- 1Center for Good Food Purchasing, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 2Center for Good Food Purchasing, Berkeley, CA, United States

Adopted first by the City of Los Angeles in 2012, the Good Food Purchasing Program® creates a transparent supply chain and helps institutions to measure and then make shifts in their food purchases. It is the first procurement model to support five food system values—local economies, environmental sustainability, valued workforce, animal welfare and nutrition—in equal measure and thereby encourages myriad organizations to come together to engage for shared goals. Within just six years, the Good Food Purchasing Program has catalyzed a nationwide movement to establish similar policies in localities small and large across the United States, and inspired the creation of the Center for Good Food Purchasing. First adopted by the City of Los Angeles in 2012, it is a procurement standard that offers institutions a system in which current investments toward food are redirected toward more sustainable and fair suppliers. It uses a metric-based, flexible framework that produces a star rating. The Good Food Purchasing Program promotes the purchase of more sustainably produced food, from local economies, especially smaller and mid-sized farms and other food processing operations, which results in production returns at a more regional and local level, and ensures that suppliers' workers are offered safe and healthy working conditions and fair compensation, that livestock receives healthy and humane care, and that consumers—foremost school children, patients, the elderly—enjoy better health and well-being as a result of higher quality nutritious meals. This article will detail its implementation since 2012, provide current information on the impacts the Program has had on the agroecology of regions in the US food system, and recommendations for policy changes that could catalyze more accelerated impact.

Introduction

Adopted first by the City of Los Angeles in 2012, the Good Food Purchasing Program (the Program or GFPP) is a procurement program1 that fosters a transparent regional food supply chain and helps institutions to measure and then make shifts in their food purchases. It is the first procurement model designed to elevate government based food service as a transformative tool, using its significant purchasing power to support five food system values—local economies, environmental sustainability, valued workforce, animal welfare, and nutrition—in equal measure. Its adoption model encourages organizations to collaborate toward shared goals. The Program offers institutions a feedback tool which helps them to redirect food budgets toward more sustainable and high road suppliers.

Using a metric-based, flexible framework that produces a star rating, the Program promotes the purchase of more sustainably produced food from local economies, especially small- and mid-sized farms and other food processing operations, which results in production returns at a more regional and local level, ensures that suppliers' workers are offered safe and healthy working conditions and fair compensation, that livestock receives healthy and humane care, and that consumers—foremost school children, patients, the elderly—enjoy better health and well-being thanks to higher quality nutritious meals. Within just 6 years, the Program achieved impressive impact, and has now expanded to 20 cities and enrolled over 45 municipal institutions across the country. The systemically holistic Good Food Purchasing Program was given favorable mention in 20182 by the World Future Council, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and IFOAM Organics International.

The Good Food Purchasing Program

Program Development, Expansion, and Impact

California is the world's fifth largest supplier of food, cotton fiber, and other agricultural commodities, the largest producer of food in the U.S.3, and in 2018 was the world's fifth largest economy surpassing that of the United Kingdom4. The Greater Los Angeles Area is the nation's second-most populous urban region in the United States, with 18.7 million residents as of 20155. The City of Los Angeles is the most populous of the many cities in the region (it is the second largest city in the country) and in 2018 the Greater Los Angeles metropolitan area had the third largest gross metropolitan product in the world at nearly $1trillion, behind New York and Tokyo6. It is the de facto leader of the Southern California region in terms of economic and other influence.

In September 2009, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa announced the creation of the Los Angeles Food Policy Task Force. The announcement came as a key inflection point in the development of a regional food policy initiative, which was the conception and project of the author of this article, Paula Daniels, who was then a senior member in the administration of Mayor Villaraigosa, serving at the time as Commissioner with the Board of Public Works. Commissioner Daniels undertook to research and advocate for the City of Los Angeles to develop and advance a regional food policy framework to which the Mayor agreed. Along with the announcement of the creation of the Los Angeles Food Policy Task Force, was the Mayor's directive to prepare a report with recommendations to address certain key food system issues, including whether or not there should be a food policy council. The Mayor designated Commissioner Daniels to lead the task force; she then recruited the membership of the task force, with input from staff members of the Urban and Environmental Policy Institute of Occidental College.

The membership of the Task Force was a careful process of curation, with criteria for inclusion based on: (1) food system sector representation; (2) well-recognized leadership in their respective field; (3) gender and ethnic diversity; (4) ability to function well-enough in a team context to be able to synthesize ideas for a report (see Figure 1 for a list of the Task Force members).

Figure 1. Image from page ii of the report of the Los Angeles Food Policy Task Force, called Good Food for All Agenda (2010), available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5bc50618ab1a624d324ecd81/t/5be5da9bc2241b38ebd245a7/15.

Concurrently, Commissioner Daniels secured funding for a staff position to assist in coordinating the work of the Task Force. Alexa Delwiche (co-author of this report) was hired as Task Force Coordinator and played a role in stakeholder engagement and program development.

The Task Force convened in November 2009 and was charged with developing a food policy framework for Los Angeles as the head of the Southern California region. The task force adopted a goal of becoming a “Good Food” region, with “Good Food” defined as food that is healthy, affordable, fair and sustainable. Over the course of 10 months, Task Force members conducted strategy sessions and developed a policy platform, incorporating input from over 200 cross sector individuals and organizations in extensively curated roundtable discussions and listening sessions. In July 2010, the Task Force released a report called the Good Food for All Agenda, which described the then existing food system challenges of Los Angeles, as follows:

Our current sources of food largely consist of cheap, high calorie, low nutrient and highly processed food, often shipped from far away and grown by unsustainable practices. Industrial farms and the extensive transportation of their output debilitate the natural environment through water use, chemical impacts, and air quality. At the same time, the health and well-being of farm and food workers are often sacrificed to meet demands for cheaper food…

Because of persistent poverty and growing unemployment in Los Angeles, hunger has remained a chronic problem in the region. For many families, the consumption of too many cheap calories and too little exercise has caused a diabetes and obesity epidemic. Good Food is not available in many low-income areas and neighborhoods of color…In these neighborhoods, convenience stores selling cheap, unhealthy foods overwhelm the neighborhood food environment.

The report recommended 55 action steps in six priority areas, directed toward the goal of building a more sustainable and equitable regional food system in the LA region of southern California7. Mayor Villaraigosa approved the report recommendations, and the Los Angeles Food Policy Council (LAFPC) was created as a result of one of the report recommendations.

Commissioner Daniels was named Chair of the LAFPC and along with the staff support of Alexa Delwiche, continued to develop the organizational infrastructure for it, including fundraising, staffing, staff development and mentorship, development of the organizational charter and mission, establishment of its non-profit status and fiscal sponsorship, and creation of the unique organizational structure of the LAFPC, as well as the creation of working groups to allow for unlimited stakeholder participation. As a senior city official, she secured meeting space for the council and the working groups at city facilities, and housed the growing staff of the LAFPC (for which she had raised funds) in her suite offices at City Hall (where the non-profit LAFPC continues to be housed as of this article).

The first meeting of the LAFPC was in January of 2011. Its membership was envisioned by the Task Force as a larger body than the Task Force itself, limited (in order to have balance of perspective) to two from each identified sector area. Most Task Force members also became LAFPC council members. (The vision for the LAFPC and its representation is found at pages 84–86 of the Good Food for All Agenda, fn 7). The initiative proved to be of great interest to the community at large, and participation in the working group meetings averaged well over 120 individuals representing various organizations. As a result of the increasing interest in and complexity of the LAFPC work, Mayor Villaraigosa named Paula Daniels as his Senior Advisor on Food Policy—the first such position at the senior staff level (equivalent to Deputy Mayor) in the country. By June of 2013, the end of Mayor Villaraigosa's second and final term in office, the LAFPC had grown to eight full time staff members operating as backbone, or secretariat, to the 40 member LAFPC council, and the hundreds of working group members (see Figure 2 for a depiction of the working group membership).

Figure 2. Image created in 2013 by Alexander Tarr, (currently assistant professor of geography at Worcester University), to represent the number and category of stakeholders participating in the LA Food Policy Council. Each square represents a participating organization, arrayed according to the work area they participated in for the LAFPC. Shown in the left column is the work area Institutional Good Food Purchasing, which was the organizational home of origin for the Good Food Purchasing Program.

The well-staffed, local government supported LAFPCgave rise to the Good Food Purchasing Program (the Program), as one of its many initiatives.

The Program was designed through an extensive two year process, involving multi-sector, interdisciplinary, and multi-stakeholder collaboration and an iterative review process by the designated team of the LAFPC, which included the Mayor's Senior Advisor on Food Policy. After arriving at a program design with LAFPC Working Group input, the policy and program was vetted by more than 100 local, state, and national public, private, and non-profit organizations through a due diligence process led by the Mayor's office in its role as LAFPC lead.

At the culmination of the design, development and review process, Mayor Villaraigosa issued an executive directive ordering all general funded city departments that purchased over $10,000 of food to adopt the Program. A motion in support of the directive was also adopted by the Los Angeles City Council on the same day. Consequently, on Food Day, October 24, 2012, the City of Los Angeles became the first institution in the country to take the early risk of embarking on the new Program. Just weeks later, the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD)—which served 650,000 meals each day and is the largest food purchaser in Los Angeles—became the second institution to sign on to implementing the Good Food Purchasing Program.

The LAFPC built out the Program in detail, to guide data collection and implementation. It provided programmatic support in areas such as increasing supply chain transparency, data collection, record-keeping, menu design, bidding processes, and assessing suppliers' adherence to the five values.

Within 1 year, the Program adoption at LAUSD met with the success that its design was intended to promote: local sourcing of produce rose from an average of 10% per year to an average of 60% per year, redirecting USD 12 million to the local food economy. As a result, 150 new well-paid food chain jobs were created in L.A. County, including food processing, manufacturing and distribution. In the ensuing years, 160 truck drivers in LAUSD's supply chain received higher wages and improved working conditions.

Due to the immediate success of the Program at LA Unified School District, interest in adoption by other cities was piqued. In 2015 the Program was spun off from the LAFPC and became the program of the Center for Good Food Purchasing, which was established to advance the national expansion of the Program. The Program has since expanded significantly. As of June 2020, there are 49 institutions in 20 cities across the US enrolled in the Program in addition to LA, including New York, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, Minneapolis and many others. These institutions collectively spend over $1 billion on food annually.

As a result of its contribution to advancing agroecology, the Program was recognized with an honorable mention for the Future Policy: Scaling Up Agroecology Award in 20188 by the World Future Council, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and IFOAM Organics International.

Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The Center coordinates a network of national partners, local coalitions, food service directors, and elected officials across the country to implement and scale the Good Food Purchasing Program. In cities across the country, the Center works with a network of cross-sector partners at the national and local levels to expand the Program's reach and impact. Among the key national partners are the Food Chain Workers Alliance, Real Food Media and the HEAL Food Alliance.

Local, multi-sector coalitions help to ensure that Program adoption and implementation in a city or region reflects community priorities and complements existing work on the ground. Local coalitions help to recruit institutions, secure formal program adoption through policy, and influence public procurement processes to ensure that institutions and their vendors are held accountable to their policy commitments and that public contracts reflect community priorities.

The Program is implemented by food service directors of public institutions, such as school districts, hospitals, jails, and municipally operated concessions such as recreation centers, entertainment venues, and airports.

Primary beneficiaries are the low-income individuals, families and children served by public institutions such as schools, municipal programs, corrections and hospitals. One of the primary reasons the program targets public institutions is because these institutions play such a critical role in ensuring access to healthy food by low-income children, families, and communities of color, including seniors. For example, free-and-reduced price lunch9 eligibility rates range from 65 to 85% in school districts enrolled in the Program, and as many as 90% of those are disadvantaged students of color.

Other beneficiaries of the Program who benefit from the additional economic support that the Program encourages include: (1) farm and food chain workers, a majority of whom are people of color, have extremely low incomes, are exposed on a daily basis to toxic pesticides, and lack access to safe drinking water due to groundwater contamination from agricultural runoff; and (2) small- to mid-sized producers practicing agroecological and high welfare farming and ranching, who struggle to compete with large, industrial producers in accessing institutional supply chains.

Purpose and Objectives

The Program's purpose is to harness the purchasing power of major institutions to encourage greater production of sustainably produced food, healthy eating, respect for workers' rights, humane treatment of animals and support for the local small business economy in order to achieve an economy of scale in a community oriented, “Good Food” system.

Methods and Modalities

The Program's metric-based, flexible framework (the Good Food Purchasing Standards) encourages large public institutions to measure and then make shifts in their food purchases. It is the first procurement model to support five core food system values—local economies, environmental sustainability, valued workforce, animal welfare and nutrition—in equal measure. By adopting the framework, food service institutions commit to improving their regional food system by implementing meaningful purchasing standards in all five value categories:

• Local Economies: The Good Food Purchasing Program (the Program) supports local small and mid-sized agricultural and food processing operations. The definition is based on a combination of farm size (based on revenue), farm ownership structure (family or cooperatively owned), and farm distance from the purchasing institution (based on driving distance). Farm sizes refer to USDA definitions.

• Environmental Sustainability: The Program requires institutions to source from producers that employ sustainable production systems that reduce or eliminate synthetic pesticides and fertilizers; avoid the use of hormones, routine antibiotics and genetic engineering; conserve and regenerate soil and water; protect and enhance wildlife habitats and biodiversity; and reduce on-farm energy and water consumption, food waste and greenhouse gas emissions; as well as to increase menu options that have lower carbon and water footprints. Examples of certifications include: Rainforest Alliance Certified, Seafood Watch, USDA Organic, etc.

• Valued Workforce: The Program promotes safe and healthy working conditions and fair compensation for all food chain workers and producers. The baseline is compliance with basic labor laws by the institution, vendor(s) and all suppliers. Examples of certifications or practices: union contract, worker-owned cooperative, Fair Trade Certified, Fair for Life, etc.

• Animal Welfare: The Program promotes healthy and humane care for farm animals. Examples of certifications in the Good Food Purchasing Standards include: USDA Organic, Certified Humane, Animal Welfare Approved etc.

• Nutrition: The Program promotes health and well-being by offering generous portions of vegetables, fruit, whole grains and minimally processed foods, while reducing salt, added sugars, saturated fats, and red meat consumption, and eliminating artificial additives. A 25-item checklist was initially developed with the L.A. County Department of Public Health, and is aligned with national standards, such as the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act.

The Center conducts the verification; scoring and recognition are central components of Program adoption by the institutions [for those familiar with LEED certification (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), the Program functions in an analogous fashion, and a comparison could be made between the Center's role vis the Program and the role of the US Green Building Council for LEED]. The verification process works in this way: when an institution adopts the Program, the Center works with them to collect in depth information about purchasing and food service practices, and rates the institution according to the rubric of the Center's copyrighted Standards. Each of the five value categories has a baseline standard, which indicates that the institution has met the Good Food Purchasing standards in at least 15% of its sourcing in each of the five values. Meeting even higher standards results in more points being awarded. The accumulation of points across all values is used to calculate and award a star rating. The baseline and higher standard purchasing criteria are set out in the Good Food Purchasing Standards, which are regularly reviewed and updated with a new version every 5 years. There are five status levels of a Good Food Provider (1–5 Stars) that correspond to a respective range of points. In order to achieve a Good Food Provider–5 Star level, the institution must achieve 25 or more points. After the first year, purchasers are expected to gradually increase the amount of Good Food that they purchase.

The expansion of the Good Food Purchasing Program is a highly collaborative, networked strategy. Cross-sector collaboratives of community, local policymakers, institutions, and value-chain partners exist in every city where the Center works. The local organizations who lead local Good Food Purchasing initiatives are deeply rooted in their communities, and while they represent a diverse range of interests, they participate in Program adoption at a selected array of local anchor institutions, recognizing this procurement strategy as a key economic lever for transforming the local food system toward one with an enduring commitment to the agroecological principles of economic equity, healthy equity, and environmental sustainability. The Center's staff works in close partnership with these communities to support community-driven efforts to use the Program as a tool to advance their local food system priorities.

Examples of the Local Partner Engagement

As of June 2020, the Center is actively engaged in 20 US cities, with a number of additional regions in the pipeline. While each city's Good Food Purchasing Program efforts are unique, a typical engagement involves dozens of local and national partners, interfacing with the Center and institutional partners all along the Good Food Purchasing journey. The following are illustrative examples from four cities.

Los Angeles

In Los Angeles, the LAFPC is now the local lead partner, serving as an accountability partner to enrolled city departments and the LAUSD. The LAFPC convenes local cross-sector stakeholders, builds broad support for the Program, identifies new institutions to recruit into the initiative, leads local efforts with partners, ensures a rigorous implementation of the Program by participating institutions, and maintains local relationships with public officials.

In Los Angeles, the Program's impacts continue to ripple throughout the city and region. The Program has helped redirect taxpayer dollars toward more values-aligned suppliers for receiving institutional food contracts. For example, due to successful organizing efforts led by the Food Chain Workers Alliance and a coalition of local advocates, the meat processor Tyson Foods was prevented from receiving a multimillion dollar chicken contract from the Los Angeles Unified School District due to their repeated egregious labor violations, as well as Tyson's environmental and animal welfare practices.

LA Unified School District currently purchases over $17 million in food from local growers and manufacturers. As of 2018, the school district was purchasing 96 percent of its chicken raised without routine antibiotics—just shy of the goal of 100 percent they set in 2014 as part of their Good Food Purchasing Program commitment and Urban School Food Alliance membership.

LAUSD has also promoted a valued workforce in its supply chain through the Program, contributing to the Teamsters Local 63 and Joint Council 42's efforts to secure union contracts for truck drivers and warehouse workers at a food distribution company. The Local and Joint Council were able to make the case for higher wages and workplace protections for 320 drivers and warehouse workers based on LAUSD's Good Food Purchasing Program commitment. These workers have seen their base salary increase by over 40 percent. Additionally, they are guaranteed raises over the next three years, have a grievance procedure, a voice with management, and a new pay incentive program.

Chicago

The Chicago Food Policy Action Council and a coalition of over 40 organizations organized a successful campaign that led to the adoption of the Program in the City of Chicago, the Chicago Parks District, and Chicago Public Schools in 2017. And with leadership from then-Cook County Board Commissioner Jesus “Chuy” Garcia and the County's Commission on Social Innovation, the county followed suit in 2018, making it the first county (a distinct municipality from a city) in the nation to adopt the Program. In Cook County, enthusiasm for the Program came in large part from those businesses, workers, consumers, and farmers that have long been marginalized in the food system. Under the Program, the County will incentivize contracts with minority- and women-owned businesses. In addition, the County is using the Program as a tool to connect with and accelerate other high priority equity initiatives, such as urban farmland preservation with community ownership, and transitioning publicly owned vacant lots to minority-owned social enterprises and public land trusts.

New York

The Mayor's Office of Food Policy supports implementation efforts by offering sustained leadership, convening agencies and key stakeholders through a task force structure and serving as a de-facto project manager for the City of New York's Good Food Purchasing engagement. Concurrently a coalition of ~40 cross-sector organizations, led by Community Food Advocates, Food Chain Workers Alliance, and CUNY Urban Food Institute, meet regularly to coordinate their collaboration, the goal of which is to ensure the city's internal commitment to the five values is institutionalized through adoption of the Program, along with a Good Food Purchasing policy. The Mayor's office is also working to align the agency commitments with the community's priorities.

Austin

In February 2019, after a three-year pilot program, Austin Independent School District (AISD)—serving 75,000 meals per day on 129 campuses and managing a $13 million annual food budget—officially became the first school district in Texas to adopt the Good Food Purchasing Program. As a member of the Austin Good Food Purchasing Coalition, convened by the City of Austin's Office of Sustainability, AISD (along with two other Austin-based public institutions) was one of the first institutions outside of California to pilot the Program. Since 2016, the Center for Good Food Purchasing has worked with AISD to track and measure consistent improvement in their performance across the value categories. Expenditures on organic products tripled over the first 2 years in the Program. In 2018, AISD invested in dedicated staffing to help them obtain a four-star rating and earn their Good Food Provider status. Since then, AISD has made meaningful progress in implementing strategies to accelerate their good food purchases by releasing bids for bulk organic milk and grass-fed beef to bolster performance in environmental sustainability and animal welfare.

Aggregated Impact and Influence

Los Angeles (the first city to adopt the Program) is an example with the most longitudinal information. Since 2012, the Program has influenced ~750,000 meals a day in L.A. City Departments and LAUSD, which alone serves over 600,000 students. In addition to the immediate impacts noted above, continuous improvement has been made in that district. For example, LAUSD's bread distributor had been sourcing out-of-state wheat for its USD 45–55 million annual servings of bread and rolls; due to participation in the Program the bread vendor changed its sourcing so that now, nearly all of the L.A. school district's bread and rolls are made from wheat grown on 44 Food Alliance-certified farms in California, milled in downtown L.A. These impacts extend beyond LAUSD as the same vendor, Gold Star Foods, now distributes these same products to over 550 schools across the western United States.

There has been a 15 per cent decrease in spending on meat by LAUSD due to implementing Meatless Mondays, which each week saves about 19.6 million gallons of water. From 2011 to 2017, LAUSD reduced purchases of all industrially-produced meat (beef, poultry and pork) by 32 percent, which led to reductions in their carbon and water footprint by 20 percent and 20.5 percent per meal, respectively, since the baseline year of 2012. The reduced carbon footprint translates to about 9 million kg of CO2 emissions avoided per year—the equivalent to taking 1,930 cars off the road, and the water saved results in a total annual water savings of more than 1 billion gallons, enough water to fill 1,760 Olympic-sized swimming pools every year10.

Leading the way, L.A. City Departments and LAUSD set an example that has since influenced many further areas in the U.S. As highlighted by the Union of Concerned Scientists in their 2017 report on the impacts of the Good Food Purchasing Program in Los Angeles, the “benefits of a better supply chain are amplified across institutions and regions.”11 Indeed, the recent calculations of the Center, based on over 10 years of data acquired from the institutions enrolled in the Program show combined totals across institutions of over $56,000,000 in supporting local economies, over $32,000,000 in supporting fair labor, over $20,000,000 toward meat raised without routine use of antibiotics, and an additional $10,000,000 supporting environmental sustainability.

Complementary Laws and Policies

In his Briefing Note 8 (April 2014), “The Power of Procurement: Public Purchasing in Realizing the Right to Food,” UN Special Rapporteur Olivier De Schutter recognized that “Governments have few sources of leverage over increasingly globalized food systems—but public procurement is one of them. When sourcing food for schools, hospitals and public administrations, Governments have a rare opportunity to support more nutritious diets and more sustainable food systems in one fell swoop.”

Procurement is also one of the recommended actions of category five of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, which calls for a review of “public procurement and trade policy aimed at facilitating food supply from short chains linking cities to secure a supply of healthy food, while also facilitating job access, fair production conditions and sustainable production for the most vulnerable producers and consumers, thereby using the potential of public procurement to help realize the right to food for all.”12

The Good Food Purchasing Program is also consistent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and sustainable procurement goals of other organizations, as shown in Table 1.

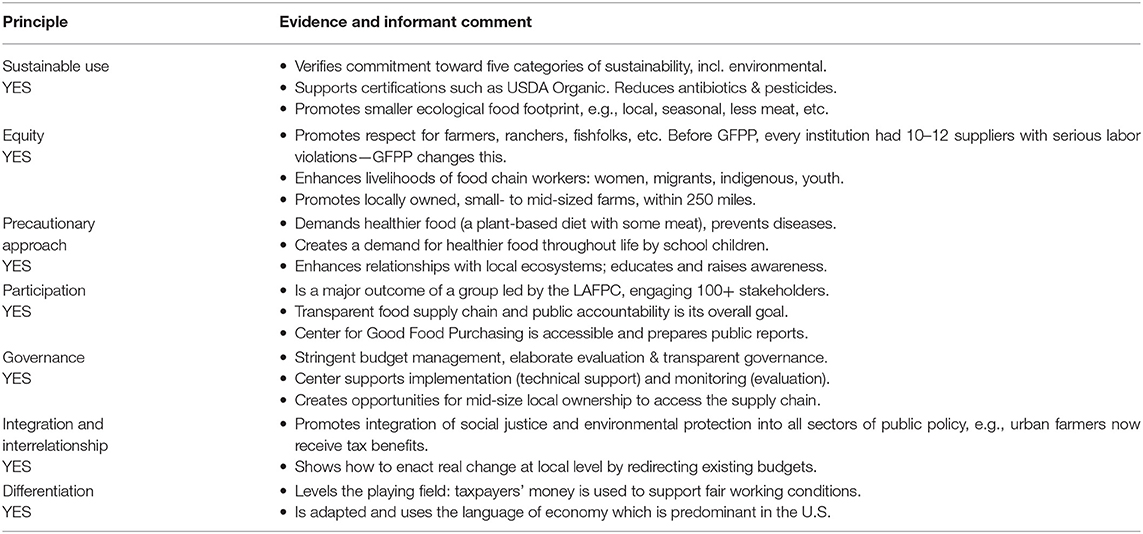

The Future Policy 2018 Award

The systemically holistic Good Food Purchasing Program was favorably recognized in 2018 by the World Future Council, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and IFOAM Organics International. Table 2 outlines their evaluation assessment and score.

Actionable Recommendations and Conclusions

Based on the Center's experience in working with local and national partners, the following key elements are instrumental in utilizing a procurement policy, such as the Good Food Purchasing Program, in creating a more agro-ecologically oriented food system on a regional scale:

• A collaborative, multi-sector coalition (like a food policy council) focused on a localized food system with shared values of community, equity, economic and environmental health

• Supply chain infrastructure that includes mission driven centers of aggregation, processing, and distribution (food hubs), dedicated to the same vision and goals of the collaborative

• Deeply invested, community informed local government leadership to connect the necessary dots within and across the many city and county agencies that intersect with food – which should include the workforce and economic development teams, in recognition that the food system is an economic one that responds to financial incentives and investments.

In order to accelerate the economic viability of an agro-ecologically oriented regional food system, an overarching goal should be developed to:

• Establish aggregate, quantifiable goals across the range of large anchor institutions (schools, hospitals, jails, recreational venues) in a region, to direct the combined purchasing power of the large anchor institutions toward increasing economic viability along a values based supply chain (such as the goals found in the Good Food Purchasing Program).

The procurement processes of large institutions allow them to obtain reasonable percentages of values-based food within their budgets, as conveyed to the food service or supply bidders through Requests for Proposals. The financial security of the long term, high volume contracts of schools and other large institutions is a de-risking opportunity for the supply chain.

If cities as centers of regional food change were to coordinate their public food procurement contracts with value based goals, the combined purchasing power could be the basis for a more equitable, community centered mid-scale food supply chain, operating alongside the more globalized supply chain in the way renewable energy operates alongside the prevailing energy fuel system.

A mid-tier13 or community level system—one organized as a regional supply chain calibrated with value based purchasing policies with large scale commitments from public institutions—could support entrepreneurial responsiveness to the varied needs of a community.

• Cities and counties should adopt purchasing targets for all their large food service institutions that direct a meaningful percent of purchases to the public values of local economic support, fair wages and working conditions, and people and planetary health.

• Goals supporting local economies, sustainable production practices, fair labor practices, and nutritional health should be targeted and implemented with equivalent priority.

• Equity goals should be front and center, as shown in the Good Food policy resolutions of Cook County, Illinois14, and should incorporate access to land and capital for historically dispossessed communities15.

• City and county leaders should aggregate the institutional targets into regional targets. They should extend their reach beyond municipal and school food to include hospitals, military bases, jails and other publicly funded food programs available in each city. The aggregate dollars available to nurture a good food system, would be more than enough to make a difference in the regional food economy and in the well-being of their region.

• Those targets should be backed up with contractual commitments to producers and distributors.

• Develop and direct financial incentives to the anchor institutions to enable purchasing support for fair wage and climate friendly food production practices such as soil health. Incentives should include an increase in school meal reimbursements for the procurement of local, sustainable, fair, and humanely produced foods to provide all students access to nutritious, high-quality, local food, building on the pioneering local food incentive models established in Michigan16, Oregon17, and New York18.

A system that serves community health, workers, and local businesses along those supply chains, can be a more resilient system in times of crisis. Healthy food, and the ability to make a fair living producing, picking, packing, and processing it, are essential to the equitable well-being of everyone who participates in the food system. The food system provides an essential good and service, and managing it in a way that is sustainable for the planet and people is a social, economic and environmental imperative.

Author Contributions

PD and AD were responsible for the design, development, critical review, and implementation of the Program as the LAFPC Coordinator (AD), and the LAFPC Founder, Chair and Senior Advisor to the Mayor (PD). They since became co-founders of the Center for Good Food Purchasing, where AD is Executive Director. This report, which they wrote jointly, is their first person account of the program development, expansion, and implementation impacts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript has been presented in part from 2018 The Future Policy Award materials of the World Future Council, https://www.futurepolicy.org/healthy-ecosystems/los-angelesgood-food-purchasing-program/, and also previously presented in part from the Center for Good Food Purchasing, https://goodfoodpurchasing.org/.

Footnotes

1. ^GFFP Standards, September 2017. Available online at: https://gfpp.app.box.com/v/GFPPStandards2017 (accessed June 17, 2020).

2. ^Good Food Purchasing Program. FuturePolicy.org. Available online at: https://www.futurepolicy.org/healthy-ecosystems/los-angeles-good-food-purchasing-program/ (accessed June 17, 2020).

3. ^AG Hires. Available online at: https://aghires.com/california-largest-food-producer-u-s/ (accessed June 17, 2020).

4. ^“California is now the world's fifth-largest economy, surpassing United Kingdom” (Associated Press, May 4, 2018). Available online at: https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-california-economy-gdp-20180504-story.html (accessed June 25, 2020).

5. ^US Census, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States – Combined Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico https://archive.vn/20200213005001/http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/PEP/2015/GCTPEPANNR.US41PR; 2019 updates available to download here: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html.

6. ^US Bureau of Economic Analysis, CAGDP1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) summary by county and metropolitan area. https://apps.bea.gov/itable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=70&step=1 Accessed June 25, 2020.

7. ^Good Food for All Agenda. Los Angeles Food Policy Task Force (2010) Available online at: https://goodfoodlosangeles.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/good-food-full_report_single_072010.pdf (accessed June 17, 2020).

8. ^Good Food Purchasing Program. FuturePolicy.org. Available online at: https://www.futurepolicy.org/healthy-ecosystems/los-angeles-good-food-purchasing-program/ (accessed June 17, 2020).

9. ^The US National School Lunch Program. Available online at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp (accessed June 17, 2020).

10. ^Reinhardt, S., and Kranti M. (2018). Purchasing Power: How Institutional “Good Food” Procurement Policies Can Shape a Food System That's Better for People and Planet (Union of Concerned Scientists). Available online at: https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2017/11/purchasing-power-report-ucs-2017.pdf (accessed June 17, 2020).

11. ^Id.

12. ^Available online at: http://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/text/ (accessed June 25, 2020).

13. ^Lyson, Thomas A., Stevenson, G. W., Welsh, R. (1998). Food and the Mid-level Farm: Renewing an Agriculture of the Middle. Cambridge: MIT Press.

14. ^Cook County Board of Commissions. Resolution To Adopt The Good Food Purchasing Policy. 14 May 2018. Available online at: https://gfpp.app.box.com/v/Resolution-CookCountyIllinois (accessed June 17, 2020).

15. ^Union of Concerned Scientists and Heal Food Alliance (2020). Leveling the Fields: Creating Farming Opportunities for Black People, Indigenous People, and Other People of Color. Cambridge.

16. ^10 Cents a Meal for Michigan's Kids & Farms. Available online at: https://www.tencentsmichigan.org/ (accessed June 19, 2020).

17. ^Kane, D., Kruse, S., Ratcliffe, M. M., Sobell, S. A., Tessman, N. (2011). The Impact of Seven Cents. Available online at: https://ecotrust.org/media/7-Cents-Report_FINAL_110630.pdf (accessed June 19, 2020).

18. ^Farm-to-School. New York State. Available online at: https://agriculture.ny.gov/farming/farm-school (accessed June 19, 2020).

Keywords: purchasing power, institutions, GFPP, Los Angeles, values, transparency equitable, sustainability, regional food system

Citation: Daniels P and Delwiche A (2022) Future Policy Award 2018: The Good Food Purchasing Program, USA. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:576776. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.576776

Received: 27 June 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2021;

Published: 11 January 2022.

Edited by:

Caterina Batello Cattaneo, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ItalyReviewed by:

Stephen J. Ventura, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesHenry Jordaan, University of the Free State, South Africa

Copyright © 2022 Daniels and Delwiche. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexa Delwiche, YWRlbHdpY2hlQGdvb2Rmb29kcHVyY2hhc2luZy5vcmc=; Paula Daniels, cGRhbmllbHNAZ29vZGZvb2RwdXJjaGFzaW5nLm9yZw==

Paula Daniels

Paula Daniels Alexa Delwiche

Alexa Delwiche