- 1Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 2Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

In this perspective paper, we present a case study of food systems pedagogy and critical community-university engagement within a school of public health at a large and public research university. We start by providing a contextual foundation for the importance of intentionally centering equity-oriented curriculum and community partnerships in academic settings. After highlighting institutional mandates and curricular innovations from a food systems capstone course, we utilize key questions of critical community-engaged scholarship to analyze the case and critically reflect on gaps and opportunities for ongoing growth.

Introduction

Food systems degrees in the US and Canada often include opportunities for community-university engagement and yet rarely center equity and anti-racism as core values and learning outcomes for students (Meek and Tarlau, 2015; Valley et al., 2020). This critical perspective is missing from most food systems programs (Valley et al., 2020). While some programs do incorporate or prioritize anti-racist approaches, they are often marginalized, underfunded, and largely undocumented (Telles, 2019). Community-university engagement that is not explicitly oriented toward equity and anti-racism can serve to reinforce racially exclusionary spaces and power imbalances (Gordon da Cruz, 2017; Telles, 2019).

Academic institutions can often be exploitative forces in and of themselves by way of excluding participation along lines of race, gender, culture, and socioeconomic class, and via a long and fraught history of abuses and betrayals carried out by academics and universities against oppressed communities. Extraordinary cost, prohibitive secondary education performance requirements, and a general air of academic exclusivity have systematically and intergenerationally deprived many communities of the resources and opportunities that universities have to offer. At the same time, these factors have barred many who are unequivocal experts on the realities and needs of their communities from having a voice in the development of methods, knowledge bases, and curricula that both claim to adequately explain the plights of and largely define the scope and scale of potential solutions for oppressed communities. This deficit is especially glaring as food systems academic programs proliferate. With these considerations acknowledged, anything less than intentionally collaborative and critically reparative partnerships with communities that continue to suffer injustices linked to academic institutions, is effectively complacent and implicitly supportive of ongoing inequity. In this way, the balance of power remains oriented to a status quo that prioritizes Whiteness and white supremacy. Communities of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, who are so often excluded from institutional leadership roles and academic positions, must be affirmed in their expertise and ceded a high level of directive sovereignty in order to combat these persistent problems.

Food systems degrees traditionally emerge from a variety of disciplines, including agricultural sciences, environmental studies, sociology, anthropology, and more recently, public health. Food and food systems embody many key public health concerns, including diet-related diseases, climate change, and environmental and occupational health. In return, public health increasingly brings forward a commitment to health equity, which can be considered “social justice in health” (Weiler et al., 2015). Health equity is achieved when everyone, regardless of race and identity, has the opportunity to attain their highest level of health (Weiler et al., 2015). Since racism structurally limits the social determinants of health, including food security, housing, education, and employment, anti-racism is a necessary and key component of health equity. The American Public Health Association (APHA) recognizes structural racism and specifically anti-Black racism as a public health crisis and as a fundamental cause of racial health inequities (APHA, 2020). These inequities and their rootedness in persistent social structures that enforce racist and exploitative systems are evidenced by disparate rates of food insecurity across communities and through labor injustice throughout the food supply chain.

We therefore present a practice-based and reflective case study to document a pedagogical focus on equity and anti-racism in a large, community-engaged food systems course at a school of public health within a public research university. Since such documentation is infrequent, this outlier case provides utility through rich and atypical insights (Stake, 1995). In particular, we present the case of the Food Systems Capstone (NUTR 493) of the Food Systems, Nutrition, and Health (FSNH) Bachelor of Arts major within the School of Public Health (SPH) at the University of Washington (UW). In 2016, the UW SPH adopted a school-wide learning competency related to equity and anti-racism: “Recognize the means by which social inequities and racism, generated by power and privilege, undermine health” (Hagopian et al., 2018). While this competency acknowledged the School's orientation toward racial equity, it is notable that “recognize” aligns only with the first order of in Bloom's Taxonomy, which progresses from knowledge and comprehension to application, analysis, evaluation, and creation (Adams, 2015; Harvard Medical School, 2018). As such, it is only an initial step of an anti-racist learning journey. Since the introduction of this competency, significant work has been initiated within the School to support both knowledge and action. By 2019, the UW SPH Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Action Plan was released (UW SPH, 2019) with related action steps to move the SPH, and its departments, programs, and workgroups, toward its EDI goals. In 2020, during the height of Black Lives Matter protests, over 300 SPH students, staff, and faculty signed a petition calling for universal anti-racism training (UW SPH, 2020). That fall, the School launched its anti-racism training, which is ongoing. An article from the Spring of 2021 in the UW SPH magazine quoted the Assistant Dean EDI, Dr. Victoria Gardener, “Anti-racism work is a journey and we're at the very beginning” (Chandler, 2021).

The FSNH major, which launched in 2019, adapted the School's competency into the following learning objective: “Articulate how social inequities and racism, generated by power and privilege, are embedded within food systems and undermine health.” “Articulate” is a second order verb in Bloom's taxonomy, aligned with comprehension. This learning objective for the FSNH program is achieved primarily through the Food Systems Capstone and thus remains somewhat marginalized within the degree. Based on the community-identified projects and the general outlook of the capstone teaching team, the course has been moving into Bloom's third order of action and specifically the field of reparative action, inspired by justice framework elements of participation, horizontalism, and equity outcomes. In this way, we posit that the capstone is meeting and exceeding the scope of both the School's resolution and the FSNH major's learning objective.

The food systems capstone at the university of washington school of public health

After the FSNH major launched in 2019, the first capstone was offered in the Spring quarter of 2020 with 45 students; the first full academic period under the COVID-19 pandemic. By the second remote offering in the Spring quarter of 2021, there were 105 students, and the numbers continued to grow to over 130 students in 2022. The capstone learning objectives include supporting students to:

• Apply food systems concepts to real-world circumstances and challenges.

• Practice the methods used to conduct food systems research.

• Analyze the impacts of food systems on population health.

• Develop recommendations and articulate them using clear and effective oral and written communication.

• Appreciate the breadth and depth of professional opportunities in food systems, nutrition, and health.

• Articulate how social inequities and racism, generated by power and privilege, are embedded within food systems and undermine health.

As described in course materials and online, the capstone provides a culminating academic endeavor for FSNH students to apply knowledge and skills acquired in their courses to specific food systems problems or opportunities. Course content focuses on systems thinking, community engaged scholarship, anti-racism and equity, and opportunities for students to grapple with real world, complex issues across food systems. Students work in teams of four to five students, with direction from the teaching team (instructor, project coordinator, teaching assistants) and in partnership with community leaders, who identify project opportunities for the students. We connected with community partners primarily through the professional networks of the instructor (YS) and other FSNH faculty members and invited them to share their “wish list” projects, especially those that would benefit from undergraduate creativity and energy. Community partners include leaders and representatives from community-based organizations, local and county government, social enterprise, and other key stakeholders. Partners represent farm and food systems organizations and initiatives, public agencies, food banks, food hubs, and more. Community partnerships are invited for one or multiple years.

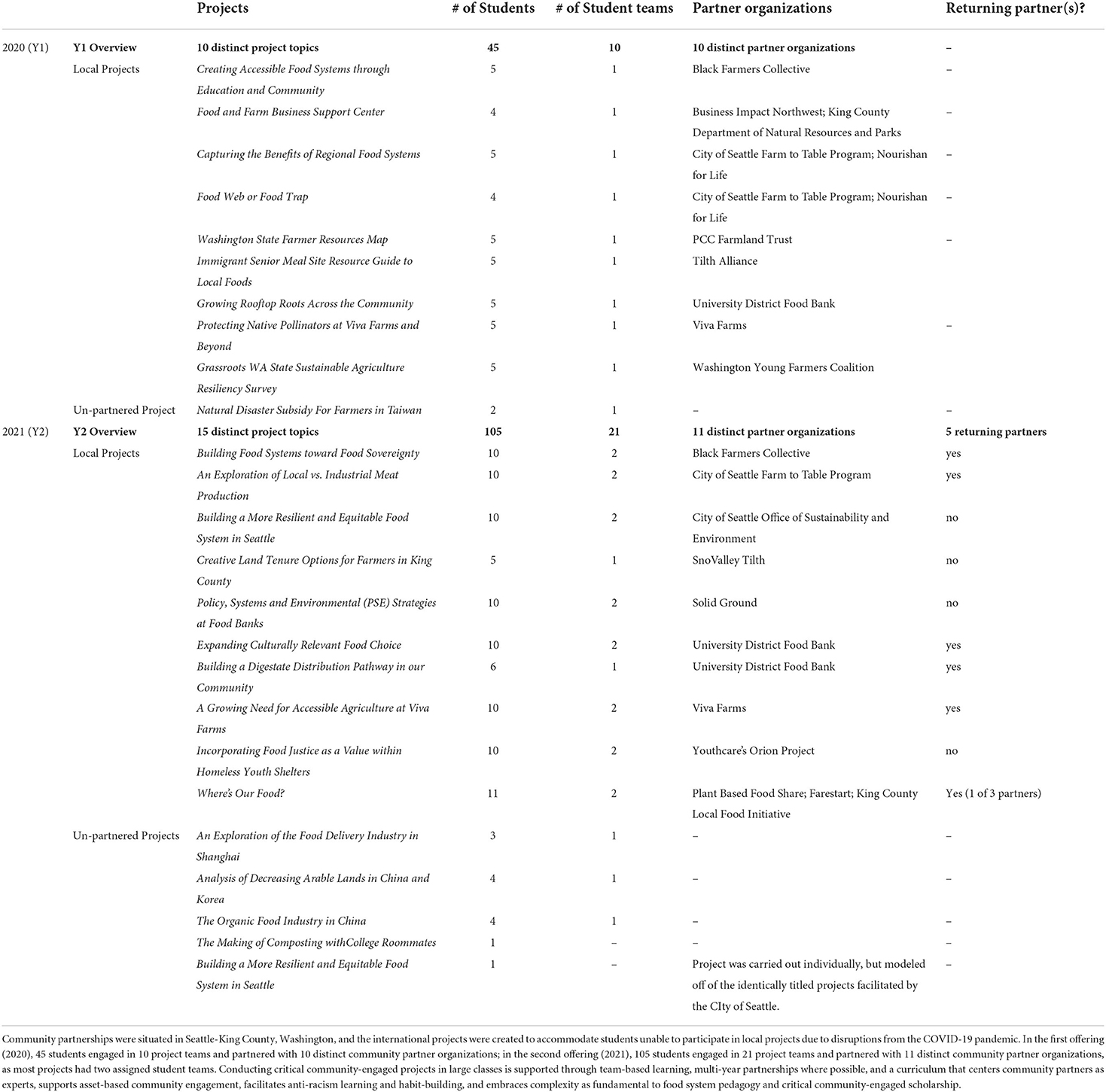

For the 2020 and 2021 capstone offerings, we invited all projects to relate broadly to the theme of growing a resilient and equitable food system within Seattle-King County and Washington state. While resilience and equity are both connected within sustainable food systems, it is essential to acknowledge the breadth of meaning that is attributed to these terms. Some of our partners outwardly embrace decolonial and anti-capitalist values, perspectives, and missions, while others work more firmly within the confines of neo-colonial structures and capitalism. The projects that this range of partners brought forward ranged from mainstream food security work to alternative food systems that explicitly work for food justice and sovereignty. The 2020 and 2021 community partner organizations, project titles, and other relevant details are listed in Table 1 and can also be found on our Student Projects webpage. While each project is different, all student teams are guided through collaborative learning processes to support co-creation of a team charter, project proposal, and final outcomes that have included literature reviews, comparisons of existing programs, educational resources, infographics, website mockups, social media content, and other materials requested by their community partner. In addition to skills in meeting facilitation, project management, written and oral communication, and critical reflection, specific learning activities are tied to the projects' goals and outcomes. Over the quarter, students consult with and report back to their community partner multiple times to solicit feedback and ensure that they are on track. This teamwork, along with individual writing assignments, is also assessed by the capstone instructional team.

Table 1. An overview of the community partners and community-engaged food system projects from the University of Washington Food Systems Capstone (NUTR 495) in 2020 and 2021.

Curricular and community partner strategies related to equity

Curricular strategies for racial equity

In both 2020 and 2021, our learning environment was necessarily informed by the COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests. These phenomena impacted our students personally and in their studies of food systems. As was planned prior to the pandemic or social unrest, we drew on the 21 Day Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge from Food Solutions New England as a guide for learning, reflecting, and acting on issues related to identity and racial equity within food systems. Food Solutions New England is a regional food systems initiative consisting of six states in the Northeast United States. This network began publicly centering racial equity in 2013 and began to organize and host the Challenge in 2015. By 2021 they had over 7000 participants. The Challenge provides curated resources and daily reflection questions and activities to support understanding and dismantling white supremacy in individuals and organizations actively working to become anti-racist and promote justice and liberation. Since the capstone runs over a 10-week quarter, we use a modified version of the 21 Day Challenge to engage with the readings, presentations, and opportunities for reflection.

We found that our students generally appreciated the opportunity to participate in the Racial Equity Habit Building Challenge. The relatively digestible, multimedia nature of the resources likely supported student learning and motivation to keep engaged with the material and assignments. The iterative approach of “Learn, Reflect, Act” provided a framework for students to connect the Challenge with their community-based project. For their final presentations and submissions, each team was asked to reflect on their project's implications for resilience and equity.

Community partner strategies

The first two capstone offerings were held remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Classes, meetings, and presentations all occurred over Zoom. Students and partners generally managed the online environment, and in fact, may have met more often due to the accessibility of video calls. While the remote environment provided some ease and efficiency, it was deficient by other measures, including limiting the amount of networking that was possible and also that was planned as we chose not to host additional online meetings for the community partners. As we transition from remote offerings to in-person, we will reconsider opportunities to support community partner networking.

As of 2021 (the second offering) we started paying a nominal sum for each community-based project as a way of honoring partners' time and expertise, as well as their important contributions to the students' education. While it was encouraging to be able to offer some form of financial compensation, greater support is needed. This may include additional funding to better support community partnerships, along with a greater consideration of the ethical responsibilities of public institutions to share and redistribute resources to the communities in which they are located.

Critical community-engaged scholarship questions, strategies, and outcomes

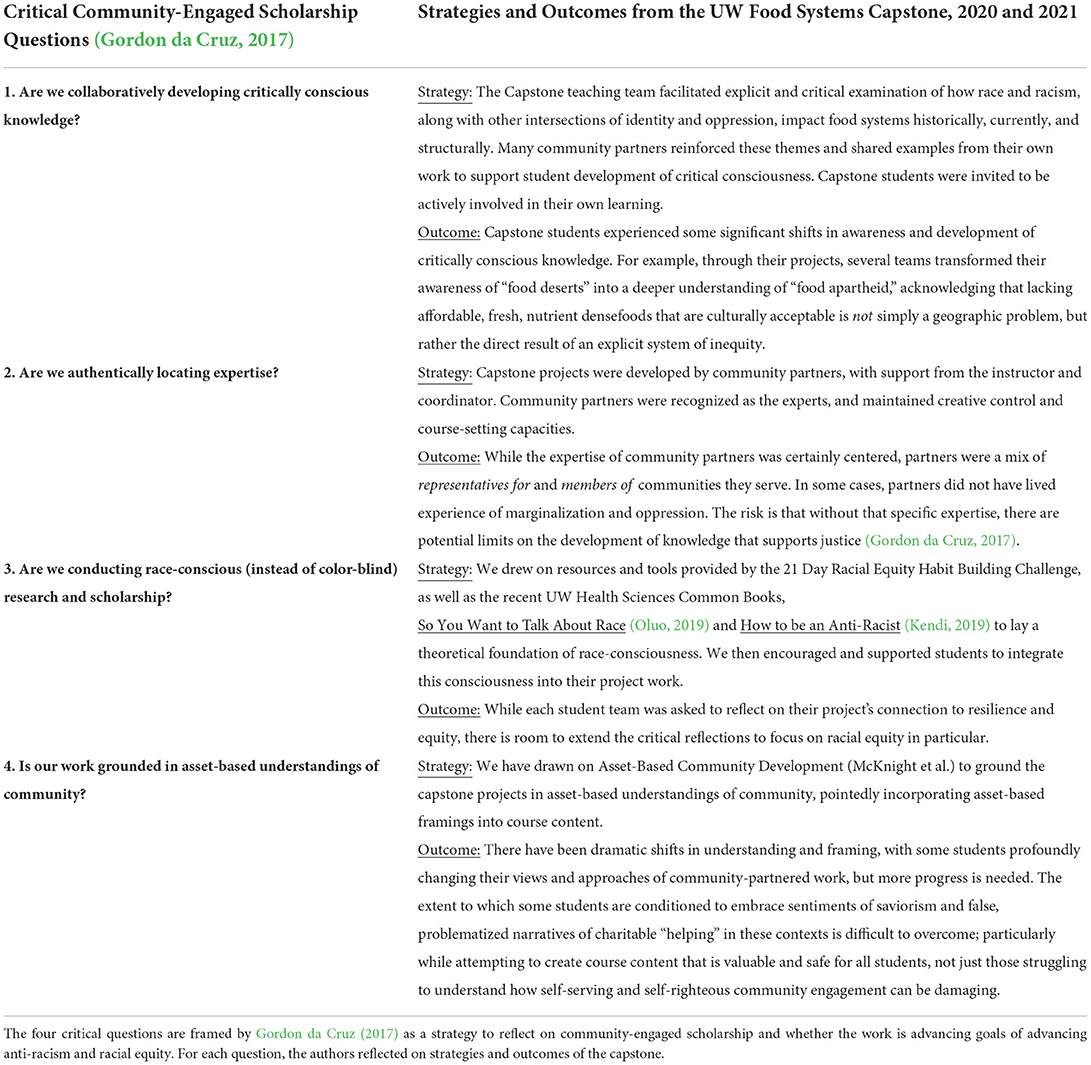

Establishing pathways of reflexivity and action based on lessons learned in the first years of a course is an ongoing process. Contending with a new program, a pandemic, and a time of significant social change while attempting to embrace values and goals that do not always fit effortlessly within surrounding institutional structures, it has been somewhat difficult to apply tangible frameworks to evaluate the course's successes and short-comings. In an effort to contextualize and clarify both our progress and areas most in need of improvement, we have used the four critical questions presented by Gordon da Cruz (2017) to reflect on community-engaged scholarship within the UW Food Systems Capstone. Table 2 lists the questions, with specific strategies and outcomes from the first two offerings.

Table 2. Questions, strategies, and outcomes of critical community-engaged scholarship within the first 2 years of the UW Food Systems Capstone, 2020 and 2021.

Discussion

We utilized Gordon da Cruz (2017) framework to reflect on whether the food systems capstone is advancing anti-racism and racial equity (see Table 2). These four critical questions interrogate how knowledge is constructed, how expertise is defined and located, whether research and scholarship are race conscious, and the power of asset-based understandings of community. Stronger strategies lead to more beneficial outcomes for both students and community partners. The capstone is orienting toward critical community-engaged scholarship, yet as noted in the strategies and outcomes column, there is room to grow in how the instructor and program are able to support truly equitable community partnerships, as well as student engagement with race conscious research and scholarship.

All participants - students, teaching team, and community partners - engage as part of an iterating and evolving community of learners. Such learning environments often hold the best intentions to contribute positively, and yet still have potential to cause hurt and harm in various ways. Critical reflection is therefore essential to the process of learning and includes highlighting and considering what does not work well, why, and how it can be improved over time. The capstone continues to develop with each offering. Student and community partner feedback from previous quarters is considered carefully and incorporated as possible. The instructor participates in ongoing skill-building to center anti-oppressive principles within instructional strategies; ideally these opportunities will be better supported for the full teaching team. As we transition back to in-person engagement, we are planning for more hands-on learning opportunities for the students, as well as for networking and celebration that includes community partners. We anticipate these strategies will help to deepen relationships that are fundamental to this learning experience.

While there was generally positive student feedback regarding the racial equity resources and opportunities for engagement, there exists a broader struggle with anti-racist curriculum in an academic context that emerged from and is still ruled by inequity. Structural racism still informs institutions, curricular norms and requirements, and the students who are accepted to college and end up in classrooms. As we strive to embed racial equity content that is digestible and engaging for all students, we also attempt to reconcile the context of an educational system that in many ways still embraces and perpetuates white supremacy. At worst, tailoring materials to be accessible for all students lowers the level of comprehensive anti-racist curriculum that is viable and may compromise the experience of BIPOC students who are already well-versed with these concepts. Regardless of good intentions, catering racial equity curriculum to the lowest strata of student understanding can effectively be experienced as yet another manifestation of structural racism. On the other hand, and at best, embracing a racial equity curriculum for all can facilitate BIPOC and white students collaborating in critical community-engaged scholarship through development of an equity-oriented community of learners. Over time, these cohorts will ideally comprise allied colleagues committed to racial equity.

We received student feedback articulating versions of these perspectives. We tried to be as mindful of these dynamics as possible, but results were imperfect. The process of improvement will be iterative and perhaps ultimately restrained until oppressive institutional and social structures shift, white students enter the course with more thorough conceptions of inequity, and our program's instructor base diversifies.

How does academia address the challenge of simultaneously introducing, instructing, and training a diverse but largely white student body regarding anti-racism, while at the same time creating a valuable, safe, non-traumatic experience for marginalized students who may be more knowledgeable and better qualified to speak on these topics of equity and oppression than their white instructor(s)? We acknowledge the limitations of academia, as well as our own particular context. In our program, we operate within a primarily white faculty base and instructional team. Facilitating learning on these topics for students of color requires acknowledging and valuing their lived experiences and acute awareness of how interlain sociostructural oppressions disproportionally exclude people of color from academia. White supremacist ideology is evidenced in academic institutions through institutional policy, funding structures, long-established disciplinary norms, and even disciplines themselves. Instructors and facilitators have identities, life experiences, and positions of privilege that can be vastly different from students; reflexively and critically situating ourselves may increase opportunities to deliver curriculum that is valuable and safe to students who know and experience oppression actively.

Positionality statements

This case study is situated in a critical epistemological foundation including self-reflexivity around “how, why, and in what ways research is conducted and an understanding of the role of power, privilege, and visibility in the research process” (Jacobson and Mustafa, 2019). The authors therefore share our positionality statements here.

The authors are employed by UW, which sits on traditional and unceded Coast Salish territory, specifically of the Suquamish, Tulalip, and Muckleshoot nations and the Duwamish Tribe. The authors collaborated on the first two offerings of the Food Systems Capstone (2020, 2021), YS as instructor and AI as project coordinator, and participated in the co-constructed community of learners encompassing students, teaching team, and community partners. YS identifies as white, Jewish Ashkenazi, granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, cis-woman (she/her pronous), parent; her background in plant biology, soil ecology, food system networks, and community ownership informs her work on food justice and sustainability. AI identifies as a white, nonbinary person and uses either he/him or they/them pronouns; AI's food systems research and educational work is informed by a background in anthropology and consistent, critical consideration of power structures and systemic violence.

Conclusion

Actionable strategies to advance equity and positive social change remain largely missing and undocumented from most contemporary food systems programs in the US and Canada. There is a need and opportunity to center racial equity and critical community-university engagement to advance justice in and out of the classroom. Equity work cannot be successful while the voices, views, and protocols of those individuals and institutions benefiting from inequity are still the loudest. We recognize there are inherent limitations when white people lead anti-racist curricula; we also embrace the opportunity to use our positions of privilege to actively break down exclusive academic spaces and center the wisdom and expertise of community representatives to help grow equitable, mutual, and critical collaborations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YS initially conceived of the paper and drew on unpublished materials from her dissertation to develop an initial draft. AI contributed significantly in extending the critical lens and expanding systemic contexts. YS and AI wrote the paper, conducted final reviews of the entire paper, and contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank students and community partners of the 2020 and 2021 Food Systems Capstone at the University of Washington (UW). Funding to support community partnerships was made possible through gifts to the Food Systems, Nutrition, and Health Incubator Fund, which was established by alumni to promote and support the successful launch of the food systems major at UW.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling Editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors YS.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, N. E. (2015). Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 103, 152–153. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010

APHA (2020). Structural racism is a Public Health crisis: Impact on the Black community policy number: LB20-04. American Public Health Association. Available online at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2021/01/13/structural-racism-is-a-public-health-crisis (accessed August 15, 2021).

Chandler, A. (2021). Working Toward Becoming an Anti-racist School of Public Health. UW SPH Magazine. Available online at: https://sph.washington.edu/magazine/2021spring/becoming-an-anti-racist-school (accessed May 18, 2022).

Gordon da Cruz, C. (2017). Critical community-engaged scholarship: communities and universities striving for racial justice. Peabody J. Educ. 92, 363–384. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2017.1324661

Hagopian, A., McGlone West, K., Ornelas, I. J., Hart, A. N., Hagedorn, J. C, and Spigner (2018). Adopting an anti-racism public health curriculum competency: the university of washington experience. Public Health Rep. 133, 507–513. doi: 10.1177/0033354918774791

Harvard Medical School (2018). Writing Learning Objectives. Office of Educational Quality Improvement. Available online at: https://meded.hms.harvard.edu/files/hms-med-ed/files/writing_learning_objectives.pdf (accessed May 18, 2022).

Jacobson, D., and Mustafa, N. (2019). Social identity map: a reflexivity tool for practicing explicit positionality in critical qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 18, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/1609406919870075

Meek, D., and Tarlau, R. (2015). Critical food systems education and the question of race. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 5, 131–135. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.021

Telles, A. B. (2019). Community engagement vs. racial equity: can community engagement work be racially equitable? Metropolitan Universities. 30, 95–108. doi: 10.18060/22787

UW SPH (2020). Commitment to Universal Anti-Racism Training. School of Public Health (2020). Available online at: https://sph.washington.edu/commitment-universal-anti-racism-training (accessed May 18, 2022).

UW SPH. (2019). A Roadmap for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. UW School of Public Health. Available online at: https://sph.washington.edu/sites/default/files/2019-07/UWSPH-EDI-Action-Plan-2019.pdf?mkt_tok=NjIyLUxNRS03MTgAAAAAYVax8IwqLIZVtbRhWvTRSBdAuvQeFuFAnG6c5odTKTHe813J-OVEjC6czHiW (accessed May 18, 2022).

Valley, W., Anderson, M. A., Tichenor Blackstone, N., Sterling, E., Betley, E., Akabas, S., et al. (2020). Towards an equity competency model for sustainable food systems education programs. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 8, 33 doi: 10.1525/elementa.428

Keywords: food systems pedagogy, critical community-engaged scholarship, public health, case study, anti-racism, undergraduate capstone

Citation: Sipos Y and Ismach A (2022) Critical community-engaged scholarship in an undergraduate food systems capstone: A case study from Public Health. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:762050. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.762050

Received: 20 August 2021; Accepted: 01 July 2022;

Published: 26 July 2022.

Edited by:

Will Valley, University of British Columbia, CanadaReviewed by:

Miranda Hart, University of British Columbia, CanadaNicholas R. Jordan, Independent Researcher, Saint Paul, MN, United States

Copyright © 2022 Sipos and Ismach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yona Sipos, eXNpcG9zQHV3LmVkdQ==

Yona Sipos

Yona Sipos Alan Ismach

Alan Ismach