95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

EDITORIAL article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. , 04 January 2022

Sec. Agro-Food Safety

Volume 5 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.812955

This article is part of the Research Topic Food Security and Food Safety Challenges in Venezuela View all 11 articles

Editorial on the Research Topic

Food Security and Food Safety Challenges in Venezuela

Venezuela has suffered a massive shift in status. Once considered an affluent nation with the largest proven fossil-fuel reserves in the world, and classified as an upper-middle income country, declines in oil production, fuel availability and flawed macroeconomic decisions, disrupted all sectors of the economy. A large proportion of the population had ready access to food, health services, clean drinking water, sanitation, domestic gas, electricity, fuel, and transport, but declines in food production, real income, and living conditions have generated malnutrition and food insecurity, forcing complex survival strategies. All this gave rise to a humanitarian space.

In 2019, this space was expanded through the installation of the international humanitarian coordination architecture of the UN. Under the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), a country team and eight clusters were established: food security/livelihoods; water/sanitation/hygiene; education; nutrition; health; protection; shelter/energy/non-food items and logistics. OCHA indicates the humanitarian situation has not abated following six consecutive years of economic contraction, inflation/hyperinflation, political/social/institutional tensions, the COVID-19 pandemic and international sanctions1.

According to The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) people continue to leave the country to escape violence, insecurity, and threats as well as a lack of food, medicine, and essential services, becoming one of the largest displacement crises in the world, with 5.9 million seeking better conditions elsewhere2.

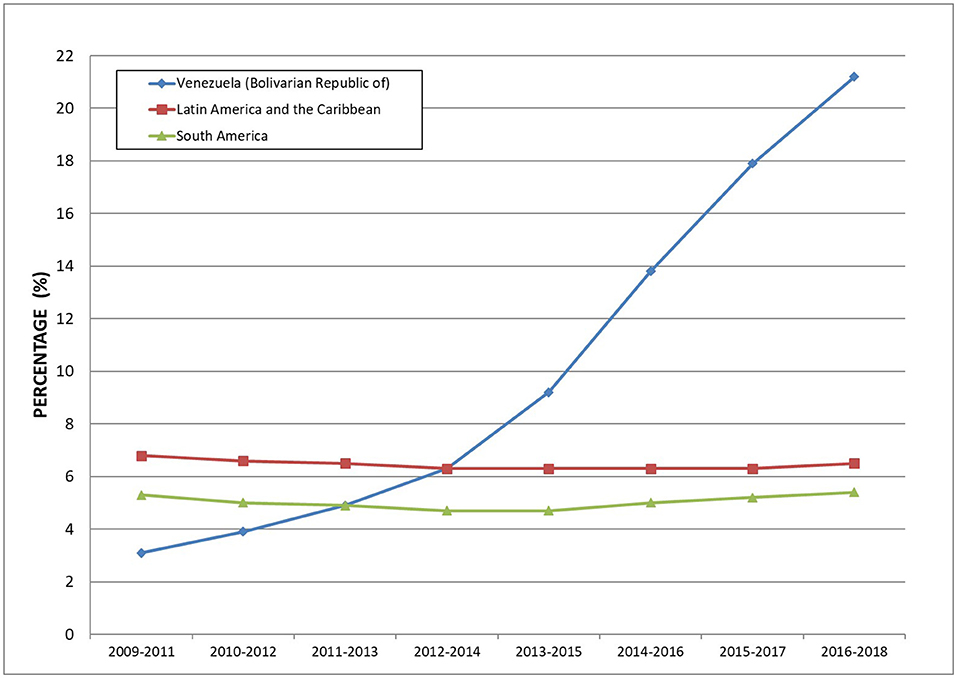

The prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) has increased almost 4-fold: from 6.4% in 2012–2014 to 21.2% in 2016–2018 (Figure 1). During the same recession period, reported inflation reached circa 10 million percent and growth in the real GDP worsened, going from negative 3.9 percent in 2014 to an estimated negative 25 percent in 2018 (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2019). Figure 1 shows a sustained increase in PoU since 2009. This would appear to repudiate, or at least not corroborate official claims attributing PoU to sanctions in place since 2017.12

Figure 1. Prevalence of undernutrition. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (2009–2018 in 3-year periods). Adapted from FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (2019). 2018 estimates in the 2016–2018 3-year averages are projected values.

In 2019, the World Food Program estimated that 7.9 percent of the population (2.3 million) was severely food insecure and 24.4 percent (7 million) moderately food insecure. One out of three Venezuelans (32.3%) was food insecure and in need of assistance3.

Analyzing food and nutrition security (FNS) in Venezuela is an arduous task due to the lack of official information. The scientific and academic community, NGOs, and consultants, have therefore committed to collect information on FNS (Tapia et al., 2017). This is the case of this Research Topic.

Ten articles are published in the following order:

Rodríguez García article on “Food Security in Venezuela: From Policies to Facts” uses the Venezuelan experience to draw attention to the fact that decreeing many laws and regulations related to food and nutrition is not enough to guarantee the right to food.

Moreno-Pizani in “Water Management in Agricultural Production, the Economy, and Venezuelan Society” analyses the mismanagement of water as a fundamental resource for production, economy, and society. Despite abundant water resources, serious problems affect the Venezuelan food production system (irrigation infrastructure, low availability of water in production processes, and decreased electricity generation).

Hernández et al. in “Dismantling of Institutionalization and State Policies as Guarantors of Food Security in Venezuela: Food Safety Implications,” use the Venezuelan case to illustrate how the food safety and security infrastructure of a country laboriously established over a century can be undermined and dismantled in a disproportionately short number of years.

“Assessment of Malnutrition and Intestinal Parasites in the Context of Crisis-Hit Venezuela: A Policy Case Study” by Mejias-Carpio et al. take a rational approach to international recommendations for countries in crisis, applying them to the alarming resurgence of intestinal parasites related to poverty and anemia which are aggravating the health and nutritional status of Venezuelan children.

Herrera-Cuenca et al. in “Challenges in Food Security, Nutritional, and Social Public Policies for Venezuela: Rethinking the Future,” intend to conceptualize a public policy model that analyzes current food security, nutrition, and social indicators.

Raffalli and Villalobos in “Recent Patterns of Stunting and Wasting in Venezuelan Children: Programming Implications for a Protracted Crisis,” show how the protracted humanitarian crisis has significantly impacted child growth, based on assessment of the patterns of wasting and stunting and their concurrence among vulnerable children through anthropometric records captured by Caritas Venezuela.

In “Ethics and Democracy in Access to Food. The Venezuelan Case,” Marrero Castro and Iciarte-García discuss the ethical dimension of the right to food under the premises of the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen that equate functional democracies and food security, demonstrating the relationship through the Venezuelan case.

Hernández and Camardiel in “Association Between Socioeconomic Status, Food Security, and Dietary Diversity Among Sociology Students at the Central University of Venezuela” found that sociology students who are food insecure are four times more likely to have a poor varied/monotonous diet.

Pico et al. address the migration crisis in "Food and Nutrition Insecurity in Venezuelan Migrant Families in Bogotá, Colombia” analyzing the changes in access, availability, and food consumption in Venezuelan migrants who arrive in Colombia as their first destination.

Finally, Marys and Rosales in “Plant Disease Diagnostic Capabilities in Venezuela: Implications for Food Security,” discuss how the growing problems in diagnosing, monitoring, and managing plant diseases in the country affect national food security (i.e., huanglongbing devastating our citrus industry).

This Research Topic represents an extraordinary opportunity to expose Venezuela's situation, considered unique in a country outside of war. It uses science-based analysis to explore how food systems can be affected by multiple factors and help establish a framework to address the issues that Venezuela is currently facing, and which other countries may confront in the future. We express our gratitude to Frontiers for their support.

MT prepared this Editorial. All authors revised and approved the submitted version of the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We express our gratitude to Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, to the Editorial Office and all the Frontiers team, to authors who contributed manuscripts to this issue and their institutions, and to the many reviewers and paper editors, who contributed their time and efforts to ensure the success and quality of the peer review process.

1. ^OCHA-UN. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/venezuela_humanitarian_response_plan_update_2021_june2021.pdf.

2. ^UNHCR-UN. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/venezuela-emergency.html (accessed November 4, 2021).

3. ^World Food Program-WFP-UN. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Main%20Findings%20WFP%20Food%20Security%20Assessment%20in%20Venezuela_January%202020-2.pdf.

FAO IFAD UNICEF, WFP WHO. (2019). Available online at: https://www.fao.org/3/ca5162en/ca5162en.pdf

Tapia, M.S., Puche, M., Pieterrs, A., Marrero, J. F., Clavijo, S., Gutiérrez Socorro, A. A., et al. (2017). Available online at: https://ianas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/fnb02c-1.pdf

Keywords: Venezuela, food security, food system, food safety, nutrition, prevalence of undernourishment, humanitarian emergency

Citation: Tapia MS, San-Blas G, Machado-Allison C, Carmona A and Landaeta-Jiménez M (2022) Editorial: Food Security and Food Safety Challenges in Venezuela. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:812955. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.812955

Received: 10 November 2021; Accepted: 09 December 2021;

Published: 04 January 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Delia Grace, University of Greenwich, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Tapia, San-Blas, Machado-Allison, Carmona and Landaeta-Jiménez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria S. Tapia, bXRhcGlhdWN2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.