- 1Department of Counseling, Educational Psychology and Special Education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2Department of Rehabilitation Psychology and Special Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

- 3UW School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

- 4Division of Special Education and Counseling, California State University, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 5Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, United States

- 6Department of Kinesiology and Community Health, University of Illinois—Urbana Champaign, Champaign, IL, United States

- 7College of Health Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, United States

We examined mediating effects of the pillars of well-being (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment) on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment for student veterans. We recruited 205 student veterans. Mediation analysis was conducted to test whether the pillars of well-being mediate the relationship between PTSD and college life adjustment. The results showed that positive emotion and accomplishment had mediating effects on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college adjustment.

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is very common disability among student veterans, with up to 45.6% of student veterans reporting PTSD symptoms (Rudd et al., 2011). PTSD may negatively impact student veterans’ well-being and, in turn, adjustment to college life (Elliot, 2015). However, relatively little is known about the relationships among PTSD, pillars of the well-being, college adjustment through the lens of contemporary theories.

The PERMA Theory of Well-Being is a contemporary theory explaining well-being with five core pillars: positive emotion (e.g., joy), engagement (e.g., flow), relationships (e.g., interpersonal relationships), meaning (e.g., purpose), and accomplishment (e.g., achievements) (Seligman, 2011). According to Seligman, well-being is not only the absence of mental illness (e.g., PTSD), it is also the presence of the five pillars of well-being (Seligman, 2011). The PERMA Model of Wellbeing was previously tested and evaluated in student veterans (Umucu, 2017; Umucu et al., 2020a). Umucu et al. (2020a) found that PERMA is a multidimensional construct to understand well-being in student veterans with and without disabilities. In addition, PERMA predicted college adjustment, physical and mental health quality of life, and life satisfaction in student veterans. In addition, PERMA was found to be positively associated with hope (Umucu et al., 2020b), optimism and resilience (Umucu et al., 2018), and negatively associated with depression and anxiety (Umucu et al., 2018). Yet, the relationship between PERMA and PTSD was not examined in student veterans.

PTSD could be a significant issue for wellbeing and college adjustment in student veterans. Barry et al. (2012) reported that PTSD is negatively linked to academic accomplishment. Elliott (2015) reported that PTSD was positively correlated with more frequent reports of troubling experiences at school, social tension, and lower GPA. Elliott (2015) explored the predictors of student veterans’ problems on campus and found that PTSD was positively correlated with dissatisfaction with college performance, financial hardship, more frequent reports of troubling experiences at school, and social tension (i.e., tension with veteran friends, criticism from veteran friends, and criticism from family). In the same study, researchers concluded that PTSD was negatively associated with social support from family and friends and with Grade Point Average (GPA). Rudd et al. (2011) explored the relationship between psychological symptoms and suicide risk and found that 82% of student veterans with PTSD experience at least one significant suicide attempt. In our recent study, we found that 1) functional limitations mediate the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college adjustment (Umucu et al., Forthcoming 2022) and 2) COVID-19-related stress mediated the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college adjustment in student veterans with PTSD symptoms (Umucu et al., under review1). Previous research clearly articulates that PTSD symptoms are associated with problems in well-being and college life adjustment for veterans.

So far, no studies, from our knowledge, have explored whether the pillars of well-being defined by Seligman (2011) mediate the negative impact of PTSD symptoms on college adjustment for student veterans. Given PERMA was found to be correlated with positive health and academic outcomes in student veterans, we wanted to test whether PERMA may mediate the relationship between the PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the extent that the pillars of well-being serve as mediators to explain the relationship between PTSD and college adjustment in student veterans so that our findings can inform rehabilitation, counseling, and mental health professionals. We hypothesized that each the pillars of well-being serve as a mediator for the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college adjustment in student veterans. Our mediation analysis findings may serve developing targeted interventions helping student veterans reduce negative impact of PTSD on their college adjustment.

Methods

A quantitative descriptive design, utilizing multiple mediation analysis, was used for the present study to determine whether PERMA may mediate the relationship between the PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment. Participants were recruited from higher education institutions following IRB approval from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. To recruit participants, we reached out student veteran offices in higher education institutions. Student veteran offices shared our survey link with student veterans. To be eligible for inclusion in the study, participants had to meet the following criteria: 1) at least 18 years or older; 2) retired from active-duty service or a National Guard or Reserve member of the United States Armed Services with active-duty service, and 3) currently enrolled in a college or university. Each participant filled out an online consent form before starting our survey. Participants were offered a $15 gift card. This data is a part of a larger cross-sectional dissertation study (blinded). Data were collected via an online survey platform. Our participants were informed of the voluntary nature of our research, their rights as a research participant, and the potential effects and benefits from participating in our study.

PTSD symptoms were measured by 4-item PC-PTSD screen (Prins et al., 2003). We used the scale as a continuous measure of PTSD symptom. The five pillars of well-being (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment) were measured by the PERMA-Profiler (Butler and Kern, 2016). The scale was reported to be reliable and valid by Butler and Kern (2016). College life adjustment was measured by a generated college life adjustment score based on the four subscales of the Inventory of Common Problems (ICP; Hoffman and Weiss, 1986) and the PHQ-4 (Kroenke et al., 2009). The four subscales of the ICP are composed of 16 items: academic problems, interpersonal problems, substance use problems, and physical health problems. The PHQ-4 is a 4-item measure of depression and anxiety. After negatively worded items were recoded, we summed up the standardized values of the ICP and the PHQ-4 to generate a college life adjustment score, with higher scores indicating a better college life adjustment.

Multiple mediation analysis using PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2013) was conducted to explore whether the pillars of well-being (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment) mediate the relationship between PTSD and college life adjustment. In addition, bootstrap test (5000 bootstrap samples; 95% CI) for multiple mediators was used to test the indirect effects of the PTSD on the college life adjustment through the mediators (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). We decided to conduct multiple mediation given the PERMA model has five different pillars.

Results

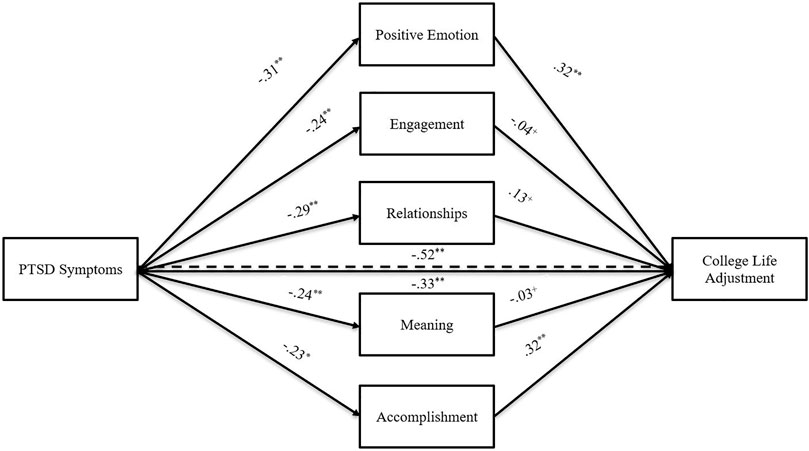

Participants consisted of 205 student veterans, with a mean age of 29.3 (SD = 8.0). The majority of sample was male (71.7%), Caucasian (80.5%), and employed (59.0%). The association between PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment was negative and significant: β (95%CI) = −0.52 (−0.64, −41). PTSD symptoms were negatively and significantly related to positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment: βs (95% CIs) = −0.31 (−0.45, −0.18), −0.24 (−0.38, −0.11), −0.29 (−0.42, −0.16), −0.24 (−0.40, −0.10), and −0.23 (−0.36, −0.09), respectively. Two of the five putative mediators were significantly associated with the college life adjustment, βs (95%CIs) = 0.31 (0.13, 0.51) for positive emotion and 0.32 (0.19, 0.46) for accomplishment, while statistically controlling for the PTSD symptoms. The model accounted for 63% of the variance in college life adjustment, R =0.795, R2 = 0.63, F (6,198) = 57.02, p <0.001. The β for PTSD symptoms were reduced from −0.52 to −0.33 after controlling for the effect of the mediators. Thus, although the intervening variables helped to explain the link between PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment, they did not completely explain the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college life adjustment. Finally, bootstrap test revealed significant indirect effect of the PTSD symptoms on the college life adjustment through the mediators (abpositiveemotion [95%CI] = −0.10 [−0.19, −0.04] and abaccomplishment [95%CI] = −0.07 [−0.14, −0.03]). Please see Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Multiple Mediation Model Examaining the Relationship Between PTSD Symptoms and College Life Adjustment. Note. Dotted line denotes the effect of PTSD Symptoms on college life adjustment when mediaters are not included *p

Discussion

Congruent with previous research (e.g., Barry et al., 2012; Elliott, 2015), our findings revealed that student veterans with PTSD symptoms had poorer adjustment to college life. Our results also suggested that PTSD symptoms were negatively associated with well-being. Conversely, student veterans who endorsed higher scores in the pillars of well-being demonstrated higher scores in adjustment to college life.

Our analysis revealed that positive emotion and accomplishment served as mediators explaining the relationship between PTSD symptoms and college adjustment in student veterans. The results are consistent with previous research suggesting that positive emotion helps people construct desirable outcomes, which further engenders successes across other life domains (Cohn et al., 2009). Despite living under stress, individuals with positive emotion are more likely to 1) focus on the “good”, 2) develop problem-solving skills, and 3) create positive meaning in life events (Folkman and Moskowitz, 2000). Additionally, having a sense of accomplishment is important as individuals make progress towards their goals (Butler and Kern, 2016). Previous research has also revealed that accomplishment in social roles was associated with numerous positive outcomes including higher well-being (Levasseur et al., 2010).

Student veterans may face with many adverse internal and external stressors due to transition-related challenges, academic-related challenges, disability-related stressors, and more on (Umucu et al., 2019). Transition from military to civilian life can be very challenging and demanding for veterans, especially for those with disabilities, which causes significant distress and challenges for veterans. For example, many veterans may experience mental illness, pain, suicidal ideation, functional limitations, and disabilities causing significant challenges in transition, well-being, and quality of life (Umucu, 2021; Umucu et al., 2021a; Umucu et al., 2021b; Umucu et al., 2021c). We believe postsecondary education is a great opportunity to have a smooth transition to civilian and quality life for Veterans. However, due to disabilities, service-connected or not, they may have difficulties in academic settings. PTSD is one of the most common psychiatric disability among student veterans. We believe that future education, rehabilitation, counseling, and mental health research, based on our current findings, can focus on developing and/or testing positive psychology interventions to help student veterans with PTSD. Such interventions could be used in conjunction with current evidence-based counseling approaches. For example, researchers have suggested that visualizing one’s “Best Possible Selves” (BPS) is a promising strategy for positive affect elevation (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, 2006). Regarding the sense of accomplishment, researchers might evaluate Snyder (1994) hope theory whose constructs are related to pursuing and accomplishing goals. When student veterans achieve their goals, it fosters a sense of accomplishment. Therefore, counselors can implement positive psychology interventions to improve well-being in student veterans with PTSD symptoms.

Our study has multiple limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study limiting our ability to draw causal conclusions. Second, the majority of participants are male and Caucasians that limit the generalizability of the current study. Finally, we did not find engagement, relationships, and meaning as mediators, which can be due to sample size. Given the intercorrelation among the five pillars of well-being is very high, this can cause a need of higher sample size.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Ethical Permission and Consent Form. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to UW-Madison’s IRB Office.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UW-Madison IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The contents of this article were developed with support from the Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (RRTC) on Employment of People with Physical Disabilities. The RRTC was funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research Grant H133B13001 to Virginia Commonwealth University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1Umucu, E., Grenawalt, T., Prasath, P. R., Ysasi, N. A. (under review). COVID-19 Stress, PTSD, and College Adjustment Among Student Veterans. J. Coll. Couns.

References

Barry, A. E., Whiteman, S., Wadswroth, S. M., and Hitt, S. (2012). The Alcohol Use and Associated Mental Health Problems of Student Service Members/veterans in Higher Education. Drugs Educ. Prev. Pol. 19, 415–425. doi:10.3109/09687637.2011.647123

Butler, J., and Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A Brief Multidimensional Measure of Flourishing. Intnl. J. Wellbeing 6, 1–48. doi:10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., and Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness Unpacked: Positive Emotions Increase Life Satisfaction by Building Resilience. Emotion 9, 361–368. doi:10.1037/a0015952

Elliott, M. (2015). Predicting Problems on Campus: An Analysis of College Student Veterans. Analyses Soc. Issues Public Pol. 15, 105–126. doi:10.1111/asap.12066

Folkman, S., and Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Stress, Positive Emotion, and Coping. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 9, 115–118. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00073

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. NY, USA: The Guilford Press.

Hoffman, J. A., and Weiss, B. (1986). A New System for Conceptualizing College Students' Problems: Types of Crises and the Inventory of Common Problems. J. Am. Coll. Health 34, 259–266. doi:10.1080/07448481.1986.9938947

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., and Löwe, B. (2009). An Ultra-brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Levasseur, M., Desrosiers, J., and Whiteneck, G. (2010). Accomplishment Level and Satisfaction with Social Participation of Older Adults: Association with Quality of Life and Best Correlates. Qual. Life Res. 19, 665–675. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9633-5

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 40 (3), 879–891. doi:10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Prins, A., Ouimette, P. C., Kimerling, R., Cameron, R. P., Hugelshofer, D. S., Shaw-Hegwer, J., et al. (2003). The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD: Development and Operating Characteristics. Prim. Care Psychiatry 9, 9–14. doi:10.1185/135525703125002360

Rudd, M. D., Goulding, J., and Bryan, C. J. (2011). Student Veterans: a National Survey Exploring Psychological Symptoms and Suicide Risk. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 42, 354–360. doi:10.1037/a0025164

Sheldon, K. M., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to Increase and Sustain Positive Emotion: The Effects of Expressing Gratitude and Visualizing Best Possible Selves. J. Positive Psychol. 1, 73–82. doi:10.1080/17439760500510676

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The Psychology of hope: You Can Get There from Here. NY, USA: Simon & Schuster.

Umucu, E., Reyes, A., Carrola, P., Mangadu, T., Lee, B., Brooks, J. M., Fortuna, K. L., Villegas, D., Chiu, C. Y., and Valencia, C. (2021b). Pain Intensity and Mental Health Quality of Life in Veterans with Mental Illnesses: the Intermediary Role of Physical Health and the Ability to Participate in Activities. Qual. Life Res. 30 (2), 479–486. doi:10.1007/s11136-020-02642-y

Umucu, E., Villegas, D., Viramontes, R., Jung, H., and Lee, B. (2021c). Measuring Grit in Veterans with Mental Illnesses: Examining the Model Structure of Grit. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 44 (1), 87–92. doi:10.1037/prj0000420

Umucu, E., Wu, J. R., Sanchez, J., Brooks, J. M., Chiu, C. Y., Tu, W. M., et al. (2020a). Psychometric Validation of the PERMA-Profiler as a Well-Being Measure for Student Veterans. J. Am. Coll. Health 68 (3), 271–277. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1546182

Umucu, E., Brooks, J. M., Lee, B., Iwanaga, K., Wu, J.-R., Chen, A., et al. (2018). Measuring Dispositional Optimism in Student Veterans: An Item Response Theory Analysis. Mil. Psychol. 30 (6), 590–597. doi:10.1080/08995605.2018.1522161

Umucu, E. (2017). Evaluating Optimism, hope, Resilience, Coping Flexibility, Secure Attachment, and PERMA as a Well-Being Model for College Life Adjustment of Student Veterans: A Hierarchical Regression Analysis. Madison, USA: The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Umucu, E. (2021). Examining the Structure of the PERMA Theory of Well-Being in Veterans with Mental Illnesses. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 64 (4), 244–247. doi:10.1177/0034355220957093

Umucu, E., Grenawalt, T. A., Reyes, A., Tansey, T., Brooks, J., Lee, B., et al. (2019). Flourishing in Student Veterans with and without Service-Connected Disability: Psychometric Validation of the Flourishing Scale and Exploration of its Relationships with Personality and Disability. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 63 (1), 3–12. doi:10.1177/0034355218808061

Umucu, E., Lo, C. L., Lee, B., Vargas-Medrano, J., Diaz-Pacheco, V., Misra, K., et al. (2021a). Is Gratitude Associated with Suicidal Ideation in Veterans with Mental Illness and Student Veterans with PTSD Symptoms? J. nervous Ment. Dis. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000001406

Umucu, E., Moser, E., and Bezyak, J. (2020b). Assessing hope in Student Veterans. J. Coll. Student Dev. 61 (1), 115–120. doi:10.1353/csd.2020.0008

Keywords: PTSD, well-being, veterans, positive psychology, postsecondary education

Citation: Umucu E, Chan F, Lee B, Brooks J, Reyes A, Mangadu T, Chiu C-Y and Ferreira-Pinto J (2022) Well-Being, PTSD, College Adjustment in Student Veterans With and Without Disabilities. Front. Educ. 6:793286. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.793286

Received: 11 October 2021; Accepted: 06 December 2021;

Published: 20 January 2022.

Edited by:

Lisa James, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesReviewed by:

Aaron Eakman, Colorado State University, United StatesChristopher Glen Thompson, Texas A and M University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Umucu, Chan, Lee, Brooks, Reyes, Mangadu, Chiu and Ferreira-Pinto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emre Umucu, dW11Y3VlbXJAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Emre Umucu

Emre Umucu Fong Chan2

Fong Chan2 Jessica Brooks

Jessica Brooks Thenral Mangadu

Thenral Mangadu Chung-Yi Chiu

Chung-Yi Chiu