing on social psychology to describe the connection between identity processes at individual and collective levels in grassroots initiatives, such as local food groups. The framework presented is a guide for researchers in analyzing individuals' identities and their role in and across local food groups and other grassroots initiatives by recognizing identity processes of identification, verification and formation. By providing a more nuanced understanding of how individuals and individuals within groups interact in these grassroots initiatives as spaces of effective environmental action, this framework provides an in-depth perspective on the social dimension of local food systems. More specifically, by focusing on identity dynamics the framework makes a connection between the distinctive kinds of sociality and community that grassroots initiatives offer, their relevance for individuals' involvement and the opportunities to enable transformation.

Global Food Systems and Local Opportunities for Sustainability

Modern food systems have received wide attention for contributing to a vast array of global environmental, social, and economic problems (Weber et al., 2020). To transform modern food systems, research has focused on more sustainable alternatives, such as local food systems. In human history, various forms of small, local groups have always existed, such as today's alternative farmers' markets and local trading arrangements. These groups have again become more prominent in the debate on transformation toward sustainability (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Connelly et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2020). Local alternative food groups address the unsustainability of modern food systems by creating economic and ecological alternatives for food production and consumption. Local alternative food groups gather individual actors who are actively involved in various activities attributable to the concept of sustainability. These groups are often characterized as grassroots initiatives, where individuals create alternatives in bottom-up processes (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). Local food groups are part of the grassroots movement, which have taken different parts of life and transform them to become more sustainable. Next to the food sector, transportation, housing, and energy are systems where committed activists come together and create grassroots innovations as alternatives to the conventional systems of provision (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). Here transformation is seen “in terms of individually smaller actions that collectively, over time, shift system states in ways which may be unexpected but which reflect the values and visions of mobilized agents” (Scoones et al., 2020, p. 67).

Considering the potential of grassroots initiatives for transformation, research needs to understand how to encourage innovative behaviors at the grassroots and how to embed that learning into the mainstream. Research indicates that questions of identity, belonging, purpose, and community are key to learning about grassroots initiatives to support processes of transformation (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). Social psychology has proven valuable in the context of sustainable consumption and grassroots initiatives. For instance different models try to predict individual's behavior, most known Ajzen's (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior. Those focus mainly on the influence of internal factors and are aimed at explaining individual's motivation (Ajzen's, 1991; Kallbekken et al., 2010). However, group level and more systemic approaches are also available to social psychology (Ruby et al., 2020). Here the collective processes prove important for research as they are at the heart of many of the phenomena tied to global environmental crises and potential solution approaches (Barth et al., 2021). Previous research has demonstrated the critical role of social capital in establishing and maintaining alternative local groups (Bauermeister, 2015). The social identity approach helps to explain pro-environmental action (Fritsche et al., 2018) and the development of social cohesion in groups can be meaningful to understand individual's reasons for engagement and group processes that facilitate the maintenance of grassroots initiatives (Maschkowski et al., 2014). In this regard, social psychology contributes a lens that holistically considers individual and collective aspects in the discourse of transformation.

Given the opportunities that arise from understanding social psychological processes in grassroots initiatives, a focus on local food groups as spaces for social interaction and community building proves meaningful. Individual actors are seen as vital for local food groups and their commitment is needed to drive a transformation of food systems toward sustainability. However, questions for research in support of local food systems remain, such as why individuals become involved in local food groups and how their activities can be successfully maintained. Thus, the social psychological concept of identity is useful for exploring individual engagement and social interactions in local food groups. Identity is a process of forming and conceptualizing the self-image of an individual, the individual in the group, and the idea of “we” as a group through social interaction (Stets and Biga, 2003; Burke, 2004). Where identity and local food systems are studied, they have been conceptualized as collective identities in food movements (Bauermeister, 2015) or described as individualized political action through alternative consumption practices (Dobernig and Stagl, 2015). This conceptual study aims to develop and offer a more nuanced approach to researching local food groups as example for grassroots initiatives. Theorizing on identity not only helps to unpack important group dynamics, such as identity verification and collective mobilization, it also offers a new perspective on participation in initiatives as a means to satisfy basic human needs, such as experiencing a sense of belonging (Max-Neef et al., 1989). In doing so, research on identity dynamics sheds light on the social sustainability of local food systems by highlighting the spaces for self-actualization and community building they create for individuals.

The following article defines local food groups as grassroots initiatives driving the transformation of modern food systems. It emphasizes the role of individuals' engagement and group dynamics in maintaining grassroots initiatives. Embedded in the example of local food groups, it highlights the value of social psychological identity concepts and dynamics in understanding the sociability of grassroots initiatives and their mobilization. To this end, this work proposes a theoretical framework of identity types and dynamics to explain the interactions that occur in grassroots initiatives, such as local food groups and their possible consequences. In doing so, the research recognizes local food groups as social spaces and discusses the broader application of this framework in grassroots initiatives to achieve descriptive-analytical and transformative knowledge to enable sustainability.

Local Grassroots Initiatives as Drivers of Food Systems Change

As part of the transformation toward sustainability of food systems, local alternatives can be driving forces for change (Weber et al., 2020). Transformation approaches are brought about through grassroots initiatives, defined as networks of activists and organizations developing novel bottom-up solutions for sustainable development (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). Identified drivers for grassroots initiatives are unmet social needs and ideological commitment to alternative ways of living (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). By creating a shared space for alternative solutions, grassroots initiatives can provide an important nexus between individual motivation and collective action. Grassroots innovations driven by commitment to ideologies that run counter the hegemony of the regime and therefore ‘develop practices based on reordered priorities and alternative values' (Seyfang and Smith, 2007, p. 592) are aligned with the aim of local alternative food groups to provide a more local and sustainable alternative for food consumption. Thus, grassroots initiatives have the potential to serve as role models for a transformation toward more sustainable consumption patterns (Grabs et al., 2016).

A wide range of definitions of local food systems exists, reflecting differing goals, values, and challenges (Eriksen, 2013; Granvik et al., 2017). As a point of departure, this paper refers to two characteristics of local food systems. Local is the criterion most practitioners and researchers refer to, even if it means different things to different people and in different contexts (Eriksen, 2013). A common reference point is provided by a definition deriving from British farmers' markets: local food is food produced, processed, traded, and sold within a defined geographic radius, often 30 miles (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, 2003; Granvik et al., 2017). Moreover, local comprises more complex notions than distance, referring to relational proximity such as connections of a community and its food and farming traditions (Moreno and Malone, 2021). The second criterion alternative originally referred to food sold through supply networks other than supermarket outlets. However, as alternative foods are now also sold and distributed through supermarkets (Maye and Kirwan, 2010), “alternative” in this context refers to non-conventional forms of food production, processing, and supply. Local food systems typically comprise small-scale alternatives and collaborations in different organizational forms or activities (see Table 1) embedded in local landscapes (Fonte, 2008; Brunori et al., 2012; Hinrichs, 2014; Poças Ribeiro et al., 2021).

Research reveals local alternatives as a transformative pathway toward sustainability of modern food systems (Levkoe, 2011; Duell, 2013; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Weber et al., 2020). Authors emphasize the direct and localized relationships with producers, short supply chains, and higher nutritive quality of such systems (Feenstra, 2002; Duell, 2013; Batat et al., 2016). In this regard, local food systems have received increased attention for addressing many shortcomings of modern food systems. Further, they are considered to offer space for community and environmental integrity with a localized answer to global food system challenges (Kirwan and Maye, 2013; Maye and Duncan, 2017). Thus, local food systems are potent drivers of transformation and are highlighted by Connelly et al. (2011) as a “compelling gateway to realizing community transformation” (Connelly et al., 2011, p. 320). Local food groups can empower consumers and producers to make new value judgments based on their own knowledge and experience (Fonte, 2008; Laforge et al., 2017). Therefore, local food groups can become focal points for political and social activity, as illustrated in a study on solidarity purchasing groups (Brunori et al., 2012). The potential of local food groups to drive change toward sustainability calls for deeper appreciation and examination.

Despite the transformative potential of alternative local food groups, there remain a number of reservations. Activists and scholars have equated “local” with “sustainability,” falling into the “local trap” where the category local itself becomes the solution without a critical reflection of the groups' goals, values, and practices (Born and Purcell, 2006; Levkoe, 2011; Kirwan and Maye, 2013). Another problematic tendency of local food groups is to employ the interpretation of “good and sustainable food” by a privileged white, educated, and/or middle to upper-class majority. The unreflective employment of privileged thinking does not consider the experiences of other social groups and therefore reproduces the social and economic inequality inherent in the conventional food system (Guthman, 2008; Connelly et al., 2011; Duell, 2013). A critical reflection of underlying values and structural challenges of local alternative food groups is necessary to pre-empt the danger of reproducing existing unequal structures (DuPuis and Goodman, 2005) and make the work in these local groups a powerful driver for food systems transformation. The framework allows to closer investigating the values and motivation of individuals and the collective in local food groups and can therefore support a critical reflection on what drives these groups.

The Value of Identity Aspects for Local Food Groups as Grassroots Initiatives

Identity concepts have proven valuable in understanding individual consumption and collective mobilization. Consumption, in particular, has a strong symbolic function and can be a means to express and construct individual identity (McCracken, 2002). Research has shown how social identification impacts sustainability related behaviors in different arenas, such as the workplace (Carmeli et al., 2017), consumption patterns (Andorfer and Liebe, 2013), or political citizenship (Dobernig and Stagl, 2015). In addition, the dynamics that develop around the identity of individuals in groups helps to understand how relationships are created. Identity verification processes, for instance, have been used in explaining the engagement of individuals in online communities (Ray et al., 2014). Research on local food and identity has so far focused the marketing perspective exploring different ways of using local identity to create demands (e.g., Moreno and Malone, 2021). The formation of collective identity has been studied in collective mobilization of the peace movement (Gawerc, 2016) and in food movements (Bauermeister, 2015) and can explain the collective action of local food groups, theorizing identity bridges, which Grabs et al. (2016) describe as the important nexus between individual motivation and collective action.

Especially in the discussion around sustainability, social identity theory has recently become more prominent, underlying the meaningfulness of social psychological processes and the collective dimension of individuals' pro-environmental behavior (Barth et al., 2021). For instance the construction of an ethical identity as part of an ethical consumer community and resulting ethical consumption behaviors (Papaoikonomou et al., 2016). Equally, Fritsche and colleagues (2018) elaborate in a “Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action” how social identity processes affect both appraisal of and behavioral responses to large-scale environmental crises. A review on social identity theory and its influence on environmental attitudes and behaviors, as well as group members' likeliness to act more sustainably shows the potential for pro-environmental attitudes, beliefs, and actions (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016). This model is in line with the emerging field of applying social identity to environmental action (Barth et al., 2021) but allows for holistically understanding internal processes on individual level and collective level and focuses social processes in local food groups.

The challenge of initiating and maintaining groups that drive change and their dependence on key actors and active people is documented (Seyfang and Smith, 2007). But people are only studied, if at all, when they hold particularly influential roles, such as change agents or frontrunners (Rotmans and Loorbach, 2010; Nevens et al., 2013). The question remains who is involved in sustainability groups and what are “their backgrounds, roles, motivations, behaviors, resources, or wellbeing” (Mock et al., 2019, p. 2). Rauschmayer et al. (2015) also underline lack of research to understand the values, motivations, and reasons for action of individuals in groups. Transformation research similarly misses the appropriate concepts to analyse and understand the interactions and relationships between the actors who are an essential part of sustainability groups (Wittmayer et al., 2017). This is in line with Mock et al. (2019) who find in their study on the wellbeing of people engaged in sustainability initiatives that positive relations with others is the most mentioned motivating factor for their engagement. Similarly, Maschkowski et al. (2014) highlight group dynamics as a crucial factor, “not only with regard to success … but also in relation to failure of initiatives” (p. 80) and stress the need for further analysis. In this regard, authors suggest social psychological research on interaction and communication between actors to understand what promotes mutual trust and sustains engagement (Seyfang and Haxeltine, 2012; Biddau et al., 2016). Filling the research gap of exploring individuals' commitment to change and understanding the social dimensions of groups would provide meaningful insights for grassroots initiatives.

Research on the contribution of local food systems to a transformation toward sustainability has neglected an understanding of local food groups as identity spaces for social interaction. Although food has long been explored as holding social and cultural meanings with an inherent connection to identity (Fischler, 1988). Food signifies cultural belonging in forms of cuisines and cultural food practices and is often a social activity in itself where people meet around the dinner table. The choice of foods people or groups make can reveal beliefs, passion, background knowledge, assumptions, and personalities (Almerico, 2014). These aspects show the inherent sociocultural characteristics of food and its connection to the identity of individuals and groups. Particularly in local food systems the fostering of direct connections and the building of relationships have been cited as positive side (e.g., Dunne et al., 2011). Nevertheless, in-depth studies of local food groups as spaces of sociability features less prominently, and the ways in which a community develops are not explored in depth (Duell, 2013). Given the central role that individuals play in the formation and maintenance of local food groups, it is surprising that the question of how social and relational functions and dynamics develop in these groups has not received wider scholarly attention. In this study, local food groups are understood as bundles of social interactions and valued as spaces for self-actualization, relationship, and community building.

This theoretical study aims to develop and offer a more nuanced approach to researching grassroots initiatives, such as local food groups. In an integrated model of identity dynamics, the framework helps to unpack relevant group dynamics, such as identity verification and collective mobilization to understand how grassroots initiatives for transformation can be enabled. It highlights food and consumption not just from the individual choice perspective, but includes social and collective levels that move the discussion from solely alternative consumption practices to how individuals in collectives can enable alternative futures and become agents for change. Nevertheless, the conceptual frame can aid to explain why individuals engage in grassroots initiatives. Equally, it shows group dynamics that facilitate trust and commitment and then can enable collective action. Accordingly, zooming in on identity dynamics could offer in-depth knowledge on issues such as the long-term engagement of individuals in grassroots initiatives, as well as which processes in groups lead to collective mobilization. The conceptual framework proves meaningful for a general understanding of the social dimension of grassroots initiatives, but is here embedded in an example of local food initiatives because of the sociocultural properties of food and the relational proximity of local food systems.

Identity Framework In Local Food Groups—Potential To Dive Deeper

An Interdisciplinary Conceptualization of Identity

The theoretical framework presented in this paper combines interdisciplinary concepts concerning identity and identity dynamics in groups to understand sociability and engagement in local food groups. The theoretical lens of social psychology provides concepts of identity and its dynamics. Identities are a set of meanings individuals hold for themselves that define who they are, as a person, as group members, and as a collective (Stets and Biga, 2003; Burke, 2004). Simultaneously, identity serves as a reference that guides individuals' behavior and is, therefore, essentially performative (Burke, 2004). Identities are not stable entities but processes constructed in social interaction. This perspective acknowledges how the individual is embedded in the group as a social structure, which is created and maintained through communication and interaction. Also in grassroots initiatives (Seyfang and Smith, 2007) highlight the inherently social and collective aspects of innovation processes and identify mutual social exchange as essential resources of grassroots initiatives. They likewise stress how the challenge of maintaining a grassroots innovation often depends on its members (Seyfang and Smith, 2007), thereby highlighting the usefulness of identity analysis in spaces like local food groups. Additionally, insights of mobilization theory into collective identities contribute analysis of the wider context of society and culture, which is valuable for exploring the societal dimensions. Taylor and Whittier (1992) define collective identity as “shared definitions of a group that derive from members' common interests and solidarity” (p. 172). In this context, Melucci (1989) emphasizes that collective identity in movements assumes a certain reflexivity for a group to jointly explore the question who they are as a group. As grassroots initiatives need to develop an understanding of themselves as a group that purposefully develops new systems of provision (Seyfang and Smith, 2007), the analysis of their collective identity explains an essential part of their functioning.

Identity dynamics in local food groups are best understood from an interdisciplinary perspective. Three different identity concepts are relevant in local food initiatives and provide a lens to better understand these groups. Personal identity encompasses personal characteristics, values, and opinions and is relevant to all behaviors and interactions (Burke, 2004). Social identity develops from membership of a group or social categories and includes the collective representation of who a person is—or “should be”—in social situations, such as groups (Stets and Burke, 2000). Collective identity adds the understanding of who the group is. Personal, social, and collective identities become relevant in social interactions and within groups (Turner, 2011). As identities have a processual and interactive character, there is no strict demarcation between these different concepts. In summary, identity is a rich concept to analyse different levels of sociability of individuals and groups and proves meaningful when analyzing alternative local food group.

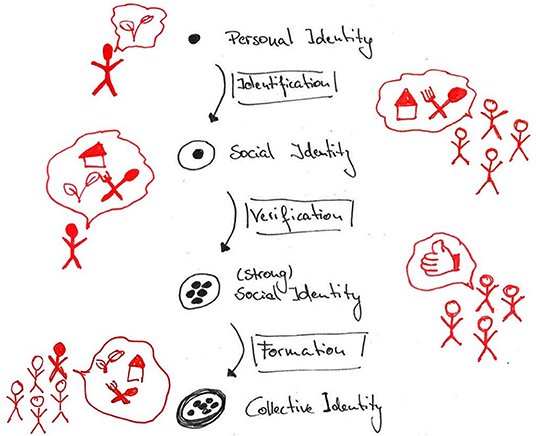

Identity Dynamics in Local Food Groups

Local food groups offer opportunities for individuals to develop social ties, relationships, and community. Eriksen (2013) emphasizes not just geographical proximity in local food systems but also a taxonomy of relational proximity, which she defines as “the direct relations between local actors reconnected through alternative production and distribution practices such as farmers markets, farm shops, cooperatives, box schemes, food networks, etc.” (Eriksen, 2013, p. 51). To understand direct relationships among members of local food groups and the social space they provide, this research framework combines identification, the dynamics of identity verification, and collective identity formation in groups (see Figure 1). Identity dynamics provide insights into internal processes of individuals and groups, as well as how the different identities an individual holds are formed and strengthened. To this end, the identity framework allows zooming in and provides a perspective to explain social processes in local food groups.

Figure 1. Identity dynamics. Synthesized framework based on Turner (1982), Taylor and Whittier (1992), Stets and Burke (2000), Burke (2004), and Turner (2011).

Identification

The initial process of how individuals engage with local food groups is social identification, that is, locating oneself within a system of social categorization (Stets and Burke, 2000). This internalization of categories contributes to the sense of self and guides behavior (Turner, 1982). In this respect, social categories function as cognitive criteria allowing an individual to organize their social world and shape their psychology. Social categories develop by focusing on similarity, common fate, proximity, shared threat, and other factors. In a social comparison process individuals recognize others similar to their own social category and label them as in-group (Stets and Burke, 2000). In this process, specific personal identities are linked to particular social identities, and consequently the personal identity expands to a social identity (Deaux, 1992). Social identification occurs when an individual is ready to use a particular social category and joins a group in a shared social category (Haslam et al., 2009). In the example of local food groups, a social category individuals could potentially identify with is environmentalism. An environmental identity define Gatersleben et al. (2014) as “the extent to which people indicate that environmentalism is a central part of who they are” (p. 377). A strong attraction to a group is found to stem from the individual's identification with the group and leads to greater commitment to the group (Hogg and Hardie, 1992; Ellemers et al., 1997). The effects of social identification are manifold: firstly, social identity provides a foundation for a group to undertake joint action and for further identity and social dynamics. As Turner (1982) puts it, “social identity is the cognitive mechanism that makes group behavior possible” (p. 21). Secondly, identification provides inner consistency as individuals can act according to their own values (Maschkowski et al., 2014). In addition, individuals can feel a sense of belonging to a group and stability by experiencing a feeling of commonality with its members (Wakefield et al., 2017). Research also links social support that accompanies group identification with health-related capital and even the improvement of health in cases of illness (Haslam et al., 2009). When individuals identify themselves according to a local food group, their sustainability values or a place-based identity could be relevant. Identifying these identities as social categories in the group, they perceive to fit in the group and social identification with the local food group occurs. When joining the local food group the former personal identity expands to a social identity.

Verification

Subsequently, the process of identity verification can take place, which builds on and simultaneously contributes to social identification. The notion of people engaging in situations to confirm their self-conceptions (Swann, 1983) is often seen as a driving force for social interaction. Moreover, identity verification is a fundamental need-state of every human being (Burke and Stets, 2009). Turner (2011) describes five basic transactional needs that are always present and activated during social interaction. “The most powerful of these impulses is the drive to verify self or, in today's terminology, identities in the eyes of others” (Turner, 2011, p. 331). An individual's social identity is invoked and verified through a cognitive process of matching the self-relevant meanings occurring in group situations with the internal identity meanings. This process occurs by regarding the responses and views of others in the group (Burke and Stets, 1999). In a local food group, the involved individuals will be verified in their environmental identity via the individuals' activity and interaction with others in the group. When a person's identity is repeatedly verified in interaction, consequences such as positive feelings, increased trust, and commitment to others can occur, and the individual develops a perception that he or she is part of a group (Burke and Stets, 1999). Here groups provide opportunities to build positive emotions, for instance through group processes and joint action, also framed as social capital (Maschkowski et al., 2014). The building of trust is a distinct condition for identity formation processes and contributes to facilitate collective mobilization (Gawerc, 2016). After identifying with the local food group, individuals engage with the others in the group and can in that interaction be verified in their idea of being a Foodie, a sustainable person or a person committed to a specific local place. The verification of these identities in the local food group can be an active driver for engagement. Here local food groups transform from a space for alternative consumption to a social space of consumption. Further, identity verification in a local food group presumably reinforces the respective identity and creates strong social identities around local food. The identity is expected to become more important to the individual, which in return can lead to a heightened engagement for the local food group. The verification dynamics facilitate individuals in the group create positive relationships and trust, as foundation for groups' activity advancing the local food transformation.

Formation

The formation of a collective identity that enables collective action is the next identity dynamic in groups. A three-level framework based on an empirical study of lesbian-feminist mobilization process helps understand the formation of collective identities (Taylor and Whittier, 1992). Firstly, groups create boundaries that serve as a set of markers—similar to social categories—and locate individuals as members of a group. They can vary from geographical or racial characteristics to symbolically constructed differences often found in social institutions. In social movements boundaries serve to set the group apart from the dominant, often oppressive structures in society. Similarly, boundaries create new values and structures that heighten the group's sense of self (Taylor and Whittier, 1992). In a second ongoing process, the group forms a consciousness of itself as a group. In this process, the group members re-evaluate themselves and their experiences in opposition to the dominant structures and define socially constituted criteria that account for the group's structural position (Taylor and Whittier, 1992). The third dimension of identity formation dynamics is negotiation, that is, a way of thinking and acting in private and public settings established by the group. Accordingly, negotiation “encompasses the symbols and everyday actions subordinate groups use to resist and restructure existing systems of domination' (Taylor and Whittier, 1992, p. 111). A boundary marker of local food groups are for instance the organic certification of the food produced and distributed via the group. Furthermore, negotiating the organization of alternative food groups, opposing the dominant structure of how food is produced and the consciousness in the respective group about the dominant structure and their active creation of alternative forms of production and consumption can form the collective identity of a local food group. Identity formation dynamics contributes to our understanding of how collective identity is built and negotiated, how group cohesion is fostered, and how shared meanings and the sense of collective purpose are produced and maintained. Exploring these questions is critical for understanding ongoing participation and commitment in groups (Biddau et al., 2016). In this respect, the active deliberation of the alternative in local food groups builds a foundation for collective action and momentum for transformation.

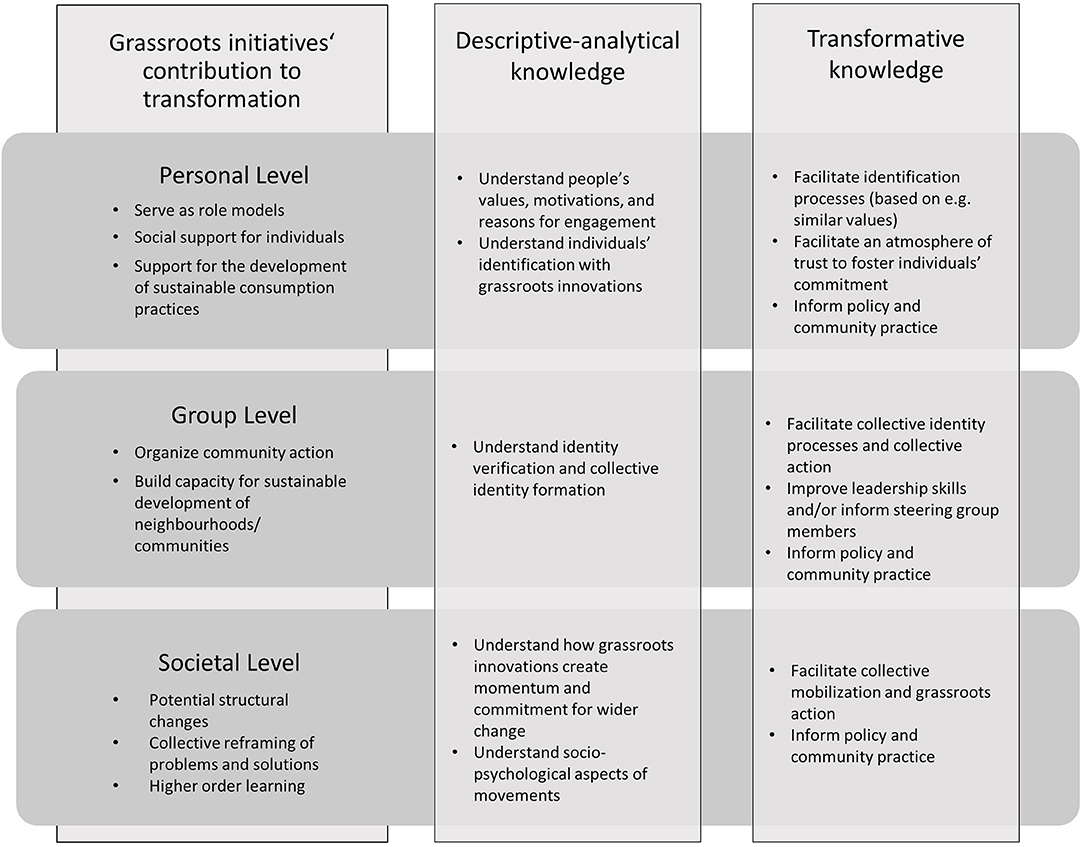

Toward a Research Agenda of Grassroots Initiatives as Social Spaces

The theoretical framework proposed in this paper contributes to an understanding and recognition of grassroots initiatives as social spaces, embedded in the example of local food groups. Providing a social space has been highlighted as a meaningful element for the success of grassroots initiatives (Maschkowski et al., 2014; Grabs et al., 2016). Hence, an application of this framework will be beneficial for understanding grassroots initiatives' essential role for change and contribute to different forms of knowledge in sustainability science. The differentiation of Wiek and Lang (2016) in descriptive-analytical and transformative knowledge helps to distinguish what kind of knowledge the framework can advance. However, instead of relying on science to provide evidence-based solutions to real-world problems, the present framework provides a means to better understand grassroots initiatives as solutions developed by real-world actors (descriptive-analytical knowledge) and the development of this knowledge to possibly facilitate change (transformative knowledge). Grabs et al. (2016) differentiate between personal, group, and societal levels to understand grassroots initiatives contribution to systemic change. Applying the identity framework can offer a new perspective on how grassroots initiatives might advance transformation on all three levels contributing to different types of knowledge (see Figure 2). The expected knowledge generation is made meaningful in an example of a CSA to illustrate the benefits of applying the framework for local food systems.

Figure 2. Knowledge advancement for transformation. Developed from Grabs et al. (2016) and Wiek and Lang (2016).

At a personal level, individuals in grassroots initiatives can serve as role models, and the group can provide social support for individuals and the development of sustainable consumption practices (Grabs et al., 2016). On a descriptive-analytical level, the identity framework promotes an understanding of people's values, motivations, and reasons for engagement in local food groups or other grassroots initiatives (Rauschmayer et al., 2015). Here it can help to understand who the people are active in local food groups in order to not employ privileged thinking reproduce existing inequalities in the food system (Duell, 2013). Simultaneously, the framework provides vocabulary to analyse actors as essential parts of grassroots initiatives (Wittmayer et al., 2017). The framework also sheds light on the identity processes of how groups form a common goal that individuals can identify with and how they build joint expectations (Klandermans, 2002). In this sense, transformative knowledge develops to explore how an atmosphere that facilitates social interaction based on similar values and mutual verification can create a strong social identity for the individual. Here, the trust and commitment of individuals, in for example a local food group, builds from a sense of social identity and may therefore stabilize the group (Turner, 1982). Consequently, transformative knowledge of identity dynamics could enhance the management of grassroots initiatives in promoting group development to sustain individuals' engagement (Seyfang and Smith, 2007; Feola and Nunes, 2014). Overall, the identity framework provides a descriptive-analytical understanding of how individuals identify with grassroots initiatives. The framework has the potential to create transformative knowledge on how to facilitate identification processes, as well as an atmosphere of trust, to form social support for individuals in their commitment to the group and their sustainable consumption practices.

At a group level, grassroots initiatives organize community action and build capacity for the sustainable development of neighborhoods and communities (Grabs et al., 2016). As Seyfang and Haxeltine (2012) call for, the framework creates an understanding of how identity, purpose, belonging, and a sense of community underlie the development of local groups. It highlights how an atmosphere of trust can be created among members. Trust is, for example in cases of collaborative consumption efforts, a key factor for success (Feola and Nunes, 2014; Grabs et al., 2016). The exploration of how identity verification and collective identity formation can create a sense of we-ness offers an in-depth perspective on community and collective action. Understanding identity dynamics can create transformative knowledge to improve leadership skills and/or inform the steering group members of initiatives. This can contribute to the continuous development of a group working to promote commitment and can create long-term success for grassroots initiatives (Seyfang and Smith, 2007; Feola and Nunes, 2014). Further with a closer investigation of identity dynamics in local food groups the framework supports critical reflection of the groups values, goals and practices that can potentially prevent falling in the “local trap” (Born and Purcell, 2006). Studies produce descriptive-analytical knowledge by exploring how identity verification and collective identity formation can create a sense of we-ness to enable collective action for sustainability. The creation of transformational knowledge on the group level applies in a comparable way to personal level settings, focusing on how to facilitate group conditions that enhance trust and social support. In-depth exploration of identities in grassroots initiatives is needed to inform policy and community practice for sustainability (Frantzeskaki et al., 2016).

At a societal level, initiatives experiment with innovations that potentially involve structural changes. In addition, grassroots initiatives offer opportunities for collective reframing of problems and solutions as well as higher order learning. All of these are necessary preconditions for systems change (Grabs et al., 2016). An analysis applying the identity framework to grassroots initiatives shows how the creation of social spaces of consumption and production in areas such as food, textiles, transport or energy can be useful for promoting sustainability. In such cases, grassroots activists seek to mobilize communities to create new systems of provision. Comparing different forms of grassroots initiatives and their identity dynamics can aid in understanding how these create momentum and long-term commitment. Likewise, analysis contributes to a deeper understanding of individual and group behavior in the field of social mobilization for sustainable consumption (Grabs et al., 2016), both of which contribute to descriptive-analytical knowledge. Seyfang and Haxeltine (2012) stress that understanding the social psychological aspects of movements relating to identity and group cohesion is crucial for their diffusion. In the same way, immersive research on local food groups and other grassroots initiatives can create transformative knowledge on how to create conditions that enable civil society to play a role in a transformation toward sustainability and inform policy (Frantzeskaki et al., 2016; Scoones et al., 2020). Equally, it can contribute to critical reflection of underlying values of alternative structures in order to create more transformative alternatives to the conventional food system (Duell, 2013).

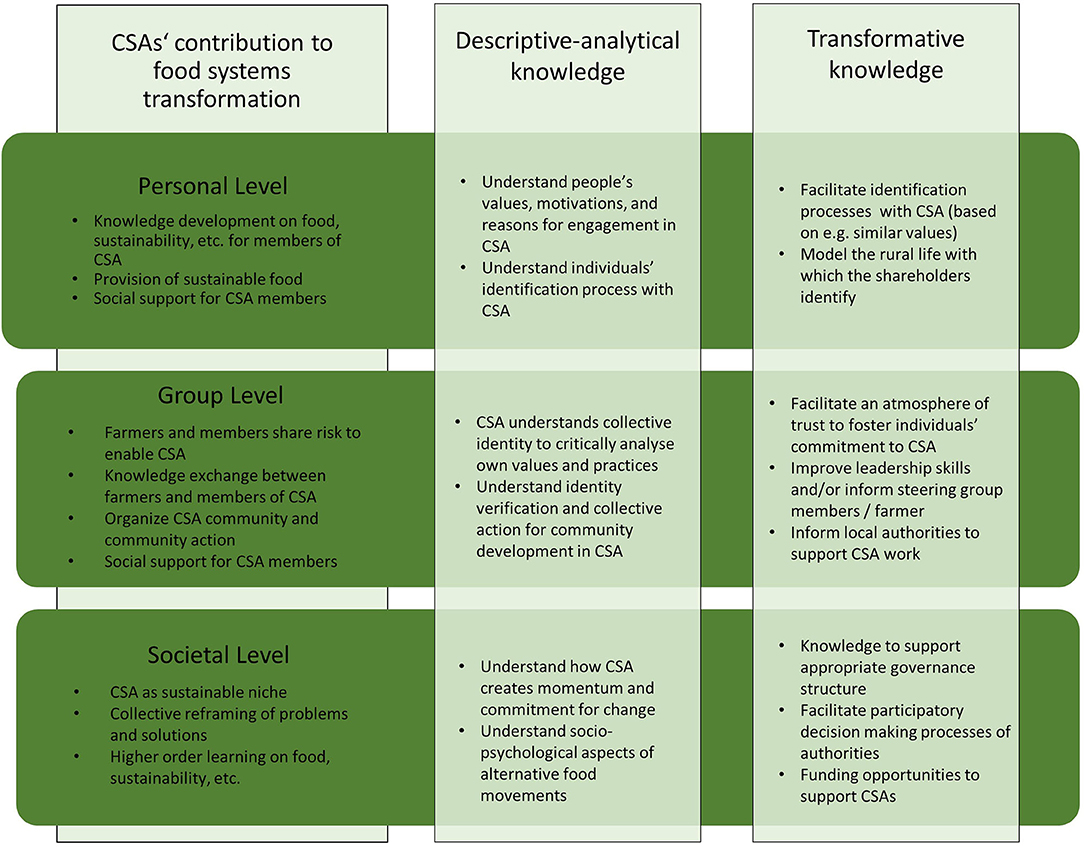

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) refers to different models of producing and consuming food locally, emphasizing organic and environmentally friendly practices, with producers and consumers sharing the risk (Pole and Gray, 2013). The community aspect appears to be central to the idea of CSAs, as they aim to create a community of like-minded people committed to the local farm. Nevertheless, research in political science, sociology and psychology suggests community appears to be weak in CSAs and participation of members decreases, describing the continuing challenge of building and maintaining a sufficiently large, committed, and stable membership in CSAs (Cone and Myhre, 2000; Pole and Gray, 2013). The application of the identity framework means that by examining identity dynamics in CSAs, scholars can achieve a deep understanding of the community aspect in CSAs, as well as how it comes together and evolves (see Figure 3). Outcomes of research can help to facilitate engagement of members in a CSA and inform policy and community practice.

Figure 3. Knowledge advancement for transformation using the example of CSAs. Developed from Grabs et al. (2016), Wiek and Lang (2016), and Weber et al. (2020).

On personal level, the proposed framework helps to explore who the people are, that are active in CSAs via examining the identification processes. The framework investigates the personal identity and therefore illuminates the social categories individuals identify with for a better understanding of values individuals hold that can explain the motivation to join a CSA. Equally, it can illuminate the process of individual's identification with the CSA. For the farmer in CSAs it is often essential “to model the rural life with which the shareholders identify” (Cone and Myhre, 2000, p. 196) and to uphold connection and personal communication (Galt, 2013; Pole and Gray, 2013). Narrative interview studies, for instance, can provide in-depth data on individuals' identities in connection to the local food initiative and contribute descriptive- analytical knowledge. Similarly, transformative knowledge on the personal level can be applied to support the farmer to facilitate identification processes in order to engage individuals and model the rural life members will identify with.

At personal and group level, the framework helps to understand the social support provided by CSAs by examining the identity verification processes that facilitate sustainable behaviors. The membership in CSAs often means a substantial change in peoples food routines when “[e]ating in season, storing, processing, and cooking an array of unexpected and unknown vegetables” (Cone and Myhre, 2000, p. 191). As Weber et al. (2020) have noted, alternative food movements establish non-conventional practices of food production and consumption that can be supported according to the transformative knowledge provided by studying verification dynamics of the identity framework. The development of trust among members and between farmers and members is equally essential to the functioning of CSAs and can be explained by the unfolding of the identity dynamics of identification, verification, and formation. As long-lasting participation of members in CSAs is essential, the exploration of identity dynamics can reveal how interactions can be managed to facilitate an atmosphere of trust to support community development in CSAs. The study by Cone and Myhre (2000) shows how high participation in CSAs correlates with a broader understanding of their impacts and a stronger commitment to their values, providing potential long-term impacts as consumers live alternative values and change behaviors (Weber et al., 2020). For exploring the group dynamics of CSAs and other initiatives, focus groups and case-study approaches will be meaningful.

The deeper investigation of people's and the groups values, motivations, and reasons for engagement that the identity framework allows for can help to employ critical reflection on who the group is and what boundaries they form. So far, studies indicate that farmers and farm members are well-educated and environmentally sustainable production and consumption is of highest relevance to them (Cone and Myhre, 2000), thus potentially reproducing privileged thinking of sustainable food systems that needs critical reflection on social justice and equity (DuPuis and Goodman, 2005; Weber et al., 2020). CSAs, as systems of believe and practices (Cone and Myhre, 2000) need to be analyzed in order to shift toward a reflexive politics of localism as DuPuis and Goodman (2005)call for. This applies equally at group and societal level. Future research with CSAs and other local food groups that apply the proposed framework can study the collective reframing of problems and solutions on societal level in order to support a transformation of food systems.

Focusing on identity and identity dynamics in local food systems and grassroots initiatives allows a better understanding of the wider benefits of participation for individuals and their wellbeing. In this regard, focusing on identity processes in grassroots initiatives can shed light on how group dynamics satisfy the basic human need for identity (Max-Neef et al., 1989; Rauschmayer and Omann, 2014). Maschkowski et al. (2014) found that identity dynamics in grassroots innovation connects with the quality of life. “By cultivating inner consistency, building social capital and initiating processes of social learning, the grassroots actors reported to have improved their perceived quality of life” (Maschkowski et al., 2014, p. 13). Additionally, group membership increases wellbeing, as socially integrated individuals tend to live “happier, healthier, and longer lives” (Wakefield et al., 2017, p. 786). From the perspective of the individual's wellbeing, the framework can highlight how participation in local food groups can satisfy human needs and contribute to quality of life. Acknowledging the potential health promotion qualities of grassroots innovation sets an alternative research agenda for transformation toward sustainability.

Furthermore, the exploration of identity in grassroots initiatives offers a fresh angle to reflect society-wide about what a good life is for individuals in a sustainable society. Research shows how civil society organizations, such as grassroots initiatives, primarily serve social needs within communities that have been neglected by the state or the market (Seyfang and Smith, 2007; Frantzeskaki et al., 2016). In this regard, the fundamental human needs framework by Max-Neef et al. (1989) can be used to explore the satisfaction of needs in local food groups and other grassroots initiatives. Consequently, the transformative potential of grassroots initiatives lies not only in individuals adopting sustainable lifestyles and cohesive societies, but also in social norms being created that holistically recognize basic human needs and can therefore foster new sustainable institutions (Rauschmayer and Omann, 2014; Frantzeskaki et al., 2016). The study of identity, human needs, and alternative consumption offers—beyond the various implications of identity dynamics to create transformative knowledge—the opportunity to ask what kind of society is sustainable. Perhaps it is a society that emphasizes values such as human needs, health, well-being, and fulfillment when engaging in transformation toward sustainability (Peterson et al., 2008).

Conclusions

This article portrays local food systems as groups and initiatives embedded in local landscapes that hold alternative values and practice sustainable lifestyles. Applying a social psychological identity lens makes it possible to identify some mechanics of how grassroots initiatives mobilize local knowledge for new and, at times, more radical approaches to sustainability. The application of the framework helps to answer questions such as who engages in a local food group; how can initiatives be maintained in the long run; and how social movements create momentum. Identification with a group as well as mutual verification of that identity within the group contributes to a positive atmosphere characterized by trust and mutual understanding. Moreover, the collective identity formation process shows in detail how a sense of we-ness can be created and nurtures collective action. This focus helps explain why individuals engage in local food groups and how identity and relational aspects can be a vital factor for the success or failure of these groups. Through the emphasis on social interactions and relational aspects in local food groups, the theoretical lens of identity dynamics presented here highlights sustainable consumption as a social space.

Local food groups, described as grassroots initiatives, can make a significant contribution to a transformation toward a more sustainable society. The application of the framework can strengthen our understanding of how grassroots initiatives can advance systemic change on personal, group, and societal levels. On a personal level, individual reasons for engagement in a group can be explored and the way individuals are supported by the group in their alternative and more sustainable consumption practices. At a group level, analysis of identity processes can help explain how to create an atmosphere that nurtures community action. On a societal level, the framework shows how sustainability problems and potential solutions are collectively reframed and how momentum is created for alternative consumption practices as a lever to change infrastructures. Insights gained from applying the framework will help to advance descriptive-analytical and transformative knowledge to analyse and facilitate grassroots initiatives, such as local food groups for change, as well as formulate appropriate policy recommendations.

Finally, by focusing on the sociability of local food groups and facilitating social spaces of consumption, the discussion offers an alternative perspective on food systems sustainability beyond economic viability. To this end, future research can explore how local food groups and other grassroots initiatives create social spaces and satisfy fundamental human needs. The identity framework presented in this paper explains why and how grassroots initiatives can be conceptualized as sustainable satisfiers of human needs. When we see identity as intimately connected to the need of social belonging, grassroots initiatives become a place for the fulfillment of social needs where the state and the market cannot or will not satisfy them. Here is an opportunity to broaden the discussion on transformation for sustainability by offering a perspective on fundamental human needs that recognizes the inherent social nature of every human being. In this light, a stronger focus on wellbeing and health promotion within sustainability research may hold great potential for the field to contribute in creating sustainable societies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was made possible within the Graduate School Processes of Sustainability Transformation, which is a cooperation between Leuphana University of Lüneburg and the Robert Bosch Stiftung. I gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Robert Bosch Stiftung (12.5.F082.0021.0).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I thank Christopher L. Cosgrove, Jordan Osterman, Sadhbh Juarez Bourke, and Jose Alejandro Mendoza Reynaud for their support and Daniel Fischer for his continuous mentorship.

References

Ajzen, I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Almerico, G. M (2014). Food and identity: food studies, cultural, and personal identity. J. Int. Bus. Cult. Stud. 8, 1.

Andorfer, V. A., and Liebe, U. (2013). Consumer Behavior in Moral Markets. On the relevance of identity, justice beliefs, social norms, status, and trust in ethical consumption. Euro. Sociol. Rev. 29, 1251–1265. doi: 10.1093/esr/jct014

Barth, M., Masson, T., Fritsche, I., Fielding, K., and Smith, J. R. (2021). Collective responses to global challenges: the social psychology of pro-environmental action. J. Environ. Psychol. 74, 101562. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101562

Batat, W., Manna, V., Ulusoy, E., Peter, P. C., Ulusoy, E., Vicdan, H., et al. (2016). New paths in researching “alternative” consumption and well-being in marketing: alternative food consumption/alternative food consumption: what is “alternative”?/rethinking “literacy” in the adoption of AFC/social class dynamics in AFC. Market. Theory 16, 561. doi: 10.1177/1470593116649793

Bauermeister, M. R (2015). Social capital and collective identity in the local food movement. Int. J. Agric. Sust. 14, 123–141. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2015.1042189

Bell, S., and Cerulli, C. (2012). Emerging community food production and pathways for urban landscape transitions. Emerg. Compl. Organ. 14, 31–44.

Biddau, F., Armenti, A., and Cottone, P. (2016). Socio-psychological aspects of grassroots participation in the transition movement: an Italian case study. PsychOpen. 4, 142–165. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v4i1.518

Born, B., and Purcell, M. (2006). Avoiding the local trap. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 26, 195–207. doi: 10.1177/0739456X06291389

Brown, E., Dury, S., and Holdsworth, M. (2009). Motivations of consumers that use local, organic fruit and vegetable box schemes in Central England and Southern France. Appetite 53, 183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.006

Brunori, G., Rossi, A., and Guidi, F. (2012). On the new social relations around and beyond food. Analysing consumers' role and action in gruppi di acquisto solidale (solidarity purchasing groups). Sociol. Rural. 52, 1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00552.x

Burke, P. J (2004). Identities and social structure: the 2003 cooley-mead award address. Soc. Psychol. Q. 67, 5–15. doi: 10.1177/019027250406700103

Burke, P. J., and Stets, J. E. (1999). Trust and commitment through self-verification. Soc. Psychol. Q. 62, 347. doi: 10.2307/2695833

Burke, P. J., and Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195388275.001.0001

Carmeli, A., Brammer, S., Gomes, E., and Tarba, S. Y. (2017). An organizational ethic of care and employee involvement in sustainability-related behaviors: a social identity perspective. J Organ Behav 38, 1380–1395. doi: 10.1002/job.2185

Cone, C. A., and Myhre, A. (2000). Community-supported agriculture: a sustainable alternative to industrial agriculture? Hum. Organ. 59, 187–197. doi: 10.17730/humo.59.2.715203t206g2j153

Connelly, S., Markey, S., and Roseland, M. (2011). Bridging sustainability and the social economy: achieving community transformation through local food initiatives. Crit. Soc. Policy 31, 308–324. doi: 10.1177/0261018310396040

Davies, A. R., and Legg, R. (2018). Fare sharing: interrogating the nexus of ICT, urban food sharing, and sustainability. Food Cult. Soc. 21, 233–254. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2018.1427924

Deaux, K (1992). “Personalizing identity and socializing self,” in Social Psychology of Identity and the Self Concept, ed G. M. Breakwell (London: Surrey University Press), 9–33.

Department for Environment Food, and Rural Affairs. (2003). Local Food—A Snapshot of the Sector: Report of the Working Group on Local Food. London: Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs.

Dobernig, K., and Stagl, S. (2015). Growing a lifestyle movement? Exploring identity-work and lifestyle politics in urban food cultivation. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 39, 452–458. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12222

Duell, R (2013). Is 'local food' sustainable? Localism, social justice, equity and sustainable food futures. N. Zeal. Sociol. 28, 123–144.

Dunne, J. B., Chambers, K. J., Giombolini, K. J., and Schlegel, S. A. (2011). What does 'local' mean in the grocery store? Multiplicity in food retailers' perspectives on sourcing and marketing local foods. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 26, 46–59. doi: 10.1017/S1742170510000402

DuPuis, E. M., and Goodman, D. (2005). Should we go “home” to eat? Toward a reflexive politics of localism. J. Rural Stud. 21, 359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.05.011

Dyck, B (1994). Build in sustainable development and they will come: a vegetable field of dreams. J. Organ. Change Manag. 7, 47–63. doi: 10.1108/09534819410061379

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., and Doosje, B. (1997). Sticking together or falling apart: in-group identification as a psychological determinant of group commitment versus individual mobility. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 617. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.617

Eriksen, S. N (2013). Defining local food: constructing a new taxonomy – three domains of proximity. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 63, 47–55. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2013.789123

Feenstra, G (2002). Creating space for sustainable food systems: lessons from the field. Agric. Hum. Values 19, 99–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1016095421310

Feola, G., and Nunes, R. (2014). Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: the case of the transition movement. Glob. Environ. Change 24, 232–250. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.011

Fielding, K. S., and Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 7, 121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

Fischler, C (1988). Food, self and identity. Soc. Sci. Inform. 27, 275–292. doi: 10.1177/053901888027002005

Fonte, M (2008). Knowledge, food and place. A way of producing, a way of knowing. Sociol. Rural. 48, 200–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00462.x

Frantzeskaki, N., Dumitru, A., Anguelovski, I., Avelino, F., Bach, M., Best, B., et al. (2016). Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 22, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.008

Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., and Reese, G. (2018). A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 125, 245–269. doi: 10.1037/rev0000090

Galt, R. E (2013). The moral economy is a double-edged sword: explaining farmers' earnings and self-exploitation in community-supported agriculture. Econ. Geogr. 89, 341–365. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12015

Gatersleben, B., Murtagh, N., and Abrahamse, W. (2014). Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 9, 374–392. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2012.682086

Gawerc, M (2016). Constructing a collective identity across conflict lines: joint israeli-palestinian peace movement organizations. Mobiliz. Int. Q. 21, 193–212. doi: 10.17813/1086-671X-20-2-193

Grabs, J., Langen, N., Maschkowski, G., and Schäpke, N. (2016). Understanding role models for change: a multilevel analysis of success factors of grassroots initiatives for sustainable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 134, 98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.061

Granvik, M., Joosse, S., Hunt, A., and Hallberg, I. (2017). Confusion and misunderstanding—interpretations and definitions of local food. Sustainability 9, 1981. doi: 10.3390/su9111981

Guthman, J (2008). Thinking inside the neoliberal box: the micro-politics of agro-food philanthropy. Geoforum 39, 1241–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.09.001

Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., and Haslam, C. (2009). Social identity, health and well-being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Appl. Psychol. 58, 1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00379.x

Hinrichs, C. C (2014). Transitions to sustainability: a change in thinking about food systems change? Agric Hum Values 31, 143–155. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9479-5

Hogg, M. A., and Hardie, E. A. (1992). Prototypicality, conformity and depersonalized attraction: a self-categorization analysis of group cohesiveness. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 31, 41–56. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1992.tb00954.x

Holloway, L., and Kneafsey, M. (2000). Reading the space of the framers 'market: a case study from the United Kingdom. Sociol. Rural. 40, 285–299. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00149

Kallbekken, S., Rise, J., and Westskog, H. (2010). “Combining insights from economics and social psychology to explain environmentally significant consumption,” in Sustainable Energy, eds K. D. John, and D. Rübbelke (London: Routledge), 127–145.

Kirwan, J., and Maye, D. (2013). Food security framings within the UK and the integration of local food systems. J. Rural Stud. 29, 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.03.002

Klandermans, B (2002). How group identification helps to overcome the dilemma of collective action. Am. Behav. Sci. 45, 887–900. doi: 10.1177/0002764202045005009

Laforge, J. M. L., Anderson, C. R., and McLachlan, S. M. (2017). Governments, grassroots, and the struggle for local food systems: containing, coopting, contesting and collaborating. Agric. Hum. Values 34, 663–681. doi: 10.1007/s10460-016-9765-5

Levkoe, C. Z (2011). Towards a transformative food politics. Local Environ. 16, 687–705. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2011.592182

Maschkowski, G., Schäpke, N., Grabs, J., and Langen, N. (2014). Learning from Co-Founders of Grassroots Initiatives: Personal Resilience, Transition, and Behavioral Change - A Salutogenic Approach, Resilience Conference. Montpellier, France.

Max-Neef, M., Hevia, A., and Hopenhayn, M. (1989). Human scale development: an option for the future. Dev. Dial. 1, 7–80.

Maye, D., and Duncan, J. (2017). Understanding sustainable food system transitions: practice, assessment and governance. Sociol. Rural. 57, 267–273. doi: 10.1111/soru.12177

McCracken, G. D (2002). New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Melucci, A (1989). Nomads of the Present: Social Movements and Individual Needs in Contemporary Society. London: Hutchinson Radius.

Mock, M., Omann, I., Polzin, C., Spekkink, W., Schuler, J., Pandur, V., et al. (2019). “Something inside me has been set in motion”: exploring the psychological wellbeing of people engaged in sustainability initiatives. Ecol. Econ. 160, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.02.002

Moreno, F., and Malone, T. (2021). The role of collective food identity in local food demand. Agric. Resour. Econom. Rev. 50, 22–42. doi: 10.1017/age.2020.9

Mougeot, L. J. A (2006). Growing Better Cities: Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Development. Ottawa, ON: International Development Research Centre.

Nevens, F., Frantzeskaki, N., Gorissen, L., and Loorbach, D. (2013). Urban transition labs: co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Product. 50, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.001

Papaoikonomou, E., Cascon-Pereira, R., and Ryan, G. (2016). Constructing and communicating an ethical consumer identity: a social identity approach. J. Consum. Cult. 16, 209–231. doi: 10.1177/1469540514521080

Peterson, C., Park, N., and Sweeney, P. J. (2008). Group well-being: morale from a positive psychology perspective. Appl. Psychol. 57, 19–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00352.x

Pitt, H., and Jones, M. (2016). Scaling up and out as a pathway for food system transitions. Sustainability 8, 1025. doi: 10.3390/su8101025

Poças Ribeiro, A., Harmsen, R., Feola, G., Rosales Carréon, J., and Worrell, E. (2021). Organising alternative food networks (AFNs): challenges and facilitating conditions of different AFN types in three EU countries. Sociol. Rural. 61, 491–517. doi: 10.1111/soru.12331

Pole, A., and Gray, M. (2013). Farming alone? What's up with the “C” in community supported agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 30, 85–100. doi: 10.1007/s10460-012-9391-9

Rauschmayer, F., Bauler, T., and Schäpke, N. (2015). Towards a thick understanding of sustainability transitions — linking transition management, capabilities and social practices. Ecol. Econ. 109, 211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.11.018

Rauschmayer, F., and Omann, I. (2014). “Well-being in sustainability transitions: making use of needs,” in Sustainable Consumption and the Good Life, eds K. Lykke Syse, and M. Lee Mueller (New York, NY: Routledge), 111–125. doi: 10.4324/9781315795522-8

Ray, S., Kim, S., and Morris, G. J. (2014). The central role of engagement in online communities. Inform. Syst. Res. 25, 528–546. doi: 10.1287/isre.2014.0525

Rotmans, J., and Loorbach, D. A. (2010). “Towards a better understanding of transitions and their governance. A systemic and reflexive approach,” in Transitions to Sustainable Development. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change, ed J. Grin, J. Rotmans, J.W. Schot (New York, NY: Routledge), 105–222.

Ruby, M. B., Walker, I., and Watkins, H. M. (2020). Sustainable consumption: The psychology of individual choice, identity, and behavior. J. Soc. Issues 76, 8–18. doi: 10.1111/josi.12376

Scoones, I., Stirling, A., Abrol, D., Atela, J., Charli-Joseph, L., Eakin, H., et al. (2020). Transformations to sustainability: combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 42, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004

Seyfang, G., and Haxeltine, A. (2012). Growing grassroots innovations: exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. Gov. Policy 30, 381–400. doi: 10.1068/c10222

Seyfang, G., and Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Polit. 16, 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

Stets, J. E., and Biga, C. F. (2003). Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociol. Theory 21, 398–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-9558.2003.00196.x

Stets, J. E., and Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social. Psychol. Q. 63, 224. doi: 10.2307/2695870

Swann, W (1983). “Self-Verification: bringing social reality into harmony with the self,” in Social Psychological Perspectives on the Self (Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum), 33–66.

Taylor, V., and Whittier, N. E. (1992). “Collective identity in social movement communities: Lesbian feminist mobilization,” in Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, eds A. D. Morris, and C. M. Mueller (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 104–129.

Turner, J. C (1982). “Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group,” in Social Identity and Intergroup Relations, ed H. Tajfel (Cambridge, Paris, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 15–41.

Turner, J. H (2011). Extending the symbolic interactionist theory of interaction processes: a conceptual outline. Symbol. Interact. 34, 330–339. doi: 10.1525/si.2011.34.3.330

Wakefield, J. R. H., Sani, F., Madhok, V., Norbury, M., Dugard, P., Gabbanelli, C., et al. (2017). The relationship between group identification and satisfaction with life in a cross-cultural community sample. J Happiness Stud. 18, 785–807. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9735-z

Weber, H., Poeggel, K., Eakin, H., Fischer, D., Lang, D. J., Wehrden, H., et al. (2020). What are the ingredients for food systems change towards sustainability?—Insights from the literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 15:113001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab99fd

Wiek, A., and Lang, D. J. (2016). “Transformational sustainability research methodology,” in Sustainability Science: An Introduction, eds H. Heinrichs, W. J. M. Martens, G. Michelsen, and A. Wiek (Dordrecht: Springer), 31–41. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-7242-6_3

Keywords: identity dynamics, social sustainability, local food systems, transformation, social identity, collective identity, grassroots initiatives

Citation: Poeggel K (2022) You Are Where You Eat: A Theoretical Perspective on Why Identity Matters in Local Food Groups. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:782556. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.782556

Received: 24 September 2021; Accepted: 13 January 2022;

Published: 23 February 2022.

Edited by:

Andrea Pieroni, University of Gastronomic Sciences, ItalyReviewed by:

Michele Filippo Fontefrancesco, University of Gastronomic Sciences, ItalyLissy Goralnik, Michigan State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Poeggel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karoline Poeggel, karoline.poeggel@leuphana.de

Karoline Poeggel

Karoline Poeggel