- 1Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2Australian Council for Educational Research, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Student mental health is linked to improved learning, and there has been significant international investment in policies, practices, and programs focused on preventing and responding to mental health conditions amongst young people. Accordingly, the number of mental health and wellbeing interventions now being implemented in education settings continues to grow, despite a lack of research on teacher readiness to implement such interventions. Numerous studies have associated educator stress and burnout with increased workloads, yet the complexity of student needs, coupled with an ongoing lack of support, continue to result in high rates of educator attrition. This paper presents the findings of a recent mixed methods study of educators from schools and universities in Australia. The research approach included three key activities: (i) a systematic document review and synthesis of literature and policy documents, (ii) a validated “teacher worry” questionnaire that explores reasons for worry amongst educators, and (iii) qualitative interviews with key stakeholders, including educational psychologists, teachers, and preservice education coordinators. Correlation analysis suggests a relationship between individual sources of worry and intention to leave the profession, while thematic analysis offers insights into the experiences of educators, and their need for better support. Overall, the findings suggest that although teachers are already heavily burdened by their workload, they are increasingly subject to elevated expectations of dealing with diverse students’ needs and behaviors. The research also indicates that educators’ stress and poor mental health reduces their motivation to help students to reach academic goals.

Introduction

Although schools and education settings are traditionally seen as places where young people acquire academic skills, they are also increasingly recognized as providing students with crucial opportunities to nurture mental health and wellbeing (OECD, 2017; Biglan et al., 2012; Bücker et al., 2018; Brown, 2018; Mahoney et al., 2020). Research has also established a link between positive mental health and improved academic outcomes (Dix et al., 2020). Although supporting the mental health of young people was already a concern in educational settings, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to renewed focus on ways to better support the evolving needs of students within the education sector. In many contexts, student mental health is now a greater area of focus than academic achievement (Ahmed et al., 2023). At the same time, educators are facing increasing demands that impact on their own health and wellbeing.

Educator wellbeing is now a growing concern internationally. In 2018, the TALIS survey of 260,000 teachers and 15,000 school leaders across 48 countries reported that 18% of teachers experience ongoing and acute stress related to their work (Jerrim and Sims, 2020). Similarly, in a recent survey of almost 40,000 teachers conducted by the Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL, 2023), more than 30% of the respondents reported their intention to exit the profession, citing increased workload as the main factor. One of the major workload stressors reported by Australian educators is the ongoing challenge of addressing student mental health needs. This targeted review examines current evidence linking the enablers and challenges to educator mental health and wellbeing, and the links to their role perceptions and readiness to support student mental health in across early childhood, primary, secondary and tertiary settings.

Educator stress, anxiety, and mental health

More recently, there has been a growing body of research establishing links between the occupational stresses teachers face and their willingness to remain in the profession. Teaching is considered one of the most stressful professions in which to work (Agyapong et al., 2020; Kyriacou, 2001), with varied demands which often involve additional work hours beyond formal educational settings. According to Maslach et al. (2001) and Ventura et al. (2015), stress occurs when a person perceived an external demand as exceeding their capability to deal with it, and burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job. Such stress can impact on the self-efficacy of teachers, reducing their capacity to perform their roles and to support the students they care for.

The teaching profession, including K-12 education settings and university, is an occupation with high rates of stress and burnout, and one with elevated risk of poor mental health due to a high degree of responsibility, as well as unpredictability when dealing with students in the classroom (Geving, 2007; Grayson and Alvarez, 2008; McCarthy et al., 2016). There is also research linking negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, emotional stress, frustration, or depression to professional experiences and challenges (Kyriacou, 2001). In a 2023 study of educators (Black Dog Institute, 2023), 52% of school educators reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression (compared to 12.1% of the general population), while 46.2% of educators reported anxiety (compared to 9% of the general population). For educators, poor mental health and stress have the potential to cause emotional exhaustion, cynical attitudes about teaching, and lower job satisfaction (Capone and Petrillo, 2020; Dabrowski, 2020; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2011) and poses a risk to individual and collective wellbeing in education settings. It also decreases the potential value of the teaching profession, thereby hampering efforts and policies that seek to recruit and retain education professionals.

Literature emphasizes the importance of helping teachers to increase their job satisfaction, mental wellbeing and to reduce depression and burnout (Hamama et al., 2013; Lloyd et al., 2009) and to improve work performance (Schaufeli et al., 2009). Current research on the teaching profession shows that levels of work-related stress in teachers are high, often with detrimental impacts on their mental health and wellbeing (Ekornes, 2017; Gray et al., 2017; Schonfeld et al., 2017). Evidence has shown that factors such as stress, burnout, diversity of student needs in the face of a lack of structural support and the multiplicity of roles that teachers play in classrooms and beyond, contribute to poorer levels of teacher mental health and higher levels of teacher attrition (Farmer, 2020; Madigan and Kim, 2021).

The need for educators at all levels to meet system, student and care-giver expectations; manage classroom behaviors (e.g., negative and challenging student behaviors), diversify and adapt curriculum and content delivery to contribute to student learning while navigating a high workload, have been reported to cause increased levels of stress, lower job satisfaction and increased tendencies to leave the profession (Beltman et al., 2011; Fives et al., 2007; Gray and Taie, 2015; Kyriacou, 2001; Hakanen et al., 2006). Other factors that have been reported to influence educator stress levels include school climate, leadership support, as well as socio-economic pressures. Research findings have also shown that problematic student behaviors and high workloads were perceived as the most stressful in impacting educator mental health (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Kyriacou, 2001; Harmsen et al., 2019).

Linking educator and student mental health and wellbeing

Research evidence suggests a link between the mental health of educators and their students in their learning journeys from early childhood to tertiary settings. Across settings, educators who are found to be less stressed and anxious are more likely to be able to foster positive teacher-student relationships and support children and young people to be mentally healthy (Kidger et al., 2012; Plenty et al., 2014). These relationships enhance connectedness and bring a sense of belonging to schools and communities and are reported to improve student wellbeing as they move through the education system (Aldridge and McChesney, 2018). Conversely, educators who were found to be more anxious and stressed perceived themselves to be less able to support the mental health and wellbeing of their students (Gray et al., 2017; Jamal et al., 2013; Madigan and Kim, 2021; Sisask et al., 2014), and reported more difficulties in forming, or maintaining positive relationships with their students (Brock and Grady, 2000; Kidger et al., 2012; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). Researchers have also established that poor educator wellbeing has the potential to negatively impact student wellbeing, academically and behaviorally (Harding et al., 2019; Kipps-Vaughan, 2013). This stems from the inability to exercise and implement effective classroom management strategies or practices to support or facilitate student learning (Harding et al., 2019; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009).

Similarly, several research studies have also explored educator perceptions about supporting student mental health. Ekornes (2017) found that stress in educators is primarily driven by a mismatch between perceived level of responsibility and being able to help students with mental health problems. Another study has found educators’ own level of stress and worry is influenced by the socio-economic context of their learning community, particularly for educators in schools with lower socio-economic advantage, who reported experiencing elevated levels of overall worry (Van Der Zant and Dix, 2023). The demanding workload may also be a cause of increased educator worry (Farewell et al., 2022).

Qualitative studies conducted by Rothì et al. (2008) and Phillippo and Kelly (2014) found that educators’ level of preparedness to support student mental health is influenced by their knowledge and participation in professional learning about mental health. Similarly, a quantitative survey of teachers and school leaders in Norway found that while educators feel that it is their responsibility to support student mental health, they did not feel competent to do so (Holen and Waagene, 2014 as cited in Ekornes, 2017). Time constraints were attributed as a main challenge to educator readiness and engagement in interventions to support student mental health (Kidger et al., 2012; Koller and Bertel, 2006). Additionally, educators have also reported that the lack of school and structural support contravene their efforts to meet and manage student mental health needs (Finney, 2006; Hoy and Woolfolk, 1993; Weist and Paternite, 2006).

Although the tertiary context is not as well explored, educators in tertiary settings have reported that they increasingly perceive their role to include the detection of mental health conditions, and to connect their students with the support that could help them (Kamarunzaman et al., 2020; Gajaria et al., 2020). This is because while tertiary students have better understanding of mental health and wellbeing compared to students in high school, yet this does not translate to sufficient help seeking behaviors (Ibrahim et al., 2019). Tertiary educators therefore, are expected to become the optimistic, empathetic collaborators in championing mental health support (Kamarunzaman et al., 2020; Gajaria et al., 2020; Sommer et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2017).

Challenges supporting student needs

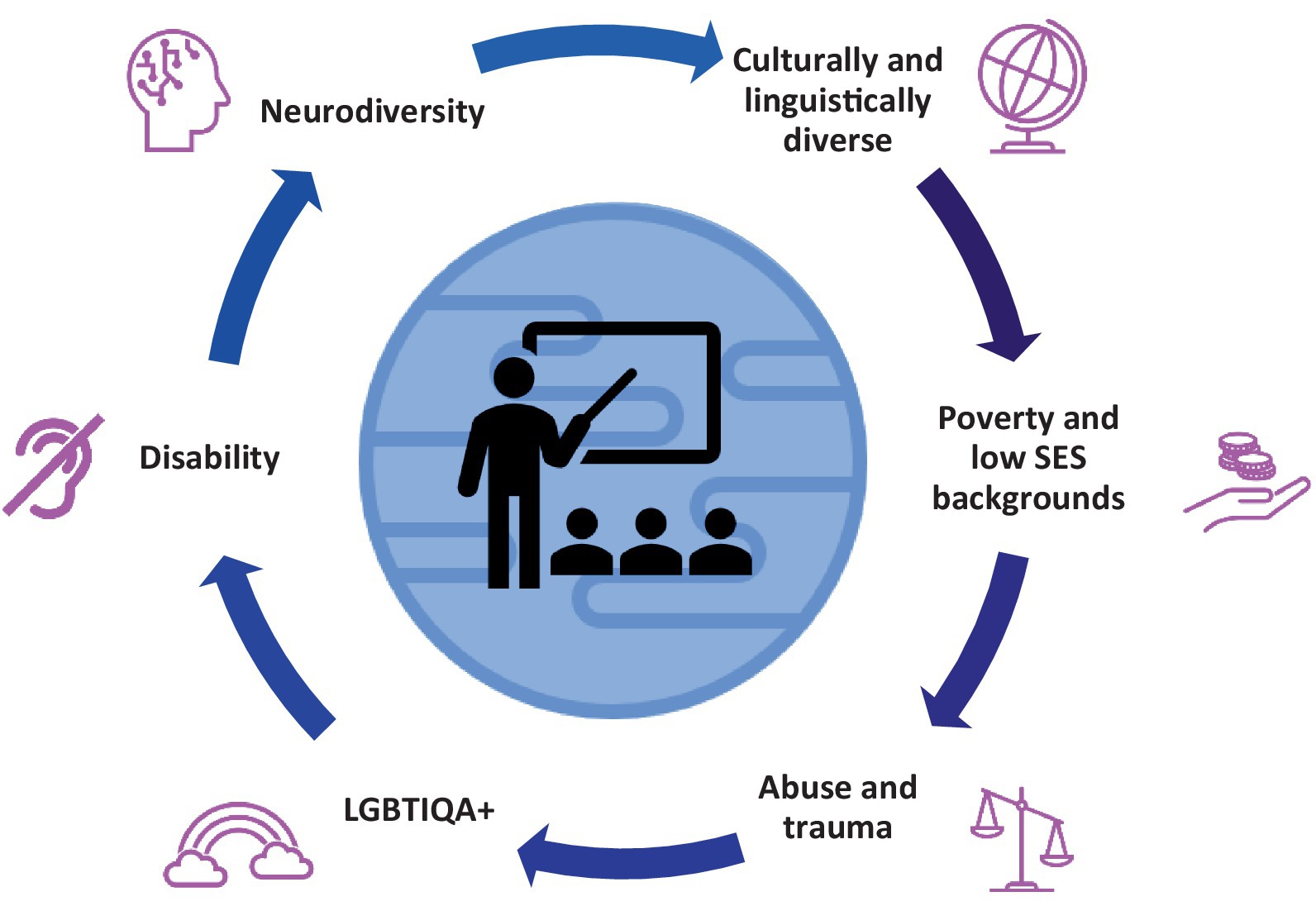

Studies conducted in Australia (Dabrowski et al., 2022; Laurens et al., 2022; Dix et al., 2020) suggest that despite rapid acceleration in school-based mental health programs, integration of mental health interventions into daily teaching and learning practice remains elusive. This lack of integration adds to teacher workload and burnout and fostering perception that student mental health is distinct from learning, instead of acknowledging that positive mental health can improve student engagement and achievement (Dix et al., 2012). In addition, student needs are evolving and changing. As awareness, discourse, and incidence of diagnosis grows around mental health in the general population, it is important to acknowledge that vulnerable and marginalized children are also far more likely to develop mental health conditions (Erskine et al., 2023; UNICEF and UNESCO, 2021; United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, 2021; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2020). These include children, adolescents, and young people with disabilities, those of LGBTIQA+ orientation, those who are homeless or exposed to violence, trauma, conflict, or displacement, and those with a family history of mental health concerns are at greatest risk (Silove et al., 2017), as highlighted below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diverse learning challenges in the classroom (Adapted from: UNESCO, 2024, p. 2).

The complexity of responding to the challenges facing educators across early childhood through to tertiary settings have been discussed in research. Educators in the early childhood sector note that managing young children’s difficult behaviors, workplace stress (such as, high child-teacher ratios, lack of career advancement opportunities), and other systemic challenges, (including poor pay and high workload), can lead to higher levels of burnout and turnover (Hindman and Bustamante, 2019; Jeon et al., 2019; Farewell et al., 2022; Souto-Manning and Melvin, 2022; Stein et al., 2024). Preschool educators reported experiencing elevated levels of overall worry (Van Der Zant and Dix, 2023), which can be due to demanding workload given the high attrition rates amongst early childhood educators (Farewell et al., 2022).

At a primary and secondary school level, research has shown that the increase in educator stress levels is partly due to the disconnect between educator capacity, and the growing expectation of inclusive practice, particularly for marginalized student groups (Gray et al., 2017). The demands and influences of parents upon teacher workloads and wellbeing have also been highlighted in existing literature (Magalong and Torreon, 2021). Some research has also shown that educators are often the first to identify that their students need help and further support in their learning (Dutton and Sotardi, 2023; Kratt, 2018), which further indicates a need to support both pre-service and in-service teachers in their capacity to properly meet student needs (Armstrong et al., 2015; Maclean and Law, 2022; Shelemy et al., 2019).

At tertiary levels, increasing work and productivity demands brought by the marketisation, massification, and technologization of higher education have been associated with increasing work-related stress, work related exhaustion, and mental health difficulties (Fontinha et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2019). Research has also shown that academic staff are increasingly required to support students with mental health difficulties (Gulliver et al., 2018; Margrove et al., 2014) amidst the ongoing challenges of teaching and interacting with diverse student populations (Dutton and Sotardi, 2023). Prior research has also suggested that educators at higher-educational institutions need training, coaching, and mentoring around understanding mental health issues and knowing what to do when they encounter students who need support (Kamarunzaman et al., 2020; Morton and Berardi, 2018). Additionally, it has also been suggested that forming networks of optimistic, empathetic educators and collaborators including the adult students with lived experience, can contribute to changing attitudes and improve the system (Kamarunzaman et al., 2020; Gajaria et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2017; Sommer et al., 2018).

It is clear from the review of literature that educators are facing stressors across the profession. In recognition of the need to better understand and support the challenges facing educators, and in the context of increasing reforms around inclusivity and growing expectations that educators are adept and able to support student mental health through school and tertiary settings, there is a need to explore the readiness of educators to support student mental health.

Materials and methods

Against a backdrop of teacher shortages and rising student mental health challenges, the purpose of this study was to understand and add to the evidence base of educator readiness and their needs for supporting students’ wellbeing and implementing mental health initiatives in their educational settings. Utilizing a mixed-method approach, this project aims to understand educator readiness to support student mental health across a range of education settings. Three research questions guide the focus of the study.

1. How does educator anxiety and worry impact on their ability to support student mental health?

2. To what extent are educators ready (and willing) to support student mental health in education settings?

3. What are the enabling conditions that support educator readiness?

The study focused on educators and relevant support staff working with children, adolescents, and adults in formal learning settings, including early learning, primary, secondary school, and tertiary education. In addition, relevant experts such as mental health care workers, youth wellbeing support staff, counselors/ psychologists, and other professionals involved in education settings were also invited to take part in the study. Utilizing an evidence-based mixed-methods approach, data for this study was collected and analysed in four phases, which are outlined below:

Framing educator attitudes and perceptions of supporting student mental health

Attitudes predispose a mindset that affects how a person responds to ideas situations, actions, ideas or people in a positive or negative manner (Oskamp and Schultz, 2005; Eagly, 1993). Attitudes have been theorized by Oskamp and Schultz (2005) to have three highly interrelated components, comprised of the affective, cognitive and the behavioral, where the affective component refers to the emotions held, the cognitive aspect refers to ideas and beliefs, and the behavioral component governs actions. These attitudinal components have also been evidenced to be widely used in education research in areas such as teaching practice, teacher beliefs, and student outcomes. In this study, attitudinal theory is used in this study as a lens for examining educator perceptions and attitudes toward supporting student mental health.

Phase 1: rapid review of academic literature, building on previous research

The first stage of the research was a rapid review of academic literature, focused on understanding current challenges around the mental health of students in education settings, and the growing demands now facing educators in response. Database searches, including EBSCO, Google Scholar and A+ Education using keywords and search terms associated with educator capacity to support student mental health were used through application of Boolean search strings in combination with snowball methods:

• “mental health school”

• “educator” OR “teacher” AND/OR “wellbeing”

• “mental health interventions” AND “school” OR “tertiary” OR “university”

• “educator” OR “teacher” AND/OR “burnout” AND/OR “stress”

• “educator” OR “teacher” AND/OR “self-efficacy”

• “educator” OR “teacher” AND/OR “attrition”

• “mental health” AND “tertiary settings” AND/OR “university”

• “mental health” AND “university lecturers”

• “student mental health” AND “school” OR “university”

Articles were screened for findings and relevance to the research questions posed. The following criteria were employed in the screening of articles:

• Source quality (years of publication 2011–2024)

• Context including geographical coverage (Australia and comparative countries)

• Document relevance (current approaches to supporting student and educator mental health and wellbeing); and

• Scope and areas of investigation (focusing on evidence-based mental health and wellbeing initiated in education spaces)

The analysis of literature involved several key steps: “skimming” (superficial examination), reading (thorough examination), and interpretation (see Bowen, 2009).

Phase 2: survey of educators and relevant school staff

To gain insights from the teachers and educators from across the different education sub-sectors (from early childhood to tertiary), the research team administered a short educator survey. This included questions regarding educators’ demographics, role and work setting. It also measured educators self-reported wellbeing, anxiety and intention to leave the education profession using well established validated scales. Educator wellbeing was measured using the 5-item WHO Wellbeing index (Topp et al., 2015). This scale has been in use since 1998 and translated into 30 languages as a measure of wellbeing with construct and predictive validity (Topp et al., 2015). Educator anxiety was measured using the GAD-7, a brief measure of generalized anxiety (Spitzer et al., 2006). The GAD-7 has good criterion, construct, factorial and procedural validity and good reliability (Spitzer et al., 2006). Intention to leave the education profession was measured using a scale developed by Arnup and Bowles (2016). This measure was found to have high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) and the study found good convergent validity with job satisfaction (Arnup and Bowles, 2016).

The survey also included an adapted measure of educator’s worry based on a brief Measure of Worry, designed by members of the research team and administered to capture insights into teacher worries during the COVID-Pandemic (see Van Der Zant and Dix, 2023). This scale used a brief purpose-designed measure, assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = some of the time, 3 = half of the time, 4 = often and 5 = always). Item reliability analysis (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) and confirmatory factor analysis (KMO = 0.80, p < 0.001) were employed and confirmed a single construct reflecting levels of worry. Possible scores on the instrument ranged from 1 to 5, with scores averaged to derive an overall indication of worry. A higher average score indicated a higher average level of worry.

For the present study, the scale was expanded to capture more detailed insights into the extent of educator worry, to determine the impact that stress and anxiety has upon the readiness of educators to support student mental health. Participants were asked about their perceptions of their own wellbeing and anxiety, and the extent of their worries, and the cause. Participants were asked to highlight the extent to which they worried about:

• Their workload

• Cost of living pressures

• How to support and include students with disabilities

• Students’ use of technology

• Students’ experiences of bullying and gender-based violence

• Pressure due to excessive testing and assessment

• Students’ experiences of cost-of-living pressures

• Your interactions with parents/caregivers

• How to support and including international/culturally diverse students

• Level of school refusal and student chronic absenteeism

• Students’ experience of COVID-19

• Personal experience of the impact of climate change

• Students’ experience of death or suicide of loved one

• Personal experience of the death or suicide of a loved one

• A student self-harming or suicide

• Students’ experience of the impact of climate change

• Levels of overdiagnosis and overmedication of students

• Personal experience of bullying or gender-based violence

• Students’ experience of extreme weather events

• Personal experience of COVID-19

• Personal experience of extreme weather events

Participants were also asked the cause of any intention to leave the profession (based on the worries above).

The survey was made available online (during February to April 2024) and hosted through People Pulse (a licensed Australian web-based survey platform). Due to the difficulty of obtaining participants due to the nature of the topic, snowball sampling was used to recruit the participants (teachers and educators) for this survey. This was done via sharing the links to the survey through direct emails to potential participants and requesting them to pass it on to their colleagues.

Phase 3: qualitative interviews with educators and psychology experts

Individual interviews were carried out with mental health care experts/workers from different settings (e.g., EC, school, and tertiary), using a semi-structured interview protocol. The aim of the interviews was to generate data for research questions 2 and 3, and focused upon perceptions of responsibility and support, insight on which programs/interventions are running in different education settings, and barriers and enablers experienced by educators. The interview protocol covered the key areas below:

1. Understanding how mental health connects with learning

2. How they/their site understands intervention effectiveness

3. How they choose where to spend their limited time and funds

4. What hinders educator capacity to support student’s mental health (i.e., barriers such as time, workload, or a lack of training/understanding of the relationship between student wellbeing and learning)

5. Enabling conditions that help mental health support to be integrated in schools and education settings, without adding to the workloads of educators.

Where feasible, interviews were conducted face to face. Face to face interviews were audio recorded and transcribed for qualitative analysis. A limited number of interviews were also conducted using live video conferencing (Microsoft teams was preferred as it allows for transcription and reduction of time associated with transcription for analysis), with follow-up communication undertaken by email if necessary. During the interviews, supporting documentation (i.e., details of mental health policies, programs, or interventions) was also requested, to enhance the conclusions drawn from the desk review and interviews.

Phase 4: data analysis, triangulation, and synthesis of findings

Given the study employed a mixed methods approach, the final phase of the study consisted of data analysis and triangulation of the quantitative and qualitative data sets. Data generated for surveys were cleaned before analysis and reporting. Survey responses with missing data were retained where the measures under consideration where complete but omitted for analysis of scales that were not completed. Descriptive statistics were generated for survey items to provide an overview of participant responses, while Pearson’s r correlations provided indications of the strength of associations and significance. Data was analysed using jamovi 2.6.17.

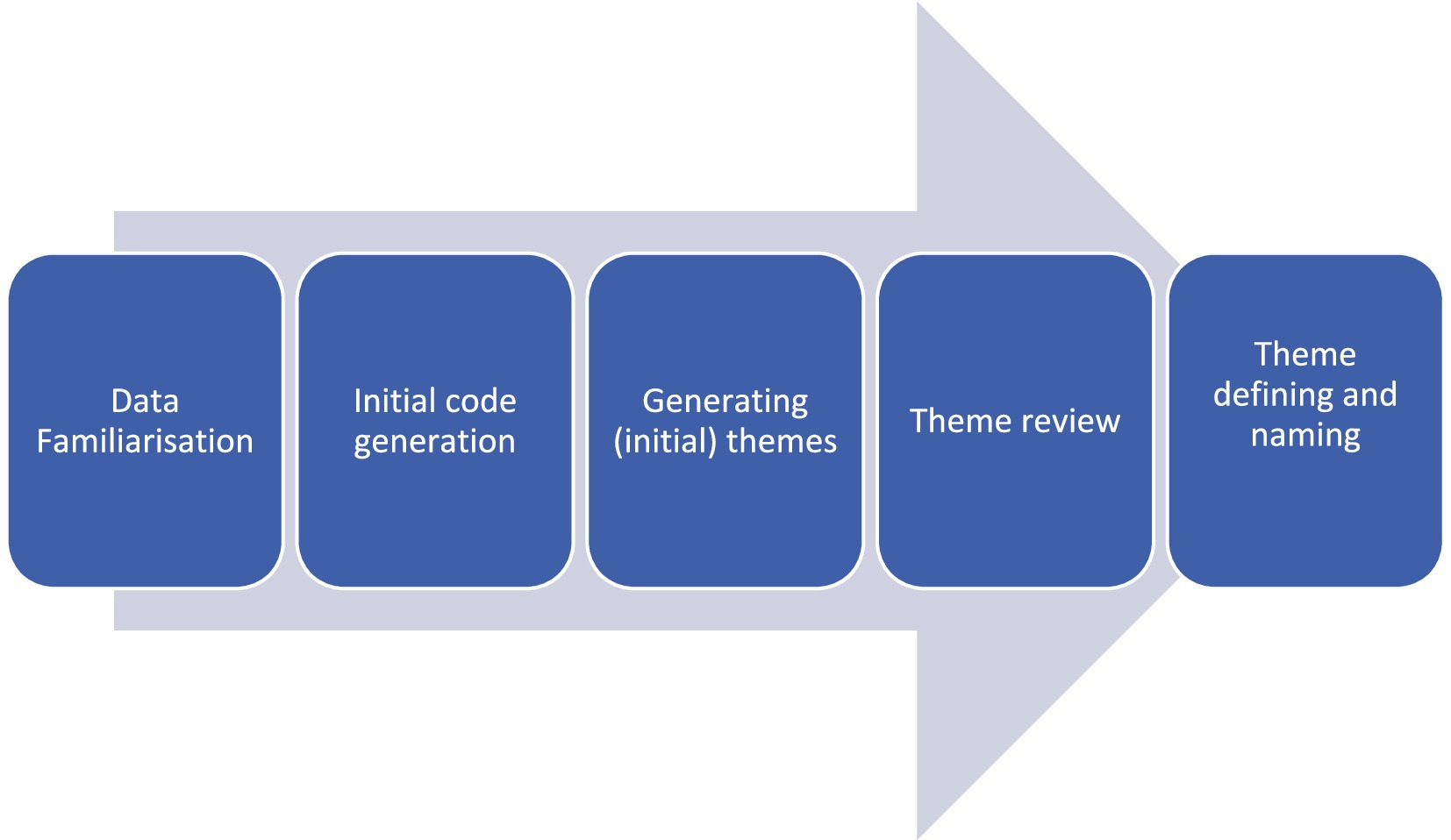

Analysis of open-ended survey responses and interview/focus group data were conducted using an inductive approach to generate key themes. There were six phases in the thematic analysis (Braun, 2019) as outlined below.

Familiarization involved immersion in the transcripts through several readings, conducted by separate members of the research team. Open coding was then conducted, before meaningful latent codes (Braun and Clarke, 2019; Cohen et al., 2017) were generated. The initial themes were then reviewed by members of the research team. At this stage, the decision to present school and tertiary level data separately was made, as the data sets were not cohesive due to the disparity of experiences described by educators.

The final component toward achieving trustworthiness and rigor in this study relates to triangulation of data. Triangulation involves cross examination of multiple sources of data, theories, and concepts, all of which aim “remove the single voice of omniscience [and] provide a rich array of interpretations or perspectives” (Gergen and Gergen, 2000, p. 1028). To increase the validity of research findings, the above data sources were combined, explored and synthesized to ensure a balanced and nuanced interpretation, noting key themes, enablers and barriers that educators face in supporting student mental health. The extant literature was also used to triangulate findings, and to make meaningful recommendations regarding the support that is needed to enhance the work of educators and their capacity.

Results

This section synthesizes key findings from survey and interview data. Data from the survey include participant demographics and educator perceptions of their wellbeing are first reported using descriptive methods, with relevant quotes from the open-ended sections of the survey used to give depth in the survey findings. This is followed by thematic reporting of interview findings.

Survey

This section presents the findings of the survey of educator worry, Phase 1 of the research.

Participant demographics

A total of 140 valid survey responses were received from educators across Australian and international early-childhood, primary, secondary, and tertiary institutions.

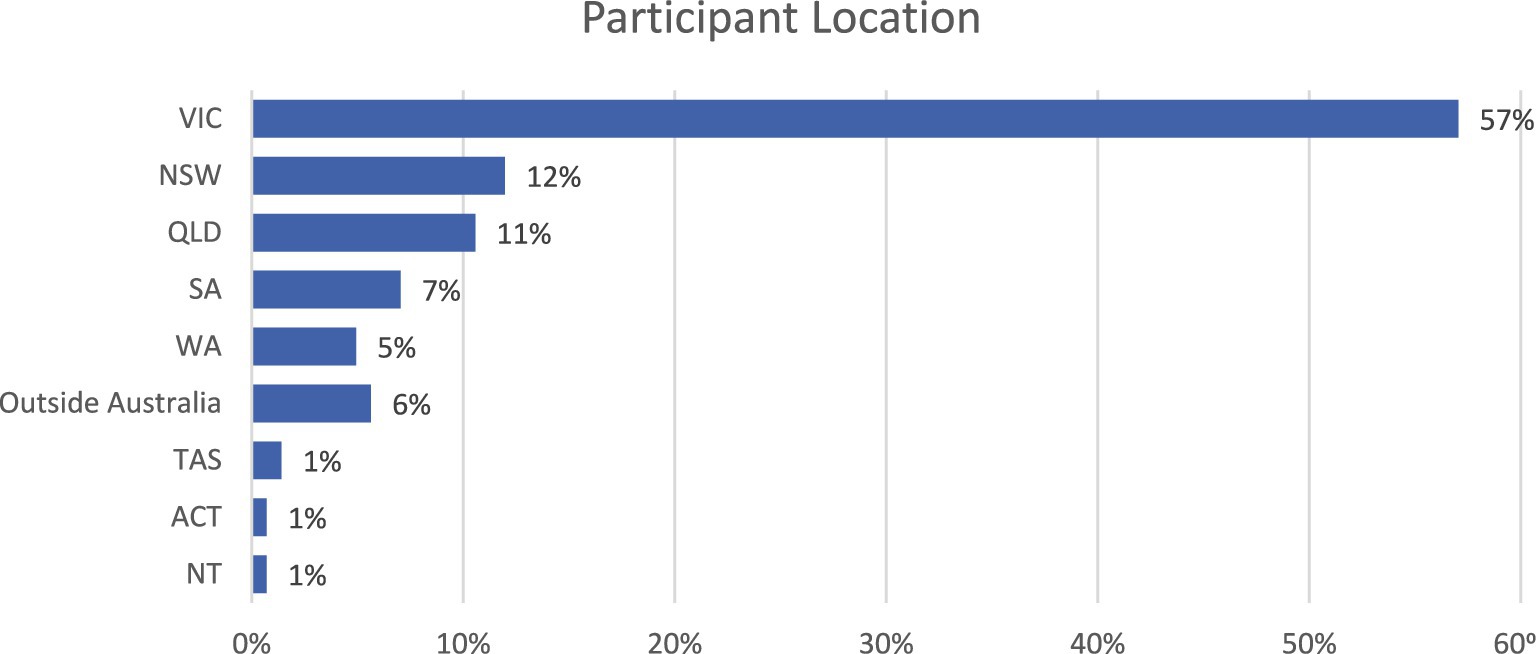

Figures 2–6 summarize the characteristics of participants who responded to the survey. Provides a breakdown of participation by location. The data suggests that most educators who took part in this survey were from Victoria, Australia. Of the six respondents outside of Australia (7.1%) two were from India and Indonesia, and Japan and the United Arab Emirates had one respondent each.

Figure 2. Phases of thematic analysis (from Braun, 2019).

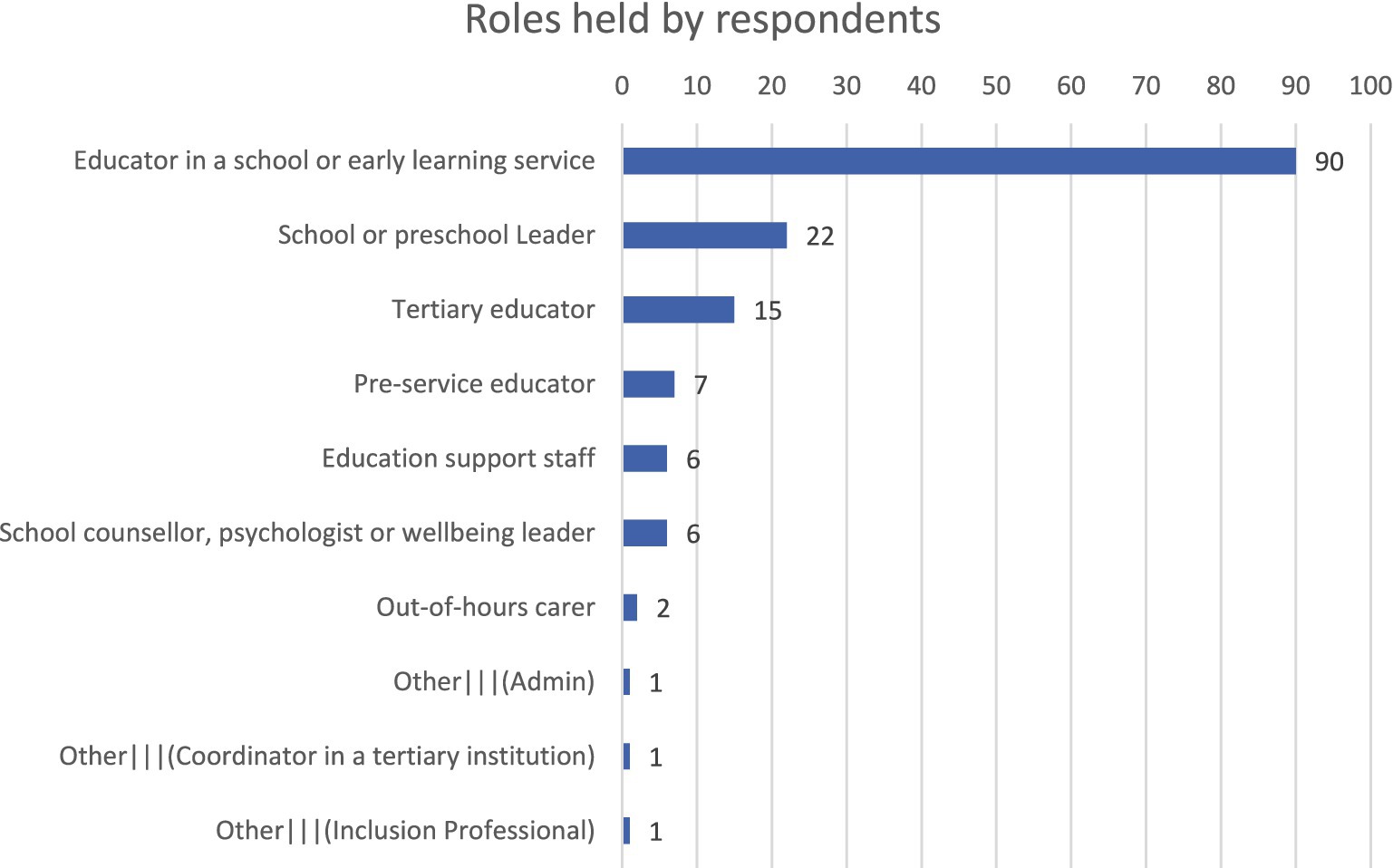

Figure 5. Number of survey participants who identified as holding each role (respondents were able to select multiple roles).

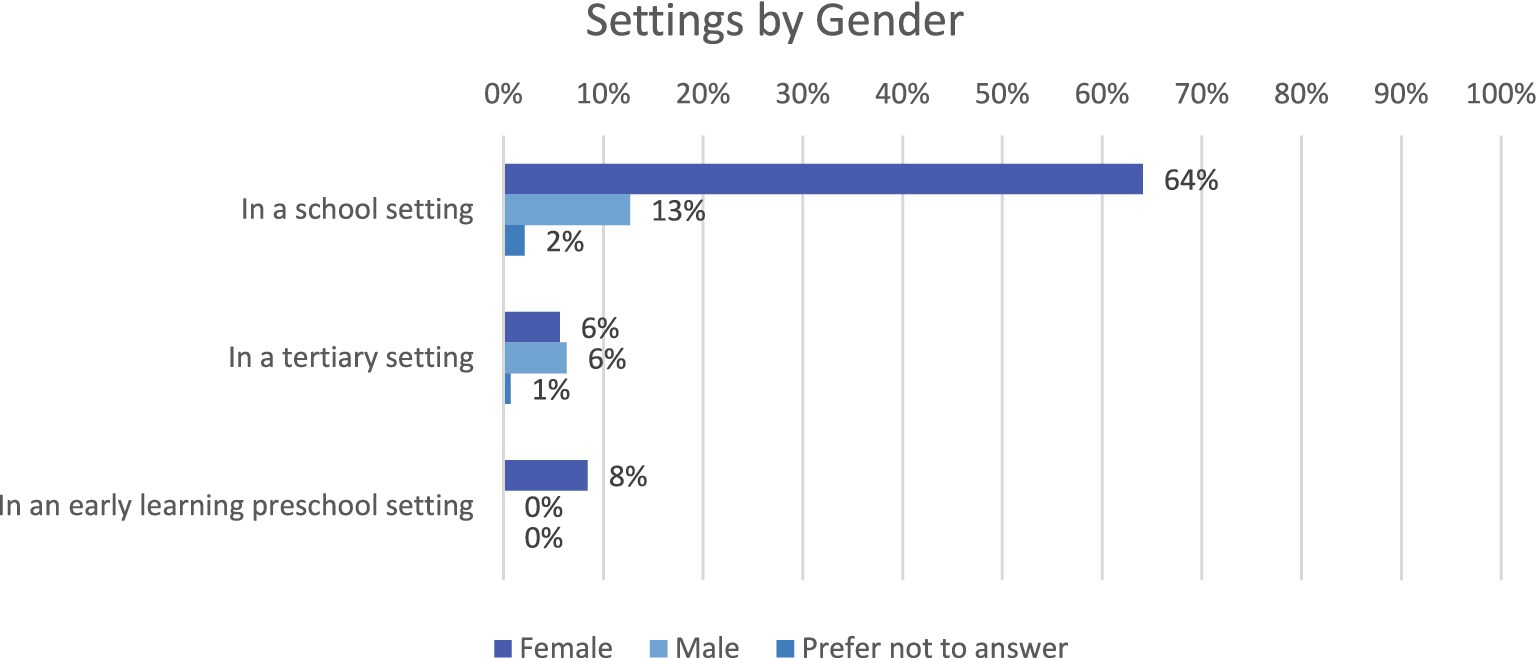

Figure 4 provides an overview of the educational settings where the survey participants work by the gender of respondents. Data suggests that most participants identified as females (78%) and working in school settings.

Figure 4 presents the distribution of the participants according to their sector and roles. Overall, educators from school settings have the highest representation in this survey, and as many as 58% of respondents identified as an educator in a school setting (Figure 5).

The overall low response rate reflected the limitations on the recruitment procedure (voluntary self-selection) and the increased demands on school/tertiary educational teachers and staff at the time of data collection – mostly during Term 1 of 2024. Many participants also reported being discouraged from speaking to researchers. However, given the low response rate, the results and analysis presented here should be interpreted with caution. The next set of figures are related to educators’ perceptions of wellbeing.

Educators’ perceptions of their own wellbeing

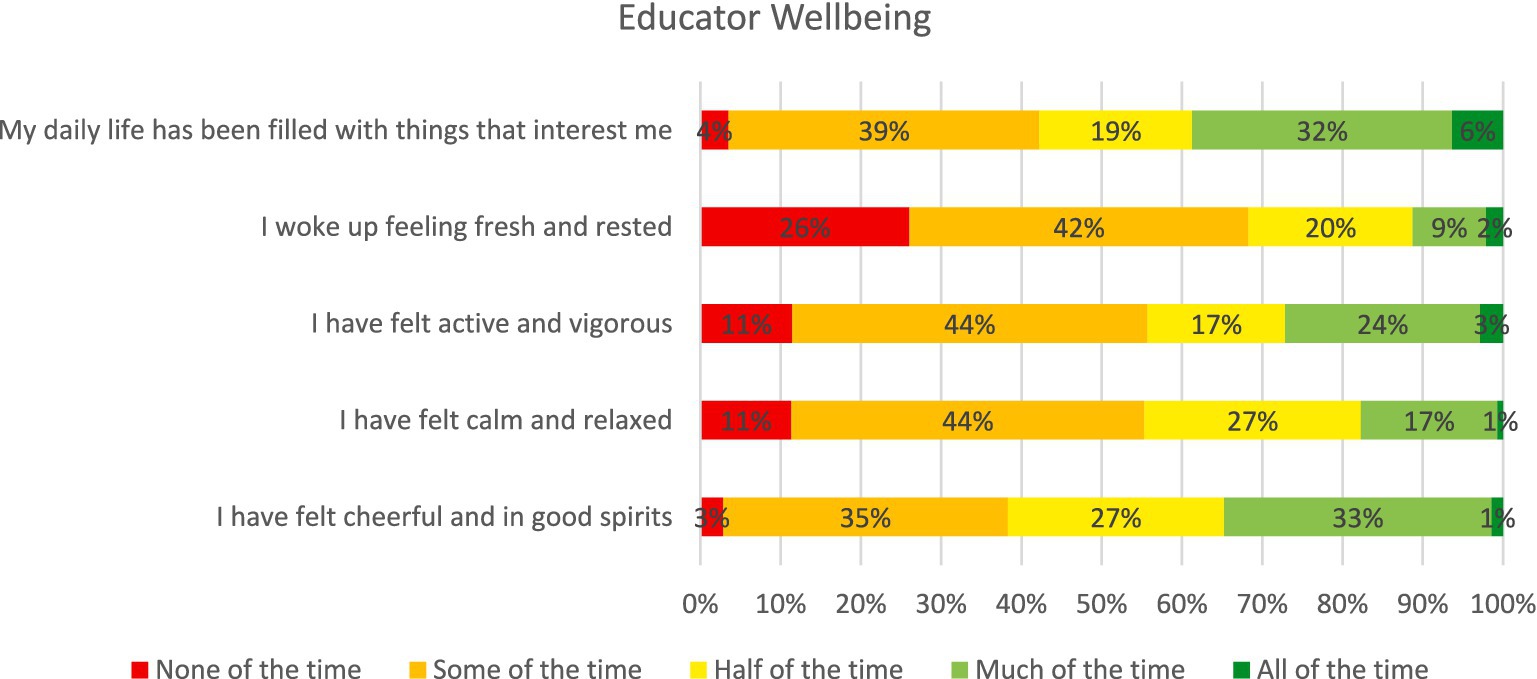

The first questions in the survey were focused on educators’ perceptions of their own wellbeing and anxiety. The responses to the first wellbeing item indicate that overall, the participants have been somewhat content and relaxed in their daily life (Figure 6). However, 26% of the participants note they are not feeling rested enough, which can indicate troubles with sleep and feelings of stress.

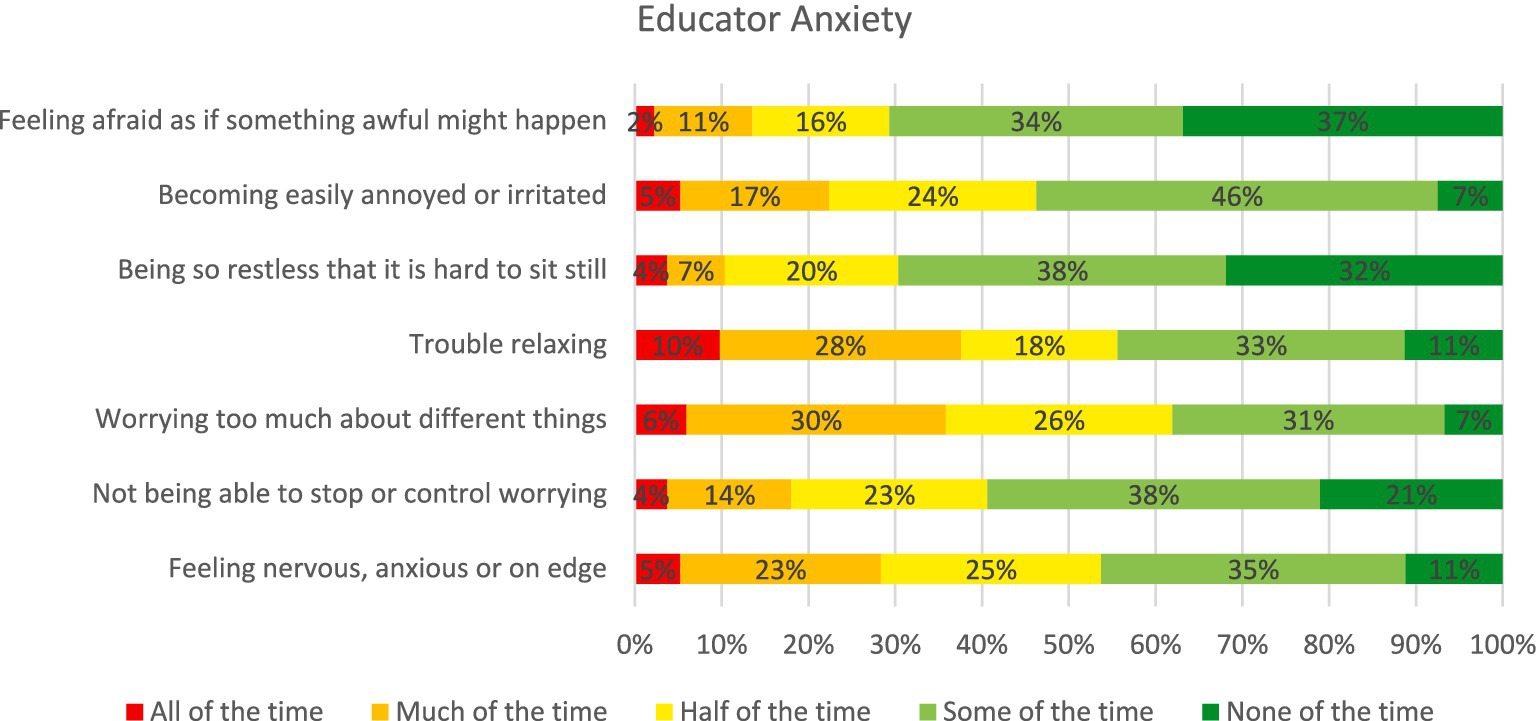

Figure 7 shows the findings around participants’ reports on generalized anxiety and stress. Again, the findings show that for many of the related items, a high percentage of participants are reporting high levels of stress and anxiety during half to all the time.

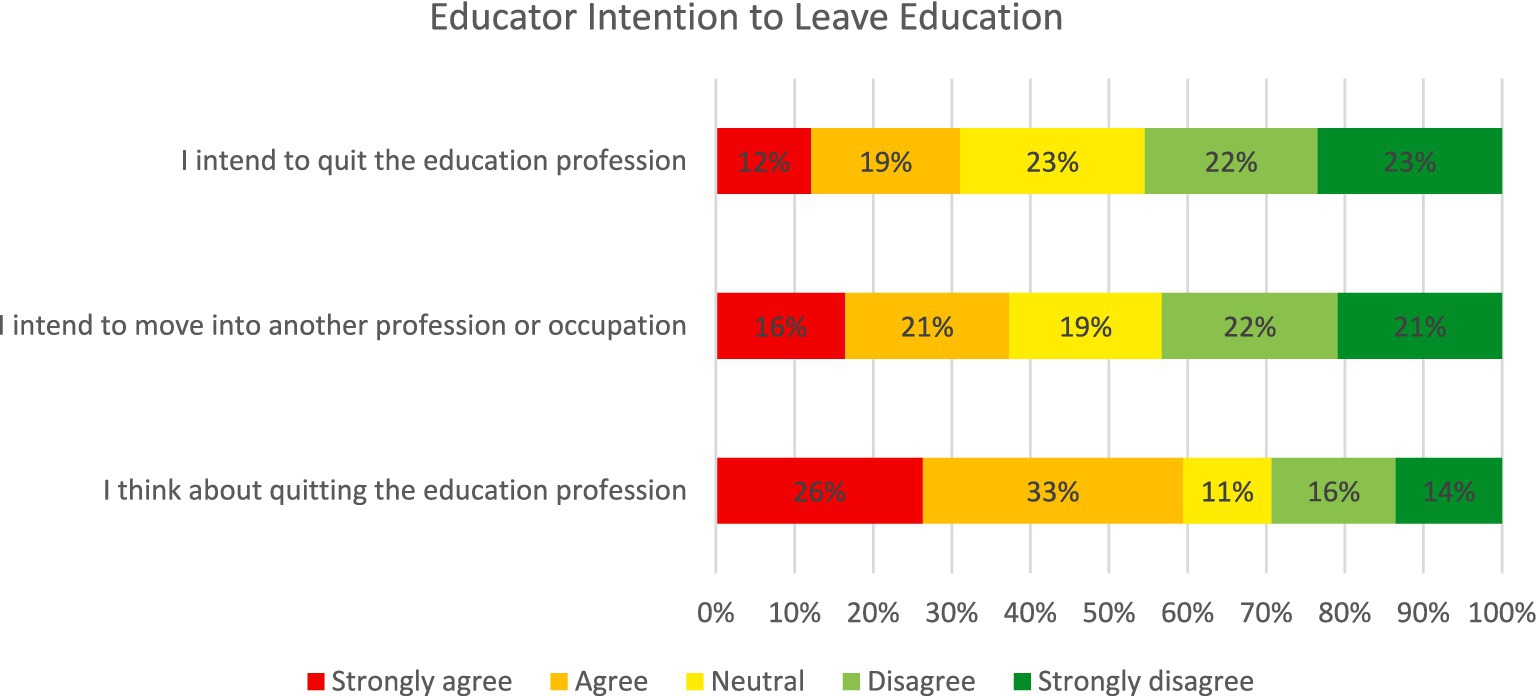

Figure 8 shows the educators’ likelihood of leaving the education profession. The numbers suggest some intend to quit or switch professions while more than half of the participants (59%) are actively thinking about leaving it.

The intention to leave the education profession was related to greater levels of general anxiety (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) and lower levels of general wellbeing (r = −0.52, p < 0.001). By combining the levels of worry educators reported across the listed topics (see Figure 9) it was possible to create an additional measure of Educator Worry (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). Educator worry, as measured by these questions, also related to general anxiety (r = 0.56, p < 0.001), wellbeing (r = −0.43, p < 0.001), and their intention to leave the education profession (r = 0.32, p < 0.001). An example of the impact of teacher worry is illustrated below:

“The worries we experience at school are often taken home and cause family problems and health issues, such as drinking, prescribed drug taking, family discord and even divorce. Critical events have resulted in extended sick leave or even resignation.” (Teacher).

“You end the lesson knowing that you have not been able to support Student A, who has a learning difficulty, as much of your lesson was spent deescalating a student or redirecting poor behavior. Or the faces of your students as you evacuate the classroom, that haunt you when you close your eyes at night” (Teacher).

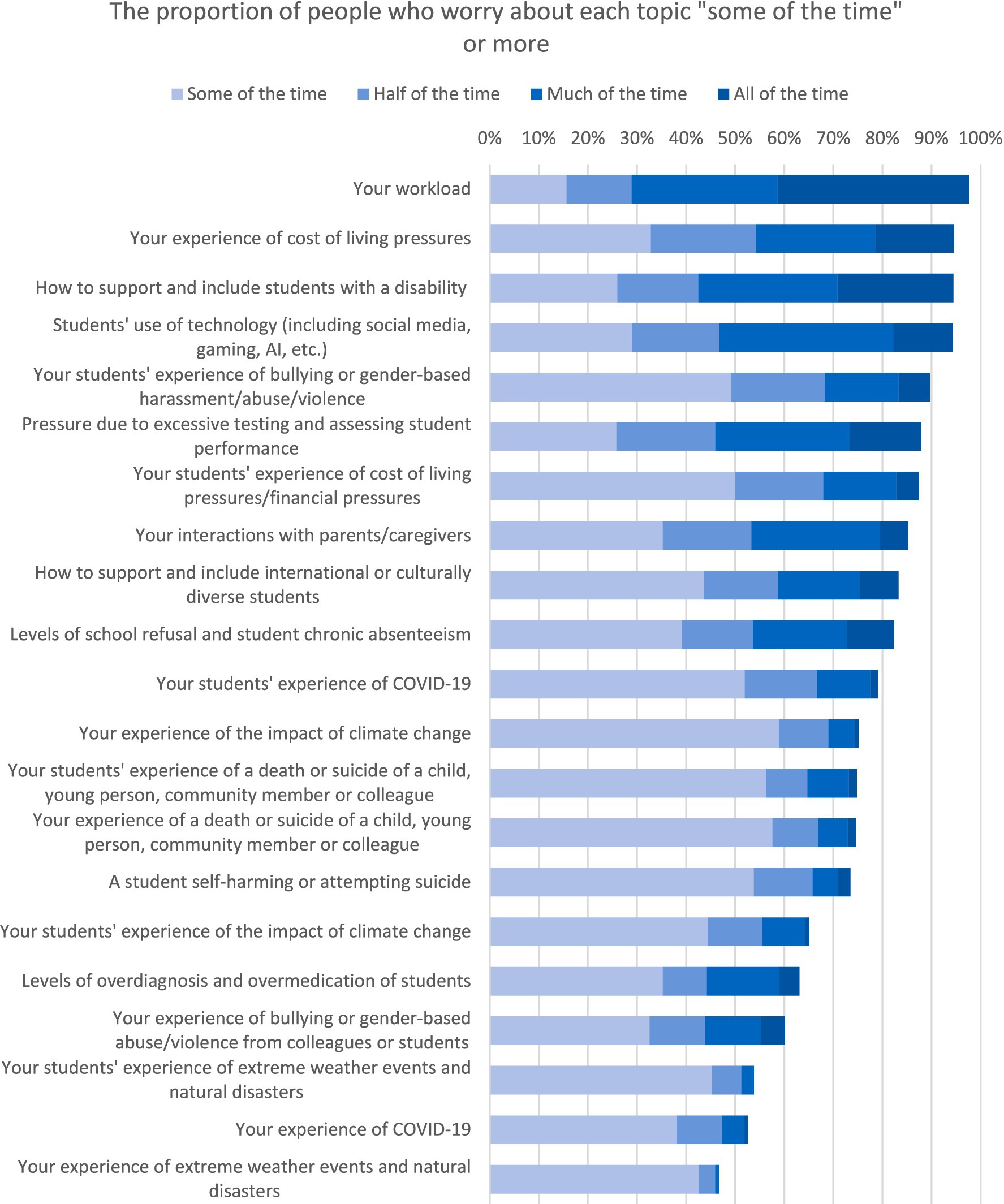

Figure 9 shows the data from the survey items that asked respondents about the major issues that they worry about, which are related to their role as an educator. The key issues reported in the survey include, educators’ own workload, financial pressures from cost-of-living increases, managing diverse needs in their classrooms and handling of experiences of bullying, interacting with parents and caregivers, and providing support to students coping with mental health issues.

These findings were further corroborated by open-ended responses to the survey, asking educators to describe their experiences of worry associated with their jobs in further detail. For educators based in schools, the worries most often reported were associated with declining student behaviors due to poor parenting (e.g., aggression, bullying, harassment, disengagement, defiance), exacerbated by the lack of structural support, accountability and leadership. Students with high needs were also a cause of worry, as with workplace bullying, and personal factors.

“My greatest concern is for our students. I have observed a pronounced increase in severe mental health conditions including violent behavior, suicidal ideation, self-harm, anxiety and depression. I am a school leader in a high performing school - I am finding that we are swamped with students presenting with complex mental health needs that we are not equipped to address” (School Leader).

“I think, I am not able to teach most of the time. It has turned into baby-sitting/behavior management. There are all kinds of expectations from school and parents, which cut too long in the teaching/preparation time. I am not able to give my 100%. Students blame me that I am being unfair/mean, make fun of me, the topic, and are very disrespectful” (Teacher).

“I am worried about students who actually want to study, and not lose themselves in peer pressure…. I worry about the students’ future. I worry about my own personal mental and physical health, which has suffered a lot during last few years. I worry that a lot of my patience gets used at my workplace and there is barely left for my own family/kids. I worry about the inflation and the mortgage, bills etc., I have to pay” (Teacher).

The main worries expressed by educators in the tertiary space were most associated with workload, including institutional commitments out of teaching, unrealistic job expectations, as well as navigating student disengagement.

“Workload and deadlines; ability to tailor teaching to meet student-learning needs and expectations; ability to adapt teaching to changing social/cultural and other circumstances such as changing patterns of student engagement, student preparedness for study, attention and wellbeing issues” (Tertiary Educator).

“We need management to listen to teachers on the front line (who are professionals) and know what will improve teacher wellbeing and staff retention. We are often told what is best but never asked” (Teacher).

Open-ended survey responses also suggest educator reluctance to report instances of workplace bullying in schools, largely due to perceived lack of supportive leadership and the fear of repercussions.

“How rampant bullying occurs between staff and there is little done because it is not “severe” enough to formally complain, and if you do, it causes more issues/advised it’s not worth doing for the sake of your job/wellbeing.” (Teacher).

“…bullying by students with ineffective leadership support and communication pathways to discuss supportive strategies to be able to teach academic content” (Teacher).

“Leadership gaslights staff. Treat teachers like we are ungrateful and complaining too much. They make decisions that worsen our workload and do not action any feedback we give. Support starts with respect and understanding of what teachers do. Leadership do not get it…” (Teacher).

Intention to leave the profession

The top three topics of worry that related to participants’ intention to leave the education profession were their workload (r = 0.35, p < 0.001), their experience of bullying or gender-based abuse/violence from colleagues or students (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), and their experience of cost-of-living pressures/financial pressures (r = 0.31, p < 0.001). With educator workload and experiences of cost-of-living pressures as the two most common topics of worry amongst our participants, the fact that these are also strongly associated with an intention to leave the profession is alarming.

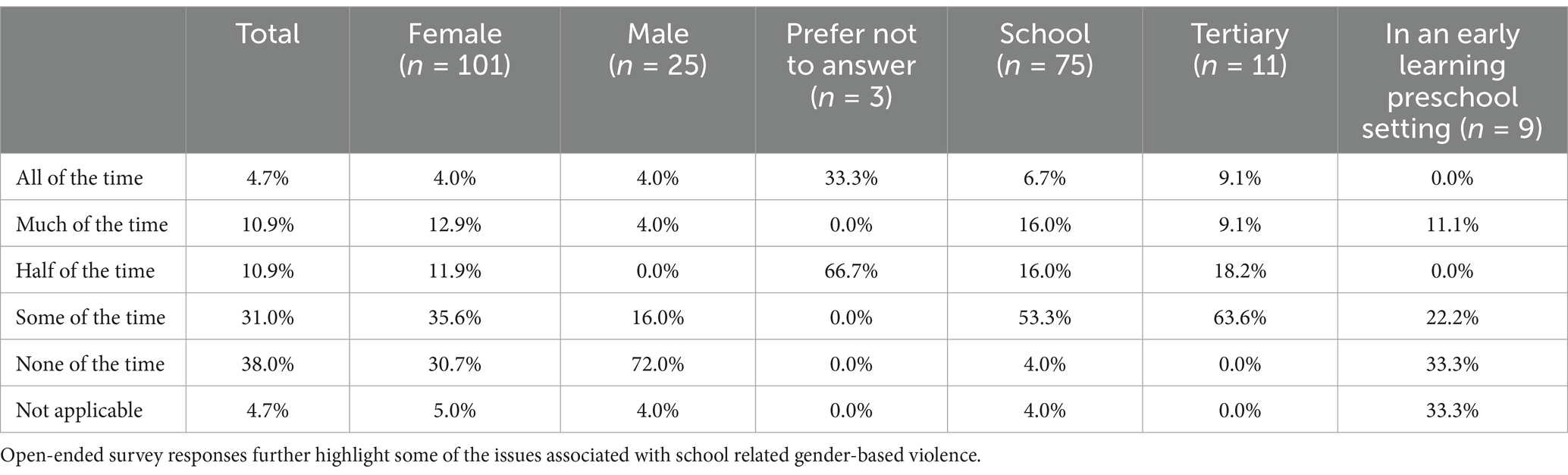

Furthermore, while worry regarding educator experiences of bullying or gender-based abuse/violence in the workplace was comparatively low, this was one of the strongest predictors of educators’ intention to leave the profession. Table 1 shows further analysis of survey responses, with 60% of educators having experienced bullying or gender-based violence from colleagues or students, with females more likely to indicate so.

Table 1. Educator’s experience of bullying or gender-based abuse/violence from colleagues or students.

“Being accused of harassment or coming on to a female student” (Teacher).

“Aggressive students when on yard duty. I am reluctant to engage with them when their behavior is bad, due to verbal abuse and physical intimidation experienced in the past” (Teacher).

“My main worry is keeping everyone safe in a support class with a student who is a known sexual predator” (Teacher).

With the strength of association between worry about experiencing bullying or gender-based abuse/violence from colleagues or students and their intention to leave the education profession, there is clear concern to investigate this issue further, particularly in relation to mechanisms of support and policies to retain educators in the profession.

Interviews

To build upon the findings generated by the survey, interviews were undertaken with a range of education stakeholders working in school and tertiary settings, including classroom teachers, leadership, lecturers, tutors, psychologists, and school support staff. While a key focus of the interviews was to understand the enabling conditions that support educator readiness, most interviewees described deteriorating conditions in schooling characterized by high workload, feeling overwhelmed, and burnout.

The interview protocol covered five key areas:

1. Understanding how mental health connects with learning.

2. How they/their site understands intervention effectiveness.

3. How they choose where to spend their limited time and funds.

4. What hinders educator capacity to support student’s mental health (i.e., barriers such as time, workload, or a lack of training/understanding of the relationship between student wellbeing and learning).

5. Enabling conditions that help mental health support to be integrated in schools and education settings, without adding to the workloads of educators.

Based on a thematic analysis of qualitative data, this section presents the findings of these interviews in more detail.

School settings

Many interviewees working within settings where mental health and wellbeing initiatives were being implemented described clear processes for reporting and referral. However, all school participants who were interviewed described increasing pressures in their roles, and emphasized the extent to which student needs and family demands continue to evolve. As a result, an overarching theme of the school interviews was the perception that there are multiple, complex obstacles in school settings that restrict and reduce their capacity to support students. Interviewees described these barriers as impacting on their own health and wellbeing, and subsequently, their ability to support the needs of their students.

Changing roles and responsibilities

Education staff working in and within schools raised a wide variety of issues related to their roles and responsibilities that impact on their readiness to support student health and wellbeing. Interviewees reported that it has become common for educators to be expected to address the mental health needs of students, parents, and colleagues, often without adequate training. This additional responsibility has gradually been incorporated into their roles, imposing further demands on educators who are already managing substantial workloads, and contributing to a state of overwhelm, even amongst new teachers.

“…burnout has always been something that we have reserved for, or that used to be used for people who were nearing the end of their careers. But now we are seeing teachers within their first five years within their first seven years, young teachers describing symptoms of burnout. And I think we need to be asking, as a profession, what’s going wrong? It should not be a common experience amongst teachers” (Teacher).

Interviewees also reported that the support structures currently in place are insufficient to address the changing needs of students, with some educators reporting that their work environments, as well as role expectations, lack the necessary support structures and exacerbate the challenges they face as educators.

“I cannot even get workbooks marked and collect guided reading books because it is taking me so long to plan my lessons and then create differentiation and list all the students for each level of differentiation. It makes me extremely anxious about the process, the lengthy grilling I will get” (Teacher).

“So we know that that gaming addiction is presenting more readily… We learn about what addiction is, how that affects the brain. What we do not learn is how do I, as a teacher, respond to the child in front of me, who is 30 min deep into their computer and gaming, and so addicted that any attempt to move them away from that, or to try and engage them in the lesson, could result in an absolute exclusion of temper and of dysregulation… That attempting to take a gaming a device or a device away from a student when they are there is not helpful. Not for the student, not for me, and not for the 31 other kids who are gonna have to witness what that might look like” (Teacher).

Some educators who participated in interviews also noted the difficulties of dealing with evolving issues around gendered abuse and problematic student behaviors, including sexism, sexualized behaviors, and misogyny in schools, and the relatively low levels of preparedness to address such issues.

Relationships between parents and educators

As an increasing number of mental health programs are introduced in schools across Australia, the role that parents play in supporting the needs of students was discussed widely in interviews. Interviewees reported the involvement of parents as complicating their roles, and often leading to conflicts or misunderstandings that disrupt their ability to teach and work with students. While some interviewees suggested that parents are increasingly anxious about their children developing mental health conditions, sometimes without warrant, others suggested challenges of engaging families whose children require support.

“…the kids get in the car at the end of the day and the parents are almost looking for a problem for that day, for the parents to come in and save them at the end of the day. And I understand that because we think this mental health crisis is sitting in this cloud about to strike… we have to keep talking about emotions because God, you know, they might have been struck by, you know, mental health” (Clinical Psychologist).

“Often what we’ll see is that the parents that are, you know, not necessarily needing that extra support that we are identifying… how do you gently work with the parents in that space without bringing that shame to say you should attend because your child has just done this, and we have recognized that”? (School Leader).

Interviewees also reported a shift in the relationship between teachers and parents, and noted that the collaborative partnerships that once existed between families and educators have become increasingly strained. Some interviewees suggested that parents are becoming the adversaries of educators, creating anxiety and stress in the workplace, and that care is needed to work with the families of students experiencing difficulties.

Lack of support from leadership

From the perspective of interviewees, schools are increasingly marked by significant pressure, due to high expectations and stringent accountability. Additionally, teachers reported a lack of autonomy, respect, and trust which they perceive as restricting their ability to make independent decisions and diminishes their sense of purpose and value and overall wellbeing. While there may be efforts at a leadership level to provide assistance to teachers, interviewees reported that these attempts are often ineffective, leaving teachers to navigate an unsupportive environment.

“We have new leadership who have clearly been promoted beyond their capacity and have little capacity to communicate effectively and see questions as direct challenges to their authority even when they clearly are not” (Teacher).

Interviewees described the system within which they work as being broken and overwhelmed. Educators described an environment that is characterized by superficial practices, “ticking boxes,” toxic interactions with colleagues and parents, and overall exploitative practices that leave teachers on the brink of breakdown. Ultimately, teachers report feeling left to find the help they need on their own, further exacerbating their sense of isolation and frustration.

“Part of the reason the EAP’s1 aren’t working is because teachers often see them as a bureaucratic box exercise, something that their employer puts into place to almost protect themselves… and so they are reluctant to buy in because they see it as a compliance, rather than offering robust, timely and real support” (Teacher).

Additionally, as educators progress into leadership roles, the absence of appropriate training often persists, leaving them less prepared to provide the necessary support to their teams. This lack of preparedness can perpetuate a cycle of inadequate support throughout the educational system.

Responsibility for help seeking

Another significant concern raised by interviewees is a growing expectation that educators should independently seek out the assistance they require themselves, despite the possibility that the appropriate support may not be readily accessible. Some educators reported finding it challenging to identify their own mental health needs, or to navigate the process of obtaining assistance in their workplaces before their mental health had deteriorated to the point of being unable to work. Apprehension about potential repercussions was also cited as deterring many educators from seeking help.

“…certainly, for me when I was in the grip of it, I wasn’t able to articulate what was happening for me. I did not understand it. Myself, I wasn’t able to articulate what I needed because I did not know what I needed” (Teacher).

“Working with students and their families, I’ve made referrals to the very support services that I should have accessed. I work in the system… I would be very familiar with those support services. I know how to access them. I know where they are. I know the people I could have called and yet I did not. Partly I did not because I did not recognize those flags as being illness” (Teacher).

“One-size-fits-all” approaches to student wellbeing

Interviewees also reported an increasing tendency for schools to amalgamate a broad range of wellbeing initiatives and mental health support services, along with interventions that purport to address the needs of students with additional challenges or behavior management issues into a singular, generalized approach. Some interviewees suggested that such conflation risks diminishing the effectiveness of interventions by not responding to the specific needs of individual students, while other interviewees suggested that the growing demands of parents was the reason for a more generalized approach to wellbeing support.

“The stuff that’s happening, the wellbeing stuff that’s happening in schools. It’s air. It’s pleasant air that you breathe for a while. And you leave. And smog is outside…” (Clinical Psychologist).

Interviews with school sector participants also suggested that there is an absence of detailed information regarding the quality of mental health interventions being implemented in schools. In particular, the educators who participated in interviews suggested that there was not always an evidence-based selection process to identify effective programs, and that some programs were driven by parental advocacy efforts, or the involvement of external providers. One wellbeing coordinator reported that her school was “constantly” contacted by service providers promoting “mental health products.” Other interviewees also noted that the schools they work in are under increasing pressure to demonstrate they are responding to student mental health needs, even if there is a lack of evidence as to the efficacy of programs that are being invested in.

“Schools are, and this is my big concern with these wellbeing programmes and schools are sinking an enormous funding into these, so those wellbeing apps on average $20 per student. OK, that is a huge investment. And all that is to me, it’s no different than a school buying scales. If a school bought scales that is not a solution for obesity crisis. It’s a measure. You still have to address it” (Clinical Psychologist).

Overall, school-based interview data suggests that educators working in schools face ongoing challenges to their own mental health, with high workloads, poor support structures, and increasing pressure from parents and students. Many of the educators who participated in the study also described concerns about reporting the issues they raised, for fear of repercussions from school leadership, or within the education sector in which they worked. Interestingly, educators also struggled to describe practices that were working well in their settings, despite it being a core focus of the interview protocols.

Tertiary settings

Tertiary participants also described a range of contextual barriers associated with their role, which they saw as impacting on their ability to provide student support. However, unlike school participants, tertiary educators highlighted the challenge of supporting student mental health and wellbeing due to lack of clarity over reporting, referral, and assistance services.

Workload

Tertiary educators who were interviewed reported difficulties in meeting the mental health needs of students due to rising workloads and insufficient institutional support. Interviewees working in tertiary institutions cited the stress of balancing teaching, research, marking, and supervising students, in addition to increasingly competitive expectations to publish research, apply for grants, and contribute to the academic community as contributing factors to their own mental health status as well as their ability to support that of their students. Committee participation and curricula development, and more recently, online teaching, were all seen as contributing to exhaustion amongst tertiary staff.

“When you become an academic, when you start working in a university, you are on email for the rest of your life. Like, that’s just how it is…” (Lecturer).

Job insecurity and staff turnover

Tertiary educators who participated in the study reported facing numerous challenges, many of which they attributed to job insecurity, short term contracts, and the high reliance on casual staff. The precarious work environment was seen as creating stress amongst educators, also leading to frequent staff turnover, disrupting continuity, and preventing students from establishing long-term, supportive relationships with a regular educator. As a result, many interviewees suggested that students do not have the opportunity to form connections with teaching staff, and thereby do not feel comfortable reaching out for support when challenges arise or to disclose underlying mental health concerns that may affect their success in their program of study. Some educators also reported that when working on short term or sessional contracts they did not receive training in the process for supporting or referring students with mental health concerns as this was usually only offered to permanent staff.

“The more sessionals you have, the less continuity you have. That’s one of the key problems of having lots of sessionals, not only for the sessional person themselves, but for the university… you sacrifice a lot by not having permanent staff” (Subject Coordinator).

“You have all the new tutors going through this training that have not been there for a long time thinking, alright, well, that’s outside of my pay grade” (Lecturer).

“I think everyone needs to take a beat to go, what does the landscape actually look like? Because if we are going to have people who want to stay around, yeah, who are fit for work, for longevity, we have to invest in them” (Head of Student Services).

Stress and support

In addition to their workload, educators in tertiary settings reported experiencing high levels of stress, largely due to the weight of responsibility they feel in supporting adult learners. This stress is further exacerbated by inconsistent wellbeing and mental health support mechanisms across different contexts or discipline areas. For example, some interviewees felt that programs in health and medical fields, were seen to integrate mental health and resilience training into the curriculum, while other programs, including education, do not offer the same level of support. The absence of training on specific student behavior management for pre-service teachers, and the development of strategies for working with students in real-world classroom challenges was another concern raised by interviewees.

Educators who participated in the interviews reported that mental health support systems for staff are minimal, despite acknowledging the high levels of stress linked to workloads, job insecurity, and the lack of senior or peer support, particularly for sessional or casual staff. A common concern among these educators was the lack of transparency and accessibility of mental health resources for both students and staff. Educators highlighted their own need for mental health support to manage the demands of their profession, especially as they are expected to consider and respond to the mental health needs of their students. Interviewees also reported that when mental health policies are in place, they are often too difficult to navigate.

“There’s such little training, you know for staff, and what I’ve certainly noticed, I guess, is the compassion… of staff just reduces cause they are all burnt out and fried themselves” (University Tutor).

Interviewees also reported that the tertiary institutions they worked in struggle to maintain consistent messaging and effective support systems. Across a variety of institutions, educators who were interviewed expressed frustration with the existing blanket policy approach, which they feel fails to address the specific needs of their students and their own responsibilities as instructors.

“We’ve all done it. We’ve got the memo or the meeting minute or the policy, which is that’s no longer my fault because I’ve [the University] put that policy out there” (University Tutor).

“Do a self-paced HR thing because then you have got work, health, safety. We’ve ticked that box, that we are all compliant” (University Tutor).

These insights emphasize the need for more practical, concise information regarding support services, for both staff and students.

Diverse student needs

The changing needs of students, especially in terms of neurodiversity and mental health challenges, were highlighted by interviewees as requiring more targeted resources and attention. Educators identified the changing demographics of student cohorts and highlighted the increasing numbers of pre-service teachers reporting personal mental health concerns affecting their ability to successfully complete mandatory course requirements such as school-based placements.

“I do not think I anticipated the volume of students who were going through the process of being diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, for example, or dealing with transgender issues and other kind of gender and sexuality issues. Or the number of students who are trying to cope with anxiety, and particularly in an online environment” (Subject Coordinator).

Some educators voiced concerns for how pre-service teachers experiencing mental health difficulties may preclude them from undertaking mandatory course requirements, and discussed how this may also affect their ability to manage when working in classroom environments.

“If your anxiety is that acute, how do you cope with the demands in a contemporary secondary classroom?” (Subject Coordinator).

“Does education attract students who are experiencing difficulty at school? I do not know… Why would you become a teacher if you hate school” (Lecturer).

Interview participants also reported difficulty in supporting international students. For international students and their educators, the challenges of early intervention and support for mental health are further complicated by language barriers, cultural differences, and limited familiarity with Australia’s healthcare system. Some interviewees highlighted the extent to which international students face isolation due to being far from home and their usual support networks, increasing their vulnerability to mental health struggles. Interviewees who worked closely with international students described the reluctance of such students, particularly students who may have been high performing in their home countries, to seek help prior to a crisis or mental health emergency.

Moreover, online teaching environments were reported to create additional barriers in forming relationships with students, particularly for international students, which interviewees saw as potentially discouraging students from seeking help. Interviewees also noted that virtual and blended approaches to teaching make it more difficult to check in regularly, build rapport, and become a trusted source of support for students.

“They’ll come and listen to me, but they’ll get to me when we are at breaking point with, you know, I’m the one that’s sitting with them in emergency. By that time, it’s too late. So because we have already had an attempt on life or we have already done something or we are about to be committed and you know…it’s too late” (Head of Student Services).

“… maybe they are a bit more reluctant to access help at university. You know, they have already been reasonably successful at school. They think they can cope, but the level of complexity of the work….” (Subject Coordinator).

Overall, the data suggests that there is disparate provision of tangible and accessible mental health supports for tertiary educators and their students. Interviewees described the complexity of navigating internal policies and practices of tertiary institutions, including training requirements for staff, especially casual or sessional staff.

Discussion: educator readiness to support student mental health

Education settings play a critical role in promoting, protecting, and caring for children’s and young people’s mental health. However, the complexity of the linkages between health, mental health, and psychosocial wellbeing and learning have placed increasing pressure on the education profession.

The research presented in this report suggests there is disparate evidence of educators’ readiness to support student mental health. In school and tertiary settings, educators report high levels of stress and worry, and poor quality or tokenistic resources and support structures, including promoted “teacher wellbeing” initiatives which at times contribute to stressors of workload cited by educators. Where access to resources is available, educators report having little time to access or use them. In addition, the increasing pressures of mental health, wellbeing, and inclusion reforms, which have been designed to better support students and enhance their engagement in learning, appear to be of detriment to the lives and experiences of many educators. As investment in student mental health agendas has accelerated, educators describe increasing workloads, overwhelm and stress, and experiences of bullying and harassment, all of which can be seen as contributing to their intention to exit the education profession. The factors impacting on educator capacity, and their subsequent readiness to support student mental health, are discussed in more detail below.

Trust, accountability, and increasingly high expectations

The findings presented in this report suggest that poor accountability amongst school communities, and low levels of trust and respect for educators leads to low morale and motivation. Participants of this study also highlighted the extent to which the media, parents, and policymakers express their ideas about the roles educators are playing without understanding the realities on the ground, which impacts on their capacity to undertake their roles, and to support students in their care. Furthermore, the exceptionally high demands of managing students in diverse classrooms, and the “need” to be flexible for every child, as well as the expectations that educators should be managing all kinds of problematic behaviors, appear to be causing high levels of stress for educators. Some of these challenges have been discussed in the literature (Hascher and Waber, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2022; Kamarunzaman et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2024), contributing to a growing number of teachers reported to be “at breaking point” (Windle et al., 2022).

“The enormous amount of responsibility that is built into our jobs that are not entirely in our control. So many external agents, e.g., school boards, government mandates and policies do not allow us to do what is best for children. Society has forgotten what schools are for. In the race to live modern lifestyles or the necessity of both parents needing to work to sustain lifestyle choices, parents do not or cannot parent well” (Teacher).

“Teachers today are expected to teach the curriculum and measure their students’ learning, design individualized education plans, collaborate with families and communities, undertake PD, manage difficult classroom behaviors, understand all students’ needs, fill out a variety of surveys and carry out numerous assessments” (Teacher).

Research has shown that many education systems are lacking in the level of support they need to create an enabling environment for student mental health (Breuer et al., 2016; Rathod et al., 2017; Barker et al., 2021). As Windle et al. (2022) have noted, educators continue to be tasked with managing a “proliferation of top-down initiatives” (p. 1) without sufficient time, resources, training, or support from school leadership (Hascher and Waber, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2022, as cited in Karnovsky and Gobby, 2024). As a result, teachers increasingly bear the responsibility for supporting student mental health, when mental health intervention should be supported by specialist services, as well as parents alike.

Educator workload and individual wellbeing

The research presented in this report identifies workload as a key factor causing stress amongst educators, with many study participants reporting this to be an issue. Educators described rising levels of administrative work, coupled with increased accountability and reporting requirements, as having a major impact on their motivation, wellbeing, and overall capacity. These findings are well established in previous literature (McCarthy et al., 2016; Harmsen et al., 2018; Kamarunzaman et al., 2020). Some researchers have suggested that the structure and organization of schools have led to increased educator workloads (Braun, 2019; Thompson et al., 2020). The rapid shift to remote learning during the pandemic, coupled with the need to support students in new ways, has also likely further exacerbated the pressures educators face (Jerrim et al., 2024; Silva et al., 2021).

However, the extent of anxiety, worry, and stress described by study participants is a complex issue, with multiple issues described as contributing to educator wellbeing. Psychological exhaustion and deterioration of educator’s own mental health and wellbeing as a direct result of workplace pressures have been well described in the literature (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Harmsen et al., 2019; Farewell et al., 2022). Interestingly, although the educators who participated in this study reported a myriad of relationship-related stressors, there also appeared to be a general reluctance to seek help until it was too late.

“I was slow to put all that together…when I look back now, I think it’s quite astounding when this [supporting the needs of others] is the very space I’ve been working in, so I was able to see it for other people. But I just could not, I did not recognize it in myself until unfortunately I’d passed this point, and I let it go on for too long. So, some of the symptoms escalated when they did not need to, had I intervened earlier and got that support earlier” (Teacher).

However, the experiences of educators who are intending to leave the profession, or have exited due to fatigue and exhaustion, has only recently been described in the Australian context (Heffernan et al., 2022). However, the complexity of emotions associated with educators who had left or were contemplating leaving the profession, was also highlighted in this study.

“People who leave, teachers who leave the profession will describe a grief process and are grieving, because there are so many elements of the job that that we love doing” (Teacher).

Relationships with colleagues, students, and parents

Educators in schools and tertiary settings appear to struggle with inadequate policies, ineffective enforcement, and weak reporting mechanisms, which allows bullying and harassment of educators to persist across all levels, including from parents. Currently, the burden of addressing wellbeing and behavior issues appears to fall heavily on educators, contributing to their stress and workload. In addition, difficult relationships with colleagues, students, and parents were cited as contributing to educator worry and stress, with parent expectations on educators a potential source of strain.

“Parents… they place so much responsibility on educators to perform what should be parenting responsibilities” (Teacher).

“The lack of support from leadership when dealing with behavior in the classroom, or when dealing with parent complaints/questions. We are left to fend for ourselves, and leadership always bends to the will of the parents rather than risk losing enrolments- even if the decisions are detrimental staff and our concerns have been raised in consultative meetings” (Teacher).

“There is support but the abuse and interference and intimidation from parents is increasing and there is no recourse in that area. You have to just accept it while they complain about you and what you do” (Teacher).

Although the number of participants included in this study was small, educator responses about gender-based harassment, abuse, and violence was cited as one of the key reasons educators intend to leave the profession. This is an emerging issue that should be explored in more detail, although some research has now begun to examine the way in which gender norms that promote male dominance and female submission, reinforced by media, violent or misogynistic content online, peers, and family structures, contribute to a culture of tolerance for abusive behaviors directed at educators (Haslop et al., 2024; James, 2023; Schulz, 2024; Wescott and Roberts, 2023; Wescott et al., 2023).

In response, many schools and settings have started to realize the need to implement whole of school programs around gender-based violence (GBV) and building more inclusive environments. However, although Australian school-based initiative such as the respectful relationships education toolkit or the Our watch2 resources for preventing gender-based violence in schools and tertiary settings exist, it is likely that the structures within education settings, and the extent of stress and worry described by educators in this study, may not be conducive to these types of programs being successfully implemented.

Capacity to foster an inclusive environment for all students

Many school-based mental health initiatives require specialist training and high levels of professional development for teachers and parents alike, yet there is still a paucity of evidence on the extent to which educators have capacity to engage with such interventions. Further research highlights that certain groups of students are more prone to bullying and peer victimization such sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth (Baams et al., 2021; Coulter et al., 2018; Fish et al., 2017; Russell and Fish, 2016) which often means educators who are supporting these students will have a higher level of worry related to managing these issues in their classrooms. This was also highlighted in the survey results where worry was highly related to dealing with students’ experience of bullying. Given the diversity of student needs, educators must be supported and empowered to increase their understandings of mental health, as well as to integrate inclusive teaching approaches that reflect the diversity of learning challenges in their classroom.

Truly inclusive schools promote help seeking behaviors amongst both educators and students (Kutcher et al., 2015, 2016), and school communities need to work collaboratively to build such environments. Inclusive education specialists or coordinators can also be helpful to reduce some of the burden. While specialized training can support educators to carry out many of these tasks, having access to professional staff may be required at certain stages, particularly where the needs of student populations are high, and there are low levels of trust about teachers’ capacity. However, issues such as casualization, overwork, emotional exhaustion, and the burden of emotional labor also continue to impact on the profession (Bellocchi, 2019).

In the tertiary education sector, many educators highlighted concerns around the increasing number of pre-service teachers presenting with mental health concerns of their own. Tertiary educators questioned how this may impact the ability of pre-service teachers to support the students in their classrooms with mental health difficulties upon entry into the teaching profession. The current climate of teacher shortages in many areas of Australia has meant teachers are in high demand. While it is critical to ensure that Australia’s tertiary programs are able to support meeting these industry needs, quality standards for teachers, whose role it will be to support the next generation of students, must not be compromised. Emerging teachers with mental health concerns can still be a strong asset to the profession, and to the students they support, however, these teachers must themselves be properly supported.

Conclusion and implications

Overall, the rise of student mental health remains a pressing public health issue in Australia, and education settings provide a unique platform to identify and address these issues for young people, allowing them to be better prepared and equipped to draw on internal and external supports throughout their lives. Governments and policy makers have a responsibility to support educational institutions in promoting positive mental health outcomes and strategic investment in effective and accessible supports, which may contribute to reducing the financial and social burden of mental health challenges across the lifespan. Ultimately, linking different support services and ensuring educators have the help they require to be able to support all under their care is the key to ensuring that the education system is functioning well and meeting the needs of all students, including those with complex needs.

Educators play a critical role in the promotion of equity, inclusion, quality, and relevance within education systems, and there is an established link between teacher mental health and their capacity to support their students. However, there remains a lack of detailed research on the current pressures facing educators, and the implications for educational systems and student learning if educators are not well supported, and do not know what they are working toward, or why. As the body of research on the importance of supporting student mental health grows steadily, there are also concurrent pressures placed on educators to be vigilant, aware and ready to support student mental health needs across the Australian education system (Gunawardena et al., 2024).

The research presented in this paper highlights the significant challenges faced by educators as they struggle to manage student mental health concerns across educational sectors. This study provides a basis for identifying some of the unique challenges faced by educators, however, there were limited insights on the practices that support students- and educators- in meaningful ways. While providing training, time, and integrating mental health support into daily practices can promote educator commitment, involvement, and acceptance of student mental health programs, there is also a need to identify opportunities that can better support educators. Further research is required to comprehensively investigate the mental health support systems and services provided by school and tertiary institutions, and to identify the efficacy and accessibility of these services. Future research could also investigate causal relationships between experience, stress, and self-efficacy. Employing longitudinal or experimental designs could help to identify specific influencing factors that support educator readiness.

Recommendations: Investing in educators

The findings presented in this study suggests that many educators are feeling stressed, and that the diversity of student behaviors are a contributing factor to reduced teacher capacity and motivation. These findings also align to prior research, indicating that high levels of stress cause educators to experience low levels of confidence and motivation to provide support to students from different backgrounds and with different needs (Hascher and Waber, 2021; Kamarunzaman et al., 2020).

Although educators’ experiences are negatively affected by education policies and organizational conditions, the prevailing narratives around wellbeing continue to emphasize strategies that promote individual self-management of wellbeing (Karnovsky and Gobby, 2024). As the data presented in this report suggests, there is clearly an urgent need to better support educators. Encouraging the uptake of resources and tools by parents and families, rather than letting educators carry all the burden of support for student mental health, could help mitigate some of the mental health impacts that educators describe as a reality of their work. A more balanced approach to supporting student mental health would involve shared responsibility between families and schools, fostering a collaborative approach to student mental health and wellbeing that recognizes the degree of challenge facing educators.

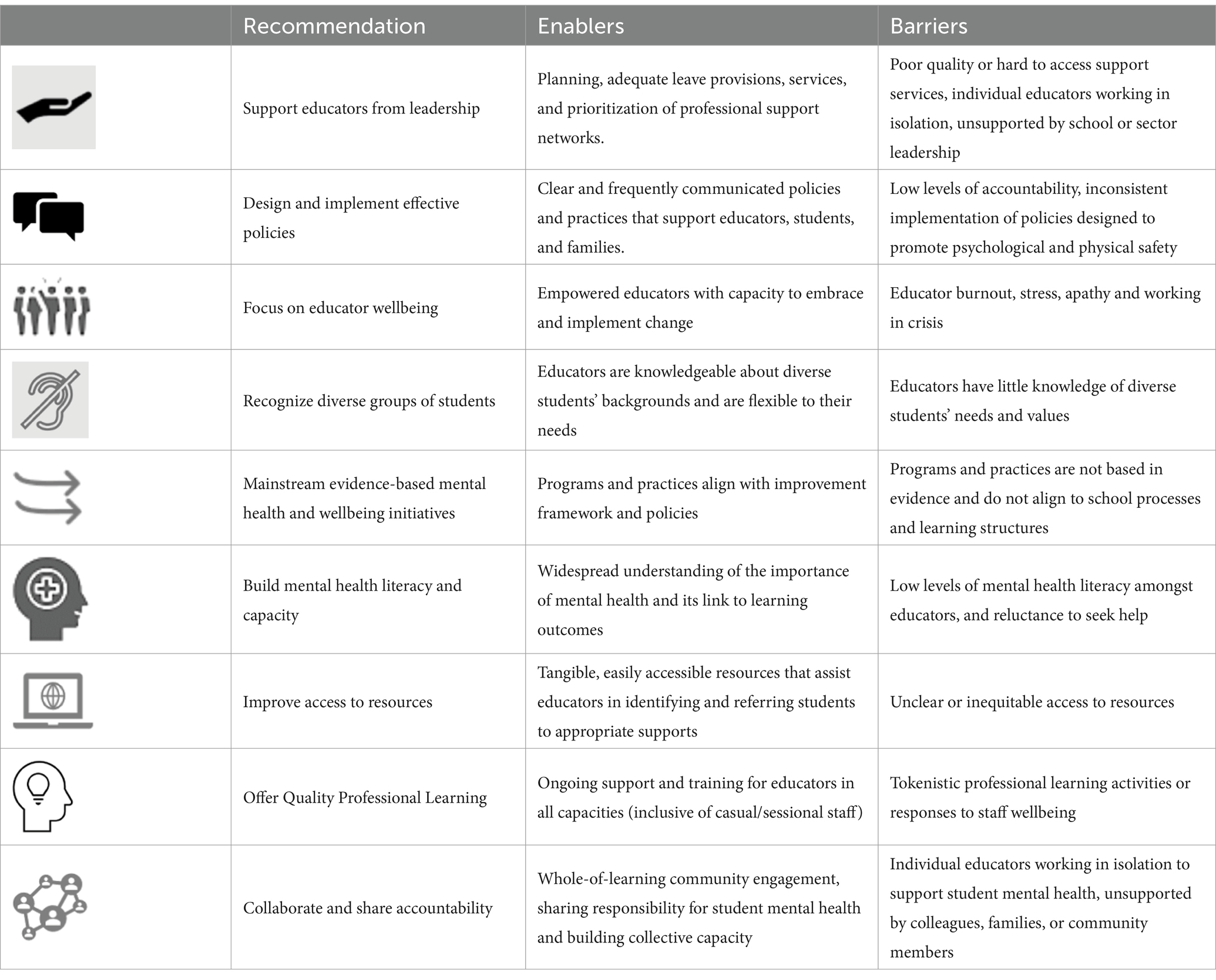

Table 2 below provides a summary of recommendations that can support educators to assist students across the life span, coupled with the enablers and barriers to educators supporting student mental health. These recommendations are informed by current evidence and findings from this study, with a focus on outlining support structures that challenge dominant discourses of resilience and self-management of wellbeing which often ignore the complexities of educators’ work. The points presented below could form the basis of guidelines that recognize the challenges facing educators, and their need for shared support in their work with students at different stages of development.

Limitations

It must be acknowledged that there are certain limitations associated with the data presented in this paper. The low survey response rate reflects one of the limitations of the recruitment process, which used voluntary self-selection and a snowballing strategy. This approach, coupled with the increased demands on school/ tertiary educational teachers and staff at the time of data collection – mostly during Term 1 of 2024 (Southern Hemisphere) led to low participation rates. Some participants also reported being discouraged from speaking to researchers due to the nature of the topic. Fear of retribution from management and perceived risk of opportunity loss was particularly prevalent in the tertiary sector, which relies heavily on casual and temporary staff, many of whom work across different settings. While the sample size is an important limitation, it also highlights the challenge of collecting representative data on this topic. Finally, it should be emphasized that the insights offered in this report do not offer a representative sample of educator experiences across Australia, but instead are designed to provide new insights that can be leveraged in future research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement