- School of Life Sciences, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

Agroforestry is often promoted as a multi-benefit solution to increasing the resilience of agricultural landscapes. Yet, there are many obstacles to transitioning agricultural production systems to agroforestry. Research on agroforestry transitions often focuses on why farmers and land managers chose to adopt this type of stewardship, with less focus on the political context of practitioner decisions. We use the case study of agroforestry in Hawai‘i to explore how agroforestry transitions occur with particular attention to politics and power dynamics. Specifically, we ask, what factors drive and/or restrain transitions to agroforestry and who is able to participate. We interviewed 38 agroforestry practitioners in Hawai‘i and analyzed the data using constructivist grounded theory. We then held a focus group discussion with interview participants to share results and discuss solutions. Practitioners primarily chose agroforestry intentionally for non-economic and values-based reasons, rather than as a means to production or economic goals. Agroforestry practitioners face a similar suite of structural obstacles as other agricultural producers, including access to land, labor, and capital and ecological obstacles like invasive species and climate change. However, the conflict in values between practitioners and dominant institutions manifests as four additional dimensions of obstacles constraining agroforestry transitions: systems for accessing land, capital, and markets favor short-term production and economic value; Indigenous and local knowledge is not adequately valued; regulatory, funding, and other support institutions are siloed; and not enough appropriate information is accessible. Who is able to practice despite these obstacles is tightly linked with people's ability to access off-site resources that are inequitably distributed. Our case study highlights three key points with important implications for realizing just agroforestry transitions: (1) practitioners transition to agroforestry to restore ecosystems and reclaim sovereignty, not just for the direct benefits; (2) a major constraint to agroforestry transitions is that the term agroforestry is both unifying and exclusionary; (3) structural change is needed for agroforestry transitions to be just. We discuss potential solutions in the context of Hawai‘i and provide transferrable principles and actionable strategies for achieving equity in agroforestry transitions. We also demonstrate a transferrable approach for action-oriented, interdisciplinary research in support of just agroforestry transitions.

Introduction

The triple threat of climate change, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity is a major challenge to food system resilience. Re-localization of food systems, shortening supply chains, and adding redundancy to markets can enhance resilience of distribution and market channels (Tendall et al., 2015). At the same time, calls for changes in agricultural production to be regenerative and climate smart abound (Newton et al., 2020; Petersen-Rockney et al., 2021). How we produce food matters for food system resilience.

Agroforestry is widely promoted as a resilience strategy. The term agroforestry was coined in the late 1970's by researchers and development professionals, primarily from high income countries, to describe land management systems that simultaneously increase the productivity of landscapes while also reducing environmental degradation (Bene et al., 1977). Agroforestry has come to encompass farm level technical practices that integrate woody plants and crops and/or livestock for environmental and practical benefits (NRCS, 2013), Indigenous stewardship practices based in ecomimicry (Ticktin et al., 2018; Winter et al., 2020), and a landscape approach “to removing the conceptual and institutional barriers between agriculture and forestry” (van Noordwijk et al., 2018). Subsequently, a large body of literature documenting the ecosystem services of agroforestry systems and optimizing system design for production and environmental benefits followed. Research has thus shown forms of agroforestry can diversify livelihoods (Miccolis et al., 2019), conserve biodiversity (Kremen and Merenlender, 2018), and increase pollination services (Bentrup et al., 2019), sediment retention, and nutrient cycling (Torralba et al., 2018). Agroforestry is considered a natural climate solution (Griscom et al., 2017) as these practices also contribute to carbon sequestration (Chapman et al., 2020) and social-ecological resilience (Quandt et al., 2017; Ticktin et al., 2018), or the ability of a system to continue to function over time despite disturbances (Berkes et al., 2002). As a result, institutions ranging from local governments to international agreements are increasingly including agroforestry as a component of their social-ecological resilience strategies (Rosenstock et al., 2019; Griscom et al., 2020), including National Adaptation Plans and Nationally Declared Contributions (Fortuna et al., 2019; Meybeck et al., 2019).

Yet, how to increase agroforestry on landscapes to meet these targets remains a question. A significant body of research has explored existing farmers' decisions to start practicing, or adopt, agroforestry (Pattanayak et al., 2003; Mercer, 2004; Meijer et al., 2015; Amare and Darr, 2020). Research has largely focused on econometric modeling, showing that producers adopt agroforestry to meet economic goals or to circumvent obstacles like limited labor or depressed prices (Amare and Darr, 2020). For example, when a tree crop price declines, producers may start growing a short-term understory crop between their tree rows to augment their income. Fewer studies have intentionally examined the non-economic reasons for deciding to practice agroforestry, yet studies that do can uncover important narratives (Decré, 2021). The concept of adoption has conceptual and operational limitations, namely that it is an oversimplified model of change and detecting adoption may not be as valuable as understanding the context of the decision to adopt (Glover et al., 2016, 2019). Instead, we use “agroforestry transitions” to describe the multi-year process of land use change from active or fallow simplified agriculture or non-native dominant forest to agroforestry (Ollinaho and Kröger, 2021). At the site level, agroforestry transitions can occur when an existing land steward changes their practices, or a steward gains new access to land and begins practicing agroforestry. These transitions are socially and ecologically complex, often involving a succession of different financing mechanisms, labor sources, and plant and animal species over a number of years. Enabling agroforestry transitions that last therefore requires a better understanding of the drivers and constraints to practitioners' ability to not only make an initial change in practices, but also to continue to practice throughout the multi-year transition process.

Constraints to agroforestry transitions are considerable. Some of the most significant obstacles to agroecological transitions include difficulty accessing land, labor, and start-up capital (Anderson et al., 2019). These obstacles are often more acute for agroforestry practitioners because the trees, shrubs, and other perennials in agroforestry systems take longer to mature and provide a return on investment than annual crops. Therefore, secure, long-term tenure can be a major obstacle to agroforestry (Lawin and Tamini, 2019). High start-up costs and longer returns on investments makes persisting after establishment challenging, and this can be a significant source of risk for practitioners (Buttoud, 2013). Accessing plant material is another challenge as agroforestry systems often include native and other underrepresented plant species, many of which are not readily accessible (Lillesø et al., 2018). Lack of financial incentives, limited marketing for agroforestry products, and lack of knowledge can also be barriers (Sollen-Norrlin et al., 2020).

Although the above research is important for understanding and promoting agroforestry transitions, much of the literature neglects the unequal power dynamics shaping who is able to participate in transitions. For example, focusing on the experience of individual landowners can downplay the power relations that shape who can be a land manager and assumes that all farmers have the power to choose sustainable forms of agriculture (Calo, 2020). A major gap is the need to consider the political ecological context of transitions to agroforestry. This includes how politics and power of the global food system affect agroforestry transitions (Ollinaho and Kröger, 2021). A more power centered analysis of agroforestry transitions can, for instance, illuminate how gender disparities in knowledge transfer affect participation (Duffy et al., 2020), how the power of a state agency can constrain local participation (Islam et al., 2015), how agroforestry interventions can alter labor distribution and displace existing social and economic gains (Schroeder, 1999), or how sustainable intensification narratives can constrain equitable outcomes for smallholders (Nasser et al., 2020). Political ecology approaches that critically examine tenure rights and gender and class power can also reveal how, for example, agroforestry transitions contribute to dispossession and private accumulation, and thus become exclusive (Schroeder and Suryanata, 1996). Additionally, access to political decision-making processes and ideology in agricultural research and development limit agroecological transitions (Isgren et al., 2020), but have received less attention in research on agroforestry transitions. Considering the institutional and social factors that influence agroforestry transitions remains a major gap (Rocheleau, 1998; Molina, 2013; Meek, 2016).

We use a case study of agroforestry in Hawai‘i to examine the politics and power dynamics of agroforestry transitions. Indigenous agroforestry was widespread in Hawai‘i for nearly a millennia prior to European colonization (Kurashima et al., 2019) and was characterized by a diversity of perennial understory and tree crops that were used for food, medicine, ceremony, tools, clothing, and building (Kurashima and Kirch, 2011; Lincoln, 2020). Yet, following European contact in 1778, the Kānaka ‘Ōiwi (Native Hawaiian) population declined an estimated 84% by 1840 (Swanson, 2016). In 1848, a process called the Māhele (division of land), led to land privatization and accumulation by non-Hawaiians (Kame‘eleihiwa, 1992). Sugar and pineapple plantations came to dominate the agricultural and political landscape, and, in 1893, a group of American-backed white businessmen overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. As a result, today Hawai‘i for the most part lacks a tradition of smallholder farms growing diversified crops (Suryanata et al., 2021). This legacy combined with the high costs of land, labor, water, and other structural infrastructure significantly impedes the regeneration of diversified agriculture in Hawai‘i (Suryanata, 2002; Heaivilin and Miles, 2018). Now, less than 8% of the state's agricultural zoned lands are used for growing crops, most products are exported (Melrose et al., 2015; USDA-NASS, 2019), and nearly 88% of food is imported (Loke and Leung, 2013). In response, the state department of forestry, state resilience office, and other public and private institutions have included agroforestry in their resilience strategies, and public discourse in support of agroforestry as a multi-benefit solution is building (Caulfield, 2019).

We interviewed agroforestry practitioners in Hawai‘i to understand how agroforestry transitions are occurring today. We asked: (1) why do people transition to agroforestry, (2) what are their obstacles, and (3) who is able to participate? We find that people's motivations for transitioning to agroforestry are largely non-economic and values-based—most practitioners chose agroforestry intentionally as a form of ecological restoration and/or cultural reclamation, rather than as a means to production or economic goals. The contested values between practitioners and dominant institutions manifests as a suite of obstacles that lead agroforestry practitioners to fall through the cracks, and subsequently to have insufficient access to appropriate information. We highlight how resources external to practitioners and sites—both financial and social capital—are what allow practitioners to circumvent the many obstacles they face, which constrains equitable participation. Finally, we discuss potential solutions to creating more just pathways to agroforestry in this context and transferable lessons for similar transitions.

Methods

Sampling Frame

We conducted non-probability sampling of agroforestry sites in Hawai‘i. We define agroforestry as a continuum of systems that integrate woody plants and crops or livestock (or other tended and harvested plant or animal species) (Hastings et al., 2020). We included people practicing agroforestry for subsistence and/or non-economic benefits as well as practitioners who sell products, including those designated as farms by the USDA, defined as any size plot of land that produces $1,000 or more of agricultural products per year. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, 347 of the total 7,228 farms in the state indicated that they practice at least one of the following types of agroforestry: alley cropping, silvopasture, forest farming, riparian forest buffers, or windbreaks (USDA-NASS, 2019). In the 2012 Census of Agriculture, the question about agroforestry only included two practices—alley cropping and silvopasture—and 38 farms in Hawai‘i reported having these practices (USDA-NASS, 2019). We aimed to sample from practitioners who answered yes to the 2017 Census question; who completed the Census and practice some form of agroforestry but answered no to the Census question (e.g., because they did not know or identify with the practice names used in the Census questionnaire); and those excluded from the Census (e.g., because they did not sell enough product to qualify as a farm).

We developed an initial list of 15 businesses, non-profit organizations, and subsistence farmers practicing some form of agroforestry from informal interviews conducted between August 2016 and June 2020 with farmers, farmer support personnel, and land managers. We then used purposive sampling to request interviews, stratifying by agroforestry practice type and island. We used snowball sampling with initial interviewees to increase the diversity of the participant pool (Bernard, 2018). We also emailed eight extension agents to help identify additional practitioners, which produced a total of three additional interviewees. We continued interviewing participants until we reached saturation, or the point where no new themes arose from additional interviews (Bernard, 2018), in this case 31 interviews.

Interviews and Focus Group

We used a qualitative, inductive approach to develop a relational understanding of both individual and contextual factors influencing agroforestry transitions in Hawai‘i. We used information from informal interviews conducted between August 2016 and June 2020 with farmers, farmer support personnel, and land managers in Hawai‘i and a review of the academic literature on agroforestry transitions to develop a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide included questions about how the practitioner came to steward land in that place using agroforestry practices, what was involved in the transition to agroforestry, what their agroforestry practice is like today, why they integrate trees, what challenges they face, and what would help them and others overcome the challenges to transitioning to agroforestry.

We interviewed a total of 38 agroforestry practitioners representing 31 sites across five of the main islands of Hawai‘i; seven interviews included multiple stewards of the same site. We held interviews via Zoom (due to COVID-19 safety restrictions) from August 2020 to May 2021. Interviews followed the open-ended guide described above, with similar questions and probes for each interview. At the end of each interview, we collected demographic information: highest level of formal education, age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Interviews lasted between 50 minutes and two hours. We recorded the interviews on a local computer using Zoom.

We used the software otter.ai to transcribe the interviews, and then we checked and edited each transcript for accuracy. Next, we imported text transcriptions into the NVivo data management and analysis software package. We used constructivist grounded theory analysis to code themes on the motivators for, and obstacles to, agroforestry practices as well as the ways in which practitioners are circumventing these obstacles (Charmaz, 2014). A single coder (Z.H.) performed the initial coding. Subsequently, the other study authors evaluated the codes, discussed disagreements with the initial coder, and quotes were re-coded as necessary. We recorded all coding procedures to create transparency. To check the coding scheme, we used member checking and looking for negative evidence (Bernard, 2018). We also extracted quantitative data from the interviews to create tables of site and practitioner characteristics.

Finally, we held a focus group meeting via Zoom with a total of seven practitioners from four sites who participated in the first round of interviews. The goal of this meeting was to share preliminary findings with interview participants, facilitate reflection, and discuss possible solutions and pathways forward. This step facilitated knowledge co-creation and social learning among practitioners (Eelderink et al., 2020).

Results

Agroforestry Practices and Practitioners Are Diverse

The 38 practitioners we interviewed ranged in age, gender, and ethnicity. Practitioners ranged from 25 to 75 years old, with a median age of 46. Most (68%) identified as male. Practitioners who self-identified as Kānaka ‘Ōiwi (Native Hawaiian) made up 50% percent of the interviewees. Individuals identifying as white alone were the next most represented group (37%), followed by Asian and Pacific Islander (not Kānaka ‘Ōiwi) (13%).

The practitioners represented 31 sites—families, businesses, or non-profit organizations with land access. The median land area each site tends using agroforestry is 10 hectares, excluding one site that tends over 405 hectares. Over half of the sites are on Hawai‘i Island. Sixty-one percent of sites own or co-own the land they steward. Of the 39% of sites that rent land, most of them (67%) lease from the state's largest private land owner, Kamehameha Schools. The majority of practitioners gained access to former plantation agriculture or ranching lands that were fallow and transitioned from non-native grasses, shrubs, and/or trees to agroforestry. Only four practitioners had been practicing a less diverse type of agriculture (e.g., monoculture vegetable or tree crop) on the same parcel before transitioning to agroforestry. Two sites transitioned actively managed pasture land to agroforestry by planting trees (i.e., silvopasture). Three practitioners inherited family legacy lands that already had agroforestry.

The agroforestry practices at each site are diverse. Half of all sites integrate trees and other plants at the plot level, meaning multiple plants are grown together in one field (e.g., multi-story cropping, alley cropping, or food forest) (Figure 1). Other sites integrate woody and non-woody plants at the field or margin levels (e.g., windbreaks). All sites intentionally grow at least 10 species of plants. The most common plants grown for harvest include canoe plants (plants first brought to Hawai‘i by Polynesian navigators) such as ‘ulu (Artocarpus altilis), mai‘a (Musa sp.), ‘awa (Piper methysticum), and kalo (Colocasia esculenta); introduced “cash” crops including coffee (Coffea sp.) and cacao (Theobroma cacao); and native forest plants such as māmaki (Pipturus albidus), koa (Acacia koa), and ‘iliahi (Santalum sp.). Nine sites integrate animals into their system, including cattle, sheep, goats, chicken, ducks, and fish.

Figure 1. Practitioners in Hawai‘i integrate trees and shrubs with other plants and animals in agroforestry systems ranging from cacao and windbreak systems, to multi-story forests including a range of native and non-native plants for multiple products, to silvopasture with native trees and cattle. Pictured here is an example of a multi-story agroforestry plot in the establishment phase at Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, He‘eia, O‘ahu. Key visible plants include a native, culturally important tree, wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis); Polynesian introductions ti (Cordyline fruticosa) and mai‘a iholena lele (Musa sp.; banana); and an introduced medicinal plant, comfrey (Symphytum officinale).

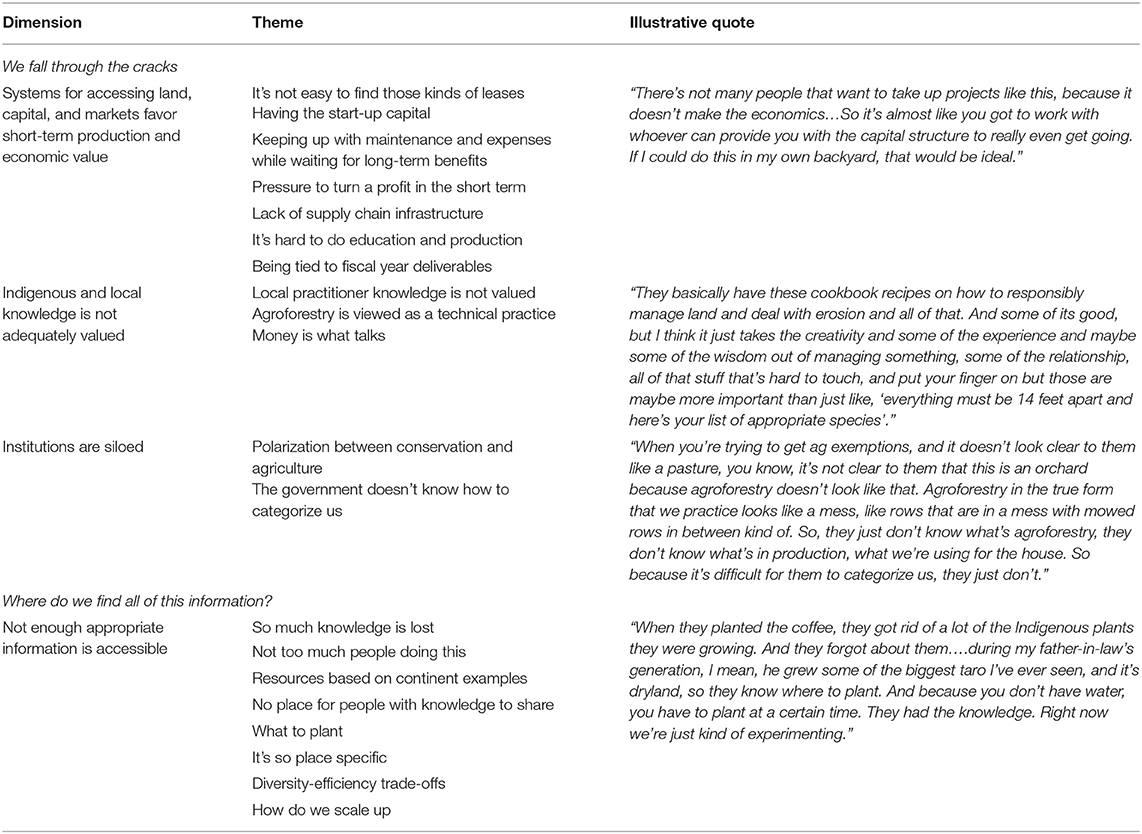

Motivations Relate to Practitioners' Values and the Direct Benefits of Agroforestry

Each person we talked with gave a combination of reasons for transitioning to agroforestry that related to their values and the direct or practical benefits of agroforestry (Table 1). The first reasons most people gave for transitioning to agroforestry related to two values-based dimensions: (1) to restore relationships with ‘āina (land), culture, and ancestors, and (2) to strengthen local communities. The third dimension of themes was the direct or practical benefits of agroforestry. Although not all of the values-based themes are linked exclusively to agroforestry, each practitioner expressed a suite of themes, including agroforestry-specific reasons. The combination of more general themes (e.g., feeding community) and agroforestry-specific themes (e.g., bring the forest back), are what led a practitioner to agroforestry specifically. In the sections that follow, we discuss the themes within each dimension of motivators in detail (Table 1).

Table 1. Factors motivating people to transition to agroforestry in Hawai'i. Some motivators represent values and visions for change that could be achieved through multiple forms of agroecology or sustainable agriculture, not just agroforestry. Practitioners also gave reasons that related to agroforestry specifically (denoted with asterisk).

Values: Restore Relationships

The first dimension of values-based motivators for agroforestry was to restore relationships to ‘āina (land), culture, and ancestors (Table 1). The most referenced theme in this dimension was to reverse the damage caused by plantation agriculture and ranching. Practitioners lamented how “the cattle system has decimated this valley,” “how abused the soils were,” that “what humans have been doing for a long time is taking, taking, taking,” and that “we're in the middle of the sixth great extinction.” The damage they saw was not just environmental. As one practitioner recounted,

“…what I saw was a lot of social injustice, and maybe even in a racial context. And I saw that pretty much against Hawaiians, and that was very disturbing to me. And so that as my ends, have led me to agroforestry as a means.”

Many practitioners saw the links between environmental and social damage as systemic, resulting from colonialism and capitalism. Therefore, their practices were a way to not only “regenerate ‘āina” and “solve a whole bunch of [social] problems that were entrenched in [our community],” but also to assert their values. For example, one practitioner articulated how the drive to accumulate financial wealth that is dominant in “American Western culture” is a major cause of damage and conflicts with their values. Their goal is “to take it back the other way.”

Thus, another theme practitioners expressed was being motivated by the need to take back “kuleana [responsibility] to ‘āina,” restoring reciprocity with land and the environment rather than valuing money and extraction. One practitioner identified this as their “conservation ethic.” They described how they use regenerative agriculture because it allows them to conserve open space, native plants, and water outside of protected areas. Another practitioner identified that they were initially motivated to farm this way by the “back to the land movement.” One practitioner, whose land had mixed native-non-native forest on it when he and his wife bought it, recounted how they came to practice “conservation agriculture,”

“Well see, originally we were gonna plant corn. We were gonna be like regular dirt farmers [laughter] […] But then we realized that we didn't want to destroy [the forest]. It was so peaceful and beautiful. We didn't want to destroy it. […] We are proud of what we do, and we do it because it's a way of giving back and preserving the environment. As a Hawaiian, I believe that I'm doing the right thing. Because that's what I was taught by my elderly people. You don't get rich off what we're doing. But it's rewarding.”

Rather than allowing profit to dictate their practices, this story illustrates how many practitioners prioritize their kuleana (responsibility) to ‘āina first. This practitioner, like many others, chose to restore a reciprocal relationship with ‘āina and culture, rather than remain disconnected from the negative environmental effects of conventional agriculture. Similarly, another practitioner articulated,

“We like to believe there's a balance, there's a way we can be growing the food and taking care of the forest at the same time; we don't need to clear the forest just to grow the food, we keep doing both.”

Relatedly, some values rooted in Indigenous culture and ‘ike kupuna (ancestral knowledge) motivated people to practice agroforestry specifically, rather than another form of regenerative agriculture. First, was the theme that “the template was created by our ancestors.” For example, practitioners described going through historical records to find that “historically, the space was known to have a very large food forest system, for lack of a better term.” The template for agroforestry already existed pre-colonization. Practitioners articulated how they wanted to use this template because of the immeasurable value of the knowledge held in these systems, pointing out, “our people have been collecting data for 1000s of years.” Trying to re-establish these systems was therefore an easy decision: “if it's not broken, don't change it.” Second, a reason for practicing agroforestry following ‘ike kupuna was “to bring back a part of that history” and to reclaim Kānaka ‘Ōiwi identity from colonialism and plantation agriculture. One practitioner described how the sugarcane plantations were “a really decorated piece of history” in their childhood. They saw their access to land now as an “opportunity to change that historical fabric” and “reaffirm our identity.” Similary, another practitioner echoed, “I'm learning, or sometimes I think that I'm re-learning, how to be a mahi‘ai [farmer], because, you know, we have these agricultural roots as kānaka.”

Next, many practitioners articulated that they wanted to bring the forest back. This was described again as a response to degradation of ranching and plantation agriculture, and a way to reconnect with ‘āina. One practitioner expressed that when they were able to buy land, “it was an opportunity to try and change what had happened and go back to a system that was more sustainable; so the whole drive behind this project is to re-establish the forest.” Their business views sustainable harvest of timber and non-timber forest products as a way to make forest restoration economically viable. Speaking about native forest restoration he said, “That's the goal; and the goal is not having to go out and beg somebody for money to do it.”

Relatedly, another motivation for agroforestry was to have materials for cultural practices. One practitioner grew forest plants in partnership with a hālau hula (Native Hawaiian dance school), so that they could limit the amount they harvest from remnant native forests above their site. Bringing back the plants in this case was not just about the harvest. The practitioner described how increasing access to the plants was also about bringing back culture, “Kumu [Teacher] always says that some of the holier chants that we do there hasn't been heard in that area for maybe a couple 100 years.” Practitioners were themselves, or had relationships with, carvers, hula practitioners, lei makers, and weavers. The wood, gourds, ferns, flowers, and other plants that practitioners grow reinforces their ability to restore relationships with ‘āina, ancestors, and culture.

Finally, practitioners described practicing agroforestry because “it's for future generations.” One practitioner described using Indigenous agroforestry to “make sure that this mountain will be able to gather and retain water for our great, great, great, great grandkids right down the line.” Many of the trees that practitioners grow, like ‘iliahi (sandalwood; Santalum sp.), take at least 30 years to mature. Instead of putting pressure on himself to have an abundant agroforest in his lifetime, one practitioner said this work requires a “generational mindset.”

Values: Strengthen Local Communities

The second dimension of values-based motivators for agroforestry practices that emerged from the interviews was to strengthen and elevate local communities (Table 1). The first theme in this dimension was choosing agroforestry to “feed our community,” which was articulated by over half of the practitioners we spoke with. Although practitioners could feed their communities through other types of agriculture, many practitioners expressed that they chose agroforestry as a way to produce a diversity of food, over a long time. For example, agroforestry was the specific way one practitioner chose to feed their community because, “the agroforestry that we do is mostly just trying to think long term, like, how do you feed your community longer than just for one grant cycle?”

Second, and interrelated with the first, practitioners were motivated by their community's health and wellness. For instance, one practitioner expressed that they practiced agroforestry because, “healthy land and healthy people, can't really separate those two things.” Another practitioner explained how agroforestry aligns with their goals to support healthy communities:

“…the la‘au lapa‘au [medicine] aspect, like seeing that the ‘āina [land], the forest, is our medicine, is our pharmacy. That is a big part of what we do. A lot of us might think agroforestry is just agriculture and forests, but it's also medicine. Right, because a lot of those food crops like mountain apple, for example, is a medicine itself.”

Next, practitioners expressed how they were motivated by youth development and job creation. One practitioner said, “my motivation is always children” and another, “…we see the growing of food as a means to growing young people in our community.” A Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioner shared, “working and being conditioned to do only certain jobs for local boys, I wanted to kind of change that stigma.”

Finally, almost a third of practitioners were motivated to inspire others and to create a model of how to practice agroforestry today. For several practitioners this involved inspiring others to grow food at home. For example, one practitioner explained that “what I'm focused on building here, on my land, is a demonstration center, an educational center for tropical subsistence farming.” Others were more focused on larger models. One practitioner said, “the mission was to create a model to revitalize agriculture in Hawai‘i that was economically viable and could be scaled.” Although many of these same practitioners identified that a template for agroforestry was created by their ancestors, they also experienced the challenges to reclaiming this history and knowledge in the current political-economic context and wanted to create a model to make it easier for others.

Direct or Practical Benefits

While it was common for practitioners to open with how their values motivated them, many also went on to share motivations related to the direct benefits of agroforestry. First, almost half of practitioners discussed how they practice agroforestry for their own health and wellness. Practitioners shared testimonials such as, “I have not had to go to a therapist or a psychologist ever since I started agroforestry.” They also described how mixed forest systems “nurture us on a spiritual and emotional level,” “really ground you,” are “so peaceful,” and “make us feel super good.” Other practitioners expressed, “I'm definitely motivated to plant more trees just because I like trees,” “we're tree people,” and “I just feel safe in a forest.”

Second, almost half of practitioners expressed that they were motivated by the need for multiple types of products. Practitioners talked about how agroforestry, especially traditionally in the Pacific and other parts of the world, is “out of need,” for example, for food, medicine, fiber, and fuel. Agroforestry also allows practitioners to “diversify the food that we're growing” and incorporate “succession harvesting.”

Third, nearly half of practitioners chose agroforestry to build soil fertility and health. Many practitioners talked about using trees to produce organic matter to incorporate into the soil, for instance through “chop and drop.” Some practitioners incorporated animals or nitrogen fixing trees to reduce the need to buy expensive fertilizers. In this way, agroforestry was a means to overcome an obstacle to conventional agriculture.

Next, practitioners described choosing agroforestry because of the strength of planting an ‘ohana (family). For example, one practitioner observed about their trees, “when they're with each other they thrive as opposed to being out in the pasture alone.” Another practitioner acknowledged this as the importance of “symbiotic relationships.” A few practitioners discussed how they incorporate a diversity of perennial plants, especially natives, to host beneficial insects for pollination and pest control.

Relatedly, practitioners explained that they incorporate trees to protect a crop, particularly through wind protection and shade. Although most practitioners started stewarding land with the intent to transition the site to agroforestry, a few practitioners made the decision later in their stewardship of a site. Two practitioners cited that their values led them to initially grow a single perennial or culturally important crop (i.e., cacao or kalo), yet a few years into stewarding, severe wind damage to the crop led them to incorporate trees as protection. As the cacao farmer explained, “So the agroforestry component of it, on the farming side, really came totally out of necessity. It wasn't like I set out to build a forest, I had to learn that I needed a forest.”

Finally, practitioners described choosing agroforestry as a means to decreasing labor costs and maximizing productivity, both indirect economic motivations. One theme was that agroforestry requires less maintenance, in large part because tree cover decreases growth rates of weeds. For example, when asked why did you decide to integrate trees and crops, one kava (Piper methysticum) grower explained, “My kava buyer asks me that question all the time. He's like, ‘Oh, they grow faster in the full sun.' Well, they do. But there's a lot more maintenance.” Similarly, another theme echoed by several practitioners was that, “agroforestry is definitely part of a strategy to hold back invasive plants and weeds in some areas.” A third theme was to make the most of steep areas not suited for annual crops and areas between trees in existing orchards. A practitioner who transitioned an orange orchard to agroforestry described how the previous steward had planted the tree rows too far apart, wasting sunlight, and creating more area to mow. She explained how she decided to transition to agroforestry, “I'd rather put something there, but it's not quite enough to plant another row of orange trees, so it's good for rotation of bananas, or pineapples, or some of those shorter term crops that never get too big.”

These last three themes show how some practitioners chose agroforestry as a means to circumvent obstacles like limited labor or unfavorable site conditions and achieve economic productivity rather than choosing agroforestry as a purposeful destination itself. Only one practitioner cited that they transitioned to agroforestry to diversify their income, a direct economic benefit.

Agroforestry Practitioners Face Common and Unique Constraints

Some of the obstacles interviewees expressed are not unique to agroforestry; they are shared by other agricultural producers in Hawai‘i, especially small farmers. Top themes of structural obstacles included access to land, labor, capital, and infrastructure. For example, the high cost of living, regulations that prevent living on agricultural land, agricultural theft, and the pressure to prove value relative to real estate development were important challenges throughout agroforestry transitions. Practitioners expressed that the lack of policymaker support for agriculture and forestry challenged their ability to establish and persist. Failure of the government to enforce regulations, for instance around environmental protections for land clearing which can cause erosion and poor water quality on practitioners downstream, was another challenge.

Practitioners also identified common ecological and practical management obstacles. The top referenced theme was nonnative or invasive plants and weeds. As one practitioner lamented, “the more we clear, the more we have to maintain.” Several practitioners who had more established agroforestry practices felt burdened by the risk of new pests and diseases being introduced and viewed this as a failure of government regulation. Disturbance from pigs and deer was another obstacle at all stages of transitions, requiring many practitioners to invest in costly fencing. Lack of water rights and poor soil quality, legacies of the plantation era, especially challenged practitioners in the establishment phase. Additionally, climate change, drought, wind, floods, and fire were key obstacles.

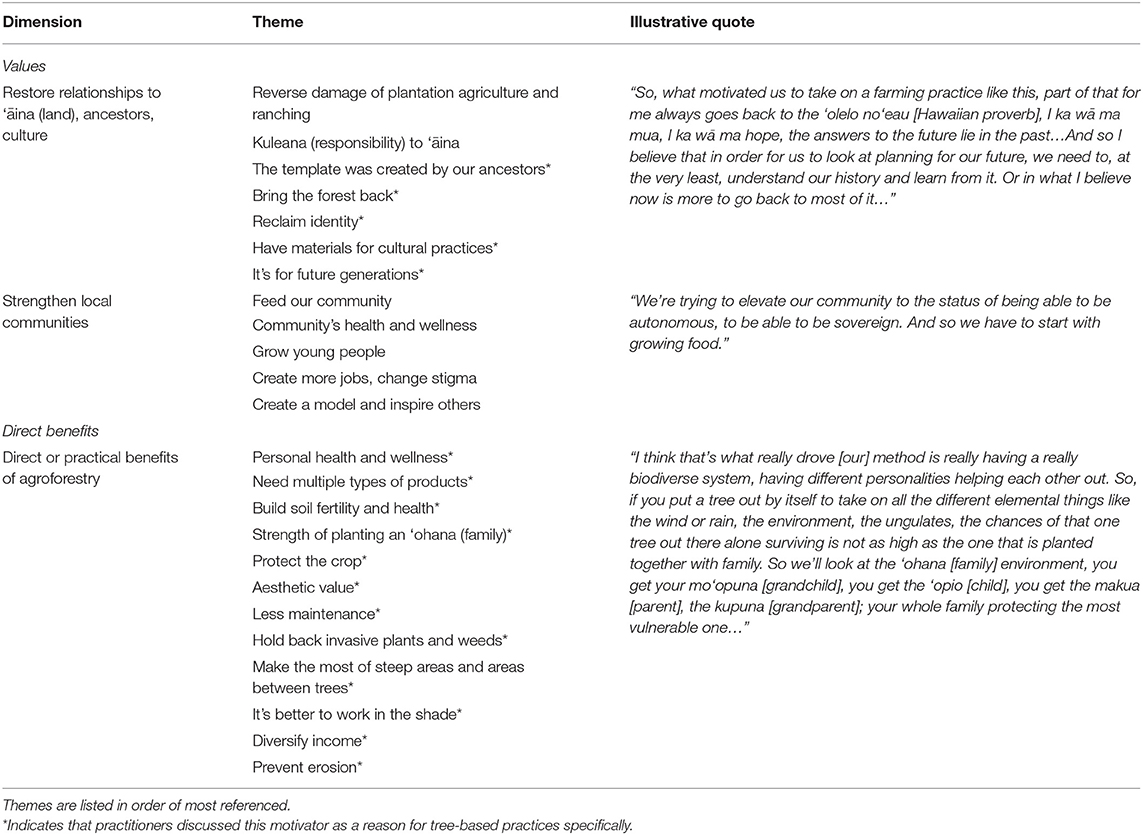

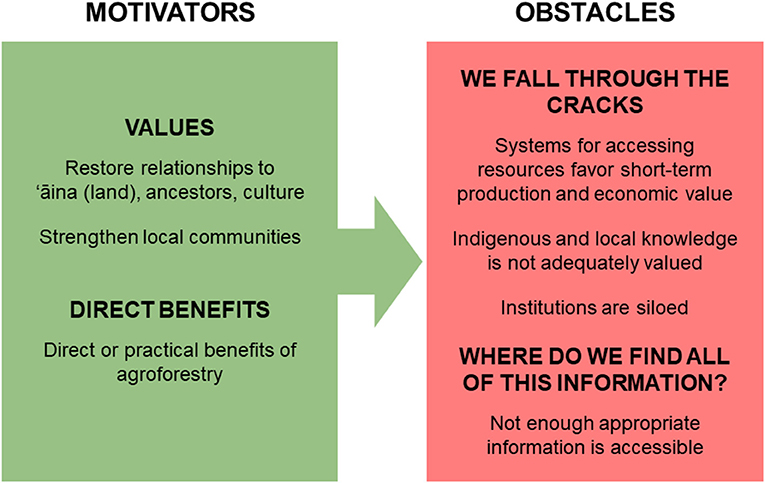

However, our interviews revealed that agroforestry practitioners in Hawai‘i face an additional set of unique constraints. As described in the previous section, most interviewees chose agroforestry intentionally, primarily for values-based reasons rather than as a means to achieving production or economic goals. These values conflict with the dominant values, institutions, and systems of resource access in Hawai‘i today causing practitioners to “fall through the cracks” and subsequently ask, “where do we find all of this information?” (Figure 2). In the following sections, we describe the four dimensions of themes of agroforestry-specific obstacles that emerged from the interviews (Table 2).

Figure 2. Practitioners in Hawai‘i were motivated to practice agroforestry largely by their values, but also the direct or practical benefits of agroforestry (green box). These motivations, and the resulting diverse agroforestry systems, directly conflict with the dominant values, institutions, and systems of resource access, which produces a suite of agroforestry-specific obstacles (red box). Institutions include local, state, and federal agencies and organizations that support and regulate practitioners as well as social norms and worldviews. For themes and illustrative quotes, see Table 1 (motivators) and Table 2 (agroforestry-specific obstacles).

Systems for Accessing Land, Capital, and Markets Favor Short-Term Production and Economic Value

The first dimension of themes was that systems for accessing land, capital, and markets favor short-term production and economic value. Many practitioners echoed the theme that “it's not easy to find those kinds of leases.” Agroforestry practitioners struggle to secure long-term tenure, due to high land prices and landowners only offering short-term leases.

Even with land access, agroforestry practitioners still face other economic obstacles, which fell into three themes. The first was having the start-up capital. The second was keeping up with maintenance and expenses while waiting for perennial plants to mature. For example, one practitioner described how windbreaks need to be established at least a year before planting cacao, and then the cacao takes 3–4 years to mature, “So, it's a good four-to-five- year window of nothing but negative cash flow.” Third, practitioners felt constrained by the pressure to turn a profit in the short term. While this pressure can motivate agroforestry transitions, such as when orchardists plant annual crops between their trees for short-term income, the practitioners we interviewed primarily chose agroforestry as an intentional system, not just for economic benefits, and thus saw this pressure primarily as a barrier. Because of pressure to turn a profit in the short term, the cacao farmer first planted cacao in monoculture, which left the the crop vulnerable to wind: “ironically, everything that led us to our first big mistake, that led us to where we finally are now, had to do with trying to run fast enough to make money.”

Two themes related to how practitioners try to circumvent economic obstacles. The first theme was “it's hard to do education and production.” Some practitioners use agricultural production or education grants to augment cash flow. Yet, practitioners expressed that time spent on education programs takes away from time spent in the field, growing plants for harvest. Many practitioners felt stuck relying on grants to cash flow their sites instead of becoming financially self-sustaining through production. Second, “being tied to fiscal year deliverables” limits practitioners' ability to manage “when nature is ready for me to do it, as opposed to when the fiscal year requires me to do it.” Grants can be good for start-up, but without proper planning, it can be difficult to keep up with maintenance and cash flow until the perennials start to produce. One practitioner expressed, “one of the things that's really hard is whenever you get grants and things from nonprofits, it lasts a few years, and then you have to re-compete; to grow a forest, you need 100 years.”

Indigenous and Local Knowledge Is Not Adequately Valued

Second, many agroforestry practitioners fall through the cracks because of a lack of value for Indigenous and local knowledge. The most referenced theme was that local practitioner knowledge is not valued. For example, practitioners described how agroforestry definitions and recommendations center knowledge and experience from the continental U.S. One practitioner expressed this frustration about a funder, “their thing was they wanted us to be following American forestry practices, so, for example, planting koa on a 10 foot by 10 foot grid, and for us, and on our terrain, that's just not really realistic or practical and didn't really make sense to us.”

Another example of how practitioners experienced the lack of value for local knowledge was through cultural appropriation. Agroforestry does not have one parallel Indigenous agroecosystem. Instead, it is a Western construct that is an umbrella term for a variety of place-based practices that integrate trees and other plants in various arrangements and intensities. For example, in Hawai‘i forms of agroforestry may be called pākukui (Lincoln, 2020), kalu‘ulu (Menzies, 1920; Kelly, 1983; Quintus et al., 2019), or ka malu ‘ulu o lele. One practitioner explained how using the term agroforestry can therefore exclude the participation of Indigenous people who are familiar with integrated forest-agriculture practices, but not the term agroforestry. Another expressed that labels like permaculture and agroforestry are “just whitewashing Hawaiian culture.” Many of the Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioners we spoke with felt uncomfortable with the use of the term. One explained the source of their discomfort,

“And most of that has to do with the fact of our historical references show of this older style and technique and this exact thing […] In the end, I still want to be able to find a term that can credit our works that we do to the people that are of the place, the other Indigenous organisms that had that same relationship and style and study that we're all today putting scientific terminology labels on.”

Another related theme in this dimension was that agroforestry is generally framed as a technical practice. One permaculturalist commented, “Agroforestry is an excellent system, but it doesn't include those ethics.” A Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioner explained that their stewardship system contains significant cultural knowledge, so “a lot of the difference between agroforestry and [our system] is just that, ‘culture'; And what we stress is no more agriculture without culture.”

Then, the theme “money is what talks” further illustrated the conflict in values constraining practitioners. A Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioner said it had been challenging “in a world that's really driven by economics in numbers” to make initiatives like theirs fundable, because they “want to look at the social good of what they're doing.” A major challenge is the mis-match in metrics of success: “How do you measure our kupuna [elders] planting a tree with their mo‘o [lineage], that feeling, that reciprocal exchange between environment, their relationship to the environment and us, kānaka [Hawaiians]?” The extra work that local and Indigenous practitioners do to translate between value systems is a major constraint to equitable transitions. Another Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioner described how in a new field that they had recently opened up, they had to choose between planting ipu (gourd; Lageneria siceraria), which has important cultural value for hula (dance) and food, or lilikoi (passion fruit; Passiflora edulis), which a company that makes value-added products for tourists already committed to buying. Although they are motivated to practice agroforestry as an act of resistence to capitalism, practitioners still struggle to acheive financial sustainability within the system.

Institutions Are Siloed

Finally, agroforestry practitioners fall through the cracks because their practices do not fit within the silos of regulatory, funding, and other support organizations, and of dominant worldviews that separate agriculture and forests. The first theme in this dimension was the polarization between conservation and agriculture within government, private organizations, and social norms. One silvopasturist described this as an issue of “philosophy,” explaining, “I think one of the greatest challenges for both the livestock industry and for the conservation community is trying to find the middle ground that exists between the two; you know, we're polarized.”

The second theme was that “the government doesn't know how to categorize us.” Because agroforestry crosses sectoral silos, government agencies and other organizations that remain siloed often struggle with how to categorize agroforestry practices, limiting practitioners' access to support. For example, one practitioner described how they struggled to qualify for agricultural exemptions because the property tax office could not tell what part of the land was “in production” because the agroforestry practice did not look like an orchard. Another practitioner explained how they fail to qualify for federal farm benefits because they produce a native forest plant, which is not on the approved list of crops. They added another reason they struggle is because their approach is to restore the forest ecosystem around the plant: “that's one reason why we fall through the cracks, because we're not looking at it as we're producing one particular crop.” Additionally, policymakers' siloed conceptualizations of agriculture limit practitioners' access:

“When you're talking to policymakers, and they have no idea what you're talking about, as far as agroforestry, it's very difficult to try and get them to attach to the idea that we need leases extended. You know, for them, it's just like, ‘Well, why don't you just go do farming the way everybody else does farming?'.”

Not Enough Appropriate Information Is Accessible

The dimensions of agroforestry-specific structural obstacles produce a secondary dimension of challenges: not enough appropriate information is accessible (Table 2). The most referenced theme was “so much knowledge is lost.” Colonization, land dispossession, plantation agriculture, and ranching severely marginalized Indigenous agroforests and their stewards in Hawai‘i. Many practitioners motivated to restore these systems explained how the lack of Indigenous and local knowledge was a major barrier to their ability to transition to agroforestry. While many practitioners are reclaiming this knowledge, practitioners expressed two additional themes of obstacles: “there's not too much people doing this” and “there's no place for the people with knowledge to share.” Further, practitioners expressed difficulty knowing what to plant and that agroforestry is “so place specific.” Another theme was challenges related to how to balance diversity-efficiency trade-offs. For example, one practitioner acknowledged that “that's why there's monocrop; it makes everything easier.” Thus, practitioners are continuously experimenting to figure out, “how can we create an agroforestry system where we can still keep some of that principles, easy harvest and stuff, in place and still have a biodiverse system.” Finally, a theme was “how do we scale up?.” Many people have retained home garden practices, but figuring out how to practice on the scale of 5, 10, or 100 acres raises many questions.

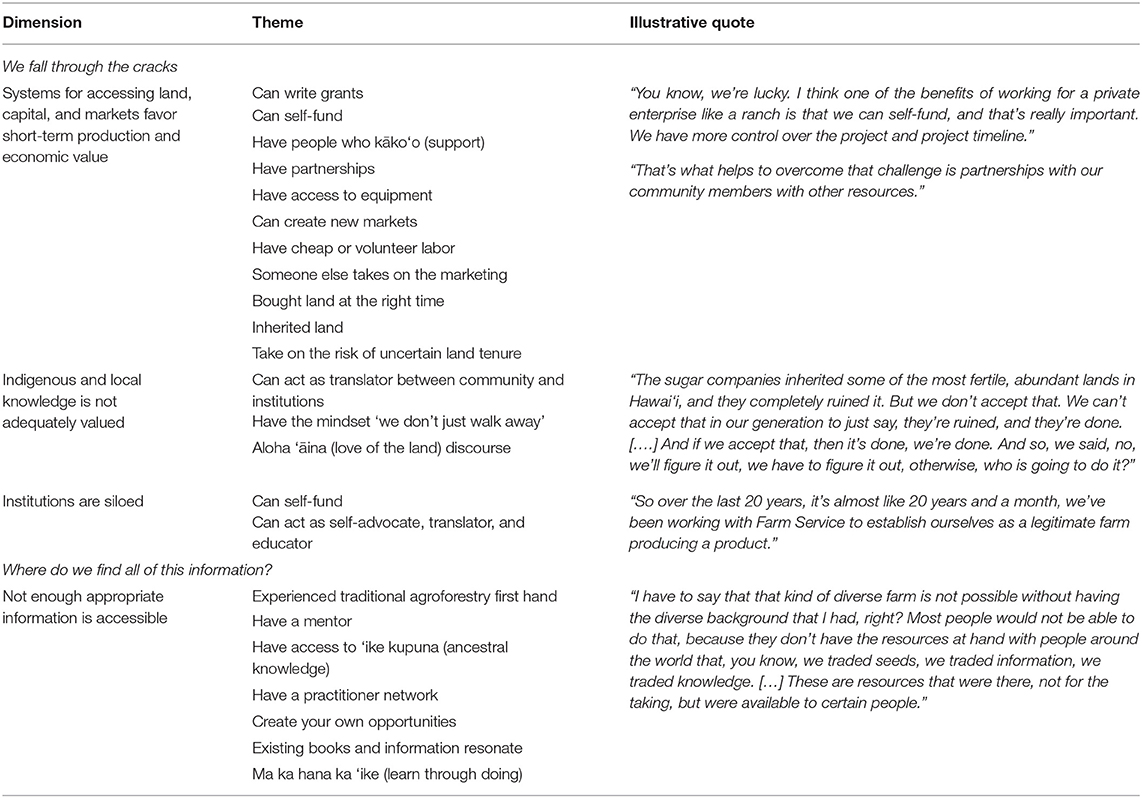

Access to External Resources Shapes Who Gets to Practice Agroforestry

Practitioners rely on resources external to their site, especially financial and social capital that are unequally distributed, and a strong commitment to their values in order to participate in agroforestry transitions (Table 3). Reliance on external resources, especially financial capital, translates to new farmers on the whole in Hawai‘i being “older, wealthier, and less diverse than the general population” (Suryanata et al., 2021). Yet, we interviewed a higher Kānaka ‘Ōiwi population by percentage than the general population. This provides an opportunity to understand the resources, networks, and institutions that allow these practitioners and others to participate in agroforestry transitions. Here, we describe these factors as they relate to each dimension of agroforestry-specific obstacles.

Table 3. Factors influencing practitioners ablity to participate in transitions to agroforestry in Hawai‘i related to each dimension of agroforestry-specific obstacles.

Systems for Accessing Land, Capital, and Markets Favor Short-Term Production and Economic Value

Four themes arose as factors broadly influencing access to land, capital, and markets. First, nearly a third of practitioners cited their ability to write grants as an advantage. Eighty percent of practitioners we interviewed had attended at least some college, and almost half of those practitioners had graduate degrees. The skills gained through academic education helped people access financial resources: “we were lucky because of our professional background, that we can write grants […] that's a disadvantage that other farmers have.” Yet, access to academic education is unequally distributed. Further, grants are often tied to educational programming deliverables, which align with values-based reasons for choosing agroforestry, yet reproduce obstacles such as taking time away from production and being tied to fiscal year deliverables. This theme also included other forms of financial assistance like incentives and cost-share programs. Yet, again, accessing these funds required extra time, knowledge, and persistence to learn the rules and figure out how to leverage the funds to support their vision of agroforestry. Although grant funds have allowed many people to begin to transition to agroforestry, there was a sense that the burden of administration was unsustainable, and the amount of time left to actually tend their agroforestry systems was insufficient.

Second, the ability to self-fund influenced who could participate. This looked different in each case. Some practitioners held a full time off-farm job, had a spouse with a full time off-farm job, used retirement funds or other personal savings, or used a cash inheritance. Next, many people spoke to the value of two interrelated themes: having people who kāko‘o (support) and having partnerships. People who kāko‘o share their time, skills, equipment, and other resources in support of the practitioner transitioning to agroforestry. Similarly, partnerships and collaborations between sites, organizations, and/or institutions provided access to resources. For example, six practitioners either engaged other partners to help purchase land or partnered with wealthier individuals who already owned land, often through employment. Although in these cases practitioners have long-term tenure, this comes with a trade-off of decision-making power. As one practitioner said of other Kānaka ‘Ōiwi in their position, “A bunch of us got people watchin' over our shoulders.”

Three themes emerged around land access specifically. First, was that practitioners “bought the land at the right time,” often referring to when land was less expensive after the sugar plantations closed. This was the case for some of the eight practitioners who owned land as a single ‘ohana (family) unit and said they would not have had the means to self-fund today. Another theme was inheriting land as a group of descendants. In these four cases, shared decision-making challenges and pressure to sell by some co-owners challenged secure land tenure. A third theme specific to land access was taking on the risk of uncertain tenure. Nearly one third of sites leased the land that they steward, and of those, only a few had leases longer than a few years, including three commercial cacao enterprises with 30-year leases. Short term leases can carry a significant burden of risk. For example, one practitioner described how they recently lost access to the land they had been transitioning to agroforestry: “we're just now getting to the point where this piece of land is giving us the most special fruits that we've been waiting years on, and now we have to leave that land.”

Finally, two themes related to market access. First, practitioners expressed that their ability to create new markets has helped them persist. For example, one grower explained how they created markets for dye plants and lei flowers by building relationships with cultural practitioners. The second theme was having someone else take on the marketing. For example, a māmaki grower explained that “those kinds of regulations is on them [the buyer], the value added processing part, they're taking it on” and as a result, practitioners can just grow, harvest, and sell the wet māmaki. She added, “it's such a joy.” Having an intermediate buyer who handles distribution and marketing to consumers is key and well established for ‘ulu (breadfruit; Artocarpus altilis), māmaki (Pipturus albidus), and ‘awa (kava; Piper methysticum) on Hawai‘i Island. But this is still a major obstacle for most other crops.

Indigenous and Local Knowledge Is Not Adequately Valued

The ways practitioners deal with the lack of value for Indigenous and local knowledge fell into three themes. First, practitioners expressed the theme that they persist by being able to act as a translator between community and institutions, such as policymakers, funders, and government agencies. The extra unpaid work is disproportionately required of Indigenous practitioners and takes them away from production. This means Indigenous practitioners get behind non-Indigenous practitioners in agricultural skill development and production. One Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioner expressed that, “We're lucky because, brah, Hawaiians is very resilient. And we can adapt, and we figured out how to communicate […], but it's so exhausting…”

The second theme was that practitioners have the mindset “we don't just walk away.” Despite their success in transitioning to agroforestry hinging on their ability to dedicate extra unpaid time, practitioners expressed their feeling of responsibility to persist. For Kānaka ‘Ōiwi practitioners especially, this responsibility and persistence is interlinked with their motivations to restore relationships with ‘āina, ancestors, and culture.

Finally, practitioners' strength also comes from aligning their work with aloha ‘āina discourse and the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Aloha ‘āina is a discourse and set of practices that organizes and engages a diverse Kānaka ‘Ōiwi community for political action (Trask, 1987; Baker, 2021). This discourse is enacted through other forms of Indigenous agroecosystems such as lo‘i kalo (wetland taro; Colocasia esculenta) and loko i‘a (fishponds). However, in the case of lo‘i kalo, for example, there is a clear vision of what these systems are and how they are both a form of cultural revitalization and food production. Since agroforestry does not have a single parallel Indigenous land use practice, and so much of the knowledge is lost on how Indigenous agroforestry systems were managed to be a significant form of food production, practitioners still struggle to persist despite the support from aloha ‘āina discourse.

Institutions Are Siloed

Two themes emerged illustrating who is able to transition to agroforestry despite siloed institutions. First, practitioners who can self-fund are able to transition. This included practitioners with the financial resources to persist without the support of tax exemptions, cost-share incentives, grants, and other funding. The second theme was practitioners who can act as a self-advocate, translator, and/or educator. In these cases, practitioners took extra time to translate their motivations and practices into the current production-focused system and educate institutions about how their practices fit. This is similar to how practitioners deal with the lack of value for Indigenous and local knowledge. One practitioner stressed that rather than reaching out for support from government agencies, they are now taking the approach of just “doing it on our own.” The few strategies that practitioners use to circumvent this dimension of falling through the cracks—the ability to self-fund and extra time—has an exclusionary effect on practitioners who lack the resources to go at it alone.

Not Enough Appropriate Information Is Accessible

Several themes arose surrounding practitioners' ability to circumvent the lack of accessible appropriate information. First, nearly a third of practitioners had experienced traditional agroforestry, mostly through visiting other Pacific Islands like Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Micronesia, and the Philippines—either on self-funded trips or for an off-site job. Seeing other agroforestry systems provided “good inspiration” and a way to gain “first-hand knowledge,” yet requires significant time and funds to do so.

Second, almost a third of practitioners identified the theme that having a mentor helped them. Then, for practitioners trying to build from Kānaka ‘Ōiwi models of agroforestry, many went through a process of “triangulating knowledge” since no complete information source is available. Practitioners described combining information from different sources including those falling into the themes of experiencing traditional agroforestry first-hand, accessing ‘ike kupuna (ancestral knowledge), having a practitioner network, and ma ka hana ka ‘ike (learning through doing). Practitioners accessed ‘ike kupuna through archival research or, in only a few cases, from family members. Although historical records are a valuable source of information, it can take significant time to find and translate from ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i (Native Hawaiian language), which practitioners are not compensated for, although some conducted this research as a part of an academic degree program to circumvent this obstacle. Similarly, another theme was that practitioners persisted in part because of their ability to create their own opportunities to learn. Finally, some practitioners also identified that existing permaculture and agroforestry resources helped them, pointing to how this information resonates with some people.

Discussion

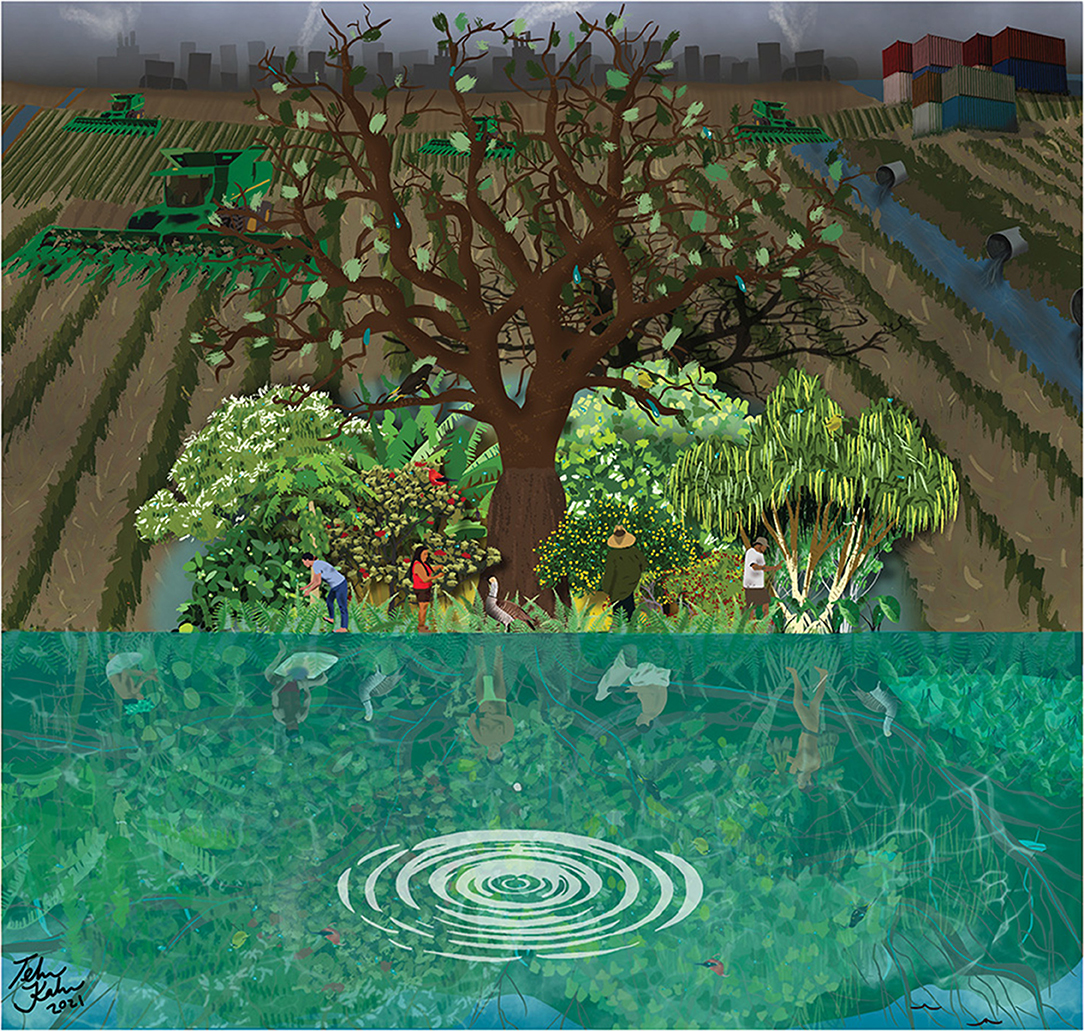

We interviewed agroforestry practitioners in Hawai‘i to understand motivations for, and obstacles to, agroforestry transitions and the factors that influence who is able to participate in these transitions. We found that most transitions occurred when practitioners gained new access to land, due in part to the historical context of land dispossession and accumulation by non-Hawaiians and colonialism. Most practitioners we interviewed chose agroforestry intentionally for non-economic, values-based reasons, with direct or practical benefits as secondary reasons. Practitioners' values and resulting practices, based in relationships and reciprocity, conflict with dominant institutions' values, which prioritize short-term production and economic profit. These contested values and an imbalance in power between practitioners and landowners, government agencies, policymakers, and other institutions cause agroforestry practitioners to fall through the cracks. To participate in agroforestry transitions, practitioners rely on resources external to their site, especially financial and social capital that are inequitably distributed, and a strong commitment to their values. Figure 3 illustrates these major findings and emphasizes the social and ecological potential of removing constraints to agroforestry regeneration.

Figure 3. Practitioners' values and resulting agroforestry practices, based in relationships and reciprocity, conflict with dominant institutions and systems of resource access in Hawai‘i that value short-term production and economic profit. These contested values and an imbalance in power between practitioners and landowners, government agencies, policymakers, and other institutions cause agroforestry practitioners to fall through the cracks. This illustration depicts how the conflict of values and power is like a tree whose top has been cut off and a new top grafted on, but the two trees (value systems) are incompatible, so the grafted tree struggles to survive and never produces fruit. Many Indigenous and local practices of agroforestry (area below the graft wound) are rooted in ancestral knowledge (roots and reflection below ground) and are impeded by the values of the dominant regime (grafted top). Some Indigenous and local practitioners are able to circumvent obstacles (push past the graft wound), yet structural change is needed to create more equitable access to participation and enable more just agroforestry transitions. Artwork by Tehina Kahikina.

Our case study highlights three interrelated key points with important implications for realizing just agroforestry transitions: (1) practitioners transition to agroforestry to restore ecosystems and reclaim sovereignty, not just for the direct benefits; (2) a major constraint to agroforestry transitions is that the term agroforestry is both unifying and exclusionary; (3) structural change is needed for agroforestry transitions to be just.

Practitioners Transition to Agroforestry to Restore Ecosystems and Reclaim Sovereignty

Our results highlight how practitioners' are motivated to transition to agroforestry by their values, not just the direct or practical benefits of agroforestry. In this way, for many of the practitioners we spoke with, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, transitioning to agroforestry was a political act through which practitioners sought to reverse social and ecological damage. Practitioners chose agroforestry purposefully as a form of ecological or biocultural restoration (Kimmerer, 2011). The values many practitioners held aligned with new agrarianism articulated in other diversified agriculture transitions (Mostafanezhad and Suryanata, 2018). Importantly, our case study also highlights a population of agroforestry practitioners motivated to reclaim Indigenous agroecosystems and food and cultural sovereignty, an aspect of agroforestry transitions that is often overlooked in the adoption literature (although see Dove, 1990). This points to the need for agroforestry research to more explicitly examine how social movements engage with agroforestry transitions, which is more common in agroecology research (Gliessman, 2016). Our findings thus reaffirm the importance of applying political ecology (Robbins et al., 2015; Robbins, 2019) and political agroecology (Molina, 2013) approaches to the study of agroforestry transitions. Given that our initial list of agroforestry practitioners included a significant number of Kānaka ‘Ōiwi organizations and practitioners, this might have translated to a higher representation of these groups as study participants than the population of agroforestry practitioners as a whole in Hawai‘i. Yet, this should not downplay the importance of their voices. Instead, our findings highlight the need to revise how agroforestry is framed in outreach, policy, and programs to be more inclusive of people trying to restore and adapt historical Indigenous agroforestry systems, rather than simply transition to agroforestry as a means to acheive production and economic benefits. Combining power sensitive and feminist approaches could further illuminate how not only capitalism and colonialism, but also heteropatriarchy affect these transitions (Espinal et al., 2021). Future research could explore the extent to which the Pacific Islander diaspora in Hawai‘i engages in Indigenous agroforestry practices and what obstacles to participation they face. Future studies could also investigate what other actors—land owners, existing farmers and land managers who do not practice agroforestry, and other people interested in transitioning—perceive as drivers and or constraints to agroforestry transitions.

The Term Agroforestry Is Both Unifying and Exclusionary

The unique motivators that emerged from our interviews create obstacles that do not exist for other types of agriculture, and that are not widely recognized. Importantly, one overarching constraint is the contradiction arising from how the term agroforestry is framed and used. Institutions like philanthropic organizations and federal and state government agencies who have the power to set resilience agendas often frame agroforestry as a multi-benefit land use linking agriculture and forest conservation (Ollinaho and Kröger, 2021). Practitioners use this frame to align their initiatives with funder priorities, making “agroforestry” a gateway to accessing resources. However, as illustrated in our interviews, the cultural norms and policies of these same institutions are still largely siloed and favor short-term production and economic value, which constrain agroforestry practitioners. Agroforestry in principle belongs to all sectors, but in practice, it belongs to none (Buttoud, 2013). This contradiction challenges inclusive participation in agroforestry. Further, many interviewees viewed the term agroforestry as a form of cultural appropriation, which can add to its exclusivity. To move beyond this contradiction requires de-siloing institutions and allowing for plurality in framing. One way to start is to increase communication, cooperation, and coordination between agriculture, forestry, conservation, and cultural organizations that support land stewards. Acknowledging and using culturally appropriate names for agroforestry locally is another incremental step. Future research could examine existing agriculture and forestry policies at local, state, and national levels and consider how their framing may drive or constrain inclusive agroforestry transitions and what changes are needed.

Structural Change Is Needed for Agroforestry Transitions to Be Just

This case study illuminated that without the means to self-fund, practitioners' ability to start practicing agroforestry and persist through the transition process is tenuous. The continuous struggle over values and imbalance in power between practitioners and institutions constrains the ability for agroforestry transitions to be just. We emphasize that structural change is needed to address these issues. Some changes may support all diversified agriculture since agroforestry practitioners share many obstacles with other producers. Yet, some solutions are unique because agroforestry practitioners' motivations and practices are different. Practitioners we interviewed emphasized the need to create more relationships, partnerships, and collaborations to increase inclusive participation in agroforestry. This reinforces other findings that transformations require not just changes in land use practices, or the adoption of technological practices, but the re-thinking of social relations and structures (Galt, 2013). And, while the practitioners we spoke with are working locally to transform the dominant agricultural system, additional support from institutions is needed to ensure local level domains of transformation can affect broader regime change (Anderson et al., 2019).

Restore Long-Term Land Access That Empowers Indigenous Practitioners

Our results highlighted that secure, long-term land access is a major constraint to agroforestry. Therefore, solutions are needed to increase the duration of leases and other access agreements, increase Indigenous practitioners' access to these tenure arrangements, and empower practitioners with decision-making autonomy. Opening up land access, especially under longer tenure agreements, needs to focus on restoring Kānaka ‘Ōiwi access to ensure just outcomes. As one practitioner questioned, “if we open up trust lands to everybody, what protects Kānaka ‘Ōiwi interest?” and expressed his concern directly, “we keep losing as Hawaiians and other people keep benefiting.” Future research needs to examine how potential interventions to improve land access for agroforestry practitioners will affect Kānaka ‘Ōiwi. We found that in Hawai‘i, private and public policies meant to protect landowners from risk and/or agricultural land from mismanagement, such as short-term leases and policies against living on agricultural land, put a higher burden of risk on tenants, especially those practicing agroforestry. Although the leases of many practitioners are bolstered by public discourse around the value of farming (Mostafanezhad and Suryanata, 2018), short-term leases still place a significant burden on practitioners to continually prove their worth relative to other land uses, like development. Tenants hold little power to negotiate lease arrangements, and therefore participation in stewardship practices like agroforestry is constrained.

Re-value Indigenous and Local Knowledge

Our findings also underscore how the lack of value placed on Indigenous and local knowledge is a major constraint to agroforestry transitions. Therefore, one strategy to enable more equitable agroforestry transitions is to re-honor the role of farmers as not only feeders, but also land and water protectors and public health stewards. Colonialism, and the low value placed on labor in plantations, de-valued the important role that mahi‘ai (farmers) played in the Hawaiian Kingdom and have contributed to an enduring process of erasure (Peralto, 2013). Interviewees described how this legacy and the physical struggles of farm labor feed the stigma that farming is a less desirable job than higher paying, less physically strenuous jobs, which constrains the re-generation of agroforestry today. As such, (re)honoring farmer livelihoods, lifestyles, and knowledge is critical to restoring Indigenous crops (Kagawa-Viviani et al., 2018), the foundation of many agroforestry systems. In turn, developing metrics for the contributions agroforestry practitioners make to their communities and society is another way to re-value their role. Future research could include co-developing biocultural indicators (Dacks et al., 2019) with agroforestry practitioners to honor place-based metrics of success. Although bringing attention to the societal benefits is important, it is critical not to downplay the cost of producing these benefits, so as not to undervalue farm work, which can normalize self-exploitation and lead to burnout (Suryanata et al., 2021).

Rebuild Resilient Support Infrastructure for Agroforestry Practitioners

Our results highlighted the importance of developing stronger infrastructure to support practitioners so that they can focus on stewardship. This reinforces other findings that increasing resilience of agricultural production systems requires supporting farmers as individuals so that they can grow food (Rissing et al., 2021). For example, practitioners we spoke with pointed to the need to better align investment capital with agroforestry initiatives. Additionally, practitioners expressed the need for support to get their products into markets including processing and distribution infrastructure, as well as buyers and consumer demand. This is a common constraint with agroforestry in other contexts because agroforestry products often lack existing markets and one practitioner may produce multiple products with lower volumes of each (Amare and Darr, 2020; Sollen-Norrlin et al., 2020). Additionally, there is a need to value not only capitalist markets, but also other modes of alternative market and non-market forms of exchange. Creating standards for agroforestry products may assist with marketing (Elevitch et al., 2018), although more research on the power dynamics and who benefits from these initiatives is needed to ensure equitable outcomes (Anderson et al., 2019). Structured demand or mediated markets are also a possible alternative (Guerra et al., 2017; Valencia et al., 2019).

Finally, our results emphasized the need to support practitioners in accessing place-based information and learning from each other, rather than knowledge deficit interventions that overlook structural barriers (Calo, 2018). Creating practitioner networks, particularly for Indigenous practitioners would be a key first step. In Hawai‘i, similar networks already exist for limu (seaweed) gatherers (The Limu Hui), loko i‘a (fishpond) practitioners (Hu‘i Mālama Loko I‘a), and taro growers on Kaua‘i (Wai‘oli Taro Hui), providing possible templates for agroforestry practitioners. Additionally, compiling place-based land use history into readily accessible formats for practitioners, following a historical restoration approach (Kurashima et al., 2017), could lower the burden to transitioning. Finally, increasing funding for research on place-based diversified farming systems could increase structural support for agroforestry transitions (Carlisle and Miles, 2013) and disrupt the lock-in of economic and policy forces that incentivize low diversity cropping systems (Mortensen and Smith, 2020). Future research could analyze social networks to identify further leverage points for change.

Conclusion

Agroforestry is widely promoted as a resilient land use. Yet, contested values and unequal power dynamics between practitioners and dominant institutions constrain just transitions to agroforestry. Our case study illuminates three interrelated key points that have important implications for realizing resilient and just agroforestry transitions. First, we find that agroforestry is intentionally chosen as a form of restoration and reclamation of sovereignty, not only as a means to production and economic benefits. Second, agroforestry faces an important contradiction: the same institutions that promote agroforestry also perpetuate the dominant systems of resource access, values, and silos that constrain agroforestry practitioners. Third, structural change is needed to enable just and lasting participation in agroforestry transitions. This work reinforces the need to consider the politics and power dynamics in agroforestry transitions and points to numerous future directions for participatory, action-oriented research.

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated for this study will not be made publicly available in their entirety to protect the privacy of interview participants. Inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ZH, MW, and TT contributed to conception and design of the study. ZH and MW conducted interviews, focus group, and transcriptions. ZH performed the initial coding, and MW and TT revised. MW and ZH collaborated with the artist to develop Figure 3. ZH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

ZH was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (#1842402). This work was also supported by a Phipps Botany in Action Fellowship and a grant/cooperative agreement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Project R/HE-38, which is sponsored by the University of Hawaii Sea Grant College Program, SOEST, under Institutional Grant No. NA18OAR4170076 from NOAA Office of Sea Grant, Department of Commerce (UNIHISEAGRANT-JC-20-04).

Author Disclaimer

The views in this paper are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding organizations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the practitioners who entrusted us with their knowledge and without whom this study would not have been possible. We are grateful to Tehina Kahikina for collaborating on the artwork for Figure 3. We also thank one practitioner for sharing the grafted tree metaphor that helped inspire Figure 3. We are also grateful to Krisna Suryanata for contributing to study development and for valuable suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript. We also thank Leah Bremer for feedback during study development and on an earlier draft.

References