- 1School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China

Australia has managed well through the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to many other developed nations. Through its first and second waves it was relatively successful in terms of control of outbreaks. Nevertheless, like everywhere, the shock to national systems has been profound, and adjustment remains complex and volatile. Food is a critical human need, and the food industry is recognised as a vital economic sector. We present an examination of some of the adaptive responses of Australia's food systems during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, from January 2020 to October 2020, with a focus on three case studies (seafood exports, consumer behaviour and food sector employment). These case studies provide observations of specific stresses experienced, as well as insights into the adaptation strategies carried out by various actors within the nation's food systems. The shock was experienced differently in different parts of given food systems, and the opportunities for adaptation varied. Some supply chains lost business, others had to adapt to rapidly increased demands, and surges. Our analysis reveals features of Australia's food systems, and their relationships to other systems, that have facilitated resilience, and features that have impeded it. We found that international supply chains are highly vulnerable to global shocks, that insecure employment conditions throughout the food system reduce the resilience of the system overall, and that consumers are not fully confident in supply chains. We observed the importance of agency and adaptive behaviour throughout the food systems as actors worked to build their own resilience, with consequences for other parts of the system. Our findings suggest that food system resilience can be enhanced by ensuring that the goals and priorities of those most vulnerable in society are recognised and addressed within decision making processes throughout the system.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, and related policy responses, have revealed many previously under-recognised dependencies and vulnerabilities in Australia's society and economy, as elsewhere (Devereux et al., 2020; Dou et al., 2021; Love et al., 2021). The food and nutrition security of Australians is among the many aspects of society impacted by the sudden shock posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. While in general Australians are perceived to enjoy a high level of food security (Australian Bureau of Agricultural Resource Economics Sciences, 2020), the pandemic and associated government, industry and community responses have revealed both vulnerabilities and adaptations, and signs of resilience, in our food system. We have seen supermarket shelves emptied repeatedly due to panic buying (Sakzewski, 2020), shortage of farm labour (Sullivan, 2020b) due to restrictions on movement, and disruption of international trade (Pollard and McKenna, 2020), for example. These are to some extent associated with food production, but are most evident with food distribution and consumer behaviour. The important connections between production, distribution and consumption can be made transparent by applying a food systems approach (Ingram, 2011), going beyond a focus on agricultural production or agricultural systems, to the issue of food and nutrition security. Adding a resilience approach enlightens a focus on the ability of the food system to cope with a major disturbance and adapt while under duress.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides an extraordinary opportunity to “observe” while experiencing a set of complex adaptive systems – Australia's food systems – at a critical point when a major disturbance occurs. Sudden external shocks to food systems, like the COVID-19 global pandemic, are unanticipated or unforeseen disturbances that are complex and difficult to study and have the potential to trigger large unpredictable and synchronous impacts throughout whole food chains, across multiple sectors and at local and global scales (Béné, 2020; FAO, 2020; Love et al., 2021; White et al., 2021). Prior to COVID-19, these shocks have typically been events with more local impacts on production, due for example to extreme weather events or natural disasters (e.g. floods, droughts, cyclones, extreme fires), pest invasions and noxious diseases, or other environmental disasters (e.g. algal blooms or prolonged over-fishing causing a collapse of fisheries) (Cottrell et al., 2019; Stoll et al., 2021). As food systems become more globalised, increasingly geopolitical events are exposing countries to external shocks (including international trade disputes, global financial system collapses, violent conflicts) (Crona et al., 2015; Gephart et al., 2016), while often highlighting current injustices in food systems such as household food insecurity, and exacerbating existing poverty and inequalities (Sanderson et al., 2021). Complex adaptive systems theory (Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Chapin et al., 2009) explains how a major shock may cause a given system to adapt and reorganise (demonstrating resilience) or transform. It also explains how adaptation promotes learning in order to build robustness against future shocks of the same or different types (Love et al., 2021). This reorganisation process occurs through complex interactions at multiple levels within the system (Béné, 2020).

Emerging literature on food systems and their resilience under COVID-19 has offered international overviews conducted early in the pandemic by Devereux et al. (2020), Love et al. (2021) Bisoffi et al. (2021), and a special issue of Agricultural Systems (Stephens et al., 2020) that incorporates observations and perspectives from many countries in developed and developing regions including India, Nepal, Myanmar, Peru and other parts of Latin America, Africa, China, the Caribbean, USA and Canada. A study by Béné (2020) focused particularly on local food systems in the context of low and middle income countries. Meanwhile, Devereux et al. (2020) concentrated on household resilience in both developed and developing countries. A number of other country-specific studies include Amjath-Babu et al. (2020) on Bangladesh, Farrell et al. (2020) on the Pacific region, Bisoffi et al. (2021) for a global view, Davila et al. (2021) on the Pacific, and Fan et al. (2021) on Asia. These studies explore how and why consumer behaviour changed, and show how the supply chains adapted to the sudden changes in demand in a context of disrupted supply. Our analysis by contrast, focuses on a developed country, Australia, with relatively high food security prior to the pandemic (Snow et al., 2021; Whelan et al., 2021). Nevertheless in Australia there are vulnerabilities within its Indigenous populations and other low income sectors (Bowden, 2020; Foodbank, 2020; Fredericks and Bradfield, 2020a).

Our analysis treats the disruptions and adaptations caused by the pandemic as an opportunity to examine the resilience of Australia's food systems, and in so doing to add to the empirical literature on food systems and resilience (as called for by Choularton et al., 2015; and Tendall et al., 2015) in order to expand understanding of both food system behaviour, and resilience under an unusual type of disturbance (Berkes and Ross, 2016).

Beyond food systems, the pandemic is being seen worldwide as an opportunity for critical reflection on current economic systems and society, with a view to promoting resilience and environmental sustainability over narrowly conceived notions of economic efficiency (IPES-FOOD, 2020). Nevertheless some see the pandemic as a temporary disruption of “business as usual” and expect our economic systems and society to “bounce back” to normal after the pandemic has been resolved (Wells et al., 2020). By combining the food systems framework with a resilience perspective, we identify how actors within Australia's system exhibit agency to respond to shocks, and adapt, and so present insights into how food systems are reorganising.

The following section explains our conceptual framework, combining the concepts of food systems and resilience. This is followed in subsequent sections by our methods, background to the COVID-19 health shock in Australia, the set of case studies, and discussion of key outcomes and implications.

Conceptualising Food Systems and Resilience

In order to explore the disruptions imposed by COVID-19 on Australia's food systems, and consequent adaptive behaviour, our research joins two key framings. First, a food systems approach recognises drivers, activities and outcomes across the whole food system (e.g. from production to consumption), with a focus on the range of emerging interactions, feedbacks and their effects (Tendall et al., 2015; Béné, 2020) rather than on detailed characteristics of separate parts of the system. Second, a resilience framing is added to understand how food systems react and respond to shocks and stresses and to observe the enhanced dynamics of the impacts (Tendall et al., 2015).

Framing Food Systems

Our choice of a food systems framework is that developed by The Global Environmental Change and Food Systems (GECAFS) project (Ingram, 2011). A key innovation of this framework is the explicit distinction and integration of food system activities (what we do: producing, processing, distributing, retailing, and consuming food) with drivers of the food system, which can be biophysical or socioeconomic (Ingram, 2011; HLPE, 2020), and outcomes in terms of what we get: food security (determined by people's access, availability and use of food), environmental welfare and socioeconomic welfare (Figure 1). Recently, the FAO's High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on food security introduced “agency” as a further dimension of food security (HLPE, 2020). We recognise a fourth outcome category, “public health”, to emphasise the importance of food systems in diet and nutrition including the fight against obesity. The HLPE (2020) variant of this framework places emphasis on policy and governance throughout the system.

Figure 1. A framework for food systems research emphasising Drivers, Activities, and Outcomes (Ingram, 2011, p. 421).

The integrated GECAFS/HLPE framework thus positions food security as the key outcome of a complex adaptive system (Preiser et al., 2018), with other important outcomes including the jobs, livelihoods and businesses dependent on the food system (social welfare), and the environmental consequences of food systems (environmental welfare). The distinction between activities and outcomes assists in targeting interventions to specific activities in order to realise desired outcomes. The framework accommodates feedbacks, trade-offs, and interactions between activities, outcomes and drivers (Ericksen, 2008). For example, the “green revolution” in agriculture, an intervention designed to improve food security through increased crop production, has been detrimental in terms of impacts on ecosystems and health (John and Babu, 2021).

While the food systems framework emphasises multiple interactions, it requires an emphasis on how those interactions contribute to resilience, an important property of complex adaptive systems. The following section thus introduces a resilience framing to enhance the food system framing.

Framing Resilience

Our resilience framing is based on principles widely recognised in the social-ecological systems literature (Berkes et al., 2003; Béné et al., 2016; Béné, 2020), in which the paradigm of complex adaptive systems is paramount. We also draw on other fields contributing resilience theory relevant to our theme of food systems: people-environment relationships (social-ecological resilience), business and organisational resilience, and personal psychological coping (psycho-social resilience). Each of these fields identifies different features as contributing to resilience, including systemic interactions (Hertz et al., 2020), agility (Linnenluecke, 2017), and self-organisation and agency (Berkes and Ross, 2013).

The concept of resilience focuses on ability to contend with shocks (also referred to as disturbances or perturbations) and stressors. Resilience is seen as an unfolding emergent phenomenon and as a capacity and process as much as an outcome (Southwick et al., 2014).

Helfgott (2018, p.854) defines resilience as “a property of a system that describes the nature of the response of the system to a particular disturbance, of a particular magnitude, from the perspective of a particular observer over a specified timescale”. She focuses attention on the resilience “of what” (in our case, outcomes of Australia's food system, i.e., food security), “to what” (in our case this is the pandemic and policy and practice changes involved in contending with it), “for whom” (whose interests are to be considered), and “over what timeframe”. In considering “for whom”, power relationships, and hence whose interests are considered important within a food system, are made apparent (Herrera, 2017). Resilience is partially subjective: people may be their own best judges about their own resilience and that of the systems they know well (Jones, 2019).

Much literature (such as Béné, 2020) differentiates the concept of “adaptive capacity”, the capabilities that will position people or relevant parts of a system to adapt after a shock (such as after the COVID-19 outbreak occurs), from the process of responses and recovery outcomes involved in generating resilience.

Processes of building resilience are non-linear. Resilience status at any particular point in time may differ later, and the system or person is likely to have to address other, subsequent shocks over time. A person (Masten and Obradovic, 2006; Liu et al., 2017) or system (Berkes et al., 2003) may become more resilient after experiencing a few shocks, but then be set back or become more easily disturbed by subsequent shocks. Further, there is a relationship between resilience (which may or may not be desirable, in itself) and transformation to more desirable structures (Elmqvist et al., 2019).

Resilience is a multi-level and cross-scale phenomenon, in which interactions by individuals, households, communities, sectors, regions, nations may affect their own resilience and that at other levels in the same system (Berkes and Ross, 2016). Components in the food systems framework thus need to be considered as interacting at multiple levels whereby the many adaptations of actors to repeated changes in their part of the system affect one another. The relationships between levels within a system are not neat: they can be mutually supportive towards resilience or not (Leite et al., 2019). They can be indirect, for example where a pandemic jumps from the local to the global level, bypassing other levels (Berkes and Ross, 2016). Food supply chains are inherently multi-level phenomena, connecting producers to consumers through multiple activities performed by individuals, households and firms, which have local, regional and global effects.

Diversity within complex adaptive systems, including food systems, is a source of resilience since it offers multiple pathways for adaptation during and after shocks (Lade et al., 2020). While connectivity within a system is highly important (Ungar, 2018), it is necessary to beware of “path dependencies” that create rigidities within a food system which can limit adaptive capacity and hence resilience (Wilson, 2014).

The agency (Davidson, 2010; Berkes and Ross, 2013; Béné et al., 2016) of actors within a system also contributes to resilience, as they work proactively to adapt amidst their changing circumstances. New patterns and solutions to problems emerge as their initiatives interact. This is closely related to self-organisation, often a collaborative process. Supply chain governance (Boström et al., 2015), oriented to goals such as sustainability and potentially resilience, is a prime example of self-organising and agency in food systems. Agency is now recognised as an important dimension of food security, and thus to food system resilience (HLPE, 2020).

Food System Resilience

Advancing on these separate and generic framings of food systems, and of resilience, Tendall et al. (2015) have developed a conceptual framework specifically for food system resilience. Like us, they view food systems as a type of social-ecological system, involving the range of activities and outcomes identified in the food system framework reviewed above. They emphasise the need to move beyond particular components, or particular processes within food systems, to understand the complex cross-level interactions involved in any social-ecological system. Accordingly, they define food system resilience as “capacity over time of a food system and its units at multiple levels, to provide sufficient, appropriate and accessible food to all, in the face of various and even unforeseen disturbances” (p. 19). They emphasise behaviour over time, at multiple levels in a system, so that initial reactive action (to absorb, react and restore) translates towards preventive action, focused on learning and building robustness. Love et al. (2021, p. 2) elaborate on this idea to argue that this building of robustness should be towards generalised, rather than specified, resilience, to cater for multiple and cumulative other stressors such as climate change, natural disasters, political and economic instability, resource management issues, and shortcomings in governance. Where considerable literature in the field of social-ecological systems refers generically to “adaptive capacity”, Tendall et al. differentiate resilience as involving different capacities over time after a disturbance, from initial robustness to withstand the stress, to capacities to absorb - in which redundancy is a useful characteristic – to resourcefulness and continuing adaptability. Flexibility supports the speed at which losses in food security can be overcome. Interventions in a food system under duress may have beneficial effects on system adjustment.

Tendall et al. (2015) identify three particular “entry points” for a whole system resilience-building process. National or regional food systems, involving multiple supply chains, are important to policy makers and governments, attentive to food security for their populations. Individual food supply chains, at any level from local to international (cf Love et al., 2021 on seafood) interest specific value chain actors, while individual perspectives include smallholder livelihoods, household food security (cf. Devereux et al., 2020), and the health of consumers.

Devereux et al. (2020) argue that the issues presented by COVID-19 are best addressed by joining several frameworks. They combine the food systems frameworks we use (especially the latest elaboration, HLPE, 2020) with the FAO's “four pillars” approach to food security (availability, access, utilisation and stability), and a social justice perspective on “entitlement” based on Sen, which resonates with Helfgott's (2018) later focus on “for whom”.

Methods

This qualitative analysis has been conducted by a group of university colleagues engaged in the study of food systems, resilience, and people-food-environment relationships. We are interdisciplinary social and environmental scientists, some also having qualifications in agricultural sciences. The first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, as experienced in Australia, provided an opportunity to observe the immediate impacts of the pandemic on the food system through media and other sources that were readily available online. Aligning with a participant observation approach, the research team was able to observe the pandemic while they participated in daily life (Denscombe, 2007) as the situation unfolded. As participant observers within a pandemic situation, our team observed food system disturbances that happened in situ (such as changes in the access, use and availability of certain food items). We thus identified key disturbances that took place within Australia's food systems that emerged through our lived experience of the pandemic by directly observing daily life.

These observations were complemented with an online ethnographic approach. Instead of a systematic literature review, we used an online ethnographic method (Underberg and Zorn, 2014; Varis, 2016) to treat online resources as information resources, or “vessels” (Coffey, 2014). These resources were used to analyse how the pandemic was affecting food system activities and outcomes that emerged through our participant observations as “promising lines of inquiry”. We acquired data from diverse sources from across the food chain as impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded. These included news media reports, the grey literature (e.g. technical reports, quality newsletters, working papers, policy statements and other documents and databases published by governments (e.g. the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, ABARES), research organisations (academic reports, newsletters and magazines, including the Fish R&D Corporation) as well as other new academic literature. In terms of news media, we relied on reputable journalism sources that covered the COVID-19 pandemic on a national rather than a local scale, namely the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (online, radio and TV), The Guardian and The Conversation. This was to ensure that the issues we focused on were relevant to the broader Australian food system context, rather than being localised.

A real-time perspective was taken to build the process of the unfolding impact of COVID-19 on the Australian food system, in which we employed a multi-step analysis of important events. In this multi-step analysis we identified events, co-constructed emerging case studies, interpreted themes in these case studies and finally analysed these themes in relation to our original framework and research question. First, beginning in March 2020, information was collected daily from different sources (such as newspapers and social media) and notes were taken with regard to events that we thought would be able to give us insight with regard to the impact of COVID-19 on Australia's food systems. Events that were discussed as a team included – but were not limited to – panic buying, shortages of certain items in supermarkets, supply problems, agricultural produce going to waste due to labour shortages or transport issues, citizens buying seeds and chickens, and export issues. Second, these notes were discussed weekly and patterns started to emerge over time. We noticed patterns around export of fresh produce, most noticeably in the seafood sector, consumer behaviour and farm employment. Third, we developed each of these themes into mini-case studies that illustrated the patterns that we were observing and which represented different parts of the food systems analytical framework. We synthesised the diverse acquired data and information to address the following questions:

1. How and why has this part of the Australian food system and its related food chain been impacted by the COVID-19 shock, both in the short and longer term?

2. What types of response have occurred in reaction to COVID-19 impacts?

3. What actions if any are being taken to restore Australia's food system and food chain functions?

Fourth, we then reflected on the implications of these results in terms of what this could tell us about Australia's food system and adaptations, and to generate insights into ways of improving it for future resilience and equity. We reflected on how specific disruptions, impacts and responses to the pandemic across food system supply chains are altering food system dynamics and resilience.

A brief description of how the pandemic played out within Australia follows, as background to the case studies.

Background: Australia's Response to COVID-19

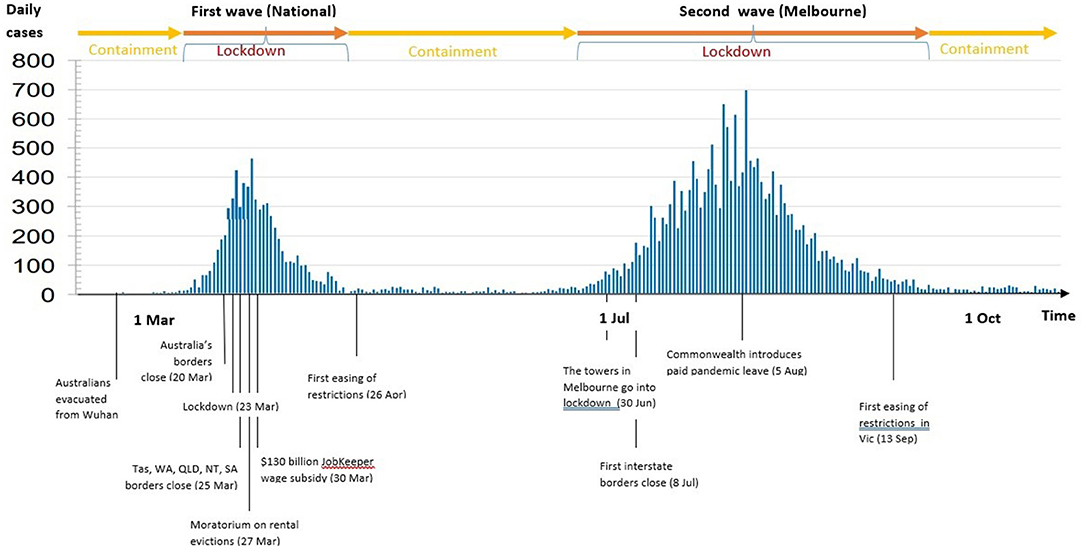

For at least the first year of the pandemic, Australia's response to the COVID-19 health crisis was considered to be among the most successful in the world (Duckett and Stobart, 2020a; Mercer, 2020; Patrick, 2020), compared to international standards. In a population of just over 25 million (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021), there were 27,590 confirmed cases and 907 deaths (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021). Following Duckett and Stobart (2020b,c) we provide a summary of events for the period January to early November 2020.

The first cases of COVID-19 in Australia were reported in late January 2020 among travellers arriving from China, prompting travel restrictions on those allowed to enter Australia (Figure 2). As the virus spread rapidly in other parts of the world, community transmission was first detected in early March. This led consumers to panic buy toilet paper and other groceries (Davey, 2020; Duckett and Stobart, 2020c; Smith and Klemm, 2020), as the population feared Australia might be facing a similar crisis to that experienced in other parts of the world.

Figure 2. Timeline of COVID-19 cases reported in Australia (Infogram, 2021). Adapted from Duckett and Stobart (2020c).

There were calls to introduce strict restrictions early to minimise harm later (Duckett and Stobart, 2020c). A set of measures restricting movement of people was introduced by the Australian government from mid-March onwards and two weeks later, the country moved into a total lockdown (Biddle et al., 2020b), closing its border to international travellers on 20 March 2020. Social gatherings were limited to two people, social distancing was introduced, non-essential travel was prohibited, people were urged to work from home if possible and schools were closed. Most states closed their interstate borders and lock-down restrictions were enforced with heavy fines. The Australian government introduced two large economic support packages: a doubling of the “JobSeeker” unemployment benefit payment (22nd of March, 2020) and a “JobKeeper” wage subsidy program to keep people connected to their employer while unable to work (30th of March, 2020). Free childcare was provided to support parents and centres, and the Australian government imposed a moratorium on rental evictions for tenants experiencing hardship (Duckett and Stobart, 2020c; Wahlquist, 2020).

By the beginning of May 2020, there were fewer than 20 new COVID-19 cases per day and in some states the rate had dropped to zero for several days (Ting and Palmer, 2020). When Australia had “flattened the curve” successfully, the federal government revealed a roadmap to lift COVID-19 restrictions, shifting the political discourse from “prevention of COVID-19 health risks” to “reopening of the economy” (Duckett and Stobart, 2020b).

A second wave of COVID-19 cases began in Melbourne in late June 2020, characterised by community transmission (Duckett and Stobart, 2020b). Contact tracing was not working as expected (Taylor, 2020), and people without entitlement to sick leave in lower paid, insecure jobs were unable to stay at home when unwell, thereby spreading the virus through workplaces (Duckett and Stobart, 2020b; Seneviratne, 2020). In the aged care sector, some carers worked across multiple nursing homes, exposing a highly vulnerable group of people to the virus (Judd and Taylor, 2020). In late July, paid pandemic leave was introduced but this was too late to stop the spread of the virus (Karp, 2020). By the beginning of August 2020, around 900 people in nursing homes had been infected with the virus, with a high mortality rate. The government of Victoria announced a six-week full lockdown for Melbourne and a partial lockdown for the rest of the state (Duckett and Stobart, 2020b). The restrictions were enforced by police and the army, including home checks. Fines for breaking the rules were very high (Cave, 2020). The other Australian states watched the crisis in Victoria unfold and kept their borders closed. This had the intended result and infection rates declined. By mid October 2020 the number of cases had dropped to single digit numbers and Melbourne had successfully controlled the second wave (Mercer, 2020).

The factors that contributed to Australia's successful control of COVID-19 under its first two waves are complex, but the lockdown, the strict border restrictions and public compliance with spatial distancing rules were important (Duckett and Stobart, 2020a). These authors also highlight how cross-sectoral and multi-level coordination also assisted, with a dedicated “National Cabinet” established comprising key federal, state and territory ministers, who worked closely with industry and the trade union movement. However, after JobKeeper, JobSeeker and the rental eviction moratorium expired near the end of March 2021, new hardships emerged for the small businesses, many of them food businesses, which were forced to close for varying periods, some permanently. Unifying public discourse, such as “we are all in it together”, obscured the structural and systemic inequities differentially affecting Australian society (Duckett, 2020). The end of the moratorium on rental evictions, for example, threw new people into financial and housing difficulty, while sporadic lockdown measures continued to have a significant economic and psychological impact (Foster and Hickey, 2020; Layard et al., 2020). As the pandemic continues to unfold social inequities persist.

Results

In each case study below we provide a narrative about the impacts of the pandemic on supply chains and other components of the food systems framework and describe adaptation responses of supply chain actors, government and other actors. We present three contrasting situations: seafood exports (an activity involving entire supply chains), consumer behaviour (an activity at the “downstream” end of supply chains), and food sector employment (both a facet of activities throughout supply chains, and a social welfare outcome that interacts with the three aspects of food security).

Case Study 1: Seafood Exports

Globally seafood is well recognised as a key component of a safe, nutritious, and affordable diet, and an important source of food security and employment (Crona et al., 2015; Tlusty et al., 2019; Havice et al., 2020; HLPE, 2020). Extending beyond the practices of fishers and the narrow scope of economic production factors, “seafood systems” are highly diverse and complex food systems encompassing many different processes, activities, value chains, and complex interactions and outcomes (Tendall et al., 2015; Béné et al., 2019), as illustrated in Figure 1. The multiple drivers of change and cross-level and cross-scale interactions, trade-offs, and feedbacks fundamental to seafood systems are commonly country specific (Tendall et al., 2015; Béné et al., 2019; Bennett et al., 2021).

In Australia, measures undertaken to address the flow-on impacts of the COVID-19 shock have affected all aspects of seafood systems, exposing pre-existing vulnerabilities and risks, in ways that no other previous shocks have done. Australia is a developed country and an isolated continent surrounded by over 10 million sq. km of ocean with abundant fishery resources (Patterson et al., 2020). This case study examines the impact of COVID-19 on Australia's seafood exports from January 2020 until June 2021, and the implications for food security in a developed country context at a time of an unanticipated shock.

With a growing demand for seafood globally, seafood accounts for 38% of total fish production entering international trade (FAO, 2020). As a natural resource, seafood is recognised as enhancing ocean health and economic production globally, but “fish as food” and its role and contribution to both food security and nutrition is largely neglected (Béné et al., 2015; Tlusty et al., 2019; Bennett et al., 2021).

Since the 1990s, increased urbanisation and rising living standards in Asia have created a growing demand for premium seafood products (such as lobster, abalone and salmon), to service high-end restaurants, cafes, and other food-service outlets. Australian seafood export businesses have exploited this opportunity, with the support of both state and federal governments. Pre-COVID-19, seafood exports to growing Asian markets accounted for half of Australia's total annual fisheries and aquaculture production by value (Mobsby et al., 2020). The highest valued export product is live wild-caught rock lobster, with China the dominant export market. The perishable nature of seafood requires specialised capital-intensive cold storage, processing, packaging, and distribution strategies and rapid transportation by air freight to maintain freshness and extend seafood life (Stevens et al., 2020). The premium price received for Australian live rock lobster trade to China relates to: a high quality product with high environmental certifications and traceability credentials; proximity to seafood markets in Asia; and the capacity to rapidly transport live highly perishable seafood safely and nutritiously (Mobsby et al., 2020; Stevens et al., 2020).

In late January 2020, one of the first impacts in Australia of COVID-19 was this lucrative seafood export trade to Asia. At the peak demand period of Chinese New Year, many Asian seafood markets and retail outlets were closed due to restrictions imposed by their governments on human movements and other interactions to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (Cartizone, 2020; Hendry, 2020; Major, 2020; Meachim, 2020; Pollard and McKenna, 2020). Demand in China for live wild-caught rock lobster plummeted overnight (Greenville et al., 2020; Hynninen, 2020; Liveris, 2020) with immediate feedback effects reverberating across Australia's seafood export system (Cartizone, 2020; Mobsby et al., 2020; Plaganyi et al., 2020; Pollard and McKenna, 2020). Amidst orders being cancelled and fears that oversupply would lower prices, the substantial Western Australian Geraldton Fisherman's Cooperative (WAGFC) immediately called a halt on live rock lobster deliveries to its storage facilities in Geraldton and Perth, by imposing a landing price of zero dollars per kilogram to send a signal to fishers that all trading of rock lobsters must stop (Liveris, 2020; Meachim, 2020). Live premium rock lobster now sold direct from fishers on social media or off the “back of boats” for half the price received the previous week for the same product (Meachim, 2020; Murphy, 2020). The WAGFC was left holding valuable and perishable stocks in overloaded storage facilities at considerable expense, with no immediate market, at what would normally be a peak time for this profitable trade (Liveris, 2020; Major, 2020; Meachim, 2020; Norgrady, 2020b; Pollard and McKenna, 2020).

In mid-March 2020, a second major disruption emerged due to the closure of Australia's national borders by federal and state governments to stem the spread of COVID-19 into Australia. Initially stopping only international passenger flights into and out of Australia (but not freight flights), the closures inadvertently also stopped Australia's live seafood export trade, which used international passenger flights (Bagshaw, 2020; Hayes and Daly, 2020; Hendry, 2020; Mobsby et al., 2020). State government lockdown measures closed internal borders creating bottlenecks for the movement of food products within Australia, as well as havoc for returning overseas boat crews trying to re-connect with fishing fleets around Australia (Cartizone, 2020; Collis, 2020). The situation was compounded by a dramatic drop in the number of international tourists visiting Australia, adversely affecting domestic wholesale and retail demand (such as restaurants, cafes, hotels, caterers) servicing the tourist industry (FRDC, 2020; Hayes and Daly, 2020; Meachim, 2020).

Initial COVID-19 impacts in Australia were thus sudden, unanticipated, and severe, varying considerably across different sectors of the seafood export systems. The Western Australian live rock lobster export industry, valued at about $AUD750 million annually, and relying almost exclusively (94%) on Chinese markets was particularly exposed (Mobsby et al., 2020; Stevens et al., 2020). By mid-2020, the annual production value for live rock lobster fell by 25% to $AUD544 million (Mobsby et al., 2021). Fisheries suffered a reduction in activity, while live seafood exports declined in both price and volume, although not all sectors and products were affected equally. Sectors adversely impacted were those exporting live product, supplying dine-in food service, reliant on international air freight, or affected by border closures, lockdowns, and other mobility restrictions (Greenville et al., 2020; Ogier et al., 2021). While the value of live rock lobster and abalone exports declined by 45%, other seafood sectors including businesses supplying domestic retail and take-away food service markets (which normally compete with international imports) experienced a rise in demand and price (Mobsby et al., 2021; Ogier et al., 2021).

Efforts towards adaptation were diverse, and involved significant self-organising among actors at multiple levels. A critical feature of Australia's initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic was the federal and state governments working together to overcome transport and logistical challenges. A key mechanism was an emergency airfreight subsidy scheme (Greenville et al., 2020; Sullivan, 2020c). Through the scheme, 200 charter flights of live lobster and abalone were exported to key markets in China, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore and the UAE (FRDC, 2020; Stevens et al., 2020). These flights involved freight sharing with other agricultural and mining industries or collaboration with carriers bringing cargo into Australia (such as medical supplies, respirators and other medical equipment to Australian authorities).

With contracts cancelled and a lack of export demand, many fishers were forced to dock their boats, shut down their businesses, and lay off staff (Hayes and Daly, 2020; Major, 2020; McKillop, 2020; Pollard and McKenna, 2020; Bagshaw, 2021). To stay in business, others adapted by exploring new export markets, diversifying their products, and attempting to pivot to the domestic market with new or alternative selling platforms, such as on-line consumer sales, internet selling, and home deliveries. Other examples include:

• When social distancing halved auction capacity, the Sydney Fish Market overhauled its wholesale auction system to provide remote on-line trading, proving a boon for exporters shifting to domestic sales by rapidly and efficiently connecting diversely located exporters to domestic markets (Boyer, 2020; Collis, 2020; Hynninen, 2020).

• A Torres Strait Island live rock lobster exporter to Asia shifted focus by repurposing its processing facility to export individually packed lobster tails to a new supermarket chain in Hong Kong (Plaganyi et al., 2020).

• Fresh packaged high-grade salmon and trout from Tasmania (usually destined for export to Japan), is now sold in large supermarket chains across Australia at much reduced prices (Nichols, 2020; Norgrady, 2020b).

• Mooloolaba Queensland seafood exporters adjusted their marketing strategies to more direct producer to consumer connections by setting up pop-up shop fronts or domestic retail outlets selling direct to local consumers (FRDC, 2020; Norgrady, 2020a).

Overall, slow demand in China, reduced air cargo capacity, and border closures led to a $AUD200 million drop in seafood export earnings in 2019-2020 (Mobsby et al., 2020). The immediate outcomes included: a reduction in fishing activity; loss of income in seafood export businesses; loss of employment throughout the seafood export chain; logistical transport and distributional bottlenecks; and ripple effects on supporting service industries throughout the economy (Pollard and McKenna, 2020; Prendergast, 2020). These impacts also affected other small businesses, rippling throughout the local community and all segments of the supply chain (Plaganyi et al., 2020).

While existing connections were disrupted, new connections also emerged to cope with changing demand and logistical issues. Digital technologies, for example, were key to establishing new marketing platforms providing rapid and efficient communication tools for managing the logistics of cancelled orders and border closures, connecting to new on-line wholesale auctions to ensure supply continuity, as well as facilitating the establishment of new markets and products.

COVID-19 severely impacted Australia's seafood export system by fuelling an economic slowdown of the national economy, disrupting food value chains and exposing underlying systemic vulnerabilities and risks. Paradoxically, it has also revealed emergent opportunities for adaptation and change (cf Stoll et al., 2021 for the United States of America and Canada). Three challenges for the future of seafood exports remain.

First is changing consumer preferences. Australia has ample supplies of safe healthy seafood (Australian Bureau of Agricultural Resource Economics Sciences, 2020) but despite producing substantially more seafood annually than Australians consume, over 65% of the seafood Australians consume domestically is imported from Asia, largely as low-valued processed products (Stevens et al., 2020). Over the last twenty years Australia has lost much of its seafood processing capacity because it does not compete well with the lower-cost offshore processing capacity of Asia (FRDC, 2020). Significant processing challenges emerged for the WAGFC in attempting to pivot away from the Chinese preferred live lobster export product to the Australian domestic market's preferred fresh cooked lobsters (Bagshaw, 2021). This has created a processing and marketing issue for the WAGFC as it does not currently have the right processing infrastructure to make the change (Seafood Industry Australia, 2021).

Second is the “creation of a gilded trap”. Over the last 30 years, globally there has been a dominant focus on economic efficiency and high connectivity for international markets via private sector corporate-dominated supply chains (Havice et al., 2020). This has led to intensification and simplification of seafood systems, often at the expense of seafood system diversity (Österblom et al., 2015; Folke et al., 2016). These industrial seafood systems are organised around continuous flow of product through global supply chains (Havice et al., 2020). They are highly interconnected and characterised by weakened internal feedbacks that may mask the signals of loss of resilience and make them vulnerable in the face of sudden global disruptions like COVID-19 (Nyström et al., 2019; Clapp and Moseley, 2020). The WAGFC, Australia's largest rock lobster processor, is an example of a highly successful large vertically integrated and connected commercial corporation owned by private fishers and tied to international markets. With 230 vessels harvesting seafood along 1,000 km of the Western Australian coastline, it operates as a sustainable quota-managed fishery connecting the entire supply chain (from fishing to international markets) and across multiple levels (from local to global) (Geraldton Fishermen's Co-Operative, 2021). With parallels to the iconic USA and Canada case of the Gulf of Maine lobster fishery (see Steneck et al., 2011; Folke et al., 2016), WAGFC's long term success in maximising abundance and economic value of the wild rock lobster has created a “gilded trap” highly vulnerable to disturbances. Lacking diversity of product as well as markets able to pay such high prices for rock lobster as China, COVID-19 has revealed the fragility of WAGFC's high economic value rock lobster export trade.

The third challenge is political tension with China, which impact supply chain connectivity. In October 2020, deterioration in some highly politicised and sensitive bilateral agricultural trade relationships between Australia and China refuelled great uncertainty for Australian seafood exporters (Bonyhady et al., 2020; Dalzell et al., 2020; Srinivasan, 2020). Rock lobster exports to China in November 2020 fell by 80% compared with November 2019 (Mobsby et al., 2021). Although no official ban on seafood actually exists at the time of writing, there have been growing tensions over the delay in the import process for seafood into China. Consignments of rock lobsters were unexpectedly subjected to significant delays at several Chinese ports with the usual rate of inspection for import testing significantly increased. Twenty tonnes of live lobster worth $AUD20 million exported from Victoria, Australia, were destroyed on the tarmac in Shanghai due to unprecedented delays in custom clearances (Bagshaw and Gray, 2020; Bagshaw, 2021). More recently rock lobster exports to Hong Kong have risen sharply from negligible levels in October 2020 to 300 tonnes in March 2021 (Western Rock Lobster, 2021). It is highly likely that this rise is due to what is known as the “grey trade”, where a Hong Kong middleman buys from Australia and then reroutes exports into China (Verrender, 2021; Western Rock Lobster, 2021). Although there have been some positive signs of recovery, “unofficial sanctions” by China on Australian live lobster export trade are continuing to accentuate supply chain disruptions that already existed prior to the COVID-19 shock, impacting livelihoods of those involved in the seafood industry.

Case Study 2: Consumer Behaviour

Consuming food represents one of four broad categories of food system activities. Key actors include consumers themselves, as well as the supply chains bringing food to market, and various organisations that influence food consuming behaviour such as market regulators, advertising, and consumer advocacy groups. COVID-19 has disrupted normal consumer behaviour in many ways (cf Dou et al., 2021). A few examples are described below.

In Australia, panic buying resulted in localised, short-term scarcity in certain foodstuffs and other groceries (Sakzewski, 2020). The first signs of panic buying in Australian supermarkets were reported in early March 2020, weeks before the country went into lockdown. There were temporary shortages of staple foods such as rice and potatoes in many stores, while basic necessities such as toilet paper sold out (Sakzewski, 2020). The government and the food retail sector responded quickly with a set of measures including (Hobday et al., 2020):

• Public reassurance that the food supply was secure and pleading with consumers not to panic.

• Local government easing of transport restrictions to facilitate 24-hour refurbishment of retail supply lines.

• Retailers imposing quotas on some high-demand products, extending opening hours, employing more casual staff and providing exclusive opening hours for vulnerable members of society.

At the height of panic-buying in 2020, the CEO of a large food retailer stated that consumer demand was equivalent to that of around 46 million people whereas Australia's population was under 26 million. Normal supply chains required modification to keep up with demand. Despite experience over the following year or more that food would always be available in the shops, and politicians' and stores' exhortations, panic buying surged at the start of each new lockdown, leading to considerable food waste (Elmas, 2021).

Loss of employment and income has driven vulnerable sectors of the population to rely on emergency food aid in record numbers (Warriner, 2020). Local emergency food aid organisations (e.g. FoodBank, SecondBite) reported a sharp increase in demand for emergency food aid, up from 15% of Australians in 2019, to 31% in 2020 (Foodbank, 2020). While the number of food insecure increased in those categories already insecure before the pandemic, a striking feature in 2020 was that COVID-19 resulted in many people becoming food insecure for the first time. Two groups were particularly impacted, the casual workforce and international students. Ironically, many of those newly food insecure were previously employed in the hospitality and food sector. The emergency food security of those people is met largely through services provided by voluntary organisations. Fredericks and Bradfield (2021) noted new levels of food insecurity among Indigenous students, with school students and their families deprived of food supports provided in some schools, and university students living away from their home communities unable to access family and community assistance for food. As the third wave rose rapidly from mid-2021, there were new reports of surges in demand at food banks.

While information is limited, there are some variants and complexities in food access among remote Indigenous communities. Fredericks and Bradfield (2021) note that movement restrictions have limited Indigenous people's opportunities to shop outside their communities, and purchase limits designed to limit panic buying have impeded Indigenous households who typically travel long distances, infrequently, to buy in bulk. Meanwhile, however, being confined to community areas has enabled more access to bush foods, at least for some; these are a common and valued supplement to bought foods (Fredericks and Bradfield, 2021).

While Australians in general enjoy a high level of food security, even before COVID-19 around 4 to 13% of the general population were estimated to be food insecure. For Indigenous Australians this increases to 22 to 32% of the Indigenous population, depending on location (Bowden, 2020). Fredericks and Bradfield (2020b) report that in Queensland, a state with a large Indigenous population, a third of Indigenous people had faced food insecurity at some time and 20% in the year prior to COVID-19. Follent et al. (2021) note that COVID-19 increased food prices in rural and remote areas of New South Wales, forcing purchase of cheaper and less nutritious foods. Other vulnerable groups include low-income earners, culturally and linguistically diverse groups, single-parents, the elderly, the homeless, and other socially and geographically isolated groups. This list highlights the primary causes of food insecurity in Australia as material hardship and inadequate financial resources, rather than lack of food production or food availability. For Indigenous people, especially those in remote areas, financial hardship can be compounded by additional factors including supply chain logistics leading to limited choices and high costs relative to the cities, and food storage issues which limit buying in bulk (Fredericks and Bradfield, 2021). Interestingly, many Indigenous communities closed their own borders at the start of the pandemic. Food supply issues that needed to be addressed in the first weeks of the pandemic. These were partly solved through self-organising, and through collaborations among a number of major food supply firms (Fredericks and Bradfield, 2021).

Restrictions on social gatherings and self-isolation requirements led to changes in food purchasing (Dawes, 2020), food preparation, and diets in the wider Australian population also (Sullivan, 2020a). These include increased online grocery shopping, home cooking, home gardening, new local food supply chains, increased home delivery of pre-cooked meals, and greater consumption of discretionary (junk) foods and alcohol (Biddle et al., 2020a; Davis and McCarthy, 2020; Dawes, 2020; Gaynor, 2020; Sullivan, 2020a; Zhou, 2020). While the long-term implications of COVID-19 inspired changes in food consumption behaviour remain unknown, what is clear is that these changes have been diverse and profound for many people.

Case Study 3: Food Sector Employment

The food sector is a significant source of employment in the Australian economy with jobs provided in a number of industries including agriculture, food processing, distribution and retail, as well as support industries such as agricultural services, food advertising, education and research. In this case study we focus on changes in employment observed at two ends of food system activities, agricultural and seafood production and the retail food service sector including restaurants and fast food outlets or “Quick Service Retail” (QSR).

As a developed economy with a high standard of living, Australia has high labour costs relative to many other countries. Driving down labour costs is a key management objective for many business owners, and has long-standing political support. This general background is magnified for food export businesses forced to compete on price in international markets. Inevitably, labour productivity innovations forged in export-orientated businesses flow into domestic-oriented businesses. A key labour cost-saving innovation has been casualisation of the workforce with consequent erosion of worker conditions such as pay rates and superannuation, and an increase in part-time and seasonal employment. In seasonal employment, such as planting and harvesting of horticultural crops, industry has become highly dependent on international backpackers and Pacific Island migrant workers, both relying on special category employment visas (Howe et al., 2017). Similarly, at the other end of the food supply chain, involving different types of food system activities, restaurants and QSR have also casualised their workforce to reduce labour costs and remain profitable in a highly competitive business environment. In Australian cities, international students supplement their income with casual employment, often in food sector businesses. While their student visas allow part-time employment, they remain vulnerable to sudden changes in economic conditions (Bogle, 2020), as highlighted by COVID-19.

One of the first government reactions to the global pandemic was to restrict movement of people across domestic and international borders. This policy immediately impacted the horticulture sector, jeopardising the supply of workers for time-critical work such as harvesting perishable crops. Not only were new workers restricted from arriving in Australia, international workers already in Australia were restricted from returning home. Horticultural producers warned of and later suffered crops being left unharvested (Bolton, 2020), and pleaded for policy exemptions to maintain labour in what was decreed an essential service. Public health standards for managing COVID-19 meant existing worker accommodation and conditions were in many cases no longer adequate. Furthermore, non-resident workers unable to reach employment locations were ineligible for government unemployment programs and other welfare programs, creating a high level of insecurity. Similarly, restaurant and QSR casual workers were made redundant as governments mandated social distancing and business closures. Overnight, many international students lost their casual work income and their non-residency status meant they were ineligible for government unemployment benefits and welfare programs. Emergency food organisations reported a sharp surge in demand for food aid from international students previously not experienced (Sallim, 2020).

The impacts described above continue to evolve, as farmers experience on-farm labour shortages (Sullivan, 2020d). As state (internal) borders continue to restrict transport of goods and services as well as people, farm businesses located along state borders continue to be severely disrupted, affecting crop management and livestock husbandry. In the early stages of the pandemic, abattoirs emerged as coronavirus hotspots, highlighting poor working conditions including a workforce employed in shifts on a casual basis. Many businesses have survived on emergency government support programs (wage subsidies, debt moratoriums, rent holidays, etc.) though many express fear now that those subsidies have ceased, and the country continues to experience outbreaks. On a more optimistic note, new businesses and employment have emerged out of the pandemic, including direct marketing of farm produce to consumers and home delivery of ready-to-eat meals from restaurant to consumer.

While restrictions on the movement of people have proved effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19, it continues to come at a cost to food sector employment. From a food systems perspective, the dominant impact to date has not been a direct deterioration in food security, but rather an impact on employment, livelihoods and businesses. In turn, loss of pre-COVID-19 livelihoods will impact on food security by reducing purchasing capacity. As discussed in case study 2, those workers in casual employment have been impacted more severely than workers with more secure employment. Especially vulnerable are non-resident, casual workers who not only lose employment but also are ineligible for government welfare. Under current Australian policy, these include international students.

Casualisation of the workforce has contributed to cheap food for consumers. But are consumers aware of their role in exploiting workers, and what price might they be willing to pay for a fairer distribution of their food purchasing dollar? Food businesses orientated to export markets are constrained by the need to be competitive on international markets. In contrast, domestic food producers and processors are driven by a powerful food retail duopoly to drive costs out of the supply chain. Casualisation of the food sector workforce has been the historical strategy of choice by employers to reduce costs in Australia, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed vulnerabilities associated with this strategy. If a majority of Australians desire fairer food systems, one where workers receive adequate working conditions and remuneration, the trade-off might be slightly higher food prices. Potential benefits include not only improved working conditions, but a more resilient food system.

Discussion

Impacts of COVID-19 and Adaptations in Australia's Food Systems

We analysed three case studies through the combined lenses of food systems and resilience to understand the breadth and complexity of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australian food systems, and system responses. Measures to protect society from the pandemic disturbed parts of these systems and stimulated diverse adaptations, leading to “ripple effects” (Béné, 2020) as actors throughout the system and subsystems changed practices (cf Devereux et al., 2020; Love et al., 2021; Snow et al., 2021) in order to pursue their own resilience – rather than necessarily system resilience - in changed circumstances. Our case studies reveal points of vulnerability within Australia's food systems, as well as examples of adaptation which enable these systems to self-organise in response to the viral shock (cf Devereux et al., 2020).

Vulnerability of Supply Chains to International Export Markets

The seafood export case study reveals the vulnerability of an industry heavily reliant on a single dominant export market (cf Love et al., 2021), a structure which in complex adaptive systems terms stands out as lacking diversity. When COVID-19 struck, producers were largely dependent upon a specialist, lucrative, international food market and hence were vulnerable to changes in the global food system and markets. While producers benefitted from increased profit margins through participating in export markets, the trade-off is that they have a relatively low level of adaptive capacity with respect to changes (political, economic or otherwise) within these global trade systems as they have minimal ability to influence markets, laws and consumer behaviour in an international context. The resilience of the Australian food system is thus strongly linked to interactions with food system drivers, activities and outcomes occurring in other countries and regions of the world. i.e. Australia's food system is part of a multi-level system extending beyond its shores. However, while disruptions to international supply chains threatened the livelihoods of Australian producers and actors throughout their supply chains, the adaptation of turning to domestic markets offered some resilience, after a lag time, and increased food availability in the domestic market.

Employment Conditions Throughout the Food System Reduce the Resilience of the System Overall

COVID-19 highlights the importance of secure labour at every stage throughout food supply chains, from production through to retail activities. Our case study demonstrates that poor working conditions and over-reliance on a casualised workforce decrease the resilience of the system overall.

A lack of resilience was observed in terms of employment arrangements within the food sector that have inhibited the system in providing food availability, and food access to those left without incomes. National and state border closures left agricultural producers, normally reliant on low-paid, seasonal and temporary migrant and backpacker labour, without sufficient labour, thereby potentially decreasing the volume of food produced and supplied. Farmers reportedly had little influence over the policies implemented to deal with the pandemic, for example they were unable to secure the exemptions they sought in the early stages of the pandemic to allow migrant workers to fly in during the pandemic. Arguably, poor working conditions on farms (including low wages, and the nature and price of accommodation) fail to attract domestic workers. This is partly related to consumer expectations of having access to inexpensive produce, and large retailers' pressures on farmers to supply foods at low price. A lack of farm workers poses a risk to food availability within the Australian food system. This may ultimately drive greater investment in the use of robotics in the agricultural system to address the shortage in labour. More optimistically, future employment conditions and remuneration may need to be fairer and more attractive for on-farm workers.

The casualised nature of employment throughout the food sector has also reduced the food purchasing power of workers employed in businesses that closed (cafes and restaurants), especially those ineligible for government support owing to gaps in that system, then the cessation of the first and second wave supports. This highlights the economic vulnerability of these workers within Australia's food systems. A significant failure has been the creation of a large cohort of newly food-insecure international students and temporary visa holders. Fortunately, voluntary and not-for-profit organisations have largely met emergency demand for food aid, showing system resilience in their gearing up rapidly to serve this system failure.

The system thus exhibited a low level of resilience in terms of maintaining social welfare outcomes for certain types of employees, namely the casualised and temporary workforce. These workers, many of whom are youth and non-residents of Australia, had minimal capacity to influence their situations or pursue alternate work within a system under high pressure. The system showed some adaptive capacity thanks to the existence of food charities, which managed to expand rapidly, while new ones emerged. This case study highlights the important role of having alternate capacities, here food charities, in enhancing the resilience of the food system to ensure food security for all. The pandemic highlighted systemic inequities in food sector employment as a key driver of food system activities, i.e., how food is produced and distributed, and thus food system outcomes, i.e., accessibility of food.

Consumers Lack Confidence in Supply Chains

Ultimately consumers drive demand through food supply chains. COVID-19 has revealed features of our food supply chains normally hidden from view and has invited many to pause and reflect on our relationship with food and our consumption of it. There is a new awareness of the dominance of casual employment and reliance on international workers to carry out essential roles in our food supply chains and how these workers are highly vulnerable to shocks within the system. There is greater awareness of concentration of market power in food retailing and of worker conditions on farms and in food processing enterprises.

Sudden changes in consumer behaviour challenge supply chains, forcing very rapid action to maintain food availability. COVID-19 exposed a weakness in the food system in terms of the dominance of two large retail supermarket chains, highlighting low diversity in options for consumers to access food and other necessities. The large extent of panic buying at particular crisis points (each impending lockdown) suggests a sense of uncertainty among consumers about supplies of what they perceived as essentials (cf Whelan et al., 2021, in a local Australian case study).

While staple food items were scarce on shelves for a short time, the retail sector was able to adapt quickly to meet demand, through using their market power and multiple connections to step up production and supplies, and diversify supply lines where necessary. Meanwhile large retailers and various levels of government worked to build confidence through messaging, relaxation of urban transport restrictions, and working closely with supply chains to restore and expand supplies. In so doing these actors exhibited a high degree of adaptive capacity and cooperation in relation to the distribution and retailing of food. Meanwhile consumers discovered the diversity of outlets actually available to them, including small and specific ethnic suppliers, and provided greater support for localised food system actors. The system thus demonstrated resilience as consumers purchased products from alternative retailers, which strengthened diversity within the system. The system also demonstrated the power large retailers have in influencing the system, as exhibited by the consequences of a low-price business model (see above), and then by their adaptive capacity to bring about change in their operations quickly. This includes some benefits, such as the collective organising of large retailers, with Indigenous communities and others, to solve food supplies to communities that had closed their borders for health reasons.

For now, there is greater support for local food systems (buying local), and perhaps a greater willingness to support growers and fishers to realise a fair return on their efforts. Whether any of these result in lasting change in food consumer behaviour remains unknown.

Adaptive Behaviour and Resilience

All of the case studies show intensive and rapid efforts towards adaptation on the part of private sector actors, all levels of government, and consumers. It is too soon to attempt summary as to the extent to which parts of the system have, or have not, been resilient, as “driver” settings continue to change, and actor responses continue. It appears that many – or most - actors have been proactive, and often inventive, in solving pressure points in the rapidly changing system. In terms of the food systems framework we are using, food system activities occurring along supply chains - i.e., producing, processing and packaging, distributing, retailing and consuming - are not so much separate activities, as integrated activities that underpin livelihoods and provide food security. Diverse supply chains, and the ability of particular supply chains to diversify themselves rapidly, have been highly important in Australia's apparent resilience to the crisis. Some interesting constraints to adaptation were nevertheless shown. For instance, suppliers to restaurants could not make rapid switches to supply retail stores, because of different packaging requirements and machinery limitations.

Overall, the pandemic has affirmed diversity as a vital component in resilient systems. While Australia's distribution system is dominated by key supermarket chains, each should be recognised as providing diverse foods (and other goods) to consumers, and as using diverse supply chains for each food marketed. Meanwhile, a large number and variety of small, local outlets provided alternative sources of foods, and contributed to a trend towards greater support for local businesses. The existence of food charities enabled this latent resource to expand to serve those left unable to purchase food as they were excluded from the federal government's financial support policies.

Meanwhile connectedness, another characteristic noted of resilient systems (Sundstrom and Allen, 2019), complements diversity in supporting resilience, by enabling the diverse components available to be activated in new ways. However, as Sundstrom and Allen (2019) note, high connectedness can also make a system vulnerable to disturbances.

Australia's food system is a multi-level system, linked by many short and longer food supply chains. Local, regional and national adaptations have influenced one another. Cooperation between private sector and government, among firms that would ordinarily be considered competitors, and along supply chains, has been evident and effective in supporting adaptation and resilience. This included easing (or tightening) border restrictions for people, goods and services; categorisation of the food sector as an essential service; easing restrictions for Pacific Island worker schemes; reducing transport restrictions to improve capacity for restocking supermarket shelves; and subsidising freight for food export businesses. This suggests high connectivity within the system as evidenced by relationships that facilitate communication and cooperation towards solving problems and so stimulating system changes. It also represents high agility (Ivanov, 2020) on the part of many supply chain actors.

Integrating Resilience Thinking Into Food Systems Theory and Practice

By observing how the shock of COVID-19 and associated policy measures have forced rapid changes in Australia's food systems, we can gain important insights for improving resilience of those systems. First, we need to understand a food system as a complex adaptive system. This is more than a matter of showing feedback loops in framework diagrams, as the GECAFS food systems framework does. We need to recognise that the constant interaction of many parts of the system, at many levels, produces emergent properties, i.e. new – often temporary - characteristics in the system that transcend specific observable causes.

The particularities of COVID-19 also create some opportunities to refine existing food system conceptual frameworks. The original food system framework (GECAFS) notion of “drivers”, for instance, had not envisaged health crises, but the recent literature on food security (e.g. HLPE, 2020) highlights “political and institutional drivers” as a driver of other drivers and particularly in the context of food system resilience. As the HLPE framework acknowledges briefly, far greater attention needs to be paid to resilience, the characteristics of these multi-level systems that facilitate adaptability in the event of shocks, rather than focusing entirely on the sustainability of the system. Tendall et al. (2015) point out how sustainability, capacity to preserve a system long-term, and resilience, capacity to cope with disturbances, are complementary and both essential.

The frameworks may also require rethinking in terms of goals. The GECAFS framework we have used focuses on food security (in several dimensions) as primary goal, while also acknowledging social and environmental outcomes. Alternate, and multiple, goals can be considered to co-exist with the goals of supplying food, and these may drive behaviour in parts of the system. In government policy, international relations can play a role; the many businesses participating in food systems surely incorporate multiple goals such as viability, market share, and perhaps corporate social responsibility including environmental and social dimensions. Goals may shift in a crisis, hence what we have observed in terms of high levels of cooperation to maintain food supplies, transcending everyday competition. This recalls Helfgott's (2018) unpacking of resilience in terms of: of what, to what, for whom (and over what timeframes). In the parts of the national food system, one can envisage actors exercising high agency over their “for whom”, to promote resilience in their particular parts of the system but inevitably with effects on other system parts, and system actors.

In our analysis, some key features have stood out as facilitating resilience. Australia's food system adaptations represent a high degree of self-organising, or more accurately re-organising to meet new circumstances. This has occurred at all stages of supply chains, including where consumers have become producers through increased home-gardening. We have noted features in the structure and organisation of Australia's food system and its many parts, which have, with some exceptions, supported that re-organising. Diversity, even within a highly concentrated retail system, appears to have been very important. It has apparently combined with connectedness, enabling new solutions to be found through activating and developing new relationships, in a spirit of increased cooperation during the sense of emergency. We have also observed a high degree of agency, pro-activeness and indeed agility among food system actors, private sector, government, not-for-profits and consumers. These are important features to retain. Next must come learning, to continue to build the system's performance and resilience (Fazey et al., 2020; HLPE, 2020).

Conclusion

COVID-19 and related responses represent a significant and complex shock to Australia's food systems. By and large, but with a few significant exceptions, these systems have proven adaptive and resilient, although individual businesses are likely to continue to collapse as the pandemic persists. Our case studies have highlighted the importance of “agency”, expressed at different levels throughout the food system (from the individual to government institutions), in how food systems function.

Exploring and unpacking dimensions of agency and associated governance structures within a given food system can reveal different goals and priorities among actors who have varying levels of power and influence. In order to build resilient people-centred food systems that are equitable and inclusive, it is necessary to ensure that the goals and priorities of those that are most vulnerable are recognised and accounted for in decision making processes. For example, if we accept that the key outcome desired of food systems is food security, then the majority of Australians have continued to be able to afford and access food, without fundamental changes to diets. However, food security is not the only outcome of food systems. Social welfare in terms of secure livelihoods and employment, for example, is also important to ensure there is a labour force actively driving the system and that those people are being fairly compensated for their work, to ensure they can meet their own nutritional needs. It is these goals and priorities that also need to be reflected within a resilient food system.

Globally, there are calls for realising the pandemic as an opportunity for change to a healthier, more sustainable and socially just food system. Australia is likely to remain a food exporting country into the future, and hence make a significant contribution to other countries' food security. In doing so, we need to ensure that all Australians whose livelihoods depend on, or are employed in our food industries, from production through to retail, receive satisfactory working conditions and fair remuneration for their labour.

Building greater resilience into our food systems will thus require a long-term view to address the structural dimensions (Béné, 2020), for example government policy and legislation, which determine how the various dimensions of our food systems function, interact and become reinforced overtime. COVID-19 has presented a shock to the social patterns underpinning Australia's food systems to provide an opportunity to overcome vulnerabilities within the system to enhance food security for all.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived of the study, jointly, and discussed the development and interpretation, reviewed and commented on the manuscript throughout the information gathering and writing process, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version. NJ, HR, and WB took editorial responsibility. WB, HR, SB, JB, and NJ each wrote substantial sections and which were edited by all other members.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Gomathy Palaniappan for participating in discussions and her contribution towards case study number two.

References

Amjath-Babu, T. S., Krupnik, T. J., Thilsted, S. H., and McDonald, A. J. (2020). Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Secur. 12, 761–768. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01083-2

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (2020). Australian Food Security and the Covid-19 Pandemic, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences. Canberra, ACT.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021). Population Clock. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1647509ef7e25faaca2568a900154b63?OpenDocument (accessed 06 July 2021).

Australian Government Department of Health (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) at a glance. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-31-october-2021 (accessed 31 October 2020).

Bagshaw, E.. (2020). Emergency 'lobster flights' to save $800 million worth of seafood. Sydney Morning Herald. Available online at: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/emergency-lobster-flights-to-save-800-million-worth-of-seafood-20200331-p54fqa.html (accessed March 31, 2020).