- Diego Portales University, Santiago, Chile

Populism is a hot topic in academia. The causes of this phenomenon have received much attention with many studies focusing on the role of the high levels of unresponsiveness of mainstream parties in triggering a populist response. In this respect, in many cases, populist parties have become a relevant electoral force in the concomitance with an electoral decline of mainstream political options, mostly in the last decades. This article considers a situation in which the whole party system’s unresponsiveness reaches its zenith, and the party system collapses. A collapse is the result of the incapacity of most of the parties in the system to fulfill their basic function, i.e., to represent voters’ interests. When this happens, none of the types of linkages—programmatic, clientelist, or personalist—that tie parties and voters are effective. Empirical observation shows that in those cases populism can perform as a sort of representation linkage to re-connect parti(es) and voters on the basis of the moral distinction between “the people” and “the elite.” Through a discursive strategy of blame attribution, populistm can attract a large portion of the vote. At this point, its opposing ideology—anti-populism—also arouses. In other words, populism/anti-populism may result in a political cleavage that structures the party system by itself or, more frequently, with other cleavages. To elucidate this argument, the paper explores the case of Italy between 1994 and 2018. The electoral relevance of populist parties translated first into a discursive cleavage, which, in turn, changed the space of competition with the emergence of a new political axis, namely populism/anti-populism. This paper's central claim is that the dynamics of partisan competition cannot be understood by overlooking the populism/anti-populism political divide. The conclusion touches on one implication of the emergence of this political cleavage, namely change of the incentives for coalition building. In fact, when populism and anti-populism structure, at least partially, the party system changing the space of interparty competition, this in turn may affect the determinants behind parties’ coalition-building choices.

Introduction

Much has been written about the decline of support for traditional parties and the concomitant rise of populist and anti-establishment formations (Kriesi and Pappas, 2015; Hernández and Kriesi, 2016; Hobolt and Tilley, 2016). The main reason behind this electoral trend is the incapacity of mainstream parties to represent effectively the interests of voters. Parties are necessary for the functioning of modern democracies because of their capability to combine two crucial roles: representing their constituency and dealing with the governing functions of the polity (Mair, 2009 p. 5). However, parties have started to focus more on the latter leaving aside the task of representation, becoming somehow less responsive towards their constituencies.

When the level of unresponsiveness reaches its zenith, and none of the parties can provide adequate representation, party systems collapse. The collapse of an entire party system may represent a traumatic event for democracy (Morgan, 2011; Seawright, 2012). If linkages between parties and voters break down, voters are left without alternatives within the political system to ensure that their interests are being considered. In this precarious situation, populism, a thin ideology, function as an ideological shortcut and temporarily re-connect voters with (at least) one political actor. In this article, I argue that populism, in post-collapse contexts, may reconnect voters to a political actor for two reasons. First, as a ‘thin’ ideology, populism is not as complex as other “thick” or “host” ideologies such as nativism, socialism, or producerism (Mudde, 2004). As Stanley (2008) p. 99 pointed out, a comprehensive, “full” ideology contains particular interpretations and configurations of all the major political concepts attached to a general plan of public policy that a specific society requires (see also Freeden, 1998). This complexity makes thick ideologies difficult to employ by political actors who are looking to re-establish a connection with voters. Conversely, thin ideologies “are those whose morphological structure is restricted to a set of core concepts which alone are unable “to provide a reasonably broad, if not comprehensive, range of answers to the political questions that societies generate” (Stanley, 2008: 99; see also; Freeden, 1998). In this sense, populism relies on two ideas to connect with voters. One is that society is divided into two antagonistic, homogeneous, and morally defined groups, “the people” and “the elite.” The other is that politics should be the expression of the people’s general will (see Mudde, 2007; Mudde, 2017).

The second reason why populism manages to attract an electorally relevant portion of voters in post-collapse situations is linked to its Manicheist and moral view of society and politics. In fact, political actors can plausibly use blame attribution to reproach mainstream parties of being “all the same,” holding them responsible for the country’s situation (Zanotti, 2019). It is patent that, in a situation in which voters do not feel represented by any of the parties in the system, this discourse has good chances of attracting broad portions of the electorate. However, party systems that experienced a collapse witnessed not only the emergence of electorally relevant populist actors, but they also witnessed how populism (and anti-populism) came to partially structure the political space as a political cleavage (Ostiguy, 2009; Pappas, 2014; Stavrakakis, 2014; Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, 2019). In other words, a new dimension of political competition based on the contraposition between populism and anti-populism emerged in post-collapse contexts. The emergence of this new divide is relevant because partisan politics cannot be fully understood without considering all the dimensions of the political space (Lipset and Rokkan, 1967).

The case of Italy illustrates this argument. After the party system collapsed in 1994, a new actor with a populist discourse entered the system (Tarchi, 2008). Silvio Berlusconi is a media tycoon who, just eight months ahead of the election, formed a political party, Forza Italia (Go Italy!). In its first election, the party gained 25 percent of the vote and entered government as the leader of a right-wing coalition with another populist party the Lega Nord (Northern League), among others. The 1994 general election inaugurated a period in Italian politics known as “berlusconismo” (berlusconism). During this period, which lasted until 2011, the populist pole of the cleavage emerged while the dynamic of competition revolved around the figure of Silvio Berlusconi. This contraposition based on personalism hindered the programmatic development of both the populist and non-populist side. After the Great Recession, which affected Southern Europe as a public debt crisis, two phenomena took place. On the one hand, the composition of the populist pole changed with the entrance of the Five Star Movement and the change of ideology of the Northern League (now the League). On the other hand, the anti-populist pole appeared as one of the main features of the elitist discourse of Mario Monti’s technocratic cabinet and, since 2014 of the Democratic Party leader Matteo Renzi.

The article is structured as follows. The first section analyzes how extreme levels of unresponsiveness lead to the collapse of an entire party system. The second section observes the role of populism in reconstructing representation linkages in post-collapse environments. The third section addresses the Italian case during 1994–2011 and 2011–2018. Finally, in the conclusion, I present the main findings of this study and the future research agenda.

Unresponsiveness, Representation, and the Collapse of the Party System

Parties are essential for democracy. Schattschneider (1942) claimed that “democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.” On the same line, Max Weber stated that political parties are ‘the children of democracy, of mass franchise, of the necessity to woo and organize the masses’ (1946 p. 102). In other words, political parties are necessary for democracy’s survival because they link government to its voters, representing the latter’s interests and ideology in the former. As Dalton et al. (2011) observe, party government is synonymous with representative democracy (2011a, p. 3).

It is important to note that the functions that parties fulfill are numerous and they have to do with different phases of the electoral process. According to Diamond and Gunther (2001) (p.7–8) parties’ main functions are 1) candidate nomination; 2) electoral mobilization; 3) issue structuring; 4) societal representation; 5) interest aggregation; 6) forming and sustaining government and lastly, they perform a 7) social integration role (see also Sartori, 2005). However, not every party performs all these roles or puts the same emphasis on achieving them. With respect to this very point, Mair (2009) pointed out that in contemporary democracies it appears to be more and more difficult for parties to fulfill both those functions that have to do with the representation of voters’ interests and those related to the coordination of the governing institutions. Due to different reasons parties have transferred their gravitational center from the society to the state, moving from a combination of representative and governing roles to a strengthening of their governing role (Katz and Mair, 1995). The reasons behind this shift are linked to “the decline of the traditional large collective constituencies, the fragmentation of electorates, the particularization of voter preferences, together with the volatility of issue preferences and alignment that made it more and more difficult for parties to read interests, let alone aggregate them within coherent electoral programs” (Mair, 2009, p. 6). All in all, it has become more and more difficult for parties to be at the same time responsive to their constituencies and responsible for fulfilling their governmental tasks. A corollary of this argument is that representation has become increasingly a matter of non-partisan actors such as non-governing organizations, interest groups, and social movements, just to mention some. As Mair maintains, representation became either ‘an activity realized through a sort of de-politicized pluralism’ or, when it remains within the electoral realm, it is channeled by the so-called “niche” or “challenger” parties (2009 p. 6).

When unresponsiveness reaches its zenith and involves all the main parties in the system, we are in presence of a collapse of the party system (Morgan, 2011; Seawright, 2012). In these cases “major parties no longer attract enough support to maintain an electoral coalition capable of winning control of the state and lose their reason for existence as they become empty vessels without a base of support” (Morgan, 2009 p. 4). If all the main parties in the system cannot fulfill one of their key roles—representation—it means that the majority of voters are not effectively represented (Morgan, 2011). With respect to this point, it is worth noting that representation can be fulfilled through different types of linkages such as the programmatic, charismatic, and clientelist, as described by Kitschelt (2000). This means that the symptoms of unresponsiveness can be different depending on the characteristics of the polity. Even if different parties are connected to their constituencies with different types of linkages, in general terms one of these linkages is predominant. As Morgan pointed out (2011) when this specific linkage—whichever it may be—breaks down and a secondary one fails to replace it, the entire party system collapses.

It is worth underlining that while different factors can lead to the collapse, all these factors are related to the lack of responsiveness of the main parties. In fact, even in the case of external shocks, such as economic crises, the governmental response more than the crisis per se contribute to the intensification of the level of unresponsiveness. A clear example is the Great Recession in Southern European countries. In those countries, protests and electoral punishment to incumbents were related to the adoption of neoliberal measures to counterattack the crisis instead of the effects on the crisis itself (see Rovira Kaltwasser and Zanotti, 2018).

All in all, once the party system collapses, the cleavages that previously structured the system unfreezes, and a dramatic change is possible. While the causes of this phenomenon have been thoroughly studied, less has been said on the possible consequences of such a traumatic event. In terms of historical institutionalism, the party system’s collapse entails a critical juncture that lowers the institutional barriers for new actors to enter the system. Critical junctures has been defined as “brief phases of institutional flux during which more dramatic change is possible” (Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007, 341; Pierson, 2000). In other words, the collapse opens a political opportunity structure, which relaxes the institutional boundaries, and, in turn, facilitates the emergence of other political options (Zanotti, 2019).

The next section is dedicated to explaining the emergence of the populism/anti-populism political divide in post-collapse contexts.

There’s Life After the Collapse: Populism and Anti/Populism as a Political Divide

As mentioned before, parties are essential for democracy since they connect political elites with voters through different kinds of linkages. Therefore, it is understandable that the collapse of an entire party system indeed may represent a devastating occurrence for democracy. What happens with representation in a post-collapse situation? This is a relevant question since one could think that after such a traumatic event, the system is doomed to chaos and volatility. In fact, if one looks at Peru (between 1989 and 1992) and Venezuela (between 1998 and 2000), democratic breakdowns followed the party system collapse.

If representation linkages cease to connect voters and parties, little room exists for those same parties to successfully re-build linkages with the former, mainly because both institutions and parties are highly discredited. However, as Roberts pointed out, “[t]his does not necessarily imply that the collapse of party systems is a direct cause of the democratic breakdown.” Also, the aftermath of a party system collapse does necessarily entail instability. For example, in a post-partisan collapse situation, when old cleavages cease to articulate the partisan confrontation, party politics literature underlines that personalism is very likely to ensue (Morgan, 2011). The proliferation of personalism occurs because “individuals tend to believe that personal leaderships are more efficient than organized political parties” (Meléndez, 2019, p. 25). Moreover, these leaders also tend to develop a populist discourse, polarizing polities between those in favor and those against them. How do we explain that? In other words, what makes populism a more suitable form of representation linkage in post-collapse contexts?

To answer this question, we must first define populism.

Populism, to some extent, is still a contested concept. However, lately the so-called ideational definition has become predominant (Mudde, 2004; Mudde, 2017). The ideational approach deals with one particular aspect of populists: their ideas. This approach unifies the definitions of populism as a thin ideology (Mudde, 2004), a frame (Aslanidis, 2016; Caiani and Della Porta, 2010), a discourse (Stavrakakakis, 2014), or a mode of identification (Panizza, 2005). Here, adopting Mudde’s characterization, I define populism as a “thin ideology that conceives society ultimately divided into two homogeneous groups the “pure” people vs. the “corrupt” elite, and which argues that politics should be the expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2012, Mudde, 2017).

Conceiving populism as a thin ideology means that, although of limited analytical use on its terms, it conveys a distinct set of ideas about politics that interact with the established ideational traditions of full ideologies (Stanley, 2008). This hints at the fact that populism is mostly associated with “thick” or “full” ideologies such as nativism, socialism, or producerism (Mudde, 2017). These “thick” ideologies constitute the programmatic platforms that link voters and parties (Kitschelt, 2000). For the purpose of this article, the complexity of thick ideologies is relevant because one can make the argument that, after a collapse of the party system, it may be easier for political entrepreneurs to re-build broken representation linkages through a populist discourse based solely on the (moral) contraposition between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite.” In these contexts, populism, a thin ideology, constitutes a more immediate way to re-connect with voters since it does not entail a complex ideological message. In other words, when representation linkages are entirely severed, populism represents the primary discourse used by political actors to construct a (thin) ideological connection with voters, while more complex ideologies initially having less importance. Other than the fact that populism is more suitable in contexts of extreme unresponsiveness due to its lack of ideological complexity, it is also worth noting that a populist discourse is functional for new actors to attract a relevant portion of the vote in contexts with high political discontent and disaffection. In other words, when traditional parties in the system fail to represent voters, the latter are more likely to prefer a new populist political option. In fact, through their morally polarizing discourse, populists present themselves as “pure” while at the same time, depicting the whole establishment as “corrupt” through a process known as blame attribution. In this sense, populist actors blame elites depicting them as “all the same” and holding them responsible for the dire circumstances of the country (Zanotti, 2019). The anti-establishment component of populism is central to the discourse of populist actors when they are trying to connect with the general electorate. That is why populism can be defined as a form of “direct representation” (Urbinati, 2015). To use Urbinati’s words “[t]he construction of the leader as representative of the true people occurs by means of his direct and permanent communication with the audience (which the new electronic media facilitate). It is the representative agent that is “direct” in its relation to the citizens; the populist leader bypasses intermediary associations, like parties and traditional media, and holds quotidian communication with “his people” in order to prove he is always identified with them and not a new establishment” (Urbinati, 2019, p. 120).

All in all, when the majority of voters feel unrepresented by any of the parties in the system, populist actors have an easier time persuading voters to cast a ballot for them.

When populist actors successfully attract a relevant portion of voters, populism and its counterpart, anti-populism become relevant in structuring the party system. Only a few studies analyze populism’s capacity to structure political competition in a specific party system (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, 2019; Ostiguy, 2009). More specifically, only a few of these studies examined populism and anti-populism as a political cleavage (Zanotti, 2019 p. 43). It is worth noting that, as pointed out by Stavrakakis and Katsambekis (2019), “while aspects of this antagonistic dialectic between populism and anti-populism have been occasionally discussed in the relevant literature (…) its real nature and implications have not been properly investigated.”

If populism is a contested concept, the same can be said of anti-populism (Moffitt, 2018). The first issue with anti-populism is that some degree of confusion still exists as to what populism entails. The second issue is more subtle but no less critical. Anti-populist ideology or discourse does not merely relate to the absence of the concept, populism. Anti-populism needs to be defined as a hostile ideology or discourse against populism and the worldwide this entails. In this sense, anti-populism shares with populism the dualistic distinction between the people and the elite. Notably, anti-populism shares with populism the Manicheist forma mentis characterized by the understanding of society and politics as an antagonistic dynamic between two groups (the people vs. the elite), which, in turn, entails a type of political competition based on an anti (instead of an alter) dynamic. Actors that employ an anti-populist discourse reject populism on the basis of the moral hierarchy (i.e., which group is entitled to be dominant). A clear example of anti-populism can be found in the discourse of technocratic governments. In fact, while technocrats share with populists the conception of society as dualistic, they oppose populism on the grounds that, according to populists, politics should be the expression of the general will of the people. By contrast, since they are by definition elitist, technocratic governments invert the logic of the populist discourse, maintaining that the elites should rule because “they know better” (Caramani, 2017).

At this point, it is essential to remember that a corollary of the ideational definition of populism is that different types of political actors can articulate populism. Overall, three types of populism mobilization can be identified: personal leadership, political parties, and social movements (Mudde, 2017, p. 42). This aspect affects not only the form of the populism/anti-populism cleavage, but also the future political system and democracy. When populism is incarnated by personal leadership without developing partisan referents, party systems are less likely to become institutionalized. After the collapse of the system, Venezuela and Peru experienced the emergence of an entirely new set of non-partisan electoral referents (Roberts, 2002 p. 12) which, on the one hand, created an immediate sort of stability by structuring the party around a person with limited ideological cornerstones (Meléndez, 2019), but on the other did not allow a stable pattern of inter-party competition to develop.

Looking at countries where populist leaders held power for an extended period, such as Argentina, Venezuela, or Bolivia, a new cleavage emerged between those for and those against the populist leaders. It is impossible to understand Argentinian politics without considering the Peronism/anti-Peronism divide or Venezuelan politics without the opposition between chavistas and anti-chavistas (Ellner, 1999). Even if these political cleavages have a strong personal component, they are also based on an anti-system discourse, which is typical of populism. In this sense populist leaders also are successful at mobilizing those with anti-system sentiments against those who somehow identifies with traditional actors (Handlin, 2017).

In the next section, I address the changes in the Italian party system between during the so-called Second Republic, focusing on the factors that led to the collapse of the party system in 1994 and to the emergence of the populist/anti-populist political cleavage.

The Populism/Anti-Populism Cleavage in Italian Politics (1994–2016)

The Populist Moment 1994–2011: From Berlusconism to the Great Recession

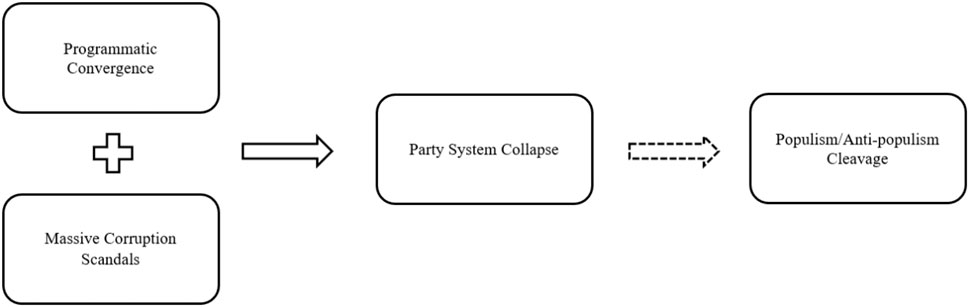

The extreme unresponsiveness that led the Italian party system to collapse in 1994 (see Morgan, 2011; Seawright, 2012) has two main causes. First, there was the increasing programmatic convergence of parties during most of the First Republic, reinforced by interparty pacts (see Morgan, 2011; Zanotti, 2019). Second, a massive corruption scandal and the subsequent judicial trial uncovered the broad scheme of corruption in the Italian political and entrepreneurial elite. These two phenomena caused the whole party system to reach extreme levels of unresponsiveness (see Katz and Mair, 1995) that undermined the linkages between voters and parties (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Determinants of the emergence of the populism/anti-populism cleavage in Italy. Source: Elaboration of the author based on Zanotti (2019).

It is important to notice that neither programmatic convergence nor massive corruption scandals are the only symptoms of unresponsiveness. However, in the Italian case, these were the two factors that combined led to the collpase, which, in turn, changed the political opportunity structure in a way that facilitated the emergence of electorally relevant populist options. The party system that emerged from the 1994 general election was deeply different from the one of the First Republic. The main novelty was the entrance of Forza Italia (FI) a party founded just eight months earlier by the entertainment tycoon Silvio Berlusconi (Diamanti, 2007). The ideology of Forza Italia has been described as neoliberal populism (Pauwels, 2010; Akkerman et al., 2014). Although neoliberalism populism is pretty unique in Western Europe, it is similar to the second wave of populism in Latin America, which gave rise to leaders such as Alberto Fujimori in Peru and Carlos Menem in Argentina (Roberts, 1995). In its first election FI obtained more than 20 percent of the vote share entering government as the leader of a center-right coalition1. The populist right-wing coalition competed also in 2001, 2006, and 2008. When observing the patterns of inter-party competition in Italy between 1994 and 2011, we find many similarities with those experienced in Latin American countries that also suffered a collapse of the party system. In Italy the competition assumed personalistic traits, revolving around the figure of Silvio Berlusconi marking an era known as “berlusconismo”. Berlusconi was the leader of the coalition’s biggest party and the man who managed to keep the coalition together and electorally successful for almost two decades. As in other post-collapse situations, the dynamic of the Italian party system’s competition was based on the success that Berlusconi achieved in re-building representation linkages with a portion of the voters both positively—with the ones in favor—and negatively—with the ones against. As mentioned above, this type of representation linkage results from both ideology and personal traits.

From the ideological point of view, as mentioned above, the host ideology associated with Berlusconi’s populist discourse was neoliberalism. However, concerning the policies implemented, Berlusconi behaved as an opportunistic political leader whose actions had little to do with what he said (Gualmini and Schmidt, 2013, p. 347). In other words, while Berlusconi’s discourse presented neoliberal features, the policies that his government implemented aimed at satisfying its leader’s interests.

All in all, the linkage through which FI connected to its voters was based on Berlusconi’s personal traits and—to a lesser extent—on programmatic ideas. Concerning this second point, populism served as a glue that allowed him to be perceived as an outsider, without being one (Carreras, 2013). In other words, it was populism, not neoliberalism, that allowed him to build a more immediate linkage with voters. It is worth noting that most of the individuals who voted for Berlusconi came from the Christian Democrats and the Socialists, the two parties that suffered the most from the Tangentopoli corruption scandal (Morgan, 2011) creating a space in the system for him to occupy.

With respect to the left parties, their critique toward critiqued center-right coalition was mostly on a personal plan. Anti-berlusconism focused mainly on the new style of leadership embodied by Berlusconi. In other words, Silvio Berlusconi, not his ideology, was the main polarizing element between 1994 and 2011. In this sense, at least in this first period after the collapse only the populist pole emerged. In fact, during this period, while anti-berlusconism was a constant, anti-populism was not clear and coherent (Verbeek and Zaslove, 2016).

All in all, during almost 20 years, Italian politics was based more on an anti instead of an alter dynamic of competition (De Giorgi and Ilonszki, 2018). This pattern continued until 2011 when the devastating effects of the Great Recession reached Italy.

2011 represented a turning point for many reasons. First, the Great Recession put an end to the fourth Berlusconi government in November. In mid-2011, the European Union started to demand tough economic reforms from Italy. However, disagreements within the government coalition, mainly with the Northern League over which economic measures to adopt (especially those pertaining to pension reform), made it impossible for the government to meet the EU’s requests. In this context, EU institutions, international financial institutions (IFIs), and European leaders strongly supported former EU Commissioner Mario Monti’s appointment over a cabinet reshuffle. This may seem quite contradictory given the neoliberal features of Berlusconi’s populist discourse. However, despite his discourse, Berlusconi’s four administrations were not characterized by the implementation of neoliberal economic policies. As Gualmini and Schmidt argue, “Italy’s trajectory since the postwar years has gone back and forth between normal periods of non-liberal political leadership—in which what opportunistic political leaders said had little to do with what they did—and crisis periods of neo-liberal technocratic leadership, in which pragmatic leaders neo-liberal words matched the actions” (2013 p. 347).

This further underlines the argument that structural conditions somehow constrain political actors to prefer a populist linkage while downplaying “thick” ideologies in contexts of extreme unresponsiveness.

Elitism and the Emergence of the Anti-populist Pole in Italy (2011–2016)

Even if there is no clear causal linkage between economic crises and the emergence of populist alternatives, the former can represent a sort of “fertile soil” for the emergence of populist actors (Rama and Zanotti, 2020). Concerning the Great Recession, the effects of the debt crisis and the policy convergence of most parties towards neoliberal economic measures produced discontent and angst among voters. As Mair (2009) pointed out, the increasing tension between responsibility and responsiveness eroded the mainstream parties’ representation (see also Zanotti, 2019). This convergence can be framed as a lack of responsiveness of mainstream parties to voters’ specific demands, making the latter feel unrepresented and more likely to prefer a political alternative that distances itself from the (morally) “corrupt” party system (Mair, 2009; Mair, 2013). In other words, even if the economic crisis is not necessarily causally linked to the rise of populism, it can be interpreted as a critical juncture (Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007). This tension was evident when governments face huge constraints to confronting technocratic international institutions such as the Troika2which pushed for fiscal consolidation (Rovira Kaltwasser and Zanotti, 2018, p. 540).

In Italy, austerity measures triggered what can be described as a populist reaction after a period dominated by the elitist anti-populism of the technocratic government. The rise of populist political options like the M5S can be seen as the result of both the malfunctioning of the representative democracy regarding political parties, i.e., the tension between responsiveness and responsibility, and the aftereffect of the Great Recession and the neo-liberal adjustment measures implemented by Monti’s technocratic government (Zanotti, 2019). The M5S, a political movement founded by comedian Beppe Grillo and web strategist Gianalberto Casaleggio in 2009, from the ideological point of view, is almost unanimously defined as populist (Bordignon and Ceccarini, 2013). First, the Manichean worldview, which sees a division between the “pure” people and the “corrupt” elite, is present both in the party manifesto of 2013 and in the public speeches given by Grillo and the party’s main actors. The ‘pure’ people in the M5S’s worldview are represented by those Italians who have suffered the consequences of the economic stabilization measures implemented by the technocratic government but also, more generally, the average Italian who feels that traditional parties and the classic left-right axis lost respectively their capacity to represent the voters and their significance. Simultaneously, the “corrupt” elite comprises two categories, referred to by the leader as casts: the whole political system and the media. Also, the M5S was able to capture the widespread anti-politics sentiment in Italian society not only towards politicians, but also towards state institutions (Chiapponi et al., 2014). First, the M5S’s attacks were directed at professional politicians who are allegedly interested only in defending their privileges and their connections to the country’s economic elite (Bordignon and Ceccarini, 2013). However, professional politicians were not the only actors the party critiqued. Political institutions, without exception, were firmly blamed for the country’s situation. When looking at what subtype of populism the Movement falls under, the M5S proves to be quite peculiar. Given that, as mentioned above, it is difficult to identify the “host ideology” with which populism is associated (Pirro and Van Kessel, 2018). Generally, placing the Movement on the left-right axis has proven difficult given the variety of issues supported by the M5S, some of them shared with the radical right and some close to the positions of the radical left. Verbeek and Zaslove (2015: 307) referring to the party leader, Beppe Grillo mentioned that “although he often takes positions that could be classified as right wing, we label the M5S as a populist left-libertarian movement that combines a populist, anti-elitist discourse and environmentalism with left-wing economics (that is, opposition to “multinationals”)” (see also Corbetta and Vignati, 2013).

Besides the rise of the Five Star Movement, another noteworthy feature of this period was the partial estrangement of Silvio Berlusconi, who became a secondary figure, at least electorally. The attacks leveled in Italy and Europe on the country’s disastrous economy and internal disagreements over possible solutions, coupled with the judiciary scandals that enveloped Berlusconi, drove him away from political life. Without its leader, FI began to weaken, especially after the 2013 election, when the leader left aside the populist discourse. The decline of Forza Italia, which had been the “glue” of the Italian right for more than twenty years, started a process of fragmentation on the right (Zanotti, 2019). Another transformation within the right was the League’s (former Northern League) transition from a populist regionalist party to a radical right party (Zaslove, 2011; Albertazzi et al., 2018). Decisive in this transition was leadership change, with Matteo Salvini’s election as the party’s secretary in 2013.

Finally, while between 1994 and 2011 the anti-populist pole had not appeared, between 2011 and 2016 it clearly emerged. In detail, it expresses itself through the elitism of Monti’s technocratic government and the PD-led coalition that had Matteo Renzi as Prime Minister. As Verbeek and Zaslove pointed out, anti-populism in Italy during this period ‘face[d] an enemy with many different faces, who [were] united in their rejection of traditional party elitism in Italy.’

Renzi’s government was the fourth-longest in Italy’s postwar history. His government counted with the parliamentary support of the PD, Scelta Civica, and Nuovo Centro Destra—a Forza Italia spinoff. The first reform bills that Renzi launched concerned the electoral law, the elimination of bicameralism, and a reform of the education system (Pasquino, 2016). The PD’s discourse expressed both in its electoral manifesto and its leaders’ public speeches manifested a clear anti-populist stance. The first paragraph of the manifesto ends with, “our objective is to defeat every form of populism”3. Moreover, the attack seems to be directed at a specific form of populism, the populism inhabiting the right end of the spectrum: “the populist right promised an illusionary protection from the effect of the financier liberalism building cultural, territorial and, in some cases, xenophobic barriers” (p.4). The PD’s manifesto contraposes democracy to rightist populism to maintain that, “the only response to populism is democratic participation. Today’s crisis of democracy needs to be fought with more democracy not less. More respect for the rules, a clear separation among powers” (p.4).

Renzi’s and Monti’s anti-populist discourses based on a Manichean vision of society contributed for sure to a moralization of the country’s political debate. This moralization reached its zenith during the electoral campaign for the Constitutional referendum of December 2016 through the categorization of populist actors as “evil” and “dangerous for the society” and, at the same time, the depiction of those who were in favor of the “yes” in the constitutional referendum as some sort of nation-saviors. The anti-populist discourse emphasized the alleged moral corruption of the political elite. For example, two days before the referendum, during a speech in Florence, the Prime Minister maintained that those in favor of the referendum “are the ones that love Italy and its institutions” (speech in Florence December 2, 2016). During a pro-referendum demonstration in Piazza del Popolo (Square of the People) in Rome, Renzi started his speech with a direct attack on populist forces: “this square belongs to the people, not to populists.” Then, during the speech, Renzi attacked all the parties opposing the referendum, including Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, the Lega Nord, and the M5S, implying that the referendum was a “fight” between the populists and responsible actors (Zanotti, 2019). The confrontation between the “yes” and “no” was exceptionally heightened during the last months before the referendum. The tension was also exacerbated by the campaigns of the representatives of the EU’s political institutions and the leaders of the EU’s most powerful countries for the “yes” faction. Those who were worried about the country’s political instability and the fact that populist parties would come to power campaigned for the “no.” Consequently, the antagonism and the depiction of politics as a moral issue worsened, with the two factions presenting themselves as the ones interested in Italy’s well-being and accusing the other faction of self-interested myopia.

Conclusions and Future Research Agenda

When political unresponsiveness reaches its extreme level, party systems collapse. This means that in the voters’ eyes, the whole system can no longer represent their ideology and interests. This representation bankruptcy (Morgan, 2011) leads to a situation in which ties between voters and parties no longer exist. In these contexts, populism can act as a short-term representation linkage due to its thin ideology features as well as the credibility of its anti-establishment and moral worldview. Indeed, populists’ Manichean vision of both politics and society and their discourse of blame attribution towards the whole political class for not acting in the people’s interest, has excellent chances of being effective in attracting relevant portions of the electorate. Indeed, this discourse resonates with those voters who feel unrepresented by the whole party system that proved to be unresponsive. This article goes beyond the causes of the emergence of populism, maintaining that in contexts of extreme unresponsiveness, populism, and its counterpart anti-populism, may constitute a political cleavage that structures the party system and—at least partially—conditions the determinants of coalition building. The case of Italy illustrates this argument. After the party system’s collapse in 1994, the populist/anti-populist and the classic socio-economic cleavage came to structure the system. First, during the 1994–2011 period, the populist pole based on the contraposition between those in favor and those against Silvio Berlusconi emerged. In this sense the anti-populist discourse was not coherent among non-populist parties since the polarizing agent in the party system was the figure of Silvio Berlusconi and, to a lesser extent, his ideology.

Things changed between 2011 and 2013, where populism was pushed back by anti-populism. Indeed, the fully technocratic cabinet led by Mario Monti, which was supported by most parties (except for the Northern League), was characterized by a robust anti-populist stance. However anti-populism during this period was also present in the discourse of the main leftist party, the PD, especially under the leadership of Matteo Renzi. From 2013 to 2018, populism flourished again with the emergence of the Five Star Movement and the electoral upsurge of the League (former Northern League). This populist moment culminated in the coalition government of 2018 between the League and the Five Star Movement, two parties that were not close on the left-right axis but on the populist/anti-populist one. Pre-electoral polls for the 2018 general election indicated a highly uncertain outcome. The three leading contenders were the center-right coalition, the center-left coalition led by the Democratic Party, and the Five Star Movement. As Chiaramonte and his collaborators pointed out, the uncertainty was due to a new electoral law, the very high percentage of undecided voters, and the competitiveness of the main political groupings (2018, p. 479). The results confirmed the predictions. The center-right coalition won but did not gain the majority of the seats. While the M5S was a close second, the PD only obtained 22 percent of the national vote. The two parties that gained substantially with respect to the prior election were the M5S and the League, which received about 50 percent of total votes. The great success of populist parties was accompanied by the historical defeat of the two mainstream center-left and center-right parties (PD and FI), which together lost more than 5 million votes compared to the 2013 election (Chiaramonte et al., 2018).

The 2018 electoral results changed radically—once again—the Italian political party system. The continuity elements are the consolidation of the tripolar pattern of competition and the stabilization of the party system fragmentation. The effective number of parties has remained stable at around five, which seems low in comparison to the extremely high number of parties seen in the 1990s, but also seems high when looking at the quasi-two-party system witnessed in the 2008 general election—when the newly founded PDL and PD collected more than 70 percent of votes (Chiaramonte et al., 2018, p. 493). The coalition that was formed almost 3 months after the election saw the two populist parties--the League and the Five Star Movement--in power. This is partially a novelty for Italian politics. As we mentioned earlier it happened before that two populist powers have been (intermittently) in government together. However, in 2018 the two populist parties were not close on the left-right axis of competition. Moreover, the two mainstream parties—currently the PD and FI—were both in opposition for the first time since 1994. Finally, the impact of the emergence of the populism/anti-populism cleavage on the quality of democracy needs to be more thoroughly studied. The main reason is the fact that populism entails a moral division of politics and society between the “good people” and the “corrupt elite.” Categorizing one group as good while the other is not, means that one is legitimate the other is not. To use Urbinati’s (2019) words populism constitutes the glorification of one part, and this can have deleterious consequences for democracy since it entails a sort of moral polarization that extends beyond policy differences.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/78561.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges support from Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT Project 3210352). Also, the author acknowledges the editors, the reviewers as well as Laura Gamboa, Jana Morgan and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser for the valuable comments to previous versions of this article.

Footnotes

1In the snap election of 1996, the Northern League compete outside the center-right coalition.

2The name Troika referred to the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.

3Available at https://www.repubblica.it/economia/2018/02/12/news/il_programma_del_partito_democratico_costi_e_coperture-188623142/

References

Akkerman, A., Mudde, C., and Zaslove, A. (2014). How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47 (9), 1324–1353. doi:10.1177/0010414013512600

Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., and Seddone, A. (2018). 'No Regionalism Please, We Are Leghisti !' the Transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the Leadership of Matteo Salvini. Reg. Fed. Stud. 28 (5), 645–671. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

Aslanidis, P. (2016). ‘Is Populism an Ideology? A Refutation and a New Perspective. Polit. Stud. 64 (Suppl. l), 88–104. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12224

Bordignon, F., and Ceccarini, L. (2013). Five Stars and a Cricket. Beppe Grillo Shakes Italian Politics. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 18 (4), 427–449. doi:10.1080/13608746.2013.775720

Caiani, M., and Della Porta, D. (2010). Extreme Right and Populism: A Frame Analysis of Extreme Right Wing Discourses in Italy and Germany. IHS Political Science Series 121. Working paper. Available at: https://irihs.ihs.ac.at/id/eprint/2004/1/pw_121.pdf.

Capoccia, G., and Kelemen, R. D. (2007). The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism. World Pol. 59 (3), 341–369. doi:10.1017/s0043887100020852

Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. Reason: The Populist and Technocratic Forms of Political Representation and Their Critique to Party Government. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111 (1), 54–67. doi:10.1017/s0003055416000538

Carreras, M. (2013). Presidentes outsiders y ministros neófitos: un análisis a través del ejemplo de Fujimori. Am. Lat. Hoy. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 64, 95–118. doi:10.14201/alh.10244

Chiapponi, F., Cremonesi, C., and Legnante, G. (2014). “Parties and Electoral Behaviour in Italy: Parties and Electoral Behaviour in Italy: From Stability to Competition,” in Italy and Japan: How Similar Are They? Editors S. Beretta, A. Berkofsky, and F. Rugge (Milano: Springer), 105–120. doi:10.1007/978-88-470-2568-4_7‘

Chiaramonte, A., Emanuele, V., Maggini, N., and Paparo, A. (2018). Populist success in a Hung Parliament: The 2018 General Election in Italy. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 23 (4), 479–501. doi:10.1080/13608746.2018.1506513

Corbetta, P., and Vignati, R. (2013). Left or Right? the Complex Nature and Uncertain Future of the Five Star Movement. Ital. Polit. Soc. 72 (73), 53–62. Avaliable at http://web.apsanet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2016/01/72-73-Spring-Fall-2013.pdf#page=53

Dalton, R., Farrell, D., and McAllister, I. (2011). Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199599356.001.0001

De Giorgi, E., and Ilonszki, G. (2018). Opposition Parties in European Legislatures: Conflict or Consensus? London: Routledge.

Diamanti, I. (2007). The Italian centre-right and centre-left: Between Parties and 'the Party'. West Eur. Polit. 30 (4), 733–762. doi:10.1080/01402380701500272

L. Diamond, and R. Gunther (Editor) (2001). Political Parties and Democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ellner, S. (1999). “The Heyday or Radical Populism in Venezuela and its Aftermath,” in Populism in Latin America. Editor M. L. Conniff (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press), 117–137.

Freeden, M. (1998). Is Nationalism a Distinct Ideology? Polit. Stud. 46 (4), 748–765. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00165

Gualmini, E., and Schmidt, V. (2013). “State Transformation in Italy and France: Technocratic versus Political Leadership on the Road from Non-liberalism to neo-liberalism.’,” in Resilient Liberalism in Europe's Political Economy. Editors V. Schmidt, and M. Thatcher (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 346–373.

Handlin, S. (2017). State Crisis in Fragile Democracies: Polarization and Political Regimes in South America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108233682

Hernández, E., and Kriesi, H. (2016). The Electoral Consequences of the Financial and Economic Crisis in Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55 (2), 203–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12122

Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2016). Fleeing the centre: the Rise of Challenger Parties in the Aftermath of the Euro Crisis. West Eur. Polit. 39 (5), 971–991. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

S. Lipset, and S. Rokkan (Editor) (1967). Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (1995). Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy. Party Polit. 1 (1), 5–28. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001

Kitschelt, H. (2000). Linkages between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities. Comp. Polit. Stud. 33 (6-7), 845–879. doi:10.1177/001041400003300607

H. Kriesi, and T. Pappas (Editor) (2015). European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Mair, P. (2009). ‘Representative versus Responsible Government.’ MPIfG Working Paper 09/08. Available at: http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2010/2121/ (Accessed May 27, 2021). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199230952.003.0016

Meléndez, C. (2019). El mal menor: Vínculos políticos en el Perú posterior al colapso del sistema de partidos. Lima:Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Moffitt, B. (2018). The Populism/anti-Populism divide in Western Europe. Democratic Theor. 5 (2), 1–16. doi:10.3167/dt.2018.050202

Morgan, J. (2011). Bankrupt Representation and Party System Collapse. Penn State Press: University Park. doi:10.5325/j.ctv14gp7gg

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C. (2004). The Populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 39 (4), 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Ostiguy, P. (2009). The High and the Low in Politics: A Two-Dimensional Political Space for Comparative Analysis and Electoral StudiesKellogg InstituteAvailable at: http://www3.nd.edu/∼kellogg/publications/workingpapers/WPS/360.pdf (Accessed June 3, 2021).

Pappas, T. (2014). Populism and Crisis Politics in Greece. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137410580

Pasquino, G. (2016). Renzi: the Government, the Party, the Future of Italian Politics. J. Mod. Ital. Stud. 21 (3), 389–398. doi:10.1080/1354571x.2016.1169883

Pauwels, T. (2010). Explaining the Success of Neo-Liberal Populist Parties: The Case of Lijst Dedecker in Belgium. Polit. Stud. 58 (5), 1009–1029. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00815.x

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 94 (2), 251–267. doi:10.2307/2586011

Pirro, A. L., and van Kessel, S. (2018). Populist Eurosceptic Trajectories in Italy and the Netherlands during the European Crises. Politics 38 (3), 327–343. doi:10.1177/0263395718769511

Rama, J., and Zanotti, L. (2020). ¿Quiénes cambiaron de partido durante la Gran Recesión? Un estudio de 12 países de Europa Occidental. Rev. Int. Sociol. 78 (3), 164. doi:10.3989/ris.2020.78.3.19.015

Roberts, K. M. (1995). Neoliberalism and the Transformation of Populism in Latin America: The Peruvian Case. World Pol. 48, 82–116. doi:10.1353/wp.1995.0004

Roberts, K. M. (2002). Party-society Linkages and Democratic Representation in Latin America. Can. J. Latin Am. Caribbean Stud. 27 (53), 9–34. doi:10.1080/08263663.2002.10816813

Rovira Kaltwasser, C., and Zanotti, L. (2018). The Comparative (Party) Politics of the Great Recession: Causes, Consequences and Future Research Agenda. Comp. Eur. Polit. 16 (3), 535–548. doi:10.1057/cep.2016.22

Schattschneider, E. (1942). Party Government. American Government in Action. New York: Rinehart & Company.

Seawright, J. (2012). Party-System Collapse: The Roots of Crisis in Peru and Venezuela. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804782364.001.0001

Stanley, B. (2008). The Thin Ideology of Populism. J. Polit. Ideologies 13 (1), 95–110. doi:10.1080/13569310701822289

Stavrakakis, Y., and Katsambekis, G. (2019). ‘The Populism/Anti-Populism Frontier and its Mediation in Crisis-Ridden Greece: From Discursive Divide to Emerging Cleavage?’. Eur. Polit. Sci. 18, 37–52. doi:10.1057/s41304-017-0138-3

Stavrakakis, Y. (2014). The Return of "the People": Populism and Anti-populism in the Shadow of the European Crisis. Constellations 21 (4), 505–517. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12127

Tarchi, M. (2008). Italy: A Country of many PopulismsTwenty-first century populism. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 84–99. doi:10.1057/9780230592100_6

Urbinati, N. (2015). A Revolt against Intermediary Bodies. Constellations 22 (4), 477–486. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12188

Urbinati, N. (2019). Political Theory of Populism. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 111–127. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070753

Verbeek, B., and Zaslove, A. (2016). Italy: a Case of Mutating Populism? Democratization 23 (2), 304–323. doi:10.1080/13510347.2015.1076213

Zanotti, L. (2019). Populist Polarization in Italian Politics, 1994-2016: an Assessment from a Latin American Analytical Perspective. Doctoral Dissertation. Available at: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/78561 (Accessed May 27, 2021).

Keywords: populism, anti-populism, polarization, cleavages, Italy, representation

Citation: Zanotti L (2021) How’s Life After the Collapse? Populism as a Representation Linkage and the Emergence of a Populist/Anti-Populist Political Divide in Italy (1994–2018). Front. Polit. Sci. 3:679968. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.679968

Received: 12 March 2021; Accepted: 23 June 2021;

Published: 06 July 2021.

Edited by:

José Rama, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Bruno Castanho Silva, University of Cologne, GermanyZsolt Enyedi, Central European University, Hungary

Copyright © 2021 Zanotti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa Zanotti, lisa.zanotti@mail.udp.cl

Lisa Zanotti

Lisa Zanotti