- 1Institute of Geographical Sciences, Department of Earth Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Institut für ökologische Wirtschaftsforschung, Berlin, Germany

This paper examines the prevailing interpretation patterns and action orientations regarding climate change and climate protection among the young generation (14–22 years) in Germany. Based on a representative survey, we investigate which climate action options are currently favored and widespread among young individuals in Germany, encompassing both private sphere behavior—sustainable consumption—and public sphere behavior—collective climate action and civic engagement. Subsequently, through qualitative interviews, we delve into the shared interpretation patterns that young individuals draw upon to comprehend, evaluate, and guide their actions in climate protection. In this process, an individualizing and a politicizing interpretation pattern are identified and juxtaposed. As a result, both the representative survey and the qualitative analysis underscore a deep-rooted and widespread adoption of the individualizing rationale among young people in interpreting and acting on climate change. We discuss this finding by exploring the discursive origins of the dominant interpretation pattern and by questioning the respective transformative potential of both the individualizing and the politicizing action orientation.

1 Introduction

Social mobilization for climate protection has reached unprecedented magnitudes in recent years. Particularly, collective actors such as Extinction Rebellion, Ende Gelände, and, most notably, the global network of Fridays for Future (FFF) garnered public attention. The fact that these climate group's protests were primarily initiated and driven by young individuals was a defining characteristic from the outset (Sommer et al., 2019; Wahlström et al., 2019). In Germany, the demonstrations of the FFF movement became swiftly emblematic of a new generation conscious of climate issues and politically engaged—a “Generation Greta” (Hurrelmann and Albrecht, 2020). More recently, various acts of civil disobedience by youth-driven alliances like Die letzte Generation [The Last Generation] sparked public discussions, not only on the climate issue, but also on the acceptability of protest forms. In light of these developments, the inference of a politicization of youth—at least in matters of climate protection—seems plausible (Lee et al., 2022). However, the extent to which the climate-related thinking and actions of an entire generation have actually been politicized so far remains uncertain.

The public climate discourse of past decades has been dominated by the notion of the “responsible consumer” (Maniates, 2001; Fleming et al., 2014; Grunwald, 2018; Mock, 2020). Also, the environmental and climate policies of recent governments have been characterized by measures in the realm of “sustainable consumption” (e.g., National Programme on Sustainable Consumption, Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, 2018) and a distinct assignment of responsibility to private households (Akenji, 2014). The promotion of “green consumerism” and individual responsibilities was disseminated by the media landscape and corporate communications (Supran and Oreskes, 2021), as well as by actors in education for sustainable development (Kehren, 2017). This bias in political, educational, and economic institutions and the related call for pro-environmental “private-sphere behaviors” (Stern, 2000, p. 410) is referred to as privatization (e.g., Grunwald, 2010) or individualization (e.g., Maniates, 2001).

As multiple crises, including climate change, continue to escalate, scholars and policymakers increasingly acknowledge the limitations of the consumer scope of action in effectively addressing these crises. Instead, they underscore the necessity for a profound societal transformation (e.g., Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Globale Umweltveränderungen, 2011; Brand, 2016; IPCC, 2018; Dörre et al., 2019; Nightingale et al., 2020). For individuals, this means they need to take action not only on their roles as consumers by reducing their ecological impact, but also through their civic and political engagement, for example, as workers, citizens, activists, or politicians (Amel et al., 2017; Wullenkord and Hamann, 2021). In contrast to individual consumption behavior, these behavioral aspects have been described as public sphere behavior (Stern, 2000) or collective action (Fritsche et al., 2018). Civic organizations like Germanwatch coined the concept of the ecological “handprint” to highlight the importance of these climate actions. Unlike the carbon footprint, which measures individual environmental impact through consumption, the handprint signifies the positive influence of collective action and political engagement in changing unfavorable structures and conditions (Hayward et al., 2012; Reif and Heitfeld, 2015). Also, many actors of the young climate movement emphasize that political measures should not be directed at individual consumption choices, but rather should address the underlying political and economic structures. Central to their transformational efforts is the principle of climate justice, which entails an equitable distribution of environmental costs, benefits, and democratic participation (Della Porta and Parks, 2014; de Moor et al., 2021b; Knappe and Renn, 2022). This critique of hegemonic approaches to climate change, the recognition of systemic barriers to sustainable lifestyles that need to be addressed through political action, and the call for democratic processes to negotiate these actions, can been seen as a form of politicization. In general terms, politicization is understood as the process of discursively placing a particular subject within a sphere of political contestation, democratic decision-making and agency, instead of portraying it as “devoid of power, conflict and decision” (Kenis, 2021, p. 136, see also Swyngedouw, 2013; Kenis and Lievens, 2014; Pepermans and Maeseele, 2016; Knappe and Renn, 2022; Marquardt and Lederer, 2022).

Thus, a tension between individualizing and politicizing narratives becomes evident, which increasingly characterizes the climate discourse. Previous research has not yet adequately considered how these discursive dynamics manifest in climate-related attitudes and behaviors among young individuals (Reuter and Gossen, 2021). Young people are highly receptive to new influences and ideas during their transition to adulthood (Sloam et al., 2022), which likely makes them also susceptible to the discursive dynamics mentioned above. Moreover, it is widely recognized that young people and future generations will be much more affected by the impacts of climate change than today's adults, and as future decision-makers, they will be tasked with addressing and solving these challenges (Wallis and Loy, 2021). As both a driving force for current climate action and a seismograph for future responses to climate change, the study of climate-related interpretation patterns and action orientations among young people is of particular importance.

Several youth studies indicate a generally high awareness of climate change and underscore that climate protection is a significant concern for a large portion of the young generation (Albert et al., 2019; Calmbach et al., 2020; TUI Stiftung, 2021; Bartels et al., 2022). Also, the behavioral intentions of young individuals in climate protection have been extensively examined. The focus has primarily been on the conditions of “private-sphere behaviors” (Stern, 2000, p. 410), encompassing everyday individual actions aimed at reducing the personal environmental impact through energy-saving measures or conscious consumption (e.g., Busch et al., 2019). With the growth of the young climate movement in recent years, studies have increasingly turned their attention to the composition, practices, and motivations of “public-sphere environmentalism” (Stern, 2000, p. 401) and collective action (Fritsche et al., 2018) among youth, involving political and activist activities like participating in petitions, demonstrations, or blockades, as well as engaging with climate NGOs or political parties (e.g., Wahlström et al., 2019; Brügger et al., 2020; Haugestad et al., 2021; Wallis and Loy, 2021; Neas et al., 2022; Sloam et al., 2022). Furthermore, several framing analyses within social movement research have examined the meaning-making processes of young climate groups, particularly the FFF (Sommer et al., 2020; de Moor et al., 2021b). However, within these fields of research, the influence of prevailing climate change narratives on the shared knowledge structures and action orientations across youth as a whole (including those who are not overtly involved in climate action) is seldom considered in theoretical terms and scarcely explored empirically. Particularly, the question of how the aforementioned tension between individualizing and politicizing positions in the climate discourse materializes in how young people think and act in response to climate change remains unaddressed so far.

To operationalize how young people think about climate change mitigation, we introduce the concept of social interpretation patterns1 (Oevermann, 2001; Plaß and Schetsche, 2001; Bögelein and Vetter, 2019; Ullrich, 2019; Reuter, 2021). The fundamental premise of this approach posits that individuals do not interpret things purely subjectively from their internal standpoint, but always refer to pre-existing, socially established structures of meaning. Interpretation patterns are to be understood as part of these societal meaning structures: they represent collectively shared bundles of knowledge that provide a certain range of explanations for a particular phenomenon (e.g., climate change)—that is, an internally coherent arrangement of problem definitions, evaluations, attributions of relevance, and causal explanations (Oevermann, 2001, p. 37; Bögelein and Vetter, 2019, p. 12). In a highly complex world, interpretation patterns serve as a kind of “sorting grid” (Kassner, 2003, p. 37), guiding individuals in their understanding, judgment, and—this is pivotal—also in their actions. This implies that interpretation patterns—according to their specific situational definitions, problem assessments, and prioritizations—suggest certain action options as necessary, feasible, functional, and legitimate, while simultaneously excluding other courses of action as inconceivable, irrelevant, or illegitimate. In this sense, they are never determining but can indeed become effective in guiding action (Oevermann, 2001, p. 45; Bögelein and Vetter, 2019, p. 15; Ullrich, 2019, p. 7f.). To operationalize how young people tend to act to mitigate climate change, we use the term action orientation, which is commonly used in connection with the concept of interpretation patterns. The notion reflects the idea that actions are neither based solely on rational choices nor determined by social structures, but are oriented by collective knowledge repertoires, including interpretation patterns (Ullrich, 2019, p. 8–10).

The emergence and dissemination of interpretation patterns can be explained by their embedding within societal discourses. According to Schetsche and Schmied-Knittel (2013, p. 32), it is the prevailing cultural discourses that generate, modify, and provide interpretation patterns. Discourses can thus be understood as “production sites” of interpretation patterns (Keller, 2007, p. 221). Conversely, interpretation patterns serve as a kind of intermediary concept on the meso level, bridging the gap between discourse (macro level) and the individual subject (micro level; Plaß and Schetsche, 2001, p. 512; Bögelein and Vetter, 2019, p. 15). Therefore, the analysis of interpretation patterns offers a suitable approach to investigate how socially circulating climate protection narratives, such as the individualizing and politicizing narratives, become relevant in everyday life and are reflected in the thinking and behavior at the individual level.

To gain deeper insights into young people's interpretation patterns and action orientations in the face of climate change, our research questions cover two levels. Firstly, we aim to ascertain the prevalence and popularity of climate protection actions among young individuals in Germany, to unveil the degree to which these behaviors and attitudes can be characterized as either individualized (through the prevalence and popularity of private sphere behavior) or politicized (through the prevalence and popularity of public sphere behavior).

Research question 1: To what extent do young people engage in sustainable consumption behaviors (private sphere) and civic engagement or collective action (public sphere), and how do they evaluate these behaviors in terms of effectiveness, effort, and attractiveness?

Subsequently, we delve into the common interpretation patterns young individuals draw upon to understand, evaluate, and guide their actions concerning climate change and climate protection. In this context, we aim to explore how both the prevailing individualizing discourse surrounding climate change, and the politicizing narratives of the climate movement are reflected in the shared interpretation patterns, and how this influences the action orientations.

Research question 2: What interpretation patterns do young individuals in Germany employ when reflecting on climate protection, and how do these patterns influence the range of potential courses of action they derive?

2 Materials and methods

We chose a mixed-methods approach to answer the research questions (Kuckartz, 2014), including a quantitative representative survey and qualitative interviews. The representative survey allows conclusions to be drawn about action orientations in the overall population of young people in Germany. The results of the representative survey are used to operationalize action orientations by the prevalence and evaluation of climate protection-related behaviors among the younger generation in Germany (research question 1). The in-depth interview analysis of interpretation patterns allows a deeper understanding of why and how these action orientations are held by young individuals. The interview material is used to identify the shared interpretation patterns employed by young individuals in shaping their understanding of climate protection as well as their associated action orientations (research question 2). Both, the representative survey with 1,010 young respondents and the interview study with 34 young individuals were conducted as part of the study “Zukunft? Jugend fragen! 2021” (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz and Umweltbundesamt, 2022; see Frick et al., 2023 for a detailed description of the data collection). For the interpretation pattern analysis, we make use of the findings of a master's thesis (Reuter, 2021) that was written in conjunction with the above-mentioned youth study “Zukunft? Jugend fragen! 2021.”

2.1 Quantitative representative survey

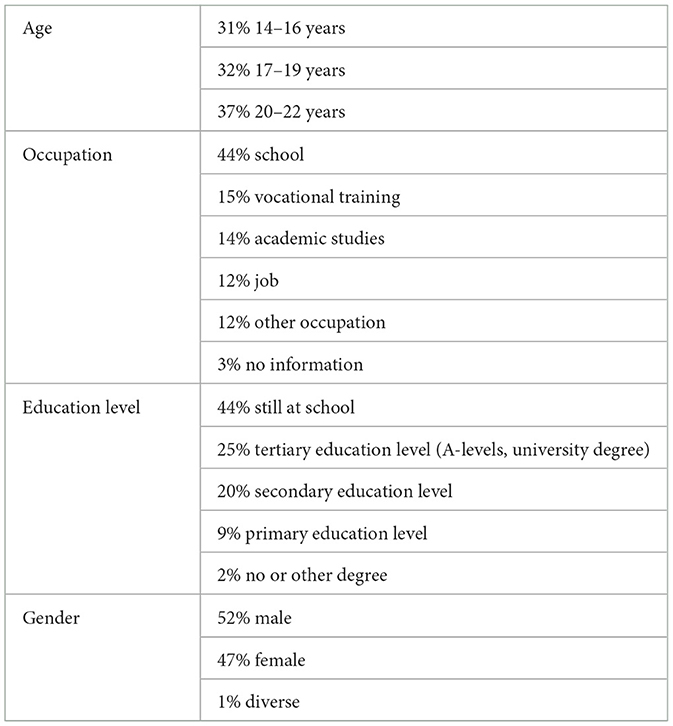

In the representative survey, 1,010 young people between the ages of 14 and 22 filled out an online questionnaire in June and July 2021. The survey lasted an average of 25 min. The representativeness was additionally ensured by a subsequent weighting. Comparative data from the German Federal Statistical Office on the sociodemographic composition of the German population was used for this weighting. The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

The questionnaire included multiple questions on different environmental topics such as environmental concern, civic engagement, or social media impact on environmental attitudes and behavior (see also Frick et al., 2023). The measures relevant to the publication at hand included the prevalence or frequency of private and public sphere pro-environmental behavior as well as the rating of these behaviors concerning attractiveness, effort and effectiveness, and the evaluation whether societal actors in Germany are doing enough for environmental and climate protection. The frequency of private and public sphere behavior was measured by nine items each on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “very often,” with the additional option of stating “I don't know this.” To assess the attractiveness, effort, and effectiveness of the behaviors, participants were asked to choose their top three behaviors for each category, e.g., “which behavior is in our opinion the most effective?” For the evaluation of societal actors, participants were asked whether the actors were doing enough for environmental and climate protection, which they could evaluate on a 4-point Likert scale from “enough” to “not enough” with the option “I don't know.”

2.2 Analysis of interpretation patterns in duo interviews

The primary objective of this analysis was to reconstruct the interpretation patterns concerning climate change, climate protection, and climate action that are shared by young individuals and reflected in their language. The empirical data utilized to identify these patterns of interpretation were derived from interviews conducted as part of the youth study (Frick et al., 2023) and covered two main topics: “Social Media and Environmental Protection” and “Youth Engagement in Environmental and Climate Protection.” They were carried out online via a video conferencing tool during the spring of 2021 and involved a total of 34 participants. The interviews were conducted in pairs, with the participants being friends, schoolmates, or couples. This kind of duo interview was chosen to create an easy conversational atmosphere and encourage young people to open up in the unfamiliar interview setting (Frick et al., 2023, p. 31–32).

To ensure the broadest possible representation of the study cohort, individuals were recruited with varying ages (14–22 years), gender (19 female, 15 male), and educational qualifications. Furthermore, the selection process aimed to encompass both “environmentally conscious” and “environmentally passive” young people in roughly equal proportions (Frick et al., 2023, p. 31f.), and thus countered a bias in qualitative research of primarily focusing on groups that are already engaged in climate action (Feldman, 2022). This systematic recruitment approach is crucial, as a diverse study group increases the likelihood of obtaining interview material that exhibits a wide range of perspectives. Consequently, during the evaluation process, it becomes possible to uncover an array of interpretation patterns that are as varied and representative of the field as possible (Kelle and Kluge, 2010, p. 52–55).

Based on all the individual statements collected during the duo interviews, encompassing opinions, evaluations, and justifications on the topic of climate change and climate action, the objective was to identify the underlying interpretation rules in a methodically controlled manner and reconstruct them in their patterned nature. The approach used in this study follows the methodology proposed by Kelle and Kluge (2010) and Ullrich (2019) can be simplified into three steps (see Reuter, 2021, p. 42–51 for detailed description).

Firstly, a preliminary coding of the complete interview data was conducted, employing a combined inductive and deductive approach (Kelle and Kluge, 2010, p. 62, 69–72; Ullrich, 2019, p. 131–132). The categories were derived initially (albeit provisionally) from the theoretical frameworks encompassing the multidimensional structure of interpretation patterns2 (Plaß and Schetsche, 2001, p. 528–530; Bögelein and Vetter, 2019, p. 27). Utilizing the theory-based assumptions about the inner dimensions of interpretation patterns as sensitizing concepts ensured a comprehensive exploration of the material, reducing the risk of overlooking any component of the patterns. Based on the interview material, these theoretically informed categories were then revised and substantiated with empirical content. The aim of this coding process was to cluster those textual segments that address a common referential phenomenon (such as climate change or climate protection) and belong to the same dimension within an interpretation pattern (such as problem definition or causal attribution).3

The second step entailed a contrastive interpretation of the thematically similar text passages, which had been grouped together in the initial phase. The objective here was to discern empirical regularities among individual statements and derive what are referred to as rules of interpretation. This process involved comparing, differentiating, and summarizing the meaning of text passages that related to a common reference phenomenon, and condensing them to shared rules of interpretation.

In the final step, the patterns of interpretation were reconstructed. In doing so, the previously identified rules of interpretation were systematically scrutinized for potential meaningful interconnections, establishing relationships based on their inherent logical structures. The outcome of this process eventually culminated in the crystallization of coherent interpretation patterns.

3 Results

The following sections present the results of the mixed-methods approach. Firstly, the quantitative survey section illustrates representative frequencies of reported behaviors in climate protection and their corresponding evaluations. Subsequently, the qualitative analysis delves deeper into the nature of the underlying interpretation patterns.

3.1 Representative results on young people's action orientations in the face of climate change

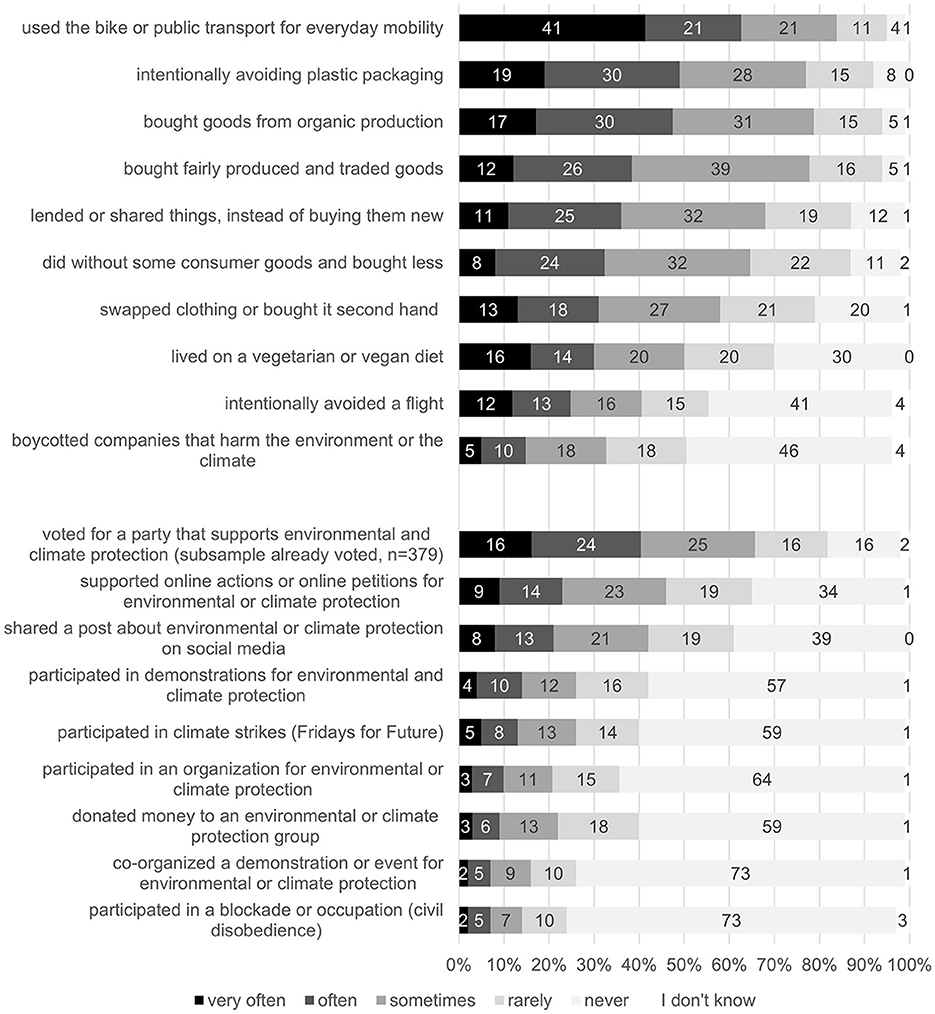

To address research question 1, the representative survey first covered the frequency of private and public sphere behavior for environmental and climate protection. Figure 1 shows that young people report to engage more frequently in private sphere behavior than in different forms of engagement. Sustainable consumption is much more integrated into young people's everyday lives. In particular, the use of public transport or bicycles, as well as so-called “green” consumption—i.e., the purchase of more sustainable products, for example, with an organic label, Fairtrade seal or without plastic packaging—are frequent. On the one hand, this difference is due to the fact that there are usually simply more opportunities for sustainable consumption and mobility behavior in everyday life than opportunities to participate in demonstrations or to sign petitions. But on the other hand, consumer behavior also seems to be more accepted and habituated beyond this. This can be seen from the proportion of people who have never tried a behavior, which is also higher for public than private sphere behavior. In the domain of public sphere behavior, digital activism, such as signing online petitions or sharing posts for environmental and climate protection on social media, was reported most frequently. Over 20% of respondents did this (very) often, and over half had done so at some point. 13–14% of young people (very) often participated in environmental and climate demonstrations, such as Fridays for Future climate strikes, and about four out of ten young people participated in such a demonstration once. All other forms of engagement had been tried by significantly < of the respondents.

Figure 1. Self-reported frequency of private sphere und public sphere behaviors (N = 1,010). Question: There are many possibilities of what young people can do for environmental and climate protection. […] Have you ever done the following things, and if yes, how often?

A factor analysis was applied to find out whether the two behavioral domains of private and public sphere behavior were distinct. The analysis showed that the two behavioral domains cannot be separated. Further, there is a strong positive correlation between the mean values of the two domains (r = 0.51**, p < 0.001). A reliability analysis reveals that an overall indicator of all assessed behaviors that includes both sustainable consumption and engagement has a very high reliability of Cronbach's a = 0.88. Thus, the two behavioral domains are not clearly distinguishable: those who engage in the public sphere are also more likely to consume sustainably, indicating a combination of these action orientations among young people.

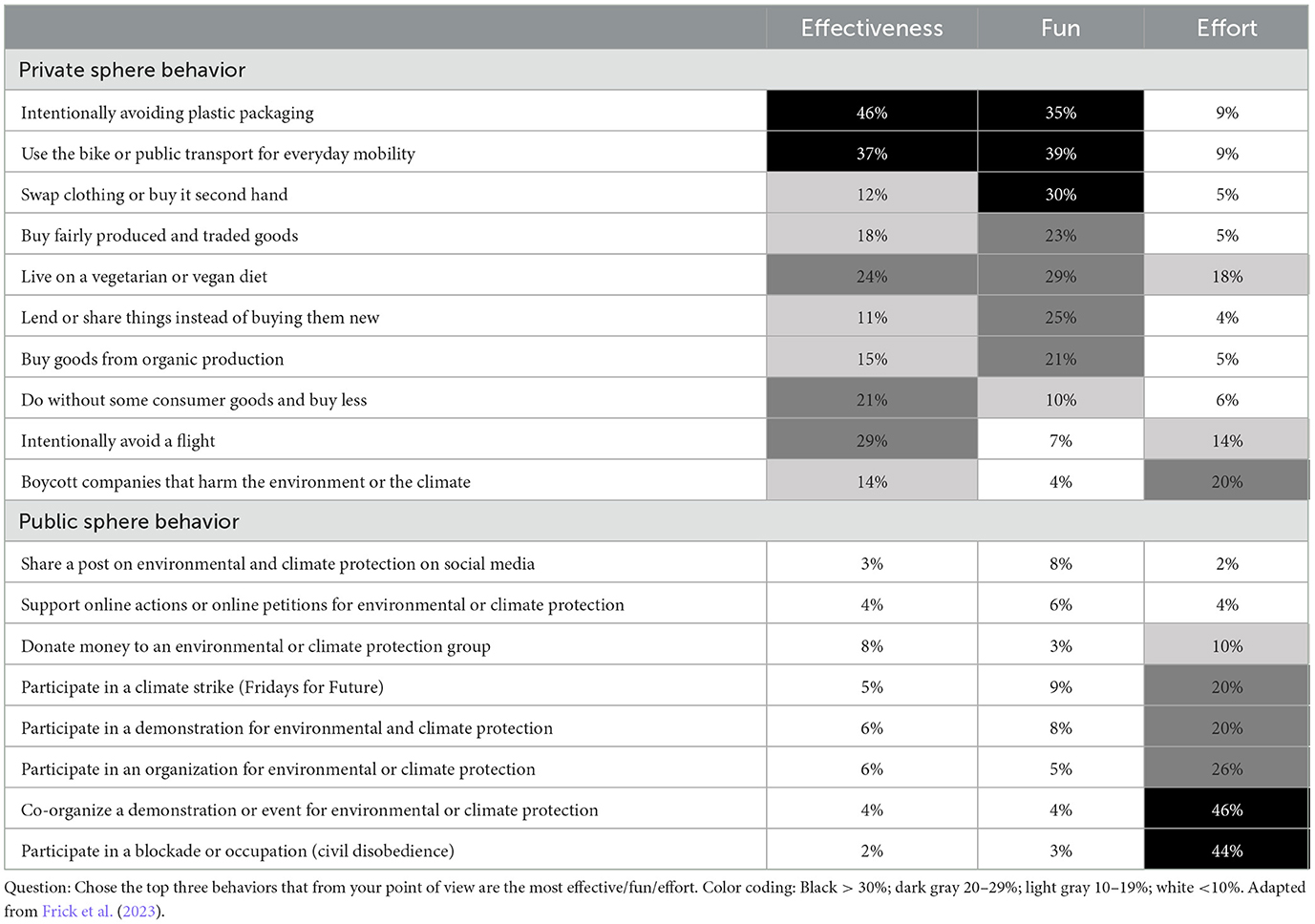

Various conditions may contribute to the fact that private sphere behaviors predominantly enjoyed greater popularity than civic engagement or public sphere behavior. Behavioral science research points to several key factors. The so-called outcome efficacy (Schwartz, 1977), i.e., the expected effectiveness of a behavior, shapes its prevalence and acceptance, as do hedonistic motives (how much fun it is) and the expected behavioral costs—i.e., the financial, time, and physical effort involved (Stern, 2000; Diekmann and Preisendörfer, 2003). Thus, the evaluation of these behaviors in terms of effectiveness, effort, and attractiveness was addressed (research question 1). Respondents were asked to select each of the three behaviors from the list in Figure 1, which was the most fun, most effective, and most costly. Table 2 shows the results: Sustainable consumption behaviors were more attractive for the majority of respondents, and they also associated them with less effort (with the exception of not flying and boycotting harmful companies). With the exception of digital activism (sharing posts and signing petitions) and donating money to environmental organizations, all forms of climate policy engagement were perceived to require significant effort.

Table 2. Perceived effectiveness, fun and effort of private and public sphere behavior (percentage of participants who chose the behavior in their top three voting).

What is more challenging to explain is the clear majority in favor of sustainable consumption as a more effective behavior compared to civic engagement. One possible explanation is that the effectiveness of one's own consumption behavior, such as foregoing a flight, reducing car kilometers, or meat consumption, is much easier to measure and appears to be more controllable, for example, by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The impact of civic engagement, on the other hand, can often only be tracked indirectly and over the long term, and is fulfilled primarily when people organize collectively, so the outcome cannot clearly be attributed to a single person's behavior.

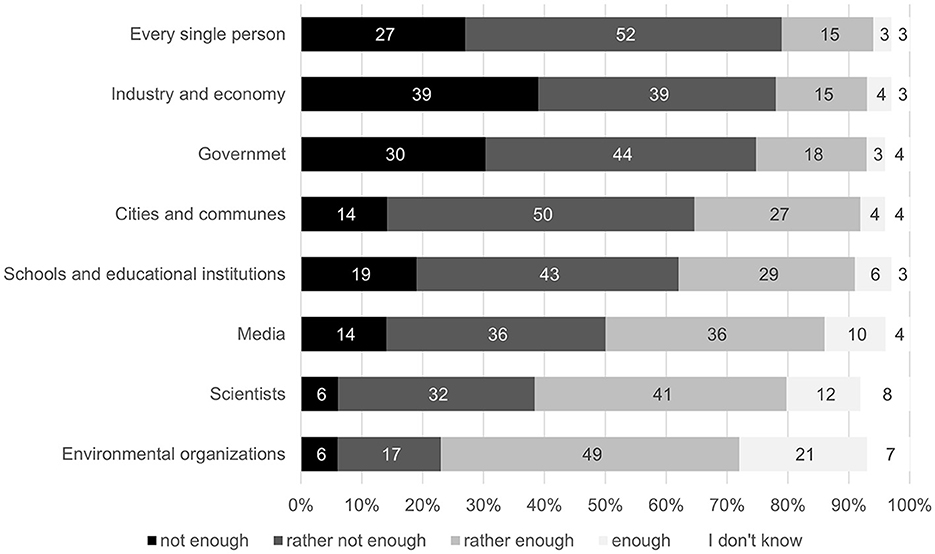

Finally, a third question in the survey asked respondents which actors they thought did (not) do enough for environmental and climate protection (Figure 2). “Each and every individual” scored lowest when it came to who does enough for environmental and climate protection (or similarly poorly as industry and government). This is indicative of the strong attribution of responsibility to the individual. However, the figure also makes it clear that young people do not see responsibility as lying solely with individuals: according to around two thirds of respondents, industry, and business in particular, but also political actors such as the federal government, cities, and municipalities, are (rather) not doing enough for environmental and climate protection. The extent to which these attributions of responsibility and the assessments of the effectiveness of various climate protection options are reflected in the young people's patterns of interpretation and orientations for action is explored in greater depth in the following chapter in the qualitative interview analysis.

Figure 2. Which actors do enough for environmental and climate protection (N = 1,010). Question: Do the following actors in Germany do enough for environmental and climate protection?

3.2 Young people's interpretation patterns in the face of climate change

The aim of the interview analysis was to uncover the shared patterns of interpretation that are accessed and reproduced by young people when thinking and talking about climate change and climate protection. It is assumed that these interpretation patterns, within their respective logical contexts, provide insights into the perceived significance, feasibility, desirability, and efficacy of various forms of climate protection behaviors. To address research question 2, this chapter outlines the interpretation patterns young individuals in Germany employ when reflecting on climate protection, and how these patterns influence the range of potential courses of action they derive.

The interview analysis revealed a multitude of interpretation rules concerning climate change and climate protection. One key observation is that, across all interviews, climate change was consistently interpreted as a serious problem, for which solutions need to be found. Beyond this general consensus on the issue of climate change, significant differences became apparent within the range of interpretation rules regarding causes of climate change, effective and legitimate solutions, and responsibility for implementation. Particularly, two opposing structural patterns, conceived as consistent configurations of interconnected interpretation rules, emerged. These two internally coherent patterns of interpretation can be characterized as individualizing and politicizing in nature, encompassing different dimensions: the framing of climate change and its causal explanations, viable approaches to climate protection, attributions of responsibility, and resulting implications for action. In all of these dimensions, the first interpretation pattern centers around the individual, his or her ecological awareness, personal consumption choices, and commitments to sustainable behavior in the private sphere. This first pattern is thus identifiable as individualizing. In contrast, the second pattern shifts the origin of problems, as well as solutions, responsibilities, and impetus for action, to a domain of systemic issues, political contestation, and collective action in the public sphere. Consequently, it can be defined as politicizing.

The following sections provide a concise summary of the two competing patterns of interpretation, delineating their distinct meanings and contrasting their underlying rationalities. As an illustration of both patterns, selected quotes from the interviews (translated into English by the authors) are included. To refer to a certain proportion of the 34 interviewees, we use the following labels: “no one” means 0 people, “few” means 1–4 people, “some” means 5–12 people, “many” means 13–22 people, “most/majority” means 23–33 people, “all” means 34 people.

3.2.1 “Doing small things makes a difference”—The individualizing interpretation pattern

The individualizing interpretation pattern revolved around the individual and their behaviors as central factors, regardless of whether it pertained to the causation of climate change issues, solution competence, attributions of responsibility, or practical implications for action. Climate change was problematized primarily as a result of climate-damaging lifestyle choices such as mobility habits, improper waste disposal, high meat consumption, excessive private energy use, purchases of unsustainable products, and frequent online orders. Consequently, the source of the problem was perceived as residing within individuals and their environmentally harmful consumption patterns. Many interviewees criticized other people for their supposed irresponsibility, citing laziness, selfishness, or ignorance as reasons for their environmentally harmful actions. For example, it was stated, that “one is not aware of what one is causing with some purchases or activities” (Duo#13), but also, “I believe that many people can't bring themselves to do it [act sustainably]. They know what's right, but still throw their trash on the street” (Duo#7).

Within this rationale, not only the problem but also the solutions to climate issues were rooted in individual behavior. Prominent strategies included conscious waste management, avoidance of plastic packaging, reduction of car and air travel, utilization of public transport, energy conservation, and the purchase of sustainable goods. An interviewee argued, “I try to limit my consumption a little when it comes to such things, [...] mostly small things. If everyone would pay attention to it, it would make a difference” (Duo#5), and somebody else claimed that “each individual should pay attention to what they can do, that not everything is wrapped in plastic at the supermarket, bring your own cloth bag, each person should take care of themselves, not selfishly walking through the world” (Duo#3). According to yet another interviewee, “there are small things in everyday life that everyone can do [...], turning off the car at traffic lights, not airing and heating at the same time, the classics that everyone knows, but often still does not implement. Anyone can do that” (Duo#10).

As a consequence, many interviewees viewed raising awareness and educating individuals about “correct” behaviors as crucial prerequisites for successful climate protection. Given these preconditions, it was believed that even minor everyday changes in individual behavior can lead to significant positive impacts. This was reflected in statements, such as “I think it will have a significant impact that more and more people are doing something small” (Duo#14), “Even doing small things is important, it definitely makes a difference” (Duo#8), or “When everything comes together, even if everyone does just a little thing, it can bring about a big change” (Duo#5). Therefore, the individualizing interpretation pattern underscored a clear appeal: each individual is responsible and should contribute to climate protection through adjustments in personal conduct, even if it is only “something small.” Such behavioral changes were not only deemed necessary and sensible but also morally imperative. Effective environmental and climate protection, according to this interpretation pattern, heavily relies on individuals' insight and willingness to adopt more sustainable consumption patterns and lifestyles. Here, the idea that sustainability could be attained if just everyone did the “small things that everyone can do” in the consumption sphere stands in stark contrast to scientific insights that call for drastic reductions in consumption patterns of the Global North (e.g., Wiedmann et al., 2020) as well as systemic societal and economic change (e.g., Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Globale Umweltveränderungen, 2011).

In contrast, the option of getting involved as a political citizen and engaging in collective climate action to foster systemic change was scarcely addressed within the individualizing logic (mostly when raised by the interviewers), and it was neither perceived as indispensable for climate protection nor regarded as morally required. Demonstrations, such as those organized by the FFF movement, were primarily interpreted as one of several possible means to communicate environmentally and climate-friendly behaviors. Compared to individual consumer behavior, however, it was not seen as an essential prerequisite for effectively addressing climate change. This prioritization was exemplified in the following statement: “I haven't really thought about it [getting involved in collective climate action]. I think if every person decides to care about the environment, ride a bicycle instead of a car, it benefits the community through a domino effect. I try to do it for myself, not extremely, like eating vegan, but choosing the environmentally friendly alternative for small decisions. Everyone has to contribute” (Duo#1). While many “carriers” of the individualizing pattern acknowledged a certain effectiveness of the climate movement's efforts, some others dismissed collective action as too extreme, hypocritical, or simply useless. One interviewee stated, “What was Fridays for Future? Nothing has changed. Nothing happened. The children took to the streets for a few months, you don't hear anything more from Greta Thunberg. After 6 months, nobody cares anymore” (#Duo15).

3.2.2 “Hope lies in the collective”—The politicizing interpretation pattern

The politicizing interpretation pattern operates at a structural-political level when defining both the problem of climate change and the typified paths toward climate protection as well as corresponding implications for action. Climate change was framed not solely as an ecological issue but as a socio-political problem. The root causes of climate change, such as other social challenges, were traced back to structural factors, mainly relating to the (capitalist) economic system and political framework conditions. For one interviewee this implied, “as long as this capitalist mode of production exists, climate change cannot be stopped” (Duo#17).

Within the politicizing logic, individual consumption decisions were not blamed for the problem, as it was believed that individuals have limited agency in making their behavior climate-friendly while living within a climate-damaging system. Structural barriers, such as inequitable distribution of financial resources, or political voice, were emphasized as hindrances to individual change and agency. Consequently, individual efforts to make everyday behaviors more climate-friendly were deemed insufficient as a solution to the problem. For example, one of the interviewees maintained that “people are educated, but about the wrong things. It's said that you drive your cars too much, you do this and that. Why isn't it mentioned that a supertanker traveling from India to Rotterdam consumes as much emissions as I do if I drive a car all year round? Why aren't we thinking in different dimensions?” (Duo#15) and somebody else stated that “small things don't change anything. The most important thing is that countries take action, close coal power plants, use more renewable energy, not criticize if you use plastic wrap” (Duo#9). The conviction was that fundamental societal transformation is necessary to address climate change effectively. The responsibility for implementing such changes and strengthening climate protection efforts was placed on political actors, who are called upon to take action: “I think that it's not sufficient. Something needs to happen in politics” (Duo#7), “One should intensify such measures; not enough is being done” (Duo#3), and “Angela Merkel [former German chancellor] can say that things should be abolished” (Duo#14).

Within this pattern, the moral obligation of individuals to strive for climate protection through sustainable consumption received much less emphasis, while for some interviewees, especially in the environmentally interested subgroup, collective climate action and political participation were seen as urgently needed and effective courses of action. This collective activism was considered to hold the potential for politicizing others, rallying public support for climate policy issues, and exerting pressure on political entities. In light of the profound societal changes deemed imperative, individual actions were perceived as constrained and politically inert, while collective engagement was viewed as a meaningful and urgent course of action. For instance, it was argued: “As an individual, I can't make much of a difference, but in a huge group, when there's a demonstration, it will have an impact” (Duo#13), or “Hope lies in the collective, finding people who think and feel the same, coming up with something together and being loud together” (Duo#17).

3.2.3 The interplay of the interpretation patterns and action orientations

The analysis revealed two distinct interpretation patterns young individuals in Germany draw on in the face of climate change—an individualizing and a politicizing pattern. The individualizing interpretation pattern was found to be far more dominant and intuitive in the majority of interviews, across all age groups, genders, educational backgrounds, as well as for individuals identified as both “environmentally conscious” and “environmentally passive” (Frick et al., 2023, p. 31–32). In contrast, the politicizing pattern was only infrequently reproduced, often in fragmented form, with vague references to the responsibility of “politics.”

When examining the individualizing and politicizing interpretation pattern, it is essential to keep in mind that these are ideal-typical, theoretical constructs that may not necessarily manifest empirically in the exact condensed forms described here (Pfister, 2002, p. 161). Also, the stark juxtaposition of both patterns is a simplified typification. Empirically, it can be observed that, in certain cases, elements from both interpretation patterns were combined, as some of the young participants drew on arguments from both the individualizing and the politicizing logic. This means that the interpretation patterns are not necessarily mutually exclusive but sometimes also appear in merged forms. Notably, the call for politicians to take responsibility for climate protection was repeatedly mentioned in combination with the individualizing rationale of “everyone has to make their contribution.” We also observed that a few interviewees referred to the responsibility of political and economic actors, but rather used it as an excuse for why they do not become active themselves. Overall, only a few interviewees referred exclusively to the politicizing interpretation pattern, while the majority referred to the individualizing pattern. Among the latter, some interviewees also occasionally reproduced isolated rules of interpretation from the politicizing pattern, although in general the individualizing elements still clearly dominated.

The convergence of the individualizing and politicizing rationale among some interviewees may be a sign of an ongoing process of change within the shared patterns of interpretation. It seems plausible that the growth of the climate movement in recent years has contributed to a (re)politicization of public debates and, as a result, also triggered changes in young people's interpretation patterns and action orientations. The observation in the interviews that some “carriers” of the individualizing pattern also took up elements of the politicizing pattern could be an indicator of this ongoing (re)politicization process.

Regarding the climate-related action orientations, it is crucial to reiterate that a direct causal linkage between interpretation patterns and action intentions, as determinants, cannot be established. Climate protection behaviors are undoubtedly influenced by various other factors that are not accounted for in the context of an interpretation pattern analysis. This implies that young people who adopt the politicizing interpretation pattern do not automatically participate in collective climate action but may be prevented from doing so for other reasons. Nonetheless, an action-orienting impact can reasonably be inferred, in the sense that, within the logic of a specific interpretation pattern, some options for action appear more rational and desirable than others (Oevermann, 2001, p. 45). It is thus plausible to assume that the politicizing interpretation pattern holds an activating potential for public sphere behaviors by presenting collective engagement in political climate actions as a necessary and legitimate course of action. On the other hand, the individualizing interpretation pattern highlights the effectiveness and the moral imperative of adapting everyday behaviors and making more conscious consumption choices, thus mobilizing individuals in the direction of private sphere behaviors.

Again, this does not mean that the interpretation patterns and action orientations are mutually exclusive. Rather, the interviews suggest that some individuals, particularly those (partially) aligned with the politicizing pattern, also aspire to a sustainable lifestyle and engage in private sphere behaviors—not exclusively, but in addition to public sphere behaviors. In line with this, the quantitative analysis in this study revealed a positive correlation between public and private sphere behaviors: individuals exhibiting civic engagement also tend to consume more sustainably. This tendency could be explained by the concept of behavioral spillovers, whereby the adoption of one pro-environmental behavior increases the likelihood of adopting other behaviors (Nash et al., 2017; Maki et al., 2019). However, the exact ways in which the individualizing and politicizing patterns are reconciled, and the extent to which both action orientations can mutually generate spillover effects, cannot be elaborated in this study, but should be explored in future research.

4 Discussion

The mixed-method approach of the study revealed a clear tendency toward the individualizing interpretation patterns and action orientations. While the analysis of interviews with 34 young individuals showed the detailed workings of the individualizing rationale, the quantitative survey allowed to draw generalized conclusions among the German youth population: It showed that young people in Germany engage more frequently in individual consumption-based behavior (private sphere behavior), perceive it as more effective, and generally find it more enjoyable and less burdensome than civic engagement or public sphere behavior (see also Bartels and Karic, 2023). The individualizing interpretation pattern was far more frequent across all age groups, genders, and educational backgrounds than the politicizing pattern. Overall, both the interview analysis and the representative survey underscore a deep-rooted and widespread adoption of the individualizing logic among young individuals when interpreting or taking action on climate change and climate protection. This finding is particularly noteworthy considering the prominent role of the young climate movement in recent years which offered substantial prospects for the widespread (re)politicization of youth, especially in matters of climate change.

The next chapter offers some possible explanations for the prevalence of the individualizing logic. The theoretical framework of social interpretation patterns emphasizes that climate-related attitudes and behaviors are not generated individually, but are socially mediated and embedded. Based on this assumption we raise the question of the historical-cultural processes of meaning construction—the discourses—within which climate-related patterns of interpretation and action orientations of young people emerge (Keller, 2007). Expanding upon a large body of research that typically points to a combination of “intrapersonal” factors, such as beliefs, attitudes, or personal norms in explaining pro-environmental behavior at the individual level (e.g., Busch et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Yang and Wilson, 2023), we explore the discursive origins of the individualizing interpretation pattern and action orientation on a societal level. Furthermore, we will discuss the transformative potential that individualizing and politicizing orientations bring to climate action. What are the risks associated with the individualizing focus on sustainable consumption and lifestyle matters, and what mobilizing force does the politicizing pattern unleash?

4.1 The discursive origins of the individualizing interpretation pattern

Given the theoretical assumption that social discourses function as “production sites” (Keller, 2007, p. 221) for interpretation patterns, it becomes pertinent to investigate the specific discourses to which the climate protection-related interpretation patterns correspond. How is the prevailing individualizing interpretation pattern related to political, media, and environmental education narratives, and corresponding dynamics of responsibilization (Grunwald, 2018)? Addressing this question involves exploring social science research, which has been examining climate change discourses, narratives, and framings for decades.

By analyzing media chronicles, political agendas, education programs, corporate public relations efforts, advertising campaigns, and the subjects of academic research, numerous studies have revealed a strong emphasis on the roles and duties of consumers in addressing climate change. For instance, Fleming et al. (2014, p. 413) identify a “culture of consumption discourse,” while Mock (2020, p. 245) recognizes a “narrative of consumer responsibility.” Following a “paradigm of ABC–attitude, behavior, and choice” (Shove, 2010, p. 1,273), these narratives all emphasize high environmental awareness and conscious consumption choices as primary solutions to the climate crisis, as do most interviewees in our interviews when expressing individualizing patterns. The accompanying moral appeal targets individuals, urging them to contribute to climate protection through behavior change. In this context, some authors refer to the notion of “responsibilization” as the process through which responsibility is produced and specifically attributed to certain agents (Soneryd and Uggla, 2015; Buschmann and Sulmowski, 2018; Grunwald, 2018). A prominent example of responsibilization of consumers in climate protection is a campaign by the oil company BP, where the calculation of individual ecological footprints was popularized to divert attention from its own “dirty” business model (Lamb et al., 2020).

However, the promotion of consumer agency and responsibility is not solely driven by climate-damaging industries. The individualizing narrative permeates several arenas of climate change-related discourse, including sustainable lifestyle literature and social media channels (Joosse and Brydges, 2018; Lartigue et al., 2021) as well as educational institutions and the international program “Education for Sustainable Development” (ESD; Kehren, 2017; Kranz et al., 2022). Also, certain research communities have faced criticism for their strong focus on the study of individual “pro-environmental behaviors” (Schmitt et al., 2020). Across all these discursive spheres, the same individualizing logic emerges, which is also evident in the interpretation patterns observed among the interviewed young individuals.

Finally, it is also noteworthy that even certain segments within the climate movement—such as the so-called “lifestyle movements” (Büchs et al., 2015)—reproduce the individualizing logic through their emphasis on consumer criticism and individual action (Wahlström et al., 2013; Thörn and Svenberg, 2016). For instance, Thörn and Svenberg (2016, p. 605) find that parts of the Swedish environmental movement “actively participated in neoliberal responsibilization by emphasizing the moral responsibility of the consumer.” Likewise, the framing of the FFF movement underscores the young generation's responsibility to exert pressure on politics, but also the need to adapt lifestyle and consumption behavior to environmental imperatives (Sommer et al., 2019, p. 42; de Moor et al., 2021b, p. 622; Svensson and Wahlström, 2023, p. 11). Overall, the prevalence of the individualizing interpretation pattern in the interviews, along with the clear inclination toward private sphere behavior highlighted in the representative survey, can be seen as a manifestation of the hegemonic discourse of individualization and its associated processes of consumer responsibilization.

4.2 Transformative potentials and limits of the individualizing and politicizing orientations

As multiple crises, including climate change, continue to escalate, scholars and policymakers increasingly stress the necessity for a systemic societal transformation (e.g., Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Globale Umweltveränderungen, 2011; Brand, 2016; Dörre et al., 2019). Therefore, in this chapter, we discuss the transformative potentials and limitations of both the individualizing and politicizing rationales. To what extent can these interpretation patterns and action orientations foster or impede transformative processes?

The study revealed both a higher frequency and more positive evaluation of individual consumption actions compared to civic engagement, as well as a dominant individualizing interpretation pattern, which assigns responsibility to the individual and promotes sustainable consumption. This tendency may come with several societal risks, three of which are explained here.

First, confidence in the efficacy of individual climate protection measures is founded on assumptions about the direct link between knowledge and action, disregarding systemic barriers that impede climate-protective behavior. It is well-established that a heightened problem awareness is insufficient for practical climate protection (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). Extensive research on psychological barriers (Gifford, 2011), behavioral lock-ins (Seto et al., 2016), the stabilizing influence of routines and material infrastructures (Warde, 2005), and the power of social norms and ideologies (Stuart et al., 2020) has revealed that for individual behaviors to change, several conditions must be met, which lie beyond personal goodwill.

Second, even when consumption decisions are made based on sustainability criteria, they may not necessarily yield the desired positive effects, but often remain primarily symbolic (Whitmarsh et al., 2021). The effectiveness of individual endeavors toward sustainable consumption is frequently overestimated (Mock, 2020; Grunwald, 2022). This is evident, for instance, in the fact that statistically, the intention to engage in environmentally friendly behavior has a significantly smaller impact on the ecological footprint compared to factors like income level (Huddart Kennedy et al., 2015; Moser and Kleinhückelkotten, 2018). Consequently, the latest IPCC report emphasizes, “Individual behavioral change is insufficient for climate change mitigation unless embedded in structural and cultural change” (IPCC, 2022, p. 506). In sum, as argued earlier, systemic change is necessary for broad behavioral change (e.g., Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Globale Umweltveränderungen, 2011).

Third, although some authors advocate for conscious consumption as a form of “lifestyle politics” (de Moor, 2017; Zamponi et al., 2022), others stress that the primary focus on individual lifestyle issues may divert attention from individuals' roles as political citizens, workers or activists, eventually resulting in demobilization in these roles (Huddart Kennedy et al., 2015; Maniates, 2019). Petersen et al. (2019) even diagnose a new form of “ideological denialism” (p. 119), arguing that the concentration on private-sphere measures “contribute to a denial of the sociostructural changes necessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” (p. 129). Ultimately, the individualizing action orientation may lead to a perception that small, everyday changes in behavior alone can resolve the climate crisis, inadvertently reinforcing the unsustainable status quo and inhibiting transformation (Grunwald, 2010). Overall, the dominance of the individualizing pattern poses the risk of fostering widespread depoliticization. By portraying climate change and mitigation as a matter of individual awareness, choice, and behavior, it obscures the structural causes of climate changes, powerful interests that seek to maintain these structures, as well as the potential for political contestation and collective agency.

In contrast, the politicizing pattern moves the issue of climate change into the realm of power struggles, political influence and collective action. Within this pattern, established structures of production and consumption as well as status quo approaches to climate mitigation are challenged, suggesting the need for systemic societal change and the responsibility of political and economic actors. While individual aspirations of sustainable consumption are deemed insufficient both morally and practically, collective climate action and political contestation emerge as desirable and effective pathways for change.

With this programmatic shift, the politicizing pattern carries a strong impetus for collective mobilization in climate action. Transformation research underscores the relevance of such grassroots movements and civil society initiatives in facilitating transformative change and effective climate action. First, there is the potential to directly or indirectly reduce greenhouse gas emissions through climate activism: “Collective action and social organizing are crucial to shift the possibility space of public policy on climate change mitigation” (IPCC, 2022, p. 506; also see Fisher and Nasrin, 2021; Thiri et al., 2022). Second, the climate justice movement holds the potential to challenge prevailing power dynamics, strengthen democratic deliberation, and cultivate alternative modes of more equitable governance (Temper et al., 2018). This is also true for youth-led movements (Sloam et al., 2022). Especially for young people, whose influence on climate governance is often constrained, be it as voters, employees, investors, or consumers, informal types of political involvement represent an important means of empowerment (Wallis and Loy, 2021; Sloam et al., 2022). Overall, the politicizing pattern of interpretation and action, with its impetus toward political contestation and collective agency, unleashes considerable transformational potential.

5 Conclusion

The empirical analyses in this paper have shown that the interpretation patterns and action orientations of young people in Germany are primarily shaped by an individualizing logic. According to this logic, climate protection is framed as a lifestyle-related field of action, responsibility for environmental climate protection is mainly located with private individuals, and the necessity and effectiveness of conscious consumption is emphasized. Conversely, a politicizing logic is also discernible within these interpretation patterns and action orientations. This alternative logic portrays climate protection through the lens of political action and profound social change, attributing substantial weight to collective mobilization within civil society.

According to the current state of knowledge, it seems reasonable to promote the wider dissemination of politicizing action orientations for effective climate protection and the requisite socio-ecological transformation. On one aspect, this is indicated by the challenges associated with the individualizing pattern, encompassing the constrained efficacy of individual consumption adjustments and the pitfalls of moralization and polarization. Furthermore, a major risk lies in the fact that the narrow focus on individual responsibilities obscures the need for structural change, political agency, and democratic processes in climate action, thereby exerting a depoliticizing effect. The politicizing pattern, with its potential to incite civic involvement and thereby amplify public pressure on decision-makers, promises not only an important contribution to the implementation of climate policies. It also holds the potential to enhance democratic deliberation and facilitate learning processes, along with the prospect of linking climate protection with broader social concerns, thereby offering a prospect of improving the conditions for a thorough and just transformation.

The continued presence of FFF and other climate groups and initiatives represent one chance to expand “the discursive opportunity structure to politicize environmentalism” (de Moor et al., 2021a, p. 325). However, the (re)politicization of interpretation patterns and action orientations for more ambitious and socially equitable climate action is not limited to the climate movement and civil society organizations alone. Various stakeholders spanning the realms of science, politics, education, and media—especially those endowed with increased discursive power—can leverage their position to re-evaluate their prior focus on individual responsibility and consumption-related matters, and instead promote collective engagement. For instance, educational agents such as schools, training institutions, or universities can implement transformative learning approaches that fortify young individuals' political education and participatory capabilities, aligning with a critical-emancipatory education for sustainable development (Kranz et al., 2022; Singer-Brodowski, 2023). The objective here is not to persuade young individuals to adopt specific sustainable behaviors, but rather to aid them in questioning and altering societal and personal patterns of thought and action. The learning objective thus pivots toward fostering (self-)reflective aptitude, along with empowerment for political participation. In further support of this endeavor, environmental and educational policies can amplify the role of learning within the context of socio-ecological transformation processes and advocate for participatory and action-driven pedagogical approaches (Blum et al., 2021).

The limitations of the current study suggest several avenues for future research. For example, it must be assumed that the reconstruction of interpretation patterns presented here is incomplete. Since it cannot be guaranteed that the “carriers” of all possible interpretation rules were interviewed, only a partial reconstruction of the interpretation patterns and their dimensions can be claimed. This is especially true for the politicizing interpretation pattern, which was reconstructed on the basis of rather sparse data from only a few interviews. Thus, one approach for future research would be to rely on a more diverse interview sample that includes a broader range of young people engaged in climate action. Such an expanded sample would allow for a closer look at the nuances and variations within the politicizing interpretation pattern, for example with regard to different levels of trust in institutions and its role in guiding climate (in)action. This could also help to shed light on the extent to which different forms of politicization may imply distinct types of engagement that are either aligned with, beyond, or against established institutions.

More generally, future research should further investigate ongoing changes in climate-related interpretations and action orientations. It is plausible, for instance, that the discursive influences exerted by the climate movement may not have been as strongly evident during the time of this study, potentially leading to a limited manifestation of politicization effects within the interpretation patterns. Given the sustained prominence of climate change issues and the emergence of new experiences in this context, coupled with potential shifts in climate movement's framings and the public discourse, the interpretation patterns shared by young individuals will most likely continue to evolve. Finally, it may be worthwhile to explore the varying transformational ideals and future visions embraced by young individuals through interpretation pattern analysis, particularly for social science research focused on sustainability transformations. Such an undertaking would facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the collectively held normative concepts regarding the trajectory of a socio-ecological transition and the variations within politicizing interpretation patterns, a subject likely to bear significance not solely within the realms of scholarly investigation but also within the socio-political arena.

Data availability statement

Requests to access these datasets should be directed to VF, dml2aWFuLmZyaWNrQGlvZXcuZGU=.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human samples in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

LR: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. VF: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article relies on empirical material from the study “Zukunft? Jugend fragen! 2021”, which was funded by the German Environmental Agency (FKZ 3719 16 105 2). We further acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the Freie Universität Berlin.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This concept originates from the German-speaking context and specifically from the notion of “soziale Deutungsmuster.” It could also be translated into English as collective representations (Ullrich, 2022, p. 2–4), which highlights the conceptual proximity to social representation theory rooted in social psychology (Moscovici, 1988). In this study, we will solely use the term “interpretation patterns” or “patterns of interpretation.”

2. ^There is no theoretical agreement on the precise inner structure of interpretation patterns. Nonetheless, there is a consensus regarding the multifaceted nature of interpretation patterns. This implies that these patterns always comprise several knowledge components, such as problem definitions, causal attributions, assessments of relevance, valuations, standardized solutions, and efficacy expectations. However, the specific configuration of dimensions encompassed by a given interpretation pattern cannot be definitively determined through theoretical means, but always have to be validated empirically.

3. ^It is worth noting that the concepts of individualization and politicization were not used as preliminary categories during the coding phase. The original analysis of interpretation patterns, as carried out in the cited master's thesis (Reuter, 2021), was exploratory in nature and was not guided by the pre-assumption of identifying an individualizing or politicizing pattern.

References

Akenji, L. (2014). Consumer scapegoatism and limits to green consumerism. J. Clean. Prod. 63, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.022

Albert, M., Quenzel, G., and Hurrelmann, K. (2019). Jugend 2019. Eine Generation meldet sich zu Wort. Shell Jugendstudie. Beltz. 18:6. doi: 10.3224/diskurs.v14i4.06

Amel, E., Manning, C., Scott, B., and Koger, S. (2017). Beyond the roots of human inaction: fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 356, 275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1931

Bartels, A., Brahimi, E., Karic, S., Rück, F., and Schröer, W. (2022). Listening to Young People: Mobility for future. Zentrale Ergebnisse der Studie: Learning Mobility in Times of Climate Change (LEMOCC). Bonn. Available online at: https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/media/fb1/sozialpaedagogik/Publikationen/Open_Access/IJAB_Report_LEMOCC_D_1_.pdf (accessed October 12, 2023).

Bartels, A., and Karic, S. (2023). A gap between talk and action? Engagement junger Menschen im Kontext des Klimawandels. Voluntaris 11, 11–24. doi: 10.5771/2196-3886-2023-1-11

Blum, J., Fritz, M., Taigel, J., Singer-Brodowski, M., Schmitt, M., and Wanner, M. (2021). Transformatives Lernen durch Engagement: ein Handbuch für Kooperationsprojekte zwischen Schulen und außerschulischen Akteur*innen im Kontext von Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Available online at: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/transformatives-lernen-durch-engagement (accessed October 12, 2023).

Bögelein, N., and Vetter, N., (eds). (2019). “Deutungsmuster als Forschungsinstrument - Grundlegende Perspektiven,” in Der Deutungsmusteransatz: Einführung - Erkenntnisse - Perspektiven (Weinheim: Beltz Juventa), 12–38.

Brand, U. (2016). “Transformation” as a new critical orthodoxy: the strategic use of the term “Transformation” does not prevent multiple crises. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 25, 23–27. doi: 10.14512/gaia.25.1.7

Brügger, A., Gubler, M., Steentjes, K., and Capstick, S. B. (2020). Social identity and risk perception explain participation in the Swiss Youth Climate strikes. Sustainability 12:10605. doi: 10.3390/su122410605

Büchs, M., Saunders, C., Wallbridge, R., Smith, G., and Bardsley, N. (2015). Identifying and explaining framing strategies of low carbon lifestyle movement organisations. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.009

Bundesministerium für Umwelt Naturschutz, nukleare Sicherheit und Verbraucherschutz and Umweltbundesamt. (2022). Umwelt, Klima, Wandel - was junge Menschen erwarten und wie sie sich engagieren, Broschüre Nr. 20008. Available online at: https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/zukunft_jugend_fragen_2021_bf.pdf (accessed October 12, 2023).

Busch, K. C., Ardoin, N., Gruehn, D., and Stevenson, K. (2019). Exploring a theoretical model of climate change action for youth. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 41, 2389–2409. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1680903

Buschmann, N., and Sulmowski, J. (2018). “Von ≫Verantwortung≪ zu ≫doing Verantwortung≪,” in Reflexive Responsibilisierung: Verantwortung für nachhaltige Entwicklung, eds. A. Henkel, N. Lüdtke, N. Buschmann, L. Hochmann (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag), 281–296.

Calmbach, M., Flaig, B., Edwards, J., Möller-Slawinski, H., Borchard, I., and Schleer, C. (2020). Wie ticken Jugendliche? Lebenswelten von Jugendlichen im Alter von 14 bis 17 Jahren in Deutschland. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Schriftenreihe Band 10531. Available online at: https://www.bpb.de/system/files/dokument_pdf/SINUS-Jugendstudie_ba.pdf (accessed October 12, 2023).

de Moor, J. (2017). Lifestyle politics and the concept of political participation. Acta Polit. 52, 179–197. doi: 10.1057/ap.2015.27

de Moor, J., Catney, P., and Doherty, B. (2021a). What hampers “political” action in environmental alternative action organizations? Exploring the scope for strategic agency under post-political conditions. Soc. Mov. Stud. 20, 312–328. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2019.1708311

de Moor, J., de Vydt, M., Uba, K., and Wahlström, M. (2021b). New kids on the block: taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 20, 619–625. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2020.1836617

Della Porta, D., and Parks, L. (2014). “Framing processes in the climate movement: from climate change to climate justice,” in Routledge Handbook of the Climate Change Movement, eds M. Dietz and H. Garrelts (London: Routledge), 19–30.

Diekmann, A., and Preisendörfer, P. (2003). Green and greenback: the behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Rational. Soc. 15, 441–472. doi: 10.1177/1043463103154002

Dörre, K., Rosa, H., Becker, K., Bose, S., and Seyd, B. (2019). Große Transformation? Zur Zukunft moderner Gesellschaften. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Federal Ministry for the Environment Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety. (2018). National Programme on Sustainable Consumption. From Sustainable Lifestyles Towards Social Change. Available online at: https://www.bmuv.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltiger_konsum_broschuere_en_bf.pdf (accessed February 25, 2024).

Feldman, H. (2022). Who's striking, and who's not? Avoiding and acknowledging bias in youth climate activism research. Austr. J. Environ. Educ. 38, 112–118. doi: 10.1017/aee.2022.2

Fisher, D. R., and Nasrin, S. (2021). Climate activism and its effects. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. 12:e683. doi: 10.1002/wcc.683

Fleming, A., Vanclay, F., Hiller, C., and Wilson, S. (2014). Challenging conflicting discourses of climate change. Clim. Change 127, 407–418. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1268-z

Frick, V., Holzhauer, B., and Gossen, M. (2023). Abschlussbericht “Zukunft? Jugend fragen! 2021”. Dessau-Roßlau: UBA-Texte.

Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., and Reese, G. (2018). A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 125, 245–269. doi: 10.1037/rev0000090

Gifford, R. (2011). The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 66:290. doi: 10.1037/a0023566

Grunwald, A. (2010). Wider die Privatisierung der Nachhaltigkeit - Warum ökologisch korrekter Konsum die Umwelt nicht retten kann. Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 19, 178–182. doi: 10.14512/gaia.19.3.6

Grunwald, A. (2018). “Warum Konsumentenverantwortung allein die Umwelt nicht rettet. Ein Beispiel fehllaufender Responsibilisierung,” in Reflexive Responsibilisierung: Verantwortung für nachhaltige Entwicklung, eds. A. Henkel, N. Lüdtke, N. Buschmann, and L. Hochmann (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag), 421–436.

Grunwald, A. (2022). “Verantwortliches Klimahandeln: Konsumentenverantwortung ist nötig, reicht aber nicht,” in Demokratie und Nachhaltigkeit. Aktuelle Perspektiven auf ein komplexes Spannungsverhältnis, eds. T. Gumbert, C. Bohn, D. Fuchs, B. Lennartz, and C. J. Müller (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft), 73–92.

Haugestad, C. A., Skauge, A. D., Kunst, J. R., and Power, S. A. (2021). Why do youth participate in climate activism? A mixed-methods investigation of the #FridaysForFuture climate protests. J. Environ. Psychol. 76:101647. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101647

Hayward, B., Dobson, A., Jackson, T., and Hart, R. (2012). Children, Citizenship and Environment: Nurturing a Democratic Imagination in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

Huddart Kennedy, E., Krahn, H., and Krogman, N. T. (2015). Are we counting what counts? A closer look at environmental concern, pro-environmental behaviour, and carbon footprint. Local Environ. 20, 220–236. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.837039

Hurrelmann, K., and Albrecht, E. (2020). Generation Greta. Was sie denkt, wie sie fühlt und warum das Klima erst der Anfang ist. Weinheim: Beltz.

IPCC (2018). “Summary for policymakers,” in Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, eds V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 324. doi: 10.1017/9781009157940.001

IPCC (2022) “Climate change 2022: mitigation of climate change,” in Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change eds P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, and J. Malley (Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.007.

Joosse, S., and Brydges, T. (2018). Blogging for sustainability: the intermediary role of personal green blogs in promoting sustainability. Environ. Commun. 12, 686–700. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1474783

Kassner, K. (2003). “Soziale Deutungsmuster - über aktuelle Ansätze zur Erforschung kollektiver Sinnzusammenhänge,” in Sinnformeln: Linguistische und soziologische Analysen von Leitbildern, Metaphern und anderen kollektiven Orientierungsmustern, eds. S. Geideck, W.-A. Liebert (Berlin: De Gruyter), 37–58.

Kehren, Y. (2017). Bildung und Nachhaltigkeit. Zur Aktualität des Widerspruchs von Bildung und Herrschaft am Beispiel der Forderung der Vereinten Nationen nach einer 'nachhaltigen Entwicklung'. Pädagogische Korrespondenz 55, 59–71. doi: 10.25656/01:20568

Kelle, U., and Kluge, S. (2010). Vom Einzelfall zum Typus: Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung (2. Ed.). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2010:6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-92366-6

Keller, R. (2007). “Methoden sozialwissenschaftlicher Diskursforschung,” in Handbuch Wissenssoziologie und Wissensforschung, eds. R. Schützeichel (Konstanz: UVK), 214–224.

Kenis, A. (2021). Clashing tactics, clashing generations: the politics of the school strikes for climate in Belgium. Polit. Govern. 9, 135–145. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i2.3869

Kenis, A., and Lievens, M. (2014). Searching for 'the political' in environmental politics. Environ. Polit. 23, 531–548. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.870067

Knappe, H., and Renn, O. (2022). Politicization of intergenerational justice: how youth actors translate sustainable futures. Eur. J. Fut. Res. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40309-022-00194-7

Kollmuss, A., and Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 239–260. doi: 10.1080/13504620220145401

Kranz, J., Schwichow, M., Breitenmoser, P., and Niebert, K. (2022). The (un)political perspective on climate change in education—a systematic review. Sustainability 14, 4194. doi: 10.3390/su14074194

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Mixed Methods: Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Lamb, W. F., Mattioli, G., Levi, S., Roberts, J. T., Capstick, S., Creutzig, F., et al. (2020). Discourses of climate delay. Glob. Sustainabil. 3:13. doi: 10.1017/sus.2020.13

Lartigue, C., Carbou, G., and Lefebvre, M. (2021). Individual solutions to collective problems: the paradoxical treatment of environmental issues on Mexican and French YouTubers' videos. J. Sci. Commun. 20:A07. doi: 10.22323/2.20070207

Lee, K., O'Neill, S., Blackwood, L., and Barnett, J. (2022). Perspectives of UK adolescents on the youth climate strikes. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 528–531. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01361-1

Li, D., Zhao, L., Ma, S., Shao, S., and Zhang, L. (2019). What influences an individual's pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 146, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.024

Maki, A., Carrico, A. R., Raimi, K. T., Truelove, H. B., Araujo, B., and Yeung, K. L. (2019). Meta-analysis of pro-environmental behaviour spillover. Nat. Sustainabil. 2, 307–315. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0263-9

Maniates, M. F. (2001). Individualization: plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world? Glob. Environ. Polit. 1, 31–52. doi: 10.1162/152638001316881395

Maniates, M. F. (2019). “Beyond magical thinking,” in Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Governance, eds. A. Kalfagianni, D. Fuchs, and A. Hayden (London: Routledge), 267–281.

Marquardt, J., and Lederer, M. (2022). Politicizing climate change in times of populism: an introduction. Environ. Polit. 31, 735–754. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2022.2083478