A multiscale inflammatory map: linking individual stress to societal dysfunction

Explainer

Front Sci, 12 March 2024

This explainer is part of an article hub, related to lead article https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2023.1239462

Linking stress and inflammation to societal and planetary health

Stress and inflammation play key roles in our health. But could their impacts extend far beyond the individual—and even to the Earth itself? In their Frontiers in Science lead article, Vodovotz et al. present two groundbreaking hypotheses. The first explains how inflammatory stress in the body can affect our thinking and behavior. The second explains how this effect in individuals could scale up to entire populations and drive societal dysfunction and environmental degradation. Together, these represent a paradigm shift in how we view inflammation: no longer a biological process restricted to individuals, but a multiscale driver that connects stressors affecting individuals to the detrimental actions of collectives, with planetary-scale impacts. The article also presents a mathematical model to test this novel idea. Based on preliminary simulations, the authors suggest strategies for reducing stress and building resilience in individuals and societies. They argue that such interventions are more crucial than ever given increases in stress worldwide and rising global concern over challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, war, and economic uncertainty. This explainer summarizes the article’s main points.

What is the link between stress and inflammation?

Stress comes in many different forms. These include physical assaults like illness and injury, and social and environmental stressors like competition for resources, threats to our safety, and anxiety. Our bodies respond by activating specialized cells, hormones, and other molecules in a process called inflammation.

Most inflammation is beneficial, helping the body to remove the stressor and heal. But if the response becomes dysregulated—such as when an organism suffers multiple, overwhelming, or relentless stressors—then inflammatory cells and molecules can damage healthy tissues and organs. A feed-forward loop of further inflammation and damage may then ripple through the body, resulting in chronic inflammation. This in turn can trigger other health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and depression.

How could inflammation affect our thinking and behaviors?

Researchers have observed a link between chronic inflammation and impaired brain function but have not yet uncovered the biological mechanism.

The authors propose a novel explanation: that the brain builds its own copy of bodily inflammation. Normally, this “central inflammation map” allows the brain to monitor and regulate the inflammatory response and promote healing. However, in the same way that prolonged or dysregulated inflammation can harm healthy body tissues, the inflammation map may harm the brain—causing impairments in cognition, emotion, and behavior.

How could inflammation drive societal and planetary outcomes?

The authors propose that the intertwining of stress, chronic inflammation, and impaired cognition in individuals can scale up to entire populations—with potentially far-reaching societal and environmental consequences. Their theory goes like this:

1. stress, and hence inflammation, can be transmitted from individuals to populations

2. high levels of chronic inflammatory stress within a population could impair decision-making and behavior at scale

3. this in turn could impair our ability to address the initial stressors

4. positive feedback loops in each of the above result in a multiscale, runaway process that ultimately leads to large-scale societal dysfunction and planetary-scale impacts on the environment.

This dynamic is not new but would have been restricted to small communities in the past. The authors argue that today, social media and other global digital communications are amplifying the transmission of stress at an unprecedented rate. This could account for current high levels of stress reported for the global population and an increased sense of constant danger.

The authors suggest their hypothesis could explain the counter-intuitive responses of large numbers of people to stressors like climate change, conflict, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, our collective failure to adequately address these global crises causes even more anxiety and stress, further fueling the multiscale feedback loop.

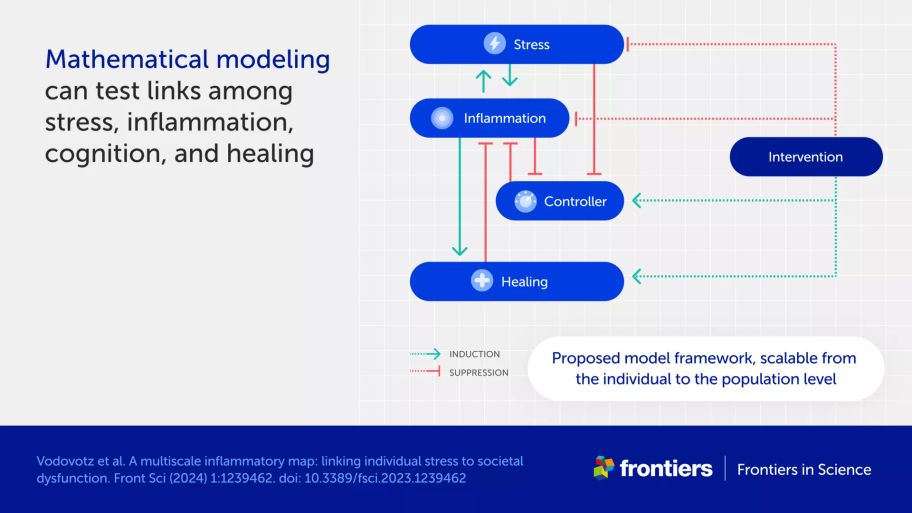

What insights can mathematical modeling give on stress transmission and control?

Mathematical models allow researchers to tease apart different components of complex systems and simulate the effect of various inputs. The model developed by the authors can be applied at both the individual and societal level. It focuses on five key variables driving the inflammatory stress cycle:

the level of stress

the level of inflammation

the effect of controllers (factors that prevent a dangerous inflammatory state)

the ability of the system to heal and restore normal function.

the effect of interventions designed to mitigate inflammatory stress, promote healing, and restore control.

While research is needed to validate the model’s assumptions, it serves as a useful starting point to examine interactions between these variables. One insight is that when high levels of stress spread between individuals, controllers become less effective in calming stress, and can even switch to actively deregulate the system. The authors interpret this tipping point to indicate harmful decision-making and irreversible societal dysfunction.

Why haven’t current levels of global stress already led to widespread societal disorder?

Various factors prevent a dangerous inflammatory state at the societal level, including norms, laws, and trust in institutions, science, and medicine. The authors suggest these controllers have amplified along with amplified stress, and so kept the system stable.

However, they also point out that societal norms and institutions are increasingly being questioned. The challenge they see is how to prevent a new adversarial era of instability caused by a combination of global stress and ecological collapse.

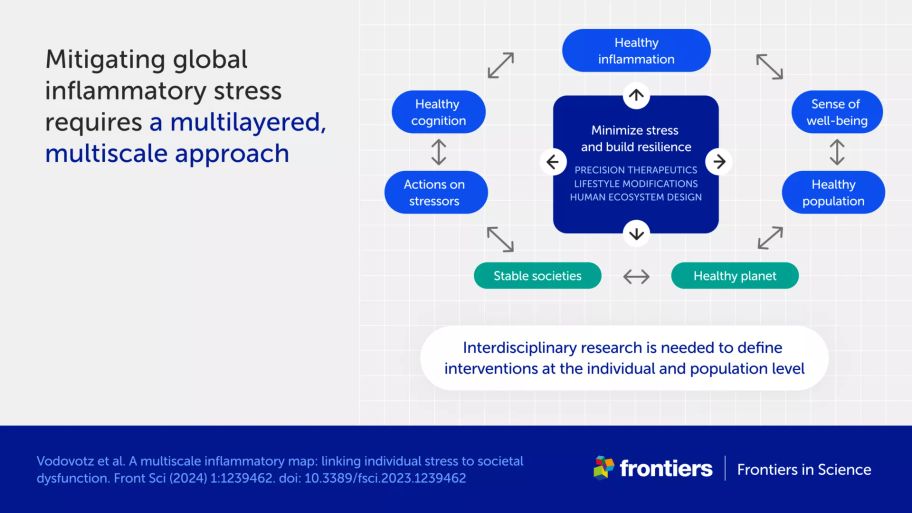

How can we reduce stress and inflammation in individuals and societies?

Although anti-inflammatory drugs are sometimes used to treat individuals with medical conditions associated with inflammation, the authors do not believe these are the answer to the problem of inflammatory stress—or at least not the whole answer.

Rather, the mathematical model suggests the need for a combination of interventions at multiple levels. For example, lifestyle changes such as healthy nutrition, exercise, and reducing exposure to stressful online content could be important. The authors also suggest a need to develop new therapies, including probiotics, drugs for depression that mitigate the associated inflammatory response, and interventions that modulate nerve activity.

This approach is consistent with a shift toward personalized medicine combining molecular profiling with bioinformatics and computational modeling. This transition is especially important in lifestyle medicine, where emerging technologies could address chronic inflammation in a highly personalized fashion.

At a broader level, constructing calm public spaces could help reduce stress, as could education on the roles of societal norms and regulations in mitigating the risk of societal inflammation.

Overall, the authors call for a coordinated and interdisciplinary research effort to understand the multiscale nature of stress and inform the development of interventions that improve both the lives of individuals and the resilience of communities to stress.