- Maynooth University Department of Education, Maynooth, Ireland

Introduction: With concerns about school attendance problems (SAPs) increasing across the globe, this study sought to explore the varied experiences of young people, parents and practitioners, to uncover barriers to attendance and explore the responses and interventions that support successful pathways for students with school attendance challenges. The study, conducted in Limerick, Ireland, was concerned with participants’ lived experiences, including their experiences of themselves, of their interactions and relationships, and of the complex patterns that co-arise between themselves and the larger systemic context. It was informed by a trauma-informed conceptual framework, known as EMBRACE.

Methods: Four cohorts of participants were purposively sampled: (1) educators (n = 15; school leaders, teachers, alternative education staff), (2) allied professionals (n = 12; psychologists, social workers, community workers etc.), (3) parents (n = 2, both mothers), and (4) young people (n = 11, aged 14–18 years). Online focus groups were conducted with the professional groups. In-person interviews were carried out with parents. The young people participated in either individual interviews or focus group interviews and arts-based methods (self-portraiture and body mapping) were used to facilitate thoughtful, embodied communication in a safe and supportive space. Data was analysed using reflective thematic analysis, with professionals’ data analysed separately to that of parents and young people.

Results: The findings indicated that successful resolution of SAPs depends on the creation of an inclusive, responsive, and flexible mainstream education system, that can meet the needs of diverse learners within a fully resourced continuum of support model. In addition, alternative education pathways (including home tuition and online provision) were considered vital. This study reaffirms the importance of creating space for interagency collaboration and for forging strong relationships characterised by compassion, trust and mutuality, at all levels - between children and young people, parents/carers, colleagues, educators and professionals in other organisations. A special focus is required to help address inordinate structural barriers faced by disenfranchised groups (including the Traveller community in the Irish context).

Discussion: By ensuring that students are listened to, believed, and empowered to actively participate in shaping their educational experiences, it is possible to create successful educational pathways for all students, regardless of their background or circumstances.

1 Introduction

While attending school is a positive and rewarding experience for most students, School Attendance Problems (SAPs) are increasing in many countries around the world, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic (McDonald et al., 2023; Tomaszewski et al., 2023). This is a major cause for concern at individual, community, and societal levels. Chronic absenteeism disrupts students’ personal trajectories, limiting their long-term educational and career prospects (Kearney and Graczyk, 2014). It also affects overall school climate, rupturing relationship and lowering teacher morale (Devenney and O'Toole, 2021). Additionally, absenteeism impacts society as students miss core aspects of the curriculum along with lessons in civic engagement and democratic participation, which ultimately leads to a less educated society, hindering social and economic transformation.

Understanding the processes and pathways that are successful in promoting school attendance is therefore crucial. Traditionally, approaches to improve attendance have focused primarily on the individual student/family level; this, however, can distract from the multi-layered and intergenerational causes of SAPs (Childs and Lofton, 2021). For instance, it is evident that criminalizing, fining, or otherwise punishing parents for school non-attendance has been utilized with limited efficacy, and with very negative consequences for individual families (Childs and Grooms, 2017). Similarly, school attendance campaigns, while well-intentioned, risk stigmatizing families, particularly those facing challenges, like illness, housing instability, poverty, or other adversities (Hinsliff, 2023). Thus, there is a need for greater understanding of the barriers to attendance and more holistic, compassionate, personalized, and multi-layered responses (Heyne et al., 2024).

Within the Irish educational context, data shows that rates of absenteeism are consistently higher in schools located in areas of socio-economic disadvantage. They also confirm unequal educational attendance, retention and progression for particular groups, including immigrant children and those with disabilities (Darmody et al., 2008; Denner and Cosgrove, 2020; Millar, 2018). The figures for Irish Travellers—a traditionally nomadic ethnic minority group indigenous to Ireland—are particularly concerning. Traveller students face significant barriers to school attendance and educational progression at all stages; from primary through to secondary, and to further or higher education. For instance, only 13% of Traveller children complete second-level education compared to 92% in the general student population, and the number of Travellers who progress to higher level education represents just 1% of the entire Traveller community (Department of Justice and Equality, 2017). The reasons for these gross disparities can be examined at multiple levels, but have root causes in extreme marginalization, exceptionally high levels of prejudice, discrimination and intergenerational trauma (AITHS, 2010; McGrath, 2023; Quinlan, 2021).

1.1 Theoretical framework

Much research on school absenteeism has been largely atheoretical and not clearly linked to understandings of the role that trauma and adversity play in shaping students’ educational experiences and outcomes. The importance of adopting an ecological trauma-informed perspective is two-fold. Firstly, childhood trauma is extremely common and has been linked to various types of school attendance problems, including chronic school absence (Stempel et al., 2017), school dropout (Morrow and Villodas, 2018), suspension, expulsion and detention (Sanders et al., 2023; Stewart-Tufescu et al., 2022). Childhood adversity also predicts lower school engagement (Bethell et al., 2014) and poor educational outcomes (Blodgett and Lanigan, 2018). Reporting on the situation in Ireland, Thornton et al. (2013) noted that family trauma (e.g., parental conflict, maternal depression) was so commonly associated with absenteeism that attempting to tackle it without addressing underlying issues would be futile. Moreover, an ecological or systemic perspective is crucial in recognizing the social determinants of trauma and the complex interplay between individuals and broader educational, socio-economic and cultural systems (O’Toole, 2023; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 1998).

Secondly, while most research on childhood adversity focuses on traumatic experiences within family or community contexts; it is important to recognize that schools themselves can be trauma-inducing. There is nothing new in this assertion; since their inception schools have harmed children, although it is only in recent years that have seen efforts have been made to clarify what is meant by school-based trauma and map the available research. In her scoping review, Duane (2023) notes five types of school-based trauma: institutional betrayal, which is the failure of a school to protect individuals who depend on its services, racialized harm (e.g., discrimination, lack of representation), policing tactics (harsh discipline, coercion, seclusion), teacher abuse (e.g., yelling at, belittling, or humiliating children), and peer victimization (e.g., peer physical or sexual assault, bullying). All the above can cause long-term harm to children and the school communities and points to the need for trauma-informed approaches in schools (Duane, 2023; O’Toole, 2022).

The current study utilized a trauma-informed framework called EMBRACE (www.traumainformededucation.ie/our-framework; O’Toole, 2023) to guide research design, analysis and interpretation. The study adopted trauma-informed values and principles (i.e., collaboration, empowerment, trustworthiness, safety, respect for diversity; Harris and Fallot, 2001) and was concerned with people’s lived experience, including their experience of themselves, of their interactions and relationships, and of the complex patterns that co-arise between individuals and the larger systemic context (Goleman and Senge, 2014). The purpose was to explore the varied experiences of young people, parents and practitioners to uncover barriers to attendance and explore the responses and interventions that support successful pathways for students with school attendance challenges. Thus, the methodology was designed to inquire into the affective, cognitive, and bodily/somatic experiences of key actors within education and other social systems (Fuchs, 2017; Herrmann et al., 2021).

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and recruitment

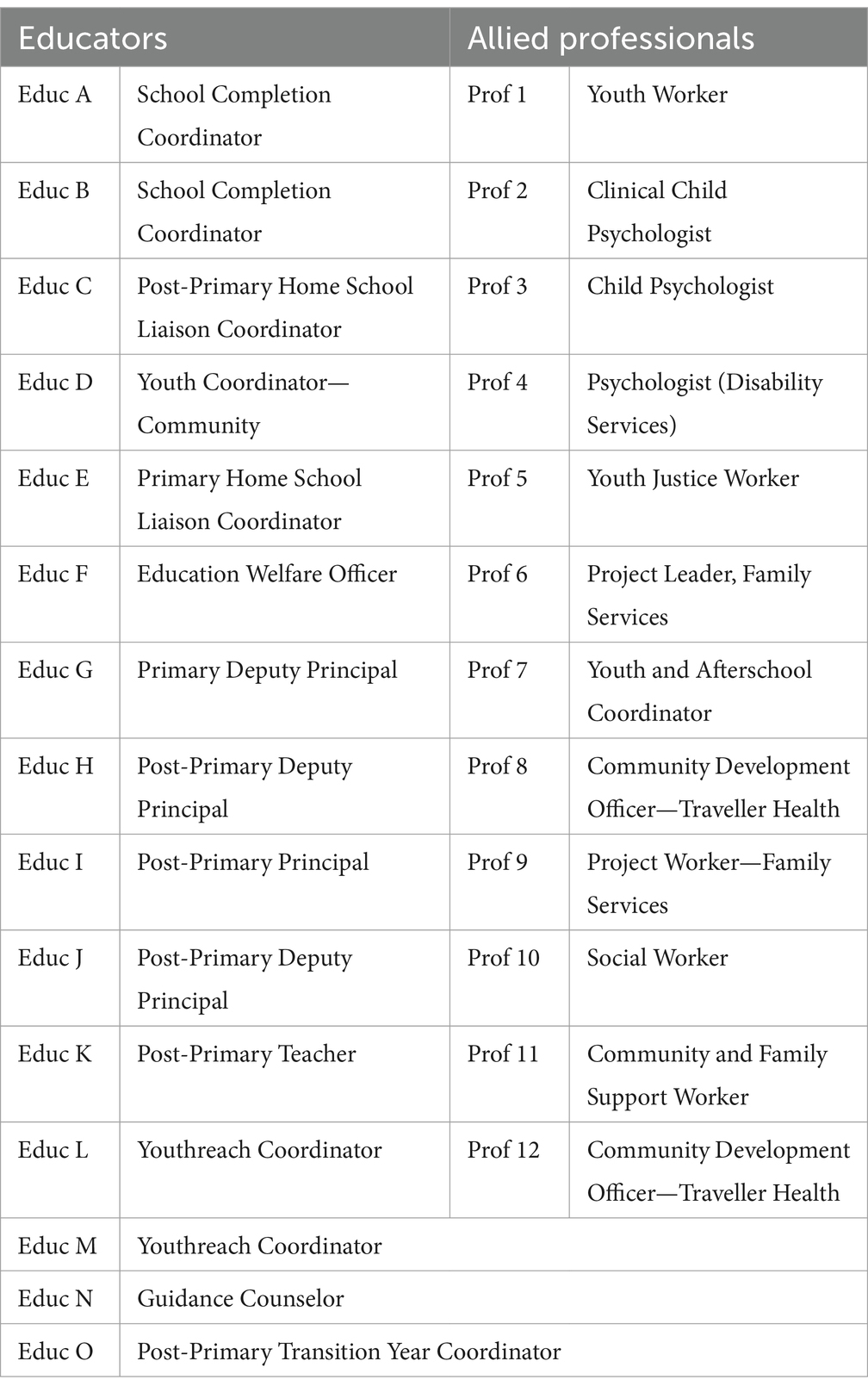

We employed a purposive sampling strategy to recruit participants with specific insights into SAPs. To ensure a broad range of perspectives, we included three cohorts: professionals, parents, and young people. Regarding the professional cohort, we included both educators and allied professionals. As shown in Table 1, the Educators group (n = 15) consisted of those working in the education sector who had experience supporting students experiencing SAPs; these included teachers, principals, guidance counselors, home-school liaison staff, and educators in alternative education settings. The Allied Professionals group (n = 12) consisted of practitioners in various sectors, including child and adolescent mental health services, disability services, social work, youth work, and the criminal justice system who had also supported young people experiencing SAPs in their roles.

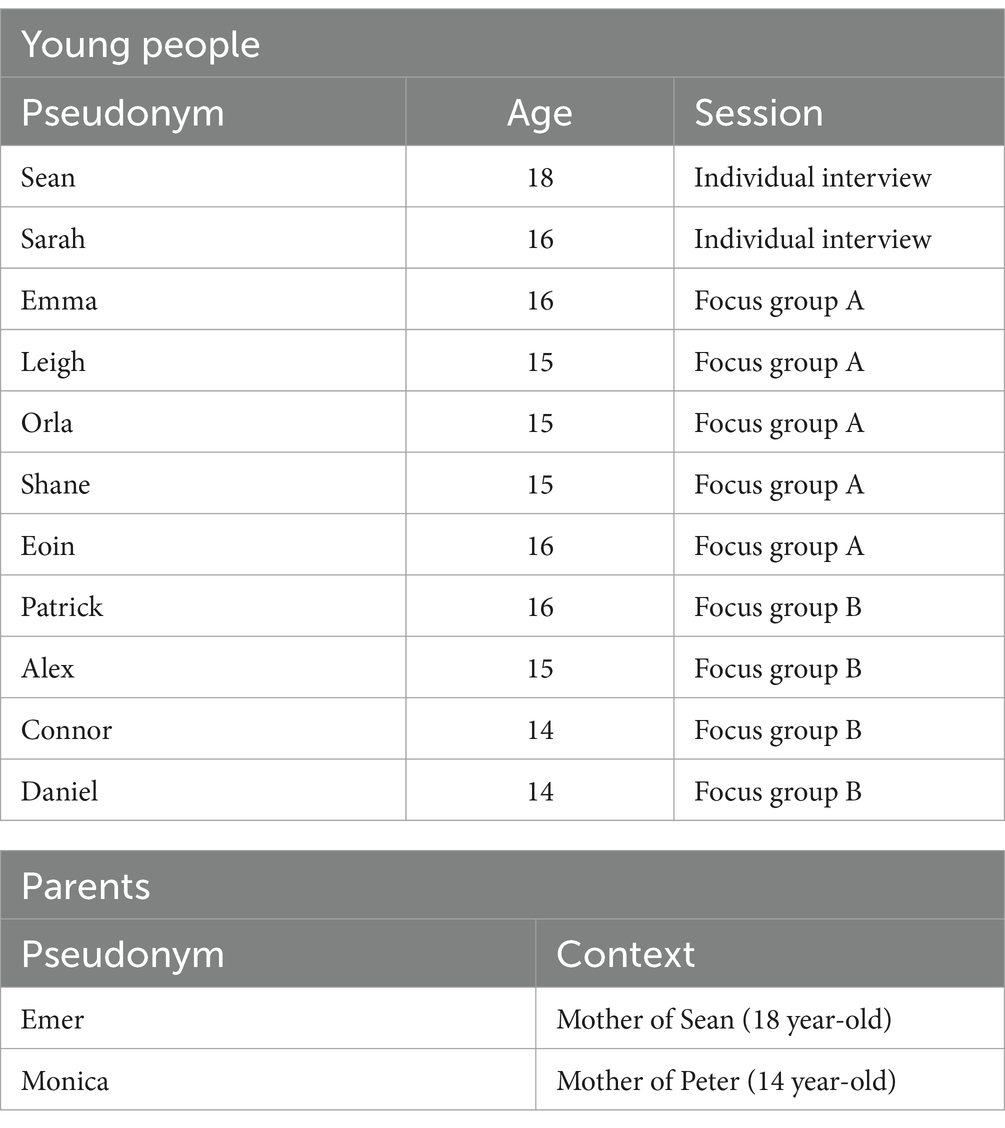

Gatekeepers in community services supported the recruitment of parents and young people. The gatekeepers were encouraged to invite individuals with lived experience of SAPs from a range of backgrounds, including minoritized groups. Given the sensitivity of the topic, they were advised not to invite those who were at the time of recruitment experiencing acute distress or mental health difficulties. As shown in Table 2, 11 young people participated, including a queer and transgender young person, boys from the Traveller community, a young person of color, young people with learning disabilities, a gifted and a neurodivergent young person. At the time of interview, seven of the eleven young people were availing of alternative education provision (home tuition or alternative education center) following significant and extended SAPs; the remaining four were currently experiencing SAPs and intermittently attending their mainstream school. Two parents, both mothers, participated. Each had a son with a long history of SAPs; one of whom was experiencing attendance difficulties at the time of interview, and another whose son had recently transitioned to an alternative education setting (Youthreach). One focus group with Traveller parents was canceled, which the gatekeeper attributed to a legitimate distrust in authority figures and/or research institutions.

2.2 Procedure

The data gathering method for the professional groups consisted of a series of online focus group interviews. Non-directive, semi-structured interviewing techniques were used to explore participants’ sense-making in relation to SAPs. Five focus groups, each lasting approximately 1 h, were conducted over the course of 2 days via Microsoft Teams. Focus group prompts centered on four themes: participants’ understanding of SAPs, experiences responding to SAPs (barriers and facilitators of success), the professional toll of school avoidance, and “blue sky thinking,” whereby participants were prompted to imagine possibilities and solutions.

With regard to the participation of young people and parents, all interviews took place in-person, in settings chosen by participants; these included local community centers, organizations in which young people were in receipt of services, and in participants’ homes. In the case of one mother who was interviewed at home, the gatekeeper who introduced us was present for her comfort. Some young people were comfortable being interviewed individually, while others who had established strong peer relationships preferred to be interviewed as a group (see Table 2).

Arts-based methods were used in the interviews/focus groups with young people. These methods included self-portraiture and body mapping. Self-portraiture is a projective technique that allows the young person to contain their inner experiences on paper (Berberian, 2017; Gerteisen, 2008) with the aim of encouraging reflexivity while thinking holistically about their identities and lives (Bagnoli, 2009). Self-portraiture invites introspection that allows participants to explore emotional and potentially triggering materials without pressure of finding accurate vocabulary to explain themselves. Similarly, body mapping facilitates embodied awareness (Dew et al., 2018) to allow participants access information and feelings relevant to certain situations that may be difficult to express verbally. Sensations of sadness, stress, anger, or frustration are held in the body and can be expressed through body mapping. Body mapping also allows researchers to guide participants into thoughtful, embodied communication in a safe and supportive space (Orchard, 2017).

Young people were given a choice between self-portraiture and body mapping. Both young people in individual interviews chose self-portraiture, while in one focus group, young people chose to do a group body-mapping exercise. A second group also chose body mapping, but ultimately did not feel comfortable having their art works shared; all however consented to the recording and transcription of sessions. These methods were used in conjunction with semi-structured interview questions centered on four themes: experiences of school, history with SAPs, what helped and hindered during their experiences, and blue-sky thinking around imagined solutions (similar to the focus groups with professionals and educators). The data gathering methods were intentionally flexible and reflexive in order to facilitate the needs and comfort levels of each participant or group. With regard to the two parents, both mothers, a semi-structured interview technique was used. In both cases, a timeline was created, which included their child’s experiences in school, factors precipitating SAPs, through to current day issues and reflections.

2.3 Analytic approach

We used Braun and Clarke’s (2019, 2023) reflective thematic analysis (RTA) approach, which embraces reflexivity, subjectivity and creativity as assets in knowledge production. As part of this RTA process, recordings were transcribed, and transcripts read and re-read by the second author (TC), which aided data familiarization and notes for early impressions. Then, initial codes were generated in the first phase of coding informed by (i) the data from young people, parents and professionals on issues related to SAPs, and (ii) the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of an ecological trauma-informed approach. Following this, transcripts were read by the first author (CoT), in line with the collaborative and reflexive data analysis approach advocated by Braun and Clarke (2023). This re-reading aimed to achieve richer interpretations of meaning, rather than attempting to achieve consensus of meaning. This collaboration led to theme refinement and finalization (Braun and Clarke, 2020). Data from the professionals was analyzed separately to the data from parents and young people. We did not attempt to triangulate the data as we anticipated that the views of parents/young people might diverge from those of professional groups. Participant excerpts have been assigned non-identifiable codes. Minor edits were made to excerpts to hide identifiable information and for clarification which is denoted by “[…].”

3 Findings

We first present the findings from the focus groups with professionals followed by findings from interviews with parents and young people.

3.1 Themes identified from professionals’ focus groups

3.1.1 “A perfect storm”: the conditions impacting school attendance problems

Participants felt that a complex array of factors were creating “a perfect storm” for increased SAPS. There was consensus that COVID-19 was a “common denominator, which resulted in an exponential increase in school attendance difficulties” (Educ J). Families that were struggling before COVID-19 were now struggling even more; and families that previously unaffected by attendance difficulties were faced with a new and foreign issue. A youth worker flagged that “COVID has done massive, massive damage to the young people.” Similarly, a family support worker stressed that, “this is unprecedented, this is everybody…This is across the board, everybody is affected…and I think that should frighten us in a way” (Prof 11). Some suggested that the school closures normalized staying home, while others suggested that a break in routine left many struggling to reintegrate into “work as usual.”

Participants believed that mental health difficulties had increased in volume and complexity since the pandemic. Anxiety was most often cited and frequently manifested physical symptoms, with some participants referencing students “actually physically being sick at the thought of going to school” (Educ F). In severe cases, levels of anxiety were such that attending school was not a realistic goal; instead setting a goal to get out of bed or engage with low-demand activities were prioritized.

The penetration of social media and technology in young people’s lives also created challenges. The upset and humiliation felt by young people who had images or recordings of them uploaded to social media, was considered a major factor in school avoidance, as the following quote highlights.

“I cannot stress enough the damage that smartphones are doing because as you know…I have so many young people for whom that’s the reason—one photograph went around the school 4 months ago and ‘I’m never coming back!’ They really, really feel the victims of this kind of bullying and every single aspect of their life being recorded…One of your eyelashes falls off, it makes Insta[gram], your life is over. You know that that’s the world they live in.” (Prof 7).

Others noted that gaming and constant access to streaming services, like Netflix, function as significant ‘pull factors’ incentivizing young people to remain at home. Watching videos and gaming into the night was highlighted as a reason young people had difficulty getting up for school in the morning. A school guidance counselor noted, “We have gamers who turn night into day, and so they are online gaming all night and then they are sleeping all day” (Educ N). It was acknowledged that limiting screen time was a challenge for parents, often resulting in power struggles. It was particularly difficult for parents who were not present in the home to supervise their children before or after school, due to work or other commitments.

In relation to young people’s home environments, some professionals felt that there was a “lack of control in the home” and that parents “have relinquished their parenting role” (Educ F.) There was a view that “homes are so nice now compared to what they were…when a teenager stays at home, they are in a lovely warm house, they have Wi-Fi all day long and they are on their device” (Educ G). However, there was also recognition of acute levels of adversity and trauma that some children and families were experiencing. Issues included homelessness, abuse, poverty, addiction, domestic violence, parental/sibling incarceration. For those living in very challenging, chaotic, or dangerous situations, it was acknowledged that school attendance was not the most pressing concern. The following quotes are illustrative of some of the challenges facing families:

“I had a family who had to go to a different [homeless hostel] every week for about a year. And the young person was on the autistic spectrum and that just did not suit him. So, you know, he was smashing up the room…and then they were not allowed back into [there] again. So, he was moving around. So obviously then he just wasn’t in a position… they were worn out and they were not in a position to go to school” (Prof 10).

“The condition that some people are living in, in this day and age in Ireland; it is absolutely appalling” (Educ L).

“They’ve just got so much chaos going on. School is that far down the pecking order, it may well be irrelevant” (Prof 12).

“When you know the situation the kids are coming from, it’s a bloody miracle they are in school” (Educ N).

Regarding school related factors impacting attendance, issues included aspects of the curriculum that could be triggering (e.g., physical education/sport), imbalances of power in relationships (e.g., conflict with teacher, peer victimization/bullying), transitions (e.g., transitioning from a relatively small primary school to the overwhelming busy-ness and relative anonymity of larger post-primary schools); insensitivity to student’s needs (e.g., a student with literacy difficulties being asked to read aloud in class; a student with sensory needs having to wear an uncomfortable uniform); and intense pressure for academic attainment. Students with learning difficulties and autism faced particular challenges in meeting the curriculum and coping with social expectations and sensory overload associated with busy school environments.

In addition, there was a belief that sometimes schools exclude young people by “turning a blind eye” to school attendance problems (Prof 12) or by subtly conveying to young people that they have “already been written-off” (Educ C); that school is not for them. It was also suggested that schools may not report all absenteeism, perhaps in an effort to maintain the school’s reputation (Educ D, Prof 12). This was a particular issue for Traveller students, an issue discussed further below.

Proceeding with the curriculum as normal in the aftermath of COVID-related school closures was viewed as problematic, because many young people have “taken a real shock to the system regarding where they are now academically…and it’s affecting brand new people that would never have come under our radar before” (Prof 7). Many of those that struggled academically before the pandemic, have fallen further behind; driving vulnerable young people further from school. It also appears that the problem is affecting younger students, with a rise in under 16 s experiencing SAPs. All these factors contribute to the school environment feeling unsafe, overwhelming, and trauma-inducing.

3.1.2 The rigidity of the education system

A recurring theme in focus groups was the perceived rigidity of the education system, which created barriers for to attendance for particular young people. Some concluded “that actually school does not suit everyone” (Prof 2). Another reflected, “[There is an] issue of square-peg-round-hole with our education system, it’s not fit for everyone. And so we are really feeling in the dark…and struggling to come up with the plan.” (Educ F). Similarly, a psychologist working in disability services, noted “I spend a lot of time trying to fit kids into schools, and I’d like the school to fit to the kid.” (Prof 4). She pointed out that for young people who “are not particularly academic…there aren’t a lot of options presented,” consequently, they can experience school as “boring” and “limiting.” She said that when you really listen to these young people, their concerns about attending school are “really valid.”

The rigidity of the system was also reflected in the challenges teachers encountered around covering the curriculum in a model that requires students to progress at the same pace and time. One post-primary school leader noted:

…you do not want to leave the child behind; but they show up one day a week and you have to backtrack that bit [of missed curriculum] for them; and then you are holding back the other children. So it’s real frustrating, it’s one of the most frustrating parts. I know for our own teachers, particularly in the [senior cycle] when they are preparing kids for the Leaving Cert (a high stakes examination that determine entry to university)… the other 24 kids who have been attending, they deserve to plow on. (Educ H).

Furthermore, it was noted that the educations system proffers a distinctly White, settled, middle class value system; one in which young people from minoritized and marginalized backgrounds may feel a sense of othering and exclusion. The following quote is illustrative:

There’s a value system here that we are trying to impose—our middle-class values, our expectations of what we had growing up; onto these kids who have got [for instance] siblings, parents in prison; they have got one parent who’s in addiction trying to rear them…that’s the reality of what I’ve experienced so far. (Educ C).

Similarly, Prof 4 pointed out that our education system is built for the neurotypical majority, and it is one in which accommodations for neurodivergent young people are not easily accessible.

There were strong and consistent calls for a more holistic approach in education and a re-evaluation of the purpose of education. A child psychologist questioned “why do we want kids to go to school in the first place, what do we want them to learn, like…?” She argued for the need to “look at school, re-evaluate, and change it completely” (Prof 2). Many professionals advocated for greater choice, voice and empowerment for children and young people: “I think empowerment is key…I would love to see more choice. I’d love to see young people have more options, more choice” (Prof 2).

3.1.3 Over-stretched and under-resourced

Timely access to tailored, specialized supports was a huge concern across focus groups, with systemic under-resourcing significantly straining individual relationships and leading to gaps in understanding students’ needs. One psychologist estimated that she has around 700 children on her caseload (Prof 4), which inevitably meant that children were falling through the cracks. A youth worker referenced a first-year student who had only attended school on 9 days between September and January “and she never came under the radar of anybody” (Prof 7). School principals reported that there is limited number of psychoeducational assessments that they can request, and this allocation was grossly inadequate. One participant felt that Traveller students in particular “fall through the cracks…because other people are prioritized” for these assessments (Prof 12).

Practitioners felt that long wait times for access to services contributed to disillusionment and distrust. A family support worker noted that the Traveller families she worked with, were “all trying their best to get them [young people] in and they are trying to access services and there’s no appointments or appointments aren’t coming up for ages…they could be waiting months” (Prof 8). It was noted that some Traveller students would prefer to attend segregated Traveller schooling; however, the number of places available were extremely limited. The prospect of attending mainstream school—and the bullying that was anticipated there—acted as a huge disincentive to continuing education.

Professionals were cognizant of the importance of investing in relationships, providing one-to-one personal time and wrap-around, multi-agency support. However, they felt there was insufficient staff or “manpower” to support and sustain these approaches. One Home-School Liaison Coordinator (HSCL) noted: “we are talking about a handful of families that I worked intensively with… I probably missed another 20 [students] in the school” (Educ E).

There was a sense that resource gaps were impacting professionals’ wellbeing. For instance, school principals raised the difficult ethical dilemma they face due to having, for instance, “only two psychoeducational assessments for a student population of over 600—who do you prioritse?” (Educ H). For another school leader, working within the constraint of the system led to feelings of “disappointment, frustration and upset, and almost feeling like as a school we did something wrong and wondering is there anything else we can do?” (Educ H). Knowledge gaps, likely exacerbated by siloed ways of working in education, were also impacting professional wellbeing; a HSLC who understood the complexity of young people’s lives outside of school, felt her school-based colleagues did not understand, leaving her feeling isolated and frustrated in her role;

“I just sometimes feel that I have a completely different set of eyes to my colleagues…and that can be very frustrating, and I can feel very alone in my work as a result” (Educ C).

Another professional who works with and advocates for marginalized young people was evidently frustrated: “I’m saying the same thing every single year for the last 10 years. Nothing is changing” (Prof 12).

3.1.4 Lessons learned around what works

Participants offered insights into what worked well in supporting young people experiencing SAPs. Positive relationships that foster a sense of trust and safety were considered central across all focus groups:

“using the relationship…it’s our greatest asset. It’s our best tool and it’s something that is proven to work” (Prof 12).

Getting to know the young person allowed a deeper understanding of their unique strengths and difficulties and facilitated bespoke responses. Examples included, understanding a young person’s worry about revealing self-harm marks in physical education classes; allowing a young person to wear a hoody (with hood up) to reduce sensory overwhelm; giving permission for a young person to leave class when feeling overwhelmed or unsafe (having a note in their journal, to this effect).

School nurture groups and the check-and-connect approach were mentioned positively as ways of fostering relationships and belonging. Within nurture group, young people came together in the morning before class, “they might have tea and toast, play games…have chats with the teacher, build relationships really, with the teacher and the SNAs and with the other boys within the group. And…it was just making them feel safe and secure and building that relationship of trust with the people” (Educ G).

Interagency collaboration was highly valued as a way of addressing the multiple influences associated with school attendance problems, and ensuring professionals were working toward a common goal: “The most effective cases have been where there’s effective co-working in place…we are all singing from the same hymn sheet” (Prof 3). The Meitheal approach, a process and structure used in Ireland to support inter-agency collaboration, was praised several times for facilitating the sharing of expertise, knowledge and skills to meet the needs of children and families.

There was consensus that flexibility in educational provision was needed in responding to students with SAPs. The options discussed included adjusting educational tasks, offering out-of-school/alternative educational provision, and further resourcing and/or expansion of existing supports that were perceived to work well, but are currently only available in designated disadvantaged schools (i.e., the Home-School Liaison Scheme, and the School Completion Programme). Given the complexity of SAPs, it was deemed important to have a wide range of alternative options, as participants recognized “one-size would not fit all.”

Reduced timetabling is an example of an adaptation to the school context, which was frequently mentioned, but was more controversial than other solutions. Some professionals felt strongly that reduced timetables were counterproductive, that they facilitated and maintained patterns of school absenteeism; or worse, that they were used to exclude particular young people, especially those “presenting with behaviors of concern that maybe are difficult to manage in school” (Prof 4). One youth diversion worker disclosed that Traveller children have been greatly affected by this form of school exclusion (Prof 12). However, others found reduced timetables helpful when used as part of a phased plan toward increased attendance: “we do find bringing them back, a reduced introduction and reduced timetable helps. So, start them on mornings for a week, after lunchtime the following week, full day the following week” (Educ H).

3.2 Themes identified from parents and young people interviews

3.2.1 You’re not welcome here, and also, you are not allowed leave

There was a distinct sense among all young people, that they felt unwelcome in their mainstream schools. All reported negative and conflictual relationships with school staff. They often felt that “nobody cared” (Shane). If they were relatively quiet or introverted, they tended to feel “ignored” and invisible (Eoin). If they were more vocal, they were typically labeled “bold” (Emma). Some young people felt “picked-on” by school staff, (Leigh) and even “hated” (Orla). They felt they were treated unfairly and sometimes blamed for things that were not their fault.

Given their family or working-class backgrounds, some young people felt they did not belong in school and that they were not expected to succeed. Eoin disclosed that: “It just felt like I did not fit in there. Just everyone coming round in big fancy cars, talking about their fathers being doctors and their mothers being doctors. Nah, being from this area they look at you different.” Comparison to past family members who attended the same school was an issue for many young people, who felt that their family background affected how teachers interacted with them. Eoin felt that he was being judged and treated unfairly based on the actions of his father a generation ago: “Everyone is different. Alright, my father did something in the school 20 years ago, I’m a different generation to him, it’s not like I’m going to act the same…” Another participant had a teacher call him by his older brother’s name, even after correction. His older brother had been lured into crime and had a “bad reputation.” That his teachers could not see that he was a different person to his brother, affected him deeply. These kinds of experiences meant that school became a place of shame, alienation, and rejection. In addition, many of the young people had experience of being placed on reduced timetables, in-school detentions, suspensions, and expulsions. There was a clear sense among the young people in Focus Group A, that they had been pushed out of school, long before they made the conscious decision to stop attending. Eoin recalls,

“Every day I went to school I was in the office, the whole day [the Principal] just left me in there… so I just got sick of it, I went back in and done my Junior Cert. [a formal state examination] and told them I was leaving.”

Despite these very negative experiences, when students voiced a desire to leave school and avail of alternative provision, they were often met with resistance. Sarah struggled for years with anxiety which culminated in feelings of suicidality (see more on Sarah’s story in the section Fighting for my Life, below). Ultimately, she felt her best option was home tuition, but she faced with considerable resistance:

“I begged them to let me go home schooling because I was in a deep state. They kept refusing, they were like ‘no!’… I sent a personal email to the school. Like, ‘hey, listen, I need to be home schooled. You know, I’m doing horribly’. I think it’s unfair how we are treating as if being home schooled is not an option. Like, just because of their own personal opinion, you know.”

Some young people highlighted that it was only when they requested release forms to attend alternative settings, that they were offered additional resources, which had not been suggested previously. For Orla, it felt too little too late:

“When I was leaving the other school they would not leave me go, they would not give my mum the form for me to go, so my mother had to go in every day and try to get it… all they kept saying was, ‘stay in school a bit longer, we can get you help’ and I said ‘no’, and then they brought me in for a meeting…they said, ‘we’ll get help for you’ and stuff and I said ‘no, I just wanna get out of here’. The principal was trying to force me to stay in the school.”

Overall, the young people we spoke to had very negative experiences of schooling; they felt unwanted within their school, yet trapped in them, because the system was reluctant to offer alternatives or cater to their additional needs.

3.2.2 Fighting for my life—disability and mental health

We spoke to Sarah, a 16-year-old, about her struggles with school attendance which began in primary school: “so fifth class rolled around and that’s when, it’s like there was a lot of work and responsibility, so I started to get really stressed.” She explains that she started feeling extremely anxious and had severe difficulty sleeping at night, she would often find herself drowsy or falling asleep during class. She recalls, “when I was ten, eleven, like, Jesus Christ. Back then my anxiety was awful, like, Jesus, oh boy. You know…more flashbacks just thinking about it!.”

Her struggles intensified when she started post-primary school: “then, oh man, when I went to secondary school, that’s when everything hit the fan. I started to miss so many days off school, like, I’d literally go in once or twice a week.” Interactions with some teachers were anxiety-provoking. She revealed that there were teachers “who do not vibe with you…I do not want to come face to face with [them], especially if they are the type to shout or, like, be really, really strict and stuff like that…it makes me a lot more scared.”

Sarah was assessed by Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and received several diagnoses. She describes herself as Autistic and reveals she has anxiety disorders and executive disfunction. She started on medication, but then:

depression hit, really bad depression, and throughout the months it got worse, really, really bad. To a point where, like, almost there would not be a day where I would not go without thinking about suicide. Like, trying to be as honest as I can…I genuinely believed that life had nothing left to offer me, and that, you know, I had no reason to be here whatsoever. It was truly a dark moment for me and that really impacted my ability to go to school even further.

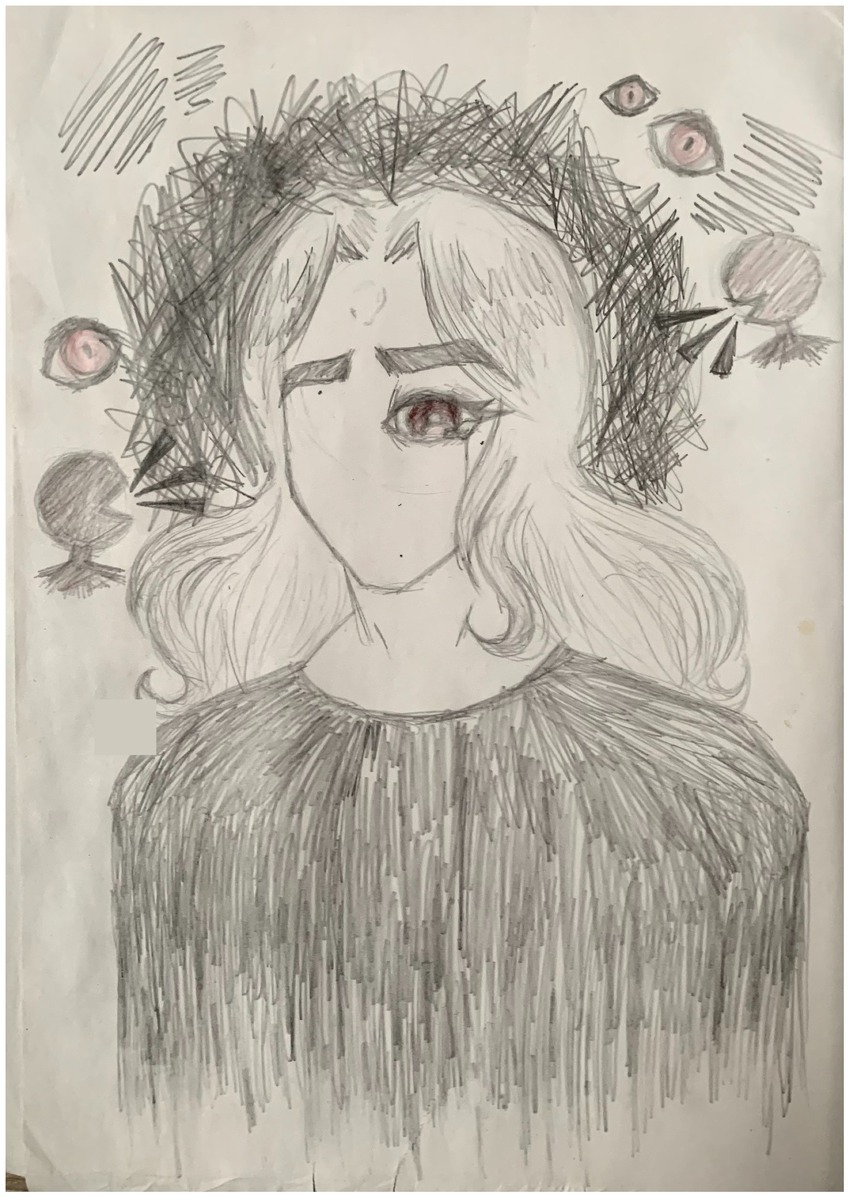

Sarah drew a self-portrait capturing her experiences of SAPs during this time (see Figure 1). The red eyes, which can be seen surrounding her head, symbolize the intense gaze and judgment of others. The talking mouths represent people whispering, a reminder of the bullying she endured. Fuzz and chaos surround her head, providing a visual illustration of how she was feeling, which she cannot fully verbalize to herself or to anyone else.

After starting home tuition, Sarah began to do research into her diagnoses, and she says, “I’ve gotten to discover myself a lot more.” For instance, she now understands why the transition to secondary school was so difficult, “how overwhelming it was, like, sensory-wise, because it’s like people talking, pushing around.” However, she has also realized that having this knowledge “did not help with school [attendance]. Even though it’s like, okay, I’m Autistic I can get more support, the anxiety about school was still very much there, and it was still very much strong.” At the point of her diagnoses, after long wait times during COVID-19, Sarah had already struggled with sensory issues, executive dysfunction, anxiety and bullying for several years.

Sarah fought to be granted home tuition. She describes this as, “legit fighting for my life.” It was a long process, convincing authorities that this was the right decision for her and getting all the forms and signatures required, but she and her mother persevered. With home tuition, Sarah says:

“I was able to still get my education in a more comfortable way if that makes sense. I was able to get my education at home or in the library, no large amounts of work. No large amounts of homework. No shitty people to deal with, no shitty teachers to deal with. Like nobody yapping in my ears. Just peace and also just getting bits of education done.”

Receiving home tuition also provided the time and space she needed to process her diagnoses and gain self-knowledge and understanding:

“…throughout the year that I’ve been home-schooled, you know, it’s really given me the chance to discover more about myself, you know, my boundaries, whatever. How to cope with things, you know. Like really assure myself that hey, you know, it’s like you can do this now.”

Home tuition offered aspects of primary school that she had enjoyed: a quieter environment, the same tutor each time, and more personalized approach to learning. Sarah says she is “in a much better place now,” that her “mental health is much better.” During the interview, Sarah revealed that she was in the process of planning a return to mainstream school and at the time of writing this report, Sarah has done so. She says “its my own decision, I was not pressurized…I was kind of considering it and I was thinking, you know, ‘going back to my school would not be a bad idea. I’d be the same as my friends’”. Her plan is to finish school and then apply to art college.

3.2.3 “I was broken”: the realities of parenting a child with school attendance problems

Monica is the mother of Peter, a 14-year-old-boy, with a long history of school absenteeism. Monica has older adult children and her parents live nearby. She has experienced housing insecurity; she recalls, “there was hassle in the last house I was living in we had to leave so… we ended up going up into a [homeless] hub and we were up there for 9 months.” She wonders if this might have affected Peter more than she realized at the time. Monica has huge concern for Peter’s safety. There have been violent incidents in her community and Peter has been targeted. Peter tells her, “I go to school and there could be a few of them outside the school waiting for me.” Monica says, “his whole childhood has been kind of that, you know, from pre-school up, he’s been bullied his whole entire time in school…They target him from day one.”

Peter is now experiencing what Monica thinks are panic attacks, which are terrifying for both of them:

“…he said it’s like he feels he knows he’s here, but he’s out of his body. And he was snow white in the face. But I kind of kept him calm, do you know. Kept talking to him…I had him in there in the sitting room. My nerves! Checking to see if he was breathing and everything!”.

When he was in primary school, Peter would sometimes run away, leaving the school grounds, precipitating many anxious trips to town to look for him, as well as stressful phone calls with the school. Monica felt that the school did not understand that his behavioral issues were connected to the bullying he was experiencing.

“Oh they often seen it happening, pulling chairs, firing things at him… but it was always Peter that was sent home. Peter was always the child that was sent home, and I had [enough of] it!

Peter was placed on a reduced timetable in primary school. This impacted his academic development. Monica considers, “I suppose we kind of feel about how much primary school he missed that he kind of fell behind academically.” She has huge regrets about this:

“You see, I was very quiet, and I was going by what primary [school] were doing with his reduced timetable, do you know. So, I said, ‘Well, that’s the way it is’. But I was sorry now, I have regrets over that now like, I should have stood up and said ‘no’.”

Peter is now in first year in secondary school, but he rarely attends. He has experienced sustained school attendance problems for 2 years. He’s not eligible to apply to attend alternative provision (Youthreach) until he is 16 years old (which is 2 years away), and Monica is worried about what he will do between now and then. She fears that her son could either become further victimized by violence in her neighborhood, or could be drawn into criminality while not in school. She has become worried about letting him leave the house alone.

“…I know he’s not going to stay up in his room [all day] either. That’s my main worry. We’d love him to go back to school obviously. He needs his education, but I cannot really see that happening, do you know. I wish he was sixteen and he could get into a new place, like in Youthreach.”

Regarding her contact with schools, Monica says, “I’d be getting hyper and the blood pressure would be through the roof.” She admits, I had a lot of run-ins with them in primary. However, she feels that she done everything she could to support her son’s attendance: “I feel like, I do not think there’s any more I could do. No. Like we have tried everything,” but she is still afraid that “I’m going to get into trouble” with the law or with Tusla [child protection service]. Despite the turmoil, she feels that she has maintained “a pretty strong relationship” with Peter.

A second mother, Emer, lives with her son, Sean; it is just the two of them at home. From the time Sean started school, Emer says he was “resistant.” She confides:

“I thought I was doing all the wrong things. And I thought, ‘why is he like that? Why is he, was he, so resistant’, you know, the intensity of his resistance…It wasn’t like we gave up easy or anything. No, it was really hard. I could not really understand it.”

More recently, Sean has met the criteria for several diagnoses; he has sensory issues, an atypical cognitive profile, and can struggle in social situations. Emer’s efforts to keep Sean in school negatively impacted their relationship and their wellbeing: “I can only say I was broken. You know, I was just, I had nothing left in my arsenal, and I was exhausted. He was exhausted. Our relationship wasn’t good.”

Emer felt judgment from others, who thought she was “too soft” on her son. However, reflecting on the struggles she says: “You know in hindsight, I would have taken him out [of school] earlier, because it was just silly. Actually, it was like hurting yourself. It was horrible. And no good came out of it. It was really painful.” Sean, in a separate interview, offers the same reflection, wishing he had left school earlier given how much he suffered in that environment. Emer recalls a meeting with his school, where she explained:

“This has become diabolical, for me and for him. I asked school staff, ‘what can we do?’ Because he’s not going to get to the Leaving Cert. [exam]. He′s not going to do it…we just have to do something different, this is not working’. And they were all pushing the Leaving Cert., ‘only another year, na na na’.”

Sean is now attending an alternative education setting and is getting on well. Emer says, “it has been fantastic…I felt relief and hope…I see him decompressing, and I see the flickers of joy, and moments of, you know, laughter…Yeah, he’s coming back into something, which was really gone.” Sean confides that he likes “the smaller class sizes” and that it is “more easy to access the teacher because there’s less people.” Emer and Sean’s relationship is now improving, Emer reflects, “it’s been healing, you know? Yeah, the pressure has been taken out of the thing. And now we can all come back to some sort of equilibrium. You know, it’s not perfect, but it’s workable…it’s way better.”

3.2.4 Envisaging a better education system

In group conversation, young people discussed their experiences of school life. Focus group B consisted of Traveller boys who all attended mainstream secondary school, but their attendance was erratic. They spoke about their relationships with teachers, which were sometimes conflictual: “when I walk into the class he [the teacher] comes straight for me.” Nevertheless, in imagining their ideal school, the boys envisaged some of their existing mainstream teachers or youth workers, including their principal, because “he’s sound, he knows what he’s doing. He’s smart.” They also spoke about school facilities (boxing ring, pool hall), subject choices (engineering, math, history, Irish), and school schedules (later start times) that would make school more appealing for them. Despite, entrenched view that ‘Travellers do not care about education’, the boys clearly had views on school, and valued the relationships with school staff.

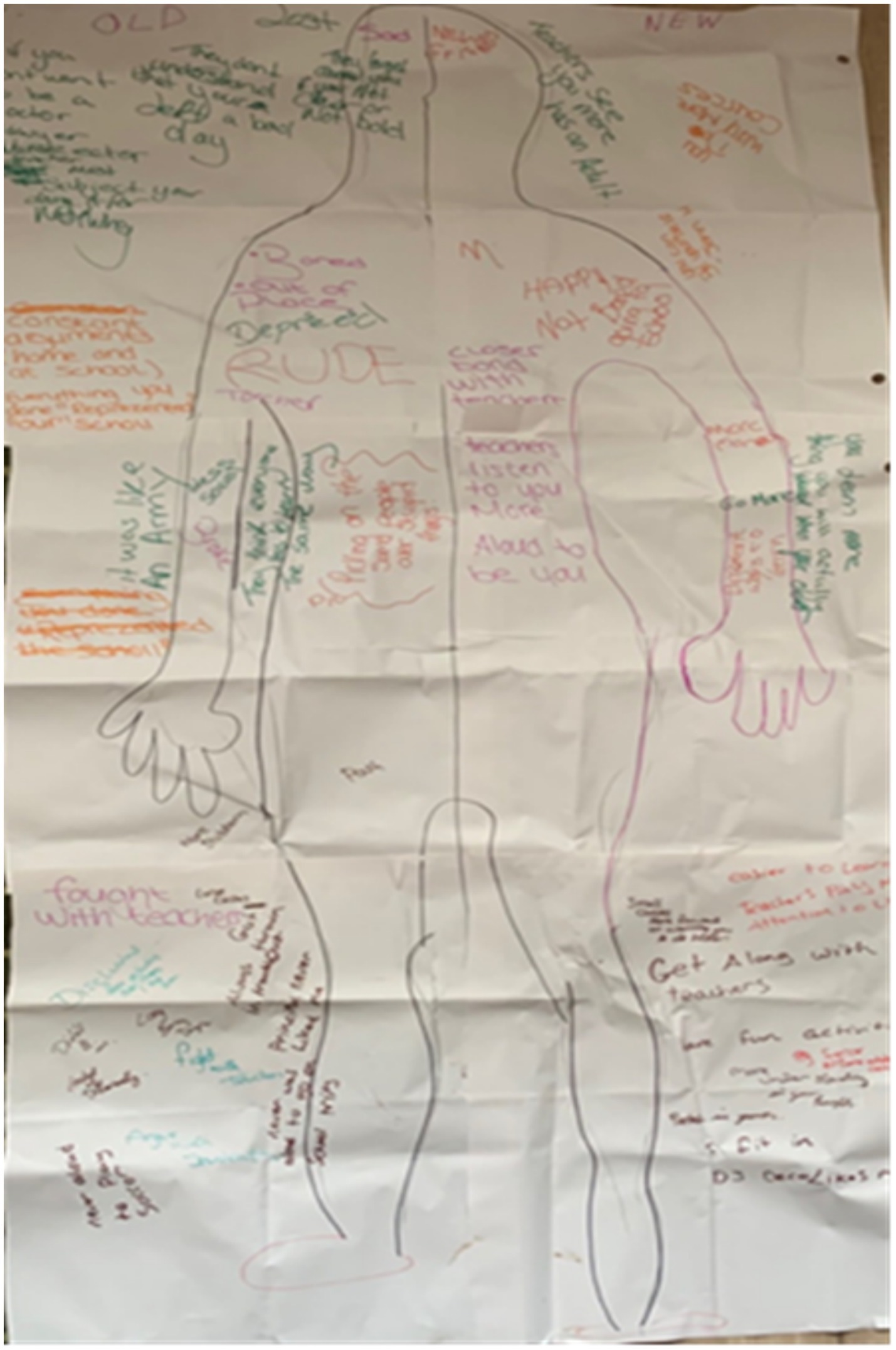

Another group of seven young people discussed their prior experiences of mainstream schooling and current experiences attending alternative education settings. Using a body mapping exercise, they reflected on how these settings made them feel. In their collective body map, shown in Figure 2, the left side of the body represents their previous secondary schools. “Rude” is written in large letters, reflecting how one girl felt she was treated. “Depressed, out of place,” come next. “Principal never liked me” is drawn down a leg. “They forgot about you” above the head. One boy writes, “more stubborn,” explaining how he acted at his old school. The young people were upset at how they feel they were treated, and some emotions bubbled to the surface.

Figure 2. Young people experience of what school feels like for them—left side of body represents experiences of mainstream secondary school; the right side reflects alternative education settings.

The right side of the body reflected their current alternative education settings. A young person writes, “You learn more,” another “Easier to learn, small class sizes.” One girl writes, “I fit in. ‘Aloud (sic. allowed) to be you.” The word, “Happy” sits on one shoulder. As they wrote and debated back and forth, they recounted stories of how they get to do more activities, go on excursions, and take courses that align with their interests. It is evident from their discussions that they have a renewed sense of self-confidence and hope for the future. None of them claimed to have perfect attendance in their alternative setting, but they all attested to a new-found interest in education, feeling better about themselves, and enjoying their relationships with teachers who treat them well.

4 Discussion

The findings of this study echo previous research which suggest that children and young people are growing up in an increasingly complex world, many aspects of which (technology, gaming, social media, high stakes examinations) are adding to everyday pressures and impacting school attendance (Gubbels et al., 2019; Melvin et al., 2019; Thambirajah et al., 2008). They also show that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these difficulties, creating a “perfect storm” for increased SAPs. The pandemic may have altered cultural expectations around school attendance in ways that are yet to be fully understood.

While any child can experience SAPs, this study noted certain groups are more likely to experience barriers to attendance. These include children from the ethnic minority Traveller community, neurodivergent and trauma-affected young people, those with mental health difficulties, special educational needs, and those from working class backgrounds. The barriers for these groups included experiencing difficult and unequal relationships, feeling disrespected by school staff, being bullied, feeling psychologically or physically unsafe, experiencing sensory overwhelm and difficult transitions, not being able to meet academic or behavioral expectations, and not fitting in.

For many young people the challenges were considerable; for instance, young people in this study felt that attending school placed them at risk of suicide, physical assault, and discrimination. While the benefits of schooling are well-documented, international evidence also points to a harsh reality that schooling can be extremely distressing and trauma-inducing for some students (Duane, 2023; Hansen et al., 2022; Powell, 2020). Recognizing that school can be a source of distress is an important first step in addressing SAPs. For many of the young people we spoke to, absence could be considered a solution, rather than a problem. Non-attendance was a reasonable and intelligible strategy to maintain physical or psychological safety. Hence, addressing non-attendance means taking seriously the barriers that young people face and developing a holistic and integrative picture of their unique situations (O’Toole and Devenney, 2020). This means actively listening to and young people and giving them more say in interventions or support plans.

Parents face a considerable challenge in the face of SAPs. The findings of this study revealed that some professionals believed that parents lacked capacity in their parenting role or that they are not sufficiently motivated to ensure attendance. Others offered more complex accounts, highlighting the pressures, stresses and (often intergenerational) inequalities that may account for parents feeling ambivalent about schooling. The parents who participated in this study, spoke of how attending school was negatively impacting their child’s wellbeing. They felt intense judgment from professionals (e.g., that they were too lenient or lacked parenting skills), which was also reflected in the expressed opinions of some professionals in the focus groups. These parents were caught in a difficult dilemma: Should they ignore their parental instinct, risk damaging their relationship with their child in order to enforce attendance, or should they listen to their child and their own intuition, and risk being judged complicit, neglectful, and potentially face prosecution for non-attendance? This is a dilemma facing many families both in Ireland and internationally (Devenney, 2021; Morgan and Costello, 2023). Navigating this dilemma is made more difficult in light of rising concerns about youth mental health difficulties, particularly for marginalized families (e.g., Irish Travellers) who face an even bigger crisis in youth mental health and suicide (AITHS, 2010). All this cautions against simplistic and blanket assumptions about parental attitudes, values and behaviors.

For many young people and their families, alternative education, including, Youthreach, iScoil (a blended learning model), and home tuition, was perceived as the only credible option in safeguarding children’s right to education and offering a more personalized educational experience. The mainstream education system was deemed too rigid and inflexible, valuing academic attainment and rule following above all else. Yet the alternative education pathways currently available in Ireland have limited capacity, restrictive age-related criteria, and are unlikely to address the needs of all those experiencing SAPs. Moreover, there is concern that alternative pathways could create segregating practices that may be detrimental to the long-term educational outcomes of learners (Heyne et al., 2024). Thus, while acknowledging the vital role of alternative provision, much more emphasis needs to be placed on creating truly inclusive school environments in which all young people can flourish, including those who experience SAPs. This finding is supported by Garcia-Gracia and Valls (2023) who found that educations systems that are underpinned by a more inclusive model, reported less absenteeism.

The lessons learned from this study about how to respond to SAPs correspond with themes identified in other literature (Heyne et al., 2021; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; McKay-Brown et al., 2019). They point to the importance of forging strong relationships characterized by compassion, trust and mutuality, at all levels (between children/young people, parents/carers, colleagues, staff in other organizations). However, it must be recognized that developing and sustaining relationships can be difficult for professionals working with children and families who have experienced trauma, discrimination and oppression (O’Toole, 2022; O’Toole, 2022). Trauma-informed practices underpinned by core principles of safety, trust, empowerment, collaboration, and cultural humility have been found to support relationship building with children and families in diverse educational settings (Bellamy et al., 2022; Wilson Ching and Berger, 2024).

A whole-school, multi-tiered or continuum of support model is essential to facilitate a proactive approach that builds an inclusive school climate in which every student feels valued, safe and engaged (Tier 1). Targeted interventions (Tiers 2–3) for emerging or sustained attendance problems require individualized supports and reasonable accommodations, such as adaptations to the curriculum and/or adjustments to the social and physical environment (e.g., staggered entry time, adjustments to manage sensory overload). These need to be adequately resourced and monitored (Kearney and Graczyk, 2022; McKay-Brown et al., 2019).

Aligning with international good practice, professionals in this study valued interagency collaboration and supported co-designing interventions with children and families. It was acknowledged that the process of co-design takes time and effort but leads to increased ownership and better outcomes. It was also recognized that interventions need to be flexible and create movement toward re-engagement with learning and social connections, rather than stagnation (Heyne et al., 2021). For instance, a reduced timetable may be used to facilitate a graduated re-integration, where agreed between school, child, parents and Special Educational Needs Organiser (SENO) or psychologist, but should not be used without a plan for how gaps in learning will be addressed.

This study highlights that a proactive approach is needed to understand and address the barrier experienced by groups disproportionately affected by absenteeism. As noted in the Introduction, attendance, retention and progression figures for the ethnic minority Irish Traveller community are particularly stark. Echoing previous research, participants in this study highlighted several concerns, including the use of reduced timetables, a practice of not prioritizing Traveller children for psychoeducational assessments (despite evident need), a culture of low expectations, a view that Travellers do not care about education, and a practice of turning a “blind eye” to absenteeism. This amounted to what one professional referred to as “state-enabled school avoidance.” Nevertheless, many of the Traveller boys consulted as part of the study expressed educational goals and future career aspirations. Moreover, previous studies provide insight into reasons that Traveller community might feel ambivalent toward schooling. Given how they themselves were treated in school, Traveller parents may find it difficult to advocate or be involved in their child’s school (Quinlan, 2021). Traveller parents worry for their children’s wellbeing due to bullying and mistreatment, and they are painfully aware that even if their child succeeds in school, they are often unlikely to secure employment due to discrimination in wider society (Quinlan, 2021). This study, therefore, reinforces the need to address the significant structural barriers and intergenerational trauma faced by Traveller children in education with a culturally-responsive approach. This is echoed in international studies focused on the attendance, engagement and retention of other indigenous and First Nations students (Holmes et al., 2024; Rogers and Aglukark, 2024).

Although the findings and implications of this study dovetail with previous literature, translating them into practice is not easy or straightforward. Developing a cohesive, community-wide, and equitable response to SAPs requires time, space, and resources for interagency collaboration (e.g., school staff liaising with other professionals and agencies, monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions, and most importantly being available to collaborate with children and families). It also requires time and space for reflective practice, so that practitioners can become more effective agents of change with a deep understanding of how their actions, beliefs, values and biases impact both themselves and the communities they serve.

Unfortunately, school staff and professionals across other relevant agencies reported feeling under considerable pressure in their professional roles. Nevertheless, professionals in this study demonstrated a strong commitment toward meeting the needs of children, young people and families, and working collaboratively toward this common goal. A commitment to addressing SAPs, demands more than just launching a national school attendance campaign, gathering and tracking data; it requires allocation of funding and resources to enable professionals to effectively fulfill their roles. It also demands that wider systemic barriers to attendance and engagement are adequately addressed. Furthermore, working with SAPs can be emotionally challenging for professionals and lead to relationship ruptures (Devenney and O'Toole, 2021; Finning et al., 2018). To protect against compassion fatigue and burnout, professionals will need systemic supports for their own wellbeing, including for instance, creating opportunity for reflective practice conversations, access to professional supervision, and supportive and encouraging leadership, both within their organizations and from central state departments (O’Toole and Dobutowitsch, 2023).

In conclusion, grappling with the complexities of SAPs underscores the pressing need for innovative responses in education. While these challenges may seem daunting, they also serve as catalysts for transformative change. In our rapidly evolving world, where traditional approaches may no longer suffice, there lies a unique opportunity to reimagine educational practices in ways that better resonate with the diverse needs of today’s learners. By embracing innovative approaches, fostering community partnerships, and prioritizing individualized support, we can create inclusive school environments that inspire engagement and enable all students to flourish. Embracing these opportunities will not only enhance student well-being and academic success but also contribute to the broader goal of creating equitable and accessible education systems for future generations. Thus, while the journey ahead may be challenging, it is also rich with potential for meaningful and lasting impact on the educational landscape.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Maynooth University Social Research Ethics sub-committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CO’T: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this study was secured from Limerick Children and Young People’s Services Committee (CYPSC), awarded to the authors. The funding body supported our access to participants via gatekeepers in community organizations but had no role in data collection or analyses. Publication of this article was supported by the National University of Ireland Grant towards Scholarly Publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our community partners, Limerick (CYPSC) and Southill Hub, gatekeepers in community services, and all the participants (young people, parents and practitioners) who engaged with this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AITHS (2010). “All Ireland Traveller health study” in Our Geels. Summary of findings (Dublin: UCD School of Public Health and Population Science). Available at: https://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/AITHS_SUMMARY.pdf

Bagnoli, A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: the use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 9, 547–570. doi: 10.1177/1468794109343625

Bellamy, T., Krishnamoorthy, G., Ayre, K., Berger, E., Machin, T., and Rees, B. E. (2022). Trauma-informed school programming: a partnership approach to culturally responsive behavior support. Sustain. For. 14:3997. doi: 10.3390/su14073997

Berberian, M. (2017). Standing tall: Students showcase resiliency through body tracings. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 30, 88–93. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2017.1375734

Bethell, C. D., Newacheck, P., Hawes, E., and Halfon, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Aff. 33, 2106–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914

Blodgett, C., and Lanigan, J. D. (2018). The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 137–146. doi: 10.1037/spq0000256

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport, Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(come)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 24, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. (1998). “The ecology of developmental process” in Handbook of child psychology. eds. W. Damon and R. M. Lerner, vol. 1 (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 993–1028.

Childs, J., and Grooms, A. (2017). “Reducing chronic absenteeism and promoting school success” in Improving educational outcomes of vulnerable children. eds. L. D. Beachum and F. E. Obiakor (Plural Publishing).

Childs, J., and Lofton, R. (2021). Masking attendance: how education policy distracts from the wicked problem(s) of chronic absenteeism. Educ. Policy 35, 213–234. doi: 10.1177/0895904820986771

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., and McCoy, S. (2008). Acting up or opting out? Truancy in Irish secondary schools. Educ. Rev. 60, 359–373. doi: 10.1080/00131910802393399

Denner, S., and Cosgrove, J. (2020). School attendance data primary and post-primary schools and student absence reports primary and post-primary schools 2017/18. Analysis and report to the child and family agency. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

Department of Justice and Equality (2017). National Traveller and Roma Inclusion Strategy 2017-2021. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/c83a7d-national-traveller-and-roma-inclusion-strategy-2017-2021/

Devenney, R. (2021). Exploring perspectives of school refusal in second-level education in Ireland (publication number 29176628). [Ph.D., National University of Ireland, Maynooth (Ireland)]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses and ProQuest one academic, Ann Arbor.

Devenney, R., and O'Toole, C. (2021). ‘What kind of education system are we offering’: the views of education professionals on school refusal. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 10, 27–47. doi: 10.17583/ijep.2021.7304

Dew, A., Smith, L., Collings, S., and Dillon Savage, I. (2018). Complexity embodied: Using body mapping to understand complex support needs. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 19. doi: 10.17169/fqs-19.2.2929

Duane, A. (2023). School-based trauma: a scoping review. J. Trauma Stud. Educ. 2, 102–124. doi: 10.32674/jtse.v2i2.3870

Finning, K., Harvey, K., Moore, D., Ford, T., Davis, B., and Waite, P. (2018). Secondary school educational practitioners’ experiences of school attendance problems and interventions to address them: a qualitative study. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 23, 213–225. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2017.1414442

Fuchs, T. (2017). Intercorporeality and interaffectivity. Phenomenol. Mind 11, 194–209. doi: 10.13128/Phe_Mi-20119

Garcia-Gracia, M., and Valls, O. (2023). School absenteeism, emotional engagement and school organisation: an international comparative approach. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2023.2266722

Gerteisen, J. (2008). Monsters, monkeys, & mandalas: art therapy with children experiencing the effects of trauma and fetal alcohol spectrum disoder (FASD). Art Therapy, 25, 90–93. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129409

Goleman, D., and Senge, P. (2014). The triple focus: A new approach to education. Florence: More Than Sound.

Gubbels, J., van der Put, C. E., and Assink, M. (2019). Risk factors for school absenteeism and dropout: a Meta-analytic review. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 1637–1667. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01072-5

Hansen, B., Sabia, J. J., and Schaller, J. (2022). In-person schooling and youth suicide: Evidence from school calendars and pandemic school closures (No. w30795). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Harris, M., and Fallot, R. D. (Eds.) (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey Bass/Wiley.

Herrmann, L., Nielsen, B. L., and Aguilar-Raab, C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on interpersonal aspects in elementary school. Front. Educ. 6:635180. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.635180

Heyne, D., Brouwer-Borghuis, M., Vermue, J., van Helvoirt, C., and Aerts, G. J. W. (2021). Knowing what works: A roadmap for school refusal interventions based on the views of stakeholders. NRO Nationaal Regieorgaan Onderwijsonderzoek. Netherlands Initiative for Education Research. Available at: https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/media-files/Eindrapport%20Knowing%20what%20works%20%28nov.%202021%29.pdf

Heyne, D., Gentle-Genitty, C., Melvin, G., Keppens, G., O'Toole, C., and McKay-Brown, L. (2024). Embracing change: from recalibration to radical overhaul for the field of school attendance. Front. Educ. 8:1251223. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1251223

Hinsliff, G. (2023). ‘Children are holding a mirror up to us’: why are England’s kids refusing to go to school? The Guardian. (2nd sept)

Holmes, C., Guenther, J., Morris, G., O'Brien, D., Inkamala, J., Wilson, J., et al. (2024). Researching school engagement of aboriginal students and their families from regional and remote areas project: Yipirinya school case study. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 34, 145–151. doi: 10.47381/aijre.v34i1.730

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. (2014). A response to intervention model to promote school attendance and decrease school absenteeism. Child Youth Care Forum 43, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9222-1

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. A. (2022). Multi-tiered systems of support for school attendance and its problems: an unlearning perspective for areas of high chronic absenteeism. Front. Educ. (Lausanne) 7:1020150. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1020150

McDonald, B., Lester, K. J., and Michelson, D. (2023). ‘She didn't know how to go back’: school attendance problems in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic—a multiple stakeholder qualitative study with parents and professionals. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 93, 386–401. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12562

McGrath, P. (2023). Exploring barriers to education for Traveller children in the North Cork region and identifying local solutions to address these barriers : UCC. Available at: https://tnc.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Draft-Research-report-Exploring-Barriers-to-Education-for-Traveller-Children-in-the-North-Cork-Dr-Patricia-McGrath-2023.pdf

McKay-Brown, R., McGrath, L., Dalton, L., Graham, A., Smith, J., and Ring, K. E. (2019). Reengagement with education: a multidisciplinary home-school-clinic approach developed in Australia for school-refusing youth. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.08.003

Melvin, G. A., Heyne, D., Gray, K. M., Hastings, R. P., Totsika, V., Tonge, B. J., et al. (2019). The kids and teens at school (KiTeS) framework: an inclusive bioecological systems approach to understanding school absenteeism and school attendance problems. Front. Educ. 4:61. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00061

Millar, D. (2018). School attendance data from primary and post-primary schools, 2016/17, analysis and report to the child and family agency. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

Morgan, F., and Costello, E. (2023). Square Pegs: Inclusivity, compassion and fitting in-a guide for schools. Independent Thinking Press.

Morrow, A. S., and Villodas, M. T. (2018). Direct and indirect pathways from adverse childhood experiences to high school dropout among high-risk adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 28, 327–341. doi: 10.1111/jora.12332

O’Toole, C. (2022). When trauma comes to school: towards a trauma-informed praxis in education. Int. J. Schools Soc. Work 6, 1–22.

O’Toole, C. (2023). Introducing a trauma-informed framework for education, presented as part of the symposium, ‘advancing trauma-informed practice in Ireland: critical perspectives on design, standards, and implementation’. Psychological Society of Ireland Annual Conference, November 8–10th, Cork.

O’Toole, C., and Devenney, R. (2020). “School refusal: What is the problem represented to be? A critical analysis using Carol Bacchi’s questioning approach,” in Social theory and health education: Forging new insights in research. eds. D. Leahy, K. Fitzpatrick, and J. Wright (Abingdon: Routledge), 104–113.

O’Toole, C., and Dobutowitsch, M. (2023). The courage to care: teacher compassion predicts more positive attitudes toward trauma-informed practice. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 16, 123–133. doi: 10.1007/s40653-022-00486-x

Orchard, T. (2017). Remembering the body: Ethical issues in body mapping research. New York, NY: Springer Link.

Powell, T. M. (2020). The scars of suspension: testimonies as narratives of school-induced collective trauma (order no. 27997787). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest one academic. (2418354350).

Quinlan, M. (2021). Out of the shadows: Traveller & Roma Education: Voices from the communities. Government of Ireland. Available at: https://1d3ad8c0-4fe5-46e5-9b07-dc213044ac84.filesusr.com/ugd/5cfafe_0dc001ab34414419b855ebe82b7890f1.pdf

Rogers, M., and Aglukark, K. (2024). Supporting school attendance among indigenous children and youth in Canada: a review. First Peoples Child Family Rev. 19, 32–46. Available at: https://fpcfr.com/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/621

Sanders, J., Joseph-McCatty, A., Massey, M., Swiatek, E., Csiernik, B., and Igor, E. (2023). Exposure to adversity and trauma among students who experience school discipline: a scoping review. Rev. Educ. Res. 94:00346543231203674. doi: 10.3102/0034654323120367

Stempel, H., Cox-Martin, M., Bronsert, M., Dickinson, L. M., and Allison, M. A. (2017). Chronic school absenteeism and the role of adverse childhood experiences. Acad. Pediatr. 17, 837–843. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.013

Stewart-Tufescu, A., Struck, S., Taillieu, T., Salmon, S., Fortier, J., Brownell, M., et al. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences and education outcomes among adolescents: linking survey and administrative data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:11564. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811564

Thambirajah, M. S., Grandison, K. J., and De-Hayes, L. (2008). Understanding school refusal: a handbook for professionals in education, health and social care : Jessica Kingsley Publishers Available at: https://go.exlibris.link/My9qZhkZ.

Thornton, M., Darmody, M., and McCoy, S. (2013). Persistent absenteeism among Irish primary school pupils. Educ. Rev. 65, 488–501. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.768599

Tomaszewski, W., Zajac, T., Rudling, E., Riele, K., McDaid, L., and Western, M. (2023). Uneven impacts of COVID-19 on the attendance rates of secondary school students from different socioeconomic backgrounds in Australia: a quasi-experimental analysis of administrative data. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 58, 111–130. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.219

Keywords: school attendance, school avoidance, school exclusion, lived experience, trauma-informed, young people, parents, practitioners

Citation: O’Toole C and Ćirić T (2024) Compassion, collaboration and cultural-responsiveness: insights on promoting successful pathways through education for students who face school attendance barriers. Front. Educ. 9:1456388. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1456388

Edited by:

Carolina Gonzálvez, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaJoanna Anderson, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 O’Toole and Ćirić. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catriona O’Toole, Q2F0cmlvbmEuYS5vdG9vbGVAbXUuaWU=; Tara Ćirić, dGFyYS5jaXJpY0BtdS5pZQ==

Catriona O’Toole

Catriona O’Toole Tara Ćirić

Tara Ćirić