- 1The Netherlands Land Academy, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Oxfam Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi

- 3LIVANINGO Mozambique, Maputo, Mozambique

- 4ENDA Pronat, Dakar, Senegal

- 5Groots Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya

Despite their key role in agriculture, in many African regions, women do not have equal access to or control and ownership over land and natural resources as men. As a consequence, international organizations, national governments and non-governmental organizations have joined forces to develop progressive policies and legal frameworks to secure equal land rights for women and men at individual and collective levels in customary tenure systems. However, women and men at the local level may not be aware of women's rights to land, and social and cultural relations may prevent women from claiming their rights. In this context, there are many initiatives and programs that aim to empower women in securing their rights. But still very little is known about the existing strategies and practices women employ to secure their equal rights and control over land and other natural resources. In particular, the lived experiences of women themselves are somewhat overlooked in current debates about women's land rights. Therefore, the foundation of this paper lies in research and action at the local level. It builds on empirical material collected with community members, through a women's land rights action research program in Kenya, Senegal, Malawi, and Mozambique. This paper takes the local level as its starting point of analysis to explore how the activities of women (as well as men and other community members) and grassroots organizations can contribute to increased knowledge and concrete actions to secure women's land rights in customary tenure systems in sub-Saharan Africa. It shows three important categories of activities in the vernacularization process of women's land rights: (1) translating women's land rights from and to local contexts, (2) realizing women's land rights on the ground, and (3) keeping track of progress of securing women's land rights. With concrete activities in these three domains, we show that, in collaboration with grassroots organizations (ranging from grassroots movements to civil society organizations and their international partner organizations), rural women have managed to strengthen their case, to advocate for their own priorities and preferences during land-use planning, and demand accountability in resource sharing. In addition, we show the mediating role of grassroots organizations in the action arena of women's secure rights to land and other natural resources.

Introduction

Women in the global South face severe challenges in claiming access to and control over land. Less than 15% of landholders in the world are women (FAO, 2018b). Women generally own less land and are less likely than men to have a title deed in their name. Even if a country has a gender-equitable legal framework, proper implementation of these laws is often lacking and enforcement institutions are weak. Gender-equitable legal frameworks have not resulted in desirable/expected gendered outcomes. In addition, a (joint) land title does not guarantee equal control over land for men and women (Doss et al., 2013, 2018). As a consequence, the importance of asserting women's power and control over land has been increasingly recognized. Over the past decades, numerous policies, projects and programs have been developed to ensure equal access to and control and ownership over land (and other natural resources) for women and men in sub-Saharan Africa. Through the Sustainable Development Goals SDG 1 (end poverty in all its forms everywhere) and SDG 5 (achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls) and SDG indicators 1.4.2 (relating to secure tenure rights to land) and Target 5.1 (end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere), women's land rights are being tracked in practices and legal frameworks across the world (FAO, 2018a). All 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have non-discrimination principles in their constitutions (Hallward-Driemeier et al., 2013). But despite these international and national efforts to contribute to more equal land rights and tenure security for women, along with many other gender inequalities, many women in sub-Saharan Africa still lack the opportunity to register land in their name. These gender frictions are most evident in customary systems, or more precisely, lands held collectively by communities (Alden Wily, 2011).

Collective and traditional tenure arrangements across sub-Saharan Africa were considered state land and not recognized by (colonial) law during most of the twentieth century. In line with capitalist and (neo)liberal thinking that focus on individual rights and autonomy, for a long time, donors, and governments have argued that collective lands should be privatized (Cotula, 2020). However, collective and traditional tenure arrangements are increasingly recognized in statutory law in sub-Sahara Africa to safeguard communities' access to land in the long term by limiting the possibilities for individual community members to sell their land to (foreign) investors or the government. In a review of countries that recognize collective land tenure systems, Alden Wily (2018) shows that 18 out of 21 countries under review recognized them within statutory law. Described as the “new approach towards customary tenure” (Fitzpatrick, 2005, p. 450), it is considered a positive trend that offers individuals within a group increased tenure security within locally adapted governance systems. At the same time, Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2020) argue that collective tenure systems often impose barriers to women's rights and access to land, because women's use and control over these lands depend entirely on their position within the collective that is often managed by men. However, we know very little about the conditions under which collective tenure arrangements present an opportunity for women's secure access to and control and ownership over land, or what is being done to secure women's land rights in these systems. The underlying mechanisms, structures, and processes that place women in a vulnerable position to access, control, and own the land that they rely on for their livelihoods is not yet fully elaborated.

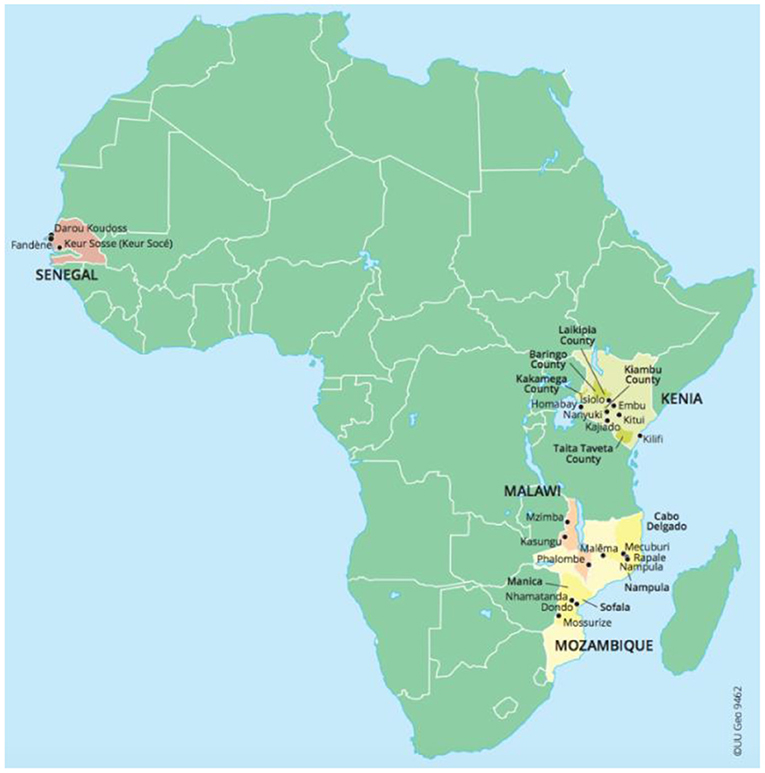

This paper will address this knowledge gap by focusing on research and actions on women's land rights in customary systems at the local level. With women's land rights (WLR), we refer to secure and equal access to and ownership and control over land for women and men, going beyond merely legal rights or titles. Through a women's land rights action-research program (2017–2018) we intensively collaborated with community members (women and men), a number of grassroots organizations (ranging from grassroots movements such as Groots Kenya to civil society organizations such as Fórum Mulher and ADECRU in Mozambique and ENDA Pronat in Senegal, and international federations such as Oxfam Malawi and ActionAid Kenya) and the Netherlands Land Academy (LANDac) to better understand women's land rights in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Senegal (see Figure 1). The program began at the very local level to explore how the activities of women (as well as men and other community members) and grassroots organizations can contribute to increased knowledge and concrete action to secure women's land rights in customary tenure systems in sub-Saharan Africa.

We build our empirical analysis on the notion of vernacularization (Merry and Levitt, 2017) to show that NGOs and civil society organizations (CSOs) play a crucial (but so far often invisible) role in translating nationally and internationally defined agendas on women's land rights into local contexts—and vice versa: by putting local realities into national and international agendas. These local organizations play a crucial role in the literal translation of the law in an understandable language and terminology that can be fully understood and correctly interpreted at the local levels of society. But they are also addressing the more symbolic dimensions of the complex translation processes. They are reframing the law and people's day-to-day experiences—and women's land issues in particular—in terms relevant to and compatible with the specific cultural and social settings people are living in. In-depth knowledge of processes taking place at the local level is not only relevant to realizing progress on the ground, but also to acknowledging and supporting local organizations' mediating role in the action arena of women's land rights.

In the following part, we provide a theoretical framework that includes the relevant academic debates on women's land rights in customary and communal systems. In the empirical parts, we start with an outline of relevant context, including the legal frameworks in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Senegal. We then reflect on the action arena of women's land rights, the set-up of the action-research project and the methods and tools used. Thereafter, we elaborate on the vernacularization process of women's land rights in these four countries. We focus on three categories of activities key to successful vernacularization processes: (1) translating women's land rights from and to local contexts, (2) realizing women's land rights on the ground, and (3) keeping track of the progress of securing women's land rights.

Women's Land Rights in Africa: An Analytical Background

Women's contributions in agriculture are key to food security in the global South. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggests that women comprise about 43% of the agricultural labor force globally (FAO, 2016). These percentages are probably higher in the global South, where much of the contribution and engagement of women in agriculture and food security remains veiled in the informal sector. In the 70s and 80s, a growing number of scholars advocated for an explicit recognition of women's roles in agriculture. In her book “Women's role in economic development,” Boserup (1970) argues for a fair valuation of the role of women in agriculture and demonstrates that within the household, women and men do not benefit equally from economic growth. Academic work that followed has made rural women's socio-economic inequalities across the global South more visible by showing that women's contributions to family food production is undervalued compared to men's production of cash crops and other economic activities (Bryson, 1981; Dixon, 1982; Boserup, 1985; Jiggins, 1989). Women take up key responsibilities within the household, bearing, and caring for children, and caring for the elderly and the vulnerable within their communities. Most women experience an extra workload in addition to their role in agriculture and their substantial contribution to the household budget (through food production but also in food preparation, provision, and marketing). However, women often remain invisible in rural policymaking and the formulation of development projects, which generally target men. Some of the earliest mentions of the need to include women in strategies to increase agricultural production were made by Safilios-Rothschild (1985) and Gladwin and McMillan (1989). In the years that followed, women's persistence in agriculture received growing attention, as further exemplified by the United Nations Decade for Women (1975–1985). Among others, this laid the foundation for decades of academic and societal debates on women's equal access to and control over land and other natural resources.

As one of the pioneers working on women's land rights in the global South, Agarwal (1988) analyzes obstacles to more equal rights for women and men in India. She argues that progressive legal frameworks did not yet contribute to more equal access to land as many cultural obstructions and biases withheld women from claiming their legal rights. In her book “A field of one's own: gender and land rights in South Asia” (Agarwal and Bina, 1994), Agarwal explains that women are generally responsible for the household well-being. She argues that the recognition of women's land rights (without depending on a male relative) ensures more equal distribution of benefits within the household compared to exclusively male rights to land. She shows that land under women's control is used more efficiently and (potentially) more environmentally soundly. In addition, Agarwal argues that equal control and rights over productive resources, including land, are part of a just society and a way to empower women and reach gender equality. In the years that followed, more and more scholars recognized gender-discriminatory practices in land ownership and indicated how it results in inefficient production processes and decreased opportunities for improved well-being and sustainable development (Fonjong et al., 2013; Archambault and Zoomers, 2015a; Ajala, 2017). Although strong evidence is still lacking, most scholars on women's land rights agree that secure land rights for women contribute to a household's increased food security (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). In a systematic review of available evidence, Meinzen-Dick et al. (2019) conclude that land titles for women significantly contribute to increased bargaining decision-making power on consumption behavior, human capital investment, and intergenerational transfers (Doss et al., 2018; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2019). However, despite the global consensus on the negative consequences of gender inequities in land ownership and control, implementation, and enforcement of women's rights and access to land is lagging behind. An important reason for this, as several academics have argued, is the lack of gender disaggregated and comparable data, building on a common understanding of women's tenure security among researchers and practitioners, that hinders a complete picture to define, understand, and analyze women's tenure security (Doss et al., 2013; Archambault and Zoomers, 2015b; Doss and Meinzen-Dick, 2020).

In line with the definition of the FAO (2002), women's land tenure security can be defined as “the degree of confidence that land users [women] will not be arbitrarily deprived of the bundle of rights they have over particular lands and that these rights will be respected and recognized by legal and social institutions” (Doss and Meinzen-Dick, 2020, p. 3). Building on this definition, Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2020) developed a conceptual framework that helps to reveal the social-economic, biophysical and institutional contexts that shape the threats and opportunities to women's land tenure security. There are two main elements of Doss and Meinzen-Dick's conceptual framework that influence each other and ultimately, the outcome of women's land tenure security: the context (in particular, social laws, and norms) and the action arena. They are important to better understand the processes at play at the local level in customary land systems, which is the focus of this paper. First, by stressing the role of context, Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2020) point to the complex interplay between different legal systems and the coexistence of both statutory and customary laws in a country, often described as legal pluralism. For decades, women's land rights discrimination has been attributed to customary systems as most statutory systems allow equal access to land for women and men in which both can acquire land titles (Haugerud, 1989; Atwood, 1990; Bruce and Migot-Adholla, 1994). But as argued by (Archambault and Zoomers 2015b, p. 4) “there is often considerable ambiguity as to which tenure regime would be best for improving women's well-being.” They state that “this is not only because women do not constitute a uniform social group but also because each tenure regime is complex and carries its own advantages and disadvantages” (Archambault and Zoomers, 2015b, p. 4). As argued above, mere land titles do not guarantee more equal power and control over land for women. Furthermore, customary and statutory law may overlap and contradict each other and may be differently applied in different situations and contexts. Following this line of reasoning, Whitehead and Tsikata (2003) argue that customary law should not be considered as a different sort of legal system, but instead as socially embedded practices at the local level. Translating formal legal measures to local contexts is challenging and can negatively affect these socially embedded practices on a local level. Traditionally, within customary systems, women have made diverse and strong claims to land. But over time, colonialism and imposed liberal economic systems, increased scarcity of land and economic transformations have resulted in gender discrimination, especially when it comes to land ownership (Whitehead and Tsikata, 2003; Alden Wily, 2011). For example, efforts of land titling might reduce women's access to land by encouraging single-registered ownership (Mackenzie, 1993). At the same time, privatization processes may negatively affect women who often lack the resources to buy land or access credit. Therefore, statutory and traditional and customary law should not be considered as parallel legal systems, but the latter as sets of socially embedded practices at the local level (Whitehead and Tsikata, 2003; Cooper, 2011; Peters, 2013). Second, Doss and Meinzen-Dick's conceptual framework (Doss and Meinzen-Dick, 2020) encourages researchers to pay particular attention to the action arena of women's land tenure security, including the relevant actors and their resources available to influence change. As such, it offers a useful framework to start further analyses on women's land rights from the perspective of actors at the local level and the concrete actions and resources they employ on the ground to guarantee women's tenure security and well-being. This paper contributes in-depth knowledge and experiences of this action arena from the perspective of grassroots organizations and their members.

A third concept useful for our analysis of actors and their actions and resources within this action arena, with a particular focus on NGOs, is Engle Merry's concept of “vernacularization” (Merry, 2006). The author defines the concept as “the extraction of ideas and practices from the universal sphere of international organizations and their translation into ideas and practices that resonate with the values and ways of doing things in local contexts” (Merry and Levitt, 2017, p. 213). She shows how women's NGOs interpret globally defined human rights, make them understandable and apply them to their local context. In addition, through this process, NGOs, and other local actors also contribute to the creation of social movements and the translation of issues that exist on the ground into international human rights issues. While we acknowledge NGOs are a diverse group with divergent goals and interests, and therefore prefer the term “grassroots organizations,” to emphasize the crucial role they play as intermediaries between different policy levels and local realities. The concept of vernacularization also allows us to recognize that women's land rights experiences and perspectives are divergent. Like the grassroots organizations, women whose rights to land are discussed are not a homogenous group, but are comprised of a wide range of women with diverse socio-economic backgrounds, statuses, interests, and priorities (Chigbu et al., 2019).

In the next sections we will focus on describing the context and action arena in which women, grassroots organizations aim to secure women's land rights. We will identify actors and interactions and analyze how the vernacularization of women's land rights takes place through the daily activities of women's grassroots organizations, using examples from Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Senegal.

Context: Progressive Legislative Frameworks for African Women

Over the past decades, positive changes in international spheres and national constitutions and legislation have been made. At the global level, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action1 framework has become an important example of one of the most progressive global frameworks for change on women's rights in general and women's land rights in particular, going far beyond the focus on regularization and formalization of land rights alone. Currently within the Beijing +25 review, governments and non-governmental actors have agreed on immediate actions to increase women's access to and control over productive resources and to build the resilience of women and girls to climate impacts, disaster risks and loss and damage, including through land rights and tenure security by 20252. While the frameworks of these global multi-stakeholder platforms are not binding, and some member states have even openly resisted on them, they have offered a very powerful platform for mobilizing political will of many individual African governments through accelerated financing, transforming gender norms (also by engaging men and boys), gender data and accountability, addressing intersectional discrimination and focusing on systemic change by addressing structural inequalities. In addition, institutional commitments from the African Union and the African Land Policy Centre (ALPC) aiming to provide a policy response by “mov[ing] towards allocation of 30% of land to women” have further reinforced aims of African countries to improve the rights of women to land through legislative and other mechanisms (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2016). Indeed, multiple African governments adopted progressive legal frameworks to ensure equitable land rights for women and men. In this section, we provide an overview of women's land rights, both in legal statutory frameworks and customary practices, in the four countries under study. We will pay particular attention to these contexts in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Senegal and how they are realized in practice.

Kenya

According to the Kenyan Constitution (Republic of Kenya, 2010, article 61) land in Kenya is classified in three categories: public land (e.g., government forests), community land (held by communities identified on the basis of ethnicity, culture, or similar communities of interest, including land registered in the name of group ranches, ancestral lands, or community forests) and private land (held by individuals under freehold tenure) (Alden Wily, 2018). Over the years, the Kenyan government has taken several steps to develop a constitution that reflects international standards of gender equality, and formulated laws to give effect to the constitutional provisions (Republic of Kenya, 2010). Article 27 in the Constitution of Kenya promotes gender equality and describes the equal rights for men and women to equal treatment and opportunities in political, economic, cultural and social spheres. In addition, the Community Land Act 2016 (Republic of Kenya, 2016) sets a new framework in which customary holdings are to be identified and registered. According to this act, each community may secure a single collective title over its lands and govern this property according to standardized gender equity rules. Following national laws, this act also requires equal membership and decision-making power for women and men living on community land. In order to make this happen, community, land regulations have been formulated and institutional mechanisms have been set up to support implementation of this act. As a consequence, there are several communities that have been issued with community land title deeds and the legal gender provisions in terms of membership and governance, but many more have yet to follow. However, there still exists a substantial gap between formal land laws and the reality on the ground, where cultural practices and patriarchal systems severely limit women's access to land and natural resources.

Malawi

Although far from equal, national statistics show that relatively more women own land in Malawi than in most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. After Malawi's independence in 1964, land is owned by the republic. Since the attainment of a multiparty democracy in 1993, Malawi has been involved in a long process to establish new institutional frameworks for the administration of customary land. The Malawi National Land Policy (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2002) aimed to ensure equal access to land for all Malawians. In 2016, this policy was further specified in 10 bills of legislation, which include the Customary Land Act. This act recognizes customary land in matrilineal or patrilineal societies, and states that it can be registered as such. The fact that community-owned customary land can be titled and registered should offer security against land grabs by local elites and foreign investors. When land is owned by a community, is it not easily sold to investors by its individual members. In addition, the law states that customary land committees shall be responsible for the management of all customary land in a Traditional Land Management Area. At least three out of six committee members should be women (Government of the Republic of Malawi, 2016)—building on the gender policy which requires a minimum of 40 women to 60 men in all governance structures.

The new land bills came into force in 2018. However, the operationalization and implementation of these land-related laws have been a gradual process largely driven by donors. It was piloted in three districts by a consortium of CSOs led by Oxfam in Malawi with financial support from the European Union and in six other districts with funding from the World Bank. However, where the pilot projects were implemented, women still had little opportunity to actively participate in decision-making, let alone participate in customary land registration and titling, especially in strong patrilineal societies (where inheritances are passed onto sons and the wife moves in with her husband's family). In a matrilineal system, where an inheritance is passed onto daughters and the husband moves in with his wife's family, it has been argued that women tend to have better access to land “because the family has a financial interest in investing in the daughter who will pass on the property to the next generation” (Peters, 2010 cited in Behrman, 2017, p. 330). However, while both systems exist in Malawi, men nonetheless remain decision-makers regarding access and control over land (Kathewera-Banda et al., 2011).

Mozambique

Mozambique has established a legal framework that should ensure equal rights for women and men related to land. The Land Law of 1997 (Government of Mozambique, 1997) states that all land belongs to the state and cannot be sold, alienated or mortgaged. Citizens' rights to access and use land are officially recognized by the possession of a DUAT (Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento da Terra or “right to use and exploit land”), that women and men can obtain. However, a DUAT does not register secure farmland and a large share of Mozambican land is not registered as a DUAT. The DUAT can be issued in three ways. First, communities can obtain a perpetual DUAT for land recognized under customary systems. As such, communities are the holder of a single state DUAT, which recognizes that the customary norms and practices also determine individual and family land rights within the community. Second, individuals occupying land in “good faith” for at least 10 years have a perpetual DUAT for residential and family use. In these two forms, communities, and individuals can prove land rights through testimony without registration or titling, i.e., they are not required to hold a formal DUAT title to prove their land rights (Cabral and Norfolk, 2016). Third, individuals can apply for a DUAT for up to 50 years (with one renewal) and a land rights concession, typically for natural resource extraction or developing agricultural, forestry, or fishing activities (Åkesson et al., 2009; Cabral and Norfolk, 2016). While community members can obtain a DUAT by occupying land for 10 years, individuals requiring land for non-housing or non-community purposes must apply for a DUAT title (Hilhorst and Porchet, 2012).

The DUATs lie at the heart of land governance in Mozambique. However, since DUATs only grant access rights, the government still holds considerable power over what happens with the land, leaving communities vulnerable to the will of the government and land-based investments from foreign companies and national elites.

The Land Law of 1997 officially recognizes women as co-title holders of community-held land and further states that all community members (and therefore also women) should participate in decision-making processes. But according to the National Directorate of Land, in 2015, only 20% of DUATs were registered to women and 80% were registered to men (Adriano and Machaze, 2016). Women usually obtain their rights through customary norms and practices that do not follow national laws. Within most customary systems, women's rights are defined through their relationship to men: women gain access to land through their husbands, fathers, uncles, or brothers. But other factors also play a role: women are increasingly vulnerable to losing their land because of land scarcity in the country (due to population growth and an increasing number of private large-scale land acquisitions). In addition, many widows (for instance, young widows who may have lost their husbands to HIV-AIDS) lose everything upon the death of a husband, even though the Land Law (in combination with the Family Law) dictates that widows should inherit at least half of the shared property (Bicchieri and Ayala, 2017).

Since 2020, the 1997 Land Law and other laws and regulations that govern land in the country are under serious revision. Ntauazi et al. (2020) see a clear shift toward a more market-oriented policy framework in these reviews. They argue that the reviews are oriented to make large-scale land acquisitions from national and international private companies easier and more attractive, without taking the needs and concerns of the local communities into consideration. Many CSOs are therefore concerned that the number of concessions will continue to rise, and the power of communities—and women in particular—will correspondingly diminish (Ntauazi et al., 2020).

Senegal

At the time of independence (1960), the Senegalese land tenure system included three overlapping legal systems: a customary system (stemming from traditional customs), the registration system and the French civil code system (as introduced by the colonial government). In 1964, the Senegalese government aimed to harmonize the three systems with Law 64–46, known as the law on the national domain. This land reform divided land into three categories: state land, private land and national land. State land (which in 1964 represented just 3% of Senegal's land) belongs to the state and is divided into public and private land (these private lands can be sold by the state). Private land (which represented only 2% of Senegal's land in 1964) is owned by individuals who hold a land title. This land can be the subject of land transactions (sale, rental, pledging, etc.) unlike land in the national domain. National land (otherwise known as “community land”) makes up the majority of land in Senegal today and is generally used for housing and for most socio-economic activities in rural areas (agriculture, pastoralism, etc.). As in Mozambique, occupants of community land do not have property rights, but user rights.

According to the statutory laws, community land is available to all, women and/or men, on condition that the applicant is a member of the community and has the capacity to develop the area of land requested (Republic of Senegal, 1996). In practice, the obligation to develop land imposed by law is a barrier for women, as they generally have much less access to the financial resources and agricultural inputs needed to meet this requirement. However, these statutory laws are rarely applied at the local level where land is still governed by customary practices. In customary systems, land is collectively owned by a family or village and managed by the head of the unit, basically a man, in consultation with an all-male community assembly. Women often do not have the right to speak when land issues are discussed and only have access to land through a father, husband or son. Women often lose this access if they are single, divorced, or widowed.

Context: Concluding Remarks

In all of the four countries under study we have seen that efforts to reform national land legislation have been underway since the 1990s. But to date, the formulation of these new land laws is still in progress. In fact, several grassroots organizations and other actors on the ground have expressed concerns that the proposed changes will further contribute to the privatization and commercialization of agricultural land and further marginalize women (CRAFS, 2016)3. Indeed, while statutory laws aim to provide gender-equal land governance systems, the situation on the ground shows an entirely different picture. All of the four countries under study show that, especially within customary tenure systems, women continue to face insecure tenure and unequal access to and control over land and other natural resources. Women are often excluded from participation in decision-making processes. Recent efforts that aim to increase women's participation in governance structures (such as those described in Kenya and Malawi) are important steps forward, but implementation is still slow.

In the next section of this paper, we explore the action arena of women's land rights and the ways that grassroots organizations—aiming to support women in claiming their rights at the community level—navigate the different effects and sometimes contradictory impacts of the progressive land rights and tenure systems in the different countries by first focusing on the set-up and the methodology of the Women's Land Rights in Africa (WLRA) program (2017–2018). Thereafter we focus in more depth on the vernacularization strategies of the different project partners.

The Action Arena: Program Set-Up and Methodology

Women's land rights are a global concern in which a plethora of different actors are involved. According to Doss and Meinzen-Dick (2020), the action arena of women's land tenure security includes a diversity of actors who can influence women's land rights and mobilize the resources to do so. In our Women's Land Rights in Africa (WLRA) program (2017–2018), which forms the basis of this paper, we started from the principles of action research to better understand women's land rights in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Senegal. Since its introduction by (Chambers 1994a,b,c), action research, and participatory research approaches more broadly, took on different forms and worked with different methods and approaches to enhance people's awareness and confidence. Although the pros and cons have been widely discussed in the literature (e.g., Leeuwis, 2000; Cooke and Kothari, 2001; Kapoor, 2002), this philosophy of learning from, with and by rural people by “handing over the stick” (Chambers, 1994b) has always been central in our WLRA program.

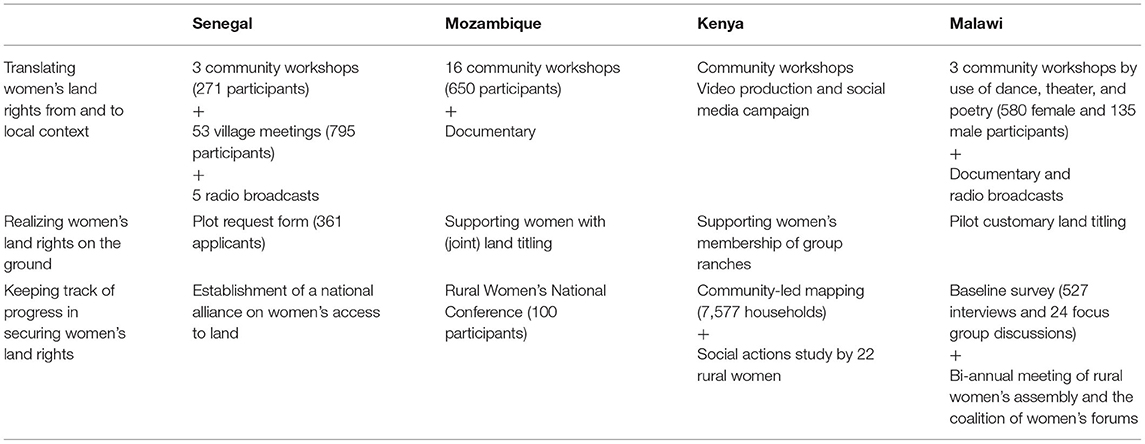

Throughout the program, we aimed to identify, build upon and scale-up successful practices and experiences toward strengthened land rights for women by systematically combining the work and ongoing activities of six grassroots organizations with 6 weeks of action research in the four countries. These grassroots organizations ranged from grassroots movements (Groots Kenya), CSOs (Fórum Mulher, ADECRU in Mozambique and ENDA Pronat in Senegal), and international federations (Oxfam Malawi and ActionAid Kenya). They were diverse in governance structures, funding sources, their approach and the kind of activities they organized (see Table 1). We call them grassroots organizations because they all had in common a long history of working at the local level with rural communities and movements to strengthen women's land rights. They were powerful intermediaries, playing an important role in defining activities and shaping action on the ground. At the same time, they were continuously balancing their interests with specific funding opportunities provided by national and international organizations. With the support of the WLRA program (financed by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs) their ongoing activities were scaled up with additional funding.

Table 1. Grassroots organizations' activities within the women's land rights action-research program.

During the WLRA program, we co-produced (see Ostrom, 1996; Mitlin, 2008) a locally embedded agenda on women's land rights with community members (women and men). A diverse group of local women set the agenda for the interviews and focus group discussions, framed their own stories as they wanted to and guided the researchers in transect walks to show the realities of their current land tenure situations. The women also interviewed other women about their land tenure situations using photos and videos, and, with support from the grassroots organizations and researchers, documented their stories and visions of how to scale up and strengthen women's land rights. Using these types of participatory methods, the agency and knowledge of local women, and other community members was acknowledged and valued. In addition, with a focus on collecting data not only about, but with and for women themselves, the research could minimize power imbalances between local organizations, researchers, and women.

Lastly, two LANDac researchers, with a background in anthropology and human geography, participated in the program activities to reflect upon women's stories and testimonies and to analyze the impacts of the organizations' activities. In other words, the methodological foundation of this program lies in research and actions at the local level. The research strongly builds on the interventions and activities of grassroots organizations, and the voices of women and their strategies to overcome the insecurities they face. Together with women and academic researchers, the organizations continuously provided the knowledge and input for the program. This was crucial to gain an in-depth understanding of the diversity of local contexts and needs, the variety of experiences of women and men, and the gendered differences between them.

The Vernacularization of Women's Land Rights

As emphasized in the theoretical framework of this paper, grassroots organizations play a crucial role in translating nationally and internationally defined agendas on women's land rights to local contexts—and vice versa: by putting local realities onto national and international agendas. This process of vernacularization is a bottom-up process that is shaped by women's initiatives and actions, supported by grassroots organizations' concrete activities. Although the literature on vernacularization narrowly focuses on the translation of global norms to local context, our action research project shows that translating women's land rights from and to local contexts is just one of many vernacularization processes of women's land rights. By grouping existing activities on the ground that aim to realize women's land rights on the ground, we describe two additional important ways of vernacularization that are addressed by community participation and the activities of grassroots organizations: realizing women's land rights on the ground and keeping track of progress on women's land rights. In this section, we will describe and analyze these three categories separately. However, in practice, these three processes do not exist in isolation: there is much overlap between them.

Translating Women's Land Rights From and to Local Contexts

The first set of activities include a variety of ways to translate the cause of women's land rights and statutory law from and to the particular local context where they are enacted. It also includes dissemination of lessons learnt from the ground to and within communities and other levels of governance (e.g., municipalities, national, and international governments). These activities focus on outreach through popular media, community workshops, and collaboration with local champions.

Media Outreach

To reach a large number of local community members, many organizations worked with popular media to equip local populations with evidence and strategies for advocacy. In Senegal, Enda Pronat organized five radio broadcasts in local languages at the level of the different municipalities. During the broadcasts, the presenter asked farmer leaders, leaders of women's and youth associations, and other land experts to inform their audience about the legal procedures governing the management of natural resources and the issues of women's access to land. The shows not only informed women and their communities about land rights, but more importantly, they helped to put the topic of women's land rights on the agenda of the communities and to initiate a discussion between women, men and community leaders about land issues that are often considered inappropriate or irrelevant. In Mozambique, ADECRU and Fórum Mulher published a flier on women's rights to land and natural resources to explain the importance of women's land rights to a broad public. This flier became an important tool to conduct trainings, workshops and advocacy dialogues with the government. ADECRU and Fórum Mulher also produced a short documentary4 on women's land rights. The documentary was used as a tool to illustrate the challenges rural women in Mozambique face to access and control land. But in addition, it also became an effective way of drawing attention to women's narratives and experiences and to give the participating women the feeling that their stories were worthwhile enough to be heard globally. By listening to other women voicing their stories, women were also encouraged and motivated to speak out in favor of their rights. Showing the documentary to policymakers and practitioners has stimulated the further implementation of policies that promote women's access to land and other natural resources. In Kenya, Groots Kenya has contracted HIVE, a platform of local social influencers and celebrities, to promote women's land rights in their existing public spaces. One of these influencers published a video produced by Groots Kenya, which was viewed by over 3 million people. In the days after this video, Groots Kenya was contacted by many women, often widows, asking for legal assistance.

Community Workshops

In all four countries, community workshops, and other activities were organized by the grassroots organizations and their members. These workshops were led by facilitators from farmers' associations and communities who were trained on land legislation and women's rights (e.g., in Senegal), or by employees from the ministry of land (e.g., in Kenya and Mozambique). In Malawi, different existing artistic groups were mobilized to perform dances, recitals and plays on women's land rights, using slogans that aimed to increase women's agency, such as “My Land, My Right” or “Stop Land Grabbing.”

These bottom-up processes provided an important space for dialogue and mutual learning between local organizations and communities. In Senegal, Enda Pronat brought together administrative authorities (sub-prefects, mayors, and local elected officials), customary and religious authorities, and land users (including women and youths) in three community workshops and 53 village meetings on the governance of natural resources, land tenure security, and women's access to land. During the sessions, it became clear that many of the participants in the workshop, including the village chiefs, were unaware of the statutory land laws. In addition, the workshops offered the opportunity to gather the views and suggestions of local community members and possible challenges to further influence the enactment of land legislation and land reforms in practice. During the workshops, women discussed their limited access to and control over land because they were often excluded from inheriting family lands and were not consulted when it concerned community land assets. These debates made it possible to engage community leaders such as mayors, village chiefs and religious leaders to support women's struggles for the respect of their rights at the local level. Although their support to advancing women's land rights is not a given, we found that when these (male) leaders are actively involved, the chances of successfully changing practices on the ground increase.

In a community workshop at the collectively held land in the group ranch of Laikipia in Kenya, a discussion between representatives from the national Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning and the Laikipia group ranch members made clear that land issues related to divorce and widowhood in community land tenure systems were not effectively addressed in the Community Land Act 2016. For example, divorced women explained how they were removed from the community land registers where they were born as soon as they were married, but were unable to rejoin these land registries once they got divorced. Similarly, widows were removed from their husband's community land registers after their husbands died, but then could not reclaim access to the land registers of the communities where they were born. Based on this discussion, the ministry representatives discovered that the Community Land Act was still underdeveloped. They drove back to Nairobi with the insight that some further amendments were still required to protect women in these types of situations.

In Malawi, we encountered conflicts in the practical implementation of inheritance laws. In communities with a patrilineal marriage system, a woman moves to her husband's home when she gets married and land is inherited from father to son. In many localities, a woman is not permitted to register land in the community of her husband. Similarly, in the strong matrilineal oriented south in Phalombe District, a husband moves into his wife's community after marriage and land is inherited through the women's lineage. During a workshop, a discussion among participants evolved around the question of whether a man in the strongly matrilineal culture would be able to register land in his wife's community. Similar discussions occurred concerning the widow's ability to register land when the husband or wife dies—in most cases, a widow loses her land when it is not jointly registered. The Malawian case shows that as long as land is not jointly registered, the new land law risks being counterproductive to the protection of women's land rights.

Community workshops also proved to be an important strategy to reveal misconceptions of statutory law. Oxfam in Malawi, for instance, initiated the organization of women's land rights forums: bi-annual platforms to discuss issues of women's land rights, leadership, and empowerment. Public sensitization meetings (involving 715 participants) also brought women's land right to the attention of local authorities and clarified some misconceptions about the content of statutory law held by traditional authorities. For instance, chiefs were worried that the new law would bypass their authority over community land. However, the new law only brought in more transparency and accountability on land transactions and ensured women's participation in decision-making processes. In this sense, workshops were found to be important in dealing with misconceptions about the law.

The 16 community workshops in Mozambique further illustrated the power of dialogue and processes of mutual learning and the way they inspired action. In these workshops, community members, both women and men, were organized in small groups to discuss concrete women's demands and priorities in terms of land, water, and other natural resources. After the workshops, increased knowledge about land and family laws and the possibility of sharing experiences with other women fostered a diverse group of local women's involvement in agenda setting and in concrete actions on the ground. For example, a month after a community workshop in Nacala, a group of women organized themselves to confront Green Resources (a Norwegian company that acquires community land for eucalyptus plantations) and demand their land rights. A movement defending women's land rights was established as a direct result of this process. This movement consists of community-based groups, including local and traditional leaders, that also aims to provoke dialogue at the local community level on women's land rights. These dialogues have helped to eliminate existing biases associated with cultural and community traditions. This group will also serve as a bridge between government and community during further dialogues, as will be explained below.

Local Champions

Women and men who actively advocate for women's land rights within their communities play a key role in translating women's land rights to local contexts beyond the organized space of community workshops. In all four countries, the grassroots organizations worked with what they called “local champions”: women who have successfully secured their rights and subsequently strongly advocate for the rights of others. They perform a key function in acting as role models and mobilizing the community to advocate for women's land rights. The authenticity of local champions as being full part of their own community (“one of our own”), makes it very easy for these women to play the role of ambassador for their communities. They are considered to be able to translate and disseminate land rights messages across different countries and communities and act as a localized source of accessible knowledge for their community.

During our action research, we observed that local champions are important change agents, knowledge brokers, and development intermediaries in the communities where they reside (see also ActionAid Kenya et al., 2018). By training local champions, often already key figures in their communities, grassroots organizations have ensured that awareness-raising activities about women's land rights and land governance can take place at the local level. The following passage illustrates the way local champions have addressed women's land rights in one of the workshops organized by Oxfam in Malawi:

I would like to thank you all for allowing me to address you. I'm here to inform you that there will be a land registration exercise shortly. The registration will involve everyone, men, women and the children. Especially you women, you have to participate in the exercise so that you will have ownership of your land […]. Please ensure to attend the meetings called by the chiefs regarding customary land registration and titling. Because there will be a need for women to participate in the elections so that they can be members of customary land committees. Myself, I've already started a campaign so that when it's time for elections, I can be voted as a member of the customary land committee. And if I will be elected a member, I will ensure that the chief doesn't take bribes or intimidate the women. So, women are free and have the power to hold any positions. That is all, thanks.

Eva, Mzuzu training, 8th February 20185

In Senegal, local leaders and, in particular, religious leaders played a key role as local champions. For instance, the mayor of Tattaguine actively advocated for women's land rights by ensuring that all costs associated with registering land titles for women were covered by the community. This directly resulted in more property registrations for women within that community. Also, other mayors and locally elected officials have publicly supported the women's struggle and taken action to alleviate the costs of registration for women. The village chiefs also convened village meetings during which they took the floor to support the cause of women and demanded that more families and households respected women's rights. The same attitude has been observed at the level of religious leaders (imams), who, in their sermons, spoke of women's rights in the context of Islamic law.

Participating organizations also literally translated the cause of women's land rights and the associated statutory laws into local languages and dialects. They did so by reaching out to popular media and engaging communities through workshops and local champions. NGOs working at the local level provided a space for local stakeholders, including the NGOs and other local organizations, local women and men, and (traditional) authorities to learn about and interact on the subject of women's land rights. These spaces allowed for the identification of challenges to and misconceptions of women's land rights and land reforms, some of which may be resolved at the time, while others are fed back into (national and international) policy spaces. These cases exemplify the idea that the vernacularization of women's land rights is a two-dimensional process. On the one hand, it gives local communities the opportunity to better understand and adapt the top-down developed national land laws. On the other, it shows that this process of translation also works from a bottom-up perspective in which local actors play a role in shaping, fine-tuning and articulating the national land laws according to their specific realities on the ground.

Realizing Women's Land Rights on the Ground

Grassroots organizations play important formal and informal roles in ensuring the enactment of, for example, land titling projects in Senegal and Mozambique and the formation of customary land committees in Malawi. We encountered three strategies employed by grassroots organization in realizing women's land rights on the ground, including supporting women with land titles in their name (as an individual or a collective) and supporting women in claiming decision-making power over community land. In the following sections, we elaborate on these three strategies and their outcomes.

Supporting Individual Land Titles

In recent years, registration programs have become an important step toward implementing new legislative frameworks at the local level. Several CSOs in Asia and Latin America have played a key role in assisting community members with the legal administration of their lands in order to protect them from external shock and insecurities, and assuming that this will contribute to increased tenure security (e.g., Busscher et al., 2019; Lorayna and Caelian, 2020). In our program, Enda Pronat encouraged women in Senegal to acquire land titles as individuals. They helped women (and men) to fill in an application form (“fiche de demande de parcelle”) to obtain legal documents that confirm the usufructs of the lands that they have a right to under customary law. Enda Pronat developed simplified forms for community members, and for women in particular, who wanted to legalize their customary land tenure. Completed application forms were collected and verified by the local leaders and legal experts before they were handed over to the municipal council. Some municipalities endorsed these submissions by validating the form and giving the applicants an individual title. However, many municipalities feared resistance from their communities and did not endorse the submitted forms. At the same time, in many cases, the families themselves refused to share a part of the land with the applicants as the land in question was considered family land, not to be given out to individuals.

Cases such as these highlight the considerations discussed in the introduction of this paper. Should individual titles be promoted? Or do individual titles increase the risk of losing the land to (foreign) investors, since land can be relatively easily sold once owned by an individual? In this context, the campaign to grant women land titles led to a discussion among the different project partners on whether land titles should be owned individually (see also Enda Pronat LANDac, 2018). Many community leaders even feared that increased fragmentation of the land between the different members of a family increases the risks of land commercialization or the loss of agricultural land for family farms.

Oxfam in Malawi piloted customary land titling and registration in three communities in which, even in the matrilineal south, there was a tendency to register land under the custodianship of uncles. However, in the patrilineal north, several women started to register land in their own names because the lobbying and advocacy work of Oxfam and partners had convinced their husbands to allow them to do so. In the matrilineal south, in Phalombe, women by far outnumbered men in customary estates registration. Despite some patriarchal traits here too (for example, in principle women are supposed to have full control over the land they own, but in practice their uncles remain the de-facto decision makers), the campaign helped to maintain the status quo or contributed to increasing numbers of women registering land in their own right. As a result of Oxfam in Malawi's pilot, joint registration is being proposed in the law to enable spouses to jointly register land (instead of only the husband or wife). It is considered a midway point in reaching a compromise for strong matrilineal societies or patrilineal societies where under normal circumstances one sex would dominate land ownership to the disadvantage of the other.

Supporting Joint Land Titles

To claim women's rights to land, ADECRU and Fórum Mulher in Mozambique worked together with community associations to support to women to request land titles (DUATs in Mozambique) in the name of an association. The underlying assumption is that when women are connected in an official association, they are more protected from external threats, because they have official use rights on their land. At the same time, women can support each other to ensure cultivation of the land. Women in rural communities access the majority of their rights through their relationships with men. For widows, divorced and single women, being part of an association creates a structure in which they do not have to get married (again or at all) in order to access land. For married women, being associated offers an opportunity to become more independent from their husbands. As one interviewee recalls:

My husband now even works on the land of the women's association as an employee because it gives us more money. But I am in charge, which changed my position in our family. I like that.

Interview with Mary, 1st December 2017.

However, a case from Senegal shows that joint registration of land titles is not always a sustainable solution for women. For example, the chief of Keur Socé allocated a parcel of 2 hectares of agricultural land to a group of 64 village women. The women parceled the plot into individual pieces so each woman could grow her own vegetables. As one woman explained:

We can now all cultivate our own plot of land, but it's just a handout from the men so the women would stop complaining. There are individual men in this village owning parcels of land larger than the one we share here. We can still not inherit from our family and our husbands are still not ready to share their lands with us. When asked about the access of women to land in this village, it is easy to refer to this land we were given, however we need to share it amongst 64 [women].

Interview with Fatima, Keur Socé, February 2018.

This example shows that having access to land through a women's association does not necessarily mean tenure security for women—or an equal voice when it comes to land governance.

Supporting Increased Decision-Making Power

Another important strategy in realizing women's land rights at the local level is increasing women's decision-making power over community land. Although we see progressive laws promoting women's representation in decision-making structures relating to community land, many of these changes in the law still have to materialize on the ground. In Kenya for instance, we found that most women living on group ranches have access to land, but are rarely official members of the group ranch executive committees that collectively manage land. Women's absence in decision-making processes, and the underlying power issues, has direct consequences for the way they can benefit from the commercialization of land within areas of community land tenure. For instance, in many ranches, sand harvesting became a lucrative business that brought a considerable amount of money into the group ranch treasury. But during the focus group discussions in Laikipia there were discussions around the lack of transparency on money earnt through this business and the use of the profits. As one of the female participants mentioned:

In this community I can access all the land I want. I can access from here to there [spreads arms]. I can also access water points, the center. When I get sick, as a member I can also go to the group ranch and I will get 1500KES or so, to go to the hospital. The sand harvesting is not equally accessed, though [...] It would be good if women also get written in the register, so the sharing of the dividends can be equal. Right now, it is only husbands who can claim for anything. If I want something, the claim has to be made through my male relative who is written in the register.

Interview with Adriana, 21st November 2017.

Melissa's case shows that the money gained from sand harvesting from communal land is supposed to be paid into the group ranch treasury and redistributed among the members in the form of bursaries. But in practice, because of the organizational structure of the group ranch (governed by men), many women are unable to claim their share of the bursaries. Kenya's New Community Act of 2016 addresses these uneven power structures. This act prescribes that all boys and girls from 18 years of age onwards should be registered as members of the group ranch and be allowed to attend assembly meetings, where decisions about the community are made. The implementation of these issues started with the launch of a working group that aims to transit all group ranches to community lands and register all unregistered community lands. In addition, new community land management committees should be elected while respecting the two-thirds gender provision6. However, the implementation of this act is slow. So far, the ministry has issued only two inaugural community land titles in Laikipia. Groots Kenya actively advocates for progress and contributes to implementation. The organization strengthens capacities of women and informs them of the new leadership opportunities created by law, supports them to take part in elections, and critically observes the election to ensure total adherence to gender provisions. Lastly, Groots Kenya communicates with the Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning on any emerging issues (as elaborated above). In this sense Groots Kenya, like many other non-governmental and even international organizations, have not only played a significant role in translating the law, but also in realizing the new land laws at the local level.

Keeping Track of Progress in Securing Women's Land Rights

To be effective, the above-mentioned activities must also be combined with participatory monitoring and evaluation activities to track progress in translating and implementing women's land rights. During the project it became clear that, together with community members, grassroots organizations already play an important role in “keeping track of women's land rights” by two concrete activities: collecting data for and by rural women and movement building.

Collecting Data for and by Women

The data we collected within the framework of this action research program show that there is still a considerable mismatch between perceptions on women's access to land and governance of natural resources and the actual situation on the ground. A baseline survey on women's land ownership and women's land rights in Malawi showed that 99% of the respondents in the three districts where we conducted research considered that they own the land where they live, despite not having a land title (Oxfam in Malawi LANDac, 2018). Apart from misperceptions, our research has also shown that meaningful official data on gender inequalities is largely absent. Registers on land ownership in general, and female land ownership in particular, are not monitored. In cases where women appeared to be the original owners, the land titles had already passed on to second-generation male relatives, without changing the registry. In this sense, current official registries are not a reliable source of data on women's land rights.

As a consequence, local organizations within our project set up activities to address this data gap and empower women to collect information on the status of women's land rights in their communities. They assisted rural women in keeping records on the numbers of women owning land and being represented in leadership functions when it concerned management of communal land. Groots Kenya, for instance, developed a community-led mapping tool to support women to map land ownership and to generate public land data. By involving the local community in the research, not only data was collected, but people were made aware of the situation in their own community. This was illustrated by several in-depth interviews conducted with 22 local women in rural Kenya. The case of Mary illustrates how this approach has led to capacity building at the local level and mobilizing action on the ground. Mary participated in the community-led research in the Tiamamut Group Ranch in Kenya. She indicated that she was very agitated by the results that showed that in the 9 group ranches, women accounted for <10% of the registered occupants of the land. This is why she decided to contest the position of a community land-management committee chair in the upcoming elections.

As we also saw in the other cases described in the previous section, the lack of female representation in decision-making bodies for group ranches was rendered visible through this exercise. The community-led mapping exercise showed that in community land regimes—as in private land regimes—women had very little documented control over the land. The direct involvement of the women in data-gathering processes provided an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges surrounding public land administration and management as well as halting land grabbing and encroachment. In addition, community-based research enables participants to articulate their challenges, co-produce the evidence to support their claims to land, and shows them how to engage in advocacy to claim their rights with their husbands, family, the local municipality, and beyond. Rose, for instance, reflected on how her participation in the ActionAid's social action study, a community-based research project on women and natural resources in Kenya, improved her ability to articulate issues7:

The training [to participate in the social action study] empowered me. No one can challenge me on what relates to my rights.

Interview with Alice, date unknown, Baringo County.

Using some of the skills and insights gained from this training enabled Alice to reclaim her one acre of land she had lost. She had bought the land from someone who afterwards, during a court process, claimed that Alice was only renting. Alice listed some of the key skills she had gained: “my ability to approach people, frame my questions right, ability to communicate both convincingly and with diplomacy, speaking with confidence” (Oxfam in Malawi LANDac, 2018).

Alice's case clearly shows how important and empowering women's involvement in research on tracking progress in the realization of women's land rights can be. It shows them that their tracking work is based on law. It also teaches them the importance of setting tracking priorities—and how to practically track changes. Finally, it enhances their capacity to apply these skills.

National Alliances and Movement Building on Women's Land Rights

Although most of our project activities started at the local level, there was a clear need to align local initiatives with policymakers at the national level and to create multilevel and multi-stakeholder coalitions. Local partners in Senegal, Mozambique, Kenya, and Malawi developed national alliances to reinforce synergies between different stakeholders working to promote women's land rights across each country. In Senegal, this national alliance has reinforced advocacy work, by holding regular meetings with the National Union of Associations (an association of locally elected representatives of Senegal) to advocate for women's access to land. This forum has allowed rural women to lodge their complaints with the Ministry of Women and the Ministry of Agriculture and deputies and members of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council, which have made commitments to improve the situation of rural women. Together with other mobilizations, the forum has allowed for a real debate on the situation of rural women and pushed the president of the Republic to take a stand on the issues during the International Women's Day celebrations held in March 2018.

In Mozambique, the rural women's declaration has opened a political dialogue with the president and government authorities in order to advocate for women's rights and for gender equity. Moreover, in Maputo in September 2020, a coalition of CSOs united women from all over the country in the Mozambican Forum for Rural Women (FOMMUR). They gathered for a discussion and reflection on women's land rights in the context of the prevailing land grabs and changes to the land legal framework. The main objective of the meeting was “to define a rural women's political position on the current National Land Policy review process” (Ntauazi et al., 2020). It is too early to know its outcomes, but the meeting provided a space for women from all over the country to discuss concrete women's demands, agendas and priorities related to land, water and other natural resources.

As we also saw in the other countries, activities that focus on giving women a voice in current debates on women's land rights, such as the organization of national conferences, have resulted in an effective strategy to encourage dialogue between the local level and the national and international levels of policymaking. This encourages a two-dimensional process, advocating for women's needs and realities to be taken into account in lawmaking and higher-level policy discussions on women's land rights in general. And women's voices can be further amplified by strengthening networks for women, not only at the local, regional and country level, but also at the international level. We have learnt that regional and country exchanges between grassroots organizations is of major value (ActionAid Kenya et al., 2018).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have focused on the vernacularization of women's land rights, a process defined as the translation of ideas from the universal and (international) spheres to local contexts and vice versa (Merry and Levitt, 2017). While progressive legal frameworks exist in Malawi, Kenya, Senegal, and Mozambique, local organizations (such as NGOs, CSOs, and grassroots movements) play an important mediating role in the action arena. They facilitate bottom-up process of translating, implementing and keeping track of women's land rights from the local to the national and international level and the other way round. In this sense, the paper has clearly shown that the vernacularization of women's land rights is a two-dimensional process. On the one hand you have the still rather top-down strategies, whereby international and national ideas about human rights are translated to the local level. On the other hand, local actors and practices nurture national processes of lobbying and law-making from the bottom-up. And it is especially this second dimension of vernacularization that deserves more attention in future research and action on women's land rights.

We have elaborated that the vernacularization of land rights in Malawi, Kenya, Senegal, and Mozambique is shaped by three categories of activities that find their origins in local actions and initiatives, but were put into practice with the support of grassroots organizations such as Groots Kenya, ActionAid Kenya, Enda Pronat in Senegal, Oxfam in Malawi, and Fórum Mulher and ADECRU in Mozambique. The first category of activities focuses on the translation processes in which women's land rights are expressed in local languages and adapted to the local context, through media outreach, community workshops, and by collaborating with local champions. The second category of activities focuses on the concrete realization of women's land rights at the local level, ranging from initiatives to support women to register land in their individual or group name to initiatives that increase women's participation in decision-making processes. The third category of activities engages local women to collect data on and jointly keeping track of women's land rights in their communities. Taken together, these activities have been shown to be important in countering certain misconceptions about women's land rights, in strengthening local knowledge on women's land rights and identifying and tackling obstacles to claiming more equal land rights for women and men. The co-production of data and knowledge between community members, grassroots organizations, and academic partners is important to be able to advance the cause of women's land rights on the ground. It has helped to overcome the implementation gap between state law and local practice and to generate evidence and monitor progress. In combination with the creation of national alliances and movement building, this has helped to empower women to stand up for their rights.

Moving forward, we argue that the starting point for analysis and change must begin at the local level, using co-created and in-depth local knowledge. This is not only relevant for realizing real progress on the ground, but also for further acknowledging the importance of local organizations and their mediating role in the action arena of women's land rights. Although grassroots initiatives have become ever more important in women's land rights programs, funds for a locally driven women's land rights agenda are still limited and are oriented toward short-term results due to ad hoc funds for specific projects and activities. As one of our project partners mentioned, funds for women's land rights projects are limited because of the complexity of the issue and the difficulty of showing direct results on the ground. As a consequence, one of the biggest challenges facing grassroots organizations is to following up vernacularization activities that are implemented in the framework of concrete women's land rights projects and programs in the long term. The WLRA program provided additional funding for scaling up grassroots initiatives that had already proven to be successful in claiming women's access to and control over land and other natural resources. As such, continuity could be given to previously successful projects such as the Groots Kenya's community-led mapping tool, registration programs in Malawi and Senegal and Mozambique's Forum for Rural Women. More structural support for these types of initiatives in the longer-term will further encourage the progressive change already envisioned in the revised legal frameworks on land and other natural resources of many African countries.

In addition, the empirical findings from our study show the need to shift the focus from a top-down, globally set agenda on sustainable development and gender equality to first understanding local realities and needs. Participatory research approaches provide a promising approach to doing so. They can be time consuming, they have to tackle underlying power dynamics, and they might not provide instant results. But they are an important method for exchanging knowledge at the local level within and between communities, and for empowering grassroots women. The process of continuous collaboration such as that used in the WLRA program—between grassroots organizations, community members, and researchers—has been successful in strengthening the movements and enlarging the number of champions advocating for women's land rights in their communities. It has clearly shown that the debate on women's land rights should further shift from its narrow focus on legislation alone toward a holistic approach that takes into account the full action arena and initiatives that aim to strengthen women's access to and control, and ownership over the land they cultivate and reside on.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors agree to be accountable for the content of this paper.

Funding

This LANDac Women's Land Rights in Africa (WLRA) program was made possible with financing from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments