94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 23 February 2021

Sec. Social Movements, Institutions and Governance

Volume 5 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.640171

This article is part of the Research TopicTraditional Food Knowledge: New Wine into Old Wineskins?View all 11 articles

Ina Vandebroek1*

Ina Vandebroek1* David Picking2

David Picking2 Jessica Tretina3

Jessica Tretina3 Jason West4

Jason West4 Michael Grizzle5

Michael Grizzle5 Denton Sweil6

Denton Sweil6 Ucal Green7

Ucal Green7 Devon Lindsay8

Devon Lindsay8Jamaican root tonics are fermented beverages made with the roots, bark, vines (and dried leaves) of several plant species, many of which are wild-harvested in forest areas of this Caribbean island. These tonics are popular across Jamaica, and also appreciated among the Jamaican diaspora in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Although plants are the focal point of the ethnobotany of root tonics, interviews with 99 knowledgeable Jamaicans across five parishes of the island, with the goal of documenting their knowledge, perceptions, beliefs, and oral histories, showed that studying these tonics solely from a natural sciences perspective would serve as an injustice to the important sociocultural dimensions and symbolism that surround their use. Jamaican explanations about root tonics are filled with metaphorical expressions about the reciprocity between the qualities of “nature” and the strength of the human body. Furthermore, testimonies about the perceived cultural origins, and reasons for using root tonics, provided valuable insights into the extent of human hardship endured historically during slavery, and the continued struggle experienced by many Jamaicans living a subsistence lifestyle today. On the other hand, the popularity of root tonics is also indicative of the resilience of hard-working Jamaicans, and their quest for bodily and mental strength and health in dealing with socioeconomic and other societal challenges. Half of all study participants considered Rastafari the present-day knowledge holders of Jamaican root tonics. Even though these tonics represent a powerful informal symbol of Jamaican biocultural heritage, they lack official recognition and development for the benefit of local producers and vendors. We therefore used a sustainable development conceptual framework consisting of social, cultural, economic, and ecological pillars, to design a road map for a cottage industry for these artisanal producers. The four steps of this road map (growing production, growing alliances, transitioning into the formal economy, and safeguarding ecological sustainability) provide a starting point for future research and applied projects to promote this biocultural heritage product prepared with Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS) of plants.

Traditional and indigenous fermented plant mixtures, multi-component alcohol infusions, and bitter tonics, consisting of roots, bark (and other parts) of wildcrafted species, are prepared and drunk as beverages, medicines, or for sociocultural purposes around the world, e.g., kaojiuqian in Shui villages in China (Hong et al., 2015); garrafadas in Brazil (Barros dos Passos et al., 2018); mahuli (country liquor) in India (Kumari et al., 2015); and bita in French Guiana (Tareau et al., 2019). The preparation and use of alcohol-based or fermented plant mixtures made with roots and bark of wild and cultivated species has also been recorded both in Africa and in countries across the Atlantic Ocean with a significant Afro-descendant population, such as in several Caribbean islands and the wider Caribbean region, especially as aphrodisiacs and for treating sexually transmitted infections (Cano and Volpato, 2004; Payne-Jackson and Alleyne, 2004; Vandebroek et al., 2010; van Andel et al., 2012). In Jamaica, artisanal fermented decoctions that include several wild-harvested and forest plants are known as root tonics (Picking and Vandebroek, 2019). These tonics play a dual role as food and medicine, and have been recognized as a product made with Neglected and Underutilized Species of plants (NUS) that shows potential for income-generation, empowerment of local communities, and reaffirmation of their cultural identity (Padulosi et al., 2013).

Jamaican root tonics are commonly produced and consumed at home, or sold locally in the informal economy, and are widely appreciated by Jamaicans as an energizer, aphrodisiac, for blood purification, and for the promotion and maintenance of good health (Sobo, 1993). Although root tonics are inherently a Jamaican product, their impact reaches beyond this Caribbean island, as their commercialization by a handful of producers in Jamaica and overseas has followed the Jamaican diaspora to London, Toronto, and New York City (Dickerson, 2004; Picking and Vandebroek, 2019).

The popularity of root tonics as a symbol of Jamaican biological and cultural heritage (in short “biocultural heritage”) stands in stark contrast to the breadth and depth of their scientific study. So far, one paper has reviewed the plant diversity of root tonics, from a study that used data from labels of listed ingredients on commercial products (Mitchell, 2011). In addition, the same paper contributed to a comparison of plant mixtures used as aphrodisiacs across the Caribbean and Africa (van Andel et al., 2012). Data is also lacking about the history and cultural context of their use, as well as levels of consumption, domestic production, and sales of artisanal root tonics across Jamaica, and how artisanal root tonics differ from commercial products.

The diverse biological, medical, historical, and cultural dimensions of Jamaican root tonics invite several important research questions, including related to the botanical identity of the plant diversity found in recipes, the illnesses treated and purported health boosting properties, their historical origin and present-day cultural importance, and their potential for sustainable heritage development for the benefit of small-scale Jamaican producers.

The term “sustainable development” is widely used with varying definitions based on the context and purpose of use, but was first coined by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987. Common pillar structures found in discussions about sustainable development touch on its economic, social, and ecological dimensions. For the purpose of this paper, we are using the term “sustainable heritage development” (Keahey, 2019) and incorporate a fourth pillar, namely cultural sustainability, which seeks to recover and protect cultural identities through a celebration of local and regional histories and the passing down of cultural values to future generations (Farsani et al., 2012). The cultural pillar of sustainability exists in parallel to ecological, social, and economic sustainability, and stresses the relation of heritage to social cohesion and local identity (Soini and Birkeland, 2014).

In this paper, we focus on the intangible cultural aspects of Jamaican root tonics, using information from ethnobotany research and oral history testimonies as a lens to explore the potential for development of an equitable Jamaican cottage industry for artisanal root tonic producers. Our primary goal was to conduct ethnobotanical research to increase the scientific knowledge base about root tonics. Our secondary goal was to move beyond research and make this data applicable and relevant to local communities. Specifically, this paper uses a mixed methods approach based on ethnobotany and oral history research, and a contextual analysis of the production market, to understand the “emic” (insider's or community) perspective of root tonics (Gros-Balthazard et al., 2020), addressing the following questions: (1) What are Jamaican root tonics? (2) Why do Jamaicans drink root tonics? (3) Where did the tradition of making root tonics come from (who developed this tradition)? (4) Who is especially knowledgeable about root tonics (5) What is the profile of an artisanal root tonic producer? and (6) What should a roadmap to a socially just Jamaican root tonics cottage industry look like?

Prior to fieldwork, we developed a survey instrument (questionnaire) and a verbal consent form, and obtained permits for fieldwork, including ethics review approval from The University of The West Indies, Mona, and a research permit from the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) in Kingston that specified the terms for collection and distribution of botanical specimens.

At the beginning of fieldwork, we first approached communities across the island through our network of contacts, explained the project and its research objectives, listened to their opinions, and waited for their expression of interest in the study. Upon receiving positive feedback, we planned a visit, stayed in the community for several days to conduct interviews, guided by a local community member, who also facilitated the recruitment process and recommended potential interviewees. To acknowledge the important contribution of these local collaborators to the success of this project, they are co-authors on this paper.

Before each interview, we explained the goals of the project and asked for the participant's verbal, free and prior-informed consent (FPIC). Written informed consent was obtained for Figure 2. We conducted face-to-face interviews in Jamaican Patois, with the interviewer asking survey questions and recording the answers on paper or a laptop. To protect their identity, study participants received a number, nickname, or initials on the questionnaire, unless they explicitly gave their permission to be acknowledged for their participation in the project. For the purpose of this scientific paper, data of all study participants was anonymized. Our questionnaire contained 23 questions that pertained to five sections: (1) Definition and use-patterns of root tonics; (2) free-listing of plant ingredients of root tonics; (3) preparation of root tonics; (4) opinions about root tonics; (5) socio-demographic information of participants.

In total, between February 2018 and May 2019, we interviewed 99 people, 88 men and 11 women, across five parishes (Figure 1). The lower number of women reflects the gendered nature of plant collectors and root tonic producers that is skewed toward men. The age of study participants varied from 26 to 88 years, with an average (±STDEV) of 59 ± 13 years. Most people (63) were farmers, seven persons were retired; other professions included vendor (7), herbalist (6), mason or construction worker (6), “roots man” who prepares and sells roots (5), while one or two people reported other occupations, such as fisherman, cane cutter, artist, steelworker, higgler, shoemaker, dressmaker, musician, artist, security guard, or taxi driver.

Figure 1. Map of Jamaica with parish boundaries and parish names (light gray). Black dots and black names represent the five communities (and neighboring areas) where ethnobotanical research (interviews and plant collecting) took place (parish name is given between brackets): Flamstead (St. James), Pusey (Manchester), Downtown Kingston (Kingston), Retreat (St. Thomas), and Windsor Forest (Portland).

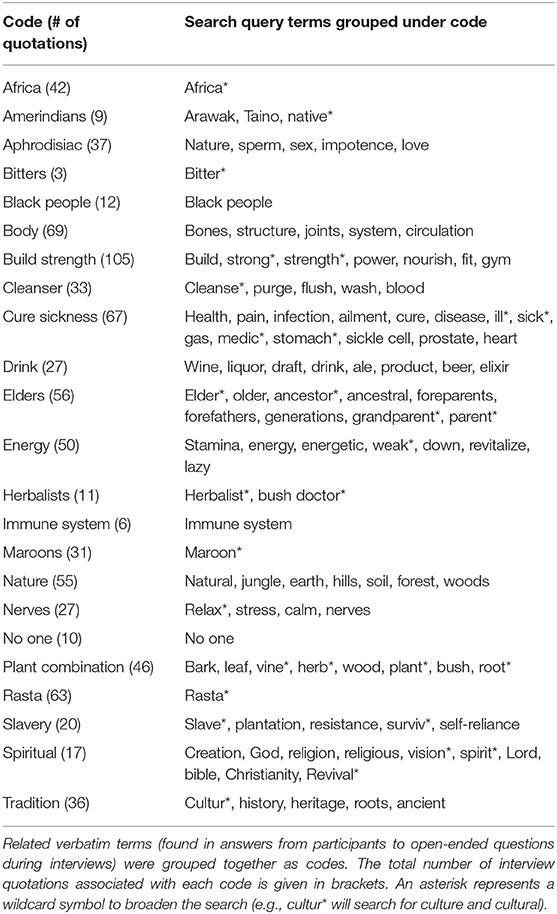

Interview answers from all 99 participants were entered and organized in an Excel spreadsheet. Column headings consisted of variables (gender, age, occupation, religion, number of plants reported…) or survey questions, while rows and cells contained individual answers from participants (see Supplementary File). The formatted Excel spreadsheet was imported into Atlas.ti, and four central interview questions were coded for qualitative analysis: Q1-Definition (what is a root tonic?), Q2-Motivation (why do Jamaicans drink root tonics?), Q3-Origin (where does this tradition come from?) and Q4-Knowledge keepers (who is especially knowledgeable about root tonics?). After several rounds of careful reading through all interview answers, we identified and assigned 23 codes, based on the recurrence of verbatim terms that were expressed in answers from interviewees to these open-ended questions (Table 1). Next, Atlas.ti 8.4 was used to explore relationships between these codes through co-occurrence tables and visual networks.

Table 1. After reading multiple times through the interviews, search query terms were identified based on their recurrence, and subsequently used to conduct additional searches to cover all interviews.

Based on the responses from interviews, we developed four central questions to assist in creating a road map for the sustainable development of a cottage industry for root tonics, as follows: (1) What is our definition of sustainable development? (2) What are the steps that a traditional, small-scale root tonic producer can take to develop and scale-up their production in the informal and formal sectors? (3) How can a traditional root tonic be improved upon for sale to the general local population? (4) How feasible is it to suggest a cottage industry; what would be the ideal socio-economic situation for traditional root tonic producers in Jamaica, and how might this scenario be realized in the future? After developing further sub-questions and grouping these thematically, we determined that the major topics to be researched further were the current industry environment, marketing, traditional knowledge, culture, and health.

We based the definition of sustainable heritage development used in this paper on the results of a review of the literature. To find journal articles, we searched Google scholar and EBSCOhost using the keywords “ethnobotany,” “ethnobiology,” “culture,” “rooibos,” or “traditional knowledge” and “sustainable development,” as well as “cultural sustainability.” Rooibos was used as a search term as an example of a plant species that has specific geographical origins and is used in a beverage with established cultural significance to the people of the region in which it is cultivated.

We then defined the goals of the roadmap and used interview responses, direct (participant) observation of Jamaican society, its culture and economy, and research into the resources available to informal micro enterprises to identify barriers that artisanal root tonic producers might face. Internet searches were performed to identify the relevant public and private sector authorities and resource-providers in the areas where support is needed, and a review of each of the relevant entities' websites was conducted to identify what resources, publications, training, and support are being offered to the micro, small and medium enterprise (MSME) sector, particularly for micro enterprises in the agro-processing sector.

The level of production and the sales environment gleaned from the survey results were used to determine the assumed starting point for the root tonic producer to be a home brewer with sales scattered throughout the year, with production being limited to usually a 5-gallon batch of tonic sold over several weeks to mostly people within the producer's social network. Based on this assumption, we determined what resources would be available, and sought attainable strategies to improve this producer's situation, with steps that can be taken within the informal economy until the producer feels empowered to formalize their root tonic business. The identified barriers were used to create a road map that would seem manageable, and culturally acceptable, to the average producer. Currency conversions to USD in this paper use a conversion rate of $1 USD to $148.74 JMD, the rate available on August 12, 2020.

Individual interview answers to a selection of the survey questions and psychosocial data can be found in the Supplementary File.

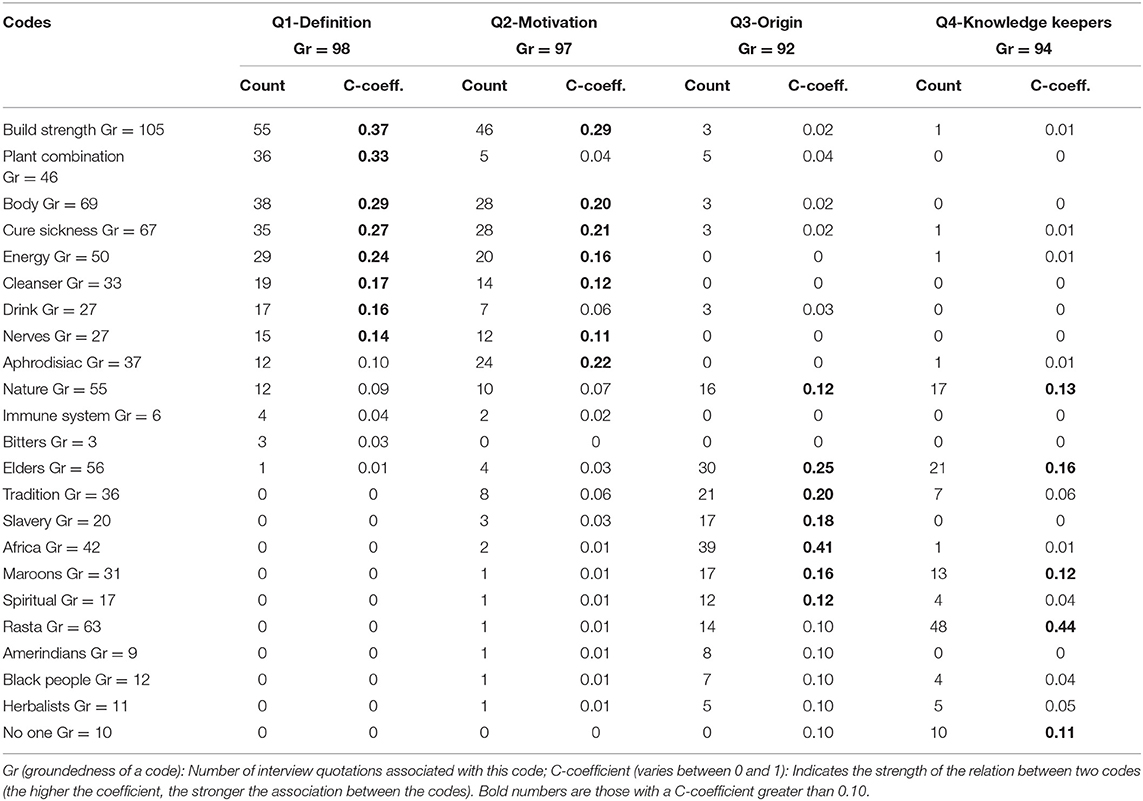

In their answers to this question, Jamaican participants emphasized a root tonic's strength-building quality as a drink made of a combination of plants that supports and cleanses the body, cures sickness, provides energy, and settles the nerves. Table 2 shows the recurrent use of these terms by their counts in quotations, as well as their associations with four questions (Q1 to Q4) through the C-coefficient that varies between 0 (no association) and 1 (perfect association) (Table 2).

Table 2. Quotation counts and strength of association (measured as the C-coefficient) between each code and four interview questions (Q1-Definition: What are Jamaican root tonics? Q2-Motivation: Why do Jamaicans drink root tonics? Q3-Origin: Where does this tradition come from? Q4-Knowledge keepers: Who is especially knowledgeable about root tonics?).

The number of plant species used in root tonics varied between 4 and 55, with an average of 15 ± 8 (STDEV) plants. Persons who prepared root tonics used the roots, bark and whole chopped liana parts of these species, and for some also the leaves, all of which needed to be dried before use. Several producers stated that it was important to work with plant parts that were fully dried, or that otherwise the tonic would spoil. In colloquial language, a root tonic is often referred to as “roots.” According to Table 2, root tonics are not considered bitters, with only three people mentioning this term, of which one person explicitly clarified that “bitters is not a roots” (MT3, male, age 60). In addition, the difference between a tea and a root tonic was also explained as follows: “[It depends on the] amount of different things you put in it, for a tea [you] just [put a plant like] sarsaparilla, ramoon, chainey root. For a tonic you put more things, 20 different something, bark and roots” (Windsor Forest-1, male, age 62).

The preparation of a root tonic is a time-consuming process that involves the collection, drying, and boiling of various plant ingredients in water, after which the decoction is cooled, strained, and bottled. The whole process from collection to finish can take several weeks, or even months. Most participants reported collecting plants during a specific moon phase, often three days before or three days after the full moon, when the moon is considered strongest (Figure 2). Important plant species used in root tonics, notably vines and roots, are wild-harvested in forests and other remote ecosystems that are difficult to reach and require long collection trips on foot. The botanical diversity of root tonics falls outside the scope of this paper and will be addressed elsewhere, but two of the most popular species across the five study areas were lianas of the genus Smilax, belonging to the Smilacaceae: Chainey root (Smilax canellifolia Mill., illegitimate synonym Smilax balbisiana Griseb.), and sarsaparilla (Smilax ornata Lem., synonym Smilax regelii Killip and C.V.Morton). The plants are usually dried naturally in direct sun or shade, over several days or weeks (Figure 3). Each person has their own specific recipe, which we did not record during interviews, out of respect for, and to protect, their intellectual property rights (IPR). The general process for preparing roots involves boiling the plant mixture over several hours, traditionally over firewood, after which the liquid of the “first boil” may be decanted and either finished at this stage, or new water is added, and the whole process repeated (Figure 4). Then this liquid is added to the previous, and the preparation is left to cool. Next, it is bottled (Figure 5) and put down in a cool place for a month or longer, which is described as “curing.” Several persons noted that in the past, the bottles were often buried under the earth to keep them cool and slow down the fermentation process which prevents the glass from bursting. Ingredients that can be added as a preservative to keep a root tonic from spoiling included burned sugar, molasses, honey, wine, or rum. A root tonic can be consumed directly as a shot from the bottle, or as a punch by combination with some of the following ingredients, such as condensed milk (or coconut milk sweetened with honey), Irish moss, rum, Dragon Stout, or Guinness beer.

Figure 2. Collecting roots and lianas (called “wiss”) of various wild-harvested plant species to prepare root tonics in St. Thomas parish, at the fringes of the John Crow Mountains, 3 days before the full moon (photo credit IV).

Figure 4. Preparation of a root tonic showing boiled plant ingredients after decantation of the liquid. Often, depending on the producer, new water is added for a “second boil.” This process can take several hours to an entire day (photo credit IV).

Figure 5. The final artisanal product is stored in recycled bottles of rum (or occasionally other types of bottles, such as wine or Campari), often with their original labels (photo credit IV).

Jamaicans tend to consume root tonics in a shot glass in the morning and/or evening, especially when they need energy, or to relax the mind. When asked whether men, women, and children all drink root tonics, 84 people (85 percent) answered “everyone,” whereas 11 people said “only adults,” 2 people “mostly men,” one person said it depended on the type of root tonic, and another person did not answer the question. However, 30 people specified that children should only drink a small amount, measured as one or two spoonsful, or that their root tonic should be diluted with water. Three people added that root tonics should not be consumed by pregnant women.

It was not until interview participants were asked about reasons for drinking root tonics that their role as an aphrodisiac beverage came to the forefront. Other important functions, such as strengthening, building and cleansing the body and blood, curing sickness, providing energy, and settling the nerves had already been emphasized previously in response to the question “What is a root tonic?” The strength-building capacity of root tonics was associated with working hard (9 answers), as the following quotes illustrate: “It help[s] when we work. It build[s] energy in your body, give[s] you a stronger mindset. Your system feel[s] different, you [don't] feel pain” (Windsor Forest-1, male, age 62), and “It make[s] you stronger, [when you do] hardcore work, you [don't] back down, [when you] lift weight, [it is] good for [your] backbone, [it] strengthen[s] your back” (Windsor Forest-5, male, age 61).

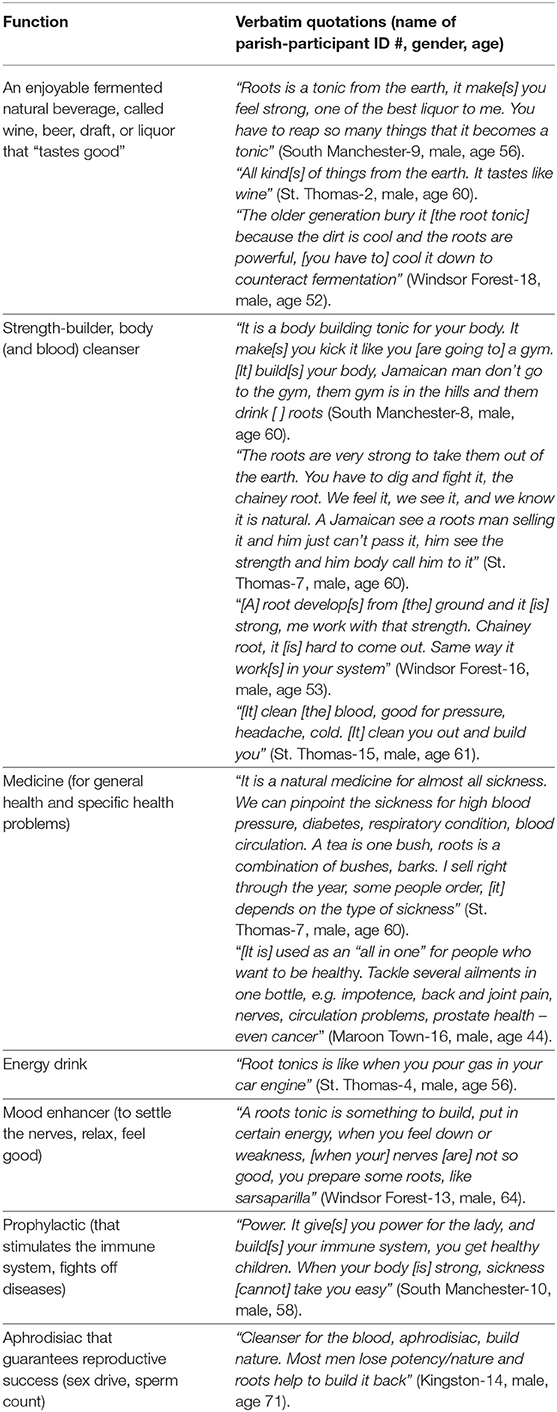

We identified at least seven functions of root tonics from the interviews, which complement and/or overlap each other (Table 3). One study participant described the multifunctionality of root tonics as follows: “It has a lot of meaning[s]—a product that can help sickness, like a medicine. It has a lot of different things, substance” (St. Thomas-6, male, 56 years). When Jamaicans mentioned the word “bush” during interviews, they referred to several possible meanings: Any plant, a specific plant species, a specific natural area or forest known to both people who hold the conversation, or any (unspecified) wild natural place.

Table 3. Complementary and/or overlapping functions of root tonics, and relevant associated quotations selected from interviews with 99 Jamaicans in five parishes.

In their answers to this question, study participants emphasized the Africa connection (39 quotations, Table 2). They described root tonics as a tradition with deep spiritual and natural connotations passed on by African elders, who endured the brutal hardships of slavery. Several people referred to Creation, God, visions, or a spiritual origin. Someone said: “Older head people, them maybe learn it from the Spirit. Some people recognize it spiritually, the bush become[s] like a spiritual thing, a living soul, them [plants] have their own purpose” (Windsor Forest-7, male, age 66). Another participant stated: “African[s] – our history, they come here, a lot of beating and harassment that we [were] getting, we just go [in the] woods and find some bush to keep strong” (South Manchester-9, male, age 56). A third person said: “That come from slavery when the white man take away the medicine, and they [the Africans] have to seek their own medicine to stay alive. They try it out and feel nice, and then tell them bredren [friends]” (Windsor Forest-13, male, age 64). Someone else explained: “Slaves, they never got good food from white slave masters so they consumed the roots” (Kingston-9, male, age 62).

Interview answers showed African agency as an act of resistance to slavery instead of passive endurance, with several people associating root tonics with the Maroons who freed themselves from enslavement, and who engaged in sophisticated guerrilla warfare and revolts against the British colonizers to maintain their freedom, while living deep in the Jamaican mountains where they thrived, as the following three quotes illustrate: “The Maroons are the first to release themselves and go into the hills. I always said my ancestors is from that group of people and that is where I get that nature from” (St. Thomas-8, male, age 64). “The Maroons ran away and survived in the forests and they started the tradition [of boiling root tonics]. But their knowledge originated out of Africa. They tapped into the knowledge in order to survive” (St. Thomas-10, male, age 61). “Maybe [it came from] the Maroons – them [are] a rough people, they fight wicked” (Windsor Forest-16, male, age 53). Eight people also referred to Amerindians, postulating that the original inhabitants of the Caribbean islands may have exchanged their knowledge with Africans: “It start[s] from how you learn it, the traditional people, from the Tainos them, the Indians them, they was here first. From Cuba most of them spring from. Because we [Africans] come after the Taino, find out the knowledge, and pass it on the same way” (Maroon Town-9, male, age 67). “It is an African tradition. [The] Arawak (Taino) [are the] medical experts in South America and teach the Africans as a slave. All top herbalists are Indian people (Arawak). After Africans become enslaved, them mix together” (Windsor Forest-8, male, age 45).

Several of these and other answers also highlight the continuing relationship that exists between the use of root tonics and resilience as a people, dynamically finding and employing solutions to respond to, and overcome, adversity and stress, from the past into the present: “In Jamaica, when people escape[d] from plantation without medication, fi [in order to] build up fi dem [their] body, they test these things [bush, plants] and combine them until they find the good ones. Even today, if you mix two bush and test them, you can tell if this [is] good fi [for] you” (St. Thomas-7, male, age 60). “[Jamaicans drink root tonics because they] can't afford doctors. Self-reliance, [they] drink [it] and feel much better” (St. Thomas-10, male, age 61). “That thing [root tonics] gi we [gives us] resistance; when you work and you naah [do not] feel energy, you slow, you say yah man [yes man], me boil some roots. Your performance [will be] better” (Windsor Forest-1, male, age 62). “When you come from work and you stress, you can drink [a root tonic]” (South Manchester-1, male, age 65).

Half of all study participants (50 people) mentioned Rastafari as persons who are especially knowledgeable about root tonics (Supplementary File), and 43% self-identified as Rastafari when asked about their religion. The following quote links “roots,” a term that represents both the physical roots of plants that grow in the earth and the cultural roots from the ancestors, to Rastafari and other Jamaicans who believe in nature and culture as a way of life: “It [knowledge about root tonics] is coming from the ground (roots, ancestors). Rasta, it come[s] back to the people who are building roots. You don't have to be a Ras [Rastafari], if you believe in your roots. [It is a] way of life. Ras may be living in the hills, but [they are] eating the right stuff, not using too much fertilizer [chemical pollutants]. They stick to the roots” (St. Thomas-6, male, age 56).

Elders were considered another important group of knowledge holders. Having a strong connection with nature, or living in the hills (17 quotations), which are associated with the lifestyle of the older generations, Maroons, and rural Rastafari, came to the forefront in answers to this question (Table 2). The following quote illustrates this: “Rasta and Maroons, [you] cannot leave out the Maroons, enough things Rasta learn from them. Rasta keep this thing alive, the roots tradition and natural living tradition. Rasta [are] drawn to naturality and Rasta [are] no[t] quick [to] go [to the] doctor” (St. Thomas-7, male, age 60). On the other hand, ten people also replied that not one specific group was especially knowledgeable and said that root tonics are prepared by Jamaicans across Jamaica.

Almost everyone (97 of 99 people interviewed) drank root tonics, whereas the number of people who reported preparing, collecting plants, and selling root tonics was 87, 84, and 61, respectively. Six persons who sold root tonics (10%) did not collect the plant ingredients themselves; they were all vendors in the capital, Kingston. However, everyone who sold root tonics also prepared them. Root tonic makers and vendors self-identified predominantly as Rastafari, adhering to a natural lifestyle (40 people), whereas 25 people reported to be Christian, 19 stated no religion, two did not want to answer this question, and one person declared to be Zionist. These producers and vendors were predominantly male (78 of 87 people), middle aged to senior (average age of 58 ± 13 years), and embedded in a social network of family and friends who follow the tradition of “boiling roots.” However, six study participants who sold root tonics were younger than 40, with the youngest being 26 years. Producers learned about root tonics from multiple, complementary and overlapping, sources, including: Elders in the community and other relatives (36 people), parents (32 people), grandparents and great-grandparents (28 people), traditional specialists such as roots men, herbalists, bush doctors, and Maroon mothers (11 people), God, visions, and spirituality (5 people), friends, referred to as “bredren” (5 people), books (5 people), experimentation (4 people), health stores (1 person), the internet (1 person).

The occupation of root tonic producers consisted of farmers who “trot the hills” (in rural areas; 53 of 68 people), market or street vendors (in the capital; 7 of 19 people), and sometimes herbalists or “roots doctors” (11 of 87 producers). They were local producers who operated in the informal sector, without established businesses or products that have been packaged for commercial sale. Root tonics were sold directly from the producer's home, roadside stalls, small community shops, or more structured market stalls. Occasionally, the artisanal producer will travel to deliver products directly to consumers or to sell their product at festivals, other events, or on the street. The majority of vendors reported selling their product to locals (56 people). Of these, less than half (22 people) also sold to tourists, foreigners, and visitors. Just four persons said they only sold to the latter group.

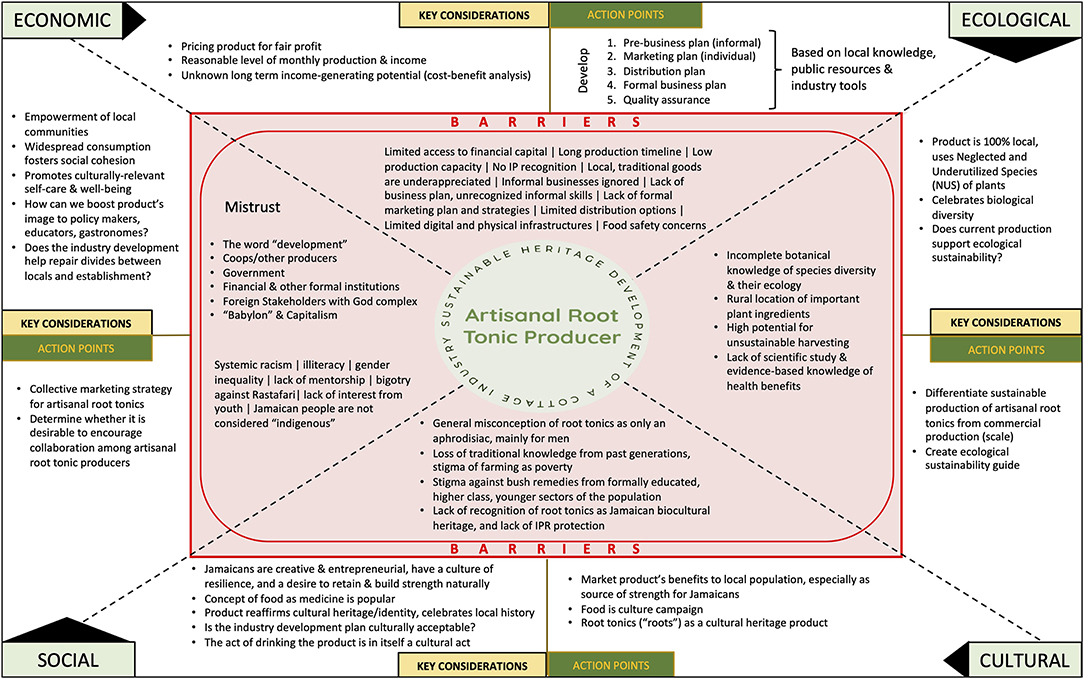

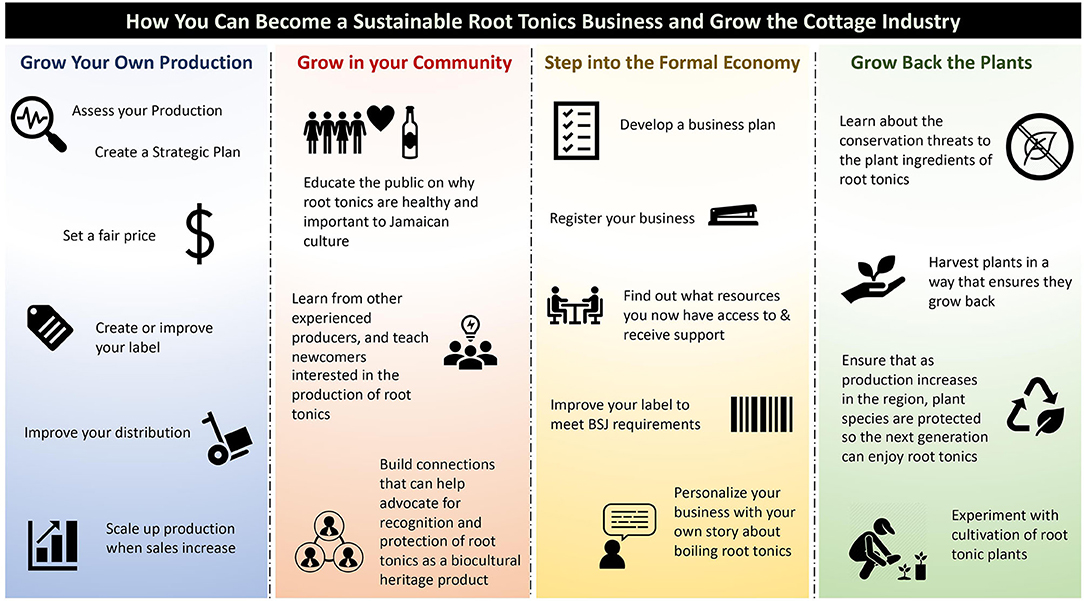

Using the four pillars (economic, ecological, cultural, and social) of sustainable heritage development, we identified the following key considerations and action points in preparing a road map for a root tonics cottage industry, while also pinpointing potential barriers that producers and this cottage industry might face (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Identification of key elements for the creation of a road map for sustainable development of root tonics (road map shown in Figure 7), based on four pillars (economic, ecological, cultural, and social). The arrows and diagonal dotted lines indicate and delineate the barriers, key considerations, and action points that are associated with each pillar. For example, for the ecological pillar, one of the barriers is that knowledge about the plant species used in root tonics (botanical identity and plant diversity) is incomplete, whereas a key consideration is that the production of root tonics is based on the use of local, Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS) of plants; an action point for the development of a road map is to distinguish between sustainable production at a smaller, cottage industry scale, compared to a larger and more ecologically impactful industrial production line.

The main consideration identified under the economic pillar is that traditional root tonic producers need to be able to bring in a reasonable level of income for a fairly-priced product over the long-term. The size of repurposed bottles is generally either 200 ml or more commonly 1 liter. Prices per one-liter bottle range from $1,500 to 2,000 JMD ($10.09 USD and $13.45 USD, respectively) in Kingston and $1,000 to 1,500 JMD ($6.72 USD and $10.09 USD, respectively) in rural areas at the time of research, with $1,000 JMD ($6.72 USD) for a one-liter bottle being the modal price for those producers who reported pricing. Artisanal producers who commented on batch volume generally indicated that a regular batch was around 5 gallons. Several of the producers interviewed said that they produced batches of root tonics only sporadically throughout the year, or to order for customers, and did not have a steady supply that was ready for sale.

While the goal is to ultimately have a cottage industry that operates in the formal sector, a road map will need to meet producers where they currently are in the informal sector. It will need to help them to use their own local knowledge paired with formalized training via public resources and industry tools that equip producers with what they need to enter the formal sector. There exist several economic barriers to traditional producers developing their own production lines, most significant of which is the lack of, or limited access to, resources such as business training and financial capital for producers operating outside of the formal sector. Other barriers include a low production capacity with a lengthy timeline, lack of IPR recognition, food safety concerns, a general underappreciation for traditional products, limited marketing and distribution options and strategies, and limited infrastructure.

A key consideration here is that root tonics are biodiversity-based products, which depend on the integrity of ecosystems. In order for a road map to help ensure that an increase in production of traditional root tonics will continue to support ecological sustainability, there should be a market differentiation between commercial and artisanal products. Major ecological hurdles that artisanal producers of traditional root tonics face include incomplete botanical knowledge of the plant species used, including about their diversity and ecology; lack of evidence-based knowledge on their health benefits; hard-to-reach locations of the wild plant species used; and a high potential for unsustainable harvesting methods with a significant increase in production.

Given the cultural importance of root tonics, a road map will need to ensure that the cottage industry development is culturally acceptable, both for traditional producers and for consumers. In order for this to be most effective, a deeper understanding of the benefits of root tonics as a cultural heritage product will need to be developed within the local market. Current barriers to continuing and growing root tonics' acceptance as a cultural product include the general misconception that it is only an aphrodisiac, a loss of traditional knowledge on the beverage's production as compared to past generations, and local stigmas against farming and bush remedies.

One of the central social considerations in developing a sustainable road map for a root tonics cottage industry is the empowerment of local communities. Currently, there exists a significant divide between locals and the “establishment,” and a general mistrust on the part of locals toward each other, government, formal institutions, and capitalistic ideas of development and progress. Systemic social barriers for root tonic producers include racism, classism, and gender inequality. These co-exist with more specific social barriers, such as a lack of mentorship, a lack of interest from the younger generation, and a lack of protection by any social classification such as “indigenous” that might bring with it the right to maintain traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions as intellectual property (IP). A road map should consider whether it is desirable to encourage collaboration among producers, and how this should be facilitated. Also, it is necessary to reflect on how an industry marketing strategy might boost the image of traditional root tonics to policy makers, educators, gastronomes, and other key influencers that could help to promote more widespread consumption.

During interviews, multiple artisanal producers commented on competition from other artisanal producers, as well as commercial products that are available nationwide. In Jamaica, we found at least eight commercial products that are being sold in supermarkets and labeled as roots, root tonics or tonic wine, namely “Baba Roots Herbal Drink,” “Put It Een Roots Tonic Wine,” “Pure Roots 100% Herbal Tonic,” “Pump It Up Roots Tonic Wine,” “Mandingo Roots Tonic Wine,” “Daniel's Roots Drink,” “Power Man Roots Drink” and “Hard Driver Roots Drink.” These commercial root tonics are packaged in bottles ranging from 148 ml to 1 liter, with the more common size being single-serving bottles of 148 ml. Single-serving commercial root tonic bottles are generally sold for $350 JMD ($2.35 USD) each, a price that is $1.36 JMD/ml (2.4 times) more expensive than the modal artisanal product with reported pricing in this study. However, none of these beverages are considered as authentic as those of the real “roots man” who sells a cultural product based on tradition. One person alluded to this during interviews, by stating that “commercial root tonics have lost their purpose [to help] cure sickness out of your body” (South Manchester-12, male, age 52).

The preparation and use of complex plant mixtures made with roots and bark in the Caribbean is not restricted to Jamaica, but has been reported in the scientific literature for other islands, for example in the Dominican Republic and Cuba, where they are popularly known as botellas and galones (Cano and Volpato, 2004; Vandebroek et al., 2010; van Andel et al., 2012). However, beyond the use of these beverages as aphrodisiacs and medicines, there is little scholarly information about their origin, perceived functions, and meanings. This may be due to a generalized lack of mixed methods approaches that combine ethnobotany with archival and/or oral history research. A study of pru, a fermented beverage characteristic to Eastern Cuba known there as “root champagne,” asked questions to pru producers, and merchants in herbal medicine, about the drink's production, consumption, origin and history that were similar to this study (Volpato and Godinez, 2004). However, the authors noted that the literature did not offer conclusive evidence about the drink's origin or its development over time. Interestingly, one of the plant components in pru was Smilax domingensis Willd., a species closely related to the two Smilax species found in Jamaican root tonics, and Cubans also considered pru a blood purifier (Volpato and Godinez, 2004).

The scientific literature, as well as advertisements and consumer views of commercial root tonics, have popularly described them as aphrodisiacs or bitter medicines (van Andel et al., 2012). However, this view may be too limited, since according to our study which was grounded in the informal economy, Jamaican root tonics are fermented beverages without a bitter taste profile that are consumed to sustain, strengthen, and treat the whole body, including the mind. In addition, oral history data associated with these beverages tells a complex story of survival and resistance that is deeply anchored in Jamaica's socio-cultural past and present. Dating back to the Transatlantic slave trade and gruesome forced labor on Caribbean plantations, Africans turned to nature and herbal medicines to fend off illness and to provide much needed energy, as well as physical and mental strength to survive. Today, according to their oral testimonies, rural Jamaican farmers, facing economic hardship and carrying out demanding manual labor without much help or technological tools (Sander and Vandebroek, 2016), continue to turn to root tonics to cope with hardship.

Importantly, root tonics have complex and layered metaphorical meanings that go beyond the notion of survival. There exist parallel narratives of resilience, and of returning to, believing in, and recognizing one's cultural roots, referring to the traditions from the past and the African continent. This paper follows the definition of resilience as “the capacity and dynamic process of adaptively overcoming stress and adversity while maintaining normal psychological and physical functioning” (Wu et al., 2013). In the case of root tonics, oral testimonies from Jamaicans described how using root tonics kept older generations alive, strong, and healthy during and after escaping from enslavement. Today, root tonics are still regarded as a product of self-reliance. Furthermore, root tonics are prepared with plant parts, including roots, for a beverage that is “rooted in tradition” (Sobo, 1993), and directly linked to cultural heritage and the ancestors. Since these tonics are considered an “all in one” by people for either obtaining or maintaining an optimal status of well-being, their use is embedded in a holistic framework of health. This framework also considers the human body as an element within the larger natural environment, characterized by a symbolic transfer of strength from plants to humans. Study participants described some of the plants used in root tonics as particularly resistant and difficult to harvest, and they believed that these plants subsequently transferred their quality of strength to the human body when they were prepared and ingested. In addition, consumption of root tonics also represented a double symbolism of using elements of nature (the earth) to sustain sexual nature and to guarantee human procreation (Sobo, 1993). Unraveling narratives such as these offer a much deeper insight into the cultural importance of plants for people than that offered simply by an ethnobotanical inventory or tallying of plant use-reports.

According to the oral history data presented here, the preparation and consumption of root tonics is primarily an African tradition, which is in agreement with the literature (Volpato and Godinez, 2004; van Andel et al., 2012). In the case of pru in Cuba, the authors postulated that the beverage was either “invented and developed locally,” or “a tradition brought to Cuba” in the eighteenth and nineteenth century by Haitians, Jamaicans, and Dominicans, who worked in coffee and sugarcane plantations in Eastern Cuba (Volpato and Godinez, 2004). However, these authors also considered an Amerindian origin of pru, based on testimonies from pru producers, literature reports that the indigenous population in the Caribbean made fermented drinks of pineapple, and the observation that the name “bejuco de indio” [Gouania lupuloides (L.) Urb.], a plant component of pru, refers to Amerindian people (Volpato and Godinez, 2004). In Jamaica, Higman (2008) described how during slavery (African) sugar workers on plantations were sometimes allowed to drink sugarcane juice or “cane liquor” fermented with Gouania lupuloides, which is called “chewstick” (or in earlier texts “chaw-stick”) there, to produce a “tolerable beer.”

Several participants in our study suggested a shared African-Amerindian origin of Jamaican root tonics, recalling cultural memories that both groups lived together in Jamaica in the past. The island's original Amerindian inhabitants, and later the Africans, have endured two waves of European colonization, first the Spanish (1509–1660), followed by the British (1655 until independence in 1962) (Picking et al., 2019). During the latter occupation, Anglo-Irish naturalist and physician Hans Sloane (1707-1725) wrote: “The Indians are not the natives of the island [of Jamaica], they being all destroy'd by the Spaniards, […] but are usually brought by surprise from the Musquitos [sic] or Florida, or such as were slaves to the Spaniards, and taken from them by the English”. He specified further that the Mosquitos (also known as the Miskitos) were “an indian people near the Provinces of Nicaragua, Honduras and Costa Rica”. However, others have pointed out that British writers who held deep Eurocentric views and hardly ventured beyond the coastal plantations and the edge of mountains were likely simply unaware of the existence of surviving Taino or other Amerindian peoples living in Jamaica's remote interior mountain areas (Craton, 1982; Fuller and Benn Torres, 2018).

The Amerindian influence on Jamaica's Traditional Knowledge Systems (TKS) has received very little attention thus far (see, for example, Payne-Jackson and Alleyne, 2004), and shared African-Amerindian ancestry has been a standing topic of debate and contention in Jamaica (Fuller and Benn Torres, 2018). On the other hand, one school of thought is that Maroon communities, who settled in the almost inaccessible mountains of the island's interior, where they successfully fought for independence from the British, were in touch or coexisted with surviving Taino Amerindians, who had also fled to these mountains since Spanish occupation (Payne-Jackson and Alleyne, 2004; Fuller and Benn Torres, 2018).

What remains unclear, however, is whether in the past Amerindians prepared root tonic beverages from the Smilax species that they collected and sold to European colonizers throughout the larger Caribbean region, including what is now Central and South America. Sloane wrote: “I was informed that Sarsaparilla is very frequent and cheap up Rio San Pedro in the Bay of Honduras where are several Indian towns. There is brought into Jamaica great quantities of sarsaparilla, by trade with the Bay of Honduras, New Spain and Peru. It grows in all these places on the banks of the rivers, and in moist ground. The Spaniards think it makes the water of those rivers, where it grows wholesome” (Sloane, 1707–1725). However, there does not seem to exist immediate confirmation that root tonics are an Amerindian tradition; instead these tonics seem to be associated with Afro-descendant communities, as is the case in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Surinam, and the Guianas. In French Guiana, Afro-Guyanese soak roots and bark in rum or vermouth (Guillaume Odonne, personal communication). Also, in Suriname (and Northwest Guyana), Smilax roots are soaked in alcohol in bottled mixtures together with bitter plants, or boiled in water and drunk as a tea (van Andel, 2000; van Andel and Ruysschaert, 2011). Although these bottled mixtures of wood and bark are known as “Black man's medicine,” the Amerindian population in Guyana collects the plant ingredients that are used by Afro-Guyanese people (Tinde van Andel, personal communication).

Literature records of Jamaican root tonics are scarce, and archival evidence about them seems non-existent. According to Sloane (1707–1725) “[The Africans] use very few decoctions of herbs, no distillations, nor infusions, but usually take the herbs in substance”. Thus, either root tonics were not yet prepared in the eighteenth century, or Sloane was not privy to their preparation and use. Sloane did mention several fermented beverages, which he described as “cool drinks” or “diet-drinks,” including “China drink” made with the two species of the genus Smilax that our study identified as important components of root tonics, the first a plant called China root (nowadays chainey root), Smilax canellifolia, and the second being sarsaparilla (Smilax ornata). Sloane prescribed these drinks as a regular treatment in his medical practice. He considered the Jamaican China root superior to the one Europeans imported from China, stating: “This is used for China roots, and yields a much deeper tincture than that of the East-Indies, whence I think it much better for the purposes to which it is employed, than that which is worm eaten coming from China, although [Willem] Piso [a Dutch physician and naturalist] seems to be of another mind” (Sloane, 1707-1725). Sloane added that the original China root became known by “Latins” in 1535, who learned it from China merchants, and that the Arabs knew it before the Europeans. Sarsaparilla, on the other hand, was obtained through trade with the Spanish colonies in the Americas, and was described in 1570 by a physician living in Mexico. Europeans thus knew of, and used, these two species since at least the sixteenth century. However, none of our study participants hinted at a possible European contribution to Jamaican root tonics. Charles Leslie, a Barbadian writer, described in 1753 that cool drinks were also consumed by Jamaica's African population, although he did not mention any Smilax species: “Their [referring to Africans and Creoles] common drink is water; but they prefer cool drink, a fermented liquor made with chaw-stick, lignumvitae [Guaiacum officinale L.], brown sugar, and water” (Higman, 2008).

In present-day Jamaica, study participants considered Rastafari to be the knowledge keepers of root tonics. This is not surprising, given that the Rastafari movement emphasizes “returning to the (cultural) roots.” Moreover, Rastafari celebrate “natural livity” (Dickerson, 2004). Root tonics embody a return to nature and natural solutions, since they are made with wild-harvested species collected far away from the potential negative influence of chemical pollutants, which Rastafari consider as one of the main causes of modern diseases (Sobo, 1993).

Based on interviews conducted in five of Jamaica's 14 parishes that represent different geographic areas of the island, our study showed that root tonics are drunk, prepared and sold across Jamaica, and that Jamaicans have detailed knowledge of their ingredients and processing. According to the oral history evidence, production and consumption of traditional root tonics reaffirm Jamaican cultural heritage and identity and celebrate local history. Resilience is an important aspect of Jamaican culture, and the concept of food as medicine is very popular, as is the desire to retain and build strength naturally (Sobo, 1993). The question that remains is how these beverages can be properly promoted as a cultural heritage product to a broader audience, including policy makers and gastronomes, and developed in a sustainable way for the benefit of local communities? Although in our interviews we did not specifically ask producers if they wanted to upgrade their production and sales of root tonics, our study found that the majority of interview participants (62%) were already selling (and preparing) these tonics on their own, without receiving any form of assistance or feedback. The development of a road map for a root tonics cottage industry thus presented itself as a logical applied extension of our ethnobotanical research, in order to provide recommendations to those producers who might be interested in upgrading their production in a sustainable way, at present or in the future. Given that artisanal root tonics reportedly can be enjoyed in moderation for their alleged health benefits by children and youth as well, pursuing a more formal production through a sustainable cottage industry could be an effective way to ensure that future generations retain access to this traditional knowledge while generating extra income.

The current informality of artisanal production is not unique to root tonics, but is common in Jamaica, where it was estimated in 2006 that the economic activities of the informal sector represented 43 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) (MICAF, 2018). The root tonic producers in this study would most likely be categorized as micro enterprises, which the Jamaican government defines as an enterprise with total annual sales falling under $15 million JMD ($100,847 USD) and less than five employees. The MSME sector accounts for 80 percent of jobs within the Jamaican economy and at the time of research was considered to be a priority within the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Agriculture and Fisheries (MICAF). However, many of the resources made available for MSMEs are only available to those businesses that are formally registered. The MSME & Entrepreneurship Policy of Jamaica incentivizes MSMEs to formalize their businesses in order to receive government and private sector support (MICAF, 2018).

It is important that any road map for a sustainable cottage industry of root tonic producers emphasizes that power and ownership need to remain in the hands of the artisanal producers, given the many barriers these producers face, and the general mistrust between Jamaican people and formal institutions in the public and private sectors (Sobo, 1993). It will be important to provide tools, resources and support to these producers, while acknowledging that the knowledge and expertise belongs fully to them. Based on this premise, the initial road map we developed (Figure 7) should be viewed as a suggested starting point for a cottage industry that has not yet been established, but in which the waypoints, and therefore the map itself, will inevitably change as the industry develops and the socio-economic situation in Jamaica changes over time.

Figure 7. Road map infographic for development of a sustainable root tonics cottage industry for artisanal producers. BSJ, Bureau of Standards Jamaica.

A recent study showed that the impact of soft skills training for entrepreneurs in Jamaica was somewhat positive over only a 3 month term, and only for men (Ubfal et al., 2020). However, the study suggested that business training for small enterprises may be more effective if it is specific to the business, encourages a proactive mindset, has hands-on training, focuses on personal initiative, includes SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-based) goal setting training, addresses innovation, efficiency, and resilience, and is followed up by mentorship. Training of this type should be provided by the public sector for businesses operating both formally and informally so that the cost is approachable to entrepreneurs at all levels.

In order to increase production, each producer will need to first complete a cost-benefit analysis, i.e., they will need to assess their current levels of production in terms of revenues and other benefits, direct expenses and other costs, production quantities and timelines. Doing so will allow for a known starting point from which producers can identify goals and track progress. Once this analysis has been completed, a simplified strategic plan that addresses the strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities of the business with immediately actionable steps can be developed.

It is important that the price of artisanal products reflects the time it took to produce the product, as well as the higher than average number of plant species ingredients used as compared to the industrial products on the market. Comparatively, the mean number of plant ingredients for artisanal products was 15, as compared to 9 for the sample commercial products. Given that the commercial products are currently priced higher than artisanal ones, there is room for artisanal producers to increase their price to some degree.

For artisanal production, glass bottles of varying sizes are repurposed from a prior commercial product, usually alcohol-based, and are filled with the producer's root tonic. The original alcohol's label is either left on the bottle, or removed and not replaced with a new label for the root tonic. Jamaicans tend not to purchase food products unless they are confident of the safety of the food. Consumer confidence in the Jamaican market is something that can be established via purchasing from someone within your social network, and/or purchasing products from established businesses that have clear, detailed product information, including batch code, full list of ingredients, company information, and best by or expiration date.

Since many root tonic producers operate within the informal sector, they do not use the labeling requirements set out by the Bureau of Standards Jamaica (BSJ). As a prerequisite toward expanding their distribution network, producers should strive to create a label for their products that indicates information about the producer, a list of main or common ingredients, how the product should be used, and how to store and consume the product. Producers should also consider their background story: What makes their root tonic special and why do they brew root tonics? Adding a label with these details will increase competitiveness by allowing producers to tell their stories without being physically present at the point of sale, which in turn will allow producers to expand their distribution channels.

Once a producer is ready to enter the formal sector, they will need to ensure that their label is compliant with the requirements indicated by the BSJ. A finished product from a formalized business that abides by food safety regulations can attract a higher price due to the consumer confidence that is gained when they have awareness of product ingredients and that safety protocols are being adhered to.

Distribution in Jamaica is difficult for any producer who lacks access to a vehicle, funding for transportation costs, and/or road infrastructures surrounding their production location. Even for those who do have sufficient access to resources and infrastructure, transport to urban markets from rural regions can be costly and time-consuming, with no guarantee that daily sales will cover costs.

The Jamaican government is encouraging MSMEs, whether they operate in the formal or informal sector, to digitize their business. As such, MICAF is offering a free resource to MSMEs so they can create a website for themselves (Kolau, 2019). MICAF is also encouraging linkages between the tourism and agricultural sectors, and has partnered with the Ministry of Tourism to create a digital Agro-trading platform, called “ALEX,” that connects hundreds of small-scale farmers to consumers (Tourism Enhancement Fund, 2020). However, the ALEX platform is intended for farmers selling fresh produce rather than those working in the agro-processing sector. Platforms such as ALEX would be useful to artisanal root tonic producers, though it should be noted that many Jamaicans have a smartphone but do not subscribe to a data plan, so internet access is not always consistent or economically within reach.

In the short term, root tonic producers can develop their distribution channels by utilizing their community networks to find roadside and market vendors and community shopkeepers who would be willing to sell their root tonics. Products could be transported via handcart, bicycle, or motorcycle as funds allow. As sales increase, production can be scaled up by increasing the number of 5-gallon pots to increase batch size.

There is currently a misconception held by the Jamaican public that root tonics are only an aphrodisiac, for men, and there is a general lack of public awareness of the myriad health benefits of the product. Public campaigning is generally effective in Jamaica, since the population is accustomed to seeing multimedia campaigns launched by public and private sector organizations. If artisanal producers in the root tonics cottage industry could band together to create a public education campaign, it could significantly grow their potential market. Since there are limited funds available, social media platforms would be the most cost-effective tool to spread awareness. In order to differentiate the traditionally produced root tonics from industrial ones, the development and use of a visual aid such as a logo or certification mark would be helpful.

Producers can also use cultural and agricultural events to circulate information about traditional root tonics. Annual events such as the Denbigh Agricultural, Industrial and Food Show would allow producers to set up stalls to allow the public to sample, purchase, and learn about their traditional products.

Business cooperatives are not readily accepted in Jamaica, but the Government of Jamaica has identified the need for business clusters to enhance business development, competition, productivity, knowledge-sharing, marketing, and networking (MICAF, 2018). The public and private sectors will need to be creative in order to foster the spirit of collaboration, and an important first step would be to hear directly from current producers about the conditions in which collaboration would work for them, since not everyone will likely be comfortable sharing knowledge about their recipes, or process of harvesting and production. Producers will be better off if they build connections amongst themselves and with key people in the public and private sectors who can assist with advocating for recognition of root tonics as a biocultural heritage product, but this cannot be established without prior dialogue and consensus-building. Having some kind of cooperative between artisanal producers may also make it easier for these producers to achieve recognition for their traditional knowledge of root tonic production as IP. Having this IP recognition and protection would help to increase awareness of root tonics as a cultural heritage product, encourage interest in production from newcomers, clearly demarcate artisanal and commercial products, and enhance the ability for an artisanal industry to develop in an economically sustainable manner.

The Jamaican MICAF has already published an infographic road map consisting of four steps to assist potential small business owners in establishing a formal business (MICAF, 2019). The first step is to develop a business plan and obtain support from the Jamaica Business Development Corporation (JBDC). The next step is to register the business at the Companies Office of Jamaica (COJ). The third step involves receiving assistance from the Jamaica Intellectual Property Office (JIPO), and the fourth and final step is to meet business standards (e.g., for labeling), with help from National Compliance Regulatory Authority (NCRA) and Bureau of Standards Jamaica (BSJ). Once a root tonic business has been formalized, additional resources will become available to the owner for business development and support, depending on various factors, such as the type of enterprise, creditworthiness, scale of operation, and length of time in business. The cost and requirements to access these resources are varied. For example, the Development Bank of Jamaica (DBJ) offers a Voucher for Technical Assistance (VTA) program to assist formalized MSMEs who have not received a voucher within the prior 2 years in closing management gaps by strengthening managerial and administrative abilities with the aim of improving creditworthiness. The DBJ subsidizes 70% of the value of the voucher, and the business owner pays the balance (DBJ, 2020).

If the cottage industry for traditional root tonics will grow in size, it will be imperative for producers to focus on conservation of plant species and the habitats where these plants grow. If established producers would be willing, they can teach newer producers to harvest in ways that ensure these species grow back, for example by hosting periodic field or “in-the-bush” workshops, taking on apprentices to whom they can transmit traditional knowledge directly over a period of time, and/or by creating reference materials for those getting their root tonic production lines off the ground. Due to the importance that newcomers to the industry understand the need for sustainable harvesting practices, apprenticeship training over a sustained period will likely be most effective in promoting the continued ecological sustainability of the cottage industry.

Currently, the majority of plant species used in traditional root tonic production are wild-harvested. Internationally, the majority of medicinal and aromatic plant species (MAPs) and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) also continue to be wild-harvested. Standards for wildcrafting MAPs and NTFPs are included within a number of existing organic management and certification programs as a means to improve natural resource management and generate higher incomes for communities. The standards for wild collected, rather than cultivated, products are different, focusing on collection activities and the way they are carried out. The aim is to ensure that the collection methods are sustainable and do not damage the ecosystem and natural yield of the collected products (ITC, 2007).

Examples of organic management and certification programs with provisions for wildcrafted products include the National Organic Program (NOP), overseen by the U.S. (USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture), 2020) and Ecocert, one of the largest international organic certification organizations (Ecocert, 2013).

Non-organic initiatives also address wild collection practices. The World Health Organization (WHO) published a set of guidelines on good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for medicinal plants in 2003 (WHO, 2003). This was followed by the establishment of the International Standard for Sustainable Wild Collection of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (ISSC-MAP) by the Wildlife Trade Monitoring Network (TRAFFIC), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), World Conservation Union (IUCN), and the Species Survival Commission (SSC) (MPSG, 2007). Implementation of the ecological elements of ISSC-MAP were identified as a priority in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (MPSG, 2007).

In 2008 the FairWild Foundation was established to facilitate the global implementation of the ISSC-MAP standard and to ensure that wildcrafted products are produced in a socially and ecologically sound manner (FairWild, 2020).

FairWild certification requires the active participation of stakeholder groups, including local communities, businesses, academic institutions, non-profits, and government institutions. FairWild represents one of the more rigorous of a number of voluntary sustainability standards (VSS), supporting sustainable production and trade, biodiversity conservation, and resilient rural economies. Ultimately FairWild aims to reward communities who wildcraft for functioning as stewards of sensitive ecosystems (Yearsley, 2019). FairWild certification represents, perhaps, the best fit for the Jamaican root tonics industry but would, most likely, require academic grants-private sector funding to offset the inevitable cost barriers to its successful implementation.

In addition to sustainable harvesting, producers, in collaboration with scientists, can experiment with the cultivation of these wild plant species in order to encourage their growth in the producing region. It will also be crucial for producers to engage with scientists to learn more about the conservation threats to the plant ingredients used in root tonics and their natural habitats, in order to better understand the specific ways in which they can promote ecological sustainability. The Caribbean islands represent a global biodiversity hotspot with high priority for conservation, since the region has a high degree of endemic plants and animals (occurring nowhere else in the world) and their habitats face significant environmental threats from anthropogenic activities such as agricultural expansion of high-value commercial crops, wood extraction, mining, and infrastructure development. Jamaica's level of plant endemism (34%) ranks third in the Caribbean islands, after Cuba (53%) and Hispaniola (44%) (Acevedo-Rodríguez and Strong, 2008). Forest cover change has been relatively well-documented in Jamaica, including in protected areas, and the island experienced net deforestation during 2001–2010 (Newman et al., 2018), although estimates of annual deforestation rates have been highly variable. A comparative regional paper indicated Jamaica as one of two countries with the greatest area of woody vegetation loss (minus 299 km2) between 2001 and 2010 among all countries in the Caribbean (Aide et al., 2013).

In order to refine the road map and continue with the development of a cottage industry, additional research can include market surveys of consumer trends, population surveys to better understand the perceived health benefits of root tonics, and laboratory studies to develop an evidence base about these health claims. In addition, further comparative research is needed into current production methods and tools used by traditional producers, as well as the production cost of root tonics, and the potential cost of more efficient tools, better packaging and labeling, transportation, and distribution. Sensory analysis and taste profile comparisons between commercial root tonics and traditional (artisanal) ones will be useful to differentiate better between these two types of products. Finally, marketing campaigns can be designed to explain the evidence-based health benefits and cultural heritage value of traditional root tonics to Jamaicans living on the island and in the diaspora.

Root tonics are fermented beverages, not bitters, that are consumed, prepared, and sold across Jamaica. The documentation of the oral histories of these tonics shows that there exists a wealth of traditional knowledge related to their use that conceptualizes and situates the functioning and well-being of the human body within the island's natural environment and history. This data contributes much-needed insights into the intricate and layered sociocultural meanings and origin of these beverages, information that has hereto remained undocumented in ethnobotany studies, which often tend to myopically focus on plant diversity and plant uses. Our study has revealed important new perspectives of root tonics beyond their aphrodisiac qualities, as food-medicines that have supported, and continue to support, the holistic health and mind-body equilibrium of Jamaica's Afro-descendant and wider population in the past and present. The strength-building qualities of these root tonics are embedded in a narrative of survival, resistance, and resilience that dates back to the history of Transatlantic slavery. Root tonics are thus rooted in tradition, and knowledge about these beverages has been passed along by African ancestors, Maroons, and others with close access to nature who searched, and continue to search, for plants that could transfer specific therapeutic qualities such as strength to the human body in times of need. Root tonics also embody a double symbolism of using elements of nature (the earth) to sustain sexual nature. The natural lifestyle that is at the core of the consumption of Jamaican root tonics is also at the heart of the Rastafari movement and religion, and it is therefore not surprising that Rastafari, who celebrate a return to the (cultural) roots of Jamaicans, are seen as the current knowledge holders. Future studies can examine archival ethnobotany records, to trace traditional knowledge about the use of individual plant species in root tonics over time, to learn about the health conditions these species were used for in the past, and to understand which cultural groups knew and used these plants. Untangling this complexity will help to better understand and promote Jamaica's rich biocultural heritage.

Currently, most root tonics are prepared at home and sold in the informal economy. Using the oral history data in our study as a guide, we identified key considerations, barriers, and action points for the development of a sustainable cottage industry for these traditional producers. We then designed a roadmap based on four steps: Growing production, growing alliances, transitioning into the formal economy, and safeguarding ecological sustainability. The main premise of this roadmap is that a cottage industry for Jamaican root tonics should put the concerns and benefits of small-scale, artisanal producers at the center, and recognize and honor their IPR.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The University of The West Indies, Mona. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the relevant individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

IV designed the project, with input from DP. IV and DP applied for permits, coordinated ethnobotanical fieldwork, and transcribed the interviews. IV, DP, JW, MG, DS, UG, and DL recruited and/or interviewed study participants. JT conducted research into the potential for development of a sustainable Jamaican root tonics cottage industry and created Figures 6, 7. IV analyzed the data. IV, JT, and DP wrote the paper and received feedback from co-authors. JT and DP provided editorial assistance to the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The research in this study was funded by grant #HJ-161R-17 from the National Geographic Society to IV. The Caribbean Program at The New York Botanical Garden has received World of Difference Grants from the Cigna Foundation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank everyone who participated in the interviews. The traditional knowledge documented in this study belongs to the intellectual property of Jamaican study participants, and other traditional knowledge holders across Jamaica, and should not be used for the development of any product without their prior informed consent and involvement in benefit sharing agreements. The map of the study locations was created by Elizabeth Gjieli, GIS Laboratory Manager, The New York Botanical Garden.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2021.640171/full#supplementary-material

Acevedo-Rodríguez, P., and Strong, M. T. (2008). Floristic richness and affinities in the West Indies. Bot. Rev. 74, 5–36. doi: 10.1007/s12229-008-9000-1

Aide, T. M., Clark, M. L., Grau, H. R., Lopez-Carr, D., Levy, M. A., Redo, D., et al. (2013). Deforestation and reforestation of Latin America and the Caribbean (2001-2010). Biotropica 45, 262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2012.00908.x

Barros dos Passos, M. M., Cruz Albino, R., Feitoza-Silva, M., and Oliveira, D. R. (2018). A disseminação cultural das garrafadas no Brasil: um paralelo entre medicina popular e legislação sanitaria [The cultural dissemination of garrafadas in Brazil: a parallel between popular medicine and sanitary legislation]. Saúde Debate 42:116. doi: 10.1590/0103-1104201811620

Cano, J. H., and Volpato, G. (2004). Herbal mixtures in the traditional medicine of Eastern Cuba. J. Ethnopharmacol. 90, 293–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.10.012

Craton, M. (1982). Testing the Chains. Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

DBJ (Development Bank of Jamaica) (2020). How it Works. Available online at: https://www.dbjvoucher.com/how-it-works (accessed July 29, 2020).

Dickerson, M. G. (2004). I-tal foodways: nourishing Rastafarian bodies. [LSU Master's theses], 111. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/111 (accessed February 7, 2021).

Ecocert (2013). Guideline Number 25: Regulation on Wild Plant Harvesting According to Ecocert Organic Standard (EOS). Aurangabad: Ecocert. Available online at: http://www.ecocert.in/newdocs/organic-farming/Wild%20collection%20(EC).pdf (accessed November 26, 2020).

FairWild (2020). Our Story. Available online at: https://www.fairwild.org/our-story (accessed November 26, 2020).

Farsani, N. T., Coelho, C., and Costa, C. (2012). Geotourism and geoparks as gateways to socio-cultural sustainability in Qeshm rural areas, Iran. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 17, 30–48. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2011.610145

Fuller, H., and Benn Torres, J. (2018). Investigating the “Taino” ancestry of the Jamaican Maroons: a new genetic (DNA), historical, and multidisciplinary analysis and case study of the Accompong Town Maroons. Can. J. Latin Am. Caribbean Stud. 43, 47–78. doi: 10.1080/08263663.2018.1426227

Gros-Balthazard, M., Battesti, V., Ivorra, S., Paradis, L., Aberlenc, F., Zango, O., et al. (2020). On the necessity of combining ethnobotany and genetics to assess agrobiodiversity and its evolution in crops: a case study on date palms (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in Siwa Oasis, Egypt. Evol. Appl. 13:1818. doi: 10.1111/eva.12930

Higman, B. W. (2008). Jamaican Food: History, Biology, Culture. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press.

Hong, L., Zhuo, J., Lei, Q., Zhou, J., Ahmed, S., Wang, C., et al. (2015). Ethnobotany of wild plants used for starting fermented beverages in Shui communities of southwest China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11:42. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0028-0

ITC (International Trade Centre) (2007). Overview of World Production and Marketing of Organic Wild Collected Products. International Trade Centre, Geneva. Available online at: https://www.intracen.org/Overview-of-World-Production-and-Marketing-of-Organic-Wild-Collected-Products/ (accessed November 26, 2020).

Keahey, J. (2019). Sustainable heritage development in the South African Cederberg. Geoforum 104, 36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.06.006

Kolau (2019). Jamaica's MSME Digitalization 100% Free. Available online at: https://www.kolau.com/jamaica (accessed August 21, 2020).

Kumari, A., Pandey, A., Ann, A., Raj, A., Gupta, A., Chauhan, A., et al. (2015). “Indigenous alcoholic beverages of South Asia,” in Indigenous Fermented Foods of South Asia, ed V. K. Joshi (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 501–596.

MICAF (Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Agriculture and Fisheries). (2019). So You Want to Own Your Own Business? Available online at: https://www.micaf.gov.jm/content/msme (accessed July 31, 2020).