- 1Observatory of Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security, National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

- 2Faculty of Medicine, Nutrition and Dietetics School, National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

- 3Faculty of Nutrition and Dietetics, University CES, Medellín, Colombia

- 4Global Nutrition Professionals Consulting, Miami, Colombia

Venezuela has had the largest migration in recent history, with 4.8 million people displaced due to sociopolitical, economic, electrical blackouts, and health crises. Nine out of 10 migrants are facing food insecurity during the COVID19 pandemic. Colombia has received the largest number of Venezuelans migrants, counting officially 1,764,883 to date. This study aims to analyze the changes in the migration process regarding the availability, access, and food consumption of Venezuelan migrants in Bogotá, before and after their arrival. This study uses a naturalistic approach, with a convenience sample (n = 15 families) who participated in in-depth semi-structured interviews about their experiences related to diet and nutrition, and the migratory process. Information was recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using grounded theory. Findings reflect that Venezuelan migrants leave the country due to severe lack of access to food which in turn affects the supply, acquisition, consumption, and nutritional status: “The main reason I left Venezuela was that I couldn't get groceries like milk to feed my granddaughter. When that happened, I couldn't stand it anymore.” After arrival in Colombia, dimensions of food and nutrition security, such as availability, physical and economic access, and consumption improved. However, families are still struggling to acquire basic food items. Households have access to a culturally adequate diet, but with insufficient nutritional quality, as noted by one participant: “The biggest difference is that in Venezuela you can't get the groceries to feed your whole family with the salary that you get. Here in Bogota, you can buy cheap food, to feed the whole family.” After their arrival, migrants still face difficulties that include legal issues, finding a place to stay, employment, access to high-quality foods, and xenophobia. They have regained the freedom to choose the food they want to buy in a dignified and socially accepted way; two elements that were no longer possible in Venezuela.

Introduction

In the last 25 years, the international migrant population has been growing, currently representing 3.5% of the world population [Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM), 2019]. International migration is one of the most important social, political, economic, and cultural phenomena of the twenty-first century caused by the precarious living conditions in some countries. Currently in Venezuela, because of food shortages, illegal food marketing, unauthorized distribution networks, and high food prices, the usual diet composition was altered (decrease in the number of daily meals and portions) (Landaeta-Jimenez et al., 2015). Venezuelan migration has become the largest migratory movement in the recent history of the Latin America region, and the second in the world after Syria (ACNUR, 2020). Colombia has received the largest number of Venezuelans migrants, where 1,764,883 Venezuelan migrants are now living; of whom 19.6% arrived in Bogota. The immigration of Venezuelan citizens has increased by 110% since 2017 (Migración Colombia, 2020), as a result of the difficulties that migrants face to access, acquire, and eat basic food (ACNUR, 2020). However, this migration constantly fluctuates, as witnessed during the pandemic, during which some Venezuelans in Colombia wanted to return home (Migración Colombia, 2020).

The constant food shortages and lack of food access are violations of the Right to Food and Nutrition Security (Sen, 2002). According to the Food Agriculture Organization (FAO), Food and Nutrition Security is achieved when: “all people have food availability and access, in a timely, dignified, and permanent manner. All people have access to safe water in sufficient and adequate quantity and quality, to ensure its consumption and biological use. The goal is to achieve an optimal state of nutrition, health, and well-being that contributes to their human development and allows them to be happy” (OBSSAN, 2016).

Violations of human rights occur in all stages of migration: from preparation, to departure, transportation, borders, and the arrival at the place of destination (Tizón, 1989). Global migration is related to multiple issues, including lack of food (Aguilar et al., 2015; Carmona et al., 2017). There is a growing interest in including the human rights perspective in migration studies. Although international migration is seen as a social problem, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean affirms that “migration is the exercise of the individual right recognized in article 13 of the universal declaration of human rights to seek opportunities abroad, which gives rise to intense transnational activity that enriches experiences and favors cultural exchange” (CEPAL, 2008). However, the rapid increase in migration has made visible that migrant populations face a constant lack of protection, far removed from the universality of human rights which prevents them from being recognized by and enjoying the status of subjects of law (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM), 2019).

Venezuela appeared as the world's fourth-largest food crisis with 9.3 million people acutely food insecure, seven million moderately food-insecure, and 2.3 million severely food-insecure, representing 92% of the total population (FSIN, 2020). Data from the National Survey of Living Conditions reveal that the Venezuelan population has been experiencing food insecurity since 2012, which increased to 93% during the pandemic (ENCOVI, 2020). There is a constant shortage of basics foods like pasteurized powdered and liquid milk, rice, oil, sardines, sugar, beans, chicken, eggs, cornmeal, and beef; as well as shortages of essentials services such as water and electricity. The availability of sources of animal protein has continuously declined, followed by vegetables, sugar, milk, tuna, sardines, cheese, and eggs.

The Venezuelan diet is low- quantity and quality due to insufficient consumption of animal protein, dairy products, and fruits and vegetables; a consequence of accessible or affordable foods for purchase are mainly highly caloric (flours, cereals, and fat; Landaeta-Jimenez et al., 2015; ENCOVI, 2020). The purchase of food is directly proportional to availability and access and this is a very complex situation in Venezuela with an increase in price monthly of 51% and an inflation rate of 506% (CARITAS Venezuela, 2020). Furthermore, the child population is seriously affected by the limited variety of foods, which do not provide essential nutrients (proteins, iron, folic acid, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12).14.4% of children under 5 years of age are wasted and 29% are stunted (CARITAS Venezuela, 2020). In mid-2018, a dozen eggs cost the equivalent of 2 weeks pay in a minimum wage job (Doocy et al., 2019). Since 2016, social food programs are limited to those agreed with the government (the main is named CLAP: Local supply and production committees) and provides a food box with nonperishable foods which are limited and unreliable (Doocy et al., 2019; Aponte, 2020). In 2019, this subsidized imported food box, low-quality weighed 22 pounds and reached 39% of the population (Efecto Cocuyo, 2019; ENCOVI, 2020).

In Colombia, Venezuelan migrants found a place to overcome the difficulties they faced in their country (Migración Colombia, 2019). They expect an improvement in their availability, access, and consumption of adequate food, as well as a better quality of life. However, Colombia is also facing the same problems because 54.2% of Colombian families are also living with food insecurity (ENSIN, 2015), had an inflation of 3.8% in 2019 (DANE, 2019), and received migrants from Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil, and United States (Expansión, 2019).

This study aims to analyze the changes caused by migration in the availability, access, and consumption of food in Venezuelan households settled in Bogotá and to determine whether their food and nutritional security status improved after their arrival.

Materials and Methods

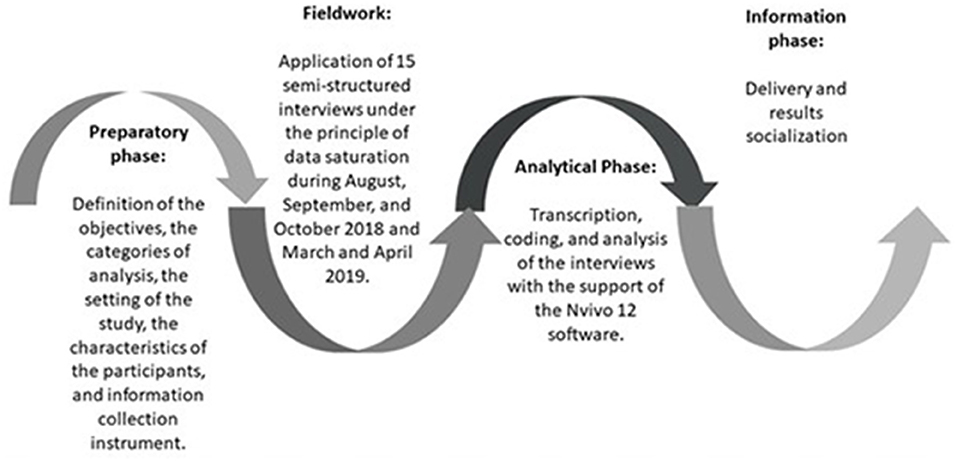

This research was developed with a naturalistic qualitative approach, to explore migration movements, causes, and changes. The study was undertaken in four phases: preparatory, fieldwork, analysis, and informative (Figure 1). In qualitative research, there are no established criteria for number of participants. However, the principle of data saturation was used, such that data collection was finished when new information was no longer obtained (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Salamanca and Martín-Crespo, 2007). In this study, saturation of data occurred after 15 subjects were interviewed.

Setting and Subjects Studied

Subjects were interviewed in three different settings: San Cristóbal, Tunjuelito, and Rafael Uribe, towns distinguished as low-economic stratum, in Bogotá DC. These municipalities were the arrival locations of a significant number of Venezuelan migrant families. The families were linked to the Colombian social childcare program and selected on suggestion of the program coordinator.

Purposeful sampling, a technique used in qualitative research for identification and selection of information-rich cases, was used. The strategy of snowball was implemented to select cases of interest from people who know people that generally have similar characteristics and who, in turn, also know people with similar characteristics (Patton, 2002; Palinkas et al., 2015). Using this sampling technique, data saturation occurred at a sample size of 15 families, which means that no new information emerged from the additional of new participants. Four families lived in San Cristóbal, six in Tunjuelito, and five families in Rafael Uribe, all located in Bogotá DC. All the families invited to take part in the research agreed to participate.

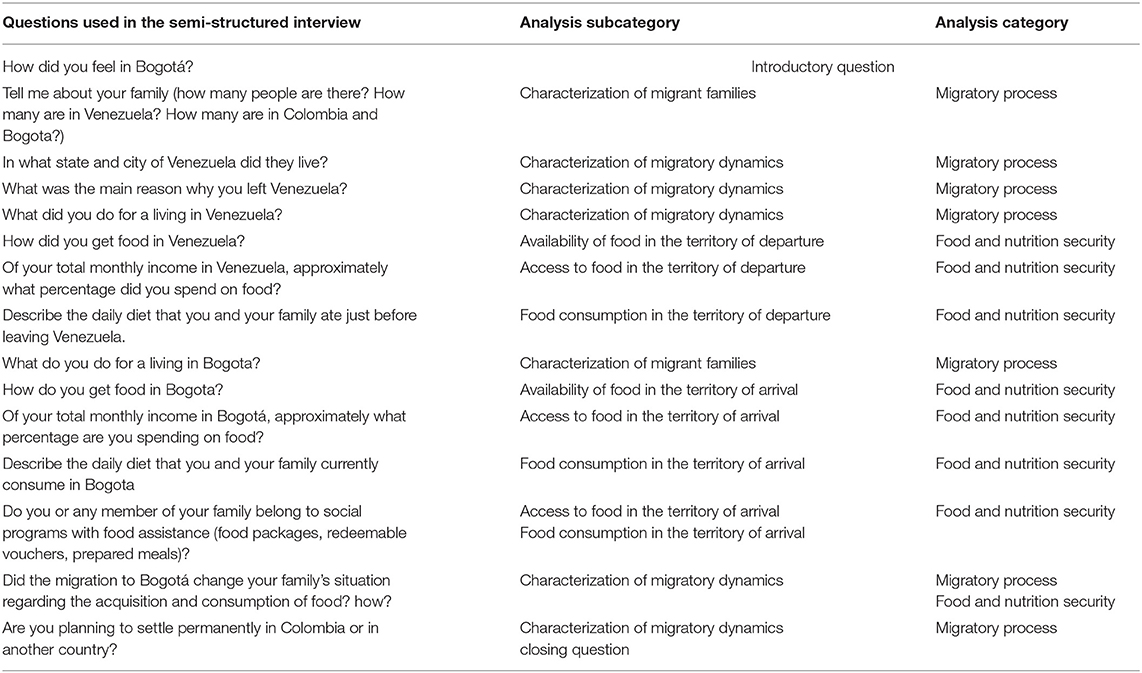

The families participating in the study had to meet three inclusion criteria: 1. Not having family ties in Colombia; 2. At least 3 months of living in Bogota by the time the study took place; and 3. At least one member of the family receiving child food assistance. The food program provides beneficiary children with food during weekdays, three times a day (morning snack, lunch, and afternoon snack). The rationale of including families with children participating in this program was to be able to draw comparisons between the access to food available at home and food available through the program, and how this extra food benefitted the rest of the family (Table 1).

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted as a qualitative research instrument. The data collected includes characteristics of families, information related to the migratory process, and the availability, access, and food consumption in the territory of departure (Venezuela) and arrival (Bogotá). A field test of the semi-structured interview to determine the accuracy and relevance of the questions was conducted. The semi-structured list of questions was tested in three migrant families to help refine and improve the interview scripts and questions. This procedure produced a final instrument of 15 questions, helped determine the length of time to conduct the interviews, and how to best engage the participants. These field-test interviews were not part of the analysis.

Data collection took place from August to October 2018, and March and April 2019. A first approach was made to the head of the family or adult with knowledge of the migration process and changes in the patterns of the family food consumption. Informed consent was obtained from participants who were notified about the study objectives and potential risks of participating in this study.

Most of the interviews were conducted in the migrant families' homes, which revealed additional aspects to those found in the conversations. Interviews were conducted by the principal investigator, who is a nutritionist trained through qualitative courses at the UNAL University and supervised by the second and third author who hold Ph.D. degrees, are nutritionists and educators and have more than 15 years of experience in the area of food security and qualitative research.

Ethics Statement

This research has approval concept No. 009-123-18 of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the National University of Colombia, Bogotá and according to Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Colombia which corresponds to risk-free research (Ministerio de Salud, 1993). Subjects approved and signed their consent to participate in the study. All processes were confidential, and the participants could drop out of the research at any time.

Data Analysis

The 15 interviews were transcribed, coded, categorized, and analyzed using the qualitative software Nvivo 12. The coding permitted disaggregation and aggregation of the data to construct emerging themes such as changes in food consumption, and the intention of returning to the origin country. The coding process was done by the first author in advance and checked by the rest of the authors. After interviews were completed, new information not originally hypothesized emerged from the data and was included, such as nostalgia to return home. The emerging themes were integrated in a logical way that will support the understanding of why Venezuelans migrate and changes that occur before and after migration, using as a basis the dimensions of food security and availability, access, and food consumption. Analysis of the data was iterative and integrated until saturation of the theory was reached. Two specialists (first and third author) in nutrition and food security read and captured the emerging themes and analyzed the data.

Results

Household Characteristics

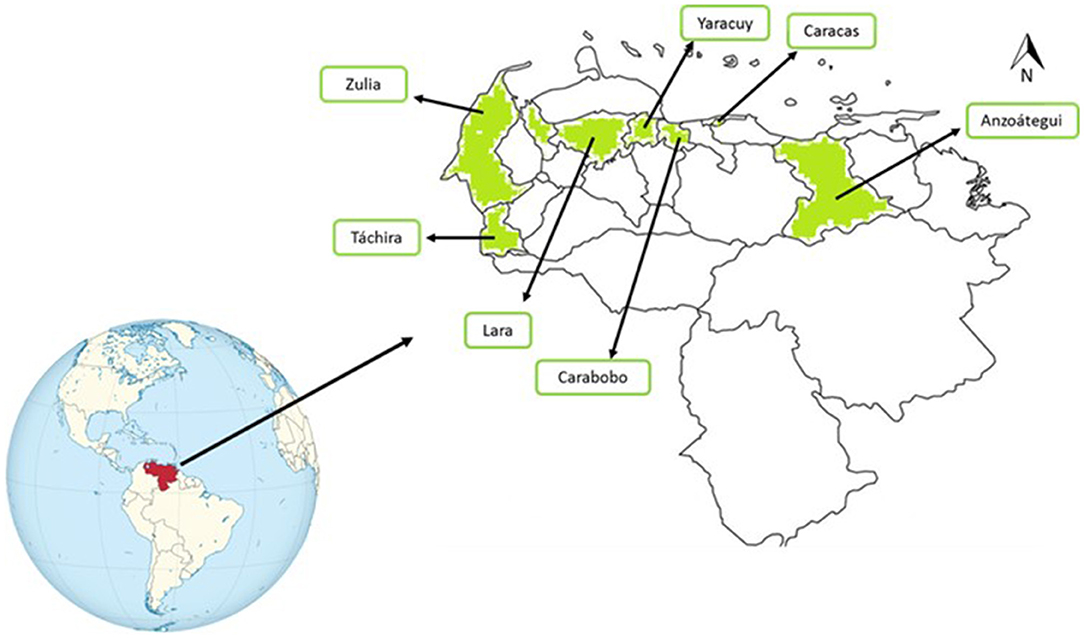

The 15 migrant families interviewed arrived to Colombia from various states of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Caracas DC: 4, Zulia: 3, Lara: 2, Táchira: 2, Carabobo: 2, Yaracuy: 1 and Anzoátegui: 1 (Figure 2). Thirteen families had a different household composition and two families had a similar composition in comparison to their households in Venezuela. In their country of origin, they were nuclear or composite families (mother, father, and children) and extended (mother, father, cousins, grandparents, uncles, etc.), but this changed with migration. The migrant family often suffered a separation from mothers, fathers, grandparents, children, and partners. Some family members stayed in Venezuela due to the impossibility of obtaining a passport to enter Colombia legally or to take care of the goods and belongings they have in their country. Others stayed in regions of Colombia that did not allow them to be reunited as a family because they found jobs such as domestic work or as a waiter.

Five out of 15 families had a woman as head of the household, with a male presence at home. Eight families consider the headship to be shared between females and males, and in two families there is no female presence, therefore, the head of household is a male. In Venezuela, the heads of households worked as a trader, baker, butcher, driver, messenger, stylist, manicurist, dealer, cashier, and cleaning personnel. Of the 11 families that had the Colombian special residence permit (named PEP), only one family had a formal job in Bogotá. The other members of the households worked in informal jobs like selling food and beverages on the street, and one family was unemployed. These informal jobs were performed between two and five times a week and the payment range was from 20,000 to 30,000 COP daily (5–7 US dollars).

Causes of migration to Bogotá, Colombia

All the participating Families expressed that the main reason for leaving Venezuela was the impossibility of obtaining food and/or acquiring it in the quantities that their families needed. The families stated that they chose Bogota because they found work and better living conditions in the city.

The decisive point to migrate was when they could no longer purchase food even for their children, after long facing food shortages and high prices. This limited adult food consumption as well. One participant stated:

“The main reason I left Venezuela was that I couldn't get groceries like milk to feed my granddaughter, and when that happened, I couldn't stand it anymore” (Female, 50 years old, Tunjuelito, Bogotá).

Of the 15 families interviewed, 12 expressed their hopes to return to Venezuela no matter how long it takes and when the social and economic situation of their origin country changes favorably. Two families hope to settle in other countries and one family expressed their intention to stay in Colombia with no intent to return to Venezuela.

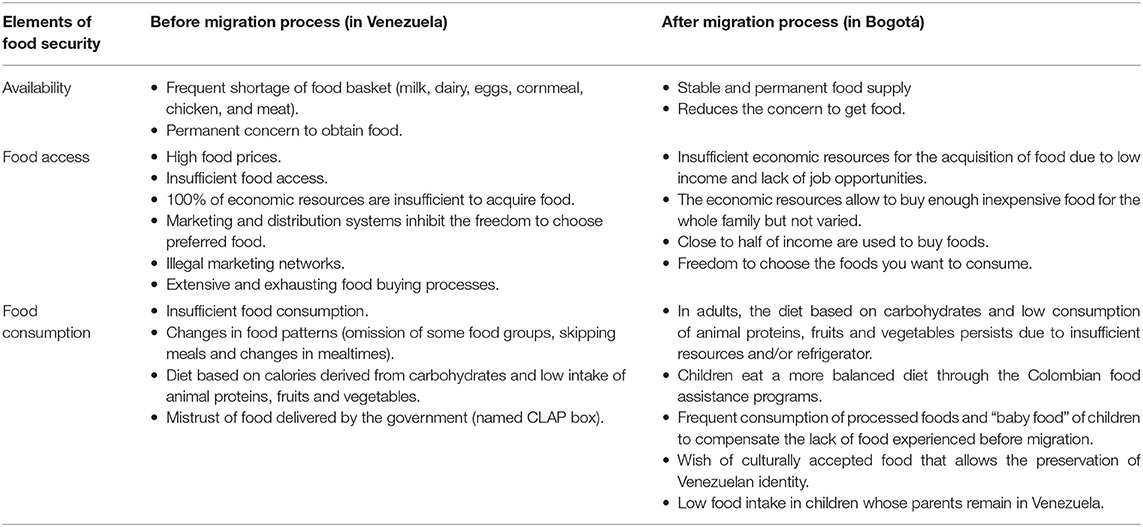

Changes in Food Security Components: Availability and Access to Food

Fourteen families expressed that in their places of origin in Venezuela they faced constant food shortages of milk, dairy products, eggs, corn flour, chicken, and meat, resorting to various search strategies to obtain food. One family stated that although their desired food items were available in Venezuela, the prices were very high and food access was very difficult. They also stated that 100% of their monthly income was not enough to afford food for the whole family.

In Venezuela, families prefer to purchase food from the “bachaqueros” or illegal traders, to avoid long waits, long lines, searching in various warehouses, and to choose the food they wanted. Using this strategy increases the food price up to five times. Subjects expressed their discontentment at not being able to freely choose their food, that they had specific days each week during which they could make purchases and a restriction of food quantity available to acquire.

Regarding the food availability for migrants after arrival in Bogotá, interviewed families recognized a significant improvement food access, encountering a great variety and affordable prices allowing them to select freely the foods they desire. Families consider that food is “cheaper” in Bogotá. However, for those without stable employment, the money available to buy food is still insufficient to purchase varied, nutritious, and sufficient food for their families. Overall, families felt that they recovered some of the dignity lost in Venezuela.

Families living in Bogota reported spending between 40 and 50% of their monthly income on food. More money is needed for food, but their income is low due to informal or unstable employment and prioritizing the payment of rent and utilities. Therefore, inexpensive food that is affordable for the whole family, for example, rice, pasta, oil, eggs, potatoes, bananas, cornmeal, and powdered milk, was often purchased but the purchase of foods such as chicken, meat, fish, dairy, fruits, and vegetables, was impractical, leaving participants without proper nutrition for a well-functioning body and ideal health status.

In all families, children under the age of five were linked to public kindergartens in Colombia. They received three meals (lunch and two snacks) from Monday to Friday. These foods are intended for the exclusive consumption by children, however, the families acknowledged that the whole family often partook. Below are some quotes from the subjects:

“Getting food in Venezuela is difficult. You have to wait, visit various stores, and negotiate with the bachaqueros (illegal vendors), so you can find food. The problem is that everything is very expensive” (Female, 34 years old, San Cristobal, Bogotá).

“The biggest difference is that in Venezuela you can't get the groceries to feed your whole family with your salary. Here in Bogotá, you can buy food cheap to feed the whole family, although those foods are not healthy” (Female, 36 years old, San Cristobal, Bogotá).

“That the children can go to a kindergarten where they are given a healthy diet is a great relief. From Monday to Friday, we worry about the food of two and not four. Also, the food basket that is delivered once a month helps us all“ (Female, 33 years old, Rafael Uribe, Bogotá).

Changes in the Food Security Components: Food Consumption

In Venezuela, adults consumed between 2 and 3 meals a day before embarking on their migratory route to Bogotá. Parents used the following strategies to maintain offering food to their children three times daily: limit the frequency and amounts of food consumed and change the schedule of food consumption (late breakfast, use lunch as the first meal, skip dinner). Families recognized that the possible food consumption in Venezuela was very limited in quantity and variety, which could be affecting the health status of their families. This situation generated constant concern and dissatisfaction. The gradual change in the composition of meals in Venezuela was a theme highlighted by the interviewees, who attested that they progressively went from originally eating four meals to one or two.

In Bogotá, families showed a significant improvement in food consumption after arrival. At the time of the interview, the families expressed that all family members ate at least three times a day. However, they recognized that their diets were high in carbohydrates and lacked fruits, vegetables, dairy, meat, and chicken due to economic constraints. Most families expressed they did not have a refrigerator to store and preserve perishable foods, nor blenders to make juices and soups, so they preferred not to buy items requiring these appliances. Participants reported intake of sugary drinks, sweets, bakery products, and unhealthy snacks because they had been difficult to buy in Venezuela, so upon arrival in Bogotá they “compensated” for lack of “pleasure,” food consumption. This excessive behavior can cause weight gain and other chronic diseases.

In Bogotá, these families were able to offer some types of foods to their children for the first time, including yogurt, petit-Suisse type cheese, compotes, and baby food, which they called “good for children.” This reinforces that migration has been worthwhile because it has increased the food variety, they are able to offer to their children.

Most families felt that foods and food preparations in Colombia were very similar to those in Venezuela. This similarity supports adaptation to the country, through the commonalities in food. In Bogotá, families are able to purchase ingredients for typical Venezuelan preparations and are able to buy ready-to-eat foods such as arepas, hallacas, cachapas (cornbread), and the typical main dish pabellón, with rice, meat, and black beans. When they consume these preparations, they feel closer to their country. The ability to maintain dietary habits and customs in Colombia triggered joy and satisfaction for migrants. However, this joy is at times overshadowed because food assistance programs in Colombia urged families to adapt to “Colombian food.” Here are quotes from some interviews:

“Before we came, the last weeks we only ate cassava and water, cassava in the morning, in the afternoon and at night, there was nothing else. The adults in the family ate twice a day, and the children ate three times, but they no longer wanted to eat. They told us they were tired of cassava, they wanted to eat something different” (Male, 35 years old, San Cristóbal, Bogotá).

“Here, we have been able to eat better. We eat more times a day and more varied, sometimes we can buy vegetables, chicken or meat but at least we are never short of rice, arepas, eggs, and bananas” (Female, 34 years old, Tunjuelito, Bogotá).

“In Bogotá, my daughter tasted healthy food for children like yogurt for the first time, it is one of her favorite foods. Every time I can give her a yogurt it makes me happy because the quality of food that she eats has improved and I feel coming here was worth it. In Venezuela, you couldn't choose” (Female, 30 years old, Rafael Uribe, Bogotá).

Discussion

Household characteristics is key for the analysis of food and nutrition security since members of households support the acquisition, preparation, and distribution of food. It has been identified that 52% of the Venezuelan migrant population in Colombia are men and 48% are women (Migración Colombia, 2019). The importance of the proportion of men and women in migrant families lies in the fact that in recent decades a “feminization” has emerged, that is, the participation of women in migratory movements (CEPAL, 2007). Food has a social role in strength relations. Families not reunited in their usual dietary customs has negative repercussions on food intake, especially in children, which is associated with emotional deterioration due to not being able to share food as a family (Haukanes, 2007).

Women's participation in the migration process has increased. For centuries, migration was led by men because women were more vulnerable to various forms of violence during the process mainly due to the risk of sexual violence faced by migrants and refugee women, since, to guarantee food for their families, they resort to sexual work (Shedlin et al., 2016). This vulnerability is still faced by women, who are at risk of sexual violence, illegal jobs, and prostitution. Venezuelan migrants report having experienced xenophobia and 15% have had difficulties feeding themselves in the last month (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2019). However, none of the families and women interviewed mentioned it. Probably the fact of having small children protect them.

The visibility of women in migration has been driven by the growing number of families with women as the head of the household. In our study, five households had a female head of the family, and eight households had a shared head of the family, meaning that women play a strong role in 13 out 15 families interviewed. Several authors state that women contribute to the well-being of migrant families because they preserve their role of caring for and protecting other family members through practices like food preparation. Besides, women transmit cultural symbols and maintain the desire for family reunification (Aguinaga, 2012).

Causes of migration to Bogotá, Colombia reflects a violation of human rights. The situations reported by families regarding the strategies and measures that they had to carry out in Venezuela to obtain food, violates human rights. Food and nutrition security, seen as a right, establishes that the State must guarantee people food availability and access, in a timely, dignified, and permanent manner. The reality of families living in Venezuela is the opposite, confirming previous findings of other researchers (Bernal et al., 2012; Landaeta-Jimenez et al., 2015), who highlighted the violation of Food Security recognized as a right in article 305 of the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. However, in Bogotá, the food and nutrition security of these families is neither guaranteed nor understood as a right. This is evidenced by the lack of job opportunities, difficulties with the legalization of the migrant status, and the limited access to food assistance for the new arrivals. Recently, in 2021, President Duque instituted a temporary legal status for Venezuelans that will hopefully improve the stability of migrants.

Changes in Food Security Components

Availability and access to food. The existence and worsening of food shortages in Venezuela such as milk, rice, corn flour, chicken, and meat lead to a decrease in purchases of foods with a high a content of protein, vitamins, and minerals. These nutrients are replaced with subsidized products, whose nutritional contribution is calories and carbohydrates. Informal food distribution networks, organized by “bachaqueros” who illegally buy, resell and distribute subsidized food at much higher prices (ENCOVI, 2020) further contribute to the food and nutrition security problems and motivates migratory movement.

A diet high in carbohydrates and low in vitamins and minerals was prevalent in study participants and continue after completion of the migration process. In Bogotá, although there is a wide variety of food, families do not have sufficient resources to purchase better food items for their families.

Even so, families interviewed consider that migrating was positive because a variety of food is permanently available and with little money, hunger can be satisfied. In contrast, in Venezuela, an entire income was insufficient to buy food for the whole family. However, the lack of job opportunities in Bogotá makes it difficult to buy diverse, varied, and nutritious food. This reality means that families are not completely satisfied with their situation in Bogotá.

Moreover, the food assistance that children received in childcare centers helped families by partially improving their food and nutrition security. Assistance programs reduce the pressure on families to procure enough food on a daily basis. However, this concern only diminishes when children attend the care centers, which does not happen on weekends or holidays.

Food consumption. After arriving in Bogotá, a significant improvement in the quantity of food eaten was observed, but not a correlating increase in variety. Although all families increased number of daily meals, due to economic limitations, they still did not have appliances such as a refrigerator or blender, and consequently, the consumption of food sources of proteins, vitamins, and minerals provided by fruits, vegetables, cheese, dairy products, chicken and meat was infrequent. In contrast, foods high in carbohydrates prevailed.

Skipping breakfast was a common practice in Venezuela, which was recovered after migration. The price of breakfast in Venezuela has increased by 2210% since 2015 and its usual composition has changed. 61% of Venezuelan families have changed their usual way of eating and 80% have had some food deprivation (Bernal, 2017). The lack of a varied diet that includes sufficient fruits, vegetables, and sources of protein were aspects that did not favorably change after migration. Due to the lack of job opportunities and low economic income, families buy mainly carbohydrate-based food sources. As such, the need for diet and nutrition education aimed at migrant families was evident given the reports of frequent consumption of processed products because of these products' unavailability in Venezuela.

In the migratory process “adequate food” can be approached from two points of view. First, the focus on the nutritional contribution and the satisfaction of calorie and nutrient needs. Second, consideration of cultural traditions so that food is socially accepted. In Bogotá, the interviewed families consumed a diet culturally appropriate but not nutritionally appropriate since a diet that is not very varied and based on foods high in carbohydrates does not satisfy nutritional needs. Eating typical Venezuelan preparations helps Venezuelans to maintain their food identity and provides contentment.

As indicated by the families, one of the elements of food and nutrition security managed by OBSSAN (Medina, 2014; OBSSAN, 2016) states that food is a central element of the identity of migrants.

Food affects health status. Migrant families stated that in Bogotá they could offer their children “baby foods,” which generally have high amounts of sugar. They also frequently consume sugary drinks, sweets, cakes, and unhealthy snacks because they have not had access to these products for a long time and they consider it inexpensive. As a result, they do not consume foods such as fruits, vegetables, cheese, dairy, chicken, and meat daily, arguing insufficient income. This situation reveals the need to carry out nutrition education actions with the migrant population. Although the purchase and consumption of food are personal decisions, there are structural factors such as advertising and commercial policies that also influence consumers (Table 2).

Childcare centers in Bogota receive migrant children and provide them with food assistance which improves their consumption of healthy food. This is a positive sign of openness to migrants, and caretakers recommend that parents accustom their children to “Colombian food” at home, to avoid rejection of meals offered in these centers. Having food roots is important to families and their cultural identity and preserves a connection with their country of origin. This situation highlights one of the criticisms made of food assistance: the overlooking of the cultural meaning of food (Pérez, 2006).

This study has limitations regarding methodological aspects. First, the family participants were those who accessed food assistance programs through childcare centers, so they had social protection from the government. Families not covered by any program were not part of this research, and surely are less protected. Second, the process of coding and categorization of interviews was done by the first author and verified by the third author, both of whom are experienced qualitative researchers. The analyses were done by all authors. Surely another qualitative researcher could have enriched the analysis. Third, due to the qualitative nature of this study, results only will apply to the participants, however, qualitative studies do not seek generalization of results. Common patterns were detected that will contribute to emerging topics in the area of migration and food security.

Conclusion

Migration is a process related to food insecurity. Most elements of food insecurity, from difficulties in availability and economic access, to consumption of foods, were present as reasons to leave Venezuela. Food insecurity experiences faced daily in Venezuela were described as obstacles to obtaining the quantity, quality, and preferred food for children and constituted causes for moving to Colombia for millions of Venezuelans. Bogota was the first city selected as a place where good conditions, including jobs, could be obtained for newcomers.

The migratory process partially improved the food and nutrition security of migrant families. After the migration, access to food was recovered, economic access and food consumption in terms of quantity improved, but the quality of food needs to be optimized since it affects the satisfaction of families and their children. The number of meals per day, the quantity, the access, and the participation of children in social programs, which includes food assistance, are some of the major positive changes. Venezuelan families achieve a culturally adequate diet since both countries have similar meals and ingredients. Typical Venezuelan meals can be prepared and contribute to the maintenance of their cultural identity and diminish the nostalgia for their country. In Bogotá, some children ate foods such as petit queso and yogurt for the first time, which is considered important and nutritious for families. This situation was impossible in Venezuela, which suggests that migration was necessary. They have regained the freedom to choose the food they want to buy and access food in a dignified and socially acceptable way, two key food security elements that were commonly unobtainable while living in Venezuela.

Our findings highlight the need to include the human rights approach in migration policies, including job opportunities, the maintenance of the cultural identity, equity, and protection of xenophobia against migrant populations.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/78054 (Pico, 2020).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by concept No. 009-123-18 of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the National University of Colombia, Bogotá Headquarters and according to Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Colombia corresponds to risk-free research (Ministerio de Salud, 1993). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

RP, SC, and JB conceived the research and contributed and approved the final manuscript. RP and JB wrote, discussed, and analyze the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Observatory of Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security of the University of Colombia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

To the Venezuelan migrant families who made it possible to learn about this part of their history and to the Observatory of Food and Nutrition Sovereignty and Security, an academic space in which this research was developed as a final master's thesis. Thanks to Tiffany Duque, Klaus Jaffe, Analy Perez, and Andres Ramirez Bernal for reviewing and making contributions to the manuscript.

References

ACNUR (2020). Situación En Venezuela. Available online at: https://www.acnur.org/situacion-en-venezuela.html (accessed May 25, 2021).

Aguilar, S., Mariel, C., Edwin, J., and Castellanos, L. (2015). “Migración y Remesas: están afectando la sustentabilidad de la agricultura y la Soberanía alimentaria en Chiapas?” Revista LiminaR. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos XIII: 29–40. Available online at: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1665-80272015000100003&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed May 25, 2021).

Aguinaga, M. (2012). Aportes feministas acerca de la soberanía alimentaria. Soberanías 66, 91–105. Available online at: https://rosalux.org.ec/pdfs/soberanias-libro.pdf#page=89

Aponte, C. (2020). El CLAP y la gran corrupción del siglo XXI en Venezuela. Revista Agroalimentaria 26, 147–166.

Bernal, J. (2017). Los Hábitos de Desayuno En Venezuela y Colombia: Una Comparación Reveladora. Revista Española de Nutrición Comunitaria 23:27. Available online at: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/es/ibc-169152

Bernal, J., Frongillo, E., Herrera, H., and Rivera, J. (2012). Children live, feel, and respond to experiences of food insecurity that compromise their development and weight status in peri-urban Venezuela. J. Nutr. 142, 1343–1349. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.158063

CARITAS Venezuela (2020). Monitoreo centinela de la desnutrición aguda y la seguridad alimentaria familiar. Boletín, XV: Caracas. Available online at: http://caritasvenezuela.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Boletin-SAMAN_Caritas-Venezuela_Abril-Julio2020-r1_compressed.pdf (accessed May 25, 2021).

Carmona, J., Ramirez, B., and Muñiz, I. (2017). Migración e Inseguridad Alimentaria en una localidad rural, Caso San Miguel Cosahuatla, Puebla, México, 21–35. Available online at: https://biblat.unam.mx/es/revista/regiones-y-desarrollo-sustentable/articulo/migracion-e-inseguridad-alimentaria-en-una-localidad-rural-caso-san-miguel-cosahuatla-puebla-mexico (accessed May 25, 2021).

CEPAL (2007). Feminización de las migraciones en américa latina: discusiones y significados para políticas, 125–131. Available online at: https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/jm_2007_feminizacionmigracionesal.pdf (accessed May 25, 2021).

CEPAL (2008). América Latina y El Caribe: Migración Internacional, Derechos Humanos y Desarrollo. Available online at: http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/2535/S2008126.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed May 25, 2021).

DANE (2019). Índice de Precios al Consumidor 2018-2019. Available online at: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/ipc/cp_ipc_dic18.pdf (accessed May 25, 2021).

Doocy, S., Ververs, M., Spiegel, P., and Beyrer, C. (2019). The food security and nutrition crisis in Venezuela. Soc. Sci. Med. 226, 63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.007

Efecto Cocuyo (2019). Cajas CLAP incluyeron menos alimentos y se distribuyeron de modo privilegiado en 2019. Available online at: https://efectococuyo.com/salud/cajas-clap-incluyeron-menos-alimentos-y-se-distribuyeron-de-modo-privilegiado-en-2019-segun-ong/ (accessed May 25, 2021).

ENCOVI (2020). Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida 2019-2020, Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (2020). Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Caracas, 2020. Available online at: https://miradorsalud.com/seguridad-alimentaria-en-venezuela-comparacion-de-la-encovi-2017-2020/ (accessed May 25, 2021).

ENSIN (2015). Encuesta Nacional de Situación Nutricional 2015. Available online at: https://www.icbf.gov.co/bienestar/nutricion/encuesta-nacional-situacion-nutricional (accessed May 25, 2021).

Expansión, D. (2019). Colombia inmigración 1990-2019. Available online at: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/migracion/inmigracion/colombia (accessed May 25, 2021).

FSIN (2020). Food Security Information Network, Global Network Against Food Crises. 2020 Global Report on Food Crises Joint Analysis for Better Decisions. Available online at: https://www.wfp.org/publications/2020-global-report-food-crises (accessed May 25, 2021).

Haukanes, H. (2007). “Sharing food, sharing taste? Consumption practices, gender relations and individuality in Czech families,” in Anthropology of Food. doi: 10.4000/aof.1912. Available online at: http://journals.openedition.org/aof/1912

Landaeta-Jiménez, M., Herrera, M., Vásquez, M., and Ramírez, G. (2015). La alimentación y nutrición de los venezolanos: Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida 2014. Anales Venezolanos de Nutrición 28, 100–109.

Medina, X. F. (2014). “Alimentación y migraciones en Iberoamérica,” in Alimentación y migraciones en Iberoamérica (Barcelona: Editorial UOC), 1–300. Available online at: http://digital.casalini.it/9788490643648

Migración Colombia (2019). Venezolanos en Colombia, Corte a 30 de Junio de 2019. Available online at: http://www.urosario.edu.co/consultorio-juridico/Documentos/Cartilla-Derechos-y-Dereberes-Venezolanos-en-Colom.pdf (accessed May 25, 2021).

Migración Colombia (2020). Radiografía de venezolanos en Colombia, Corte 30 de Julio de 2020. Available online at: https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/infografias/content/259-infografias-2020 (accessed May 25, 2021).

Miles, M., and Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ministerio de Salud (1993). Resolución 8430 de 1993. Bogotá: República de Colombia: Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 1–19.

OBSSAN (2016). Construyendo caminos hacia la garantía de la seguridad alimentaria y nutricional en Colombia. Available online at: http://obssan.unal.edu.co/wordpress/obssan-10-anos/ (accessed May 25, 2021).

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM) (2019). Informe sobre las migraciones en el mundo 2020. Available online at: https://publications.iom.int/books/informe-sobre-las-migraciones-en-el-mundo-2020 (accessed May 25, 2021).

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados, Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, and Organización de los Estados Americanos. (2019). Situación de Población Refugiada y Migrante de Venezuela en Panamá.

Palinkas, L., Horwitz, S., Green, C., Wisdom, J., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin. Policy Mental Health 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pérez, C. (2006). “Ayuda Alimentaria: Concepto, Evolución y Controversias.” Diccionario de Acción Humanitaria. Available online at: http://www.dicc.hegoa.ehu.es/listar/mostrar/145 (accessed May 25, 2021).

Pico, A. (2020). Seguridad Alimentaria y nutricional de familias migrantes venezolanas con asistencia alimentaria en Bogotá. Available online at: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/78054 (accessed May 25, 2021).

Salamanca, A., and Martín-Crespo, C. (2007). El muestreo en la investigación cualitativa. Nure Invest. 27, 1–4.

Sen, A. (2002). El Derecho a No Tener Hambre. Bogotá: Centro de Investigación En Filosofía y Derecho, Universidad Externado de Colombia, 1.

Shedlin, M., Decena, C., Noboa, H., Betancourt, O., Birdsall, S., and Smith, K. (2016). The impact of food insecurity on the health of Colombian Refugees in Ecuador. J. Food Security 4, 42–51. doi: 10.12691/jfs-4-2-3

Keywords: migrants, food and nutrition security, food insecurity, food availability, food assistance, humanitarian aid, Venezuela, Colombia

Citation: Pico R, del Castillo Matamoros S and Bernal J (2021) Food and Nutrition Insecurity in Venezuelan Migrant Families in Bogotá, Colombia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:634817. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.634817

Received: 29 November 2020; Accepted: 10 May 2021;

Published: 10 June 2021.

Edited by:

Maria S. Tapia, Academia de Ciencias Físicas, Matemáticas y Naturales de Venezuela, VenezuelaReviewed by:

Anabelle Bonvecchio, National Institute of Public Health, MexicoYngrid Josefina Candela, Central University of Venezuela, Venezuela

Copyright © 2021 Pico, del Castillo Matamoros and Bernal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Bernal, amVubmlmZXJiZXJuYWxyaXZhc0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Rocio Pico1

Rocio Pico1 Sara del Castillo Matamoros

Sara del Castillo Matamoros Jennifer Bernal

Jennifer Bernal