- School of Nursing and Health Professions, Trinity Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

The effective implementation of comprehensive school counseling services to all students is premised on the ASCA National Model framework themes of leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change. The school counselor’s role is to support the academic, career and social-emotional development of all students. From a school counselor advocacy and social justice perspective, school counselors engage in practices that will support all students and create opportunities for equal access and success through their leadership and service as collaborators, consultants and change agents. School counselor leadership results in positive changes within the school community. Using the ASCA Model Framework themes, school counselors can integrate these themes to support inclusivity, equity and access for students of color with disabilities, to the general education curriculum. In order to better prepare school counselor trainees to provide culturally appropriate support and services for students of color with disabilities, school counselor education programs must be more intentional in providing graduate-level course work that introduces trainees to best practices in their work with students with disabilities. First, this writer will discuss the ethical imperative for school counselor educators to be intentional in integrating special education curriculum in preparation programs and how school counselor education programs can use the ASCA Model framework themes in preparing school counselor trainees to engage in best practices to encourage, support, and ensure that students of color with disabilities have access and inclusion in the general education settings. Secondly, this writer will also discuss the incorporation of interactive related ASCA theme activities as preparation for school counselor trainees, in a special topics course as well as during practicum and internship and future professional school counselor opportunities.

The Ethical Imperative for School Counselor Educators

Research studies conducted decades ago have provided empirical data that discussed the lack of school counselor education programs properly preparing school counselor trainees to serve students with disabilities (Milsom, 2002; Milsom and Akos, 2003; Studer and Quigney, 2004). More recent studies continue to support the need for school counselor education preparation programs to include special education in school counseling program curriculum (Oberman and Graham, 2010; Hall, 2015; Goodman-Scott et al., 2019). Goodman-Scott et al. (2019) conducted research, using a case study to examine how school counselor trainees experienced course content and curriculum activities related to students with disabilities. A total of 20 school counselor trainees participated in the study. Participants noted that their exposure to the disability-specific course content and activities was a positive experience, allowing them to have a better understanding of and confidence in providing services to students with disabilities.

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) Ethical Standards for School Counselors (2016) states in the Preamble that:

“School counselors are advocates, leaders, collaborators and consultants who create systemic change by providing equitable educational access and success by connecting their school counseling programs to the district’s mission and improvement plans. School counselors demonstrate their belief that all students have the ability to learn by advocating for an education system that provides optimal learning environments for all students.” (p. 1).

Since all students include students with disabilities, it is imperative that school counselor education programs prepare school counselor trainees to be knowledgeable about special education law and practices. Most public school systems require graduate coursework which includes topics on human growth and development, theories, individual counseling, group counseling, social and cultural foundations, testing/appraisal, research and program evaluation, professional orientation, career development, and supervised practicum and internship (American School Counselor Association, 2020). A curriculum review of major graduate training programs, accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) indicate that related counselor education programs (to include school counseling) require the following eight core areas for all entry-level graduates: professional counseling orientation and ethical practice; social and cultural diversity; human growth and development; career development; counseling and helping relationships; group counseling and group work; assessment and testing; and research and program evaluation (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2020). Special education is not included as a core area of study in graduate-level preparation programs. In their 2003 study, Studer and Quigley Studer and Quigney (2003) noted the growing involvement of school counselors serving on multidisciplinary teams, where disability identification and implementation of services are determined. As previously stated, school counselor preparation programs do not adequately prepare school counselor trainees for the role and responsibilities necessary to appropriately meet the needs of students with disabilities (Vanderbilt University IRIS Center Peabody College, 2020). Goodman-Scott et al. (2019) noted that the empirical research on school counselor preparation, as related to serving students with disabilities, was conducted within a 10–15 year period. However, these studies consistently highlight findings that indicate school counselors reporting feelings of being unprepared to serve students with disabilities (Milsom, 2002; Nichter and Edmondson, 2005; Kolodinsky et al., 2009; Romano et al., 2009). School counselor reports of feeling unprepared by their preservice, graduate-level preparation program was reinforced in interviews that were conducted with programs directly. McEachern (2003) conducted a national study of preservice school counseling preparation programs in 43 states with 146 graduate programs. It was noted that only 35% of the programs had a course specifically related to students with disabilities that was required for graduates. Less than a third of them required graduates to complete disability-related clinical experiences. Although this does not provide a more current perspective of school counselor preparation programs, as it relates to serving students with disabilities, it does suggest that more needs to be done to ensure that school counselors feel prepared to appropriately meet the needs of their students with disabilities.

Hall (2015), in her article, The School Counselor and Special Education: Aligning Training With Practice, she suggested “implementing a more consistent school counselor education program across institutions, that would include coursework and experiences in special education that are in alignment with the standards of ASCA, legal obligations, and daily counselor roles” (pg. 217). School counselor educators have an ethical imperative to include curriculum and activities that will help school counselors feel more prepared to deliver services, which afford students with disabilities to achieve their full potential in the least restrictive environment. American School Counselor Association (2016a) position statement on the school counselor and student with disabilities serves as an important guide on what school counselor educators might include in their pedagogy, as it relates to the inclusion of special education in their school counseling curriculum.

The School Counselor and Special Education

The school counselor’s role is to support the academic, career and social-emotional development of all students through effective implementation of comprehensive school counseling services. They are considered vital to the educational team, and from the period of the inception of the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) to present day, advocacy efforts have focused on school counselors “being at the table” to ensure that all students’ needs are met (Holcomb-McCoy, 2007; Geltner and Leibforth, 2008; Feldwisch and Whitson, 2018; Ratts and Greenleaf, 2018; Quintana and Alvarez, 2019). There is an ethical commitment for school counselors to leverage their roles to advance access, equity and systemic change, as defined in the American School Counselor Association (2016b):

“School counselors are advocates, leaders, collaborators, and consultants who create systemic change by providing equitable educational access and success by connecting their school counseling programs to the district’s mission and improvement plans. School counselors demonstrate their belief that all students have the ability to learn by advocating for an education system that provides optimal learning environments for all students” (American School Counselor Association, 2016a, “ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors [Preamble],” para. 2).

School counselor educators have an ethical responsibility to ensure that school counseling trainees are prepared for the role of school counselor. School counselor educators must provide evidence-based pedagogical approaches that will provide students with the knowledge about current school counseling practices and the ethical and legal obligations of a school counseling practitioner. These pedagogical approaches must also prepare school counseling trainees to work with diverse student populations in schools. This diversity is not limited to race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, or sexual orientation, but also encompasses language, exceptionalities, and geographical area. Pedagogical preparation is even more important when working with students of color with disabilities, with a focus on multicultural counseling and social justice (Holcomb-McCoy, 2007). If these pedagogical approaches are engaged, school counselor trainees will be better prepared to “serve as social justice advocates to eliminate the achievement gap and to focus their efforts on ensuring success for every underserved and underrepresented student” (Dahir and Stone, 2009, p. 12, p. 12).

School counselor educators can prepare school counselor trainees to influence the support and services for students of color with disabilities by being more intentional in providing graduate-level course work that introduces trainees to working with students with disabilities. ASCA, in their position statement The School Counselor and School Counseling Preparation Programs (American Counseling Association, 2014), notes that school counseling preparation programs should “emphasize training in the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program promoting leadership, advocacy, collaboration and systemic change to enhance student achievement and success” (American Counseling Association, 2014, para 1). The ASCA Model framework themes of leadership, collaboration, advocacy and systemic change, provide a pedagogical framework in preparing school counselor trainees to engage in social justice practices that will encourage, support, and ensure that students of color with disabilities are included and have access to general education settings. In order for school counseling trainees to support inclusion and access of general education for students possessing disabilities, school counseling trainees are knowledgeable of the laws that protect students with disabilities, and the role of the school counselor in working with them (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

Laws that Protect Students With Disabilities and Define the School Counselor Role

School counselors must be well informed of the laws protecting students with disabilities and their role as defined by those laws. There are three main U.S. federal laws that address the rights of students with disabilities in U.S. public schools: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA); Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act; and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Although these laws were passed at different times (Section 504, 1973; IDEA, 1975; ADA, 1990), they provide comprehensive protections from discrimination and provide access to K-12 educational and related services.

School counselors do not limit their practice in the profession to the borders of the United States. There is a growing interest among school counselor trainees in working in international schools (Uellendahl et al., 2008; International School Counseling Association, 2017). Graybill (2020), a school psychologist working at the Anglo-American School in Moscow in his blog, What Parents of Special Needs Children Need to Know About International Schools, states that:

As private foreign institutions, international schools are not required to comply with special education laws such as the Individual with Disabilities Act (IDEA). However, in recent years, international schools have adopted special education programming to serve children with disabilities. The provision of special education services in most international schools does not follow IDEA to the letter of the law but does model its special education services based on American federal guidelines. For example, many international schools provide typical special education services through the adoption of an Individual Education Plan (IEP) (The PIE Blog; Industry Insight from Professionals in International Education).

The challenge becomes finding a school that can meet the needs of their child (ren) with special needs (Hayes and Bulat, 2017). The parallel challenge is the preparedness of the school counselor to meet the needs of this student population. Inman et al. (2009), in their study of the critical issues and challenges facing school counselors, working in international schools noted that “applying typical US-based counseling approaches may prove inadequate due to the multiplicity and complexity of international student needs” (p. 81). This supports the importance of including The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in a preparation program, adding to the school counselor trainees’ understanding, the impact of international laws on the provision of school counseling services to students with disabilities. These important laws (U.S.-based and international) are discussed below.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a “federal law designed to protect the rights of individuals with disabilities in programs and activities that receive Federal financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Education (ED)” (U.S. Department of Education, 2020; United States Department of Justice of Civil Rights Division, 2020, para. 3). Under Section 504, students with disabilities have access to accommodations that will help them to experience academic success in the general education classroom. Additionally, Section 504 regulations require that the accommodations that are afforded to non-disabled students be made available to students with disabilities, which would include counseling services (U.S. Department of Education, 2018a, Office of Civil Rights, para. 4). In many school districts, school counselors are not only a team member but also manage the 504 cases on their counseling load.

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) provides more protections for students with disabilities. IDEA “is a law that makes available a free appropriate public education to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services to those children” (U.S. Department of Education, 2018b; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (1990), P.L. 101–476). IDEA not only mandates a free, appropriate public education (FAPE), but also provides the condition in which this free, appropriate education takes place-in the least restrictive environment (LRE) for students with disabilities.

There is a specific provision for counseling services addressed by IDEA. Under Section 300.34, counseling is listed as one of the many possible related services that can be provided to students with disabilities. Specifically, it states, “Counseling services means services provided by qualified social workers, psychologists, guidance counselors, or other qualified personnel” (U.S. Department of Education, 2016, Section c.2). Congress reauthorized the IDEA in 2004 and most recently amended the IDEA through Public Law 114–95, The Every Student Succeeds Act, in December 2015. Noteworthy is that under this legislation the issue of disproportionality in the overrepresentation of students of color in special education is not only addressed, but the legislation also ensures that students of color receive the supports they need to succeed. Finally, the legislation also requires that state and local education agencies’ policies, practices and procedures are in compliance with The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 (US Department of Education, ESEA Section 1111(g) (1) (B), 2018) (GovTrack.us, 2020).

American Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), viewed as the “equal opportunity law” for people with disabilities, was passed on July 26, 1990 and signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. ADA addresses the gaps in protections for persons with disabilities which were found with Section 504. Both pieces of these legislative statues ensure that any public or private situation a disabled person might encounter is addressed (United States Department of Justice of Civil Rights Division, 2020). The ADA, one of America's most comprehensive pieces of civil rights legislation, prohibits discrimination and guarantees that people with disabilities have equal opportunities, as any other American, to enjoy employment opportunities, to purchase goods and services, and to participate in State and local government programs and services.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) was adopted on December 13, 2006, signed March 30, 2007, and came into force May 3, 2008. The CRPD is the results of decades of work by the United Nations United Nations (2008) to change the attitudes and approaches to persons with disabilities. Specifically, it is noted that:

The Convention is intended as a human rights instrument with an explicit, social development dimension. It adopts a broad categorization of persons with disabilities and reaffirms that all persons with all types of disabilities must enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms. It clarifies and qualifies how all categories of rights apply to persons with disabilities and identifies areas where adaptations have to be made for persons with disabilities to effectively exercise their rights and areas where their rights have been violate, and where protection of rights must be reinforced (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Disability, CRPD Homepage, para. 3).

Article 7 (Children with Disabilities) and Article 24 (Education) of The Convention defines the rights of persons with disabilities and the obligations of states parties to uphold those rights.

School counselor trainees must also understand the issues surrounding special education. This is equally as important as understanding the laws that provide the protections for such issues. One of those issues, which is most impactful for students of color, is disproportionality. The following discussion on this issue provides insight on why this is important to a school counselor trainees preparation.

Understanding the Issue of Disproportionality

Why is it important that school counselor trainees understand the issue of disproportionality? The importance of understanding disproportionality informs trainees’ preparation for advocacy and social justice. School counselor trainees need to understand what “significant disproportionality” means and the need to “identify racial and ethnic disparities in disability identification, as required under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and its regulations” (Harper and Fergus, 2017). The authors also emphasized the need of the community to be more diligent in reexamining “How general and special education systems support children of color, with attention to early intervention, inequities in quality of education, and bias in identification procedures” (Harper and Fergus, 2017).

In an Education Week article (2019), the authors documented an increase in the number of students receiving special education services. Although the statistics (Supplementary Table S1) demonstrate this increase taking place in 2017–18, it is worth noting that the number of students identified with disabilities grew from 6.5 million (13.4%) to seven million (13.7). When analyzed by race, this statistical increase revealed that 14.1% of White students; 16% of Black students; 13% of Hispanic students; 7.1% Asian students; 10.9% Pacific Islander students; 17.5% American Indian/Alaska Native students; and 13.8% of students identified as multi-ethnic were served under IDEA (Riser-Kositsky, 2019). Although there are studies that suggest minority students may be underidentified for disabilities (Morgan et al., 2015), Riser-Kositsky reported that new research seems to suggest the contrary–that in some contexts, there is overidentification (Lardieri, 2018;Samuels, 2019).

Moreover, in the U.S. Department of Education’s 40th Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education National Education Association, 2007 Act (2018), noted that 12% of Black children in the United States receive special education services for emotion disturbances, physical disabilities and intellectual impairment. However, even with these statistics, there continues to be discussion on the issue of disproportionality or the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of students of color in special education (Artiles et al., 2002; Van Roekel, 2008; Cooc and Kiru, 2018; Samuels, 2019). Earlier research noted that students of color were more likely to be over-identified in the categories of educable mentally retarded (EMR), trainable mentally retarded (TMR) and emotional disturbance (ED) (Artiles et al., 2002). More recent research conducted by Morgan et al. (2015) suggests that this over-identification may not be the case. These authors concluded that Black children were more likely to be underrepresented in special education than their White peers. However, Harper and Fergus (2017) do not agree. They argued that identification of Black children, 6–21 years of age, continue to be 40% for special education services.

School counselor trainees need to understand the implications of overrepresentation or overidentification of students of color in special education. Harper and Fergus (2017) noted that many of the students of color in special education do not receive adequate support services to succeed in school. Additionally, they noted that students of color face educational barriers that exclude them from the general education curriculum. Schifter et al. (2019) conducted a study to better understand the disproportionality that occurs for low-income students of color. The study involved three unnamed states. Results from this study of these three states documented that students of color from low-income families “were more likely to be identified for special education than their non-low-income peers” (p. 2) and “were also more likely to be placed in substantially separate classrooms than their non-low-income peers” (p. 3). These sobering research results provide further evidence of the need for school counselor trainees to be prepared to support students of color with disabilities through social justice advocacy for systemic change. This paper proposes how school counseling preparation programs can prepare school counselor trainees to effectively support students of color with disabilities using the ASCA Model themes. Next, the themes and their relationship to providing comprehensive school counseling services to students generally and special education students specifically will be discussed.

ASCA Model Themes: From Peripheral to Interwoven

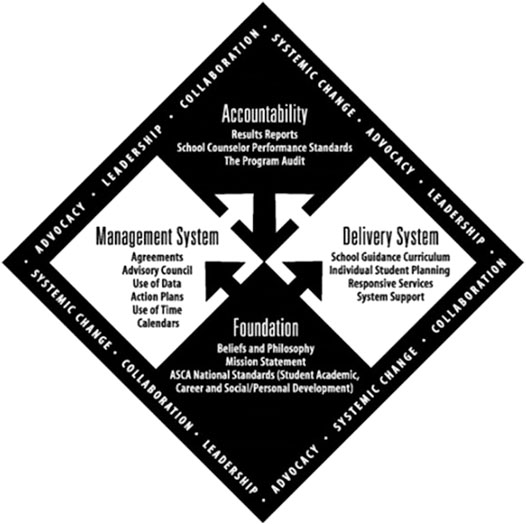

The diamond in the third edition of the ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs, depicts the framework of the model. The themes, leadership, advocacy, collaboration and systemic change, were incorporated into the framework to emphasize the impact of these areas on the work that school counselors do in providing comprehensive school counseling services that support student achievement and promote equity and access through systemic change advocacy. In Figure 1, the themes are on the outside of the frame, demonstrating the importance of these skills, in implementing the four interrelated components in the delivery of services within a comprehensive school counseling program.

FIGURE 1. The ASCA National Model Diagram (third Edition). SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the American School Counselor Association.

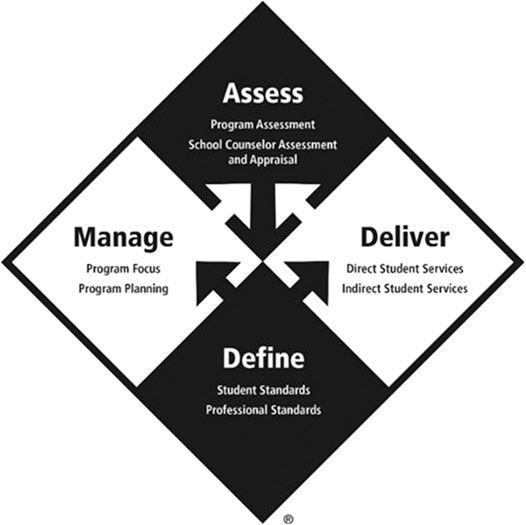

In the fourth edition, ASCA determined that the four themes were more than peripheral to the Model framework and were required in providing a comprehensive school counseling program, with the goal of helping every student succeed through systemic change outcomes. In discussing the change, ASCA noted that “The four themes of leadership, advocacy, collaboration and systemic change no longer appear around the edge of the ASCA National Model diamond but instead are woven throughout the ASCA National Model to show they are integral components of a comprehensive school counseling program” (American School Counselor Association, 2019a, p. 116). This further underscores the importance of these themes, along with advocacy skill development and social justice, being interwoven into school counselor education curriculum Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. The ASCA National Model Diagram (fourth edition). SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the American School Counselor Association.

School Counselor Preparation in Leadership, Advocacy, Collaboration, Systemic Change and Social Justice

There are school counselor practices that help to frame how school counselor trainees can be prepared to meet the needs of all students. The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (2016a) require that school counselor education programs prepare school counselor trainees for the “school counselor roles as leaders, advocates, and systems change agents in P-12 schools” (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2016b, G.2. a). These roles are also identified as practices, which are noted in ASCA’s position statement on school counseling preparation programs emphasizing “training in the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program promoting leadership, advocacy, collaboration and systemic change to enhance student achievement and success” (American Counseling Association, 2014, para 1). When you consider the role of the school counselor in meeting the needs of all students, the need for school counseling trainees to have knowledge and exposure to working with students with disabilities is more than just a “good thing”, but should be an imperative part of school counselor education programs. Interwoven in the implementation of the ASCA National Model are school counselor practices that will help prepare school counselor trainees in understanding their role in working with students with disabilities. These practices are leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and social justice. These practices are especially important for school counselor trainees to develop in order for their work with students of colors with disabilities for more inclusion opportunities in general education courses. This inclusion includes access to advanced placement courses as well as career and technical education courses for college preparation (Reis and Colbert, 2004; National Network, 2018). School counselor trainees must develop and access skills in leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and social justice to guarantee inclusivity, equity and access for students of color with disabilities. So, how does this happen?

In July 2018, the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) adopted Ethical Standards for School Counselor Education Faculty. The standards address the preparedness of school counselor educators in having the knowledge of current practices in the school counseling profession, and the legal and ethical responsibility of school counselors (American School Counselor Association, 2018). Specifically, in Standard A.2, the ethical standards notes that school counselor educators should “have the knowledge and skills to support social justice and advocacy efforts and to teach graduate students to become culturally competent school counselors and leaders” (American School Counselor Association, 2018, section A–Content Knowledge). The following discussion highlights how school counselor educators can incorporate the practices of leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change with a social justice focus to prepare school counselor trainees in working with students with disabilities.

Leadership: Two Models

Leadership is identified as the essential practice that moves the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program. School counselor leaders embody the responsibility of positively impacting student outcomes by providing comprehensive school counseling services that support academic achievement and promote equity and access. Young and Kneale (2013) stated, “Working as a school counselor leader requires moving beyond transformative school counseling roles to initiating schoolwide or districtwide school counseling systemic strategies and being present at the decision-making tables” (p. 3). In order to help school counselor trainees realize this concept, it will be important for trainees to understand two models that align with the ASCA National Model. These models include the Four-Framework Approach and 21 Responsibilities for School Leaders.

Four-Framework Approach.Bolman and Deal (1997) identified four leader behaviors that Dollarhide (2003) applied to comprehensive school counseling programs. These four leader behaviors provide school counselors a way to guide their approach to addressing issues involving students of color with disabilities. These four leader behaviors are identified within the ASCA Model framework as the Four-Framework Approach. In their book entitled School Counselor Leadership: The Essential Practice, Young and Kneale (2013) discuss each of the leader behaviors in the Four-Framework Approach as shown in Supplementary Table S2.

21 Responsibilities for School Leaders. Another leadership practice to introduce to school counseling trainees is a framework more closely aligned with school counseling and requires school counselors to understand and use instructional best practices (Young and Kneale, 2013). This leadership framework, identified as 21 Responsibilities for School Leaders, was developed by Marzano et al. (2005). Within this framework, there are 21 leadership responsibilities identified, but there are six that more closely align with school counseling. These are discussed in Supplementary Table S3.

Mason and McMahon (2009) conducted a study that focused on school counselor leadership practices in relation to age, gender, professional training, experience, or school setting. The research concluded that there was a relationship between school counselor leadership and these variables. More importantly, the authors suggested that there should be more intentionality in school counselor preparation programs in addressing the development of leadership skills and leadership identity in school counselor trainees (Mason and McMahon, 2009). The result of this effort would be a transference of these learned skills and identity into practice (Mason and McMahon, 2009).

Instruction in leadership development skills will enable school counselor trainees to understand how they can position themselves to effectively assist their students of color with disabilities. When school counselor trainees understand the contexts in which leadership occurs, and the activities and skills that should be appropriately executed within these contexts, they are able to design, implement, evaluate comprehensive school counseling services that help to transform the educational environment, ensuring equity and access for students of color with disabilities in mainstream education (adapted from Dollarhide, 2013). Because leadership is an essential part of the role of the school counselor, school counselor education programs should provide instruction on leadership models that will facilitate the development of leadership skills that will prepare school counselor trainees to execute other learned skills and strategies in areas such as behavior management, social-emotional development, assessment, child and adolescent development, individual and group counseling, to appropriately address any equity and access issues for students of color with disabilities (Lambert, 2002).

One of the steps toward becoming a leader is taking on the role of advocate. School counselor advocacy extends beyond the profession. As social justice advocates, school counselors identify barriers and biases that prevent certain groups of students from having access to certain educational spaces. Social justice school counselors advocate for and promote educational equity for all students. A discussion on school counselor advocacy follows.

Advocacy

School counselor advocacy not only focuses on the profession itself, but also equity and access for students who are not represented in programs or services that support their academic, social-emotional and career development. Advocacy is vital to the role of school counselors and in preparing school counselor trainees, the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselor Education American School Counselor Association, 2018 notes that school counselor education faculty should “have the knowledge and skills to support social justice and advocacy efforts” as well as provide a curriculum that “emphasizes social justice, advocacy, and multiculturalism” to prepare school counselor trainees to work with diverse populations (American School Counselor Association, 2018). Advocacy is prominently mentioned throughout the ASCA Ethical Standards for School American School Counselor Association (2016a), and advocacy for student with disabilities is specifically addressed in Standard A.10, Underserved and At-Risk Populations. “School counselors advocate for the equal right and access to free, appropriate public education for all youth, in which students are not stigmatized or isolated based on their housing status, disability, foster care, special education status, mental health or any other exceptionality or special need” and “recognize the strengths of students with disabilities as well as their challenges and provide best practices and current research in supporting their academic, career and social-emotional needs” (ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors, A.10. f andand A.10. g, 2016).

Holcomb-McCoy (2007) noted that the school counselor advocacy role was very important, regarding the individualized education program (IEP) committee and student placement. As previously mentioned, research documents the disproportionality of students of color in special education, and it is at this critical point, according to Holcomb-McCoy, that school counselor advocacy, locally and nationally, would help to ensure disabled students access the best educational services, as well as “fair, unbiased decision-making regarding special education placement” (Holcomb-McCoy, 2007, p. 110). Disproportionality of students of color in special education signals the need for school counselors to “advocate for policies that state what is an unacceptable number of students of color in special education” (Holcomb-McCoy, 2007, p. 110).

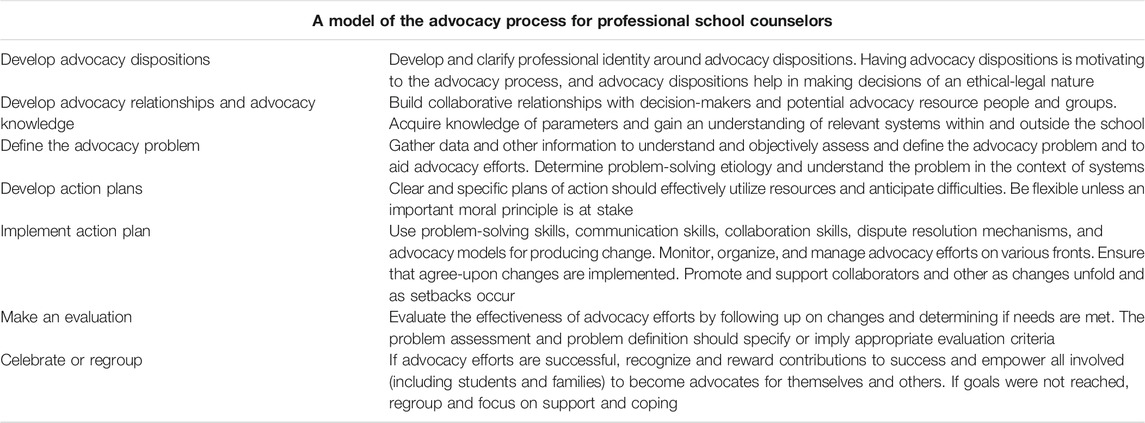

To bring more clarity and delineation to school advocacy, Trusty and Brown (2005) developed a structure for conceptualizing advocacy in the context of school counselor competencies. In doing this, advocacy would be more clearly defined and distinguished from other school counseling roles as the “structure, purposes, and processes of advocacy would be illuminated” (pg. 260). In developing the advocacy competencies, the authors used Fiedler’s (adapted from Trusty and Brown, 2005) special educator competencies as a model. In determining what would be effective advocacy, Fiedler categorized the special educator competencies into dispositions (personal qualities of the special educator) -- knowledge and skills. The advocacy competencies for school counselors were: dispositions (advocacy disposition; family support/empowerment disposition; social advocacy disposition and ethical dispositions), knowledge (knowledge of resources; knowledge parameters; knowledge of dispute resolution mechanisms; knowledge of advocacy models; and knowledge of systems change), and skills (communication skills; collaboration skills; problem-assessment skills; problem-solving skills; organizational skills; and self-care skills). From this constructed competencies, Trusty and Brown (2005) developed a model of the advocacy process for professional school counselors as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. model of the advocacy process for professional school counselors (Trusty and Brown, 2005).

School counselor trainees must be trained in advocacy in order to be effective in addressing the disproportionality of students of color with disabilities in special education classes. Using the advocacy competencies for school counselors and the model of advocacy process for professional school counselors, school counselor preparation programs can help school counselor trainees better understand the role of advocacy in collecting, disaggregating and analyzing data to identify the systemic issues that impact students of color with disabilities; school counselor trainees will also learn barriers which limit or prevent students of color with disabilities from having access to general education program and services. School counselor trainees are better positioned to identify systemic barriers, such as school policies and practices that impede students of color with disabilities access to more positive academic, social-emotional and career development outcomes.

Finally, it is important that school counselor trainees develop advocacy skills because advocacy is an ethical imperative, especially in working with students with disabilities. The ASCA Code of Ethical Standards for School American School Counselor Association (2016b) specifically state that school counselors “Advocate for the equal right and access to free, appropriate public education for all youth, in which students are not stigmatized or isolated based on their housing status, disability, foster care, special education status, mental health or any other exceptionality or special need” (A.10. f). Standard A.10. g continues this ethical imperative in noting that school counselors “recognize the strengths of students with disabilities as well as their challenges and provide best practices and current research in supporting their academic, career, and social-emotional needs.” Appropriate preparation of school counselor trainees in advocacy skills will help increase their effectiveness as advocates, including cultural competency advocacy, for equitable treatment of all students in schools and communities.

Collaboration

Meeting the multiple and varied needs of students is not the sole responsibility of the school counselor. In delivering responsive services, school counselors need the support and assistance of the entire school community as well as the community beyond the school (Sink, 2011). Collaboration is a very necessary practice of in the school counseling profession. The ASCA School Counselor Professional American School Counselor Association (2019a) identifies in its Behaviors standard that school counselors “collaborate with families, teachers, administrators, other school staff and education stakeholders for student achievement and success” (American School Counselor Association (2019b), p 2).

Allen (1994), in discussing school collaboration for student success, he provided the following in describing the characteristics of collaboration:

“Collaboration is the process whereby two individuals or groups work together for a common goal, a mutual benefit, or a desired outcome. Trust, respect, openness, active listening, clear communication, and risk taking are fundamental requirements for collaborative efforts….Initiating and maintaining collaborative efforts is an appropriate role of the school counselor in educational reform” (p. 1).

Gibbons et al. (2010) conducted a study examining the perceptions and attitudes of school counselors about collaboration. The study revealed that school counselors participated in regular collaboration with various stakeholder groups, to include students, teachers, administrator, parents, other school counselors, school support staff, and community agency personnel (Gibbons et al., 2010). The study confirmed that school counselors exercised their ethical responsibility to “collaborate as needed to provide optimum services with other professionals such as special educators, school nurses, school social workers, school psychologists, college counselors/admissions officers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, and administrators” (ASCA Ethical Standard B2. q, 2016, p. 7). School counselors would not be able to effectively deliver comprehensive school counseling services if they worked in isolation. Collaboration positions the school counselor to promote equity and access for marginalized populations, especially students of color with disabilities.

School counselors have the responsibility of helping all students achieve academic success. School counselors serve on various collaborative teams that provide them an opportunity to have valuable input that contributes to a student’s academic success. These collaborative relationships maybe be student support teams or multidisciplinary teams (sometimes referred to as Individualized Education Planning [IEP] teams) when working with students with disabilities. Team members come with diverse expertize, and school counselors provide information that other team members may not have due to their lack of skill or knowledge. For instance, school counselors are trained in areas such as college and career readiness, social-emotional development, and study skills development. Such knowledge and skills framed within an advocacy and social justice lens enables school counselors to better represent students of color with disabilities, in ensuring that their academic interests are considered in discussions of inclusion in general education. Barrow and Mamlin (2016) suggest that early involvement of the school counselor, especially in their roles as consultant, in working with the classroom teacher offers an opportunity for early identification as well as early intervention. This kind of collaborative relationship can result in an equitable education experience for students of color with disabilities as it offers the opportunity for the school counselor and special education teacher to worked together in developing research and evidenced-based, culturally responsive interventions (Barrow and Mamlin, 2016).

School counselor preparation programs have an accreditation mandate (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2016b) to prepare school counselor trainees with “techniques to foster collaboration and teamwork within schools” (School Counseling Standard 3.l). For school counselor trainees to know and be able to work with other school staff, it is imperative that they are provided learning activities that require them to engage in culturally competent collaborative planning. For instance, one such activity might include learning how to design and write IEP goals that relate to the services they would provide for students of color with disabilities, in consultation with a general or special education teacher.

The need for collaboration between school counselors, general and special education teachers, and other related service providers becomes more paramount, as students with disabilities gain more access to general education classrooms. As part of this collaborative engagement, school counselors can help parents and students by providing them information that will prepare them to participate in all phases of the special education process. With their training in developing multicultural competency, school counselors can support school personnel in building relationships with students and families of color that will promote positive educational outcomes. When school counselors engage in these collaborative relationships to deliver appropriate counseling interventions and support services to students of color with disabilities and school personnel, they increase the possibility of students of color experiencing success in general education classes (Cahill and Mitra, 2008).

Social Justice and Systemic Change

School counselors are social justice advocates and system change agents. In their varied roles as leaders, advocates, collaborators and consultants, professional school counselors exercise their ethical responsibility to provide a comprehensive, data-driven school counseling program that help students minimize or eliminate barriers to academic success, career and social-emotional development. As social justice advocates and system change agents, they also advocate for achievement, access, and opportunity for all students. Their social justice lens allows them to identify barriers and inequities that exist in school and district-level policies and procedures, as well as in federal and state laws, regulations, and funding. As noted in the ASCA National American School Counselor Association (2012) third edition:

“Systemic change occurs when inequitable policies, procedures and attitudes are changed, promoting equity and access to educational opportunities for all students. Systemic barriers can be school-based, district-based, or at the state or federal level. Change happens through the sustained involvement of all critical players” (American School Counselor Association, 2012, p. 9).

As social justice advocates and systemic change agents, professional school counselors are positioned to advocate for students of color with disabilities and their parents in what can oftentimes be an intimidating education bureaucracy. The more professional school counselors know about testing and special programs, special education and the requirements of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the more effective their advocacy will be to create systemic change.

It is essential that school counselor preparation programs prepare school counselor trainees to understand school systems’ standardized testing programs, the child study process, special education eligibility procedures and planning, Section 504 eligibility procedures and modifications, and group and individual assessment procedures and interpretation strategies.

School counselor trainees should be aware that systemic change involves school wide changes in expectations, instructional practices, support services, and philosophy with the goal of raising achievement levels and creating opportunity and access for all students. Training should focus on data-driven programming that will allow professional school counselors to identify areas in need of improvement, leading to alterations in systemic policies and procedures that empower students of color with disabilities to experience higher performance and greater opportunities for academic success.

The need for school counselor education programs to address social justice advocacy is not only promoted in the ASCA Standards, but also within the standards of the accrediting body for counselor education programs and the American Counseling Association (ACA). The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) provides guidance for graduate counseling programs to teach graduate counseling students “advocacy processes needed to address institutional and social barriers that impede access, equity, and success for clients” (Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs, 2016b, p. 9). The American Counseling Association (ACA) promotes the expectation of graduate counseling programs to ensure that graduate counseling students are prepared to address social injustices in schools and communities as stated in its Code of Ethics, Standard A7a, “When appropriate, counselors advocate at individual, group, institutional, and societal levels to address potential barriers and obstacles that inhibit access and/or the growth and development of clients” (American Counseling Association, 2014, p. 5).

If school counselor education preparation programs are tasked with preparing school counselor trainees with the knowledge and skills to address the issue of access and equity in their work with students, how might their social justice advocacy be more intentional? How should school counselor trainees be trained in practices that support inclusion, equity, and access for students of color with disabilities to the general education curriculum? The following will outline interactive activities, that can be incorporated into a special topics course focused on preparing school counselor trainees the school counselor practices, that will accomplish systemic change that allows access and equity for students of color with disabilities.

Interactive Activities Using School Counselor Practices: Leadership, Advocacy, Collaboration, Systemic Change and Social Justice Advocacy

Supplementary Table S4 is an example of course topics and related interactive activities that could be included in a special topics course, which focuses on preparing school counselor trainees to work with students with disabilities, in general and more specifically with students of color, with a focus on inclusion, equity and access to the general education curriculum. These proposed interactive activities are premised on establishing a partnership with a local school district, to provide school counselor trainees a more realistic experience in understanding the role of the school counselor in addressing the needs of students of color with disabilities. Each activity will have one or more of the ASCA National Model themes-leadership, advocacy, collaboration, systemic change, in the context of social justice advocacy-interwoven in them.

Conclusion

Leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change are school counselor practices that define how the role of the professional school counseling is executed. They are integrated throughout the work they do to provide comprehensive school counseling services to all students. These practices, executed with a social justice perspective, can be impactful as school counselors engage policies, practices, and systems that present barriers to inclusion, equity, and access for students of color, as well as multi-ethnic students with disabilities. This underscores the need for school counselor preparation programs to commit to intentionality, in preparing school counselor trainees in these practices to support students of color with disabilities. This investment in training can be the key to preparing school counselors to engage in social justice advocacy that will help position students of color with disabilities, to navigate through the educational system and beyond successfully.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest:

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.588528/full#supplementary-material.

References

Allen, J. M. (1994). School counselors collaborating for student success (Theme Digest Contract No. RR93002004). Washington, DC, United States: US Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

American Counseling Association (2014). ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA, United States, United States: Author.

American School Counselor Association (2012). The ASCA national model: a framework for School Counseling Programs. 3rd edn. Alexandria, VA, United States: Author.

American School Counselor Association (2016a). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Ethics/EthicalStandards2016.pdf (Accessed June 11, 2020).

American School Counselor Association (2016b). The professional school counselor and students with disabilities [Position Statement]. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PS_Disabilities.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2020).

American School Counselor Association (2018). ASCA ethical standards for school counselor education faculty. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Ethics/SCEEthicalStandards.pdf (Accessed June 11, 2020).

American School Counselor Association (2019a). The ASCA national model: a framework for School Counseling Programs. 4th edn. Alexandria, VA, United Satates: Author.

American School Counselor Association (2019b). ASCA school counselor professional standards and competencies. Alexandria, VA, United States: Author.

American School Counselor Association (2020). The school counselor and school counseling preparation programs [Position Statement]. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PS_Preparation.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2020).

Artiles, A. J., Harry, B., Reschly, D. J., and Chinn, P. C. (2002). Over-identification of students of color in special education: a critical overview. Multicultural Perspect. 4 (1), 3–10. doi:10.1207/s15327892mcp0401_2

Barrow, J., and Mamlin, N. (2016). Collaboration between professional school counselors and special education teachers. Ideas and research you can use: vistas. Available at: https://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas (Accessed May 19, 2020).

Bolman, L. G., and Deal, T. E. (1997). Reframing organizations: artistry, choice, and leadership. 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA, United States: Jossey-Bass.

Cahill, S. M., and Mitra, S. (2008). Forging collaborative relationships to meet the demands of inclusion. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 44, 149–151. doi:10.1080/00228958.2008.10516513

Cooc, N., and Kiru, E. W. (2018). Disproportionality in special education: a synthesis of international research and trends. J. Spec. Edu., 52 (3), 163–173.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (2020). Find a program. Available at: https://www.cacrep.org/directory (Accessed December 23, 2020).

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (2016a). School counseling. Available at: http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2020).

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (2016b). School counseling. Available at: https://www.cacrep.org/section-5-entry-level-specialty-areas-school-counseling/ (Accessed June 15, 2020).

Dahir, C. A., and Stone, C. B. (2009). School counselor accountability: the path to social justice and systemic change. J. Couns. andDev. 87 (1), 12–20. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00544.x

Dollarhide, C. T. (2003). School counselors as program leaders: applying leadership contexts to school counseling. Prof. Sch. Couns. 6 (5), 304–308.

Dollarhide, C. T. (2013). The messy process of school counselor leadership. ASCA School Counselor, 11–18.

Feldwisch, R. P., and Whiston, S. C. (2018). Examining school counselors’ commitments to social justice advocacy. Prof. Sch. Couns. 19 (1), 166–175. doi:10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.166

Geltner, J., and Leibforth, T. (2008). Advocacy in the IEP process: strengths-based school counseling in action. Prof. Sch. Couns. 12 (2), 162–165. doi:10.5330/psc.n.2010-12.162

Gibbons, M. M., Diambra, J. F., and Buchanan, D. K. (2010). School counselor perceptions and attitudes about collaboration. J. Sch. Couns. 8 (34), 1–28.

Goodman-Scott, E., Bobzien, J., and Milsom, A. (2019). Preparing preservice school counselors to serve students with disabilities: a case study. Prof. Sch. Couns. 22 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1177/2156759x19867338

GovTrack.us (2020). S.117 – 114th congress: every student succeeds act. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/s1177 (Accessed May 18, 2020).

Graybill, J. (2020). What parents of special needs children need to know about international schools. The PIE Blog, Professionals in International Education, Available at: https://blog.thepienews.com/2020/04/what-parents-of-special-needs-children-need-to-know-about-international-schools/.

Hall, J. G. (2015). The school counselor and special education: Aligning training with practice. The Prof. Counselor 5 (2), 217–224.

Harper, K., and Fergus, E. (2017). Policymakers cannot ignore the overrepresentation of black students in special education. Child trends. https://www.childtrends.org/blog/policymakers-cannot-ignore-overrepresentation-black-students-special-education.

Hayes, A. M., and Bulat, J. (2017). Disabilities inclusive education systems and policies guide for low- and middle-income countries. Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581498.pdf (Accessed December 27, 2020).

Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2007). School counseling to close the achievement gap: a social justice framework for success. Thousand Oaks, CA, United States: Corwin Press.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (1990). Individuals with disabilities education improvement act of 2004, 101–476. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUE-104/pdf/STATUE-104-pg1103.pdf (Accessed May 16, 2020).

Inman, A. G., Ngoubene-Atioky, A., Ladany, N., and Mack, T. (2009). School counselors in international school: critical issues and challenges. Int. J. Adv. Counselling 31, 80–99. doi:10.1007/s10447-009-9070-8

International School Counseling Association (2017). Becoming an international school counselor. Retrieved from https://www.isca.com.

Kolodinsky, P., Draves, P., Schroder, V., Lindsey, C., and Zlatev, M. (2009). Reported levels of satisfaction and frustration by Arizona school counselors: a desire for greater connections with students in a data-driven era. Prof. Sch. Couns., 12, 193–199. doi:10.5330/psc.n.2010-12.193

Lardieri, A. (2018). Study: minorities labeled learning disabled because of social inequities. Washington, DC, United States: U.S. News and Report. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2018-08-21/study-minorities-labeled-learning-disabled-because-of-social-inequalities#:∼:text=The%20study%20by%20Portland%20State,learning%20disability%2C%20according%20to%20a (Accessed May 15, 2020).

Marzano, R., Waters, T., and McNulty, B. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. Alexandria, VA, United States: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Mason, E., and McMahon, H. (2009). Leadership practices of school counselors. Prof. Sch. Couns., 13 (2), 107–115. doi:10.5330/psc.n.2010-13.107

McEachern, A. G. (2003). School counselor preparation to meet the guidance needs of exceptional students: a national study. Counselor Edu. andSupervision 42, 314–325. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01822.x

Milsom, A., and Akos, P. (2003). Preparing school counselors to work with students with disabilities. Counselor Edu. Supervision 43, 86–95. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01833.x

Milsom, A. (2002). Students with disabilities: school counselor involvement and preparation, 5. Professional School Counseling, 331–338.

Morgan, P. L., Farkas, G., Hillemeier, M. M., Mattison, R., Maczuga, S., Li, H., et al. (2015). Minorities are disproportionately underrepresented in special education. Educ. Res. 44 (5), 278–292. doi:10.3102/0013189x15591157 |

National Education Association (2007). Truth in labeling: disproportionality in special education. Available at: http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/HE/EW-TruthInLabeling.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2020).

National Network (2018). Disability rights laws in public primary and secondary education: how do they relate? Retrieved from https://adata.org/factsheet/disability-rights-laws-public-primary-and-secondary-education-how-do-they-relate. (June 11, 2020).

Nichter, M., and Edmondson, S. L. (2005). Counseling services for special education students. J. Prof. Couns. Pract. Theor. Res. 33, 5–62. doi:10.1080/15566382.2005.12033817

Oberman, A., and Graham, T. (2010). Preparing school counselor trainees to work with students with exceptionalities. Available at: https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/students-with-exceptionalities.pdf (Accessed May 17, 2020).

Quintana, T., and Alvarez, J. (2019). Advocacy for all: serving students with disabilities. Alexandria, VA, United States: Rhode Island School Counselor Association (RISCA) News. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/newsletters/november-2019/advocacy-for-all-serving-students-with-disabiliti?st=RI (Accessed May 18, 2020).

Ratts, M. J., and Greenleaf, A. T. (2018). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies. Prof. Sch. Couns. 21 (1b), 2156759X1877358–9. doi:10.1177/2156759X18773582

Reis, S. M., and Colbert, R. (2004). Counseling needs of academically talented students with learning disabilities. Prof. Sch. Couns. 8 (2), 156–167.

Riser-Kositsky, M. (2019). Special education: definition, statistics, and trends. Bethesda, MD, United States: Education Week Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/special-populations/ (July 3, 2020).

Romano, D. M., Paradise, L. V., and Green, E. J. (2009). School counselors’ attitudes towards providing services to students receiving Section 540 classroom accommodations: implications for school counselor educators. J. Sch. Couns. 7, 1–36.

Samuels, C. A. (2019). Schools’ racial makeup can sway disability diagnoses. Bethesda, MD, United States: Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/06/12/segregation-sways-disability-diagnoses.html (Accessed May 17, 2020)

Schifter, L. A., Grindal, T., Schwartz, G., and Hehir, T. (2019). Students from low-income families and special education. New York, NY, United States: The Century Foundation https://tcf.org/content/report/students-low-income-families-special-education/?agreed=1.

Sink, C. (2011). School-wide responsive services and the value of collaboration. Professional School Counseling, 14 (3), 2156759x1101400301. doi:10.1177/2156759x1101400301

Studer, J. R., and Quigney, T. A. (2003). An analysis of the time spent with students with special needs by professional school counselors. Am. Secondary Edu. 31 (2), 71–83.

Studer, J. R., and Quigney, T. A. (2004). The need to integrate more special education content into pre-service preparation program for school counselors. Guidance Couns. 20 (1), 56–63.

Trusty, J., and Brown, D. (2005). Advocacy competencies for professional school counselors. Prof. Sch. Counselor 8 (3), 259–263.

Uellendahl, G. E., Rennebohm, M., and Buono, L. (2008). School counseling abroad. ACA professional counseling digest. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/resources/library/ACA%20Digests/ACAPCD-17.pdf. (January 2, 2021).

United Nations (2008). The convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html (December 22, 2020).

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division (2020). Information and technical assistance on the American with disabilities act. Retrieved from https://www.ada.gov/ada_intro.htm (June 11, 2020).

U.S. Department of Education (2018b). 40th Annual report to congress on the implementation of the individuals with disabilities education act https://www.2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2018/parts-b-c/40th-arc-for-idea.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education (2018a). Elementary and secondary education act of 1965 [As Amended through P.L. 115–224. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/legislation/index.html.Enacted. (July 31, 2018).

U.S. Department of Education (2016). Parent and educator resource guide to section 504 in public elementary and secondary schools. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/504-resource-guide-201612.pdf (June 11, 2020).

U.S. Department of Education (2020). Protecting students with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html (June 11, 2020).

Van Roekel, D. (2008). Disproportionality: inappropriate identification of culturally and linguistically diverse children (NEA Policy Brief). Available at: http://E:/RESEARCH%20AGENDA/SPECIAL%20EDUCATION/Disproportionality%20-%20Inappropriate%20Identification%20of%20Culturally%20and%20Linquistically%20Diverse%20Children.pdf (Accessed May 16, 2020).

Vanderbilt University IRIS Center Peabody College (2020). What are the roles and responsibilities of school counselors when working with students with disabilities. Available at: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/cou/cresource/q2/p02/ (Accessed May 15, 2020).

Keywords: special education, leadership, school counselor advocacy, collaboration, inclusion

Citation: Reese DM (2021) School Counselor Preparation to Support Inclusivity, Equity and Access for Students of Color With Disabilities. Front. Educ. 6:588528. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.588528

Received: 29 July 2020; Accepted: 21 January 2021;

Published: 12 March 2021.

Edited by:

Waganesh A Zeleke, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lynne Sanford Koester, University of Montana, United StatesTracey Colville, University of Dundee, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Reese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diane M. Reese, ReeseD@trinitydc.edu

Diane M. Reese

Diane M. Reese