94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 08 April 2025

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1483905

This article is part of the Research TopicPractices for Gender Equality: Teachers' Sense of EfficacyView all 3 articles

Introduction: Gender-responsive education plays a crucial role in fostering equitable learning environments. Despite Morocco’s legal and institutional efforts to promote gender equality, the integration of gender-sensitive teaching practices remains inconsistent. This study assesses the attitudes and competencies of Moroccan teaching staff, including trainee teachers, regarding gender-responsive education.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was employed to evaluate gender knowledge and awareness, the application of gender-responsive teaching strategies, and the development of gender-related behaviors. The Teacher’s Gender Equality Competence Scale (TEGEP) was administered to 242 participants, primarily from teacher training institutions. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis to identify key trends and relationships.

Results: The findings reveal diverse perspectives on gender equality in education. While some participants exhibit strong self-efficacy in applying gender-responsive teaching methods, others demonstrate limited awareness and preparedness. Variations in competency levels are influenced by educational background and teaching experience, highlighting both strengths and areas requiring improvement.

Discussion: These results emphasize the need for targeted professional development programs to strengthen teachers’ gender-responsive competencies. Enhancing both initial training and continuous professional learning is crucial for embedding gender-sensitive pedagogy effectively within Moroccan classrooms.

Since the 1990s, Morocco has embarked on a series of reforms, particularly following its signing of the international Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women “CEDAW” agreement in 1993 Moroccan Official Gazette No. 4866 (2000), “January 18, 2000.” These reforms have spurred legislative and institutional progress toward enhancing human rights and gender equality. Key reforms include the 2004 Family Code reform, amendments to nationality laws, and the adoption of affirmative action measures in elections, among others. These legislative reforms were further reinforced with the adoption of a new constitution in 2011, which introduced provisions and principles related to gender equality. Notably, the Kingdom of Morocco affirmed its commitment, within the preamble of this constitution, to “prohibit and combat all forms of discrimination based on gender, color, belief, culture, social or regional origin, language, disability, or any personal situation, regardless of the cause.” Article 2.6 emphasizes that “public authorities work to ensure conditions that guarantee actual freedom and equality between citizens, engaging them in political, economic, cultural, and social life.” [Official Gazette No. 5964 bis (June 30, 2011)].” Article 1.19 guarantees men and women equal rights and freedoms in civil, political, economic, social, cultural, and environmental domains, as stipulated in the constitution, its provisions, and international agreements ratified by Morocco. The state endeavors to achieve equality between men and women (Article 2.19) and mandates public authorities to establish a body for equality and combating all forms of discrimination (Article 3.19). Article 30 states that “the law includes measures to encourage equal opportunities between women and men in accessing elected positions,” among other constitutional provisions supporting a gender-sensitive approach. These developments paved the way for the enactment of further legislation in this direction, such as Law No. 79–14 issued on December 21, 2017, concerning the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Authority, and Law No. 103–13 on combating violence against women, which entered into force in September 2018.

Relevant to the educational context in Morocco is Framework Law No. 51.17 of 2019 concerning the education, training, and scientific research system. This law fundamentally aims to establish an inclusive education system open to all, focusing on human capital development grounded in principles of equality and equal opportunities on one hand, and quality education for all on the other. Article 4 outlines the pillars for achieving these objectives, emphasizing compliance with principles of equality, fairness, and equal opportunities in accessing various components of the education system and delivering services to learners of divers backgrounds. This aligns with principles of gender-sensitive approaches aimed at closing gender gaps in access to resources and services.

However, amidst the noble aspirations outlined in Morocco’s constitutional, legislative, and educational policy framework, Morocco still occupies positions below desired levels in international rankings related to human development and gender equality. Despite the recent Global Human Development Report 2024/2023 issued by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) revealing Morocco’s rise by three ranks in the global Human Development Index (HDI), improving from 123rd to 120th place, Morocco ranks 136th in the Global Gender Gap Index according to the World Economic Forum 2022.

Looking at Global Education Monitoring Report Team (2024) perspective in this context, the organization emphasizes the importance of education as a tool for changing social norms and achieving equality. UNESCO advocates that education should be a driver for social change and equity by creating educational environments that enable everyone to reach their full potential. The topic of gender-responsive education has been extensively studied and researched globally since the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1979. Education has been recognized as a key tool to address gender inequality, emphasizing the need to mainstream a gender perspective in education to ensure that all graduates are prepared to develop practices that consider gender differences. This contributes to achieving comprehensive and sustainable growth and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.

One of the significant studies in measuring self-efficacy in gender-responsive education is titled “Training Future Teachers for Sustainable Practice in Achieving Gender Equality: Design and Validation of the Self-Efficacy Scale” (TEGEP scale), conducted by Cardona-Moltó and Miralles-Cardona (2022) at the College of Education, Institute of University Gender Studies, University of Alicante, Spain. This study provides a valuable contribution to education and gender studies by developing a reliable tool for measuring self-efficacy in gender-sensitive education. Results indicated the need for enhanced training and awareness of gender issues to ensure gender equality in education. Similarly, Ioanna and Cardona-Moltó (2022) conducted a study in Greece focusing on student perceptions using the Training Evaluation Gauge for Gender Equality, revealing predominantly neutral opinions among university students. The study underscored the necessity for institutional support and curriculum development for effective implementation of gender mainstreaming in higher education.

Building on this foundation, Mukagiahana et al. (2024) examined the impact of teacher training in gender-responsive pedagogy in Rwanda. The study found that over 80% of mathematics and science teachers reported improved application of gender-responsive practices post-training. However, addressing gender stereotypes and fostering gender-neutral communication remained less successful, highlighting persistent challenges in gender-sensitive pedagogy.

Further, Cardona et al. (2023) expanded their investigation into STEM teacher preparation in Greece and Spain. While Greek students showed higher confidence in gender knowledge, Spanish counterparts excelled in promoting gender-sensitive attitudes. This emphasizes systemic disparities and the need for more structured gender training in teacher education.

Moreover, Pedrajas and Jalandoni (2023) identified significant challenges in the Philippines, such as bullying and a lack of gender awareness among tertiary educators. Their findings stressed the importance of institutional frameworks and practical strategies, such as storytelling and small group discussions, to address inequality in classrooms effectively.

Lastly, the Global Partnership for Education (2023) emphasized the role of teachers as critical agents of change in achieving gender equality. It advocated for comprehensive policy support and institutional reforms to empower educators in fostering inclusive, gender-sensitive learning environments globally.

These studies collectively illustrate the ongoing need for training, institutional support, and curriculum enhancement to address the multifaceted challenges of achieving gender equality in education.

In the context of Morocco, despite numerous studies addressing gender approaches in educational contexts, there has been no study identified that utilizes the TEGEP scale within Moroccan education. UNESCO’s case study “Promoting Gender Equality in Education: A Case Study of Morocco” (UNESCO, 2016) in UNESCO Education Reports discussed governmental policies and supportive programs aimed at improving educational opportunities for girls.

Here lies the importance of our study, which relies on the Self-Efficacy Scale for implementing a gender approach among a random sample of teaching staff in Morocco, especially those still in training at regional centers for education and training, the majority of whom belong to the primary education sector. Today, there is a unique opportunity to revive the topic of gender-responsive education in Morocco within the framework of the United Nations Collaboration for Sustainable Development 2023–2027 (CCDD), informed by a new development model and lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach targets four strategic pillars to promote sustainable development in Morocco (comprehensive and sustainable economic transformation first, human capital development second, comprehensive social inclusion and protection third, and good governance fourth). This approach not only aligns with broader sustainable development goals but also reflects a commitment to addressing systemic inequality and promoting equal opportunities for all.

By diagnosing the perceptions and readiness of a sample of teaching staff and trainee students at regional centers for education and training in Morocco regarding their beliefs about and preparedness for gender-responsive education in the Moroccan educational context, especially at the primary level, this study contributes to addressing the identified gap in relevant scientific research in this field.

UNESCO defines gender-responsive education as an integral part of curricula at all levels of the educational system. It enables girls and boys, women and men alike, to understand how gender compositions and models of social role assignment impact their lives, relationships, life choices, and career paths. As education is considered a fundamental tool to address gender inequality, the rankings achieved by Morocco in such classifications may indicate gaps in teachers’ awareness and knowledge of gender issues, their readiness to implement teaching methods responsive to this approach, and their preparedness to develop behaviors related to it. This is where the problem lies.

Therefore, it becomes necessary to assess the awareness of Moroccan teachers, both experienced educators and student trainees, of gender equality principles using the Teacher Competency in Gender Equality Practices (TEGEP) scale.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the self-efficacy of teachers, particularly trainee teachers, in Morocco in promoting a gender-responsive approach within the Moroccan education system, especially at the elementary level. We hypothesize that there are variations among teaching staff regarding their self-assessment of awareness and knowledge of gender issues and their readiness to implement teaching methods that are responsive to gender equality, as well as their readiness to develop behaviors associated with gender issues.

The sample included 242 participants, including 159 individuals working in primary education, with a significant proportion being trainee teachers at regional centers for education and training. Participants consisted of 72.2% females and 27.0% males, predominantly aged between 20 and 25 years (51.2%). The second largest age group comprised individuals aged 26–30 years (34.3%), while other age groups represented a smaller percentage of participants (14.5%), distributed across age categories from 31 to over 46 years.

In terms of educational attainment, the vast majority of participants held a bachelor’s degree (84.3%), with a small percentage holding higher degrees: master’s (12.4%) and doctoral (3.3%).

Regarding employment status, the largest proportion of participants were part-time students (43.8%), followed by part-time workers (24.0%) or belonging to the “other” category (16.1%). A small percentage of participants worked full-time (8.3%) or were full-time students (7.9%).

It should be noted that According to Decree No. 672-11-2 (issued in 2011) regarding the establishment and organization of Regional Centers for Education and Training Professions, as amended and supplemented, candidates accepted for teacher qualification training at these regional centers include: Candidates who hold at least a Bachelor’s degree in university education tracks or its equivalent, and are not older than 45 years of age at the time of the competition; and candidates who hold at least a Bachelor’s degree, Bachelor of Basic Studies, Professional Bachelor’s degree, or its equivalent, and are not older than 45 years of age at the time of the competition, and possess theoretical and scientific qualifications similar to those in university education tracks. This is after undergoing initial selection, the organization of which is determined by decision of the governmental authority responsible for national education.

Trainee teachers at the Regional Center for Education and Training receive educational qualification in teaching professions according to each track (elementary, middle school, or high school), in addition to practical training within educational and training institutions, and complementary qualification in specialized subjects based on competency descriptions (Article 26). The duration of training in these teacher qualification tracks is a full academic year, culminating in obtaining the educational qualification certificate specific to the chosen track (Article 25).

The study adopted a mixed-methods approach utilizing both quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques, employing the Teacher Competency in Gender Equality Practices (TEGEP) scale developed by Mireles Cardona et al. (2022). This tool measure the effectiveness and competency of teachers in promoting gender equality within the educational environment. The scale assesses knowledge, attitudes, and educational practices contributing to the creation of a fair and inclusive educational environment for both genders.

The scale’s validity is supported by rigorous factor analysis, ensuring that it accurately measures what it intends to (i.e., teachers’ competencies in gender equality practices). Reliability is also confirmed, meaning that the scale consistently produces stable results over time, which enhances its trustworthiness for research use.

The TEGEP scale is designed to be flexible, allowing it to be used across various educational levels—primary, secondary, and even high school settings. Additionally, it can be customized to better fit the cultural and educational contexts of different communities, ensuring relevance and effectiveness.

The scale employs a Likert-type scale for responses, where participants rate their level of agreement with statements regarding gender equality practices. The five-point scale ranges from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree,” offering a nuanced understanding of teachers’ attitudes and practices in gender equality. This approach enables precise measurement of participants’ beliefs and behaviors concerning gender issues.

The significance of our use of the TEGEP scale in the Moroccan context stems from the assumption of its ability to measure the effectiveness of teaching staff in promoting gender equality and identifying areas in need of improvement. Through examining the distribution of opinions using the Likert scale, we can observe the degree of agreement or disagreement with each statement. Additionally, observing the relative distribution across each level in each area provides a deeper insight into individuals’ preferences and opinions regarding gender issues and gender equality.

The data derived from the questionnaire provides a comprehensive overview of the participants’ opinions on gender knowledge and awareness (the first axis), the implementation of gender-responsive teaching methods (the second axis), and the development of gender related behaviors (the third axis). Each of these was evaluated using a six-point Likert scale: category1 means strongly disagree, category2 means somewhat disagree, category3 means disagree, category4 means somewhat agree, category5 means agree, and category6 means strongly agree.

In addition to demographic questions, the survey consists of a total of 26 questions distributed across three dimensions: 11 questions pertaining to knowledge and awareness of gender issues, 10 questions focusing on implementation, and 5 questions addressing development. Items begin with statements such as “I can…” or “I am confident…” or “I am able to…”

The data derived from this survey provide valuable insights into participants’ attitudes and perceptions regarding their competency in teaching with a gender-responsive approach. Each dimension presents responses to the questions using the Likert scale, allowing for quantitative analysis of opinions. Through examining frequency and percentage distributions across different response levels, we can identify prevailing attitudes and distinguish trends in public opinion regarding knowledge and gender awareness, teaching methods responsive to gender, and development of gender-related behaviors.

Data collection methods included using Google Forms, distributing the digital questionnaire via email and WhatsApp groups. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with no incentives provided for study involvement.

The data analysis utilized Pearson correlation coefficients to explore relationships between demographic variables—such as gender, age, educational level, and employment status—and participants’ attitudes toward gender-related issues, including gender equity, gender roles, and associated concepts. This method allowed for a detailed examination of how these variables correlate with various perspectives on gender.

The sample size ranged between 241 and 242 respondents per variable, ensuring adequate representation and statistical power for detecting meaningful correlations. Gender was coded as a binary variable (Femmelle1 or Masculin2), allowing us to examine potential differences in attitudes between male and female respondents. Age was treated as a continuous variable, while educational level and employment status were classified into categories, reflecting a range of backgrounds across these demographic groups.

The results of our study revealed statistically significant positive correlations between several practices and desired educational outcomes. For instance, a strong association was found between “providing equal opportunities for all students” and “planning teaching strategies with a gender perspective” (r = 0.439, p < 0.001), which supports previous studies such as Women’s Health Victoria (2021), highlighting the importance of well-planned teaching strategies in enhancing gender equality. Additionally, the results showed that “integrating gender into curriculum content” was positively correlated with “dismantling gender stereotypes and biases” (r = 0.362, p < 0.001), aligning with the findings of Chan (2022). Furthermore, a positive association was found between “respecting different gendered needs and learning styles” and “creating learning environments that foster gender cooperation” (r = 0.388, p < 0.001), emphasizing the significance of inclusive learning environments in promoting gender cooperation. Regarding “supporting school-community links to promote gender equality,” a strong correlation with “advocacy against all forms of gender injustice” was found (r = 0.587, p < 0.001), reinforcing the role of school-community collaboration in raising awareness and advancing gender justice. Lastly, the results indicated that “collaboration with colleagues in implementing gender equality plans” and “gender education” were both positively associated with “dismantling gender stereotypes and biases” (r = 0.471, p < 0.001 and r = 0.594, p < 0.001, respectively), emphasizing the importance of ongoing teacher collaboration and gender education in promoting a more inclusive learning environment and addressing biases.

The variable representing gender identity (coded as Femmelle1 or Masculin2) showed a weak but statistically significant positive correlation with age (r = 0.167, p < 0.01), suggesting that as respondents’ age increases, their gender identity responses tend to shift slightly. However, gender identity did not show a significant correlation with educational level (r = 0.000, p = 0.994), indicating that educational attainment does not appear to be strongly related to gender identity in this sample. Additionally, gender identity was negatively correlated with job status (r = −0.240, p < 0.01), which suggests that gender identity responses may vary according to the respondent’s employment status.

Age exhibited significant correlations with several gender-related concepts. Notably, age was negatively correlated with Legislation on Gender Equity (r = −0.434, p < 0.001) and Gender Roles (r = −0.443, p < 0.001), suggesting that older respondents tend to hold more traditional views regarding gender roles and the importance of gender equity legislation. On the other hand, age was positively correlated with Gender Equality vs. Gender Equity (r = 0.360, p < 0.001) and Gender Discrimination (r = 0.157, p < 0.05), indicating that older individuals may be more sensitive to the distinction between gender equality and equity and more aware of gender discrimination issues.

Educational level was found to correlate significantly with several gender-related attitudes. Positive correlations were observed between Educational Level and attitudes toward Terminology Related to Gender Issues (r = 0.137, p < 0.05), Gender Parity (r = 0.129, p < 0.05), and Gender Discrimination (r = 0.141, p < 0.05). These findings suggest that individuals with higher educational attainment tend to hold more progressive views on gender-related issues and are more likely to embrace inclusive gender terminology and support gender parity.

Employment status exhibited several significant negative correlations with gender-related issues. For example, there was a significant negative correlation with Gender Parity (r = −0.252, p < 0.01) and Gender Bias (r = −0.236, p < 0.01). These findings suggest that individuals with certain job statuses, particularly those in lower-status or less formal employment, are more likely to hold traditional or conservative views on gender roles, potentially due to the work environments that may not prioritize gender equity.

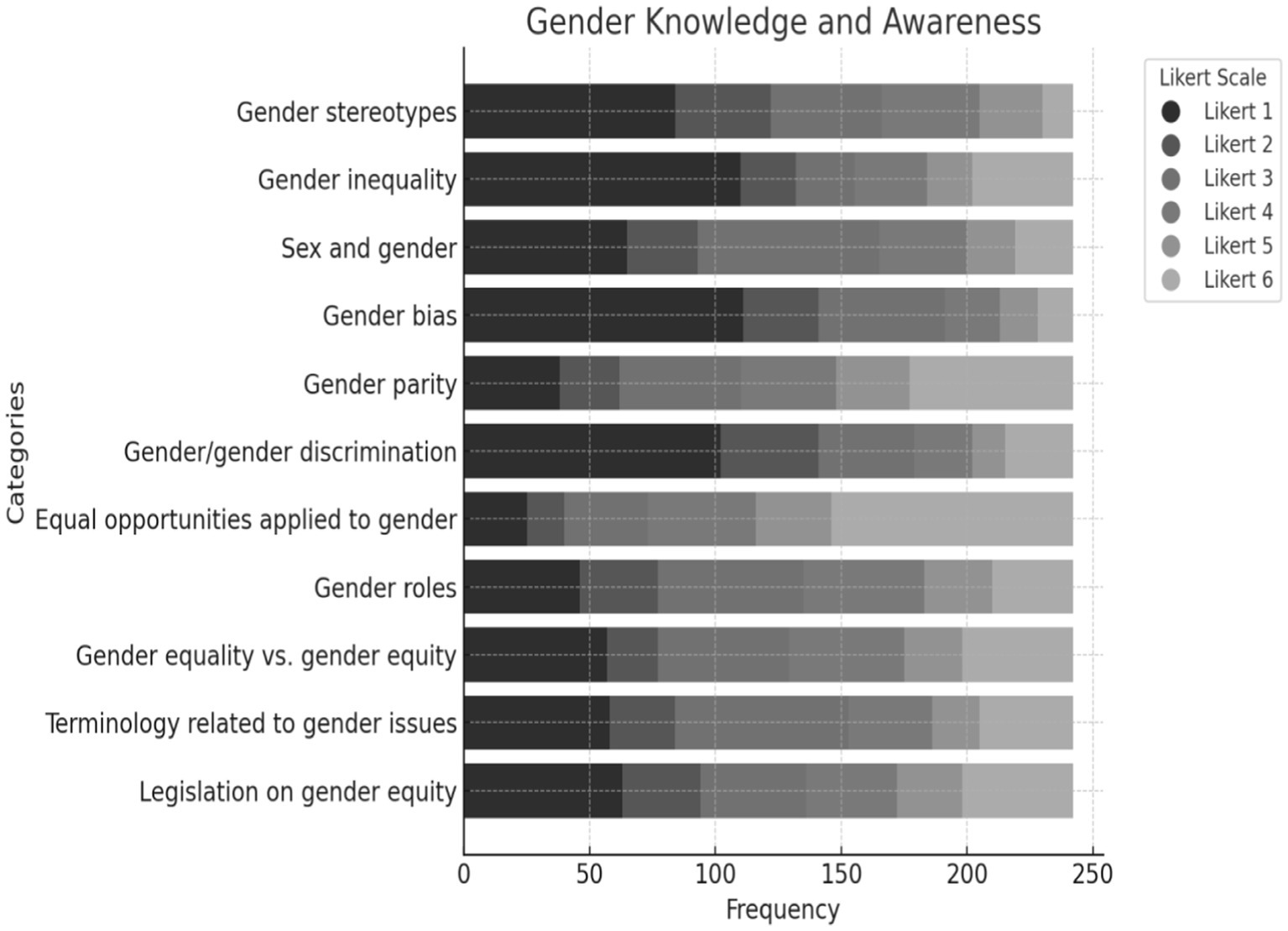

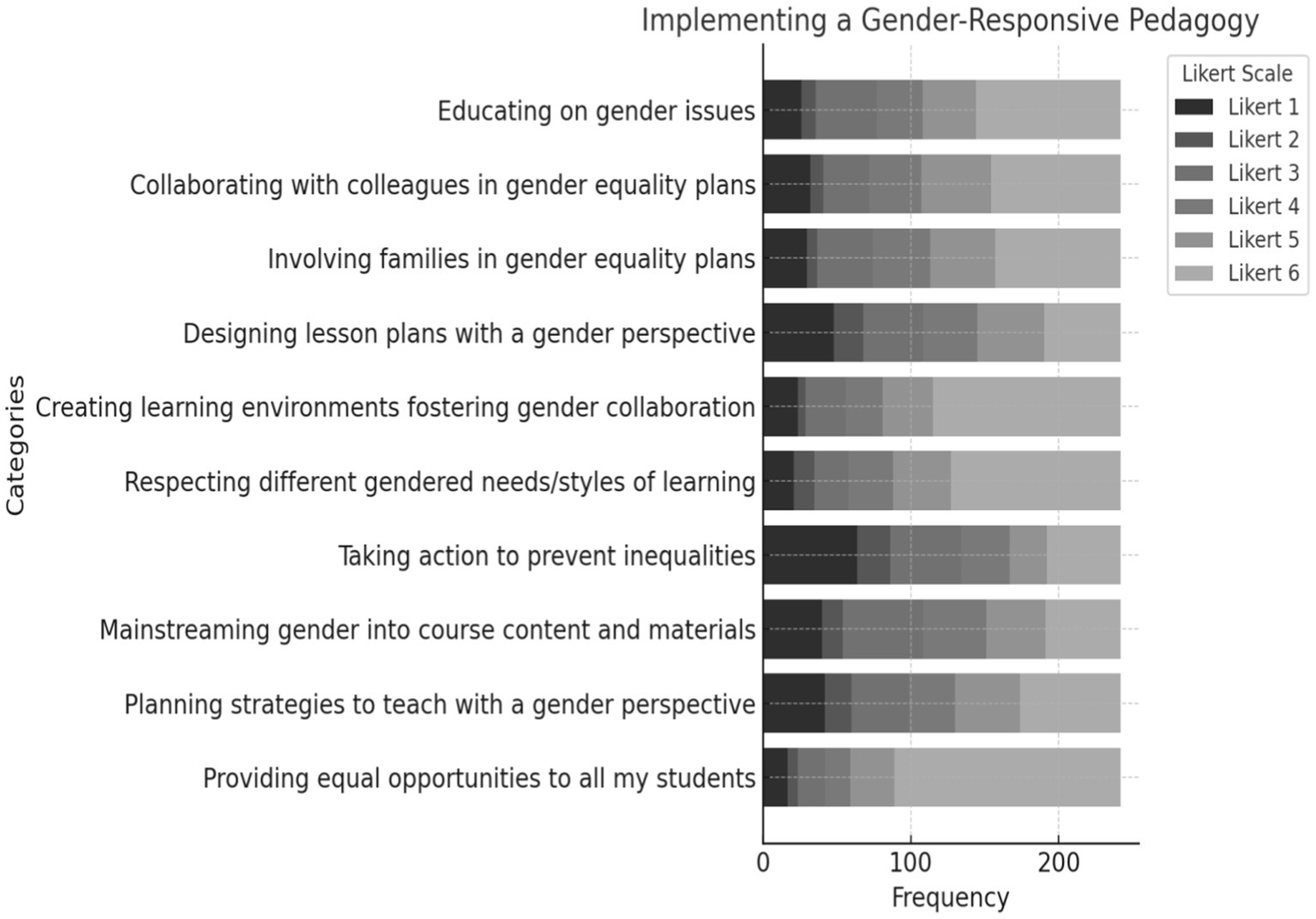

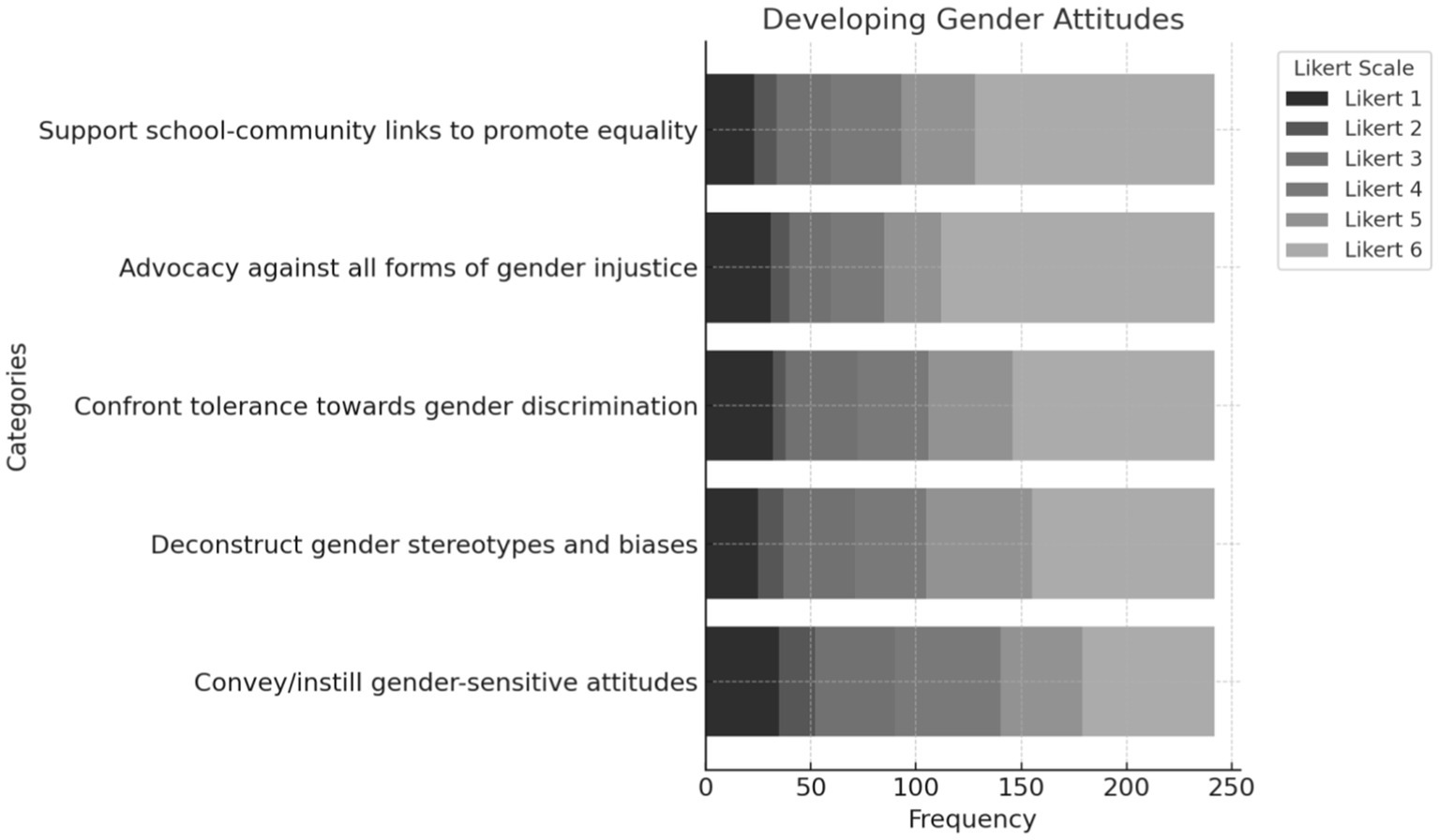

To present the frequency distribution results for each Likert scale rating across the various categories included in the survey’s axes, three composite charts were generated. These charts use gradient colors to represent the six levels of the scale, offering a detailed visualization of how responses are distributed across the categories. The resulting visuals consist of three stacked bar charts (Figures 1–3), each reflecting scores from 1 to 6 for topics within the following axes:

1. Knowledge and Awareness about Gender.

2. Implementing Gender-Sensitive Education.

3. Developing Attitudes toward Gender.

- Figure 1 depicts the distribution of frequencies for scores (1–6) across topics in the “Knowledge and Awareness about Gender” axis.

- Figure 2 illustrates the same distribution for the “Implementing Gender-Sensitive Education” axis.

- Figure 3 highlights the distribution within the “Developing Attitudes toward Gender” axis.

Figure 1. Distribution of frequencies across categories (The 1st axis: Gender knowledge and awareness).

Figure 2. Distribution of frequencies across categories (The 2nd axis: implementing a gender-responsive pedagogy).

Figure 3. Distribution of frequencies across categories (The 3rd axis: Developing gender attitudes).

In each chart, individual bars represent distinct topics, with the horizontal axis displaying frequencies and the vertical axis showing categories.

The Supplementary Material includes tables detailing the questionnaire results for various topics related to participants’ knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and readiness regarding gender issues. Below is a summary of the topics covered:

- Knowledge and Awareness:

- Table 1: Awareness of gender-related terms.

- Table 2: Awareness of legislation on gender equality.

- Tables 3–11: Awareness of concepts such as gender equity, roles, discrimination, parity, bias, stereotypes, and inequality.

- Readiness and Confidence in Education:

- Tables 12–14: Readiness to provide equal opportunities, integrate gender perspectives, and design gender-focused teaching strategies.

- Tables 15–20: Actions to prevent inequalities, respect diverse needs, create collaborative environments, involve families, and work with colleagues on gender equality plans.

- Ability to Address Gender Issues:

- Tables 21–26: Educating about gender issues, dismantling stereotypes, confronting discrimination and violence, and linking schools with communities to promote gender equality.

This comprehensive approach highlights participants’ perspectives on various aspects of gender education and equality, as detailed in the charts and Supplementary Material tables.

The primary goal of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of teachers, particularly trainee teachers in Morocco, in adopting a gender-responsive approach within the Moroccan education system, with a specific focus on primary education. This evaluation is grounded in the reliability of the TEGEP (Teacher-Efficacy for Gender Equality Practice) scale. The results, depicted through the stacked bar charts above, reveal clear patterns in the frequency distribution across the three axes of the study. These patterns shed light on variations among the sample members in three key areas: their self-assessed gender awareness and knowledge, their readiness to apply gender-responsive teaching methods, and their commitment to developing gender-sensitive behaviors.

Previous research has established the TEGEP scale as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing gender-related teaching efficacy. Studies on the Spanish and Greek versions of the scale demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.92 to 0.94 (Miralles-Cardona et al., 2021; Chiner et al., 2023). Moreover, factor analysis confirmed the construct validity of the scale, verifying the robustness of its three subscales—gender knowledge, gender-responsive pedagogy, and gender-sensitive attitudes—across different cultural contexts. Positive and statistically significant correlations among these subscales further support the scale’s validity (Miralles-Cardona et al., 2021; Chiner et al., 2023).

The predominance of female participants in this study aligns with global trends in primary education, where teaching is a female-dominated profession. The notable representation of younger participants suggests a focus on newly qualified or early-career teachers. The high proportion of bachelor’s degree holders reflects the minimum educational requirement, while the limited number of advanced degree holders points to potential areas for capacity building. Additionally, the diversity in employment status among participants highlights the various pathways leading to the teaching profession.

The following is a discussion of the detailed results for each of the questionnaire axes.

The data reveal a range of differing perspectives, as the questions were aimed at their knowledge and awareness of eleven elements, namely: terms related to gender issues, legislation related to gender equality, gender equality versus gender equity, gender roles, the application of equal opportunities to gender, gender discrimination, gender parity, gender based bias, sex and gender, gender inequality, and gender stereotypes.

Understanding and awareness of terminology related to gender issues are crucial for effective and constructive teaching approaches toward achieving social gender equality. Key terms include Gender and Gender Identity, Gender Expression, Sexism, Affirmative Action, Gender Violence, and other terms that provide educators with a deeper understanding of the complexities of social gender issues and how to apply principles of equality and justice in educational settings.

Based on the results of a Likert scale survey, the distribution of opinions reveals significant diversity, with a tendency to acknowledge a lack of knowledge and awareness of terms related to gender issues. The largest group, comprising 28.5% of participants, indicated a opposing stance (Category3), followed by the strongly disagreeing category (Category1) at 24%, indicating a significant opposition totaling 63.2% to varying degrees. The majority of them are between 20 and 30 years old, and most of them have a bachelor’s degree level of education. On the other hand, a total of 36.6% of participants believe they are familiar with these terms (of which 15.3% strongly agree).

This indicates a significant lack of understanding of terms related to gender issues, highlighting the need to focus efforts on explaining these terms and enhancing awareness within teaching frameworks.

The reforms initiated by Morocco since the 1990s, which have addressed human rights and gender equality, including the reform of the Family Code in 2004, amendments to nationality laws, and the implementation of affirmative action measures in elections, among others, have been further strengthened by the introduction of new provisions and principles related to social gender equality in the new constitution of 2011. These paved the way for the enactment of further legislation in this direction, such as:

Law No. 79–14 issued on December 21, 2017, concerning the Authority for Parity and the Fight against All Forms of Discrimination, which granted this authority several powers, including the authority to autonomously express its opinion on draft laws or decrees, intervene in any issue at all stages of the legislative process, and propose recommendations aimed at enhancing the values of equality, parity, and non-discrimination, and ensuring their promotion and dissemination.

Law No. 103–13 related to combating violence against women, which entered into force in September 2018, aiming to provide legal protection for women victims of violence through four dimensions (prevention, protection, non-impunity, and comprehensive victim care).

If the study by Cardona Molto and Miralas (2022) demonstrated the importance of developing effective tools such as the TEGEP scale to assess teachers’ self-efficacy in gender-responsive education, and some of its findings revealed a lack of training and awareness regarding gender issues, this resonates with the findings of the current study that show limited understanding among participants of gender-related terms and laws.

The survey results indicate that more than half of the participants are not familiar with the gender equality legislation in Morocco. While 26% strongly deny their knowledge of these laws (Category 1), there is also a proportion (18.2%) strongly agreeing (Category 6) that they are aware of and familiar with these legislations. Therefore, the overall percentage of those denying their awareness of gender equality legislation, to varying degrees, reaches 56.2%, The majority of them are between 20 and 30 years old, and most of them have a bachelor’s degree level of education.

There may be a need for training and professional development for teachers, educators, and other specialists to ensure their full understanding of legislation related to gender equality and its effective implementation. Increasing awareness about the importance of these laws and their positive impact on society is also crucial. Additionally, further studies may be conducted to understand the reasons behind this lack of awareness.

Gender Equality refers to the state where access to rights or opportunities is unaffected by gender; in other words, everyone enjoys the same rights and opportunities regardless of whether they are male or female. The goal of Gender Equality is to achieve complete parity between genders in all social, political, and economic aspects of life.

On the other hand, Gender equity refers to the process of achieving justice between women and men according to their respective needs. This may include providing greater benefits and opportunities to the more vulnerable party (Affirmative Action).

The histogram illustrates the survey results regarding participants’ opinions on their knowledge and awareness of gender roles:

The results indicate that the majority of respondents (53.4%) do not distinguish, to varying degrees, between gender equality and gender equity (including 23.6% who strongly disagree). The majority of them are between 20 and 30 years old, and most of them have a bachelor’s degree level of education. In contrast, 46.7% of participants demonstrated their ability to understand the differences between the two terms with varying levels of confidence (including 18.2% who strongly agree).

This underscores the need for further education and discussion on the concepts of Gender Equality vs. Gender equity to bridge this knowledge gap.

Traditional gender roles have historically been prominent in Morocco, where men are often seen as the breadwinners and women as responsible for household duties. However, in recent years, there have been increasing efforts, particularly led by women’s movements, to challenge and redefine these roles. Reforms such as the Family Code reform in 2004, along with other legislative measures aimed at promoting gender equality, have contributed to changing some societal attitudes and practices despite societal resistance.

The majority of participants (55.8%) expressed varying degrees of inability to identify, describe, or distinguish gender roles (including 19% who strongly disagree). The majority of them are between 20 and 30 years old, and most of them have a bachelor’s degree level of education. In contrast, 44.2% of participants felt confident in their understanding of gender roles (including 19.8% who strongly agree).

The survey results highlight a significant gap in confidence levels regarding the understanding of gender roles. This polarization indicates the need for more comprehensive education and discussion on gender roles to bridge the knowledge gap and enhance more consistent understanding.

Applying equal opportunities to gender refers to the necessity of providing equal opportunities for everyone, regardless of gender, and implementing policies and practices that ensure justice and equality between genders in various aspects of life. This principle enables individuals to have equal opportunities for success and prosperity, utilize their full capabilities and skills, and contribute fully to economic growth without restrictions due to gender-based discrimination.

A significant majority of participants (69.9%) expressed their familiarity with the application of gender equality, with the largest category being “strongly agree” at 39.7%, indicating a high level of confidence among many participants. In contrast, 30.1% of participants expressed varying degrees of disagreement (including 10.3% who strongly disagree). However, this percentage indicates the need for continuous education and dialogue to ensure comprehensive understanding of this issue among all participants.

According to Smith (2020), “gender discrimination involves biased actions or attitudes toward individuals based on their gender, resulting in inequality in treatment across various societal sectors.” On this basis, it can be said that gender discrimination refers to unfair or preferential treatment of individuals based on their gender. It encompasses various contexts such as the workplace, education, healthcare, elections, and others.

It is noted that approximately (73.9%) of those who cannot define/describe/identify/know/distinguish “gender discrimination” to varying degrees (the largest category being 42.1% who cannot at all). This indicates that the vast majority of participants do not have sufficient awareness of the issue of gender discrimination. In contrast, there is a small portion of participants who are aware and knowledgeable about gender discrimination, to varying degrees, totaling about 26% (including 11.2% who strongly agree).

This result highlights the urgent need to increase awareness and education on the subject of gender discrimination to enhance comprehensive understanding among all members of the community.

Gender parity refers to the state of equal participation and representation of all genders in various aspects of society, such as employment, education, and political involvement. It is a measure of equality aimed at balanced distribution of opportunities and resources between genders. According to Jones (2019), “Achieving gender parity means ensuring equal opportunities and outcomes for all genders, often measured in terms of participation rates and representation.”

The data reveals a divergence in the extent to which participants in the survey “Measuring Professors’ Competence in Practicing Gender Equality Awareness” agree on their awareness of gender parity. While some individuals completely disagree (15.7%), others entirely agree (26.9%). In between, there is a group that somewhat disagrees (19.8%) or somewhat agrees (12.0%). The total percentage of those denying awareness of this issue to varying degrees reached 45.6%. It is crucial to consider this variation when developing policies and initiatives to enhance gender equality and raise awareness of its importance.

Gender bias refers to the inclination or prejudice in favor of or against one gender over the other, often rooted in societal stereotypes and norms. This bias can influence decision making processes and impact opportunities and individuals’ perceptions based on their gender. As expressed by Lee and Huang (2018), “Gender bias is the differential treatment of individuals based on their gender, often stemming from deep-seated societal stereotypes and cultural norms.”

According to the Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI) for 2023, gender bias is a pervasive issue worldwide. Without addressing biased social norms between genders, achieving gender equality or sustainable development goals may be challenging.

If the study by Mukagiahana et al. (2024) reported that more than 80% of teachers in Rwanda were able to improve their gender-responsive practices after training, but they faced challenges in addressing stereotypes and promoting gender-neutral communication. This is in line with the findings of the current study, where participants showed low awareness of gender biases and discrimination.

The responses reflect diverse perspectives on gender bias, with a significant portion expressing negative views. The data show variation in participants’ ability to identify, define, or recognize gender-based bias. There appears to be a high percentage of participants who do not believe they are aware of gender bias, with 79% (including 45.9% who strongly disagree). In contrast, the total percentage of those confirming varying degrees of awareness on this issue does not exceed 21.1%, with those strongly agreeing not surpassing 5.8%.

These results indicate the need to develop education and training programs aimed at increasing knowledge and awareness of gender bias, especially targeting those who demonstrated limited understanding in the survey.

The user distinguishes between the biological differences (sex) and the social roles, behaviors, and attributes (gender). While sex refers to biological characteristics such as chromosomes, hormonal profiles, and reproductive organs, gender relates to the roles, behaviors, and identities that societies attribute to individuals based on their perceived sex.

The responses to the statement “I can (define, describe, identify, distinguish, etc.) sex and gender reflect diverse perspectives.” A total of 68.3% of participants expressed some form of opposition regarding their ability to understand sex and gender, with 26.9% strongly disagreeing. This indicates a significant proportion of participants with negative perceptions or uncertainty regarding their understanding and distinction between Sex and Gender. In contrast, there is a very small percentage of those who strongly agree (9.5%).

These results highlight the need for targeted educational interventions aimed at enhancing participants’ understanding and awareness of sex and gender concepts, with particular emphasis on those who demonstrated opposition or uncertainty in the survey.

The term “gender inequality” is commonly used to refer to the disparities and challenges faced by women and men in our societies, indicating differences in opportunities, resources, and treatment based on their gender. These disparities can manifest in various areas, including wage gaps, employment opportunities, access to education, participation in public life, and political representation.

The responses of the participants regarding gender inequality reflect diverse viewpoints. A significant proportion, constituting 45.5%, strongly disagree with their ability to understand, define, or identify gender inequality. Additionally, 9.1% disagree, while 9.5% somewhat disagree. On the other hand, 16.5% strongly agree with their understanding of gender inequality, and 12% somewhat agree. Thus, the total percentage of respondents who oppose, to varying degrees, amounts to 78.1%.

These data indicate varying levels of awareness and recognition of gender inequality among the respondents, with a tendency toward opposition. This highlights a pressing need to enhance understanding and awareness of gender equality and work toward reducing negative perceptions or uncertainties related to this issue.

Gender stereotypes are widely accepted beliefs or assumptions about the characteristics, behaviors, and roles typically associated with men and women.

However, these stereotypes can be explicit, clear, and conscious, or implicit and unconscious. They often arise from societal norms, cultural traditions, and historical contexts. While these stereotypes are often deeply ingrained, they are not unchangeable. Promoting education and awareness about the harmful effects of gender stereotypes can encourage more equitable behavior and attitudes.

When participants were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with their ability to define, describe, identify, recognize, or differentiate gender stereotypes, 34.7% strongly disagreed, 15.7% disagreed to a lesser degree, and 18.2% somewhat disagreed. This means that a total of 64.1% expressed varying degrees of disagreement. On the other hand, 16.1% agreed, 10.3% somewhat agreed, and 5% strongly agreed.

These results demonstrate the variation in attitudes toward gender-related stereotypes, with a tendency toward opposition. This underscores the need to enhance awareness of gender stereotypes through the implementation of educational and training programs.

Implementing gender-responsive teaching methods can lead to graduating individuals who are more aware and contribute to developing a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of social diversity, which positively impacts the entire community. Applying these methods can also contribute to creating a better and more inclusive educational environment for all students.

The data derived from the survey provides a comprehensive overview of the opinions of student teachers and teachers regarding their ability to implement gender-responsive teaching methods. Each aspect was evaluated using a six-point Likert scale. The data reveals a range of perspectives, with participants being asked about their confidence in:

- Providing equal opportunities for all students,

- Planning teaching strategies from a gender perspective,

- Integrating gender considerations into course content and materials,

- Taking necessary actions to address or prevent perpetuation of inequality, − Respecting the different needs and learning styles of all genders,

- Creating learning environments that promote gender cooperation,

- Designing, implementing, and evaluating lesson plans from a gender perspective,

- Involving families in implementing gender equality plans at school and home,

- Collaborating with colleagues to implement gender equality plans,

- Educating about gender issues.

Ensuring that all students, regardless of gender, have equal access to educational resources and opportunities is a fundamental cornerstone for promoting justice, reducing disparities within educational environments, and positively impacting their academic and personal development. This aligns with the principles of inclusive education, which aim to provide all students, regardless of their backgrounds or characteristics, with fair and adequate educational opportunities (UNESCO, 2017).

Most respondents support providing equal opportunities to students, with a minority expressing neutral views. Notably, 63.2% strongly support, while 7.0% agree.

The high percentage of respondents strongly agreeing (63.2%) suggests a general commitment to equity in education. However, the presence of disagreement (2.9 to 12.4%) indicates potential areas of inequality or differing interpretations of what constitutes equal opportunity.

Designing teaching strategies that take into account gender differences helps teachers meet diverse learning needs and preferences of students to enhance engagement and improve learning outcomes. This is based on the understanding that students may respond differently.

To various teaching methods based on their gender identities. This approach supports the principles of differentiated instruction, which emphasize designing teaching methods to meet individual students’ needs (Tomlinson, 2001).

There are diverse perspectives regarding planning strategies from a gender perspective, with many expressing neutral or positive positions. About 28.1% strongly endorse it, while 31% endorse it moderately (somewhere between agree and agree to some extent). The disparity between those who strongly agree (28.1%) and those who strongly oppose (17.4%) underscores varying levels of awareness and understanding regarding teaching methods that consider gender disparities, with a total of 45% opposing to varying degrees. This gap may be attributed to inadequate training, lack of institutional support, or entrenched biases. Addressing these obstacles requires targeted professional development and policy initiatives.

Integrating gender considerations into the content and materials of a course enhances a more inclusive educational environment that provides students with diverse and mutually respectful learning interactions. It enables them to gain deeper and more comprehensive understanding of gender roles in society and the cultural and social impacts associated with them. This approach supports the goals of multicultural education, which advocates for integrating diverse cultural perspectives into educational practices to promote understanding and respect for differences (Banks, 2015).

The responses indicate diverse perceptions regarding the mainstreaming of gender perspective in course content, with many expressing neutral and positive attitudes. A total of 51.4% are in favor to varying degrees, including those who strongly support it (21.1%), while 16.5% express strong opposition.

The mixed responses reveal a complex landscape where some embrace the mainstreaming of gender perspective, while others express resistance or uncertainty. This highlights the need for comprehensive strategies to reconsider the gender perspective in curricula, including curriculum design, resource development, and educational practices.

Proactive addressing of gender-related inequalities within educational institutions helps create an environment where all students feel valued and respected. This includes policies and interventions aimed at addressing or preventing discriminatory practices, biases, and barriers that hinder equitable educational opportunities. This aligns with the principles of educational justice, which seek to eliminate disparities based on factors such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, and disability (Ladson-Billings, 2006).

Approximately 44.6% of participants support taking action against the proliferation of inequality, with a minority expressing neutral opinions. Around 20.7% strongly endorse this, while the total opposing to varying degrees reached 55.3% (including 26.4% strongly opposed). This disparity may reflect different perceptions of the root causes of inequality or varying levels of commitment to change.

Recognizing and respecting the diverse learning needs and styles of students based on their sexual identities enhances a supportive and inclusive educational environment. This ensures that teaching methods are responsive and adaptable to individual differences, thereby promoting student engagement, motivation, and academic success. This approach is supported by research on differentiated and inclusive education, emphasizing the importance of adjusting teaching strategies to meet students’ individual needs (Tomlinson, 2001; UNESCO, 2017).

Views on respecting different learning styles vary. The total supporters, reaching 76% (including 47.5% strongly in favor), indicate overwhelming support for respecting diverse learning needs (47.5%) and recognizing the importance of inclusivity in education. However, the presence of a 24% opposition (including 8.7% strongly opposed) underscores the complexity of accommodating diverse learning styles and needs, including those related to gender. Educators may benefit from training in comprehensive teaching methods and culturally responsive practices to better support all learners.

Creating inclusive educational environments that enhance collaboration and interaction among students of different genders leads to improving their social skills, abilities in teamwork, and understanding of diverse perspectives. This contributes to building a cooperative and respectful community within schools. Moreover, it supports social and emotional development and enhances the dynamics of inclusive classrooms. As noted by Johnson and Johnson (2009), cooperative learning strategies are effective in promoting positive relationships and improving academic achievement among diverse student groups. Through learning from each other and collaborating on tasks, students enhance their problem-solving skills, develop their abilities to work collectively, and deepen their understanding and respect for diverse viewpoints.

The data indicates clear support for establishing cooperative learning environments, with a total of 76.8% expressing varying degrees of support (including 52.5% strongly in favor), while a minority express neutral viewpoints. Opposition stands at 23.2% (of which 9.9% strongly oppose).

The presence of this opposing faction, despite its small size, may indicate potential barriers to promoting cooperation between genders. This could stem from entrenched gender norms, cultural backgrounds, or limited awareness of strategies to promote inclusive interactions. Developing cooperative learning communities requires deliberate efforts to understand and address cultural clashes.

Integrating a gender perspective into lesson planning helps teachers address gender related issues and promote gender equality. It ensures that educational content is relevant, meaningful, and reflective of diverse experiences and identities, leading to a more comprehensive understanding among students of the complexities of gender issues, and fostering empathy and respect. Additionally, it prepares students to navigate and contribute positively to a diverse and inclusive society. This approach supports efforts to challenge stereotypes and biases, creating a more inclusive and respectful educational environment (UNESCO, 2019).

Viewpoints on integrating a gender perspective into lesson plans vary, with many expressing neutral or positive positions. However, the majority (approximately 55.4%) are confident in designing, implementing, and evaluating lesson plans from a gender perspective (including 21.5% who strongly endorse it), while 19.8% strongly oppose it.

These mixed responses shed light on the challenges facing the integration of gender perspectives into educational practices. While some teachers show commitment, others express doubt or resistance. This underscores the need for targeted support, including guidance, resource development, and opportunities for continuous professional learning focused on implementing gender-responsive teaching strategies.

Researchers in the field of school-family-community partnerships have long emphasized the importance of parental involvement in enhancing students’ academic success and well-being, such as Epstein (2011). Similarly, involving families in discussions and activities related to gender equality helps foster a shared understanding of gender issues and ensures coordinated efforts and cooperation to promote values of respect, equity, and inclusivity both at school and at home. This contributes to creating a supportive network for the holistic development of students and provides an environment that upholds these values beyond the school walls.

The responses indicate diverse perspectives on engaging families in gender equality plans, with more than two-thirds of participants (approximately 69.4%) expressing varying degrees of support (including 35.1% strongly in favor), while 30.6% express varying degrees of opposition (including 12.4% strongly opposed).

These data reflect varying levels of agreement and disagreement regarding the role of families in promoting gender equality. While many recognize the importance of family involvement, others may face obstacles such as cultural norms, communication challenges, or limited community participation. Strengthening partnerships between schools and families requires culturally sensitive approaches, effective communication strategies that take into account the roles of parent associations, and collaborative initiatives to achieve shared goals.

Collaborative efforts among teachers and their colleagues in school are essential for exchanging best practices, resources, and ideas to promote continuous learning, development, and the cultivation of a school culture that values diversity and inclusivity. This leads to a more cohesive and unified approach in addressing social gender issues within the educational system. This is underscored by Hargreaves and Fullan (2012), recognizing that investing in teachers’ professional capital is the optimal way to sustainably improve the quality of education. In other words, through enhancing collaboration, leadership, and continuous support, schools and educational systems can develop effective and inclusive learning environments.

Viewpoints on collaborating with colleagues in implementing gender equality plans vary, with many expressing neutral or positive positions. The total supporters, with varying degrees, reached 70.3% (with approximately 36.4% strongly in favor), while the total opposers, with varying degrees, reached 29.7% (of which 13.2% strongly oppose). The contradiction between those strongly agreeing and strongly disagreeing emphasizes the complexity of collaborative efforts aimed at promoting gender equality. While some teachers embrace teamwork, others may face resistance or disagreement from colleagues. Overcoming barriers to collaboration requires fostering a culture of inclusivity and building trust.

Education on gender issues can help individuals reduce harmful social phenomena such as discrimination and bias to build a more just, tolerant, and respectful society. This is achieved through understanding the complexities of gender diversity, effectively challenging stereotypes and misconceptions, and encouraging empathy and compassion. Accordingly, UNESCO (2019) emphasizes the importance of gender-responsive education in promoting equality and combating discrimination. It calls for educational practices that integrate a gender perspective to create supportive and inclusive learning environments.

Most participants support education on gender issues, with a total of 68.2% expressing varying degrees of support, while a minority express neutral opinions. It is noteworthy that 40.5% strongly support it. The opposition amounted to a total of 31.8% (including 10.7% strongly opposed). The broad support for gender education reflects the growing recognition of the importance of addressing gender-related issues in educational contexts. However, the presence of opposing views indicates potential challenges in dealing with sensitive topics or addressing resistance to change.

Teachers can play a vital role in developing gender-related behaviors and promoting gender equality through several practices and strategies. This includes conveying/instilling attitudes that consider gender differences, dismantling gender stereotypes and biases, confronting normalization of gender discrimination and violence, advocating against all forms of gender injustice, and supporting school-community partnerships to enhance gender equality.

The data from the survey provides a comprehensive overview of participants’ opinions regarding their readiness to develop gender-related behaviors. These five elements mentioned above were evaluated using a Likert scale.

Teachers can convey and instill attitudes that consider gender differences by adopting a set of strategies and practices aimed at promoting awareness of gender equality. This includes preparing educational materials that address social gender issues, promoting values of respect and cooperation among students through collective activities and joint projects, and other strategies that integrate these concepts into the educational environment.

The responses indicate that the majority of respondents are willing to convey/instill attitudes that consider gender differences, with a minority expressing neutral or opposing views. Approximately 26.0% strongly support this, while a total of 37.2% of respondents expressed some level of disagreement (including 14.5% strongly opposing).

The levels of opposition suggest that a significant portion of respondents may face challenges or lack confidence in promoting gender considerations in the educational context. This could be due to underlying biases, insufficient training, inadequate support systems, or other reasons.

Dismantling gender stereotypes and biases is a crucial part of efforts to promote gender equality in educational environments and societies in general. Teachers can play a pivotal role in developing behaviors related to gender through employing various strategies to reduce gender biases that may negatively impact the experiences of male and female students.

Views on dismantling gender stereotypes and biases vary, with many expressing neutral and positive stances. Approximately 36.0% strongly support this effort, indicating a significant segment willing to combat gender stereotypes and biases. However, the fact that 29.3% of participants expressed varying degrees of reluctance (including 10.3% strongly opposed) suggests challenges in effectively dismantling gender stereotypes and biases through public school teachers in Morocco. There may be a need for focused efforts to provide targeted training and resources that empower teachers to address and effectively dismantle these stereotypes.

Confronting the normalization of gender discrimination and violence represents a significant challenge that requires integrated and coordinated efforts from teachers and the educational community as a whole to ensure safe and inclusive learning environments for all students. This can be achieved by promoting a culture of gender equality and respect in classroom practices and school activities, and by changing attitudes and behaviors that consider gender discrimination and violence as natural or acceptable.

The data indicates support for confronting tolerance of gender discrimination and violence, with a minority expressing neutral views. Approximately 39.7% strongly support this, while 13.2% strongly oppose it. However, it is noteworthy that a total of 29.7% of participants are unwilling, to varying degrees, to confront the normalization of gender discrimination and violence, reflecting significant resistance or challenges in addressing this issue. This highlights the need for targeted interventions to raise awareness in this direction.

Advocating against all forms of gender injustice can involve multiple and integrated efforts to address discrimination, violence, and inequity individuals face based on their gender. These efforts include several strategies that educators and the educational community can adopt to promote gender equality and rights, such as:

Providing educational and awareness programs that highlight forms of gender injustice like sexual, economic, and social discrimination and violence.

Organizing media campaigns and seminars to enhance students’ and parents’ understanding of the importance of combating all forms of gender injustice.

Hosting cultural and social events that enhance understanding and interaction among students regarding gender rights and equality.

The responses indicate diverse perceptions regarding advocacy against gender injustice, with many expressing neutral or positive attitudes. Approximately 75.6% showed varying degrees of readiness (including 53.7% strongly supporting) to advocate against gender injustice, while 12.8% expressed strong opposition.

A significant portion of participants may be hesitant or unsure about their readiness to advocate against gender injustice. About 24.4% of participants who expressed disagreement, to varying degrees, indicate a segment not ready to contribute to advocacy against all forms of gender injustice. This suggests potential gaps in awareness or conviction about the importance of addressing this issue.

This highlights the need for training in this field and possibly creating a more supportive environment to encourage active participation in promoting gender justice.

Supporting links between schools and the community is a fundamental part of efforts to promote gender equality, as this support contributes to encouraging and enhancing continuous and open communication between schools and members of the local community, including parents, local associations, and non-governmental organizations. Teachers can play a pivotal role in this direction by strengthening ties with local communities and building effective partnerships that support these critical issues.

Opinions vary regarding support for links between schools and the community to promote gender equality, with many expressing neutral or positive views. Approximately 75.5% of respondents indicated varying degrees of support (with around 47.1% strongly supporting this). However, there is a significant minority that may face challenges or lack the necessary resources and support to effectively participate in these efforts.

With 24.3% of participants expressing varying degrees of disagreement (including 9.5% strongly opposing), support for links between schools and the community to promote gender equality faces notable challenges. Building stronger community ties and providing clear guidance and resources may help address this gap.

This study faced challenges in achieving optimal participant representation due to a lower-than-anticipated response rate, even though the survey was distributed widely. While some educational professionals expressed trust in the researchers and willingly participated, others hesitated or outright declined, often citing concerns about the sensitivity of gender issues and perceived ambiguities in the questionnaire. Clarifications were provided to participants who sought better understanding of the survey questions, which facilitated more informed engagement.

A particularly detailed critique from one non-participant highlighted resistance to addressing gender-related topics, associating them with broader societal shifts and potential risks to cultural values. The respondent stated: “… I carefully reviewed the form, then conducted a thorough search on the topic (gender) and understood its dimensions and the origin of raising such issues, especially at a time when our society is undergoing radical shifts in values and traditions. … I do not agree with dealing with the topic in any way. Even the nature of presenting the questions in the form is ambiguous, and frankly, this is not just my opinion but the opinion of everyone who was offered the form and found its questions unclear and ambiguous, so they refused. Therefore, based on my good knowledge of this type of – tendentious – forms, I refuse to fill it out so as not to participate in a corrupt decision that may be made in the future regarding the fate of a nation in any field, whether educational or otherwise …”

One of the participants, who faced challenges in completing the questionnaire, mentioned: “Some of the phrases translated into Arabic made it difficult for me to understand certain aspects of the questionnaire, which delayed my responses. However, the clarifications you provided have now resolved that confusion.”

Such variations in responses underscore the complexity of addressing gender-related topics within the Moroccan educational context. While the openness of some participants highlights the potential for constructive dialogue, resistance from others reflects broader societal apprehensions about engaging with gender-sensitive topics.

These findings emphasize the importance of designing research tools that are both culturally sensitive and clearly communicated to mitigate ambiguity and foster broader acceptance. Future studies should strive for more inclusive representation by targeting diverse demographic groups, including rural and urban educators, and employing methods such as ethnographic research to uncover deeper cultural dynamics shaping gender perspectives.

By addressing these barriers and building on the trust demonstrated by some participants, future research can provide robust evidence to inform effective policies and training programs, ultimately contributing to Morocco’s efforts toward gender equality and sustainable educational development.

The results obtained from participants’ assessment of their self-efficacy in practicing gender equality in the Moroccan educational context can be said to show a great diversity of opinions. This diversity relates to levels of knowledge and awareness of gender, readiness to apply gender-responsive teaching methods, and readiness to develop gender-related behaviors. Some expressed varying degrees of support, while others expressed varying degrees of opposition. While the prevailing trend in participants’ opinions is toward achieving positive percentages, the presence of varying levels of opposition, some of which are more rigorous, albeit at a lower rate compared to the pro-categories, indicates challenges in practicing gender equality in Morocco. The results also highlight the importance of demographic variables in shaping individuals’ views on gender-related issues. Age and educational level were found to significantly influence progressive views on gender equality, while gender identity and employment status also played a role in shaping views on gender equality. These results contribute to our understanding of how demographic factors intersect with views on gender and provide insight into the complex nature of gender perspectives in different contexts. Future research may further explore these relationships by considering additional variables such as cultural influences and institutional contexts, which may provide further insight into the factors that influence attitudes toward gender roles and equality.

All of this underscores the need for more comprehensive strategies for basic and ongoing training for faculty to effectively address gender issues, especially as the findings revealed a significant lack of understanding of gender-related terminology and legislation, which requires further research to understand the reasons behind this lack and to propose training programs that aim at least to explain these terms and legislation and enhance faculty awareness of their importance.

Furthermore, the insights gained from this assessment could benefit policymakers, educators, and organizations seeking to promote gender equality, effectively address gender-based discrimination and bias, and create more inclusive, empowering, and equitable learning environments.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

HR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. KT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Generative AI (ChatGPT, GPT-4, OpenAI) was used to assist in creating the stacked bar charts. The final content was reviewed and edited by the authors to ensure accuracy and quality.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1483905/full#supplementary-material

Banks, J. A. (2015). Multicultural education: issues and perspectives. 9th Edn. Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S: John Wiley & Sons.

Cardona, C. M., Kitta, I., and Miralles-Cardona, C. (2023). Exploring pre-service STEM teachers' capacity to teach using a gender-responsive approach. Sustain. For. 15:11127. doi: 10.3390/su151411127

Cardona-Moltó, M. C., and Miralles-Cardona, C. (2022). Education for gender equality in teacher preparation: Gender mainstreaming policy and practice in Spanish higher education. In J. Boivin and H. Pacheco-Guffrey (Eds.), Education as the driving force of equity for the marginalized (pp. 65–89). IGI Global.

Chan, R. C. H. (2022). A social cognitive perspective on gender disparities in self-efficacy, interest, and aspirations in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM): the influence of cultural and gender norms. International Journal of STEM Education 9. doi: 10.1186/s40594-022-00352-0

Chiner, E., Kitta, I., Miralles-Cardona, C., and Cardona Moltó, M. C. (2021). Exploring pre-service STEM teachers’ capacity to teach using a gender-responsive approach: case study in Spain and Greece. Sustain. For. 13, 1–16.

Epstein, J. L. (2011). School, family, and community partnerships: preparing educators and improving schools. 2nd Edn. New York: Westview Press.

Global Education Monitoring Report Team. (2024). Global education monitoring report, 2024/5: Leadership in education: Lead for learning. UNESCO. doi: 10.54676/EFLH5184

Global Partnership for Education (2023). Evidence for system transformation: teachers and teaching for gender equality. Available online at: https://globalpartnership.org

Hargreaves, A., and Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: transforming teaching in every school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ioanna, K., and Cardona-Moltó, M. C. (2022). Student perceptions using the training evaluation gauge for gender equality. J. Gend. Stud. 31, 457–477.

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ. Res. 38, 365–379. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09339057

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools. Educational Researcher, 35, 3–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189x035007003

Lee, M., and Huang, L. (2018). Gender Bias, Social Impact Framing, and Evaluation of Entrepreneurial Ventures. Organization Science, 29, 1–16.

Miralles-Cardona, C., Kitta, I., Cardona Moltó, M. C., Gómez-Puerta, M., and Chiner, E. (2021). STEM students' perceptions of self-efficacy for a gender equality practice: a cross-cultural study. Sustain. For. 13, 1–18.

Moroccan Official Gazette No. 4866 (2000). International convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW).

Moroccan Official Gazette No. 5964 bis (2011). The constitution of the Kingdom of Morocco. The Official Printing House, General Secretariat of the Government.

Mukagiahana, J., Sibomana, A., and Ndiritu, J. (2024). Gender-responsive pedagogy in Rwanda: challenges and successes. J. Pedagogical Res. 8, 280–293. doi: 10.33902/JPR.202423067

Pedrajas, R. P., and Jalandoni, N. D. (2023). Promoting gender equality in the classroom: teachers’ challenges and strategies. J. Educ. Teach. Train. 14, 390–398.

Smith, J. (2020). The effects of gender discrimination on career progression. Workplace Equality Rev. 10, 51–70.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. 2nd Edn. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

UNESCO (2016). Promoting gender equality in education: a case study of Morocco. UNESCO Education Reports. Available online at https://unesco.org/reports/morocco-gender-equality

UNESCO (2019). A guide for gender-responsive teacher education. UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/

Keywords: gender-responsive education, gender, gender awareness, gender equality, fairness, equal opportunities, gender discrimination, gender stereotypes

Citation: Rguibi H, Tijania K and Taleme N (2025) Assessing teacher competence in gender equality in the Moroccan educational context. Front. Educ. 10:1483905. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1483905

Received: 20 August 2024; Accepted: 27 February 2025;

Published: 08 April 2025.

Edited by:

Tanya Pinkerton, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jesus Marolla-Gajardo, Santo Tomás University, ChileCopyright © 2025 Rguibi, Tijania and Taleme. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hafid Rguibi, aGFmaWR2b2RhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Hafid Rguibi, orcid.org/0009-0006-9160-3828

Khalid Tijania, orcid.org/0009-0002-9433

Naoual Talem, orcid.org/0009-0009-1695-4582

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.