95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 30 June 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.687695

This article is part of the Research Topic Economic Integration and Political Change in Democracies View all 7 articles

Polarization is not new in Europe. Looking at electoral support for radical political forces after the Second World War, one can observe how polarization has been on the rise since the 1960s. Still, it is in the 1990s, with the thaw of European party systems and the subsequent emergence of (populist) radical parties, that the percentage of votes for anti-political establishment parties reached unprecedented levels. In this article, we not only show the general (country-level) picture but also highlight both the consequences and causes of polarization, proposing at the same time some potential remedies to combat it. Using an aggregate, longitudinal unique dataset, containing 47 European countries across more than 170 years from 1848 to 2020 (Casal Bértoa, 2021; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, 2021), we try to shed light here on the perils of polarization for the quality of democracy, how traditional political parties are to be blamed, and how we can tackle the problem.

A specter is haunting Europe, the specter of polarization. In the last decade, the percentage of votes for anti-political-establishment parties (APEp) (Abedi, 2002; 2004), be they populist (Rooduijn et al., 2020), anti-system (Zulianello, 2019), protest (Morlino and Raniolo, 2017), radical (Funke et al., 2016), and/or extreme (Carter, 2005), has exponentially increased. And with it, the distance between political parties and the irreconcilable differences (either ideological, personalistic, or both) among voters has also increased (Reiljan, 2020).

Although stricto sensu, polarization refers to the ideological or programmatic distance among the parties in the political spectrum (Sani and Sartori, 1983), to the extent that the higher the ideological or programmatic discrepancies, the higher the polarization, the truth is that “party system polarization is a difficult concept to measure” (Dalton, 2008: 903). In fact, assuming that we would need to know the ideological position of parties and, when possible, also their vote shares, achieving this information for a large number of countries and, especially, for periods far in time results extremely complicated. For this reason, researchers tend to estimate polarization using other (indirect) indicators, such as the number of parties in a system, the size of extremist parties, or the vote share for governing parties (Powell, 1982; Pennings, 1998).

In the current article, influenced by Sartori’s (1976) and Dodd’s (1976) theorizing about the negative impact of anti-systemic parties, we look at electoral polarization, measured as the percentage of votes obtained by APEp (Karvonen and Quenter, 2003: 142; Powell 1982; Casal Bértoa and Weber, 2019).1 In this regard, we understand APEp as those fulfilling “all of the following criteria: 1) it perceives itself as a challenger to the parties that make up the political establishment; 2) it asserts that a fundamental divide exists between the political establishment and the people (implying that all establishment parties, be they in government or in opposition, are essentially the same); and 3) it challenges the status quo in terms of major policy issues and political system issues” (Abedi, 2004: 12).

This is not in vain due to the cartelization of traditional political parties (Katz and Mair, 1995) and their subsequent convergence towards the center of the political spectrum, which makes it very difficult for voters to (ideologically) distinguish among the various political options; the triumph of APEp (characterized by fringe messages) was clear. Thus, the space open at the margins of the ideological spectrum led APEp to emerge and/or be reborn as attractive political options for a part of the electorate: in general, those angriest with the traditional parties. This idea was already summarized in the 90s by Kitschelt and McGann:

Where moderate left and right parties have converged toward centrist positions and may even have cooperated in government coalitions, the chances for “populist antistatist parties” as well as parties of the “New Radical Right” (or Left) to be electorally successful rise considerably” (Kitschelt and McGaan, 1995: 17, 20–23, 48).

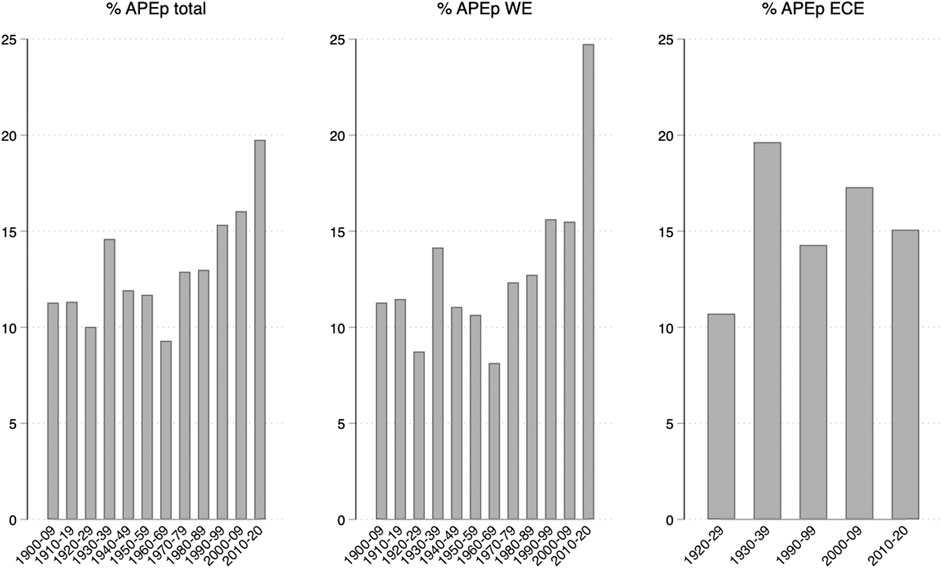

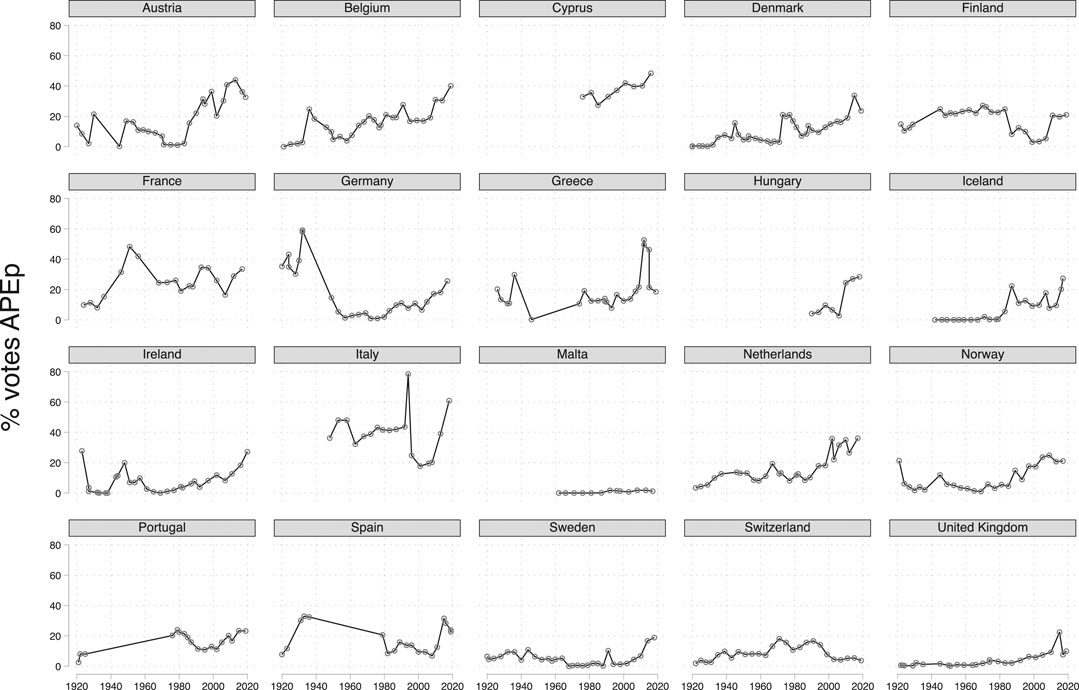

A simple look at Figure 1, which displays the average (see Total graph) level of electoral polarization in Europe since 1900, disentangling between Western European (WE) and East-Central European (ECE) countries, clearly shows that, on average, party politics in the continent have never been so polarized (especially in the West). With very few exceptions (e.g., Malta, Switzerland) polarization is on the rise in every single Western European country (see Figure 2, as well), especially in those affected by immigration (e.g., Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands) and/or the economic crisis (e.g., Spain, Italy, Greece, and Cyprus).

FIGURE 1. Polarization in 47 European democracies (1900–2020). Source:Casal Bértoa (2021). Notes: The “total” graph display the average levels of 47 European countries; the “WE” graph displays the aggregate levels by decade for the countries included in Figure 2 and the “ECE” graph displays the aggregate levels by the decade of the countries included in Figure 3. We start in 1900 rather than 1848 due to the very low number of cases (i.e., France, Greece, and Switzerland) before the beginning of the 20th century.

FIGURE 2. Polarization in Western Europe (1920–2020). Source:Casal Bértoa (2021).

On average, during the last decade, the level of polarization has increased by more than five points. If we are to compare with other less polarized periods (e.g., 1960s), we can say that in the last 7 years, polarization has almost tripled to the point that in most countries, the election with the highest level of polarization since the Second World War has taken place in the last 10 years.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of votes for APEp in 20 Western European democracies since the beginning of the 20th century. The pattern is clear, and, in agreement with the most recent literature, electoral support for this set of parties is on the rise (Wolinetz and Zaslove, 2018; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). On average, the percentage of votes for APEp in Western Europe during the last few years has exponentially increased: from around 17% during the previous two decades (1990–2009) to more than 24% in the 2010s (2010–2020). However, it is also important to note that in an important selection of countries (i.e., Germany, Finland, France, and Ireland), the election with the highest percentage of votes for APEp took place before the beginning of the 21st century.

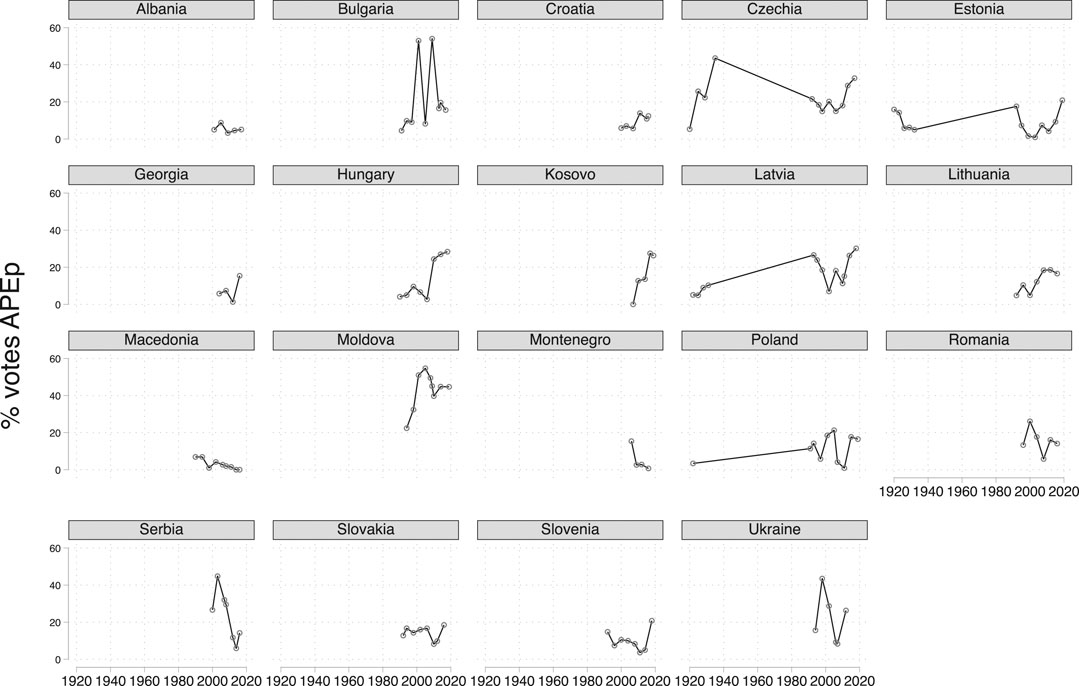

In this post-communist world, Europe has not been an exception. Figure 3 shows the level of polarization in 19 post-communist democracies since the end of the Cold War and, for those that had a previous democratic experience (e.g., Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, and Poland), also the inter-war period. As in Western Europe, polarization has been on the rise in most nations. The Visegrad four (i.e., Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, and, especially, Hungary) are clear examples.

FIGURE 3. Polarization in post-communist Europe (1920–2020). Source:Casal Bértoa (2021).

Among Post-Soviet States, electoral polarization in both Estonia (20.9) and Latvia (30.2%) has never been higher. In Ukraine, APEp attracted more than a quarter of the electorate just before democracy collapsed. In Armenia and Moldova, electoral support for APEp decreased during the last elections but still records two-digit figures. In Georgia the percentage vote for APEp reached a record level during the 2016 parliamentary elections, leading to a spiral of instability and political turmoil unparalleled since the democratization of the country in 2004. And a similar story can be found in the Balkans, not only in more consolidated democracies like Croatia and Slovenia, both EU members, but also in North Macedonia or the youngest European nation: Kosovo.

For all these reasons, and given the relevancy politicians and academics, but also journalists and practitioners, have given to the issue of rising polarization, it is time that we take stock of all that is known about both the consequences (for democracy) and the causes of polarization before we try to understand what the possible solutions to the polarization problem are.

The number of works pointing out the negative consequences of polarization for the healthy functioning of democracy is vast. No matter which type of polarization one looks at—ideological, political, populist (Sani and Sartori, 1983; Enyedi, 2016)—there is an agreement among experts that in very polarized societies democracy will suffer (Lane and Ersson, 2007; Bornschier, 2019). However, the ways in which polarization will damage democracy might differ.

For example, in a recent work Zagórski et. al. (2021), using an original dataset for 20 Western European countries from the late 19th century until the end of 2019, show that the percentage of support for APEp is negatively correlated with the level of electoral turnout, traditionally used as an indicator of the healthy functioning of democracy in a country. The idea is that polarization, a fruit of the damaged party–voter relationship, discourages citizens from political participation, putting into question the legitimacy of the system as a whole. What Zagórski et al. (2021) also found, however, is that against previous scholarship (see Wilford, 2017), those negative effects level-off in contexts of both high APEp’s vote share and high fragmentation.

Moving to the direct impact of APEp’s on the level of democracy, a more traditional school of thought, inspired by Sartori’s seminal work, equated the presence of electorally successful anti-systemic parties (e.g., fascist and communist) in the political system, and the consequent polarization among parties and electorates, with “conflict, protest and paralysis” (Singer, 2016). The Weimar Republic in Germany or the Spanish Second Republic were good examples of how high ideological distances between extreme parties could lead to inimical oppositions, polarization, irresponsible oppositions, centrifugal competition,2 and the politics of outbidding, causing high levels of systemic instability and, eventually, democratic collapse (Sartori, 1976; Linz, 1978; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, 2021).

Given the linkage between support for populist parties, a type of APEp, and polarization (Bischof and Wagner, 2019), we can say that the relationship between populism and democracy has been seen as threefold. For some populism has a clear negative effect on the functioning of democracy. To give but one example, Rosanvallon posits that populism is a “perverse inversion of the ideals and procedures of representative democracy” (Rosanvallon, 2008: 265). In this line, Panizza considers the following:

Populism has traditionally been regarded as a threat to democracy because of the vertical relation between the populist leader and his/her followers; the alleged appeal to the raw passions (…) and the disregard for political institutions and the rule of law (Panizza, 2005: 29).

For others, such as Laclau (2005) in some stances, populism is good in the sense that, by permitting the aggregation of demands from those who belong to politically excluded sectors, it helps to improve the nature of democracy. Finally, in what is the position of the majority of scholars who adhere to the so-called minimalist or ideational definition of populism,3 the question relating to the extent to which populism is good or bad for democracy needs to be addressed empirically and country-specifically. In other words, populism’s effect on democracy is not pre-determined and can exhibit both progressive and regressive effects on the state of democracy. As underlined by Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, “depending on its electoral power and the contexts in which it arises, populism can work as either a threat or a corrective for democracy” (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017: 79, italics in the original).

Other scholars, based on the Latin American experience and following the steps of those who defend the need for political moderation as one of the keys for the survival of a democracy pointed out the negative impact polarization might have on government stability and executive-legislative relations. The idea is that the more polarized party politics in a country become, the more difficult will be to build stable legislative coalitions and, therefore, carry out the necessary public policies (Binder, 2008). This is also because, in polarized polities, political elites “have greater incentives to overtly politicize the bureaucracy or engage in clientelistic practices which will affect, for example, civil service recruitment and accordingly state continuity and efficiency” (Xezonakis, 2012: 15).

More recently, and given the rise in support for populist leaders, especially in Europe (e.g., Hungary—where they govern—but also Austria, Italy, Poland, and Spain where they play a relevant role as coalition partners or The Netherlands, Finland, and Greece where APEp are the main opposition parties) and Latin America (e.g., Venezuela, Bolivia), but also in Asia (e.g., Philippines, India) or the United States, scholars have warned about the perils of populist polarization for constitutional liberal democracy (Müller, 2016; Galston, 2018)–especially if we take into consideration the close ideological links between these types of parties and authoritarianism (e.g., Fascism, Communism) or illiberal democracy (Eatwell, 2017). This is so because in populist polarized societies, mainstream parties will be more inclined to accommodate populists’ discourse and/or policies (e.g., anti-immigration, Euroscepticism, etc.) or, even more dangerous, adopt institutional reforms directed to restrict political competition (e.g., banning public funding of parties), liberalism (e.g., censorship), or constitutionalism (e.g., suppression of judicial independence).

While, with few exceptions (e.g., Venezuela, Hungary, and the United States), democracy has not collapsed in highly polarized democracies, it has definitively affected the quality of democracy. Not in vain, and as Bischof and Wagner (2019) have rightly pointed out, the entrance of radical parties in the political competition affects the electorate at both sides of the political spectrum, pulling them towards the extremes. The main consequence being, as they also show, an exponential increase in the levels of polarization, with the negative impact this has on both the party system and democratic stability (Sartori, 1976; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, 2021).

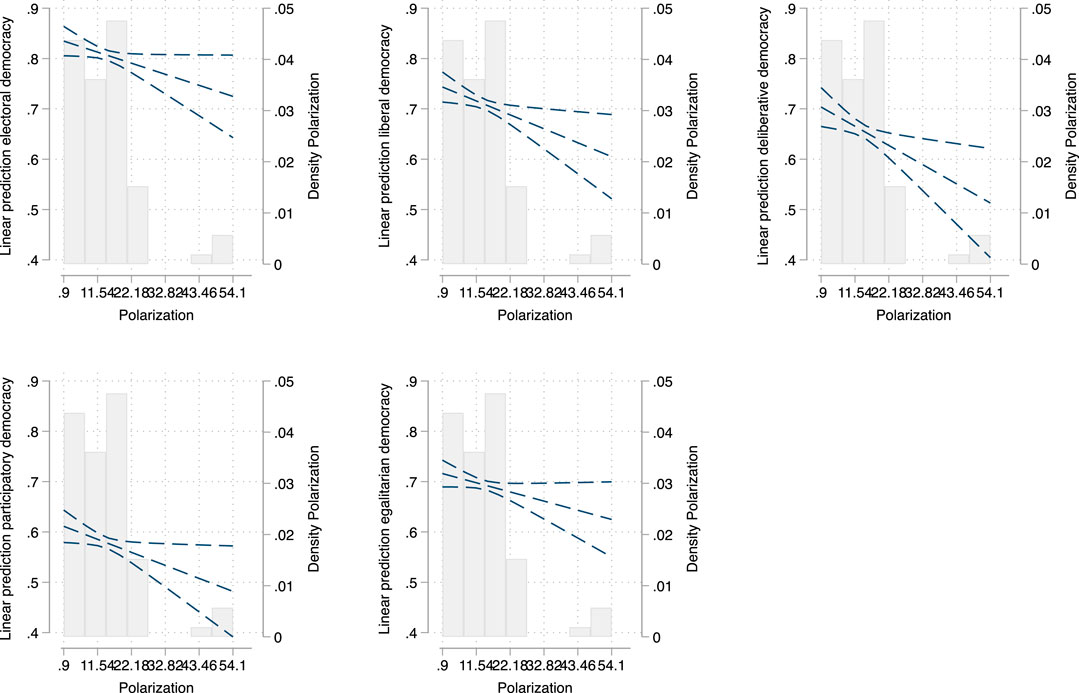

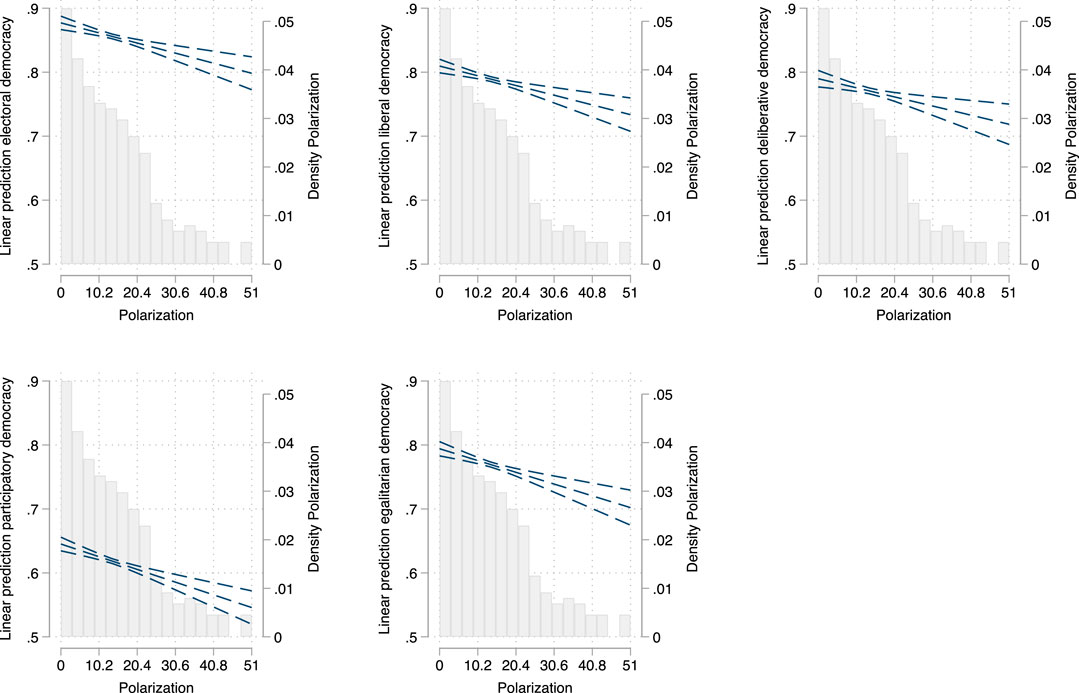

This is precisely what we have shown in a recent analysis (Rama and Casal Bértoa, 2020) of the effects of (electoral) polarization on different dimensions (i.e., electoral, liberal, deliberative, participatory, and egalitarian) of democracy in 28 European democracies since 1950 until 2017 (Coppedge et al., 2018).4 Trying to assess to what extent the percentage of votes for APEp and the levels of democracy in a given country are (or not) negatively correlated, we have conducted Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with country and year dummies, including some control variables to avoid spurious correlations (e.g., Gross Democratic Product, Gross Democratic Product growth, Effective Number of Electoral Parties, electoral disproportionality, type of regime, total electoral volatility, and years of democracy).5 Following this strategy, and trying to go a step further, we replicate the same analysis conducted in Rama and Casal Bértoa, (2020) but dividing the sample between ECE and WE countries. Figures 4, 5 confirm our first (integrated) findings, namely, that the higher the levels of polarization, the lower the levels of democracy, and vice versa (see also Supplementary Tables S1,S2 in Supplementary Appendix SB)6.

FIGURE 4. Polarization and different aspects of democracy, East Central Europe. Source: Author’s own elaboration based on Rama and Casal Bértoa (2020). Notes: Polarization is statistically significant in all of the models (p value < 0.05), with the exception of egalitarian democracy (p value < 0.068). The models include the following controls: Gross Democratic Product, Gross Democratic Product growth, Effective Number of (Electoral) Parties (Laakso and Taagepera’s index), electoral disproportionality (Gallagher’s index), type of regime (semi-/presidential vs parliamentary), total electoral volatility (Pedersen’s index), years of democracy as well as country and years dummies. These are marginal effects calculated after linear regressions. We include elections since 1950 and exclude outliers (i.e., with values above 55% of votes for APEp). Plots show the marginal effects calculated after linear regressions (OLS) with country and year dummies.

FIGURE 5. Polarization and different aspects of democracy, Western Europe. Source: Author’s own elaboration based on Rama and Casal Bértoa (2020). Notes: Polarization is statistically significant in all of the models (p value < 0.01). The models include the following controls: Gross Democratic Product; Gross Democratic Product growth, Effective Number of (Electoral) Parties (Laakso and Taagepera’s index), electoral disproportionality (Gallagher’s index), type of regime (semi-/presidential vs parliamentary), total electoral volatility (Pedersen’s index), years of democracy as well as country and years dummies. We include elections since 1950 and exclude outliers (i.e., with values above 55% of votes for APEp). These are marginal effects calculated after linear regressions (OLS) with country and year dummies.

As it can be observed in each of the five graphs displayed above, in both Figures, polarization and democracy are certainly at odds. Even if the negative impact of polarization is higher in some dimensions (e.g., electoral and liberal) than others (e.g., participatory), it is clear that in polarized polities democracy always suffers, no matter the dimension we look at. Thus, our results demonstrate that rather than an opportunity or corrective for the malfunctioning of democracy, the recent rise in electoral support for APEp in Europe constitutes a real threat to the quality of liberal democracies (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2012).

Traditionally, when trying to understand the causes of polarization scholars have looked at three different types of explanations: economic, institutional, and cultural. For some, the rise in support to extremist parties and the consequent increase in the levels of polarization are caused by poor economic development and, especially, important economic crisis (e.g., Great Depression and Great Recession). The basic idea is that under unfavorable economic conditions voters will blame those in charge of the economy, turning their heads onto those leaders who propose an alternative, most often radical, solutions (Funke et al., 2016; Dalio et al., 2017; Casal Bértoa and Weber, 2019). As a result, and given the magnitude of the 2008 global financial and economic crisis, it is not surprising that the level of polarization exponentially increased during the last decade, especially in those countries most affected by the crisis (e.g., Spain, Greece, Cyprus, and Italy).

Still, for others, it is the crisis of traditional political parties that should be blamed. Building on the well-known “cartel party” thesis, scholars have shown how the “collusion” of mainstream political parties and their move towards centric positions have left the fringes of the political spectrum empty, giving political outsiders and those traditionally considered “pariah” parties a chance to represent those sectors of the electorate holding more extreme political views (Katz and Mair, 2018).

Similarly, and because (fruit of the Europeanization and globalization processes experienced during the most recent decades) national governments have seen their sovereignty on economic issues (e.g., inflation, tax reforms, etc.) taken away, political competition has become more and more centered around cultural issues (e.g. abortion, migration, etc.), which tend to be less prone to compromise. The result has been an increase in the level of social and political polarization, especially caused by the reaction of traditionally conservative sectors to the “imposition” of socially liberal values (Hooghe and Marks, 2018). In this line, there are several studies contending that cultural, rather than economic and institutional, factors are responsible for the increase in the electoral support of populist parties. Inglehart and Norris, who have insistently claimed that “the surge in votes for populist parties can be explained not as a purely economic phenomenon but in large part as a reaction against progressive cultural change” (Inglehart and Norris, 2016: 23), and that “today the most heated political issues in Western societies are cultural” (Norris and Inglehart, 2019: 50), are perhaps the best exponents of this school of thought.

In a recent contribution to the debate, Casal Bértoa and Rama (2020), inspired by the American (Dalton and Wattenberg, 2000; Dalton et al., 2011) and European (van Biezen, 2004; Mair, 2013) schools of thought, found that both institutional and cultural theories are complementary rather than contradictory. Both the crisis of traditional political parties and social change have led, especially after the Great Recession in 2008, to the high levels of polarization observed in the most consolidated democracies of Western Europe. Moreover, in their historical analysis, which goes back as far as the time of the Second French Republic inaugurated in 1848, they found no association between economic performance and polarization in the region.

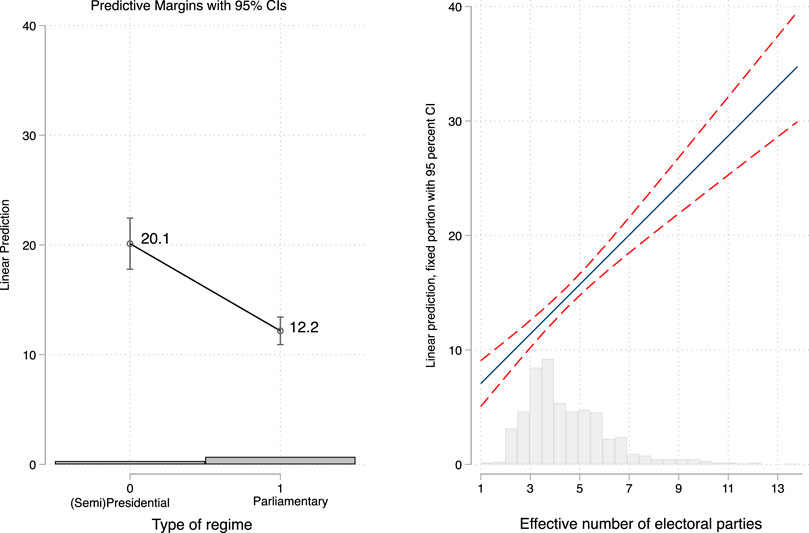

Interestingly enough, they also found that, in comparison to parliamentary regimes, in popular presidential elections—typical of both presidential and semi-presidential regimes—the probability to support APEp is from the 20.1% to the eighth percentile of points higher than in parliamentary systems. This is clearly observable in the left-hand graph of Figure 6 (see Supplementary Table S3 in Supplementary Appendix SB), where 0 stands for (semi-) presidential regimes and one for parliamentary ones (database with 707 elections and 44 European countries). This is so because popular presidential elections increase the probability not only of political outsiders entering the electoral race but also of the personalization of politics, which, as we know, has reached unparalleled extremes in most European countries.

FIGURE 6. Types of regimes, electoral fragmentation, and polarization in 44 European democracies, 1849–2019. Source: Author’s elaboration. Note: marginal effects are graphically displayed after running an OLS with country fixed effects (see Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Appendix SB). The number of cases (elections) is 707 for 44 European countries. The variables included in the models are as follows: GDP growth, electoral disproportionality, electoral fragmentation, type of regime (0 = presidential or semi-presidential; 1 = parliamentary), and years of democracy.

While the previous finding, regarding the effect of type of regime on polarization, constitutes a vindication to Linz’s (1990a), Linz’s (1990b) seminal work (i.e., by increasing the degree of polarization presidential regimes are prone to cause democratic instability), the graph on the right-hand side in Figure 6 confirms Sartori’s (1976) most notorious fears: namely, that higher levels of electoral fragmentation comprise a great risk for democracy, as they lead to higher levels of polarization in a party system. In this sense, following Casal Bértoa and Rama’s (2020) previous findings, but expanding our data to all the European countries (44 countries, 707 elections from 1849 to 2019), we confirm that the relationship between both, the regime type (presidentialism) and the electoral fragmentation (atomized party systems) with the support for APEp is not a Western European thing, but goes beyond their borders. The generalization of these findings is definitely, after the abovementioned analysis, more robust.

Scholars have traditionally considered mainstream parties’ strategies toward APEp to be two-fold: inclusion and exclusion or, in Shakespearean terms, to engage or not to engage? Among the latter, demonization and the application of a discriminatory policy of cordon sanitaire as well as the so-called nuclear option, that is legal restrictions, are the most popular. Among the former, co-optation and collaboration, which here we treat as part of the same strategy of accommodation, are the two main tactics. A fourth, bolder strategy (i.e., regeneration) falls in between.

Regarding the second type of the proposed measures (i.e., exclusion or banning), the cases of Turkey or Spain clearly show how the prohibition of APEp can dramatically failed, as the banning of the Welfare/Virtue parties in the former or Herri Batasuna and its various spin-offs in Spain ended up giving wings to their heirs: AKP and EH Bildu, respectively. In the same vein, and as the case of the Sweden Democrats and Front National show, the application of a cordon sanitaire is also questionable due to what could be called a “boomerang effect”. To this extent, marginalized as an option for government and exploiting their status as self-proclaimed “martyrs” of democracy, political discrimination by mainstream parties may help to increase APEp’ electoral attractiveness.

In terms of inclusion, the incorporation of anti-political-establishment forces into the Austrian, Belgian, Finish, and Italian governments did not succeed either. Far from moderating them, they ended up adopting more extreme ideological positions. And the same can be said regarding the adoption of APEp’s radical demands in terms of immigration, judicial reform, etc. (Casal Bértoa, 2017).

Why have all these measures continuously failed? Bearing in mind what we have already said, the answer can only be one: they were totally out of focus. Thus, while we have demonstrated that the rise of populism is a real threat to democracy, we have also shown how the crisis of traditional political parties is partially to be blamed for the former. In fact, by focusing on the symptom (i.e., APEp), rather than the cause (i.e., mainstream parties), the abovementioned measures were doomed to fail from the start.

Conversely, if we are to help to revitalize representative democracy and combat APEp’s recent success, it is essential that any potential remedies focus on the regeneration of mainstream political parties. Moreover, if political forces such as the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom or the Republican Party in the United States or want to overcome Brexit and Trumpism, respectively, they should apply the seven “regenerative” remedies we recently proposed in an article published in the Journal of Democracy (2021), Casal-Bértoa and Rama (2021).

First of all, parties must build strong, institutionalized organizations that allow them to create professional structures capable of resolving internal conflicts, making good decisions, and maintaining close links with their voters and supporters. We are not talking about reconstructing parties as mass organizations, that era is gone and will never come back, but about making parties less state-dependent and more socially representative and adaptable.

Secondly, political forces must be responsive, in the sense of pursuing policies that are consistent with their electoral promises. This will help them not only to regain the lost trust of the electorate but also to regain their traditional role as mediators between society and the state.

A third measure, in assent with this line of thought, requires political parties to be responsible and avoid falling into the populist trap of offering “easy solutions to difficult problems” as irresponsibility leads to greater irresponsibility and so on.

Transparency would be the fourth dose political parties need in order to recover voters’ trust. Given that in many European countries, both East and West, corruption has allowed populism to emerge and look like a viable option, parties must keep their finance clean, letting voters know where their money comes from and how it is spent.

Fifth, it is important that political parties take a long-term perspective. Parties should not just think about the next election poll or the next electoral contest. If there is one thing voters find confusing, it is the volatile behavior of political parties. Parties should have a long-term (policy) perspective and don’t let their decision depends on which way the wind blows. Moreover, thinking long-term often entails a greater element of political responsibility and commitment to future generations.

Parties must also understand that political compromise is at the heart of the democratic game. So much so that the democratic system has a better reputation in those countries where political parties have managed to reach agreements on a number of key issues (e.g., education, pension system, and immigration). Agreement-building and party bonding, moreover, will smoothen tensions among voters as well as temper the recently high levels of polarization.

Last but not least, and because institutional change alone is not enough, it is important that political leaders themselves, international organizations, practitioners, educators, and, last but not least, media play an educative role that incentivizes the understanding of democracy not as a “zero-sum-game” but as a plural ground where constructive debate and respect for the other (not just his/her ideological positions, but also as individual) is essential. The alternative is not Orban’s Hungary but Ardern’s New Zealand.

Representative democracy is in crisis. Party government is being challenged. As we have seen, electoral support for APEp has never been higher. Populism is on the rise and support for illiberal variants of democracy and authoritarianism has never been so popular. In many European countries (e.g., Poland, Czechia, Spain, and Greece) the level of democratic quality has exponentially decreased, in others, democracy has collapsed (e.g., Hungary and Turkey). While the specter of the inter-war period is haunting Europe, a similar phenomenon can be observed in other consolidated democracies like the United States, India, or Israel. For that reason, it is important that academics, as well as practitioners, try to understand what is that got us here and how we can get out of this mess.

This article not only synthesizes and expands part of our previous work but constitutes also an attempt to set a new research agenda. In relation to the former, and building on a unique dataset going back more than 170 years, this article has shown how 1) the electoral success of populist and another APEp has a negative impact on the functioning of democracy; and 2) traditional mainstream parties are to be blamed, along with sociological changes, for the rise in support for APEp.

Trying to look into the future, and after reflecting on how banning or treating populist parties with contempt of disdain is a partial and/or temporal solution at best, this article suggests that only regeneration of mainstream political parties will help to solve the crisis of representative democracy and party government we are currently in. For that, we propose seven different revitalizing doses that, if properly applied, might serve as an “anti-APEp” antidote.

When the COVID-19 global heal crisis began, many were the academics and practitioners who started to claim that the end of the populist wave was near. Especially given the poor management of the crisis in countries governed by populist leaders (e.g., the US, Mexico, Brazil, and the United Kingdom). Unfortunately, nothing seems to be further from reality. As seen in recent elections (e.g., Kosovo and Netherlands) and electoral forecasts (e.g., France), support for APEp continues to be on the rise. For this reason, it is more urgent than ever to understand which remedies will be able to decrease polarization, help to combat the anti-establishment challenge, and revitalize liberal democracy.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://whogoverns.eu/

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.687695/full#supplementary-material

1Other alternative indicators of polarization (e.g. Dalton’s index) are not available for most party systems before 1945. Still, the correlation between our proxy and Dalton’’s index for those party systems with available data is 0.7 (Casal Bértoa and Enyedi, 2021: 194). See Supplementary Appendix SA to better understand the measure of % of votes for APEp. The complete list of the parties categorized as APEp by election and country is available at https://whogoverns.eu/party-systems/polarization/ (Casal Bértoa, 2021).

2Centrifugal tendencies arise when the parties to each side of the centre party attempt to lure voters away from the centre party by moving away from it.

3The ideational approach stresses the following three characteristics of populism: “1) a Manichean and moral cosmology; 2) the proclamation of the people as a homogenous and virtuous community; and 3) the depiction of “the elite” as a corrupt and self-serving entity” (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser 2018: 3).

4The five selected dimensions of democracy are consistent with the five principal components of democracy underlined by Coppedge et al. (2018). By addressing these particular dimensions, we are able to cover the concept of democracy as a whole.

5Looking to directly present our results, we opt for a non-canonical academic practice: namely, to exclude a section of “data and methods” in the article. However, for those interested in a detailed explanation of both, a justification of why to include the above-mentioned control variables and their operationalization, please see Supplementary Appendix SA. In the next section we again do not include a discussion about how to control for type of regime, years of democracy, electoral disproportionality and GDP growth. The operationalisation and justification of this is also included in Supplementary Appendix SA.

6See Supplementary Tables S1–S3 in the Supplementary Appendix SB and Figures 4–6

Abedi, A. (2004). Anti-Political Establishment Parties. A Comparative Analyses. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203625064

Abedi, A. (2002). Challenges to Established Parties: The Effects of Party System Features on the Electoral Fortunes of Anti-political-establishment Parties. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 41, 551–583. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.t01-1-00022

Binder, S. (2008). Going Nowhere: A Gridlocked Congress. Brookings Rev. 18 (1), 16–19. doi:10.1111/j.1937-8327.1989.tb00409.x

Berg-Schlosser, D., and Mitchell, J. (Editors) (2000). Conditions of Democracy in Europe, 1919-1939: Systematic Case Studies. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Bischof, D., and Wagner, M. (2019). Do Voters Polarize when Radical Parties Enter Parliament? Am. J. Polit. Sci. 63 (4), 888–904. doi:10.1111/ajps.12449

Bornschier, S. (2019). Historical Polarization and Representation in South American Party Systems, 1900-1990. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49 (1), 1–27. doi:10.1017/s0007123416000387

Capoccia, G. (2005). Defending Democracy: Reactions to Extremism in Interwar Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casal Bértoa, F. (2017). Representative Politics in an Era of Everyday Mobilisation. openDemocracy. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/representative-politics-in-era-of-everyday-mobilisation/ (Accessed June 20, 2021).

Casal Bértoa, F. (2021). Database on WHO GOVERNS in Europe and beyond, PSGo. Available at: whogoverns.eu (Accessed June 20, 2021). doi:10.1057/s41304-021-00342-w

Casal Bértoa, F., and Enyedi, Z. (2021). Party System Closure: Party Alliances, Government Alternatives and Democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198823605.001.0001

Casal Bértoa, F., and Rama, J. (2020). Party Decline or Social Transformation? Economic, Institutional and Sociological Change and the Rise of Anti-Political-Establishment Parties in Western Europe. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 12 (4), 503–523. doi:10.1017/s1755773920000260

Casal Bértoa, F., and Rama, J. (2021). The Antiestablishment Challenge. J. Democracy 32 (1), 37–51. doi:10.1353/jod.2021.0014

Casal Bértoa, F., and Weber, T. (2019). Restrained Change: Party Systems in Times of Economic Crisis. J. Polit. 81 (1), 233–245. doi:10.1086/700202

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S. E., Teorell, J., et al. (2018). “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset V8". Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3172795

Dalio, R., Kryger, S., Rogers, J., and Gardner, D. (2017). Populism: The Phenomenon, 203. Bridgewater: Daily Observations, 226–3030.

Dalton, R. J., Farrell, D. M., and McAllister, I. (2011). Political Parties and Democratic Linkage How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199599356.001.0001

Dalton, R. J. (2008). The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems. Comp. Polit. Stud. 41 (7), 899–920. doi:10.1177/0010414008315860

Dalton, R. J., and Wattenberg, P. M. (2000). Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eatwell, R. (2017). “Populism and Fascism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Editors C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. A. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 363–383.

Enyedi, Z. (2016). Populist Polarization and Party System Institutionalization. Probl. Post-Communism 63 (4), 210–220. doi:10.1080/10758216.2015.1113883

Funke, M., Schularick, M., and Trebesch, C. (2016). Going to Extremes: Politics after Financial Crises, 1870-2014. Eur. Econ. Rev. 88 (C), 227–260. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.03.006

Gallagher, M. (1991). Proportionality, Disproportionality and Electoral Systems. Elect. Stud. 10 (1), 33–51. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(91)90004-c

Galston, W. A. (2018). The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy. J. Democracy 29 (2), 5–19. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0020

Hawkins, K. A., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). “Introduction,” in The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis. Editors KA Hawkins, RE Carlin, L Littvay, and C Rovira Kaltwasser (New York: Routledge), 1–24. doi:10.4324/9781315196923-1

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage Theory Meets Europe's Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage. J. Eur. Public Pol. 25 (1), 109–135. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

Inglehart, R., and Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. Harvard Kennedy University: HKS Working Paper, 16–026.

Karvonen, L., and Quenter, S. (2003). “Electoral Systems, Party System Fragmentation and Government Instability,” in Authoritarianism and Democracy in Europe, 1919–1939. Editors D Berg-Schlosser, and J Mitchell (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 131–162.

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (1995). Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party. Party Polit. 1 (1), 5–28.

Katz, R. S., and Mair, P. (2018). Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199586011.001.0001

Kitschelt, H., and McGaan, A. J. (1995). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Kriesi, H., and Pappas, T. S. (2015). European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. United Kingdom: ECPR.

Laakso, M., and Taagepera, R. (1979). Effective Number of Parties. A Messure with Applications to West Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 12 (4), 3–27. doi:10.1177/001041407901200101

Lane, J.-E., and Ersson, S. (2007). Party System Instability in Europe: Persistent Differences in Volatility between West and East? Democratization 14 (1), 92–110. doi:10.1080/13510340601024322

Linz, J. J. (1978). The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis, Breakdown, and Reequilibration. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Linz, J. J. (1990b). The Virtues of Parliamentarism. J. Democracy 1 (4), 84–91. doi:10.1353/jod.1990.0059

Loomes, G. (2011). Party Strategies in Western Europe: Party Competition and Electoral Outcomes. London: Routledge.

Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. New York and London: Verso Books. doi:10.4324/9780203061701

Morlino, L., and Raniolo, F. (2017). The Impact of Economic Crisis on Southern European Democracies, the New Protest Parties. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52371-2

C. Mudde, and C. Rovira Kaltwasser (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Correction or Threat for Democracy? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108595841

Pedersen, M. N. (1979). The Dynamics of European Party Systems: Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility. Eur. J. Polit. Res 7 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1979.tb01267.x

Pennings, P. (1998). “The Triad of Party System Change: Votes, Office and Policy,” in Comparing Party System Change. Editors P. Pennings, and J. Lane (London: Routledge), 79–100.

Powell, G. B. (1982). Contemporary Democracies: Participation, Stability and Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rama, J., and Casal Bértoa, F. (2020). Are Anti-Political-Establishment Parties a Peril for European Democracy? A Longitudinal Study from 1950 till 2017. Representation 56 (3), 387–410.

Reiljan, A. (2020). 'Fear and Loathing across Party Lines' (Also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59 (2), 376–396. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S. L., Halikiopoulou, D., et al. (2020). The PopuList 2.0: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. Available at: https://popu-list.org (Accessed June 20, 2021).

Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-Democracy: Politics in an Age of Distrust. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511755835

Sani, G., and Sartori, G. (1983). “Polarization, Fragmentation and Competition in Western Democracies,” in Western European Party Systems. Editors H Daalder, and P Mair (Bavery Hills: Sage).

Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singer, M. (2016). Elite Polarization and the Electoral Impact of Left-Right Placements: Evidence from Latin America, 1995-2009. Latin Am. Res. Rev. 51 (2), 176. doi:10.1353/lar.2016.0022

van Biezen, I. (2004). Political Parties as Public Utilities. Party Polit. 10 (6), 701–722. doi:10.1177/1354068804046914

van Kessel, S. (2015). Populist Parties in Europe: Agents of Discontent? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wilford, A. M. (2017). Polarization, Number of Parties, and Voter Turnout: Explaining Turnout in 26 OECD Countries. Soc. Sci. Q. 98 (5), 1391–1405. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12366

Wolinetz, S., and Zaslove, A. (2018). Absorbing the Blow. Populist Parties and Their Impact on Parties and Party Systems.London, United Kingdom: ECPR press.

Xezonakis, G. (2012). Party System Polarization and Quality of Government: On the Political Correlates of QoG. Working Paper de The Quality of Government Institute, 14.

Zagorski, P., Rama, J., and Casal Bértoa, F. (2021). Preaching in the Desert or Leading to the Promised Land? The Effects of Anti-Political-Establishment Parties and Party System Fragmentation on Electoral Turnout. Manuscript prepared for a Special Issue in West European Politics on “European Politics Under Pressure: Polarization and the Dynamic of Electoral and Protest Participation”.

Keywords: polarization, populism, anti-political establishment, political parties, democracy

Citation: Casal Bértoa F and Rama J (2021) Polarization: What Do We Know and What Can We Do About It?. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:687695. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.687695

Received: 29 March 2021; Accepted: 18 May 2021;

Published: 30 June 2021.

Edited by:

Jorge M. Fernandes, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Constanza Sanhueza, Social Science Research Center Berlin, GermanyCopyright © 2021 Casal Bértoa and Rama. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fernando Casal Bértoa, RmVybmFuZG8uQ2FzYWwuQmVydG9hQG5vdHRpbmdoYW0uYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.