- Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, United States

More than ever before, the COVID-19 pandemic has required qualitative researchers to develop open-ended, flexible, and creative approaches to continuing their work. This reality includes the adoption of open-ended research goals, a willingness to continually adapt to unpredictable and changing (viral) circumstances, and a commitment to opening toward and adhering to participants' preferences. This ethos is entrenched in a web of moral responsibility and a future anteriorized ethics. We reflect on pandemic-era ethical and methodological considerations in light of Fortun's studies of toxic contamination, research conducted in conflict settings, and researcher experiences during the early stages of COVID-19. Drawing from our own experiences and bearing in mind our own entangled web(s) of moral responsibility, we explore the future anteriorized ethics and methodological landscape of the “new normal” pandemic (potentially endemic) era. We reflect on what data we are able to gather and what data we dare to gather in the context of COVID-19, ultimately asking how qualitative researchers can maintain a safe and ethical environment for conducting research. To this end, we emphasize a recognition of our obligations to our research partners and ourselves in order to reduce risk by turning doubts and concerns into opportunities during project development and fieldwork and transforming participants into collaborators in spaces of uncertainty. Through targeted reflections on our processes of adaptation in research, we examine how scholars can perform relatedness, knowledge, reasonableness, and care in the midst of a risky, compromised research context.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic unsettles the world as we know it, disrupting our personal and professional lives in innumerable ways. This disruption extends to scholarly research, making face-to-face and field-based methods difficult. While the primary mode of adaptation in everyday life has been a move to virtual interactions, key interpersonal aspects of participatory and qualitative methods, like building trust and close collaboration (Hall et al., 2021), do not always easily translate to virtual life. Previously-challenging components of in-person interaction are suddenly put into stark relief with COVID: the difficulty of developing rapport with interlocutors, an absence of shared sensations, barriers to conveying the nuance of a question or perceiving the full meaning of an answer during an interview, and reduced or non-existent opportunities for observing social environments. Some of these methodological hurdles had the potential to disturb research processes and outcomes even prior to the pandemic, particularly in conflict settings like humanitarian crises, among war-affected populations, or in regions with endemic or pandemic diseases. Yet the overarching globality of the COVID-19 crisis demands further, wide-ranging reflection on our obligations and approaches as researchers.

In this paper, we discuss how the context of COVID-19 calls for a research ethos rooted in open methods and entrenched in a web of moral responsibility and ethics (Fortun, 2003, 2011, 2012). To explore this imperative, we connect participatory action and community-based participatory research to our geographies of fermentation framework, offering vignettes that highlight the challenges of doing “fieldwork without the field.” Drawing inspiration from existing qualitative research on toxic contamination as well as previous studies conducted in conflict and pandemic settings, we describe how we navigated COVID-related barriers virtually and in-person in our research projects to explore potential methodological adaptations for research conducted in “pandemic times.”

A future anteriorized ethics for risky business: Recognizing emergent risks in research

COVID-19 has become an ordinary feature of our everyday existence since early 2020, with myriad impacts to lives and livelihoods. This pandemic is socially and geographically uneven, adversely affecting marginalized groups at disproportionately-high rates. The pervasive, persistent nature of this pandemic makes it difficult to see beyond the present moment. However, we can understand the risks of disease contamination as extending across time and space; in this way, the past and present are folded into our obligations for the future. Writing about toxic contamination—the condition or process of certain materials, like heavy metals, plastics, pesticides, or chemicals causing harm or death to organisms and environments—in late industrialism, Fortun (2012, p. 450) argues: “The future is anteriorized, which folds the past into the way reality presents itself, setting up both the structures and the obligations of the future.” Similarly, COVID-19 inhabits both the present and what is to come, knitting a “lace of obligation” that binds the ethics of today together with an unfolding tomorrow (Derrida, 1992, p. 329).

Consequently, scholars face increased uncertainty in the process of conducting research and a sense of continuous risk to bodies, with impacts potentially extending into the future. Some of these struggles are not new, as similar methodological hurdles hinder research conducted in war zones, humanitarian disasters, and regions with endemic or pandemic diseases. Yet, the material conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic bring risk nearer to the bodies of interviewers, participants, community stakeholders, and volunteers in many settings, even relatively-privileged ones. As Fortun suggests, bodies “are not conceived as enclosed properties,” but rather “recognized as subject to trespass, as open systems” that can be contaminated (2011, p. 242), an ontological reality we suggest applies to the swift, viral contamination of COVID-19. Despite our attempts to wall off our bodies from possible harm with protective equipment and vaccines, we remain vulnerable, as viruses and other microbes are difficult to keep out. Fortun (2011) suggests health and disease are processes, which is illustrative of how COVID-19's global and local epidemiological contexts constantly evolve1. As such, potentially compromised healthy bodies engaged in research and facing a mutating viral disease become yoked with collective responsibilities to safeguard individual and communal health, necessitating collaborative, ethical research. Applying insights inspired by extant literature chronicling research in conflict settings, environmental health sciences, and emergent literature on participatory research conducted during COVID-19, we endeavor to add our own experiences as early-career scholars to the ongoing conversation about the conduct of qualitative research in pandemic times.

Literature on methods in crisis settings

An enduring pandemic presents challenges to conducting fieldwork akin to other crisis settings. Ford et al. (2009, p. 1) suggest “the instability of conflict-affected areas, and the heightened vulnerability of populations caught in conflict, calls for careful consideration of the research methods employed, the levels of evidence sought, and ethical requirements.” A lack of infrastructure, taxed human resources, and the presence of violence can limit access to populations over time and restrict researchers' capacity to conduct research, so that studies in conflict settings may be conducted suboptimally and sometimes abandoned altogether, justifiably taking “second place to the provision of live-saving assistance” (Ford et al., 2009). Mackenzie et al. (2007, p. 300) argue that research with refugees is rife with significant ethical challenges, including the “difficulties of constructing an ethical consent process and obtaining genuinely informed consent,” and counsel researchers to “seek ways to move beyond harm minimization as a standard for ethical research and recognize an obligation to design and conduct research projects that aim to bring about reciprocal benefits for refugee participants and/or communities.”

Afifi et al. (2020, p. 381) agree that “research in humanitarian crises is complex, both ethically and methodologically,” but they suggest that practices of community-based participatory research (CBPR), such as “prioritizing knowledge of partners or centering power with community members, [can] provide the potential to reverse power imbalance and recalibrate equity.” CBPR affords researchers opportunities to build on the “strengths and resources of community members,” foregrounding their lived experiences by sharing knowledge with all participants and committing to partner communities for the long-term (Afifi et al., 2020, p. 382). In addition to conducting a detailed feasibility analysis before commencing research, scholars should carefully consider the risk-benefit ratio for potential research participants (Ford et al., 2009).

Fears of infection inform research participants' willingness to engage in research projects in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal decisions and public behaviors in pandemic settings are based on a variety of factors, including risk perception (for the individual or for their family's health), perceived severity of the disease, and perceived effectiveness of the suggested infection control strategies (Seale et al., 2012). Given this lace of obligation, researchers should prioritize communal health to embody a future anteriorized ethics. Scholars must serve as a bridge between various actors and influences, making active communication essential in terms of promoting safety measures. In addition to garnering consent from research participants, Smith et al. (2012) advocate for the need for proactive communication during pandemics. In high-risk situations, Marshall et al. (2008) also suggest problem-based learning for improving pandemic preparedness for emerging and senior ethical researchers. Consequently, a multitude of actors should support and offer guidance to researchers in situations of duress, including COVID-19.

Emerging literature on qualitative research during COVID-19

Hall et al. offer a literature review on participatory approaches during COVID to show how “distance-based participatory methods may be used in wider contexts where face-to-face interaction may not be appropriate, or fieldwork may be disrupted due to logistical reasons” (2021, p. 1). These methods include remote photovoice and interactive videoconferencing for photo and video diaries (Liegghio and Caragata, 2020), discussions that take place alongside interactive activities (e.g., knitting) during videoconferencing to counteract performative anxieties in the midst of virtual ethnography (Nelson, 2020), auto-ethnographies via engagement with social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook), cross-platform messaging applications (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger), and voice over IP services as platforms for debate, knowledge exchange, and participation (Jones, 2020). Others have also relied on distanced methods, using videoconferencing, telephone, email, WhatsApp, or epistolary exchanges to lead virtual or text-based interviews or focus groups (Dube, 2020; Hinkes, 2020; Strong et al., 2020; Woodward, 2020; Maycock, 2021). Notably, Nguyen et al. present an excellent case of conducting fieldwork remotely with the help of local research assistants, which they argue should be “embraced as a way of reimagining knowledge production” (Nguyen et al., 2022, p. 1). Overall, researchers stress the importance of “creative, sensitive and therapeutic methods” (Lazarte et al., 2020:3) by being mindful of access and inequality (Lourenco and Tasimi, 2020) while focusing on knowledge exchange and equal power relationships for successful projects conducted at a distance (Marzi, 2020).

Contribution and argument

Drawing from insights within the literature on qualitative methods in conflict settings and during the early stages of the COVID-19 global pandemic, we describe how lessons from toxic contamination research can inform research methods in the time of COVID. Fortun's (2003, 2011, 2021) interventions on toxic contamination are applicable to qualitative methods in the context of the novel coronavirus due to its time and space sensitivity. One major difference between toxic contamination and the COVID-19 pandemic is that viral coronavirus contamination arrives abruptly, requiring swift, global, and holistic changes to collective and individual practices. In contrast, toxic contamination moves more perniciously, such that harmful impacts can be slow to accumulate and manifest. Similar to insights from community-based participatory research (CBPR) and participatory action research (PAR) methods, we argue that we are embedded in geographical and social contexts that are constantly evolving over time. This situatedness invokes a lace of obligation to personal and communal health that extends into the future, as ultra-local viral situations and people's caution and willingness to abide by safety measures fluctuate.

In other words, literature on toxic contamination helps elaborate the complexity of this pandemic and situate participants and researchers as agents whose powerful acts will help safeguard—or exacerbate—communal health, namely by demarcating expressive and performative contamination. Viral contamination, like toxic contamination, is both expressive (i.e., a state of affairs we express or acknowledge) as well as performative insofar as it is produced through acts we do or do not commit (Fortun, 2011, p. 246–7). Because research in a global pandemic is similarly expressive as well as performative, researchers, in accordance with participants, must take sensible actions now in hopes of extricating our future from the present pandemic.

Given the presence and emergence of viral variants, we have had to experiment with methodologies and epistemologies rooted in open communication and inherent flexibility in order to adapt to the changing epidemiological situation as well as participants' availability and preferences in times of duress. Health is spectral, and participants' and researchers' bodies are open systems vulnerable to contamination (Fortun, 2011; Mokos, 2021). COVID-19, especially in its asymptomatic forms, is thus an important part of the context in which participants and researchers alike are entangled on the ground. How then, should qualitative scholars respond?

In the face of a mutating viral disease, we propose that qualitative research methods should remain open-ended to adapt to COVID-19's epidemiological evolution, finding ways to make this disease legible in research ethics, methods, and writing. While reshaping plans as projects unfold is hardly foreign to researchers, we promote the notion of processual research methodologies, wherein scholars become more virus-like themselves, adapting to ever-changing conditions and contingencies while finding openings for advancement, however miniscule, when and wherever possible. By drawing from our own experiences while bearing in mind our entangled web of moral responsibility, we explore the future anteriorized ethics and methodological landscape of this pandemic era, specifically addressing the following questions:

• How can qualitative researchers maintain a safe and ethical environment for conducting research?

• What data are we able to gather in the context of COVID-19, and what risks are we willing to assume?

• How do methodological adaptations favoring remote and virtual methods affect the power imbalances between participants and researchers?

Through targeted reflections on our processes of adaptation in research, we four early-career academics based in the West examine how scholars can perform relatedness, knowledge, reasonableness, and care in ways that are conscious of how researchers and participants are both contributing to expressive and performative contamination in the COVID-19 pandemic. While much of our work is not explicitly PAR, we draw inspiration from its broader aims and tenets, suggesting that a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach helps navigate the unpredictability and non-stable identities of bodies and viral contexts alike. In this paper, we offer a discussion of ethical and practical challenges to reorienting participatory research that we faced in the context of the pandemic, delving into how the various methods and research plan adaptations we mobilized were able—or not—to circumvent issues of power, vulnerability, or stigmatization and advocating for flexibility in research design to foster trust, build rapport, and engender feelings of safety.

Methodological panoramas: Community-based participatory (action) research and fermented landscapes

Participatory action research (PAR) can be described as a cycle of planning, acting, and observing (Walter, 2008). More of an approach than a method or technique with an exact procedure, PAR embodies the collaboration of an organized collective to set a research agenda, collect data, engage in critical analysis, and design actions to improve people's lives or effect change (Hale, 2001; Walter, 2008; Breitbart, 2010). PAR seeks to democratize research design by fully engaging those affected by the issue studied, promoting diversity, and sharing power to avoid exploitation (Breitbart, 2010).

PAR embraces an explicit value-laden approach that recognizes the essential worth of power sharing between the “observer” and the “observed” (Walter, 2008). This presents a learning opportunity for the collective of researchers and participants, which can uncover tensions, contradictions, and ethical dilemmas to improve research and social outcomes (Hale, 2001). In other words, PAR strives to create deeper, more thorough, and better situated empirical findings while co-producing knowledge and action (Hale, 2001).

Though our explicit commitment to PAR varies, we uniformly promote collaborative work as an adaptive approach to working with participants in times of uncertainty like COVID-19. Collaborative partnerships in community-based participatory research (CBPR) seek to balance unequal power relations through equitable community participation at each stage of research (Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Muhammad et al., 2015). In our projects, the inclusion of participants in research design differed along a continuum, but each moved beyond tokenistic engagement, with commitments to ethical consent, equitable and just data collection, as well as community capacity-building (Ibid., Parker et al., 2019). For instance, we engaged in pre-fieldwork dialogue as well as ongoing check-ins around participant schedules to allow “people to ask questions about commitments and to define their boundaries and make requests” (Mokos, 2021), notably with regard to COVID precautions. During such encounters, we aimed to follow Fortun's suggestion of turning doubts and concerns into resources, engaging with, rather than shunning “amendments, elaborations, and critical response” from participants (Fortun, 2003, p. 176). As we will discuss later, we were also open about the challenges we faced and our failures, which are not unique to our situations (Davies et al., 2021).

While researchers and participants alike face new difficulties when doing community-based participatory (action) research during COVID-19, transforming participants into collaborators was already a challenge in pre-pandemic times (Marcus and Fischer, 1986; Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). During a pandemic, participants may be juggling other personal commitments while working (or caring for relatives) and have varying technological capacities for online participation. Still, we can think of participants as “organic intellectuals,” who with qualitative researchers “are exploring the emergent new worlds about which they have a mutual curiosity” (Marcus and Fischer, 1986, p. xxv; Fortun, 2003, p. 181). To do so, we emphasize power sharing as a major defining factor in building effective academic-community collaborations and suggest that we as researchers and community partners should be reflexive about how research is conducted to “guard against appropriating knowledge, [and] to work toward negotiating co-learning and collaborative knowledge production” (Muhammad et al., 2015). By foregrounding how researchers and participants act and make decisions amidst uncertainty and by positioning participants as “collaborators in the production of critical analyses” (Marcus and Fischer, 1986; Fortun, 2003, p. 176, 181), power sharing is a way to account for the virus in our methods and subsequently in our writing. We acknowledge not all participants may be available to be involved in the co-management of the research project; collaborative partnerships designed around the participants' schedules and constraints may sometimes be more appropriate. Hence, instead of requiring full involvement of participants at each step, collaborative research integrates the participants' perspective in the knowledge production phase led by the researcher (Morrissette, 2013, p. 46).

Fermented landscapes

The topical framework of fermented landscapes, which Myles (2020, p. xix) defines as the “shifting patterns of land use and management as well as cultural changes related to the production and consumption of fermented beverages in a variety of contexts,” unites our work. Fermented landscapes is both a body of work and an approach to research that examines how fermentation—both literal and figurative—influences landscape change. These influences can be in terms of actual material or metabolic change(s) or can be more symbolic in terms of shifts in values, meanings, or perceptions. Foregrounding material-semiotic analysis, fermented landscapes research delves into the “macro consequences of micro(be) processes of socio-environmental transformation” (Myles, 2020). Each of the projects represented in this paper is situated within the Fermented Landscapes Lab at Texas State University, and we are linked by the mentorship of Dr. Colleen C. Myles, the originator of this conceptual frame.

Scholarship on fermented landscapes is characteristically field-based, constituting hands-on, face-to-face, visceral experiences with the people and places in question. The qualitative style typical of this body of work has previously highlighted topics ranging from the social dynamics of local kombucha culture (Yarbrough et al., 2020) to the actor-networks of English cider producers (Furness and Myles, 2020) to farm-to-bar chocolate agrotourism in Hawai'i (Galt, 2020). However, COVID-19 radically altered the feasibility and permissibility of doing this kind of work.

“Fieldwork without the field”: Navigating COVID-related challenges to qualitative research

What does fieldwork look like without the field? Scholars have pondered previously the distinctions and interrelations between “fieldwork” and “the field” (Katz, 1994), and the necessity of adapting research plans to local conditions is not new—whether related to political turmoil, environmental hazards, or other socio-environmental disruptions (Laborde et al., 2018). Yet the scope of present limitations merits further reflection, particularly as pandemic-related impacts continue to affect many research participants, even those in relatively-privileged positions.

The onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic harkened swift and sweeping restrictions on direct interactions with others. Following the lead of local, regional, and national governments, institutions of higher education imposed restrictions and modifications to research processes and fieldwork. The numerous challenges of moving research that has traditionally been carried out in-person, in the field into a virtual context require experimental adaptation. Many scholars, ourselves included, have had to put our research agendas on hold indefinitely or review the scope of our research designed in pre-pandemic times, revising plans and protocols so that our work could be conducted feasibly in the context of this “new normal.” Over 2 years into this pandemic, this reality continues to unfold.

As this paper details, core elements of our fieldwork have had to be altered, replaced, or abandoned due to the pandemic. The projects represented here were conceptualized prior to COVID-19 and required significant revision to their research methodologies to be viable. The reflexive accounts we share as researcher-practitioners and scholar-activists explore how researchers can adapt to and navigate the entangled geographies of qualitative research, risk, physical distancing, failure, participant-researcher relationships, and power imbalances. Given the constraints of an uneven global pandemic and our respective funding situations, we explore how, as early-career scholars, we felt pressured to be ambitious in our research, irrespective of global and local public health contexts. Next, we discuss challenges that arose in the context of taking research “out of the field.” We conclude with a critical reflection on ethics and principles for undertaking collaborative research in this “new normal” marked by persistent, public health crises.

Navigating the “new normal” as qualitative, fermentation geographers

Four projects are represented in this paper (Table 1). As these projects involved different questions, populations, data, and various stages of completion at the onset of the pandemic, our needs and responses also varied. In the following subsections, we reflect on the realities of doing “fieldwork without the field,” including challenges and opportunities linked to pivoting to remote/virtual methods and the modifications required for continued face-to-face approaches. In our research group, the increased prevalence of videoconferencing as a predominant mode of communication had an impact on our work, including the inclusion of geographically-distant partners. Relatedly, one positive outcome of COVID-19 has been greater empathy and mutual understanding for peers navigating a range of work-life responsibilities, including wrangling pets and children in non-traditional workspaces (Myles-Baltzly, 2022).

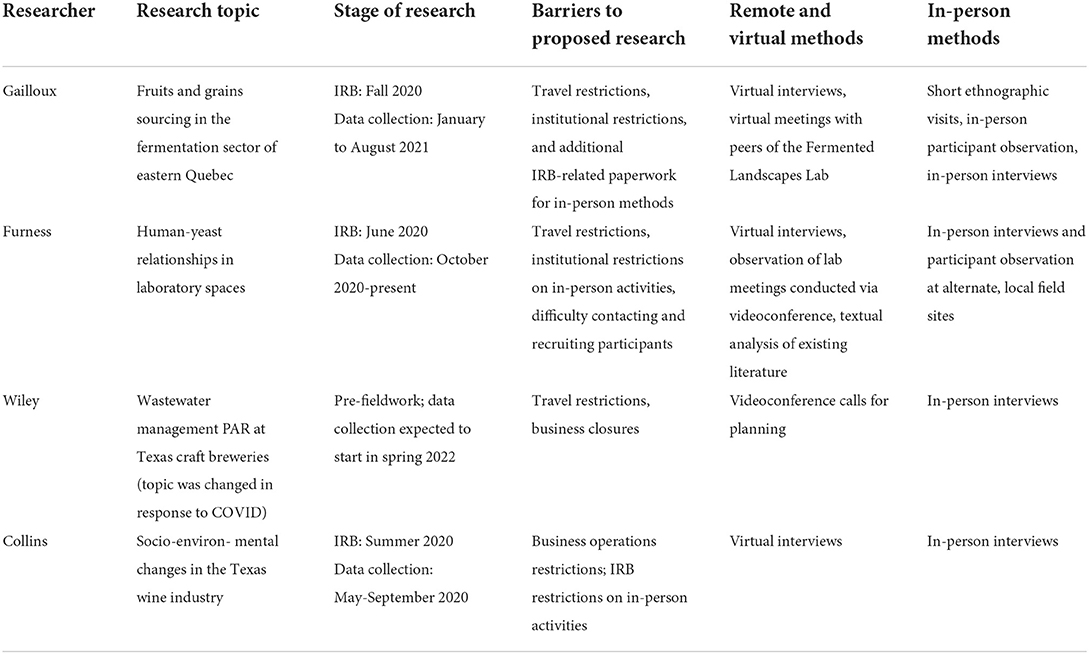

Table 1. Summary of research projects presented in this paper with barriers to proposed research and modifications adopted by each researcher.

Chantal Gailloux, a postdoctoral researcher, conducted an ethnographic project on fruit and grain sourcing in the fermentation sector of eastern Quebec, Canada. Planning her project in fall 2019, she initially aimed to conduct comparative research in Texas, California, and Quebec. Starting fieldwork in January 2021, she downsized the scope of her intended work in response to ongoing pandemic-related restrictions, canceling her plans for in-person fieldwork in the U.S. Committed to strict protocols and active communication with participants, she was able to conduct hybrid fieldwork in eastern Quebec (where she lives), both online and in-person when regional and provincial public health agencies granted the situation was negotiable. Given the contemporary context, participants were understandably distracted and ethnographic data collection was repeatedly interrupted, rapport had to be built differently than in pre-pandemic times, and Gailloux had to remain flexible to attend to her participants' needs and constraints and ethically maintain horizontal, collaborative partnerships.

Other lab members also had to adapt and reconfigure their research plans. Doctoral candidate Walter Furness modified his primary data collection strategy due to travel restrictions, turning toward more local interlocutors and secondary sources. In planning his fieldwork shortly before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Furness had relied on co-present sensory observations of yeast and scientists in laboratories along with semi-structured interviews to understand how synthetic biology technologies modulate yeast-human interactions. By necessity, his fieldwork, which was initiated in the midst of COVID-19, had to pivot away from his original approach when these highly-sanitary and controlled environments became unavailable due to quarantine and travel restrictions. With in-person interaction impossible, Furness has conducted interviews and observations via videoconference and turned toward secondary data, analyzing academic literature on synthetic yeast projects.

Delorean Wiley, another member of the Fermented Landscapes Lab who started her doctoral research design a couple of months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, changed topics and moved in the direction of a more community action-oriented project due to the constraints of the evolving situation. Initially, Wiley wanted to study how gender is represented at craft breweries across five states in the United States. Realizing the pandemic would last longer than anticipated and the travel required for her initial project would be challenging to undertake in the context of a public health crisis, Wiley jumped on a newfound opportunity. With the Wimberley Valley Watershed Alliance (WVWA)2, she now is working to improve wastewater management and sustainability initiatives in the Texas craft brewery sector by reinvigorating the Texas Brewshed Alliance (TBA) via a participatory action project.

Kourtney Collins remained committed to her community-based participatory thesis work throughout COVID-19. Though aided by her role as an insider to the wine industry (due to her employment) when the pandemic struck, the depth of her master's research arguably diminished due to COVID-19 restrictions. Collins made numerous adaptations to her project in response to her interviewees' constraints, as local, state, and federal mandates regarding capacity limits in tasting rooms, temporary shutdowns, and new regulations consumed winery owners' time and attention.

Results

Negotiating risk nearer to bodies in a virtual and in-person ethnography of fruits and grains as ferments

Relying on active communication with participants and enhanced safety measures, Chantal Gailloux was able to pursue her postdoctoral fieldwork online and in-person from winter to summer 2021, when allowed by Quebec's public health agency and the university's institutional review board (IRB). She set the threshold of permitted in-person research when her field sites and her home—the Gaspésie and Bas-Saint-Laurent regions—were not located in “red” areas (highest risk level) on the provincial public health agency's COVID-19 alert map. Still, her six-month community-based and participatory multi-sited ethnography (Marcus, 1995) was repeatedly interrupted with changing public health safety measures, requiring her to stay nimble and virus-like in order for her approach to remain safe, feasible, and ethical in the context of a shifting epidemiological situation.

Gailloux began her postdoctoral fellowship in fall 2020 with funding that ordinarily requires fellows to be on-site at the affiliated institution. Given the pandemic context, the funding agency allowed remote work, albeit with little guidance. Although the U.S.-Canada border was generally closed, it was theoretically open for students and workers. Nevertheless, Gailloux faced a quandary: What data would she dare gather in the context of COVID-19? To adapt, she downsized the scope of her study and abandoned the possibility of doing comparative fieldwork in three sites: Texas, California, and Quebec.

She decided to conduct fieldwork only in eastern Quebec with fruit and grain farmers, brewers, distillers, and other primary processors like maltsters in the Bas-Saint-Laurent and Gaspésie regions. Located north of Maine and the Canadian Maritime Provinces, eastern Quebec is a rural region with a small, aging population spread over a vast territory about the size of Switzerland. By narrowing the scope of her project and not moving to another country where she had anticipated conducting highly-mobile research, she reduced risk to herself and others considerably, acknowledging how her research laced her and participants with obligations because of potential viral contamination. Reframing the research project was thus her way of enacting a future anteriorized ethics.

Still, even this scaled-back research plan was contingent. She prepared additional paperwork3 (which unfortunately slowed the recruitment process and discouraged some participants) in fall 2020 and strict protocols to make sure she and her participants agreed upon and followed appropriate safety measures when meeting in person. To adapt to the epidemiological situation, Gailloux decided to follow Quebec's public health agency color-coded alert level map and did not visit places4 in the highest (red) alert level. After a summer of respite in 2020 with fewer cases, she hoped remote areas like eastern Quebec would fare better in 2021 and the red-alert level would be confined to urban areas, like Montreal. She was proven a bit too optimistic and had to adjust to varying caseloads over the following weeks, with eastern Quebec and the rest of the province remaining at high risk during fall 2020, returning to lower risk levels only in February–March 2021, then rising again with a surge of new variants. At the end of June 2021, safety measures were slowly loosening, since the province's vaccination rate (first dose for adults) was over 80 and 27% for two doses (CBC, 2021; INSPQ, 2021a,b). All regions of Quebec returned to lower alert levels in May and early June, re-enabling in-person research. Because of the ongoing epidemiological situation, she continually modified her plans and approaches to working with her interlocutors, embodying flexible and reflexive research design.

Gailloux realized she had to maintain active communication channels with participants to build rapport. She prioritized active communication, reaching out via phone in addition to email and ascertained which means of interaction participants preferred (e.g., in person, phone, videoconference, email, text). By consulting with participants about their fears, Gailloux was able to turn concerns into opportunities by sharing power (Fortun, 2012; Mokos, 2021) over the research design and forging a more ethically-grounded project.

Gailloux conducted 26 interviews, mostly via videoconference. Because participants were dispersed over a large territory with unequal technological savvy and access, holding group meetings to discuss the research design and interpretation of results was not feasible. In this case, she shared power through one-on-one conversations before, during, and after the data collection phase. Farmers, older people, or folks who either were keen to do the interview right away or sought the least cumbersome way to participate tended to prefer in-person or telephone interviews. Gailloux followed the recommendation that the “need to build trust over the phone is magnified, and interviewers should take time to establish rapport by explaining the project and data collection process to participants” while the “lack of face-to-face cues [could make] it problematic to ascertain if the questions are causing participants distress” (Ali et al., 2020; Mani and Barooah, 2020; Hall et al., 2021).

For instance, one dairy farmer whom Gailloux first contacted by phone and recruited through snowball sampling was uncomfortable with videoconference platforms. He seemed curious to meet the researcher and preferred in-person interaction. Living nearby, they met for an interview and a tour of his farm in March, respecting a six-foot distance and wearing masks. As Strong et al. (2020) note, some participants prefer face-to-face interactions and are reluctant to do online interviews; they advise that interviewers should do regular check-ins and remind participants that they are in control of the interview.

Gailloux's first 5-day ethnographic visit in early March was at a micro-distillery. While planning her visit over the phone, the manager admitted that his team of six workers had relaxed some safety measures because there were very few cases in the region at the time, but he guaranteed they would tighten them back with her visit. In addition to these planning calls, Gailloux briefly presented her project to the distillery staff during a lunch to discuss, answer questions, and distribute consent forms, reflecting her commitment to transparent, collaborative research design.

In the semi-industrial production context of the distillery, the three employees she worked alongside wore their face masks at all times. Office workers didn't wear them when she was not around, but would put them back on when speaking with her. Thus, the use of face masks was variable and depended on who was present. Despite initial reassurances that employees would follow restrictions at all times, the participants performed these measures variously according to the sociospatial context. Moreover, specific tasks made it difficult to respect safety measures at all times. For instance, lifting heavy loads with four hands made it difficult to maintain physical spacing of six feet. In addition to masks mediating interactions and concealing facial expressions, certain noisy activities like grinding barley for the mash tun further limited communication, as Gailloux could not read her coworkers' lips. Reflexively moving closer in order to listen, this potentially risked her coworkers' and her own safety. Overall, Gailloux felt it was difficult to respect all safety measures at all times and was not always sure how to react when others, especially company executives, failed to follow safety measures. These experiences underscored that despite acknowledging the epidemiological situation, researchers and participants do not always adhere to safety measures in rational or consistent ways, and bodily affect varies across microgeographies of research sites.

This became even truer as restrictions were gradually relaxed. Moving a few kilometers east within the same province, Gailloux saw how the viral situation—and people's responses to it—varied geographically, mirroring the varying risk perception that Seale et al. (2012) and Davis et al. (2015) described in relation to influenza. She realized that local risk perception and shifting safety measures were additional barriers to building rapport. For instance, when the brewer and owner of a microbrewery presented his arm for a handshake on the first day of a 1-week ethnographic visit, Gailloux felt uncomfortable at first but didn't want to undermine rapport with him and his crew. Thanks to pre-fieldwork conversations, she was aware that brewery employees had received their first shot, so she decided to reciprocate the gesture in a calculated risk, performing relatedness. Reasonableness and care in times of COVID are sometimes in tension with social norms and hospitality in pre-pandemic times.

Challenges to engaging participants and collaborating remotely in laboratory spaces

Furness had just begun to lay the groundwork for his fieldwork when the pandemic necessitated widespread closures in North America. Initially planning to physically spend time conducting interviews and observing researchers in a synthetic biology laboratory, the pandemic forced a change in these plans. The severity of COVID-19 in his desired field site in New York City led Furness to take his research online, relying on videoconferencing as a medium for accessing geographically and socially-distant spaces. With tenuous preexisting familiarity with his interlocutors and research context, he relied heavily on email to recruit participants, a tactic that had limited success. His initial approach struggled to gain traction, due to both the constant uncertainties faced by researcher and participants alike and the difficulties of building rapport through email alone.

Connecting to new field sites and interlocutors during normal times can be a challenge in itself, and Furness found this to be even more true in the context of virtual meetings. In December 2020, he began attending lab meetings of a New York City lab group via Zoom. Entering these milieux as an outsider and via webcam presented challenges to creating trust and familiarity with participants due to his relative anonymity and disconnection from the group. The structure of these meetings allows for questions and virtual interaction, but is not conducive to meeting new research partners and building rapport with strangers. Despite a brief introduction to the group at the end of an initial lab meeting and several one-on-one conversations over Zoom, Furness struggled to make lasting connections to the larger group, having never met any of them in person. As the pandemic unfolded, Furness worked to navigate persistent travel restrictions to his potential host institution in New York. Part of this uncertainty included the financial logistics of this work: awarded travel funds from Texas State University, he was unable to use them due to institutional barriers and worked to obtain extensions for their use, eventually pivoting toward using the funds to travel to a different site.

However, the virtual modality he gravitated toward also opened new portals for interaction, even from afar. In the early stages of the pandemic, obligations to maintain safety required all meetings to be held virtually anyway. Since lab members based in New York were also meeting remotely from their residences or individual workstations, the pandemic flattened space in a way, creating a cumbersome but more-or-less level plane in which each person had relatively-equal access to the sessions, regardless of their physical location. Furness' project was not designed to foreground PAR, but delays in its implementation created openings for participants to shape its trajectory to become more collaborative and participatory as it slowly unfolded in the midst of COVID. However, lack of participant buy-in was a continuous challenge to this project.

In late May 2021, as mask mandates began to lift in the United States in accordance with changing public health guidance, the NYC lab meetings also changed in structure. Lab members (all vaccinated) began meeting in a hybrid format, with a smaller group of eight scientists at first, then 13 in a conference room with little distance and few masks (though pausing their habit of bringing food into meetings), while the remaining dozen members continued to join meetings remotely. Smart cameras and microphones in the conference room facilitated this transition. Those joining virtually have noted reduced audio quality occasionally, especially when multiple people in the conference room speak simultaneously. In this way, microphones have mediated and limited online participants in favor of fully capturing what is happening in the conference room, adding to other technological glitches that punctuate our virtual lives, whether problems accessing an account, sharing a screen, or an unstable Wi-Fi connection. Technology has not only enabled participation; it also has created separation between those participating in person and those joining remotely. Even a high-speed internet connection is not necessarily enough to bridge this divide, since visual cues like body language are less accessible to virtual participants due to fixed camera angles (Pocock et al., 2021).

A result of these virtual and hybrid lab meetings is that the duration of Furness' involvement with this group extended far beyond his initially-proposed timeline, while the quality of the interactions made it difficult to answer his research questions at all. What he had hoped would be intensive, in-person interaction evolved into much more partial, impersonal observations of Zoom rooms. During the meetings (which are primarily research presentations of lab members' current work), most participants remain muted and off-camera throughout, though interjections and questions are not uncommon (Figure 1). This type of setting allows access to many people at once (through direct chat messages, for example), but insulates participants from more visceral, embodied connections and allows them to simply ignore messages if desired. This ease of opting out has the ethical upside of shrinking perceived power differences between researcher and participant (Newman et al., 2021), but made recruitment challenging. As the potential depth of engagement with the social context of these meetings has been diminished, more casual conversations and observations have been rendered unwieldy. This transition from shorter, more in-depth work to “shallower,” longer-term participation is one of a number of challenging COVID-required adaptations resulting from obligations to safety and responsible research. Notably, these adaptations may have negative, positive, and mixed effects.

Figure 1. Screenshot from a lab meeting held over Zoom, in which Furness participated (image blurred to protect participants' privacy). Note the participant list on the right-hand side of the image (highlighted in yellow), which shows how nearly all attendees kept their cameras off. This dynamic is the norm, except during brief goodbyes at the end of meetings.

Flexibility has been paramount in this project, but timelines have limits and Furness has struggled to progress through seemingly-indefinite delays. Though accommodating setbacks to his fieldwork demonstrated this flexibility, an initial lack of adaptability in 2020 contributed to his decision to stick with his proposed research design instead of immediately abandoning it for more feasible methods. While the ongoing pandemic highlights the importance of key aspects of collaborative research like attentiveness and sensitivity, Furness found that relying on an epistemology that acknowledges affective complexities and sees interviews as emplaced (neither discrete nor disembodied) creates challenges to building rich, shared meaning in the context of virtual participation. As a result, he broadened his initial research plans to include more video interviews, in-person observation with field sites in Texas, and textual analysis of academic literature. Taking cues from Fortun (2012), he developed more creative, participatory approaches like collaborative mapping that may create space for new encounters to emerge. This attempt to navigate discrepancies between project ideals and realities with an emphasis on flexibility is a way of enacting a future anteriorized ethics despite unforeseen limitations.

Changing the research project altogether to reduce risk and embody a future anteriorized ethics

For some, the enduring nature of this global pandemic proved that modification alone would not suffice; an entirely new project needed to be developed. Delorean Wiley was in her first year of doctoral study when COVID-19 suspended in-person research. As 2020 turned to 2021, research travel continued to be restricted and vaccines were not yet widely available; an end to the pandemic looked distant. Weighing what Ford et al. (2009) call the harm-benefit ratio, Wiley decided her original plan—traveling to several states over an extended timeframe—would not be safe for her or potential research participants. Her choice to scale down the scope of her study area to Texas alone increased safety and reduced uncertainty about her ability to collect data, creating a future anteriorized ethic aimed at preventing further or unnecessary contamination.

Wiley's experience is illustrative of how viral contamination is performative. She contracted COVID-19 during Texas' third wave, despite being vaccinated. With recently-acquired antibodies through vaccination and contamination, her personal risk while teaching and collecting data shrank, at least for a time. However, to perform relatedness and care, Wiley chose to continue to wear a mask during pre-fieldwork meetings when social distancing was not possible.

Contamination risk as expressed by governments and public health agencies substantially diminished breweries' ability to serve as spaces for data collection and research. For ~6 months in 2020, a Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission (TABC) mandate forced breweries to quickly transform their operations by offering food under a temporary license in order to continue operating. Some were unable to do so and temporarily closed. Others closed indefinitely because they could not recoup the lost revenue. Wiley realized it would be impossible to collect the data needed to complete her original dissertation project, changing her research focus and the scope of her study area. In March 2021, Texas governor Greg Abbott's executive order preventing the closure of businesses due to COVID-19 eliminated the uncertainty of breweries being open for business, though many questions regarding contamination and the permissibility of research remained. Planning in this situation involved balancing precautions that limited risk of viral contamination while allowing participants agency and flexibility. The ethos Wiley espoused echoes Mackenzie et al.'s (2007) conduct of research with refugees: respect for persons, autonomy, and justice.

Planning collaboratively for the research to be conducted, the Wimberley Valley Watershed Alliance (WVWA) and the Fermented Landscapes Lab decided the risk of meeting face-to-face was worthwhile, gathering on a brisk and sunny afternoon in spring 2021 at a Texas Brewshed Alliance (TBA) member brewery. To guard against infection, the meeting occurred outside, participants wore masks, and sat spaced apart (although not a full six feet apart, as a greater physical distance between participants would have made dialogue difficult). During the meeting, participants from WVWA revealed they were reading the Fermented Landscapes edited volume (Myles, 2020), signaling a desire to learn more about our lab's work, which helped build rapport within the group. Additionally, WVWA members shared their vision for TBA, helping to cement the research team's mutual goals and commitments.

After a year of lost sales, the newly-formed group concurred that economics would be a key driver for breweries in 2021–2022. The collaborators agreed that hosting a TBA re-launch event could help bring the local craft beer community together and raise awareness of the TBA's mission. While researcher requests for business data could be viewed as insensitive or even inappropriate (evocative of research in conflict settings, which highlights how the provision of basic needs takes priority over research needs) (Leaning, 2001; Afifi et al., 2020), coordinating an event to generate sales for participants could signal the research group's genuine desire to help member breweries and not just use them extractively as research sites. Whether the event will be held virtually or in-person is dependent on future COVID-19 cases in the area, once again reminding us of the need to be flexible and creative, planning and adapting our fieldwork in response to an uncertain future.

Managing work-research divisions and respecting participants' unavailability

Much like breweries, wine and tourism industries were severely affected by the pandemic; businesses and revenues faltered as consumers were unable to visit closed tasting rooms. As mentioned previously, the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission decided to take action to help minimize transmission, shutting down establishments in March 2020 unless they could legally operate as a restaurant. Winery owners were forced to alter operations quickly to reopen and generate onsite revenue. Many were forced to lay off staff and work with skeleton crews, adding to workers' burdens. In July 2020, Texas governor Greg Abbott signed an executive order (GA-28) that allowed restaurants to open at 50% capacity and stated that any winery or bar that had a commercial kitchen with food sales above 51% of total sales could also open doors to the public at 50% capacity. Because of this new rule, many wineries decided to add restaurant operations on top of their existing winery operations, which quickly snowballed into an overwhelming collection of now-essential side projects in order to obtain necessary permits. Learning how to operate a tasting room and training staff to accommodate visitors in a COVID-safe manner was a challenge, especially in the middle of harvest season.

Master's student Kourtney Collins set out to examine the environmental and cultural context of the quickly-growing wine industry in Texas from the point of view of vineyard and winery owners and operators. However, when she started her community-based participatory fieldwork in the Texas wine sector in May 2020, just months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the midst of social distancing and other public health restrictions, she faced several challenges to accessing the field despite being directly employed in the industry she studied.

As an essential worker, Collins was already exposing herself to risk and conducting interviews while in the office did not seem appropriate, at least insofar as it extended the risks of contamination faced by her potential interviewees. Even though key informant interviews were an essential element of her research plan, the most ethical path forward—as revealed both by critical reflection and institutional review board (IRB) guidelines—was to avoid or eliminate face-to-face contact as much as possible. The socio-environmental context suggested that it was not the time to dare to gather data in-person, especially since participants were less available due to work and personal stressors.

Thus, Collins had to find a way to conduct fieldwork without proper access to her field. She conducted interviews via videoconference, which imparted and necessitated a significant amount of flexibility. The use of virtual methods made the interviews more accessible to the overworked study population, but they were also largely impractical, given that both researcher and participants were working in agriculture, an occupation with working hours that are driven by varying, seasonal tasks. Scheduled interviews were often missed and then rescheduled, sometimes repeatedly, to accommodate the inherently challenging nature of participating in virtual interviews while working in the vineyard during harvest season. Participating in a research project, or co-managing it, requires time and energy that participants in times of crisis and uncertainty may not have (Teti et al., 2021); being sensitive to this issue as researchers is part of an ethical relationship in which participants and researchers share power and foreground flexibility.

Since the Texas commercial wine industry is relatively new, many interviewees were selected for their ability to provide perspectives on how the industry had changed in the preceding decade or so. Many of the participants were older, not especially technologically savvy, and located in rural, agricultural areas with unreliable internet access. As such, there were a number of obstacles to the virtual interviews (Whitacre and Mills, 2007). For instance, given the pandemic context, participants had to focus on more tasks than normal and had limited time to participate. In addition, the use of technology to connect with participants made it difficult to build rapport, leading to a nagging sense that participants could not be authentic in their responses. Although the use of virtual methods proved to be largely dissatisfactory, Collins tried to make the best of the situation because in-person techniques were neither safe, feasible, nor ethical at the time.

While Collins was not able to gather data of the quality (or quantity) that she hoped to, she ultimately completed the thesis work. The project could have been more intensive or extensive had the circumstances been less challenging. Nevertheless, by enacting caution and respect, Collins' restraint was an ethical act, performing the prevention of contamination even to the detriment of the data. Echoing Teti et al. (2021), her sensitivity to the obtrusiveness of virtual methods for certain populations acknowledged how building trust and relationships is key to CBPR methods and how CBPR is often compromised in pandemic times by necessary social distancing.

Together, these anecdotes point to the risks and difficulties of adjusting to the pandemic in contexts where bodies and sensations are highly mobile and safety is uncertain. The omnipresence of face masks and other necessary modifications to in-person interactions—as well as near-constant COVID-related stress and anxiety—mediate and transform rapport with interlocutors, adding layers of complexity to fieldwork. As previously mentioned, many of these obstacles are not new to researchers, but the inescapability of such challenges during a global pandemic suggests the need to reflect further on our methodological foundations, commitments, and responses.

Discussion

Each of us struggled with the pandemic-driven gaps between our initial, idealized research and the work that actually took place. While CBPR and PAR suggest participant-oriented frameworks that can adapt to challenging situations like these, our experiences resonate with a sustained need for more discussion of the difficulties, surprises, compromises, and readjustments endemic to COVID-era qualitative research. Thus, we found theoretical approaches highlighted by Fortun and others useful in contextualizing the current situation and gesturing toward possible ways forward. The processual methods presented here are rooted in a future anteriorized ethics, which centers the complexity of COVID-19 circumstances across time and space and helps situate participants and researchers as agentive actors whose powerful expressive and performative acts will help safeguard—or jeopardize—communal health. Our methodological contribution coalesces around three key findings: the need to address the uneven effects of COVID-19, how researchers should foreground flexibility and care in building rapport and designing their projects in times of uncertainty like pandemics, and how they should accept failures and limitations as part of research.

The need for care in an uneven pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had uneven social and geographic effects on and due to participants' habitus, health situations, and personal positionalities. Stemming from their class, education, and racial backgrounds, “these positionalities have the potential to reproduce systemic health inequities and disadvantage community partners” (Bourassa et al., 2010). At the same time, “racism and capitalism mutually construct harmful social conditions that fundamentally shape COVID-19 disease inequities,” as well as access to medical knowledge and freedom, which minimize risks and consequences of diseases and ultimately “replicate historical patterns of inequities within pandemics,” as Pirtle (2020) notes. Since scholars often “represent centers of power, privilege, and status within their formal institutions, as well as within the production of scientific knowledge itself” (Muhammad et al., 2015), they may be less sensitive to equitable outcomes. Since COVID-19 is individually felt and experienced differently across socioeconomic strata, researchers in this time must redouble their efforts to minimize harm and maximize benefits for individuals and the greater community.

Our acknowledgment of the mutual obligation between researchers and participants to prevent contamination and harm in this uneven pandemic impels innovative ways to stage encounters without excessive risk and without amplifying stressful circumstances. Since regions and countries have differing capacities to roll out vaccines, varying access to (affordable) health care, and local health systems may already be strained by other viral or chronic diseases, we are ultimately entangled with a mutating virus, and future public health is dependent on individual and communal health worldwide. Community-based participatory (action) research that seeks to foreground virality and participants' agency in research projects is important to preventing, or not further exacerbating, the slow violence of the pandemic through the workings of the academy.

In the context of a pandemic, the CBP(A)R-influenced methods we enacted seek the co-production of knowledge and equitable benefits by sharing power, considering participants as experts in their own interests while acknowledging the need for public health directives. Our hybridized approaches did not necessarily mean involving participants all the time, at all stages, as PAR often requires, but rather promoting frequent and open communication with participants to share power, discuss/mitigate risks, and build reciprocity/mutuality. For instance, an online PAR approach with farmers in Collins' and Gailloux's projects would have been inadequate and insensitive to the participants' context and ease with technology in the midst of the pandemic.

Building rapport and flexibility during COVID

While the ideals and tenets of PAR and CBPR are more important than ever in the context of public health crises, the practicalities of implementing these approaches may remain prohibitive. As our (and so many others') experiences illustrate, the deep engagement required for collaborative research is difficult in the context of COVID. Researchers should be virus-like in adapting projects to evolving contexts, whether that involves changing projects entirely, modifying data collection methods or field sites, or building more space into timelines for accommodating delays. They should be aware of intersections and idiosyncrasies between public expressions of contamination through decrees and mandated safety measures and how researchers and participants express and perform it personally through their individual actions, as Gailloux found in farms and distilleries in eastern Quebec.

Open-ended and creative methodologies hinge on a practice of iterative adaptation and solicitude to revalidate consent and remain methodologically flexible (Mokos, 2021). In other words, researchers need to be both reactive and proactive during times of radical uncertainty and risk. To ensure researcher and participant safety, we executed rigorous IRB-mandated consent processes and followed mandated protocols related to the use of personal protective equipment and social distancing practices. By ensuring safety measures are understood and accepted before a meeting ensues and by checking in frequently with participants, researchers can proactively address doubts and concerns. This process of frequent check-ins ultimately fosters relatedness, care, and trust (Strong et al., 2020), helping to turn participants into collaborators (Fortun, 2003).

Though contact was difficult due to infection risk, we were proactive in the ways we connected with participants and emphasized sensitivity to their communication preferences, generally meeting them “where they were.” For example, Furness modulated his interview modalities from his idealized in-person conversations to video calls to asynchronous email conversations depending on participants' comfort and availability. Likewise, Collins shifted her approach and frequently rescheduled interviews out of respect for participants' health and time constraints. These adaptations served to build rapport and flexibility even as they necessitated changes to project design and timelines.

While local authorities expressed contamination differently in Wiley and Gailloux's field sites, both researchers responded with culturally-appropriate conduct to prevent contamination. Flexibility was paramount in their projects: although they worked with the same IRB's standard operating procedures (SOP) in times of a global pandemic, Wiley offered more agency to participants in using (or not) safety measures, while Gailloux followed the strict government color-coded alert map and mask mandates. This variance stemmed from the different cultural landscapes and norms of Texas and Quebec and accounted for participants' differing expectations and comfort with social contact and infection risk. Despite prescribed safety measures, in the midst of action, researchers and participants alike may negotiate their performative interactions in spontaneous and not always rational ways (Mokos, 2021), like shaking hands.

The negotiation of risk necessarily evolves as the virus appears less harmful and, thus, becomes less apparent. As health and safety norms and regulations shift and expire, so do personal preferences for interpersonal interactions, which can lead to hazy or even conflicting cues regarding what is ethically or socially acceptable behavior, especially as we move geographically. This interplay between safety measures and evolving virality creates the complex field in which we conduct and negotiate research. As Derrida (1987, p. 327) suggests, context is constituted through the very interplay of opposites, for instance in varying attitudes and reactions to COVID in the midst of and in-between viral waves. Yet he also notes that to be hospitable, one has to “have the power to host” and exercise control over the event while also giving up mastery and ownership to let the other in Derrida and Dufourmantelle (2000). In the context of the pandemic (as in other conflict settings), research comes second to health risks or even stress and emotional burdens (Ford et al., 2009). Hence, the ethical limits of fieldwork are bounded with an acknowledgment of the need to stage generative encounters strategically.

Accepting failure as part of research

As Davies et al. (2021) note, failure is an intrinsic part of research. The COVID-19 context diminished the quality and quantity of the data we were able to or dared to collect, one of many forms of failure we have had to accept and acknowledge. More generally, Horton (2020) proposes six dominant forms of failure in academia:

(i) things not going to plan; (ii) pervasive anxieties about performance within the neoliberal academy; (iii) regret, or wanting to do more; (iv) embodied sense of personal inadequacy and (not)belonging; (v) assessment criteria and procedures; and lastly (vi) a toxic triumphalism that can pervade less critical discussions of failure.

We faced many of these kinds of failure in our projects, as we outline in the results section. As fledgling scholars, we felt especially vulnerable to performance anxieties, regret, and inadequacy, which had implications for our physical and emotional well-being (Butler-Rees and Robinson, 2020; Davies et al., 2021; Lorne, 2021). While striving to remain flexible, we were constrained by limited funding and time, which required each of us to grapple with unforeseen realities.

Barriers to access (to resources, interlocutors, or both) created challenges to completing our projects. While virtual interactions are freeing in some sense, they can also untether sociability in dynamic and unpredictable ways. On one hand, the structured, formalized, audiovisual context wherein participants must be invited, wield an audio and video-ready device, and have internet access makes casual interactions harder to replicate, as Collins and Furness highlight. Participants are constrained by the necessity of only one person speaking at a time, and non-verbal cues can be difficult or impossible to read (Fauville et al., 2021). On the other hand, such technologies may exacerbate issues of inequality in access and connectivity, as software and broadband internet are unevenly distributed across communities and geographic locales (Whitacre and Mills, 2007; Lourenco and Tasimi, 2020; Van Dijk, 2020). Thus, the decision to hold remote, virtual events can impose burdens on or even exclude participants with modest economic means, located in rural regions, or in areas outside the Global North.

Even for more privileged individuals (ourselves included), access to some university resources has been limited (e.g., books!), and researchers—like other workers—have had to depend more on personal computers and utilities while adapting their living spaces into offices. Such spaces are readily available for some, but others have had to make do with limited or shared spaces. Competition for internet bandwidth and quiet-enough rooms for videoconferencing at home has become a very real consideration for many.

In the “Zoom era,” participants can seem less focused or have reduced attention spans during meetings, as many are multitasking to provide care for children attending school virtually. Others may have their cameras turned off, lending a sense of disconnectedness to a meeting. All of this makes it harder to observe and jointly build meaning. In the context of our projects, virtual participation created challenges to co-producing rich and embodied data through an epistemology acknowledging affective complexities by seeing interviews as emplaced, as Furness notes.

There is likely an even greater need for feasibility analyses before conducting research now, and junior and senior researchers may benefit from appropriate training to increase knowledge of bioevent preparedness (Carrie et al., 2008; Ford et al., 2009). Moreover, along with researchers, a multitude of actors—from funding agencies to institutional research boards to journal editors and more—are responsible for ethical shortcomings and should “play a more proactive role for enhancing the practice of ethical research conduct” (Makhoul et al., 2018). Supervisors and mentors can play a significant role here.

While modifications to research plans and delays may be seen as failure, we suggest they are also opportunities for creativity. Turner (2020, p. 5) argues that we may find “power in failure” by being creative with how we engage with the quotidian processes of neoliberal, academic life and “push back against the fear and loneliness that ‘failure' can create.” Opportunities to effectively “teleport” between locations is one benefit of virtual interactions. Space is compressed and warped by satellites, allowing us to attend conferences, lab meetings, and interviews, regardless of distance or time zone. For instance, participants and researchers with caregiving responsibilities or non-traditional circumstances have been able to connect to peers and interlocutors in new ways as in-absentia or virtual forms of meeting and communication become mainstream. Since nearly anyone can join from anywhere—assuming they have the required equipment and connectivity—such interactions may increase fluidity and inclusiveness. The often-rigid boundary between personal and professional lives has softened, increasing awareness and acceptance of the various responsibilities people are juggling at work and at home, hopefully normalizing more empathetic and authentic interactions for everyone involved (Motherscholar Collective et al., 2021). These realities will likely shape our expectations and experiences of research going forward, meaning that failure and success may intermingle and overlap ever-more visibly.

Conclusion

With the interplay of variants, contamination, and vaccines, COVID-19 may not disappear, but shift from being a pandemic to be(com)ing endemic, a seasonal disease potentially less potent for the fully vaccinated (Xue, 2021). Qualitative researchers need to practice solicitude with and for participants while being attentive to the shifting preferences of all parties in terms of risk tolerance and individuals' capacity to participate in various ways as the epidemiological situation evolves. Decisions based on risk perception (i.e., severity or transmissibility) intersect with age, race, and gender differences and daily constraints, enabling or limiting the performance and prevention of contamination. A long-term commitment to ethical research and reciprocity is needed.

Whether conducted at home or abroad, travel and interpersonal encounters will almost certainly involve interactions with an array of unknowns as the uneven landscape of COVID-19 remains unpredictable. Attentiveness to how authorities express contamination and culturally-appropriate responses while remaining sensitive to participants' and researchers' specific needs and limits is an imperfect yet important starting point to assess the feasibility of research across diverse, viral contexts and geographic locations. Overall, precautions like opening dialogue before meeting or making the virus legible by talking about its perception and accompanying safety measures help stake out common ground (or intertextuality), ultimately sharing power. COVID-19's presence and gravity, continually performed through acts we do or do not commit (Butler, 1990; Fortun, 2011) and expressed variably in local contexts, is experienced individually and communally. We can help foster trust and build rapport with participants through open communication and flexible research design, adapting to participants' availability and preferences as well as the changing local epidemiological situation(s).

Through vignettes from our individual research projects, this paper highlights the challenges of progressively adapting research and navigating COVID-related barriers virtually and in-person. As previously routine elements of qualitative research became more problematic, we have had to respond by developing processual, flexible, and creative approaches in perpetual adaptation to changing viral circumstances. Based on methods and conceptual frameworks inspired by ethnographies of toxic contamination (Fortun, 2003, 2011, 2012), work in conflict settings and early stages of COVID-19, community-based participatory (action) research (Walter, 2008; Afifi et al., 2020), and fermented landscapes (Myles, 2020), we assess how we adapted to the contingencies of COVID-19. Given the tenuousness of the present, we suggest qualitative scholars should continuously reflect on their individual commitments while learning from others to embody a future anteriorized ethics.

Reflecting on what data we were able to and dared to gather while maintaining a safe and ethical environment for conducting research, we also contemplate stresses (despite our relatively-privileged positionalities), including testing the limits of bodily risk posed by COVID to emerging scholars under pressure to pursue ambitious research over short timelines. Our approach suggests an acknowledgment of our obligations to ourselves and to our research partners in order to reduce risk. We conclude that, in order to effect a future anteriorized ethic, scholars must turn doubts and concerns into opportunities by engaging with them directly during fieldwork to ultimately transform participants into collaborators in spaces of uncertainty.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Texas State University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CG, WF, CM, and DW contributed to the conception of the study. CG wrote the theoretical section. CG, DW, and CM wrote the methods. CG, WF, DW, and KC contributed empirical reflections from their research projects. WF and CG led the writing of the findings section and CM and CG led the writing of the discussion section, but all authors contributed and participated in the writing of these sections. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions and approved the submitted version.

Funding

CG received funding for a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Société et Culture (FRQSC) (Award Application No. 286009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Painting a scene evocative of COVID-19 variants, Fortun (2011, p. 237–8) writes: “Toxics also change, refusing stable identity.” Toxics are also embedded in and attached to other agents, similar to the pesticide cocktail effect: “They [toxics] change as conditions change, often creating byproducts through interaction with elements in new contexts. Their “fate,” as exposure scientists refer to it, is hardly straightforward” (Fortun, 2011, p. 238).

2. ^The opportunity emerged when Katherine Sturdivant—a master's student in the Fermented Landscapes Lab—discussed the Texas Brewshed Alliance (TBA) initiative, a water conservation initiative among Texas craft breweries, with the director of WVWA during a work event. Sturdivant suggested Wiley would be a prime candidate to help WVWA relaunch the TBA.

3. ^For research ethics approval with Texas State University's Institutional Review Board (IRB): three letters of consent, approval of safety measures, and acceptance of on-site research activities.

4. ^The unit of this map is the subregion area called “regional county municipalities”.

References

Afifi, R. A., Abdulrahim, S., Betancourt, T., Btedinni, D., Berent, J., Dellos, L., et al. (2020). Implementing community-based participatory research with communities affected by humanitarian crises: the potential to recalibrate equity and power in vulnerable contexts. Am. J. Community Psychol. 66, 381–391. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12453

Ali, Z., Azlor, L., Fletcher, E., Josephat, J., and Salisbury, T. (2020). Remote Surveying During COVID-19. Buckinghamshire: EDI Global.

Bourassa, B., Leclerc, C., and Fournier, G. (2010). Une recherche collaborative en contexte d'entreprise d'insertion: de l'idéal au possible. Recherches Qual. 29, 140–164. doi: 10.7202/1085137ar

Breitbart, M. M. (2010). “Participatory research methods,” in Key Methods in Geography, eds N. Clifford, M. Cope, T. Gillespie, and S. French (London: Sage), 141–156.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Butler-Rees, A., and Robinson, A. (2020). Encountering precarity, uncertainty and everyday anxiety as part of the postgraduate research journey. Emot. Space Soc. 37, 100743. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100743

Carrie, S., Marshall, S. Y., and Inada, M. K. (2008). Using problem-based learning for pandemic preparedness. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 24, s39–s45. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70093-7

Charania, N. A., and Tsuji, L. J. S. (2012). A community-based participatory approach and engagement process creates culturally appropriate and community informed pandemic plans after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: remote and isolated First Nations communities of sub-arctic Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 12, 268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-268