94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 04 January 2023

Sec. Climate-Smart Food Systems

Volume 6 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1033152

This article is part of the Research TopicEquity and Trade-Offs in Agriculture and Food System TransformationView all 8 articles

Introduction: From 2018 to 2022, the Koronivia Joint Working Group on Agriculture (KJWA) was the key forum for debating global agricultural change and integrating agricultural transformation priorities into the mechanisms of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). As a forerunner to the landmark decision at COP27 to initiate the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation of Climate Action on Agriculture and Food Security, it provided an opportunity to further the (as yet underdeveloped) discourse around social transformation and just transformation in agriculture. At the conclusion of this 4 year process, we ask: to what extent and in what ways has a just agricultural transformation been envisioned within the Koronivia Joint Working Group on Agriculture and what are the implications for the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation?

Methods: The paper presents a textual analysis of 155 written submissions, workshops, and concluding statements from across the full programme of KJWA workshops, meetings, and consultations.

Results: We find that references to just transformations in agriculture within KJWA are largely implicit, but not absent. We argue that justice has been most obvious and evident when it comes to discussion about who is (and where are) the most vulnerable to climate change and variability, and how access to climate smart technologies and information is distributed. Less evident have been discussions about just representation in the governance and visioning of agricultural transformation, and there have been few explicit appeals to address the historical injustices that have shaped agricultural and rural livelihoods in the Global South.

Discussion: We argue that following its conclusion, there is a danger that the outcomes of KJWA become reduced to a focus on the scaling up of a techno-centric vision of agricultural transformation. To counter this, there is need for ongoing dialogue to develop a shared and more complete understanding of justice that should be central to how agricultural transformation is integrated into the UNFCCC. We highlight some recommendations of how a justice agenda could be taken forward under the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation.

“The discussions about agriculture in the climate change context have long focused on massification and technological approaches to increasing unsustainable food production with insufficient consideration of how inequality shapes access to land and other resources needed for productive healthy sustainable and resilient livelihoods particularly for women and how climate change will exacerbate the existing unequal access to adequate nutritious food for all.”

[Quotation from Representative of Women and Gender Constituency, Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture Workshop on improved livestock, November 2020].

The above quotation comes from a statement made by Women and Gender Constituency at the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture's (KJWA) Workshop on improved livestock held in November 2020. It outlines an important gap in the way that agricultural change has predominantly been framed and discussed within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and petitions for new attention to be paid to bringing about a just transformation in agricultural and food systems, in the context of climate change. The interrelationships between agriculture and climate change mean that there is an increasingly urgent focus on agricultural transformation both as a means to meeting emissions reduction targets, and to adapting to climate variability and change. The Koronivia Joint Working Group on Agriculture (KJWA) was established at the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) 23, with a purpose and mandate to integrate agricultural transformation more fully into the UNFCCC, and in the commitments and actions taken by UN member states under the Paris Agreement.

The imperative to transform our environmental, economic and social systems has become increasingly popular discourse in international development contexts. Arguably the catalyst for this has been the United Nations' (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have mainstreamed the idea that fundamental and global change is needed if we are to achieve a vision of sustainability globally. This transformation discourse has been equally reflected in the UN Food Systems Summit process (UNFSS), which was oriented around the vision of “transforming the way the world produces, consumes and thinks about food” (UNFSS, 2021, p. 1), and in the UNFCCC itself, which states that “the implementation of the Paris Agreement requires economic and social transformation” (UNFCCC, n.d.). In this paper, we adopt a broad perspective on transformation, understanding it as “fundamental change in circumstance occurring to, for and by people within agriculture and food systems” (Whitfield et al., 2021, p. 383). We do so to allow alternative language and concepts (such as transitions, adaptations, incremental changes) to fall within the scope of our analysis (Hölscher et al., 2018).

Across the UN genre of “transformation” in particular there is an inherent message of systemic change and this is not void of recognition of the need for equity and justice to be central (von Braun et al., 2021) at least at a rhetorical level. However, beyond this surface level discourse, it is clear that the transformation called for in the UNFSS is not the same kind of radical structural change that is being campaigned for within political social movements, such as Fridays for Future or within agroecology and peasant movements such as La Via Campesina. Such movements have a stronger and inherent focus on seeing changes in political and economic structures that can bring about social justice and equity.

Blythe et al. (2018) argues that mainstream transformation discourse pays insufficient attention to politics and power. An imperative to transform has the potential to come at the cost of recognizing that radical change is often brought about through exclusionary processes, with inequitable outcomes (Nightingale, 2017). In describing low-carbon energy transitions, for example, Jasanoff (2018) highlights the socially differentiated consequences of low carbon pathways and differentiated participation in planning and policy processes, which act to exacerbate rather than alleviate energy poverty. When compared with the energy sector, the concept of a just transformation in agriculture comes with some added complexities owing to the reality that producers are also themselves consumers and are themselves amongst the most vulnerable to climate change impacts (Bezner Kerr et al., 2022). This is particularly true of small scale rain fed agricultural production systems and family farms, which in turn contribute least to greenhouse gas emissions.

Unless agriculture and food systems transformation redresses pre-existing inequalities, it will likely favor the most powerful stakeholders, and deepen existing inequalities and social injustices. If attention is not paid to the politics of such change, we may fail to recognize that it is those with the least political voice and power that most commonly lose (McShane et al., 2011; Anderson and Leach, 2019; Rice et al., 2019). As such, there is need to pay more attention to both emancipatory governance (Scoones et al., 2020) and the social justice implications of systemic transformations.

The concept of a just transformation, particularly within the UNFCCC, has so far been less well-developed in relation to agriculture than it has been in the energy sector. In this context, KJWA has represented a forum and timely opportunity for developing a shared vision and understanding of a just transformation for agriculture, and one that can be reflected in and have influence over the distribution and use of climate finance, and the agricultural sector strategies set out in national adaptation plans and mitigation commitments. Therefore, we examine the extent to which inequalities are considered and integrated into KJWA and whether this offers a step change in the conceptualization of just transformation for agriculture within efforts to mainstream agriculture into the UNFCCC and the implementation of the Paris Agreement. We specifically ask:

To what extent and in what ways has a just agricultural transformation been envisioned within the Koronivia Joint Working Group on Agriculture?

We go on to discuss the future of agriculture within the UNFCCC, and in national climate change commitments, post Koronivia, particularly in the context of the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation of Climate Action on Agriculture and Food Security (referred to hereafter as the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation). Reflecting on the achievements and shortcomings of KJWA we reflect on how this can be a platform for the ongoing work of promoting just agricultural transformation through the UNFCCC.

The Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) makes explicit the objective of lowering greenhouse gas emissions to an extent that global warming is limited to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Agriculture is not directly referred to in the Paris Agreement and has been considered in a piecemeal and often contested way through working groups of the UNFCCC, such as the Warsaw Framework for REDD+. In an attempt to redress this omission, in 2013, the Scientific Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) held five in-session workshops to provide opportunities for Parties to exchange their views on issues relating to agriculture.

At the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties 23 (COP 23), a landmark decision was taken for the introduction of an agenda through which the two permanent subsidiary bodies [the on Science and technological advice (SBSTA) and on implementation (SBI)] would jointly address and report to COP on issues related to agriculture within the framework convention. KJWA was the first and only agenda item to focus specifically on agriculture and food security under UNFCCC. Representatives of UNFCCC constituted bodies, parties and observers admitted under the UNFCCC (see Supplementary material for full list of organizations) set out a roadmap of focused workshops, and an open consultation for the submission of written views and recommendations regarding six key topics selected for the Koronivia process to the UNFCCC secretariat:

• Modalities for implementation of the outcomes of the five in-session workshops on issues related to agriculture and other future topics that may arise from this work;

• Methods and approaches for assessing adaptation, adaptation co-benefits, and resilience;

• Improved soil carbon, soil health, and soil fertility under grassland and cropland as well as integrated systems, including water management;

• Improved nutrient use and manure management toward sustainable and resilient agricultural systems;

• Improved livestock management systems;

• Socioeconomic and food security dimensions of climate change in the agricultural sector.

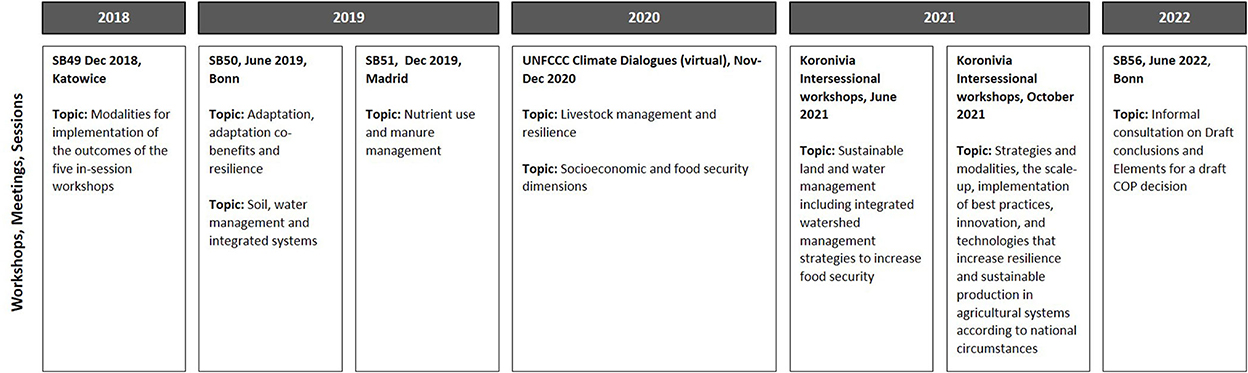

The Koronivia roadmap provides a timeline of in-session workshops to be conducted under KJWA and determined how the joint work would be organized (see Figure 1). Workshops for each of the six KJWA topics were to be held during the 2018–2020 Subsidiary Body sessions, which take place twice a year: in May/June in Bonn and in conjunction with the Conferences of Parties (COP), in November/December. Due to COVID-19, changes were made to the original road map, according to which Parties were to submit the final work plan to the COP in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2020. Although COP 26 was formally held in 2021, the agenda of the Koronivia working group continued with further workshops focusing on “strategies and modalities, the scale of implementation of best practices, innovations, and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstances.” In June 2022, at the SB56 in Bonn, the Koronivia working group held a workshop with a focus on the finalization and implementation of the decision (https://unfccc.int/event/sbi-56).

Figure 1. Timeline of Koronivia workshops, adapted from Drieux et al. (2021) Koronivia roadmap. Written submissions were invited through an open consultation process prior to each workshop.

Workshops comprised of invited presentations from a variety of Experts, Parties, and Observers, with the KJWA chairperson offering and facilitating an opportunity for Parties and Observers opportunity to ask questions or make comment. Workshop video recordings, written contributions by Parties and Observers and COP and SBI/SBSTA statements (including workshop conclusions, drafted, and agreed by negotiators from each all Parties) are all documented online at the UNFCCC website (https://unfccc.int/cd2020/schedule#eq-2).

A protracted series of formal informal meetings of KJWA at COP27 resulted in the decision, formalized through the COP27 President, to establish the 4-year Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation under the SBI and SBSTA. The role of this work would be to take forward the implementation of Koronivia, with the following stated objectives:

“(a) Promoting a holistic approach to addressing issues related to agriculture and food security, taking into consideration regional, national, and local circumstances, in order to deliver a range of multiple benefits, where applicable, such as adaptation, adaptation co-benefits, and mitigation, recognizing that adaptation is a priority for vulnerable groups, including women, indigenous peoples, and small-scale farmers;

(b) Enhancing coherence, synergies, coordination, communication and interaction between Parties, constituted bodies and workstreams, the operating entities of the Financial Mechanism, the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund, and the Special Climate Change Fund in order to facilitate the implementation of action to address issues related to agriculture and food security;

(c) Promoting synergies and strengthening engagement, collaboration and partnerships among national, regional, and international organizations and other relevant stakeholders, as well as under relevant processes and initiatives, in order to enhance the implementation of climate action to address issues related to agriculture and food security;

(d) Providing support and technical advice to Parties, constituted bodies, and the operating entities of the Financial Mechanism on climate action to address issues related to agriculture and food security, respecting the Party-driven approach and in accordance with their respective procedures and mandates;

(e) Enhancing research and development on issues related to agriculture and food security and consolidating and sharing related scientific, technological and other information, knowledge (including local and indigenous knowledge), experience, innovations, and best practices;

(f) Evaluating progress in implementing and cooperating on climate action to address issues related to agriculture and food security;

(g) Sharing information and knowledge on developing and implementing national policies, plans, and strategies related to climate change, while recognizing country-specific needs and contexts.”

Extract from UNFCCC (2022) Joint work on implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security, Proposal by the President, Draft decision/CP.27.

We start from the understanding that agriculture and food systems connect individuals and institutions (for example, through the flow of goods) across scales and sites, but that these systems are themselves embedded within economic, political, and institutional structures. Transformation, then, broadly refers to a fundamental change in circumstance occurring to, for and by living beings within these systems and structures (Scoones et al., 2020; Whitfield et al., 2021). The processes that generate transformations can result from incremental, carefully planned interventions made often by policy actors (Schot and Steinmueller, 2018), or they can be an emergent property of large-scale political-economic forces and social mobilization (Stirling, 2015). In other cases, transformation is outside the control of any actor or group, triggered by exogenous biophysical forces such as climate change (Kates et al., 2012).

Scoones et al. (2020) draw a distinction between three perspectives on transformations: structural, systemic and enabling (Scoones et al., 2020). A structural approach focuses on fundamental change in underlying ideologies, political regimes and market structures that shape society and lock us in to conventional growth-centered, visions of agriculture (D'Alisa and Kallis, 2020). It is an “all-in” perspective on transformation, based on the understanding that disruption to these regimes has foundational knock-on effects across all of society, often with notions of justice and equity as central philosophy, but arguably de-emphasizing the desirability of more incremental changes (Wezel et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2020). In contrast, a systemic transformation perspective focuses more on the components and interconnections of specific systems, such as food and agricultural systems, and the potential for these systems to be altered and disrupted through changes to these components and relationships (Sachs et al., 2019). This could be in the form of changes in consumer behaviors, the introduction and adoption of technologies, or new public-private partnerships, for example. Such perspectives arguably pay less attention to the issues of politics and power, but can also be somewhat blind to micro-level, autonomous and ad-hoc process of bottom-up change (Anderson et al., 2019). By contrast, from an enabling perspective, individual agency and action is not only seen as a driver of change but as a vision or objective of transformation in its own right. From such a perspective, emphasis is less on a pre-conceived vision of an altered systemic or structural future, and more on the enabling of individuals to mobilize, have an active voice in the governance of their own contexts and environments and continually shape the future trajectories of these. Here the focus is on recognizing and challenging unequal power dynamics that act to marginalize or exclude voices in the governance of agriculture and food systems (Pereira et al., 2018).

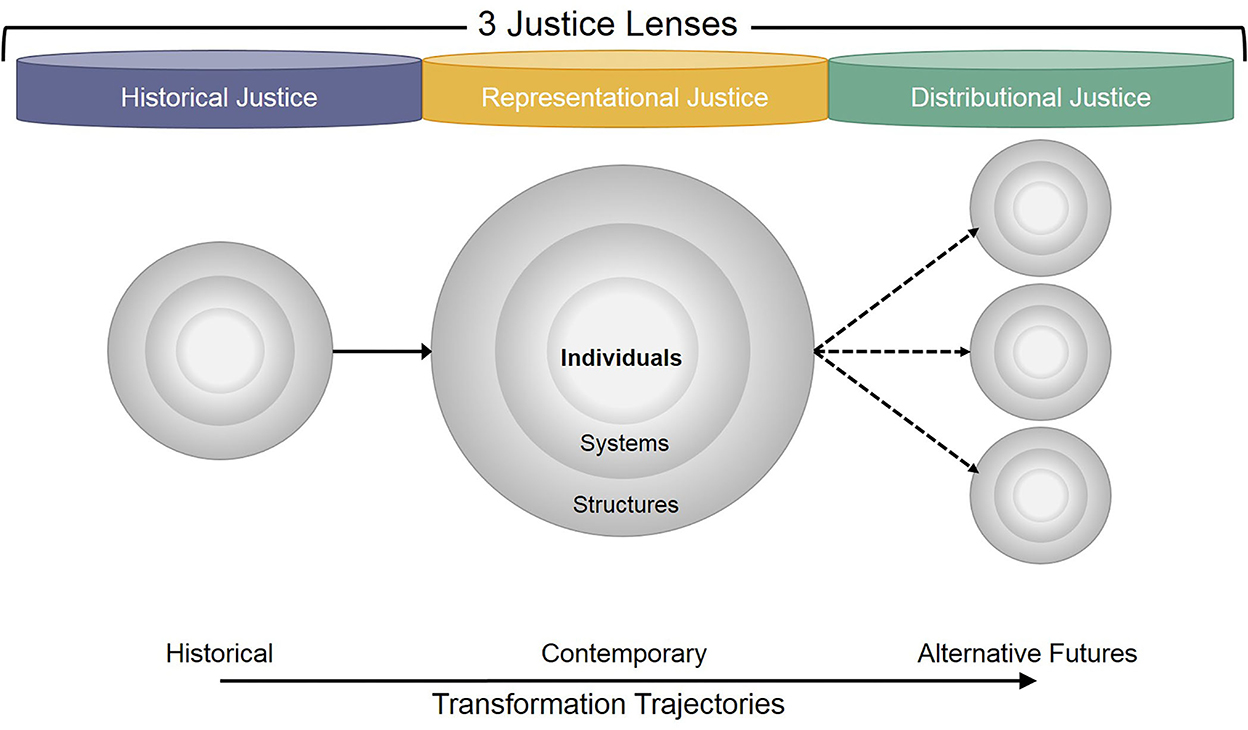

There is an important time dimension to transformation. Individuals, systems, and structures have a history that has shaped contemporary experiences and to some extent sets the parameters of imagined alternative futures. We might think of there existing a certain path dependency in that future systems are intrinsically connected to historical ones (D'Alisa and Kallis, 2020; Whitfield et al., 2021). Structural, systemic and enabling approaches are not mutually exclusive (Scoones et al., 2020). They offer alternative analytical lenses on transformative change that we seek to hold in balance and tension with each other as we explore the ways in which transformation has been conceived of within KJWA.

We draw from the framework of Whitfield et al. (2021), and prior work on just transformation (e.g., Jasanoff, 2018; Bennett et al., 2019), which argues that it is important to adopt at least three different justice lenses when considering what justice means in the context of agriculture and food systems transformation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Food systems transformation and justice reproduced and adapted from Whitfield et al. (2021).

Firstly a historical justice lens focuses our attention on how deep-seated inequalities experienced over time, both inform the contemporary state of food systems and often become replicated and reinforced through trajectories of change into the future. Although the technologies and strategies proposed in current agrarian policies for the global south countries differ from those of the colonial era and of the green revolution of the 1960s, issues of elite capture of benefits, marginalization of alternative knowledge, pre-existing ideologies and paradigms and north-south transfer of knowledge and technologies continue to be reproduced (Patel, 2013; Whitfield, 2015). Adopting a historical justice lens helps to analyze how current policies of agriculture and food systems may exacerbate inequalities already experienced by various groups of people (women, youth, indigenous people, and other vulnerable groups) over time and reinforced through future trajectories.

Secondly a representational justice lens turns our attention to governance processes and the voices that do or do not speak into the visioning and governing of transformation. It forces us to recognize that priorities and perspectives on agriculture and food system are many and varied and that there are perspectives that are marginalized and do not have an adequate voice for a variety of reasons. People, systems, and structures may all be represented in the discourse on agriculture and food systems, from community-based governance, social movements, donor-driven research, and development efforts to multilateral agencies. However, there is a potential that interests that emerge from different spaces and at different levels may be conflicting. At the same time, ideas can be subordinate to, or co-opted by, the power of elites, patriarchy, and wealth (Whitfield et al., 2021). Furthermore, Newell and Taylor (2018) argued that there is a macro-level regime complex of powerful institutions that have merged around the technological promise of “climate smart” agricultural transformation, with implications for the type of innovations that may be promoted and its profits for intended beneficiaries. A representational justice lens might also encourage us to recognize that some stakeholders cannot speak directly for themselves—we might think about non-human actors (i.e., plants and animals) or future generations, and the ways in which they are represented.

The third lens is a distributional justice lens, which turns our attention to the outcomes of transformation and how goods and risks are distributed—the distribution of access to and security of food, but also nutrition, waste, energy, land, income, employment, ecosystem services, and more (Bennett et al., 2019). Although access to these benefits or risks are likely to be shaped by geography, race, ethnic group, gender, age and more, it is important to recognize the intersectionality and multifaceted nature of identity that individuals hold (Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2019; Tavenner and Crane, 2019). It is equally important to recognize that imagined transformation trajectories potentially become realities for future generations. Neither those of the past nor future can speak directly into the governance of imagined transformations or lay claim to their rights. The potential for the diversity of contexts and the intersectional identities of individuals to be overlooked within the ambitions of agriculture and food systems transformation represents one of its greatest risks from a distributional justice perspective (Whitfield, 2015). A distributional justice lens encourages us to recognize that different individuals might differently prioritize and place different value on these goods and risks.

Analyzing food system transformation through multiple justice lenses (historical, representational, and distributional dimensions) can help expose hidden injustices across transformation trajectories. Translating this concept into key principles, then, we argue that in the visioning and governing of agricultural transformation there is also a need: to engage with power and political regimes; to represent multiple sites and scales; and to give a voice to the complex histories and complex intersectionalities that shape individuals' experiences of, and perspectives on transformation. We adopt these three justice lenses—historical, representational, and distributional—in analyzing the ways in which justice has been framed and discussed within KJWA, particularly to understand if certain framings predominate over others.

The research presented below is based on a deductive discourse analysis of secondary data that sought to identity and categorize the dominate framings and narratives of justice within a large body of textual and audio-visual archived material (Janks, 1997; Fairclough, 2013). We applied the above described analytical framework to identifying justice language and concepts within the KJWA. Submissions to KJWA, workshop presentations and recordings, meeting minutes, press statements, and meeting reports were collated from the FAO and UNFCCC web portals, screened and transcribed for textual analysis.

A total of 1,441 unique data sources were originally collated from 2013 SBSTA's five in-session workshops to the Koronivia workshop held in Bonn, 2022. Audio and video files were transcribed and all filed screened on the basis of: (a) having reference to terrestrial agriculture and/or food; (b) including one of the following keywords and their variants: “Equity,” “Equality,” “Justice,” “Distribution,” “History/Historical,” “Compensation,” and “Representation.” This initial screening reduced the total number of data sources to 155, of which 23 were transcripts of video recordings from KJWA workshops and meetings, and 129 were written submissions and statements from bodies contributing to KJWA.

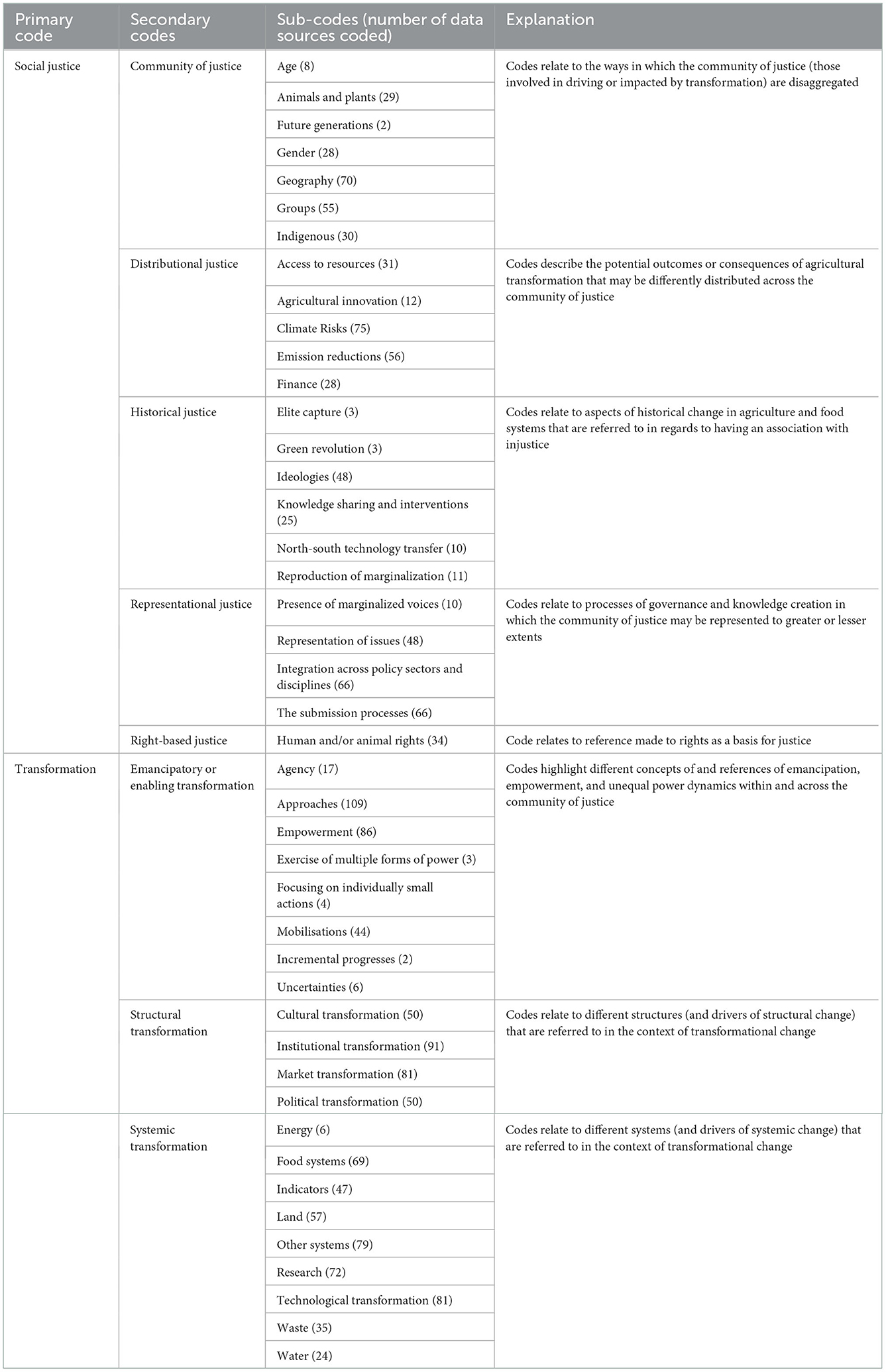

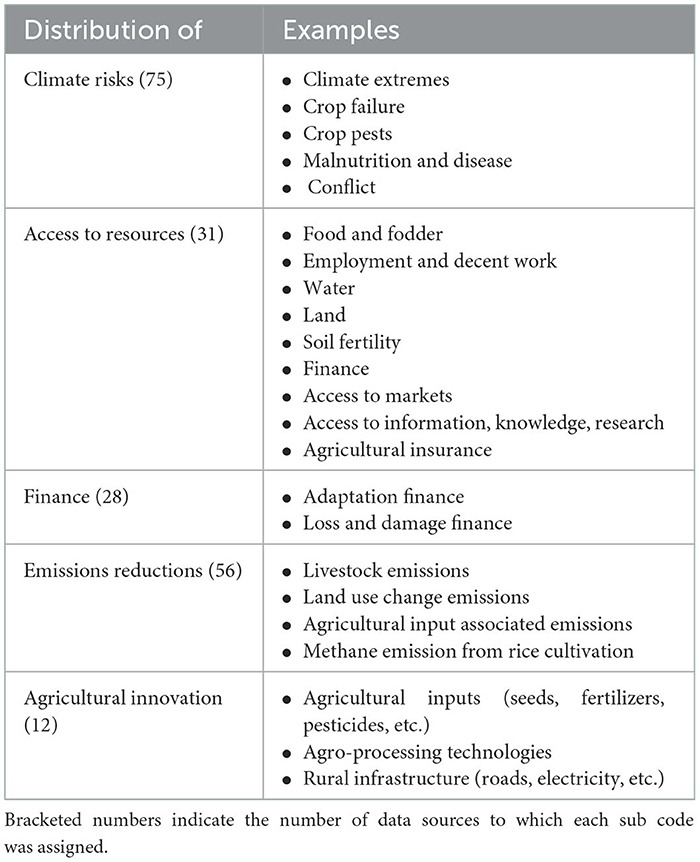

The documents were uploaded into the NVIVO software and coded, using a hierarchical coding structure (Table 1) based on the analytical framework on social justice and transformation. We applied critical discourse analysis to examine the text, interpret framings, and discourses and construct a narrative description.

Table 1. List of codes applied in analyzing data with an indication of the number of data sources to which each sub code was assigned.

We begin by unpacking how transformation has been framed within Koronivia discussions, from discourses around technological fix and incremental agri-system change to more radical re-imaginings of political and market structures as well as more emancipatory forms of transformation, focused on enabling social movements and tackling inequalities. In the following sections we explore how equity has been discussed within Koronivia, in particular we unpack framings of who faces inequity and who a just transformation is for (the community of justice); and what equality and justice means in the agricultural context (highlighting references to distributional, representational, and historical justice).

A familiar tension is evident across submissions to the Koronivia workshops between those advocating for the adoption and upscaling of modern agricultural technologies and practices (such as improved crop varieties, precision fertilizer usage, irrigation, and more) and those calling for a more radical, but rooted in traditional knowledge and practice, rethinking of production oriented agricultural development. The former is closely associated with well-established coalitions of international agricultural research institutions, donors, and intergovernmental institutions (such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, CGIAR, IFAD, the World Bank among other donor organizations), and is exemplified in the ClimateShot: Accelerating Agricultural Innovation Agenda which was launched at COP26. The latter is more commonly associated with grassroots and non-governmental organizations (such as Consumers International, The Indigenous and Peasant Coordinating Association of Central American Community Agroforestry, 4 per 1,000, Regenerative International etc.) who have widely denounced the conventional discourse around climate smart agriculture, arguing that this reinforces unsustainable agricultural intensification:

“We must recall that Climate-Smart Agriculture is not an approach that can contribute to the identification of agricultural practices and technologies in climate actions in any meaningful way, since this discourse issued to promote models and practices inherited from the past and which pose serious threats to long-term ecological and economical resilience.”

[Excerpt of written submission by Action Contre la Faim, Agronomes, & Vétérinaires Sans Frontiers; Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law, and Development; ccfd-terre solidaire; CEO; CIDSE; drynet, Environmental Monitoring Group; Global Forest Coalition; Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy; TEMA to the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), May 2016].

This distinction is associated with alternative understandings of the challenge of agriculture in climate change. A technical fix framing that has underpinned discussions within Koronivia on access to finance and research and development, whereas as more politicized understanding of the challenges has underpinned an explicit focus on institutions and governance. However, the battle lines between these alternative visions for agricultural transformation are arguably less distinct among Koronivia participants than they have been historically. Proponents of Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) and innovation rarely refer to single or narrowly defined technologies, but rather have incorporated principles of knowledge and information sharing, innovation platforms, and participatory resource governance into a broadening and increasingly inclusive vision for future agriculture [see for instance, Submission from the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) on issues relating to SBSTA] on behalf of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CCAFs). Koronivia has seen the language of CSA adopted by representatives of a broad range of Parties from both develop and developing countries.

Similarly, the explicit inclusion and prioritization of agro-ecology have been put forward by a variety of Parties and observer groups, and is particularly central to the advocacy of the YOUNGO, ENGO, and Farmer observer groups within the UNFCCC:

“It is critical that we engage an ambitious agro-ecological transition.”

[Excerpt of written submission by YOUNGO to the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture, undated].

Agro-ecology is a term that has been used to represent a spectrum of ideals, from nature-based and low intensity land management practices through to more structural reconfigurations toward degrowth and food system localization. However, the explicit inclusion of agro-ecology in the text of Koronivia documents has not garnered sufficient consensus, and remains a political issue. This is in part because it directly challenges the agricultural commercialization and industrialization agendas to which many governments and private sector interests are aligned, and in part because of ongoing debate about the ability to feed a growing population, a point that has been vehemently argued from multiple directions throughout Koronivia.

What is common, or at least seemingly less contested, across these different perspectives is a focus on transformation at the level of the individual; the notion that systemic change can be brought about through the cumulative effect of changes among individual land users and consumers. This is particularly evident in the emphasis that is being placed on the “upscaling” of agricultural solutions, which many have argued should be the emphasis of post-Koronivia efforts:

“We really need a systemic shift that focuses on 100 million farmers.”

[Quotation from presentation by the Head of Partnerships and Outreach of the CGIAR, at KJWA workshop on Strategies and modalities to scale up implementation of best practices, innovations, and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstances, October 2021].

As the Secretariat's report on the Socioeconomic and food security dimensions of climate change in the agricultural sector Workshop indicates, these discussions around upscaling not only cross the agro-ecology and CSA camps, but also extend to individual contexts, vulnerabilities, and inequalities which can represent constraints on achieving upscaling:

“General guidelines for action in the agriculture sector should be developed under the KJWA that focus on adaptation and take into account how power imbalances in agriculture constrain the upscaling of sustainable agriculture and agroecology.”

[Excerpt from workshop report by the UNFCCC secretariat on Socioeconomic and food security dimensions of climate change in the agricultural sector, April 2021].

This discourse on scaling up gives rise to a broad consensus, albeit coming from a predominantly instrumental perspective, around the need to build capacities, and address the needs of the most vulnerable. Submissions from the Women's Environment and Development Organization, Care International, UN FAO, and others similarly stated that effective transformation requires that women, youth, local communities and indigenous people are granted greater access to education, inputs, other resources, and services. This is illustrative of a broad recognition that inequality is a root cause of challenges in the agricultural sector and resonates with notions of emancipatory transformation that focus less on effecting socio-technological change, and more on the empowerment of individuals.

This focus on individual transformations can be contrasted, although is not incompatible, with calls for institutional transformations, which have been similarly evident in Koronivia. This institutional focus is arguably drawing greater attention to the root causes of inequality and vulnerability rather than the symptoms. At the workshop focusing on socioeconomic dimensions of climate change in agricultural sector, some parties, and observers advocated for policies that can regulate land price and illegal land use, for example. Others have pointed to the need for creating enabling environments for farmers to form cooperatives and access markets and finance. These calls for institutional change, extend to advocates for change in the UNFCCC and its associated processes (such as in commitments and national adaptation plans of Parties) itself, and in many ways, this is central to the broad objective of Koronivia, to reposition agriculture within the framework convention.

As mentioned above, reference to inequalities and uneven responsibility for, and impacts of, climate change are evident throughout the submissions and workshop discussions of Koronivia. However, collectively they represent a relatively narrow conceptualization of the community of justice. Strong emphasis on gender and age-related inequalities in climate impacts is particularly evident and discourse predominantly emphasizes the compounded vulnerabilities to climate change of female-headed, poor, rural households in the Global South. This is a perspective that has been exemplified in the submissions of the World Food Programme and the World Health Organization:

“Impacts of climate change are expected to disproportionately affect the welfare of the most vulnerable in the poor and marginalized in rural areas, such as female-headed households and those with limited access to land, productive assets, infrastructure, and education.”

[Excerpt of written submission by the World Food Programme to SBSTA on views related to the identification of adaptation measures and assessment of agricultural practices and technologies to enhance productivity in a sustainable manner, food security, and resilience, undated].

Discussion about intergenerational inequality has focused on children and youth, and specifically on youth unemployment and rural-urban migration. Less evident are references to past or future generations. Of course, there are many references made to the projections that populations will grow, and climate impacts will intensify into the future, thereby exacerbating challenges of achieving food security. However, this rarely translates into a discussion of the novel vulnerabilities or uneven distribution of risks within future generations compared with those of the present—the inequities between those currently living with those yet to exist. As we go on to discuss, the Koronivia process has also been surprisingly void of discussions around historical and differentiated responsibility.

There is an equal focus, although largely coming from a different group of contributors, on indigenous peoples. A close counterpart to arguments about the disproportionate vulnerability of these groups is a clear call for greater representation and voice and the need for indigenous knowledge-centered approaches to climate governance. This broad and increasingly conventional narrative of participation encapsulates both the normative values of representation and rights, as well as pragmatic virtues of indigenous and women's knowledges in addressing climate challenges:

“Indigenous peoples should take the lead on deciding what should be done on a global scale.”

[Quotation from presentation by the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations at KJWA workshop on strategies and modalities, the scale of implementation of best practices, innovations, and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstance, October 2021].

Geographically, across the Koronivia programme, we observe references to the shared and global nature of climate change impacts and food system challenges, which speak directly to the UNFCCC as a global institution and its cooperative, shared responsibility agenda. But Koronivia has also been a platform for countless appeals and presentations from member states and negotiating groups such as AOSIS, the African Group, and G77 and China, around context specific climate impacts on agriculture and uneven geographic distribution of these, particularly between the Global North and Global South.

“Pastoralists in Kenya, rice farmers in India, and industrial feedlot operators in the U.S. are all contending with increased frequency of drought and erratic weather.”

[Excerpt from written submission by Brighter Green submission on agriculture to SBSTA of UNFCCC, 2013].

An (arguably superficial) intersectional perspective on vulnerability—acknowledging the interrelated demographic, geographic, and institutional contexts in which climate impacts are experienced—represents a broadly accepted convention across the UNFCCC. However, within Koronivia this understanding of intersectionality has not often translated into an interrogation or focus on the underlying causes of these vulnerabilities. This point, raised by a smallholder farmer who was an expert panelist at the Koronivia workshop on improved nutrient use and manure management toward sustainable and resilient agricultural systems (November 2020), represents a rare exception:

“Women farmers in Malawi face additional challenges because they cannot own land there, their participation in decision-making processes, where they could communicate their needs, is limited and they are poorly represented in development structures in the country because of their high illiteracy level. They also lack access to agricultural public extension workers.”

[Quotation from participant in the workshop on improved nutrient use and manure management toward sustainable and resilient agricultural systems (November 2020)].

More often, this focus on multifaceted vulnerability, has simply served to support the argument that there should be more resources, or improved representation, for vulnerable and marginalized groups within climate action and solutions.

There has also been a fundamental anthropocentrism to Koronivia discussions. In the workshop organized around Livestock Management there was an inevitable and implicit emphasis on animals as livestock, with discussion around animals largely focusing on their productivity, nutritional value, and emissions. Very rarely have concerns over animal welfare been expressed within the Koronivia. Rarer still have been more biocentric views concerned with the rights of animals or their identities and welfare beyond their role as productive units. Although agroecology has been proposed by many as a solution for enhancing biodiversity and restoring carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous cycles, across the Koronivia dialogues, there is a seemingly accepted and unchallenged framing of agriculture as distinct from natural systems. As such broader ecological and philosophical perspectives on nature fall somewhat outside of the accepted, although rarely debated, scope of Koronivia.

Discussions on who is represented within agricultural transformation were inevitably entangled with critical reflections on who is represented within the Koronivia process itself. An often raised self-critique of these dialogues is that there is a disconnect between those negotiating on behalf of UNFCCC Parties and the farmers on the ground, who do not have a direct voice into these discussions.

“We are arguing about mitigation and adaptation but the farmers who are affected and who are causing this are not here. Their voices are not being heard, their situation is not being projected directly.”

[Quotation from representative from Uganda at the WWF side event at COP26: “Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture: What next Lessons learnt and perspectives,” November 2021].

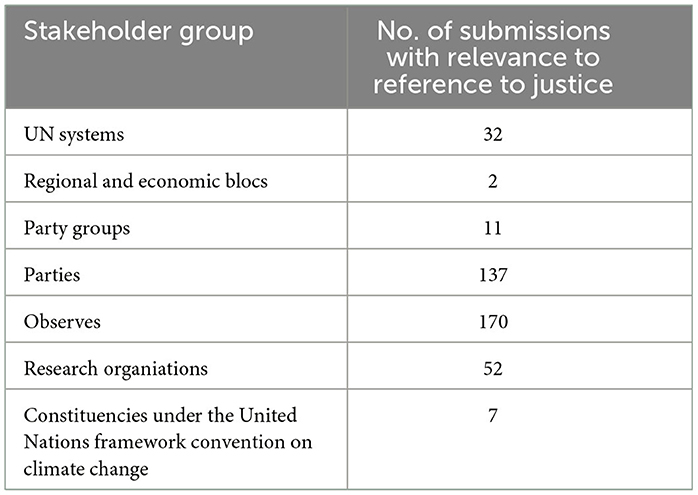

Across the Koronivia workshops and in the submissions of written statements, however, there has been input from a wide variety of representatives: of farmer groups, civil society, and non-governmental organizations as well as research institutions (see Tables 2, 3).

Table 2. The number of submissions with perspectives deemed to have a (implicit or explicit) justice-related reference, by stakeholder group (see Supplementary material for full list of organizations).

Table 3. The number of submissions deemed to have a (implicit or explicit) justice-related reference by NGOs, research and parties on justice showing the geographical region represented by the submitting organization.

This has helped to reinforce a common narrative across the Koronivia dialogues, and one that it is recognized in the draft decision text for COP27, about the need for inclusive, multi-level and co-ordinated process of action-planning, policy and investment in order to leverage transformative change that is at the same time context-specific and delivered at scale:

“Our intent is that farmer voices are not only heard but that they have an opportunity to provide significant input to national, global and local agricultural policies.”

[Quotation from Representative of Farmers Constituency at the KJWA workshop on Socioeconomic and Food security dimensions of climate change in the agricultural sector, December 2020].

“Highlighting that each food and production system has its own challenges, and solutions must be context-specific and country-driven, and that, for strategies and their implementation to be scaled up, they must be customized for local conditions.”

[Excerpt from Enhanced consideration and implementation of elements related to agriculture—Elements of a Draft COP Decision, June 2022].

Despite the calls for more context-specific action, investment, and capacity building at local scales, as Koronivia has progressed, frustrations have also been expressed about lack of ambition in these plans, and the desire to see agricultural innovations and support structures scaled up. The language of scaling up has been often repeated as parties express their ambitions for an implementation-focused post-Koronivia process, and this is reflected too in the commitments by many Parties to the Action Agenda for Innovation in Agriculture made at COP26. Some parties also expressed concern about low uptake of project or scalability of agricultural innovations. Some discussants mentioned that bottom-up approaches are rarely applied in the agricultural innovations while the selection of farmers for the interventions is also crucial in the adoption of innovation and upscale.

“[…] if you offer the technological options to the farmer, they need to understand what are those technologies and practices are about and what are the benefits that they can gain.”

[Quotation from representative of Indonesia at the Koronivia workshop on Strategies and modalities to scale up implementation of best practices innovations and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstances, October 2021].

The governance of agricultural transformation occurs at different scales and decision contexts. In the Koronivia process, discussions about the governance of transformation were dispersed throughout the roadmap and points raised about the need for engagement from multiple actors in driving change in finance, land, innovation, resources, and other decision-making processes were reiterated throughout. National governments were identified as key actors in the governance of agricultural transformation, but there was also recognition of the need for multi-level and participatory governance and public-private partnerships, to bring about effective agricultural change in different contexts. Other discussions within Koronivia focused on how to make choices and highlighted the absence of, and need for, consistent monitoring and evaluation metrics, data, and information sharing platforms to inform decision making at different scales.

Distributional justice has been implicitly discussed throughout the Koronivia dialogues, in ways that are largely consistent and compatible with the UNFCCC's underlying principle of common but differentiated responsibility. This has included discussions on the distribution of agricultural and food-related emissions, the distribution of agro-climatic risks (including indirect risks such as pests and diseases), and the distribution of adaptive capacities (Table 4).

Table 4. References to unequal distribution within Koronivia workshops and submissions organized on the basis of distributional justice sub codes identified within Table 1.

Across Koronivia workshops on technical aspects of agricultural practice (such as those focused on Soil, Water Management and Integrated Systems and on Nutrient Use and Manure Management) a variety of participants have raised issues around uneven access to finance, as well as to technologies, land, and natural resources that constrain agricultural practices and limit adaptive capacities. At the Koronivia workshops, presentations shows that the amount of global finance available to agricultural sector is minimal compared to other sectors such as energy and transport. Similarly, there is less funding available for adaptation particularly in the area of agriculture.

There has been some debate within Koronivia workshops about the extent to which support, and resource is directed to large commercial vs. small scale farms. Additionally, smallholder farmers often face challenges accessing credit required to invest in long term adaptation practices. The argument goes further that most smallholder farmers in the global south depend on imported farm inputs. The limited finance available to the sector coupled with high inflation in most countries affects the adoption of innovation for mitigation or adaptation. Concerns have also been highlighted that even where there is an intended flow of finance (e.g., through the Global Climate Fund) that this does not necessarily reach the farmers themselves.

“There's definitely that lack of targeting in terms of funding going for small scale farmer.”

[Quotation from representative from IFAD at KJWA workshop on Strategies and modalities to scale up implementation of best practices innovations and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstances, October 2021].

“We need to make sure that the funding flows on the ground I mean directly to the communities.”

[Quotation from the representative of the Adaptation Fund at the Koronivia expert dialogue on channels to unlock climate finance for adaptation and resilience—COP 26/IFAD Pavilion virtual event, November 2021].

There has been a notable variety in the sites and scales at which this distribution of risks, resources, and responsibilities is considered. Throughout the dialogues and workshops, there are well-rehearsed and much-repeated statistics about the main sources of GHG emissions. But choosing to highlight geographic and historical differences in emissions (e.g., between the Global North and South) acts to frame any consideration of distributional justice in a very different way to those contributions that highlight differences within sectors (e.g., across different parts of the supply chain, or different systems of production). One might compare, for example, these two statements that differently describe disproportionate emissions firstly on a Global North vs. Global South basis and secondly on a livestock vs. non-livestock production system basis:

“Urgent action is needed now, primarily due to the historical emission of GHGs, which reflect the pattern of wealth inequality globally, with almost 75% of all historical emissions coming from just over 20% of the global population in the North.”

[Excerpt from written submission by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP)-Institute for Policy Studies (IPS)—Third World Network (TWN) Tebtebba (Indigenous Peoples' International Center for Policy Research and Education) Also on behalf of: Asian Indigenous Women's Network—(earth)—Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland -Friends of the Earth Malaysia-Sustainable Energy and Economy Network (SEEN) to SBSTA].

“Around 75% of agriculture's emissions are produced by livestock, including the production of feed for livestock and the associated land use changes.”

[Excerpt from written submission by Isis Alvarez, Global Forest Coalition, Colombia on behalf of the Women Gender Constituency, Speaking points, to the KJWA: “Improved livestock management systems, including agropastoral production systems and others”].

Beyond a focus on nation states, contributors to Koronivia have also repeatedly highlighted the unequal distribution of risks and resources at more local and micro-scales. In many cases, such interventions highlight gendered differences in access to resources and adaptive capacities, but they have also highlighted how interventions and support programmes can become concentrated in desirable regions and localities for funded pilot programmes.

Beyond a recognition of the unequal historical contributions to emissions of Parties, there has been very little discussion of historical injustice, in agriculture and food systems—such as injustices related to dispossession and land grabbing, slavery, and workers' rights and corporate take-over of intellectual property and markets—throughout the Koronivia workshops. Furthermore, while this recognition of differentiated responsibility helps to align Koronivia with the NDCs and adaptation finance mechanisms of the UNFCCC, the language of Article 8 of the Paris Agreement on Loss and Damage has been notably absent from all of the discussions and outputs of Koronivia. This signals an apparently conscious decision to separate out the issues of climate impacts and adaptation in agriculture from the most politicized and contested aspects of the UNFCCC negotiations.

One notable exception to this was the intervention made by Michael Fakhry, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations, at the Koronivia intersessional workshop on strategies and modalities, the scale of implementation of best practices, innovations and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstance (October 2021). The quotation from the Special Rapporteur states:

“How people eat is not just an economic decision it really is historical and cultural and being told what to eat has a long history of power dynamics. So right now unfortunately the relationship is not between consumers and producers working out based on these cultural and historical traditions and being dynamic as things change how we eat always changes even traditional ways are evolving but again it has to be about that relationship. Unfortunately now most food systems, most people the choice of what they get to eat is dictated by corporations.”

[Quotation from Michael Fakhry, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations, Workshop on strategies and modalities, the scale of implementation of best practices, innovations and technologies that increase resilience and sustainable production in agricultural systems according to national circumstance (October 2021)].

This workshop briefly opened up a rare (within the Koronivia context) discussion about the ways in which industrialization and capitalist interests have shaped production practices, food access and supply, and shaped agricultural research agendas, in all cases exacerbating inequalities and locking resource-constrained producers into the mono-crop production of foods with low nutrient value and poor resilience to climate variability. This discussion, remained at a largely ideological level rather than unpacking specific examples or experiences from any of the Parties, and it was only briefly referred to in the report of this session. It was also notable that this discussion did not extend to explicit acknowledgments of the way that histories of colonialism and occupation in the Global South have driven the spread of capitalism-oriented agriculture as well as shaping inequitable land rights and eroding indigenous and traditional knowledge and intellectual property rights.

The importance of taking a Rights-based approach to agricultural transformation was raised at the Workshop on “Socioeconomic and food security dimensions of climate change in the agricultural sector” at which the International Union of Food Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco, and Allied Workers Associations delivered a statement on behalf of trade union NGOs that proposed that the universal right to food should be central and guiding principle around which food system transformation is oriented:

International Union advocates a rights-based approach to addressing the socioeconomic and food security dimensions of climate change, whereby the right to food must frame the shift to climate-friendly agricultural practices.

[Excerpt of report by the UNFCCC Secretariat on in-session workshop on improved soil carbon, soil health, and soil fertility under grassland and cropland as well as integrated systems, including water management, June 2019].

However, it is not only the Right to Food that is highlighted in relation to a rights-based approach, also raised were the Rights to Decent Work and the Universal Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The latter was often interpreted as a right to land access and ownership as well as the protection of indigenous knowledges and the right to practice indigenous forms of agriculture. The Co-chair of the Facilitative Working Group of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform emphasized the importance of a rights-based approach that builds on existing agreements, such as the 2002 Declaration of Atitlán, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the recognition of their rights in the Paris Agreement, which set the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and wellbeing of indigenous peoples. They mentioned further that a temperature increase of as little as 2°C would put them at risk of losing land and cultural and natural heritage and disrupt cultural practices embedded in their livelihoods.

We find that references to just transformations in agriculture, within the Koronivia Joint Working Group on Agriculture are largely implicit, but not absent. Justice is arguably most obvious and evident when it comes to discussion about who agricultural transformation is for and who is (and where are) the most vulnerable to climate change and variability. Such discussions come from an instrumental perspective as much as an ethical one. Appeals about where, and to whom (i.e., the most vulnerable) technologies, information, and finances need to be directed are as much, if not more, about how to achieve scaled-up agricultural transformation than they are about addressing distributional injustices in agricultural resources. Even less evident have been explicit appeals to address the historical injustices that have shaped agricultural and rural livelihoods, to provide compensatory finance for loss and damage from climate change in agriculture, or from colonial and exploitative land ownership, labor conditions, and market and power asymmetries.

One of the successes of the KJWG is the number and variety of submissions and inputs that it generated over its 4 year process. These represent the contributions of varied interest groups with global coverage. Broad representation within KJWG translated into a significant emphasis being placed on the theme of representation and, in particular on participants highlighting the importance of different voices and knowledges governing and guiding agricultural transformation. However, workshops and negotiations under KJWG rarely critically interrogated issues of politics and power, with contentious issues (such as corporate control of food systems, and reducing meat and dairy consumption) mostly avoided, aside from rare debates over agroecology vs. agricultural modernization and over the use of the language of “mitigation” vs. “adaptation co-benefits,” for example. This is arguably symptomatic of the UNFCCC process and the importance placed within UNFCCC negotiations on consensus building. The consequence of this is that more fundamental structural change, which is inevitable contentious, came to be understood as somewhat out of the scope of Koronivia and in turn this squeezes the discursive space for recognizing and addressing historical injustice.

References, again often implicitly made, to rights-based understandings of agricultural transformation arguably offer the most comprehensive framing of justice within Koronivia. A rights-based framing of justice reflects a historical dimension, as well-distributive (e.g., right to food) and representative (e.g., indigenous rights and rights to political voice). However, while the recognition of these rights within discursive forums is important, discussions within Koronivia have not gone as far as identifying and determining how these rights could or should be recognized and protected through the mechanisms of the UNFCCC.

We have unpicked KJWG discussions and the multifaceted ways in which they have intersected with different notions of justice. We note that to date KJWG has largely been a forum for discussion and ideas. As diverse and productive as the KJWG discussions have been, dialogue around what a just transformation in agriculture is and how it is achieved has been incomplete. Post-Koronivia there is undoubted pressure to convert discussion into implementation and action, but there is a danger that this implementation phase becomes oriented along conventional “green revolution”-type agricultural development lines, focusing on the adoption and upscaling of agricultural technologies and practices, rather than on addressing historical, representative and distributive injustices, and their underlying causes.

“Determining the next steps for agriculture while building on the work done so far is crucial to ensure the practical implementation of KJWA outcomes… KJWA will only be a true success if and when it creates the conditions to deliver concrete actions that benefit and strengthen the resilience of those most vulnerable while protecting the environment we all depend on” (Drieux et al., 2021, p. 17).

Throughout the KJWA, Parties and Observers have continuously stated and agreed upon the need for robust, ambitious and urgent climate actions for mitigation, adaptation, and adaptation co-benefits for agriculture and food systems transformation. Particularly in the final 6 months of KJWA, Parties requested that the Koronivia process turn discussions into concrete actions at national and global scales, and during intersessional workshops held in June 2021 as part of the UNFCCC workshops toward COP 26 Parties proposed that “implementation” became one of the recurrent terms of future dialogues. The language of implementation is purposeful evident throughout the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation, and its objectives are largely action-oriented, aiming for greater integration of agriculture into the workstreams and operational mechanisms (particularly around finance) of the UNFCCC and the development and monitoring of national policies and plans.

It is broadly recognized that there is still much to be negotiated over competing visions for future agricultural systems and the ways in which agro-climatic impacts, adaptations and mitigation should be reflected and integrated within the Articles of the Paris Agreement and in national commitments. There is a need, for example, for discussions and decisions about how loss and damage in agriculture is defined and how these are compensated for, under Article 8 of the Paris Agreement (and operationalised through the newly agreed Loss and Damage fund). However, there has also been a much-voiced sense of urgency in the need to move beyond negotiation toward the implementation of actions that will enhance the climate resilience and climate smartness of agriculture on the ground. In the elements for a draft COP decision on Koronivia collated at Bonn in June 2022 include the potential recommendation that the UNFCCC Parties:

“Emphasize the urgency of scaling up action and support, including finance, technology development and transfer, and capacity-building.”

[Excerpt from Enhanced consideration and implementation of elements related to agriculture—Elements of a Draft COP Decision (SBSTA/SBI, Bonn, June 2022)].

Importantly, the recommendations of Koronivia are not limited to the mainstreaming of agriculture within the framework convention but focus more systemically on the imperative of creating enabling environments for implementation, within and beyond the governance and jurisdiction of UN member states. To this end, KJWA presents itself a powerful coalition of ideas, actors, and enables, coalescing around a shared vision of climate smart agricultural transformation.

As Blythe et al. (2018) points out, one of the latent risks of transformation discourse is that the imperative to see up-scaled change is prioritized over the mechanisms, governance, and politics of such change. Arguably, one of the reasons why KJWA has been silent on issues of loss and damage is that they are too political and difficult to reach consensus around. There is a danger that in emphasizing the importance of implementation finance and technology transfer that certain actors and perspectives have a privileged position in the bringing about of agricultural transformation and that historical power asymmetries are reinforced. Propositions of knowledge and technology transfer and participation of certain actors like the private sector in the climate change context can reinforce the dominance of capital, continuance of classic economic models and neocolonial processes that have so far created a dependency model of development in the Global South, and exacerbated gender and social inequalities. As Koronivia moves toward an implementation stage, it is arguably even more important than ever there is an acknowledgment of the historical injustices brought about through past technology-transfer centric green revolutions and more important than ever that different perspectives and knowledges are identified and represented in the visioning and governing of agricultural transformation. It is important that in the imperative to move to implementation, and to produce consensual general statements, the focus does not become too technocratic and that the contributions on justice (however fleeting, and however implicit/indirect they have so far been) are not set aside.

It would be easy to write off this discussion of justice and equity as overly theoretical or discursive, to be set aside once the real work of implementation kicks in. However, we argue that distributional, historical, and representational justice should be fundamental guiding principles, embedded within action plans, compensatory mechanisms, and financial agreements, and our concern is that they have not yet been well enough established and agreed upon through KJWA to serve as such.

We propose that the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation is used as opportunity to better address the issues of justice and agricultural transformation that have been underserved within Koronivia. Among other things, this might include:

• Identifying governance and representation in agricultural transitions becomes as a core agenda item of the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation to allow space for a broader consultation with, and about, whose voices are represented in agricultural governance and why. This should include the development and incorporation of monitoring and evaluation tools for the Implementation Plan that capture representation, and more institutional and structural perspectives on transformation, in an authentic way.

• Translating the explicit acknowledgment in the first objective of the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation that “adaptation is a priority for vulnerable groups, including women, indigenous peoples and small-scale farmers” into an emphasis on social equity within national policies and strategies and the targeted prioritization of transformation strategies, safety nets and support that redresses distributive injustices.

• Using the opportunity presented by the coincidence of the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation and the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund (and operationalization of the Santiago Network) under the UNFCCC, for integrating these processes. This in turn could manifest in an effort to better unpack the ways in which historical injustices are experienced within agriculture and food systems and to design compensatory mechanisms that redress these.

Although we do not dispute the need for implementation and action, we argue that there is a need for continued and ongoing dialogue within the UNFCCC, through the Sharm El-Sheik Joint Work on Implementation, around the meanings of and mechanisms for achieving social justice in agriculture and food system transformation.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

RS collated, screened, and organized the data. RS, MT, and SW jointly analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the UK Universities Climate Network's COP26 Fellowship Programme and by a grant from the UK Research and Innovation's Global Challenges Research Fund (EP/T02397X/1).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1033152/full#supplementary-material

Anderson, C. R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M. J., Kiss, C., and Pimbert, M. P. (2019). From transition to domains of transformation: getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability 11, 5272. doi: 10.3390/su11195272

Anderson, M., and Leach, M. (2019). Transforming food systems: the potential of engaged political economy. IDS Bull. 50, 131–146. doi: 10.19088/1968-2019.123

Bennett, N. J., Blythe, J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Singh, G. G., and Sumaila, U. R. (2019). Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability 11, 3881. doi: 10.3390/su11143881

Bezner Kerr, R., Hasegawa, T., and Lasco, R. (2022). “Food, fibre, and other ecosystem products climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability,” in Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press), 713–906.

Blythe, J., Silver, J., Evans, L., Armitage, D., Bennett, N. J., Moore, M. L., et al. (2018). The dark side of transformation: latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode 50, 1206–1223. doi: 10.1111/anti.12405

D'Alisa, G., and Kallis, G. (2020). Degrowth and the state. Ecol. Econ. 169, 106486. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106486

Drieux, E., Van Uffelen, A., Bottigliero, F., Kaugure, L., and Bernoux, M. (2021). Understanding the Future of Koronivia joint Work on Agriculture. Rome: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis and critical policy studies. Crit. Policy Stud. 7, 177–197. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2013.798239

Hölscher, K., Wittmayer, J. M., and Loorbach, D. (2018). Transition versus transformation: what's the difference? J. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 27, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007

Janks, H. (1997). Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 18, 329–342. doi: 10.1080/0159630970180302

Jasanoff, S. (2018). Just transitions: a humble approach to global energy futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 35, 11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.11.025

Kates, R. W., Travis, W. R., and Wilbanks, T. J. (2012). Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7156–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115521109

McShane, T. O., Hirsch, P. D., Trung, T. C., Songorwa, A. N., Kinzig, A., Monteferri, B., et al. (2011). Hard choices: making trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biol. Conserv. 144, 966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.038

Newell, P., and Taylor, O. (2018). Contested landscapes: the global political economy of climate-smart agriculture. J. Peasant Stud. 45, 108–129. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2017.1324426

Nightingale, A. J. (2017). Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum 84, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.011

Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. (2019). Combining feminist political ecology and participatory diagramming to study climate information service delivery and knowledge flows among smallholder farmers in northern Ghana. Appl. Geogr. 112, 102079. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.102079

Patel, R. (2013). The long green revolution. J. Peasant Stud. 40, 1–63. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.719224

Pereira, L. M., Karpouzoglou, T., Frantzeskaki, N., and Olsson, P. (2018). Designing transformative spaces for sustainability in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 23, 32. doi: 10.5751/ES-10607-230432

Rice, M. J., Apgar, J. M., Schwarz, A. M., Saeni, E., and Teioli, H. (2019). Can agricultural research and extension be used to challenge the processes of exclusion and marginalisation? J. Agric. Educ. Extens. 25, 79–94. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2018.1529606

Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G., Mazzucato, M., Messner, D., Nakicenovic, N., and Rockström, J. (2019). Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sust. 2, 805–814. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9

Schot, J., and Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). New directions for innovation studies: missions and transformations. Res. Policy 47, 1583–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.014

Scoones, I., Stirling, A., Abrol, D., Atela, J., Charli-Joseph, L., Eakin, H., et al. (2020). Transformations to sustainability: combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 42, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004

Stirling, A. (2015). “Emancipating transformations: from controlling ‘the transition’to culturing plural radical progress 1,” in The Politics of Green Transformations, eds I. Scoones, M. Leach, and P. Newell (London: Routledge), 54–67. doi: 10.4324/9781315747378-4

Tavenner, K., and Crane, T. A. (2019). Beyond “women and youth”: applying intersectionality in agricultural research for development. Outlook Agric. 48, 316–325. doi: 10.1177/0030727019884334

UNFCCC (2022) Joint work on implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security Proposal by the President, Draft decision -/CP.27. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/documents/624317.

UNFCCC (n.d.). Paris Agreement: What is the Paris Agreement. UNFCCC. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

UNFSS (2021). United Nations Food Systems Summit. United Nations. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit

von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L., Hassan, M., and Torero, M. (2021). “Food systems–definition, concept and application for the UN food systems summit,” in Food Systems Summit Report Prepared by the Scientific Group for the Food Systems Summit (UN Food Systems Summit).

Wezel, A., Herren, B. G., Kerr, R. B., Barrios, E., Gonçalves, A. L., and Sinclair, F. (2020). Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agron. Sus. Dev. 40, 40. doi: 10.1007/s13593-020-00646-z

Whitfield, S. (2015). Adapting to Climate Uncertainty in African Agriculture: Narratives and Knowledge Politics. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315725680

Whitfield, S., Apgar, M., Chabvuta, C., Challinor, A., Deering, K., Dougill, A., et al. (2021). A framework for examining justice in food system transformations research. Nat. Food 2, 383–385. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00304-x

Keywords: UNFCCC, climate change, food systems transformation, social equity, just transition, agricultural systems

Citation: Sarku R, Tauzie M and Whitfield S (2023) Making a case for just agricultural transformation in the UNFCCC: An analysis of justice in the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:1033152. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.1033152

Received: 31 August 2022; Accepted: 12 December 2022;

Published: 04 January 2023.

Edited by:

Tek B. Sapkota, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, MexicoReviewed by:

Shreya Some, Ahmedabad University, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Sarku, Tauzie and Whitfield. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephen Whitfield,  cy53aGl0ZmllbGRAbGVlZHMuYWMudWs=

cy53aGl0ZmllbGRAbGVlZHMuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.