Immune-mediated disease caused by climate change-associated environmental hazards: mitigation and adaptation

Explainer

Front Sci, 04 April 2024

This explainer is part of an article hub, related to lead article https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2024.1279192

Climate change-related hazards damage our immune systems

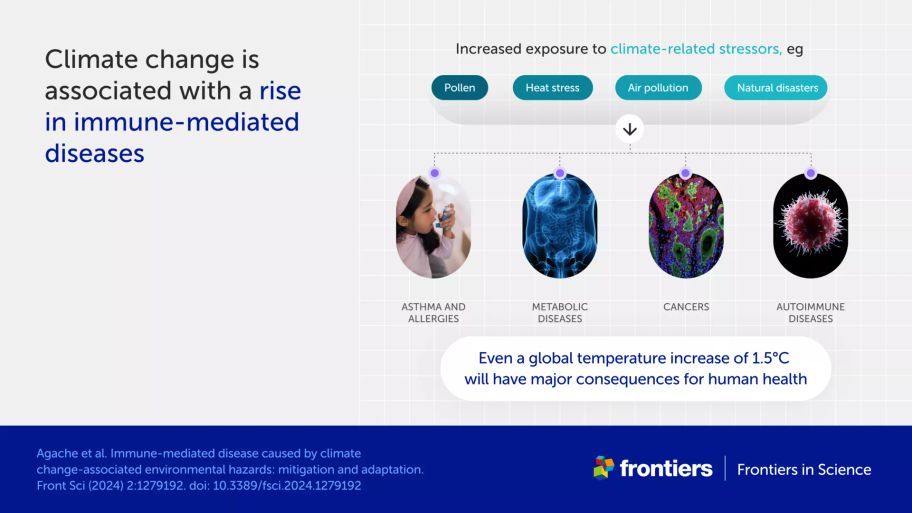

Rapid changes to our environment over the past few decades are worsening our health. Climate change, pollution, falling biodiversity, and urbanization are reducing the “positive” environmental exposures that help our immune systems to develop and work properly. At the same time, we are facing increasing “negative” exposures to hazards such as wildfire smoke and allergens such as pollen. Our bodies also increasingly face stressors like abnormally high temperatures. These changes are key drivers of recent rises in allergies, asthma, cancers, and other immune-mediated diseases—with the burden falling hardest on the world’s most vulnerable people.

Agache et al. document connections between planetary health and human health in their Frontiers in Science lead article. Noting that $1 spent on climate change mitigation saves around $3 on healthcare costs—and that a global temperature increase of even 1.5°C will have major consequences for human health—the authors also outline how we can better measure climate-related health impacts and call for global, equitable solutions.

This explainer summarizes links between our immune system, health, and the environment, and how actions to address climate change would also help reduce the disease burden and healthcare costs globally.

How are our immune systems, health, and environment connected?

Our immune systems develop over time, responding to everything in the environment that we’re exposed to—from the food we eat to the air we breathe. Exposure to a variety of microbes and chemicals in the environment helps the immune system learn what is dangerous and must be removed from the body, and what is harmless and can be ignored. If the immune system doesn’t receive these exposures, or if it’s exposed to pollutants such as particulate matter in the air, it can become dysregulated—and start to attack harmless substances like pollen and even the body’s own cells.

Toxic substances in air, water, and food can also damage our skin and the cells lining our guts and lungs, which form a protective barrier between the environment and the insides of our bodies. This damage allows allergens and microbes to penetrate our bodies more easily, resulting in a hyperactive immune response. Pollutants and other environmental factors can additionally disrupt “good” microbes living on and inside our bodies, which can further affect the immune system.

These different sources of immune dysregulation contribute to an increase in many immune-mediated diseases, including asthma, allergies, cancers, and autoimmune disorders. Individuals with lower socioeconomic status or pre-existing medical conditions are particularly at risk, as are the very young and the elderly.

How does climate change affect our health?

Rising global temperatures and resulting climate change impacts, such as extreme weather events and biodiversity loss, both contribute to and exacerbate immune-related diseases.

The authors describe several ways that climate change impacts can directly increase and worsen asthma, allergic disorders, and other diseases:

increases in pollen quantity, allergenicity, and season length due to rising temperatures, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels, and thunderstorm activity

widespread air pollution from wildfire smoke and sand and dust storms, with these events becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change

increases in household mold due to increased flooding and extreme rainfall, particularly in poorly weatherized homes

increased heat stress during heatwaves

reduced exposure to natural environments due to biodiversity loss.

Climate change additionally impacts wider environmental factors that can affect our health, such as access to nutritious food, clean drinking water, and secure shelter. Heatwaves can also indirectly affect health outcomes by disrupting power, water, and transport, and directly exacerbate other health issues such as cardiovascular disease and mental health conditions.

How can we reduce the health impacts of climate change?

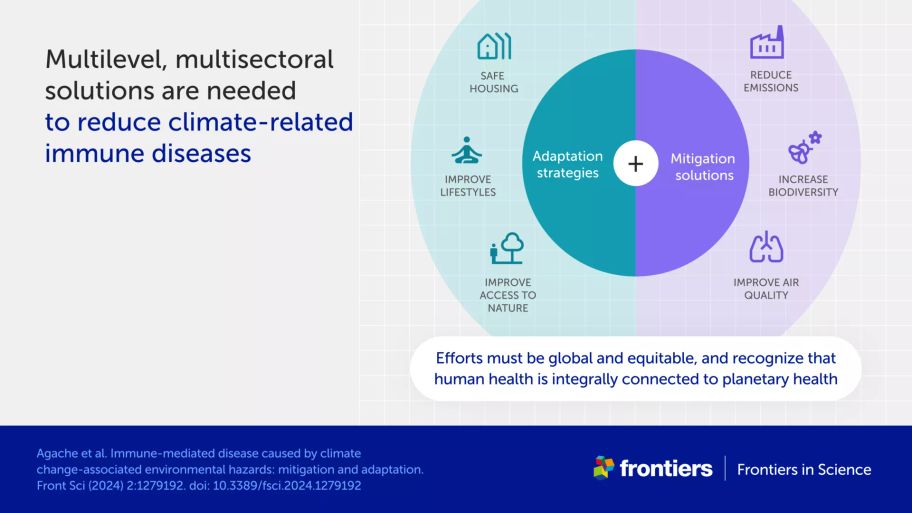

Agache et al. outline two approaches to minimize the effects of climate change on immune-mediated diseases.

Mitigation strategies aim to stop or slow climate change and related hazards, and include:

reducing greenhouse gas emissions

improving air quality

increasing biodiversity.

Adaptation strategies aim to reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts, and include:

providing safe housing that lowers exposure to air pollution and mold

ensuring food security, access to healthy foods, and diversity of food choices to reduce inflammation and support the development of a healthy immune system and microbiome

improving access to nature and green spaces, which also supports the development of a healthy immune system and microbiome.

The article summarizes evidence from many studies supporting the health benefits of such measures. Several show significant links between reduced air pollution and lower hospital admissions for asthma. Others show that diverse diets and ready access to green spaces lower the risk of asthma and allergy—with the latter also lowering mortality in adults and children. Modeling studies also provide evidence that improved housing quality would dramatically lower the number of asthma cases.

The authors emphasize that mitigation and adaptation efforts must:

include justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion to address existing socioeconomic and health disparities brought about by climate change

be global, spanning multiple sectors and disciplines and ensuring practices and policies for sustainable solutions are implemented at every level

be based on Planetary Health and One Health approaches, which consider the dependence of human health on the environment and natural ecosystems.

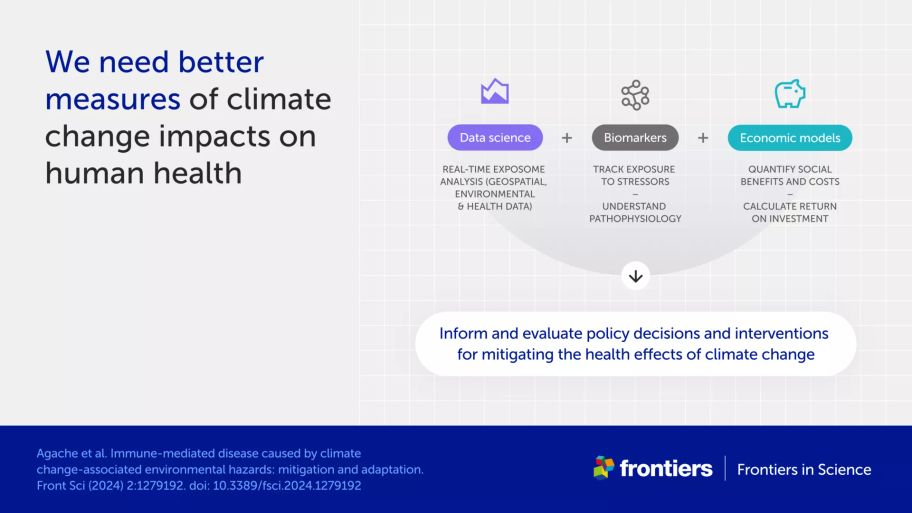

How can we better measure climate-change impacts on health?

Agache et al. propose three approaches to help measure the impact of climate change on immune health and disease:

big data analyses, artificial intelligence, and other data science methods to tease out the complex relationship between the immune system and climate change-related hazards

biomarkers which allow us to track exposure to air pollution and other environmental hazards

new economic models to quantify both the damage done already by the climate crisis and the expected benefits of mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The results of these measures would help inform policy decisions and evaluate their effectiveness.