- Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

While two-thirds of Black principals are female, the extant research on Black female principals is almost entirely qualitative. Using data from the 2017–2018 National Teacher and Principal Survey (n = 7,170 with 450 Black female principals) and the 2011–2012 Schools and Staffing Survey (n = 7,510, with 360 Black female principals), we quantitatively examine the career paths, reported influence, and reported time use of Black female principals compared to other principals. Black female principals are relatively less likely than Black male principals to have experience as athletic coaches, and less likely to have non-education management experience. Relative to non-Black female principals, Black female principals are less likely to have experience as curriculum directors. Relative to other principals, Black female principals generally report having comparable influence over their schools, while spending somewhat more time on parent interactions, suggestive of roles representing minority parents. We discuss implications and directions for future research.

Introduction

Practical politicians have long recognized the value of having public officials who resemble their communities demographically (Riordan, 1905). Since at least the 1967 publication of Pitkin’s (1967) The Concept of Representation, social scientists and public administrators have understood possible organizational and societal benefits of having demographically diverse public employees. A more diverse public sector likely increases government legitimacy and facilitates broader human capital pipelines and thus greater overall talent, assuring greater administrative knowledge of those served. A substantial literature suggests such benefits in a range of public organizations (Brudney et al., 1998) including schools (Leal and Meier, 2010; Meier and Rutherford, 2017), though some question the extent and causal direction of certain findings, and warn that context matters (Nielsen and Wolf, 2001).

This paper has four parts. First, we review the qualitative literature on Black female principals. Indeed, there is little quantitative examination about general trends and the experience of Black female principals, though researchers are beginning to fill the gap. Even so, with few exceptions, these studies do not center Black female principals as we do here (Fuller et al., 2019; Bailes and Guthery, 2020; Jang and Alexander, 2022). Second, we describe the two data sets used for quantitative examination of various questions regarding Black female principals nationally. Third, we compare the career trajectories, reported influence over school operations, and reported weekly on-the-job time use of Black female principals relative to non-Black male,1 non-Black female, and Black male peers. These comparisons allow us answer the question of whether and how the experience of Black female principals are different from other principals. Findings indicate many similarities across demographic groups regarding influence over schools, suggesting the importance of bureaucratic role (Downs, 1967). However, we also found evidence for distinctive career trajectories and leadership roles among Black female principals. Black female principals report more influence over establishing curriculum, teacher evaluation, and school budgets compared to non-Black male principals. We also find that Black female principals have somewhat less teaching experience than non-Black female principals but much more teaching experience (meaning slower promotion into leadership) than Black male principals. Compared to Black males, Black female principals are slightly more likely to have experience as curriculum specialists, and considerably less likely to have experience as athletic coaches. Black female principals additionally report spending less time on internal administrative tasks and more time interacting with parents relative to non-Black female principals, suggestive of roles representing minority parents, as prior literature suggests (Irby, 2021). Relative to both non-Black female and Black male peers, Black female principals spend somewhat more time on curriculum and teaching-related tasks such as lesson preparation, classroom observations, and mentoring teachers. In the concluding fourth section, we discuss the implications of our findings and suggest directions for future research.

Literature review: the roles and impacts of Black principals

There is a substantial qualitative literature on the roles of Black principals as both educators and community leaders. Rich historical scholarship examines Black principals leading schools in Black communities, in some cases enabling students to overcome daunting obstacles imposed by racist public policies and public attitudes. A key theme of this literature is that Black leaders tend to have more personal and cultural knowledge of, caring for, and credibility within Black communities. They can thus bring community resources to partly compensate for inadequate public resources, including better communication enlisting the efforts of Black parents and students. Generally, such leaders have lacked material resources, but brought greater cultural and relational resources (Sowell, 1974; Ladson-Billings, 1994; Siddle Walker, 1996; Buck, 2010; Rousmaniere, 2013; Crow and Scribner, 2014). Some work, such as the extended case study of Marcus Foster by Spencer (2012) (see also Foster, 1971) offers examples of Black principals serving as education innovators in Black communities. These efforts include extending educational services to parents, while also pressing white power structures for much needed material resources. A more recent, largely quantitative literature offers evidence that Black students may have more success under Black teachers, likely for the same reasons (Easton-Brooks, 2014; Egalite et al., 2015; Gershenson et al., 2016). Other recent research suggests that Black principals have relatively more success in recruiting and retaining Black teachers (Bartanen and Grissom, 2019).2

A largely historical literature details the positive impacts of Black educational leadership in segregated school systems. Buck (2010), Peters (2019), and perhaps most notably Siddle Walker and Byas (2009) explain that prior to desegregation, Black teachers and principals enjoyed revered roles in Black communities. After the 1954 Brown case deemed racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, the process of desegregation was implemented by all-white school boards and public bureaucracies. Typically, Black schools were closed, with Black students bused to white schools where they were not always welcomed. In the resulting school consolidations, Black principals were fired or demoted to classroom teachers, while many other Black teachers lost their jobs and left the teaching profession altogether (Thompson, 2019). Buck (2010), Peters (2019), and more recently Fenwick (2022) argue that Black education has never recovered from what the latter calls “Jim Crow’s pink slip.”

The special roles of Black female leaders

Notably, educational leadership positions are not only in part racially determined; but they are also gendered. Before the early 1900s, large numbers of public education leaders were female, as were and are most teachers. As part of “professionalizing” educational leadership at a time when professional meant male, the early 20th century progressive school reformers attracted more males to school leadership. This arose through the development of educational leadership graduate programs and an emphasis on secondary school athletic programs, with coaching serving as a masculine way to enter the education profession and a stepping-stone to principal and eventually superintendent posts (Rousmaniere, 2013). Considerable research indicates that these patterns persist, and indeed, that school boards and many public educators are comfortable with gendered workplace norms. Related work indicates that while teachers are overwhelmingly female, secondary principalships, which are the dominant paths to superintendent, remain overwhelmingly male (Maranto et al., 2018a). Males are promoted more quickly than females. Further, most male principals and an even greater percentage of male superintendents are former coaches, which may influence their priorities as leaders. In contrast, relatively few female principals are former coaches, but a large minority have curriculum backgrounds (Maranto et al., 2018b). These differences in background may partly explain findings that female superintendents seem to improve measured academic outcomes for students generally, though the impacts are modest (Meier et al., 2006; Johansen, 2007).

Since Crenshaw (1991), scholars have studied the mutually reinforcing impacts of overlapping categories of disadvantage like race and gender. Yet social science has produced remarkably little research on the motivations, roles, career trajectories, and impacts of Black female leaders, likely since they remain a relatively small percentage of United States educational leaders, resulting in small sample sizes. Further, school leadership researchers and feminist theorists are predominately white, and less likely to focus on minority communities (Tillman, 2004). Notable exceptions exist. Collins (1989) and Dillard (1995) argue that Afrocentric values like family and religion and shared experiences with oppression form a distinct, intersectional identity for Black women, shaping their leadership. In particular, awareness of pressing student and limited resources lead Black female principals to persevere in creating opportunities for students.

Bass (2009, 2012) asserts that Black female educational leaders with a natural orientation toward caring embody tenets of Black feminist caring (BFC) theory, characterized by maternal approaches to student interactions. These principals were more likely to have admitted to breaking rules to attain what their students needed. This tenet of the framework is shaped by Black women’s experiences with and exposure to multiple levels of societal oppression, as well as their relative religiosity. In more recent qualitative work, Bass (2020) suggests that such approaches may also characterize Black male principals.

In a pathbreaking review of the research on the leadership of Black female principals, Lomotey (2019) reports that this work is entirely qualitative, 57 case studies and comparative case studies from 1993 to 2017. Only one study had a sample size greater than 14; a plurality studied just three leaders. Most were unpublished doctoral dissertations. Reviewing this body of work, Lomotey (2019) reports that most studies found race and gender related issues having roughly equal importance, that spirituality played an important role in leadership—as is suggested in Collins (1989) and Dillard (1995), that many Black female principals could be categorized as servant leaders—as is suggested in Bass (2009) and Jean-Marie et al. (2009), and that principals deployed distinct leadership styles in integrated and segregated settings. Most authors employed either Critical Race Theory or Black Feminist Thought to frame the questions asked and eschewed quantification, a tendency of Critical Race Theory generally (Gillborn et al., 2017). This indicates a large gap in the literature.

Fortunately, researchers are beginning to fill the gap (Lomotey, 2019) identified, albeit primarily with Texas data rather than national data, in part reflecting data availability. Using Texas data on assistant principals (n = 4,689), Bailes and Guthery (2020) find that both Black and female assistant principals must have more years of experience to be promoted to principal. Further, controlling for qualifications and experience, they are less likely to be promoted. Notably, the impacts are roughly constant on both the elementary and secondary levels. Likewise, using a time series analysis of 25 years of Texas employment data, Fuller et al. (2019) reach the same findings, even in the face of growing diversity among both principals and assistant principals. Using 23 years of Texas data, Fuller et al. (2018) find that for female assistant principals, promotion to principals is somewhat less likely in rural locations.

Recent work by Jang and Alexander (2022) goes beyond Texas and also systematically explores the impact of Black female leaders, using a 2009 national high school survey from the National Center for Education Statistics to analyze a small sample of Black female secondary principals (n = 26) within a much larger sample of secondary principals (n = 925), finding that they were relatively more likely to serve schools with a greater percentage of students of color, more likely to practice instructional leadership, and somewhat more likely to be associated with somewhat higher math achievement for all students. These findings accord with the broader literature on Black female principals.

To further fill the gap identified by Lomotey (2019) to ascertain whether patterns from qualitative case studies are generalizable to larger, representative samples, here we conduct quantitative national comparisons of Black female principals with Black male principals as well as male and female non-Black principals. We use national survey data to explore career trajectories, reported influence over school operations, and time management in ways to extend the findings qualitative documented by Lomotey (2019).

Research methods

Data

We employ data from the 2017–2018 National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS) and the 2011–2012 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS). NTPS and SASS are the primary national data collection efforts from the National Center for Education Statistics at the U.S. Department of Education to better understand public and private schools, principals, and teachers. Both of these surveys are administered via mail and the internet. SASS was administered every 4 years between 1999 and in 2011 was replaced by the NTPS beginning in the 2015–2016 school year. To obtain this data, a random sample of the population of public schools across the United States was selected to complete the questionnaires. Sampling weights are used to correct for nonresponse bias so the data are nationally representative. The National Center for Education Statistics also samples private schools for NTPS and SASS, but they are excluded from our analysis. Principals, teachers, and district office administrators participating in NTPS and SASS are asked to complete a series of questionnaires that ask their opinions, and a variety of contextual details about their school. For instance, district office administrators report on district-level characteristics such as their student population’s demographic composition, and teachers report personal information such as their pre-service training experience, professional experience, working conditions, job satisfaction, and school climate.

We use data obtained from the questionnaires administered to principals. Participating principals reported on their own backgrounds in education, such as years of teaching experience before becoming a principal, whether they have received professional development in a program designed to prepare aspiring principals, and the various positions held prior to becoming principal. They also responded to questions about their school as well as their own demographic characteristics. Although NTPS contains the most recent information about a nationally representative sample of U.S. principals, some items originally included in the SASS questionnaires were omitted from the NTPS questionnaires. For this reason, we rely on both data sets to describe the career trajectories and workplace norms for principals. In short, we leverage the comparative advantage of each data set. SASS enables us to rely on a wider range of descriptive information to investigate more aspects of the Black female principal leadership role, while NTPS provides a more updated view albeit on a slightly narrower set of items.

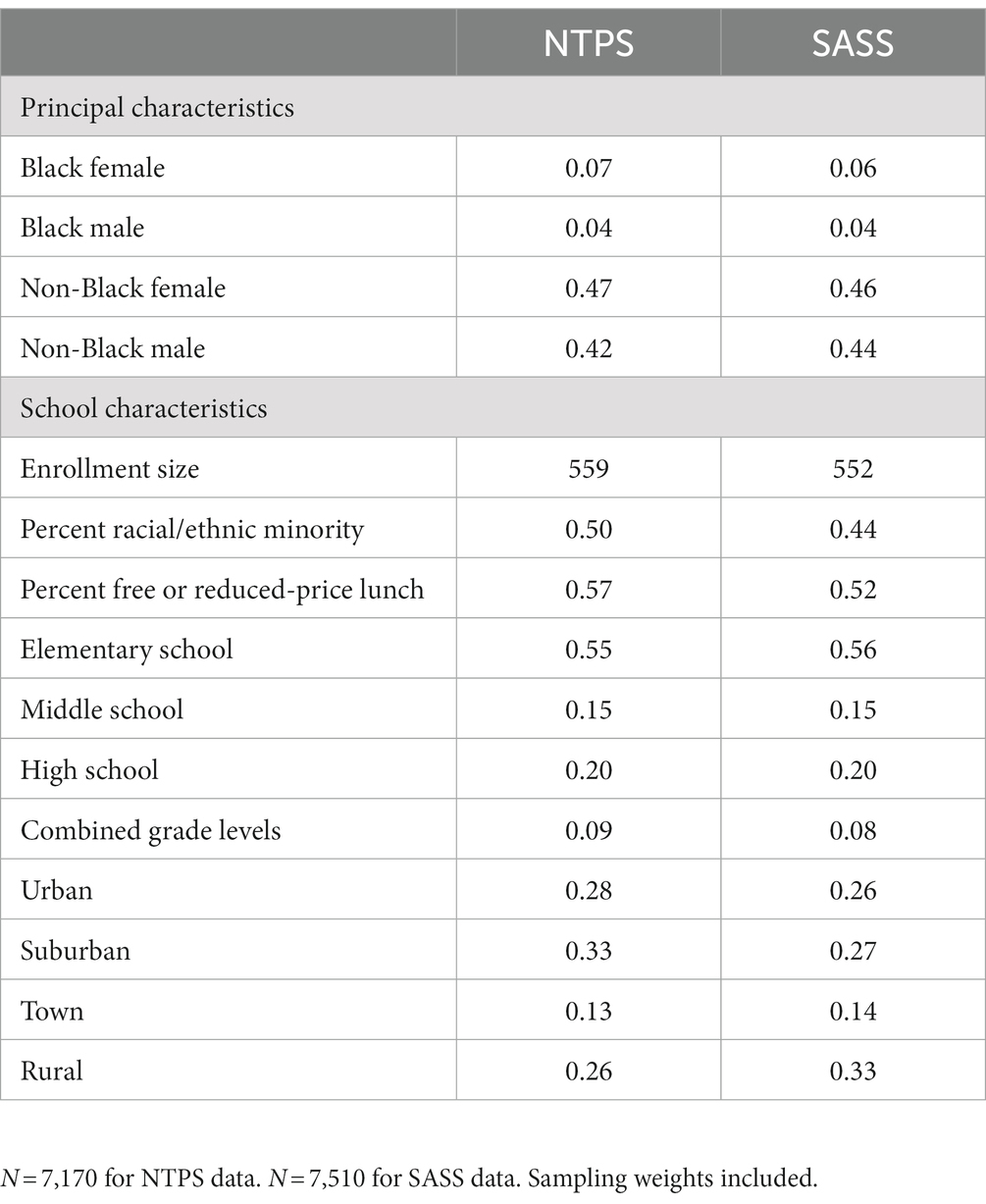

Our analytic sample from NTPS includes responses from 7,170 principals,3 of whom 450 identified as Black female principals. Our SASS analytic sample includes 7,510 principals, with 360 identified as Black female principals. Using sampling weights to adjust these raw counts, we observe that Black female principals make up 6 and 7 percent of United States principals, according to SASS and NTPS, respectively. Additional information about our principal samples and their schools appears in Table 1. Summary statistics are quite similar across the two datasets, even though they were obtained 6 years apart, perhaps indicating the relative demographic stability of educational leadership as a field.

Dependent variables

We use linear or logistic regression techniques, depending on whether the dependent variable is continuous or binary, to describe principals’ career trajectories and other school-based workplace norms by principal race and gender. We focus on four groups of dependent variables. First, we consider the length of time it takes for principals to rise to their administrative post. Second, we examine whether principals held other administrative positions before becoming the head administrator. Third, to consider differences in workplace norms, we report the extent of influence that principals feel they have over school operations. Finally, we describe how principals use their time during a typical workweek.

We use continuous variables for each principals’ years of prior teaching experience, years of principal experience, and age to describe the time it takes for them to rise to their current administrative post. Years of teaching experience provide an indicator for how long principals, on average, work as a teacher before promotion. Years of principal experience and the principals’ age provide a similar indicator for how rapidly they become promoted. These three variables are included in NTPS data.

Another way to describe principals’ prior career trajectories is to consider whether they held different middle-manager positions before promotion to principal. On the SASS questionnaires, principals reported whether they served in a variety of roles prior to becoming principal. These include department chair, athletic coach, curriculum specialist, student club advisor, and assistant principal. These variables are entered as indicator variables in our models, taking on a value equal to 1 if the principal has served in the specified capacity and 0 otherwise.

To analyze the influence principals feel they have over school operations, we rely on a series of questions from the NTPS where principals were asked to indicate whether they had “no influence,” “minor influence,” “moderate influence,” or “major influence” over seven operational tasks: setting performance standards at the school, establishing the school’s curriculum, determining the content of professional development programs for teachers, evaluating teachers, hiring teachers, setting school discipline policy, and deciding how to spend the school budget. For each item, we generated a dummy variable that takes on a value equal to 1 if the principal indicated they had “major influence” and 0 otherwise.

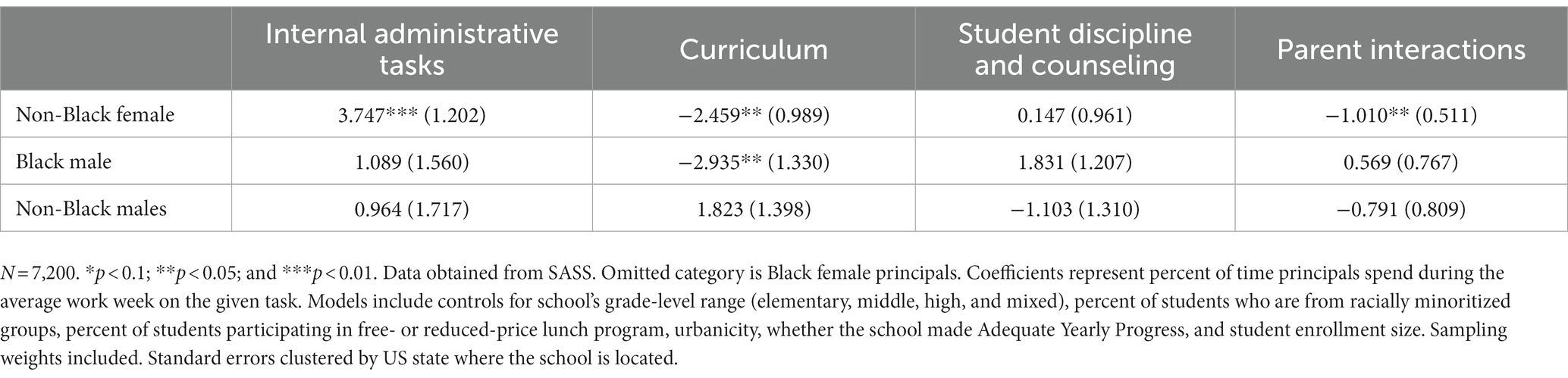

The final set of dependent variables provides indications of how principals use their time throughout the week. These data are obtained from SASS. On the questionnaires, principals estimated the percent of time they spend on four job duties during an average workweek: Internal administrative tasks (e.g., human resources, personnel management, budget, and reports), curriculum and teaching (e.g., lesson preparation, classroom observations, and mentoring teachers), student discipline and interactions, and parent interactions. We entered these variables as continuous variables in our regression models.

Independent variables

On the right-hand side of the regression equation, we include a variety of independent variables to model principal and school-level characteristics. Specifically, we include two dummy variables to indicate whether the principal is male and non-Black, respectively. We also include a third dummy variable, the interaction of these two terms. Together, these three dummy variables allow us to consider differences by race and gender simultaneously in describing the career trajectories and workplace norms of Black female principals relative to all other principals. School-level characteristics included in our model consist of the school grade-level range (elementary, middle, high, and mixed), percent of students from racially minoritized groups, the percent of students participating in free- or reduced-price lunch program, school urbanicity, and school enrollment. In the models based on SASS data, we additionally control for whether the school meet Adequate Yearly Progress according to their state accountability system. Data about whether a school met Adequate Yearly Progress, or any other measure of student achievement, is not available in NTPS.4

It is important to account for differences in these school-level characteristics as the distribution of principals by gender and race is not random. For instance, females tend to be principals in elementary schools, while males tend to be principals in middle and high schools (Maranto et al., 2018a). About 61 percent of elementary school principals are female, and about 72 percent of high school principals are male, according to SASS data. The distribution of principals’ gender across primary and secondary schools is similar in the NTPS data. Similarly, Black principals are more likely to serve schools in urban areas (Taie and Lewis, 2022). By comparing male, female, Black, and non-Black principals, while holding racial makeup of the student body, urbanicity, school level, and other school characteristics constant, our models account for ways that the non-random distribution of principals potentially confound our results.

Empirical model

Formally, we can express our model, which is estimated using linear or logistic regression techniques, as

where Yi is the particular dependent variable of interest, Malei and NonBlacki are indicator variables for the gender and race of principal i, and Xi is a vector of the school-level characteristics as described earlier. The idiosyncratic error term, which we cluster by US state because principals from the same state may share certain characteristics, is represented by ϵi. Note that Black female principals represent the omitted category according to our specification. In other words, β1, β2, and β3 are differences between Black female principals and Black male principals, non-Black female principals, and non-Black male principals, respectively. Sampling weights are included in all model estimates to account for missing data so that the results retain a nationally representative interpretation. In models where we rely on logistic regression, we present the results as marginal changes in probability for ease of interpretation.

Results

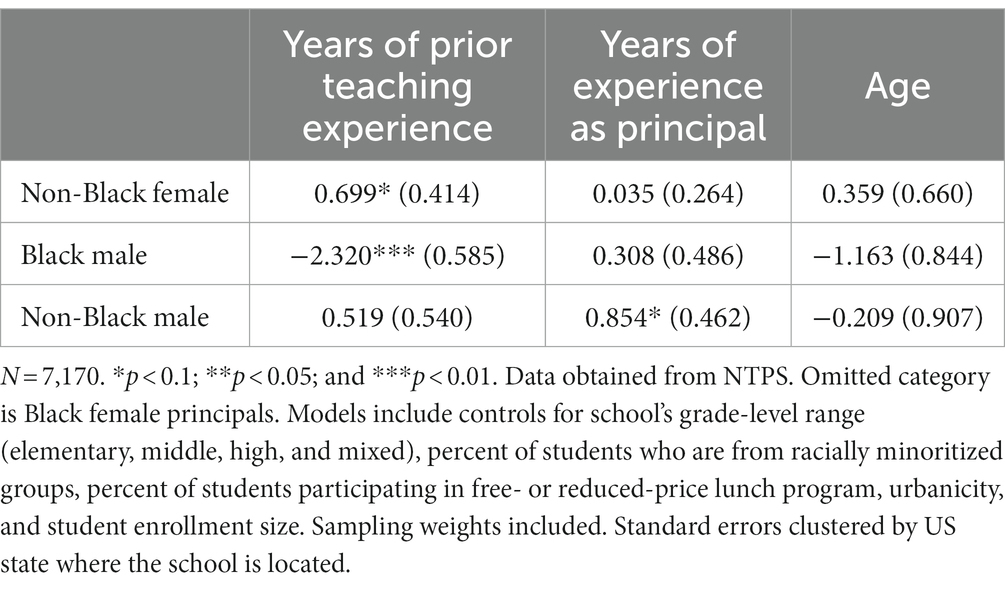

As Maranto et al. (2018b) show, female principals generally have slower promotion into administration and thus more teaching experience than male counterparts. Results in Table 2 show Black female principals occupying a middle ground between non-Black principals and Black male principals regarding speed of promotion. Black female principals have 0.7 more years of teaching experience compared to non-Black female principals but over 2 fewer years of teaching experience compared to Black male principals. This 2-year difference between Black female principals and Black male principals is substantial given that the average length of time, according to the data, that principals spend as a teacher is 11 years with a standard deviation of about 6 years. This difference of 2 years is statistically significant at the 0.01 level. In contrast, the difference between Black female principals and non-Black female principals is far smaller, marginally significant at the 0.1 level.

As shown in the second column of Table 2, there is some evidence that non-Black male principals have longer tenures as principals by about 0.9 years, a difference that is marginally significant at the 0.1 level. Regarding age, we did not find differences between Black female and other principals, as shown in column 3 of Table 2.

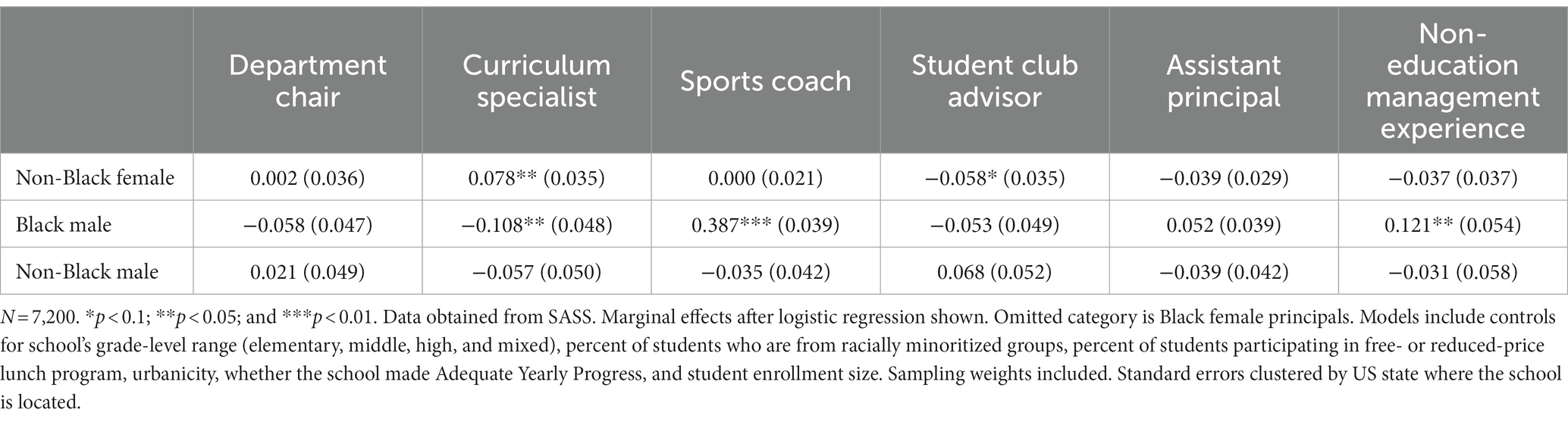

Regarding prior experience before becoming principals, Black female principals are distinct from their counterparts in several ways. First, as Table 3 shows, non-Black female principals are about seven percentage points more likely to have served as a curricular specialist compared to Black female principals, a result statistically significant at the 0.05 level. It is also substantively significant as only one quarter of all principals in the sample reported serving as a curricular specialist before becoming principal. In contrast, non-Black male principals are about 6 percentage points less likely than Black female principals to have served as a curricular specialist, though this result is not statistically significant. Meanwhile, Black male principals are 10 percentage points less likely than Black female principals to have served as a curricular specialist before becoming principal, a result statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Black female principals are much less likely than Black male principals to have served as athletic coaches—by a substantial 39 percentage-point margin. Considering that 36 percent of principals in the entire sample had prior coaching experience, this is a large difference. Given the leadership roles of coaches in United States schools generally, where they sometimes prioritize athletic missions and staff (Maranto et al., 2018a), we believe this could hint at the broader servant leadership orientations noted by Bass (2009, 2012) and the broad review by Lomotey (2019), though to repeat, this is at best an indirect measure of behavior.

There are only two other major distinctions between Black female principals and other principals revealed by our analysis of prior leadership positions. First, Black female principals are six percentage points more likely than non-Black female principals to serve as an advisor for student clubs. We speculate that this may cohere with the community-building role identified in qualitative accounts. Second is the lower likelihood of having prior management experience outside education compared to Black male principals. Specifically, Black male principals are 12 percentage points more likely than Black female principals to have such management experience prior to becoming principal. This difference is also substantively large given that 40 percent of all principals in the sample have had such experience.

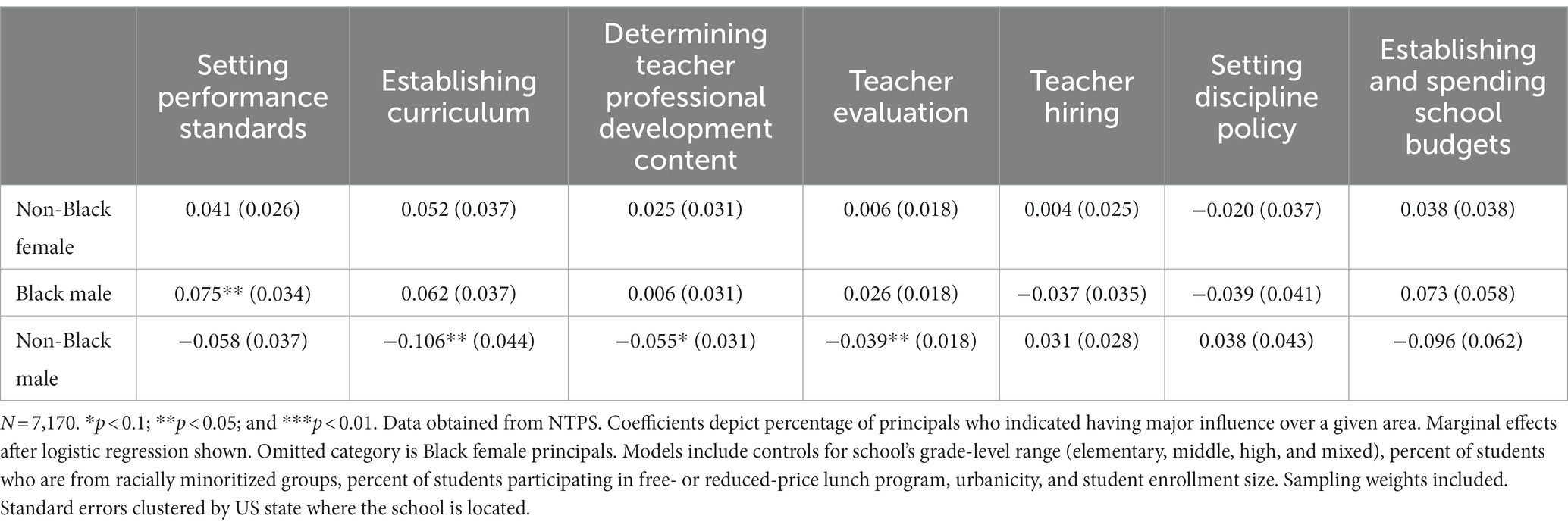

We now turn to our third set of results, reported influence over school operations. As shown in Table 4, Black female principals generally resemble other female principals. In contrast, as shown in the second row of Table 4, Black male principals appear to report more influence over setting performance standards and establishing or spending school budgets relative to Black female principals. Black male principals are about eight percentage points more likely to report having “major influence” over those areas. Notably, Black male principals are six percentage points more likely than Black female principals to say they have “major influence” over establishing curriculum (see Column 2 of Table 4). The coefficient estimate is sizeable but not statistically significant.

The last row of Table 4 compares non-Black male principals to Black female principals. Generally, non-Black male principals are less likely to report having “major influence” across most areas of school operations, as indicated by the negative point estimates. However, only in the areas of establishing curriculum, determining teacher professional development content, and teacher evaluation are those differences statistically significant and substantively large. Notably, these three areas are primarily concerned with directly supporting teaching and learning in the classroom. For instance, non-Black male principals are 11 percentage points less likely to report having “major influence” over establishing curriculum compared to Black female principals. They also are about six and four percentage points less likely to report having “major influence” relative to Black female principals regarding determining professional development content for teachers and teacher evaluation, respectively. As shown in the last column of Table 4, we observe that non-Black male principals are nearly 10 percentage points less likely to report having “major influence” over establishing and spending school budgets relative to Black female principals. The difference is sizeable but not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Finally, Table 5 reports differences in the amount of time that principals report spending on particular tasks during a typical workweek. Black female principals report spending about 2–3 percent more of their time each week on curricular matters, though the estimate of the difference with respect to non-Black male principals is not statistically significant. In two other respects, Black female principals report time usage in ways different from non-Black female principals. While non-Black female principals spend about 4% more of their workweek on internal administrative tasks compared to Black female principals, the former appear slightly less likely than the latter to spend time interacting with parents relative to the latter.

Discussion and conclusion

In the wider educational leadership literature, there is no clear consensus on how to predict who will be a strong principal; indeed, this may vary across communities (Lynch, 2012). Still, it is important to research identity-related mechanisms such as race and gender, both qualitatively, but also quantitatively as we do here. Black female principals have had a vital historical role in the leadership of public schools in Black communities, well documented in the literature (Ladson-Billings, 1994; Siddle Walker, 1996; Rousmaniere, 2013). This paper aims to fill the quantitative gap by reporting their self-reported roles in their schools.

As for experience, results reveal that compared to their Black male peers, Black females have almost two more years of teaching experience and are more likely to have experience as a curriculum specialist, but less apt to have experience coaching, and in management outside of education. The lower likelihood of promotion and longer tenures as teachers prior to becoming a principal are reflective of research findings of Texas schools (Fuller et al., 2019; Bailes and Guthery, 2020). Additionally, Black females report more influence over curricula development than their male peers. Both Black female and male principals report spending more time than their non-Black male counterparts on curriculum, perhaps reflecting Black community needs to gain representation in curricula, a matter of longstanding concern (Foster, 1971; Spencer, 2012).

Like Black male principals, Black female principals spend somewhat more time than non-Black principals on parental interactions, hinting at possible representational roles for the traditionally marginalized, and at servant leadership roles, as suggested in some of the studies chronicled by Lomotey (2019). That said, we should not overstate statistically modest findings. Possibly, the commonalities of training, the conditions of particular schools, and the policies of an era matter more than race and gender in shaping behavior: these may have more explanatory power than demographics (Payne, 2008; Rousmaniere, 2013). Broadly, these results beg for further research, including regarding student academic and disciplinary outcomes.

Moreover, future work should consider more closely the interactions between student body demographics and principal demographics. With few exceptions, gender ratios vary little across public schools, while racial and ethnic demographics vary substantially. It seems likely that Black female leaders would play different roles depending on the demographic characteristics of the schools they serve, and the underlying racial dynamics within those schools. For example, qualitative work by Irby (2021) indicates that in traditionally white schools with increasing numbers of minorities, the representational role of minority leadership in translating perceptions and needs can be both important and demanding, in sharp contrast to a school with integrated but less dynamic demographics (e.g., Easton-Brooks, 2012).

Generally, we hope this paper fosters additional quantitative research to supplement existing qualitative studies, to build more representative models of how Black female leadership works inside public schools. In particular, future quantitative work should explore how race and gender interact with school demographics, and possible impacts on quantitative indicators of achievement and attainment. Given the gendered nature of school leadership, where elementary school principals tend to be female and secondary principals tend to be male, it would be valuable to compare the experience of Black female elementary school principals to the experience of Black female secondary school principals. The experiences of these two groups of principals are likely distinct and understanding those differences will be a valuable contribution to the knowledge base of the school leadership literature. Our sample sizes of Black female secondary school principals was too low to make such an inquiry, but we encourage future research to address the topic.

Empirical research should also include survey questions on such matters as religiosity and spirituality (Lomotey, 2019), career objectives and ambition (Carroll, 2016; Maranto et al., 2018b), and values and behaviors regarding race and gender. To advance knowledge and ultimately equity, we must better understand the degree to which demographic representation shapes policies and practices inside schools, where principals are the key decision-makers. In Black communities, many of those principals are Black females, whose contributions have only recently been studied and appreciated by researchers (Lomotey, 2019). Regarding Black female principals, far more research is needed.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: data access requires a license with the Institute of Education Sciences/National Center for Education Statistics of the US Department of Education. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/licenses.asp.

Author contributions

AC, EC, and RM contributed equally to the data analysis and writing of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The central issue of our study is the career trajectories of Black, female principals. We, therefore, compare Black female principals to all other principals, and use the term non-Black to refer to principals who have a racial identity other than Black (White, Asian, etc.)

2. ^That said, we must acknowledge that this literature is not universally positive, with Black activists like a young Barack Obama (1995, p. 255-57) and Black scholars including Rich (1996) and Payne (2008) suggesting that Black educational administrators often resemble their white counterparts, using positions as patronage, or by taking bureaucratic rather than community empowerment roles.

3. ^All sample sizes are rounded to the nearest 10 place per data-use agreement with the United States Department of Education.

4. ^Whether or not we control for whether a school met Adequate Yearly Progress in models using SASS data does not materially change the results. We, therefore, suspect that the inability to control for whether a school met Adequate Yearly Progress in models using NTPS data does not bias our results because of the lack of such a variable.

References

Bailes, L. P., and Guthery, S. (2020). Held down and held back: systematically delayed principal promotions by race and gender. AERA Open 6:233285842092929. doi: 10.1177/2332858420929298

Bartanen, B., and Grissom, J.A. (2019). School principal race and the hiring and retention of racially diverse teachers. Annenberg Institute for School Reform, Brown University, Providence.

Bass, L. (2009). Fostering an ethic of care in leadership: a conversation with five African American women. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 11, 619–632. doi: 10.1177/1523422309352075

Bass, L. (2012). When care trumps justice: the operationalization of black feminist caring in educational leadership. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 73–87. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647721

Bass, L. R. (2020). Black male leaders care too: an introduction to black masculine caring in educational leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 56, 353–395. doi: 10.1177/0013161X19840402

Brudney, J. L., Kellough, J. E., and Selden, S. C. (1998). Bureaucracy as a representative institution: toward a reconciliation of bureaucratic government and democratic theory. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 717–744.

Carroll, K. (2016). Ambition is priceless: socialization, ambition, and representative bureaucracy. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 47, 209–229. doi: 10.1177/02750740166716

Collins, P. H. (1989). The social construction of black feminist thought. Common Ground. Crossroads Race Ethnicity Class Women’s Lives 14, 745–773. doi: 10.1086/494543

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43:1241. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Crow, G. M., and Scribner, S. P. (2014). “Professional identities of urban school principals” in Handbook of Urban Education. eds. H. R. Milner IV and K. Lomotey (New York: Routledge Press), 287–304.

Dillard, C. B. (1995). Leader with her life: an African American feminist (re)interpretation of leadership for an urban high school principal. Educ. Adm. Q. 31, 539–563. doi: 10.1177/0013161X9503100403

Easton-Brooks, J. S. (2012). Black School, White School: Racism and Educational (mis)leadership. New York: Teachers College Press.

Easton-Brooks, D. (2014). “Ethnic-matching in urban schools” in Handbook of Urban Education. eds. H. R. Milner IV and K. Lomotey (New York: Routledge Press), 97–113.

Egalite, A., Kisida, B., and Winters, M. (2015). Representation in the classroom: the effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev. 45, 44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.01.007

Fenwick, L. T. (2022). Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Foster, M. A. (1971). Making Schools Work: Strategies for Changing Education. Philadelphia: Westminster Press

Fuller, E., Hollingworth, L., and An, B. P. (2019). Exploring intersectionality and the employment of school leaders. J. Educ. Adm. 57, 134–151. doi: 10.1108/JEA-07-2018-0133

Fuller, E. J., Pendola, A., and LeMay, M. (2018). Who should be our leader? examining female representation in the principalship across geographic locales in Texas public schools. J. Res. Rural. Educ. 34, 1–21.

Gershenson, S., Holt, S., and Papageorge, N. (2016). Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Econ. Educ. Rev. 52, 209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002

Gillborn, D., Warmington, P., and Demack, S. (2017). Quantcrit: education, policy, ‘big data’ and principles for a critical race theory of statistics. Race Ethn. Educ. 21, 158–179. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2017.1377417

Irby, D. J. (2021). Stuck Improving: Racial Equity and School Leadership. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Jang, S. T., and Alexander, N. A. (2022). Black women principals in American secondary schools: quantitative evidence of the link between their leadership and student achievement. Educ. Adm. Q. 58, 450–486. doi: 10.1177/0013161X211068415

Jean-Marie, G., Williams, V. A., and Sherman, S. L. (2009). Black women’s leadership experiences: examining the intersectionality of race and gender. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 11, 562–581. doi: 10.1177/1523422309351836

Johansen, M. S. (2007). The effect of female strategic managers on organizational performance. Public Organ. Rev. 7, 269–279. doi: 10.1007/s11115-007-0036-1

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leal, D., and Meier, K.J., (eds.) (2010). The Politics of Latino Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lomotey, K. (2019). Research on the leadership of black woman principals: implications for black students. Educ. Res. 48, 336–348. doi: 10.3102/0013189X19858619

Maranto, R., Carroll, K., Cheng, A., and Teodoro, M. P. (2018a). Boys will be superintendents: school leadership as a gendered profession. Phi Delta Kappan 100, 12–15. doi: 10.1177/0031721718803563

Maranto, R., Teodoro, M. P., Carroll, K., and Cheng, A. (2018b). Gendered ambition: men’s and Women’s career advancement in public management. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 49, 469–481. doi: 10.1177/0275074018804564

Meier, K. J., O’Toole, L. J., and Goerdel, H. T. (2006). Management activity and program performance: gender as management capital. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 24–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00553.x

Meier, K. J., and Rutherford, A.. (2017). The Politics of African American Education. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nielsen, L. B., and Wolf, P. J. (2001). Representative bureaucracy and harder questions: a response to Meier, wrinkle, and Polinard. J. Polit. 63, 598–615. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00081

Peters, A. L. (2019). Desegregation and the (dis)integration of black school leaders: reflections on the impact of “Brown v. Board of Education” on black education. Peabody J. Educ. 94, 521–534. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2019.1668207

Riordan, W. L. (1905). Plunkitt of Tammany Hall. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/plunkett-george/tammany-hall/

Rousmaniere, K. (2013). The Principal’s Office: A Social History of the American School Principal. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Siddle Walker, V. (1996). Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Siddle Walker, V., and Byas, U. (2009). Hello Professor: A Black Principal and Professional Leadership in the Segregate South. United States: University of North Carolina Press

Sowell, T. (1974). Black excellence: the case of Dunbar high. The public interest. Available at: https://nationalaffairs.com/storage/app/uploads/public/58e/1a4/ba6/58e1a4ba616e4230354245.pdf

Spencer, J.P. (2012). In the Crossfire: Marcus Foster and the Troubled History of American School Reform. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Taie, S., and Lewis, L. (2022). Characteristics of 2020–21 public and private K–12 school principals in the United States: results from the National Teacher and principal survey. National Center for Education Statistics, United States Department of Education, Washington, DC.

Thompson, O. (2019). School desegregation and black teacher employment [NBER working paper no. 25990]. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Keywords: Black principals, female principals, educational leadership, equity, diversity

Citation: Cheng A, Coady E and Maranto R (2023) The roles of Black women principals: evidence from two national surveys. Front. Educ. 8:1138617. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1138617

Edited by:

Margaret Terry Orr, Fordham University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennie Weiner, University of Connecticut, United StatesJudy Alston, Miami University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Cheng, Coady and Maranto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Albert Cheng, YXhjMDcwQHVhcmsuZWR1

Albert Cheng

Albert Cheng Emily Coady

Emily Coady Robert Maranto

Robert Maranto