- 1Institute of Education & Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2School of Education and Social Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Shepparton Campus, Shepparton, VIC, Australia

- 4Department of Medicine, Goulburn Valley Health, Shepparton, VIC, Australia

- 5Proyash Institute of Special Education and Research, Bangladesh University of Professionals, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Neurodiversity movement around the world pushes the society to ensure inclusion in all settings in where societal perspectives play the vital roles for effective changes. The aim of this study was to explore the scenario of inclusion of neurodiverse students of Bangladesh. This qualitative study sheds light on social perspectives toward neurodiverse students; as well as their educational opportunity and challenges in formal education. Through purposive sampling, eight parents of neurodiverse students and eight special educators were chosen as the sample of this study. In depth data were collected through interview questionnaire from both groups. Interpretation of data exhibited the misconception, prejudices, and social stigma toward neurodiverse students. Findings of the study also revealed the challenges regarding education of neurodiverse students such as: inadequacy of resources, awareness, teachers training and infrastructure. The study concludes by proposing possible strategies such as: proper policy and curriculum development, capacity building and awareness raising to overcome those challenges.

1 Introduction

Neurodiversity is a concept that recognizes and respects the natural variation in human neurological functioning. It emphasizes the idea that neurological differences, such as those associated with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other conditions, are a natural part of human diversity rather than deficits to be cured or fixed (Diamond and Hong, 2010). The neurodiversity movement advocates for acceptance, inclusion, and accommodations for individuals with diverse neurological traits, promoting the idea that neurodiverse individuals have unique strengths and perspectives that can contribute positively to society (Diamond and Hong, 2010). According to Acevedo and Nusbaum (2020), the traditional methods of teaching-learning struggles in including neurodiverse children which calls for changes in policy and practices. He added that inclusion of such students regardless of their neurodiverse conditions require impartial opportunities in order to be succeeded in both social and academic aspects of their life. Furthermore, Inclusive education is a fundamental right for all individuals, regardless of their neurodiversity (Nieminen and Pesonen, 2022). In this modern society, academic degrees became more vital (Manalili, 2021). And also, the number of neurodiverse learners is growing in higher education (Calder et al., 2013). Yet there is a scarcity of research that focuses on the challenges in including learners with neurodiverse conditions in education (Ruble et al., 2011).

According to Syharat et al. (2023), neurodiverse students face societal pressure to maintain neurotypical norms in order to evade adverse perceptions. They also mentioned the social challenges that are perceived in academic institutes, saying “As neurodiversity is invisible, students may self-silence and mask their neurodiversity to survive the graduate school experience, as they fear that if deficit-based assumptions were applied to them, they might be perceived as less capable and thus miss out on financial support and career opportunities.” The study of Cortiella and Horowitz, 2014 shows that a number of neurodiverse students in higher education refrain themselves from seeking career help from university support centers.

While there is growing research on neurodiversity including interventions, accommodations, and support services in developed countries, there is a lack of research focusing on the specific socio-cultural, economic, and educational contexts of developing countries (Lim et al., 2023). This gap hinders the development of culturally relevant and effective strategies for promoting the inclusion, education, and well-being of neurodiverse individuals in these settings. Developing countries often face specific challenges, such as limited resources, cultural stigma, and inadequate support systems, which can exacerbate the barriers to education and inclusion for neurodiverse individuals (Koegel et al., 2009). Research can identify these challenges and inform the development of targeted interventions and policies to address them. Hence, researching educational settings and neurodiversity in the context of developing countries is vital. By understanding the needs and experiences of neurodiverse individuals in developing countries, researchers can advocate for policies and practices that promote inclusive educational environments and ensure equitable access to education for all. Moreover, research can help identify effective strategies for supporting neurodiverse individuals in educational settings, including teacher training programs, community-based interventions, and collaboration with local organizations and stakeholders. This study aims to explore social perception toward neurodiverse learners. In addition, this research aims to specify way forward of developing inclusive educational settings highlighting the challenges of educational opportunities of neurodiverse learners in Bangladesh. The study aims to answer the following research objectives:

• To explore social perceptions toward neurodiverse students in Bangladesh.

• To identify the challenges to include neurodiverse students into formal educational settings to ensure inclusive education.

• To develop strategies to support inclusion of neurodiverse students into formal educational settings in the context of developing countries.

2 Materials and methods

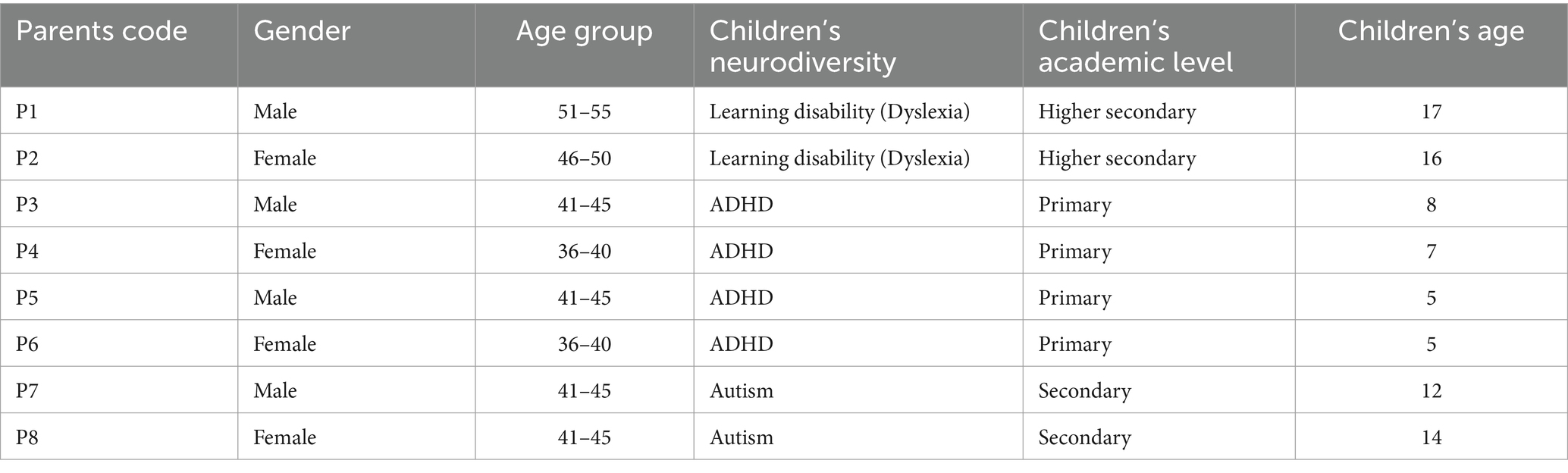

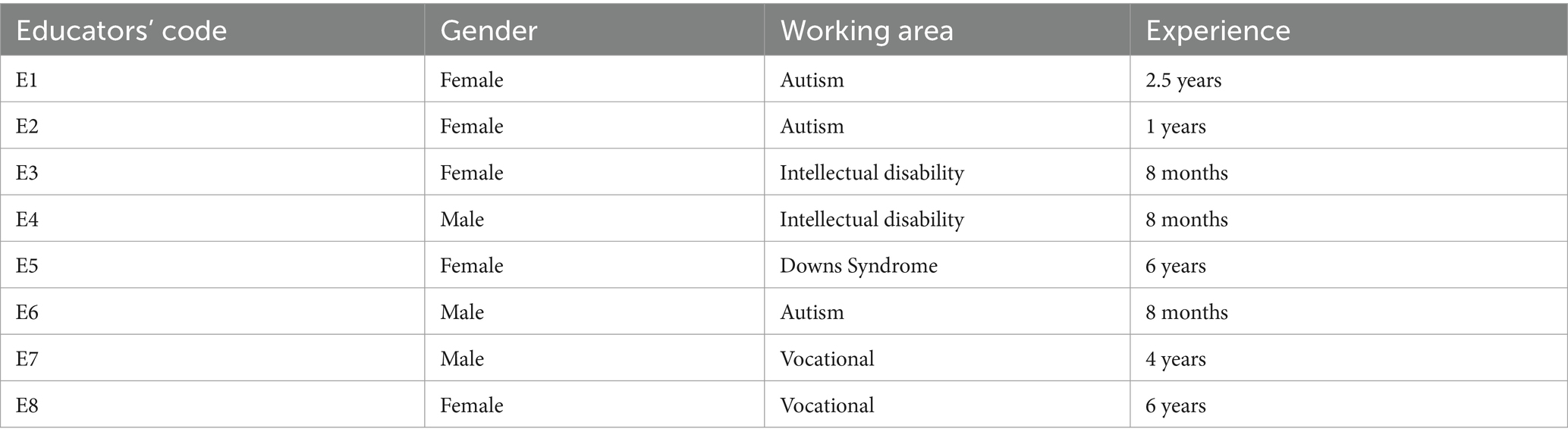

This study was intended to investigate the current scenario of neurodiverse students of Bangladesh, as well as to understand their situation in progression of the path of inclusion. The study aimed to find out the status of inclusion and the social perspective toward inclusion of the students with neurodiverse background. It also explored their access and challenges related to the accessibility in formal education. Therefore, this study embarked on a qualitative method to extract the perspectives in detail. The selection of qualitative research methodologies is influenced by various factors, including the specific research question, the objectives of the study, and the characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation (Sandland et al., 2003). In total 16 participants were selected as the sample of this study where 8 of them are parents of neurodiverse students (Table 1) and the other 8 of them are special educators serving the related field (Table 2). These two sample groups were selected through purposive and convenient sampling method. According to Cooksey and McDonald (2019), purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling methodology employed by researchers to deliberately choose participants or cases based on specified requirements that are pertinent to the study topic or objectives. Considering researchers’ convenience to reach out to the participants, convenience sampling was employed. Besides, purposive sampling was employed with the purpose of addressing the parents and special educators who are related with neurodiverse learners.

The academic level of the children in Table 1 was determined in accordance with the Bangladesh Education Statistics 2021 (Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANBEIS), 2022) which categorizes primary school going children aged 6–10 years, secondary 11–15 years and higher secondary 16 years and above. In this study, the children of primary, secondary and higher secondary age group were taken into consideration while selecting the parents to understand the broader areas of experience.

In accordance with previous research and the objectives of the current study, in-depth interview questionnaire consisting of several items was made. Required data were gathered through the in-depth interview sessions with the participants. The interview questionnaire consisted of 14 items designed to collect insights from the sample. The items were categorized into three main domains such as social perspective, educational potential, and challenges encountered by neurodiverse students in the context of Bangladesh. The interview sessions were administered via systematic planning where data was collected in several days with the consideration of the convenience of data collector and the participants to collect the data in an organized manner. Also, the interview was conducted while considering the principles of General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). The researchers made sure that all the participants are well known to the intention and objectives of this research. Before participating, they were also assured of the confidentiality of their personal information. Several methods, including member verification, peer debriefing, as well as rich and thick descriptions, were utilized to validate the data. Member checking allowed participants to review and confirm the findings as well as to ensure accuracy. Peer debriefing involved colleagues with expertise in special education to review the research methodology and data analysis. Rich and thick descriptions were employed to furnish extensive contextual information regarding the participants and settings. Findings from the collected data were categorized considering the highlighted themes marked out in the interview sessions. With thematic analysis procedure the data were further organized, clarified and modified and themes and sub-themes were extracted.

3 Results

The following sections have addressed the social perception of neurodiverse students, the challenges associated with including them in formal educational settings, and the potential solutions to overcome these challenges in developing countries.

3.1 Social perceptions toward neurodiverse students in Bangladesh

Social perceptions toward neurodiverse students in developing countries can vary significantly depending on cultural, societal, and educational factors. Participants of this study have highlighted some common perceptions and attitudes toward neurodiverse students in the context of Bangladesh.

3.1.1 Stigma and misconceptions

All of the participants have claimed that neurodiversity is often poorly understood, and there may be widespread stigma and misconceptions surrounding conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and others. They have also added that neurodiverse individuals and their families face discrimination, prejudice, and social exclusion due to these misconceptions.

According to Respondent P1,

“I am subjected to societal harassment due to the fact that my child deviates from the norm. In certain instances, relatives and friends also express their dissatisfaction.”

Children and persons with neuro diverse disability often face a negative outlook from general population. Many people consider such disabilities as being ‘mad’ or ‘crazy’.

Respondent E2 said,

“A large number of people of our society try to refrain from coming in contact with children with neuro diverse disabilities as they think such children are “Mad” and it is dangerous to be near them.”

On this issue Respondent P3 added,

“Many people think that these neurodiverse conditions are the curse of God. Also, there is a common belief that these conditions are the consequence of the sin of parents.”

Although respondent E1 slightly differed from the response of E2 and P3, saying,

“Nowadays many people possess the basic idea of neurodiversity among children due to social awareness campaigns in tv and social media. But often they have no idea how to deal with these kinds of children.”

3.1.2 Lack of awareness

Most of the participants claimed that they have found lack of awareness and understanding of neurodiversity among the public, including educators, policymakers, and community members. This lack of awareness lead to negative attitudes, stereotypes, and biases toward neurodiverse individuals, as well as a reluctance to provide support and accommodations. According to participant P2,

“School environment is not conducive in many cases. Lack of awareness is widely visible in school settings. There is resentment among teachers and friends about the neurodiversity.”

Following the experience of the special educators, there is a huge gap in the awareness level toward neurodiverse students. Most of the people do not understand the concepts, differences, and needs of such students.

Respondent E1 discussed about the negligence among parents to their children’s neurodiversity. She mentioned,

“Many parents either cannot identify their children’s neurodiversity or show reluctancy in acknowledging them. They also show unwillingness in putting effort in academic or other activities of their neurodiverse student.”

Respondent E3 responded similarly. She said,

“Many parents shut off the door to putting effort on their children, when they understand their children have special needs. They don’t seek out for any sort of help or support services.”

3.1.3 Cultural beliefs and norms

Most of the participants opined that cultural beliefs and norms have significantly influenced toward perceptions of neurodiversity and they found stigma attached to disabilities or differences, leading to social isolation and marginalization of neurodiverse individuals. According to participant P3,

“As neurodiversity is not socially acceptable in Bangladesh, we mostly keep ourselves away from social events.”

In the community, most of the parents of neurotypical children show hesitancy in letting their children develop friendship with neurodiverse children. Respondent E4 mentioned this issue saying,

“Regular parents don’t want their children getting mixed up with special children. Rather they want their children to become friends with children like them. These situations worsen when the special child is from a low-incoming family. There is always a socio-economic discrimination in play there.”

Both the neurodiverse child and their parents face social discrimination due to the adverse outlook toward disability. A common belief among people regarding the causes of disabilities is the outcome of parent’s sin. Respondent E4 said,

“Parents of regular child and other people, even if they are educated, possess such ideas that a student with neurodiverse disability must have parents who are involved in corruption, or such crimes and such disability of their child is God’s way of punishment.”

3.1.4 Family dynamics

All of the participants claimed that families of neurodiverse individuals face societal pressure to conform to cultural norms and expectations, which exacerbate feelings of shame, guilt, and stigma associated with neurodiversity. They also added that their families experienced social isolation and discrimination due to their association with a neurodiverse member.

Respondent P5 said,

“Whenever I take my child to a public space, other parents with regular children tend to avoid me and my child. Some people even mock us when they see us enjoying ourselves.”

Such isolations have adverse impact on the child too. Facing guilt and shaming from the society, parents and family members feel frustrated.

Respondent E3 mentioned that,

“Many parents of neurodiverse children feel ashamed to bring their child in any public program or environment. If they have multiple children, they usually take the regular children to any social gathering leaving the special one back at home.”

3.1.5 Support networks

A few of the participants have claimed that scarcity of support networks and resources for neurodiverse individuals and their families hinder access to essential services and support systems.

Respondent E3 mentioned about some organizations which are delivering vocation related support services to neurodiverse students. She said,

“Some organizations provide hand to hand ICT training to the children with Down Syndrome or Intellectual Disability. But there are no such facilities for Children with ASD or Cerebral Palsy.”

Although respondent P3 declined the existence of adequate support networks. She said,

“I can’t find any organization that might help me or my child in a manner that can be called support service. There are some charity-based organizations but they don’t actually provide any long term supports.”

3.2 Challenges to include neurodiverse students into formal educational settings

The study has revealed that neurodiverse students face several challenges when it comes to including them into formal educational settings:

3.2.1 Limited resources

Most of the participants have reported that educational settings of Bangladesh have limited resources for special education, including funding, trained personnel, and specialized support services. They added that this can hinder the development and implementation of inclusive practices and accommodations for neurodiverse students.

Respondent E6 said,

“There is a huge gap between the demand and provision of proper resources for neurodiverse students. There is scarcity of even simple teaching materials or aids. Although some local shops aids for neurodiverse students, they are mostly therapy based. But the availability of proper or modified teaching materials for neurodiverse students are almost zero.”

Respondent E4 added,

“The available resources are very much expensive. Also, the available resources cannot be properly utilized due to lack of knowledge.”

While the special educators mentioned the inadequacy of resources as the prime issue in the education of neurodiverse children, the parents mainly focused on the issues related to educators and school authorities.

Respondent P6 said,

“It is very hard to enrol neurodiverse children in school or private coaching. Although the authority and teachers might not show their unwillingness directly, their approach certainly gives off negative ambiences.”

3.2.2 Lack of awareness and understanding

More than half of the participants claimed that there exists a lack of awareness and understanding of neurodiversity among educators, policymakers, and the broader community in Bangladesh. This can lead to misconceptions and discrimination against neurodiverse students, making it difficult for them to access appropriate support and accommodations in educational settings.

Respondent P8 said,

“A large number of people of our society still think that neurodiverse children are ‘Mad’, and these children are neglected in many sectors because the people are not ready to accept them as they are.”

According to the special educators, many of the teachers as well as their colleagues who are involved in teaching neurodiverse students possess negative perception toward these students. Respondent E7 mentioned that,

“I have seen many of my colleagues holding discriminatory mindset towards the neurodiverse students. In my opinion such discrimination makes it harder to ensure education for them.”

3.2.3 Inadequate teacher training

The interviewed participants also reported that teachers in Bangladesh have not received adequate training or professional development on how to support neurodiverse students effectively. This can result in the lack of knowledge and skills in implementing inclusive teaching practices and addressing the diverse needs of neurodiverse learners in the classroom.

Due to lack of trained personnel who can teach and manage neurodiverse students, many schools show unwillingness to enroll these students in their school. Respondent E5 said,

“It is already hard to be enrolled in education, co-curricular events, private coaching, or recreational activities for children with disabilities. But it is much harder for the neurodiverse children. Schools show unwillingness sometimes directly or sometimes by their approach”.

Respondent E7 said,

“Teachers training in Bangladesh are exceedingly insufficient. Most of the teachers nowadays complete one year of Bachelor of Special Education (BSEd) program or other short trainings which led them to believe they know everything about handling special children. Due to their adverse mindset towards learning new practices, they fail to properly implement newer practices. The teachers training programs in Bangladesh are also very much outdated. Newer concepts, training, terms are not included in these training. As a result, the trainings are not adequately fruitful.”

3.2.4 Cultural barriers

All of the participants agreed that cultural beliefs and practices have significantly influenced attitudes toward neurodiversity and shaped the way neurodiverse students are perceived and treated in educational settings. Hence, prejudice and misconceptions surrounding neurodiversity prevent families from seeking support for their neurodiverse children, further marginalizing these students within the education system.

Many parents of regular children hold the conception that mixing with neurodiverse children might foster disabilities in their children. They also think access of neurodiverse children in public areas might cause disturbance.

Respondent E6 said,

“People think letting neurodiverse children in shopping mall, cinema halls or amusement parks might cause occurrence and endanger their children. Due to their parent’s attitude, age level children also grow negative outlook towards them and show hesitancy to play or socialize with neurodiverse children.”

3.2.5 Accessibility and infrastructure

Three-fourth of the participants also reported that Bangladeshis have been facing challenges related to infrastructure and accessibility, such as inadequate facilities, lack of transportation, and inaccessible learning materials. These barriers can disproportionately affect neurodiverse students, limiting their ability to participate fully in educational activities and access essential support services.

Respondent E7 said,

“In the schools for the neurodiverse students, there can be seen vast shortage of proper infrastructures. Specially, many private schools, even though they are very much eager to provide services, fail to do so due to the absence of proper infrastructural facilities. Teaching several neurodiverse students in a common space often lead to chaotic situations. One students’ hyperactivity and aggression might trigger others.

In urban areas, as many schools run in tiny apartments, neurodiverse students lack the facilities of playgrounds. Also, many schools cannot properly ensure safe accessibility and mobility of neurodiverse students.”

3.2.6 Limited support systems

More than half of the participants agreed that limited or fragmented support systems including specialized services, therapies, and community resources for neurodiverse students are found in Bangladesh. This can leave neurodiverse students and their families without the necessary support networks to address their unique needs and navigate the challenges they face in educational settings.

Respondent E1 added on these issue that,

“Many parents are aware of the services that are available to them. But their reluctancy in effort towards their neurodiverse child gets in the way of seeking such services.”

3.3 Way forward of including neurodiverse students into formal educational settings in the context of Bangladesh

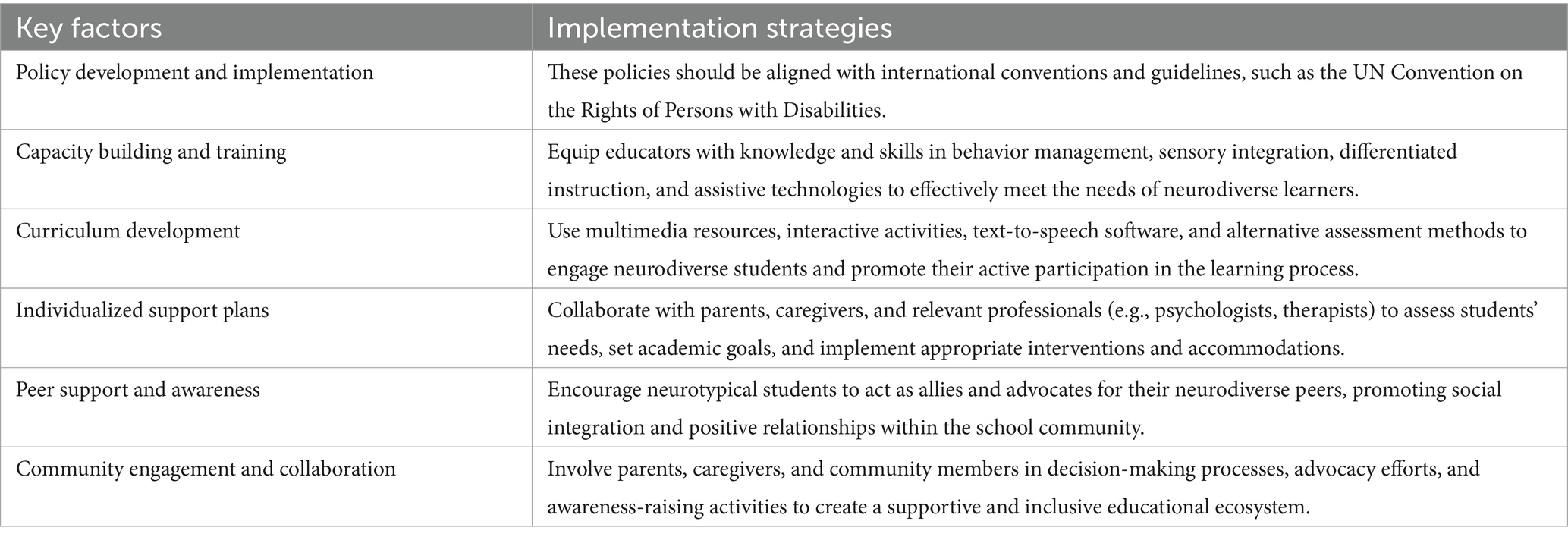

Inclusion of neurodiverse students into formal educational settings in the context of developing countries requires a multifaceted approach that addresses various aspects of the educational system, societal attitudes, and support mechanisms. Based on the findings of the interview data, the study proposes following strategies to include neurodiverse students into formal educational settings:

3.3.1 Policy development and implementation

One-third of the participants highlighted to develop and enforce policies education policies that prioritize the rights and needs of neurodiverse students and promote inclusive education. According to participant P7,

“Although the importance of inclusive education in Bangladesh is being discussed at various levels, it is not fully effective in practical terms.”

On this issue respondent E5 mentioned,

“Although some of the schools are trying to implement the existing policies, many schools are not working towards it.”

Respondent E4 said,

“The current laws and policies are not adequate to implement inclusion properly as they are vague in nature. To ensure proper inclusion of the neurodiverse students there should be separate specialised policy on this matter.”

One of the policies regarded as the biggest challenge is lack of proper monetization. As a result, the real impact of laws and policies cannot be assessed. Respondent E2 mentioned,

“There needs to be school based monetization for proper implementation of policies. Gross special students intake per year and the results of these students should be carefully observed.”

3.3.2 Capacity building and training

Most of the participants emphasized the importance of providing training and professional development opportunities for teachers, school administrators, and support staff on neurodiversity, inclusive teaching practices, and strategies for supporting neurodiverse students.

Respondent E5 said.

“Laws and policies regarding inclusion should be incorporated in teachers’ training so that teachers become more aware.”

3.3.3 Curriculum development

A few participants emphasized to design and adapted curriculum materials to be accessible, flexible, and responsive to the diverse learning styles and abilities of neurodiverse students. They highlighted the implementation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles to create flexible learning environments and instructional materials that accommodate diverse learning styles and abilities, including those of neurodiverse students.

Respondent E1 said,

“The mark distribution in the curriculum can be reorganized. For the neurodiverse children the benchmark for GPA can be lowered so that they can achieve a minimum good result.”

Respondent E7 added,

“The curriculums that are followed in teaching neurodiverse students are not updated. Mostly they focus on supporting children based on their developmental milestones. And after graduating they are led to only a few fixed job sectors. But this situation can be changed through incorporating different skills in the curriculum. Curriculum should be developed in a way that can harness individualized potential of students.”

Almost all the educators agreed on the fact that more life skills training should be incorporated in the curriculum for neurodiverse students.

3.3.4 Individualized support plans

Two-third of the participants highlighted to develop individualized support plans, such as Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) or Individualized Support Plans (ISPs), for neurodiverse students based on their unique strengths, challenges, and learning needs.

On the issue of individualized support plan, respondent E2 emphasized on the capacity building of the teachers in order to support neurodiverse students. She said,

“If the teacher receives proper training on developing and implementing support plans for the neurodiverse students, they can identify the particular strong area of a particular student and proceed to utilize it.”

3.3.5 Peer support and awareness

Few participants argued to foster a culture of acceptance, empathy, and inclusion among students through peer support programs, and awareness campaigns.

Respondent E3 said,

“To raise peer awareness teachers can arrange group activities as part of the academic program which will contain marks on group engagement. That way the peer group will be more motivated to include neurodiverse students.”

Respondent E6 also emphasized on collaboration between regular and special children. He said,

“Group activities specially games and sports, co-curricular activities can make the regular children more friendly and accepting towards the neurodiverse children.”

3.3.6 Community engagement and collaboration

Nearly half of the participants argued to develop partnerships with community organizations, NGOs, disability advocacy groups, and government agencies to leverage resources, expertise, and support services for neurodiverse students and their families.

Respondent E4 mentioned the importance of collaboration of the community around the schools. He also emphasized on the role of religious leaders in raising awareness among common people. Respondent E4 said,

“In the Jumma khutba (Friday prayer speech), imams can talk about the neurodiverse students, their education and inclusion in the society. This will help in increasing awareness and positive attitude among the people of the community.”

The above-mentioned suggestions from parents and educators have been summarized as factor wise implementation protocol to ensure inclusive education for neuro diverse children in Table 3.

4 Discussion

The study found that Neurodiversity is poorly perceived commonly which is associated with stigma and misconceptions. Besides, the lack of awareness among the people leads them to have negative attitudes, stereotypes, and biases toward neurodiverse individuals which limits support and accommodations for the students. Clouder et al. (2020) also identified that students with neurodiversity face challenges due to the inflexible academic climate because of negative attitudes and stigma. Besides, there is a lack of awareness and understanding of neurodiversity among the public, including educators, policymakers, and community members. In this case, the research of Brownlow et al. (2021) found that the behavioral features of neurodiverse students are perceived as challenging because of the limited understanding of neurodiversity. Also, many neurodiverse young pupils are into interventions with unrealistic perceptions about them (Billington, 2006). The present study revealed that the poor understanding of neurodiversity leads those significant stakeholders into stigma which constrains the support needed for the children with neurodiversity. Besides, the negative stigma through cultural beliefs influences the perception toward neurodiversity which leads to discrimination and social exclusion. In this case, Little (2017) also confirmed that limited perception may affect the teachers to consider themselves unable to maintain the class well. Consequently, insufficient knowledge with limited support services negatively impacts on the students’ meaningful participation at school (Avramidis and Burden, 2000).

The present study showed that the neurodiverse children’s families often have feelings of shame, guilt and stigma due to the social norms. These families face discrimination and social exclusion due to their relation with the neurodiverse family member. Because of the society’s negative attitude toward neurodiversity due to a lack of understanding, the families also feel guilty about it. Neurotypical young children often have embarrassment, guilt and resentment toward their neurodiverse siblings. Another study Sasson et al., 2017 also confirmed that neurotypical people get a negative attitude toward neurodiverse people within a very short time of being introduced with them because of insufficient information.

The concerned study identified several challenges to including neurodiverse students into formal educational settings which include limited resources, lack of awareness and understanding, inadequate teacher training, cultural barriers, accessibility and infrastructure, and limited support system. Several previous research supported the findings of the present research in various dimensions. For example, a study (Sandland et al., 2003) highlighted the fact that diverse characteristics of neurodiverse students led the teachers to emphasize on the challenges rather than addressing the needs of the students. Another study (Brownlow et al., 2021) focused on the peer attitude as a barrier to include neurodiverse students in formal schools effectively. The study reported that some children may get confused about understanding their peers which may lead them to be excluded from social groups in the class. Moreover, the rigidity of addressing specific learning needs might be responsible for the students missing wider opportunities of participation aside from the specific learning interest of the school (Colombo-Dougovito et al., 2020). On the other hand, the present study explored that the limited resources, teachers’ training as well as limited support system are the major factors impacting the educational services for neurodiverse students. Because of limited support and the lack of understanding the neurodiversity, the inclusion of these students into formal education is still very poorly implemented. The negative attitude and social stigma coupled with the cultural norms restrict the neurodiverse students along with the school as well as community settings. Several researches (Clouder et al., 2020; Cortiella and Horowitz, 2014) have also explored that the concept of ‘ableism’ plays a critical role in micro-exclusion, and it may label the neurodiverse students as ‘different’. Therefore, neurotypical students may show negative attitude toward their neurodiverse peers because they might get this attitude from the adults in their community (Cortiella and Horowitz, 2014).

The present study found some specific suggestions for a way forward to include neurodiverse students into formal educational settings in the context of Bangladesh through the participants’ voice. Firstly, the study suggested that there should be appropriate policies and their effective implementation which will highlight the rights and needs of the neurodiverse students to promote the school to be inclusive for all. In this scenario, Cook and Ogden (2022) also supported the fact that there should be a provision to specifically have a structure to guide how to support the students.

Secondly, the present study identified that the participants emphasized on teacher training and professional development for the supporting staff to ensure a meaningful inclusive teaching practice in the school. This finding is confirmed by another research (Dybvik, 2004) where the teaching pedagogies are mentioned as an important factor in responding to differences without labeling the disability. Moreover, there is significant scope for increased training of school staff and professionals because it will help to increase teachers’ self-efficacy and therefore, effective teaching strategies could be implemented for neurodiverse students (Colombo-Dougovito et al., 2020). In addition, Florian (2017) mentioned that the teacher training should be implemented with a broader perspective to make all teachers ready to respond to individual differences effectively. Moreover, professional development should focus on the integration of basic principles which include mission, vision, beliefs, competencies, and the overall environment (Korthagen, 2017).

Thirdly, several participants of the study signified in designing and adapting curriculum materials to make those more accessible, flexible, and responsive to the needs and abilities of the neurodiverse students. The study focused on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles to ensure a flexible learning environment and instructional materials to address the learning needs of these students. Reinholz and Ridgway (2021) also signified that the recognition of creating classrooms and social settings that can be modified and used in many ways can co-exist with the UDL concept in supporting the students with neurodiversity. In this case, another research (Calder et al., 2013) recommended that the concept of responding to learners’ diversity should focus on the expansion of the typical environmental element available for everyone while still recognizing individual differences.

Fourthly, the present study highlighted on the development of individual support plans such as IEP to address the individual learning characteristics and needs. In this perspective, the participants of the study emphasized on teacher training to develop and implement individual support plans for the neurodiverse students. Hebron (2017) also focused on the importance for schools to understand and acknowledge the individual unique needs rather than making generalized conclusions in any level and type of support for the neurodiverse students. Another research (Cook and Ogden, 2022) also reported that the heterogeneous traits of the autistic children should be incorporated into the educational ideology, teacher attitude, staff training and educational environment.

In the fifth approach, the present study focused on the peer support and awareness as a factor in including the neurodiverse students into the formal education. The participants mentioned a culture of acceptance, empathy and inclusion among the students will be ensured through meaningful peer support and awareness of neurodiversity. Arduin (2015) shared that the societal change in perception, understanding and beliefs about disability and diversity depends on awareness. Also, each child should be equally treated in the school culture (Dwyer, 2022). Besides, Lindsay et al. (2013) also supported the social engagement with other students in intervention programs for the neurodiverse students. In this case, the academic interventions should be conducted in an environment where social interaction can occur naturally within typical peers (Humphrey and Lewis, 2008). Moreover, motivating to connect with peers and forming social groups with the same interests can influence social participation in the school setting (Humphrey and Lewis, 2008; Koegel et al., 2009; Koegel et al., 2013).

In the present study, community engagement and collaboration were suggested as another strategy for including the neurodiverse students in the formal schools. The study emphasized on community engagement and a support network consisting of resources, and expertise from government and community organizations which can ensure the meaningful inclusion of students with neurodiversity. Colombo-Dougovito et al. (2020) also supported that fact of community inclusion by collaborating among the community people with neurodiversity with the community partners within a broad scale of community participation. The present study found that the parents having diverse age range of children experience stress and insufficient support from community. Another study (Haque et al., 2022) also revealed that parental stress tends to higher with the aging of their children with neurodiversity. However, a relevant study (Faden et al., 2023) addressed parents with wide age range of children that found generalized parental experience on insufficient community and school support services. The study mentioned three approaches for community collaboration which include physical activity, social access, self-advocacy and family support. Moreover, social accessibility through various strategies such as accessible group communication, recognition of intersectionality’s, reaching out to marginalized students with neurodiversity etc. can ensure the meaningful connection of neurodiverse students with the community (Hughes, 2016).

5 Conclusion

Education is a key driver of social and economic development ensuring that neurodiverse individuals have access to quality education that can lead to improved outcomes in employment, health, and overall well-being. By conducting research on neurodiversity in educational settings, policymakers and practitioners can work toward building more inclusive societies that benefit everyone.

The findings of this research on educational settings and neurodiversity in the context of developing country may guide policy makers, curriculum developers and educators to promote equity, inclusion, and social justice for neurodiverse students and moving toward the broader goals of sustainable development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MTN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MAN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NO: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the administrative and technical support of Proyash Institute of Special Education and Research (PISER).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acevedo, S. M., and Nusbaum, E. A. (2020). “Autism, neurodiversity, and inclusive education” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Arduin, S. (2015). A review of the values that underpin the structure of an education system and its approach to disability and inclusion. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 41, 105–121. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1006614

Avramidis, E. P., and Burden, R. (2000). A survey into mainstream teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school in one local education authority. Educ. Psychol. 20, 191–211. doi: 10.1080/713663717

Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANBEIS). (2022). Bangladesh education statistics 2021. Dhaka: Ministry of Education. Available online at: https://banbeis.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/banbeis.portal.gov.bd/npfblock/Bangladesh%20Education%20Statistics%202021_compressed-1-235.pdf

Billington, T. (2006). Working with autistic children and young people: sense, experience and the challenges for services, policies and practices. Disabil. Soc. 21, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/09687590500373627

Bottema-Beutel, K., Park, H., and Kim, S. Y. (2018). Commentary on social skills training curricula for individuals with ASD: social interaction, authenticity, and stigma. J. Autism Dev. Dis. 48, 953–964. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3400-1

Brownlow, C., Lawson, W., Pillay, Y., Mahony, J., and Abawi, D. (2021). “Just ask me”: the importance of respectful relationships within schools. Front. Psychol. 12:2281. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678264

Calder, L., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2013). Sometimes I want to play by myself’: understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism 17, 296–316. doi: 10.1177/1362361312467866

Clouder, L., Karakus, M., Cinotti, A., Ferreyra, M. V., Amador Fierros, G., and Rojo, P. (2020). Neurodiversity in higher education: a narrative synthesis. High. Educ. 80, 757–778. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00513-6

Cologon, K. (2012). Confidence in their own ability: postgraduate early childhood students examining their attitudes towards inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Edu. 16, 1155–1173. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2010.548106

Colombo-Dougovito, A. M., Dillon, S. R., and Mpofu, E. (2020). “The wellbeing of people with Neurodiverse conditions” in Sustainable community health. ed. E. Mpofu (Cham, UK: Palgrave Macmillan), 499–535.

Cook, A. (2024). Conceptualisations of neurodiversity and barriers to inclusive pedagogy in schools: a perspective article. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 24, 627–636. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12656

Cook, A., and Ogden, J. (2022). Challenges, strategies and self-efficacy of teachers supporting autistic pupils in contrasting school settings: a qualitative study. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 371–385. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1878659

Cooksey, R., and McDonald, G. (2019). “How do I manage the sampling process?” in Surviving and thriving in postgraduate research. eds. R. Cooksey and G. McDonald. 2nd ed (Singapore: Springer), 827–894.

Cortiella, C., and Horowitz, S. H. (2014). The state of learning disabilities: Facts trends emerging issues. 3rd Edn. National Centre for Learning Disabilities: New York.

Diamond, K. E., and Hong, S. Y. (2010). Young children's decisions to include peers with physical disabilities in play. J. Early Interv. 32, 163–177. doi: 10.1177/1053815110371332

Dwyer, P. (2022). The neurodiversity approach (es): what are they and what do they mean for researchers? Hum. Dev. 66, 73–92. doi: 10.1159/000523723

Faden, S. Y., Merdad, N., and Faden, Y. A. (2023). Parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a mixed methods approach to understanding quality of life, stress, and perceived social support. Cureus 15:e37356. doi: 10.7759/cureus.37356

Florian, L. (2017). “Teacher education for the changing demographics of schooling: policy, practice and research” in Teacher education for the changing demographics of schooling. eds. L. Florian and N. Pantic (Cham, UK: Springer), 1–5.

Florian, L., and Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. Br. Educ. Res. J. 37, 813–828. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

Haque, M. A., Salwa, M., Sultana, S., Tasnim, A., Towhid, M. I. I., Karim, M. R., et al. (2022). Parenting stress among caregivers of children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. J. Intellect. Disabil. 26, 407–419. doi: 10.1177/17446295211002355

Hebron, J. (2017). “The transition from primary to secondary School for Students with autism Spectrum conditions” in Supporting social inclusion for students with autism Spectrum disorders. ed. C. Little. 1st ed (London, UK: Routledge), 84–99.

Hughes, J. M. (2016). Increasing neurodiversity in disability and social justice advocacy groups. Washington, DC: Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

Koegel, R. L., Kim, S., Koegel, L. K., and Schwartzman, B. (2013). Improving socialization for high school students with ASD by using their preferred interests. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 2121–2134. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1765-3

Koegel, L. K., Robinson, S. E., and Koegel, R. L. (2009). Empirically supported intervention practices for autism Spectrum disorders in schools and community settings: issues and practices. Issues Clin. Child Psychol. 2, 149–176.

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teachers Teaching 23, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

Lim, E., Wong, S., Gurbuz, E., Kapp, S. K., López, B., and Magiati, I. (2023). Autistic students’ experiences, opportunities and challenges in higher education in Singapore: a qualitative study. Educ. Sci. 13:818. doi: 10.3390/educsci13080818

Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Thomson, N., and Scott, H. (2013). Educators’ challenges of including children with autism Spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 60, 347–362. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470

Little, C. (2017). Supporting social inclusion for students with autism Spectrum disorders. 1st Edn. London, UK: Routledge.

Manalili, M. A. R. (2021). Ableist ideologies stifle neurodiversity and hinder inclusive education. Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture 3:6. doi: 10.9707/2833-1508.1072

Nieminen, J., and Pesonen, H. (2022). Anti-ableist pedagogies in higher education: a systems approach. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 19. doi: 10.53761/1.19.4.8

Reinholz, D. L., and Ridgway, S. W. (2021). Access needs: centering students and disrupting ableist norms in STEM. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 20:17. doi: 10.1187/cbe.21-01-0017

Ruble, L. A., Usher, E. L., and McGrew, H. H. (2011). Preliminary investigation of the sources of self-efficacy among teachers of students with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 26, 67–74. doi: 10.1177/1088357610397345

Sandland, B., MacLeod, A., and Hall, N. (2003). Neurodiverse students within higher education – initial thoughts from a collaborative project. Educ. Practice 4, 26–37.

Sasson, N. J., Faso, D. J., Nugent, J., Lovell, S., Kennedy, D. P., and Grossman, R. B. (2017). Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep40700

Keywords: neurodiversity, inclusion, perception, formal education, educational opportunities, challenges

Citation: Chowdhury SA, Islam MA, Nishat MTA, Nadiv MA and Ormi NJ (2024) Navigating inclusion: understanding social perception, educational opportunity, and challenges for neurodiverse students in Bangladeshi formal education. Front. Educ. 9:1452296. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1452296

Edited by:

Huichao Xie, University College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

April Hargreaves, National College of Ireland, IrelandGerardo Aguilera Rodríguez, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

Copyright © 2024 Chowdhury, Islam, Nishat, Nadiv and Ormi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sabbir Ahmed Chowdhury, c2FiYmlyLmFobWVkQGR1LmFjLmJk; Mohammad Ashraful Islam, YXNocmFmLmlzbGFtQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1

Sabbir Ahmed Chowdhury

Sabbir Ahmed Chowdhury Mohammad Ashraful Islam3,4*

Mohammad Ashraful Islam3,4* Md. Tahmid Anjum Nishat

Md. Tahmid Anjum Nishat Md. Adnan Nadiv

Md. Adnan Nadiv