- 1School of Education and Social Work, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

- 2School of Education, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 3School of Education, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

There is continued interest internationally in primary-secondary school transitions. Fourteen literature reviews of primary-secondary transitions have been published over the last 20 years, however none of them have systematically analysed primary-secondary school transition ontology, i.e., researchers’ worldviews, theories/models and frameworks. This is a major gap in these reviews and the papers published in this area; this is of concern as it is difficult to trust the robustness of a study if its foundation, such as researchers’ conceptualisation of transitions, is not visible. Therefore, using the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) approach, we undertook a systematic mapping review, of empirical studies published internationally between 2008 and 2018. Our objectives were to explore researchers’ and research participants’ conceptualisation of transitions, the conceptual framework used by the researchers and their discourse about transitions. Of the 96 studies included in this systematic mapping review, most had not clearly defined transition, and even when conceptualisation was explicit, it did not underline the research design or frame the findings. Most researchers adopted previously used theoretical frameworks.These theoretical frameworks can be beneficial; however, as the researchers did not adapt or develop them in the context of transitions research, it limits a meta-theoretical understanding of transitions. Further, the majority did not report study participants’conceptualisation of transitions. Similarly, a large number of researchers adopted a negative discourse about primary-secondary school transitions, with some using a mixed discourse and only two papers had a primarily positive discourse. This systematic mapping review is original and significant as it is the first study to provide a review of school transitions ontology and offers unique insights into the conceptual and methodological gaps that international transitions researchers should address.

Introduction

Internationally there is continued and increasing interest by governments and researchers in how primary-secondary school transitions in late childhood or early adolescence, impact children’s educational and wellbeing outcomes (Symonds and Galton, 2014; Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019; Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). The timing of this ‘mid-schooling’ transition (Youngman, 1986) differs depending on the education system: in two tier systems, such as in Scotland, children transfer once from primary to secondary school, whereas in three tier systems, such as in the United States, children transfer twice, from elementary to middle or junior high school and then to high school. Regardless of each country’s tier system, in all cases, children transfer from primary education to secondary education (Eurydice, 2018). We used the terms primary and secondary in this review as well as the term mid-schooling transition, to create a definition that holds across education systems internationally.

In the past two decades there have been at least 14 reviews of empirical research on primary-secondary school transitions (Anderson et al., 2000; Benner, 2011; Topping, 2011; Hanewald, 2013; Hughes et al., 2013; Symonds and Galton, 2014; Cantali, 2017; Galton and McLellan, 2017; Pearson et al., 2017; Evans et al., 2018; van Rens et al., 2018; Jindal-Snape et al., 2020); and as books (Akos et al., 2005; Howe and Richards, 2011; Symonds, 2015). In principle, they provide a solid evidence base for researchers to build on. Only a handful of these are published within the period 2008–2018 (Hanewald, 2013; Hughes et al., 2013; Pearson et al., 2017 and meet Garrard (2016) criteria for systematic reviews as identified by Jindal-Snape et al. (2020). Although this map of the research skyline helps researchers build upwards empirically, the field’s foundations have not yet been systematically examined. As such, this leaves researchers without a clear understanding of how primary-secondary school transitions have been conceptualised. The current study aims to address this gap by providing the first mapping review of primary-secondary school transitions ontology: defined as researchers’ worldviews, theories/models and frameworks (Overton, 2015). This study makes an original and significant contribution to the field of primary-secondary transitions research internationally; this transition ontology will also be relevant to other educational transitions (e.g., transitions to primary school).

Emerging Conceptualisations of Primary-Secondary School Transitions

Primary-secondary school transitions research has existed since at least the 1960s (Symonds and Galton, 2014), and across the sixty-year period has remained focussed on children’s outcomes, children’s experiences of school organisation, and transition supports (Galton and McLellan, 2017; Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). Within the field, especially in England, the term transfer has also been used to describe moving from one school to another, whilst the term transition has been reserved to describe the more gradual process of moving between years within the same school (Galton et al., 2000). However, Jindal-Snape, (2016) has defined transitions as the ongoing psychological, social and educational adaptations due to moving between, and within, schools. In other cases, across the world, authors have used the term primary-secondary transitions without differentiating between these two conceptualisations.

As children experience their first term in the secondary school, they can report initial positive perceptions that are soon replaced by more negative accounts, and this is described by Hargreaves (1984) as ‘the honeymoon period’. On the other hand, a longitudinal study carried out across three school years, found that children’s positive expectations and ‘reality’ stayed the same during this move and negative experiences declined over time (Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019).

Another useful concept emerging from the research is that of environmental continuity and discontinuity, which refers to the elements of school culture and organisation that are similar or different (e.g., disrupted) across transition (Galton et al., 1999). This concept has been used in combination with Galton’s ‘Five Bridges’ of school administration, pedagogy, curriculum, social organisation and children’s self-management (Galton et al., 1999; Symonds, 2015), to identify, for example, discontinuities in pedagogical practices between primary-secondary schools in Scotland (Jindal-Snape and Foggie, 2008). It also examines curricular continuities created by primary and secondary schools working together to provide ‘bridging units’ in science subjects in England (Galton et al., 2003; Galton, 2010).

A higher-level concept regarding discontinuity is of primary-secondary school transition as a ‘status passage’ (Measor and Woods, 1984), where young people’s behaviour is expected to alter in the new environment. Here, the young person graduates from one status to another as they pass through a passage of discontinuity. The use of this notion in school transition research originated from the status passage research of Glaser and Strauss (1971). With school transition typically occurring during the pubertal window of age 8–14 years, school transitions have been described as a Western status passage with overarching similarities to the adolescence initiation ceremonies practiced in some indigenous non-Western cultures (Symonds, 2015). These ceremonies typically involve segregation (e.g., a separating oneself from a social group), transition (the ritual, e.g., stomach binding), and incorporation (re-entering the community with a change in status, e.g., as an adolescent or adult) (Goldstein and Blumenkrantz, 2019). When young people change schools, they ‘become’ a different type of pupil (e.g., a ‘secondary pupil’ or a ‘senior school pupil’) (Symonds, 2015).

The continuity and discontinuity concept is also central to Eccles et al. (1993) Stage-Environment Fit theory that predicts changes in children’s wellbeing (in particular motivation to learn) as a function of the fit or misfit between their current stage of psychological and social development, and the environmental discontinuity or continuity they experience in the secondary school. For example, early adolescents (age 10–14 years) typically desire more autonomy, but they rarely receive it when teachers are stricter in the transfer secondary school compared to the associated primary school (Eccles et al., 1993) which is known as the ‘transfer paradox’ (Hallinan and Hallinan, 1992); although others have found this to be a misconception which changed when children moved to secondary school (Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019). Other concepts that tie in with continuities and discontinuities are Noye's (2006) notion of school transition acting as a prism to diffract children’s experiences, and Symond's (2015) response that school transition also acts as a lens to focus children on aspects of themselves that are brought into the spotlight as they change schools.

School transitions have also been conceptualised as a distinct time period characterised by qualitatively different phases. Nicholson (1984) transitions cycle was originally designed for occupational psychology and has been repurposed for primary-secondary school transitions research by several researchers (Jindal-Snape, 2016; Symonds and Hargreaves, 2016; Galton and McLellan, 2017). The transitions cycle consists of four phases: preparation for transfer whilst in the feeder school, initial encounters made in the transfer school, adaptation to the transfer school and stabilisation of psychology and behaviour across time. Common to the first phase of preparation, children are found to experience ‘eager anticipation’ (Rudduck, 1996) about the transfer, which presents an interesting combination of the emotions of anxiety and happiness (Galton and McLellan, 2017).

Finally, the breadth and complexity of transitions is identified in Jindal-Snape’s Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) Theory which is based on research findings from participants and significant others across ages and educational and life stages (e.g., Jindal-Snape and Foggie, 2008; Jindal-Snape, 2016; Gordon et al., 2017; Jindal-Snape et al., 2019). MMT Theory emphasises that children experience multiple transitions at the same time, in multiple domains (e.g., social, academic) and multiple contexts (e.g., school, home). These multiple transitions impact each other and can trigger transitions for other people (e.g., friends, parents, teachers) and vice versa, meaning that transition overall is a multi-dimensional process (Jindal-Snape, 2016; Gordon et al., 2017). Using the Rubik’s cube analogy, if each colour is one child’s dynamic ecosystem, a slight change in one dimension will trigger changes in other dimensions. Further, it will trigger change and accompanying transitions for other children and their significant others. It acknowledges the complex and dynamic nature of transitions and does not see transitions as linear but as continuously evolving (Jindal-Snape, 2016; Jindal-Snape, 2018). It also highlights that these transitions are situated in, and interact with, ever-changing complex systems, e.g., policy, curriculum, or recently, the pandemic.

Studying Conceptualisations of Primary-Secondary School Transitions

The different concepts that have emerged from research on primary-secondary school transitions have increased researchers’ sensitivity to nuanced aspects of changing schools. However, except for primary-secondary school transitions being defined as the transfer from one school to another (Galton et al., 1999), or as an ongoing process of psychological, social and educational adaptation occurring due to changes in context, interpersonal relationships and identity, which can be simultaneously exciting and worrying for an individual and others in their lives, and which requires ongoing additional support (Jindal-Snape, 2018), none of these concepts make sense of transitions in absolute terms. What is school transition as a phenomenon? What are its defining features? Is school transition simply three phases of adaptation (encounter, preparation and adaptation) that happen sequentially as children change schools, or is it far more complex than that, as indicated by MMT Theory (Jindal-Snape, 2016)? Without clarity on what primary-secondary school transitions are there is less chance for the field to make systematic progress towards understanding its implications for children and significant others. In addition, this presents fewer opportunities to make a positive difference to children’s transition experiences and educational and wellbeing outcomes.

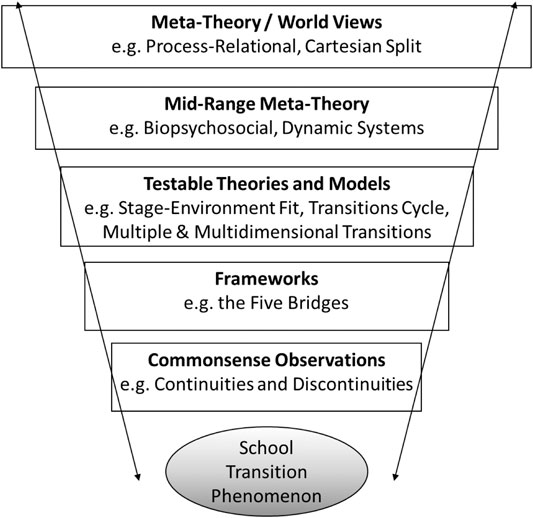

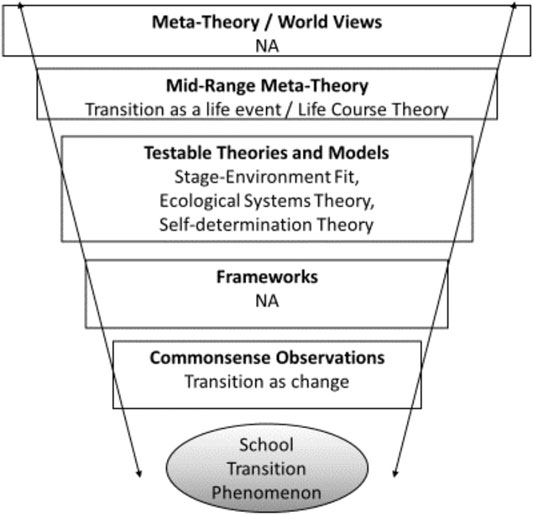

Therefore, it is crucial that we provide a framework of ontology to advance the field. Just as empirical studies often use conceptual frameworks to organise and understand their data, studies of theory can also use frameworks for mapping and understanding conceptualisations. Overton's (2015) multi-level framework of scientific paradigms indicates how a domain of inquiry (in this case, primary-secondary school transitions) can be conceptualised at different levels of formality and complexity. At the lowest level are common-sense observations, such as those a parent, teacher, child or even researcher might use to intuitively explain school transition and children’s experiences. Above this are more formal models and theories that seek to explain processes. We have divided these into two types (Figure 1). Firstly, organisational frameworks such as the Five Bridges (Galton et al., 1999) help to identify characteristics of a phenomenon, but do not predict or explain processes within it. Secondly, testable models and theories that seek to explain how a process operates, such as the MMT theory (Jindal-Snape, 2016). Above these are mid-range meta-theories that set out the broad conditions of a phenomenon, i.e., whether it is embodied, biopsychosocial, transactional or dialectic. At the highest level are ontological worldviews such as whether there can be testable relations between parts of a process (i.e., the mechanistic premise of Cartesian dualism) or whether a process is non-linear and irrevocably meshed as understood by process-relational theorists.

Importantly for the current study, Overton's (2015) framework enables us to systematically map different conceptualisations of school transition into a hierarchy of ontologies to identify strengths, gaps and potential for theoretical development. It allows for viewpoints from different people, including participants, practitioners and researchers, to be located at specific levels and assessed in terms of formality and complexity. Figure 1 illustrates the school transition worldviews, theories/models and frameworks known to the four authors before conducting the systematic review (i.e., naïve structure) identifying where these are placed in a hierarchy of ontology, to illustrate the types of findings we might expect from the proposed systematic mapping review.

A further issue of interest is the discourse used by researchers when writing about school transitions. What types of discourse are used to frame primary-secondary school transitions and how might these be linked to the conceptualisations? Are transitions seen as more positive or negative for children, teachers, schools and families? Discourses used in research can be linked to a particular world view, for example the rejection of deficit models that seek to identify causes of weakness in favour of strengths-based perspectives that focus on identifying how people can function in optimal ways (Reeve, 2015). They can also be culturally relative, such as research that prioritises influences on the individual self (for example, Ecological Systems Theory), which can be in contrast to other indigenous psychological models where the self is conceptualised as an offshoot of the family or ancestors (Shute and Slee, 2015).

These considerations of transition conceptualisation and discourse led to four research questions that frame the current study, in the context of primary-secondary school transitions.

1 How have primary-secondary school transitions been conceptualised by researchers in the literature? Here we seek to clarify the type and range of conceptualisations of school transition, locating these on Overton's (2015) framework to understand their level of formality.

2 How have these transitions been conceptualised by participants in the research literature? Like the first question, the second question aims to uncover the type, range and formality of conceptualisations of transitions used by research participants. By investigating this we can identify similarities and differences between conceptualisations used by researchers and their participants.

3 What theoretical frameworks are used within primary-secondary school transitions research? Following our review of the concepts emerging from the primary-secondary school transitions research, it is also of interest to map the different frameworks, models and theories that are used in conjunction with school transitions as a concept. These are not conceptualisations of transitions per se, but rather help explain different qualities and aspects of the transition experience, for example Stage-Environment Fit (Eccles et al., 1993) and Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions theories (Jindal-Snape, 2016; Jindal-Snape et al., 2019).

4 What type of discourse about school transitions do researchers use? Finally, our interest in how conceptualisations are framed from cultural, historical and social perspectives leads us to investigate whether the researchers used a positive, neutral, mixed or negative discourse about school transitions.

Methodology

To answer these questions, we drew on 96 papers retrieved for a commissioned systematic literature review which analysed empirical papers published between 2008 and 2018 that focussed on primary-secondary school transitions (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). The rationale for utilising this time period was the existence of a relatively low number of literature reviews (n=9) and systematic literature reviews (n=3) focusing on primary-secondary transitions. Furthermore, it was difficult to reach conclusions given the different foci, inclusion/exclusion criteria and time periods of the reviews. The present paper uses different research questions from the original systematic review to analyse the retrieved papers. It employs a systematic mapping approach (Gough et al., 2019) where the focus is on conceptualisation and discourse surrounding transitions rather than study findings.

Systematic Literature Review Approach

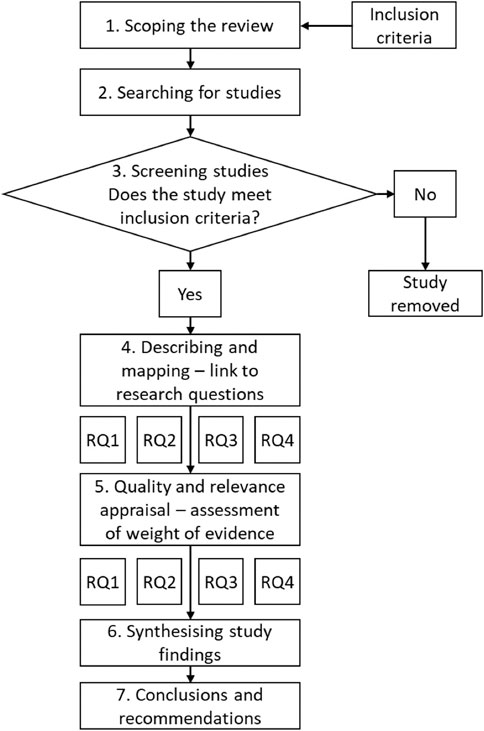

We used the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre, 2010) approach to systematic literature reviews (Figure 2). The process outlined in Steps 1–3 and 5 was used for the Jindal-Snape et al. (2020) review. Step 4 describes the approach taken to analyse the 96 papers against the four research questions which form the focus of this paper; Steps 6–7 are also particular to this paper.

Scoping the Review

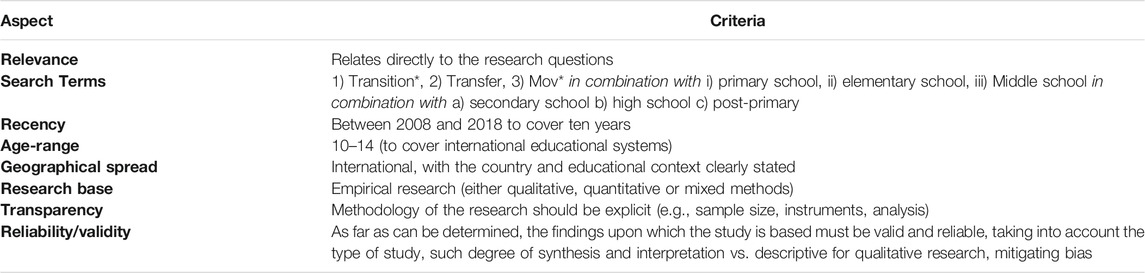

We started by developing explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria for specifying which literature to include in the review. These included relevance, recency, transparency and reliability/validity (See Table 1).

Searching for Studies

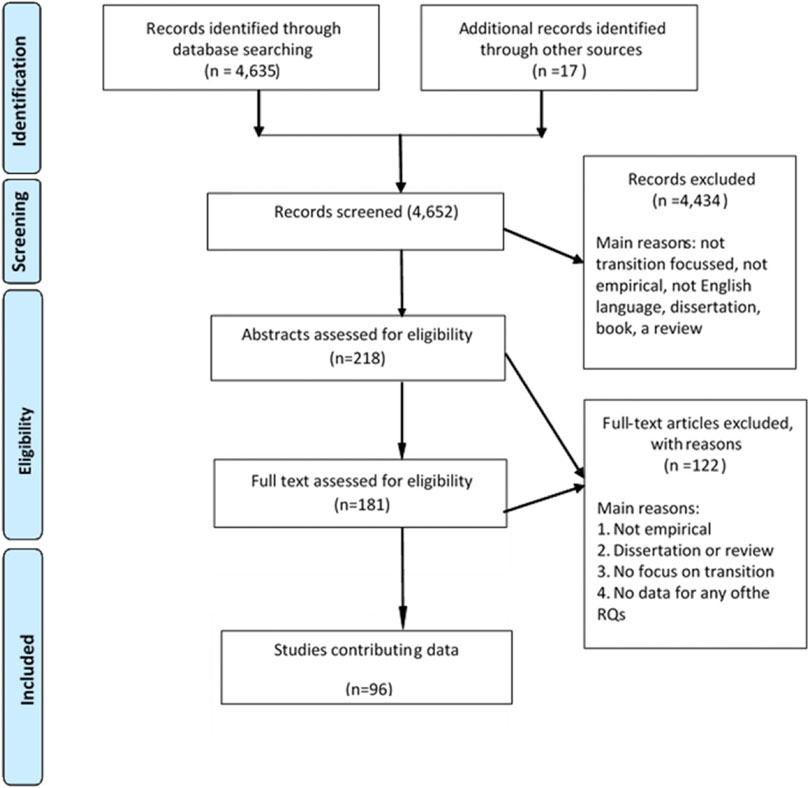

We searched multiple online databases and our search returned 4,635 records for screening (2,444 from three core databases in the Web of Science (WoS) - Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index; 679 from the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC); 662 from the British Education Index (BEI); 569 from PsycINFO; and 281 from Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA). We also found a further 17 records through searching of other sources, such as references in the papers and contacting known researchers in the area. This gave a total of 4,652 records for screening (see Figure 2). We also scanned the contents of key journals in the field, such as the British Educational Research Journal.

Screening Studies

Each paper was screened against the inclusion criteria developed when scoping the review (Table 1). By appraising each study against the same criteria and recording the results, the basis for the review’s conclusions have been made transparent. Our screening process, comprising reading and cross-reading of abstracts by all authors was conducted according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria and resulted in 4,434 records being excluded for one of five main reasons: it was not a study that was focussed on transition between primary and secondary school; it did not report any empirical data; it was not published in full in the English language; it was a book or dissertation; or it was a report of a review, overview or discussion piece. This left 218 papers and their abstracts were reviewed by the authors; resulting in rejection of another 37 papers. A full read of all 181 papers led to further rejection due to the lack of meaningful fit with the research questions. This resulted in 96 studies for the review (see Figure 3).

Describing and Mapping the Studies

For the purposes of this mapping review, the 96 papers were randomly assigned to the four authors of this paper (24 each) by sorting them into a random order and assigning them in sequential blocks of 24. Papers written by any of the authors were assigned to one of the other authors. In line with the four research questions, we developed an initial coding scheme for categorising key elements of the papers. This included geographic location and theoretical perspective (if any) on primary-secondary school transitions that were tested for relevance by each author coding the first five studies. After discussion on the results of this initial coding, a final set of codes was developed that addressed the research questions more comprehensively. These were a) reference details b) journal impact factor c) journal focus (e.g., special educational needs), d) discipline of the researchers (e.g., developmental psychology), e) setting/school year (e.g., last year of primary school to first year of secondary school), f) paper topic (e.g., quality of life and school transition), g) transition conceptualisation (whether a definition of school transition was explicitly stated or implicitly suggested in the paper by the researcher/s and what that definition entailed), h) discourse tone (whether the discourse used to discuss transition by the researchers was positive, negative or neutral/mixed), i) theories/conceptual frameworks (e.g., Stage-Environment Fit), and j) participants’ conceptualisation of school transition (whether reported or not, and what it was if reported).

The authors read each paper and coded them, using the system outlined above, into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and shared their analysis with one another. At this point, the authors, as a team, reviewed the results to identify where further classification systems would help answer the research questions. The results for g) transition conceptualisation were diverse, so a set of codes were inductively developed for these data by the authors, using key terms written in the publications as the basis for salient codes (e.g., transition as ‘change’; transition as ‘status/rite of passage’). Each author returned to their papers to check they fitted with these inductive codes for transition conceptualisation. The codes and their content are described in more detail in the results section. To provide further quality assurance of this analytic process, the final results were analysed numerically and qualitatively by the first author and checked by the second author for accuracy.

Quality and Evidence Appraisal

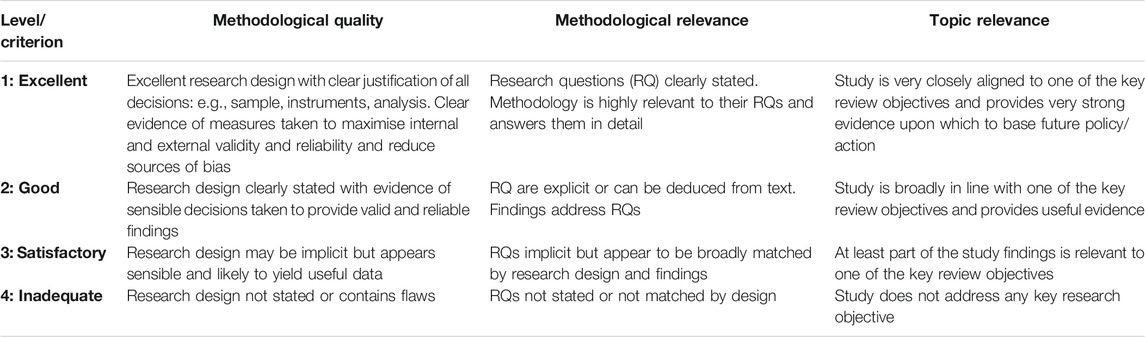

An adapted version of the EPPI-Centre Weight of Evidence (WoE) judgments were applied to each of the included studies, whereby the ‘methodological relevance’ referred to the study rather than to the research questions of the systematic review (note that this refers to the questions in Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). Three components were assessed in order to help derive an overall weighting of evidence score (see Table 2).

There was variability in the WoE ratings across the 96 papers. Thirty studies (31%) were found to be excellent across all three criteria of methodological quality, methodological relevance and topic relevance. Some studies had excellence ratings in more than one criterion and 85 (86%) studies were found to be excellent or good for topic relevance. In light of this, we included all 96 papers, especially as our focus for this paper was on conceptualisation and theoretical frameworks.

Synthesising Study Findings

A systematic mapping review was undertaken which aimed to provide a picture of the current state of knowledge, in relation to the four research questions, and thus enhance future primary-secondary transitions research (Gough et al., 2019). The results of this mapping exercise are presented numerically and as narrative below. Narrative Empirical Synthesis (EPPI-Centre, 2010) was used to bring together the results of the mapping exercise. This mapping provides an accessible combination of results from individual studies in a structured narrative.

Conclusions/Recommendations

The conclusions and recommendations focussed on explaining how the worldviews, theories, models and frameworks found in the systematic review mapped onto Overton's (2015) framework of ontology, to illustrate prevalence and coverage. This allowed the authors to identify gaps in school transition ontology and possible connections between conceptualisations, to drive the field forwards.

Ethics

We followed our profession’s code of practice (General Teaching Council for Scotland, Health and Care Professions Council) and were governed by our Universities’ research ethics guidelines. The team are committed to ethical analysis of the literature and reporting.

Results

Data from the 96 papers are presented here, although not all papers have been explicitly referred to. Results are presented under themes related to the research questions.

Conceptualisation of Primary-Secondary School Transitions by Researchers

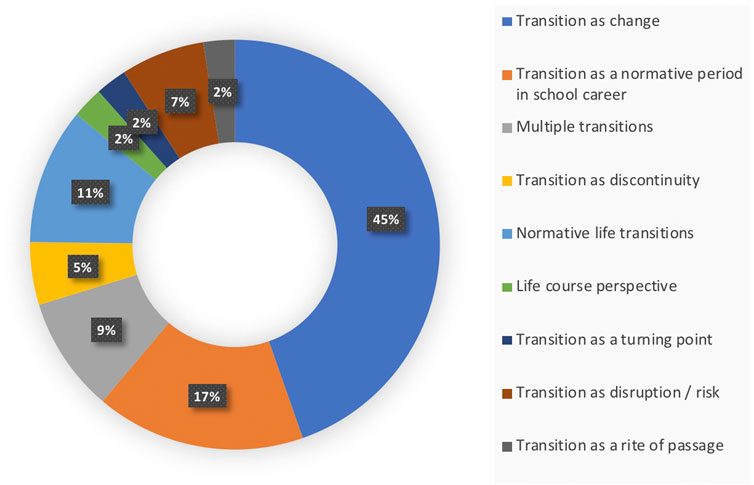

Of the 96 papers, 86 paper author/s provided some insight into their conceptualisation of primary to secondary school transitions. In some cases, we needed to infer what the conceptualisation was based on the researchers’ broader conceptual framework, research design and/or type of data presented. The lack of explicit conceptualisation and operationalisation of the key term could lead to misunderstandings for future researchers. As described in the methodology section, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis of the transition conceptualisations and found ten overarching themes. Please note that in some cases researchers were not clear about their own conceptualisation and referred to multiple conceptualisations and theories across their paper so the numbers do not add to 86 (see Figure 4).

Transition as change. Fifty four papers referred to transition as change; these were change in social relationships, pedagogical approaches (e.g., Mackenzie et al., 2012), change in academic demands (e.g., Kingdon et al., 2017), change in the environment (e.g., Waters et al., 2014a) and organisation (e.g., Arens et al., 2013), change related to developmental stages e.g., (Arens et al., 2013; Vasquez-Salgado and Chavira, 2014; Andreas and Jackson, 2015), and systemic changes (e.g., Strnadova et al., 2016).

Normative life transition. Forty one papers conceptualised primary-secondary school transitions as a normative life transition; 13 papers presented it as a normative life event e.g., (Neal et al., 2016).

Transition as a normative period in school career. Twenty papers conceptualised primary-secondary transitions as a normative period in a child’s school career (e.g., Burchinal et al., 2008; Weiss and Baker-Smith, 2010; Brewin and Statham, 2011). This conceptualisation is perhaps not surprising as most of the authors of these papers came from an education or psychology (mainly developmental and educational) background apart from one statistician and one medic.

Multiple transitions. Author/s of eleven papers referred to multiple transitions, i.e., children/young people experiencing multiple changes at the same time, such as moving from one educational setting to another, differences in school culture and structure, significant biological, psychological and social changes, and change in teachers (e.g., Knesting et al., 2008; Serbin et al., 2013; Lofgran et al., 2015).

Transition as disruption/risk. Eight papers referred to transition as disruptive and highlighted the risk factors for children e.g., (Maher, 2010; Mackenzie et al., 2012; Keay et al., 2015).

Transition as discontinuity. Six papers referred to transition as a time of discontinuity, both curricular and relational (e.g., Rainer and Cropley, 2015; Makin et al., 2017). However, these could be seen to be similar to the first category of transition as change.

Life course perspective. Three papers used a life course conceptualisation taken from Elder’s Theory (1998) (Benner and Wang, 2014; Fortuna, 2014; Witherspoon and Ennett, 2011).

Transition as a rite of passage. In three papers, transition was conceptualised as a rite of passage (Bailey and Baines, 2012; Rainer and Cropley, 2015; West et al., 2010).

Transition as a turning point. Three papers discussed transitions as turning points (Langenkamp, 2010; Andreas and Jackson, 2015; Scanlon et al., 2016).

Transfer as a paradox. One paper seemed to conceptualise it as the transfer paradox, although it does not name it as such (Rainer and Cropley, 2015).

Conceptualisation of Primary-Secondary School Transitions by Research Participants

It is not clear from any papers whether the researchers asked participants how they conceptualised transitions. However, one can start making assumptions about what participant/s might consider, and/or found, transition to be from 12 papers which presented qualitative data. Of these 12 papers, six were based on studies undertaken in the United Kingdom (Jindal-Snape and Foggie, 2008; Dismore and Bailey, 2010; Keay et al., 2015; Neal and Frederickson, 2016; Peters and Brooks, 2016; Makin et al., 2017), three in Australia (Maher, 2010; Mackenzie et al., 2012; Strnadova et al., 2016) and one each in South Africa (Mudaly and Sukhdeo, 2015), United States (Ellerbrock and Kiefer, 2013), and Ireland (Scanlon et al., 2016). Most of the studies were small scale, primarily focussing on interview data from a small group of children, parents and/or teachers, ranging from 6 to 23 participants (please note that the latter numbers include only four pupils and the rest are professionals in Ellerbrock and Kiefer, 2013).

Participants’ conceptualisations included an understanding of transitions being a period of change, particularly systemic level and relationship changes, change in pedagogical approaches and curriculum, and the transfer paradox of being excited and concerned. For example, in Makin et al. (2017) study, children with an autism spectrum condition recognized difficulty adjusting to the new environment, a loss of social support and change in identity.

Similarly, Peters and Brooks (2016) reported that their participants, i.e., parents of children with Asperger and high functioning autism in England, discussed changes to routines, environment and relationships. Peters and Brook's (2016) conceptualise primary-secondary transition to be a milestone which includes substantial changes. However, it is interesting to consider the relationship between Peter and Brooks (2016) own conceptualisation and that of their participants, while also considering the potential for bias in questions asked.

Further, although most papers in this review collected data from pupils, parents and/or teachers, only these 12 papers have presented data in a way that an informed assumption about their conceptualisation was possible. It is not clear whether any of the 96 papers we reviewed directly ascertained participants’ conceptualisation; a mismatch in conceptualisation might lead to incorrect interpretation of the data.

Theoretical Conceptual Frameworks Used in Primary-Secondary School Transitions Research

Thirty three papers used a theoretical framework that was not explicitly about transition as a phenomenon, to explain complex processes occurring during primary-secondary school transitions. Of these papers, 11 were from the United States, seven from Australia, seven from the United Kingdom (in England, Scotland and Wales but not Northern Ireland), two each from Canada and Israel, and one each from Finland, Germany, Peru and South Africa. Not all 33 papers are cited here, for brevity.

One might assume that journals with high impact factor would insist that the papers include a clear theoretical framework of transitions. However, there was no support for this assumption as the 33 papers were published in journals with a range of impact factors. Seven were in journals that had no impact factor, three had impact factors below 1, eight were between 1.3 and 1.5, three had impact factors between 1.8 and 1.9, four were between 2.1 and 2.9, seven were between three and four and one had an impact factor of 4.1 (Waters et al., 2014b in Journal of Adolescent Health).

The theoretical frameworks used were mainly mentioned in the introduction sections; however this did not mean that they necessarily underpinned the studies. This could suggest that the authors mentioned a theory when writing a paper rather than the theoretical framework influencing the design of their study. The most prevalent theoretical frameworks were Stage-Environment Fit Theory (Eccles and Midgley, 1989) (n=10) which was used to provide reasons for young people not engaging with learning in secondary schools; Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1993) (n=8) which was used to explain the context of transitions, although Brewin and Statham (2011) also used it as a framework for data collection and analysis; Life Course Theory (Elder, 1998) (n=5) which was used to highlight that transitions are a normative life transition; and Self-determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000) which was used to explore the role and development of participants’ autonomy, relatedness and competence across transition. None of the papers have critiqued the theory/ies and/or their application in the context of primary-secondary school transitions. Below we discuss these most common theoretical frameworks in more detail to understand the extent to which they underpinned the research and the links with researchers’ conceptualisation of transitions.

Stage-Environment Fit Theory. This theory was referred to in 10 studies across a decade and the timeline of this review, i.e., 2008 to 2018. The principal authors had a background in either developmental or educational psychology. These studies were conducted in the United States (n=6), United Kingdom (n=2), Germany (n=1) and Israel (n=1). Nine of the papers conceptualised transition as a normative life transition and therefore it is not surprising that they used Stage-Environment Fit Theory. Author(s) of five studies focussed on the negative aspects of primary-secondary transitions, whereas four concentrated on both negative and positive features, and one had a neutral discourse. This theory emphasises the mismatch between the adolescent’s developmental stage and associated needs, compared to the demands of the secondary school environment (Benner and Graham, 2009). Although the theory was created to explain psychological development across the middle school transition, it does not explain school transition as a process per say. Rather it can be used to refer to any systemic change in environment and how this connects to change in a person’s psychology, depending on the person’s stage of development.

Interestingly, like other theories, Stage-Environment Fit Theory was only mentioned once in some papers in the introduction section to provide a background to the ‘problem’ (e.g., Benner and Graham, 2009; Kingery et al., 2011; Arens et al., 2013; Benner and Wang, 2014). Witherspoon and Ennett (2011) refer to the theory as part of their theoretical framework and then in the discussion. Knesting et al. (2008) did not refer to the theory but used Eccles and Midgley (1989) work to highlight the differences in the primary and secondary school environment. Madjar and Chohat (2017) used it as a framework to draw a hypothesis for their study; however they did not return to it in the results or discussion. On the other hand, Neal et al. (2016) referred to it at the start and then returned to it in the discussion to state that their findings were similar to the research behind the theory. Similarly, Ellerbrock and Kiefer (2013) use it as the theory underpinning their study in the case study approach they took. Symonds and Hargreaves (2016) and Zoller Booth and Gerard (2014) are the only two studies fully underpinned by this theory.

Brofenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Brofenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Brofenbrenner, 1989) was used in four papers in Australia (Waters et al., 2014a; Waters et al., 2014b; Strnadova and Cumming, 2014; Strnadova et al., 2016), three papers in the United Kingdom (Brewin and Statham, 2011; Hannah and Topping, 2013; Mandy et al., 2016a), and one in United States (Booth and Sheehan, 2008). As our review covered papers from 2008 to 2018, it is interesting to note that the year of publication was in a narrower time period; four papers are from 2014 (two from the same researchers), and one each from 2011 to 2013. Four (United Kingdom, n=3; Australia, n=1) of the papers focussed on young people with additional support needs.

Hannah and Topping (2013) used this theory to design their transition programme which they evaluated, rather than using it for research. As mentioned earlier, Brewin and Statham (2011) organised their findings around the ecosystems; they reported that it was a useful way of showing the factors, and their interaction, that had an impact on looked after children’s transitions. Waters et al. (2014a) used the theory to explain the role of contexts in human development, with school being such a context; whereas in (Waters et al., 2014b) they use the Ecological Systems Theory to conceptualise the support systems of young people as they move to secondary school. Similarly, Strnadova and Cumming (2014), Strnadova et al. (2016), and Booth and Sheehan (2008) used the theory to understand transitions and relationships in the ecosystems of young people moving to secondary school. Four of the papers had a negative discourse, one both (Hannah and Topping, 2013) and one neutral (Strnadova and Cumming, 2014). It is interesting to note that although Booth and Sheehan (2008), and Strnadova and Cumming used the same theory, they used different discourses about transition.

Life Course Theory. The researchers who conceptualised primary-secondary transitions to be a normative life and/or school career transition used Elder's (1998) Life Course Theory to explain their conceptualisation (n=5). This is the only theory that includes transitions as one of its features. Two papers were based on research conducted in Canada, and three from the United States; two papers from the United States have the same primary author who has a background in developmental psychology (Benner and Graham, 2009; Benner et al., 2017), another with background in clinical psychology (Kingdon et al., 2017), one primary author in education (Witherspoon and Ennett, 2011) and one in sociology (Felmlee et al., 2018). They published in the highest impact factor journals in the context of this literature review ranging from 1.304 to 3.8. Benner and colleagues conceptualised transitions as negative in the main and have focussed on the disruptions and challenges that primary-secondary transitions cause for children and young people, although they also mentioned some positives (Benner and Graham, 2009). Similarly, Felmlee et al. (2018) and Kingdon et al. (2017) have used a negative discourse; whereas Witherspoon and Ennett (2011) have focussed on both positive and negative aspects of transitions. None of these researchers have presented participants’ voice.

Self-determination theory. Ryan and Deci's (2000) self-determination theory was used in four papers, one each from Australia, Finland, Peru and the United Kingdom, published in journals with an impact factor ranging from 0.3 to 3.2. These papers focussed on positive aspects of psychology including school connectedness, school belonging, school attendance, quality of life, wellbeing and autonomy. Despite their use of positive constructs, all papers used a negative discourse about primary-secondary school transitions. We review our findings on discourse in more detail below.

Discourse Used by Researchers

The discourse about transitions is very important as it can give messages, both spoken and unspoken, about what to expect when making a transition. The researchers’ discourse also gives an insight into their beliefs about primary-secondary school transitions, which might influence their research questions, and questions asked of their participants. Therefore, we analysed the papers to understand the discourse by looking carefully at the introduction/framing of their study, results, discussion and conclusions. We found that the narrative was, in the main, more explicit in the introduction section of the papers rather than throughout.

Negative discourse about transition. Sixty papers (not all cited to aid brevity) highlighted negative aspects of transitions. The settings of these studies are detailed in Table 3. These included the premise and argument based on previous literature that transitions were disruptive, challenged children’s psychological wellbeing (Poorthuis et al., 2014), led to a decline in science self-efficacy scores (Lofgran et al., 2015; no comparison was made with self-efficacy in other subjects) and in achievement (Serbin et al., 2013; Vasquez-Salgado and Chavira, 2014; Mudaly and Sukhdeo, 2015), led to high dropout rates (McIntosh et al., 2008), caused stress and anxiety (Peters and Brooks, 2016), and were especially challenging for children with ASD (Mandy et al., 2016b; Tso and Strnadova, 2017). There does not seem to be a pattern in terms of which countries the research was conducted in, as the countries with a larger number of papers using negative discourse about transition also had a larger number of published studies overall. However, it can be said that in the case of countries with single papers 100% of papers had a negative (also Ireland, n=3, 100%) discourse seeking to address a problem during transitions as compared to 74% from the United States and 53% from Australia and the United Kingdom.

Mixed or neutral discourse about transition. Twenty-five papers made a reference to both negative and positive aspects of transitions; however, of these 15 highlighted more negative aspects than positives. Nine papers had a neutral discourse as they primarily focussed on other aspects such as the impact of school attachment and family involvement on negative behaviours (Frey et al., 2009), experience of children in PE (Rainer and Cropley, 2015), impact of school attachment and family involvement on negative behaviours during adolescence (Dann, 2011), and teachers’ perceptions of transition practices for children with developmental disabilities moving from primary to secondary school (Strnadova and Cumming, 2014).

Positive discourse about transition. Two papers primarily focussed on the positive impact of transitions; one each from Israel and the United Kingdom. Madjar and Chohat (2017) investigated self-efficacy in school transitions and the impact of perception of teachers' mastery goals on transition self-efficacy. Data were collected two months after starting grade 6 (last year of primary school), two months prior to finishing sixth grade, and two months after starting seventh grade in Israel. They considered primary-secondary school transitions to be part of a normative school career and proposed the concept of transition self-efficacy and developed a scale to measure it, which they saw as aligning to Stage-Environment Fit Theory (Eccles et al., 1993). Neal and Frederickson (2016) cited previous literature that described transitions of children with ASD as being problematic. However, they themselves took a strength-based approach to understand the positive experiences of six children with ASD who had successful transitions in the United Kingdom. They highlighted that with appropriate support children with ASD could have successful transitions and positive experiences.

Discussion

The way that researchers conceptualise school transitions has important implications for their research designs, study findings and implications used to inform future research, policy and practice. However, to date, school transition worldviews, theories/models and frameworks have not been studied systematically. The current study undertook a systematic mapping review of 96 papers published between 2008 and 2018 that were empirical studies of primary-secondary school transitions. The four authors, working collaboratively, analysed these papers using systematic methods of sorting, coding and synthesising to identify 1) researchers’ conceptualisations of primary-secondary school transitions, 2) research participants’ conceptualisations of school transitions, 3) theoretical frameworks used to explain processes during school transitions and 4) the discourse used by researchers to frame primary-secondary school transitions.

The results demonstrated a clear lack of conceptualisation of transition as a phenomenon either by researchers or participants. Rather than work their studies out of a complex theoretical perspective on transition as a phenomenon, researchers used popular conceptual frameworks to explain processes surrounding transition. These included Stage-Environment Fit Theory (Eccles et al., 1993), Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), Life Course Theory (Elder, 1998) and Self-determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Finally, the discourse surrounding transitions was predominantly negative, with only two of the 96 papers focusing on positive aspects of transition.

Researchers’ and Participants’ Conceptualisations of Primary-Secondary School Transitions

The most common conceptualisation of transition by researchers and participants was of transition as simply ‘change’. Researchers and participants also both mentioned the paradox of feeling excited and anxious during transition, identified in many other studies of transition (see Galton and McLellan (2017) for a summary). Other conceptualisations of transitions came from the researchers and fitted into two broad categories: more views of transition as change (including discontinuity, turning point, and disruption) and transition as a life-event (including transition as a normative period in school or life and transition as a rite of passage).

The conceptualisations of transitions as change were not specified with any degree of formality, and mainly reflected the literal meaning of the word transition. These are therefore best placed within the bottom level of the scientific paradigm framework described by Overton (2015), where people make common sense observations of an everyday phenomenon (Figure 5). The conceptualisations of primary-secondary school transitions as a life event are more formalised, as these take their notion from somewhere other than the literal meaning of the word transition. The notion of transition as a life event comes originally from anthropology (e.g., transition as a rite of passage; Benedict, 1938) and then from sociological ethnographies of school transition (Measor and Woods, 1984) and from Life Course Theory (Elder, 1998). Given its broad application across specific models and frameworks, and positionality of transition as a passage during which the person transforms, transition as a life event can be seen as a mid-range meta-theory in Overton's (2015) framework (Figure 5). However, this leaves a gap as no specific frameworks of transition as a phenomenon were identified in the systematic mapping review to bridge the gap between the naive conceptualisation of transition as change and the higher-level conceptualisation of transition as a life event.

FIGURE 5. Results mapped against Overton's (2015) framework

Theoretical Frameworks Used in Transitions Research

The main theoretical frameworks used to explain processes surrounding school transition could be located in the level of specific testable theories and models (Overton, 2015), between common sense observations and mid-range meta-theory (Figure 5). These were Stage-Environment Fit (Eccles et al., 1993), Self-determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000) and Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Each of the main theoretical frameworks outline how change can occur and were used to examine the adaptions in individual psychology across school transition; this was in relation to changes in person and the environment. Life Course Theory, being a broader perspective with no predictive qualities, was placed slightly above these in the level of mid-range meta-theory. Interestingly, there was no explicit link made by the researchers between any of the specific models/theories and Life Course theory, although it is quite possible that these could be combined to give a more detailed perspective on how processes occurring during transitions (e.g., through person-environment fit directed towards fulfilling basic psychological needs) might create the qualities of transition as ongoing impacting subsequent development in the life-course. None of these theories were explicitly transitions theories and had been borrowed from elsewhere. There was no attempt to critique the usability of these theories in transitions research. This might be due to the theories being mentioned in the introduction section without really underpinning the majority of studies.

Discourse Used to Frame Primary-Secondary School Transitions

The predominantly negative discourse about transition as being disruptive, a risk factor and promoting negative development appears to have no clear geographic origin in the reviewed papers nor links with any specific conceptualisation of transition or related conceptual framework. However, of the 96 studies, only four were from outside of Europe, North America and Australia. Of those within these latter countries, none were conducted with indigenous populations or by indigenous researchers (i.e., Aboriginal or Native American/First Nations). This means that nearly all the studies were from Western locales and perspectives. In non-Western cultures, but also historically in Western cultures, rites of passage are central to socially constructed notions of childhood and adulthood, marking a graduation from dependent child into fully functional member of society (Schlegel and Barry, 1991). After the person has gone through the rite of passage, they are given more responsibilities and in some cases more resources, that conceivably could mark the transition as a positive experience, and is a celebration of social, physical and psychological maturity.

However, although primary-secondary school transitions in Western cultures acts similarly as a rite of passage where children ‘graduate’ from primary to secondary schooling (Symonds, 2015), it is interesting to note that researchers mainly situate this in a negative discourse. Possibly this relates to repeated empirical findings of declining attitudes and attainment at transition (for reviews see Benner, 2011; Jindal-Snape et al., 2020; Symonds and Galton, 2014).

This could suggest that the repeated findings of negative trajectories mainly in the United Kingdom and United States might have something to do with the quality of lower-secondary education in those countries. On the other hand, the negative trajectories might be due to research designs that measured educational and wellbeing outcomes immediately before and after the move to secondary schools which did not capture the process of adaptation in the new environment. Further, it is not clear what type of questions participants were asked and their impact (see Jindal-Snape and Cantali, 2019, for an example of questions), or in the case of standardised scales, whether the timing of their administration was optimal. This belief is also supported by qualitative research reporting positive aspects of primary-secondary transitions that have been observed when studying holistic transitions (Jindal-Snape and Foggie, 2008), identity development (e.g., Measor and Woods, 1984; Symonds, 2015) and by meta-analyses of studies of friendship quality where children report having a greater number of better suited and supportive after moving to secondary school transition (Symonds and Galton, 2014). Overall, studies of positive aspects of primary-secondary school transitions are in the minority, a situation which is not helped by the continual use of negative discourses to frame transitions and research designs.

Conclusion

This is the first study that has attempted to understand the conceptualisations of primary-secondary school transitions through an analysis of previously published empirical studies. It has provided unique insights into (or lack of) researchers’ and participants’ conceptualisations of transitions theoretical frameworks and the discourses these might be situated in. This led to the identification of conceptual and methodological gaps in international literature. Firstly, most researchers, irrespective of the country of origin, did not clearly define what transitions meant in the specific context of their studies, and even when some conceptualisation was explicit, especially the theoretical framework, it did not necessarily underline the research design or frame the findings. For a field of research that is at least 60 years old, this finding from research conducted between 2008 and 2018, is surprising. This study, therefore, is well-placed to make a significant contribution to future research in this area. Secondly, the majority of researchers had not indicated their study participants’ conceptualisation of transitions. In the absence of these conceptualisations, it is difficult to determine the robustness of the findings and interpretation. Therefore, it is important that researchers make explicit their and their participants’ conceptualisations of transitions. In addition, acknowledge how their understanding changes over time. Thirdly, using Overton (2015) framework, it is clear that most researchers have adopted previously used conceptualisations and theoretical frameworks of transitions; the empirical studies in 2008–2018 did not use some of the other previously available frameworks (e.g., Five Bridges, Galton et al., 1999, see Figure 1). Thus, we are no further forward in terms of a meta-theory/world view (See Figure 5). This has implications for international research in terms of clear theorisation of primary-secondary transitions prior to conducting a study; considering new/revised theories based on the findings; having a research design that is in line with the conceptualisation (making clear how and why) and theory; and exploring participants’ conceptualisation of transitions. Further, it is important that as an international transitions research community, we work towards richer conceptualisations and understanding of transitions. This also includes a robust critique of theories that have been borrowed from elsewhere and a refining/development of theories relevant to primary-secondary school transitions.

The negative discourse in the majority of the papers was unexpected. It could be that most researchers focussed on transitions as a problematic issue to study and this in turn had an impact on the framing of the study, and potentially on the questions asked and results presented. Potentially, this could lead to a cycle of (negative) self-fulfilling prophecy. Therefore, future international research should shift the discourse, at least towards a more balanced view of transition experiences and their impact on a range of outcomes including educational and wellbeing outcomes.

Limitations

Although we undertook a systematic literature review and there was cross-checking by team members, it is possible that we have missed and/or rejected some crucial literature, including that written in other languages. Further, as this study focussed on a review of empirical studies, it is possible that we have missed a more nuanced conceptualisation of transitions in discursive literature. Therefore, it will be useful to conduct another literature review to explore conceptualisations and theories used in non-empirical literature.

Author Contributions

DJ-S conceived and designed the systematic literature review and systematic mapping review. DJ-S and JS organised the dataset. All authors equally contributed to the review of papers, completed the grid which formed the basis of analysis, undertook analysis and undertook cross-checks throughout. DJS wrote the first draft of Methodology and Results. JS wrote the first draft of Introduction and Discussion. EH and WB edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version. DJ-S and JS are joint-first authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Akos, P., Queen, J. A., and Lineberry, C. (2005). Promoting a successful transition to middle school. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Anderson, L. W., Jacobs, J., Schramm, S., and Splittgerber, F. (2000). School transitions: beginning of the end or a new beginning? Int. J. Educ. Res. 33 (4), 325–339. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00020-3

Andreas, J. B., and Jackson, K. M. (2015). Adolescent alcohol use before and after the high school transition. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 39 (6), 1034–1041. doi:10.1111/acer.12730

Arens, A. K., Yeung, A. S., Craven, R. G., Watermann, R., and Hasselhorn, M. (2013). Does the timing of transition matter? Comparison of German students’ self-perceptions before and after transition to secondary school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 57, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.11.001

Bailey, S., and Baines, E. (2012). The impact of risk and resiliency factors on the adjustment of children after the transition from primary to secondary school. Educ. Child Psychol. 29 (1), 47–63.

Benedict, R. (1938). Continuities and discontinuities in cultural conditioning. Psychiatry Interpersonal Biol. Process. 1 (2), 161–167. doi:10.1080/00332747.1938.11022182

Benner, A. D., and Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Develop. 80 (2), 356–376. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x

Benner, A. D. (2011). The transition to high school: current knowledge, future directions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23 (3), 299. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9152-0

Benner, A. D., and Wang, Y. (2014). Shifting attendance trajectories from middle to high school: influences of school transitions and changing school contexts. Develop. Psychol. 50 (4), 1288–1301. doi:10.1037/a0035366

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., and Bakhtiari, F. (2017). Understanding students’ transition to high school: Demographic variation and the role of supportive relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 46 (10), 2129–2142. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2

Booth, M. Z., and Sheehan, H. C. (2008). Perceptions of people and place young adolescents’ interpretation of their schools in the United States and the United Kingdom. J. Adolesc. Res. 23 (6), 722–744. doi:10.1117/0743558408322145

Brewin, M., and Statham, J. (2011). Supporting the transition from primary school to secondary school for children who are looked after. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 27 (4), 365–381. doi:10.1080/02667363.2011.624301

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993). “The ecology of cognitive development: research models and fugitive findings,” in Development in context: acting and thinking in specific environments. Editors R. Wonziak, and K. Fischer (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 3–44.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burchinal, M. R., Roberts, J. E., Zeisel, S. A., and Rowley, S. J. (2008). Social risk and protective factors for African American children’s academic achievement and adjustment during the transition to middle school. Develop. Psychol. 44 (1), 286–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.286

Cantali, D. (2017). “Primary to secondary school transitions for children with additional support needs: what the literature is telling us,” in Promoting inclusion transforming Lives (PITL) international conference 2017, Dundee, United Kingdom, June 14–16, 2017 (Dundee, United Kingdom: University of Dundee).

Dann, R. (2011). Secondary transition experiences for pupils with autistic spectrum conditions (ASCs). Educ. Psychol. Pract. Theor. Res. Pract. Educ. Psychol. 27 (3), 293–312. doi:10.1080/02667363.2011.603534

Dismore, H., and Bailey, R. (2010). It’s been a bit of a rocky start’: attitudes toward physical education following transition. Phys. Edu. Sport Pedagogy 15 (2), 175–191. doi:10.1080/17408980902813935

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., et al. (1993). Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am. Psychol. 48, 90–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Eccles, J. S., and Midgley, C. (1989). “Stage-environment fit: developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents,” in Research on Motivation in education. Editors R. Ames, and C. Ames (New York, NY: Academic Press), 139–181.

Elder, G. H. J. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Devel 69 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06128.x

Ellerbrock, C. R., and Kiefer, S. M. (2013). The interplay between adolescent needs and secondary school structures: fostering developmentally responsive middle and high school environments across the transition. High Sch. J. 96 (3), 170–194. doi:10.1353/hsj.2013.0007

EPPI-Centre (2010). EPPI Centre methods for conducting systematic reviews. London, United Kingdom: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

Eurydice (2018). Organisation of the education system and of its structure. Available at: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/organisation-education-system-and-its-structure-115_en (Accessed May 06, 2019).

Evans, D., Borriello, G. A., and Field, A. P. (2018). A review of the academic and psychological impact of the transition to secondary education. Front. Psychol. 9, 1482. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01482

Felmlee, D., McMillan, C., Inara Rodis, P., and Osgood, D. W. (2018). Falling behind: lingering costs of the high school transition for youth friendships and grades. Sociol. Edu. 91 (2), 159–182. doi:10.1177/0038040718762136

Fortuna, R. (2014). The social and emotional functioning of students with an autistic spectrum disorder during the transition between primary and secondary schools. Support Learn. 29 (2), 177–191. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12056

Frey, A., Ruchkin, V., Martin, A., and Schwab-Stone, M. (2009). Adolescents in transition: school and family characteristics in the development of violent behaviors entering high school. Child Psychiatry Hum. Devel 40 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1007/s10578-008-0105-x

Galton, M. (2010). “Moving to secondary school: what do pupils in England say about the experience?,” in Educational transitions: moving stories from around the world. Editor D. Jindal-Snape (New York, NY: Routledge), 107–124.

Galton, M., Gray, J., and Ruddock, J. (1999). The impact of school transitions and transfers on pupil progress and attainment. London, United Kingdom: DfEE.

Galton, M., Gray, J., and Ruddock, J. (2003). Transfer and transition in the middle years of schooling (7–14): continuities and discontinuities in learning. Research Report RR443. Nottingham, United Kingdom: DfES Publications.

Galton, M., and McLellan, R. (2017). A transition Odyssey: pupils’ experiences of transfer to secondary school across five decades. Res. Pap. Edu. 33, 1–23. doi:10.1080/02671522.2017.1302496

Galton, M., Morrison, I., and Pell, T. (2000). Transfer and transition in English schools: reviewing the evidence. Int. J. Educ. Res. 33, 340–363. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00021-5

Garrard, J. (2016). Health sciences literature review made easy. London, United Kingdom: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1971). Status passage. Chicago, United States: Aldine Atherton Inc.

Goldstein, M. B., and Blumenkrantz, D. G. (2019). “Rites of passage: history, theory, and culture in adolescence transitions,” in The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development. Editors S. Hupp, and J. D. Jewell (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc.), 1–12. doi:10.1002/9781119171492.wecad323

Gordon, L., Jindal-Snape, D., Morrison, J., Muldoon, J., Needham, G., Siebert, S., et al. (2017). Multiple and multidimensional transitions from trainee to trained doctor: a qualitative longitudinal study in the UK. BMJ Open 7 (11), 1–12. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018583

Gough, D., Thomas, J., and Oliver, S. (2019). Clarifying differences between reviews within evidence ecosystems. Syst. Rev. 8, 170. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1089-2

Hallinan, P., and Hallinan, P. (1992). Seven into eight will go: transition from primary to secondary school. Aust. Educ. Develop. Psychol. 9 (2), 30–38.

Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: why it is important and how it can Be supported. Aust. J. Teach. Edu. 38 (1), 62–74. doi:10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.7

Hannah, E. F., and Topping, K. J. (2013). The transition from primary to secondary school: perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Int. J. Spec. Edu. 28 (1), 145–157.

Hargreaves, D. J. (1984). Improving secondary schools. London, United Kingdom: Inner London Education Authority.

A. Howe, and V. Richards (Editors) (2011). Bridging the transition from primary to secondary school. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Hughes, L. A., Banks, P., and Terras, M. M. (2013). Secondary school transition for children with special educational needs: a literature review. Support Learn. 28 (1), 24–34. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12012

Jindal-Snape, D., and Cantali, D. (2019). A four-stage longitudinal study exploring pupils’ experiences, preparation and support systems during primary-secondary school transitions. Br. Educ. Res. J. 45 (6), 1255–1278. doi:10.1002/berj.3561

Jindal-Snape, D., and Foggie, J. (2008). A holistic approach to primary-secondary-transitions. Improving Schools 11, 5–18. doi:10.1177/1365480207086750

Jindal-Snape, D., Hannah, E., Cantali, D., Barlow, W., and MacGillivray, S. (2020). Systematic literature review of primary‒secondary transitions: international research. Rev. Educ. 8, 526–566. doi:10.1002/rev3.3197

Jindal-Snape, D., Johnston, B., Pringle, J., Kelly, T., Scott, R., Gold, L., et al. (2019). Multiple and multidimensional life transitions in the context of life-limiting health conditions: longitudinal study focussing on perspectives of young adults, Families and Professionals. BMC Palliat. Care 18, 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0414-9

Jindal-Snape, D. (2018). “Transitions from early years to primary and primary to secondary,” in Scottish education. 5th Edn, Editors T. G. K. Bryce, W. M. Humes, D. Gillies, and A. Kennedy (Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press), 281–291.

Keay, A., Lang, J., and Frederickson, N. (2015). Comprehensive support for peer relationships at secondary transition. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31 (3), 279–292. doi:10.1080/02667363.2015.1052046

Kingdon, D., Serbin, L. A., and Stack, D. M. (2017). Understanding the gender gap in school performance among low-income children: a developmental trajectory analysis. Int. J. Behav. Devel 41 (2), 265–274. doi:10.1177/0165025416631836

Kingery, J. N., Erdley, C. A., and Marshall, K. C. (2011). Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents' adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Quart. J. Develop. Psychol. 57 (3), 215–243. doi:10.1353/mpq.2011.0012

Knesting, K., Hokanson, C., and Waldron, N. (2008). Settling in: facilitating the transition to an inclusive middle school for students with mild disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Develop. Educ. 55 (3), 265–276. doi:10.1080/10349120802268644

Langenkamp, A. G. (2010). Academic vulnerability and resilience during the transition to high school: the role of social relationships and district context. Sociol. Edu. 83 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1177/0038040709356563

Lofgran, B. B., Smith, L. K., and Whiting, E. F. (2015). Science self-efficacy and school transitions: elementary school to middle school, middle school to high school. Sch. Sci. Math. 115 (7), 366–376. doi:10.1111/ssm.12139

Mackenzie, E., McMaugh, A., and O’Sullivan, K. (2012). Perceptions of primary to secondary school transitions: challenge or threat? Issues Educ. Res. 22 (3), 298–314.

Madjar, N., and Chohat, R. (2017). Will I succeed in middle school? A longitudinal analysis of self-efficacy in school transitions in relation to goal structures and engagement. Educ. Psychol. 37 (6), 680–694. doi:10.1080/01443410.2016.1179265

Maher, D. (2010). Supporting students’ transition from primary school to high school using the internet as a communication tool. Tech. Pedagogy Educ. 19 (1), 17–30. doi:10.1080/14759390903579216

Makin, C., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2017). The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: a multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism Develop. Lang. Impairments 2, 1–18. doi:10.1177/2396941516684834

Mandy, W., Murin, M., Baykaner, O., Staunton, S., Hellriegel, J., Anderson, S., et al. (2016a). The transition from primary to secondary school in mainstream education for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 20 (1), 5–13. doi:10.1177/1362361314562616

Mandy, W., Murin, M., Baykaner, O., Staunton, S., Cobb, R., Hellriegel, J., et al. (2016b). Easing the transition to secondary education for children with autism spectrum disorder: an evaluation of the systemic transition in education programme for Autism spectrum disorder (STEP-ASD). Autism 20 (5), 580–590. doi:10.1177/1362361315598892

McIntosh, K., Flannery, K. B., Sugai, G., Braun, D. H., and Cochrane, K. L. (2008). Relationships between academics and problem behavior in the transition from middle school to high school. J. Positive Behav. Interventions 10 (4), 243–255. doi:10.1177/1098300708318961

Measor, L., and Woods, P. (1984). Changing schools. Milton Keynes, United Kingdom: Open University Press.

Mudaly, V., and Sukhdeo, S. (2015). Mathematics learning in the midst of school transition from primary to secondary school. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 11 (3), 244–252. doi:10.1080/09751122.2015.11890395

Neal, S., and Frederickson, N. (2016). ASD transition to mainstream secondary: a positive experience? Educ. Psychol. Pract. 32 (4), 355–373. doi:10.1080/02667363.2016.1193478\

Neal, S., Rice, F., Ng-Knight, T., Riglin, L., and Frederickson, N. (2016). Exploring the longitudinal association between interventions to support the transition to secondary school and child anxiety. J. Adolescence 50, 31–43. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.003

Noyes, A. (2006). School transfer and the diffraction of learning trajectories. Res. Pap. Edu. 21 (1), 43–62. doi:10.1080/02671520500445441

Overton, W. F. (2015). “Process and relational developmental systems,” in Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th Edn, Editors R. M. Lerner, W. F. Overton, and P. C. M. Molenaar (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), Vol. 1, 9–62.

Pearson, N., Haycraft, E., Johnston, J. P., and Atkin, A. J. (2017). Sedentary behaviour across the primary-secondary school transition: a systematic review. Prev. Med. 94, 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.010

Peters, R., and Brooks, R. (2016). Parental perspectives on the transition to secondary school for students with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: a pilot survey study. Br. J. Spec. Edu. 43 (1), 75–91. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12125

Poorthuis, A. M. G., Thomaes, S., Aken, M. A. G., Denissen, J. J. A., and de Castro, B. O. (2014). Dashed hopes, dashed selves? A sociometer perspective on self‐esteem change across the transition to secondary school. Soc. Develop. 23 (4), 770–783. doi:10.1111/sode.12075

Rainer, P., and Cropley, B. (2015). Bridging the gap–but mind you don’t fall. Primary physical education teachers’ perceptions of the transition process to secondary school. Education 43 (5), 445–461. doi:10.1080/03004279.2013.819026

Reeve, J. (2015). “Growth motivation and positive psychology,” in Understanding motivation and emotion. 6th Edn. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 431–465.

Rudduck, J. (1996). Going to ‘the big school’: the turbulence of transition, in School improvement: what can pupils tell us? Editors J. Rudduck, R. Chaplain, and G. Wallace (London, United Kingdom: David Fulton Publishers), 19–28.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68–78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Scanlon, G., Barnes-Holmes, Y., McEnteggart, C., Desmond, D., and Vahey, N. (2016). The experiences of pupils with SEN and their parents at the stage of pre-transition from primary to post-primary school. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 31 (1), 44–58. doi:10.1080/08856257.2015.1087128

Schlegel, A. A., and Barry, H. (1991). Adolescence: an anthropological inquiry. New York, NY: Free Press.

Serbin, L. A., Stack, D. M., and Kingdon, D. (2013). Academic success across the transition from primary to secondary schooling among lower-income adolescents: understanding the effects of family resources and gender. J. Youth Adolescence 42 (9), 1331–1347. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9987-4

Shute, R. H., and Slee, P. T. (2015). Child development: theories and critical perspectives. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Strnadova, I., Cumming, T. M., and Danker, J. (2016). Transitions for students with intellectual disability and/or autism spectrum disorder: carer and teacher perspectives. Aust. J. Spec. Edu. 40 (2), 141–156. doi:10.1017/jse.2016.2

Strnadova, I., and Cumming, T. M. (2014). The importance of quality transition processes for students with disabilities across settings: learning from the current situation in New South Wales. Aust. J. Edu. 58 (3), 318–333. doi:10.1177/0004944114543603

Symonds, J., and Galton, M. (2014). Moving to the next school at age 10–14 years: an international review of psychological development at school transition. Rev. Educ. 2 (1), 1–27. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01482

Symonds, J., and Hargreaves, L. (2016). Emotional and motivational engagement at school transition: a qualitative stage-environment fit study. J. Early Adolescence 36 (1), 54–85. doi:10.1177/0272431614556348

Symonds, J. (2015). Understanding school transition: what happens to children and how to help them. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Topping, K. (2011). Primary–secondary transition: differences between teachers’ and children's perceptions. Improving Schools 14 (3), 268–285. doi:10.1177/1365480211419587

Tso, M., and Strnadova, I. (2017). Students with autism transitioning from primary to secondary schools: parents’ perspectives and experiences. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 21 (4), 389–403. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1197324

van Rens, M., Haelermans, C., Groot, W., and van den Brink, H. M. (2018). Facilitating a successful transition to secondary school: (How) Does it work? A systematic literature review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 3, 43–56. doi:10.1007/s40894-017-0063-2

Vasquez-Salgado, Y., and Chavira, G. (2014). The transition from middle school to high school as a developmental process among Latino youth. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 36 (1), 79–94. doi:10.1177/0739986313513718

Waters, S. K., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2014a). Transition to secondary school: expectation versus experience. Aust. J. Edu. 58 (2), 153–166. doi:10.1177/0004944114523371

Waters, S., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2014b). How does support from peers compare with support from adults as students transition to secondary school? J. Adolesc. Health 54 (5), 543–549. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.012

Weiss, C. C., and Baker-Smith, E. (2010). Eighth-grade school form and resilience in the transition to high school: a comparison of middle schools and K-8 schools. J. Res. Adolescence 20 (4), 825–839. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00664.x

West, P., Sweeting, H., and Young, R. (2010). Transition matters: pupils’ experiences of the primary-secondary school transition in the West of Scotland and consequences for well-being and attainment. Res. Pap. Educ. 25 (1), 21–50. doi:10.1080/02671520802308677

Witherspoon, D., and Ennett, S. (2011). Stability and change in rural youths’ educational outcomes through the middle and high school years. J. youth Adolescence 40 (9), 1077–1090. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9614-6

M. Youngman (Editor) (1986). Mid-schooling transfer: Problems and proposals. Windsor, CA: NFER–Nelson.

Keywords: primary-secondary school transitions, conceptualisation, theory, discourse, ontology, systematic mapping review

Citation: Jindal-Snape D, Symonds JE, Hannah EFS and Barlow W (2021) Conceptualising Primary-Secondary School Transitions: A Systematic Mapping Review of Worldviews, Theories and Frameworks. Front. Educ. 6:540027. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.540027

Received: 03 March 2020; Accepted: 08 February 2021;

Published: 17 March 2021.

Edited by:

Sanna Ulmanen, Tampere University, FinlandReviewed by:

Taro Fujita, University of Exeter, United KingdomKathryn Holmes, Western Sydney University, Australia