- 1Department of Humanities, Faculty of Economics and Management, Czech University of Life Science, Prague, Czechia

- 2CURSA—University Consortium for Socioeconomic Research and Environment, Rome, Italy

- 3Associazione Botteghe del Mondo, Rome, Italy

- 4Department of Bioscience and Territory, University of Molise, Campobasso, Italy

- 5CREA Policies and Bioeconomics, Rome, Italy

- 6Department of Architecture and Project, University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy

In the food policy arena, the topic of governance and how to create a governance system that would deal with cross-cutting issues, including new ways of perceiving the public sphere, the policymaking, and the involvement of the population, has become an important field of study. The research presented in this article focuses on the case study of Rome, comparing different paths that various groups of actors have taken toward the definition of urban food policy processes: the Agrifood Plan, Food Policy for Rome, and Community Gardens Movement. The aim of the research is to understand the state of the art about different paths toward food strategies and policies that are currently active in the Roman territory while investigating the relationship between policy integration and governance innovation structures. Indeed, this paper dives into the governance structure of the three food policy processes, the actors and sectors involved, and the goals and instruments selected to achieve a more sustainable food system for the city. In this context, their characteristics are analyzed according to an innovative conceptual framework, which, by crossing two recognized theoretical systems, on policy integration and governance innovation frameworks, allows to identify the capacity of policy integration and governance innovation. The analysis shows that every process performs a different form of governance, implemented according to the actor and backgrounds that compose the process itself. The study demonstrates that governance innovation and policy integration are strongly linked and that the conception and application of policy integration changes according to the governance vision that a process has.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought to light important challenges concerning food systems, but it has also made visible the multiple ways in which the food system sustains urban life. The importance of the urban food policies across the world has recently been recognized in international arenas such as the United Nations New Urban Agenda or the Sustainable Development Goals (UN Habitat, 2015). In addition, the increasing emergence of institutional or grassroots processes aiming at fixing the issues of food systems demonstrate that cities are affirming the power of food not only to sustain the lives of an increasingly urban population but also to deliver economic prosperity, address social and health inequalities, and foster environmental sustainability (Moragues-Faus et al., 2013). Urban Food Policies (UFP) have been defined as “a process consisting of how a city envisions change in its food system, and how it strives toward this change” (ibidem). Therefore, inherent in the concept of Urban Food Strategy is the transition of the food system model toward one that is more sustainable, equitable, and socially, environmentally, and economically balanced. This transition involves a large number of institutional and private actors, representatives of civil society, movements, and organizations of various kinds.

The ability to govern this diversity and direct it toward shared and innovative trajectories has, in many cases, been entrusted to the Food Policy Councils (FPC). These are arenas for consultation and/or deliberation in which democratic confrontation between the actors of the transition takes place or should take place. In addition, the FPC, being the result of the diversity of approaches adopted in the UFP, vary in organizational form, methodology of interaction between the participants, and ability to represent the multitude of stakeholders involved. As stated by Moragues-Faus and Morgan (2015, p. 1159), the “spaces for deliberation” and the design of models of inclusive stakeholder engagement are elements common to several existing experiences, despite the fact that there is not a single pattern (Gianbartolomei et al., 2021). The initiatives implemented in the cities vary in terms of the resources activated, the actors involved, the issues addressed, the level of democratization of the processes, and, essentially, in the governance models. The aspect that emerges, however, is a certain solidity of the panorama around the theme of food policies, an area in which cities—in the various governance configurations—are increasingly assuming the role of policy innovators. In this context, an important role for rescaling food governance vertically across scales is played by regional, national, and international networks. The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, a protocol developed in 2015 committing to develop sustainable food systems and now signed by more than 200 mayors across the globe, is a clear example of these expanding city-to-city alliances. Other initiatives designed for circulating knowledge and experiences and accelerating the transformation of urban foodscapes are thematic working groups within existing networks such as C40 or Euro-cities and new platforms focused on food-related challenges such as the UK Sustainable Food Cities network (recently rebranded as Sustainable Food Places) (Moragues-Faus and Battersby, 2021a) or the Italian Network on Local Food Policies (Dansero et al., 2019).

The variety of approaches to urban food policies has recently been investigated by various researches, which attempt to map the most effective policy models for the urban food policy establishment (Doernberg et al., 2019; López Cifuentes et al., 2021; Moragues-Faus and Battersby, 2021b; Vara-Sánchez et al., 2021). To address the interconnected challenges of food systems effectively, scientists and policymakers have stressed the need for integrated food policy (Lang et al., 2009; MacRae, 2011; IPES-Food, 2017; Moragues-Faus et al., 2017; Candel and Daugbjerg, 2019). However, one of the aspects that still remains partially unexplored in the research on Urban Food Policy is the ability to integrate the different sectors that, directly or indirectly, have an impact on food systems or could benefit from food policies. In other terms, the capacity to horizontally integrate, include, and coordinate actors from farm to fork and all sectors from health to economics and the environment has still not been explored sufficiently. This aspect is particularly relevant for the future of food governance in cities, as the goal of the UFP is the development of a “roadmap” helping the city to integrate a full spectrum of issues related to urban food systems within a single policy framework that includes all the phases from food production to waste management (Mansfield and Mendes, 2013).

Another aspect that often emerges from the debate on UFP is the innovative scope of the initiatives. These initiatives generally comprise “networks of activists and organizations, generating novel bottom–up solutions for sustainable development; solutions that respond to the local situation and the interests and values of the communities involved” (Seyfang and Smith, 2007, p. 585). As Moragues-Faus and Morgan (2015, p. 1561) highlight, such networks are often created by “food champions” or “policy entrepreneurs,” key enabling agents of a new form of food planning and policymaking. The outcomes of these initiatives are different, and they move in a continuum that goes from the antagonism of alternative movements toward the institutional and political order to the institutionalization in Urban Food Policy managed by local administrations. While some authors have found that institutional innovations can play a key role in considerably institutionalizing food governance ideas within a relatively short time span, other research (Sibbing and Candel, 2021) finds that the institutionalization of food action into a policy is not a smooth process. Indeed, the formation of a food movement and the development of a more institutionalized food policy encompass different stages (movement formation, coalition building, strategy formalization, and implementation pathways), all bringing about tensions and challenges (Manganelli, 2020).

At the Italian level, several studies on local food policies have been published in the past years (Marino et al., 2020), analyzing the experience of some cities in promoting new models of governance such as the Food Policy Councils (Calori, 2015), in assessing the potential of shorter food supply chains and alternative food networks (Marino, 2016), and in managing food waste (Fattibene, 2018; Fassio and Minotti, 2019). However, a research combining horizontal policy integration and governance innovation for UFP analysis in a single framework has not yet been proposed. For these reasons, the objective of the paper was to analyze the multifaceted panorama of the different paths that have been activated in Rome in recent years and months around a city food policy. The choice to analyze the case of Rome was motivated by the fact that many food-related initiatives across the city have emerged over the last decade that seek to re-engage citizens and reignite the debate on sustainable, healthy, and local food. Such initiatives include multifunctional urban and peri-urban agriculture projects, solidarity buying groups, and farmers' markets (Mazzocchi and Marino, 2020). The research was carried out through the construction of an analytical framework useful for investigating the integration of policies and governance innovation. The interviews were administered to the representatives of the three main routes currently active in the city of Rome, which correspond to three different pressure groups and three different territorial scales. The paper therefore has a double objective: from a theoretical point of view, it offers an original and replicable analytical framework for analyzing the innovation and governance of other food policies; from the point of view of the research results, it offers significant insights to understand the multitude of itineraries taking place in the city of Rome.

Context of Study

To fully understand the development of urban food—and agriculture—policies, it is necessary to start from the fact that, in Italy, it is not possible to separate the issues of the city from those of the countryside1. In particular, for the purposes of this study, it is important to highlight the relationships that are established in this dynamic between the various actors—agricultural producers, breeders, citizens–consumers, builders, landowners, and civil society—and how these affect the formation of urban policies, including those regarding food. Wanting to choose a point from which to start, one cannot fail to consider as central the work of Emilio Sereni and his History of the Italian Agricultural Landscape (1961). In Sereni's work, the Landscape is in fact a method for reading the dynamics of the economic relations between the city—and in particular its political and financial capacity—and the countryside as a space for production, income, and power. The landscape therefore allows us to read the dynamics—conflictual and/or cooperation—between the different economic and political actors in a reciprocal and continuous exchange between city and countryside2.

The city of Rome is an excellent case study of how the relationships between city and countryside can be interpreted in terms of urban policies and how those relationships are a fundamental element of urban food policies. The metropolitan area of Rome has a population of about 4.34 million inhabitants for an extension of 5,352 km2. At the municipal level, the total agricultural area of Rome is ~58,000 ha, or 45.1% of the territory, an extension that makes Rome the second largest agricultural municipality in Europe. In the Roman countryside, a large number of quality agri-food products are produced and processed: in the province of Rome, there are 15 PDO—Protected Denomination of Origin—(8) and PGI—Protected Geographical Indication—(7) products, among which stand out products from livestock chains such as Abbacchio Romano, Pecorino Romano, and Ricotta Romana. In fact, historically, sheep and goat farms have represented a fundamental economy for the Agro Romano, substantially determining the landscape, uses, and traditions of the Roman countryside.

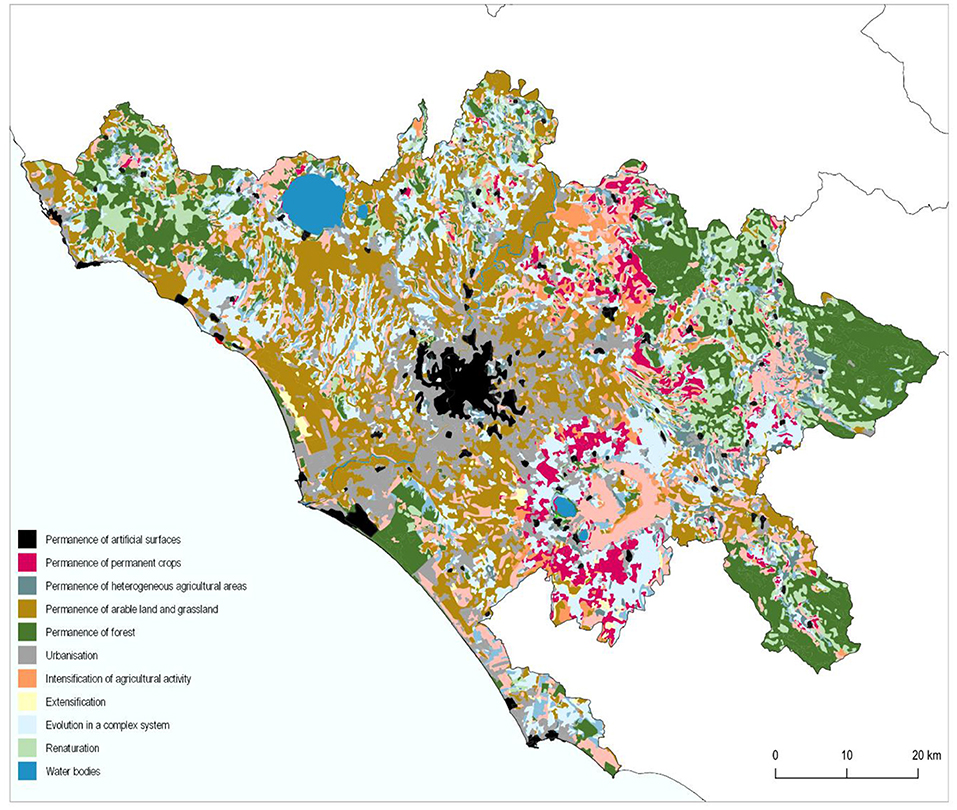

Despite this potential, the agricultural land, especially after the Second World War, was seen—albeit with some deserving exceptions—as a surface destined for building expansion, even for speculative purposes. According to the latest Report on Land Consumption in Rome, about 24% of the territory of Roma Capitale is consumed soil, of which most of it is waterproofed (91%, 28,256 ha), with significant implications for ecosystem services (Roma Capitale, ISPRA, 2021), and in recent years, the increase has been equal to 12% against a population increase of 1.1%. The constant fading of the historical centrality of agricultural activities in the complex Roman agri-environmental mosaic has produced a series of negative impacts in economic (agricultural production) and environmental terms (loss of ecosystem services) (Cavallo et al., 2015). This trend has produced a series of negative impacts in economic (agricultural production) and environmental terms (loss of ecosystem services). Above all, social negative impacts caused a cultural divide between citizens and their countryside, seen only as an area of backwardness and a reservoir of building surfaces. The expansion of the settlement areas took place—despite the presence of planning tools—without an organic vision that caused a great increase in the historically compact city. Furthermore, large farms of over 100 hectares, despite being only 2% of the total number of Roman farms, occupy over 40% of the UAA” (Cavallo et al., 2016). At the same time, large areas, considered no longer profitable, are abandoned (in particular arable land, pastures, but also the vine). Figure 1 shows the land use transitions from 1960 to 2018.

Figure 1. Land use transitions in the metropolitan city of Rome (source: authors elaboration from CNR-TCI 1960 and Corine Land Cover 2018).

However, this urban model has produced the permanence of many residual agricultural areas within the urban fabric. This phenomenon originates both in the context previously mentioned and in the “resistance” of small farmers who, starting from the historical occupations of the land in the 1970s, have developed multi-functional and innovative paths both in the deepening and broadening sense (organic farming, direct sales channels, social agriculture, etc.). The Roman countryside is therefore populated with very different economic actors: multifunctional companies with strong relationships with citizens; large companies in which the logic of annuity often prevails; specialized companies organized in traditional supply chains such as that of fresh milk; shepherds; builders, etc. To these are added other types of urban actors that have an eye to the countryside and food: movements of young farmers who demand the management of public lands; GAS; initiatives of solidarity economy; urban gardener who cultivate the land often occupying and self-managing urban greenspaces of different sizes inside the built city; nets for the recovery and redistribution of food surplus, etc. (Mazzocchi and Marino, 2020). In addition to urban and peri-urban agriculture, the urban garden movement has had an extraordinary diffusion, with a positive impact above all on a social and environmental level: Zappata Romana, for instance, has been mapping the experiences of community gardens and gardens in Rome, which today are about 218 between shared gardens green spaces.

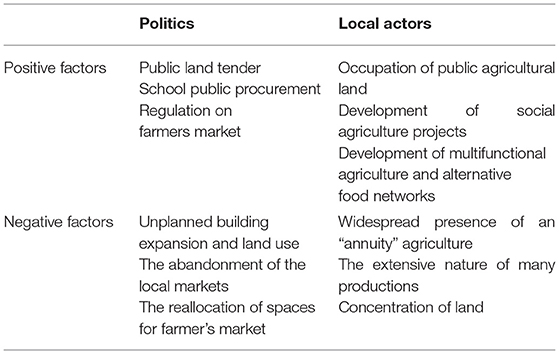

Each type of actor has developed its own dialogue with policymakers, through direct or indirect pressure, determining—with varied paths—a response from the institutions. The pressure factors and the responses, as can be seen from Table 1, were—according to a social and environmental assessment—of not only a positive but also a negative nature.

Table 1. Negative and positive factors of the direct and indirect pressure of Roman local actors on politics during the years (source: authors).

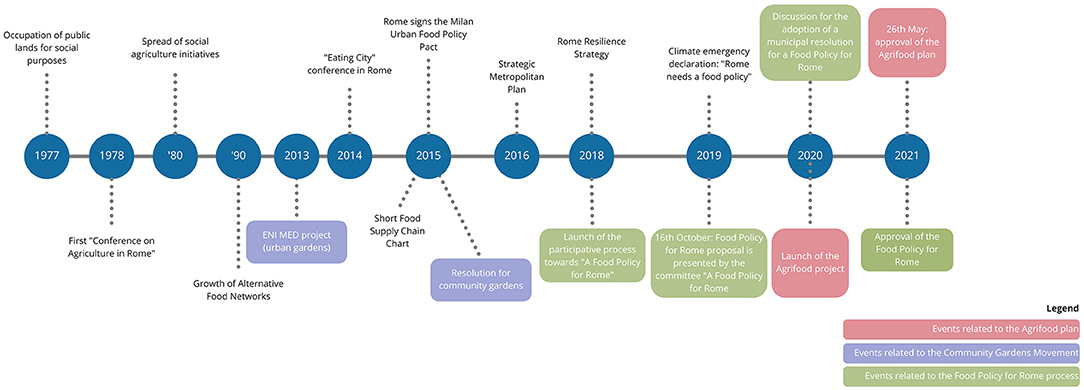

The dialogue between politics and territorial actors has resulted in a series of more structural and organic policies, which, in recent times, have been intensifying, as a sign of greater attention from the institutions. Figure 2 traces the main stages of these policies, showing three important processes, which have been selected as the focus of this research's analysis: Community Garden Movement, Food Policy for Rome (FPR), and Agrifood Plan, which will be described in the following sections. As Figure 2 shows, they have all been developing in the city of Rome in the past years and represent three different processes all involving the topic of food and food policies.

The study analyzed these three processes from a governance and policy integration point of view, as the following sections will thoroughly explain.

Methodology

This study bases its theoretical and analytical framework on two main concepts: policy integration and governance innovation. In regard to cross-cutting and systemic issues, such as food policy, this article starts by the assumption that “sectoral policy in itself is insufficient for addressing crosscutting problems and that these problems instead need to be taken on board by other relevant sectors to address externalities and, possibly, create synergies” (Lafferty and Hovden, 2003 in Sibbing et al., 2021).

For this reason, policy integration is a necessary tool to deal with food-related issues, as they require an integrated approach, especially when talking about governance (Lang et al., 2009; MacRae, 2011; Candel and Biesbroek, 2016). In particular, when looking at policy integration, many are the lens of study and analysis. This study used the Candel and Biesbroek (2016) approach for which integration's goal “is to incorporate, and, arguably, to prioritize, concerns about issue x (e.g., environment) in non-x policy domains (such as economics, health or spatial planning), with the purpose of enhancing policy outcomes in domain x” (Candel and Biesbroek, 2016 in Sibbing et al., 2021). This approach intends integration as a process and not only as a policy outcome, which revolves around four dimensions: frame, subsystems and their involvement, goals, and instruments (Candel and Biesbroek, 2016):

1) Frame is how a problem is intended and understood within a system. Here, the focus is if the cross-sectoral nature of the problem is recognized as such by the given system.

2) Subsystems are the range of actors and institutions involved in the governance of a particular cross-cutting policy problem. In particular, the framework focuses on which subsystems are involved and takes the political initiative to address the problem and what is the density of interactions between subsystems.

3) The goals of the policy can be explicit, meaning the adoption of a specific objective within the strategies and policies of a governance system, or implicit. How the goals of the various domains and their respective subsystems relate to each other is one important area of analysis.

4) Instruments are the tools with which to achieve a goal. They can be substantial, namely, the allocation of government resources that directly affects the supply of goods and services, or they can be procedural; in this case, they modify the political process to ensure coordination.

For all these dimensions, the Candel and Biesbroek framework provides definitions of low and high degrees of policy integration with intermediate levels that in this article will be called medium low and medium high.

When talking about policy integration, one interesting perspective is to look at governance innovation as well. This would mean to highlight if policy integration processes included innovation or not. Innovation is a complex and complicated issue, especially if applied to public policies and their governance system. Hartley analyzes this concept in her study (2005) defining governance innovation as a wide variety of novelties in action, such as new political arrangements in local government, changes in the organizational form and arrangements for planning and delivery of services, and public participation in planning and to the provision of services (Hartley, 2005). Hartley's work focuses on the idea that three main governance innovation paradigms exist, which differ for the way innovation and improvement are intended, and for the role that policymakers, public managers, and the population have. Here, governance innovation is not only a change in ideas but also a change in practices that increases the quality, efficiency, or suitability of public services (Hartley, 2005).

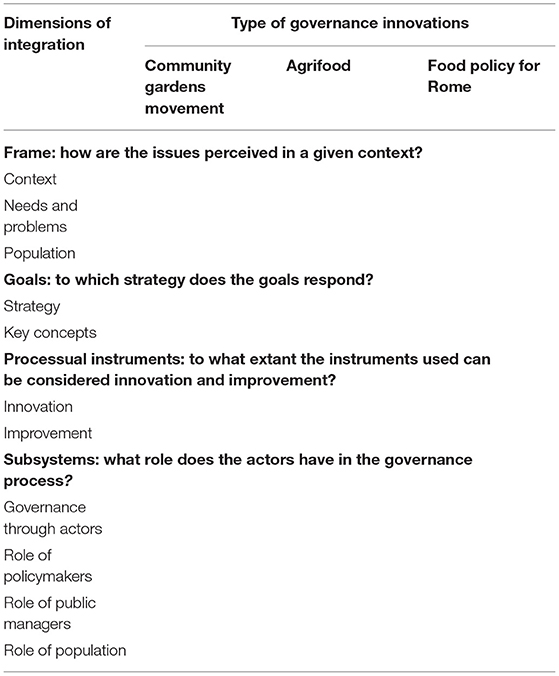

Starting from these two theoretical frameworks, this study designed an analytical framework that cross the two concepts briefly described. Table 2 shows the framework used to analyze the case studies of this research.

This framework is rooted in the assumption that policy integration, in the food policy arena, is strongly interconnected to a governance innovation. Hence, policy integration here is analyzed through the lens of governance innovation in order to better understand the context and frame in which it is designed and implemented and the goals that drive the process along with the instruments that guarantee the innovation or improvement toward a specific goal. Finally, the framework also investigates the role of the actors involved and the way the governance of the process is related to those actors.

For each case study selected, the framework helped in the design of the interviews, meaning the selection of interviewees and questions, and in the analysis of the results. The Discussion and Conclusion section, then, the two original frameworks—Hartley, 2005; Candel and Biesbroek, 2016—have been used to resonate upon the results.

The three case studies have been selected according to previous knowledge of the topic and for their important contribution to the urban food policy topic in the city of Rome. In particular, the authors selected three case studies that are currently ongoing on the Roman territory, which all have different natures, goals, and perspectives.

For each case study, three key informants have been selected for in-depth interviews on the topic of policy integration and governance innovation, for a total of nine interviews. For each process analyzed, different types of interviewees were selected, all with the same characteristics of being fundamental actors in one of the case studies. In particular, regarding Agrifood, the interviewees were selected among the institutional actors (two interviewees) and technicians (one interviewee) that worked in the process design and implementation, while for the Community Gardens Movement, the authors selected one perspective from the institution and two from the social movements. Finally, for the Food Policy for Rome project, three of the civil society founders of the movement were interviewed.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the interviews have been conducted online during the month of June 2021. All interviewees responded to the same set of questions, customized to the specific case study or project they were called to represent. The theoretical framework previously described (Table 3) helped to design questions besides structuring the analysis.

Results

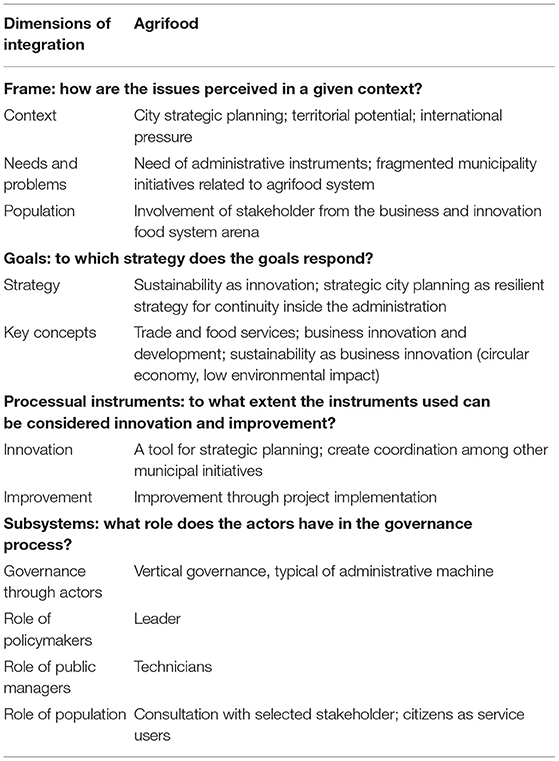

Agrifood Plan

In 2020, the Rome Municipality Agriculture, Production Activities, Trade and Urban Planning department, in collaboration with the Chamber of Trade, started the promotion of the Agri Food Plan (Agrifood or the Plan) as an industrial plan of the city's agri-food sector aimed at affirming a competitive identity to attract investments in urban and rural areas. The main objectives of the plan are the creation of a food policy for the city based on the enhancement of Rome and its province's agri-food chain and on the promotion of typical local products. The plan creation and drafting involved researchers, trade associations, Roman food system stakeholders, companies, and entrepreneurs, in a participatory process carried out through working tables and town meetings. The Agrifood Strategic Plan for the City of Rome was approved by the City Council May 26, 2021, as part of the 2030 economic and urban development strategy. Along with this food- and agricultural-related Plan, two other strategies accompany the 2030 vision for the city: one regarding tourism, the other on smart business. The main objectives of Agrifood refers to giving value to Roman agrifood supply chain, promoting Roman typical products, and identifying a food policy for the city (Agrifood Strategic Guidelines, 2021). The whole idea behind this strategic vision has been built for the need to empower the potential that the city of Rome has on food-related topics and give to the Italian capital an international role in the urban awake that has been characterizing cities all over the world (Interview 1 and 2).

The Plan has been designed by the Economic Development, Tourism, and Work Department in collaboration with the City Planning Department, and followed a three-step process:

1) Closed participative table meetings with selected experts, universities, and institutions

2) Town meeting with a wider range of stakeholders

3) Design and writing of the Plan by the two departments involved and a food supply chain expert.

This process has been followed by an ad hoc office on urban economic innovation, politically led by the two departments and administratively managed by a department director expert on innovation and social networks (Interview 1). Besides this office, the Plan has created an advisory board and a business board to help design the strategy (Interview 3).

As Table 4 shows, four are the main topics around which Agrifood rotates. First, the market is a pivotal space in which consumption patterns as much as commercial challenges can be understood and changed. Second is the definition and promotion of what the Plan calls “la distintività,” meaning the signature, the characteristic of Roman food from a production and consumption point of view (Interview 3). Third is the support sustainable agriculture supply chain defining green areas to preserve from urbanization and improving logistics. Fourth, encourage new technologies and innovation in the food products field. Hence, seven strategic guidelines compose the Plan with proposed actions on the previously mentioned themes addressed (Agrifood Strategic Guidelines, 2021, p. 6):

- “Agriculture and Roman farmland

- Agricultural and food identity: the roman signature productions

- The Roman markets and short supply chains

- The future of the Roman food service

- Innovation, sustainability, and research for the future of the Roman agrifood system

- Logistics and flow management and the food safety in Rome

- Rome capital city of agrifood: communication and territorial marketing.”

The interviewees stressed the need to have a plan, a vision, and a program inside the municipality that would address agrifood-related issues, which has been missing, especially from an economic development point of view, along with the great need to combine and create connections between the fragmented city projects (Interviews 1–3). The focus concentrates also on simplifying bureaucracy for citizens and those who work in the supply chain, creating administrative instruments that could facilitate their access to governmental services (Interview 2).

The role of the institution is very prominent in Agrifood: this is confirmed not only by the interviews but also from the strategic guidelines in which actions, instruments, targets, and stakeholders are selected. Among stakeholders mentioned, the city of Rome is the most present. The interviews suggested that, along with the specific thematic and project-related objectives that the city of Rome, as an institution, will have to fulfill, the main and most important outcome of the entire 2030 strategy is to create an instrument for city planning that could be resilient to political changes (Interview 1). In order to achieve this objective, the Plan implemented a governance system that would strengthen the administration role and potential by using instruments and processes, such as the town meeting, the expert consultation, or the joint of two departments, already very well-known from the administration machine but often not used (Interview 2).

The Plan is intended to be “an open, renewable scheme that seeks constant dialogue with citizens and with the social and economic actors of the city” (Agrifood Strategic Guidelines, 2021, p. 25) however, the involvement of stakeholders is very much directed to some specific categories, namely, business, research, or institutions, and less to others such as citizens, non-government organizations (NGOs), and associations. Indeed, the stakeholders that have been involved in the designing process and that have been selected as “enabling stakeholders” of the different guidelines are prominently institutions or businesses related, as the actions of the Plan mainly focus on their areas of work. Hence, policymakers and public managers in this project are at the core of the future implementation of the Plan, as they “drive the whole cart” (Interview 1)—translated Italian expression to say when someone leads something. The involvement of external stakeholders is seen as fundamental in shaping the future of Rome and in maintaining continuity for the actions that would be implemented after the political mandate (Interview 2). However, it seems that the business and innovation lens under which the agrifood system has been analyzed exclude from the equation some part of the food system stakeholders.

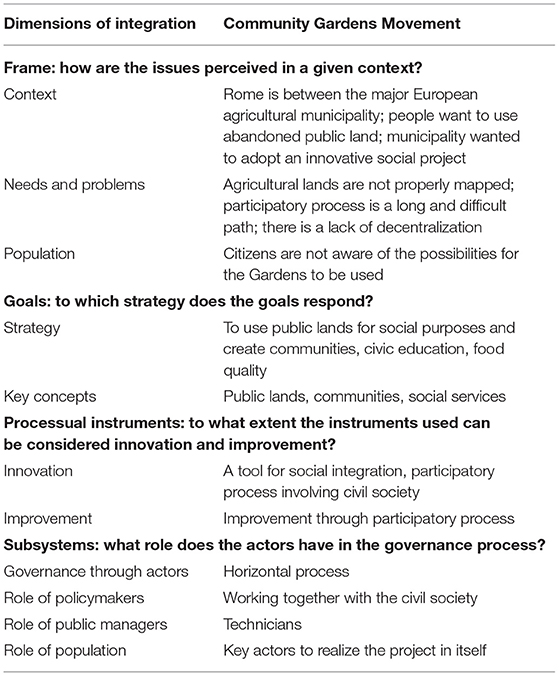

Community Gardens Movement

The community gardens movement in Rome has a very ancient history, which has its roots in the close relationship between city and countryside. In fact, the first evidence of urban gardens in Rome is from the Fascist era, when war gardens were born, many of which were in Roman territory. The first regulation on war gardens dates to 1942: during the war, some citizens, to escape from hunger, took possession of green areas inside the city. The appropriations of state-owned land continued over the years not only as a form of survival but also to maintain numerous ancient customs related to agriculture. The phenomenon stopped during the economic boom, characterized by a general well-being and a change in the food supply system, which became more articulated and industrial. Urban gardens started to come alive again in the early 2000's, not only for supply purposes but also as inclusion and meeting places.

In 2012, Mayor Alemanno placed agricultural land competences under environmental protection and enhanced the urban gardens growth because, since the 1970s, in the city of Rome, the population often appropriated public land. In addition, to put an end to this phenomenon of unregulated activities, civil society started to be involved in projects linked to urban gardens, in collaboration with European projects such as ENI CBC MED3. The aim was to promote urban regeneration and international relations in the capital and at the same time to involve citizens in local governance, starting a participatory process of managing urban gardens.

In 2015, the city administration in charge at the time decided to regulate the community gardens experience with a resolution, still in force. Given the different urban garden formulations in Rome and in order to give proper representation to the growing phenomenon, in recent years, citizens and associations are trying to raise awareness among the administrators about the need to renovate the current regulation. Thanks to Mayor Marino, in 2015, the process for the regulation of the Community Gardens Movement began, and three areas were assigned to associations/citizens in Casal Brunori, Villa Glori, and the Aniene park, which offer important social activities: maintenance of green areas, quality food, and places for socializing. The city of Rome has been awarded for these good practices of urban resilience in 2018 and for being able to create a favorable relationship between associations and institutions. In the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, the phenomenon of Community Gardens Movements has seen an important positive development.

However, the regulation of Community Gardens Movements, while presenting lines of networked governance, struggles with a very complex relationship with institutions (Interview 4 and 5). From an institutional point of view, the analysis highlights the limits of urban garden regulation regarding the real application in the Roman institutional and associative reality. Indeed, the guidelines given by this resolution are not well-received by the bottom–up movements, as they have “unrealistic requirements” such as the need for citizens to identify rural areas already provided with water, information not shared by the public administration (Interview 5 and 6). Hence, on the one hand, the institution aims to carry out a process of civic education in order to avoid the unregulated activities that have always historically characterized this movement; on the other hand, citizens and bottom–up projects are not able to find a space in the instruments provided by the institutions.

Therefore, the main strengths of the Community Gardens Movement, namely, participation and democracy, cannot be realized (Interview 4). From a governance point of view, the Community Gardens Movement is very fragmented, not only among gardens that are spread all over the city but also because of the complex relationship with politics. Interviews to the administration (interview 6) highlighted the complexity of creating a coherent work and building strong relationships with the bottom–up projects because of the political changes concurred in the past years. To facilitate the participative process is very important for politics to have an effective role of mediation with the public administration on the one side and the civil society and third sector on the other side. The results about Community Gardens Movement are summarized in Table 5.

Food Policy for Rome

In 2018, Lands Onlus, an association engaged in research activities focused on food, agriculture, and ecosystem services, and Terra!, a local environmental NGO, paved the way for the bottom–up process of a food policy for Rome. The starting point was a dialogue about raising awareness among local administrations about the need for a food policy able to face the food system's main challenges. The subsequent discussions, joined by other researchers and organizations, identified the Roman food system's strengths, highlighting how, albeit existing, many initiatives related to food lacked connection to each other. These considerations led to the identification of a bigger number of stakeholders to be involved in the analysis and mapping of the roman food system. The group ended up consisting of more than 100 members—both organizations and individuals—including academics, civil society, sustainable development networks, urban gardeners, and farming cooperatives. The proposal was introduced to the municipality trade and environment departments in October 2019: for the first time, the municipality became formally involved in the project and in the discussion with the other relevant stakeholders. It explored the underlying reasons for the need of a Roman food policy, setting 10 priority areas:

1) Access to primary resources (especially land, water and agro-biodiversity);

2) Sustainable agriculture and biodiversity (sustaining organic agriculture and agro-ecology);

3) Short supply chains and local markets;

4) City–countryside relations (integration between different phases of the supply chain; special focus on the Green Public Procurement);

5) Food and territory (strengthening territorial labeling systems, testing a traceability system for the supply chain);

6) Waste and redistribution (sustain leftovers redistribution);

7) Promoting multifunctionality (involving the disadvantaged in the process; therapeutic agriculture; agritourism);

8) Raising awareness among citizens (food and environmental education);

9) Landscape protection (contrasting soil consumption);

10) Resilience planning (agroecosystems as central elements of infrastructures; quantification of agro-silvo-pastoral system's services);

The continuously growing working group called “Food Council of Rome” represents today an informal network of Roman food systems' actors. Guided by a steering committee, its main objective was to establish a privileged channel for communication with the municipality and its administrative offices and define a resolution for an integrated food policy. The lobbying activity has been carried out approaching the interlocutors in different ways, such as sending formal letters to administrative offices and inviting local politicians to join meetings and round tables. The two main commitments set out in the resolution can be defined as follows: establishing a formal Food Policy Council composed of the pre-existing informal council members, municipal representatives, and other stakeholders belonging to the food system, and adopting a food plan. In April 2021, the resolution was finally adopted, and it is intended to remain in force regardless of the next municipal council's political orientation.

Since the presentation of the essay “A Food Policy for Rome” on October 16, 2019, the movement has grown in number of members and fame. For this reason, the group decided to organize itself into a promoting committee. The food policy for Rome committee has launched an advocacy process toward Lazio public institutions to promote sustainable food policy principles. Many meetings took place, and some letters were exchanged between the committee and some Roman departments. The coordination group of the committee started a dialogue with some public executives of the Roman department to write a resolution for the creation of an institutionalized Food Policy. The main role of the civil society (grouped in the promoting committee) was to goad public institutions to create a resolution for the building of a Food Policy. Long and complex bureaucratic process, worsened by the pandemic, finally brought to a resolution signed by all the political forces (Interview 9). “This goal is just the starting point” (interview 7, 8) for the creation of a dedicated institutionalized food policy in Rome.

“A Food Policy should be a program of change and a tool for an agro ecological transition in all the food system; just a Food Policy could lead to this because it starts from a systemic vision of the food system” (Interview 7). This process lasted more than 1 year among mobilizations, disclosure, and internal discussions phases (Interview 8). The power of the project lies in shared requests and in the diversity of the committee's components, especially associations that could give voice to people who need to be represented. Food Policy governance is one of the most relevant problems underlined by the interviews: there are many parallel processes and big lobbies that make the institution of a Food Policy a long and complicated process. “Food Policy doesn't mean different disconnected actions but a planification with a systemic vision. So, there is the need to open a dialogue with big lobbies of the food system and search for an agreement” (Interview 7).

Another issue highlighted by the interviews is that political timings are often too long in comparison to those of the stakeholders, and it could be difficult to combine the respective instances (Interview 8). Public institutions represent a key subject because their role is to make decisions and meet the needs of citizens, besides facilitating citizens' involvement. The vision for the food policy built by FPR could facilitate this process because the integrated measures proposed are intended to deal with changes in the food system. In fact, the core of the FPR mission is to create a welfare policy that includes public–private agreements in many fields, such as agriculture, business, markets, education, urban planning, logistics, and distribution, in order to push public institutions to change vision from sectorial to systemic. “A good governance for an institutionalized food policy should connect different departments to work as one” (Interview 8).

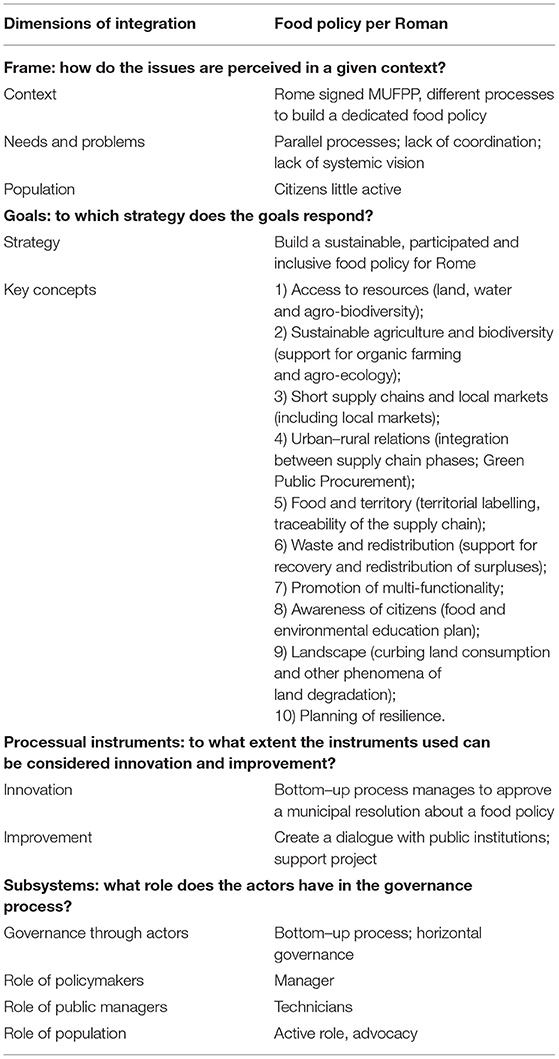

Citizens and the third sector are also key subjects for the food policy institutionalization process. A participative food governance is considered to be essential through a city food council, intended as a way to guarantee a main role to citizens and to little farms, to ensure adequate answers in many fields of interest, to open dialogues with key stakeholders, and to do research and pilot projects (Interview 7). The results about Food Policy for Rome are summarized in Table 6.

The Three Cases Compared

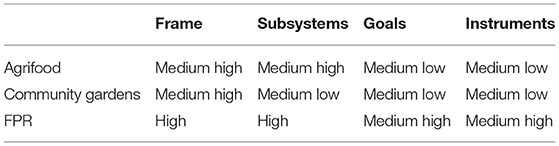

Although the three processes presented are very different between each other, it is interesting to compare them from a policy integration point of view as Table 7 shows. As Candel and Biesbroek (2016) show in their framework, policy integration has a dynamic nature that changes according to the policy frame selected, the actors involved, the goals outlined, and the instruments with which to achieve those goals. All of these dimensions of integration are strongly related to the governance structure of the process analyzed along with the “high” or “low” degrees of policy integration of a specific process (Candel and Biesbroek, 2016).

Table 7. Degree of policy integration divided into four dimensions according to Candel and Biesbroek (2016) framework (source: authors).

Therefore, considering the policy frame dimension, the results show that Agrifood and Community Gardens Movement have a medium high degree of policy integration, meaning that they have an “increasing awareness of the cross-cutting nature of the problem” (ib., p. 219), but they still do not have a holistic approach to the food system that, on the other hand, FPR has. This frame perception influences the subsystem involvement and density of interaction, which appear to have a medium high degree of policy integration in Agrifood Plan process, as there is the “awareness of the problem's cross-cutting nature spreads across subsystems, as a results of which two or more subsystems have formal responsibility for dealing with the problem” (ib., p.221) and the exchanges of information and coordination are dealt with system level instruments. For the Community Gardens Movement, on the other side, the policy integration is medium low because “subsystems recognize the failure of the dominant subsystem to manage the problem and externalities” (ib., p. 221), but the exchange of information is infrequent, and the density of interaction is not coordinated. In addition, for this second dimension, FPR results to have the higher level of policy integration, as “all possibly relevant subsystems have developed ideas about the role in the governance of the problem” (ib., p. 221).

Regarding the manifestation of policy goals, which is the third Candel and Biesbroek (2016) policy integration dimension, Agrifood Plan and Community Gardens Movement perform a medium low level of integration, as the “concerns adopted in policy goals” come also from subsystems that are different from the dominant one, and the conception of policy coherence is somehow part of the awareness, but the range of policies in which the problem is embedded is not as much diversified as for FPR. As for the instruments, while Agrifood and Community Gardens processes some procedural instruments at system level are present and consistency is intended as inter-sectoral mitigation to negative effects (medium low level of integration), FPR provides a “possible further diversification of instruments addressing the problem across subsystems “and consistency is an explicit aim of the governance structure (p. 224).

Moreover, Hartley (2005) provides a historical perspective on governance innovation for which there are three forms of governance and public management—traditional public administration, “new” public management, and networked governance. These refer to competing paradigms that shaped the way administration worked during the years. These conceptions of governance may be related to a specific ideology or historical period; “however, they can also be seen as competing, in that they coexist as layered realities for politicians and managers, with particular circumstances or context calling forth behaviors and decisions related to one or the other conception of governance and service delivery” (ib., 2005, p. 29). Hence, when analyzing a governance process, it is possible to identify different layers of these paradigms that create important implications in the role of policymakers and other actors involved.

Using as lens of analysis Hartley's framework, the three governance processes' results were layered in different conceptions. In particular, Agrifood overlaps the traditional public administration paradigm with the new public management by mixing a strong hierarchical structure, State, and producer centered, focused on public goods delivery with the creation of a competitive environment for the city. Here, efficiency of the system is achieved thanks to improvements in the managerial and organizational process not only of the administration but also of the food system. Yes, the focus has been posed to food supply chain management and planning, thus lacking a circular approach binding together the multiple facets of local food system.

Community gardens movement, on the other hand, proposes a multifaceted governance as a consequence of the history that characterizes this process. Hence, on the one side—the political and institutionalized one; this process respects a very strong traditional public administration conception of the governance structure with a partial orientation to competitive forms of understanding the world of urban gardens and who composes it; on the other side, the bottom–up part of the movement is more oriented to a networked governance conception that recognizes the need of a civic leadership where citizens are co-producers of the governance itself (Tornaghi and Certomà, 2019). Finally, the Food Policy for Rome process perfectly matches the networked governance paradigm, understanding the role of the public administration as leaders and interpreters of the civil society needs, with the aim to provide public value to all, diverse populations.

Discussion and Conclusion

Starting from the idea that urban food policies are place based and therefore each city would have different governance solutions, it is widespread that collaboration and coordination of policies and actions is impeded by an “inertia and silos mentality at the local, national and translocal level, whereby food system issues are typically divided across multiple departments, ministries or state agencies” (Sonnino and Coulson, 2021, p. 26). Therefore, the study of policy governance structures that would help achieve policy integration is particularly interesting. The results provided by this study show three different concurring processes happening in the city of Rome around the topic of food and food policies. What can be drawn from this analysis is that every process performs a different form of governance, implemented according to the actors and backgrounds that compose the process itself.

The different layers of governance, highlighted in Results, inevitably lead to three different conceptions of policy integration for the three case studies selected; as we argue, governance structures and policy integration are strongly related and influenced by each other. For instance, as Agrifood Plan relies on a traditional but competitive structure, led by the need to improve organizational and management efficiency, policy integration is intended as administration department cohesion and coherence. The systemic vision is less present, confirming that most municipalities tend to address food from vertical perspectives such as health, food production, or consumption (Sibbing et al., 2021). The interviews stressed the need to create administration instruments that would help the dialogue between public departments on common issues.

Food Policy for Rome intends policy integration as the need to create an overarching policy, which would link all actors of the food system and all policies related to it, under the same values and goals. Here, integration is conceived not only as coherence and cohesion inside the administration, but mostly among the different parts of the food system and of the population that composes Rome. Finally, the Community Gardens Movement, because of the complex governance previously explained, seeks a dialogue between bottom–up practices and top–down administration systems. Here, integration is therefore intended as integrating the territory with policymaking.

Other cases show that collaborative food governance might be more inclusive and democratic but does not always bring good governance structure (Zerbian and de Luis Romero, 2021). The study on Madrid food strategy demonstrates that implementing instruments to fulfill policy integration “does not directly lead to coherent and uncomplicated network collaboration” (Zerbian and de Luis Romero, 2021, p. 14). The study also shows that the lack of an integrated mindset, which sees food from different perspectives, is necessary to achieve good food governance. In addition, the idea of connecting bottom–up movements with the municipal authority, confirms Sibbing and Candel (2021) study, which delineate the fundamental connection between the design of an integrated urban food strategy and the institutionalization of an ad hoc food governance with the case study on Ede. Sibbing and Candel's study shows that allocating resources, adopting officially the strategy, creating specific units, offices, and staff, are essential governance steps to “bring food policy beyond paper realities” (2020). Finally, all these processes have in common in the presence of policy entrepreneurs, which are intended to be important ingredients to achieve an integrated food governance (Gianbartolomei et al., 2021). Policy entrepreneurs are place leaders that promote an innovative perspective on food policymaking, stimulating, and creating the conditions for a more inclusive food system. It is important to recognize that, in 2021, the liveliness of the debate around the need for a UFP for Rome experienced a particular momentum. In fact, two other important projects intersect with those analyzed in this paper. We refer to the European-funded Horizon 2020 “Fostering the Urban food System Transformation through Innovative Living Labs Implementation” (FUSILLI) and the Metropolitan Strategic Plan. The first has the Municipality of Rome among the partners and intends to support the transformation of the urban food system through the implementation of innovative participatory laboratories. In particular, the goal is to help 12 pilot cities to build their own Urban Food Plan and Action Plan, through the activation of an Urban FOOD 2030 Living Lab. In the context of the city of Rome, FUSILLI will work to support and to the implementation of the Municipal Resolution on the Food Policy, approved in April 2021 (see Figure 2). The second is a project that involves the Metropolitan City and which intends to create a development strategy for the area. Among the forthcoming actions, there is an Atlas of Food, within which a series of priority actions will be indicated, which, once transformed into projects, will involve the 121 Municipalities in a participatory form.

The research presented does not consider these two important initiatives, since they are still in the early stages of implementation, and it would therefore be premature to make an analysis of policy integration and innovation. However, given their scope, one of the possible frontiers of research could be their analysis according to the proposed theoretical model, to provide an exhaustive picture of the complex of initiatives underway around the UFP in Rome and to formulate some policy implications for the development of an integrated and innovative food policy.

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that governance innovation and policy integration are strongly linked and that the conception and application of policy integration changes according to the governance vision that a process has. The two frameworks of analysis used in the study did not provide specific methodology on how to assign high or low level of policy integration (Candel and Biesbroek, 2016) or to identify the different layers of governance innovation to a process (Hartley, 2005); therefore, their application can only be intended as specific to the case studies selected. However, this research shows that the more networked a governance structure is, the more policy integration it will have. As governance systems are layered in their conception of public management, policy integration is a dynamic process that evolves and changes according to the parameters shown.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Bianca Minotti, upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This statement is reflected in economic and social history through many Italian scholars', economists', and intellectuals' thoughts: Sereni, Rossi Doria, Gramsci, Pasolini, and others, such as Mumford, with his “Cultura della Città” (1938).

2. ^Also at the international level in the debate on food policy, the relationship between food and city and between city and countryside is a central element: for example, in the New Urban Agenda, defined within the Habitat III Conference of the United Nations, or in the “City Region Food System” of FAO.

3. ^ENI CBC Med is a EU project on cross-border cooperation in the Mediterranean. Info: http://www.enpicbcmed.eu/en.

References

Agrifood Strategic Guidelines (2021). Available online at: https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/Piano_Strategico_Agrifood.pdf (accessed September 9, 2021).

Calori, A. (2015). “Do an urban food policy needs new institutions? Lesson learned from the Food Policy of Milan toward food policy councils,” in Localizing Urban Food Strategies. Farming Cities and Performing Rurality. 7th International Aesop Sustainable Food Planning Conference Proceedings (Torino: Politecnico di Torino).

Candel, J. J., and Biesbroek, R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sci. 49, 211–231. doi: 10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y

Candel, J. J. L., and Daugbjerg, C. (2019). Overcoming the dependent variable problem in studying food policy. Food Security 12:991. doi: 10.1007/s12571-019-00991-2

Cavallo A, Di, Benedetto, D., and Marino, D. (2016). Mapping and assessing urban agriculture in Rome. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 8, 774–783.doi: 10.1016/j.aaspro.2016.02.066

Cavallo, A., Di Donato, B., Guadagno, R., and Marino, D. (2015). Cities, agriculture and changing landscapes in urban milieu: The case of rome. Rivista Di Studi Sulla Sostenibilita 18, 79–97. doi: 10.3280/RISS2015-001006

Dansero, E., Marino, D., Mazzocchi, G., and Nicolarea, Y. (2019). Lo Spazio Delle Politiche Locali del Cibo: Temi, Esperienze e Prospettive. Rome: Rete delle Politiche Locali del Cibo.

Doernberg, A., Horn, P., Zasada, I., and Piorr, A. (2019). Urban food policies in German city regions: An overview of key players and policy instruments. Food Policy 89:101782. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.101782

Fassio, F., and Minotti, B. (2019). Circular Economy For Food Policy: The case of the RePoPP project in The City of Turin (Italy). Sustainability 11:6078. doi: 10.3390/su11216078

Fattibene, D. (2018). From Farm to Landfill: How Rome Tackles its Food Waste. Available online at: https://www.cidob.org/en/articulos/monografias/wise_cities_in_the_mediterranean/from_farm_to_landfill_how_rome_tackles_its_food_waste

Gianbartolomei, G., Forno, F., and Sage, C. (2021). How food policies emerge: The pivotal role of policy entrepreneurs as brokers and bridges of people and ideas. Food Policy 103:102038. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102038

Hartley, J. (2005). Innovation in governance and public services: Past and present. Public Money Manage. 25, 27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9302.2005.00447.x

IPES-Food (2017). Unravelling the Food-Health Nexus: Addressing Practices, Political Economy, and Power Relations to Build Healthier Food Systems. Brussels.

Lafferty, W., and Hovden, E. (2003). Environmental policy integration: towards an analytical framework. Env. Polit. 12, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/09644010412331308254

Lang, T., Barling, D., and Caraher, M. (2009). Food policy: Integrating Health, Environment and Society (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567882.001.0001

López Cifuentes, M., Freyer, B., Sonnino, R., and Fiala, V. (2021). Embedding sustainable diets into urban food strategies: A multi-actor approach. Geoforum 122, 11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.03.006

MacRae, R. (2011). A joined-up food policy for Canada. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 6, 424–457. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2011.627297

Manganelli, A. (2020): Realizing local food policies: a comparison between Toronto and the Brussels-Capital Region's stories through the lenses of reflexivity and colearning. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 22, 366–380. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2020.1740657.

Mansfield, B., and Mendes, W. (2013). Municipal food strategies and integrated approaches to urban agriculture: exploring three cases from the global north. Int. Plan. Stud. 18, 37–60. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2013.750942

Marino, D. (2016). Agricoltura urbana e filiere corte Un quadro della realtà italiana. Available online at: https://www.francoangeli.it/Ricerca/scheda_libro.aspx?Id=23736 (accesed July 13, 2021).

Marino, D., Antonelli, M., Fattibene, D., Mazzocchi, G., and Tarra, S. (2020). Cibo, Città, Sostenibilità. Un tema strategico per l'Agenda 2030. Roma:ASVIS.

Mazzocchi, G., and Marino, D. (2020). Rome, a policy without politics: the participatory process for a metropolitan scale food policy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020479

Moragues-Faus, A., and Battersby, J. (2021a). The emergence of city food networks: Rescaling the impact of urban food policies. Food Policy 103:102107. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102107

Moragues-Faus, A., and Battersby, J. (2021b). Urban food policies for a sustainable and just future: Concepts and tools for a renewed agenda. Food Policy 103:102124. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102124

Moragues-Faus, A., and Morgan, K. (2015). Reframing the foodscape: the emergent world of urban food policy. Environ. Plan. A 47, 1558–1573. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15595754

Moragues-Faus, A., Morgan, K., Moschitz, H., Neimane, I., Nilsson, H., Pinto, M., et al. (2013). Urban Food Strategies - The Rough Guide to Sustainable Food Systems. Cardiff: Foodlinks. Available online at: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/28860/1/foodlinks-Urban_food_strategies.pdf

Moragues-Faus, A., Sonnino, R., and Marsden, T. (2017). Exploring European food system vulnerabilities: Towards integrated food security governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 75, 184–215. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.015

Seyfang, G., and Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Env. Polit. 16, 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

Sibbing, L., Candel, J., and Termeer, K. (2021). A comparative assessment of local municipal food policy integration in the Netherlands. Int. Plan. Stud. 26, 56–69. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2019.1674642

Sibbing, L. V., and Candel, J. J. L. (2021). Realizing urban food policy: a discursive institutionalist analysis of Ede municipality. Food Security 13, 571–582 doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01126-8

Sonnino, R., and Coulson, H. (2021). Unpacking the new urban food agenda: The changing dynamics of global governance in the urban age. Urban Stud. 58, 1032–1049. doi: 10.1177/0042098020942036

Tornaghi, C., and Certomà, C. (2019). Urban Gardening as Politics, 1st Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315210889

UN Habitat (2015). The New Urban Agenda: Issue Papers and policY Units of the Habitat III Conference. Nairobi.

Vara-Sánchez, I., Gallar-Hernández, D., García-García, L., Morán Alonso, N., and Moragues-Faus, A. (2021). The co-production of urban food policies: Exploring the emergence of new governance spaces in three Spanish cities. Food Policy 103:102120. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102120

Keywords: food policy, policy integration, Italy, food system, food governance

Citation: Minotti B, Cimini A, D'Amico G, Marino D, Mazzocchi G and Tarra S (2022) Food Policy Processes in the City of Rome: A Perspective on Policy Integration and Governance Innovation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:786799. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.786799

Received: 30 September 2021; Accepted: 15 December 2021;

Published: 07 February 2022.

Edited by:

Sara Moreno Pires, University of Aveiro, PortugalReviewed by:

Pablo Torres-Lima, Metropolitan Autonomous University, MexicoBarbora Duží, Institute of Geonics (ASCR), Czechia

Copyright © 2022 Minotti, Cimini, D'Amico, Marino, Mazzocchi and Tarra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bianca Minotti, bWlub3R0aWJpYW5jYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Bianca Minotti

Bianca Minotti Angela Cimini

Angela Cimini Gabriella D'Amico

Gabriella D'Amico Davide Marino

Davide Marino Giampiero Mazzocchi

Giampiero Mazzocchi Simona Tarra

Simona Tarra